1. Introduction

Suicide is a public health problem influenced by various biological, psychological, social, and environmental factors. According to the three-stage theory, the stages include suicidal ideation, planning, and attempt or execution. Recognizing warning signs at each stage is critical to prevention and helping those at risk [

1]. The WHO recognizes it as such, and in the Americas, it is the fourth leading cause of death among people aged 15-19 years [

2]. In Colombia, young people between the ages of 20 and 24, especially those between 18 and 19, have a high rate of suicide. Therefore, understanding the protective factors is essential for prevention and treatment, especially among university students [

3].

In this context, body awareness, specifically interoceptive body awareness, emerges as a potentially relevant and underexplored factor [

4]. Interoceptive body awareness refers to the ability to perceive and be aware of internal body sensations such as heartbeat, breathing, digestion, body temperature, and other physiological signals. It is the ability to pay attention to and recognize the body's internal sensations and processes, which includes the ability to sense and understand emotions, bodily needs, and physical responses to various stimuli [

4]. It has been suggested that greater interoceptive body awareness may be associated with better mental health and psychological well-being, which in turn may act as a protective factor against suicide risk [

5].

The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) is a questionnaire based on the understanding of interoceptive and body awareness to multidimensionally assess internal body sensations. It was designed to overcome previous limitations by distinguishing between beneficial and maladaptive aspects of body awareness, allowing for a more detailed assessment [

6].

The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) assesses interoceptive awareness along eight distinct dimensions [

6]. These dimensions represent specific aspects of interoceptive body awareness and provide a detailed assessment of the perception of internal body sensations.

These dimensions provide a comprehensive assessment of interoceptive body awareness, including aspects such as attention to bodily sensations, emotional regulation, trust in bodily cues, and the relationship between bodily sensations and emotions. Assessment of these dimensions can provide valuable information about the perception and interpretation of internal body sensations, as well as the ability to use this information to regulate emotions and emotional well-being [

6].

Embodied cognition theory postulates that the body and mind are intimately connected, extending beyond the brain to include the entire body and its interaction with the environment. This theory suggests that cognition is based on modality-specific sensory and motor representations. Recently, there has been growing interest in exploring this idea, particularly in relation to understanding concrete concepts of objects and actions. This exploration could serve as a key test to validate the embodied cognition hypothesis in general. From this perspective, bodily awareness may play a key role in emotional regulation and environmental perception, potentially influencing suicide vulnerability [

7].

However, despite increasing attention to the importance of mental health in university settings, there is a lack of research that identifies conceptual and methodological challenges for health promotion [

8].

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine whether there is a predictive relationship between interoceptive awareness and suicidal intent by assessing the ability of the variables to predict the latter. We also explored how one variable might influence the other, and how to use methods such as bootstrapping to obtain more accurate estimates of results when the data do not follow a normal distribution.

2. Materials and Methods

An observational cross-sectional study was conducted with the aim of exploring body image and suicidal orientation in Rehabilitation Science students at a Colombian university during the year 2023. The sample consisted of undergraduate students selected by convenience sampling and invited to participate on a voluntary basis. The questionnaires were administered online through Google Forms in three sessions, with the presence of a researcher to clarify doubts.

The MAIA consists of 32 items divided into 8 dimensions that assess interoceptive awareness using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (always). The total score indicates the level of body awareness, with questions 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 scored backwards. The ISO-30 questionnaire, on the other hand, consists of 30 suicidality questions answered on a four-point Likert scale. Its purpose is to assess the presence and intensity of suicidal ideation over a 30-day period. The ISO-30 has 5 dimensions, with scores ranging from 0 to 18 for each dimension, and a total score ranging from 0 to 90. It also includes critical factors for identifying individuals at risk. It is important to note that both instruments have been previously validated in a Colombian university population [

9,

10].

JASP software was used for statistical analysis. The following procedures were carried out:

MAIA rating: based on the median 2.9 (top = best interoceptive awareness; bottom = worst). For this, I divided the sample into quartiles 25, 50, 75%).

