1. Introduction—FAIR and CARE Principles of Data Management Policy

The open science agenda has already improved access to scientific results and brought about a much-needed shift in the academic community, allowing Bourdieu’s theories about how access to certain kinds of cultural assets—that is, financial means—creates and maintains class hierarchies to be quite easily applied1. Having the financial resources to access paywalled journals and papers can occasionally make a big difference in one’s ability to pursue a successful career in science. Open science in is therefore a fantastic step toward reducing some of the inequalities existing between scientific communities. This could be true for open access journals, despite the fact that the pro and cons are still being evaluated and negotiated2 (although here also the distinction is made between true and fake open access3, 4 . FAIR principles are also embraced as being unproblematic, despite the voices that share different experience5,6.

The FAIR principles (FAIR stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) were introduced on the open science agenda in 20167, after a workshop held in Leiden, Netherlands in 2014. They are formulated with the aim to enable digital resources to become more FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) for machines and thus also for humans8.

National initiative for open science in Europe has published a document where the principles were explained in Croatian language. (

https://training.ni4os.eu/pluginfile.php/3637/mod_resource/content/0/HR-NI4OS%20-%20FAIR.pdf)5. Open science and its goals are promoted in Croatian context via various platforms and initiatives, web sites, blogs and conferences

9, PUBMET conference held annually in Zadar being quite important one. The HORIZON and many other prestigious or competitive funding agencies have made open data (FAIR principles) a prerequisite for receiving funding. Given the fact that SSH still have a quite marginal position within interdisciplinary funding such as EU funding anyhow

10, and that this position is mainly held by economics, business, management and law (only 5 %of arts and humanities), it can be stated that the RDMP for these small percentage will hold the similar position. However, the prerequisite will be same for everyone, thus continuing to consolidate the weak position SSH in general take on the funding market worldwide. The Croatian Science Foundation strives to follow the trends set by European Commission and its funding agencies. From March 15 2022 Croatian Science Foundation (CFS) announced the Research Data Management Plan (RDMP) will be a mandatory part of the application documentation for all future projects financed by the Croatian Science Foundation. (

https://hrzz.hr/plan-upravljanja-istrazivackim-podacima-za-projekte-hrvatske-zaklade-za-znanost/3.

11 Although it brings more requirements to researchers the main aim is to improve the research methodology and science in general. In the paragraph online there is nowhere explicitly mentioned that the data should be made FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), but the following sentence "Sharing research data increases the visibility, citation of publications and collaboration among scientists." clearly signals that the open science agenda is behind it.

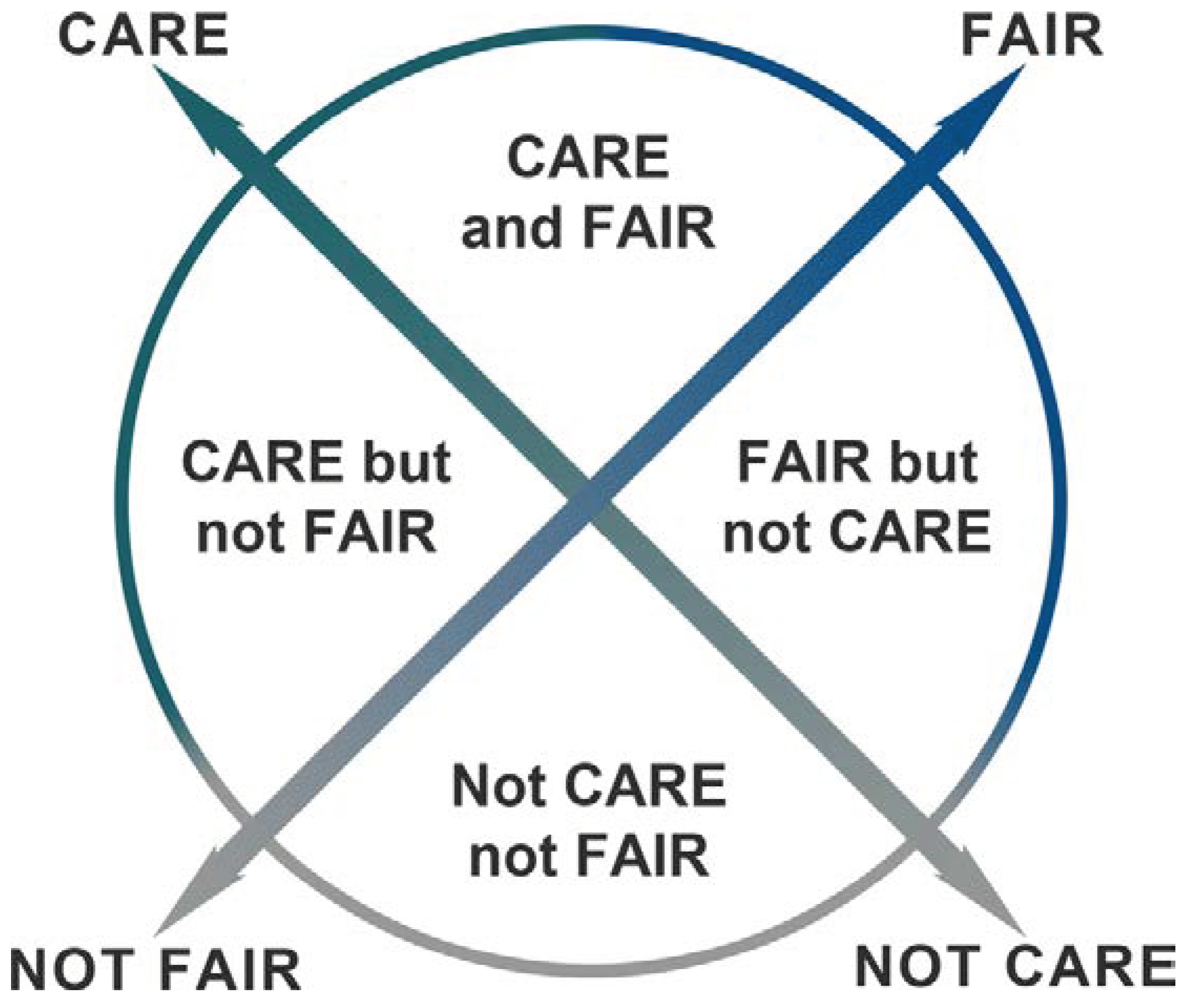

However, funding agencies need to incorporate the newer or discipline-specific approaches into data management policy that do not exclusively take FAIR into account.

Data we as researchers receive should really be treated with care, especially when exploitation is in question. And exploitation is quite often if the indigenous data are in question. Therefore, there is no wonder that only 3 years after the FAIR principles were launched, the CARE principles for Indigenous Data Governance were launched as well, after important scholarly and public debate12.

