Submitted:

04 March 2024

Posted:

05 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Repeated Measures ANOVA

3.3. Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health(accessed on June 2023).

- De Schrijver, L.; Dierckens, M.; Deforche, B. Studie Jongeren en Gezondheid, Mentaal, sociaal en fysiek welzijn [Factsheet]; 2023.

- Panchal, U.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Franco, M.; Moreno, C.; Parellada, M.; Arango, C.; Fusar-Poli, P. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 1151–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samji, H.; Wu, J.; Ladak, A.; Vossen, C.; Stewart, E.; Dove, N.; Long, D.; Snell, G. Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth–a systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorisdottir, I.E.; Asgeirsdottir, B.B.; Kristjansson, A.L.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; Tolgyes, E.M.J.; Sigfusson, J.; Allegrante, J.P.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Halldorsdottir, T. Depressive symptoms, mental wellbeing, and substance use among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iceland: a longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayborne, Z.M.; Varin, M.; Colman, I. Systematic review and meta-analysis: adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erskine, H.E.; Norman, R.E.; Ferrari, A.J.; Chan, G.C.; Copeland, W.E.; Whiteford, H.A.; Scott, J.G. Long-term outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousteri, V.; Daly, M.; Delaney, L. Underemployment and psychological distress: Propensity score and fixed effects estimates from two large UK samples. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 244, 112641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; Korczak, D.J.; Vaillancourt, T.; Racine, N.; Hopkins, W.G.; Pador, P.; Hewitt, J.M.; AlMousawi, B.; McDonald, S.; Neville, R.D. Comparison of paediatric emergency department visits for attempted suicide, self-harm, and suicidal ideation before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rens, E.; Portzky, G.; Morrens, M.; Dom, G.; Van den Broeck, K.; Gijzen, M. An exploration of suicidal ideation and attempts, and care use and unmet need among suicide-ideators in a Belgian population study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz-Mette, R.A.; Duell, N.; Lawrence, H.R.; Balkind, E.G. COVID-19 distress impacts adolescents’ depressive symptoms, NSSI, and suicide risk in the rural, northeast US. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2023, 52, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijzen, M.; Portzky, G. De Vlaamse Suïcidecijfers in een nationale en internationale context. Available online: https://www.vlesp.be/assets/pdf/epidemiological-report-2022-in-dutch-en-103818.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Liu, R.T.; Walsh, R.F.; Sheehan, A.E.; Cheek, S.M.; Sanzari, C.M. Prevalence and correlates of suicide and nonsuicidal self-injury in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatandoost, S.; Baetens, I.; Erjaee, Z.; Azadfar, Z.; Van Heel, M.; Van Hove, L. A Comparative Analysis of Emotional Regulation and Maladaptive Symptoms in Adolescents: Insights from Iran and Belgium. Healthcare 2024, 12, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (ISSS), I.S.f.t.S.o.S.-i. What is self-injury? Available online: https://www.itriples.org/aboutnssi/what-is-self-injury%3F(accessed on).