ISO-30 score based on the median 34 (above or equal = more suicidal intent; below = less intent). For this I divided the sample into quartiles 25, 50, 75%).

Frequency of MAIA and ISO-30 variables based on ratings between males and females.

Chi-square to check if there is a difference between the frequencies of men and women.

Binary logistic regression to test whether the MAIA score is associated with the ISO-30 score.

Area under the curve, sensitivity, and specificity.

Linear regression to test whether the total MAIA score explains the variation in the total ISO-30 score.

Bootstrap: resampling. This is an estimated resampling model. It is used to propose an increase in sample size in the case of non-normally distributed data.

3. Results

Based on the division of the sample according to the MAIA and ISO-30 cut-off points defined by the median, a higher frequency (51.8%) of students below the median in the MAIA percentile was observed, indicating lower interoceptive awareness in this group. This categorization approach allowed us to identify those with lower interoceptive body awareness. In addition, those who presented an ISO-30 score above the median were categorized as having higher interoceptive awareness. These findings are consistent with the data presented in

Table 1.

The data, presented in

Table 2, show the frequency distribution of participants by gender and their classification into MAIA and ISSO-30 percentiles. However, chi-squared tests and log odds ratio analyses demonstrate no significant association between gender and MAIA and ISSO-30 percentiles. This suggests that gender is not significantly related to interoceptive awareness and suicidal intent in this sample.

The logistic regression model presented in

Table 3 shows that between 16% and 21% of the variation in the ISSO-30 percentile is explained by the MAIA percentile (Cox & Snell R² = 0.16; Nagelkerke R² = 0.21; p < 0.01). Age does not show a statistically significant influence in this model (confounding variable; p = 0.46). In addition, individuals with a MAIA score of 2.9 or higher have a significantly lower likelihood of suicidal ideation, with an odds ratio of 0.17 (p = 2.41e-7), representing a protective factor of 83%.

These performance metrics, shown in

Table 4, indicate the effectiveness of the model in predicting suicidal intent as a function of ISO-30 percentile. The AUC (area under the curve) value of 0.69 indicates moderate discriminative power of the model. Sensitivity, which measures the proportion of true positives correctly identified by the model, is 0.71, indicating that the model correctly identifies suicidal individuals 71% of the time. Specificity, which measures the proportion of true negatives correctly identified by the model, is 0.70, indicating that the model correctly identifies non-suicidal individuals 70% of the time. Accuracy, also known as positive predictive value, is 0.71, indicating the proportion of true positive predictions out of all positive predictions made by the model. Overall, these metrics suggest moderate performance of the model in predicting suicidal intent.

The data Model Summary - ISO30_puntaje_total indicate that the linear regression model applied to the ISO-30 Total Score has a coefficient of determination (R²) of 31% in its fitted form, meaning that the model explains approximately 31% of the variability in the ISO-30 Total Score. This indicates that the model has a moderate ability to predict the ISO-30 total score.

These data correspond to an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) applied to the regression model. The table shows that the regression is significant, with an F-value of 74.06 and an extremely low p-value (5.37e-15), indicating that the regression model is statistically significant. This indicates that at least one of the independent variables included in the model has a significant effect on the dependent variable (ISO30_total_score).

