Submitted:

28 February 2024

Posted:

29 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Importance of Rice Cultivation and the Framework for Its Organisation in the Balkans

2.1. The Framework for Organising Rice Cultivation

2.2. Examples of Rice Cultivation in Thessaly and Farsala

3. Materials and Methods

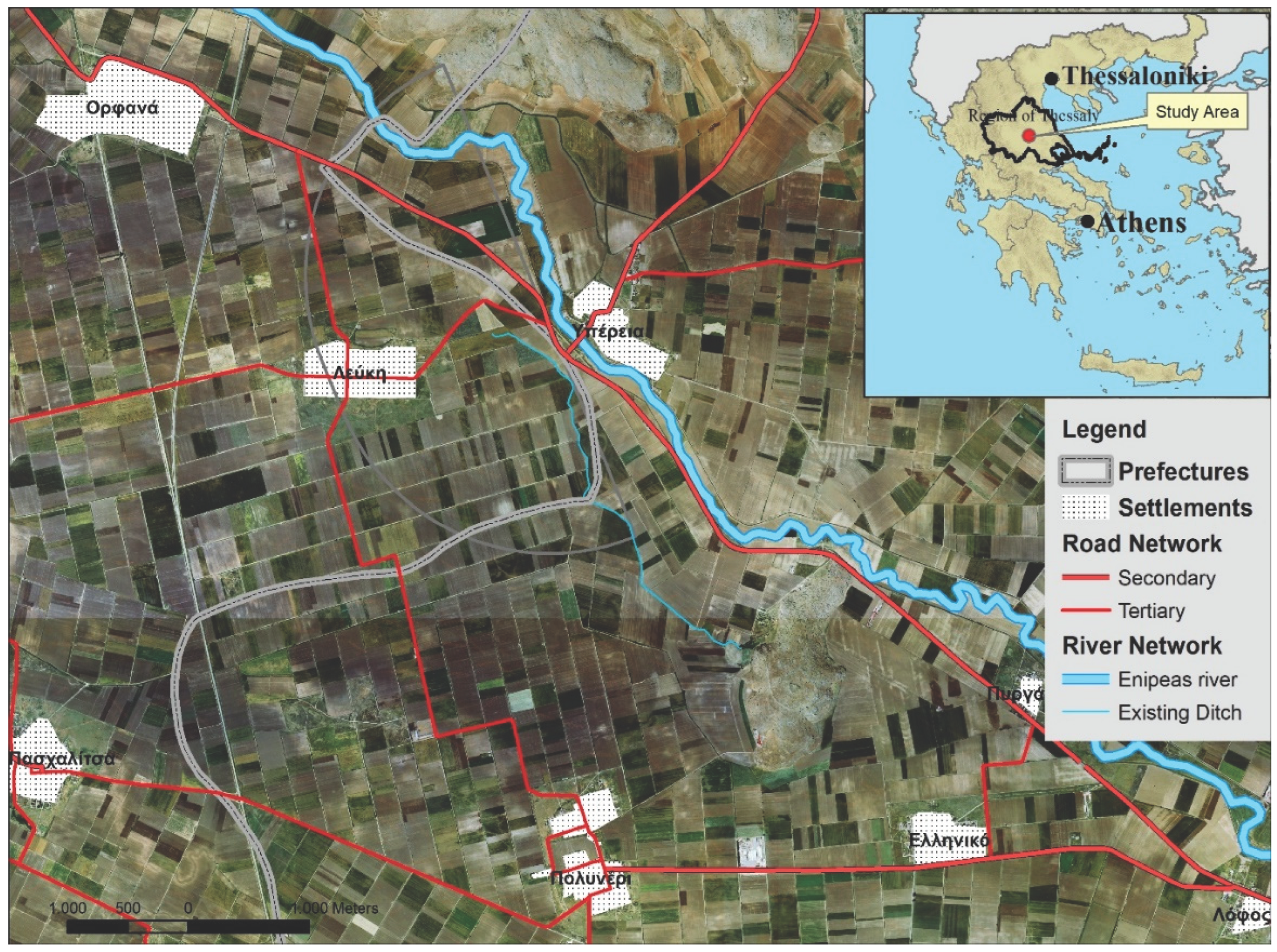

3.1. Case Study

3.2. Study Period and Data Collection

- Topographical diagrams with a scale of 1/5000. They show the elevation (contour lines/isohypse at 4 m intervals), toponyms, the hydrographic and the road network. (GIS, https://www.gys.gr/hmgs-geoindex_en.html).

- Black and white aerial photographs (APs) from 1945 with a scale of 1:4000 and colour APs from 2017 with a scale of 1:5000, with the creation of corresponding orthophoto maps (ordered from the Hellenic Cadastre, https://www.ktimatologio.gr/el).

- A field study in the communities of the study area and meetings with residents to obtain information on the existence of streams, pre-1970 crops and soil quality through 3D representations.