- Brunner, R.; Kaess, M.; Parzer, P.; Fischer, G.; Carli, V.; Hoven, C.W.; Wasserman, C.; Sarchiapone, M.; Resch, F.; Apter, A. Life-time prevalence and psychosocial correlates of adolescent direct self-injurious behavior: A comparative study of findings in 11 European countries. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swannell, S.V.; Martin, G.E.; Page, A.; Hasking, P.; St John, N.J. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2014, 44, 273–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Li, G.; Chen, B.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, H.; Wu, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y. Prevalence of and risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury in rural China: results from a nationwide survey in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 226, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Q.; Song, X.; Huang, L.; Hou, D.; Huang, X. Global prevalence and characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury between 2010 and 2021 among a non-clinical sample of adolescents: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 912441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Xhunga, N.; Brausch, A.M. Self-injury age of onset: A risk factor for NSSI severity and suicidal behavior. Arch. Suicide Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, C.R.; Klonsky, E.D. Prospective prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury: A 1-year longitudinal study in young adults. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, T.; Martin, G.; Hasking, P.; Page, A. Predictors of continuation and cessation of nonsuicidal self-injury. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daukantaitė, D.; Lundh, L.-G.; Wångby-Lundh, M.; Claréus, B.; Bjärehed, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liljedahl, S.I. What happens to young adults who have engaged in self-injurious behavior as adolescents? A 10-year follow-up. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, P.O.; Qiu, T.; Neufeld, S.; Jones, P.B.; Goodyer, I.M. Sporadic and recurrent non-suicidal self-injury before age 14 and incident onset of psychiatric disorders by 17 years: prospective cohort study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 212, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrocas, A.L.; Giletta, M.; Hankin, B.L.; Prinstein, M.J.; Abela, J.R. Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: Longitudinal course, trajectories, and intrapersonal predictors. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 43, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggan, J.; Heath, N.; Hu, T. Non-suicidal self-injury maintenance and cessation among adolescents: a one-year longitudinal investigation of the role of objectified body consciousness, depression and emotion dysregulation. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2015, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Li, X.; Ng, C.H.; Xu, D.-W.; Hu, S.; Yuan, T.-F. Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents: A meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Bettis, A.H.; Watson, K.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Dunbar, J.P.; Williams, E.; Thigpen, J.C. Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 939. https://psycnet.apa.or. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- te Brinke, L.W.; Menting, A.T.; Schuiringa, H.D.; Zeman, J.; Deković, M. The structure of emotion regulation strategies in adolescence: Differential links to internalizing and externalizing problems. Soc. Dev. 2021, 30, 536–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Jomar, K.; Dhingra, K.; Forrester, R.; Shahmalak, U.; Dickson, J.M. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, J.C.; Thompson, E.; Thomas, S.A.; Nesi, J.; Bettis, A.H.; Ransford, B.; Scopelliti, K.; Frazier, E.A.; Liu, R.T. Emotion dysregulation and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 59, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, K.C.; Gross, J.J. Nonsuicidal self-injury: An emotion regulation perspective. Psychopathology 2014, 47, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiuolo, M.; Deane, F.P.; Ciarrochi, J. Parental authoritativeness, social support and help-seeking for mental health problems in adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracke, P.; Delaruelle, K.; Verhaeghe, M. Dominant cultural and personal stigma beliefs and the utilization of mental health services: A cross-national comparison. Front. Sociol. 2019, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Schauman, O.; Graham, T.; Maggioni, F.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Bezborodovs, N.; Morgan, C.; Rüsch, N.; Brown, J.S.; Thornicroft, G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Mahdy, J.C.; Ammerman, B.A. How others respond to non-suicidal self-injury disclosure: A systematic review. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 31, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, A.C.; Hamza, C.A. Examining the disclosure of nonsuicidal self-injury to informal and formal sources: A review of the literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 82, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lustig, S.; Koenig, J.; Resch, F.; Kaess, M. Help-seeking duration in adolescents with suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 140, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, S.L.; French, R.S.; Henderson, C.; Ougrin, D.; Slade, M.; Moran, P. Help-seeking behaviour and adolescent self-harm: a systematic review. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emqi, Z.H.; Hartini, N. Pathways to Get Help: Help-Seeking on College Students with Non-Suicidal Self-Injury. Edumaspul: J. Pendidik. 2022, 6, 2136–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre Velasco, A.; Cruz, I.S.S.; Billings, J.; Jimenez, M.; Rowe, S. What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasking, P.; Rees, C.S.; Martin, G.; Quigley, J. What happens when you tell someone you self-injure? The effects of disclosing NSSI to adults and peers. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, D.; Lakiang, T.; Kathuria, N.; Kumar, M.; Mehra, S.; Sharma, S. Mental health interventions among adolescents in India: a scoping review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuosmanen, T.; Clarke, A.M.; Barry, M.M. Promoting adolescents’ mental health and wellbeing: evidence synthesis. J. Public Ment. Health 2019, 18, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freţian, A.M.; Graf, P.; Kirchhoff, S.; Glinphratum, G.; Bollweg, T.M.; Sauzet, O.; Bauer, U. The long-term effectiveness of interventions addressing mental health literacy and stigma of mental illness in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 1604072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Driscoll, C.; Heary, C.; Hennessy, E.; McKeague, L. Explicit and implicit stigma towards peers with mental health problems in childhood and adolescence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, A.E.; Curtin, E.; Widnall, E.; Dodd, S.; Limmer, M.; Simmonds, R.; Kidger, J. Assessing the feasibility of a peer education project to improve mental health literacy in adolescents in the UK. Community Ment. Health J. 2023, 59, 784–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waqas, A.; Malik, S.; Fida, A.; Abbas, N.; Mian, N.; Miryala, S.; Amray, A.N.; Shah, Z.; Naveed, S. Interventions to reduce stigma related to mental illnesses in educational institutes: A systematic review. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šouláková, B.; Kasal, A.; Butzer, B.; Winkler, P. Meta-review on the effectiveness of classroom-based psychological interventions aimed at improving student mental health and well-being, and preventing mental illness. J. Prim. Prev. 2019, 40, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weare, K.; Nind, M. Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools: what does the evidence say? Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26, i29–i69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrell, K.; Carrizales-Engelmann, D.; Feuerborn, L.L.; Gueldner, B.A.; Tran, O.K. Strong Kids, Grades 6-8: A Social and Emotional Learning Curriculum (Strong Kids Curricula). 2007.

