1. Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the act of wearing a face mask has transcended its medical origins to become a global norm in daily practice [

1]. As a result of public health policies, the presence of masks extended beyond everyday life into work settings as well. After the pandemic, mask-wearing remains a prevalent and unique social common practice without mandatory requirements. In addition to serving as a protective barrier against the virus [

1], mask can generate a range of psychological spillover effects. Existing research has examined the psychological effects of mask-wearing on wearers in everyday life. For instance, masks can help people reduce the fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety in face-to-face interactions because of the self-concealing functions [

2,

3,

4]. In addition, masks have emerged as a moral symbol that reduces wearers’ deviant behavior by heightening their moral awareness [

5].

However, few studies have addressed the implications of mask-wearing in the workplace, particularly concerning its influence on employee attitudes and behaviors. Given the psychological benefits associated with masks as mentioned above, notably, the elevation of moral awareness and reduction of social anxiety, we speculate that mask-wearing might foster some beneficial yet potentially risky behaviors in the workplace. To help address this knowledge gap, this study aims to examine the effect of employees’ mask-wearing in the workplace on their voice behavior, which is defined as an informal and discretionary expression of constructive opinions, concerns, or ideas about work-related issues [

6,

7,

8,

9]. On the one hand, employees’ voices have long been recognized as key drivers of positive outcomes such as team performance and crisis prevention [

10,

11]. On the other hand, voice behavior can be risky since it might challenge the status quo and bring forth undesirable social consequences and deplete personal resources [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Thus, we believe that wearing masks may likely encourage voice behavior.

Drawing on self-perception theory, this study argues that employees’ mask-wearing might positively affect their voice behavior and introduces psychological safety as an underlying mediation mechanism. Self-perception theory indicates that individuals’ internal reflections on their actions in interaction contexts (e.g., wearing a mask) can influence their subsequent behavioral outcomes [

17,

18]. In the workplace, employees often remain silent because of their uncertainty about whether their suggestions will be approved and endorsed, as well as their fear of negative evaluations and personal costs [

6,

7,

9]. Masks can cover a large part of the face and help conceal wearers’ identities, which promotes the internal reflections on interpersonal situations as less risky and worrying, and consequently reduces the difficulties of engaging in voice behavior. This internal reflection process is closely related to psychological safety, defined as perceptions of showing the authentic self without fear of negative fear of negative consequences [

19].

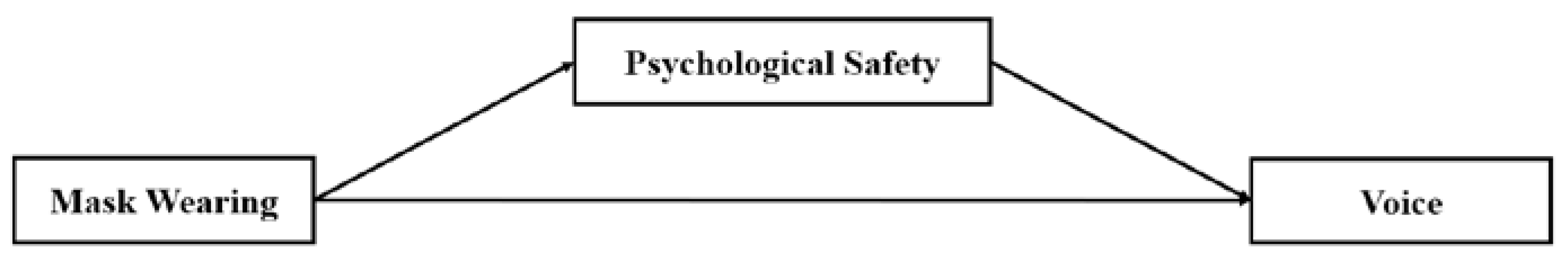

In summary, this study investigates the relationship between mask-wearing and voice behavior, focusing on the mediating effect of psychological safety (

Figure 1). It makes several contributions to the literature. First, by exploring the psychological and behavioral consequences of employees’ mask-wearing in the workplace, we extend the research on the effect of mask-wearing beyond its benefits in people’s health conditions and everyday life. Second, we explore how a seemingly minor behavioral habit like wearing masks in the workplace changes employees’ voice behavior, which can bring about improvement and change to the organization. Third, we draw on self-perception theory and identify psychological safety as a key mechanism explaining why masks can promote wearers’ voice behavior in the workplace.

