Current address: Social Work, Mount Royal University, 4825 Mount Royal Gate SW, Calgary, AB, Canada T3E 6K6

1. Introduction

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is a lifelong disorder that impacts both brain and body functions. Regrettably, it has often been framed as having levels of impairment that preclude pro-social functioning, although more recent research has shown this to be a significant overgeneralization, tending towards stigmatization [

1,

2]. As well, more recent research shows that FASD exists across a broad range of expressions and thus also capacities. In addition, strengths can be in various domains while limitations may exist in other domains with experiences being quite uneven across the FASD population. There is not a universal or common expression of FASD; rather it is heterogenous [

3]. The rates of FASD in the general population in North America now appear to be 4-5%, inclusive of various expressions and intensity of FASD [

4,

5]. There is also an unknown number of people who are not diagnosed but believe they are experiencing the effects of perinatal alcohol exposure [

6]. This can occur for a variety of reasons such as lack of confirmation of alcohol use in pregnancy, which partially arises out of failure to ask about alcohol use during pregnancy care and lack of access to assessment services as well as a misattribution of observed behaviors that are labeled in some fashion as a ‘badly behaving person’ as opposed to inquiring into why behaviors exist [

7,

8].

This paper presents a secondary data analysis of anonymous survey responses of people living with FASD in what might be euphemistically called the real world. The goal of the paper is to highlight how life is experienced by those living with FASD, There is very little data available that considers such voices articulating daily experiences including interactions between a person with FASD and health care, education, criminal justice and the community. This work builds on a previous survey that looked at the whole-body physiological experiences of FASD which “… dramatically highlights the significant adverse effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on long-term vulnerability to disease and disorders over the life course, above and beyond what has traditionally been described in the literature.” ([

9], p. 211). Thus, FASD can be seen as a “whole body” disorder as opposed to one that is restricted to the brain and behavior.

The current project is a logical follow up to better understand the experiences and challenges of living with FASD. It allows those living with FASD to give voice to their own experiences.

2. Literature Review

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) seemed to enter the medical lexicon following the1968 work of Lemoine et al., [

10] although, as Brown et al., note, awareness of concerns with alcohol consumption and pregnancy date back beyond the 1700’s [

11]. Jones [

12] provided one of the earliest detailed examination of the morphological and developmental features. This was followed closely by a further paper in which Jones et al., [

13] explored what they termed to be” the

first reported association between maternal alcoholism and aberrant morphogenesis in the offspring” (p. 1267). Both articles remain prominent in the literature having been cited each well over 3,000 times. It may well be argued Jones et al. [

12,

13] laid the foundation for how FAS would be seen for years. Even now, FASD may still be referred to as FAS along with related terminology such as Alcohol Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder (ARND), Alcohol Related Birth Defects (ARBD) and neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (ND-PAE). The term Fetal Alcohol Effects (FAE) was also used to describe a child with intellectual disabilities connected to alcohol consumption in pregnancy [

14] Today, FASD is recognized in medical, nursing, midwifery, social work and psychology, criminal justice and other sociologically related disciplines, although the depth of that awareness is still wanting. However, that should not lead to a conclusion that there is a broad understanding of what it means to live with FASD [

15,

16,

17].

FASD has now come to be known as an “umbrella term” that considers impacts on social, behavioral, physical and cognitive aspects of a person’s life, although there are expressive variations across those impacted. Thus, there is no “one” presentation. It also exists across a spectrum. Those with similar areas of impact may express them in very different ways. As well, the expression of FASD in an individual’s life tends to shift over the life span [

18]. In this respect, life course [

19] theory assists in understanding how living with FASD has many manifestations. Not only is there no one form of FASD, but there is also no one life course pathway.

The diagnosis itself brings stigma (defined as negative and unfair beliefs about people with FASD) which prejudges the person, narrowing the true experience of living with FASD. The prejudgment and a stereotypical view of incapacity versus capacity create a narrative that may have little to do with reality [

20]. When that happens, an authentic understanding of what it means to live with FASD is lost [

21]. This survey seeks to report on the truth of the life being lived, drawing upon the actual experiences which can illustrate aspects of success but also the many challenges that occur throughout the lifespan.[

22] These authors identify clusters of living experiences which include compounding stigma, environmental adversity (such as early life experiences, problems with social determinants of health be available and adversity from a variety of events across the life course), co-occurring disorders including neurological development, mental health and substance abuse as well as challenges with family functioning.

McLachlan et al. describe that difficulties in daily living can be seen across the life span [

23]. They describe these occurring in a number of domains including independent living needs, substance abuse, employment instability, legal problems including victimization, trouble accessing stable housing and disruptions in education. This can be further complicated by the lack of supports for youths transitioning to adulthood [

23,

24,

25] Life course challenges occur not only in daily living but across time and in multiple life domains. [

2,

23]

A better understanding of how life is experienced by those with FASD has the potential to increase understanding and subsequent support in both community and professional settings. In turn, this has the potential to increase the quality of life for a person living with FASD [

24]. An example of this is seen in the results associated with Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) which is an important way to consider the foundations of strength, resilience and risk as people enter adult years from age 18 onwards. The ACEs consider “the relationship of health risk behavior and disease in adulthood to the breadth of exposure to childhood emotional, physical, or sexual abuse, and household dysfunction” and the impact on later life functioning [

25]. Kambeitz et al., [

26,

27] have shown that the linkage between FASD and elevated ACE scores increases the risks for comorbid neurodevelopmental disorders. Understanding the degree of exposure to ACEs in addition to the FASD is vital so that risk minimization and resilience building can occur.

When looked at from a life course perspective [

28,

29] people with FASD often face not only individual event traumas but also cumulative ones arising from ACEs as well as factors that may not be measured in that way. This can include experiencing SDH that adversely affect life outcomes, early life interruptions such as involvement with child intervention services and placement in foster care, often with placement instability, difficulty with establishing social and peer relationships, challenges with integration in school and staying along the same developmental pathway as other children. Individuals with FASD can be vulnerable to negative peer influences due to social isolation as well as challenges with appropriately judging the nature of what is sought in social situations and difficulty assessing risks increasing victimization [

30]. The desire to belong is powerful. This can lead to poor social decision making leading to involvement in the criminal justice system [

24].

While negative experiences for people with FASD are common, the value of protective factors should not be lost. These include early diagnosis and support, stable caregivers, educational, mental and physical health systems that understand the nature of FASD and what is needed for a person to successfully face life’s challenges. Transitioning into adulthood brings its own challenges including having to interact with systems that are based upon chronological age rather than developmental capacity. This means that service systems expect adult capacity which a person living with FASD may not have developed. Adult focused FASD services are even less available than childhood services particularly away from larger centers [

29,

30]. Support plans that serve the individual best are based on what is possible and the recognition that time limited programs are counterproductive. Good programming occurs over extended periods with persistent belief in the possible.

A major barrier in the lives of persons with FASD is that systems serve systems. Eligibility requirements to access services fail to consider the realities of living with FASD. It may seem, for example, equitable to make all applicants for a service to have a full-scale IQ of less than 75 despite evidence that those with FASD can have scattered profiles that can suggest higher IQ’s which do not reflect functional capacity. Equity requires that applicants for a service are considered based upon need in order to be successful as opposed to arbitrary classifications that fail to consider the truth of living. There is no equity, for example, when a person living in some parts of Canada has access to diagnostic and support services while those living elsewhere do not. Even though theoretically everyone may be eligible for diagnostic services [

31,

32]. A further example is that assessment and diagnostic services are more focused on children. Adult clinics are few and hard to access which creates systemic discrimination for an adult. This can be seen in the justice system as the lack of a diagnosis makes it very hard for a court to take into consideration FASD which can then negatively impact sentences [

33].

3. Methodology

An anonymous survey was made available to people with FASD. This was done through community agencies and self help and support groups mainly across North America via an on-line link. There were two periods open for responses - August 2019 to February 2020 and March 2020 - December 2020. All respondents had the same survey available. In total, there were 468 responses analyzed for demographic and thematic purposes. Respondents were assured that there was no way to link responses to their identity. Not all respondents answered all questions which creates some variation in response rates per question meaning that the n for responses varies from question to question.

The survey was developed by the Adult Leadership Committee which is a network of people living with FASD. The areas of inquiry were drawn from their living experiences.

This is a secondary data analysis of anonymous information. The Human Research Ethics Board at Mount Royal University determined this secondary did not require ethics clearance [

34].

4. Results

4.1. Demographics

Survey respondents identified as male 43% and female 55% with 2% as other or prefer not to say. The average age was 30 years. Seventy three percent reported an IQ of 70 or over while the remaining 27% reported below that level. Just under half of the respondents (49%) were from Canada while 37% were from the USA with the balance from other parts of the world. Forty five percent of the respondents indicated they completed the survey on their own while 55% received help from another person, mainly a parent.