They relate to "the people and purpose of data; Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics, and their respective sub-principles", and especially are aimed at data from the communities that were "Historically plagued by data inequities and data exploitation, Indigenous Peoples" (ibid). They try to assure that the data collected from Indigenous people will result in" tangible benefits for Indigenous collectives through inclusive development and innovation, improved governance and citizen engagement, and result in equitable outcomes" 13..

CARE principles refer to "data, information, and knowledge, in any format, that impact Indigenous Peoples, nations, and communities at the collective and individual levels; data about their resources and environments, data about them as Individuals, and data about them as collectives" could be expanded to all communities from whom we gather data for our professional gain14.

However, my opinion and the initial hypothesis is that compliance with FAIR principles cannot be achieved across all disciplines equally and that CARE principles should not be connected with indigenous people. The research of data repository carried out by Dunning, Smaele, M., & Boehmer15 analyzed 37 repositories. Cases of certain datasets (described as personal in social sciences) did not comply with FAIR principles, although they could have. This caused the authors to conclude that "disciplinary norms have developed specific ways of making data accessible that do not always tally with the FAIR principles". The authors conclude that "Compliance should not be seen as a stick, but rather a desirable goal, with the recognition that some of the guidelines are open to interpretation and debate. Indeed, the term compliance, at least for some of the facets, is misguided. Rather the facets provide targets that will help with getting recognition and reward for the publication of data. Given that the EU is now including FAIR guidance as part of the its H2020 program, it is important that funders and peer reviewers take heed of this, so the principles do not get misused as sanctions (ibid: 187).

Besides impossibility to achieve total compliance with the FAIR principles (not that this is needed at all!) some researcher reveals that there is also something called "Selfish Scientist Paradox"16 where the same group of researchers (usually individual scientist, the survey was conducted among life science research community) is happy to receive shared data, but reluctant to provide16. Their research showed that junior researchers were reluctant to share their data prior to publications (but were willing to consider data sharing in case of publishing in high-ranking journals), and that senior researchers were considering gaining funding (or collaboration under certain conditions) as strong incentives for sharing data16.

I would like to broaden the application of CARE principles on any population researched by qualitative methodology. The qualitative research, especially ethnological and anthropological encounter between interlocutor and researcher is sometimes very deep and emotional and, in some cases, it can mark the beginning of a long-lasting friendships. The trope of the "field" is connected with the people we meet "there" and with our relations with "them". They are not just data-providers and we do hope that we are not just a waste of time for them. This space of confidentiality, empathy and emotion is perceived as unique for each particular encounter in qualitative research. Therefore, it is difficult to simply share the data as if you never ever had any emotional involvement in the process. Also, the bumpy road and unpredictable ways in which you have managed to find and engage an interlocutor and gather data are important part of your identity as researcher. Field research is the most important trope of you as a researcher l an important initiation place for any anthropologist. Therefore, the data collected in this encounter, in my opinion, deserve to be treated with CARE principles.

The study "Attitudes on open access to raw data" among Croatian ethnologists and cultural anthropologists – materials and methods.

Having all the above mentioned in my mind, my personal experience and doubts I wanted to get more information about the opinions, practices and attitudes of working colleagues. In order to get as much as possible variety of opinions I decided to use quantitative methodology. In January 2024 I set a questionnaire by using google forms and send it to 145 e-mail addresses of working ethnologists and cultural anthropologist that I had knowledge about (Croatian Ethnological Society has less than 300 members, and some of them are not professionals. There are between 150 and 180 paying members, including several students, and a lot of non-paying retied colleagues. I on purpose excluded both students and retired colleagues in order to collect the current practice. Therefore, my sample was purposeful and quite small. However the community of practice od working ethnologist, anthropologist and folklorist in Croatia is quite small. Within two weeks I have received 33 responses, i.e. 22, 7%. Majority of the respondents were women (87,9%, 12,1 % male), which corresponds with the reality in which it is a quite feminized profession. The questionnaire consisted of 18+ 1 (the last one was left for those who wanted to ad something) questions, whit the first 3 being related to sociodemographic type of data I considered important for the questionnaire: gender, age and work.

Then the set of question followed where I was interested in the practice of my colleagues about the they inform public about the results of their research, the way they keep their raw data, and about the existing practice of sharing one owns data and using other researchers’ data as well.

I was interested in attitudes toward data sharing practices as well, in general. Therefore, this part of questions included the opinion about who should, in their opinion have access to raw data. Also, I was interested in their opinion about data sharing practice in general, Since I assumed that the answer to this question is far too complex, I added the new one where I asked respondents to elaborate the previous answer.

The second part of the questionnaire consisted of six statements (idea taken from Damalas et al 2018)16 where, by using Likert scale I wanted to see the level of the agreement with particular statements that referred to hypothetical situations.

The statements were:

I would agree to share the raw data before publication

I would agree to share data if this is a prerequisite for financing

I would agree to share raw data to achieve the goals of open science

I support the open science goals of sharing raw data

I would agree to share raw data if it guarantees publication in high-ranking scientific journals.

I would agree to share raw data, if it allows me to cooperate with respected scientists

Only one statement asked for general opinion, while others asked for respondent to put his/herself in a particular hypothetical situation. The last question was yes/no question where I asked if the y think the data should be shared under certain conditions. The following question was open question where the respondents had a place to explain their opinion/attitude.

The last question was put in order for the respondents to add something that I as a researched did not think of.

The results of the study "Attitudes on open access to raw data" among Croatian ethnologists and cultural anthropologists.

As I mentioned earlier, within 3 weeks I received 33 responses and I base my conclusions on these responses.

Majority of the respondents were women (29) and only 4 man (87,9 vs 12, 1%). The age of the respondents was from 29 to 62, which reflected the fact that I wanted to include working population of Croatian ethologist and anthropologist exclusively. Majority of the respondents were from academia and research institutions, museums (and it included several responses from museum pedagogist) an only one response was from cultural heritage protection service.

In the first set of questions the respondents had to provide information about the ways they inform the public about the results of their research. 90, 9% responses stated that it was in scientific papers, book chapters or similar and 45,5 % referred to exhibitions and catalogues, 18, 2% included blogs and social media posts, while 15, 1% named documentaries and serials, 15,1 % named public (and popular) lectures and for a. Only 3% named TV and 3% radio, and one respondent (3%) mentioned open repository such as PhD thesis collection.

