Submitted:

06 March 2024

Posted:

08 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material Methods

Phylogenetic Analysis and Physicochemical Properties

Protein Structure Refinement and Assessment

Structure-based Pharmacophore Modelling

Library Preparation and Virtual Screening

Docking-based Screening of Hits

ADME and Toxicity Profile Analysis

Drug-likeness and Biological Activity Analysis

MD Simulations

Results and Discussion

Phylogenetic Analysis of Hemagglutinin Neuraminidase

Assessment of Refined HN Receptor

Pharmacophore-based Virtual Screening

Structure-based Molecular Docking of Top Hits

Post-Docking Analysis of Potential Hits

Analysis of Pharmacokinetic Properties

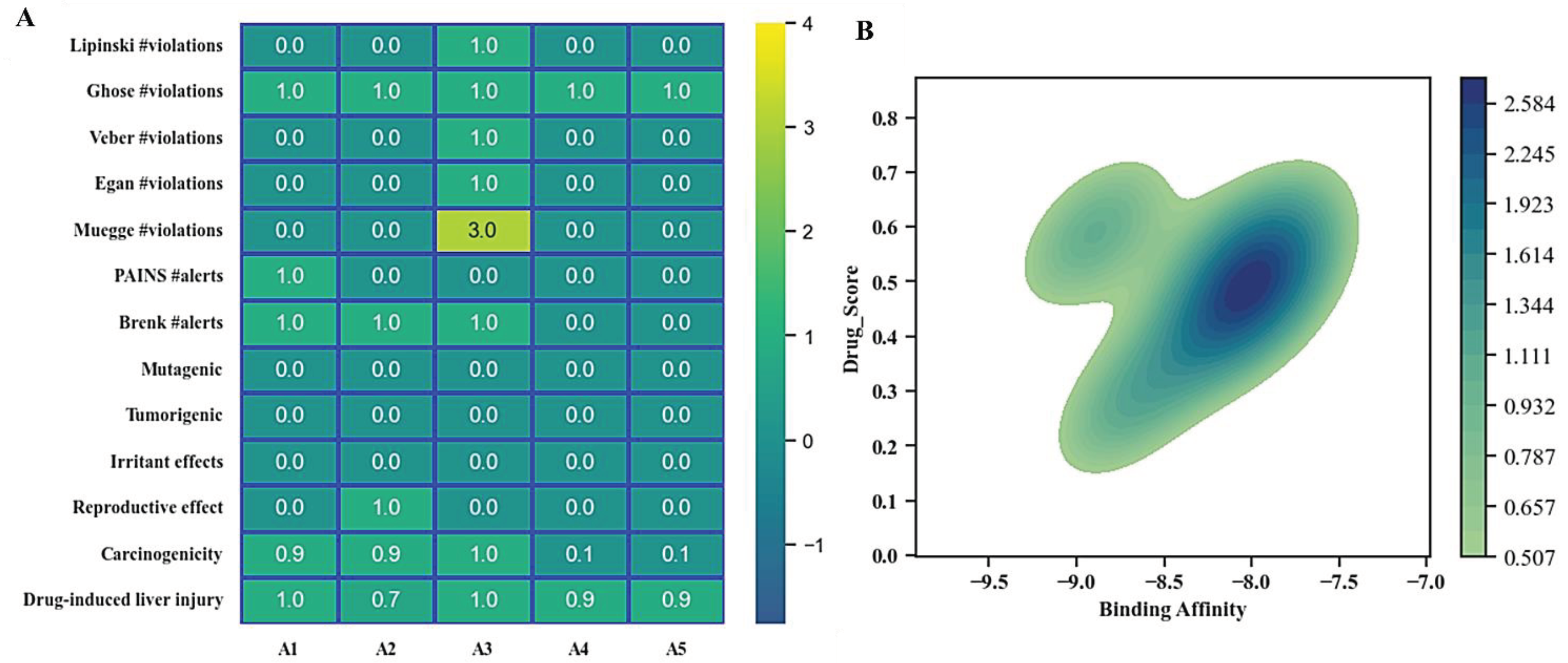

Toxicological Analysis of Top Hit Compounds

Biological Activity Prediction

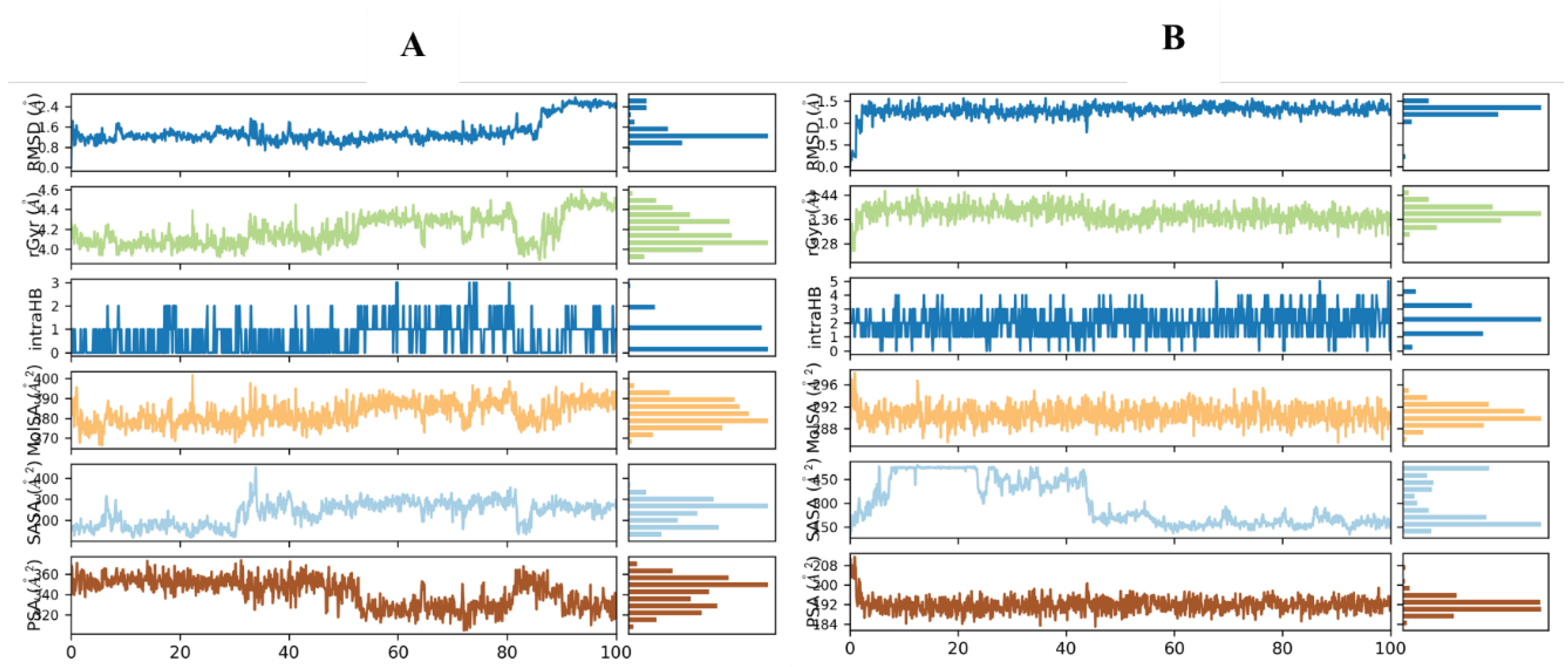

Molecular Dynamic Simulation

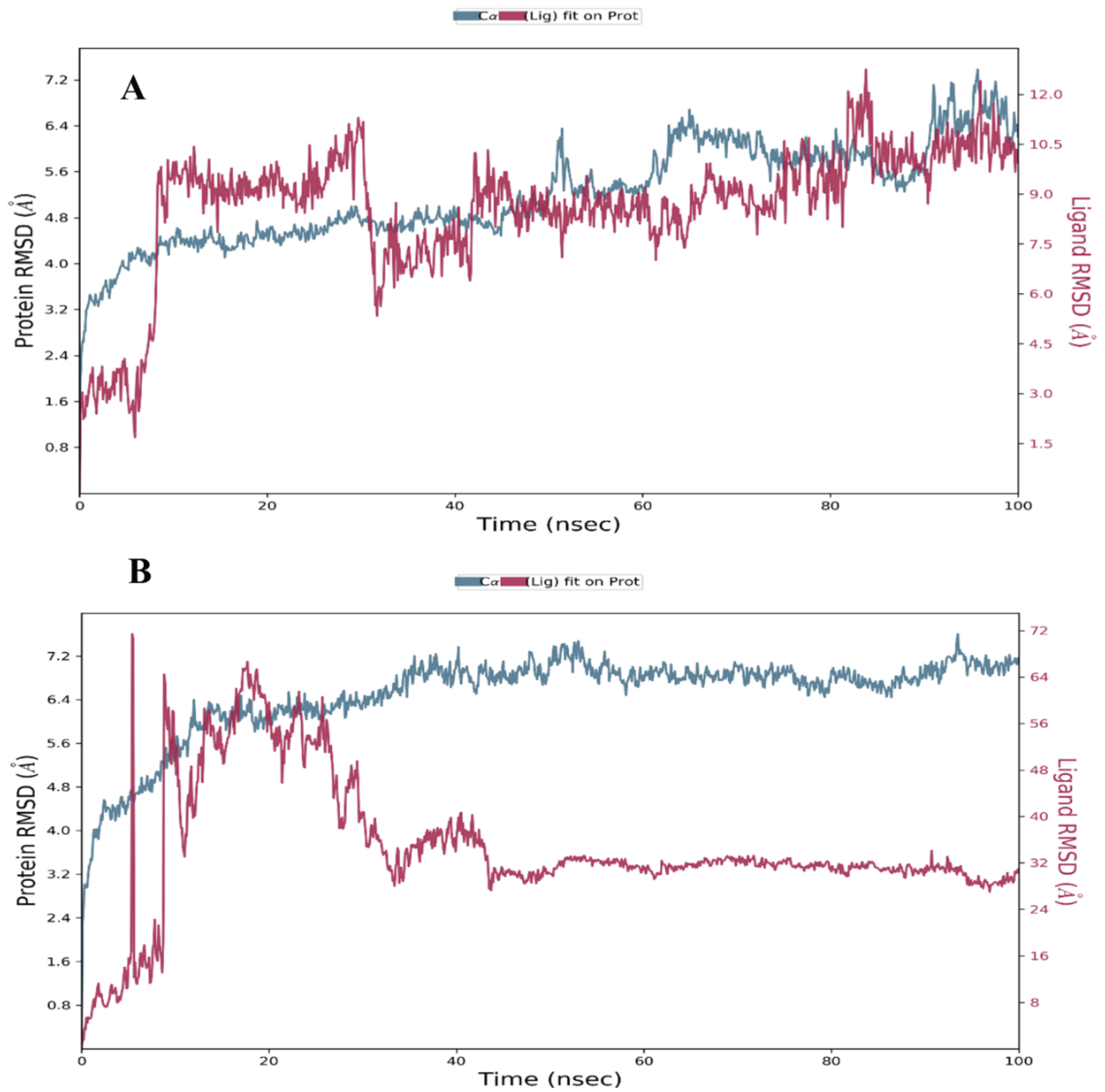

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD)

