1. Introduction

In recent years, the use of virtual reality applications by the elderly has increased rapidly [

1,

2]. A number of research studies concluded that virtual reality applications have the potential to positively influence elderly users to entertain themselves through virtual games [

3], to provide a means for exercising in virtual spaces [

4,

5] or to support them in dealing with fears [

6]. Along these lines, the aim of our work is to design and evaluate a user friendly and enjoyable Virtual Reality application that can support elder users in dealing with the effects of loneliness and social isolation [

7] that are common among the elderly population. The proposed application presents familiar photographs of elderly users in a VR environment, where apart from the photographs it contains a virtual audience that acts as a virtual companion to the user. Familiar photographs presented aim to awaken emotions, either positive or negative, of the users who are asked to narrate memories from their younger years and discus their memories with the virtual audience though a storytelling experience. Within this context, photographs displayed in the application aim to activate a memory recalling experience, and the presence of a virtual audience aims to motivate users to engage in storytelling, so that the feelings of loneliness and social isolation are compacted. The ultimate purpose of the research is to study whether the users of the proposed virtual reality application believe that it has the potential to improve the emotional state of the users with regards to the feelings of loneness, joy and well-being. Experimental results derived through the evaluation of the application by elderly users indicate that the use of the proposed application is well received by the target population since most users were positive on using it to reduce the feeling of loneliness and social isolation.

In the remainder of the paper, we present a literature review on the topic of virtual reality applications and the elderly. The multi-phase co-design methodology used for designing and implementing the VR application is presented in section 3, and in

Section 4 the final VR application is described.

Section 5 focuses on the experimental evaluation of the VR application based on interviews and questionnaires. A discussion about the results of the experiment is presented in section 6 and conclusions and plans for future work are presented in section 7.

2. Literature Review

Encouraging the integration of older adults with contemporary technology is widely advocated. Beyond connecting with loved ones, technology aids seniors in enhancing social connections, accessing valuable health information, participating in civic decision-making, and maintaining physical well-being through specialized fitness applications [

8]. Several applications designed in a human-centered design approach, aimed at motivating older people to use applications for the benefit of their health, are reported in the literature. Mostajeran et al. [

9] describe the design of an augmented reality application where virtual coaches provide a solution to elderly people who face balance problems and are at risk of falling. Rose et al. [

10] investigated the challenges during the design and implementation of a VR system, for physical training for patients with dementia. Lera at al. [

11] detail architecture for human-robot interaction known as MYRA, employed in the development of a system assisting the elderly with medical dose management. This system incorporates augmented reality (AR) to enhance robot interaction. The prototype allows users to easily adhere to medical guidelines for daily pill dosage by presenting the pillbox to the robot or a camera, facilitated by augmented reality. The study concludes that the integration of AR has demonstrated positive effects on user experience.

Virtual reality holds great promise as a tool that could improve the treatment of cognitive and emotional disorders in the elderly. While VR applications have been successfully used in clinical environments with adolescents and children, there has been comparatively less research conducted on its application in the geriatric population [

12]. Gao et al. [

13] asserts that virtual reality technology serves as a valuable tool for effectively treating the elderly. This involves utilizing non-immersive virtual reality in corridor settings or immersing patients in realistic environments, such as urban landscapes or parks, through head-mounted displays or within a CAVE system. This approach enhances physical and occupational therapy sessions, thereby elevating the likelihood of successful adaptation to the real world. There are many applications related to user’s reactions [

14] when they interact with virtual audiences in VR applications. Most of these applications target the therapy of users who fear presenting to a real audience.

There is insufficient empirical research on the use of immersion technology and immersion experience of elder users. The results of previous studies show that immersion experiences are related to physical, mental, and social functions of the elderly, especially video game-based educational games that can be beneficial in improving sensory and motor skills, perception, and knowledge and also assist in forming relationships with grandchildren. Artificial intelligence-based robots used for social care promote social exchange and emotional relaxation, and the use of exciting content can enhance life satisfaction and family ties [

15]. Lin [

16] sought to study and understand how virtual reality will affect the emotional and social well-being of the elderly through the Rendever VR platform. The study was conducted with sixty-three residents from four assisted communities and lasted two weeks where residents interacted with one of two intervention conditions—VR (i.e. experimental mode) or television (i.e. control status). The results showed that VR provided more positive results than the control group that used a TV with the same content. The researcher concludes that VR has the potential to improve the well-being of the elderly.