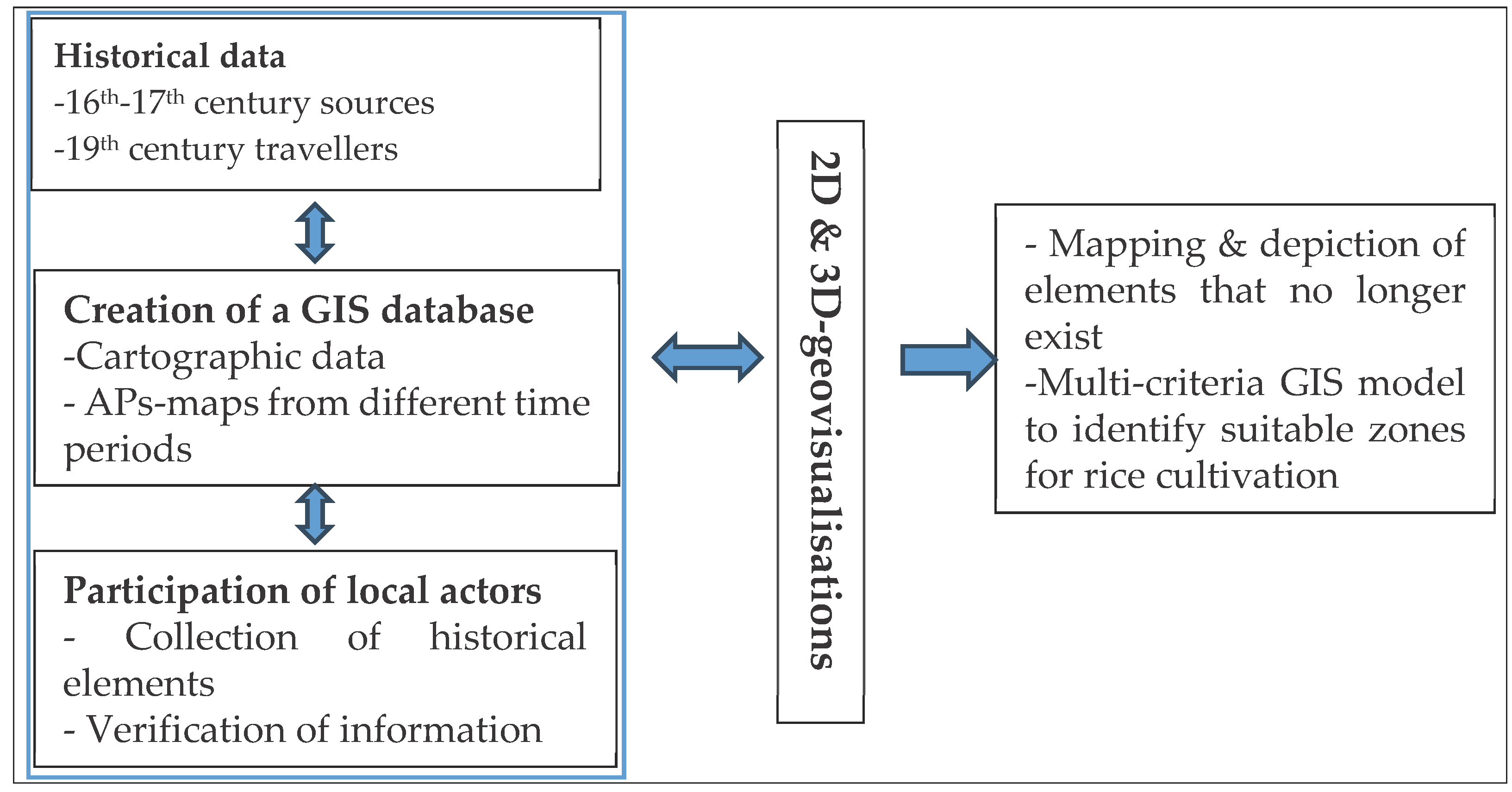

3.3. Methodology

- Collection and geocoding of historical and contemporary information from bibliographical sources with the use of GIS.

- Use of 3D geovisualisations to obtain information from local actors.

- Application of geoinformatics methods (spatial analysis) to reveal and identify elements.

3.3.1. Collection of Historical and Current Information

3.3.2. Participatory Processes with the Use of 3D Geovisualisations

- be willing to share information,

- be born in the 1950s or earlier,

- be knowledgeable about the area (farmers by profession) with good sense of orientation.

