1. Introduction

Ritualistic behaviors can occur in various forms, both in humans and in other animal species, and can range from culturally accepted and sustained behaviors to truly pathological ones, such as compulsions in humans and adjunctive behaviors in animals [

1,

2]. They seem to have in common the aim to cope with the unpredictability of the environmental circumstances and, at least in humans, the subjective feeling of being capable of - or responsible for - preventing a bad outcome (i.e., the so-called magical thinking).

In humans and in several other animal species, pathological ritualistic behaviors include motor sequences related to hygiene care and resources transport and storage. These motor sequences have been highly preserved during evolution, due to their function in thermoregulation, their protective value against parasites and diseases (hygiene care), and to their utility in case of shortage of essentials (resources transport and storage) [

3].

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic psychiatric disorder characterized by recurrent intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions) [

4]. As to the content of these symptoms, contamination obsessions and washing compulsions are prevalent in approximately 50-60% of OCD patients while clinical hoarding occurs in approximately 30% of them [

5].

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious respiratory disease that has greatly affected the world and was defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a pandemic on 11 March 2020 [

6]. Given the high prevalence of COVID-19 and its noteworthy global transmissibility, measures of restriction have been implemented with the aim of limiting the contagion as much as possible. The restrictive measures spanned from hygiene-related guidelines, such as social distancing, mask usage, and frequent handwashing outlined by the WHO, to the implementation of lockdowns as a preventive measure adopted by many governments [

7].

In Italy, two major COVID-19 epidemiological waves occurred in 2020, one during the spring and one during the autumn, which were accompanied by stringent restriction measures. In the period between these two waves, specifically during the summer months, the infection rate significantly decreased, leading to an almost complete lifting of the restrictions, and allowing people to resume their usual activities. The second wave, although less severe than the first, was likely facilitated by the increased social interactions during the summer vacation period [

8].

The combination of the fear of potential contagion and the sudden imposition of social isolation has created a strong atmosphere of depression, distress, and anxiety in the general population [

9,

10] and has triggered or worsened psychiatric symptoms in vulnerable populations, as in the case of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients [

11,

12,

13].

Several studies have examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on OCD symptoms, and the results have been varied. Some studies have reported a worsening of symptoms, while others have found no change or even an improvement.

The studies reporting a worsening in OCD symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown found an increase in obsessions related to contamination, health, and safety, and compulsions of cleaning, washing, and checking [

14]. This increase may be due to several factors, including increased anxiety and social isolation, as well as the new daily routines and restrictions imposed by the lockdown. Overall, 78% of studies reported an increase in OCD symptoms during the lockdown, while 22% reported no change [

15].

In a previous study from our group, we observed that the mandatory lockdown had an influence on the characteristics and presentation of OCD symptoms, highlighting the diverse and dynamic nature of the disorder, whose psychopathological expressivity is influenced by environmental circumstances. In particular, we found a partial transition from checking to washing symptoms in those patients who had already been diagnosed with OCD before the pandemic, whilst all the patients whose symptoms onset occurred during the pandemic predominantly displayed hoarding symptoms [

16].

In the present study, we followed the course of symptoms of a sample of OCD patients throughout the pandemic, with the hypothesis that this could help clarify the possible adaptive nature of OCD symptoms. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic can be considered a natural experiment in this respect, in light of the evolutionary value of the hygiene-related and resource storage-related behaviors as well as of the high evolutionary pressure represented by a catastrophic event such as a global pandemic. To this aim, we assessed the severity of OCD, anxiety, and depression symptoms as well as the level of insight of OCD patients throughout the different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Secondarily, we aimed at identifying the factors possibly influencing the symptom severity changes across the different timepoints.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