Ma et al. [

17] study indicates that employing virtual reality for mindfulness training is a successful and inventive approach for enhancing mental health conditions among adults. Along these lines, Matsangidou et al. [

18] explores challenges encountered in developing, testing, and implementing a virtual reality system for physical training tailored to individuals with moderate to severe dementia. The system was introduced in a confined mental health unit, leading to the formulation of recommendations for the design of virtual reality systems in healthcare. Employing an iterative participatory design approach, health experts from various fields and 20 individuals with moderate to severe dementia contributed their insights. The analysis highlights the potential of virtual reality physical training for people with dementia and offers a set of guidelines and recommendations for future healthcare deployment. It is thought that encouraging people with generalized anxiety disorder to perform aerobic exercise as a stress-reduction strategy can be accomplished through virtual exercise therapy [

19]. Tammy Lin et al. [

20] study showed that the Proteus effect, which involves adjusting avatar age in virtual reality, works well for older people when they exercise. The findings demonstrated that, for older individuals who did not participate in strenuous exercise, the virtual reality embodiment of younger avatars causes a larger perceived exertion of exercise.

Following an extensive review of the literature, it was determined that our research diverges in specific aspects, prompting a desire for further exploration in those particular areas. Initially, the involvement of the virtual audience to interact with the user through physical presence in the virtual space and through audio instructions. Furthermore, the proposed application focuses on simplicity and execution on low cost VR devices, allowing in that way elder users to use the application without requiring extra assistance or dedicated equipment. Finally, it should be noted that the application is not aimed at medical treatment but it aims to improving the overall wellbeing of elder uses aiming at the prevention, rather than the treatment, of mental disabilities.

