1. Introduction

Quantum cryptography promising information transmission invulnerable to cyber threats stands at the forefront of a new era in secure communication. One of the major challenges here is the development of methods allowing for high rate quantum communication over long distances. The important work of Pirandola, Laurenza, Ottaviani, and Banchi [

1] showed that in a lossy repeaterless transmission channel, the scaling of the quantum information transmission rate is fundamentally bound by

, where

T is the channel’s transmissivity. In the real channels, particularly in the fiber-optic lines,

T drops exponentially with the distance, severely limiting the communication range. Despite this obstacle, remarkable progress has been achieved in extending quantum communication distances to hundreds and even a thousand of kilometers [

2]. Notable milestones in Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) past elaborations include advancements in twin-field QKD [

2,

3], measurement of the device independent QKD with the decoy-state method [

4], the satellite-based QKD [

5], and the time-bin QKD [

6,

7]. Another possible way of extending transmission distances is the use of quantum repeaters [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], which are based on utilizing the quantum entanglement resource.

Recent theoretical paper [

14] has established an alternative approach to overcoming the distance limitations of key distribution, which has later been realized experimentally in Ref. [

15]. Our further developed Quantum-protected Control-based Key Distribution (QCKD) follows the prepare–and–measure logics in the optical setting. In this protocol, the bits 0 and 1 are represented by the coherent states

and

. The central idea is that the legitimate users, Alice and Bob, monitor the local signal leakages within the transmission channel, fiber-optic line, and ensure that the leaked states, potentially captured by an eavesdropper, Eve, are substantially non-orthogonal. If the proportion of the leaked signal is

, then

, and as this scalar product closely approaches 1, the information accessible to Eve, constrained by the Holevo bound, goes to zero. As long as the leakage remains below a certain threshold, the users maintain an informational advantage over Eve, ensuring the safe distribution of the secret key. Importantly, given that the employed coherent states’ intensities,

and

, are sufficiently low, eavesdropping on the homogeneously distributed Rayleigh scattering is unfeasible [

14,

15]. With that, the signal states can have sufficient intensities to be transmitted across a long fiber line containing optical amplifiers.

Here, to demonstrate the remarkable scalability and effectiveness of the boosted QCKD, we present the experimental results obtained for a 1,707 km-long fiber line. In contrast to the broader protocol structure explored in our previous works [

14,

15], this paper narrows its focus demonstrating the robustness of the protocol’s individual components. We show the precision and effectiveness of the loss control based on the Optical Time-Domain Reflectometry (OTDR) [

16,

17]. We discuss the impacts of statistical fluctuations and technical noise on the key distribution rate. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the application of an advantage distillation in the QCKD, which makes the system more tolerant of errors, enables the accommodation of larger signal losses over long transmission distances. Finally, we present the results of the key distribution over various distances, including 1,707 km. In addition, we discuss the possibility of expending the QCKD to a multi-user network.

2. Experimental Setup

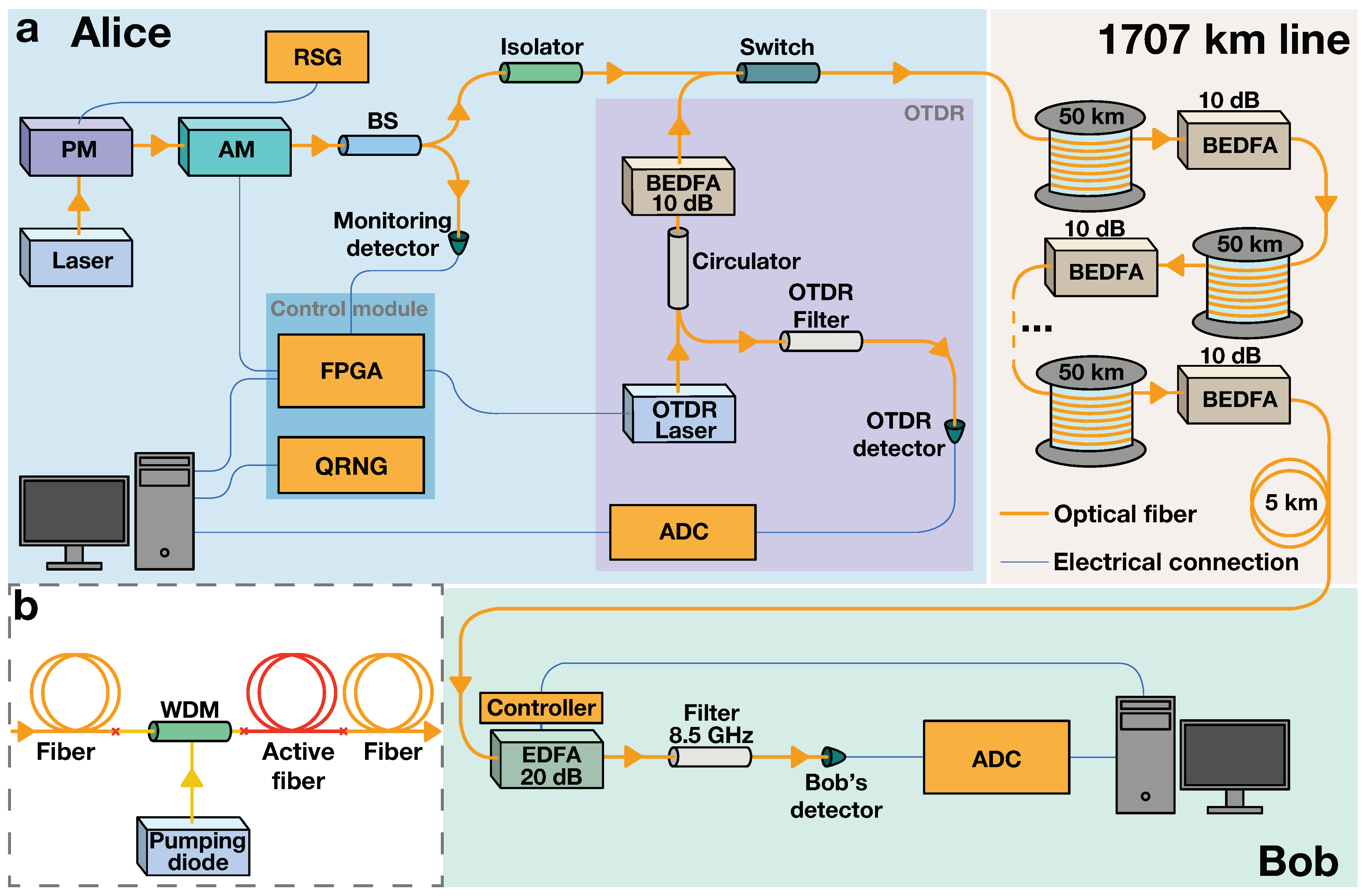

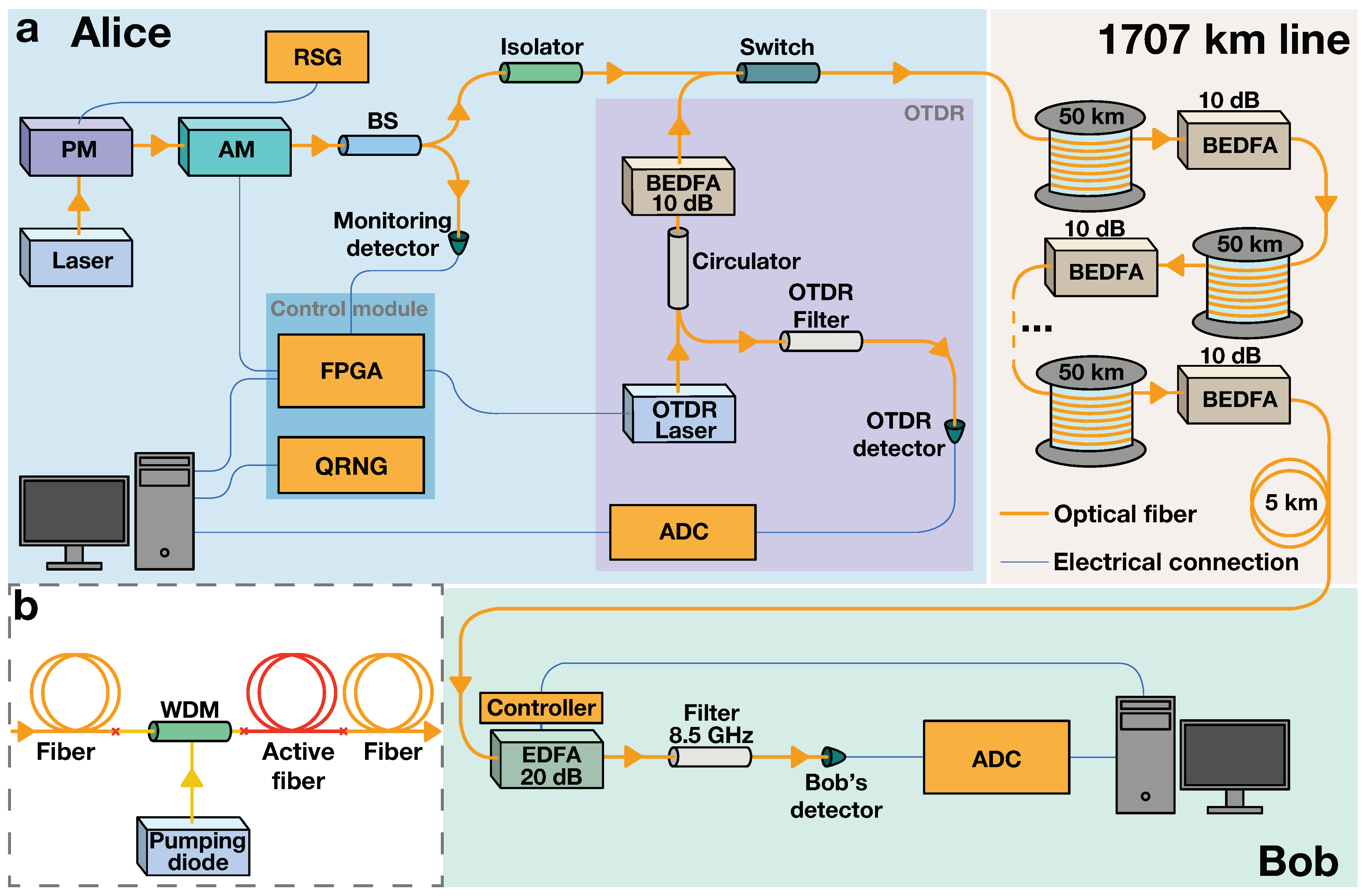

We begin by outlining our experimental QCKD setup which, with certain modifications, follows the theoretical scheme from Ref. [

14]. The setup is illustrated in

Figure 1a. The key distribution begins with the generation of non-orthogonal optical states encoding random bits into coherent optical pulses at Alice’s side:

Coherent light from the 1,530.33 nm laser source first passes through a Phase Modulator (PM) linked to a Random Signal Generator (RSG), inducing light’s phase randomization.

