1. Introduction

The length of stay for preterm and ill newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) can be considerably extended [

1]. This period often causes a separation between parents and their offspring, limiting emotional and physical closeness [

2]. Furthermore, the period after birth is critical in the bonding process between parents and newborns [

3]. Previous studies have shown that alterations in their role are the greatest source of stress for parents [

4,

5,

6].

During the stay in the NICU, parents can play a crucial role in the care of their infants [

7]. Models such as Family-Centred Care (FCC) and Family Integrated Care (FICare) promote parental participation [

8]. These programmes allow parents to become confident, knowledgeable, and independent primary caregivers. FCC and FICare can shorten the time to use the nasogastric tube, reduce hospital length of stay, increase the rate of exclusive breastfeeding, improve the overall prognosis of preterm infants, also exerting also positive effects on parents [

9].

Recent studies reported a decrease in parental presence and participation during NICU stay due to Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic that determined restricted access policies in hospitals [

10,

11,

12]. Restricted visit policies resulted in a negative experience of parenthood and a negative impact on breastfeeding [

11] The pandemic has impacted parental well-being directly through stress due to COVID-19, but also indirectly due to the health policies and visiting restrictions, which significantly altered the experience of parenthood. The ability to cope with this challenging situation depended on individual features as well as the physical and social environmental factors of the NICU [

10,

13].

The impact of COVID-19 restrictions on the access to NICU by parents was qualitatively described in several published studies [

10,

11,

12], but none quantitatively reported the limits related to decreased participation in care.

In the Italian healthcare care context, no instruments were available to quantitatively evaluate the participation in the NICU activities. Recently, Scarponcini Fornaro and colleagues validated the Italian version of the scale ‘Parental Participation in Care: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (PPCS: NICU)” which allows to evaluate the parents’ participation in care of their neonates [

14,

15].

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this study is to describe the barriers to a good parents’ participation during the stay in the NICU using PPCS: NICU in the COVID-19 era. A monocentric retrospective cohort study based on a prospectively collected data was designed following the statement ‘Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)’ [

16].

2.1. Sample and Setting

The study was carried out in 22 beds mixed NICU (medical and surgical) of a generic hospital. The study participants included parents whose babies were admitted to the NICU and agreed to participate using a written informed consent form. During data collection, one parent at a time was allowed to enter the NICU twice a day, for a maximum of two hours, due to visiting restrictions related to COVID-19. Only for twins both parents were allowed to enter the NICU simultaneously.

2.2. Data Collection

Parents’ sociodemographic data were retrospectively collected (age, gender, race, occupational status, experience of previous abortion or deaths). Newborns retrospectively recorded variables were gestational age, body weight at admission, type of childbirth, twin-birth, and all medical devices used to support the newborn. During COVID-19 pandemic NICU nurses performed evaluations of parental participation in care, in order to highlights parents with a low participation. Two evaluations for each parent were performed. The first observation was recorded in the first three days. The second observation was provided between the seventh and tenth days of hospitalization. The instruments used was the Italian PPCS:NICU [

15]. It consists of one dimension composed by 16 items, which is similar to the original scale [

14]. The items used a 3-point Likert Scale (3 = always, 2 = sometimes, 1 = never). The highest score that can be obtained is 48, the lowest is 16. A score of 16 points indicates that the parent does not participate in the care of her/ his infant. Higher scores indicate higher participation levels. No cut-off points were specified by the instrument [

14]. The first three items are focused on communication between parent and health professionals. From fourth to fifteenth items the tool covers the interaction between parent and newborn (physical contact, breastfeeding, hygienic care, and support during painful procedures). The last item is focused on parents’ expression of emotions and fears. In the validation study the tool in Italian language showed an overall Content Validity Index (CVI) of 0.976 and a good reliability (Cronbach α= 0.926) [

15] (supplementary material).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Excel software was used to store the data. Summary statistics are presented as absolute frequencies and percentages and as medians and interquartile ranges [IQR] for continuous non-normally distributed data (according to the Shapiro-Wilk test). Nonparametric tests were performed to compare median values reported by each categorical variable using the Kruskal-Wallis test and the U Mann-Whitney test. Bonferroni adjusted p-values were calculated for multiple comparisons. A subgroup analysis by periods was performed to assess whether parental participation differed according to the duration of hospitalisation of their neonates. Pearson’s correlation was performed to estimate the association between continuous variables and tool scores. To balance the effects of any confounders, a multiple logistic regression was used. Statistical significance was established at a P value less than.05. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 22.0. While for the statistical power analysis, G * Power 3.1 [

17].

