1. Introduction

Incidents of violence are a frequently occurring phenomenon in the working life of nurses. Workplace bullying is a type of violence, which can take the form of persistent negative mistreatment, consisting of frequent and constant criticism and person-related physical, verbal, or psychological violence [

1,

2]. Any conflict or confrontation in the workplace does not constitute bullying, which has certain defining characteristics. These include, the fact that the employee is systematically targeted (by peers, superiors or even subordinates) by becoming the subject of negative and unwanted social behavior in the workplace, this targeting lasts for a long period of time and the victim of this behavior cannot easily escape the situation, nor stop the unwanted treatment [

3]. It is estimated that at least one in 10 healthcare professionals is a victim of workplace bullying [

4,

5], while the prevalence among nurse varies between 2.4% and 94% [

6,

7]. A systematic review of qualitative studies highlighted the “faces” of nurses’ bullying, where they indicated that they had experienced from being excluded and isolated to facing verbal abuse and hostility, to being excessively scrutinised, silenced, oppressed and threatened by those of power. They also reported being trapped in a system of intimidation, being provided with limited career opportunities and having their reputation damaged [

8].

The factors that trigger the occurrence of bullying in the working environment of nurses are mostly related to organizational issues. In particular, work characteristics of the nursing profession, such as work overload, shift work, job demands, severe staff shortages and stress, were found to be associated with the development of bullying behavior [

9,

10]. Also, supervisors lack of the adequate skills to manage bullying incidents and support victims, lack of organizational support as well as support from colleagues, disruptive working relationships, tolerance of bullying incidents, lack of policies on bullying and lack of prevention measures are some of the most important antecedents for the occurrence of bullying incidents among nursing staff [

9,

10]. The effects of bullying are multidimensional and affect nurses, patients and the functioning of the organization. Nurses who are bullied are more likely to experience stress, burnout, job dissatisfaction, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, low self-esteem, physical health symptoms and deterioration in the quality of their work life [

9,

11,

12]. Patients who are hospitalized in departments where nursing staff experience bullying may experience errors and adverse events, and may not receive comprehensive nursing care [

13,

14,

15]. At the organizational level, nurses' relationships are disrupted as barriers to teamwork and communication are developing due to bullying incidents [

13]. Also, high rates of absenteeism of nurses from work are recorded, they have a reduced commitment to the organization and report their turnover intention [

6,

16,

17].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a new phenomenon emerged among employees, that of quiet quitting, which was even presented on the video creation and sharing platform, Tik Tok [

18]. Employees who opt for quiet quitting are not resigning from their job or their profession, but are reducing their performance. Specifically, they perform the minimum requirements of their job, barely enough to avoid being fired, do not express new ideas, do not stay overtime, and do not arrive at work earlier than the designated arrival time [

18,

19]. Although some argue that this is an old phenomenon [

20], until recently there was no literature on the extent of the issue, the factors that cause it and its impact. A large study in the business sector in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic by Gallup showed that half of the employees are quiet quitters [

21]. In the same period, study of the phenomenon was also initiated in the health care sector, with the development of a reliable and valid tool for measuring quiet quitting [

22], which revealed that in this sector too, more than 50% of employees opt for quiet quitting, highlighting the urgency of the issue [

23]. In particular, nurses had the highest rates of quiet quitting (67.4%) compared to other health care professionals [

23]. Studies have shown that burnout is a predictor of quiet quitting [

24], which in turn increases the likelihood of turnover intention among nurses [

25], while moral resilience negatively influences the occurrence of quiet quitting [

26]. To the best of our knowledge, no study until now has examined the impact of workplace bullying on quiet quitting in nurses. Thus, our first hypothesis was the following:

H1. Workplace bullying would have a direct effect on quiet quitting in nurses. In other words, we hypothesized that the higher the levels of workplace bullying, the higher the quiet quitting in nurses.

The highly demanding nursing profession often confronts nurses with stressful situations, affecting their physical and mental health. Faced with these situations, regardless of the degree of organizational support, nurses are required to cope with them in order to reduce their negative impact. Coping with a stressful situation is the third part of a procedure, where the primary appraisal is the process of perceiving a threat to oneself, the secondary appraisal is the process of bringing to mind a potential response to the threat and the coping is the process of executing that response [

27]. Studies have shown the beneficial effect of coping strategies on nurses in reducing their levels of stress, burnout, compassion fatigue and enhancing their psychological well-being [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Considering the essential role of coping strategies as mediator in studies including nurses, we examined the following second hypothesis:

H2. Coping strategies would be a mediator in the relationship between workplace bullying and quiet quitting in nurses. In other words, we hypothesized that nurses who received more workplace bullying may employ more maladaptive (or negative) coping strategies (e.g., self-blame) and less adaptive (or positive) coping strategies (e.g., active coping), and therefore experience higher levels of quiet quitting.