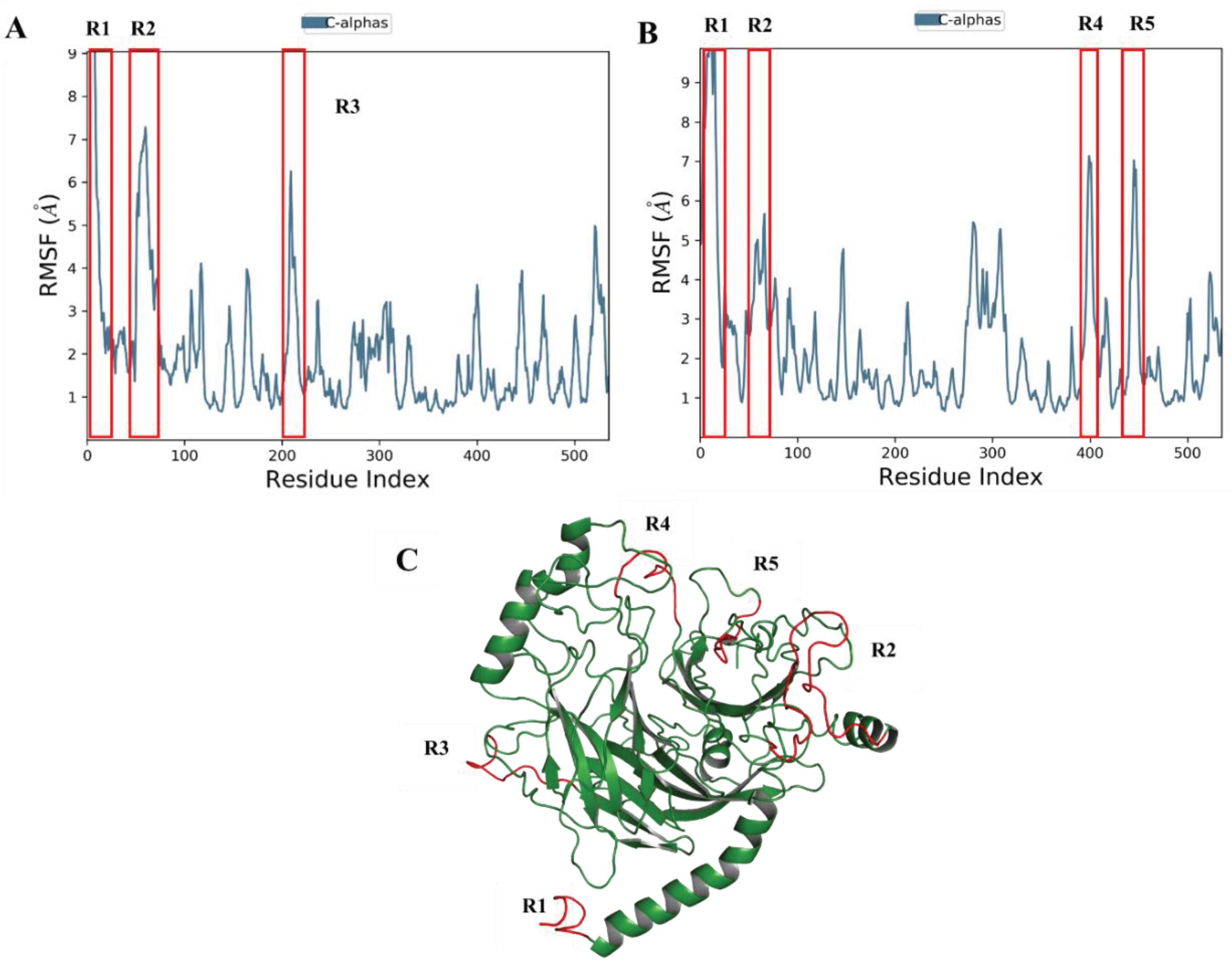

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF)