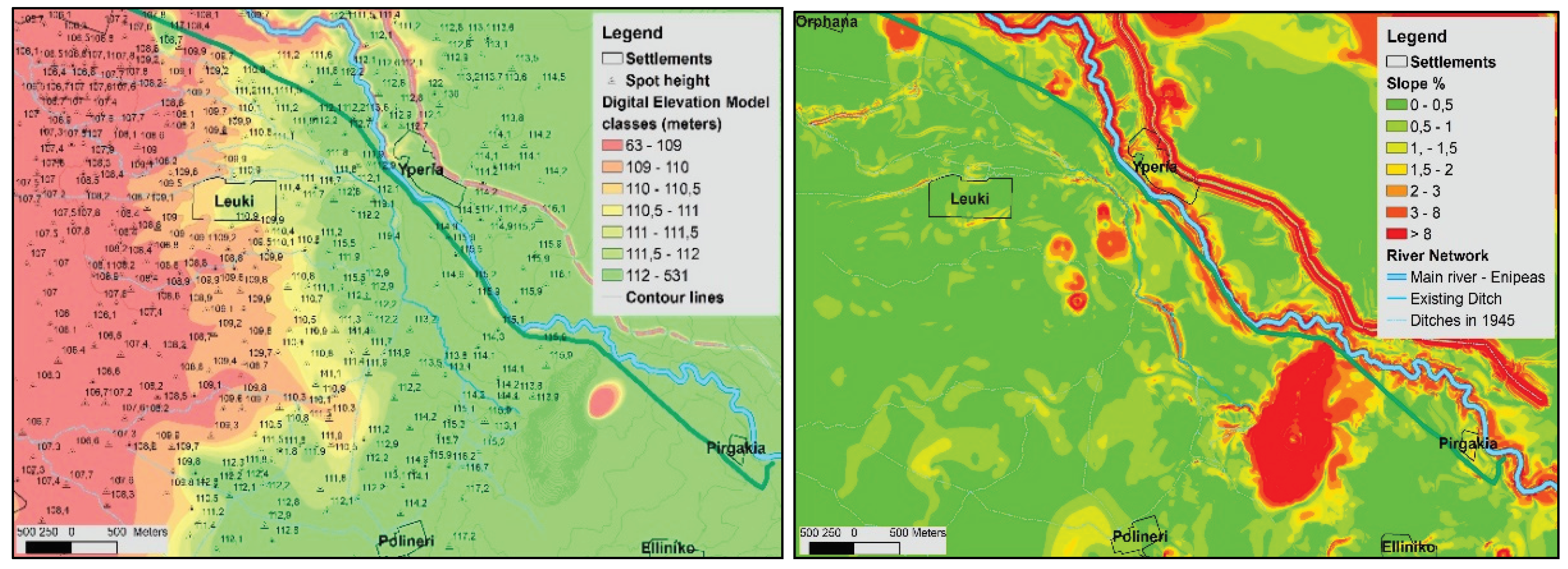

3.3.3. Criteria for the Identification of Suitability Zones

1. Soil & Topographical Characteristics

2. Irrigation Infrastructure

3. Multicriteria Model

4. Results

4.1. Map of Suitability Zones

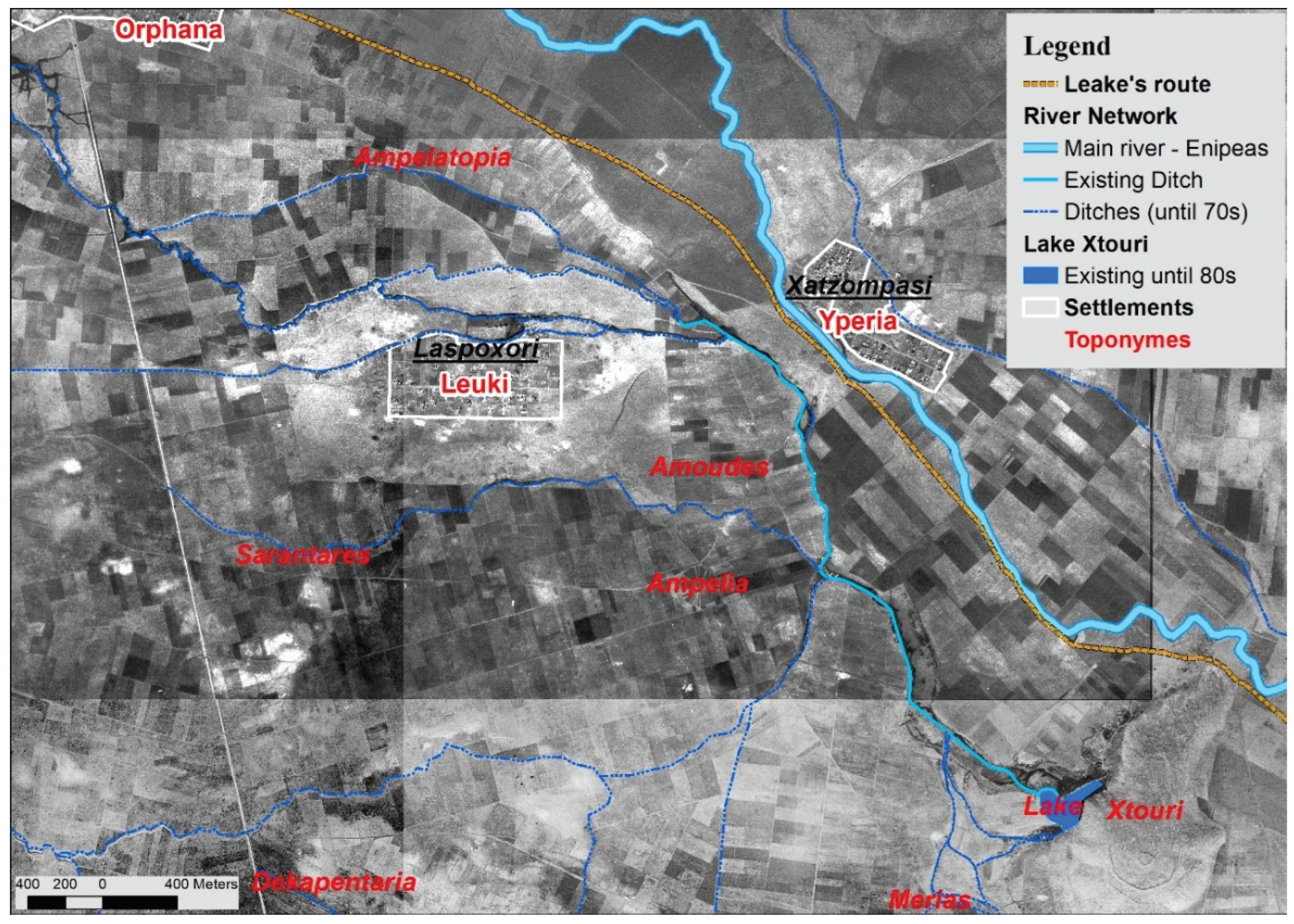

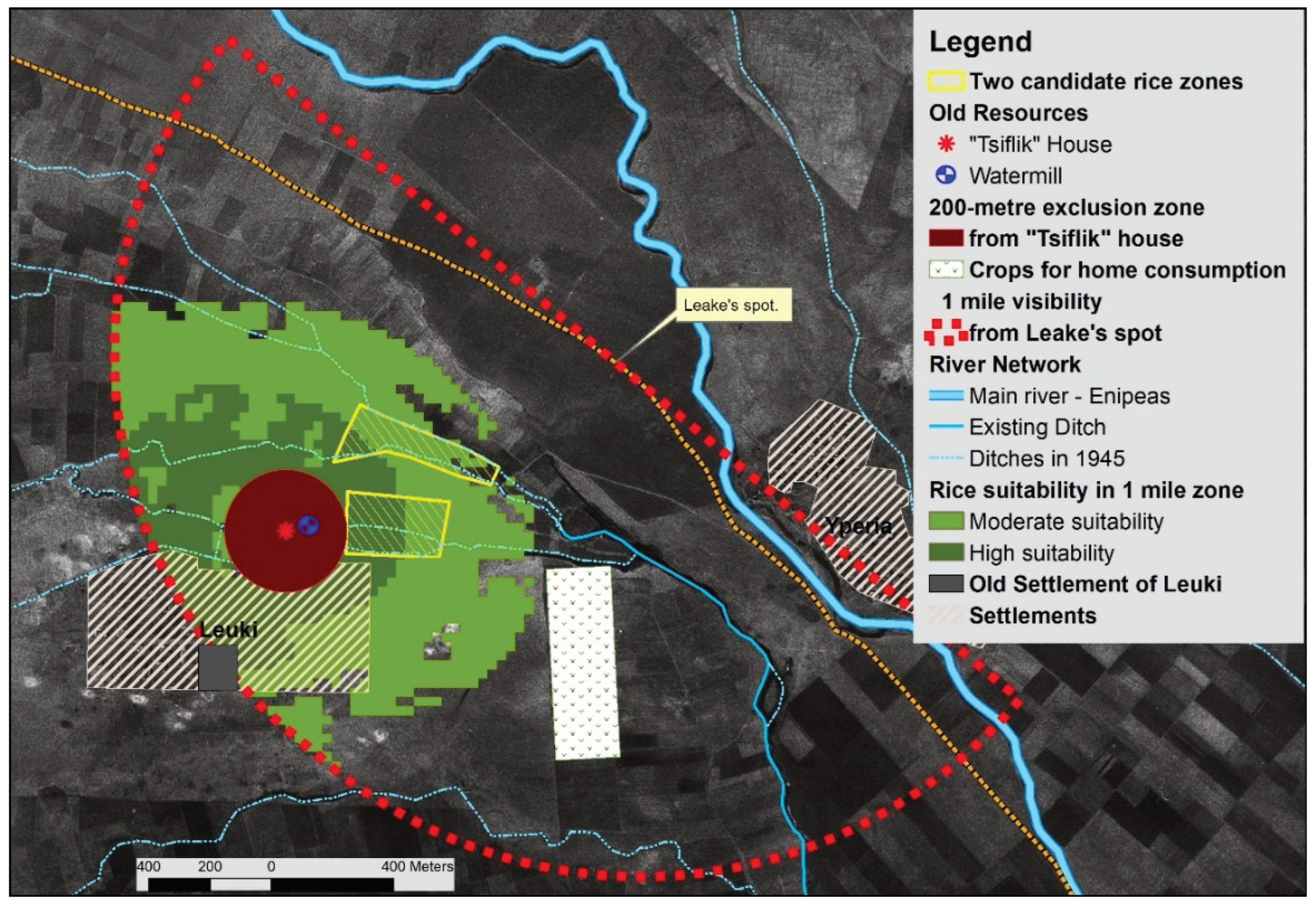

4.2. Identifying the Location of Paddy Fields

- Zone dedicated to crops for own personal consumption (legumes, etc.) due to specific soil characteristics. It is located at a distance of 600 m, east-southeast of the village of Lefki, in the zone of sandy soils, fragmented into small parcels of 0.5-1 ha. This zone lies outside the flood zone upstream of the channel branches, and therefore could not be used for rice cultivation.

- Information from residents that the toponym "the rice" extended northeast of the village of Lefki above the road connecting the villages of Hyperia-Lefki.

- The zone crossed by the 1st and 2nd forks in the channels from the central ditch. The choice of channels enables better water management and uninterrupted flow for the neighbouring communities, as required by the regulation.

- Adequate distance from the big landowner’s residence (konak) (to avoid humidity and mosquitoes). For this purpose, a 200 m exclusion zone was created.

- Leake’s report that rice paddies surrounded the village for a mile. It is argued that Leake's ability to identify rice paddies from a distance of approximately 1600 m in December, i.e., when the rice harvest and water draining had already been completed, was based on the existence of bunds and special constructions, known as “tigania”.