- Lee, A.; Gage, N.A. Updating and expanding systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effects of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports. Psychol. Sch. 2020, 57, 783–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M.; Russell, P.; Connelly, G. School-based interventions to enhance the resilience of students. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 4, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasijawa, F.A.; Siagian, I. School-based Interventions to Improve Adolescent Resilience: A Scoping Review. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.M.; Clarke, A.M.; Jenkins, R.; Patel, V. A systematic review of the effectiveness of mental health promotion interventions for young people in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkaert, B.; Wante, L.; Loeys, T.; Boelens, E.; Braet, C. The evaluation of Boost Camp: A universal school-based prevention program targeting adolescent emotion regulation skills. Sch. Ment. Health 2022, 14, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caria, M.P.; Faggiano, F.; Bellocco, R.; Galanti, M.R.; Group, E.-D.S. Effects of a school-based prevention program on European adolescents’ patterns of alcohol use. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 48, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, D.; Hoven, C.W.; Wasserman, C.; Wall, M.; Eisenberg, R.; Hadlaczky, G.; Kelleher, I.; Sarchiapone, M.; Apter, A.; Balazs, J. School-based suicide prevention programmes: the SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 1536–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrieri, S.; Heider, D.; Conrad, I.; Blume, A.; König, H.-H.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. School-based prevention programs for depression and anxiety in adolescence: A systematic review. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dray, J.; Bowman, J.; Campbell, E.; Freund, M.; Wolfenden, L.; Hodder, R.K.; McElwaine, K.; Tremain, D.; Bartlem, K.; Bailey, J. Systematic review of universal resilience-focused interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health in the school setting. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Zanden, R.; van der Linden, D. Evaluatieonderzoek Happyles Den Haag. Implementatie van Happyles in het VMBO en de Jeugdzorgketen ter bevordering van de mentale veerkracht van jongeren. Utrecht: Trimbos-instituut 2013.

- Tejada-Gallardo, C.; Blasco-Belled, A.; Torrelles-Nadal, C.; Alsinet, C. Effects of school-based multicomponent positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 1943–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, A.; Aprea, C.; Bellone, L.; Cotrufo, P.; Cella, S. Non-suicidal self-injury: a school-based peer education program for adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 737544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetens, I.; Decruy, C.; Vatandoost, S.; Vanderhaegen, B.; Kiekens, G. School-based prevention targeting non-suicidal self-injury: a pilot study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado-Rodríguez, I.D.; Casañas, R.; Mas-Expósito, L.; Castellví, P.; Roldan-Merino, J.F.; Casas, I.; Lalucat-Jo, L.; Fernández-San Martín, M.I. Effectiveness of mental health literacy programs in primary and secondary schools: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Children 2022, 9, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.; Lopez, S.J. Toward a science of mental health. Oxf. Handb. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 2, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Iasiello, M.; Van Agteren, J. Mental health and/or mental illness: A scoping review of the evidence and implications of the dual-continua model of mental health. Evid. Base: A J. Evid. Rev. Key Policy Areas 2020, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splett, J.W.; Fowler, J.; Weist, M.D.; McDaniel, H.; Dvorsky, M. The critical role of school psychology in the school mental health movement. Psychol. Sch. 2013, 50, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baetens, I.; Claes, L.; Onghena, P.; Grietens, H.; Van Leeuwen, K.; Pieters, C.; Wiersema, J.R.; Griffith, J.W. Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence: a longitudinal study of the relationship between NSSI, psychological distress and perceived parenting. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitlock, J.; Exner-Cortens, D.; Purington, A. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury–Assessment Tool. Psychol. Assess. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock, J.; Exner-Cortens, D.; Purington, A. Assessment of nonsuicidal self-injury: Development and initial validation of the Non-Suicidal Self-Injury–Assessment Tool (NSSI-AT). Psychol. Assess. 2014, 26, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, A.; Klonsky, E.D. Measurement of emotion dysregulation in adolescents. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, G.M.; Mosier, J.I.; Gawain Wells, M.; Atkin, Q.G.; Lambert, M.J.; Whoolery, M.; Latkowski, M. Tracking the influence of mental health treatment: The development of the Youth Outcome Questionnaire. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. Int. J. Theory Pract. 2001, 8, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, T.W.; Burlingame, G.M.; Walbridge, M.; Smith, J.; Crum, M.J. Outcome assessment for children and adolescents: psychometric validation of the youth outcome questionnaire 30.1 (Y-OQ®-30.1). Clin. Psychol. Psychother. Int. J. Theory Pract. 2005, 12, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.H.; Farina, A. Attitudes toward seeking professional psychologial help: A shortened form and considerations for research. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Elhai, J.D.; Schweinle, W.; Anderson, S.M. Reliability and validity of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale-short form. Psychiatry Res. 2008, 159, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divin, N.; Harper, P.; Curran, E.; Corry, D.; Leavey, G. Help-Seeking Measures and Their Use in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2018, 3, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatandoost, S.; Baetens, I.; Van Den Meersschaut, J.; Van Heel, M.; Van Hove, L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of non-suicidal self-injury; a comparison between Iran and Belgium. Clin. Med. Insights: Psychiatry 2023, 14, 11795573231206378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetterqvist, M.; Jonsson, L.S.; Landberg, Å.; Svedin, C.G. A potential increase in adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury during covid-19: A comparison of data from three different time points during 2011–2021. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 305, 114208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, G.; Cohen, Z.P.; Paulus, M.P.; Tsuchiyagaito, A.; Kirlic, N. Sustained increase in depression and anxiety among psychiatrically healthy adolescents during late stage COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Yuan, G.F.; Hall, B.J.; Zhao, L.; Jia, P. Chinese adolescents’ depression, anxiety, and family mutuality before and after COVID-19 lockdowns: Longitudinal cross-lagged relations. Fam. Relat. 2023, 72, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidhaye, R. Global priorities for improving access to mental health services for adolescents in the post-pandemic world. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 53, 101661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.H.; Hernandez, B.E.; Joshua, K.; Gill, D.; Bottiani, J.H. A scoping review of school-based prevention programs for indigenous students. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 34, 2783–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intervention group | Control group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dropped out % | Stayed in study |

