1. Introduction

Speeding (excessive or inappropriate speed) is an important road safety risk factor responsible for a majority of fatal and serious injury crashes world-wide. Meanwhile, the effects of speeding on crash outcome are disproportionate between Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and High-income countries (HICs). Recent analysis show that speeding accounts for about 54% of fatalities worldwide with a probability of 95% that these occur on LMIC roads [

1].

Understanding the factors which affect the speeding behaviour is critical for developing effective preventive measures to mitigate speeding. Research show that there is a significant cultural difference in speeding behaviour between HICs and LMICs [

2,

3,

4,

5] but also amongst LMICs [

6,

7]. These findings suggest the need to investigate the local situation, which will contribute to the development of local-specific solutions. This is especially important within LMICs where there are significant research gaps.

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) postulated by Ajzen (1985, 1991) has often been used by several researchers to study the speeding behaviour of drivers [

6,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] . The TPB studies factors that affect a behaviour (e.g. speeding). These factors include attitude (ATT), subjective norm (SN), perceived behavioural control(PBC) and intentions. According to the theory, ATT, SN and PBC have an influence on the behavioural intention while the behavioural intention, but also PBC have an influence on the behaviour [

13].

In terms of definition, Attitude is referred to the overall positive or negative assessment of a specific behaviour, subjective norms represent the perceived social pressure from others or social groups to behave in a particular way and perceived behavioural control refers to the perception of the ease or difficulty of performing a particular behaviour [

13,

14].

However, despite the wide applicability of the TPB in safety behaviour, some researchers believe that the attitude–behaviour relation in the theory may not have strong applicability in a low-income country context [

15]. This necessitates further research.

Beyond the factors listed in the TPB, several other factors are usually attributed to determine the speeding behaviour. An earlier research work based on an exploratory review summarised these factors in to four categories [

16]:

Person-related factors: Speed choice is affected by individual characteristics such as crash history, gender, age, attitudes, values, and predisposition to sensation seeking.

Social factors: Speed choice is affected by the influence of others such as peer/passenger pressure, media, exposure to role models, behaviours and travelling speeds of others. Factors such as perceived risk, and vehicle operating costs, can be supplemented to this list.

Situational factors: These include factors such as emergency, running late, the purpose of the trip, keeping up with the traffic flow and the opportunity to speed.

Legal factors: Speed choice is affected by the presence of enforcement initiatives (such as speed cameras and police enforcement) and punishment.

Based on this, some researchers have extended the TBP for speeding to include factors such as past behaviour, driving habits, legal sanctions, and personal traits. These factors have proven significant mediating effects on the speeding behaviour, though the size of the effect differ between studies [

8,

10,

14,

17]. Hence, the investigation of these factors on speed behaviour is important.

In Cameroon, speeding is widely recognized as a significant issue impacting road safety, primarily due to the high legal speed limits of 60km/h in urban areas and 110km/h in rural areas [

18]. Considering the well-established and positive correlation between speed and road accidents [

19], it is believed that these elevated speeds are responsible for a majority of the crashes and fatalities occurring in Cameroon. However, there is a lack of comprehensive research on this specific topic within the context of Cameroon, which hampers efforts to identify interventions for mitigating speeding. An exploratory review of the available literature reveals a notable absence of studies examining the factors influencing speeding behavior in Cameroon. This is a common challenge faced by many other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, where research in this domain is scarce.

Existing research conducted through the ESRA survey, which involved a sample of 200 respondents in Cameroon between 2019 and 2020, focused on self-reported driving behavior[

20]. The findings indicate that approximately 40% of drivers reported speeding in built-up areas, while 44% and 47% reported speeding on motorways and outside built-up areas, respectively. These self-reported statistics provide an estimation of the prevalence of speeding in Cameroon. However, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations of the ESRA survey, such as the relatively small sample size, exclusive focus on cars, and the absence of an in-depth evaluation of the factors influencing speeding and the extent of speeding violations. Moreover, the literature highlights that some drivers in LMICs may be unaware of the speed limits [

15], which implies that asking drivers about their speed above the limit could yield biased results in cases where drivers lack awareness of the specific speed limits. This was the case for the ESRA survey.

This research aims to close the observed gaps through the following objectives:

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Proceedure

The study employed an online questionnaire to investigate the stated objectives. The questionnaires were developed and subsequently distributed through various social network channels, with responses collected randomly from anonymous drivers. Prior to the online distribution of the questionnaire, a pilot study was conducted to ensure clarity, and any necessary corrections were implemented. The questionnaire was formulated in both national languages, English and French. The online survey period spanned two months, specifically October and November of 2023.

2.2. Participants

The target population for this study comprised drivers in Yaoundé, the capital city of Cameroon. The selection of this target population to investigate drivers' speeding behaviors was based on several reasons. These include the city's connection to multiple regions within the country, the presence of diverse vehicle types, the high variability of driver behaviors (from local knowledge, mixed of compliant drivers and non-compliant drivers), and the density of traffic, which offers a wide range of driving situations representative of the challenges encountered in numerous urban areas and highways throughout the country.

A total of 387 responses were received from drivers of cars, motorcycles, tricycles, trucks, and buses. This sample consisted of 68% males and 32% females.

2.3. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire was designed to measure variables based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), but also considering other factors that influence speeding behavior and other areas of interest. The formulation of specific questions was guided by prior research on the topic. The questionnaire consisted of two primary categories of questions: socio-demographic information and questions pertaining to speed behavior within the context of the theory of planned behavior. The arrangement of these questions was as follows:

2.3.1. Socio-Demographic Information

Socio-demographic data focused on questions such as gender, age group, education level, marital status, driving license type, vehicle type, and number of years of experience.