3. Results

Data collected refers to the period between April and December 2022. Two-hundred and seventy parents were included in this study. 136 participants were female (50.4%). The 21.9% (n=59) of the sample experienced previous abortions, while 2.6% (n=7) experienced previous offspring deaths. For 55.2% (n=149) it was the birth of their first child, and most couples (47.4%, n= 128) experienced a natural childbirth. Most of the cases are Caucasian (88.1%, n=238). The median [IQR] age was 34 [

9] years. All parents’ features are detailed in

Table 1.

One hundred and fifty-two newborns were included in the study, of which 11.2% (n = 17) were twins. Fifty newborns (37.1%) were preterm. The median body weight at admission [IQR] was 2790 [1140] grams. The median gestational age was 37 [

5] weeks.

The overall participation in care, at admission, reported a median score of 41 [

10]. After approximately seven days of hospitalization, a significant overall improvement was observed with a median score of 46 [

8] and p < 0.001 was observed.

3.1. Barriers Related to Parental Background

Mothers’ participation in care levels appears to be significantly higher compared to fathers (median score of 42 [

8] and 39 [

11], respectively; p = 0.017). This result is also confirmed by the second observations, when mothers reported a median score of 46 [

6] versus 44 [

9] reported by fathers (p = 0.003). Parents who lived the birth of their first child reported a better median level of participation in care compared to those who lived the birth of their second child (42 [

8] vs 38 [

12]); p = 0.005). Furthermore, this difference appears to remain unchanged over time with a higher score in parents of only children (46 [

6] vs 44 [

10]); p = 0.015). African parents reported significantly lower participation in care with a median score of 30.5 [

15] vs 42 [

8] reported by Caucasian people and 45 [

8] by Hispanics (p < 0.001), this difference remains significant also in the second observation. Lastly, parents who experienced natural birth showed higher participation in care with a median score of 43 [

8] compared an parents who underwent to emergency cesarean section (median score 38 [

12]) with a p < 0.001, also in this case, the difference still significative over time.

There was no correlation between age and their parenthood ( r = -0.80; p= 0.18 at admission and r = -0.87; p= 0.15 after about 7 days). Other factors such as previous abortions; previous deaths and occupational status did not affect the level of parenthood during the stay in the NICU. All scores are detailed in

Table 1.

3.2. Barriers Related to Neonates Features

Parents of extremely premature newborns reported a significantly lower interaction with their infant with a median score of 31 [

9] compared to parents of term newborns (median score 42 [

9]; p < 0.001). However, after approximately seven days of hospitalisation, there was not a sginificant difference between the parental participation scores of preterm and term neonates. Parents of twins showed significantly higher partcipation only in the second evaluation with a median value of 45 [

8] vs 47 [

1] reported by parents of the only newborns (p = 0.029). According to the Mann-Whitney U test, the fathers reported a higher participation than those of the only neonates in care with a median value of 44 [

8] vs a median value of 42 [

13] (p = 0.025) respectively.

Lastly, all devices related to critically ill conditions were associated with significantly lower interaction between parents and neonates. The only devices not associated with a minor interaction are: peripheral venous catheter, high flow nasal cannula, monitoring of brain functions (

Table 2).

3.3. Multiple Linear Regression

Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to limit the influence of possible confounders (

Table 3 and

Table 4).

It was confirmed that participation in care is negatively affected by parents’ gender (β= -.0.176; 95% CI -0.482 to -0.161; p< 0.001), type of delivery (β= -0.178; 95% CI (-2.942 to -1.041); p< 0.001) and parents’ ethnicity (β= -0.256; 95% CI: -5.558 to -2.802; p< 0.001). Furthermore, some clinical device or condition could negatively affect the interaction between parents and their newborns: catheter placement in the bladder catheter (β= -0.154; 95% CI: -9.904 to -1.100; p= 0.014) or presence of stoma (β= -0.226; 95% CI: -21.315 to -9.347; p< 0.001).