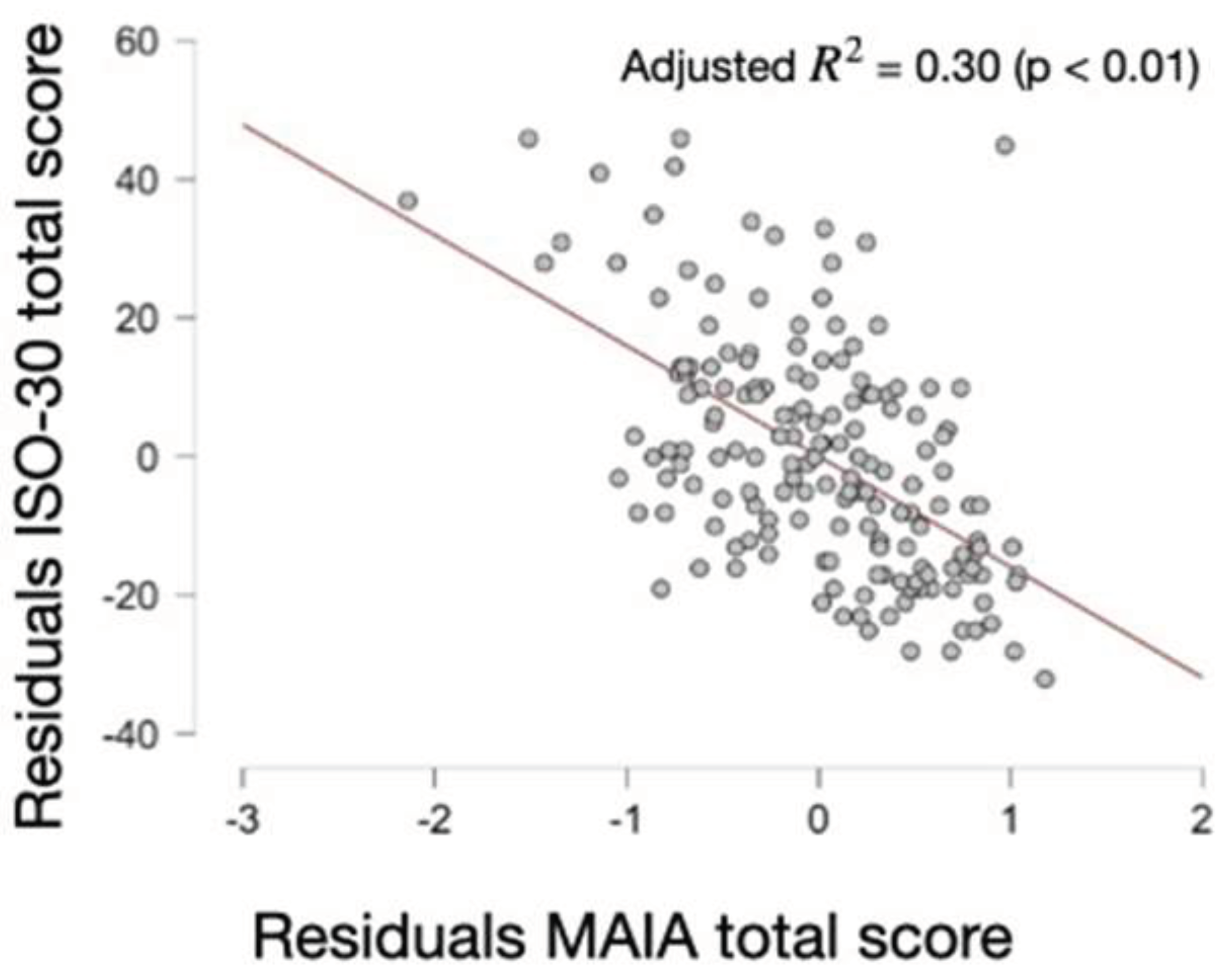

In this analysis (

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7, and

Figure 1) there is an inverse relationship between MAIA score and ISO-30. As the MAIA score increases, the ISO-30 score decreases (B Unstandardized = -15.95; p = 5.37e-15 --> p < 0.000000000000005). Furthermore, it was confirmed that there is no multicollinearity as the tolerance values are greater than 0.25 and the variance inflation factors (VIF) are less than 4. By replicating the sample 1000 times (169,000 data) it was observed that this relationship holds (B Unstandardized = -16) and the confidence interval remains significant (-19.57, -11.60). This supports the consistency and robustness of the relationship found between MAIA and ISO-30 score.

The data presented show the coefficients and collinearity diagnostics for the H₁ model. According to the coefficients, there is a significant negative relationship between MAIA total score and ISO-30 total score (B = -16.00, p < 0.000000000000005), indicating that as interoceptive awareness increases, suicidality decreases. Furthermore, collinearity diagnostics show that there are no serious collinearity problems between the variables in the model, which strengthens the reliability of the results obtained.

