Submitted:

08 March 2024

Posted:

08 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Patients

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Research Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of patients

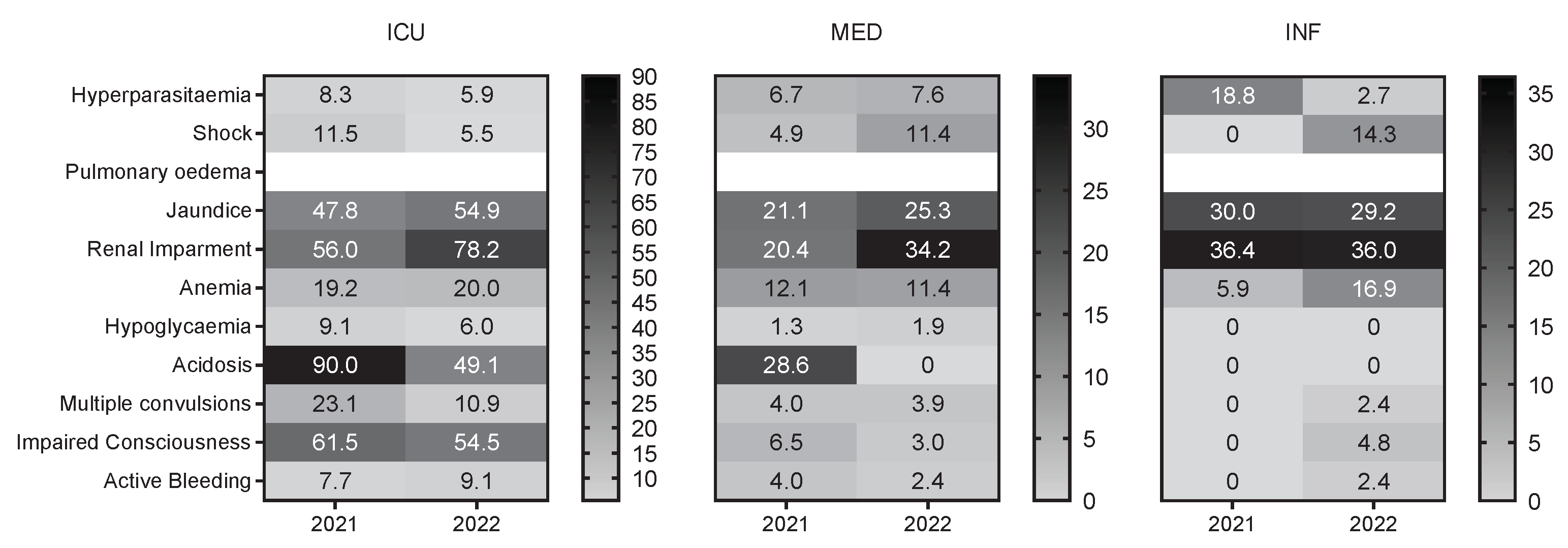

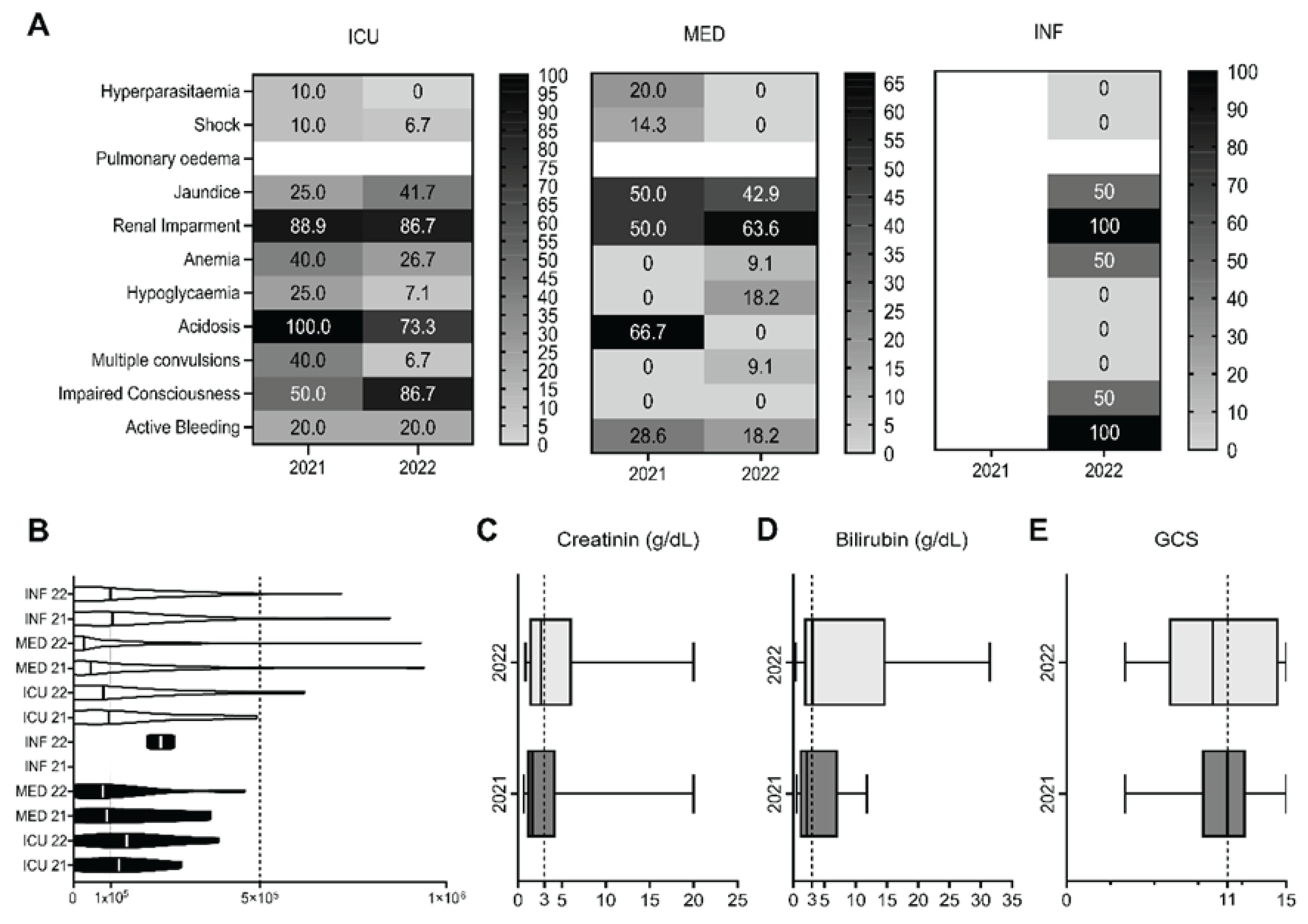

3.2. Clinical manifestations of severe malaria patients

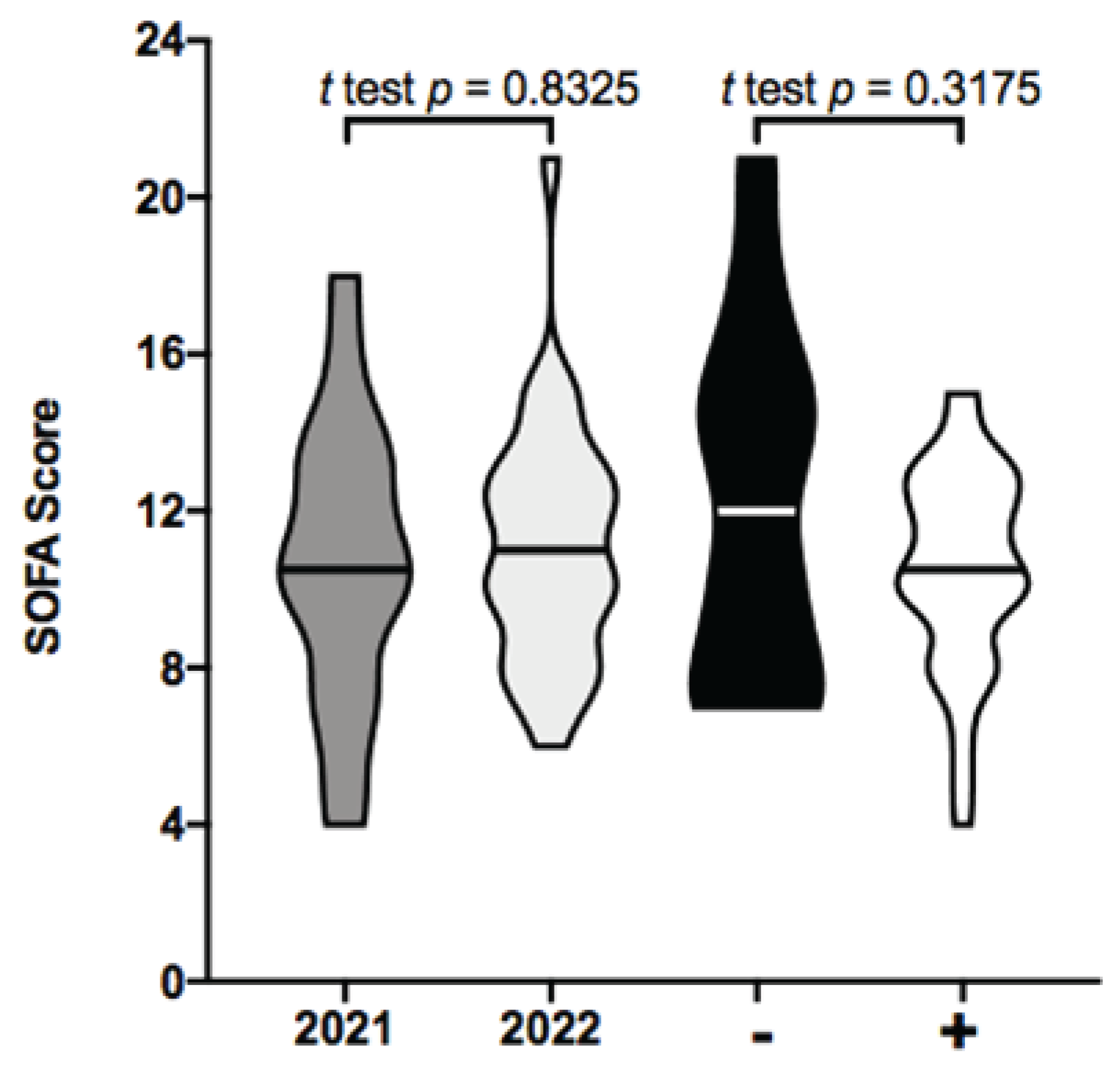

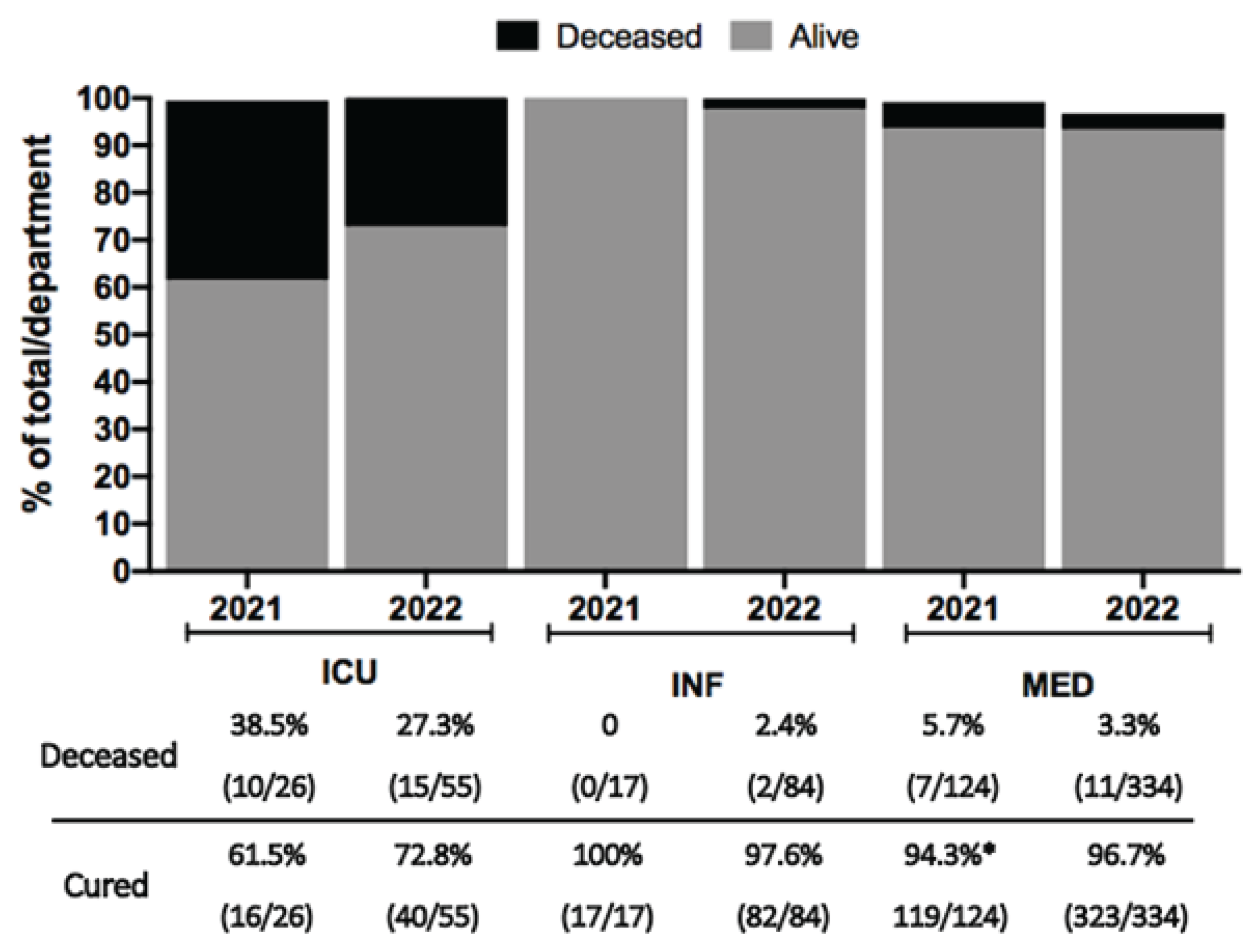