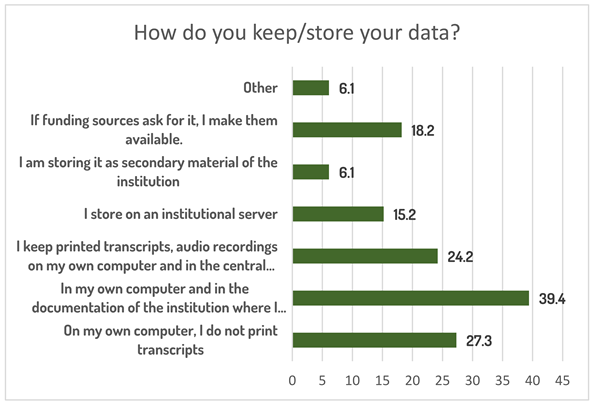

I was also interested in ways the data collected has been stored among Croatian ethnologists and cultural anthropologist. The responses to this question were: I keep the data in my PC, I do not print transcripts (27,3%); I keep the data in the computer and in the documentation of the institution where I work, I do not print transcripts (39, 4%)

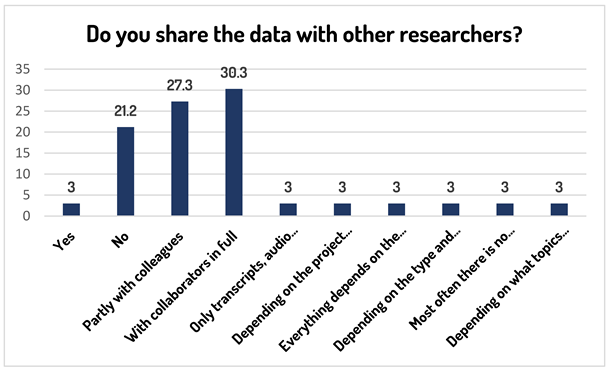

With following question I wanted to see to what extent the practice of sharing exists among Croatian ethnologists and Cultural anthropologists.

Majority of answers fell in the yes section (where the options yes, partially with colleagues, and with collaborators in full) stood for 60, 6%. (altogether). 1%5 OF THE respondents reported not sharing data, while the rest actually contextualized the answer within particular situations. The answers that were added by respondents included: depending of the project propositions, Everything depends on the research, the topic, the propositions of the project and the consent given by the interlocutors, depending on the sensitivity of the dana, Depending on what topics are discussed and what is the agreement with the interlocutors.

One respondent (3%) claimed that there is no interest in sharing and that he/she would share with colleagues.

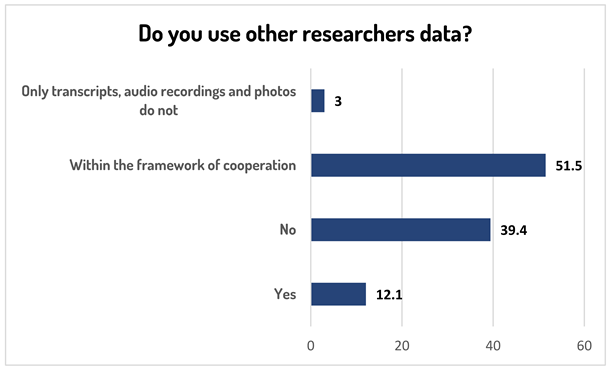

The following question was about the practice of using other researchers’ data.

Majority of the answers stated that it happens within the cooperation. Together with the rest who claimed that they share data it consist 60,6 %-. Only 39, 4 % do not share data.

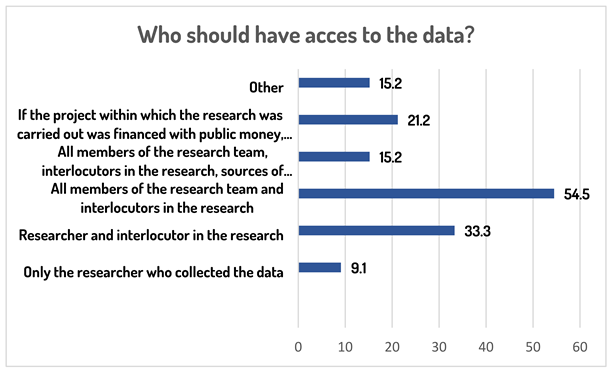

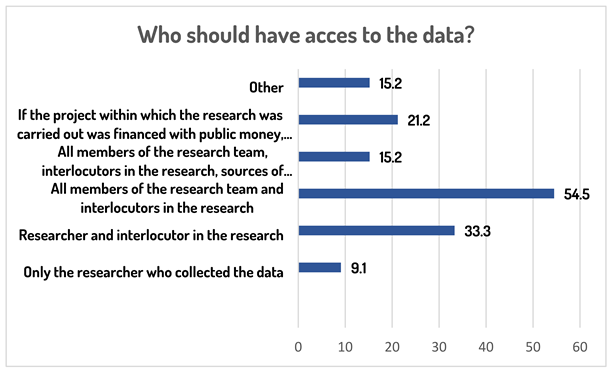

The opinions were asked for two questions. Who should have access to data, and should the data be shared?

More than 50% (50,5%) think that researcher from the team and interlocutors should have the access to data, and 33, 3 % think that access to data should be granted only to the researcher and interlocutor. 9;1% think that only the researcher should have the access to data. 15,2 % think that the sources of financing (regardless of the fact if they are private or public) should have access to data as well, - All members of the research team, interlocutors in the research, sources of research funding (public and private). 21,2 % of the respondents think that "If the project within which the research was carried out was financed with public money, then all collected data should be publicly available".

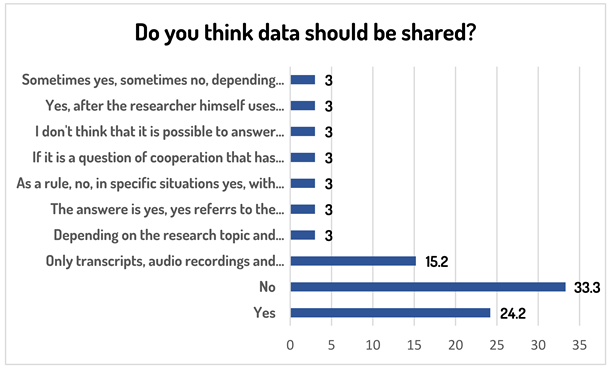

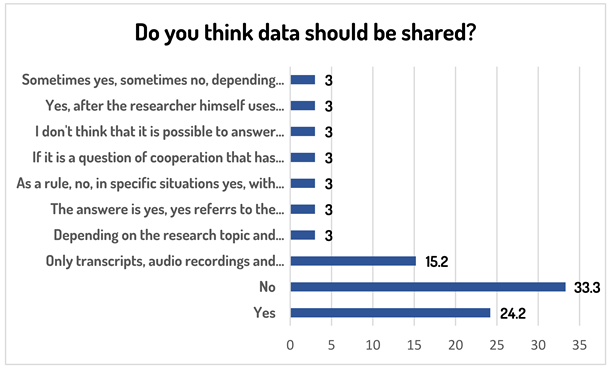

When asked if the data should be shared the majority said no – 33,3%. However, here as well the majority of the answer fell within the yes section – Where 24,2% said the data should be shared, and 15.2% specified that this should related only to transcripts, not audio tapes and photographs. However, here also 7 people (21%) expressed the complexity by adding explanatory sentences in "other" section: Depending on the research topic and agreement with the interlocutor; the answer is yes, yes refers to the research and the researched group (the latter refers to themselves), s a rule no, in specific situations yes, with strict observance of the indicated method of protection; If it is a question of cooperation that has several members within the research/project; I don’t think that it is possible to answer these questions with an exclusive answer. I think that everything depends on the research, the topic and the participants); Yes, after the researcher himself uses everything, he needs, so that the publication of the original work is not prevented, because someone used the first collected data in the meantime; sometimes yes, sometimes no, depending on the research topic and context.