4. Discussion

The results of this study provide an overview of the relationship between interoceptive awareness and suicidal orientation in a sample of Colombian university students. First, when the sample was divided according to cut-off points defined by the median on the MAIA and ISO-30, a higher prevalence of students with low interoceptive awareness, indicated by a MAIA score below the median, was observed. This suggests that a significant proportion of participants have limited internal body awareness, which may be a relevant factor to consider when assessing suicidal orientation.

This finding is consistent with previous literature highlighting the critical role of body awareness in mental health and emotional well-being. One interpretation of this finding may be that an enhanced ability to perceive and understand internal bodily sensations may provide greater protection against suicidal orientation [

8]. Concepts of interoception are central to understanding the relationship between body awareness and mental health; people who are more aware of bodily responses may experience emotions with greater intensity, suggesting a link between interoception and emotional experiences relevant to mental health and emotional well-being [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Interoceptive accuracy refers to the objective ability to detect internal sensations, while interoceptive sensitivity refers to the perceived willingness to be internally focused. Interoceptive awareness, on the other hand, involves a metacognitive understanding of interoceptive accuracy. These concepts are critical to understanding how we perceive and relate to internal bodily sensations, and how these perceptions can influence cognitive, emotional, and clinical aspects of our lives [

12].

In our study, the logistic regression model revealed that 16% to 21% of the variance in the ISO-30 percentile was explained by the MAIA percentile, suggesting that interoceptive awareness may play an important role in predicting suicidal orientation. This finding was supported by model performance analysis, which showed a moderate ability to predict suicidal orientation based on the ISO-30 percentile. Linear regression analysis also revealed a significant inverse relationship between MAIA score and ISO-30 score, suggesting that as interoceptive awareness increases, suicidal ideation decreases. This relationship remained consistent across multiple replications of the sample, suggesting a robust and reliable relationship between interoceptive awareness and suicidal orientation.

Similar studies have been found to support the importance of addressing interoceptive body awareness, such as a study of 319 adults with eating disorders in specialized treatment, mostly Caucasian females with a mean age of 21.8 years, most with anorexia nervosa, 59.7% reported current suicidal ideation, and 38.4% had made at least one suicide attempt. Analysis revealed that low body confidence was associated with greater severity of suicidal ideation, with agitation partially mediating this relationship. These findings highlight the importance of considering these factors in the assessment and treatment of suicidal ideation in people with eating disorders [

13].

Studies of "non-suicidal self-injury" (NSSI) have examined how difficulties in body perception might be related to this behavior. Researchers found that people who engage in this type of self-injury have difficulty interpreting cues from their bodies and show poor appraisal of internal sensations [

14]. These findings suggest that difficulties in body perception may predispose to NSSI, which in turn may be used as a mechanism to cope with emotional and bodily uncertainty. These findings provide new insights into the processes underlying NSSI and suggest potential areas for clinical intervention. [

15,

16].

Another study developed an online training program to improve interoceptive awareness and reduce suicidal ideation. Participants showed significant improvements in interoception and body awareness after completing specific exercises. The intervention also showed promise in improving emotional awareness and self-regulation. Although more research is needed to fully understand the results, the program was associated with improvements in suicidal ideation, eating disorders, and general psychological symptoms. [

5].

Another study compared body and pain thresholds between people with and without a history of repetitive self-injury. Thirty-four participants with a history of self-injury and 32 in the control group were recruited by purposive sampling. Self-injury and aspects of body perception were assessed using questionnaires and pain sensitivity tests. The results showed greater dysfunction of the bodily self in those with a history of self-injury, especially in sensation perception and emotional regulation. In terms of pain sensitivity, women with self-injury had higher thresholds, whereas a reverse pattern was observed in men, although this result should be interpreted with caution due to the small size of the male sample [

17].