2.3.2. Speeding Intention (SI)

Speeding intention was assessed through four items classified into two categories. Category one (items i to ii) aimed to measure the intention to adopt speed management technologies, while category two (items ii to iii) directly focused on speeding intention for the TPB application: The items included (i) SI1: I am willing to use speed management technologies (e.g., speed limiters, speed warnings) to help me comply with speed limits. (Agree/Disagree) (ii) SI2: Are you ready to adopt the following speed management technologies? Participants could select multiple responses from: "Automatic speed limiters installed in vehicles," "Speed alerts that alert you when you're over the speed limit," "Intelligent speed enforcement systems on the roads," "Speed Surveillance Cameras for Sanctions Enforcement." (iii) SI3: On a scale of 1 to 5, how tempted are you to speed? (Always/Never) (iv) SI4: How often are you tempted to exceed the speed limit in urban areas? (Never, Occasionally, Sometimes, Often, Always). Only category two questions were used to assess speeding behavior to test the TPB (Cronbach's alpha for category two questions was 0.625).

2.3.3. Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC)

Perceived behavior was measured on two items: (i) PBC: In the case of breaking the speed limit, to what extent do you perceive the risk of being stopped by the police? (Extremely High, High, Medium, Low, Very Low) (ii) How do you rate your driving skill compared to other drivers? (Much Better, Better, Same, Worse, Much Worse). These two items were considered separately due to a negative Cronbach's alpha. Item one was used to investigate the TPB.

2.3.4. Self-Reported Speeding (SB)

Self-reported speeding, considered as the speeding behavior, was measured through 6 items divided into two categories. Category 1 had five items that were categorized for the TPB to represent the speeding behavior. Category 2 had 1 question to measure knowledge of speed limits. Category 1 questions included: (i) SB1: By how much do you often exceed the speed limits in urban areas? (Never, 5km/h, 10km/h, 15-20km/h, More) (ii) SB2: By how much do you often exceed the speed limits on highways? (Never, 5km/h, 10km/h, 15-20km/h, More) (iii) SB3: In general, what is your preferred speed when driving on highways? (60km/h, 70km/h, 80km/h, 100km/h, over 100km/h) (iv) SB4: In general, what is your preferred speed when driving in urban areas? (Under 50km/h, 50km/h, 60km/h, over 60km/h) (v) SB5: How often have you exceeded the speed limit on highways like Douala-Yaoundé? (Never, Occasionally, Sometimes, Often, Always) Category 2 question was: (vi) SB6: Are you aware of the speed limits in urban areas and highways in Cameroon? (Yes/No). The Cronbach's alpha for category 1 questions was 0.86.

2.3.5. Subjective Norm (SN)

The subjective norm was assessed through 5 items: (i) SN1: I think speeding is socially unacceptable. (Yes/No) (ii) SN2: Speeding is dangerous for me and other road users. (Totally Agree, Agree, Disagree, Totally Disagree). (iii) SN3: To what extent do you think people who are important to you would approve/disapprove if you break the speed limit? (Approve, Disapprove, Indifferent). (iv) SN4: In your opinion, what do pedestrians and users of soft mobility (bicycles, scooters, unicycles, etc.) think about speeding drivers? (Approve, Disapprove, Indifferent). (v) SN5: What is your opinion about speeding in areas such as residential streets, around schools, or hospitals? (Approve, Disapprove, Indifferent). The Cronbach's alpha was negative for all the questions combined. After observing the signs and magnitude of dimension reduction factors through factor analysis, items (i), (ii), and (v) were retained as they belong to the same factor with higher factor loadings (>0.5).

2.3.6. Attitude towards Speeding Behavior (AT):

Attitude towards speeding behavior was assessed through four items: (i) AT1: In your opinion, how often do you engage in speeding during your driving sessions? (Never, Occasionally, Sometimes, Often, Always). (ii) AT2: I feel responsible for respecting the speed limits. (Yes/No) (iii) AT3: What are the reasons that could lead you to speeding while driving? Participants could select multiple responses from options such as time pressure (e.g., being late), feeling powerful or excited, traffic rules, driving experience. (iv) AT 4: What are the reasons that could lead you to speeding while driving? Participants could select multiple responses from options such as "Experienced drivers can safely drive at speeds above the legal limit," "The police don't often punish speeding," "The speed limits are set too low," "Speeding is acceptable on certain roads or in certain situations”. The value of Cronbach's alpha was very low for the attitude questions. However, after conducting dimension reduction (factor analysis), one factor explained all of these variables with factor loadings greater than 0.4.

2.3.7. Perceived Risk:

The perceived risk was assessed through one question: Do you think that complying with a speed limit would decrease the risk of accidents? (Totally Agree, Agree, No Idea, Disagree, Totally Disagree).

2.4. Data Analysis

The analysis included descriptive statistics, Chi square test, Pearson correlation analysis, factor analysis, Hierarchical regression analysis, Structural equation modeling, and other post-hoc analyses. Separate analyses were conducted using Excel, R software version 4.3.1, and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.

Descriptive statistics was carried out for the demographics and driver related data. Chi-square tests for independence were conducted examine the relationships between the demographics and the speeding behavior (level of compliance).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and Principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out to investigate the relationship between the observed variables (e.g., AT1 to AT4), which described the latent variables (e.g., AT). The resulting factors and factor loadings were used to identify, and screen observed variables that had a significant relationship with the latent variable. This process was also guided by reliability testing using Cronbach's alpha to assess the consistency of the observed variables for each latent variable (also called construct). The factors (in all cases one factor) derived from carrying out the dimension reduction (PCA) was used to develop composite indicators from the observed variables to form the latent variables. These composite indicators were created for AT, SN, SI, and SB, which were later used in regression analysis and the structural equation modeling.

Hierarchical linear regression analysis was conducted to predict both speeding intention and speed behavior. Demographic characteristics were entered as the first set of predictors, followed by the composite variables of the TPB as the second set of predictors. This analysis aimed to understand the change in variability of SI and SB after the addition of the TPB variables.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to study the relationships between observed and latent variables, as well as the mediating effect with the independent variable (speeding behavior). SEM allows for the analysis of causal relationships among variables using simultaneous equations. It integrates both direct and indirect measures of variables, considers measurement errors, and enables estimation of model parameters, evaluation of data fit, and testing of specific hypotheses. Two SEM models were developed with to investigate the best model fit for the TPB:

SEM 1: The structural model is built using the composite variables of the TPB and the perceived risk variable. SI is modeled as a function of AT, PR, PB, and SN, while SB is modeled as a function of PB and SI.