The light then enters a Mach–Zender Amplitude Modulator (AM), which forms bit-encoding optical states: the AM is linked to a control module comprising a Quantum Random Number Generator (QRNG) and Field Programmable Gate Array (FPGA). The FPGA converts L random bits from the QRNG into voltage pulses which are fed to the AM. The resulting light pulses corresponding to 0 and 1 comprise photons and photons, respectively.

The optical signal is split by a Beam Splitter (BS), with one part directed to Bob and the other to a monitoring detector. The monitoring ensures precise adjustment of the control module and AM. The primary signal portion then passes through an optical isolator to prevent noise and signal reflections from reaching the sending equipment.

The signal then travels through the 1,707 km-long transmission line, composed of the 50 km-long optical fiber spans and the Bidirectional Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers (BEDFAs). The main feature that distinguishes the BEDFA [

14], depicted in

Figure 1b, from the regular Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifier (EDFA) [

18,

19] is the absence of optical isolators or circulators, allowing for the transmission of the backscattered components of the probing signal used for the OTDR. At Bob’s end, the signal undergoes several steps:

The signal is preamplified by 20 dB with an EDFA.

It then passes through a thermostabilized optical filter with an 8.5 GHz bandwidth, which eliminates noise in secondary modes caused by the amplifiers.

Finally, the signal reaches Bob’s detector. The analog signal from the detector is converted into a digital signal by an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC).

Figure 1.

Experimental setup. (

a) Schematics of the QCKD system. At Alice’s end, a Phase Modulator (PM) connected to a Random Signal Generator (RSG) randomizes the phase of the light from the laser. A Quantum Random Number Generator (QRNG) creates a bit sequence, which is encoded into the passing light signal with a Field-Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) and an Amplitude Modulator (AM). A Beam Splitter (BS) redirects part of the signal to Alice for monitoring. The signal then passes through the 1,707 km communication line, comprising 50 km fiber spans and Bidirectional Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers (BEDFAs). After preamplification, filtering, and detection at Bob’s end, the signal is converted to bits with an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC). The switch alternates between key generation, and Optical Time-Domain Reflectometry (OTDR). (

b) The scheme of the BEDFA. A Wavelength-Division Multiplexing (WDM) system merges the optical line’s signal with diode pumping into an active fiber segment, which then connects to the main fiber. Adapted from Ref. [

14] under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup. (

a) Schematics of the QCKD system. At Alice’s end, a Phase Modulator (PM) connected to a Random Signal Generator (RSG) randomizes the phase of the light from the laser. A Quantum Random Number Generator (QRNG) creates a bit sequence, which is encoded into the passing light signal with a Field-Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) and an Amplitude Modulator (AM). A Beam Splitter (BS) redirects part of the signal to Alice for monitoring. The signal then passes through the 1,707 km communication line, comprising 50 km fiber spans and Bidirectional Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers (BEDFAs). After preamplification, filtering, and detection at Bob’s end, the signal is converted to bits with an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC). The switch alternates between key generation, and Optical Time-Domain Reflectometry (OTDR). (

b) The scheme of the BEDFA. A Wavelength-Division Multiplexing (WDM) system merges the optical line’s signal with diode pumping into an active fiber segment, which then connects to the main fiber. Adapted from Ref. [

14] under CC BY 4.0.

The

L bits now distributed between Alice’s and Bob’s computers undergo post-processing consisting of postselection described in Ref. [

14], advantage distillation that is explained in details below, error correction, and privacy amplification. Depending on whether the leakage

is above or below a predetermined threshold

, the block of

resulting bits is either saved or completely discarded. The pulses’ and post-processing parameters and

are chosen in such a way that if

falls below

, then after post-processing Eve does not have any information about the resulting block of bits. This is based on the equation for

, see Equation (

1), which utilizes the users’ information advantage over Eve [

14]. Conversely, if

exceeds

, the block is assumed compromised and thus gets discarded. The binary decision making – to save or not to save a packet of bits – differs from the original approach of Ref. [

14], which suggests adapting the pulses’ and post-processing parameters based on the leakage to harvest useful key from every block of bits. However, the core principle of the protocol remains the same.

Continuous monitoring of signal leakage is achieved using transmittometry and the OTDR, which operate in turns following each transmission of an L-long packet of bit-encoding signal pulses:

Transmittometry. During this phase, Alice’s AM and FPGA produce high intensity periodic signal at 25 MHz. Bob measures the signal at his end, and by comparing the input and output spectral power peaks, the users determine the total leakage in the line; the signal modulation suppresses the

noise. Knowing the baseline of homogeneous natural losses (established during the preliminary stage without eavesdropping threats), the users can estimate the overall leakage. The operation and precision of transmittometry has been demonstrated in Ref. [

15], so in this paper, we will not concentrate on it.

The OTDR. In this phase, the system activates the switch, halting the light transmission from Alice’s primary laser. The transmission line is then utilized for probing pulses generated by the OTDR module. A high-intensity probing pulse is produced by the dedicated OTDR laser controlled by the FPGA. The probing pulse is directed through an optical circulator, subsequently amplified by the BEDFA, and then transmitted into the optical fiber line. As this pulse travels through the line, its parts are backscattered at various points of the optical fiber. The backscattered components then retrace their path back through the circulator and filter and are subsequently detected by the OTDR detector. As we show in next section, the analysis of the backscattered power as a function of the time delay, yields a comprehensive loss profile of the entire transmission line.

The signal wavelength of 1,530.33 nm is specifically selected because it aligns with the peak of the BEDFA amplification gain spectrum in the C-band optical frequency range. Opting for a commonly used wavelength like 1,550 nm would lead to a situation where the amplified spontaneous emission noise in the secondary modes, particularly around 1,530 nm, would be amplified more than the actual signal. This could particularly result in the radiation generation (the amplifiers would essentially work as lasers) and instability of the transmission line. Other details on BEDFAs can be found in [

14].

It is important to mention that the encoding scheme employed in our study is impervious to the effect of chromatic dispersion, which often leads to problems in long-distance optical signal transmission. As detailed in the Methods section, chromatic dispersion does not alter the photon counts in signal pulses, which carry the bit information. However, alternative schemes, such as encoding bits into the pulses’ shapes, may still be susceptible to chromatic dispersion, potentially resulting in an increased number of bit errors.

3. Optical Time-Domain Reflectometry

We now discuss in detail the experimental loss control for the 1,707 km line. We have already demonstrated the precision of the long-distance transmittometry [

15], so here we will rather concentrate on the OTDR [

16,

17] for the 1,707 km line.