Research also examined the relationship between interoceptive dysfunction and suicidal behavior in participants with a history of suicide attempts. It was found that those with a history of suicide attempts had higher concentrations of exhaled carbon dioxide after breath-holding tests and lower brain activity in areas associated with interoception and body awareness during attention to heart sensations. These findings suggest that interoceptive dysfunction, particularly related to cardiac perception, may play an important role in suicidal behavior by influencing how people process and respond to internal signals from their bodies. In summary, these findings highlight the importance of further investigating the relationship between internal body perception and mental health [

18].

Finally, a study was found that evaluated the impact of the Biological Movement (BM) program, based on mindful movement, on the psychological well-being and interoceptive awareness of participants. An 8-week training program was implemented for kinesiology students at the University of Perugia, Italy. Results showed significant improvements in interoceptive awareness and positive mental health. The MB program improved participants' psychological well-being and the connection between physical and emotional sensations [

19].

Our study suggests that improved perception and understanding of internal bodily sensations may protect against suicidal ideation by improving emotional regulation and stress response.

Interventions to promote interoceptive awareness may be effective in preventing suicide and promoting psychological well-being [

20,

21]. This is also supported by findings from a systematic review where dysfunctional interoception is associated with mental health disorders and suicide. We reviewed studies on the association between interoception and suicidality. Evidence of reduced interoceptive accuracy was found in those who attempted suicide. There is also evidence of interoceptive sensitivity disturbances at all stages of suicide, such as lack of trust in one's own bodily sensations. Additionally, problems in the cognitive and emotional evaluation of interoceptive sensations were observed, especially in those who attempted suicide. These findings suggest that interoceptive issues may be important indicators of suicide risk. However, further research is needed to fully understand their role and how other variables such as depression and emotional regulation come into play [

22].

However, it is important to keep in mind the limitations of this study. The cross-sectional nature of the research design precludes the establishment of definitive causal relationships between interoceptive awareness and suicidality. In addition, the sample was limited to Colombian university students, which limits the generalizability of the results to other populations.

5. Conclusions

This study provides insight into the relationship between interoceptive awareness and suicidal orientation in Colombian university students. It reveals a significant prevalence of students with low interoceptive awareness, highlighting the importance of this factor in the assessment of suicidal orientation. The results support the notion that a greater ability to perceive and understand internal bodily sensations may provide greater protection against suicidal ideation by improving emotional regulation and stress response.

Logistic regression analysis revealed a significant relationship between interoceptive awareness and suicidality, suggesting its crucial role in predicting the latter. In addition, an inverse relationship was observed between MAIA and ISO-30 scores, suggesting that an increase in interoceptive awareness is associated with a decrease in suicidality.

These findings are consistent with previous literature highlighting the importance of body awareness in mental health and emotional well-being. The concepts of interoceptive accuracy and interoceptive sensitivity are fundamental to understanding how we perceive and relate to internal bodily sensations, which may have implications for cognitive, emotional, and clinical aspects of our lives.

Future research with longitudinal designs and in diverse populations is needed to further explore this relationship between interoceptive accuracy and interoceptive sensitivity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.L.M.-H. methodology, R.S.-M., and R.J.-V.; software, J.M.C.-G.; validation, J.P.; formal analysis, O.L.M.-H. and CY-M.; investigation, MP-AO. and C.S.-S.; resources, AM-S; data curation J.L.S.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, MP-SC.; writing—review and editing, O.L.M.-H., R.J.-V., and J.M.C.-G.; visualization C.S.-S.; supervision, J.M.C.-G. and R.J.-V.; project administration, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Colombian School of Rehabilitation (ECR-CI-INV-121-2021) within the framework of the Mental Health Early Warning Program. Two online questionnaires were used: the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) to measure body awareness and the Inventory of Suicide Orientation-30 (ISO-30) to assess suicidal orientation. Informed consent was obtained from participants before they completed the questionnaires.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ropaj, E. Hope and suicidal ideation and behaviour. Curr Opin Psychol. 2023, 49, 101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Suicidio. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide.