SEM 2: The structural model is similar to SEM 1 but includes demographic characteristics as predictors of SI.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of Demographic Information and Driver -Related Characteristics

Table 1 presents demographic information and descriptive statistics for driver-related variables. In terms of gender, 68% of the sample (263 individuals) are male, while females represent 32% (124 individuals). The age distribution is as follows: 11.1% (43 individuals) are between 18 and 25 years old, 27.9% (108 individuals) fall within the 26-35 age range, 30.7% (119 individuals) are in the 36-45 age group, 23.8% (92 individuals) are in the 46-55 age group, and 6.5% (25 individuals) are 56 years old or older. In terms of vehicle ownership, 54.3% (210 individuals) own a car, 17.1% (66 individuals) own a motorcycle, 2.3% (9 individuals) own a tricycle, 10.1% (39 individuals) own a truck, 16.3% (63 individuals) own a bus or minibus, and 2.3% (9 individuals) own a type A vehicle. Regarding driving experience, 8.3% (32 individuals) have less than one year of experience, 41.1% (159 individuals) have 1 to 5 years of experience, 40.6% (157 individuals) have 6 to 10 years of experience, and 10.1% (39 individuals) have over 10 years of experience.

3.2. Self-Reported Speed Limit Non-Compliance and Knowledge of Speed Limit

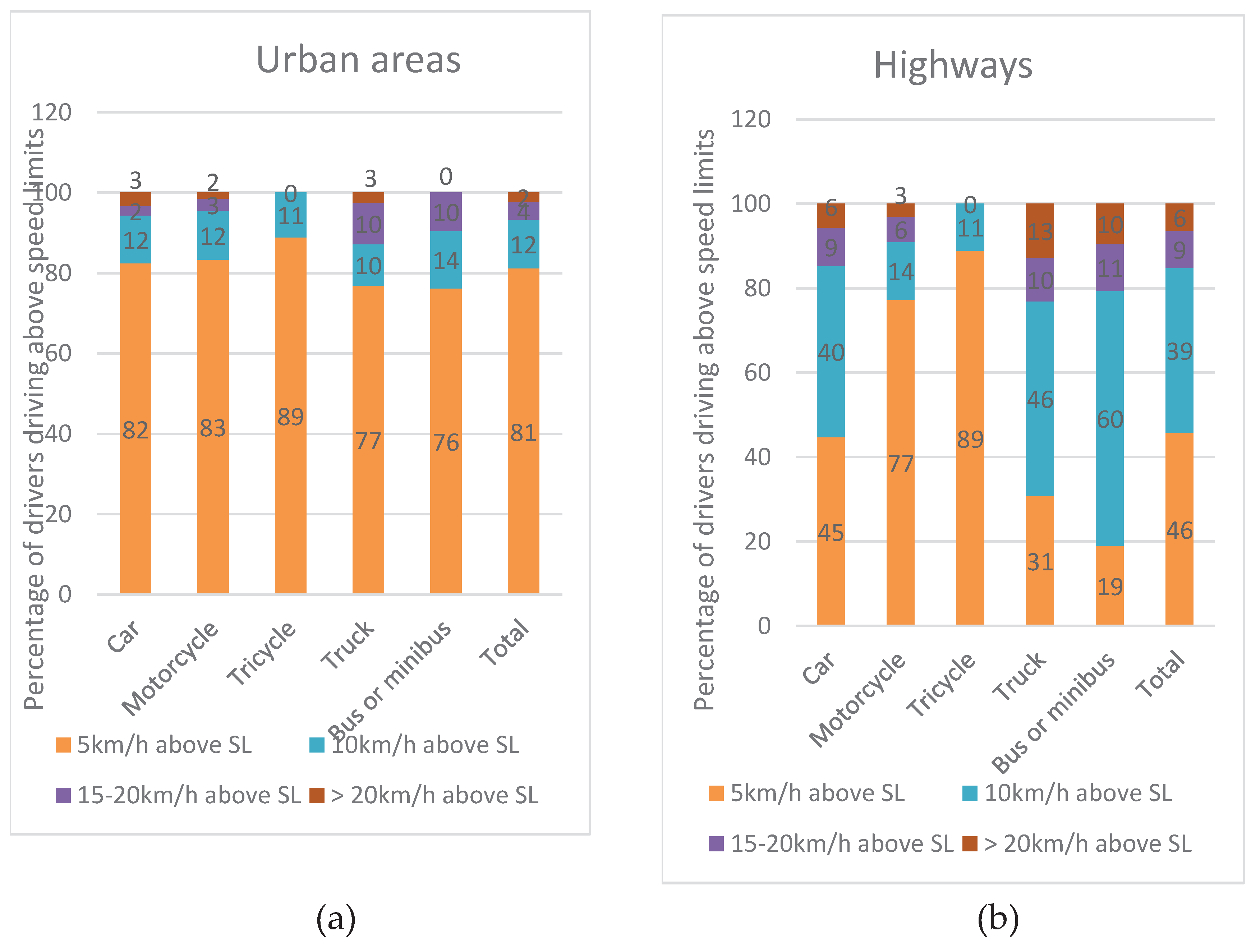

Figure 1 presents results on drivers' self-reported speed limit non-compliance in urban areas and highways categorised by vehicle type. The results indicate that in urban areas, 81% of drivers exceeded speed limits by 5km/h, 12% exceeded by 10km/h, 4% exceeded by 15 to 20km/h, and 2% exceeded by more than 20km/h. In highways, as expected, the percentage of drivers exceeding the speed limit by more than 10km/h (54%) increased significantly, particularly among bus or minibus drivers. It is worth noting that none of the drivers reported driving within the speed limits in either urban areas or highways.