The open question was asked to enable elaboration of the previous question ((do you think data should be shared?). The complex and elaborated answers were given. Majority of the respondents however referred to the fact that data, if shared, should be shared with collaborators and team members, even then some think the data should be anonymized or simply described the process of keeping the data in their institution.

"If I am working on a project or research in a team, I share data (recordings, transcripts and photos) with colleagues."

"If there is an agreement between the researchers at the beginning of the project, I share the data in the form of an anonymized transcript."

"The practice that I practice according to the rules of the institution where I work, and with which I agree in principle: the research team has access to the raw data, with storage in the documentation of the institution that is the holder of the research project, and the participants in the research at their own request."

"I believe that it can be useful to share because it will make it easier for us to speed up our work, but it must be under clearly defined rules."

"If the topic does not involve different power relations and cannot put the person involved in the research in an unenviable position, and if the context is known to those who will use the data, then I think it is good to share the data. This is usually between team members who are researching the same topic, know the context, and by sharing data they save time and get a broader insight into the issues of the topicthey are researching,"

"I believe that raw data should be shared, but only within the research (project) group, and with the researched in the part that refers to them themselves (copies of material collected in contact with them)."

"The question is not clear, with whom should they be shared? Previously I already said yes, to some extent, with the team I was researching with, otherwise no."

The other set of answers stressed the sensitivity and confidentiality of the data collected, together with the need to grant protection and anonymity to those who provided this kind of data.

"Care should be taken when dealing with sensitive topics and to protect the interlocutor"

"During the conversation, the informant can tell us, for example, personal things that are not necessarily related to the topic of the conversation. Such things are (at the request of the informant or at the discretion of the examiner) omitted from the transcript."

"I work with very sensitive data and I cannot be sure that someone will not assess the identity of the person to whom the document and/or the content of the interview refers."

"Within qualitative research, everyone is confidential, the interlocutors can be easily recognized, scientific research is not a gossip column!!!!"

"Anthropological research in practice has very broad topics and spectrums of possibilities. If we work with vulnerable groups on sensitive topics or with very small easily recognizable communities, then it is not easy to categorically ensure the principles of data sharing. In principle, I believe that it is necessary to share data, but only when it does not inconvenience our participants and when they themselves have clearly chosen to do so. In the case of sensitive topics, I believe there should be a certain moratorium on raw data, transcripts, audio recordings and other collected material. This moratorium can be conceived in a similar way to how archivists work with personal materials or sensitive data such as hospital records. They may become available for research after a certain period of time."

The more elaborated answers usually were against sharing the data and included explanations such as impossibility to achieve complete anonymization, especially in small communities:

"In principle, I am against the sharing of raw data, not because I am against open science, but because I believe that in the case of cultural anthropology and ethnology, and especially when researching certain topics (e.g. taboos) or marginalized and unprotected groups, the ethical principles of the profession and the guarantee of the anonymity of the interlocutor must have primary primacy and a prerequisite for everything else. So, for example, when researching small communities where everyone (re)knows each other, sharing an audio tape cannot guarantee the anonymity of the interlocutor (because one’s voice is unique and recognizable), as well as sharing other meta data recorded as an audio recording and a transcript in which they are mentioned in the conversation and other biographical elements and snippets from the interlocutor’s life that reveal his identity and which the GDPR law does not foresee or protect."

Also, the attitude that research interview is an authorial act, act of confidentiality between researcher and interlocutors that cannot be just used for the second time, because of the possible superficial or even incorrect interpretation:

"Interviews are an authorial act between two or more participants. The second researcher does not always have to understand the context of the interview and it is possible that the data will not be interpreted correctly. The interviewer and the interviewee necessarily develop some interaction, deeper or more superficial, and it is unique to each individual interview. The teller decided to share his information and time with a certain researcher, without going into the motivation. It is much more acceptable to me that raw data is not handed over, but just published and structured. The raw data could possibly be subjected to a time limit, that is, to be used as raw data only after the agreed-upon time distance has passed, with the mandatory indication of the available context data. I believe that the biggest problem of using raw data "from second hand" is of an ethical nature, precisely because of the possible wrong or superficial interpretation."

"Some go even further by stating that in case of qualitative research the agenda behind open science goal related to data sharing unachievable, since it is not possible to use these data out of the context and since the data collected are not repeatable and comparable."

"Ethnographic research is complex and often intimate in nature, biographical and inseparable from the context of its origin. That being said, the transcript can appear in one of three versions - it can be arranged for consultation and sharing, and it can serve as an image of the audio track. Since it is a conversational relationship that does not register repeatable and totally comparable data that can be extrapolated and used out of context, I am of the opinion that sharing data is counterproductive and dangerous."

Other respondents stress the fact that whatever technique we use it is impossible to protect interlocutor from small communities. The same respondent also stresses the need to rely on Code of Ethics of the discipline first and to show responsibility toward the researched community and interlocutors:

"Anonymization and similar techniques for the protection of interlocutors in many cultural anthropological research areas do not ensure sufficient protection of individuals or the community as a whole (for example, in small communities, statements can often be unambiguously linked to a person). The Code of Ethics of HED (Hrvatsko etnološko društvo, ie. Croatian Ethnological Society), AAA (American Anthropological Association), etc., in all phases of research work directs responsibility to the researcher himself. This is because only the researcher knows (situationally and contextually) and can assess the sensitivity of each obtained data as well as the potential harm to the interlocutor and the community."

Some respondents see the need firstly to define raw data, and stress the fact that personal notes in anthropology are data as well:

"I think that it would be necessary first of all to define what "raw data" is. Namely, if we are talking about the transcripts of the conversation, I think it is not a problem to share and make them available to others, of course if it is not a sensitive topic when the identity of the interlocutor must be protected. But, raw data can also be field notes that are often imbued with own observations that can change over time, be completely wrong conclusions, or be made up of personal attitudes and thoughts that you don’t want to share with others. In this context, I answered the previous questions that I do not share raw data and I believe that it should not be shared. In the rest of the questionnaire, I will answer as if it were transcripts of the conversation."