- Forensis, Datos para la Vida. Medicina Legal. 2021. Available online: https://www.sismamujer.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2013-Boletin-No-1.-Noviembre-7-de-2013.-Violencias-contra-las-mujeres-segun-Forensis-del-INML-CF.-Cifras-2011-y2012.-1.pdf.

- Perry, T.R.; Wierenga, C.E.; Kaye, W.H.; Brown, T.A. Interoceptive Awareness and Suicidal Ideation in a Clinical Eating Disorder Sample: The Role of Body Trust. Behav Ther. 2021, 52, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.R.; Forrest, L.N.; Perkins, N.M.; Kinkel-Ram, S.; Bernstein, M.J.; Witte, T.K. Reconnecting to Internal Sensation and Experiences: A Pilot Feasibility Study of an Online Intervention to Improve Interoception and Reduce Suicidal Ideation. Behav Ther. 2021, 52, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehling, W.E.; Acree, M.; Stewart, A.; Silas, J.; Jones, A. The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness, Version 2 (MAIA-2). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahon, B.Z. What is embodied about cognition? Lang Cogn Neurosci. 2015, 30, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalsa, S.S.; et al. Interoception and Mental Health: A Roadmap. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2018, 3, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaño Castrillón, J.J.; Cañón Buitrago, S.C.; López Tamayo, J.J. Riesgo suicida en estudiantes universitarios de Manizales (Caldas, Colombia). Inf Psicológicos. 2022, 22, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Hurtado, O.L.; et al. Exploring the Link between Interoceptive Body Awareness and Suicidal Orientation in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023, 13, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfinkel, S.N.; Seth, A.K.; Barrett, A.B.; Suzuki, K.; Critchley, H.D. Knowing your own heart: Distinguishing interoceptive accuracy from interoceptive awareness. Biol Psychol. 2015, 104, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, A.K. Interoceptive inference, emotion, and the embodied self. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013, 17, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, M.E.; Lieberman, A.; Siegfried, N.; Henretty, J.R.; Bass, G.; Cox, S.A.; Joiner, T.E. Body Trust, agitation, and suicidal ideation in a clinical eating disorder sample. Int J Eat Disord. 2020, 53, 1746–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrest, L.N.; Smith, A.R. A multi-measure examination of interoception in people with recent nonsuicidal self-injury. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2021, 51, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagan, C.R.; Rogers, M.L.; Brausch, A.M.; Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Joiner, T.E. Interoceptive deficits, non-suicidal self-injury, and suicide risk: A multi-sample study of indirect effects. Psychol Med. 2019, 49, 2789–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, D.R.; Smith, A.R.; Forrest, L.N.; Witte, T.K.; Bodell, L.; Bartlett, M.; Siegfried, N.; Goodwin, N. Interoceptive Deficits, Non-suicidal Self-Injury, and Suicide Attempts Among Women with Eating Disorders. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018, 48, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, A.S.; Davine, T.P.; Snorrason, I.; Houghton, D.C.; Woods, D.W.; Lee, H.J. Body-focused repetitive behaviors and non-suicidal self-injury: A comparison of clinical characteristics and symptom features. J Psychiatr Res. 2020, 124, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVille, D.C.; Kuplicki, R.; Stewart, J.L.; Tulsa 1000 Investigators; Paulus, M.P.; Khalsa, S.S. Diminished responses to bodily threat and blunted interoception in suicide attempters. Elife. 2020, 9, e51593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Waure, C.; Chiavarini, M.; Buratta, L.; Carestia, R.; Gobetti, C.; Lupi, C.; Sorci, G.; Mazzeschi, C.; Biscarini, A.; Spaccapanico Proietti, S. Can a mindful movement-based program contribute to health? Results of a pre-post intervention study. Eur J Public Health. 2023, 33 (Suppl. S2), ckad160.1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.D. Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003, 13, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, M.E.; Rogers, M.L.; Joiner, T.E. Body trust as a moderator of the association between exercise dependence and suicidality. Compr Psychiatry. 2018, 85, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hielscher, E.; Zopf, R. Interoceptive Abnormalities and Suicidality: A Systematic Review. Behav Ther. 2021, 52, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).