3.3. Clinical manifestations of severe malaria and outcome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- impaired consciousness (Glasgow score, GCS < 11), prostration (generalized weakness so that the person is unable to sit, stand or walk without assistance);

- multiple convulsions (more than two episodes within 24h);

- hypoglycaemia (blood or plasma glucose < 40 mg/dL);

- anemia (hemoglobin concentration < 7 g/dL or a haematocrit of < 20% in adults, with a parasites count > 10000/µl of blood);

- renal impairment (plasma or serum creatinine > 3 mg/dL or blood urea > 20 mmol/L);

- jaundice (plasma or serum bilirubin > 3 mg/dL, with a parasites count > 10000/µl);

- pulmonary oedema (radiologically confirmed or oxygen saturation < 92% on room air with a respiratory rate > 30/min, often with chest indrawing and crepitations on auscultation);

- significant bleeding (recurrent or prolonged bleeding from the nose, gums or venipuncture sites, hematemesis or melaena);

- shock (compensated shock: capillary refill ≥ 3 seconds or temperature gradient on leg (mid to proximal limb), no hypotension;

- decompensated shock (systolic blood pressure < 80 mmHg in adults, with evidence of impaired perfusion);

- hyperparasitaemia (10% or > 500,000 parasites/μl). Metabolic acidosis (a base deficit of > 8 mEq/L or, if not available, a plasma bicarbonate level of < 15 mmol/L or venous plasma lactate ≥ 5 mmol/l).