During the first mandatory lockdown in Italy, 102 OCD patients, diagnosed according to DSM-V criteria, were selected from the clinical records of the OCD outpatient clinic of the University Hospital “Federico II” in Naples, Italy. Among these, 46 (45%) agreed to take part in the study, while the remaining refused for personal reasons or were not reachable before the end of the lockdown. Inclusion criteria were that patients had been: i) visited during the three months preceding the pandemic outburst; and ii) found clinically stable at that time. The only exclusion criterion was the presence of any psychiatric comorbidity. The data for this study were collected at four time points: during the three months before the pandemic outbreak (T0); from 22 April to 18 May 2020, corresponding to the date of the ethical approval of the study by our ethics committee and that of the end of the first mandatory lockdown in Italy, respectively (T1); from 1 June to 30 September 2020, during a temporary elimination of restriction provisions (T2); and from 1 November to 31 December 2020, during the second mandatory lockdown in Italy (T3).

Measures and Procedure

Four rating scales were administered at the four time points: the Yale–Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) [

17], the Brown Assessment of Belief Scale (BABS) [

18], the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [

19] and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Y (STAI-Y) [

20]. The details of the study procedures are reported elsewhere [

8,

16].

Statistical Analyses

The scores of the clinical scales (Y-BOCS, BABS, BDI-II, STAI-Y) were compared across time by means of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. We computed Spearman’s correlation coefficients between patients' baseline characteristics (age, sex, education, illness duration) and the difference in the score of the clinical scales across time points. In the case of significant correlations, the OCD sample was split into two sub-samples based on the median score of the variable (greater or equal than the median value vs. smaller than the median value). Considering the increase of anxiety levels observed in OCD patients during the COVID-19 lockdown [

16], we also controlled for a possible moderating effect of anxiolytic drugs by comparing the scores of the clinical scales in patients taking vs. not taking benzodiazepines at T0. The level of significance was set at .05. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS v.25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA).

3. Results

We included an overall sample of 46 OCD patients (22 females; median age=37 years, IQR=25; median education=13 years, IQR=4; median illness duration=14.5 years, IQR=19.25). Detailed participants’ characteristics are reported elsewhere [

15].

Patients were treated with various combinations of benzodiazepines (n=36; 78%), SRIs (n=43; 93%), antidepressants other than SRIs (n=3; 7%), antipsychotics (n=10; 22%), antiepileptics (n=7; 15%), and lithium (n=3; 7%).