Table 1 reports the diagnostic categories.

Of the 371 who reported a diagnosis, 32% were diagnosed at 5 years of age or under; 20% from ages 6-10 years; 18% from 11-15 years; 13% from 16-19 years and the balance (16%) from age 20 and over. Such a wide range of chronological and developmental stages for assessment may impact expressions of both risk and protective factors.

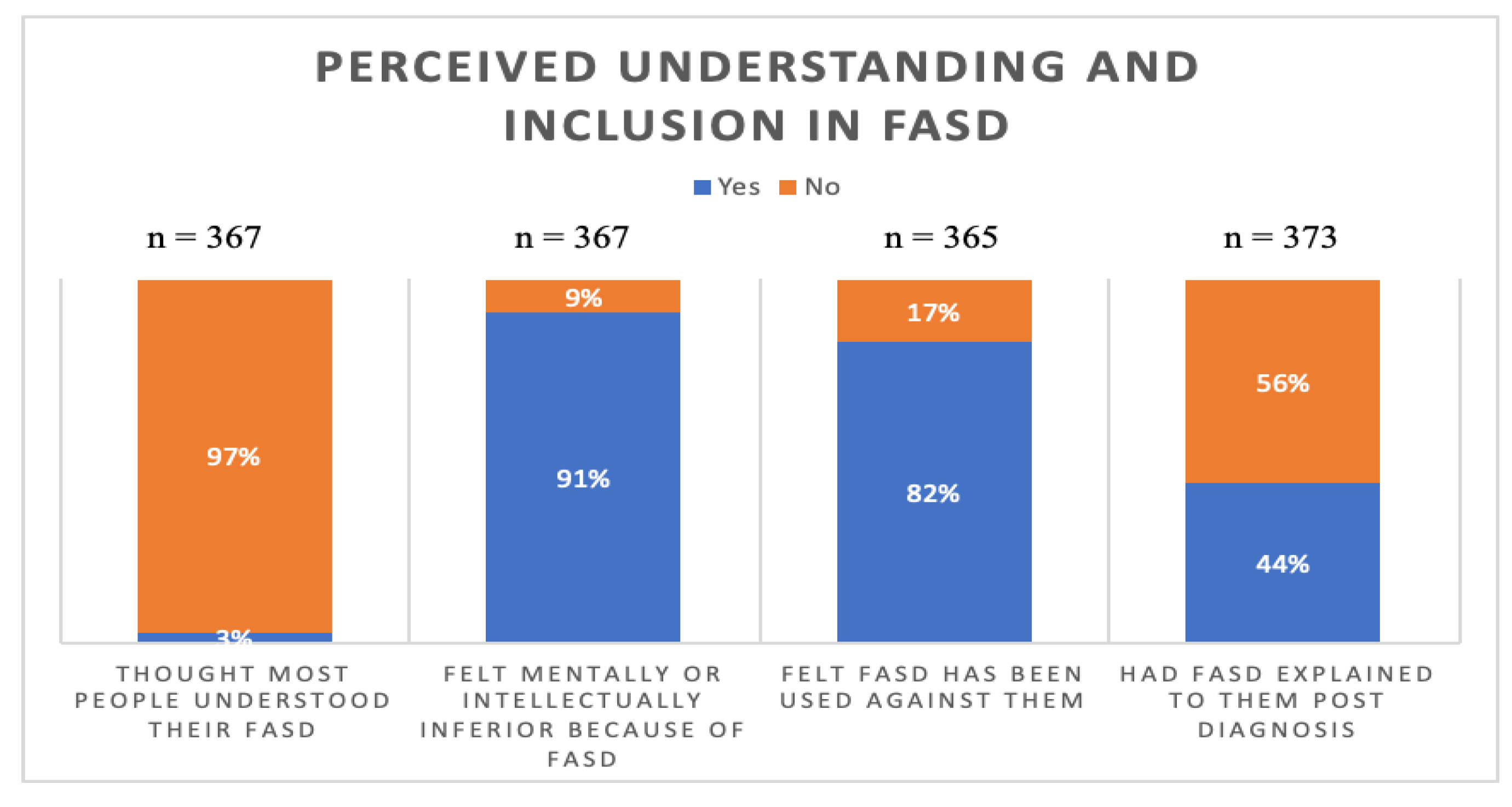

4.2. FASD Specifics

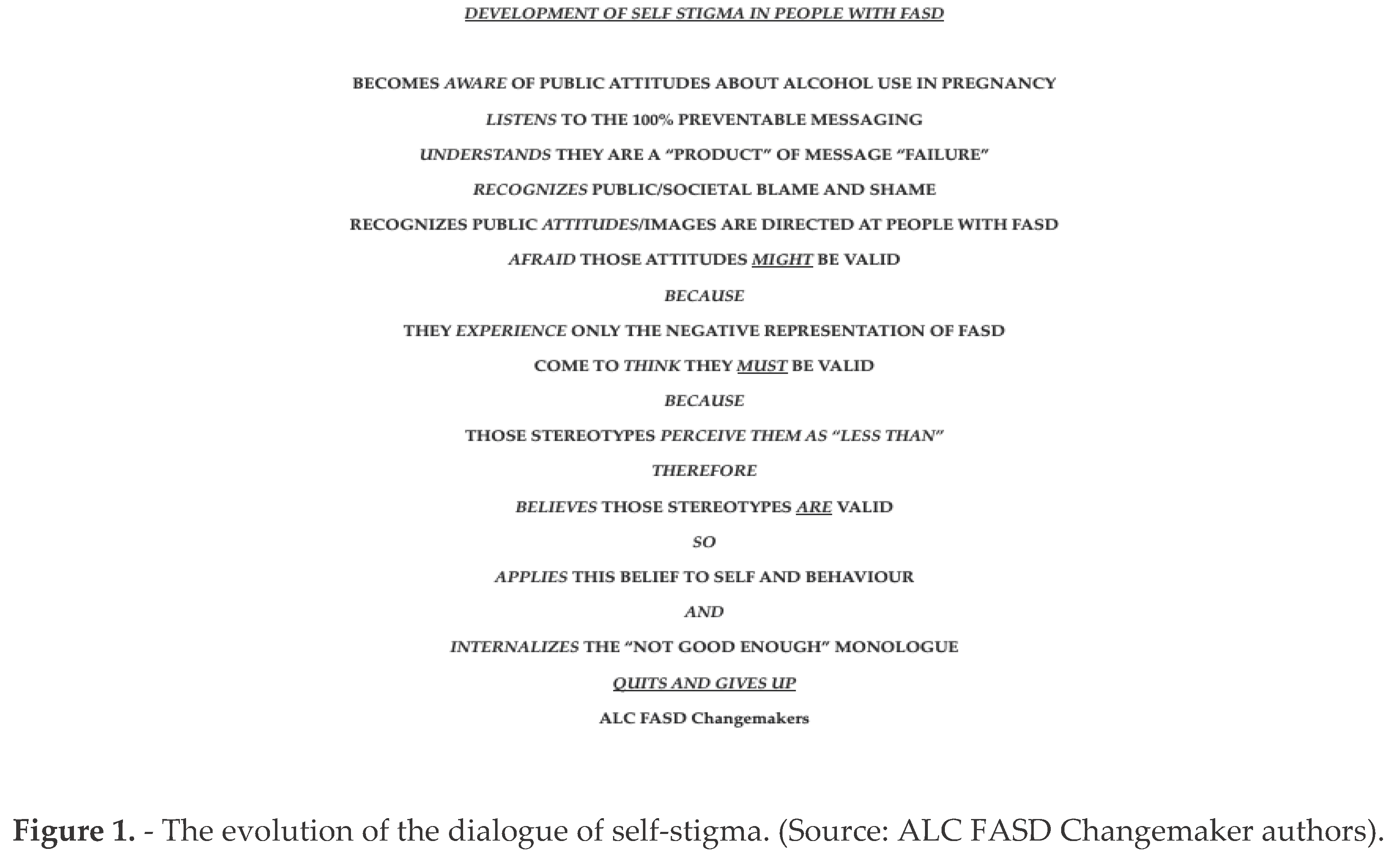

This section refers to survey questions which focus upon how respondents perceived being understood or misunderstood, included or excluded as well as the degree to which they had a sense of belonging. On average, responses reflected an overall sense of not being understood and more often being excluded. The responses also showed an internal sense of inferiority. One of the more worrying features is that the majority reported not having the FASD diagnosis explained to them post-diagnoses (see

Figure 1).