Regarding participants' knowledge of speed limits, 89% of the total sample claimed to know the speed limits. This knowledge was highest among bus/mini-bus and car drivers, with 98% and 91% respectively. However, 56% of tricycle drivers and 26% of motorcycle drivers reported not knowing the speed limits. It is important to note that the sample size for tricycle drivers was relatively small. After excluding drivers with no knowledge of speed limits from the analysis, the overall trend of non-compliance remained largely unchanged, consistent with

Figure 1.

These findings have significant implications for targeted road safety interventions, highlighting the need for addressing non-compliance with speed limits. However, given the limited sample size of tricycle drivers, caution should be exercised when generalizing the results to this specific group.

3.3. Association between Age, Gender, Driver License and Speed Limit Non-Compliance

The chi-square test of independence was employed to examine the relationship between demographics and self-reported speeding. The results of this analysis are presented in

Table 2. The P-value indicates the significance of the association, while Cramer's V reflects the strength of the association. Cramer's V values up to 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 indicate small, medium, and large effects respectively (Cohen, 1992 cited in[

21]) .

The findings reveal a statistically significant association between age and speed limit non-compliance in both urban areas (= 28.8, P<0.05, V = 0.16) and highways (= 41.4, P<0.001, V = 0.19). The highest cumulative percentage of drivers exceeding speed limits (>10km/h) in urban areas was observed among the [18;25] age group, whereas in highways, the highest percentage was observed among those aged 56 or older.

Regarding license type, there is no significant association with speed limit non-compliance in urban areas (at P<0.05). However, a significant relationship is observed in highways (= 41.3, P<0.001, V = 0.19), with drivers holding a type C license exhibiting higher non-compliance (for speeds >10km/h above speed limits).

In terms of gender, a statistically significant association is found in urban areas (= 8, P<0.005, V = 0.14), with males reporting higher speeds than females (for speeds >10km/h above speed limits). However, no significant association is observed in highways.

Despite the high incidence of speed non-compliance, 95.9% of drivers expressed willingness to use speed management technologies to assist them in complying with speed limits. The majority of drivers favoured the adoption of automatic speed limiters installed in vehicles and speed surveillance cameras as means to ensure compliance with speed limits.

3.4. Factor Analysis and Reliability Statistics

Table 3 displays the results of the factor analysis and reliability test. Initially, a factor analysis was conducted on all observed variables (all the questions). Variables with lower factor loadings and those that decreased the reliability within the group were identified and removed. The results presented in

Table 3 represent the second step, where factor analysis was performed again on the observed variables selected in the first step. In all cases, a single component was obtained, and the factor loadings of the observed variables were greater than 0.4, which is deemed acceptable [

22] . These factors, also referred to as components, were used to construct composite latent variables for speeding intention (SI), speeding behavior (SB), subjective norm (SN), and attitude (AT).

3.5. Correlation Analysis

Before conducting the hierarchical regression analysis and structural equation model, a Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationships between sociodemographic variables (gender, age, education level, marital status, driver's license, driver's experience, vehicle type) and the composite variables (AT, SI, SB, SN), including the non-composite variables PR and PBC. The results of the correlation analysis are presented in

Table 4.

The correlation analysis provides insights into the associations between the variables of interest. Significant correlations were found between most of the variables and speeding intention (SI) and speed behavior (SB). The strongest correlation for SB was observed with perceived behavioral control (PBC), indicating that individuals' belief in their ability to control their speeding behavior is strongly related to their actual behavior. For speeding intention, the strongest correlation was found with attitude (AT), suggesting that individuals' attitudes towards speeding influence their intention to engage in speeding behavior. Additionally, education level exhibited a positive and significant relationship with most of the variables, indicating that higher levels of education are associated with certain attitudes, intentions, and behaviors related to speeding.

3.6. Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis

The objective of the Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was to elucidate the factors influencing the intention of speeding and the speeding behaviour by incorporating several independent variables at different steps. The analysis was conducted in two steps. In the first step (STEP1), the effects of various demographic and driver related independent variables were examined, including sex, age, education level, marital status, driver's license, vehicle type, and driver experience. In the second step (STEP2), other independent variables were added which included the factors of the TPB (AT, SN, PBC and PR). The results for speeding intention and speeding behaviour are presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6 respectively. No multicollinearity issues were observed for the speeding intention and speed behaviour models as the VIF of all predictors fell between 1 and 3.

According to the results of

Table 4, at Step 1, the overall model accounted for 18% of the variance in the intention of speeding with sex, education level and driver experience demonstrating a significant relationship with speeding intention ( at p < 0.05). At Step 2, after addition of the variables of TBP, the model variance increases to 32.1%, representing an increase of about 57 %. In addition to sex, education level and driver experience, attitude, and perceived risk show significant relationship with speeding intention. All significant variables except for sex showed a positive relationship with speeding intention. This indicates that either gender (in this case males) is more inclined to have the intention of speeding. These findings provide valuable insights into individuals' propensity to engage in speeding behaviour. However, it should be noted that the generalizability of these results to other populations or contexts may vary.

Regarding speeding behavior, the initial step (Step 1) of the analysis accounted for 15.9% of the variance, revealing significant relationships between speeding behavior and sex, age, education level, and marital status. In the subsequent step (Step 2), after incorporating additional variables related to Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), the variance increased to 31.4%. This represents a proportionate increase of more than 50%. Notably, education level, marital status, attitude, perceived behavioral control, perceived risk, and speeding intention emerged as significant factors at this stage. It is important to mention that certain variables, such as sex and age, which were significant in Step 1, lost significance in Step 2. This could be due to issues of the masking effect of other variables.

Comparing the models for speeding behavior and speeding intention, the signs of the variables that were significant in both models remained consistent, indicating a mediating relationship between speeding intention and speeding behavior.