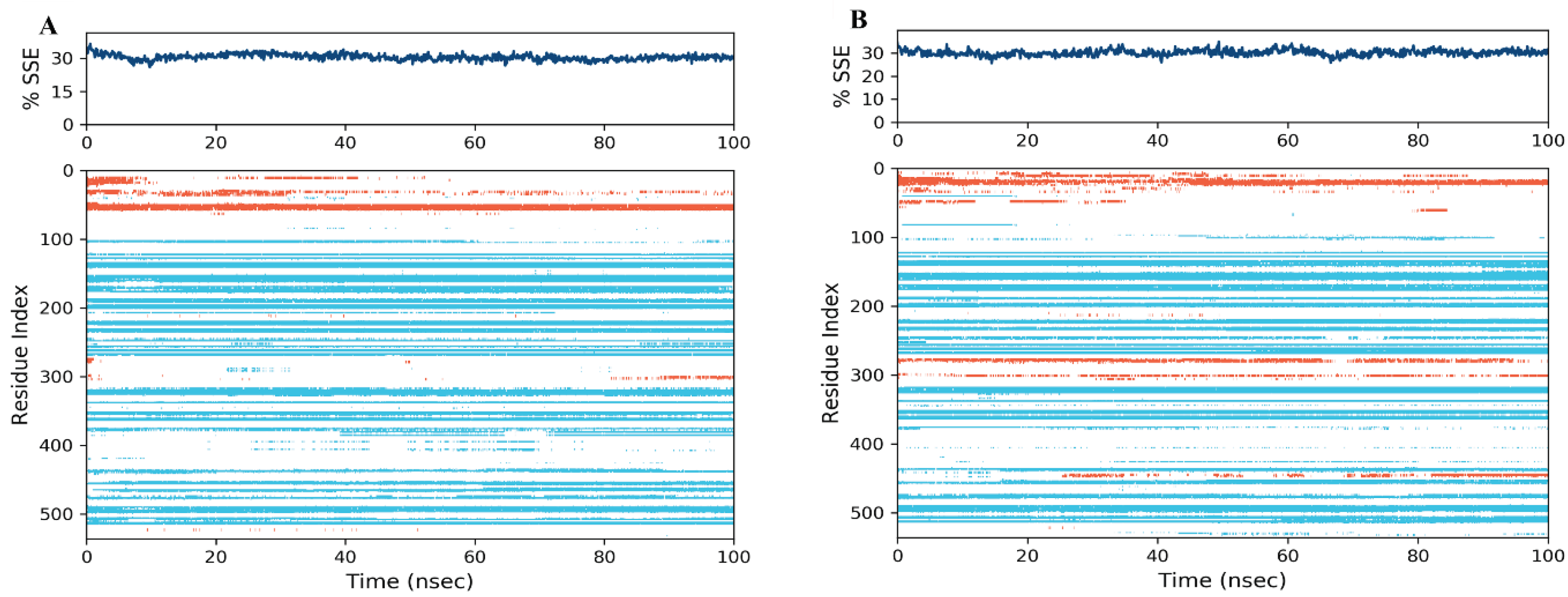

Secondary Structure Elements (SSE) Analysis

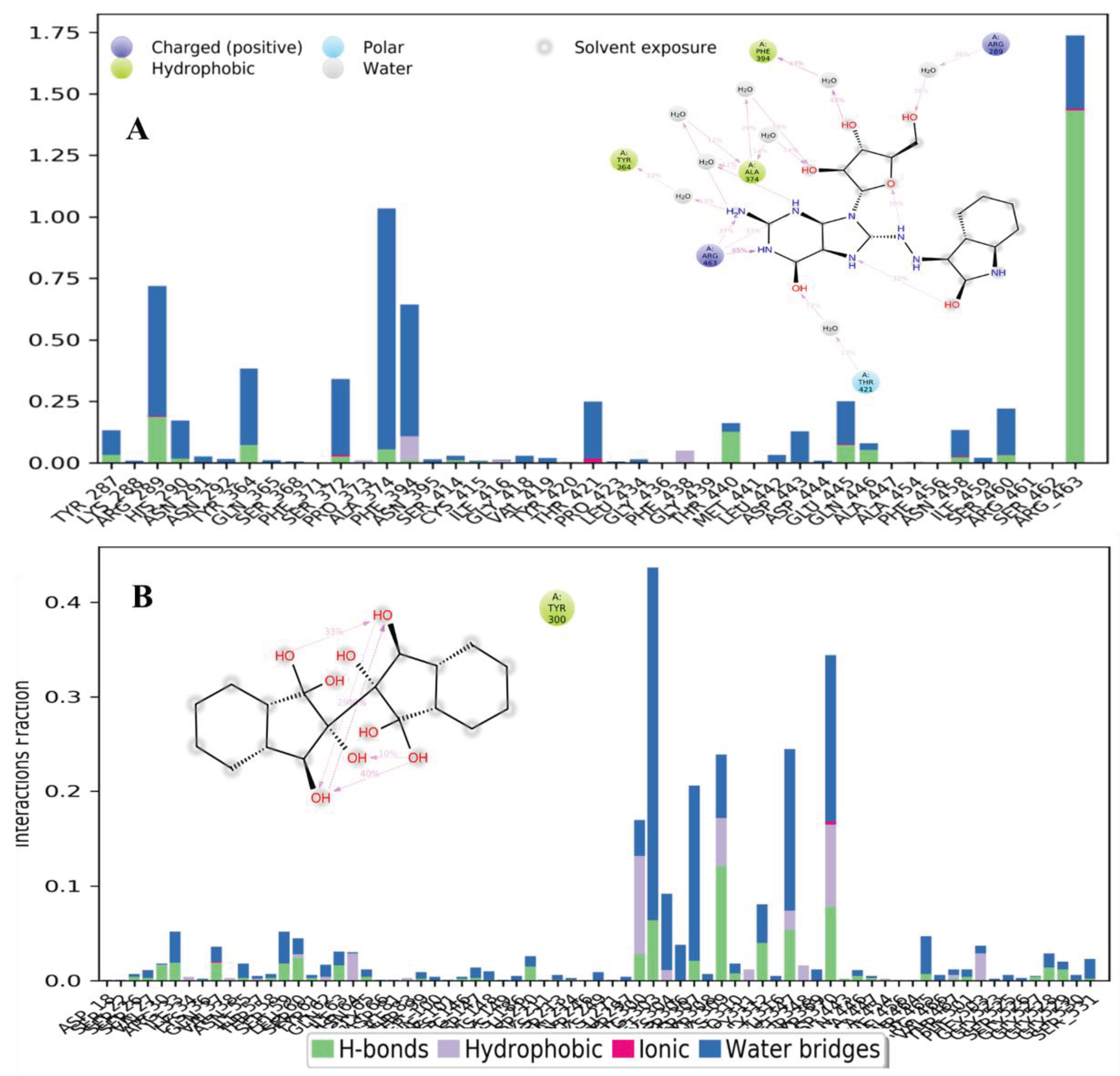

Protein-Ligand Interactions

Behavioral Properties of Potential Hit Compounds

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- D. R. Kapczynski, C. L. Afonso, and P. J. Miller, Immune responses of poultry to Newcastle disease virus. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2013, 41(3), 447–453. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Z. Duan et al., The nucleolar phosphoprotein B23 targets Newcastle disease virus matrix protein to the nucleoli and facilitates viral replication. Virology 2014, 452, 212–222. [CrossRef]