One respondent admitted that we need to have a wider discussion about the issue, and one actually named the solution FAIR principles offer – to share metadata only.

"I certainly believe that it is necessary to share them, it is just a matter of question with whom and in what format. A possible transitional answer is to publish information about the existence of specific data within some database with the suggestion that interested parties contact the institution that owns the raw data."

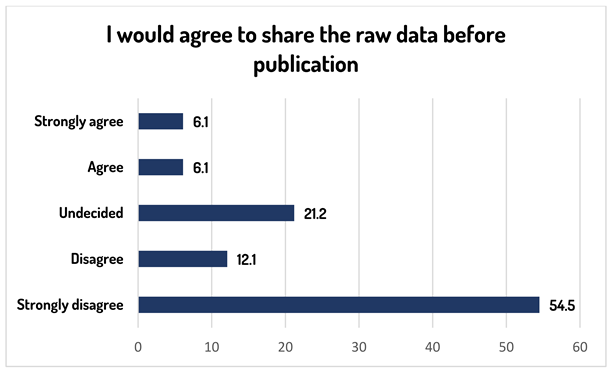

The next set of statements shows that over 50 % (66,6%) of respondents is against sharing the data prior to publication, while 12,2% would not mind sharing the data prior to publication.

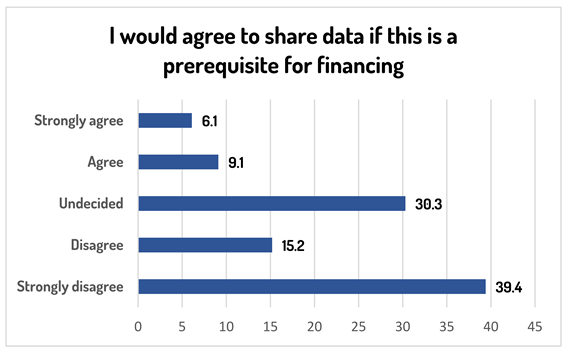

If sharing data was to be a prerequisite for funding than again, according to collected responses, 54,6 % of respondents would not consider data sharing, while 15,2% would consider data sharing.

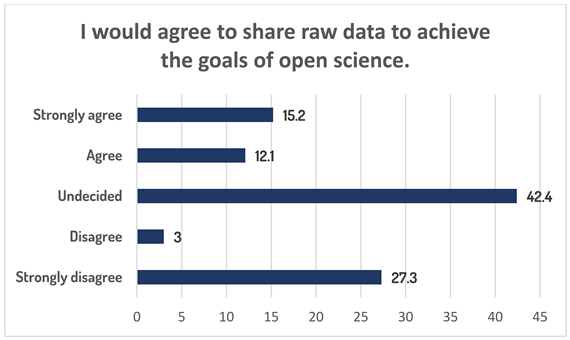

The statement related to sharing data as a way of achieving the goals of open science had most undecided respondents – 42,4%, reflecting the situation that the ideas and concepts od open science related to data are not very well known withing the researched community. 30,3% would not agree to share data in order to achieve the goals of open science, while 27,3 % would share the data.

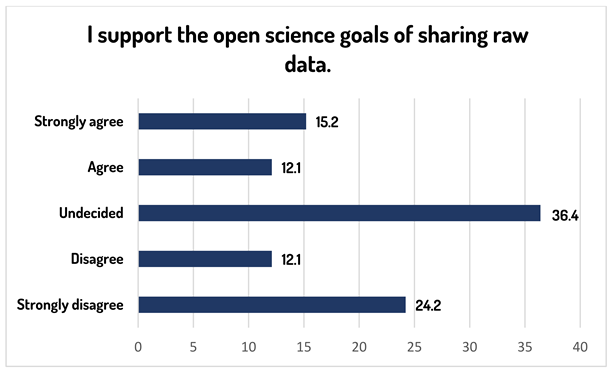

27,3 % of the respondents support the goals of open science related to sharing raw data, 36,3 % does not support these goals, while the individually largest percentage falls within the category of undecided (36,4%).

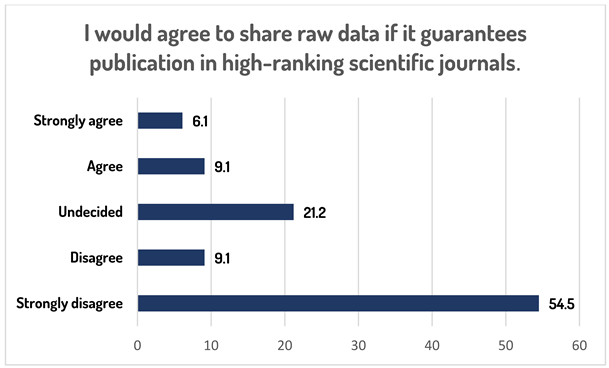

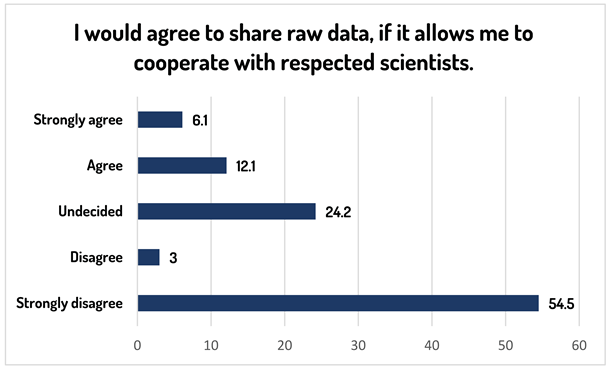

The following two questions, taken from, were asked in order to see to what extent are Croatian ethnologist and cultural anthropologist ready to compromise their ideas in order to achieve advancement of some kind.

High percentage - 63, 4 % - would not agree to share data if this could guarantee them the publication in high -ranking journals. On the other side there are 15,2% that are willing (or at least willing to admit so) to do so. There are 21,2% of respondents that opted for undecided option.

Almost the same percentage of respondents reported that they would not agree to share raw data if this could allow them to cooperate with respected scientists (57,4%). 18.,2% of the respondents reported that they would not be willing to do so., while there are 24,2% of those being undecided.

The answer to the question if the data should be shared under certain conditions is

"yes" according to 84,8% of respondents and "no" by 15,2 %.

Since the answer to this question is also not simple, the open question followed it, with the request made to the respondent to elaborate/explain their answer.