- The directions of the strongest winds in the area in relation to the position and layout of the paddy field. The west and north-west layout of the artificial channels north of the village, combined with the strong local westerly and north-easterly winds, indicate the existence of two potential adjacent locations for a rice paddy (A and B) as shown in the following figure (Figure 9). At these locations, the layout of the paddy basin was determined based on the layout of the channels.

- siting of the paddy fields chosen in order to combine: (i) soil characteristics, (ii) use of the local hydrographic network (other crops, sharing water with downstream communities through which the ditch passes, and (iii) the appropriate location and layout of the paddy field to prevent impacts on health (malaria) and the crop due to winds.

- integration of the paddy field into the mixed production system and the local agro-ecological system (biodiversity, ecological water, etc.) without impacting them. Although the spatial-agronomic criteria would allow the expansion of the paddy field, its surface area seems to be further dependent on the obligation of the community of Lefki to supply the other communities with part of the water from the ditch.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Role of the Represented Space

5.2. The Contribution of Past Knowledge to Planning the Future

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A tax district or resource area or other source of revenue that the State conceded to individuals for a set period of time |

| 2 | Çeltukçi- Re'âyâ: rice farmers, supervised workers, landless and tax exempt persons |

| 3 | Document on rice, sent (16th century) to administrations (Sanjaks) in the Balkans to be implemented |

| 4 | Due to labour shortages, some areas used nomads or workers |

| 5 | The first law for the Sanjak of Trikala, during the time of Muhammad the Conqueror, “Tırhala Yasaknamesi". It concerns rice cultivation (rice paddy locations and issues related to the rice market). |

| 6 | GIS spatial analysis – 3D visualisation (current – past): the contribution of 3D in information extraction |

References

- Campagne, P.; Pecqueur, B. Le développement territorial. Une réponse émergente à la mondialisation; Éditions Charles Léopold Mayer (ECLM): Paris, France, 2014; p. 268. ISBN 978-2-84377-184-2. [Google Scholar]

- Goussios, D.; Faraslis, I. Integrated Remote Sensing and 3D GIS Methodology to Strengthen Public Participation and Identify Cultural Resources. Land 2022, 11, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goussios, D.; Faraslis, I. The Driving Role of 3D Geovisualization in the Reanimation of Local Collective Memory and Historical Sources for the Reconstitution of Rural Landscapes. Land 2023, 12, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Méo, G. Le patrimoine, un besoin social contemporain. In Proceedings of the Patrimoine et estuaires, Actes du colloque international de Blaye, France, 5–7 October 2005. ⟨halshs-00281467⟩. [Google Scholar]

- Talandier, M.; Navarre, F.; Cormier, L.; Landel, P.A.; Ruault, J.F.; Senil, N. (2019). Les sites patrimoniaux exceptionnels: une ressource pour les territoires; Editions du PUCA, Lyon, France, 2019; collection Recherche n° 237, pp.319.