2. Hypothesis Development

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, masks have become a necessity in everyday life. During the pandemic, wearing masks was a public health policy implemented for pandemic prevention, particularly serving as a safety norm within the workplace. After the pandemic, people have continued to wear masks in their everyday lives and work, even in the absence of compulsory regulations. We argue that employees’ voluntary mask-wearing will promote their voice behavior via psychological safety. Psychological safety was defined as the extent to which individuals feel safe to exhibit and express their authentic selves at work [

19]. In line with this conceptualization, researchers suggest that psychological safety reflects a sense of safety regarding self-expression and interpersonal risk taking, such that employees do not feel that they would be resented or rejected when involved in situations such as making mistakes and speaking up with different opinions [

20]. In the following section, we first theorize how mask-wearing is related to psychological safety, and subsequently, how psychological safety shapes voice behavior.

We draw on self-perception theory [

17] to explain the relationship between mask-wearing and psychological safety. Self-perception theory suggests that individuals come to know their own emotions, cognitions, and other inner states by inferring them from observation of their overt behavior and interpersonal situations. Specifically, engaging in a behavior prompts a self-attribution process, in which individuals reflect on this behavior and consider the conditions that have caused them to behave in this way [

21]. In line with this reasoning, employees who wear masks in the workplace are likely to feel about their internal states (e.g., perceived safety) by inferring from observations of their mask-wearing and the associated contexts. We argue that mask-wearing behavior can lead to the reflection on internal states of psychological safety in three ways.

First, mask-wearing is recognized as both a societal norm and a workplace safety protocol. During the pandemic, masks are widely accepted as a preventative measure and viewed as a moral symbol, representing the moral duty and virtue of protecting others and sacrificing one’s personal convenience for the collective welfare, especially in countries that value collectivism [

22]. Existing research have found that masks may reduce wearers’ deviance by increasing their moral awareness [

23]. Therefore, when wearing masks, individuals might consider themselves as adhering to a secure social norm, which will enhance their perceptions of psychological safety.

Second, masks may also serve as a self-protective ritual for individuals. Psychological research indicates that rituals, characterized by fixed, repetitive patterns, can evoke emotional resonance and stimulate positive emotions, thereby boosting confidence and self-esteem, while helping individuals alleviate stress and anxiety [

24,

25]. Therefore, the act of wearing a mask can be considered as a self-protective ritual [

26], potentially augmenting individuals’ sense of control and psychological safety.

Third, the relationship between mask-wearing and psychological safety can also be explained through deindividuation. Masks cover a large part of the face and help conceal wearers’ identities [

27]. Existing research indicates that wearing masks enhances individuals’ sense of anonymity, which in turn diminishes social visibility and social desirability concerns, contributing to a significant increase in psychological safety [

28,

29]. It provokes the perception that the situation is safe for self-expression and interpersonal risk taking. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Employees’ mask-wearing has a positive effect on their psychological safety.

We now turn to the relationship between psychological safety and voice behavior. Voice behavior refers to the discretionary expression of constructive ideas, opinions, and concerns about work-related issues, which is crucial for continuous improvement and effective organizational decision-making [

6,

8,

30]. Despite the benefits, employees are often reluctant to engage in voice behavior, as it demands high resource consumption and potential risks such as undermining their credibility and receiving a negative performance evaluation [

12,

31,

32]. Psychological safety refers to the extent to which individuals believe they would not be punished or misunderstood when they engage in risky behaviors, such as speaking up with suggestions or concerns [

19,

33]. When employees are free of fears and concerns about expressing their opinions, the perceived costs of voice would be minimized and the perceived benefits of voice would be amplified. In contrast, when psychological safety is lacking, employees feel that they cannot freely express themselves, and these fears and concerns cause them to avoid publicly expressing their opinions and concerns. In line with this reasoning, psychological safety has been thought to facilitate voice because such perceptions reduce the felt risk associated with presenting ideas [

20,

34]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Psychological safety has a positive effect on voice behavior.

According to Hypotheses 1 and 2, we argue that employees’ mask-wearing will promote their voice behavior via psychological safety. Self-perception theory indicates that individuals’ internal reflections on their actions and the associated contexts can shape their subsequent behavioral responses [

17]. Employees who wear masks in the workplace are likely to consider their mask-wearing as self-protective, which leads to perceived psychological safety. The perception that the situation is safe for self-expression and interpersonal risk taking will further promote voice behavior. Empirical work has also shown that psychological safety mediates the relationship between contextual factors (such as leadership) and employee voice behavior [

33,

35]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Psychological safety mediates the positive relationship between employees’ mask-wearing and voice behavior.

