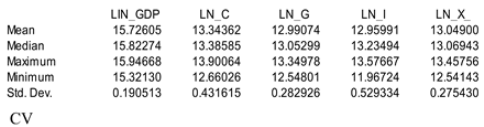

3.2. Data Analysis

The analysis in this study was conducted using data obtained from the official Saudi Central Bank open portal data. The variables used in the study were defined in detail using information from the World Bank. To carry out the analysis, the researcher utilized the EViews 12 software, renowned for its versatility and user-friendly features. This software effectively streamlines the tasks of data organization, visualization, and analysis.

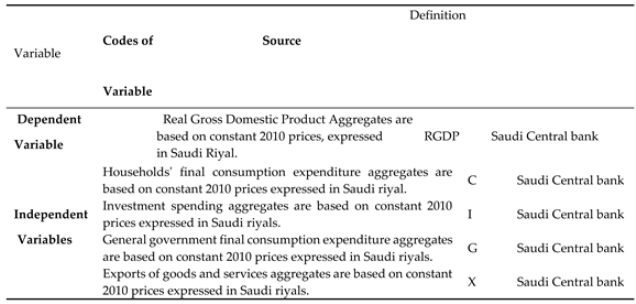

Definition of the Variables (World Bank).

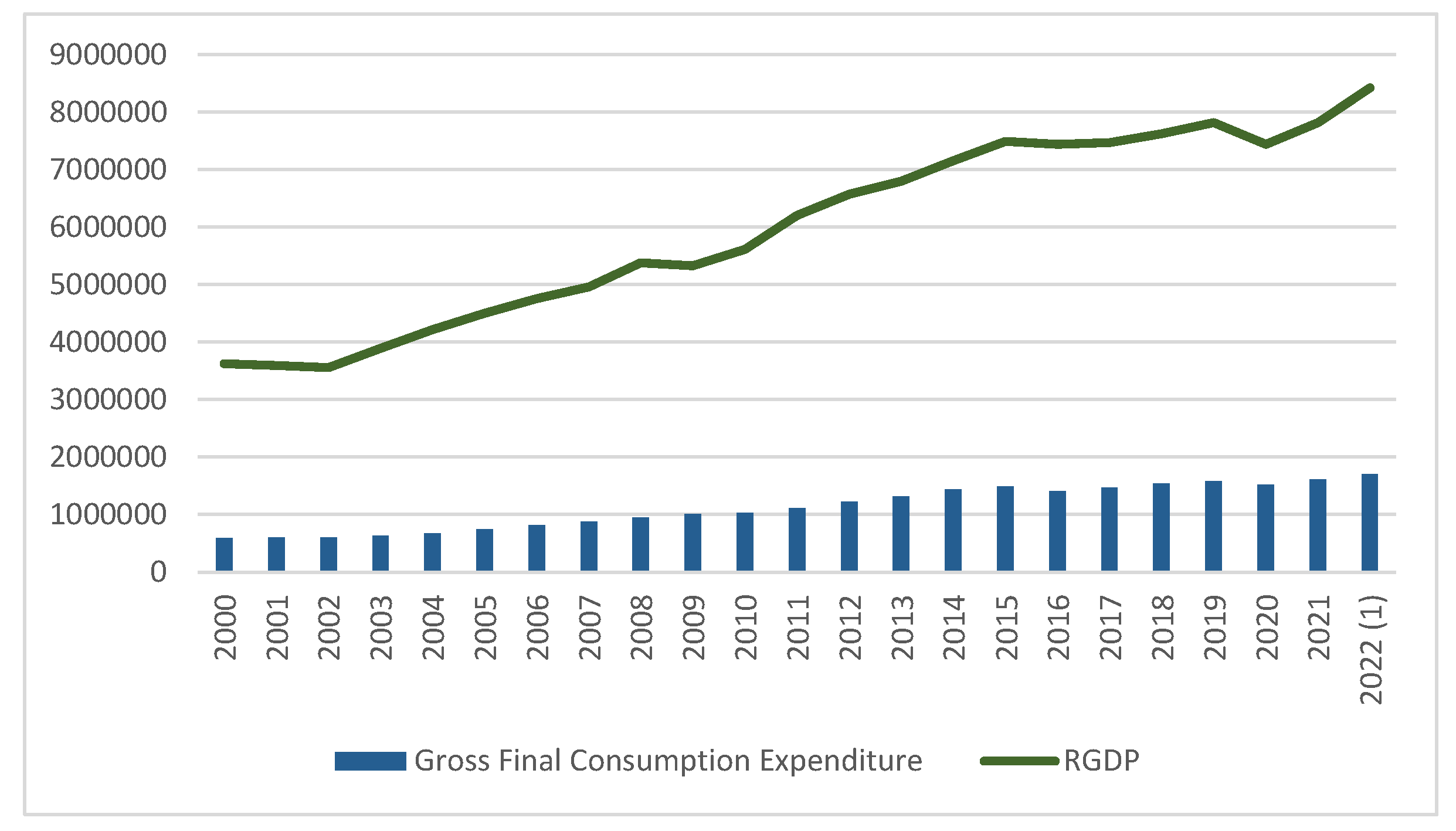

1. Economic growth (RGDP): RGDP, which stands for Real Gross Domestic Product, is the research's dependent variable. It serves as a comprehensive measure that considers inflation and accurately depicts the overall worth of goods and services generated by the Saudi Arabian economy in the year 2010. This metric is expressed in prices from a reference year and is widely recognized as constant-price, inflation-adjusted, or constant-Saudi Riyal (SR).

2. Private Final consumption expenditure (C): Denoted as (C), Household final consumption expenditure, also known as private Consumption, refers to the total value of goods and services acquired by households, encompassing durable products. This measure excludes the purchase of dwellings but incorporates imputed rent for owner-occupied dwellings. Additionally, it encompasses payments and fees made to governments in order to obtain permits and licenses. Notably, this indicator incorporates the expenditures of nonprofit institutions serving households, even if they are reported separately by the country.