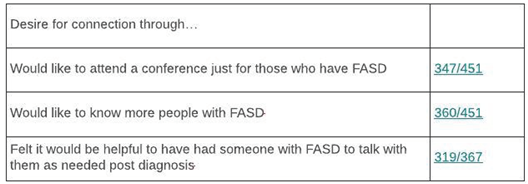

In

Table 2, respondents reported a desire for connection particularly with those who are also diagnosed. Having relationships with others facing similar life experiences can also be a way to have affirming connections to validate self-experiences and self-worth.

As noted above, adversity in childhood, can have a significant impact on functioning across the lifespan [

4,

5]. The following are some of the key findings concerning adversity across the lifespan. The following results show that respondents experience high levels of life adversity. These results are consistent with Flanigan et al. [

35] and Tan et al. [

36].

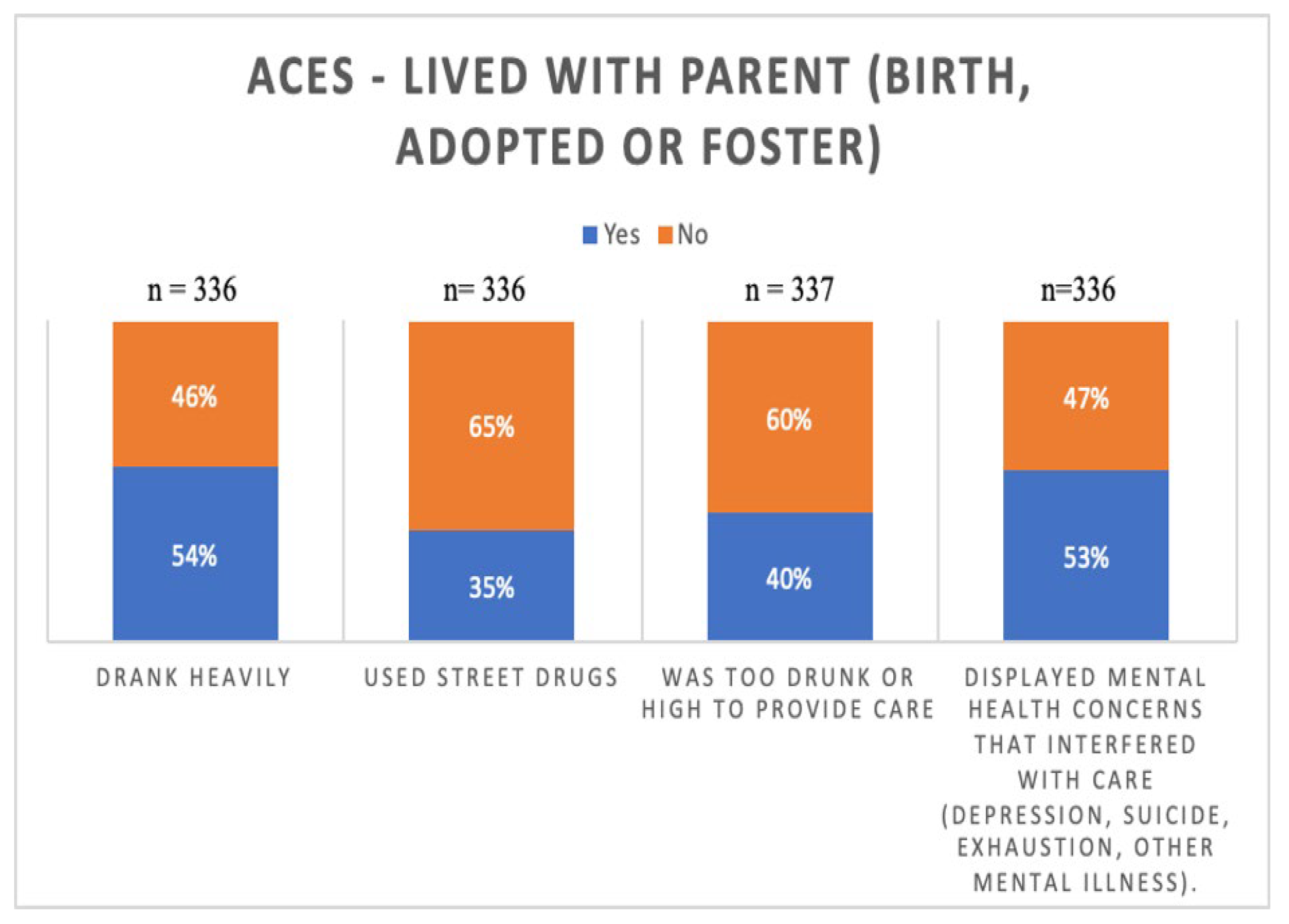

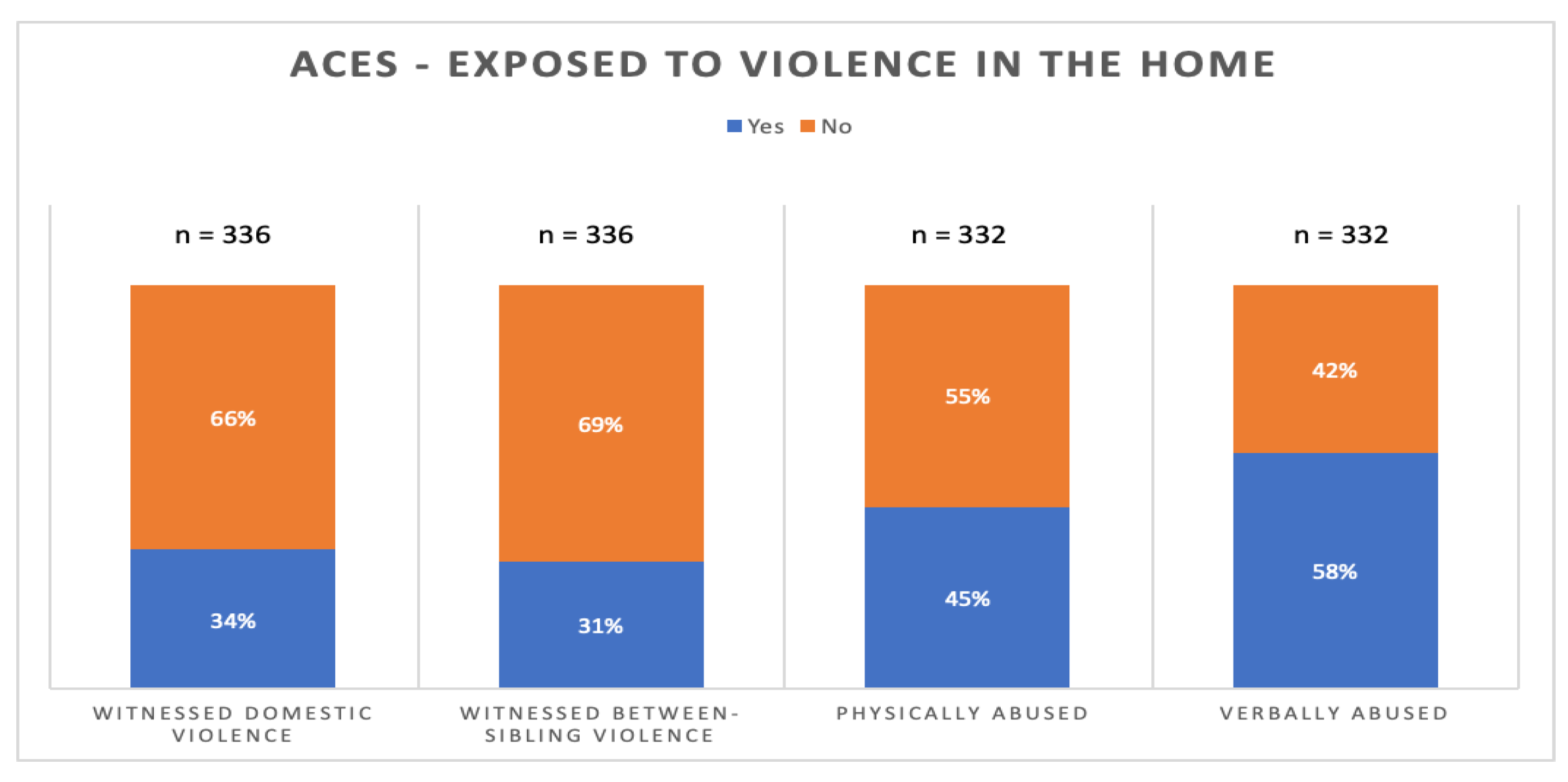

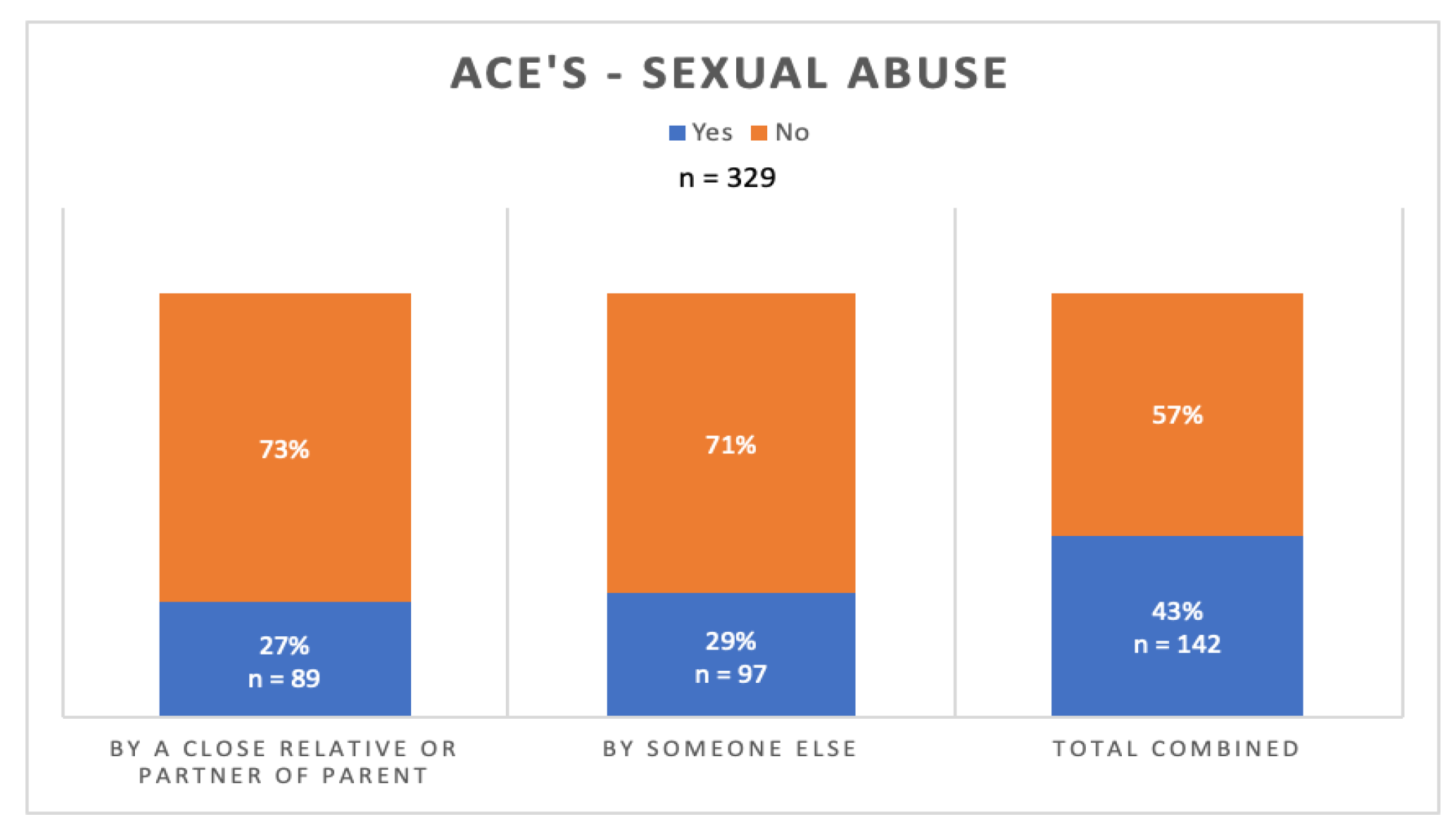

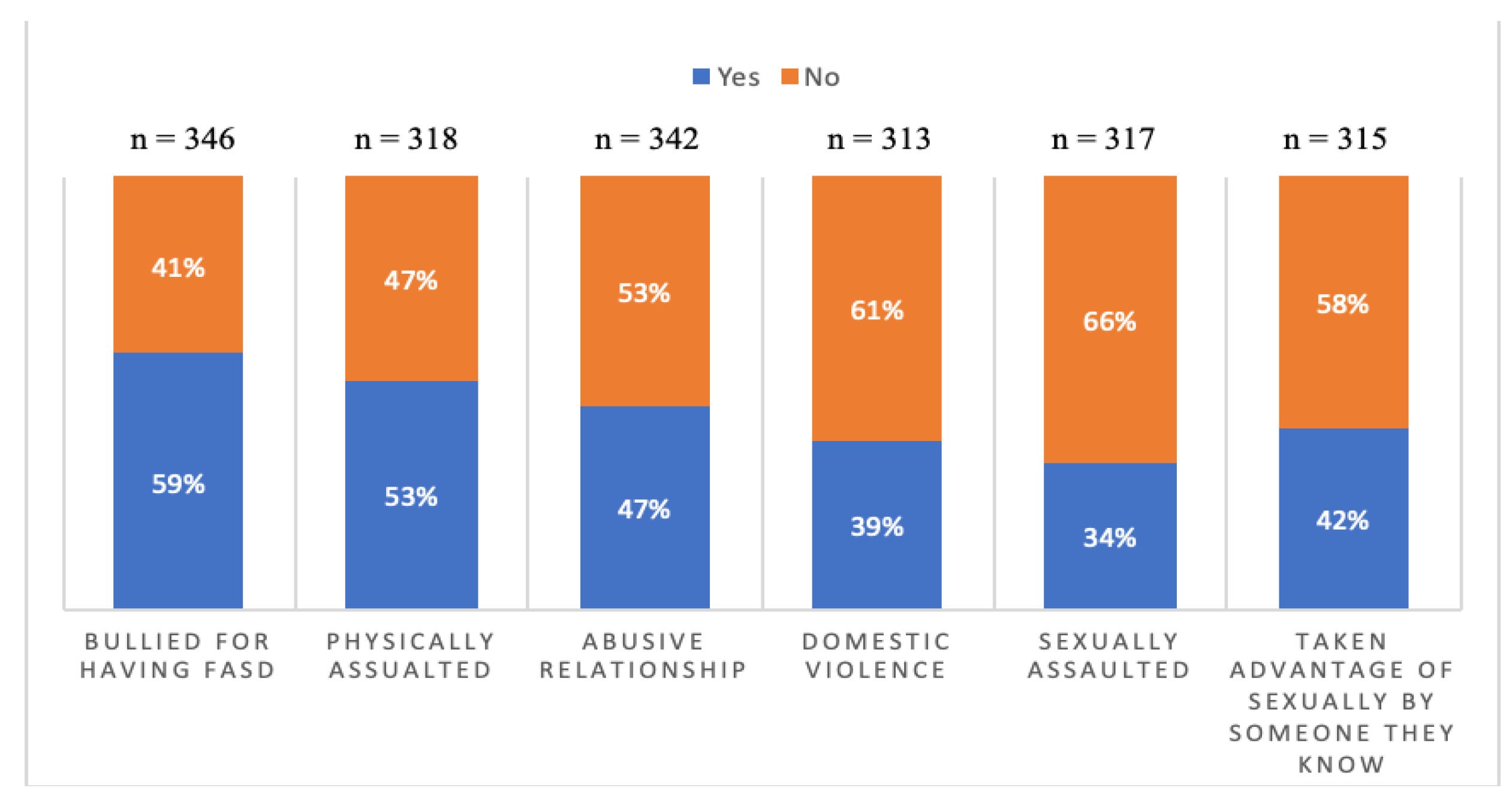

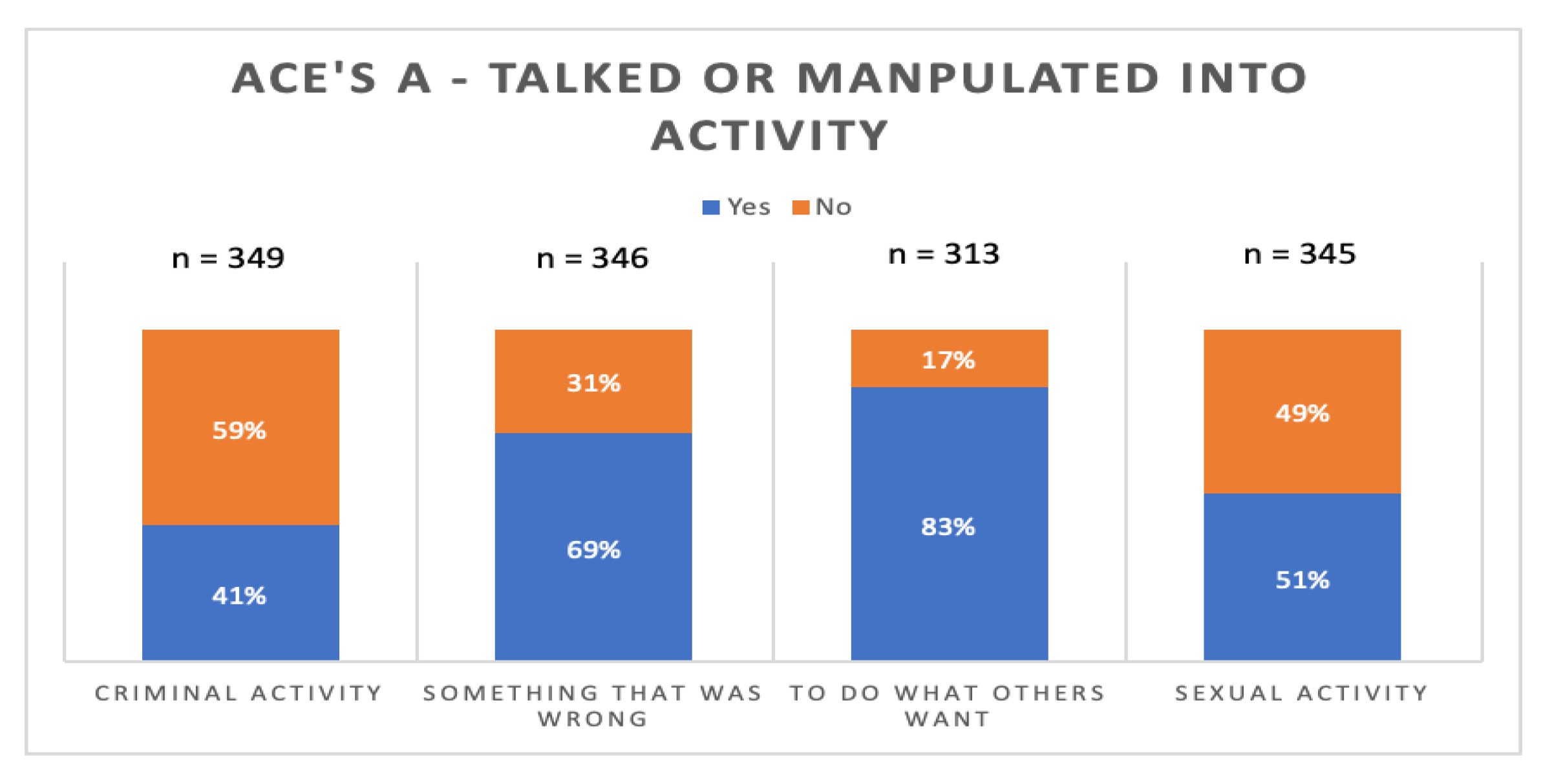

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate the prevalence of adversity. The most commonly reported adverse experience before 18 were verbal abuse (58%), lived with anyone in the home who drank alcohol heavily or was an alcoholic (54%), and who in a home with someone who was depressed, mentally ill, or attempted suicide (53%). After the age of 18, the most commonly reported adversities were being manipulated by others to do what they want (83%), intimidated or threatened (74%), and talked into doing something that was wrong (69%)

Figure 2 helps to see the linkages between caregiving experiences of substance abuse and mental health within the lives of respondents. Trauma from one generation to the next is an outcome of such exposures which has been documented throughout the population with FASD [

2]. Future research is needed to parse out these experiences to better understand the depth, duration, frequency and the presence of any protective factors. Such information has the potential to improve interventions.

As seen in

Figure 3, the majority of respondents have exposure to some form of interpersonal violence in the home environment although does noy include coercive control [

37]. This may be a rich area for exploration, particularly given the results noted later in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

Figure 4 shows what might best be described as an alarming rate of sexual abuse victimization within the respondent population at levels not typical of the population at large [

5,

36]. Several considerations arise from these results including how many of these cases have been disclosed. The vast majority of sexual abuse victims do not disclose. As well, given the data on manipulation in

Figure 6 below, further research in this area is needed. Disclosure might be as high as 1:5 across the lifespan as opposed to proximal to the event. Victimization in childhood raises the probabilities of such in adulthood [

36,

37]. Combined with increased risk for manipulation, this is worrying.

The data in