- C. S. Ross et al., JMM Profile: Avian paramyxovirus type-1 and Newcastle disease: a highly infectious vaccine-preventable viral disease of poultry with low zoonotic potential. J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 71(8), 1489. [CrossRef]

- L. Li et al., Peste Des Petits Ruminants Virus N Protein Is a Critical Proinflammation Factor That Promotes MyD88 and NLRP3 Complex Assembly. J. Virol. 2022, 96(10), e00309-22. [CrossRef]

- W. Sarwar et al., In Silico Analysis of Plant Flavonoids as Potential Inhibitors of Newcastle Disease Virus V Protein. Processes 2022, 10(5), 935. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Osman et al., In silico design of epitope based peptide vaccine against virulent strains of hn-newcastle disease virus (NDV) in poultry species. IJMCR Int. J. Multidiscip. Curr. Res. 2016, 4.

- V. Mayahi, M. Esmaelizad, and M. R. Ganjalikhany, Development of Avian avulavirus 1 epitope-based vaccine pattern based on epitope prediction and molecular docking analysis: an immunoinformatic approach. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2020, 26, 1513–1522. [CrossRef]

- M. Shafaati, M. Ghorbani, M. Mahmoodi, M. Ebadi, and R. Jalalirad, Expression and characterization of hemagglutinin–neuraminidase protein from Newcastle disease virus in Bacillus subtilis WB800. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20(1), 77. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Lamb, Paramyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication. Fields Virol. 2001, 1305–1340.

- C. Ryan et al., Structural analysis of a designed inhibitor complexed with the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase of Newcastle disease virus. Glycoconj. J. 2006, 23, 135–141. [CrossRef]

- M. Rahmani, A. Mozafari, M. Jafari, and A. H. Salmanian, The heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit bio-adjuvant linked to Newcastle disease virus recombinant hemagglutinin neuraminidase elicited a humoral immune response in animal model. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2023, 69(10), 94–99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. M. Badawi et al., Immunoinformatics predication and in silico modeling of epitope-based peptide vaccine against virulent Newcastle disease viruses. Am J Infect Dis Microbiol 2016, 4(3), 61–71. [CrossRef]

- Raza, M. A. Rasheed, S. Raza, M. T. Navid, A. Afzal, and F. Jamil, Prediction and analysis of multi epitope based vaccine against Newcastle disease virus based on haemagglutinin neuraminidase protein. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29(4), 3006–3014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. M. Dimitrov, C. L. Afonso, Q. Yu, and P. J. Miller, Newcastle disease vaccines—A solved problem or a continuous challenge? Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 206, 126–136. [CrossRef]

- E. Gasteiger, C. Hoogland, A. Gattiker, M. R. Wilkins, R. D. Appel, and A. Bairoch, Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server proteomics. Protoc. Handb. 2005, 571–607. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Jayaswal, G. C. Sahoo, and P. Das, Rational Drug Designing Strategies and Inhibitor Optimization: Anthrax Lethal Toxin Factor. Int. J. Bioautomation 2012, 16(4), 239.

- C. Colovos and T. O. Yeates, Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci. 1993, 2(9), 1511–1519. [CrossRef]

- D. Eisenberg, R. Lüthy, and J. U. Bowie, VERIFY3D: assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. InMethods in enzymology 1997 Jan 1 (Vol. 277, pp. 396-404). Acad. Press. 10, s0076-6879. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Laskowski, M. W. MacArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton, PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993, 26(2), 283–291. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Rasheed et al., Identification of lead compounds against scm (Fms10) in enterococcus faecium using computer aided drug designing. Life 2021, 11(2). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali et al., Identification of Natural Lead Compounds against Hemagglutinin-Esterase Surface Glycoprotein in Human Coronaviruses Investigated via MD Simulation, Principal Component Analysis, Cross-Correlation, H-Bond Plot and MMGBSA. Biomedicines 2023, 11(3), 793. [CrossRef]

- J. Bowers et al., Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters. Proc. 2006 ACM/IEEE Conf. Supercomput. SC'06 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. Martínez-Archundia, T. G. Hernández Mojica, J. Correa-Basurto, S. Montaño, and A. Camacho-Molina, Molecular dynamics simulations reveal structural differences among wild-type NPC1 protein and its mutant forms. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 38(12), 3527–3532. [CrossRef]