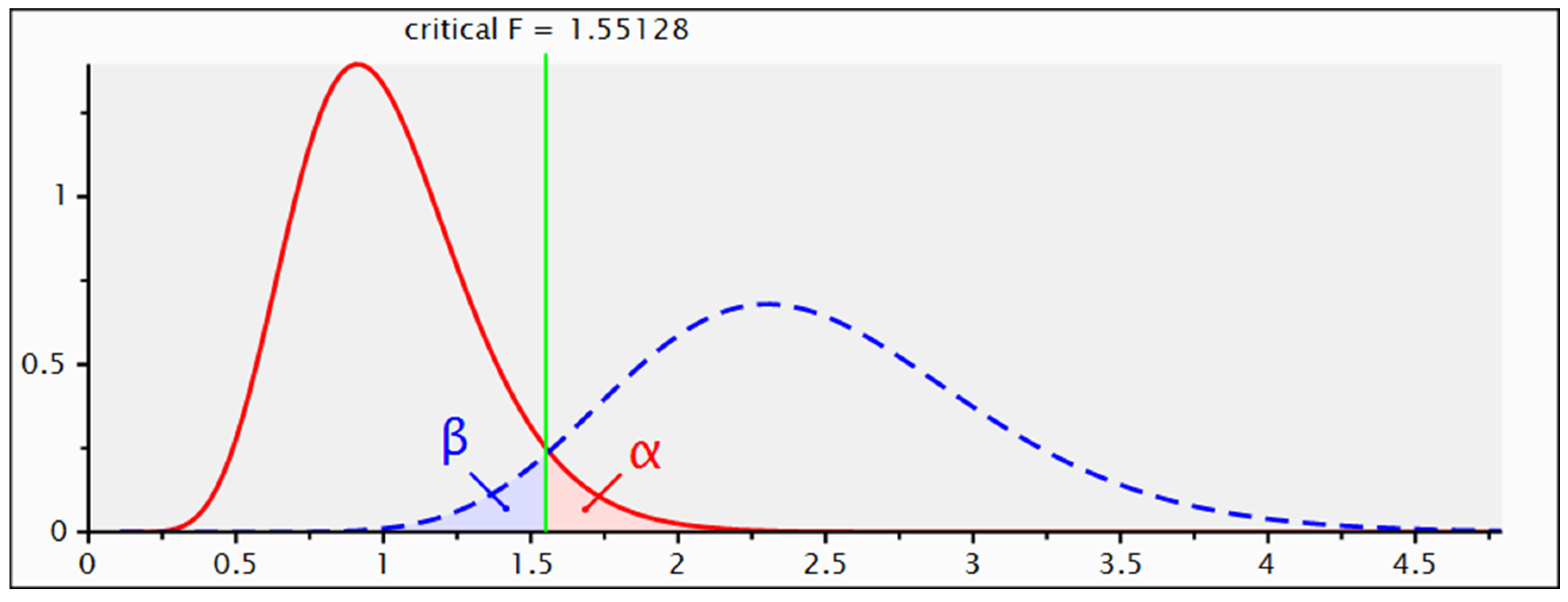

3.4. Sensitivity Power Analysis of Multiple Linear Regression

Sensitivity power analysis (

Figure 1) allowed to determine the minimum effect size to which this study was sensitive. For a power of 0.95, based on the sample size recruited (270 participants) and an alpha level of 0.05, this analysis showed sensitivity for an effect size f2 = 0.13, which is defined as medium.

4. Discussion

This study described the early barriers to parenthood during the stay in COVID-19 era. No similar published study had a comparable sample size which has been shown to be sensitive to a medium effect size [

18]. Furthermore, this is the first study to be performed using the PPS:NICU scale after cross-cultural validation for the Italian population. This scale allows a quantitative assessment of the participation by nurses and health professionals. Before, only the Italian EMpowerment of PArents in the Intensive Care-Neonatology (EMPATHIC-N) questionnaire was available, but this tool provides a self-assessment of the quality of care perceived by parents of neonates admitted to NICU [

19]. Another study was carried out using the index parental participation scale (IPP), but no validation study was still carried out to test the Italian version [

20].

The sample highlighted fair general participation in care, according to another Italian study that reported no significant differences in participation before and during pandemic [

20]. Despite this, our results highlighted an important cultural barrier to parenthood, shown by foreign parents, as described in previous studies. In fact, low awareness about cultural and social factors by healthcare professionals can reduce the effectiveness of communication with families in the NICU, exacerbate family denial, erode trust, and generally have a generally damaging effect on interactions between staff and families [

21,

22]. The impact of parental primary language on communication in the neonatal intensive care unit was also described as a barrier that contributes to suboptimal healthcare delivery [

23]. Probably, the restrictions caused by COVID-19 and the conversations between parents and healthcare professionals often conducted by phone made the impact of these barriers very large.