Figure 5 offers some more complex understanding of the rates of IPV. These results, along with others noted above, reinforce that persons with FASD are at much higher risks for victimization.

4.3. Education

Also related to quality of life is the participants’ education history. This survey gathered information on educational completion, educational support, and employment history related to post-secondary education. Of those who answered they attended high school or were currently in high school (n= 423), 26% at the time of survey or had attended a regular program without supports in high school, 32% at the time survey or had been enrolled in a regular program with an individual educational plan (IEP), and 40% were or had been enrolled in a special education program or school. Of those not currently in high school (n= 351), 29 percent did not finish high school (n=100), and 77% of those who did not finish (n=77) said they believed they could have if there would have been more help. Eighty-three percent of those surveyed no longer in high school said, looking back, they did not understand what was taught to them in class. Concerning post-secondary education, denoted by job skills programs, career training programs (i.e., technical and trade schools), and a college or university degree program, the survey asked if participants received a job followed by their current employment status. Of the 163 who said they attended a jobs skill program, 74% received a job and 31% still had a job. Of the 101 who attended a career training program, 67% completed the program, 45% got a job, and 26% still had a job. Finally, of the 155 who attended a college or university degree program, 48% graduated, 37% got and 18% still had a job in their area of study. This data highlights the need to support the education process over the long-term to enhance outcomes.

4.4. Employment

At the time of the survey 291/342 (49%) indicated being employed full or part time. They indicated they found working a struggle identifying such factors as being overwhelmed, worried about doing the job properly, too tired to do other things, deteriorating physical and/or mental health. The social relationships that form part of a work environment were often seen as stressful. Indeed the overall stress of being employed meant that 200/317 respondents reported they could only work part-time. 265/319 indicated they enjoyed working. 196/276 indicated they felt good, valuable and productive like others in society when they were working.

Consistent with the perception that being a person with FASD would often bring stigma, shame and/or fear, 195/315 reported they would keep the diagnosis secret from an employer and 137/253 reported not letting anyone at work know. 248/322 believed they would not or probably would not get hired if the employer knew of the FASD.