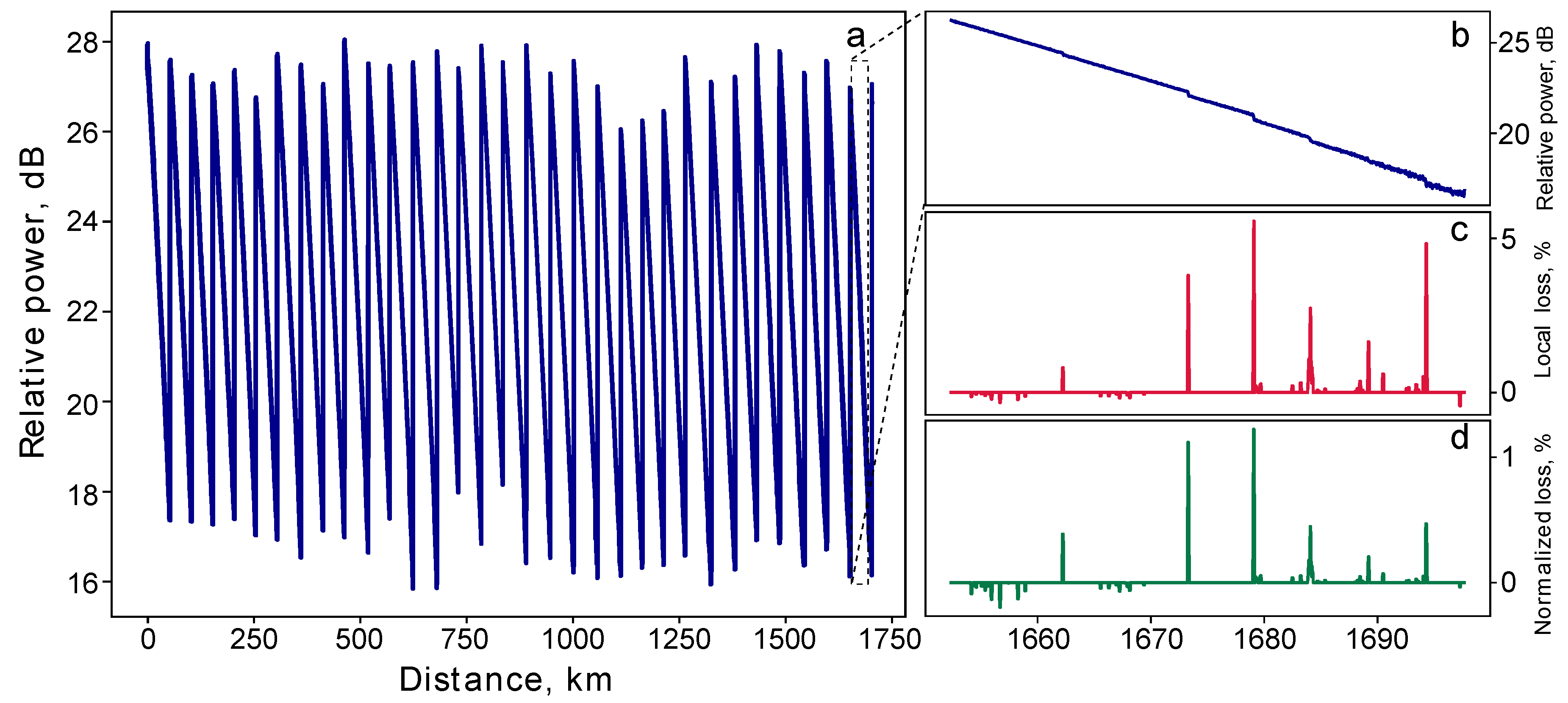

The OTDR uses Rayleigh scattering as an instrument in detecting any new leakages that may arise along the fiber-optic line. The core principle involves transmitting a high-intensity probing pulse into the optical fiber and then measuring the power of the light that is backscattered to the source. This measurement records the distance to the corresponding scattering point, which is determined based on the time it takes for the light to return. Any newly occurring leakage changes power of the backscattered radiation from the OTDR probing pulse. Specifically, the backscattered power decreases in the segment of the fiber where the eavesdropping intervention is located. The collected data from this process is represented in a reflectogram, which is a log-linear plot that depicts the backscattered power as a function of distance along the fiber.

In telecommunications, the OTDR is typically applied only to the transmission line segments that do not contain amplifiers. This is because the standard amplifiers include elements, like optical circulators, that prevent the return of backscattered light, making it not possible to analyze the line in its entirety. However, our BEDFAs, the schematics of which is depicted in

Figure 1b, are designed without these elements.

Figure 2a displays the experimentally obtained reflectogram for the entire 1,707 km line, including 32 BEDFAs. The measurement which took 180 s (including both the physical measurements and the computational processing of the obtained data) was conducted at a wavelength of 1,530 nm, with a probing pulse duration of 200 ns, and averaging over

pulses’ runs. The reflectogram exhibits a characteristic saw-like pattern indicating sharp increases in backscattered power at each BEDFA and providing a visual map of their positions along the fiber.

After obtaining the line’s reflectogram, we employ the

-filtering technique [

20] to infer the loss profile of the line. This technique consists of fitting the reflectogram with a weighted sum of step-like functions corresponding to local leakages and one linear function describing natural Rayleigh scattering losses through minimizing the

norm of the steps’ weights. Then, removing the linear part of the function and analyzing only the remaining step-like functions, we separate local leakages from the natural losses and background noise. Optical amplifiers additionally introduce step-like functions with positive discreet derivatives which must also be filtered out. After this filtering, we obtain the local losses from the remaining step-like functions by calculating the drops of these functions.

Panels (b) and (c) in

Figure 2 illustrate the reflectogram and the loss profile (with the leakage normalized to the power just before the corresponding scattering point) for a 50 km section subsequent to the 31st amplifier within our 1,707 km line. The leakages, ranging from 1 to 5%, were purposefully induced in this specific segment to demonstrate the operation of the loss control.

Figure 2d additionally presents the same loss profile but with leakage normalized to the initial power of the probing pulse, this loss profile is used for determining the value of

utilized in the protocol. Despite the large length of the fiber, we achieve the impressive OTDR precision ranging from 0.01 dB at the beginning of the fiber section to 0.07 dB at the section’s end. We calculate this precision by constructing four individual reflectograms, each representing an average over 1,000 separate probe runs, and then obtaining the standard deviation over these four reflectograms for each distance.

Figure 3a presents two independently obtained reflectograms of the 4 km-long fiber section in the end of the line. In turn,

Figure 3b depicts the corresponding profiles obtained from the reflectograms by subtracting the linear components. Remarkably, the traces corresponding to the independent OTDR measurements exhibit identical patterns with the correlation coefficient of 0.95. This confirms that the observed features are not mere noise but are, in fact, unique patterns due to the amorphous structure of the silica fiber. Considering the significant distance of over 1,700 km from the reflectometer, the consistency in replicating this pattern is highly notable. As the silica amorphous structure cannot be replicated, the observed distinctive pattern is a physically unclonable function [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Any physical tampering with the line would thus alter its characteristic fingerprint. With the BEDFAs maintaining the initial power levels of both the OTDR probing pulse and its backscattered components across the line, we can thus verify this unique line’s fingerprint and check the integrity of the fiber over the entire 1,707 km line [

25].

4. Statistical Fluctuations and Technical Noise

In the experimental QKD, Alice and Bob work with finite data samples, whereas the original theoretical security proofs deal with probabilities. To reconcile these two scenarios, the notion of the secret key and the security proof in the finite data regime can be properly modified [

26]. In particular, this involves estimation of the upper bounds of the deviations of measurable statistical average values from their ideal expectation values, and refining the formulas for the secure key rate to include experimentally measurable parameters derived from finite data sets. This approach requires to introduce an additional parameter, a level of confidence that the actual secure key, obtained from the measured statistics, and the ideal key, based on probabilistic values, are indistinguishable with the given confidence level. Typically, the confidence level is selected to be

with a pretty small value of

, which corresponds to the tolerance interval with

standard deviations. Below, we address the issue of deviation between the statistical mean values and the corresponding probabilities in our protocol.

Note that besides statistical fluctuations, there are additional noise sources that also impact the secret key rate. In the case of our protocol, the leakage

is obtained via the loss control procedure that operates on a finite number of probing pulses, thus estimation of

is influenced by the finite data statistics as well. Moreover, measurements at the loss control part are inherently noisy due to various technical imperfections, which further affects

. Security analysis of conventional QKD protocols, like the BB84, typically focuses only on the statistical fluctuations due to the finite size of data used for key generation. In these protocols, all types of noise and imperfections in the communication line lead to an increased quantum bit error rate, or another metric indicating the potential presence of Eve. An important feature of our protocol is that the secret key rate depends not only on the quantum data, but also on the line control procedure. The latter involves estimation of the local leakage

, which is affected by both statistical fluctuations and various technical imperfections. Following the theory of our protocol outlined in Ref. [

14], the secret key rate depends on magnitudes of

,

and

. The secret key rate implies certain fixed magnitudes of

obtained through the secret key rate maximization, while in practice these values are derived from a calibration process that is inherently noisy due to the finite number of calibration measurements. The value

is a free parameter that reflects the amount of eavesdropping, which we estimate by the OTDR. We select our confidence level

, hence the expectation values

,

, and

utilized in the secret key rate formula should fall within 6 standard deviations from the corresponding sample mean values. We also assume that all measurement results that are used for estimation of

,

and

are independent and distributed identically.

We start with the photon numbers and . Ideally, these values are fixed, and can be found by optimization of the secret key rate for any given communication line. In practice, the pulses’ intensities are calibrated to a reference, which involves a finite number of intensity measurements. Specifically, we run a sequence of 50,000 calibration signals, and gather the resulting voltage statistics from the detector. We then translate this statistics into photon numbers, and obtain the mean values and the standard deviations. The corresponding fluctuations surpass the shot noise due to the technical noise inherent to the electronics. To evaluate the impact of the finite statistics of the experimental dataset on the precision of the estimated values, we employ the previously mentioned assumptions. As an example, we obtain the sample mean values and and standard deviations and , which correspond to the estimates and .

Next, we estimate the value measured via the OTDR. Let the relative power levels of the light backscattered before and after the point of the local leakage be and , respectively. We measure the difference by collecting 20 reflectograms each obtained by averaging over 5,000 probing pulses. Based on the experimental data, we obtain the sample mean and standard deviation . To fall within interval, the statistical estimate is . After long-term monitoring of the communication line, we find that these are quite typical values. Thus we set an upper bound , which, according to our observations, is always satisfied.

