1. Introduction

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) is a comprehensive framework for assessing health status, encompassing body function, structure, activity, and participation, as well as the environmental and individual factors influencing these elements. In addition to offering an exhaustive set of categories for human functioning, it incorporates qualifiers that function as scale systems to delineate the severity of problems. However, despite their design for use in international statistics, the actual implementation of ICF in real-world settings has encountered substantial obstacles. Key challenges in this implementation include the vast number of categories, the intricate nature of category definitions, and the inconsistent reliability of ratings. Efforts to overcome these barriers have involved the development of disease-specific core sets, simplification of item definitions, and provision of reference guides for assessment [

1,

2,

3].

In clinical practice, the assessment of functioning information often relies on a variety established assessment scales, such as the Barthel Index [

4] and the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) [

5], which are commonly used to evaluate Activities of Daily Living (ADL), as well as disease specific scales such as the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) for stroke patients [

6]. While there have been significant efforts to adapt the ICF for clinical practice, the complete replacement of existing, widely-used scales with the ICF remains a significant challenge considering their established utility. In this regard, linking of the data from existing scales to the ICF may be an alternative solution. In this context, Cieza et al. proposed a 'linking rule' to integrate data from existing scales into the ICF framework [

7,

8,

9]. This approach, which has seen numerous applications [

10,

11], suggests the potential of consolidating information from various clinical scales into the ICF, thus enhancing its utility in functional statistics. However, a standardized method for incorporating scores from existing clinical scales into the ICF has not yet been established.

To address this gap and explore a novel approach to solving the issue, we have developed a conversion table that translates clinical scale scores into ICF Qualifiers, using clinician surveys as the foundation and beginning with the FIM as an initial step. Our survey solicited insights from rehabilitation professionals into aligning FIM rating options with ICF Qualifiers. This effort represents a significant step towards harmonizing traditional clinical assessment systems with the ICF framework, which comprehensively classifies human functioning in daily living activities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Rehabilitation professionals, including rehabilitation physicians (MD), physical therapists (PT), occupational therapists (OT), speech therapists (ST, and social workers (SW) from seven hospitals in Japan were invited to participate in this survey.

2.2. Item linking table

The item-linking table between the FIM and ICF was developed by the ICF Implementation Working Group (set 2019-2021), established under the Functional Classification Expert Committee as part of the Statistics Subcommittee of the Social Security Council of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Annex 1). The consensus process involved three steps. First, four clinical experts familiar with the ICF were asked to link FIM items and ICF entities. The experts were then asked to refer to linking rules [

7,

8,

9], and to follow the additional rules to simplify the subsequent scale-linking process: 1) the scale items should be linked to one major entity that is most relevant, and 2) the entity linked should be a second-level category, instead of third or fourth entities, if possible. Based on the linking results, the experts discussed forming a consensus if there was a disagreement. The linking table was then finalized, as shown in Annex 1.

2.3. Survey for linking scores and qualifiers

A survey was conducted using a questionnaire asking whether a score of 1-7 on the FIM items would fall into the ICF 0-4 qualifiers.

To avoid excessive complexity with varied score-linking results, the items were grouped based on the chapters of the linked ICF categories, which are b1 mental functions, b5 functions of the digestive, metabolic, and endocrine systems, b6 genitourinary and reproductive functions, d1 learning and applying knowledge, d3 communication, d4 mobility, b5 self-care, and d7 interpersonal interactions and relationships. Then, items "Sphincter control" including bladder and bowel control belonging Chapters b5 and b6 grouped into one, as these are with very similar rating standards. Finally, a survey was conducted on seven groups of FIM items.

2.4. Analysis

Median and mean values were calculated for each FIM score.

3. Results

A total of 458 individuals (Age 31.1±8.0, 252 male) participated in the study, including 4 physicians, 225 physical therapists, 166 occupational therapists, 62 speech-language pathologists, and one social worker.