Value | p | Dropped out % |

Stayed in study |

Value | p | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 42.9% | 48.4% | X2 (1.01) |

.604 | 55.6 | 45.2% | X2 (1.82) |

.177 |

| Female | 56.3% | 51.6% | 44.4 | 54.8% | ||||

| Other | 0.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0% | ||||

| Age (mean) | 13.21 | 13.16 | t (-0.72) |

.474 | 12.31 | 12.16 | t (-1.9) |

.059 |

| Total | Control | Intervention | Difference test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | t (df) | p | |

| Difficulties in Emotion regulation | 31.89 | 10.07 | 31.21 | 10.92 | 32.56 | 9.18 | 0.748 (122) | .456 |

| Depressive symptoms | 13.45 | 9.41 | 11.92 | .987 | 14.98 | 8.75 | 1.830 (122) | .070 |

| Mental well-being | 49.92 | 8.61 | 52.11 | 9.01 | 47.73 | 7.66 | -2.922 (122) | .004 |

| Internalizing and externalizing problems | 24.87 | 14.86 | 22.06 | 14.96 | 27.67 | 14.33 | 2.136 (122) | .035 |

| Help-seeking behavior | 30.69 | 5.66 | 31.87 | 4.69 | 29.52 | 6.31 | -2.358 (122) | .020 |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | p | ω2p | Power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