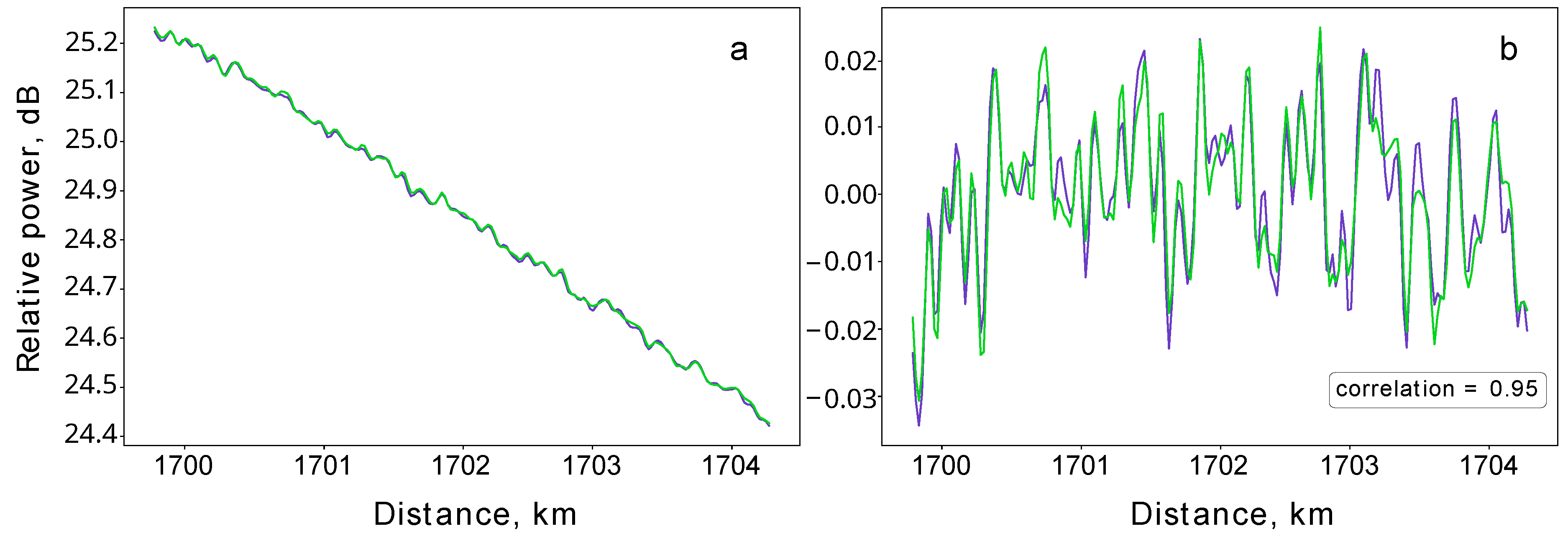

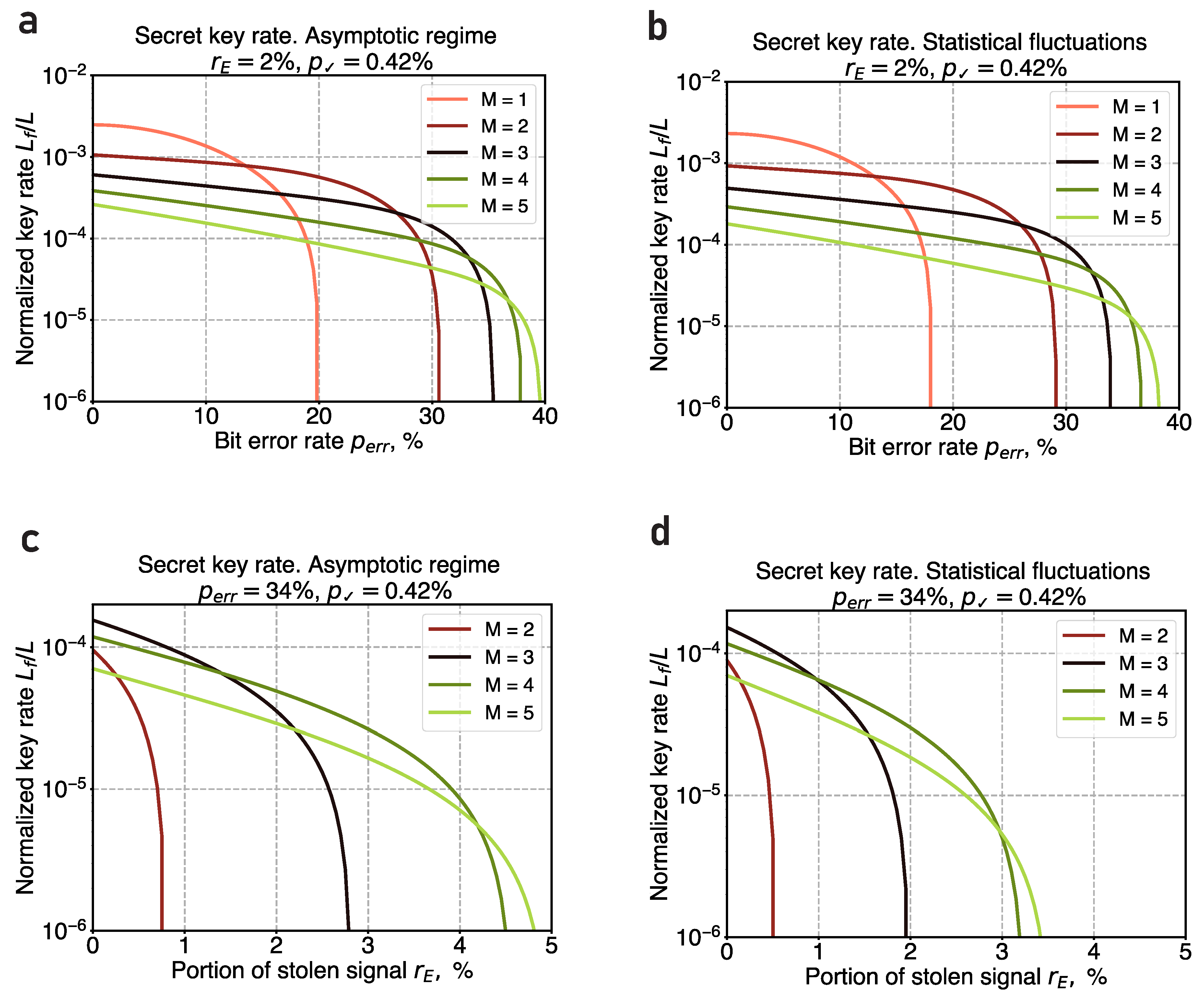

In the next section, we utilize the calculated inaccuracies of

,

and

to compute the key rates, see

Figure 4b,d, and perform the comparison with the asymptotic limit, see

Figure 4a,c.

5. Advantage Distillation and Final Key Length

Scattering losses and amplifier noise in a long transmission line raise the Bit Error Rate (BER),

, which in the case of our 1,707 km line reaches as much as 34.0%. Under such conditions, standard error correction based on the Low-Density Parity-Check (LDPC) codes and privacy amplification are insufficient for securing a key against potential adversaries. To increase the tolerance to errors and harvest the key even with

, we employ the so-called advantage distillation technique [

27,

28,

29,

30]. This technique has been previously applied to some of the well-known QKD protocols and proved to be beneficial when dealing with increased errors [

31,

32,

33].

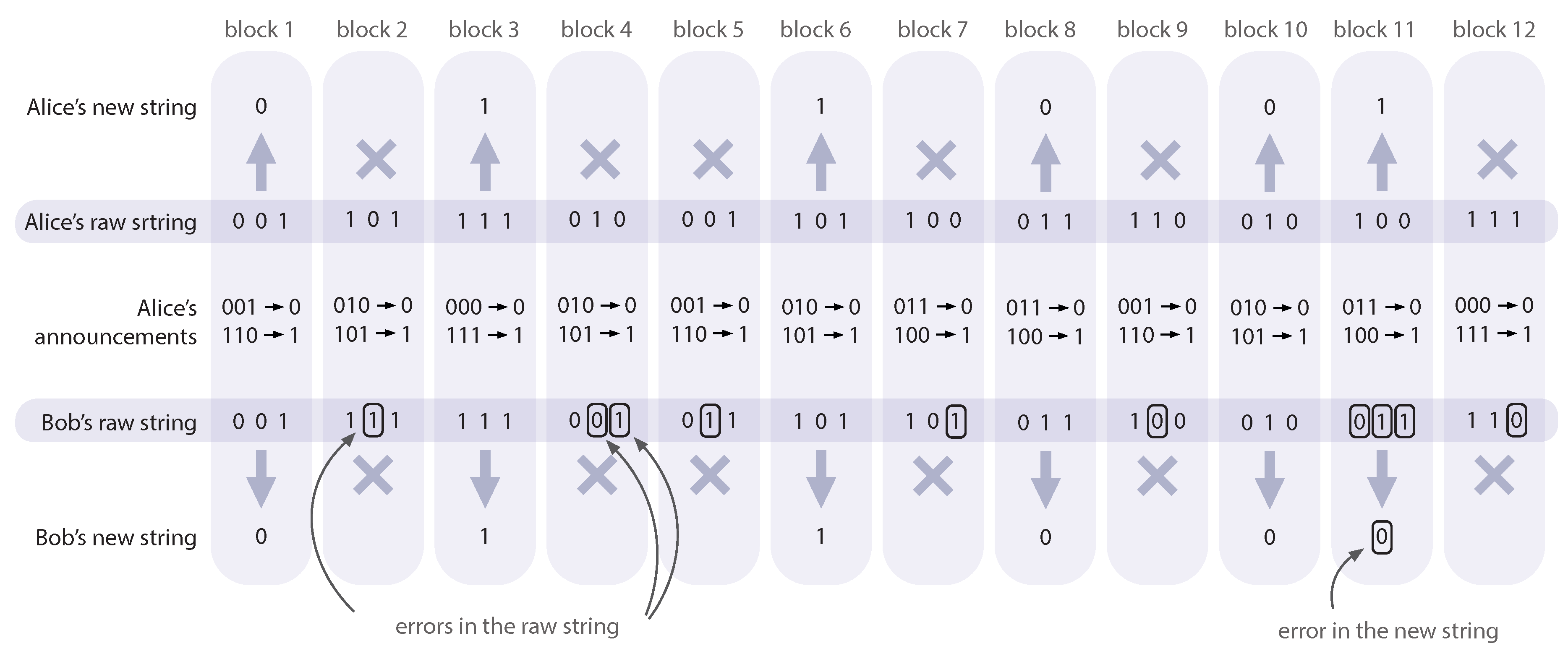

The advantage distillation is conducted after the postselection but before the error correction stage. During this phase, the legitimate users divide their sifted strings into blocks of the length

M. For each block

, Alice publicly declares a syndrome of the block according to the repetition code with the block’s length

M. This way she announces that her block is either

a or

(the overline stands for the inversion of

a). If the corresponding Bob’s block coincides with

a or

, the users agree to count it as a single bit of the raw key (e.g.,

a means 0,

means 1), otherwise it gets discarded. The probability for a block to survive this stage is equal to

, while the modified error probability in the new raw key is

. For more details on the technique see Methods and

Figure 8.