- G. Madhavi Sastry, M. Adzhigirey, T. Day, R. Annabhimoju, and W. Sherman, Protein and ligand preparation: Parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J. Comput. Aided. Mol. Des. 2013, 27(3), 221–234. [CrossRef]

- D. Shivakumar, J. Williams, Y. Wu, W. Damm, J. Shelley, and W. Sherman, Prediction of absolute solvation free energies using molecular dynamics free energy perturbation and the opls force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6(5), 1509–1519. [CrossRef]

- D. Jayabal, S. Jayanthi, R. Thirumalaisamy, R. Karthika, and M. N. Iqbal, Comparative anti-Diabetic potential of phytocompounds from Dr. Duke’s phytochemical and ethnobotanical database and standard antidiabetic drugs against diabetes hyperglycemic target proteins: an in silico validation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Daina, O. Michielin, and V. Zoete, iLOGP: a simple, robust, and efficient description of n-octanol/water partition coefficient for drug design using the GB/SA approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54(12), 3284–3301. [CrossRef]

- Daina, O. Michielin, and V. Zoete, SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Reports 2017, 7(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. N. Iqbal, M. Ibrahim, I. U. Haq, W. B. Alonazi, and A. R. Siddiqi, Computational exploration of novel ROCK2 inhibitors for cardiovascular disease management; insights from high-throughput virtual screening, molecular docking, DFT and MD simulation. PLoS One 2023, 18(11), e0294511. [CrossRef]

- M. G. and D. K. Sunil Kumara, Iqra Alib, Faheem Abbasc, Anurag Ranad, Sadanand Pandeye, In-silico design, pharmacophore-based screening, and molecular docking studies reveal that benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids as novel EGFR inhibitors targeting lung cancer. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023. [CrossRef]

| Hits IDs | Binding Affinities (kcal/mol) | Interacting Residues | Type of Interactions | Vander Wall’s Interacting Residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC05223166 (A1) | -8.9 | Ser414, Ser372, Thr421, Thr440, Gln446, Asp443, Glu445, Val452, Ala454 |

Conventional H-bond, Attractive charge, Alkyl. | Arg463, Phe456, Asp444, Ala447, Arg448, Thr465, Ile416, Phe438 |

|

ZINC02596997 (A2) |

-8.7 | Thr440, Asp443, Thr465, Glu445, Ile416 | Conventional H-bond, Pi-anion, Alkyl. | Phe456, Ala454, Arg448, Ala447, Phe438, Asp444, Asp422, Gly439, Phe371, Thr421 |

| ZINC01700877 (A3) | -8 | Ala447, Asp443, Gln446, Arg448, Ala454 | Conventional H-bond, Alkyl. | Thr465, Val467, Leu449, Val452, Phe456, Thr440, Glu445 |

| ZINC04011865 (A4) | -8 | Ser369, Phe438, Thr421, Ala374, Pro423, Pro425 | Conventional H-bond, carbon-hydrogen bond, pi-pi stacked, pi-Alkyl. | Asp422, Gly367, Phe371, Tyr420, Ile416, Glu445 |

| ZINC04011866 (A5) | -8 | Phe438, Pro423, Pro425, Ala374 | pi-pi stacked, pi-Alkyl. | Ser372, Ile416, Gly367, Ser369, Tyr420, Tyr370, Asp422 |

| ZINC04348410 (A6) | -7.8 | Thr421, Phe438, Ile416, Ala374 | Conventional H-bond, carbon-hydrogen bond, pi-pi stacked, pi-sigma. | Glu445, Ser372, Arg463, Pro423, Pro425, Arg366, Gly367, Asp422, Ser368, Tyr370, Phe371 |

| ZINC04179503 (A7) | -7.7 | Phe371, Thr440, Gly439, Ile416 | Conventional H-bond, pi-Alkyl. | Ser372, Ser368, Ser369, Tyr370, Tyr420, Glu445, Thr421, Phe438, Asp422, Pro423, Pro425 |

| ZINC03956713 (A8) | -7.5 | Thr440, Thr421, Ile416, Ser372, Phe371 | Conventional H-bond, carbon-hydrogen bond, pi-Alkyl. | Tyr370, Ser369, Gly418, Tyr420, Val419, Gly367, Asp422, Pro423, Phe438, Ser372, Phe456, Arg463 |