- Senil, N.; Landel, P.A. De la ressource territoriale à la ressource patrimoniale. In Au cœur des territoires créatifs. Proximités et ressources territoriales; Glon, E., Pecqueur, B., Eds.; Publisher: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, France, 2016; 978-2-7535-4951-7. [Google Scholar]

- Beiner Guy. Troubles with Remembering; or, The Seven Sins of Memory Studies; Publisher: Dublin Review of Books, Dublin, Ireland, 2017, pp.218. [CrossRef]

- Gouriveau, F.; Beaufoy, G.; Moran, J.M.; Poux, X.; Herzon, I.; et al. What EU policy framework do we need to sustain High Nature Value (HNV) farming and biodiversity? 2019; hal-02568129f. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, C.; Poux, X.; Herzon, I.; Moran, J.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Dumitras, D.E.; Ferraz-de-Oliveira, M.I.; Gouriveau, F.; Goussios, D.; Jitea, M.I.; Kazakova, Y.; Koivuranta, R.; Lerin, F.; Ljung, M.; Lomba, A.; Mihai, V.C.; Puig de Morales Fusté, M.; Vlahos, G. Innovation brokers in High Nature Value farming areas: a strategic approach to engage effective socioeconomic and agroecological dynamics. Ecol. Soc. 2023, 28, article20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landel, P.A. Invention de patrimoines et construction des territoires. La Ressource territorial; Economica Ed.; Publisher HAL-SHS, 2007, Volume Anthropos, p.157. ⟨halshs-00320442⟩.

- Le Coz, J. Espaces méditerranéens et dynamiques agraires: état territorial et communautés rurales. In Espaces méditerranéens et dynamiques agraires: état territorial et communautés rurales; Le Coz, J., Ed.; Publisher: CIHEAM, Montpellier, France, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Groupe de Bruges. Agriculture: un tournant necessaire, 2e éd. rev. et augm; Editeur: La Tour d'Aigues, l'Aube, France, 2002; p. 89, ISBN/ISSN/EAN: 978-2-87678-708-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. Four Ages of Professionalism and Professional Learning. Teach. Teach.: Theory Pract. 2000, 6, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofos, A. Sofos, A. Pedagogical and Instructional Competence in Teacher Education: A Review of Practices and Recommendations. In Pedagogical Departments and their Future; A. Sofos et al. Eds.; Publisher: Grigoris, Athens, Greece (in Greek), 2019; pp. 81-108.

- Nora, P. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Representations 1989, 26, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piveteau, J.L. L’épaisseur temporelle de l’organisation de l’espace: «palimpseste» et «coupe transversale». Géopoint, 1992, 211-220.

- Piveteau, J.L. Le territoire est-il un lieu de mémoire? Espace Géogr. 1995, 24-2, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fominykh, M.; Prasolova-Førland, E.; Hokstad, L.; Morozov, M. Repositories of Community Memory as Visualized Activities in 3D Virtual Worlds. In Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6 January 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokka, I.; Çöltekin, A. SIMULATING NAVIGATION WITH VIRTUAL 3D GEOVISUALIZATIONS – A FOCUS ON MEMORY RELATED FACTORS, Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci., 2016, XLI-B2, 671–673. [CrossRef]

- Sorre, M. Connaissance du paysage humain. Bulletin de la Société de Géographie de Lille (nouvelles séries) 1958, 1, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pinchemel, P.G. La face de la terre. Publisher: Armand Colin, Paris, France, 1988; pp.519.

- Arrighi, C.; Francesco, B.; Tommaso, S. A GIS-based flood damage index for cultural heritage. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2023, 90, 103654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciski, M.; Krzysztof, R.; Marek, O. Use of GIS Tools in Sustainable Heritage Management—The Importance of Data Generalization in Spatial Modeling. Sustainability, 2019; 11, 5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscione, M.; Danese, M.; Masini, N. A framework for cultural heritage management and research: the Cancellara case study. J. Maps, 14. [CrossRef]

- Elfadaly, A.; Shams eldein, A.; Lasaponara, R. Cultural Heritage Management Using Remote Sensing Data and GIS Techniques around the Archaeological Area of Ancient Jeddah in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 2020; 12, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HUANG, S.; HU, Q.; WANG, S.; LI, H. Ecological Risk Assessment of World Heritage Sites Using RS and GIS: A Case Study of Huangshan Mountain, Chin. Geogr. Sci., 2022, 32, 808−823. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Chen, J.; Tong, D.; Li, X. Planning control over rural land transformation in Hong Kong: A remote sensing analysis of spatio-temporal land use change patterns. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Frenierre, Jeff. Mapping heritage: A participatory technique for identifying tangible and intangible cultural heritage. Int. J. Incl. Mus., 2008, 1. 97-104. [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.; Gonçalves, J.; Almeida, P.G.; Martins-Nepomuceno, M.T.A. GIS-based inventory for safeguarding and promoting Portuguese glazed tiles cultural heritage. Herit. Sci., 2023, 11, 133. [CrossRef]

- Armin, G. SMART Cities: The need for spatial intelligence. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci., 2013, 16, 3-6. [CrossRef]

- Papachristophorou, M. Narrative Maps, Collective Memory, and Identities: Through an Ethnographic Example from the Southeast Aegean. Narrat. Cult. 2016, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, B.H.; DeFanti, T.A.; Brown, M.D. 1987. Visualization in Scientific Computing. Comput. Graph., 1987, 21. https://www.evl.uic.edu/pubs/1501.