3. Methods

We conducted an online experiment in China to test our hypotheses, using a within-subject design. We chose to focus on China for several reasons. First, mask-wearing is predominantly a public-health concern in China, whereas it has been a politically divisive issue in some other countries, which have witnessed anti-mask campaigns [

22,

36,

37,

38]. Chinese citizens are used to being asked to put on masks in daily life and at their workplaces. Even after the pandemic, many of them continue to maintain the habit of wearing masks in their daily lives. Second, Chinese people tend to value superficial harmony, which is aligned with a self-protective and defensive orientation [

39,

40]. In such a culture, individuals are concerned about how others perceive them and their actions, which makes it appropriate to examine the self-concealing effect of masks.

3.1. Participants

A total of 300 working adults were recruited from the Credemo platform, a large-scale experiment platform in China. Nine of them were excluded because they failed the attention check, leaving a final sample of 291 participants. Among the 291 participants, 46.0% were male and 52.0% were female, with an average age of 26.1 years (SD = 4.97). Participants all had working experience and engaged in face-to-face work communication in their workplaces, with employment in different organizations, including governments (5.2%), public institutions (26.8%), private enterprises (38.8%), state-owned enterprises (24.0%), and foreign-funded enterprises (5.2%).

3.2. Procedure and Materials

We conducted an online vignette experiment using a within-subject design. Participants were presented with two distinct scenarios in which they were asked to imagine themselves as members of a sales team during a quarterly review meeting. In this meeting, team members would first summarize their individual work achievements and then give suggestions for improvements.

In Scenario 1, participants were instructed to envision that they are attending this meeting without wearing a mask. Accompanying this instruction, a scenario image depicted the participant in a non-mask-wearing state (as illustrated in

Figure 2). Participants were then informed of various dissatisfactions within their team, such as unreasonable job division, poor work atmosphere, and low efficiency from certain colleagues. After reading the scenario, participants completed an attention check. Then they completed a survey that measured their psychological safety and voice behavior.

After this survey, we asked participants to read Scenario 2, which mirrored Scenario 1 with one critical variation: participants were prompted to imagine that they are attending the same meeting, but this time, wearing a mask. In the image, we depicted a natural workplace setting where several team members are wearing masks, rather than only the speaker. The scenario’s accompanying image reflected this masked state (as shown in

Figure 3). After reading the scenario, participants also completed an attention check. Then they completed the same survey that measured their psychological safety and voice behavior.

Figure 2.

Image in Scenario 1 (non-mask-wearing condition). The picture was originated from the Internet and modified.

http://xhslink.com/6mggdB.

Figure 2.

Image in Scenario 1 (non-mask-wearing condition). The picture was originated from the Internet and modified.

http://xhslink.com/6mggdB.

Figure 3.

Image in Scenario 2 (mask-wearing version). The picture was originated from the Internet and modified.

http://xhslink.com/6mggdB.

Figure 3.

Image in Scenario 2 (mask-wearing version). The picture was originated from the Internet and modified.

http://xhslink.com/6mggdB.

3.3. Measures

We used 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”) for all substantive variables. We employed translation and back-translation procedures [

41] to translate all English items into Chinese.

Psychological safety was measured using the 5-item scale developed by Liang et al. [

34] in the Chinese context. Sample items: “In my work unit, I can express my true feelings regarding my job”, “In my work unit, I can freely express my thoughts.” The Cronbach’s α coefficient = 0.82 (scenario 1); 0.77 (scenario 2).

Voice behavior was measured using the 10-item scale developed by Liang et al. [

34] in the Chinese context, which includes 5 items of promotive voice and 5 items of prohibitive voice. Sample items: “Proactively develop and make suggestions for issues that may influence the unit.” “Dare to voice out opinions on things that might affect efficiency in the work unit, even if that would embarrass others.” The Cronbach’s α coefficient = 0.92 (scenario 1); 0.92 (scenario 2).

4. Results

First, the within-subject effect of mask-wearing on psychological safety and voice behavior was tested with paired-sample

t-tests. Mediation effects were probed with the MEMORE macro developed by Montoya and Hayes [

42].