References

- World Health Organization. World malaria report 2023. In: World malaria report 2023. 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240086173 Accessed 4 December 2023.

- Huntley BJ. Angola in Outline: Physiography, Climate and Patterns of Biodiversity [Internet]. In: Huntley BJ, Russo V, Lages F, Ferrand N, editors. Biodiversity of Angola: Science & Conservation: A Modern Synthesis. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019 [cited 2023 10]. p. 15–42. [CrossRef]

- Tavares, W.; Morais, J.; Martins, J.F.; Scalsky, R.J.; Stabler, T.C.; Medeiros, M.M.; Fortes, F.J.; Arez, A.P.; Silva, J.C. Malaria in Angola: recent progress, challenges and future opportunities using parasite demography studies. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for malaria, 16 October 2023. World Health Organization; 2023. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/373339/WHO-UCN-GMP-2023.01-Rev.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1 Accessed 4 December 2023.

- White, N.J. Severe malaria. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.T.; Hollingsworth, T.D.; Reyburn, H.; Drakeley, C.J.; Riley, E.M.; Ghani, A.C. Gradual acquisition of immunity to severe malaria with increasing exposure. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20142657–20142657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyburn, H.; Mbatia, R.; Drakeley, C.; Bruce, J.; Carneiro, I.; Olomi, R.; Cox, J.; Nkya, W.M.M.M.; Lemnge, M.; Greenwood, B.M.; et al. Association of Transmission Intensity and Age With Clinical Manifestations and Case Fatality of Severe Plasmodium falciparum Malaria. JAMA 2005, 293, 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittaye, S.O.; Jagne, A.; Jaiteh, L.E.; Nadjm, B.; Amambua-Ngwa, A.; Sesay, A.K.; Singhateh, Y.; Effa, E.; Nyan, O.; Njie, R. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of severe malaria in adult patients admitted to a tertiary hospital in the Gambia. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuph, R.; Sawe, H.R.; Nkondora, P.N.; Mfinanga, J.A. Profile and outcomes of patients with acute complications of malaria presenting to an urban emergency department of a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debash, H.; Bisetegn, H.; Ebrahim, H.; Tilahun, M.; Dejazmach, Z.; Getu, N.; Feleke, D.G. Burden and seasonal distribution of malaria in Ziquala district, Northeast Ethiopia: a 5-year multi-centre retrospective study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, J.; Jespersen, J.S.; Seydel, K.B.; Szestak, T.; Mbewe, M.; Chisala, N.V.; Phula, P.; Wang, C.W.; E Taylor, T.; A Moxon, C.; et al. Cerebral malaria is associated with differential cytoadherence to brain endothelial cells. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M.L.; Seixas, J.; Ferreira, H.E.; Silva, M.S. Adequacy of Severe Malaria Markers and Prognostic Scores in an Intensive Care Unit in Luanda, Angola: A Clinical Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT. Economic and social impact of COVID-19 in Angola 2021. 2022; https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/aldcinf2021d6_en.pdf. Accessed 5 December 2023.