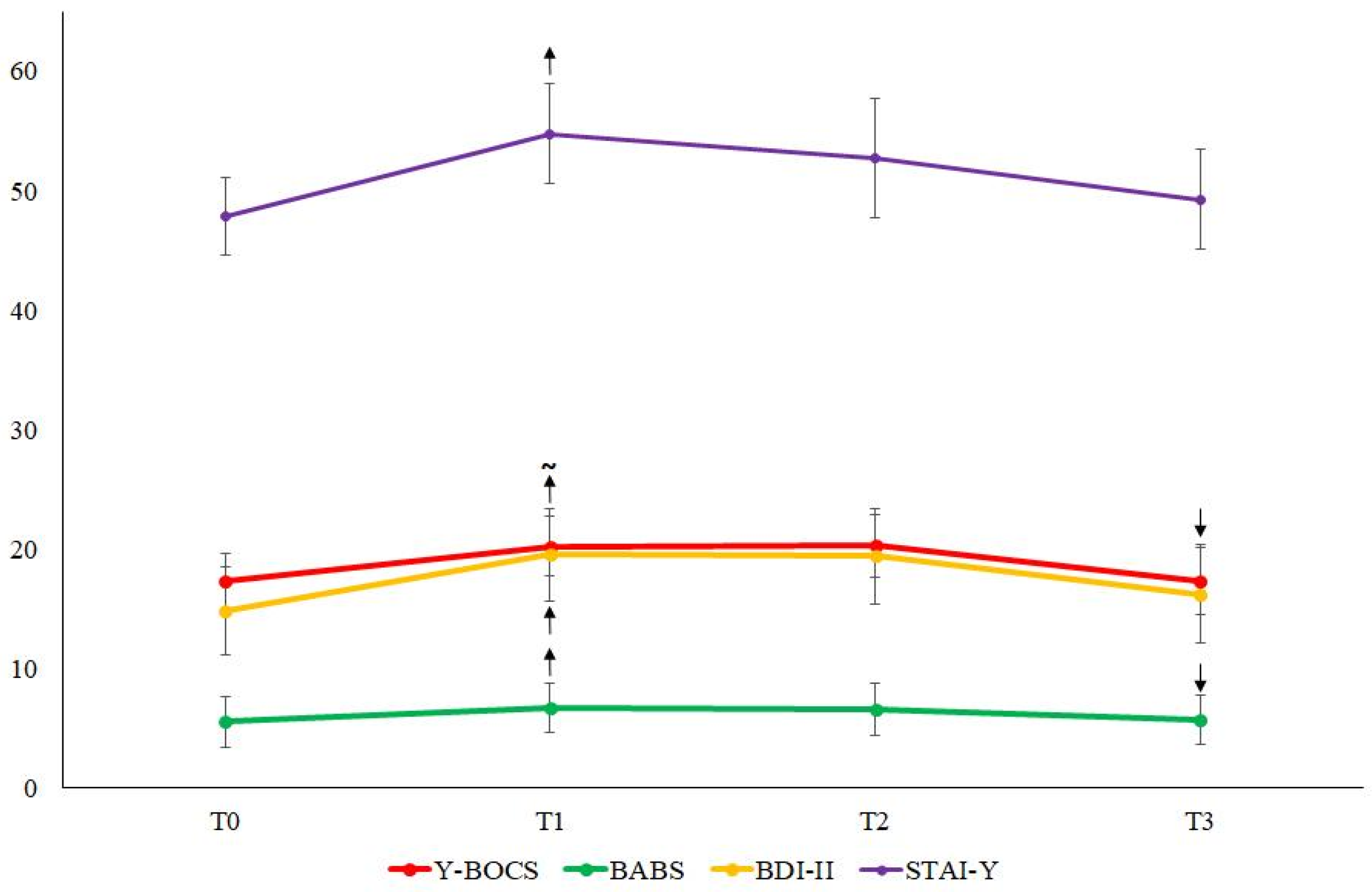

At group level, we found that Y-BOCS scores increased at T1 compared to T0, although this difference only approached statistical significance (median Y-BOCS=18.5, IQR=23.75 vs. 22.0, IQR=16.25; Z=-1.95; p=.05). The Y-BOCS scores did not differ between T1 and T2 (p>.05) but decreased significantly at T3 (median Y-BOCS=21.0, IQR=23.75 vs. 16.0, IQR=13.75; Z=-2.412; p=.016).

The BABS scores increased at T1 with respect to T0 (median BABS=2.5, IQR=9.25 vs. 4.5, IQR=11.0; Z=-2.199; p=.028), remained stable at T2, and decreased significantly at T3 (median BABS=4.5, IQR=10.25 vs. 3.0, IQR=9.25; Z=-2.409; p=.016).

Both the BDI-II (median BDI-II=10.0, IQR=15.5 vs. 14.0, IQR=24.5; Z=-2.968;

p=.003) and the STAI-Y (median STAI-Y=47.0, IQR=23.25 vs. 56.0, IQR=29.25; Z=-3.232;

p=.001) increased significantly at T1 compared to T0, then remained stable up to T3 (all

p>.05; see

Figure 1).