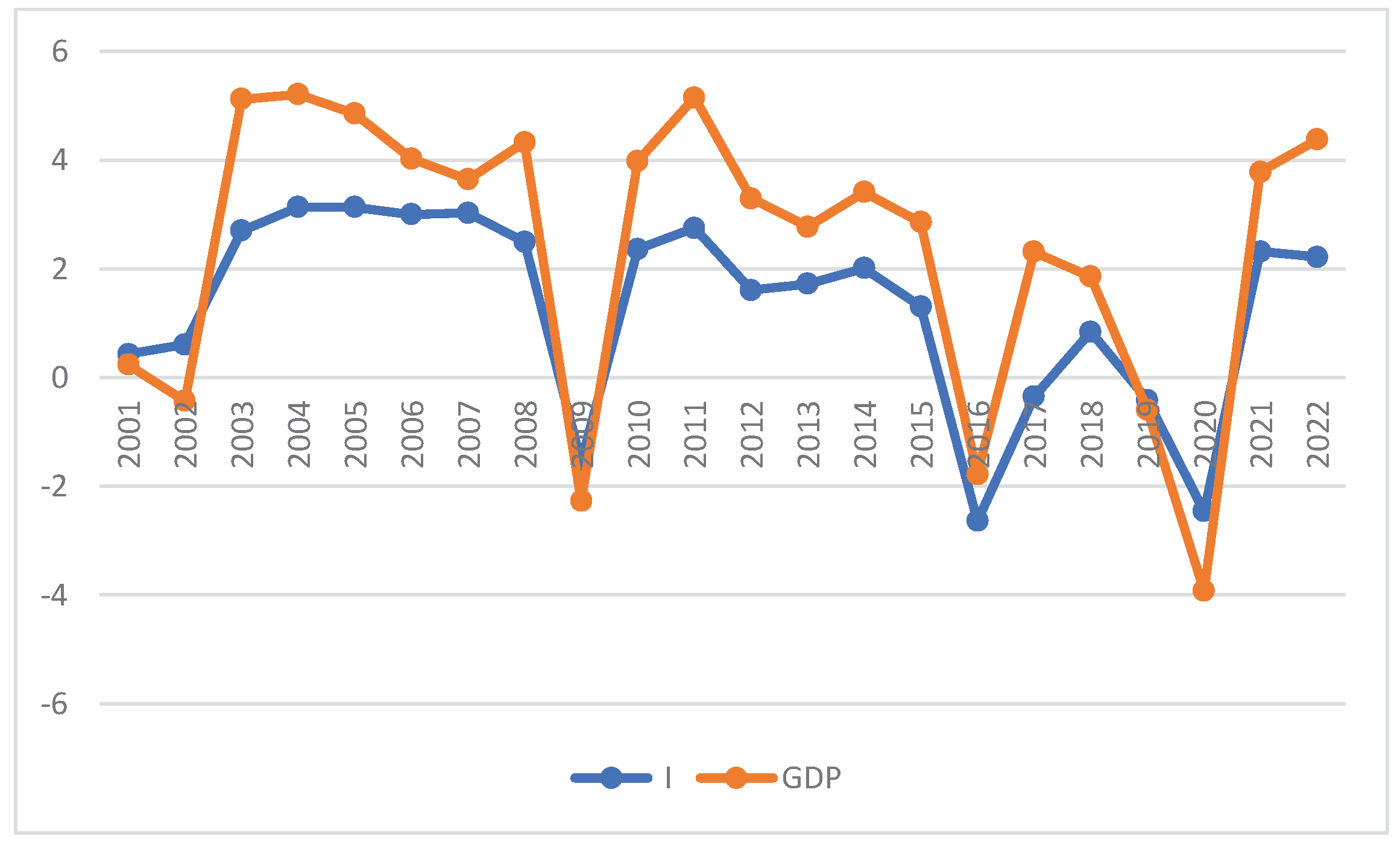

3. Investment spending (I): Denoted as I, gross fixed capital formation is a measure that accounts for investments made in a country's economy using constant local currency. This measure is based on aggregates calculated using constant 2010 prices and expressed in SR. Gross fixed capital formation encompasses various types of investments, such as land improvements, purchases of plant, machinery, and equipment, as well as the construction of infrastructure like roads, railways, schools, offices, hospitals, residential dwellings, and commercial and industrial buildings. Additionally, according to the 2008 System of National Accounts (SNA), net valuables acquisitions are also considered part of capital formation.

4. General government final consumption expenditure (G): Denoted as G, the general government final consumption expenditure is determined using constant local currency. This encompasses all current expenses made by the government for the acquisition of goods and services, including employee compensation. Additionally, it comprises a significant portion of the funds allocated towards national defence and security. However, it does not encompass military expenditures contributing to government capital formation.

5. Exports of goods and services(X): Denoted as X, exports are measured in a consistent local currency, SR. The aggregates are calculated using constant 2010 prices and are expressed in SR. The exports of goods and services encompass the total value of all goods and various