Being fired or laid off was a common experience, with 194/290 described this experience with 133/290 stating it had occurred 3 or more times. Quitting was also common with 220/286 having done so. 114/286 having done so 3 or more times. The common issues related to sustaining employment included: being overwhelmed, things going wrong in other parts of their life; worrying about doing the job properly; too tired to do other things; physical and/or mental health getting worse; and struggling to get along with co-workers. This also illustrates the need to engage employers understanding the nature of FASD and how to support the needs of employees with FASD.

Of the 142 employed at the time of completing the survey, 199 reported earning less than $1,500 per month.

4.5. Finances

Just over half of respondents (240/462) indicated they received some sort of financial assistance from a government. Of those, 216/240 indicated they received less than $1500 per month. Of those receiving such money, three quarters reported this was not enough to live on.

Not surprisingly, financial limitations also impacted having enough money to cover expenses over the course of a month, access to healthy food (as defined by the respondent) as well as difficulty affording medications. 302/388 indicated they regularly receive financial help from family or others to help address needs such as rent, groceries and phone bills. These financial limitations add to levels of dependency with only 1:5 being able to live independently. This highlights that social support systems are likely inadequate most of the time.

4.6. Housing Instability

The survey asked the respondents about their living situations (i.e., where they lived, how housing was paid, who they lived with, etc.). At the time of the survey, 21/419 were homeless. 114/439) had experienced eviction at some point. This was connected to challenges with paying rent with 155/ 407) not having enough money to pay the rent and 208/407 struggling to remember to pay their rent on their own each month.

4.7. Memory Issues

Respondents indicated a number of concerns arising from memory problems. Without help, common concerns were around remembering to take medications, pay bills and rent, take care of personal and household hygiene as well as eating.

Respondents described being unable to remember to do things without help such as paying the rent (188/ 369) or bills (233/319), taking medications (170/ 284) and refilling prescriptions (163/276), doing laundry (193/ 328,) or cleaning house (240/324). This need for help also includes personal hygiene: shower (98/326), clean teeth (178/ 325), wash hair (117/ 325), or groom hair daily (114/ 308).

4.8. Family

Only 61/323 respondents were raised by their birth family. Otherwise, they were raised in quite a variety of living situations. 85/323 reported one long term foster care while a similar number (84/323) reported being raised in a number of family and foster care arrangements creating significant instability. A further 102/323 described adoption. 292/353) have birth siblings although it is unclear what the long-term relationships with them might look like.

