Submitted:

04 March 2024

Posted:

05 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

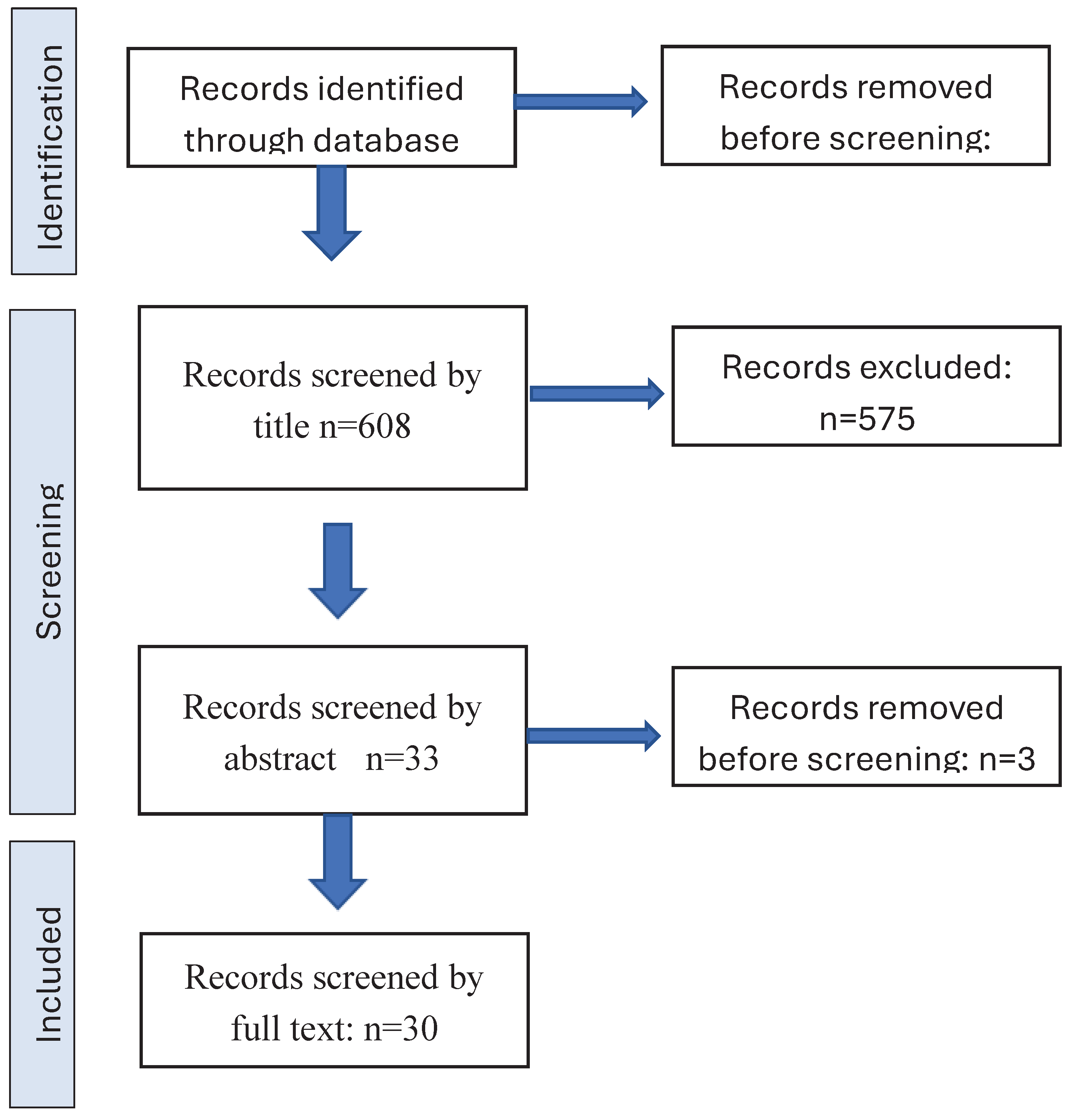

2. Methodology

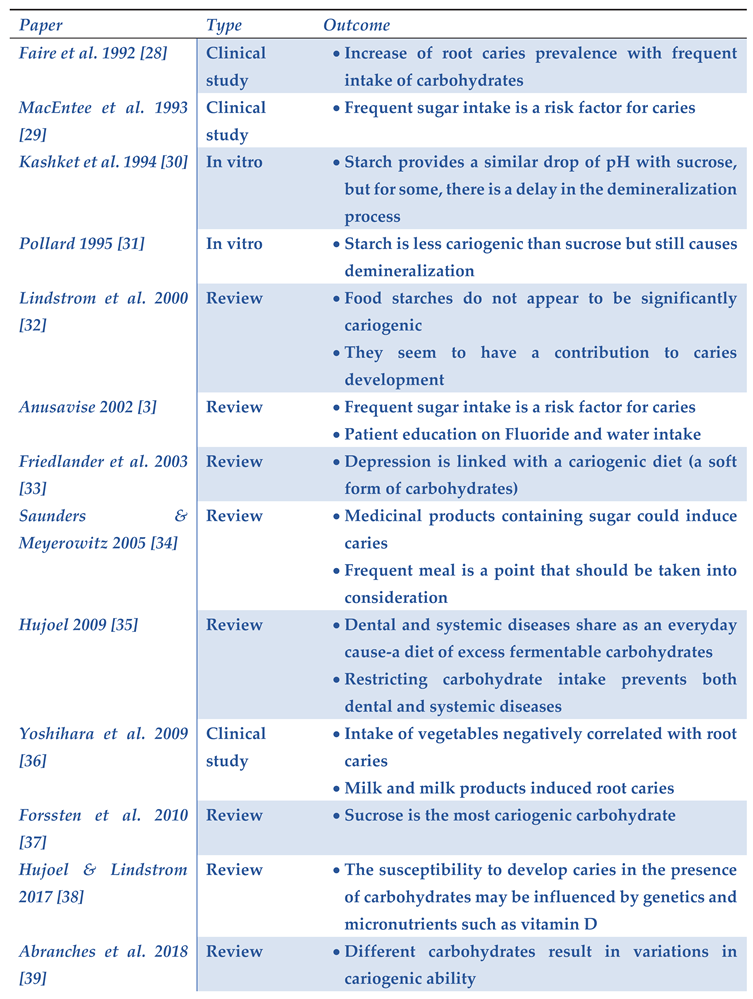

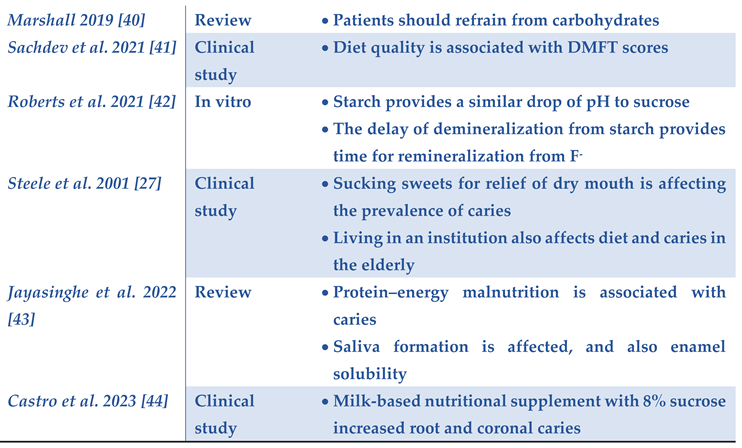

3. Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marchini L, Ettinger R, Hartshorn J. Personalized Dental Caries Management for Frail Older Adults and Persons with Special Needs. Dent Clin North Am 2019, Oct;63(4), 631-651. [CrossRef]

- Curzon ME, Preston AJ. Risk groups: nursing bottle caries/caries in the elderly. Caries Res 2004, 38 Suppl 1, 24-33. [CrossRef]

- Anusavice KJ. Dental caries: risk assessment and treatment solutions for an elderly population. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2002, Oct;23(10 Suppl),12-20.

- Tan HP, Lo EC. Risk indicators for root caries in institutionalized elders. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2014, Oct;42(5), 435-40. [CrossRef]

- Edman K, Öhrn K, Nordström B, Holmlund A, Hellberg D Trends over 30 years in the prevalence and severity of alveolar bone loss and the influence of smoking and socio-economic factors – based on epidemiological surveys in Sweden 1983–2013. Int J Dent Hyg 2015, 13, 283-291. [CrossRef]

- Wahlin Å, Papias A, Jansson H, Norderyd O. Secular trends over 40 years of periodontal health and disease in individuals aged 20–80 years in Jonkoping, Sweden: repeated cross-sectional studies. J Clin Periodontol 2018, 45, 1016-1024. [CrossRef]

- Featherstone JD. The continuum of dental caries--evidence for a dynamic disease process. J Dent Res 2004, 83(Spec No C:C39-42). [CrossRef]