Following the advantage distillation, Alice and Bob carry out the standard error correction and privacy amplification procedures obtaining the final secret key. If

L is the number of bits that Alice initially sends to Bob, the length of the final key is

where

p✓ is the proportion of bits that are not discarded during the postselection, and

corresponds to the bit reduction due to the advantage distillation. The term in the square brackets results from the Devetak–Winter equation[

34] and represents the informational advantage of Alice and Bob over Eve: the classical information disclosed to Eve during error correction is

, where the parameter

characterizes the efficiency of a particular correction code,

is the binary entropy, and

is the information that Eve can extract from the intercepted proportion of signal, see Equations (

3) and (

4) in Methods.

Figure 4 shows the final key generation rate in the presence of advantage distillation as a function of the observed parameters. This is illustrated in two scenarios: one is the asymptotic limit, see

Figure 4a, and the other accounting for finite-size effects and fluctuations, see

Figure 4b. The five curves in each plot represent different values of the block’s length

M;

corresponds to the scenario without advantage distillation. In the asymptotic limit, the system’s tolerance to the BER can be improved from 20% up to 39%, while in the finite-size case, it reaches 37%; however, this increase in the BER tolerance comes at a cost, notably reducing the key generation rate by two orders of magnitude. Such high critical BER values are achieved for

; further increase of

M provides a slight improvement of the critical BER, yet, it leads to a way more significant decrease in key rate.

Advantage distillation also significantly enhances the system’s resilience against the leakage

.

Figure 4 shows the final key distribution rate as a function of

for the fixed BER value of

, as well. Here,

Figure 4c,d correspond to the asymptotic and finite-size regimes, respectively. It is important to note that for

the secure key distribution becomes unattainable without advantage distillation. Nevertheless, advantage distillation with any non-trivial block length (

) solves this problem and yields non-negative secret key rates. Particularly, with a block length of

, successful key distribution is achievable for leakage rates as high as

in the asymptotic limit and up to

in the finite-size scenario.

Our results add to the findings established in our previous publications [

35,

36] in which we explored various strategies to enhance the efficiency of key distribution through modifications of post-processing.

6. Key Distribution Results

We now present the results of the key distribution itself. With the parameters

,

and

leveraging a random number generation rate of 5 Mbps at Alice’s side, and advantage distillation with the block size of

, we achieved a key rate of 0.9 bps across our 1,707 km optical fiber line. This assumed that the value of

is below

, as ensured by the loss control precision. This achievement, along with the key rates obtained at other transmission distances using the same setup, is depicted in

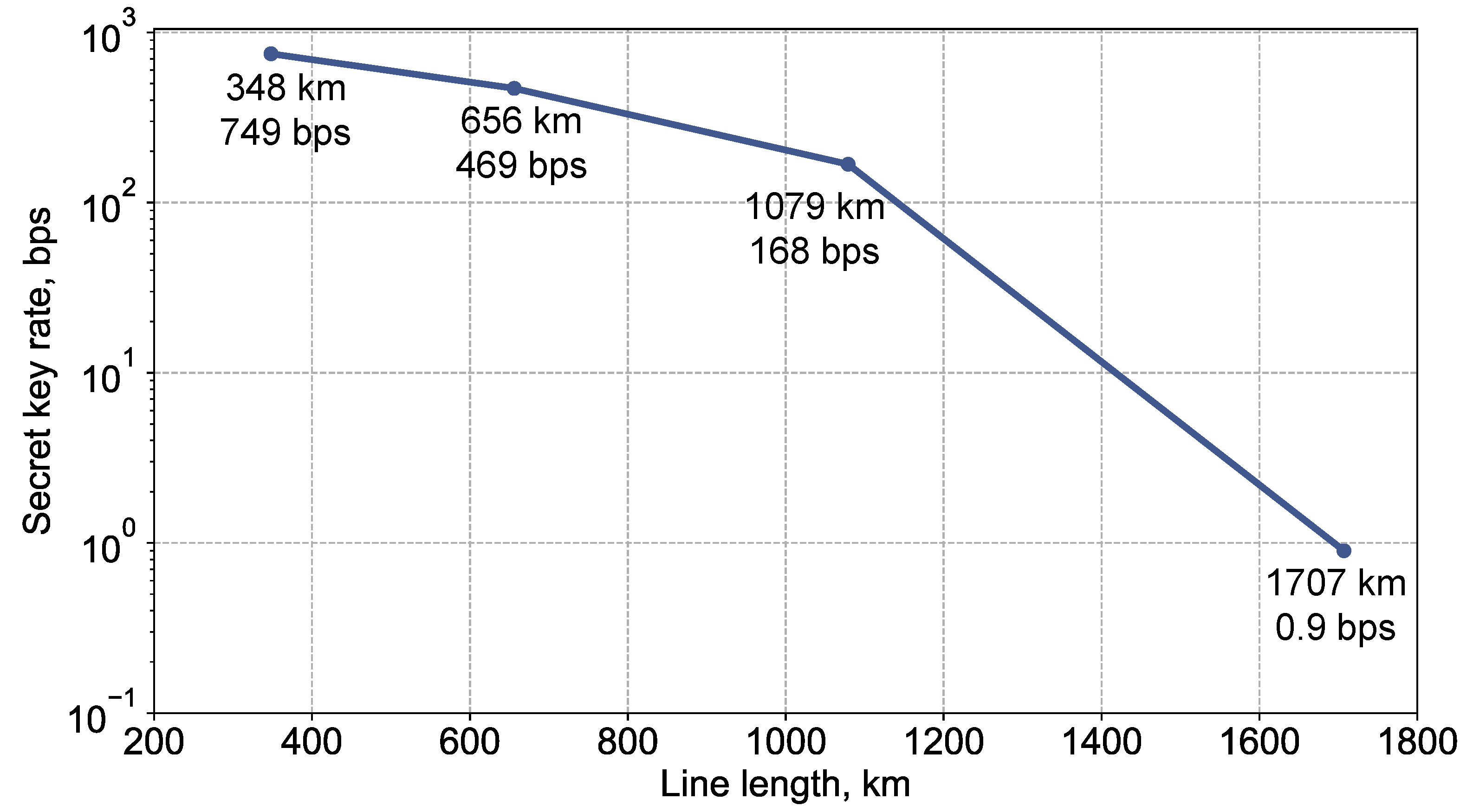

Figure 5 (all results are obtained in the asymptotic limit). We note that we did not encounter radiation generation, so despite comprising 32 BEDFAs, the line remained stable.

To assess the statistical quality of the distributed bits, we accumulate them over an extended period of time and divide them into 2,930 segments, each containing 1,024 bits. We then compute the average and variance of the bit sum per segment across the entire ensemble, yielding 512.4 and 255.9, respectively. This result closely aligns with the theoretical expectations of 512 and 256, corresponding to the binomial distribution. Such consistency with the binomial distribution additionally underscores the robustness of the realized QCKD. Further analysis of the key’s statistical properties, including a comprehensive examination with the NIST testing methods, will be uncovered in our forthcoming publication.

7. The QCKD Network

Beyond point-to-point secure communication, the expanding digital landscape demands quantum-resistant key distribution solutions for multiple users [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. It turns out that the operational principle of our QCKD opens the possibility of building a zero-trust key distribution network that does not require connecting everyone to everyone. In this section we outline such a network architecture, where users can alternate between receiving and transmitting modes under the supervision of other network participants.

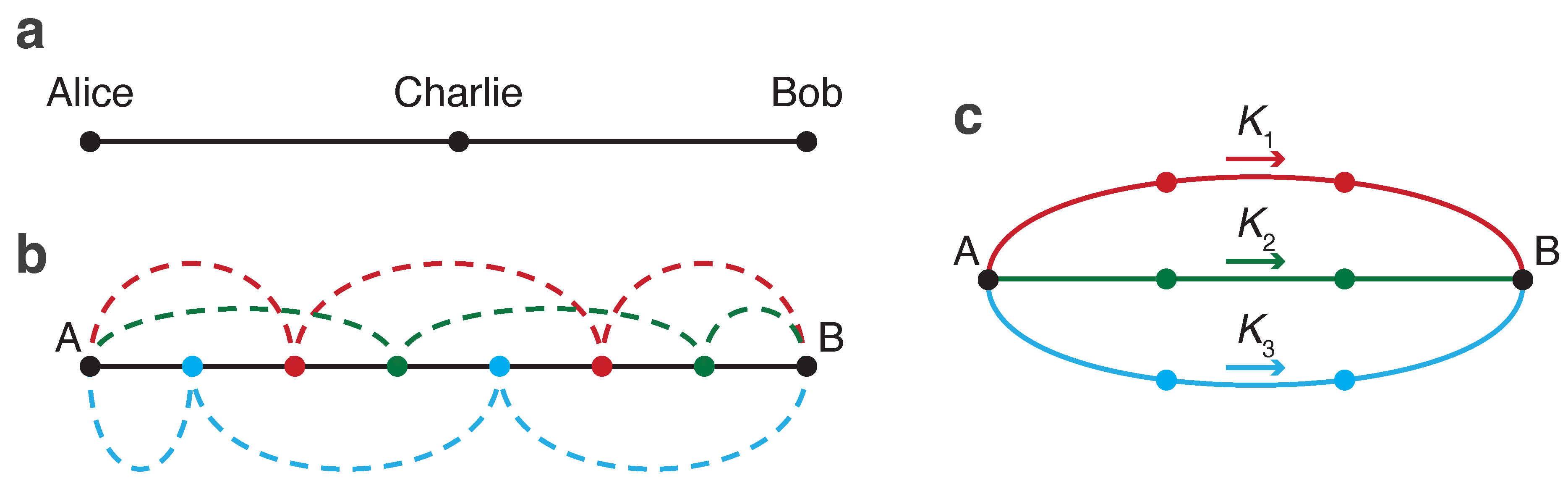

Consider a network with three users, Alice, Charlie, and Bob, connected via a direct quantum channel, see

Figure 6a; each pair of users is also linked via a classical authenticated channel, which is not depicted. Each user is equipped with a switch that enables the reception of signals through this channel or the bypassing of signals to the intended receiver. When Alice initiates a signal transmission to her adjacent neighbor, Charlie, he must fully capture and measure it, blocking the next participant, Bob, from this transmission. Alternatively, if Alice targets her signal for Bob, Charlie’s switch must be configured to direct the signal exclusively to Bob. A critical aspect of the proposed communication system is the ability of the users to monitor channel losses end-to-end. This allows Alice and Bob to ascertain that Charlie does not intercept, or even partially accesses, the signal when it is not designated for him. Upon detecting any unauthorized intervention by Charlie, such as signal tapping, the transmission is immediately terminated and the affected bits are discarded. The classical authenticated channels enable user coordination, allowing them to decide who and in what order will participate in the key distribution.