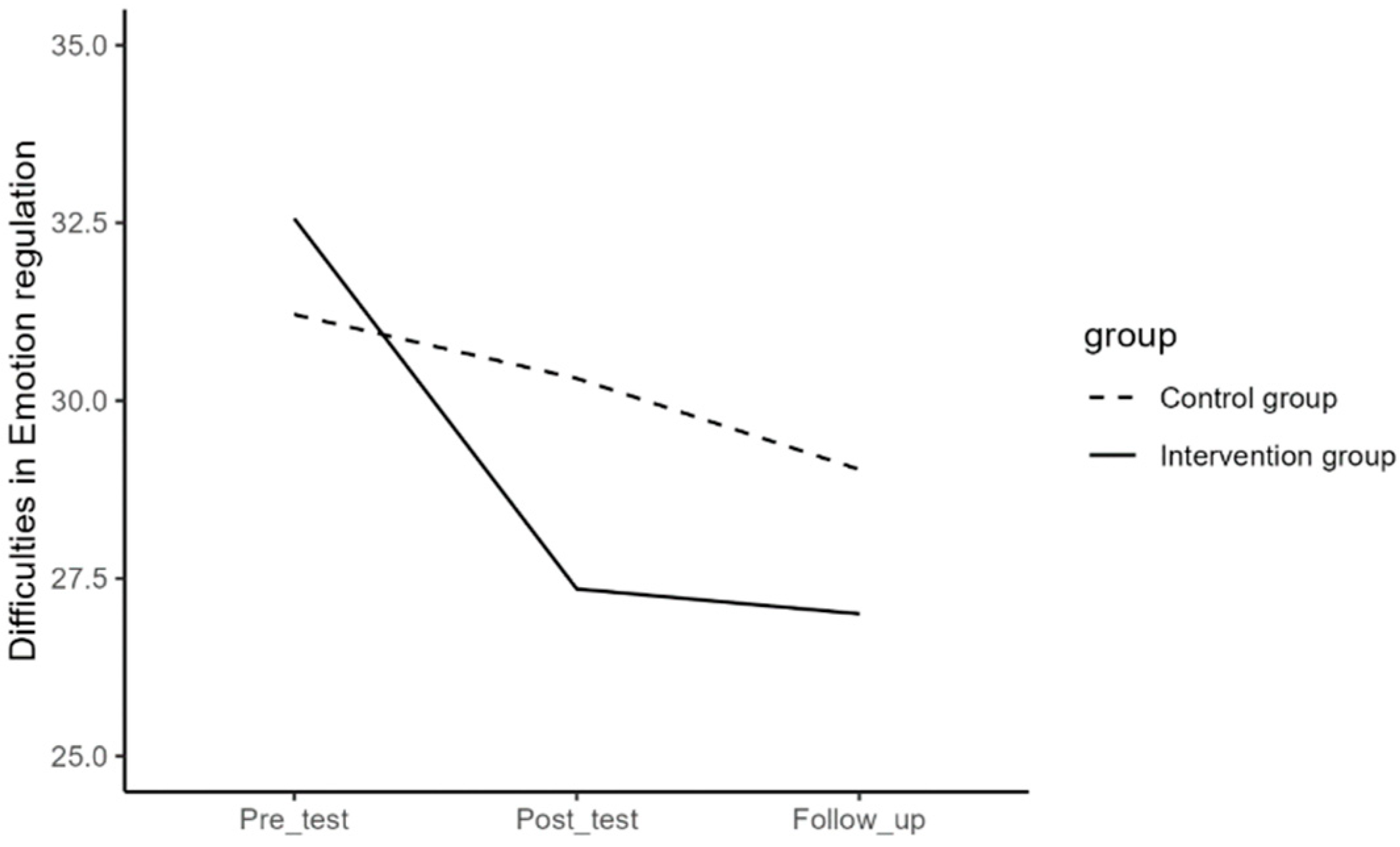

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation | Time | 1.032.909 | 2 | 516.454 | 23.55 | <.001 | 1 | |