market services provided to other countries. This includes the value of merchandise, freight, insurance, transportation, travel, royalties, license fees, and other services such as communication, construction, financial, information, business, personal, and government services. However, it does not include compensation of employees, investment income (previously referred to as factor services), and transfer payments.

6. Imports of goods and services (M): Denoted as (M), these are the imports of goods and services measured in a consistent local currency, specifically the Saudi riyal. The aggregates are computed using constant 2010 prices and are expressed in SR. Imports of goods and services encompass the total monetary value of all goods and other market services procured from the international community. This includes the value of merchandise, freight, insurance, transportation, travel, royalties, license fees, and other services such as communication, construction, financial, information, business, personal, and government services. However, it does not include compensation of employees and investment income, previously referred to as factor services, nor does it include transfer payments.

3.3. Econometric Methodology

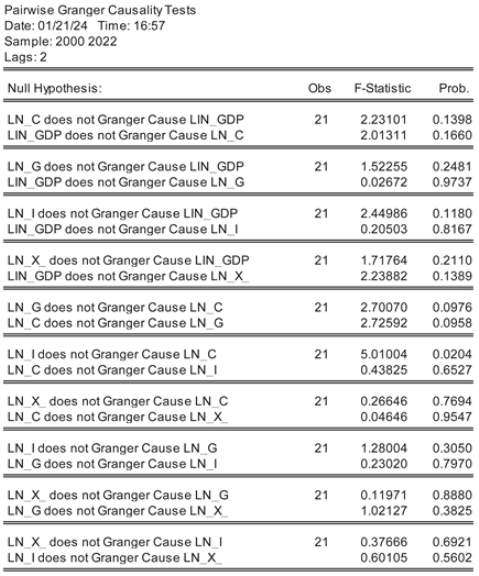

This research utilizes various econometric methodologies to tackle the unique obstacles presented by time series data, causality, and cointegration.

Table 1.

Description of Variables and Sources of Data.

Table 1.

Description of Variables and Sources of Data.