4.1. Within-Subject Main Effects

We used a paired sample t-test to analyze the difference in voice behavior under mask-wearing and non-mask-wearing conditions. In support of our prediction, participants reported that they were more likely to engage in voice behavior when they imagined wearing a mask in the conference (M = 3.85, SD = 0.82) than not wearing a mask in the conference (M = 3.74, SD = 0.82), with d = 0.14, t(290) = 2.58 and p = 0.01,. This suggests that employees’ mask-wearing has a positive effect on their voice behavior.

A paired sample t-test was also employed to analyze the difference in psychological safety under mask-wearing and non-mask-wearing conditions. As predicted, participants reported that they perceived higher psychological safety when they imagined wearing a mask in the conference (M = 3.56, SD = 0.82) than not wearing a mask in the conference (M = 3.42, SD = 0.87), with d = 0.17,

t(290) = 3.22 and

p = 0.001,. This suggests that employees’ mask-wearing has a positive effect on their psychological safety.

Table 1.

Paired Sample T-test Results.

Table 1.

Paired Sample T-test Results.

| |

Non-mask-wearing

M (SD) |

Mask-wearing

M (SD) |

d |

t |

df |

p |

| Voice behavior |

3.85 (0.82) |

3.74 (0.82) |

0.14 |

2.58 |

290 |

0.01 |

| Psychological safety |

3.42 (0.87) |

3.56 (0.82) |

0.17 |

3.22 |

290 |

0.001 |

4.2. Mediation Effects

We followed the procedure described by Montoya and Hayes [

42] for testing mediation in within-subject designs. Specifically, we used the MEMORE macro to test whether the positive effect of mask-wearing on voice behavior can be mediated by psychological safety. Different from between-subject design, as the independent variable does not actually exist in the data, the effect of the independent variable would be reflected in the impact of the difference in the mediating variable on the difference in the dependent variable between the two conditions, while controlling for the average of the mediating variable in both conditions. Regression results showed that the difference in psychological safety on the difference in voice behavior between non-mask-wearing and mask-wearing conditions were significant and positive (b = 0.68, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.60, 0.77]), and the difference of voice behavior between non-mask-wearing and mask-wearing conditions was not significant from 0 (b = 0.02, SE = 0.03, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [-0.05, 0.08]). This indicated that psychological safety fully mediated the relationship between mask-wearing and voice behavior. In addition, bootstrapping analysis with 5000 interactions showed that the indirect effect of mask-wearing on voice behavior via psychological safety was significant (b = 0.10, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.16]). Therefore, our hypotheses were all supported.

5. Discussion

After the pandemic, many people keep the habit of wearing masks in their daily routines. Drawing on self-perception theory, this study examined the positive effect of mask-wearing in the workplace on wearers’ voice behavior through psychological safety. An online experiment using a within-subject manipulation of wearing masks supported our hypotheses.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This research offers important theoretical contributions to the literature of the psychology of mask wearing and voice behavior in several ways.

Firstly, our findings bridge a significant gap in the literature concerning the effects of mask-wearing. While previous studies have explored the psychological impacts of mask-wearing in daily life, such as reduced social anxiety and deviant behavior [

2,

3,

4,

5], little attention has been paid to its effects in the workplace settings. By exploring the psychological and behavioral consequences of employees’ mask-wearing, we extend the research on the effect of mask-wearing beyond its benefits in people’s health conditions and everyday life.

Secondly, research on antecedents to voice behavior has predominantly focused on organizational context and individual characteristics [

7], often overlooking minor behavioral habits in the workplace. We examined the effect of employees’ mask-wearing in the workplace on their voice behavior, which broadened the understanding of factors that contribute to employee voice.

Thirdly, as the first to draw on and build upon self-perception theory [

17] in the context of mask-wearing in the workplace, this research provides a unique insight to explain why masks can promote wearers’ voice behavior. Our research suggests that mask-wearing as a behavior can function to evoke changes in an individual's psychological state. Notably, we found that employees who wear masks might experience increased psychological safety because of the self-protection function of masks, which subsequently results in increased voice behavior.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our study encourages a broader perspective on mask-wearing in the workplace and has important practical implications for employees and managers. Mask-wearing can be viewed as distant, disrespectful, uncooperative and lead to misunderstandings because of inadequate facial expressions and dissatisfying communication experiences [

43,

44,

45]. Contrary to these views, our research reveals the positive aspects of mask-wearing. Our empirical results inspire managers in organizations to view mask-wearing as a positive behavior that enhances employees’ psychological safety and proactive behaviors such as voice. Thus, maintaining an equitable and respectful stance towards employees who choose to wear masks voluntarily could facilitate a more inclusive environment and encourage a richer diversity of employee perspectives.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

The current research has several limitations, which provide opportunities for future research.