3. VR Application Design Methodology

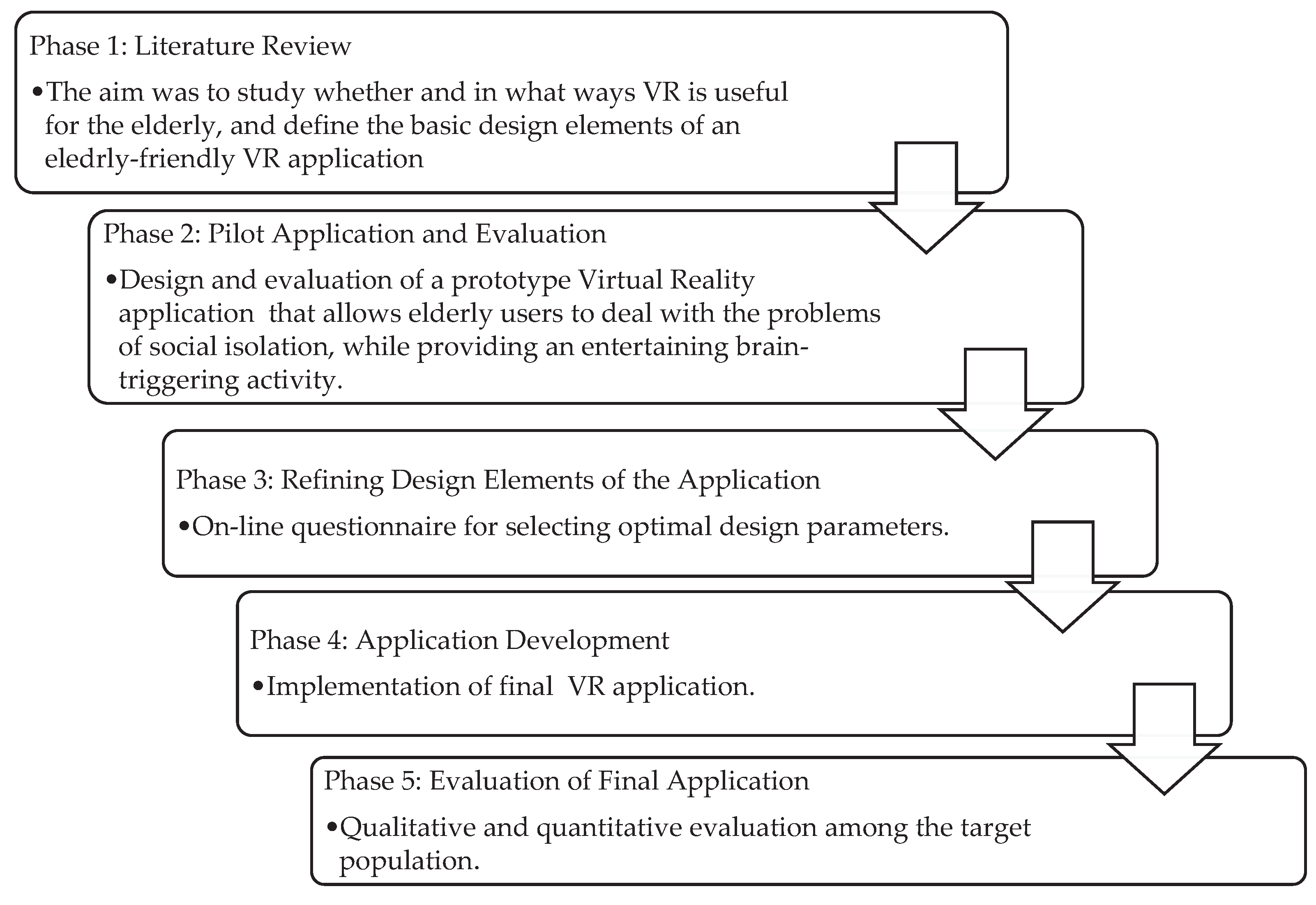

The development of the proposed VR application followed a multi-phased co-design approach with the active participation of groups of people related to elderly, such as care givers, medical personnel and elderly users. Furthermore, professionals with expertise in the development of Virtual Reality applications were also involved in the design process. The main phases of the design (see

Figure 1) include the literature review in relation to user requirements and previous approaches in designing VR applications for the elderly, the design and evaluation of a pilot test application, the refinement of design elements of the application through a questioner-based approach, the development of the final application, and the evaluation of the application with the target population of elderly users. This paper focuses on the last two phases of the design process. However, brief descriptions of the remaining phases are also presented.

Phase 1- Literature Review: The aim of the literature review was to determine the needs of the elderly, and study age-related difficulties and weaknesses that should be taken into consideration for designing an elderly friendly VR application. In addition, previous approaches in developing VR applications for the elderly population were studied.

Phase 2- Pilot Application and Evaluation: A prototype Virtual Reality tool that allows elderly users to deal with the problems of social isolation, while providing an entertaining brain-triggering activity, was developed. An initial user evaluation provided information related to the strengths and limitations of the prototype application that guided the process of optimizing the application for elderly users [

21].

Phase 3- Refining Design Elements of the Application: Based on the outcome of the evaluation of the pilot application, several design elements were refined through a questionnaire-based data gathering process, where participants rated different design options for the final application. Design elements under evaluation included the choice of the subject, number, and chronological period of the photographs portrayed in the application. Also, another important parameter studied in this phase was the characteristics of the virtual audience that appears in the VR application so that the impact of the application is optimized [

22].

Phase 4- Application Development: Having collected information’s that identified the target audience’s needs, the final application was developed.

Phase 5- Evaluation of Final Application: A comprehensive evaluation of the final application by members of the target population was carried out, and conclusions related to the effectiveness of the application were derived.

More details of Phases 4 and 5 are presented in subsequent sections.