In short, our aim was to examine the direct effect of workplace bullying on quiet quitting and to investigate the mediating effect of coping strategies on the relationship between workplace bullying and quiet quitting in nurses (

Figure 1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a web-based cross-sectional study with nurses in Greece. We used Google forms to create an online version of the study questionnaire. Then, we distributed the questionnaire through nursing groups in Facebook, LinkedIn, Viber and WhatsApp. Thus, a convenience sample was obtained. Our inclusion criteria were the following: (a) nurses who have been working in clinical settings, such as hospitals and healthcare centers, (b) nurses who have been working at least two years in order to experience workplace bullying, and (c) nurses who understand the Greek language. We collected our data during February 2024.

2.2. Measures

We used the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R) to measure workplace bullying among nurses [

32]. The NAQ-R consists of 22 items measuring work-related bullying, person-related bullying, and physically intimidating bullying during the last six months. Answers are on a 5-point Likert scale: never (1), now and then (2), monthly (3), weekly (4), and daily (5). A total score from 22 to 110 is obtained by summing up all answers. Higher scores on NAQ-R indicate higher levels of workplace bullying. We used the valid Greek version of the work NAQ-R [

33]. In our study, Cronbach’s alpha for the NAQ-R was 0.963.

We used the Quiet Quitting Scale (QQS) to measure levels of quiet quitting among our nurses [

22]. The Greek version of the QQS has been validated in a sample of nurses in Greece [

23]. The QQS consists of nine items measuring detachment, lack of initiative, and lack of motivation. Answers are on a 5-point Likert scale: strongly disagree/never (1), disagree/rarely (2), neither disagree or agree/sometimes (3), agree/often (4), strongly agree/always (5). Answers to nine items are averaged to compose an overall score on QQS. Overall QQS score takes values from 1 (low levels of quiet quitting) to 5 (high levels of quiet quitting). Developers of the QQS suggest a cutoff point of 2.06 to discriminate quiet quitters from non-quiet quitters [

34]. In our study, Cronbach’s alpha for the QQS was 0.816.

We used the Brief COPE to measure coping strategies in our sample [

35]. The Brief COPE consists of 28 items measuring the following 14 dimensions: self-distraction, active coping, denial, substance use, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, behavioral disengagement, venting, positive reframing, planning, humor, acceptance, religion, and self-blame. Answers are on a 4-point Likert scale: I haven't been doing this at all (1), I have been doing this a little bit (2), I have been doing this a medium amount (3), and I have been doing this a lot (4). Score ranges from 1 to 4. Higher values indicate higher adaptation of coping strategy. We used the valid Greek version of the Brief COPE [

36]. In our study, all Cronbach’s alphas for the 14 dimensions were above 0.60. A recent systematic review revealed that most studies used the Brief COPE have identified a two-factor structure: approach or positive coping strategies (active coping, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, positive reframing, planning, acceptance, religion, venting, and humor) and avoidance or negative coping strategies (self-distraction, denial, self-blame, behavioral disengagement, and substance use) [

37]. Thus, we followed this two-factor structure in our study. In other words, approach coping is considered as positive/adaptive/engaged/active/direct strategy, while avoidance coping is considered as negative/maladaptive/disengaged/indirect strategy. Score on positive and negative coping strategies range from 1 (low adaptation of strategy) to 4 (high adaptation of strategy).

We considered gender (females/males), age (continuous variable), understaffed department (no/yes), clinical experience (continuous variable), shift work (no/yes) as covariates in the mediation models.

2.3. Ethical Issues

We informed nurses about the aim and the design of the study and gave their informed consent to participate. We did not collect personal data. We followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki in our study. Study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (approval number; 479, 10 January 2024).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

As we explained above, we considered positive (approach) coping and negative (avoidance) coping as potential mediators in the relationship between workplace bullying (independent variable) and quiet quitting (dependent variable). Hair et al. suggest that the number of participants should be at least 10 times that of study variables in the mediation analysis [

38]. Since the NAQ-R (predictor variable) consists of 22 items, the Brief COPE (mediator variable) consists of 28 items and the number of covariates was five, the required sample size was 550 nurses (= 55 variables x 10 = 550).