| ZINC04185655 (A9) | -7.5 | Tyr370, Ser368, Thr440, Pro423, Thr421 | Conventional H-bond, carbon-hydrogen bond, Alkyl interactions. | Ala374, Asp422, Gly439, Phe438, Ser372, Ile416, Tyr420, Ser368, Gly367. |

| Molecule ID | (A1) | (A2) | (A3) | (A4) | (A5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical Properties | Formula | C18H18N8O6 | C16H18O8 | C18H14O8 | C15H21NO6 | C15H21NO6 |

| MW | 442.39 | 338.31 | 358.3 | 311.33 | 311.33 | |

| Aromatic heavy atoms | 15 | 10 | 12 | 6 | 6 | |

| Fraction Csp3 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.53 | 0.53 | |

| Rotatable bonds | 4 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 6 | |

| MR | 113.3 | 81.6 | 83.68 | 76.41 | 76.41 | |

| Lipophilicity | iLOGP | 0.28 | 0.9 | 1.07 | 1.21 | 1.43 |

| XLOGP3 | -1.45 | -0.78 | -2.11 | -0.7 | -0.7 | |

| WLOGP | -3 | -0.72 | -1.7 | -1 | -1 | |

| MLOGP | -1.49 | -0.72 | -0.76 | -0.92 | -0.92 | |

| Silicos-IT Log P | -1.83 | 0.26 | 0.48 | -0.25 | -0.25 | |

| Consensus LogP | -1.5 | -0.21 | -0.61 | -0.33 | -0.29 | |

| ESOL Log S | -1.75 | -1.56 | -1.01 | -1.14 | -1.14 | |

| Water Solubility | ESOL Solubility (mg/ml) | 7.83E+00 | 9.39E+00 | 3.52E+01 | 2.28E+01 | 2.28E+01 |

| ESOL Solubility (mol/l) | 1.77E-02 | 2.78E-02 | 9.82E-02 | 7.33E-02 | 7.33E-02 | |

| ESOL Class | Very soluble | Very soluble | Very soluble | Very soluble | Very soluble | |

| Ali Log S | -2.52 | -1.46 | -0.63 | -1.1 | -1.1 | |

| Ali Solubility (mg/ml) | 1.34E+00 | 1.16E+01 | 8.45E+01 | 2.48E+01 | 2.48E+01 | |

| Ali Solubility (mol/l) | 3.02E-03 | 3.44E-02 | 2.36E-01 | 7.98E-02 | 7.98E-02 | |

| Ali Class | Soluble | Very soluble | Very soluble | Very soluble | Very soluble | |

| Silicos-IT LogSw | -2.47 | -1.79 | -2.81 | -1.57 | -1.57 | |

| Silicos-IT Solubility (mg/ml) | 1.49E+00 | 5.51E+00 | 5.52E-01 | 8.38E+00 | 8.38E+00 | |

| Silicos-IT Solubility (mol/l) | 3.36E-03 | 1.63E-02 | 1.54E-03 | 2.69E-02 | 2.69E-02 | |

| Silicos-IT class | Soluble | Soluble | Soluble | Soluble | Soluble | |

| Pharmacokinetics | GI absorption | High | High | Low | High | High |

| HIA | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | |

| Caco-2 Permeability | 18.5693 | 8.97596 | 20.6733 | 11.4467 | 11.4466 | |

| MDCK Permeability | 3.1e-06 | 5.4e-05 | 0.00025 | 9.3e-05 | 7e-05 | |

| BBB penetration | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Compound | Possibility of being Activite (Pa) | Possibility of being Inactivite (Pi) | Biological Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.847 0.537 0.558 0.508 |

0.003 0.006 0.030 0.014 |

Antiviral (Poxvirus) Antiviral (Herpes) Antiviral (Picornavirus) Antiviral (Hepatitis B) |

| A2 | 0,670 0.537 0.492 0.364 |

0.012 0.010 0.008 0.011 |

Antifungal Antiviral (Influenza) Antitoxic Antibacterial |

| A3 | 0.470 0.507 0.446 0.325 |

0.010 0.047 0.022 0.018 |

Antiviral (Adenovirus) Antiviral (Picornavirus) Antibacterial Antiviral (CMV) |

| A4 | 0.525 0.489 0.508 0.323 |

0.040 0.005 0.029 0.012 |

Antiviral (Picornavirus) Antiviral (Hepatitis B) Antibacterial Antibiotic |

| A5 | 0.727 0.569 0.525 0.489 |

0.004 0.011 0.040 0.005 |

Antiviral (Influenza) Antibacterial Antiviral (Picornavirus) Antiviral (Hepatitis B) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).