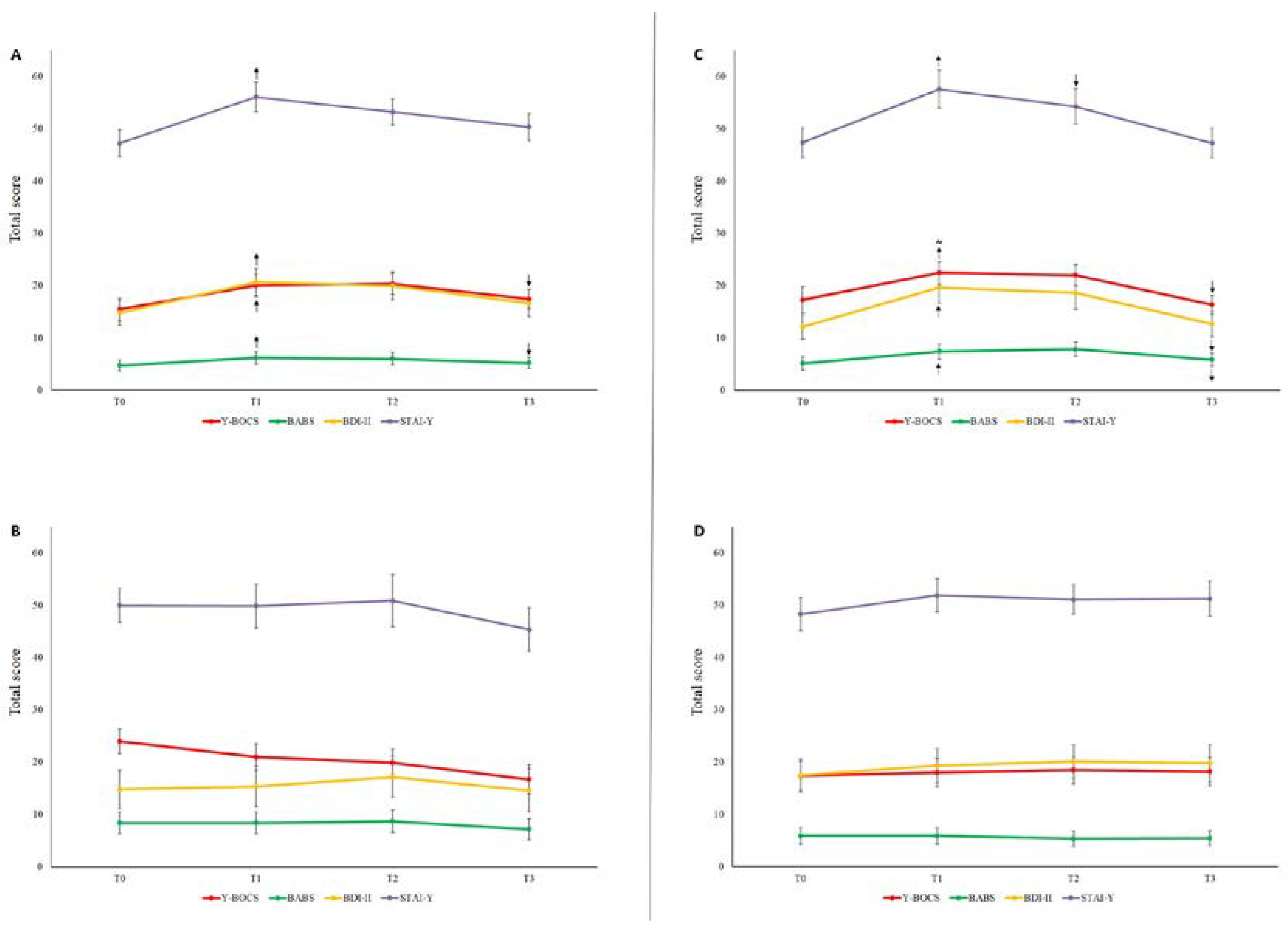

In patients taking benzodiazepines (n=36), the Y-BOCS, the BABS, the BDI-II, and the STAI-Y scores showed the same trend that we observed in the overall OCD group. In particular, the Y-BOCS and the BABS increased significantly at T1 (p=.010 and p=.028, respectively), remained stable at T2, and then decreased at T3 (p=.028 and p=.035, respectively). Similarly, the BDI-II and the STAI-Y increased significantly at T1 (p=.004 and p<.001, respectively;

Figure 2A). Conversely, no significant differences in any scale and any time point were observed in patients who did not use benzodiazepines (n=10; all p>.05;

Figure 2B).