4.9. Partners

147/ 342 who responded were in a partner relationship at the time of the survey. Fourteen percent were married. Missing is a sense of the relational stability which would be worthy of further investigation.

4.10. Parenting

In terms of being a parent, 100/346 have children roughly split half and half with the child living or not living with the parent with FASD. The other living arrangements were with the other parent or family member; in foster care or have been adopted.

4.11. Friendships

In terms of friendships, 227/345 said it is hard to make friends while 282/345 indicated it is hard to keep friends. Being alone was preferred by 209/344. Being taken advantage of people they considered friends was described by 278/344 s which may be related to 258/344 indicating they decide too quickly as to who is a friend. For the respondents, they described that being with people is exhausting (264/342) and being with people also brings anxiety and nervousness (245/341). Making friends is difficult (66%) and 61% reported being happier alone. Half of the respondents had most of their social interactions on-line.

4.12. Criminal Justice

Involvement with criminal justice was fairly common. Of the 344 participants responding in this area, 134 have been arrested; (98 charged and 59 convicted some more than once). 25/344 reported they had been in a youth prison and 39/344 in an adult prison or jail. Respondents indicated a series of other challenges within the criminal justice system which included agreeing with the police even though they did not commit the crime; pleading guilty without understanding the consequences; being talked into committing crimes or forced in doing so which may be related to vulnerability arising out of the FASD.

Being a victim of a crime was common (184/342). The most common forms of victimization were from physical assault; sexual assault domestic violence; financial exploitation and being robbed or mugged. As an indicator of the vulnerability of a person with FASD, 135/183 answering stated they did not report the crime which may be related to a significant number (142/185) stating they have not been believed by the police in at least one encounter. Part of the challenge is being seen as a credible informant. Understanding the process is a further challenge with 163/250 stating that when they did have encounters with the police, they did not understand the process.

All of the results related to housing, employment finances, social relationships and involvement with the criminal justice system need to be considered with the earlier noted results related to adversity in childhood and adult years. These are intersectional.

5. What Could help

The respondents identified a variety of ways they can be supported. These include mental health clinicians and other health care practitioners who specialize in FASD. Those might be thought of as more formal supports but they also identified the informal supports such as trusted person to speak or act for them. In other words, people who are informed, trustworthy and listen.

For the person living with FASD, both formal and informal supports need to show they accept this person as one with their own hopes and dreams. Based upon the suggestions from 313 respondents, below are insights into how help might look and be structured provides the basis for needed policy discussion.

Access to a mental health clinician who specializes in FASD.

Availability of a doctor or nurse practitioner who knows about FASD.

A person who can help when something goes wrong.

A person who can be trusted to give advice when needed.

Enough money to meet monthly needs.

Help with tasks of daily living such as cleaning and laundry.

Having a trusted person who, with permission, can speak and act for the person with FASD.

Also a trusted person to manage or help with money so that the person with FASD is less likely to be taken advantage of. This may also include being able to attend appointments so that there is someone present to support the person’s understanding of what has been said and recommended.

Help to get and sustain employment (this would be a person who understands what is and is not possible).

The ability to engage in activities that are important to the person.

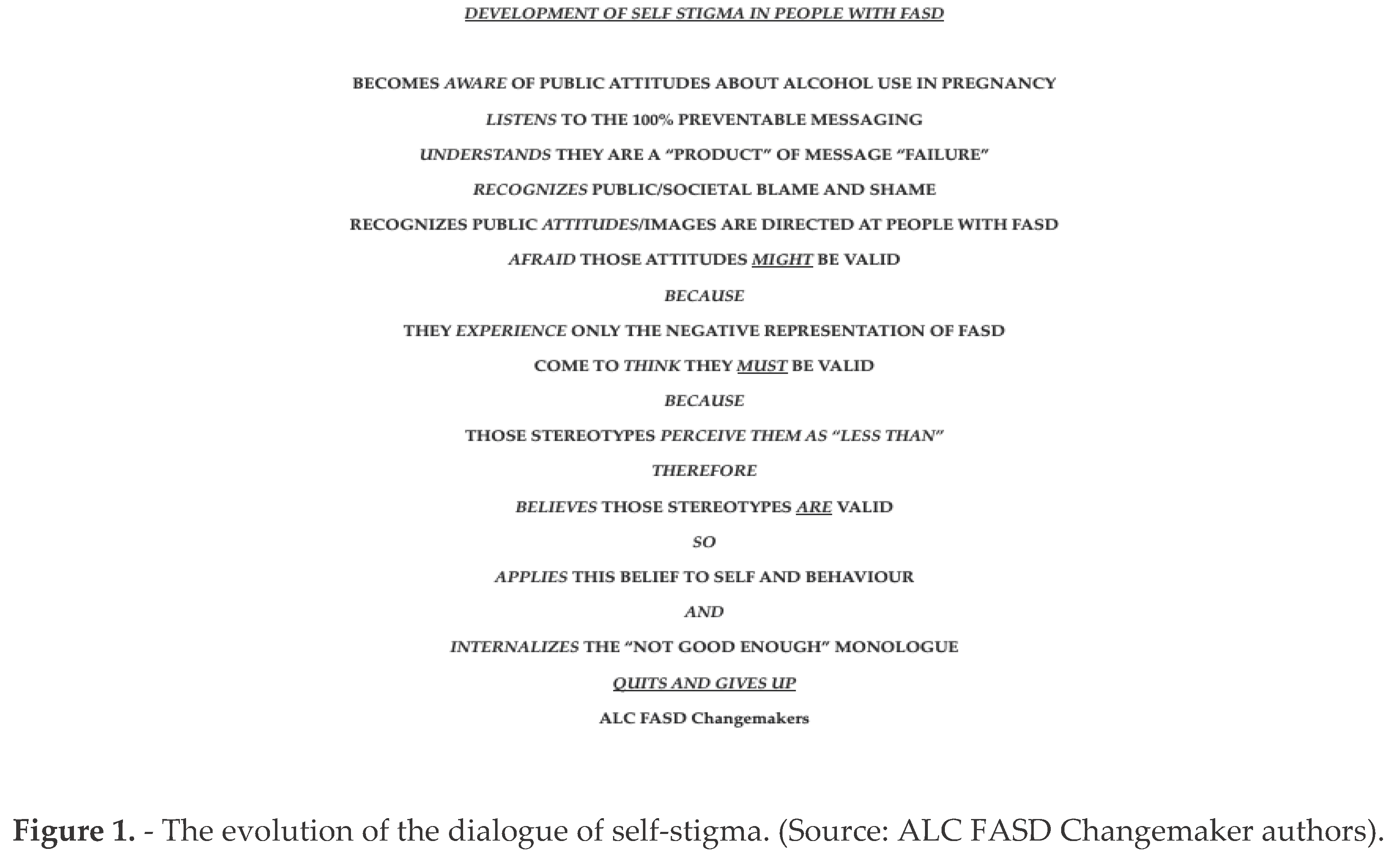

An area that might be considered arising from this data is ways in which a person living with FASD might frame themselves. This is an area for further research. However, as the chart below shows, the challenges with daily living can become incorporated into a dialogue of self-stigma as seen in Figure 1 below.

6. Discussion

Being diagnosed with FASD is a step in gaining recognition and understanding for the living experience. As can be seen with this data, the diagnosis is an explanation but it is not, in and of itself, a predictor of the life course. The data shows ongoing, significant challenges for which an individual is likely to need ongoing supports and connections across the lifespan. This includes having professionals who understand what FASD is about [

7].

This research was designed to explore quality of life among adults with an FASD, and it is important to note that the results of this study are meant to lay the groundwork for such richer and deeper research which might also focus upon more of the successes experienced which the members of the Adult Leadership Team frequently report in their conference presentations. Similarly, it sought to explore the concepts of adverse life experiences from childhood forward, capturing an initial understanding of continuing stress-correlated experiences that may exist in adulthood, and, if so, what are the reported rates. Previous, limited, research has explored ACEs in this same population, but, to the authors’ knowledge, adult experiences linked to childhood adversity have not been explored. What was notable were the rates of abuse, victimization, and homelessness not just before the age of 18, but after the age of 18. The adversity results illustrate, adverse experiences appear to indeed continue well into adulthood. Given that the average age of the respondent was 30 years old, this pathway of ongoing adversity negatively impacts the quality of life for adults living with FASD. Such patterns of ongoing adversity leading to intergenerational trauma (IGT) should be considered [

41]. This does not mean that all parents who have children with FASD are from a traumatized legacy. What we see in this data, however, is that many adults in the sample show IGT linkages. This is evident in the data.