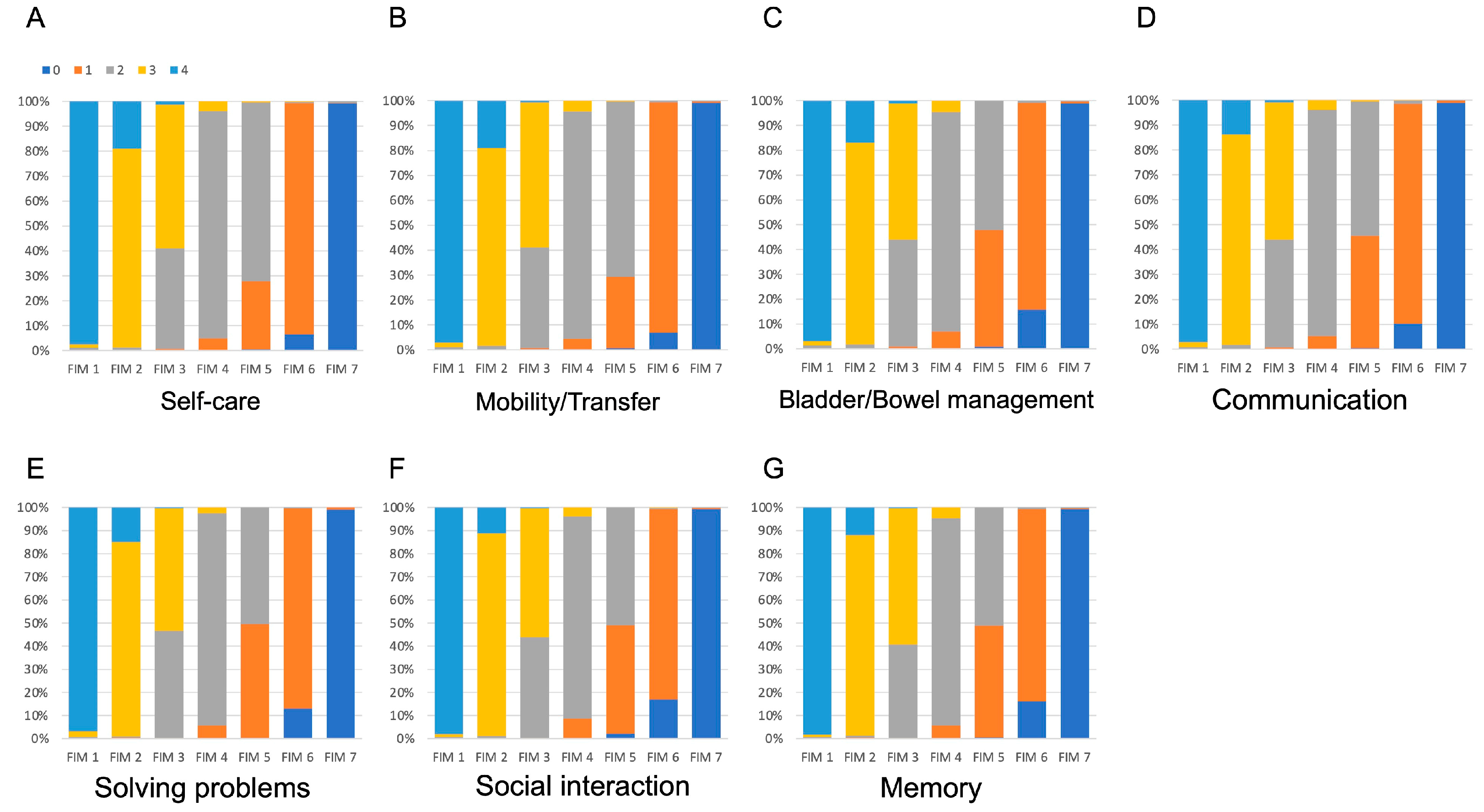

The ratios of answers are shown in

Figure 1 and

Table 1. In the survey, the most common responses regarding the equivalent International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) qualifiers for each option of the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) were as follows: for the self-care items, 97.6% indicated that FIM 1 is equivalent to ICF 4; 79.1% stated that FIM 2 corresponds to ICF 3; 57.6% reported FIM 3 as equal to ICF 3; 91.3% equated FIM 4 with ICF 2; 71.8% aligned FIM 5 with ICF 2; 92.8% compared FIM 6 to ICF 1; and 99.1% associated FIM 7 with ICF 0.