While it is feasible for the sender to transmit the key directly to the recipient bypassing all intermediate nodes, this approach may not always be viable due to the decrease of the key rate with an increasing distance. Therefore, instead of bypassing all intermediate users, it may be more advantageous to bypass only some of them. The others would then act as trusted nodes, measuring the signal and resending it; we will refer to these users as

reproducers. In this scenario, the sender and recipient may employ the secret sharing scheme [

45,

46,

47]. Consider the one-dimensional network depicted in

Figure 6b. Within this user chain, three different initial keys,

,

, are

, are distributed via different sets of reproducers, marked as red, green, or blue. By controlling leakages across the entire line – either collectively or through some central entity that does not have access to the keys themselves – it is ensured that only the designated group of reproducers handles a specific initial key. Thus, while each group of reproducers knows their respective

, they lack knowledge of the other initial keys. The final key,

K, is composed of all initial keys (e.g., through a hashing algorithm,

) and remains unknown to any of the reproducers. The introduced control mechanism effectively increases the connectivity of the QCKD network: what was initially a simple one-dimensional user chain in

Figure 6b becomes equivalent to a more interconnected network with multiple branches, as illustrated in

Figure 6c.

The design of the switches remains a subject for future investigation. Key requirements for such switches include minimal local leakage and the capability for extreme transmittivity control, meaning the switch should either fully transmit or completely block the signal. Potential designs for these switches might encompass configurations like the Mach-Zehnder interferometer, incorporating beam splitters and at least one phase modulator, as well as other optical elements such as microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), lithium niobate (LiNbO3), and optomechanical components.

8. Discussion

We have demonstrated the practical implementation and performance of the QCKD over an extensive 1,707 km fiber line. We have shown the robustness of the system’s various components, in particular, the effectiveness of equipment, including the Terra Quantum-made BEDFAs and loss control, and advantage distillation procedure. These developments collectively enhance the scalability of the QCKD solution, enabling quantum-protected communication over the unprecedented distances. Furthermore, we have discussed the potential of the QCKD in multi-user key distribution, paving the way for broader applications. The subject of the QCKD networks will be further studied in our next paper.

A notable feature of the keys generated via the boosted QCKD is their everlasting security, which is inherent to quantum cryptography [

48]. Unlike in classical cryptography, once the keys are securely distributed through the QCKD, it is impossible to compromise them by attacking the QCKD hardware, including the loss control components. Our findings establish the advantage of the device-dependent quantum cryptography and underscore its remarkable capacity.

9. Methods

9.1. Chromatic Dispersion Effect

Long distance transmission of optical signals usually faces the problem of chromatic dispersion [

49]. Chromatic dispersion is the variation in the refractive index of an electromagnetic wave across different optical frequencies. When an optical pulse propagates, it travels at the group velocity, but the phenomenon known as group-velocity dispersion (GVD) contributes to the widening or broadening of the pulse. The effect blurs the bit encoding wave packets so the adjacent ones partially overlap. In the case of the key distribution, this may cause additional errors and limit the key rate [

50,

51,

52].

We estimate the influence of chromatic dispersion on a single pulse, which is presented in the form of a super-Gaussian pulse at the beginning of the transmission line. The amplitude’s dependence on time

T for a super-Gaussian pulse is proportional to

. In our case,

and

ns. The relative time broadening of such a pulse can be calculated according to the following equation, see Chapter 3 in Ref. [

49]

where

is the gamma function,

z is the transmission distance and

is the GVD constant. In our case of 1,530 nm wavelength,

. The resulting broadening

at distance of 1,707 km is only

of the initial time width and can be considered insignificant compared to the time interval between adjacent pulses, which is about 5 ns.

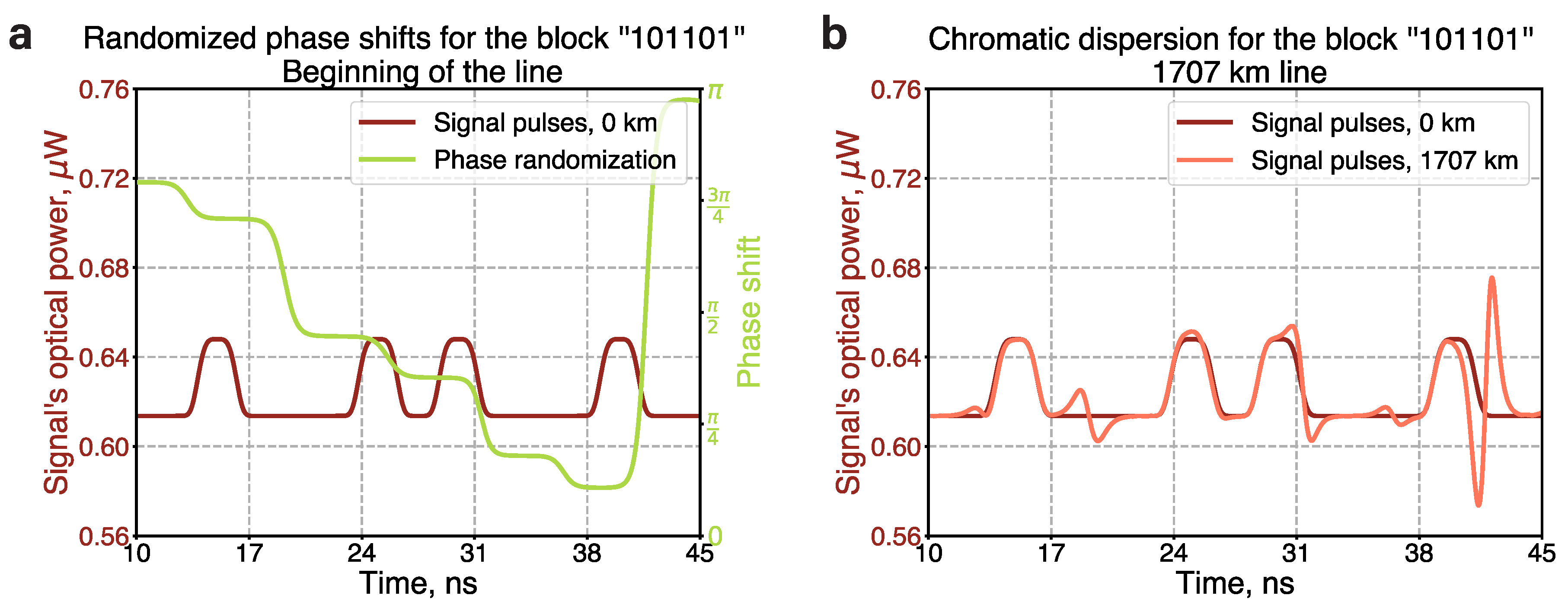

In the case of phase randomization, chromatic dispersion significantly alters the temporal shapes of propagating pulses. We conduct numerical simulations to examine the evolution of bit-encoding wave packets for a representative sequence of phase-randomized pulses.

Figure 7a illustrates the temporal profile of optical pulses corresponding to the bit sequence “101101” and randomized phase shifts. The amplitude of the initial signal is multiplied by a phase factor determined by the green curve. After propagating through the whole 1,707 km line, the shapes of the pulses are altered at moments corresponding to the phase shift switching, as shown in

Figure 7b. However, the total number of photons (or energy) in each pulse remains constant.

Consequently, in the case of the photon number encoding scheme implemented in this experiment, chromatic dispersion does not impact the key distribution, as the modification of the pulses’ temporal profiles does not influence the measurement results. However, in the scenario of shape coding—where bits are encoded into the temporal profiles of the pulses—the legitimate users should either refrain from phase randomization or employ methods to mitigate chromatic dispersion [

53].

9.2. Advantage Distillation Specifics

The advantage distillation procedure is schematically shown in

Figure 8. The exemplary raw string of the length 36 bits is divided into 12 blocks. For each block

a, Alice announces

a and

and the rule according to which blocks will be translated to the bits of the new string. If Bob’s block coincides with

a or

, it gets transformed into one bit of a new string, see 2nd, 3rd, 6th, 8th, 10th, and 11th blocks on

Figure 8, otherwise it gets discarded. The length of blocks,

M, should be chosen in accordance with the observed parameters (the raw BER,

, and leakage,

) to achieve the maximally attainable key rate.

In the most general case, Eve’s information

, appearing in Equation (

1), depends on the pair of block’s values between which the eavesdropper has to distinguish,

. The estimate of the intercepted information is given by the maximal value of the Holevo bound [

54] for all the ensembles corresponding to different blocks

a:

where Eve’s ensemble, conditioned on Alice announced block

a, is the following

Here

stands for the

i-th bit of block

a and

is Eve’s density matrix for this single bit

. Such an ensemble appears when Eve possess quantum memory and can maintain intercepted states until blocks’ announcements.