3.7. Structural Equation Models

3.7.1. SEM1

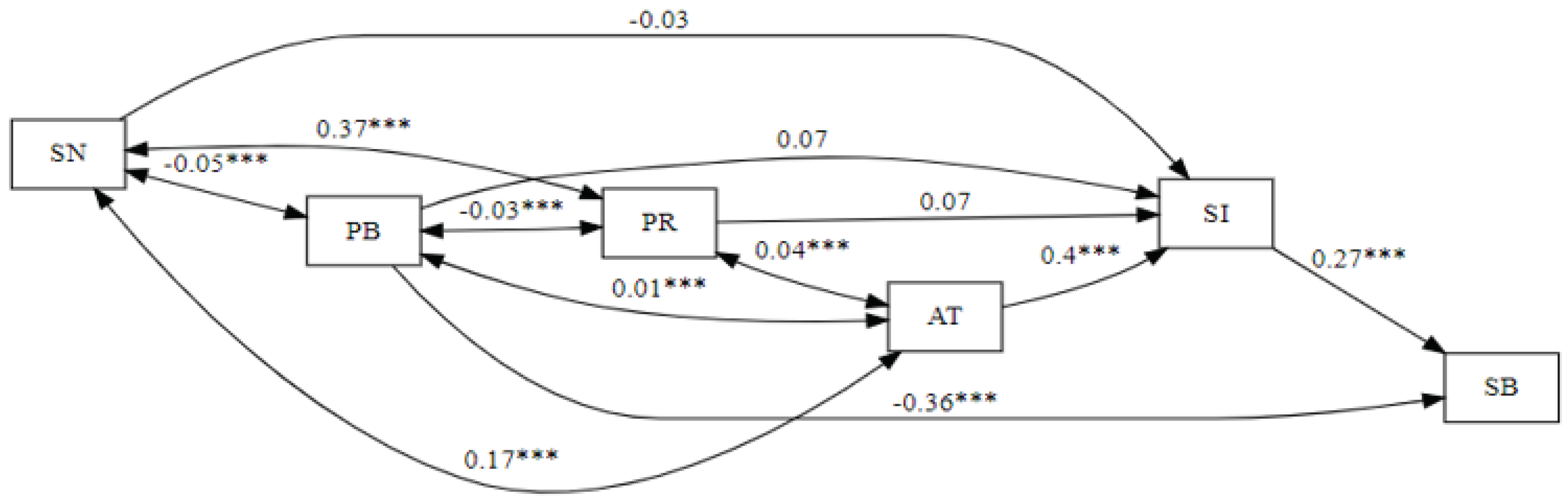

SEM 1 results (shown in

Figure 2) validated the TPB framework. The structural equation depicted the direct and indirect effects of various factors on speeding behavior (SB), including the mediating effect of speeding intention (SI). The goodness-of-fit analysis indicated that the model generally fell within acceptable levels based on inference from past studies[

9], [

11], [

23]. The Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI) were estimated at 0.892 and 0.675, respectively, which were close to the acceptable threshold of 0.9. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.006, indicating a good fit, while the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.045, below the threshold of 0.08. However, the p-value of the chi-square test showed some significance, suggesting a poor fit. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the chi-square test is sensitive to large sample sizes and can yield significant p-values regardless of the model fit.

According to the SEM 1 results, attitude (AT) towards speeding behavior was the only variable with a significant relationship with speeding intention (SI) (beta = 0.4, p < 0.001). This positive relationship indicates that drivers who feel confident in their driving experience, perceive a sense of power, or experience time pressure are more likely to have positive intentions regarding speeding. The coefficient of determination for the speeding intention variable was 0.17. The standard path coefficients revealed that subjective norm (SN) (beta = 0.17, p < 0.001), perceived behavioral control (PB) (beta = 0.01, p < 0.001), and perceived risk (PR) (beta = 0.01, p < 0.001) demonstrated significant relationships with attitude, which in turn acted as a mediator for speeding intention.

Regarding speeding behavior, the coefficient of determination was 0.187. Consistent with the TPB, speeding intention (beta = 0.27, p < 0.001) and perceived behavioral control (beta = -0.37, p < 0.001) exhibited significant relationships. The negative relationship observed for perceived behavioral control (PB) is not uncommon and indicates that drivers who perceive lower control (such as feeling less likely to be apprehended by the police or facing difficulties adhering to speed limits) are more inclined to exceed speed limits. The positive relationship for speeding intention (SI) suggests that drivers with a high intention to speed are more likely to engage in speeding behavior.