Parents who have already had other children show a lower participation score, this phenomenon could be due to the lack of baby-sitting as already described by Kerr et al., can be linked to a poor availability of babysitting services for other children [

24]. Furthermore, during the pandemic period, the fear of attending the NICU may have arisen to risk contracting the virus and infecting the closest relatives.

Our findings also highlighted a lower interaction between extremely preterm newborns and their parents. A previously published study described that during the stay in the NICU, mothers of preterm infants experienced disruption of family dynamics, support and bonding; physical and emotional isolation; negative psychological impact compounded by increased concerns, change in maternal role and survival mode mentality [

25]. Furthermore, the complex psychosocial needs of parents of extremely preterm infants were challenging for the NICU and its staff already before the COVID-19 pandemic [

26]. Communicating parents’ needs and informing them about the available support was essential to help them to cope with their infants’ hospitalization [

26]. However, restrictions during the COVID-19 era often made this not possible. It is already described that, during pandemic period, parents experienced increased stress due to the restricted NICU visitation policies, limited opportunities to care for their infant, lack of support, and inconsistent communication regarding their infant status and COVID-19 protocols [

27].

According to our results, fathers seemed less involved than mothers in the care of their newborns. This is supported by another result that shows how the fathers of the twins, who had the opportunity to visit their children together with their partner, reported a higher value of participation than the fathers of the only children. As previously described, this is reportable to relational suffering (separation from the partner, separation from the newborn) [

28]. Furthermore, fathers who experienced minor restrictions reported a greater involvement in caregiving activities [

29]. A recent study highlights how early positive perceptions of fatherhood could significantly predict fathers' confidence in neonatal care and to be significantly influenced by psychological satisfaction due to the intimate relationship between fathers and their offspring [

30].

Lastly, this study showed a lower involvement of parents who had a planned or unplanned cesarean section. Two previous published studies support these findings. Mothers who experienced cesarean section reported having worse postnatal depression, a lower maternal bonding, and openness emotions [

31]. Furthermore, cesarean sections cause maternal feelings such as sadness and disappointment with the unplanned birth process [

32].

Before the pandemic, implementing parent-infant closeness in the NICU was a challenge for nurses and healthcare professionals [

1]. Optimization in neonatal care, such as zero separation and parent-infant closeness, was reset with the onset of the pandemic. The ideal collaboration between NICU nurses and parents has always been characterized by flexibility and reciprocity, and is based on verbal and action dialogues [

7]. Obviously, during the pandemic period, this was very limited with a negative impact on the well-being of parents and newborns.

5. Conclusions

Many studies provided a qualitative analysis of the feelings and emotions experienced by parents of infants admitted to the NICU during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study is one of the few that conducted a quantitative description of the interactions between parents and their newborns. This was possible using the Italian PPCS:NICU Scale that was validated in the Italian context. Despite a general fairly good participation in care, some barriers to parenthood during NICU stay in the COVID-19 era were highlighted. Some more disadvantaged categories have reported lower scores: parents of cultural and linguistic minorities, parents of multiple children, and fathers. The COVID-19 pandemic made several Family-Centred Care activities not possible with a greater impact on those who benefited the most from these facilities (24 hour visit, kangaroo care, cultural mediation service, psychological or educational support).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Italian version of the scale ‘Parental Participation in Care: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (PPCS: NICU)’

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B. and D.S.F.; methodology, E.B. and S.B.; formal analysis, E.B. and D.S.F.; investigation, D.S.F. and A.D.; data curation, D.S.F. and L.N.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B., D.S.F. and L.N.; writing—review and editing, V.C., S.B. and L.R.; visualization, C.D.P. and D.P.; supervision, S.D.V. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Parents who participated in this study were not subject to any interventions. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from patients to publish this article. The research was carried out according to the principles of the original Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. Data were stored and managed in accordance with current Italian legislation on data protection. The collected were aggregated and anonymously analyzed. The present study was approved by the Institutional Internal Review Board of the Department of Innovative Technologies in Medicine & Dentistry of the University of Chieti with approval number ‘CRRM_2023_12_07_01’.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This study was designed following the statement ‘Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE). von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2008, 61, 344–349, doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- van Veenendaal, N.R.; Labrie, N.H.M.; Mader, S.; van Kempen, A.A.M.W.; van der Schoor, S.R.D.; van Goudoever, J.B.; CROWN Study Group; Bertino, E.; Bhojnagarwala, B.; Bodrogi, E.; et al. An International Study on Implementation and Facilitators and Barriers for Parent-infant Closeness in Neonatal Units. Pediatric Investigation 2022, 6, 179–188. [CrossRef]