The density matrix of Eve for a single bit is influenced by the position of the leakage and the state coming from Alice’s end. In this work, we consider that the adversary’s intrusion occurs immediately after Alice. Ideally, Alice prepares a pure coherent state with an amplitude

and randomizes its phase. However, in our experimental setup, the electronics controlling the amplitude modulation of the generated states, see

Figure 1, do not provide a predetermined value of controlling voltage for a fixed bit of a key. Consequently, for a given bit

, Alice prepares a mixture of phase-randomized coherent states with a probability distribution

, which is determined by the electronics in the amplitude modulator. The density matrix of the eavesdropper’s subsystem can be written as

Substituting Equations (

4) and (

5) into Equation (

3), we upper bound the eavesdropper’s information. The estimation is in turn utilized for computing secret key generation rate according to the Equation (

1), the results are depicted in

Figure 4.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Nikita Kirsanov, Markus Pflitc and Valerii Vinokur; Data curation, Nikita Kirsanov, Valeria Pastushenko, Aleksei Kodukhov, Aziz Aliev, Michael Yarovikov, Ilya Zarubin, Alexander Smirnov and Valerii Vinokur; Formal analysis, Valeria Pastushenko, Aleksei Kodukhov and Valerii Vinokur; Investigation, Nikita Kirsanov and Valerii Vinokur; Methodology, Valeria Pastushenko, Aleksei Kodukhov, Aziz Aliev, Daniel Strizhak, Ilya Zarubin and Alexander Smirnov; Resources, Daniel Strizhak; Software, Daniel Strizhak and Ilya Zarubin; Supervision, Valerii Vinokur; Writing – original draft, Nikita Kirsanov, Valeria Pastushenko, Aleksei Kodukhov, Aziz Aliev, Michael Yarovikov , Daniel Strizhak, Ilya Zarubin, Alexander Smirnov and Valerii Vinokur; Writing – review & editing, Nikita Kirsanov and Valerii Vinokur.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The supporting data for the findings drawn in this research are present within the main article. The source data can be obtained from the authors upon a request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Terra Quantum AG.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADC |

Analog-to-Digital Converter |

| AM |

Amplitude Modulator |

| BEDFA |

Bidirectional Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifier |

| BER |

Bit Error Rate |

| BS |

Beam Splitter |

| EDFA |

Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifier |

| FPGA |

Field-Programmable Gate Array |

| GVD |

Group-Velocity Dispersion |

| MEMS |

Microelectromechanical System |

| OTDR |

Optical Time-Domain Reflectometry |

| PM |

Phase Modulator |

| QCKD |

Quantum-protected Control-based Key Distribution |

| QKD |

Quantum Key Distribution |

| QRNG |

Quantum Random Number Generator |

| RSG |

Random Signal Generator |

| WDM |

Wavelength-Division Multiplexing |

References

- Pirandola, S.; Laurenza, R.; Ottaviani, C.; Banchi, L. Fundamental limits of repeaterless quantum communications. Nat. Comm. 2017, 8, 15043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.-J.; Jiang, C.; Chen, J.-P.; Zhang, C.; Pan, W.-X.; Ma, D.; Dong, H.; Xiong, J.-M.; Zhang, C.-J.; Li, H.; Wang, R.-C.; Wu, J.; Chen, T.-Y.; You, L.; Wang, X.-B.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, J.-W. Experimental twin-field quantum key distribution over 1000 km fiber distance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 210801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Lin, J.; Jing, Y.; Yuan, Z. Twin-field quantum key distribution without optical frequency dissemination. Nat. Comm. 2023, 14, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.-L.; Chen, T.-Y.; Yu, Z.-W.; Liu, H.; You, L.-X.; Zhou, Y.-H.; Chen, S.-J.; Mao, Y.; Huang, M.-Q.; Zhang, W.-J.; Chen, H.; Li, M. J.; Nolan, D.; Zhou, F.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.-B.; Pan, J.-W. Measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution over a 404 km optical fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 190501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-K.; et al. Satellite-to-ground quantum key distribution. Nature 2023, 549, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boaron, A.; Korzh, B.; Houlmann, R.; Boso, G.; Rusca, D.; Gray, S.; Li, M.-J.; Nolan, D.; Martin, A.; Zbinden, H. Simple 2.5 GHz time-bin quantum key distribution. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112, 171108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaron, A.; et al. Secure quantum key distribution over 421 km of optical fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett., 2018, 121, 190502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briegel, H.-J.; Dür, W.; Cirac, J. I.; Zoller, P. Quantum repeaters: The role of imperfect local operations in quantum communication. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 5932–5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.-M. Lukin, M. D.; Cirac, J. I.; Zoller, P. Long-distance quantum communication with atomic ensembles and linear optics. Nature 2001, 414, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, P.; Williams, C. P.; Dowling, J. P. Construction of a quantum repeater with linear optics. Phys. Rev. A 2003, 68, 022301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangouard, N.; Simon, C.; de Riedmatten, H.; Gisin, N. Quantum repeaters based on atomic ensembles and linear optics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 33–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-J.; Song, S.-Y.; Long, G. L. Quantum repeater based on spatial entanglement of photons and quantum-dot spins in optical microcavities. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 062311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwerger, M.; Dür, W.; Briegel, H. J. Measurement-based quantum repeaters. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 062326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsanov, N. S.; Pastushenko, V. A.; Kodukhov, A. D.; Yarovikov, M. V.; Sagingalieva, A. B.; Kronberg, D. A.; Pflitsch, M.; Vinokur, V. M. Forty thousand kilometers under quantum protection. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliev, A.; Statiev, V.; Zarubin, I.; Kirsanov, N.; Strizhak, D.; Bezruchenko, A.; Osicheva, A.; Smirnov, A.; Yarovikov, M.; Kodukhov, A.; Pastushenko, V. Pflitsch, M.; Vinokur, V. Experimental demonstration of scalable quantum key distribution over a thousand kilometers. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.04599. [Google Scholar]

- Barnoski, M.; Rourke, M.; Jensen, S.; Melville, R. Optical time domain reflectometer. Appl. Optics. 1977, 16, 2375–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Personick, S. Photon probe—an optical-fiber time-domain reflectometer. The Bell System Technical Journal. 1977, 56, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, P. M.; Olsson, A. A.; Simpson, J. R. Erbium-doped fiber amplifiers: Fundamentals and technology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA 92101–4495, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Desurvire, E.; Bayart, D.; Desthieux, B.; Bigo, S. Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers: Device and System Developments; A John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; publication, 2002.

- Kim, S.-J.; Koh, K.; Boyd, S.; Gorinevsky, D. ℓ1 trend filtering. SIAM Rev. 2009, 51, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, R.; Verbauwhede, I. Physically Unclonable Functions: A Study on the State of the Art and Future Research Directions. In Towards Hardware-Intrinsic Security Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 3–37.

- Du, Y.; Jothibasu, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Huang, J. Unclonable optical fiber identification based on Rayleigh backscattering signatures. J. Lightwave Technology. 2017, 35, 4634–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goki, N. P.; Mulugeta, T.T.; Caldelli, R.; Potì, L. Optical Systems Identification through Rayleigh Backscattering. Sensors 2023, 23, 5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goki, N.; Civelli, S.; Parente, E.; Caldelli, R.; Mulugeta, T. M.; Sambo, N.; Secondini, M. Potì, L. Optical identification using physical unclonable functions. J. Optical Communications and Networking 2023, 15, E63–E73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.; Yarovikov, M.; Zhdanova, E.; Gutor, A.; Vyatkin, M. An optical-fiber-based key for remote authentication of users and optical fiber lines. Sensors 2023, 23, 6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portmann, C.; Renner, R. Security in quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2022, 94, 025008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, U. M. Secret key agreement by public discussion from common information. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1993, 39, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, D.; Lo, H.-K. Proof of security of quantum key distribution with two-way classical communications. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2023, 49, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, B.; Branciard, C.; Renner, R. Security of quantum-key-distribution protocols using two-way classical communication or weak coherent pulses. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 75, 012316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Acín, A. Key distillation from quantum channels using two-way communication protocols. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 75, 012314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E. Y.-Z.; Lim, C. C.-W.; Renner, R. Advantage distillation for device-independent quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 020502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.-L.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.-J.; Lu, Y.-F.; Hao, C. P.; Zhou, C.; Bao, W.-S. Improving the performance of reference-frame-independent quantum key distribution with advantage distillation technology. Optics Express 2023, 31, 9196–9210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-W.; Wang, R.-Q.; Zhang, C.-M.; Cai, Q.-Y. Improving the performance of twin-field quantum key distribution with advantage distillation technology. Quantum 2023, 7, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devetak, I.; Winter, A. Distillation of secret key and entanglement from quantum states. Proc. Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2005, 461, 207–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodukhov, A. D.; Pastushenko, V. A.; Kirsanov, N. S.; Kronberg, D. A.; Pflitsch, M.; Vinokur, V. M. Boosting quantum key distribution via the end-to-end loss control. Cryptography 2023, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastushenko, V. A.; Kronberg, D. A. Improving the performance of quantum cryptography by using the encryption of the error correction data. Entropy 2023, 25, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, C.; Colvin, A.; Pearson, D.; Pikalo, O.; Schlafer, J.; Yeh, H. Current status of the DARPA quantum network. In Quantum Information and Computation III; Donkor, E. J., Pirich, A. R., Brandt, H. E., Eds.; Publishing House: SPIE, International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, Washington, USA, 2005; pp. 138–149. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.-Y.; Liang, H.; Liu, Y.; Cai, W.-Q.; Ju, L.; Liu, W.-Y.; Wang, J.; Yin, H.; Chen, K/.; Chen, Z.-B.; Peng, C.-Z.; Pan, J.-W. Field test of a practical secure communication network with decoy-state quantum cryptography. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 6540–6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peev, M.; et al. The SECOQC quantum key distribution network in Vienna. New J. Phys. 2009, 11, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvail, L.; Peev, M.; Diamanti, E.; Alléaume, R.; Lütkenhaus, N.; Länger, T. Security of Trusted Repeater Quantum Key Distribution Networks. J. Computer Security 2010, 18, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucki, D.; et al. Long-term performance of the Swissquantum quantum key distribution network in a field environment. New J. Phys. 2011, 13, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; et al. Field test of quantum key distribution in the Tokyo QKD network Opt. Express. 2011, 19, 10387–10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, B.; Dynes, J. F.; Lucamarini, M.; Sharpe, A. W.; Yuan, Z.; Shields, A. J. A quantum access network. Nature 2013, 501, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiktenko, E.; et al. Demonstration of a quantum key distribution network in urban fibre-optic communication lines. Quantum Electron. 2017, 47, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneier, B. Applied Cryptography, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gruska, J. Foundations of Computing. Thomson Computer Press: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hillery, M.; Bužek, V.; Berthiaume, A. Quantum secret sharing. Phys. Rev. A 1999, 59, 1829–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, R.; Wolf, R. Quantum Advantage in Cryptography. AIAA Journal. 2023, 61, 1895–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, G. P. Nonlinear Fiber Optics. In Nonlinear Science at the Dawn of the 21st Century; Christiansen, P. L., Sørensen, M. P., Scott, A. C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 195–2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mlejnek, M.; Kaliteevskiy, N. A.; Nolan, D. A. Reducing spontaneous Raman scattering noise in high quantum bit rate QKD systems over optical fiber. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.05891. [Google Scholar]