4. VR Application Description

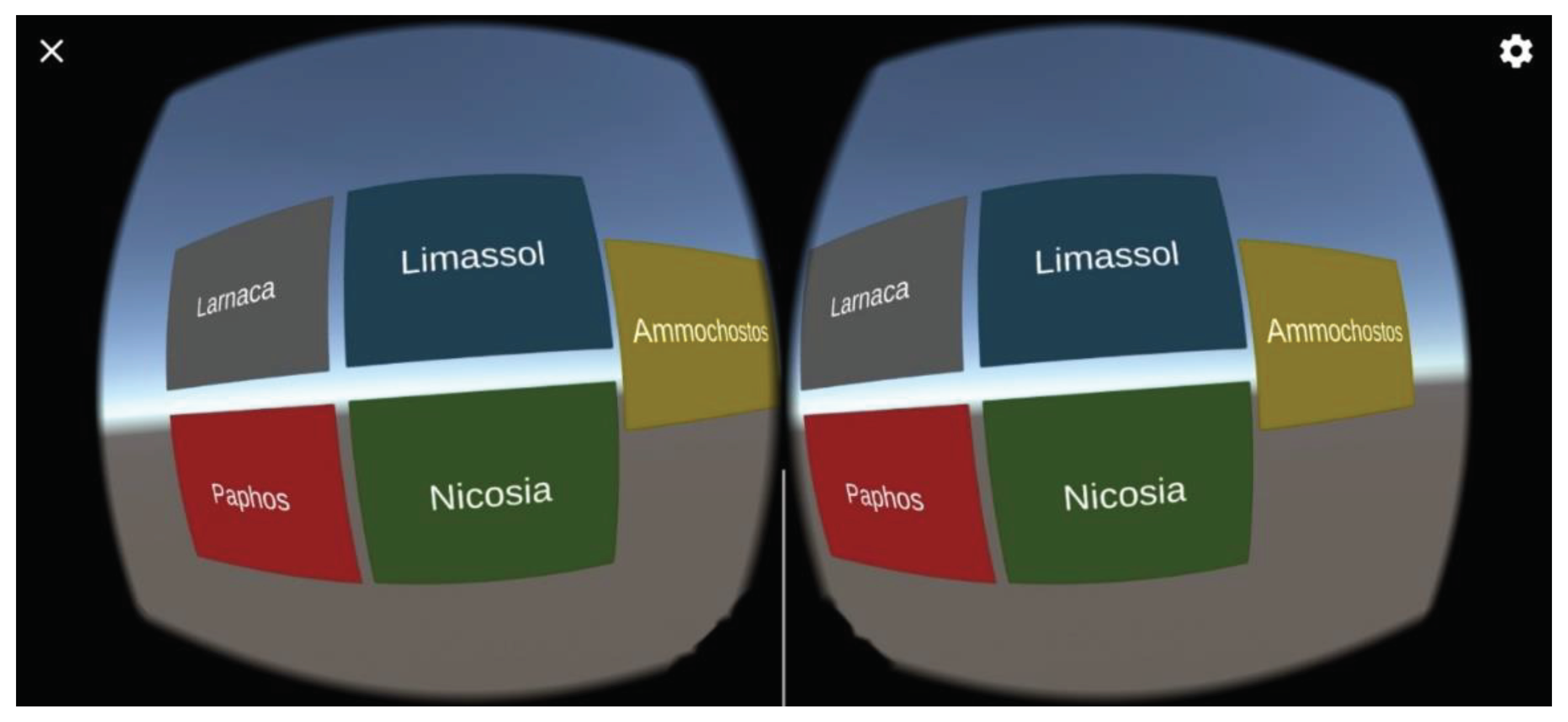

In this section a description of the operation of the VR application is presented. The VR application runs on VR-compatible smartphones in conjunction with the use of low-cost VR headsets. When the application starts, instructions are provided to the user explaining how to use the application. Then, the user is asked to indicate his/her place of origin so that appropriate photographs are selected (see