| Time*Group | 318.919 | 2 | 159.46 | 7.27 | <.001 | 0.09 | .934 | |

| Error (Time) | 5.350.839 | 244 | 21.93 | |||||

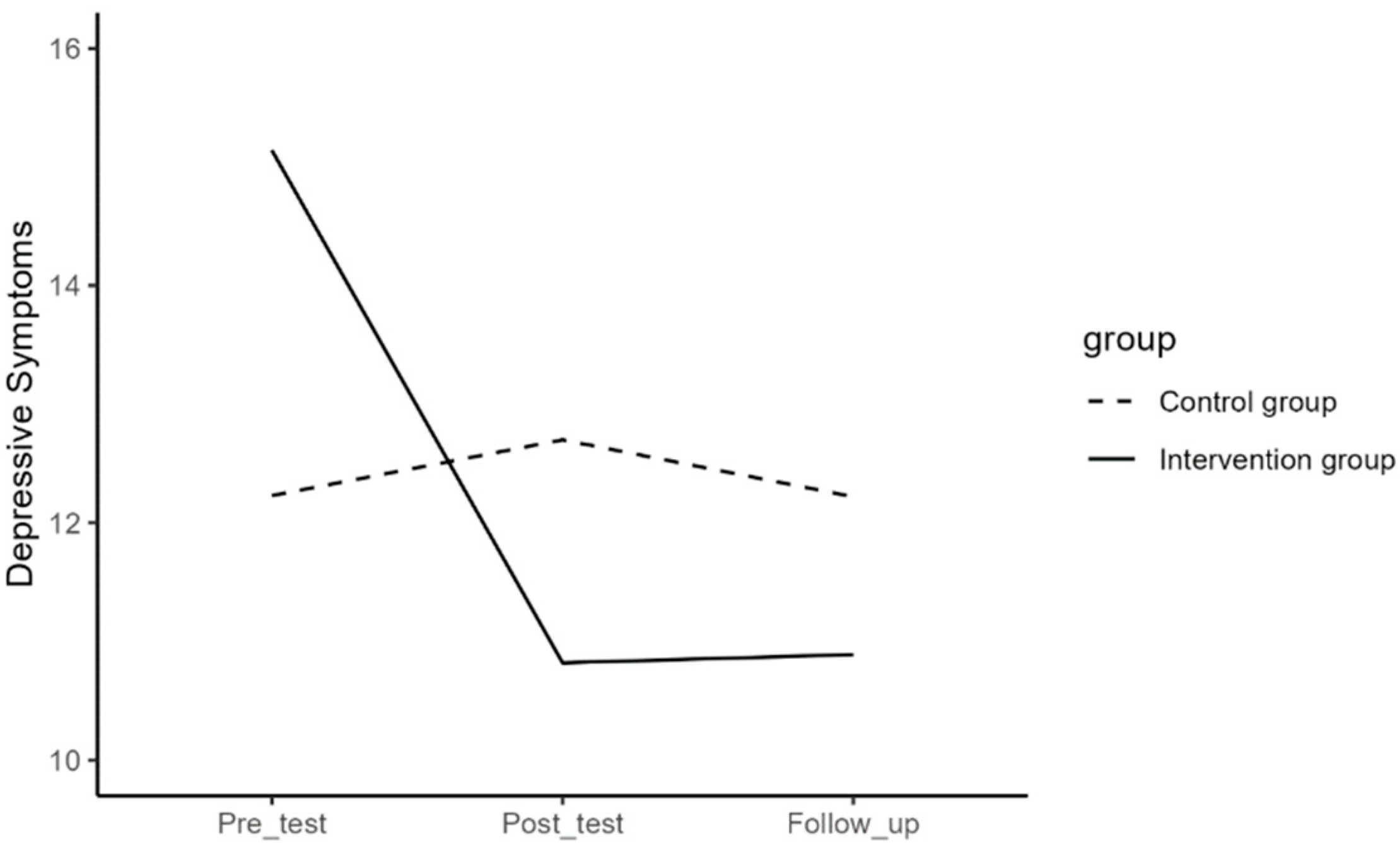

| Depressive symptoms | Time | 342.467 | 2 | 171.233 | 10.89 | <.001 | .990 | |

| Time*Group | 425.386 | 2 | 212.693 | 13.53 | <.001 | 0.17 | .998 | |

| Error (Time) | 3.836.978 | 244 | 15.725 | |||||

| Mental Well-being | Time | 204.016 | 2 | 102.008 | 5.33 | .005 | .836 | |

| Time*Group | 597.79 | 2 | 298.895 | 15.61 | <.001 | 0.19 | .999 | |

| Error (Time) | 4672.86 | 244 | 19.15 | |||||

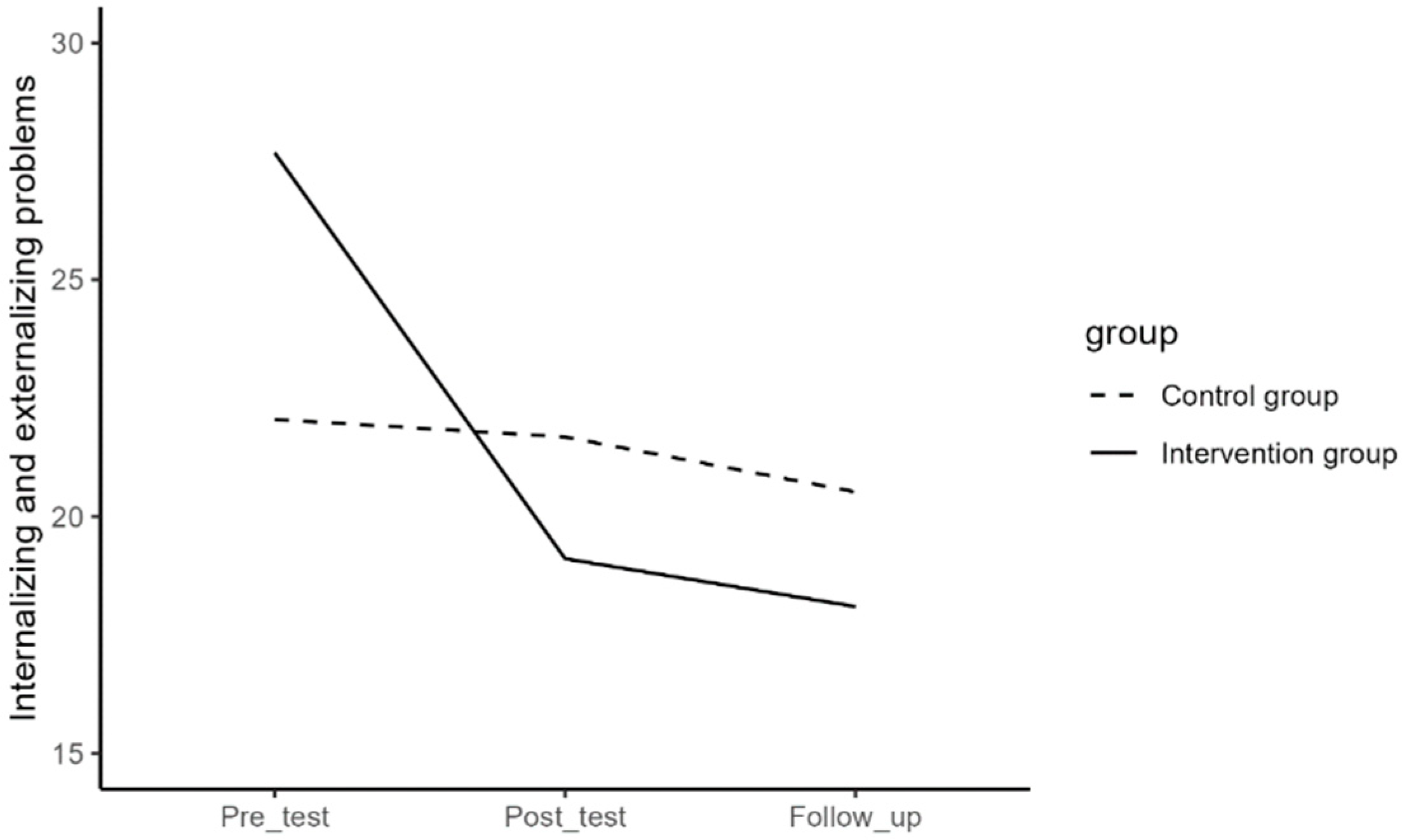

| Internalizing and Externalizing Problems | Time | 2.150.563 | 2 | 1075.28 | 27.5 | <.001 | 1 | |