- Mlejnek, M.; Kaliteevskiy, N. A.; Nolan, D. A. Modeling high quantum bit rate QKD systems over optical fiber. In Quantum Technologies 2018 vol. 10674; Stuhler, J. Shields A.,J.; Scott, A. C.; Padgett, M. J. Eds.; SPIE, 2018; p. 1067416.

- Kiselev, F.; Samsonov, E.; Goncharov, R.; Chistyakov, V.; Halturinsky, A.; Egorov, V.; Kozubov, A.; Gaidash, A.; Gleim, A. Analysis of the chromatic dispersion effect on the subcarrier wave QKD system. Optics Express. 2020, 28, 28696–28712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, S. P.; Ribezzo, D.; Bohmann, M.; Ursin, R. Experimentally optimizing QKD rates via nonlocal dispersion compensation. Quantum Science and Technology. 2021, 6, 025017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holevo, A. S. Bounds for the quantity of information transmitted by a quantum communication channel. Problems of Information Transmission. 1973, 9, 177–183. [Google Scholar]

Figure 2.

The OTDR leakage detection in the 1,707 km-long fiber line. (a) Detailed reflectogram of the entire 1,707 km line, featuring 32 optical amplifiers. The measurements are conducted at a 1,530 nm wavelength and with a probing pulse duration of 200 ns; the reflectogram represents an average of 5,000 individual probing pulses’ runs. (b) Enhanced view of the 50 km segment near the end of the line: the reflectogram displays six local leakages (fusion splices), deliberately introduced to demonstrate the capacity of the loss control. (c) Loss profile for the same 50 km segment, illustrating leakage measured in relation to the local power immediately preceding each leakage point. (d) Same loss profile, but with leakage quantified in relation to the initial input power.

Figure 2.

The OTDR leakage detection in the 1,707 km-long fiber line. (a) Detailed reflectogram of the entire 1,707 km line, featuring 32 optical amplifiers. The measurements are conducted at a 1,530 nm wavelength and with a probing pulse duration of 200 ns; the reflectogram represents an average of 5,000 individual probing pulses’ runs. (b) Enhanced view of the 50 km segment near the end of the line: the reflectogram displays six local leakages (fusion splices), deliberately introduced to demonstrate the capacity of the loss control. (c) Loss profile for the same 50 km segment, illustrating leakage measured in relation to the local power immediately preceding each leakage point. (d) Same loss profile, but with leakage quantified in relation to the initial input power.

Figure 3.

Unique backscattering patterns at 1,700 km. (a) Two reflectograms (blue and green traces) correspond to successive measurements of the last 4 km-long fiber section. Both reflectograms are obtained at a 1,530 nm wavelength, with the duration of the probing pulse being 200 ns and averaging over 5,000 pulses. (b) Subtracting the linear component of the reflectograms yields reproducible patterns of the backscattered signal, which correlate with a coefficient of 0.95.

Figure 3.

Unique backscattering patterns at 1,700 km. (a) Two reflectograms (blue and green traces) correspond to successive measurements of the last 4 km-long fiber section. Both reflectograms are obtained at a 1,530 nm wavelength, with the duration of the probing pulse being 200 ns and averaging over 5,000 pulses. (b) Subtracting the linear component of the reflectograms yields reproducible patterns of the backscattered signal, which correlate with a coefficient of 0.95.

Figure 4.

Secret key generation rate as a function of the observed parameters for different values of the block’s length M. We take that Eve is located right after Alice’s side, and the probability of a conclusive bit measurement result is . (a) Key rate dependence on BER (), asymptotic limit. (b) Key rate dependence on BER (), the statistical fluctuations are taken into account. (c) Key rate dependence on (), asymptotic limit. (d) Key rate dependence on (), the statistical fluctuations are taken into account.

Figure 4.

Secret key generation rate as a function of the observed parameters for different values of the block’s length M. We take that Eve is located right after Alice’s side, and the probability of a conclusive bit measurement result is . (a) Key rate dependence on BER (), asymptotic limit. (b) Key rate dependence on BER (), the statistical fluctuations are taken into account. (c) Key rate dependence on (), asymptotic limit. (d) Key rate dependence on (), the statistical fluctuations are taken into account.

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of the key rates achieved at various transmission distances using our experimental setup. The key rate of 0.9 bps is achieved over the 1,707 km line. Additional key rates for other transmission lengths are obtained with the similar equipment. All results correspond to the asymptotic limit.

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of the key rates achieved at various transmission distances using our experimental setup. The key rate of 0.9 bps is achieved over the 1,707 km line. Additional key rates for other transmission lengths are obtained with the similar equipment. All results correspond to the asymptotic limit.

Figure 6.

The simplest QCKD networks. (a) Tripartite network where the users, Alice, Bob, and Charlie, are linked by a single quantum channel. Alice can send a key to either Bob or Charlie. Depending on who is the intended recipient, Charlie needs to alternate between receiving and transmitting modes (under the watchful eye of Alice and Bob). (b) Within a linear chain of users, User A has the option to transmit keys to User B through various sets of reproducers. These sets, colored red, green, and blue, provide different pathways for the keys. (c) A network structure equivalent to (b). User A distributes different initial keys (, , and ) through the red, green, and blue sets of reproducers, respectively. As these sets are mutually exclusive, no single reproducer has knowledge of the entire final key .

Figure 6.

The simplest QCKD networks. (a) Tripartite network where the users, Alice, Bob, and Charlie, are linked by a single quantum channel. Alice can send a key to either Bob or Charlie. Depending on who is the intended recipient, Charlie needs to alternate between receiving and transmitting modes (under the watchful eye of Alice and Bob). (b) Within a linear chain of users, User A has the option to transmit keys to User B through various sets of reproducers. These sets, colored red, green, and blue, provide different pathways for the keys. (c) A network structure equivalent to (b). User A distributes different initial keys (, , and ) through the red, green, and blue sets of reproducers, respectively. As these sets are mutually exclusive, no single reproducer has knowledge of the entire final key .

Figure 7.

Numerical simulations of the influence of chromatic dispersion on phase-randomized signal pulses propagating along a 1,707 km line. (a) Temporal profile of signal’s optical power for a bit sequence “101101” (dark red curve) and temporal profile of randomized phase shift (green curve). The time duration of each bit is 2 ns. The optical power for bits “0” and “1” corresponds to average photon numbers of 10,000 and 10,600, respectively. (b) Temporal profile of the signal’s optical power, influenced by chromatic dispersion (orange curve), at a distance of 1,707 km compared to the initial temporal profile. The shape is modified at moments when the phase shift switches from one value to another.

Figure 7.

Numerical simulations of the influence of chromatic dispersion on phase-randomized signal pulses propagating along a 1,707 km line. (a) Temporal profile of signal’s optical power for a bit sequence “101101” (dark red curve) and temporal profile of randomized phase shift (green curve). The time duration of each bit is 2 ns. The optical power for bits “0” and “1” corresponds to average photon numbers of 10,000 and 10,600, respectively. (b) Temporal profile of the signal’s optical power, influenced by chromatic dispersion (orange curve), at a distance of 1,707 km compared to the initial temporal profile. The shape is modified at moments when the phase shift switches from one value to another.

Figure 8.

Schematics of the advantage distillation procedure. Alice divides the raw string into blocks of the length M (here, ). For every block, Alice publicly announces two pieces of information: the block’s actual value and its bitwise inverse (without telling which one is which). If Bob’s block does not match either of the values Alice announced, both Alice and Bob discard that particular block (the discarded blocks are marked as “×”). The remaining blocks are translated into a new bit string with a lower BER (we mark a new bit which is incorrect).

Figure 8.

Schematics of the advantage distillation procedure. Alice divides the raw string into blocks of the length M (here, ). For every block, Alice publicly announces two pieces of information: the block’s actual value and its bitwise inverse (without telling which one is which). If Bob’s block does not match either of the values Alice announced, both Alice and Bob discard that particular block (the discarded blocks are marked as “×”). The remaining blocks are translated into a new bit string with a lower BER (we mark a new bit which is incorrect).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).