For majority of the interlocutors the data sharing clearly relates primarily to the existing practices of sharing the data with the interlocutor(s) and colleagues with whom the collaboration on the particular project/topic providing the data is done. This is often described as data sharing with colleagues you trust. (Usually with them you collaborate). Some stress the need to clearly state this in the Informed consent, as it is also partially practiced.

"For example, in the case of working on a project where several researchers are working on the same topic. But in any case, respecting the degrees of protection requested by the interlocutor."

"Yes, if colleagues from the same institution are involved in the research."

"I would share them with co-workers who adhere to ethical codes, not with corporations that can use them for profit (even if those corporations are financiers)."

"Exclusively with colleagues with whom we closely collaborate on the same topic."

"If the conditions of identity protection, non-disclosure of certain particularly controversial information are met, the data should definitely be shared with colleagues."

"If there is a possibility that already existing raw data can be supplemented/upgraded and processed in more detail by an external person/institution, I believe that collaboration is essential."

"In addition to the previous explanation, I would like to note that I believe that partial sharing of raw data with scientists and colleagues from a joint project is justified because it contributes to the overall research of a certain topic or area, analysis and interpretation of data with the aim of ensuring excellence. However, I consider it important that, when creating the Informed Consent form, this should be clearly indicated to the interlocutor, who must be familiar not only with the research objectives, but also with whom the data will be available."

"Collaborators work closely together on projects, they go to the fields together, they even do some interviews or focus groups together, transcribing can also be divided, so you transcribe interviews made by other team members, write joint papers, present at congresses based on research results. Data sharing is the basis of good cooperation and project teamwork."

Majority of the answers are marked with care for the interlocutor primarily, not so much with the goals of open science. The emphasis is on the protection of the interlocutor, and to the do no harm policy.

"Protection should be ensured for both the interlocutor and the researcher."

"I think that there should be a regulation that will specify the conditions of data use in order to somehow protect the work of the person who collected the data, and also make the data available to other scientists for use."

"They should be shared, but with complete protection of the identity of the interlocutor."

"Only if the researcher assesses that he does not endanger the participants in the research and himself."

"Only if the researcher estimates that they can be useful for some research and give a contribution without compromising the integrity of the research participants. Although it would be best not to do this if it is possible, because mostly these data are published and publicly available."

"It depends on the type of research and collected data. It is easier to share data if it concerns some social knowledge, and much more difficult and problematic if it concerns private experiences."

"As I stated earlier, there must be regulations and practices that regulate the use and that serve above all to protect the people we work with when it is necessary and justified by research."

"Keeping the confidence of the informant - examiner if we know that the recordings have content that was obtained in confidence and with the request that it not be used publicly."

"I believe that the sharing of raw data should depend on the sensitivity of the topic and agreement with the interlocutor."

"They should be shared with the consent (sometimes not only consent but precisely the wish/aspiration) of the researched, but not during but after the end of the project, i.e. the publication of the works resulting from the "raw data" in question. Admittedly, the answer depends very much on the type of raw information; in principle it is "yes", but in many concrete examples it can also be "no" (e.g. assessment that the publication may harm the researched, despite their willingness to share the data, or e.g. if the raw data contain important elements not thematized in other works, etc.)"

"Raw data may contain some information that the whistleblowers themselves, for example, do not want anyone to ever see if anonymous interviewing has been arranged. Often, as researchers, we have to write down additional details to make it easier to find the context and a reminder of who told us what, but this should also be noted somewhere especially for those who will later use this information so that in their future publications they do not reveal more than what was agreed or necessary. In addition, there is sometimes a question of the ethics of research attitudes that may harm certain groups of people if they differ from previous attitudes based on the same raw data and this should also be specifically mentioned when storing such data as raw for further use."

However, there are researchers that are clearly against data sharing and some of them acknowledge the fact that ethnography is a special cognitive strategy and therefore the data collected cannot be treated the same way as numbers and unpersonal data.

"As in the previous answer, I consider the sharing of data in ethnography to be a missed way of understanding ethnography as a cognitive strategy."

"They do not need to be made available, I answered one previous question to another, namely I keep the data with me, and in written form (because I need to print it for easier reading) but I do not store it in the institution."

Of course, there are also anthropologists and ethnologists who do not see any problems in data sharing:

Raw data should be shared in any case. Just as we have access to the data in the archives, so we should enable others to access our data. Of course, in addition to solving ethical issues, sensitive information and extracting the transcript of the conversation from the field notes."

However, the attitude that the final decision should be left to the interlocutors seems to be quite ubiquitous:

"Depending on the topic and interlocutors. They determine what can and must be public."

"Only with the consent of the person to whom the data refer."

"It may possibly depend on the research topic, but all answers are personal and may reveal something that the interlocutor does not want."

"The respondent or teller must be familiar with the term "raw data" and its further distribution within open access. This is a prerequisite for agreeing to an interview. Raw data should not be shared afterwards, if the interlocutor was not previously informed. It is common to introduce the teller to the purpose of the research, which is almost always limited to a certain topic, and to collect "raw data" for tellers can be too general and vague."

Other opinions collected reflect diverse attitudes toward data sharing, one particularly interested, in my opinion, because it refers to the fact of producing digital waste. Other reveal quite pragmatic approach of not creating a wasted material.

"The fact is that we researchers, regardless of the initial commitment and desire to objectively process the chosen topic, are prone to subjective interpretation that supports our initial assumptions. In this sense, all data may remain unused and would be useful to another researcher or user. However, it is also a fact that part of the material collected through research is very often "unusable" due to the quality of the interlocutors, so it is also possible to ask whether we are creating a kind of digital waste by publicly publishing such material."

"If the researcher plans to use the data for his work, it is logical that he will not share it. If he does not intend to publish the data, it is better to make it publicly available."

"I just want to emphasize that my thinking and attitude stems from the belief that in our research, the protection of the interlocutors should be primarily ensured, as well as (to some extent) equality of relations. If all raw data are available to everyone, there is a fear that it will be difficult to find interlocutors in the research of "tricky" topics. I also wonder how misuse of such data will be ensured. And finally, in the context of cultural anthropology and ethnology, the raw data obtained from the field are the result of the interaction of two people (researcher and interlocutor), thus they are contextual in nature. Another researcher might get different answers to the same questions in a conversation with the same interlocutor. For this reason, I do not necessarily find justification for the use of raw data by other researchers, especially in other projects and analyses. In this case, the use and analysis of raw data makes sense only if the research is based on the anthropologist/ethnologist himself and his approach to the field."

"From my own work experience, I know that many raw data from research in Croatia (not only ethnologists and anthropologists) are with researchers on private computers, external hard drives, printed out on shelves at home, in offices and the like. It would be necessary to increase researchers’ awareness of more careful and at the same time more open storage of this information, which can serve other researchers as well."