- Awucha, N.E.; Janefrances, O.C.; Meshach, A.C.; Henrietta, J.C.; Daniel, A.I.; Chidiebere, N.E. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Consumers’ Access to Essential Medicines in Nigeria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 1630–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittaye, S.O.; Jagne, A.; Jaiteh, L.E.S.; Amambua-Ngwa, A.; Sesay, A.K.; Ekeh, B.; Nadjm, B.; Ramirez, W.E.; Ramos, A.; Okeahialam, B.; et al. Malaria in adults after the start of Covid-19 pandemic: an analysis of admission trends, demographics, and outcomes in a tertiary hospital in the Gambia. Malar. J. 2023, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinamon, K.; Watson, J.A.; Silamut, K.; Intharabut, B.; Phu, N.H.; Diep, P.T.; Lyke, K.E.; Fanello, C.; von Seidlein, L.; Chotivanich, K.; et al. The prognostic and diagnostic value of intraleukocytic malaria pigment in patients with severe falciparum malaria. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, K.C.; for Southeast Asia Infectious Disease Clinical Research Network; Lau, C.-Y.; Chau, N.V.V.; West, T.E.; Limmathurotsakul, D. Utility of SOFA score, management and outcomes of sepsis in Southeast Asia: a multinational multicenter prospective observational study. J. Intensiv. Care 2018, 6, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Teparrukkul, P.; Hantrakun, V.; Imwong, M.; Teerawattanasook, N.; Wongsuvan, G.; Day, N.P.; Dondorp, A.M.; West, T.E.; Limmathurotsakul, D. Utility of qSOFA and modified SOFA in severe malaria presenting as sepsis. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0223457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, K.E.; Seymour, C.W.; Aluisio, A.R.; Augustin, M.E.; Bagenda, D.S.; Beane, A.; Byiringiro, J.C.; Chang, C.-C.H.; Colas, L.N.; Day, N.P.J.; et al. Association of the Quick Sequential (Sepsis-Related) Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) Score With Excess Hospital Mortality in Adults With Suspected Infection in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA 2018, 319, 2202–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkumama, I.N.; O’meara, W.P.; Osier, F.H. Changes in Malaria Epidemiology in Africa and New Challenges for Elimination. Trends Parasitol. 2016, 33, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boushab, B.M.; Salem, M.S.O.A.; Boukhary, A.O.M.S.; Parola, P.; Basco, L. Clinical Features and Mortality Associated with Severe Malaria in Adults in Southern Mauritania. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poespoprodjo, J.R.; Douglas, N.M.; Ansong, D.; Kho, S.; Anstey, N.M. Malaria. Lancet 2023, 402, 2328–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plucinski, M.M.; Ferreira, M.; Ferreira, C.M.; Burns, J.; Gaparayi, P.; João, L.; da Costa, O.; Gill, P.; Samutondo, C.; Quivinja, J.; et al. Evaluating malaria case management at public health facilities in two provinces in Angola. Malar. J. 2017, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariuki, S.M.; Abubakar, A.; Newton, C.R.; Kihara, M. Impairment of executive function in Kenyan children exposed to severe falciparum malaria with neurological involvement. Malar. J. 2014, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, M.J.; Bangirana, P.; Byarugaba, J.; Opoka, R.O.; Idro, R.; Jurek, A.M.; John, C.C. Cognitive Impairment After Cerebral Malaria in Children: A Prospective Study. PEDIATRICS 2007, 119, e360–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birbeck, G.L.; Glover, S.J.; Beare, N.; Taylor, T.E.; Molyneux, M.E.; Kaplan, P.W.; Lewallen, S. Identification of Malaria Retinopathy Improves the Specificity of the Clinical Diagnosis of Cerebral Malaria: Findings from a Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 82, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idro, R.; Marsh, K.; John, C.C.; Newton, C.R.J. Cerebral Malaria: Mechanisms of Brain Injury and Strategies for Improved Neurocognitive Outcome. Pediatr. Res. 2010, 68, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, A.L.; Opoka, R.O.; Bangirana, P.; Idro, R.; Ssenkusu, J.M.; Datta, D.; Hodges, J.S.; Morgan, C.; John, C.C. Acute kidney injury is associated with impaired cognition and chronic kidney disease in a prospective cohort of children with severe malaria. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namazzi, R.; Opoka, R.; Datta, D.; Bangirana, P.; Batte, A.; Berrens, Z.; Goings, M.J.; Schwaderer, A.L.; Conroy, A.L.; John, C.C. Acute Kidney Injury Interacts With Coma, Acidosis, and Impaired Perfusion to Significantly Increase Risk of Death in Children With Severe Malaria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namazzi, R.; Batte, A.; Opoka, R.O.; Bangirana, P.; Schwaderer, A.L.; Berrens, Z.; Datta, D.; Goings, M.; Ssenkusu, J.M.; Goldstein, S.L.; et al. Acute kidney injury, persistent kidney disease, and post-discharge morbidity and mortality in severe malaria in children: A prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 44, 101292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, A.L.; Datta, D.; Hoffmann, A.; Wassmer, S.C. The kidney–brain pathogenic axis in severe falciparum malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2023, 39, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickson, M.R.; Conroy, A.L.; Bangirana, P.; Opoka, R.O.; Idro, R.; Ssenkusu, J.M.; John, C.C. Acute kidney injury in Ugandan children with severe malaria is associated with long-term behavioral problems. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0226405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangirana, P.; Conroy, A.L.; Opoka, R.O.; Hawkes, M.T.; Hermann, L.; Miller, C.; Namasopo, S.; Liles, W.C.; John, C.C.; Kain, K.C. Inhaled nitric oxide and cognition in pediatric severe malaria: A randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0191550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-W.; Deng, D.-W.; Wei, C.; Zhou, X.-W.; Li, J.-X. Treatment-seeking behaviours of malaria patients versus non-malaria febrile patients along China-Myanmar border. Malar. J. 2023, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirak, S.; Fola, A.A.; Worku, L.; Biadgo, B. Malaria parasitemia and its association with lipid and hematological parameters among malaria-infected patients attending at Metema Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Pathol. Lab. Med. Int. 2016, ume 8, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampah, D.A.; Yeo, T.W.; Malloy, M.; Kenangalem, E.; Douglas, N.M.; Ronaldo, D.; Sugiarto, P.; Simpson, J.A.; Poespoprodjo, J.R.; Anstey, N.M.; et al. Severe Malarial Thrombocytopenia: A Risk Factor for Mortality in Papua, Indonesia. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 211, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, J.; Phu, N.H.; Hasan, M.U.; Charunwatthana, P.; Plewes, K.; Maude, R.J.; Prapansilp, P.; Kingston, H.W.; Mishra, S.K.; Mohanty, S.; et al. The clinical implications of thrombocytopenia in adults with severe falciparum malaria: a retrospective analysis. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiiba, J.-D.I.; Ahmadu, P.U.; Naamawu, A.; Fuseini, M.; Raymond, A.; Osei-Amoah, E.; Bobrtaa, P.C.; Bacheyie, P.P.; Abdulai, M.A.; Alidu, I.; et al. Thrombocytopenia a predictor of malaria: how far? J. Parasit. Dis. 2022, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legros, F.; Bouchaud, O.; Ancelle, T.; Arnaud, A.; Cojean, S.; Le Bras, J.; Danis, M.; Fontanet, A.; Durand, R.; Epidemiology, A.M.; et al. Risk Factors for Imported FatalPlasmodium falciparumMalaria, France, 1996–2003. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njuguna, P.; Newton, C. Management of severe falciparum malaria. . 2004, 50, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| 2021 | 2022 | ||||||

|

ICU % |

MED % |

INF % |

ICU % |

MED % |

INF % |

||

| Sex | Female | 19.2 (5/26) | 47.6 (59/124) | 52.9 (9/17) | 21.8 (12/55) | 44.9 (150/334) | 29.8 (25/84) |

| Male | 80.8 (21/26) | 52.4 (65/124) | 47.1 (8/17) | 78.2 (43/55) | 55.1 (184/334) | 70.2 (59/84) | |

| Age group | 14 - 18 | 7.7 (2/26) | 15.3 (19/124) | 5.9 (1/17) | 12.7 (7/55) | 11.4 (38/334) | 19.0 (16/84) |

| 18 - 60 | 84.6 (22/26) | 78.2 (97/124) | 88.2 (15/17) | 83.7 (46/55) | 82.0 (274/334) | 75.0 (63/84) | |

| ≥ 60 | 7.7 (2/26) | 6.5 (8/124) | 5.9 (1/17) | 3.6 (2/55) | 6.6 (22/334) | 6.0 (5/84) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).