The illness duration correlated significantly with both the difference in the Y-BOCS scores between T0 and T1 (ρ=-.403; p=.005) and between T2 and T3 (ρ=.336; p=.022), and the difference in the BABS scores between T0 and T1 (ρ=-.349; p=.018) and between T2 and T3 (ρ=.439; p=.002). Similarly, illness duration correlated significantly with both the difference in the STAI-Y scores between T0 and T1 (ρ=-.319; p=.031), whereas the correlation with the difference in the BDI-II scores between T0 and T1 and only approached statistical significance (ρ=-.289; p=.051). Moreover, age correlated with the difference in the BABS scores between T3 and T2 (ρ=.375; p=.010). No further significant correlation has been observed (all p>.05).

Once split the overall OCD sample into two sub-samples based on the median value of illness duration, we found that in patients with a shorter illness duration (n=23) the Y-BOCS and the BABS scores showed the same trend that we observed in the overall OCD group. Particularly, the BABS increased significantly at T1 (p=.028), whereas the Y-BOCS only showed a trend to increase (p=.052). Both Y-BOCS and BABS remained stable at T2 and decreased at T3 (p=.023 and p=.011, respectively).

The BDI-II and the STAI-Y, instead, showed a slightly different trend to the overall OCD group. Specifically, both increased significantly at T1 (p=.005 and p=.003, respectively); thereafter, the STAI-Y decreased significantly at T2 (p=.031) and remained stable at T3 (p=.211), whereas the BDI-II only decreased at T3 (p=.025;

Figure 2C). No significant differences in any scale and any time point were observed in patients with longer illness duration (n=23; all p>.05;

Figure 2D). Importantly, out of the 36 patients treated with benzodiazepines, only 15 (42%) had a shorter illness duration; out of the 23 patients with shorter illness duration, 15 (65%) were treated with benzodiazepines, and 8 (35%) did not; out of the 23 OCD patients with longer illness duration, 21 (91%) were treated with benzodiazepines, and 2 (9%) did not.

4. Discussion

The main results of the present study are that anxiety, depression, OCD symptoms and insight of OCD patients worsened during the first COVID-19 lockdown, remained quite stable during a temporary elimination of the restrictions, and improved during the second pandemic-related lockdown. The changes observed in the whole sample were attributable to two specific subgroups of patients, those taking benzodiazepines and those with recent OCD onset.

In the entire study group, we observed a non-statistically significant worsening of obsessive-compulsive symptoms and a statistically significant worsening of insight during the first lockdown, compared to the pre-pandemic period. Subsequently, a significant improvement was observed in both OCD symptoms and insight between the temporary stop of the restrictions and the second lockdown. Slightly different patterns were observed for anxiety and depressive symptoms, which increased during the first lockdown but did not show significant decreases throughout the rest of the analyzed period.

There are different possible explanations for the described symptoms course. Clearly, the first lockdown was the event that impacted most the psychopathological status of the patients, causing significant symptoms worsening. This is consistent with other published studies on the short-term effect of the pandemic outburst [

21]. The psychological distress produced by the sudden disruption of patients’ daily routines and the concomitant perception of a substantial threat to the survival of all mankind might account for this worsening. In fact, the increase of symptoms was observed in all the assessed psychopathological dimensions, even suggesting that it reflects an adjustment reaction not specific for the clinical population under study.

On the contrary, the fact that the symptoms severity remained unvaried during the temporary abolition of restrictions, and despite the optimistic claims concerning the epidemiological data, can be explained with the cognitive inflexibility and the hyper-prudential cognitive style characterizing OCD patients [

22], that probably kept them away from the general looseness towards the risk of contagion that was present in Italy during the summer of 2020. In fact, we can hypothesize that OCD patients still perceived the risk of contagion as very high during that period. Consistently, the symptoms improvement observed in concomitance with the imposition of the second lockdown can be interpreted as the effect of the sense of relief occurring when a rule that patients considered highly necessary was actually promulgated. Moreover, it is possible that an additional source of reassurance was represented by the succession of news, spread during that same period (i.e., November-December 2020) that the vaccine against COVID-19 was almost ready to be marketed and that the beginning of the vaccination campaign was approaching.