- Bergman, N.J. Birth Practices: Maternal-neonate Separation as a Source of Toxic Stress. Birth Defects Research 2019, 111, 1087–1109. [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.B. Neonatal Nurses’ Views on the Bamers to Parenting in the Intensive Care Nursery - a Pilot Study. AUSTRALIAN CRITICAL CARE 1997, 10. [CrossRef]

- Montirosso, R.; Provenzi, L.; Calciolari, G.; Borgatti, R.; NEO-ACQUA Study Group Measuring Maternal Stress and Perceived Support in 25 Italian NICUs: Maternal Stress and Perceived Support in NICUs Instead of Measuring Maternal Stress and Perceived Support. Acta Paediatrica 2012, 101, 136–142. [CrossRef]

- Heidarzadeh, M.; Heidari, H.; Ahmadi, A.; Solati, K.; sadeghi, N. Evaluation of Parental Stress in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Iran: A National Study. BMC Nurs 2023, 22, 41. [CrossRef]

- Okito, O.; Yui, Y.; Wallace, L.; Knapp, K.; Streisand, R.; Tully, C.; Fratantoni, K.; Soghier, L. Parental Resilience and Psychological Distress in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J Perinatol 2022, 42, 1504–1511. [CrossRef]

- Sundal, H.; Vatne, S. Parents’ and Nurses’ Ideal Collaboration in Treatment-Centered and Home-like Care of Hospitalized Preschool Children – a Qualitative Study. BMC Nurs 2020, 19, 48. [CrossRef]

- Soni, R.; Tscherning, C. Family-Centred and Developmental Care on the Neonatal Unit. Paediatrics and Child Health 2021, 31, 18–23. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Dong, L. The Effect of Family Integrated Care on the Prognosis of Premature Infants. BMC Pediatr 2022, 22, 668. [CrossRef]

- Polloni, L.; Cavallin, F.; Lolli, E.; Schiavo, R.; Bua, M.; Volpe, B.; Meneghelli, M.; Baraldi, E.; Trevisanuto, D. Psychological Wellbeing of Parents with Infants Admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit during SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Children 2021, 8, 755. [CrossRef]

- Muniraman, H.; Ali, M.; Cawley, P.; Hillyer, J.; Heathcote, A.; Ponnusamy, V.; Coleman, Z.; Hammonds, K.; Raiyani, C.; Gait-Carr, E.; et al. Parental Perceptions of the Impact of Neonatal Unit Visitation Policies during COVID-19 Pandemic. bmjpo 2020, 4, e000899. [CrossRef]

- Darcy Mahoney, A.; White, R.D.; Velasquez, A.; Barrett, T.S.; Clark, R.H.; Ahmad, K.A. Impact of Restrictions on Parental Presence in Neonatal Intensive Care Units Related to Coronavirus Disease 2019. J Perinatol 2020, 40, 36–46. [CrossRef]

- Feeley, N.; Waitzer, E.; Sherrard, K.; Boisvert, L.; Zelkowitz, P. Fathers’ Perceptions of the Barriers and Facilitators to Their Involvement with Their Newborn Hospitalised in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: <i>Fathers’ Perceptions of Barriers and Facilitators</i>. J Clin Nurs 2013, 22, 521–530. [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, S.S.; Keskin, Z.; Yavaş, Z.; Özdemir, H.; Tosun, G.; Güner, E.; İzci, A. Developing the Scale of Parental Participation in Care: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and Examining the Scale’s Psychometric Properties. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 2021, 65, 103037. [CrossRef]

- Scarponcini Fornaro, D.; Della Pelle, C.; Buccione, E. Parental Participation in Care during Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Stay: A Validation Study. ij 2023, 1, 81–88. [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2008, 61, 344–349. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behavior Research Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [CrossRef]