This might be considered in terms of exclusion in society also seen in this data, such as believing they are misunderstood and being seen as intellectually and socially inferior. Social messaging within society and systems such as schools and jobs, combined with memory difficulties result in feeling ‘less than’. After the age of 18, several continuing experiences were explored and reported on the survey beyond abuse, such as being taken advantage of, intimated, or being talking into activity, revealing these to be areas of concern for an adult with FASD.

Yet, to use an incapacity lens limits the notion of what a person living with FASD might accomplish. As adults, many living with FASD pursue parenthood but are often quickly perceived as incapable thus coming to the attention of child protection [

42]. Once a person with FASD enters the child protection court system, they are almost always likely to lose custody of their children [

43] Nearly 74% report having children and, in spite of work-related stigma, many pursue employment with over half (62%) reporting they keep their diagnosis a secret from their employer. These are also areas for further research so that we better understand the complexity and depth of the life course experience.

As has been discussed above, being vulnerable to manipulation creates a number of risks of victimization as well as becoming involved in the criminal justice system where a person with FASD may struggle to explain their role effectively. When looked at as a cohesive set of data, the material illustrates the degree of exposure to trauma across the lifespan. There is a substantial body of work that shows trauma impacts a person in multiple ways (physical, emotional, socially for example) in ways that are both cumulative and persistent [

40,

41]. These are life experiences for which a person with FASD appears to be more vulnerable. This emphasizes the need for intervention, support and healthy connection on an ongoing basis.

This study lays the groundwork for richer exploration or understanding of what appear to be disparities and potentially higher levels of stress and lower levels of quality in life within the adult FASD population. ACEs such as trauma, abuse, neglect, etc., have been shown throughout the literature to negatively impact development across the lifespan [

42], but what happens as continuing adverse experiences happen in adulthood? What this survey demonstrated was high levels of reporting of the perception of stigma and lower levels of support. The key areas covered in this paper, from housing, education, employment, to criminal justice all indicate sub areas where services could be developed. This includes scaffolding of services over the life span. It is equally valid to prioritize dismantling systematic misunderstanding of what might be possible as opposed to the stigmas which serve as powerful barriers.

People living with FASD do not seek to hide their realities, rather they seek to have them known, even though they feel the need to hide their diagnosis in order to be given opportunities [

9,

20]. When they are allowed to be open or feel safe to do so, the genuineness of relationships with caregivers, professionals and the community at large remains very possible. They should also have the right to tell their story as it is

their story to tell [

46]. Stereotypes lead to stigmatization arising from the single story of incapacity which flattens the experiences, capacities and opportunities for persons with FASD [

8]. An alternative narrative is that people with FASD have the right to thrive [

22]. They also have the right to be heard, Reid et al. Many in the FASD community state “Nothing about us without us” [

18]. This informs the notion that people living with FASD offer valuable insights which serve to educate formal and informal support systems working in partnership with people with FASD.

As Aspler et al. [

1] note, stereotypes are powerful, persistent and create a narrowing view of the person. A balanced view of life matters so that support and interventions can be crafted to the reality of strengths, weaknesses and limitations and opportunities. The public perception of FASD is heavily driven by stereotypical presentations often seen in various forms of media [

8]. Regrettably, the narrow, stigmatized story of living with FASD becomes “

the” story which interferes with the ability for the living truth to be told and for people to have supportive places in society, FASD is also less accepted than other disabilities such as those with Autism Spectrum Disorder who also experience a range of behavioral, cognitive, emotional and physiological experiences [

8,

48] Family life is also impacted by FASD and ASD, although ASD will be seen as more receptive to intervention [

1,

47,

48].

In Vancouver, Canada, a series of international conferences regarding FASD were held from 1987-2019 which included an Adult Leadership Committee composed of individuals with FASD. COVID-19 disrupted holding the conferences which offer professional and academic presentations as well as opportunities for those with FASD to provide leadership, share living experiences, support research as well as connect. As can be seen from the results in

Table 2 above, these types of opportunities are sought and have a high probability of being pathways to better life course decision making. The conferences are returning in 2024 and will be held in Washington State.

7. Limitations

By definition, anonymous survey data has limitations. The respondents are self-selecting and may not be representative of the population with FASD. There is no verification of self-reported information and some respondents who believe they may have FASD could, if properly assessed, turn out to not have the diagnosis. In addition, there is no capacity to clarify, follow up or expand upon responses. The survey may not be representative of the population with FASD given that the survey required access to online platforms and technology. On the other hand, respondents can be quite sure that their information will remain anonymous. This protects them from accidental disclosure as well as limits the fear of embarrassment, shame or guilt that may arise from describing life experiences.

8. Areas for Future Research

This work opens up ways to think about living with FASD. It invites substantial follow up to dive deeper into the intersectional, complex experiences so that the texture and variations of living with FASD can be better understood. Qualitative work, which might include phenomenology, could add rich storytelling. Grounded theory approaches could thematically explore the stories while further quantitative work could add more detail to the areas explored here. While there is an IGT linkage found in the data, the data does not distinguish between a positive correlation between higher rates of IGT and higher rates of ACE’s-A. Further research would need to be conducted to answer such a question. Similarly, more research needs to be conducted to explore whether a lack of resources in adulthood exists, and if so, is there a relationship to ACE’s-A.

Future research might consider exploring coercive control as a factor given the growing body of work around this aspect of inter-personal violence (IPV), particularly Barrow & Walklate’s [

37] work showing that those with FASD are more vulnerable to manipulation, a core feature of coercive control.

Given the significant power of relationships, we need to better understand how to support adults with FASD when their parents / caregivers pass away. What support will then be available and how will individuals with FASD maneuver their way through complex systems with variable eligibility requirements?

Often missing from research agendas, is taking time to understand what works as the research is often deficit based. Understanding strengths-based perspectives would allow for a richer understanding of how people with FASD can intersect with systems without being prejudged.

Other research avenues might consider how to implement the ideas reraised in this work, validating, for example, systemic, life course interventions, impacts arising from education and other approaches to reducing stigma in the public and professional arenas. Other research might begin focusing upon altering the pathways to self-stigma.

One particular focus of future research is to continue to find ways to include the voices of those living with FASD. In particular, a more focused look at the capacities and strengths might be developed. Even so, this data allows a look into the challenges faced by those living with FASD and what must be managed on a daily basis. The challenges are not the whole story [

49] and the literature in that sphere is quite limited.

9. Conclusions

This anonymous survey data has opened up further understandings about living with FASD. In particular, it shows the degree to which Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adverse Adult Experiences are common. Highlighted as well is the vulnerability that can be seen in being manipulated and how that contributes further trauma to living with FASD.

Author Contributions

PC and EH wrote the preliminary and final submission versions of the paper. CJL, KG, MH, JM and AL conceived the original survey and arranged for making it available and gathering the data. They also did the original data analysis. PC and EH completed the secondary data analysis. All authors were engaged in reviewing, editing and recommending changes to the paper.

Funding

No funding was obtained to conduct this research.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aspler, J., Bogossian, B. & Racine, E. (2022) “It’s ignorant stereotypes”: Key stakeholder perspectives on stereotypes associated with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, alcohol, and pregnancy, Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 47:1, 53-64. [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, K., Pei, J., McLachlan, K., Harding, K., Mela, M., Cook, J., ... & McFarlane, A. (2022). Responding to the unique complexities of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 6712. [CrossRef]

- Loock, C., Elliott, E., & Cox, L. (2020). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Evidence, theory and current insights. In, A.L. Begun & M.M. Murray (Eds). Routledge handbook of social work and addictive behaviors. Chp. 11. Abingdon, Routledge.

- P.A. May, C.D. Chambers, W.O. Kalberg, J. Zellner, H. Feldman, D. Buckley, et al. Prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in 4 US communities JAMA the Journal of the American Medical Association, 319 (5) (2018), pp. 474-482. [CrossRef]

- S. Popova, S. Lange, K. Shield, L. Burd, J. Rehm Prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder among special subpopulations: A systematic review and meta-analysis Addiction, 114 (7) (2019), pp. 1150-1172. [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, K., Gill, K., Pei, J., Andrew, G., Rajani, H., McFarlane, A., et al. (2019). Deferred diagnosis in children assessed for fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Applied Neuropsychology Child, 8(3), 213–222. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, N., Bagley, K., Hewlett, N., Elliott, E. J., Pestell, C. F., Gullo, M. J., ... & Reid, N. (2023). Lived experiences of the diagnostic assessment process for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. online first. [CrossRef]

- Choate, P. and Badry, D. (2019), “Stigma as a dominant discourse in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder”, Advances in Dual Diagnosis, Vol. 12 No. 1/2, pp. 36-52. [CrossRef]

- Himmelreich, M., Lutke, C.J, & Travis Hargrove, E. (2020). The lay of the land: Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) as a whole-body diagnosis. In, A. Begun & M. Murray (Eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Social Work and Addictive Behaviors. Pp. 191-215. London: Routledge.