We present categorical variables with numbers and percentages. Moreover, we present continuous variables with mean, standard deviation, median, minimum value, maximum value and range. We calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficient to determine the correlation between workplace bullying, quiet quitting, positive coping strategies, and negative coping strategies. We constructed a multivariable linear regression model to determine the independent effect of workplace bullying on quiet quitting. In that case, we eliminated the confounding caused by demographic and job characteristics of nurses. Correlation between age and clinical experience was very high (r = 0.912, p < 0.001). Thus, to avoid collinearity in the multivariable linear regression model we decided to include one variable (age) in our model. We present adjusted coefficients beta, 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values for variables in the multivariable linear regression model.

We used the PROCESS macro (Model 4) [

39] to test the mediating effect of positive and negative coping strategies in the relationship between workplace bullying and quiet quitting. We based our mediation analysis on 5,000 bootstrap samples [

40]. We calculated the 95% CIs, regression coefficients (b) and standard errors. P-values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. We used the IBM SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) for statistical analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Job Characteristics

Our sample included 665 nurses. Mean age of nurses was 38.9 years (SD = 10.1), while median and range were 39 and 42 years, respectively. The majority of nurses were females (87.7%). Among our nurses, 80.2% stated that they have been working in understaffed departments and 74.4% were shift workers. Mean years of clinical experience were 14.1 (SD = 10.2), while median value was 14 years, and range was 39 years.

Table 1 shows the detailed demographic and job characteristics of our nurses.

3.2. Study Scales

Descriptive statistics for the study scales are shown in

Table 2. Mean value of the NAQ-R was 51.3 (SD = 20.6), while mean value of the QQS was 2.5 (SD = 0.6). Applying the cutoff point (2.06) for the QQS, we found that 77.3% (n=514) of our nurses were quiet quitters, while 22.7% (n=151) were non quiet quitters. Nurses employed positive coping strategies more often than negative coping strategies, since mean scores were 2.6 (SD = 0.5) and 2.0 (SD = 0.5), respectively.

3.3. Correlation Analysis

Table 3 shows a Pearson’s correlation analysis of workplace bullying, quiet quitting, positive coping strategies, and negative coping strategies. We found a positive correlation between workplace bullying and quiet quitting (r = 0.453, p < 0.001), positive coping strategies (r = 0.244, p < 0.001) and negative coping strategies (r = 0.423, p < 0.001). Moreover, we found a positive correlation between negative coping strategies and quiet quitting (r = 0.395, p < 0.001) and positive coping strategies (r = 0.409, p < 0.001).

3.4. Regression Analysis

We conducted multivariable linear regression analysis to examine our Hypothesis 1. We found that workplace bullying had an independent positive effect on quiet quitting (adjusted beta = 0.010, 95% CI = 0.008 to 0.012, p < 0.001). Workplace bullying explained 20.4% of the variance of quiet quitting. Therefore, our Hypothesis 1 was proved. Gender, positive coping strategies and negative coping strategies were also associated with quiet quitting. These three independent variables explained 7.7% of the variance of quiet quitting. Analysis of variance for the multivariable model was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Table 4 shows the detailed results from the multivariable linear regression analysis.