- Selya, A.S.; Rose, J.S.; Dierker, L.C.; Hedeker, D.; Mermelstein, R.J. A Practical Guide to Calculating Cohen’s F2, a Measure of Local Effect Size, from PROC MIXED. Front. Psychology 2012, 3. [CrossRef]

- Dall’Oglio, I.; Fiori, M.; Tiozzo, E.; Mascolo, R.; Portanova, A.; Gawronski, O.; Ragni, A.; Amadio, P.; Cocchieri, A.; Fida, R.; et al. Neonatal Intensive Care Parent Satisfaction: A Multicenter Study Translating and Validating the Italian EMPATHIC-N Questionnaire. Ital J Pediatr 2018, 44, 5. [CrossRef]

- Bua, J.; Mariani, I.; Girardelli, M.; Tomadin, M.; Tripani, A.; Travan, L.; Lazzerini, M. Parental Stress, Depression, and Participation in Care Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Prospective Observational Study in an Italian Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 737089. [CrossRef]

- Van McCrary, S.; Green, H.C.; Combs, A.; Mintzer, J.P.; Quirk, J.G. A Delicate Subject: The Impact of Cultural Factors on Neonatal and Perinatal Decision Making. Journal of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine 2014, 7, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Bracht, M.; Kandankery, A.; Nodwell, S.; Stade, B. Cultural Differences and Parental Responses to the Preterm Infant at Risk: Strategies for Supporting Families. Neonatal Network 2002, 21, 31–38. [CrossRef]

- Palau, M.A.; Meier, M.R.; Brinton, J.T.; Hwang, S.S.; Roosevelt, G.E.; Parker, T.A. The Impact of Parental Primary Language on Communication in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J Perinatol 2019, 39, 307–313. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S.; King, C.; Hogg, R.; McPherson, K.; Hanley, J.; Brierton, M.; Ainsworth, S. Transition to Parenthood in the Neonatal Care Unit: A Qualitative Study and Conceptual Model Designed to Illuminate Parent and Professional Views of the Impact of Webcam Technology. BMC Pediatr 2017, 17, 158. [CrossRef]

- Richter, L.L.; Ku, C.; Mak, M.Y.Y.; Holsti, L.; Kieran, E.; Alonso-Prieto, E.; Ranger, M. Experiences of Mothers of Preterm Infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Advances in Neonatal Care 2023, Publish Ahead of Print. [CrossRef]

- Bry, A.; Wigert, H. Psychosocial Support for Parents of Extremely Preterm Infants in Neonatal Intensive Care: A Qualitative Interview Study. BMC Psychol 2019, 7, 76. [CrossRef]

- Yance, B.; Do, K.; Heath, J.; Fucile, S. Parental Perceptions of the Impact of NICU Visitation Policies and Restrictions Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Advances in Neonatal Care 2023, Publish Ahead of Print. [CrossRef]

- Bembich, S.; Tripani, A.; Mastromarino, S.; Di Risio, G.; Castelpietra, E.; Risso, F.M. Parents Experiencing NICU Visit Restrictions Due to COVID-19 Pandemic. Acta Paediatr 2021, 110, 940–941. [CrossRef]

- Adama, E.A.; Koliouli, F.; Provenzi, L.; Feeley, N.; van Teijlingen, E.; Ireland, J.; Thomson-Salo, F.; Khashu, M.; FINESSE Group COVID-19 Restrictions and Psychological Well-being of Fathers with Infants Admitted to NICU—An Exploratory Cross-sectional Study. Acta Paediatrica 2022, 111, 1771–1778. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Lee, S. Perceptions of Fatherhood and Confidence Regarding Neonatal Care among Fathers of High-Risk Neonates in South Korea: A Descriptive Study. Child Health Nurs Res 2023, 29, 229–236. [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Ishii, H.; Toda, M.; Tomimatsu, T.; Katsuyama, H.; Nakai, Y.; Shimoya, K. Maternal Depression and Mother-to-Infant Bonding: The Association of Delivery Mode, General Health and Stress Markers. OJOG 2017, 07, 155–166. [CrossRef]

- Zanardo, V.; Soldera, G.; Volpe, F.; Giliberti, L.; Parotto, M.; Giustardi, A.; Straface, G. Influence of Elective and Emergency Cesarean Delivery on Mother Emotions and Bonding. Early Human Development 2016, 99, 17–20. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).