- Kidd EA, Fejerskov O What constitutes dental caries? Histopathology of carious enamel and dentin related to the action of cariogenic biofilms. J Dent Res 2004, 83(Spec Iss C), C35-C38. [CrossRef]

- Locker D. Dental status, xerostomia and the oral health-related quality of life of an elderly institutionalized population. Spec Care Dentist 2003, 23(3), 86-93. [CrossRef]

- Ikebe K, Matsuda K, Morii K, Wada M, Hazeyama T, Nokubi T, Ettinger RL. Impact of dry mouth and hyposalivation on oral health-related quality of life of elderly Japanese. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007, Feb;103(2), 216-22. [CrossRef]

- Hahnel S, Schwarz S, Zeman F, Schafer L, Behr M, Prevalence of xerostomia and hyposalivation and their association with quality of life in elderly patients in dependence on dental status and prosthetic rehabilitation. A pilot study. Journal of Dentistry 2014, 42(6), 664-670. [CrossRef]

- Thomson WM, Lawrence HP, Broadbent JM, Poulton R. The impact of xerostomia on oral-health related quality of life among younger adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006, 8(4), 86. [CrossRef]

- Ohara Y, Hirano H, Yoshida H, Obuchi S, Ihara K, Fujiwara Y, Mataki S. Prevalence and factors associated with xerostomia and hyposalivation among community-dwelling older people in Japan. Gerodontology 2016, Mar;33(1), 20-7. [CrossRef]

- Johansson AK, Johansson A, Unell L, Ekback G, Ordell S Carsson GE, Self-reported dry mouth in Swedish population samples aged 50, 65 and 75 years. Gerodontology, 2012, 29, e107-115. [CrossRef]

- Turner MD, Ship JA. Dry mouth and its effects on the oral health of elderly people. JADA 2007, 138(Suppl), P15S-20S. [CrossRef]

- Napenas JJ, Brennan MT, Fox PC. Diagnosis and treatment of xerostomia (dry mouth). Odontology 2009, 97(2), 76-83. [CrossRef]

- Mignogna MD, Fedele S, Lo Russo L, Lo Muzio L, Wolff A. Sjogren ‘s Syndrome: The diagnostic potential of early oral manifestations precenting hyposalivation/xerostomia. J Oral Pathol Med 2005, 34(1), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Billings RJ, Proskin HM, Moss ME. Xerostomia and associated factors in a community-dwelling adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996, Oct;24(5),312-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg GE, Sundberg HE, Fjellstrom CA, Wikblad KF. Type 2 diabetes and oral health: a comparison between diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2000, 50(1), 27-34. [CrossRef]

- Soell M, Hassan M, Miliauskaite A, Haïkel Y, Selimovic D. The oral cavity of elderly patients in diabetes. Diabetes Metab 2007, 33 Suppl 1, S10-8. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos AC, Soares MS, Almeida PC, Soares TC. Comparative study of the concentration of salivary and blood glucose in type 2 diabetic patients. J Oral Sci, 2010, 52(2), 293-8. [CrossRef]

- Sreebny LM, Schwartz SS. A reference guide to drugs and dry mouthQ2nd edition. Gerodontology 1997, 14(1), 33-47. [CrossRef]

- Thomson WH, Chalmers JM, Spencer AJ, Slade ED. Medication and dry mouth: findings from a cohort study of older people. J Public Health Den 2000, 60(1), 12-20. [CrossRef]

- Scully C. Drug effects on salivary glands: dry mouth. Oral Diseases 2003, 9, 165-76. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson JC, Grisius M, Massey W. Salivary hypofunction and xerostomia: diagnosis and treatment. Dent Clin North Am 2005, 49(2),309-26. [CrossRef]

- McCann TV, Clark E, Lu S. Subjective side effects of antipsychotics and medication adherence in people with schizophrenia. J Adv Nursing 2009,534-43. [CrossRef]