2. Discussion

The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth

As a researched skilled primarily in qualitative methodology struggling always with the interpretation of data collected, especially in the light of what we call "order imagined" vs. "Order achieved" i.e. the difference between the reality and the narratives we are able to collect, the ethical consideration were not the only ones that worried me.

I just imagined myself being an interlocutor interviewed for such non-profit repository where my data will be made accessible for someone in the future. I asked myself who will be authority to decide who will have the right to access my data where I speak about my own personal experience of misogyny and chauvinism in the particular scientific context in Croatia? How much would I tell knowing that everyone (or even worse: someone in particular) might get access and maybe even misuse the data I provided. Of course, I might be a brave insider wishing to reveal the ways power can be misused in the Croatian scientific community (probably very similar as in any other hierarchized scientific community in the world) but still – if my intentions were those, I might be choosing some other ways to do it. Maybe I will be willing to speak openly and, similar to some sensitive archival data, decide that it can be made publicly open after my death. I do not know; but I would be really careful and the data would be, without any doubt, auto censored.

Of course, not all the narratives collected by anthropologist and ethnologist are of such problematic and sensitive nature. Usually, laypeople perceive the work of anthropologist and ethnologist as connected with "non-problematic" stories such as traditions and customs that are perceived as a source of pride and dignity for the community. In my experience majority of people in such cases decide to reveal their identity, with full names and surnames. On the other hand, other people will be quite discrete about almost everything, including the non-problematic heritage. However, even those "nice" "traditions and heritage", such as e.g., wedding traditions, might contain some very intimate ore even socially stigmatized patterns of behavior (e.g. premarital sex, abortions, etc.). And people do differ.

Research ethics obliges the researcher to state his/her intentions quite clear to the potential interlocutor. The interlocutor is, via the research information (leaflet) familiarized thoroughly about the ways in which the data will be used and kept. And after being informed, the interlocutor can give informed consent – where he or she decides about his anonymity (and potential use of pseudonym), about the transcripts and audio tapes (if he or she would like to receive them and how). The informed consent in signed form is something relatively new in Croatian ethnological and anthropological context. It used to be "gathered" verbally, i.e., usually recorded after verbal explanation of the purpose of the research and the ways the data will be used (as parts of exhibition labels, in posters and oral presentations, or published in catalogues, articles and/or books). The ethnologists and anthropologists (and other disciplines collecting qualitative data in Croatia (me included, especially during my work at the museum) simply asked the interlocutor if s/he agrees to being recorded. I never started an interview without this "I give my consent/I agree) sentence. Of course, the option to stop the interview or to skip any question was always provided. Although this was used only occasionally by my interlocutors, it did happen from time to time. Some even did not want to be recorded at all, and then we had to rely on our writing skills. Sometimes the interlocutor would, after the end of the interview, add something that s/he did not want to be recorded. Usually this was something delicate, very private or maybe even the unofficial explanation of an event, sometimes completely different from what was stated while being recorded. This would end up being the juicy element of the interview and sometimes it was only for our ears only and we were asked not to use it in our work or at least not to connect this information with the interview with them (regardless of the fact that the anonymity was always an option the majority of our interlocutors used. And all this would make us all very aware how delicate the data we gather are and how difficult it is to manage data while writing and researching. In our discipline we are very aware that sometimes the narratives can be a reflection of a desired version of reality (order imagined). A good example of this kind of situation would be a question about the dowry (in Vodnjan, for example): The answer would usually be what ideally would dowry consist of. However, when I asked about the dowry my interlocutor was bringing in the new home, then the answer was quite often that they did not have anything, because it was immediately after the war (WWII) or similar. The lists of dowry textiles given in the first answer was usually the ideal dowry, that was given, if the family was rich enough, in some cases. And the researchers have to be aware about this difference between ideal and achieved reality being recollected during the interviews. The same relates to questions about, e.g. premarital sexual relations. One of my first interviews, carried out for the purpose of the university seminar included this question, and only after the interview ended, I was able to hear (not record!) the unofficial truth (or at least a version of it). And I interviewed the family member, so there was a field of trust between actors in the research. I am not sure if I would, as a student, gather this information with someone I barely knew. On the other hand, sometimes revealing the very private information to total stranger in the community seems to be the option for some interlocutors. Only at the end of the interview would the interlocutor ask me not to use this particular data, or maybe even ask me to erase this part of the tape (something my technical skills did not allow me to perform immediately).

Only when I started my first application for CSF funding, and after finally being successful, the research project had to pass our institutional Ethic board. I work at the four- field anthropological institute and majority of my colleagues at the Institute are from the field of biological or archeological anthropology. Working with human material (blood or bones) required basic form to be quite elaborated, similar to the international requirements that my colleagues were quite familiar with. The form was extended to the cultural anthropology issues and resulted, in the case of the research project "Solidarity economy in Croatia: anthropological perspective (SOLIDARan) with a quite elaborated form (Appendix C). The informed consent was quite detailed and long, but it covered all the important ethical concerns.

I followed Ethical principle of CES, and other relevant sources. Here as well I clearly stated how the data will be used.

"Your personal information gathered for this study interview will only be utilized for scientific research. All project colleagues may utilize the information from your interview (in the form of quotes or single comments) for disseminating research findings in books, scientific publications, or conference presentations on posters or presentations. Your name and last name won’t be mentioned anywhere if you choose to stay anonymous, and your privacy is assured. In that scenario, you will be able to select a pseudonym from the database, or catalogue, of Croatian personal names. If you would like, the audio recording of the discussion and/or the interview transcript can be sent to your home address via email

The audio recording of the research conversation will be stored in the main researcher’s computer and in the Audio Materials Database of the Institute for Anthropological Research. The transcripts of the interview will be printed and filed under the project number in the Institute for Anthropological Research’s Database of Qualitative Research. Furthermore, the research interview transcripts will only be accessible to researchers involved in the project as collaborators, with the intention of undertaking scientific analyses."(SOLIDARan project Informed consent form, Form 3, Appendix C).

The informed consent process and the information it provided went as follows: each interlocutors took a personal copy so they could later review the documents they had signed, but I still had to explain everything orally because most of them did not want to take the time to read it. They made decisions on their anonymity and how they wanted (or did not want) the information to be sent to them.