Turning to the subgroup analyses that we have performed on our data, we observed that two clinical features of the patients in the examined sample were associated with the statistically significant changes of symptoms observed at the different timepoints: the benzodiazepines use at baseline (before the pandemic) and the duration of illness.

In fact, all clinical scores of patients taking benzodiazepines significantly increased during the first lockdown and significantly decreased during the second lockdown. In contrast, patients not using benzodiazepines did not show significant differences in any scale at any time point (

Figure 2A-B). Even if benzodiazepines are not a first-line treatment of OCD, their efficacy in this category of patients has been documented in scientific literature, as they were reported to reduce OCD symptoms and improve patients' quality of life, suggesting that benzodiazepines can be an effective treatment for a subgroup of OCD patients with an anxious diathesis [

23,

24,

25]. Consistently, a possible explanation for the findings of our study is that the benzodiazepine use might be a proxy of an anxious diathesis characterizing a subgroup of patients, and that this proneness to anxiety made them more worried about the environmental circumstances and more susceptible of psychopathological worsening in case of adversities. In terms of clinical management and public health policies, this could imply that OCD patients taking benzodiazepines might deserve special attention in case of increased environmental stressors, being a population at higher risk of psychopathological worsening.

Another clinical feature that greatly influenced the symptoms course during the pandemic was the duration of illness. In fact, only the half of our sample including the patients with a shorter duration of illness showed a significant worsening of symptoms during the first lockdown and a significant improvement during the second one. On the contrary, the graphs showing the symptoms course of the half of the sample with higher illness duration are virtually flat (

Figure 2C-D). This finding might help elucidating some mechanistic aspects of OCD psychopathology and disease progression over time. In fact, our results suggest that at the beginning of the illness the cognitive-emotional balance of the OCD patients is more unstable and so susceptible of changes under the pressure of external circumstances. Afterwards, with the progression of illness, it is possible that the symptoms of OCD patients become less affected by the environment. This partial detachment from the potential stressors might have more than one explanation. Firstly, it is possible that the allostatic mechanisms that have developed since the onset of illness have led to a ceiling effect, which, in turn, makes further symptoms worsening less likely. Another possible explanation is that patients with a chronic OCD become so entrenched in the intrinsic psychopathological mechanisms of their own OCD that they become less careful and less worried about the external threats.

To our knowledge, there are no other published studies correlating the duration of illness with the response to environmental stressors in OCD patients. It is possible that the conflicting data among the published studies regarding the effect of the pandemic on OCD symptoms were due to differences in sample selection particularly in terms of duration of illness.

Viewed as a whole, our results add information about the psychopathology of OCD, by suggesting two specific factors that might influence the variability of symptoms of OCD patients under the pressure of adverse external circumstances, namely the anxious diathesis and the duration of illness. Besides the heuristic value of this observations, they also have possible practical implications, as they indicate two possible sub-populations of OCD patients more at risk of symptoms worsening in case of adverse contingencies, and therefore deserving specific clinical attention. Moreover, should these results be confirmed in larger populations of OCD patients, the clinical features indicating a higher psychopathological risk could be included in more complex machine learning algorithms to be used for the purpose of public health policies [

26].