The median values for each item were consistent across all item groups as follows: FIM 1 corresponded to ICF 4, FIM 2 and 3 were equivalent to ICF 3, FIM 4 and 5 matched ICF 2, FIM 6 aligned with ICF 1, and FIM 7 was equal to ICF 0. When considering the average ICF values for each FIM score (FIM 1–7), a slight variation was found between items. For example, the average ICF value for FIM 5 was 1.7 in both 'Self-Care' and 'Mobility/Transfer', whereas it was 1.5 in 'Bladder/Bowel Management', 'Communication, 'Solving Problems,’ ‘Social Interaction,’ and 'Memory. ’ The detailed values are listed in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

In this study, we conducted a survey of 458 clinical experts to explore their perspectives on the interrelationships between FIM items and ICF qualifiers. The survey covered FIM items related to self-care, mobility/transfer, voiding control, communication, problem-solving, social interaction, and memory. Despite some variation in responses, the median ICF qualifier remained homogenous across different items, yielding the following translations of ICF qualifiers: 4 for FIM 1, 3 for FIMs 2 and 3, 2 for FIMs 4 and 5, 1 for FIM 6, and 0 for FIM 7.

The response distribution for FIM 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7 showed a high level of agreement among over three-quarters of the participants. In contrast, FIM 3 and 5 elicited a wider range of responses. Specifically, for FIM 3, the majority, ranging from 53.0% to 58.8%, believed that it merited a score of 3 in the ICF, whereas 40.4% to 46.3% felt that it deserved a score of 2. Regarding FIM 5, 50.5% to 71.8% of the respondents assigned a score of 2 in the ICF, while 27.3% to 49.3% considered a score of 1 to be more appropriate. The inequality of rating standards in their definitions may have affected this variation. For example, in the FIM, a score of 4 represents mild problems or the subjects expends 50–74% of effort [

5], while the qualifier of 3 in ICF, which was most frequent answer equivalent to FIM 4, is defined in the Annex 2 coding guideline of ICF [

12] as a "moderate problem (50-95%)". Additionally, the scope of the items under consideration could influence the level of agreement. For example, when evaluating the task of dressing, the FIM focuses primarily on basic actions like "taking off" and "putting on," without considering the degree of assistance required for preparing and storing clothes. In contrast, the ICF's definition of dressing encompasses broader aspects, including the choice of clothing appropriate for different situations. These differences in the definitions of rating standards and the scope of the items could account for the observed variation in responses to FIM 3. Further, the score of 5 in FIM, signifying supervision [

5], predominantly equated to a score of 2 in the ICF Qualifiers, which indicates a moderate problem with “up to half of the scale of total difficulty” [

12]. However, it remains notable that, in some item groups, nearly half of the participants considered this equivalent to 1 in the ICF Qualifiers, defined "5 to 24%" of the problem, which may depend on how difficult it is for the patient to conduct daily activities under supervision. An activity performed under supervision may be considered a mild problem as it does not require manual assistance, while in some cases, it can be a significant problem as the individual need someone present when performing the given activity. While the rating in FIM is focused on independence in the activity, the ICF aims to integrate broader aspects of patients’ experiences in capturing functioning problems, and this difference in concept might also affect the variety in responses of the participants.