- Lemoine P, Harousseau H, Borteyru JP, Menuet JC. Les enfants de parents alcooliques. Anomalies observées à propos de 127 cas. Ouest Medical. 1968; 21:476–82.

- Brown JM, Bland R, Jonsson E, Greenshaw AJ. (2019). A Brief History of Awareness of the Link Between Alcohol and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Mar;64(3):164-168. [CrossRef]

- Jones, K. & Smith, D.W. (1972) Recognition of the Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in early infancy. The Lancet 2, 999-1001. [CrossRef]

- Jones, K., Smith, D., Ulleland, C., & Streissguth, A. (1973). Pattern of malformation in offspring of chronic alcoholic mothers. The Lancet, 301(7815), 1267-1271. [CrossRef]

- Centre for Disease Control. (2023/10/03). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/facts.html.

- Sessa, F., Salerno, M., Esposito, M., Di Nunno, N., Li Rosi, G., Roccuzzo, S., & Pomara, C. (2022). Understanding the Relationship between Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) and Criminal Justice: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 10(1), 84. MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Brown J, Harr D. (2018). Perceptions of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) at a Mental Health Outpatient Treatment Provider in Minnesota. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 21;16(1):16. [CrossRef]

- Currie, B.A.; Hoy, J.; Legge, L.; Temple, V.K.; Tahir, M. Adults with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: Factors Associated with Positive Outcomes and Contact with the Criminal Justice System. Journal of Population Therapetics and Clinical Pharmacology. 2016, 23, e37–e52. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, N., Dawe, S., Shelton, P., Harnett, P., Warner, J., Armstrong, E., LeGros, K., & O’Callaghan, S. (2015) Systematic Review of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Interventions Across the Life Span. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39 (12), 2283-2295. [CrossRef]

- Elder, G. H., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory (pp. 3-19). Springer US.

- Flannigan, K., Wrath, A., Ritter, C., McLachlan, K., Harding, K. D., Campbell, A., ... & Pei, J. (2021). Balancing the story of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: A narrative review of the literature on strengths. Alcoholism: Clinical and experimental research, 45(12), 2448-2464. [CrossRef]

- Dunbar Winsor, K. (2021). An invisible problem: Stigma and FASD diagnosis in the health and justice professions. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 14(1), 8-19. [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, K., Tremblay, M., Potts, S., Nelson, M., Brintnell, S., O’Riordan, T., ... & Pei, J. (2022). Understanding the needs of justice-involved adults with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder in an indigenous community. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 40(1), 129-143. [CrossRef]

- Flanigan, K., Harding, K., Pei, J., McLachlan, K., Mansfield, M., Cook, J. & McFarlane, A. (2020). The Unique Complexities of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. CanFASD. https://canfasd.ca/wp-content/uploads/publications/FASD-as-a-Unique-Disability-Issue-Paper-FINAL.pdf.

- McLachlan, K., Flannigan, K., Temple, V., Unsworth, K., & Cook, J. L. (2020). Difficulties in daily living experienced by adolescents, transition-aged youth, and adults with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 44(8), 1609-1624. [CrossRef]

- Coons-Harding, K.D.; Azulai, A.; McFarlane, A. State-of-the-art review of transition planning tools for youth with fetal alcohol Spectrum disorder in Canada. Journal on Developmental Disabilities 2019, 24, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS.(1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 14(4):245-58. [CrossRef]

- Kambeitz, C., Klug, M. G., Greenmyer, J., Popova, S., & Burd, L. (2019). Association of adverse childhood experiences and neurodevelopmental disorders in people with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) and non-FASD controls. BMC pediatrics, 19(1), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Badry, D., Marcellus, L., & Ferrer, I. (2018, April). FASD and child welfare practice–a focus on life course theory. In presentation at the 8th International Research Conference on Adolescents and Adults with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, Vancouver, BC, March (Vol. 20).

- Tortorelli, C., Badry, D., Choate, P., & Bagley, K. (2023). Ethical and Social Issues in FASD. In Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: A Multidisciplinary Approach (pp. 363-384). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Burnside, L.; Fuchs, D. Bound by the clock: The experiences of youth with FASD transitioning to adulthood from child welfare care. First Peoples Child & Family Review 2013, 8, 40–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dugas, E. N., Poirier, M., Basque, D., Bouhamdani, N., LeBreton, L., & Leblanc, N. (2022). Canadian clinical capacity for fetal alcohol spectrum disorder assessment, diagnosis, disclosure and support to children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open, 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, C. L., & Kautz-Turnbull, C. (2021). From surviving to thriving: A new conceptual model to advance interventions to support people with FASD across the lifespan. In International review of research in developmental disabilities (Vol. 61, pp. 39-75). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Binnie, Ian (2018). FASD and the Denial of Equality. In Ian Binnie, Sterling Clarren & Egon Jonsson (eds.), Ethical and Legal Perspectives in Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: Foundational Issues. Springer Verlag. pp. 23-35.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, TriCouncil Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, December 2022.

- Flannigan, K., Kapasi, A., Pei, J., Murdoch, I., Andrew, G., & Rasmussen, C. (2021). Characterizing adverse childhood experiences among children and adolescents with prenatal alcohol exposure and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Child Abuse & Neglect, 112. [CrossRef]

- Tan, G. K. Y., Symons, M., Fitzpatrick, J., Connor, S. G., Cross, D., & Pestell, C. F. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences associated stressors and comorbidities in children and youth with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder across the justice and child protection settings in Western Australia. BMC pediatrics, 22(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Barlow, C., & Walklate, S. (2022). Coercive control. Routledge.

- Greenspan, S., & Driscoll, J. H. (2015). Why people with FASD fall for manipulative ploys: Ethical limits of interrogators’ use of lies. In Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in Adults: Ethical and Legal Perspectives: An overview on FASD for professionals (pp. 23-38). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Barrios, V. R., & Caspi, J. (2022). Disclosing sexual assault: Understanding the culture of nondisclosure. In R. Geffner, J. W. White, L. K. Hamberger, A. Rosenbaum, V. Vaughan-Eden, & V. I. Vieth (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal violence and abuse across the lifespan: A project of the National Partnership to End Interpersonal Violence Across the Lifespan (NPEIV) (pp. 3673–3690). Springer Nature Switzerland AG. [CrossRef]

- Spinazzola, J., van der Kolk, B. and Ford, J.D. (2021), Developmental Trauma Disorder: A Legacy of Attachment Trauma in Victimized Children. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34: 711-720. [CrossRef]

- Hamai, T.A., Felitti, V.J. (2022). Adverse Childhood Experiences: Past, Present, and Future. In: Geffner, R., White, J.W., Hamberger, L.K., Rosenbaum, A., Vaughan-Eden, V., Vieth, V.I. (eds) Handbook of Interpersonal Violence and Abuse Across the Lifespan. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Badry, D., Dearman, A.H., Choate, P., Marcellus, L., Tortorelli, C., & Williams, W. (2023). FASD and child welfare. In, O.A. Abdul-Rahman & C.L.M. Peterenko (Eds). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: A multidisciplinary approach. pp. 385-404. Cham, SW; Springer.

- Choate, P.; Tortorelli, C.; Aalen, D.; Beck, J.; McCarthy, J.; Moreno, C.; Santhuru, O. Parents with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder within Canada’s Child Protection Trials. Canadian Family Law Quarterly 2020, 39, 283–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kautz-Turnbull, C., Rockhold, M., Handley, E. D., Olson, H. C., & Petrenko, C. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and their effects on behavior. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 47(3), 577-588. [CrossRef]

- Tortorelli, C., Choate, P. & Badry, D. (2023). Disrupted life narratives of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: Whose story is it? In, W.B. Gibbard (Ed). Developments in neuroethics and bioethics. (pp, 121-144). Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Reid, N., & Moritz, K. M. (2019). Caregiver and family quality of life for children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Research in developmental disabilities, 94. [CrossRef]

- Mazefsky, C. A., Herrington, J., Siegel, M., Scarpa, A., Maddox, B. B., Scahill, L., & White, S. W. (2013). The role of emotion regulation in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(7), 679-688. [CrossRef]

- Yorke, I., White, P., Weston, A., Rafla, M., Charman, T., & Simonoff, E. (2018). The association between emotional and behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder and psychological distress in their parents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 48, 3393-3415. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, K., Harding, K., Reid, D & Family Advisory Committee. (2018). Strengths among individuals with FASD. CanFASD. https://canfasd.ca/wp-content/uploads/publications/Strengths-Among-Individuals-with-FASD.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).