| Time*Group | 1.362.646 | 2 | 681.323 | 17.42 | <.001 | 0.21 | 1 | |

| Error (Time) | 9.541.096 | 244 | 39.11 | |||||

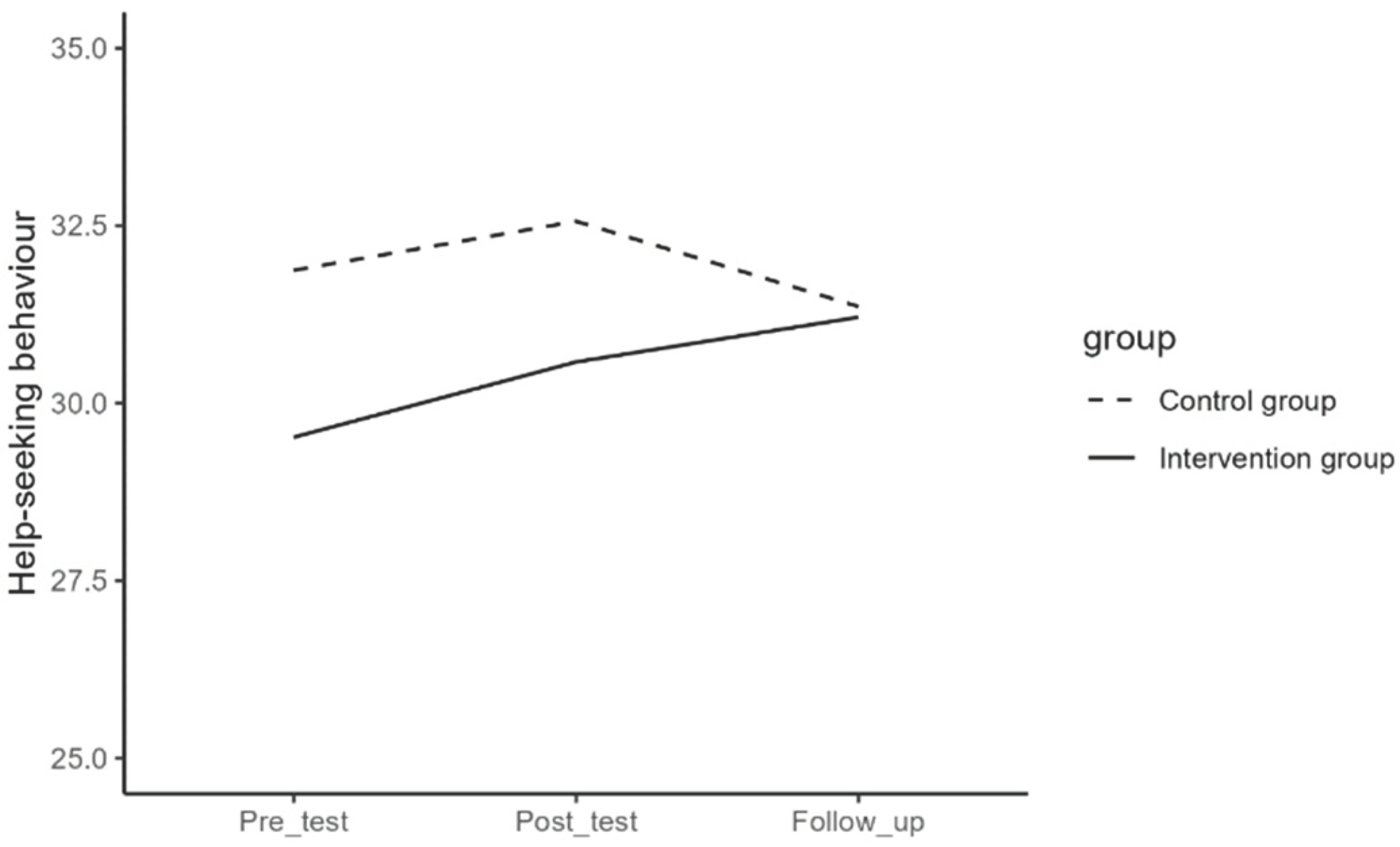

| Help-seeking Behavior | Time | 49.876 | 1.85 | 26.95 | 2.44 | .094 | .469 | |

| Time*Group | 86.992 | 1.85 | 47.013 | 4.26 | .018 | 0.05 | .716 | |

| Error (Time) | 2.492.825 | 225 | 11.043 |

| Intervention group (n=62) | Control group (n=62) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | Follow-up | Pre-test | Post-test | Follow-up | |

| Difficulties in Emotion regulation | 32.56 (9.18) | 27.35 (8.04) | 27 (9.34) | 31.21 (10.92) | 30.31 (11.82) | 29.03 (10.45) |

| Depressive symptoms | 15.14 (8.31) | 10.82 (7.64) | 10.89 (9.33) | 12.23 (9.54) | 12.7 (10.34) | 12.22 (10.26) |

| Mental well-being | 47.73 (7.65) | 51.73 (8.42) | 52.19 (9.52) | 52.11 (9.01) | 50.9 (9.21) | 51.05 (9.46) |

| Internalizing and externalizing problems | 27.68 (14.33) | 19.11 (13.26) | 18.1 (12.9) | 22.05 (14.96) | 21.68 (15.8) | 20.52 (15.32) |

| Help-seeking behavior | 29.52 (6.31) | 30.58 (6.44) | 31.21 (6.36) | 31.87 (3.74) | 32.56 (4.9) | 31.36 (4.94) |

| Time (I) | Time (J) | Mean Differences (I-J) | SE | p | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation | 1 | 2 | 5.21 | 0.69 | <.001 | 3.50 | 6.92 |