- Punia, M.; KUNDU, A. Three dimensional modelling and rural landscape geo-visualization using geo-spatial science and technology. Neo geogr. 2014, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, X.; He, F.; Wang, X. Participatory Historical Village Landscape Analysis Using a Virtual Globe-Based 3D PGIS: Guizhou, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandham, L.A.; Chabalala, J.J.; Spaling, H.H. Participatory Rural Appraisal Approaches for Public Participation in EIA: Lessons from South Africa. Land 2019, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazagol, P.O.; Niogret, P.; Riquier, J.; Depeyre, M.; Ratajczak, R.; Crispim-Junior, C.F.; Tougne, L. Tools Against Oblivion: 3D Visualization of Sunken Landscapes and Cultural Heritages Applied to a Dam Reservoir in the Gorges de la Loire (France). J. Geovisualization Spat. Ana., 2021, 5. [CrossRef]

- Baudelle, G.Ph.; Pinchemel G. La Face de la Terre. Hommes et Terres du Nord, 1989, 1-2. Nord-Pas-de-Calais, 118. www.persee.fr/doc/htn_0018-439x_1989_num_1_1_2212_t1_0118_0000_1.

- Birnbaum, D.M. The Fuggers, Hans Dernschwam, and the Ottoman Empire. Southeast Research, 2021, 1, 119–144. http://bsb0sit-zepweb01.bsb.lrz.de/portal/index.php/sof/article/view/8187.

- Karagöz, M. 1193/1779 senesi Rüsum Defteri’ne Göre Bazarcık-Tatarpazarı’nda Pirinç Üretimi. Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 2004, 14, 275–299. http://hdl.handle.net/11616/42633.

- Emecen, F. Çeltik, DİA, TDV (Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı) İslam Ansiklopedisi. Istanbul – Turkey 1993, 8, 265–266.

- Sarıkaya, H. T.T. 0008 Numaralı Tapu Tahrir Defteri’nin Transkripsiyonu ve Tahlili. Adnan Menderes Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, 1/1/2014. http://194.27.38.21/web/catalog/info.php?idx=52641099&idt=1.

- Sert, Ö. Environmental History of Rice Plantations in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire Between the 15th And 19th Centuries and Its Potential for Climate Research. J. Environ. Geogr. 2021, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hütteroth W-D. Ecology of the Ottoman lands. In The Cambridge History of Turkey. Vol 3.; Faroqhi SN, Ed.; Publisher: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 2006; pp.18-43. [CrossRef]

- İnalcik, H. Rice cultivation and the çeltükci-re'âyâ system in the Ottoman empire. Turcica, Revue d'Etudes Turques 1982, Tome XIV, 69–141. [Google Scholar]

- Beldiceanu, N. L'organisation de l'Empire ottoman (XIVe-XVe siècles). In Histoire de l'Empire ottoman; Robert Mantran Ed.; Publisher: Fayard, Paris, France, 1989; pp.129.

- Nesbitt, M.; Simpson, S.J.; Svanberg, I. History of rice in Western and Central Asia. In Rice: origin, antiquity and history; Sharma S.D. Ed.; Publisher: Science Publishers, Enfield, New Hampshire, USA, 2010; pp.308-340.

- TAŞ, K.Z. OSMANLI ÇELTİK ÜRETİM SAHASI OLARAK KONRAPA YA DA “OSMANLI SARAYININ NADİDESİ KONURALP PİRİNCİ”. Balıkesir Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 2020, 23, 1253-1268. [CrossRef]

- Ozkilinc, A.; Sivridag, A.; Coskun, A.; Yuzbasioglu, M. 367 Numarali Muhasebe-i Vilayet-i Rumili Defteri ile 114,390 ve 101 numarali icmal defterleri (920-937/1514-1530), t.I-II, Tirhala Livalari, Ankara 2007.

- Shariat-Panahi, S.M.T. Corinthia in the Ottoman period; Publisher: University of Thessaly Press, Volos, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shariat-Panahi, S.M.T. Vasilika and its region in the Ottoman period. In Sikyon I: the Urban Survey; Ioannis A. Lolos, Ed.; Publisher: Institute of Historical Research, Athens, Greece, 2021; pp. 642–681. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Agricultural census of 1911 (Thessaly and Arta). Publisher: Ministry of National Economy, Athens, Greece, 1914; p.71.

- Leake Martin William. Travels in Northern Greece. In four volumes, VOL. IV. Publisher: London, J. Rodwell, New Bond Street, UK, 1835.

- Saaty, TL. The analytic hierarchy process. Planning, priority setting, resource allocation. McGraw Hill, New York, USA, 1980.

- FAO. A framework for land evaluation. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Soils Bulletin, 1976, 32.