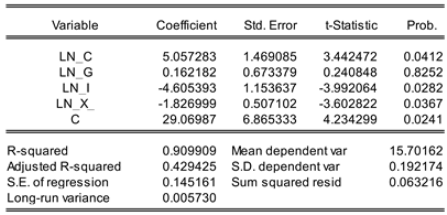

The dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) estimation method, the Johansen cointegration test, and the error correction model (ECM) are among the econometric techniques available for analysis. These methodologies are highly appropriate when examining the long-term associations, short-term dynamics, and causal connections between the expenditure components and the RGDP in Saudi Arabia.

Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares (DOLS):

DOLS, or Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares, is a statistical technique employed to estimate parameters in dynamic regression models involving time series data with potential integration. This method is particularly popular in the analysis of cointegrated time series, as highlighted by [

41].

The general formula for DOLS is:

where

∆Yt is the dependent variable at time t;

∆Xt The independent variable(s) exist at time t.

α is the intercept;

β is/are the coefficient(s) of the independent variable(s);

εt is the error term at time t.

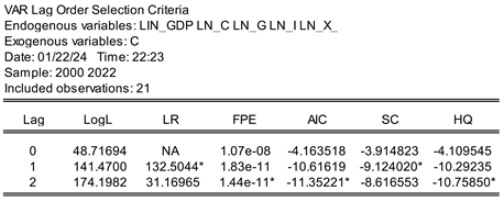

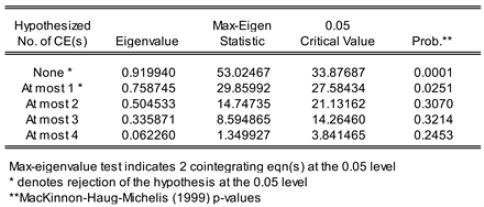

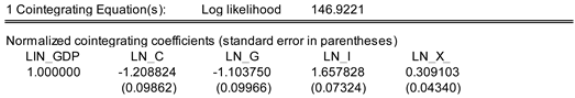

Johansen cointegration test

The Johansen cointegration test is a pivotal statistical tool in exploring the presence of cointegration among a set of time series variables, indicating enduring relationships among them. Primarily utilized in econometrics, this method involves the estimation of a vector autoregressive (VAR) model followed by conducting likelihood ratio tests to assess the model's validity.

The equation for the Johansen cointegration test is as follows:

where:

Δyt represents the differenced vector of time series variables at time t.

Π is the matrix of cointegration coefficients.

Γi is matrices of adjustment coefficients.

p is the lag length of the VAR model.

ϵt is the error term.

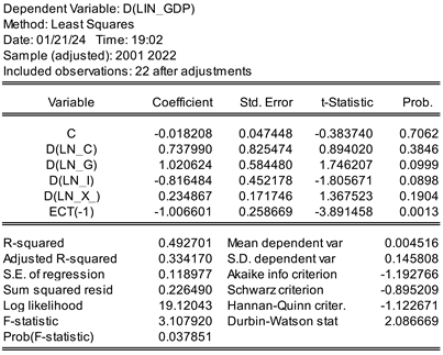

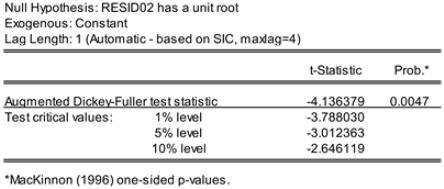

The Error Correction Model (ECM)

The error correction model (ECM) is a theoretical framework for examining the short-term and long-term interactions among variables in a cointegrated relationship. The fundamental formula of ECM is:

where:

∆Yt: short-term dependent variable changes at time “t”.

∆Xt: Short-term variations in the independent variable(s) at time point "t"

α: The intercept term indicates the constant effect on the dependent variable.

β1: The coefficient quantifies the rate at which the adjustment or correction mechanism operates, specifically in response to deviations from the long-term equilibrium observed in the preceding period.

β2: The coefficient linked to the lagged difference in the independent variable(s) is employed to correct deviations from the equilibrium state.

γ: The primary adjustment in the coefficient of the independent variable indicates the immediate impact of changes in the independent variable on the dependent variable. δ1: The lagged first difference coefficient in the dependent variable is responsible for capturing any persistence or autocorrelation.

δ2: The coefficient of the lagged first difference in the independent variable(s) accounts for potential persistence or autocorrelation effects.

εt: The error term denotes the unaccounted variability in the dependent variable during time "t".