Finally, from an evolutionary standpoint, we can reverse the above perspective and speculatively hypothesize that the anxious diathesis and the shorter illness duration might be considered an advantage for those OCD patients displaying these features over the other OCD patients and, maybe, even over the healthy population. In fact, a previous study from our group indicated that OCD patients that had previously displayed prevailingly checking symptoms during the first lockdown turned to hygiene-related ones, and that new-onset pandemic-related OCD patients mainly displayed symptoms of hoarding of essential goods and supplies. Since both hygiene-related and hoarding symptoms make the contagion factually less likely, we can hypothesize that the anxious diathesis and the shorter illness duration could have been protective and evolutionarily advantageous if the COVID-19 had been even more deadly than it actually was, and the precautions taken by the general population had not been sufficient to protect them from the contagion.

This study presents some methodological limitations. Firstly, the small sample size may have hindered our ability to detect significant differences during the follow-up, including the progression of OCD symptoms. This was due to the short time frame between the approval of the ethics committee and the conclusion of the first mandatory lockdown in Italy. In fact, during this short period and in the unprecedented stressful circumstances of the lockdown, a considerable number of patients selected from their medical records were either unreachable or unwilling to participate, due to personal or health reasons, leading to a low recruitment rate for the study (approximately 45%). Furthermore, the decision not to include patients who had not been visited within three months before the onset of the pandemic also restricted the sample size. This decision was made to eliminate the potential confounding influence of significant life events that may have occurred between a more remote time point and the lockdown. However, despite the small sample size, the results of post hoc power analyses revealed that our findings are robust. Another methodological shortcoming, possibly biasing the results of the study, is the adoption of different procedures for the collection of baseline data (clinical records) and follow-up ones (video-calls). Lastly, we chose not to include in the study OCD patients with psychiatric comorbidities, since our goal was to unveil specific mechanistic aspects of OCD psychopathology. However, considering the high rate of comorbidity characterizing the OCD population, the exclusion of patients with comorbid conditions might have hindered the generalizability of our results.

5. Conclusions

The severity of psychopathological symptoms of OCD patients was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Fluctuations were observed according to the different phases of the pandemic and were most evident in OCD patients taking benzodiazepines and in those with recent-onset OCD. On one hand these results point to specific subpopulations of OCD patients deserving special clinical attention in case of environmental adversities, on the other hand they indicate which subpopulations could have an evolutionary advantage from an increase of their hygiene-related and hoarding pathological behaviors in case of highly contagious and deadly pandemic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D.; methodology, G.D. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, A.M., M.V.P.; data curation, G.D., A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D., M.V.P., C.I., A.M., and M.M.; writing—review and editing, G.D., A.M., M.M., M.V.P., C.I., F.I., B.D.O., and A.d.B.; visualization, G.D. and A.M.; supervision, F.I., B.D.O and A.d.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Activities of the University of Naples Federico II (protocol code 152/20, 22 April 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors warmly thank Alessandra Capuozzo, Umberto D’Aniello, Gianpiero Gallo, Hekla Lamberti, Adalgisa Luciani, Teresa S. Mariniello, Fabiana Megna, Lorenza Maria Rifici, and Antonella Tafuro for their assistance throughout the different phases of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tonna, M.; Ponzi, D.; Palanza, P.; Marchesi, C.; Parmigiani, S. Proximate and Ultimate Causes of Ritual Behavior. Behav. Brain Res. 2020, 393, 112772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilam, D.; Zor, R.; Szechtman, H.; Hermesh, H. Rituals, Stereotypy and Compulsive Behavior in Animals and Humans. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006, 30, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonna, M.; Marchesi, C.; Parmigiani, S. The Biological Origins of Rituals: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 98, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed.; 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S.A.; Eisen, J.L. The Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1992, 15, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19.