3.5. Mediation Analysis

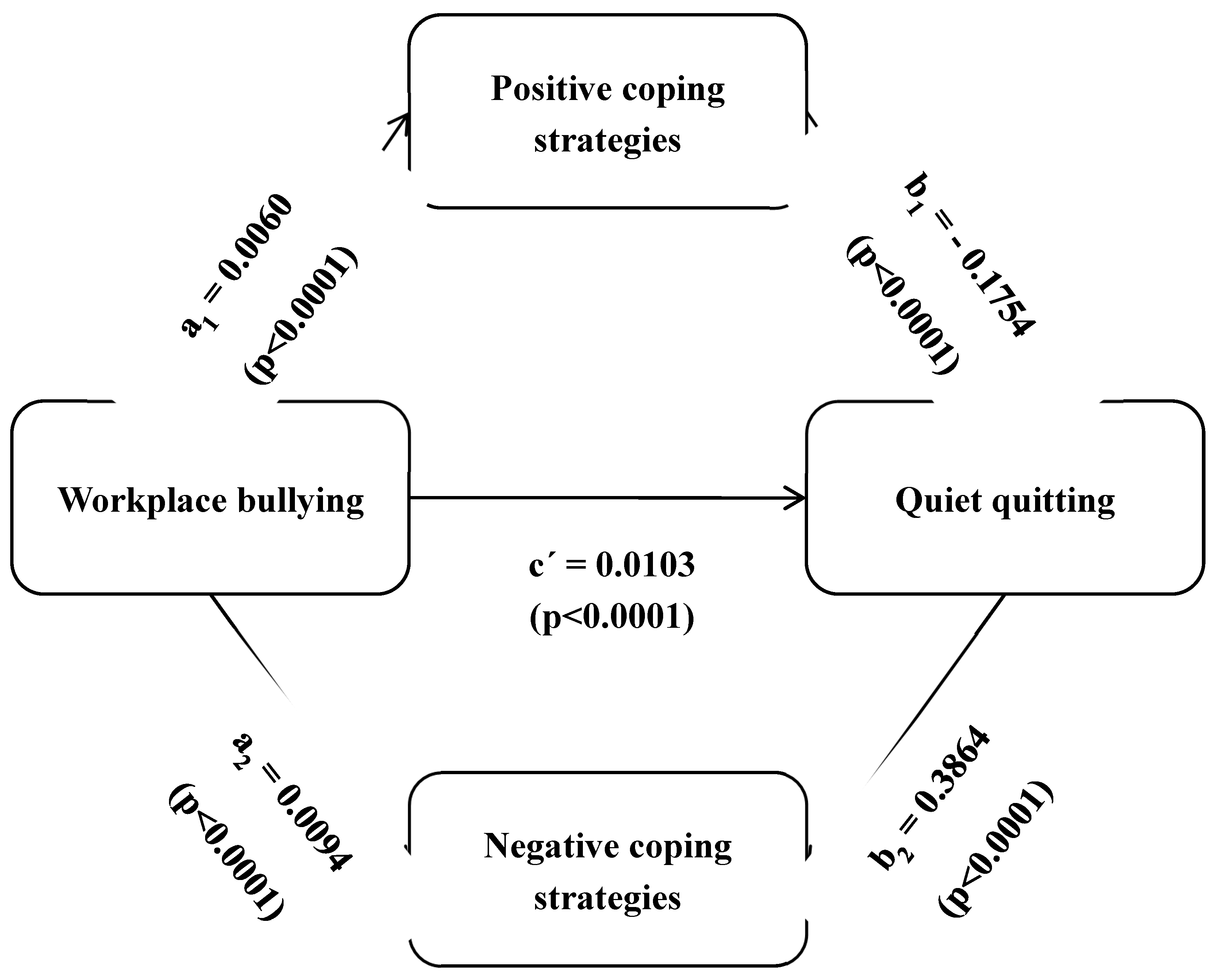

Table 5 shows the indirect impact of workplace bullying on quiet quitting through positive and negative coping strategies. Our mediation analysis showed that the indirect mediated effect of workplace bullying on quiet quitting through positive coping strategies was significant (b = -0.0011, 95% CI = -0.0017 to -0.0005, p < 0.0001). Workplace bullying was a significantly positive predictor of quiet quitting (b = 0.0128, 95% CI = 0.0109 to 0.0147, p < 0.0001). Workplace bullying was a significantly positive predictor of positive coping strategies (b = 0.0060, 95% CI = 0.0042 to 0.0078, p < 0.0001), while positive coping strategies was a significantly negative predictor of quiet quitting (b = -0.1754, 95% CI = -0.2574 to -0.0933, p < 0.0001). Additionally, workplace bullying was a significantly positive predictor of negative coping strategies (b = 0.0094, 95% CI = 0.0079 to 0.0110, p < 0.0001), while negative coping strategies was a significantly positive predictor of quiet quitting (b = 0.3864, 95% CI = 0.2891 to 0.4837, p < 0.0001). Moreover, the direct effect of workplace bullying on quiet quitting was still significant (b = 0.0103, 95% CI = 0.0082 to 0.0122, p < 0.0001) even after the mediating effect of positive and negative coping strategies. Positive and negative coping strategies partially mediated the relationship between workplace bullying and quiet quitting since the direct and indirect effect of workplace bullying was significant. Positive coping strategies caused partial competitive mediation, while negative coping strategies caused partial complimentary mediation. In conclusion, our mediation analysis supported Hypothesis 2.