| 3 | 5.56 | 1.01 | <.001 | 3.07 | 8.06 | ||

| 2 | 1 | -5.21 | 0.69 | <.001 | -6.92 | -3.50 | |

| 3 | 0.35 | 0.90 | 1.000 | -1.87 | 2.58 | ||

| 3 | 1 | -5.56 | 1.01 | <.001 | -8.06 | -3.07 | |

| 2 | -0.35 | 0.90 | 1.000 | -2.58 | 1.87 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | 1 | 2 | 4.32 | 0.64 | <.001 | 2.75 | 5.89 |

| 3 | 4.25 | 0.89 | <.001 | 2.07 | 6.43 | ||

| 2 | 1 | -4.32 | 0.64 | <.001 | -5.89 | -2.75 | |

| 3 | -0.07 | 0.74 | 1.000 | -1.89 | 1.74 | ||

| 3 | 1 | -4.25 | 0.89 | <.001 | -6.43 | -2.07 | |

| 2 | 0.07 | 0.74 | 1.000 | -1.74 | 1.89 | ||

| Mental Well-being | 1 | 2 | -4 | 0.81 | <.001 | -6.00 | -2.00 |

| 3 | -4.47 | 0.93 | <.001 | -6.76 | -2.17 | ||

| 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.81 | <.001 | 2.00 | 6.00 | |

| 3 | -0.47 | 0.88 | 1.000 | -2.62 | 1.69 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 4.47 | 0.93 | <.001 | 2.17 | 6.76 | |

| 2 | 0.47 | 0.88 | 1.000 | -1.69 | 2.62 | ||

| Internalizing and Externalizing Problems | 1 | 2 | 8.56 | 1.38 | <.001 | 5.18 | 11.95 |

| 3 | 9.58 | 1.39 | <.001 | 6.15 | 13.01 | ||

| 2 | 1 | -8.56 | 1.38 | <.001 | -11.95 | -5.18 | |

| 3 | 1.02 | 1.21 | 1.000 | -1.96 | 3.99 | ||

| 3 | 1 | -9.58 | 1.39 | <.001 | -13.01 | -6.15 | |

| 2 | -1.02 | 1.21 | 1.000 | -3.99 | 1.96 | ||

| Help-seeking Behavior | 1 | 2 | -1.06 | 0.53 | .150 | -2.37 | 0.25 |

| 3 | -1.7 | 0.63 | .026 | -3.24 | -0.16 | ||

| 2 | 1 | 1.06 | 0.53 | .150 | -0.25 | 2.37 | |

| 3 | -0.63 | 0.66 | 1.000 | -2.26 | 0.99 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 1.7 | 0.63 | .026 | 0.16 | 3.24 | |

| 2 | 0.635 | 0.66 | 1.000 | -0.99 | 2.26 |

| Time (I) | Time (J) | Mean Differences (I-J) | SE | p | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation | 1 | 2 | 0.9 | 0.81 | .805 | -1.09 | 2.89 |

| 3 | 2.18 | 0.76 | .017 | 0.31 | 4.04 | ||

| 2 | 1 | -0.9 | 0.81 | .805 | -2.89 | 1.09 | |

| 3 | 1.27 | 0.83 | .388 | -0.77 | 3.31 | ||

| 3 | 1 | -2.18 | 0.76 | .017 | -4.04 | -0.31 | |

| 2 | -1.27 | 0.83 | .388 | -3.31 | 0.77 |

| Intervention- Control |

Mean difference |

SE | p | Lower bound |

Upper bound |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulties in emotion regulation |

Pre/Post | -4.31 | 1.07 | <.001 | -6.42 | -2.20 |

| Post/Follow-up | 0.92 | 1.23 | .455 | -1.50 | 3.35 | |

| Pre/Follow-up | 3.39 | 1.27 | .009 | .88 | 5.89 | |

| Depressive symptoms | Pre/Post | -4.79 | 0.98 | <.001 | -6.72 | -2.86 |

| Post/Follow-up | 0.55 | 0.96 | .563 | -1.34 | 2.45 | |

| Pre/Follow-up | 4.23 | 1.08 | <.001 | 2.08 | 6.38 | |

| Mental well-being | Pre/Post | 5.21 | 1.02 | <.001 | 3.19 | 7.24 |

| Post/Follow-up | 0.32 | 1.18 | .785 | -2.01 | 2.66 | |

| Pre/Follow-up | -5.53 | 1.12 | <.001 | -7.76 | -3.30 | |

| Internalizing/ Externalizing problems |

Pre/Post | -8.19 | 1.68 | <.001 | -11.52 | -4.87 |

| Post/Follow-up | .15 | 1.50 | .922 | -2.83 | 3.12 | |

| Pre/Follow-up | 8.04 | 1.58 | <.001 | 4.91 | 11.18 | |

| Help seeking behavior | Pre/Post | .37 | 0.69 | .591 | -0.99 | 1.73 |

| Post/Follow-up | 1.84 | 0.86 | .034 | 0.15 | 3.54 | |

| Pre/Follow-up | -2.21 | .88 | .013 | -3.95 | -.47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).