Firstly, our research methods can be enhanced. Despite employing an experimental approach, the online nature and within-subject design call for improvements in internal and external validity. Future research could benefit from mixed methods and varied measures, such as adopting a between-subject design to mitigate sequence effects and measuring actual voice behavior instead of intentions.

Secondly, future research should explore additional outcomes of mask-wearing. We only examined the positive effect of mask-wearing on wearers’ voice behavior, it is also worth studying how mask-wearing can influence wearers’ other behaviors with contradictory nature, such as unethical pro-organizational behavior [

46]. Meanwhile, in the workplace, how observers (e.g., leader, coworkers) would perceive and respond to mask-wearing behavior can also be explored. Moreover, the moderating effects of contextual factors such as leadership, the status of mask wearers, as well as individual traits, on the relationship between mask-wearing and voice behavior should be further investigated.

Thirdly, our exploration of boundary conditions was limited. Since this study was conducted in a Chinese context, it’s uncertain if our findings are generalizable to other countries and cultural settings. Traditional Chinese values concerning high power distance may make voice a particularly risky behavior [

47]. Meanwhile, the self-protective function masks might be more salient in Chinese culture since mask-wearing has been a politically divisive issue in China rather than some other countries, which have witnessed anti-mask campaigns [

22,

38]. Furthermore, the Chinese cultural emphasis on maintaining harmonious interpersonal relationships may have increased the relative importance of psychological safety in predicting voice behavior in our sample. We recommend that future research more systematically examine the effects of culture on our model and determine whether the pattern of our findings is unique to our research context.