Figure 2 presents the final mediation model.

4. Discussion

The present study revealed that workplace bullying and negative coping strategies were positive predictors of quiet quitting, while positive coping strategies was a negative predictor of quiet quitting. The mediation analysis showed that positive and negative coping strategies partially mediated the relationship between workplace bullying and quiet quitting.

The present study is the first to highlight the association between bullying and quiet quitting among nurses. We found that 77.3% of our participants can be considered as quiet quitters. The high incidence of bullying in health care organizations may exacerbate the phenomenon of quiet quitting, which in any case seems to be widespread. Nurses who opt for quiet quitting are actually giving an image of adequate staffing, where underneath the numerical staffing lies reduced performance, lack of creativity and innovative behavior. Nurses are caught in the middle of a constant tug-of-war, where on one side are the high job demands and requirements to improve the outcomes of health care organizations, and on the other side is the long-standing inability of health care organizations to ensure adequate resources and organizational support needed in the challenging task of providing health care by nurses. As a result of the above, nurses experience high rates of burnout, dissatisfaction, stress and depression. Bullying is another burdening factor in the work environment of nurses, as it becomes a source of burnout, depression, psycho-physical consequences, turnover and leaving the nursing profession [

41,

42,

43]. By opting for quiet quitting, employees are essentially trying to balance their personal and work lives [

18]. A study on the Harvard Business Review in the field of business showed that as a manager's ability to balance between achieving results and caring about others increases, quiet quitting decreases and employees' willingness to put in more effort increases [

44]. Similar findings in the health sector, regarding bullying, where nurse managers low relationship-oriented leadership style is associated with the occurrence of bullying and turnover intention [

45]. When the nurse manager chooses caring leadership, it reduces the likelihood of his or her staff being exposed to bullying behavior [

46]. Also, when nurses’ victims of bullying receive organizational support, their satisfaction increases and absenteeism from work decreases [

47].

Regardless of the manager's response to the bullying and the degree of organizational support, the nurse is also required to cope with the stressful situation of the bullying episode in which he or she is involved. There is great diversity in the bullying coping strategies chosen by nurses. A cross-cultural scoping review showed that nurses used emotion-focused coping strategies more frequently almost in all clusters [

9]. In a study involving nurses from Portugal, negative bullying coping strategies, including substance use and resorting to evasion predominated, and in their majority, nurses had not received training on the bullying management [

48]. In contrast, nurses in Australia seem to choose positive coping strategies such as problem-focused and seeking social support [

49]. In another study the nurses were more likely to report distraction, substance use, emotional support, disengagement, venting, positive reframing, humor, and religion [

50].

As bullying is a negative and stressful incident in the workplace, the choice of positive coping strategies by the victim is an effective factor in mitigating the negative effects of the incident and contributing to the well-being of the victim [

51]. When nurses apply positive bullying coping strategies, such as more approach-oriented strategies and fewer avoidance-oriented strategies, these strategies were found to be associated with greater psychological well-being and fewer mood disturbances [

52,

53]. Psychological well-being in turn was directly relate to the quality of nurses' practice environment and safety attitudes [

53]. As bullying deteriorates the quality of nurses' working life, the adoption of positive bullying coping strategies moderates this negative effect [

54]. Another effective bullying coping strategy that can be utilized is resilience and mental resilience. Studies have shown their beneficial effect on nurses in terms of reducing COVID-19 pandemic burnout, job burnout, quiet quitting and turnover intention [

26,

55]. In the case of workplace bullying, nurses with a high degree of resilience succeed in reducing the negative impact of bullying on the quality of their work life, as resilience acts as a mediating factor [

56]. Although bullying negatively affects nurses' self-efficacy, when it is cultivated and employed as the coping strategy for bullying, it serves as a mediating factor for the negative impact of bullying on both nurses' mental health, as well as on their intention to leave [

57].

4.1. Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, we cannot infer a causal relationship between workplace bullying and quiet quitting since we employed a cross-sectional design. Second, we conducted a web-based study and therefore we cannot calculate the response rate. Third, we used a convenience sample of nurses in Greece. Thus, we cannot generalize our results although we achieved the minimum sample size for our study. Further studies with random and more representative samples would add invaluable knowledge. Fourth, we examined the mediating effect of coping strategies on the relationship between workplace bullying and quiet quitting. Other variables can also act as mediators and should be investigated in the future. Fifth, we considered several socio-demographic characteristics as covariates in the mediation models. However, scholars should include more socio-demographic variables in the mediation models to further increase the validity of the results. Finally, we used self-reported scales to collect our data. Although, our scales are valid and reliable, information bias is still possible.