- Senecah, L.S. The Trinity of Voice: a framework to improve trust and ground decision making in participatory processes. J. Environ. Plan. Manag., 2023,. [CrossRef]

- Onitsuka, K.; Ninomiya, K.; Hoshino, S. Onitsuka, K.; Ninomiya, K.; Hoshino, S. Potential of 3D Visualization for Collaborative Rural Landscape Planning with Remote Participants. Sustainability, 2018, 10, 3059. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, X.; He, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D. Participatory Rural Spatial Planning Based on a Virtual Globe-Based 3D PGIS. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf., 2020, 9, 763. [CrossRef]

- Roque de Oliveira, A.; Partidário, M. You see what I mean? - A review of visual tools for inclusive public participation in EIA decision-making processes. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev., 2020, 83, 106413. ISSN 0195-9255. [CrossRef]

- Nasr-Azadani, E.; Wardrop, D.; Brooks, R. Is the rapid development of visualization techniques enhancing the quality of public participation in natural resource policy and management? A systematic review. Landsc. Urban Plann., 2022, 228, 2022, 104586. ISSN 0169-2046. [CrossRef]

- Hasanzadeh, K.; Fagerholm, N.; Skov-Petersen, H.; Olafsson, A.S. A methodological framework for analyzing PPGIS data collected in 3D. Int. J. Digit. Earth, 2023, 16, 3435-3455. [CrossRef]

- Lovett, A.; Appleton, K.; Warren-Kretzschmar, B.; Von Haaren, C. Using 3D visualization methods in landscape planning: An evaluation of options and practical issues. Landsc. Urban Plan 2015, 142, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, E.J. Designing Organizational Memory: Preserving Intellectual Assets in a Knowledge Economy. Decision Support Systems-DSS., 1997, 1-35.

- Arvanitidis, P.; Nasioka, F. From commons dilemmas to social solutions: A common pool resource experiment in Greece. In Institutionalist Perspectives on Development: A Multidisciplinary Approach, (Palgrave Studies in Democracy, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship for Growth); Vliamos S. and Zouboulakis M. Eds.; Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan, Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp.125-142.

- Bertacchini, Y. Entre information & anthropologie: le processus d’intelligence territorial. Revue, Les Cahiers du Centre d’études et de Recherche, Humanisme et Entreprise, 2004, 267. https://archivesic.ccsd.cnrs.fr/sic_00001058v1/document.

- Nikolaidou, S.; Kouzeleas, S.; Goussios, D. A territorial approach to social learning: facilitating consumer knowledge of local food through participation in the guarantee process. Sociol. Rural. 2023, 63, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colletis, G.; Pecqueur, B. Révélation de ressources spécifiques et coordination située. Économie et institutions 2005, 6-7, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham G.T.(coord.). Territoires apprenants. Une approche renouvelée de la construction des compétences sur le territoire. La Librairie des Territoires, 2022, 39-41 [en ligne]. [CrossRef]

- Rieutort, L.; Goussios, D. Un nouveau paradigme du developpement rural Europeen: apprentissages collectifs et territoires apprenants. In El futuro de la Europa rural: Emprendimiento, cultura y patrimonio; Martín Gómez-Ullate García de León, Eds; WANCEULEN Editorial, 2022; pp.11-41, ebook, ISBN 978-84-19388-58-2.

- Scott, J.; Johnson, T.; Mundell, M. Community memory: an internet based approach to enhancing community learning, knowledge management and public participation in local governance. In Proceedings of Which Public Administration in the Information Society, Brussels, Belgium, May 2000. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258399726.

- Pelissier, M.; Pybourdin, I. L'intelligence territoriale: Entre structuration de réseau et dynamique de communication. Les Cahiers du numérique, 2009, 5, 93-109. https://www.cairn.info/revue-les-cahiers-du-numerique-2009-4-page-93.htm.

- Saudan, M. Géographie historique: Histoire d'une discipline controversée ou repères historiographiques. Hypothèses, 2002, 5, 13-25. 5. [CrossRef]

- Girardot, J.J. Intelligence territoriale et participation. In Proceedings des 3e Rencontres TIC et Territoire: Quels développements? Lille, France, 14 May 2004, 149-161.

- Sandulache, C.E. Comment appréhender les nouvelles formes d’organisation du travail au service de l’innovation collaborative dans le cadre des territoires inscrits dans une démarche de stratégie intelligente?-Cas des tiers-lieux collaboratifs. Doctoral dissertation, Université de la Réunion, 25 February 2019.

- Bourret, C. Éléments pour une approche de l'intelligence territoriale comme synergie de projets locaux pour développer une identité collectiv. Projectics/Proyéctica/Projectique, 2008/1, 79-92. [CrossRef]

| Suitability Classes | Slope % | Distance from Ditches | Distance to River Enipeas | Distance to Source Xtouri |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanently unsuitable | >8 | >200 | 0-200 | 0-200 |

| Currently unsuitable | 3-8 | 150-200 | 200-500 | 200-500 |

| Marginal suitability | 1-3 | 100-150 | 500-1000 | 500-1000 |

| Moderate suitability | 0.5-1 | 10-100 | 1000-1500 | 1000-1500 |

| High suitability | 0-0.5 | 0-50 | >1500 | >1500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).