While responses exhibited some variability, the process of abstracting functional information from existing scales and aligning it with the common framework of the ICF offers significant merit. Currently, several clinical rating scales are strongly linked to social institutions and are widely used. However, in terms of international statistics, the diversity of these clinical scales makes it difficult to achieve comparability between assessments. While several studies have investigated the relationships between functioning rating scales [

13,

14,

15], they have frequently concentrated on a restricted set of scales, such as the FIM, BI, and modified Rankin Scale (mRS), for comparison. Furthermore, these comparisons were typically based on the total scores of the scales rather than on item-by-item analysis. Although these studies are valuable for facilitating comparisons of functioning information across different contexts, they are insufficient to provide a comprehensive comparison of functioning information in clinical contexts, where a broader spectrum of clinical scales are used. The ICF, which encompasses a comprehensive classification framework for functioning, including ADL, could potentially serve as a central hub for integrating clinical information, including clinical scales. Indeed, numerous studies have been conducted to link items from clinical scales to the ICF; however, a consensus on how to accurately reflect the severity of problems measured by these scales in the ICF framework remains elusive. This study offers a potential solution to this challenge. The methodology proposed here, which involves the development of a conversion table based on surveys of clinicians' interpretations, may provide a viable solution to this issue. For example, the median ICF score for FIM 1 was 4, for FIM 2 and 3 it was 3, for FIM 4 and 5 it was 2, for FIM 6 it was 1, and for FIM 7 it was 0. Thus, this system allows the interrelationship between FIM and ICF to be expressed concisely. We believe that this survey method is also useful for studying the conversion of other life function assessments to the ICF as a central hub for integrating a large amount of clinical data for use in international statistics.

The methodology suggested in this study, which involves the creation of a conversion table derived from clinician survey interpretations, could offer a practical solution to the issue of integrating clinical scales with the ICF. To illustrate this, the median ICF scores were identified as follows: 4 for FIM 1 and 3 for FIMs 2 and 3, 2 for FIMs 4 and 5, 1 for FIM 6, and 0 for FIM 7. This approach allows for a clear and concise depiction of the relationship between the FIM and ICF scores. Furthermore, we believe that this survey-based method has significant potential to facilitate the conversion of various life function assessments into an ICF framework. This could be instrumental in consolidating a vast array of clinical data for broader application in international statistics.

This study had several limitations. First, some of the items, such as "self-care," included multiple sub-items such as eating, dressing, and changing clothes, and the interrelationship between the FIM and ICF for each of these items was not investigated separately. This approach was adopted to simplify the survey, with the aim of attracting a larger number of participants. However, it is important to consider the level of rigor necessary for a survey to ensure its effectiveness and accuracy. Second, as previously mentioned, the FIM and ICF do not perfectly align in their rating standards and assessment scope. Consequently, the conversion table may not be suitable for individual data analyses. This method is more appropriate for large-scale studies, such as those based on population samples, in which broader trends and patterns are the focus. Finally, the conversion table based on the median values reduces the information from the FIM. Using averaged values may retain more granularity, but this approach may not be permissible for statistical purposes as the FIM is an ordinal scale. Therefore, additional research is required to identify practical methods for data conversion that may vary depending on the specific objectives of the analysis.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a survey was conducted to investigate rehabilitation clinicians’ interpretations of the relationship between the FIM and ICF Qualifier scores. Overall, the survey results revealed an interrelationship between FIM scores and ICF Qualifiers, leading to the development of a conversion table. Further investigation will be beneficial for uncovering practical methods for data conversion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.U., M.M., S.Y. and M.K.; methodology, S.U., M.M., S.Y. and M.K.; investigation, M.O., Y.O., M.K., T.S., K.A., S.M. and Y.M.; data curation, Y.O., M.K., T.S., K.A., S.M. and Y.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.U. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.O., S.Y., M.K., E.O., Y.O., M.K., T.S., K.A., S.M., Y.M. and H.T.; supervision, H.T. and M.M.; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by the Grants for Research on Health and Welfare, grant number 20AB1003. The APC was funded by 20AB1003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fujita Health University (protocol code HM20-528).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to the rehabilitation professionals from Hanakawa Hospital, Fujita Health University Hospital, Hokuto Social Medical Corporation Tokachi Rehabilitation Center, Sapporo Azabu Neurosurgical Hospital, Moriyama Memorial Hospital, and National Hospital Organization Hokkaido Medical Center for their participation in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| FIM |