5. Conclusions

Bullying is a negative aspect of the nurses' work environment, with a significant prevalence. The present study highlighted its impact on nurses' quiet quitting, and also the crucial role of bullying coping strategies in mediating its impact on quiet quitting. As quiet quitting is becoming increasingly prevalent across a wide range of businesses, including the healthcare sector, reducing the phenomenon of bullying should be an important priority for the managements of healthcare organizations, with the objective of addressing the phenomenon of quiet quitting too. The participants of the present study were found to apply the positive bullying coping strategies, which is an effective attitude towards bullying, and contributes to the reduction of its negative effects. Studies in the existing literature show that nurses often choose negative coping strategies, which have an adverse effect on both the work environment and on themselves personally (e.g. substance use, mental health). It therefore becomes imperative to implement educational interventions to train nurses in the adoption of positive bullying management strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G. (Petros Galanis); methodology, P.G. (Petros Galanis), I.M., A.K., M.M. and I.V.P.; software, P.G. (Petros Galanis) and P.G. (Parisis Gallos); validation, A.K., I.V., M.M., P.G. (Parisis Gallos), M.K. and I.M.; formal analysis, P.G. (Petros Galanis), A.K. and I.V.; investigation, P.G. (Parisis Gallos), M.K., A.K., I.V.; resources, P.G. (Petros Galanis), M.M., I.V.P., A.K., I.V., I.M., M.K. and P.G. (Parisis Gallos); data curation, I.M., M.M., I.V.P., A.K., I.V., M.K. and P.G. (Parisis Gallos); writing—original draft preparation, P.G. (Petros Galanis), I.M., A.K., M.M., I.V., P.G. (Parisis Gallos) and IVP.; writing—review and editing, P.G. (Petros Galanis), I.M., A.K., M.M., I.V., P.G. (Parisis Gallos) and IVP.; supervision, P.G. (Petros Galanis); project administration, P.G. (Petros Galanis) and IVP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (approval number; 479, 10 January 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all the participants who make this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Einarsen, S. Harassment and Bullying at Work: A Review of the Scandinavian Approach. Aggress Violent Behav 2000, 5, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purpora, C.; Cooper, A.; Sharifi, C.; Lieggi, M. Workplace Bullying and Risk of Burnout in Nurses: A Systematic Review Protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2019, 17, 2532–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S.V. What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What We Should and Could Have Known about Workplace Bullying: An Overview of the Literature and Agenda for Future Research. Aggress Violent Behav 2018, 42, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahm, G.B.; Rystedt, I.; Wilde-Larsson, B.; Nordström, G.; Strandmark K, M. Workplace Bullying among Healthcare Professionals in Sweden: A Descriptive Study. Scand J Caring Sci 2019, 33, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awai, N.S.; Ganasegeran, K.; Manaf, M.R.A. Prevalence of Workplace Bullying and Its Associated Factors among Workers in a Malaysian Public University Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2021, 14, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambi, S.; Foà, C.; De Felippis, C.; Lucchini, A.; Guazzini, A.; Rasero, L. Workplace Incivility, Lateral Violence and Bullying among Nurses. A Review about Their Prevalence and Related Factors. Acta Bio Medica 2018, 89, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, L.; Sak-Dankosky, N.; Czarkowska-Pączek, B. Bullying in Nursing Evaluated by the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Adv Nurs 2020, 76, 1320–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S.; Wong, P.Z.E. A Qualitative Systematic Review on Nurses’ Experiences of Workplace Bullying and Implications for Nursing Practice. J Adv Nurs 2021, 77, 4306–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatuna, I.; Jönsson, S.; Muhonen, T. Workplace Bullying in the Nursing Profession: A Cross-Cultural Scoping Review. Int J Nurs Stud 2020, 111, 103628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, H.S.; Hosier, S.; Zhang, H. Prevalence, Antecedents, and Consequences of Workplace Bullying among Nurses—A Summary of Reviews. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusiewicz, C. V.; Shirey, M.R.; Patrician, P.A. Workplace Bullying and Newly Licensed Registered Nurses: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis. Workplace Health Saf 2019, 67, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Mastrogianni, M. Association between Workplace Bullying, Job Stress, and Professional Quality of Life in Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.H.; Benham-Hutchins, M. The Influence of Bullying on Nursing Practice Errors: A Systematic Review. AORN J 2020, 111, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnetz, J.E.; Neufcourt, L.; Sudan, S.; Arnetz, B.B.; Maiti, T.; Viens, F. Nurse-Reported Bullying and Documented Adverse Patient Events: An Exploratory Study in a US Hospital. J Nurs Care Qual 2020, 35, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogh, A.; Baernholdt, M.; Clausen, T. Impact of Workplace Bullying on Missed Nursing Care and Quality of Care in the Eldercare Sector. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2018, 91, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Muharraq, E.H.; Baker, O.G.; Alallah, S.M. The Prevalence and The Relationship of Workplace Bullying and Nurses Turnover Intentions: A Cross Sectional Study. SAGE Open Nurs 2022, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnetz, J.E.; Sudan, S.; Fitzpatrick, L.; Cotten, S.R.; Jodoin, C.; Chang, C.H. (Daisy); Arnetz, B.B. Organizational Determinants of Bullying and Work Disengagement among Hospital Nurses. J Adv Nurs 2019, 75, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyett, A. Quiet Quitting. Soc Work 2022, 68, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzelo, P.R. Discouraging Quiet Quitting: Potential Strategies for Nurses. Holist Nurs Pract 2023, 37, 174–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, J. Quiet Quitting Is a New Name for an Old Method of Industrial Action. The Conversation 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, J. Is Quiet Quitting Real? Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/398306/quiet-quitting-real.aspx (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Moisoglou, I.; Gallos, P.; Kaitelidou, D. The Quiet Quitting Scale: Development and Initial Validation. AIMS Public Health 2023, 10, 828–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Katsoulas, T.; Moisoglou, I.; Gallos, P.; Kaitelidou, D. Nurses Quietly Quit Their Job More Often than Other Healthcare Workers: An Alarming Issue for Healthcare Services. Int Nurs Rev 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Katsoulas, T.; Moisoglou, I.; Gallos, P.; Kaitelidou, D. The Influence of Job Burnout on Quiet Quitting among Nurses: The Mediating Effect of Job Satisfaction. Research Square 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Malliarou, M.; Papathanasiou, I. V; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Kaitelidou, D. Quiet Quitting among Nurses Increases Their Turnover Intention: Evidence from Greece in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Healthcare 2024, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Kaitelidou, D. Moral Resilience Reduces Levels of Quiet Quitting, Job Burnout, and Turnover Intention among Nurses: Evidence in the Post COVID-19 Era. Nurs Rep 2024, 14, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, K.J. Assessing Coping Strategies: A Theoretically Based Approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.F.; Kuo, C.C.; Chien, T.W.; Wang, Y.R. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Coping Strategies on Reducing Nurse Burnout. Applied Nursing Research 2016, 31, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Barmawi, M.A.; Subih, M.; Salameh, O.; Sayyah Yousef Sayyah, N.; Shoqirat, N.; Abdel-Azeez Eid Abu Jebbeh, R. Coping Strategies as Moderating Factors to Compassion Fatigue among Critical Care Nurses. Brain Behav 2019, 9, e01264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.S.H.; Tzeng, W.C.; Chiang, H.H. Impact of Coping Strategies on Nurses’ Well-Being and Practice. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2019, 51, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, K.Q.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Abdul-Manan, H.H.; Mohd-Salleh, Z.A.H.; Abdul-Mumin, K.H.; Rahman, H.A. Strategies Used to Cope with Stress by Emergency and Critical Care Nurses. British Journal of Nursing 2019, 28, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Notelaers, G. Measuring Exposure to Bullying and Harassment at Work: Validity, Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work Stress 2009, 23, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoulakis, C.; Galanakis, M.; Bakoula-Tzoumaka, C.; Darvyri, P.; Chroussos, G.; Darvyri, C. Validation of the Negative Acts Questionnaire (NAQ) in a Sample of Greek Teachers. Psychology 2015, 6, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Moisoglou, I.; Gallos, P.; Kaitelidou, D. Quiet Quitting among Employees: A Proposed Cut-off Score for the “Quiet Quitting” Scale. Research Square (Preprint) 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. You Want to Measure Coping but Your Protocol’s Too Long: Consider the Brief COPE. Int J Behav Med 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsou, M.; Panayiotou, G.; Kokkinos, C.M.; Demetriou, A.G. Dimensionality of Coping: An Empirical Contribution to the Construct Validation of the Brief-COPE with a Greek-Speaking Sample. J Health Psychol 2010, 15, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg, M.A.; Gridley, M.K.; Peters, R.M. The Factor Structure of the Brief Cope: A Systematic Review. West J Nurs Res 2022, 44, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, T.