3.7.2. SEM2

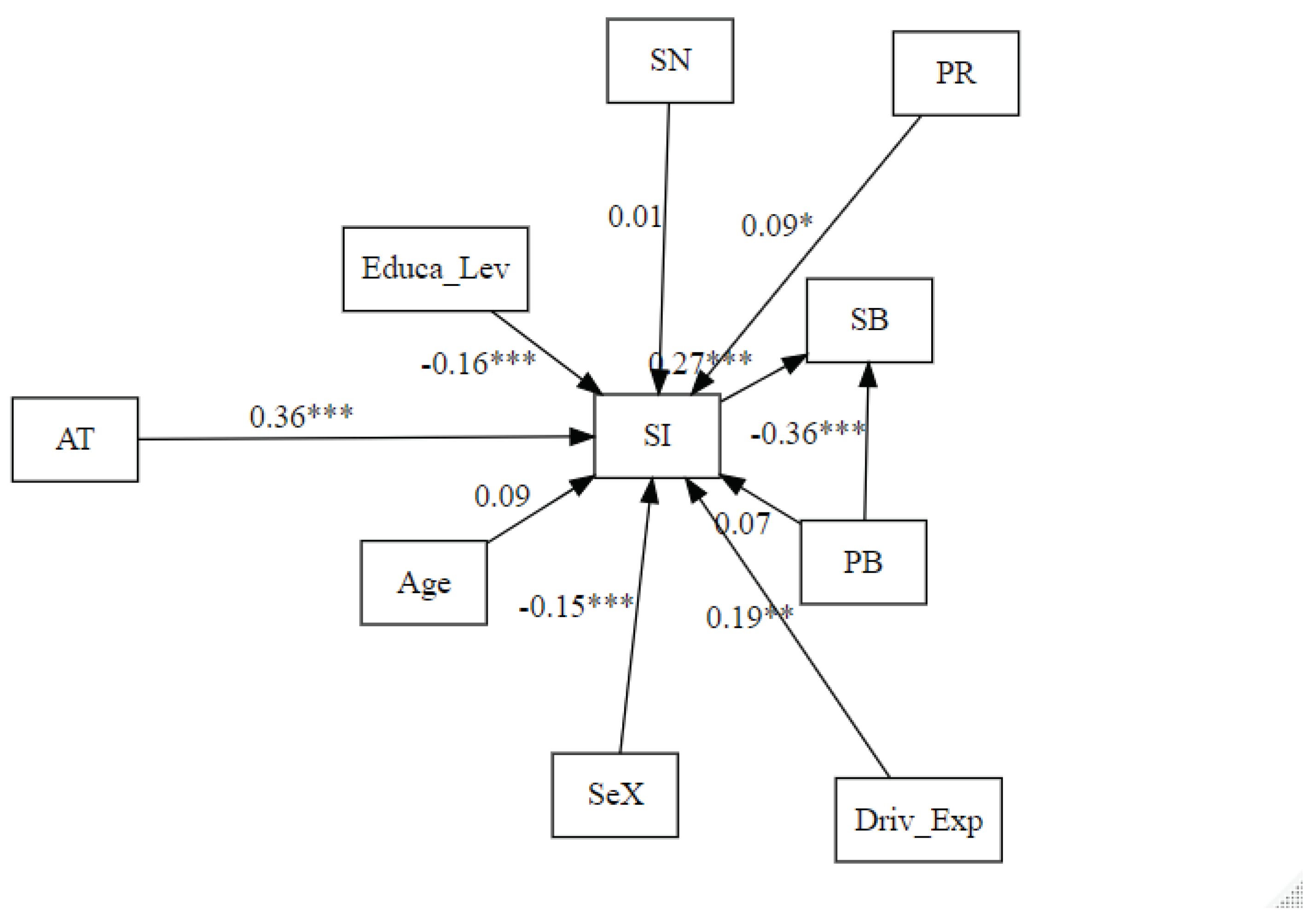

The SEM 2 results (

Figure 3) depict the relationship between demographic and driver characteristics in explaining the variance in speeding intention (SI). The evaluation of model parameters, including TLI, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR, indicated a fair fit, with some variables meeting acceptable limits while others did not. The interaction between variables was allowed but not shown in the diagram for readability. The results revealed that education level (beta = -0.16, p < 0.001), sex (beta = -0.15, p < 0.001), driver experience (beta = 0.19, p < 0.001), perceived risk (beta = 0.09, p < 0.05), and attitude (beta = 0.36, p < 0.001) demonstrated significant relationships with speeding intention, reflecting strong indirect effects on speeding behavior. These variables explained 32% of the variance in speeding intention.

The observed negative structural relationship between level of education and intention to engage in speeding means that as the level of education increases, the intention to engage in speeding decreases. This can be translated into effects such as increased risk awareness. Individuals with higher levels of education are often associated with higher levels of cognitive skills and critical thinking, and they may be more informed about the dangers and negative consequences associated with speeding. The negative relationship between gender and speeding intention means that there is a tendency for women, who are in the minority in this study, to have a reduced intention to engage in speeding. The observed positive structural relationship between driving experience and the speeding intention indicates that there is a tendency for greater driving experience to be associated with an increased intention to engage in speeding. This means that the more driving experience a person has, the more likely they are to express an intention to drive at high speeds as they become overconfident in their skills. Additionally, greater familiarity with roads and driving conditions can also influence the intention to drive at high speeds

Similar to the SEM 1 results, in SEM 2, speeding intention (beta = 0.27, p < 0.001) and perceived behavioral control (beta = -0.36, p < 0.001) exhibited significant relationships with speeding behavior. Speeding intention and perceived behavioral control accounted for 19% of the variance associated with speeding behavior (SB).

4. Discussion

The results of this study reveal several significant findings regarding speeding behavior in a lower-middle-income country like Cameroon. The first part of the study examined self-reported speeding non-compliance and its association with demographic and driver characteristics. The second part focused on analyzing the factors influencing speeding behavior based on the theory of planned behavior.

The findings regarding speeding non-compliance shed light on the extent of speeding in urban areas and highways in Cameroon. It was found that 100% of drivers reported exceeding the speed limits by at least 5km/h, and this rate increased further in high-speed environments such as highways. These reported non-compliance rates are higher than those observed in the 2019/2020 survey for Cameroon [

20]. These results are highly concerning, considering the strong correlation between speed and accidents. Studies have shown that a 1km/h increase in speed is expected to raise fatalities and serious injuries by 8% and 6% respectively [

24]. The impact is likely to be even greater due to the high presence of vulnerable road users, especially in the capital city, Yaoundé, where data was collected from study participants. This high level of speeding non-compliance may be contributing to the high number of vulnerable road user fatalities in the country. Therefore, there is an urgent need for speed management measures in both urban areas and highways to reduce speed levels. Encouragingly, a significant majority of drivers expressed their willingness to adopt speed management technologies, such as speed limiters and speed surveillance systems, to help them comply with speed limits.

Additionally, evidence emerged that up to 11% of drivers were not aware of the speed limits, which is not uncommon in lower-middle-income countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where traffic regulations and speed limits are often poorly defined [

15]. Furthermore, the study revealed a statistically significant association between age, gender, driver's license status, and speed limit non-compliance, with the effects varying according to the road type. These findings align with previous research conducted in other lower-middle-income countries [

25,

26], as well as in higher-income countries [

21,

27]. The results indicated higher levels of speeding among young drivers in urban areas, whereas in highways, older drivers were found to have higher levels of speeding. This suggests that a larger proportion of drivers on highways are older, more experienced drivers who tend to exceed speed limits due to their familiarity with such roads. This was further supported by the fact that the percentage of speeders was significantly higher for buses/mini-buses on highways, which are typically driven by older drivers. These findings also align with previous research indicating that older drivers are more likely to speed outside built-up areas [

28]. Furthermore, the results showed that males were more likely to report high non-compliance than females, which is a common finding [

21,

28]. However, this significant association was observed only in urban areas and not on highways.