- Steele JG, Sheiham A, Marcenes W, Fay N, Walls AW. Clinical and behavioural risk indicators for root caries in older people. Gerodontology. 2001 Dec;18(2):95-101. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faine MP, Allender D, Baab D, Persson R, Lamont RJ. Dietary and salivary factors associated with root caries. Spec Care Dentist. 1992 Jul-Aug;12(4):177-82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacEntee MI, Clark DC, Glick N. Predictors of caries in old age. Gerodontology 1993, Dec;10(2), 90-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashket S, Yaskell T, Murphy JE. Delayed effect of wheat starch in foods on the intraoral demineralization of enamel. Caries Res 1994, 28(4), 291-6. doi: 10.1159/000261988. PMID: 8069887. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard MA. Potential cariogenicity of starches and fruits as assessed by the plaque-sampling method and an intraoral cariogenicity test. Caries Res 1995, 29(1), 68-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingström P, Liljeberg H, Björck I, Birkhed D. The relationship between plaque pH and glycemic index of various breads. Caries Res 2000 Jan-Feb;34(1), 75-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedlander AH, Friedlander IK, Gallas M, Velasco E. Late-life depression: its oral health significance. Int Dent J. 2003 Feb;53(1):41-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders RH, Meyerowitz C. Dental caries in older adults. Dental Clinics of North America 2005, 49(2), 293–308. [CrossRef]

- Hujoel, P. Dietary carbohydrates and dental-systemic diseases. Journal of Dental Research 2009, 88, 490–502. [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara A, Watanabe R, Hanada N, Miyazaki H. A longitudinal study of the relationship between diet intake and dental caries and periodontal disease in elderly Japanese subjects. Gerodontology 2009, Jun;26(2), 130-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forssten SD, Björklund M, Ouwehand AC. Streptococcus mutans, caries and simulation models. Nutrients 2010, Mar;2(3), 290-8. [CrossRef]

- Hujoel PP, Lingström P. Nutrition, dental caries and periodontal disease: a narrative review. J Clin Periodontol 2017, Mar;44 Suppl 18, S79-S84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abranches J, Zeng L, Kajfasz JK, Palmer SR, Chakraborty B, Wen ZT, Richards VP, Brady LJ, Lemos JA. Biology of Oral Streptococci. Microbiol Spectr 2018, Oct;6(5),10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0042-2018. [CrossRef]

- Marshall TA. Dietary Implications for Dental Caries: A Practical Approach on Dietary Counseling. Dent Clin North Am 2019, Oct;63(4), 595-605. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev PK, Freeland-Graves J, Babaei M, Sanjeevi N, Zamora AB, Wright GJ. Associations Between Diet Quality and Dental Caries in Low-Income Women. J Acad Nutr Diet 2021, Nov;121(11), 2251-2259. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts JM, Bradshaw DJ, Lynch RJM, Higham SM, Valappil SP. The cariogenic effect of starch on oral microcosm grown within the dual constant depth film fermenter. PLoS ONE 2021, 16(10), e0258881. [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe TN, Harrass S, Erdrich S, King S, Eberhard J. Protein Intake and Oral Health in Older Adults-A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, Oct 25;14(21):4478. [CrossRef]

- Castro RJ, Gambetta-Tessini K, Clavijo I, Arthur RA, Maltz M, Giacaman RA. Caries Experience in Elderly People Consuming a Milk-Based Drink Nutritional Supplement: A Cross-Sectional Study. Caries Res. 2023;57(3):211-219. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guideline: Sugars Intake for Adults and Children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2008. Diabetes Care 2008, Jan;31 Suppl 1,S12-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NNR. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2012. Nordic Council of Ministers 2014, Narayana Press. ISBN 978-92-893-2.

- Lingström P, van Houte J, Kashket S. Food starches and dental caries. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2000, 11(3), 366-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zussman E, Yarin AL, Nagler RM. Age- and flow-dependency of salivary viscoelasticity. J Dent Res 2007, Mar;86(3,:281-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho TS, Lussi A. Age-related morphological, histological and functional changes in teeth. J Oral Rehabil 2017, Apr;44(4),291-298. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettinger RL. The unique oral health needs of an aging population. Dent Clin North Am 1997, Oct;41(4), 633-49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quirk SE, Williams LJ, O’Neil A, Pasco JA, Jacka FN, Housden S, Berk M, Brennan SL. The association between diet quality, dietary patterns and depression in adults: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2013, Jun 27;1, 175. [CrossRef]

- Petersen PE Sociobehavioural risk factors in dental caries – international perspectives. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2005, 33(4), 274-279. [CrossRef]

- Ritter AV, Shugars DA, Bader JD. Root caries risk indicators: a systematic review of risk models. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2010, Oct;38(5), 383-97. [CrossRef]

- Locker D. Incidence of root caries in an older Canadian population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996, 24, 403–7. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence HP, Hunt RJ, Beck JD. Three-year root caries incidence and risk modeling in older adults in North Carolina. J Public Health Dent 1995, 55, 69–78. [CrossRef]

- Powell LV, Mancl LA, Senft GD. Exploration of prediction models for caries risk assessment of the geriatric population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1991, 19, 291–5. [CrossRef]

- Gati D, Vieira AR. Elderly at greater risk for root caries: a look at the multifactorial risks with emphasis on genetics susceptibility. Int J Dent 2011, 2011:647168. [CrossRef]

- Johnson MF. The role of risk factors in the identification of appropriate subjects for caries clinical trials: design considerations. J Dent Res 2004, 83(Spec No C), C116–8.