6. Conclusions

Drawing on self-perception theory, this study examined the positive influence of mask wearing in workplace on wearers’ voice behavior through psychological safety. An online experiment using a within-subject manipulation of wearing masks supported our hypotheses. This study sheds light on the broader psychological and behavioral implications of mask-wearing, extending beyond its recognized health and mental benefits, and contributing to the understanding of workplace dynamics in the post-pandemic era.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.S. and Y.L; methodology, Z.S. and Y.L; software, Y.L. and Z.C.; validation, Y.L.; formal analysis, Z.C. and Y.L.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, Z.S. and Y.L; data curation, Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.C. and Y.L; writing—review and editing, Z.C., Z.S., X.S. and M.X.; visualization, Z.S.; supervision, Z.S.; project administration, Z.S.; funding acquisition, Z.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Nature Science Foundation of China, grant number 72274021; and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number 2019NTSS37.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guanghua School of Management of Peking University (protocol code #2023-33; acceptation date: 22 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in the current study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. DongJu from Beijing Normal University for her comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank the support from Center for Statistical Science in Peking University, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Peking University LMEQF.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Howard, J.; Huang, A.; Li, Z.; Tufekci, Z.; Zdimal, V.; Van Der Westhuizen, H.-M.; et al. An evidence review of face masks against COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, 118, e2014564118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint, S.A.; Moscovitch, D.A. Effects of mask-wearing on social anxiety: an exploratory review. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2021, 34, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, A.R.; Davine, T.P.; Siwiec, S.G.; Lee, H.-J. The functional value of preventive and restorative safety behaviors: A systematic review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016, 44, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuming, S.; Rapee, R.M.; Kemp, N.; Abbott, M.J.; Peters, L.; Gaston, J.E. A self-report measure of subtle avoidance and safety behaviors relevant to social anxiety: Development and psychometric properties. J Anxiety Disord. 2009, 23, 879–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.G.; Song, L.L.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.C. Masks as a moral symbol: Masks reduce wearers’ deviant behavior in China during COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022, 119, e2211144119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, E.W. Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Acad Manag Ann. 2011, 5, 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W. Employee voice and silence. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L.; LePine, J.A. Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L.; Ang, S.; Botero, I.C. Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1359–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherf, E.N.; Sinha, R.; Tangirala, S.; Awasty, N. Centralization of member voice in teams: Its effects on expertise utilization and team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.N.; Tangirala, S. How employees’ voice helps teams remain resilient in the face of exogenous change. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 107, 668–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burris, E.R. The risks and rewards of speaking up: Managerial responses to employee voice. Acad. Manage. J. 2012, 55, 851–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W.; Milliken, F. J. Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2000, 25, 706–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarifard, Z.; Krasikova, D.V. Losing sleep over speaking up at work: A daily study of voice and insomnia. J. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 108, 1559–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zhu, R.; Yang, Y. I warn you because I like you: Voice behavior, employee identifications, and transformational leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, N.J.; Burris, E.R.; Bartel, C.A. Managing to stay in the dark: Managerial self-efficacy, ego defensiveness, and the aversion to employee voice. Acad. Manage. J. 2014, 57, 1013–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, D.J. Self-perception theory. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychology. 1972, 6, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiken, S.; Baldwin, M.W. Affective-cognitive consistency and the effect of salient behavioral information on the self-perception of attitudes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manage. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, J.L.; Rosopa, P.J. Workplace romances: Examining attitudes experience, conscientiousness, and policies. J of Manag Psychol. 2015, 30, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.G.; Jin, P.; English, A.S. Collectivism predicts mask use during COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, 118, e2021793118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.G.; Song, L.L.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.C. Masks as a moral symbol: Masks reduce wearers’ deviant behavior in China during COVID-19. PNAS. 2022, 119, e2211144119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks A, .W.; Schroeder, J.; Risen, J.L.; et al. Don’t Stop Believing: Rituals Improve Performance by Decreasing Anxiety. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes. 2016, 137, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, A.D.; Schroeder, J.; Häubl, G.; Risen, J.L.; Norton, M.I.; Gino, F. Enacting rituals to improve self-control. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 114, 851–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; Horii, M. Risk, ritual and health responsibilisation: Japan’s ‘safety blanket’ of surgical face mask-wearing. Sociol. Health Illn. 2012, 34, 1184–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimbardo, P.G. The Human Choice: Individuation, Reason, and Order Versus Deindividuation, Impulse, and Chaos. Nebr. Symp. Motiv. 1969, 17, 237–307. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, B.H.; Adam, D.G.; Chen, B.Z. Drunk, Powerful, and in the Dark: How General Processes of Disinhibition Produce Both Prosocial and Antisocial Behavior. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B.; Galinsky, A.D.; Zhong, C.B. Drunk, powerful, and in the dark: How general processes of disinhibition produce both prosocial and antisocial behavior. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashshur, M.R.; Oc, B. When voice matters: A multilevel review of the impact of voice in organizations. J Manage. 2015, 41, 1530–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Employee voice behavior: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, Z.X.; Chen, X.P. I will speak up if my voice is socially desirable: a moderated mediating process of promotive versus prohibitive voice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detert, J.R.; Burris, E.R. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Acad. Manage. J. 2007, 50, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J., Farh. Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Acad. Manage. J. 2012, 55, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Schaubroeck, J. Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badillo-Goicoechea, E.; Chang, T.H.; Kim, E.; LaRocca, S.; Morris, K.; Deng, X.; Chiu, S.; Bradford, A.; Garcia, A.; Kern, C.; Cobb, C. Global trends and predictors of face mask usage during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Knobel, P. Face mask wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic: comparing perceptions in China and three European countries. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 1199–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinas, S.R.; Maner, J.K.; Plant, E.A. What factors underlie attitudes regarding protective mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic? Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 181, 111038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, K.; Brew, F.P.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Zhang, Y. Harmony and conflict: A cross-cultural investigation in China and Australia. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2011, 42, 795–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; Koch, P.T.; Lu, L. A dualistic model of harmony and its implications for conflict management in Asia. Asia Pacific J. Manag. 2002, 19, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and translation of research instruments. Field methods in cross-cultural research. Sage Publications, Inc. 1986, 137-164. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1987-97046-005.

- Montoya, A.K.; Hayes, A.F. Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: a path-analytic framework. Psychol. Methods. 2017, 221, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbon, C.C. Wearing face masks strongly confuses counterparts in reading emotions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freud, E.; Di Giammarino, D.; Camilleri, C. Mask-wearing selectivity alters observers’ face perception. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2022, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawagoe, T.; Teramoto, W. Mask wearing provides psychological ease but does not affect facial expression intensity estimation. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 230653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E.E.; Bingham, J.B. When employees do bad things for good reasons: examining unethical pro-organizational behaviors. Organiz. Sci. 2011, 22, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Van de Vliert, E.; Van der Vegt, G. Breaking the silence culture: Stimulation of participation and employee opinion withholding cross-nationally. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2005, 1, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).