Regarding the factors influencing speeding behaviour under the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), several important findings emerged from the regression analysis and structural equation models. The results of the regression analysis demonstrated that, after controlling for demographic and driver-related characteristics in the first step, the addition of TPB variables accounted for over 50% of the variance in both speeding intention and speed behaviour. This indicates a strong relationship between TPB variables and supports the theory, consistent with findings reported in other research [

29].

A significant and robust relationship was observed between speeding behaviour and both speeding intention and perceived behavioural control, which aligns with previous studies [

10,

11,

29,

30].These results suggest that modifying drivers' speeding intentions and their perception of control over speeding can have a substantial impact on their actual speeding behaviour. However, it is important to acknowledge the negative relationship between speeding behaviour and perceived behavioural control, which is in line with the findings of other authors [

11].

Speeding intention, in turn, played a mediating role in influencing speeding behaviour. The determinants of speeding intention were primarily attitude, but also perceived risk, and other demographic and driver-related characteristics such as education level, gender, and driver experience. Attitude emerged as the most significant variable influencing speeding intention, with a positive association as observed by other authors [

10,

29,

31].The findings regarding the effects of demographic and driver characteristics on speeding intention are also consistent with previous research [

10,

29]. Subjective norm, however, did not show a statistically significant relationship with speeding intention. Notably, new evidence that emerged from this research highlighted the determinants of speeding attitude, revealing a significant relationship between attitude and social norm, perceived risk, and perceived behavioural control.

Overall, these findings have important implications for speed management strategies, highlighting the urgent need for effective measures in urban areas and highways of Cameroon. Efforts to change attitudes towards speeding could result in corresponding changes in speeding intention and subsequent alterations in speed behaviour. Additionally, perceived behavioural control plays a critical role in influencing drivers' speeding behaviour and should also be targeted. To address the high prevalence of speeding and reduce associated risks and fatalities, it is crucial to raise awareness of speed limits among drivers (especially motorcycle riders, who often don’t have formal trainings), improve traffic regulations and enforcement, introduce speed management technologies like speed limiters and implement targeted interventions. It is worth noting that these interventions should also include infrastructure change to optimize the expected benefits.

5. Conclusions

Excessive and inappropriate speeding continues to pose a road safety challenge in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) like Cameroon. However, the effective management of speeding in these countries is impeded by a lack of research. In Cameroon and its neighboring Sub-Saharan countries, there is often a dearth of studies on speeding behavior. This study aims to address these gaps by examining the prevalence of self-reported speeding and the factors influencing drivers' speeding behavior, as guided by the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). A survey was conducted online, involving 387 anonymous drivers from the capital city, Yaoundé. The survey questionnaire covered demographic characteristics, driver-related factors, and TPB variables, including speed behavior, speeding intention, attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and perceived risk. Chi-square tests of association were employed to explore the relationship between self-reported non-compliance and demographic and driver-related factors. Hierarchical linear regression and structural equation modeling were employed to examine the factors influencing speeding behavior.

The results revealed that in urban areas, 81% of drivers exceeded speed limits by 5km/h, 12% exceeded by 10km/h, 4% exceeded by 15 to 20km/h, and 2% exceeded by more than 20km/h. The percentage of drivers exceeding the speed limit by more than 10km/h was higher on highways. Additionally, the study found that only 89% of drivers were aware of the speed limits, with tricycle and motorcycle drivers displaying significantly lower awareness. The statistical analysis confirmed a significant association between age, driver's license, and gender with speeding non-compliance, although the associations varied between urban areas and highways. Furthermore, the results of hierarchical linear regression analysis indicated that the inclusion of TPB variables accounted for a more than 50% proportionate increase in the variance of both speeding intention and speeding behavior, underscoring a strong relationship between TPB variables and speeding-related factors. Therefore, the TPB proves suitable for determining speeding intention and behavior in Cameroon. The structural equation modeling results revealed that while attitude was the only significant factor influencing speeding intention among the TPB variables, education level, gender, driver experience, and perceived risk were significant predictors of speeding intention. These factors indirectly influence speeding behavior through the mediating factor of speeding intention. In addition to the speeding intention, the perceived behavioral control also exhibited a substantial and significant impact on speeding behavior. These findings suggest that interventions targeting attitude, intentions, and perceived behavioral control can effectively modify speeding behavior.

However, despite the relevance of this study, there are certain limitations that should be considered in future research. The reliability of some constructs in the survey questions was low, potentially influencing the results. One possible issue could be the use of different evaluation scales within each construct which should resolved in future studies. In addition, the sample size was relatively small for tricycles and only moderately high for trucks, emphasizing the need for future studies with larger sample sizes , but also encompass the entire national territory rather than focusing solely on the capital city. Future research should also involve the measurement of actual driving speeds on urban roads and highways and compare them with self-reported data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, analysis, writing and original draft preparation by Stephen Kome Fondzenyuy.; data collection, cleaning, and treatment, by Christian Steven Fowo.; review and editing by Steffel Ludivin Feudjio Tezong. Methodology, review and editing by Davide Shingo Usami. Supervision and review by Luca Persia.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the administrative staff and students at the National Advanced School of Publics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- S. K. Fondzenyuy, B. M. Turner, A. F. Burlacu, and C. Jurewicz, “Title: The Contribution of Excessive or Inappropriate Speeds to Road Traffic Crashes and Fatalities: A Review of Literature,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Sheykhfard, F. Haghighi, G. Fountas, S. Das, and A. Khanpour, “How do driving behavior and attitudes toward road safety vary between developed and developing countries? Evidence from Iran and the Netherlands,” J Safety Res, no. xxxx, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Wallén Warner, T. Özkan, and T. Lajunen, “Cross-cultural differences in drivers’ speed choice,” Accid Anal Prev, 2009, 41, no. 4, 816–819. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang, D. (Jian) Sun, and J. Tang, “Taxi driver speeding: Who, when, where and how? A comparative study between Shanghai and New York City,” Traffic Inj Prev, 2018, 19, no. 3, 311–316. [CrossRef]