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, 2013; ISBN 9781462534661. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav Res Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen Hsiao, S.T.; Ma, S.C.; Guo, S.L.; Kao, C.C.; Tsai, J.C.; Chung, M.H.; Huang, H.C. The Role of Workplace Bullying in the Relationship between Occupational Burnout and Turnover Intentions of Clinical Nurses. Applied Nursing Research 2022, 68, 151483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambi, S.; Guazzini, A.; Piredda, M.; Lucchini, A.; De Marinis, M.G.; Rasero, L. Negative Interactions among Nurses: An Explorative Study on Lateral Violence and Bullying in Nursing Work Settings. J Nurs Manag 2019, 27, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Kabir, H.; Mazumder, S.; Akter, N.; Chowdhury, M.R.; Hossain, A. Workplace Violence, Bullying, Burnout, Job Satisfaction and Their Correlation with Depression among Bangladeshi Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Survey during the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0274965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenger, J.; Folkman, J. Quiet Quitting Is About Bad Bosses, Not Bad Employees. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/08/quiet-quitting-is-about-bad-bosses-not-bad-employees (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Fontes, K.B.; Alarcão, A.C.J.; Santana, R.G.; Pelloso, S.M.; de Barros Carvalho, M.D. Relationship between Leadership, Bullying in the Workplace and Turnover Intention among Nurses. J Nurs Manag 2019, 27, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olender, L. The Relationship between and Factors Influencing Staff Nurses’ Perceptions of Nurse Manager Caring and Exposure to Workplace Bullying in Multiple Healthcare Settings. Journal of Nursing Administration 2017, 47, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, K.C.; Oh, K.M.; Kitsantas, P.; Zhao, X. Workplace Bullying among Nurses and Organizational Response: An Online Cross-Sectional Study. J Nurs Manag 2020, 28, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- João, A.L.; Portelada, A. Coping with Workplace Bullying: Strategies Employed by Nurses in the Healthcare Setting. Nurs Forum (Auckl) 2023, 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, N.; Jeong, S.; Smith, T. Negative Workplace Behavior and Coping Strategies among Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs Health Sci 2021, 23, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acquadro Maran, D.; Giacomini, G.; Scacchi, A.; Bigarella, R.; Magnavita, N.; Gianino, M.M. Consequences and Coping Strategies of Nurses and Registered Nurses Perceiving to Work in an Environment Characterized by Workplace Bullying. Dialogues in Health 2024, 4, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.P.; Westbrook, R.A.; Challagalla, G. Good Cope, Bad Cope: Adaptive and Maladaptive Coping Strategies Following a Critical Negative Work Event. J Appl Psychol 2005, 90, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, C.M.; McKay, M.F. Nursing Stress: The Effects of Coping Strategies and Job Satisfaction in a Sample of Australian Nurses. J Adv Nurs 2000, 31, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.S.H.; Tzeng, W.C.; Chiang, H.H. Impact of Coping Strategies on Nurses’ Well-Being and Practice. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2019, 51, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, R.; Li, J.; Cheng, N.; Liu, X.; Tan, Y. The Mediating Role of Coping Styles between Nurses’ Workplace Bullying and Professional Quality of Life. BMC Nurs 2023, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Malliarou, M.; Papathanasiou, I. V.; Gallos, P.; Galanis, P. Social Support and Resilience Are Protective Factors against COVID-19 Pandemic Burnout and Job Burnout among Nurses in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Preprints.org 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Luo, H.; Ma, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; He, J.; Song, Y. Association between Workplace Bullying and Nurses’ Professional Quality of Life: The Mediating Role of Resilience. J Nurs Manag 2022, 30, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, Y.H.; Wang, H.H.; Ma, S.C. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Relationship between Workplace Bullying, Mental Health and an Intention to Leave among Nurses in Taiwan. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2019, 32, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).