- Edman K, Holmlund A, Norderyd O. ‘Caries disease among an elderly population-A 10-year longitudinal study’. Int J Dent Hyg 2021, May;19(2),166-175. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White DA, Tsakos G, Pitts NB, Fuller E, Douglas GV, Murray JJ, Steele JG. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009: common oral health conditions and their impact on the population. Br Dent J 2012, Dec;213(11), 567-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers JM. Minimal intervention dentistry: part 1. Strategies for addressing the new caries challenge in older patients. J Can Dent Assoc 2006, Jun;72(5), 427-33.

- Yoshihara A, Suwama K, Miyamoto A, Watanabe R, Ogawa H. Diet and root surface caries in a cohort of older Japanese. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2021, Jun;49(3), 301-308. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu L, Zhang Y, Wu W, Cheng M, Li Y, Cheng R. Prevalence and correlates of dental caries in an elderly population in northeast China. PLoS One 2013, Nov 19;8(11), e78723. [CrossRef]

- Shah N, Sundaram KR. Impact of socio-demographic variables, oral hygiene practices, oral habits and diet on dental caries experience of Indian elderly: a community-based study. Gerodontology 2004, Mar;21(1), 43-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papas AS, Joshi A, Palmer CA, Giunta JL, Dwyer JT. Relationship of diet to root caries. Am J Clin Nutr 1995, Feb;61(2), 423S-429S. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi N, Nyvad B. Ecological Hypothesis of Dentin and Root Caries. Caries Res 2016,50(4),422-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke A, MacInnes A. What are the main factors associated with root caries? Evid Based Dent 2021, Jan;22(1),16-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa SM, Martins CC, Bonfim Mde L, Zina LG, Paiva SM, Pordeus IA, Abreu MH. A systematic review of socioeconomic indicators and dental caries in adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012, Oct 10,9(10), 3540-74. [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke F, Dörfer CE, Schlattmann P, Foster Page L, Thomson WM, Paris S. Socioeconomic inequality and caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Res 2015, Jan;94(1), 10-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Listl S. Income-related inequalities in dental service utilization by Europeans aged 50+. J Dent Res 2011, 90, 717–23. [CrossRef]

- Han DH, Khang YH, Choi HJ. Association of parental education with tooth loss among Korean Elders. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2015, 43, 489–99. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Cheng L, Yuan B, Hong X, Hu T. Association between socio-economic status and dental caries in elderly people in Sichuan Province, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017, Sep 24;7(9, :e016557. [CrossRef]

- Hobdell MH, Oliveira ER, Bautista R, et al. Oral diseases and socioeconomic status (SES). Br Dent J 2003, 194, 91–6. discussion 88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele J, Shen J, Tsakos G, Fuller E, Morris S, Watt R, Guarnizo-Herreño C, Wildman J. The Interplay between socioeconomic inequalities and clinical oral health. J Dent Res 2015, Jan;94(1), 19-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim DW, Park JC, Rim TT, Jung UW, Kim CS, Donos N, Cha IH, Choi SH. Socioeconomic disparities of periodontitis in Koreans based on the KNHANES IV. Oral Dis 2014, Sep;20(6), 551-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazaki Y, Soh I, Koga T, Miyazaki H, Takehara T. Risk factors for tooth loss in the institutionalised elderly; a six-year cohort study. Community Dent Health 2003, Jun;20(2), 123-7. [PubMed]

- Ellefsen B, Holm-Pedersen P, Morse DE, Schroll M, Andersen BB, Waldemar G. Assessing caries increments in elderly patients with and without dementia: a one-year follow-up study. J Am Dent Assoc 2009, Nov;140(11), 1392-400. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega O, Parra C, Zarcero S, Nart J, Sakwinska O, Clavé P. Oral health in older patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Age Ageing 2014, Jan;43(1), 132-7. [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).