|

ICF |

| Self-Care |

Eating |

d550:eating/ d560:drinking |

| Grooming |

d520:caring for body parts |

| Bathing |

d510:washing oneself |

| Dressing—upper |

d540:dressing

d540:dressing |

| Dressing—lower |

| Transfers |

Bed, chair, wheel chair |

d420:transferring oneself

d420:transferring oneself

d420:transferring oneself |

| |

Toilet |

| |

Tub, shower |

| Locomotion |

Walk/Wheelchair |

d450:walking/ d465:moving around using equipment |

| |

Stairs |

d451:going up and down stairs |

| Sphincter control |

Bladder |

b620:urination functions |

| Bowel |

b525:defecation functions |

| Communication |

Comprehension |

d310:communicating with-receiving-spoken messages/ d315:communicating with-receiving-nonverbal messages |

| Expression |

d330:speaking/ d335:producing nonverbal messages |

| Social cognition |

Problem solving |

d175:solving problems |

| Social interaction |

d710:basic interpersonal interactions |

| Memory |

b144:memory functions |

References

- Selb M, Escorpizo R, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G, Ustun B, Cieza A. A guide on how to develop an International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51(1):105-17.

- Prodinger B, Reinhardt JD, Selb M, Stucki G, Yan T, Zhang X, Li J. Towards system-wide implementation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in routine practice: Developing simple, intuitive descriptions of ICF categories in the ICF Generic and Rehabilitation Set. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(6):508-14. [CrossRef]

- Mukaino M, Prodinger B, Yamada S, Senju Y, Izumi SI, Sonoda S, et al. Supporting the clinical use of the ICF in Japan - development of the Japanese version of the simple, intuitive descriptions for the ICF Generic-30 set, its operationalization through a rating reference guide, and interrater reliability study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):66. [CrossRef]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61-5.

- Keith RA, Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Sherwin FS. The functional independence measure: a new tool for rehabilitation. Adv Clin Rehabil. 1987;1:6-18.

- Dewey HM, Donnan GA, Freeman EJ, Sharples CM, Macdonell RA, McNeil JJ, Thrift AG. Interrater reliability of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale: rating by neurologists and nurses in a community-based stroke incidence study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1999;9(6):323-7. [CrossRef]

- Cieza A, Brockow T, Ewert T, Amman E, Kollerits B, Chatterji S, et al. Linking health-status measurements to the international classification of functioning, disability and health. J Rehabil Med. 2002;34(5):205-10. [CrossRef]

- Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Ustun B, Stucki G. ICF linking rules: an update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(4):212-8. [CrossRef]

- Cieza A, Fayed N, Bickenbach J, Prodinger B. Refinements of the ICF Linking Rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(5):574-83. [CrossRef]

- Moriello C, Byrne K, Cieza A, Nash C, Stolee P, Mayo N. Mapping the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS-16) to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(2):102-6. [CrossRef]

- Fairbairn K, May K, Yang Y, Balasundar S, Hefford C, Abbott JH. Mapping Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS) items to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Phys Ther. 2012;92(2):310-7. [CrossRef]

- WHO. International classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. 1st ed. Geneva2001 2001.

- Kwon S, Hartzema AG, Duncan PW, Min-Lai S. Disability measures in stroke: relationship among the Barthel Index, the Functional Independence Measure, and the Modified Rankin Scale. Stroke. 2004;35(4):918-23. [CrossRef]

- Cioncoloni D, Piu P, Tassi R, Acampa M, Guideri F, Taddei S, et al. Relationship between the modified Rankin Scale and the Barthel Index in the process of functional recovery after stroke. NeuroRehabilitation. 2012;30(4):315-22. [CrossRef]

- Lee SY, Kim DY, Sohn MK, Lee J, Lee SG, Shin YI, et al. Determining the cut-off score for the Modified Barthel Index and the Modified Rankin Scale for assessment of functional independence and residual disability after stroke. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0226324. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).