- T. Nordfjærn, Ö. Şimşekoǧlu, and T. Rundmo, “Culture related to road traffic safety: A comparison of eight countries using two conceptualizations of culture,” Accid Anal Prev, 2014, 62, 319–328. [CrossRef]

- P. Tankasem, T. Satiennam, and W. Satiennam, “Cross-Cultural differences in speeding intentions of drivers on urban road environments in asian developing countries,” International Journal of Technology, 2016, 7, no. 7, 1187–1195. [CrossRef]

- K. Torfs, S. Delannoy, L. Schinckus, B. Willocq, W. Van den Berghe, and U. Meesmann, “Road Safety culture in Africa Results from the ESRA2 survey in 12 African countries.ESRA project (E-Survey of Road users’ Attitudes). Brussels, Belgium: Vias institute,” Vias institute, Belgium, 2021.

- H. Qaid et al., “Speed choice and speeding behavior on Indonesian highways: Extending the theory of planned behavior,” IATSS Research, 2022, 46, no. 2, 193–199. [CrossRef]

- M. Alizadeh, S. R. Davoodi, and K. Shaaban, “Drivers’ Speeding Behavior in Residential Streets: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach,” Infrastructures (Basel)), 2023, 8, no. 1, 11. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Javid, N. Ali, S. A. H. Shah, and M. Abdullah, “Structural Equation Modeling of Drivers’ Speeding Behavior in Lahore: Importance of Attitudes, Personality Traits, Behavioral Control, and Traffic Awareness,” Iranian Journal of Science and Technology - Transactions of Civil Engineering, 2022, 46, no. 2, 1607–1619. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Javid and A. R. Al-Hashimi, “Significance of attitudes, passion and cultural factors in driver’s speeding behavior in Oman: application of theory of planned behavior,” Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot, 2020, 27, no. 2, 172–180. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Etika, N. Merat, and O. Carsten, “Do drivers differ in their attitudes on speed limit compliance between work and private settings? Results from a group of Nigerian drivers,” Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav, 2020, 73, 281–291. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, “The theory of planned behavior,” Organ Behav Hum Decis Process, Dec. 1991, 50, no. 2, 179–211. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ding, X. Zhao, Y. Wu, X. Zhang, C. He, and S. Liu, “How psychological factors affect speeding behavior: Analysis based on an extended theory of planned behavior in a Chinese sample,” Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav, 2023, 93, no. January, 143–158. [CrossRef]

- T. Nordfjærn, S. Jrgensen, and T. Rundmo, “A cross-cultural comparison of road traffic risk perceptions, attitudes towards traffic safety and driver behaviour,” J Risk Res, 2011, 14, no. 6, 657–684. [CrossRef]

- F. Judy and W. Barry, “The speed paradox: the misalignment between driver attitudes and speeding behaviour,” 2006, 17, no. 2006.

- P. De Pelsmacker and W. Janssens, “The effect of norms, attitudes and habits on speeding behavior: Scale development and model building and estimation,” Accid Anal Prev, 2007, 39, no. 1, 6–15. [CrossRef]

- WHO, “Global status report on road safety 2023,”. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240086517 (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- R. Elvik, A. Vadeby, T. Hels, and I. van Schagen, “Updated estimates of the relationship between speed and road safety at the aggregate and individual levels,” Accid Anal Prev, 2019, 123, no. October 2018, 114–122. [CrossRef]

- vias institute, “Cameroon – ESRA2 Country Fact Sheet. ESRA2 survey (E-Survey of Road users’ Attitudes). Brussels, Belgium: Vias institute.,”. 2020. Available online: https://www.esranet.eu/storage/minisites/esra2019countryfactsheetcameroon.

- A. N. Stephens, M. Nieuwesteeg, J. Page-Smith, and M. Fitzharris, “Self-reported speed compliance and attitudes towards speeding in a representative sample of drivers in Australia,” Accid Anal Prev, 2017, 103, no. June 2016, 56–64. [CrossRef]

- E. Guadagnoli and W. F. Velicer, “Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns,” Psychol Bull, 1988, 103, no. 2, 265–275. [CrossRef]

- D. Hooper, J. Coughlan, and M. R. Mullen, “Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit,” Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 2008, 6, no. 1, 53–60.

- R. Elvik, A. Vadeby, T. Hels, and I. van Schagen, “Updated estimates of the relationship between speed and road safety at the aggregate and individual levels,” Accid Anal Prev, 2019, 123, no. October 2018, 114–122. [CrossRef]

- W. A. Al-Hussein, M. L. M. Kiah, L. Y. Por, and B. B. Zaidan, “Investigating the effect of social and cultural factors on drivers in Malaysia: A naturalistic driving study,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021, 18, no. 22. [CrossRef]

- F. F. Mohamad, A. S. Abdullah, and J. Mohamad, “Are sociodemographic characteristics and attitude good predictors of speeding behavior among drivers on Malaysia federal roads?,” Traffic Inj Prev, 2019, 20, no. 5, 478–483. [CrossRef]

- S. Vardaki and G. Yannis, “Investigating the self-reported behavior of drivers and their attitudes to traffic violations,” J Safety Res, 2013, 46, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- S. O’Hern, V. Vuorio, and A. N. Stephens, “Kaahaajat: Finnish Attitudes towards Speeding,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2023, 20, no. 3, 1995. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Dinh and H. Kubota, “Speeding behavior on urban residential streets with a 30km/h speed limit under the framework of the theory of planned behavior,” Transp Policy (Oxf), 2013, 29, 199–208. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Etika, N. Merat, and O. Carsten, “Do drivers differ in their attitudes on speed limit compliance between work and private settings? Results from a group of Nigerian drivers,” Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav, 2020, 73, 281–291. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Forward, “The theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive norms and past behaviour in the prediction of drivers’ intentions to violate,” Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav, May 2009, 12, no. 3, 198–207. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).