A standard procedure in conducting an in-depth interview (as the most common qualitative methodological tool for anthropology (today mostly anthropology by appointment (Hannerz 2006) is providing enough information for the interlocutor in order to sign an informed consent. Apart from describing the research the informed consent sheet has to contain the data explaining the procedure of keeping and managing the data, as well as mentioning media in which the data will be presented (articles, exhibitions, documentary etc.). Anonymity is always one of the possibilities informed consent offers, and majority of interlocutors opt for it, but not all. Occasionally, the interlocutor insists on periodical switching off the recorder by researcher, usually when something delicate is being recollected. Interlocutors are aware that voice can be recognized and try to make sure that this does not happen. Also, quite often, after the interview ends, the researcher can hear the information that was not meant to be recorded. Although there are ways to anonymize the data (as explained in Celjak et al19) interlocutors coming from smaller communities or groups can be recognized from the parts of the transcript that have not been removed (in order to secure anonymity) or by voice.

Once informed consent is “obtained”, researchers ordinarily gain exclusive rights over how the discourse circulates and is interpreted, who receives it, and who benefits. Interviews thus impose standardized social scientific knowledge-production and -circulation practices that further subordinate and obscure the knowledge-making practices that interviewees use in making social worlds and challenging forms of symbolic and other violence20.

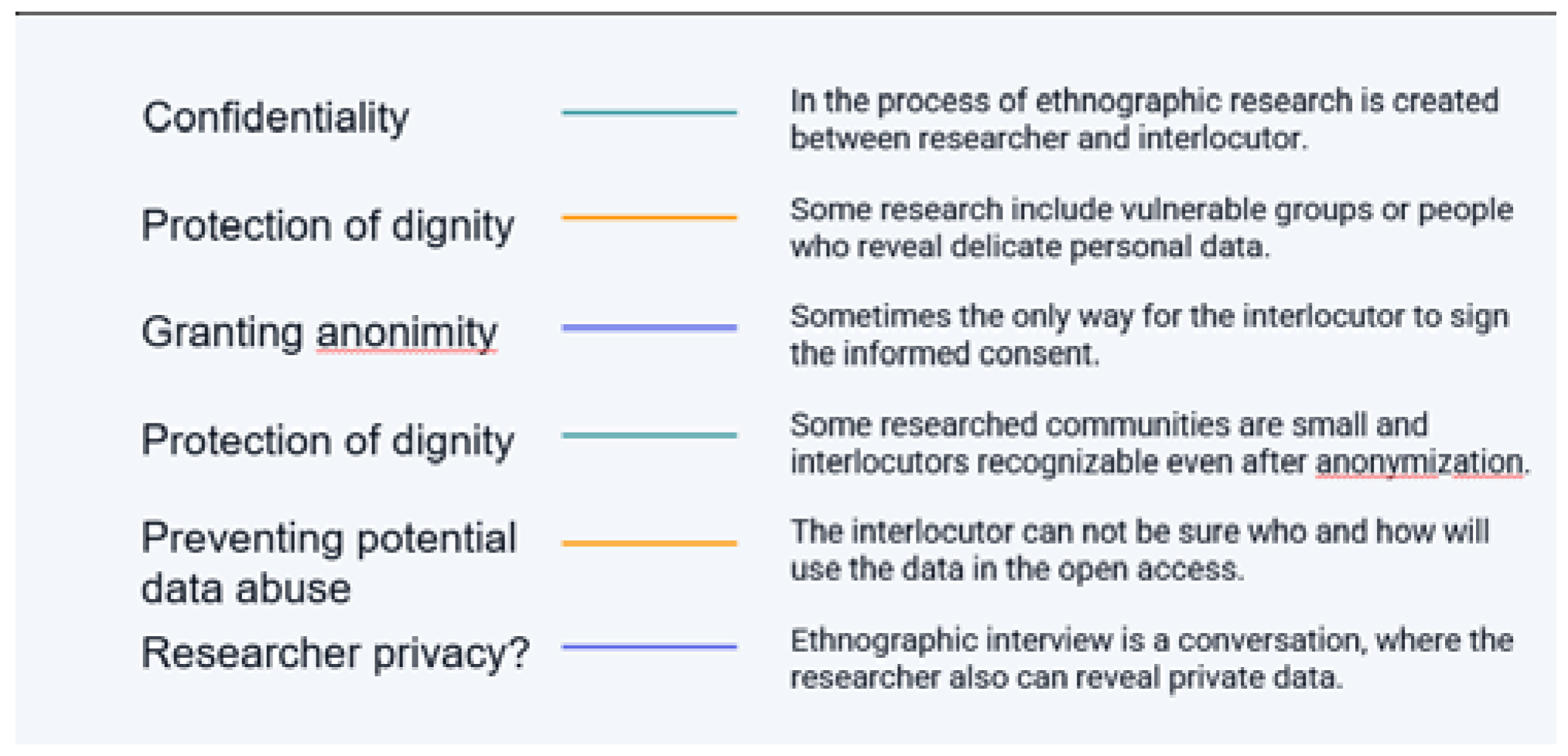

The confidentiality created in this complex process of the research via interviewing is not unproblematic or without risks. Therefore, a researcher has to try to make it as FAIR as possible, and the guiding principle is "do not harm" i.e. CARE principles.

The protection of dignity seems to be a natural and normal request for any research, but is especially important during research that include vulnerable and marginalized groups.

Granting anonymity seems to be a perfect solution, because in this way, the data would be, after a complex process of anonymization of everything that could be recognizable when data would be FAIR,

However, some researched communities are small, especially when we speak about communities of practice (e.g. members in charge of organizing carnival, or similar), and therefor

The informed consent interlocutors signed so far (according to CES ethical codex, and the informed consent created for SOLIDARan project (and other as well) clearly states that the researcher and research groups will have the exclusive writes in using this data.

And at the end, maybe not that important, but still – what about researcher privacy? It is common practice to engage in conversation with interlocutor, not simply to ask questions and in this conversation, one might reveal some private data.

Figure 1.

Some potential problems with making all qualitative data available (Orlić, PUBMET 2023 ppt, slide) 9).

Figure 1.

Some potential problems with making all qualitative data available (Orlić, PUBMET 2023 ppt, slide) 9).

All these issues raise question – should really the ideal goal for all the data to be only FAIR? The answers received with the questionnaire reveal that sharing data among Croatian Ethnologist means sharing data within the team or project members and storing it in the institutional documentation. Majority of the respondents express the need to "do no harm" to the community researched. They also stress the thematic-dependent decision about sharing the data, and the need to protect sensitive and personal data. Some of them stress the fact that anonymization does not work in small communities. Also, the majority stress the fact that the interlocutors should be in charge of deciding to what extent data they provided, should be, if at all, shared. Some ethnologist and anthropologist stated that data obtained by qualitative methodology and ethnography are not the kind of data one can compare and re-use, that this kind of data can be simplified or incorrectly interpreted without knowing the rich context of the research encounter. Some of them go even that far that they envisage the production of digital waste that will in the end not be that useful. However, there are researchers who think that these data should be made available in the same manner the archival data and that if the researcher will not use the data, then it is better to publish them.