- Passavanti, M.; Argentieri, A.; Barbieri, D.M.; Lou, B.; Wijayaratna, K.; Foroutan Mirhosseini, A.S.; Wang, F.; Naseri, S.; Qamhia, I.; Tangerås, M.; et al. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 and Restrictive Measures in the World. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 283, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, G.; Pomes, M.V.; Magliacano, A.; Iuliano, C.; Lamberti, H.; Manzo, M.; Mariniello, T.S.; Iasevoli, F.; de Bartolomeis, A. Depression and Anxiety Symptoms “Among the Waves” of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Adjustment Disorder Patients. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, A.; Sampogna, G.; Giallonardo, V.; Del Vecchio, V.; Luciano, M.; Albert, U.; Carmassi, C.; Carrà, G.; Cirulli, F.; Dell’Osso, B.; et al. Effects of the Lockdown on the Mental Health of the General Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy: Results from the COMET Collaborative Network. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Xiaoyang Wan; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; McIntyre, R.S.; Choo, F.N.; Tran, B.; Ho, R.; Sharmah, V.K.; et al. A Longitudinal Study on the Mental Health of General Population during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity Journal [Revista En Internet] 2020 [Acceso 22 de Febrero de 2022]; 87(2020): 40-48. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 40–48.

- Alonso, P.; Bertolín, S.; Segalàs, J.; Tubío-Fungueiriño, M.; Real, E.; Mar-Barrutia, L.; Fernández-Prieto, M.; Carvalho, S.; Carracedo, A.; Menchón, J. How Is COVID-19 Affecting Patients with Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder? A Longitudinal Study on the Initial Phase of the Pandemic in a Spanish Cohort. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; He, Y. Variation in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Symptoms and Treatments: A Side Effect of Covid-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ameringen, M.; Patterson, B.; Turna, J.; Lethbridge, G.; Goldman Bergmann, C.; Lamberti, N.; Rahat, M.; Sideris, B.; Francisco, A.P.; Fineberg, N.; et al. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 149, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzick, A.G.; Candelari, A.; Wiese, A.D.; Schneider, S.C.; Goodman, W.K.; Storch, E.A. Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E.; Drummond, L.; Nicholson, T.R.; Fagan, H.; Baldwin, D.S.; Fineberg, N.A.; Chamberlain, S.R. Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms and the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Scoping Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 132, 1086–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Urso, G.; Magliacano, A.; Dell’Osso, B.; Lamberti, H.; Luciani, A.; Mariniello, T.S.; Pomes, M. V.; Rifici, L.M.; Iasevoli, F.; de Bartolomeis, A. Effects of Strict COVID-19 Lockdown on Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Compared to a Clinical and a Nonclinical Sample. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, W.K.; Price, L.H.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Mazure, C.; Delgado, P.; Heninger, G.R.; Charney, D.S. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. II. Validity. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1989, 46, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, J.L.; Phillips, K.A.; Baer, L.; Beer, D.A.; Atala, K.D.; Rasmussen, S.A. The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale: Reliability and Validity. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantley, P.J.; Dutton, G.R.; Wood, K.B. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and the Beck Depression Inventory-Primary Care (BDI-PC). In The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Instruments for adults, Volume 3, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, US, 2004; pp. 313–326. ISBN 0-8058-4331-0. (Hardcover). [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.; Gorsuch, R.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y1 – Y2); 1983; Vol. IV. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, L.P.; Balachander, S.; Thamby, A.; Bhattacharya, M.; Kishore, C.; Shanbhag, V.; Sekharan, J.T.; Narayanaswamy, J.C.; Arumugham, S.S.; Reddy, J.Y.C. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Short-Term Course of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2021, 209, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruner, P.; Pittenger, C. Cognitive Inflexibility in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Neuroscience 2017, 345, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcevic, V.; Berle, D.; do Rosário, M.C.; Brakoulias, V.; Ferrão, Y.A.; Viswasam, K.; Shavitt, R.; Miguel, E.; Fontenelle, L.F. Use of Benzodiazepines in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 31, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelow, B. The Medical Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Anxiety. CNS Spectr. 2008, 13, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.; Hollander, E. A Review of Pharmacologic Treatments for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Psychiatr. Serv. 2003, 54, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’urso, G.; Magliacano, A.; Rotbei, S.; Iasevoli, F.; de Bartolomeis, A.; Botta, A. Predicting the Severity of Lockdown-Induced Psychiatric Symptoms with Machine Learning. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).