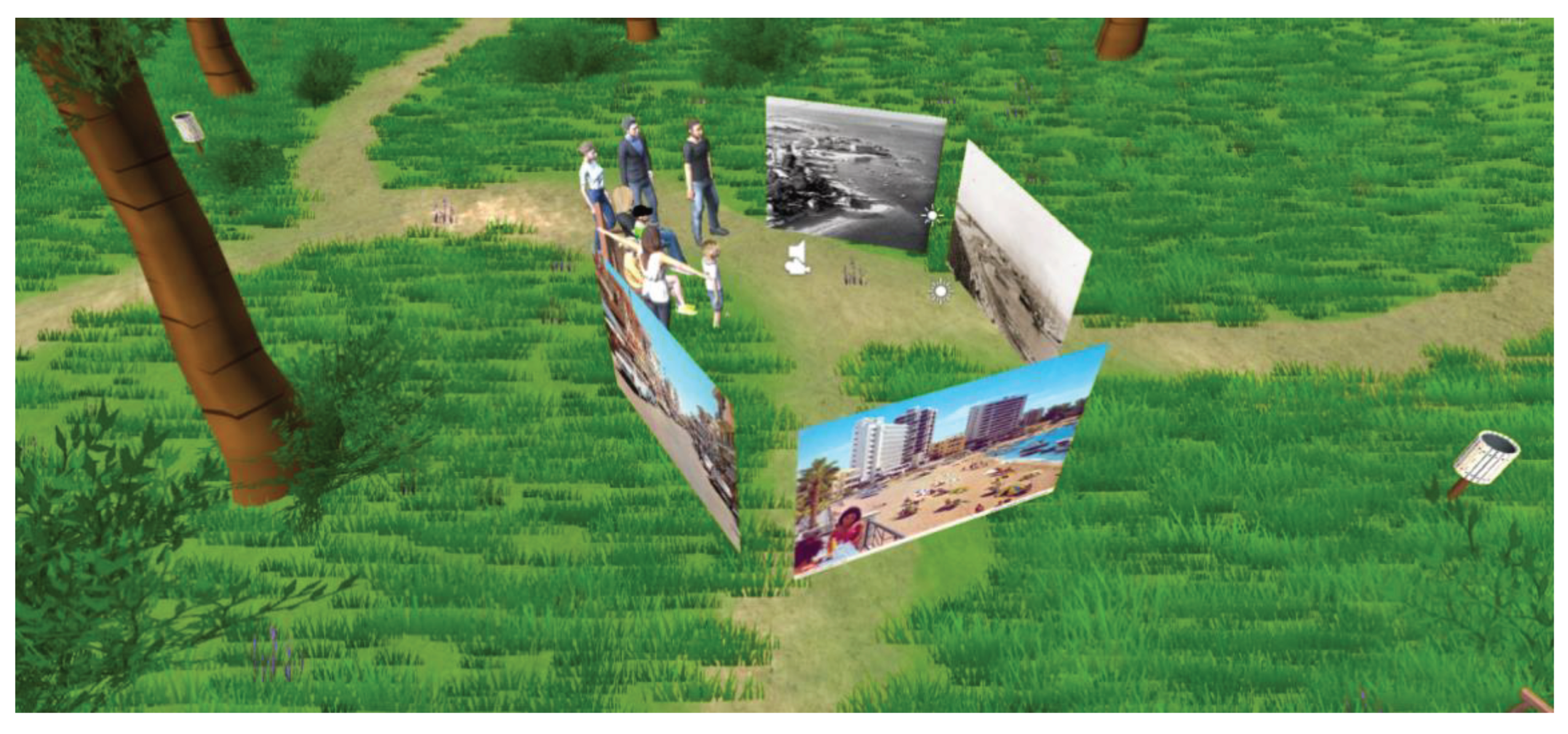

Figure 2) and then the user is instructed to place his/her smartphone in the VR headset. When the user wears the headset he/she is immersed in a scene showing a forest, billboards displaying the selected photographs, and a virtual audience. Four billboards with photographs attached are placed in a circular order so that user is able to view all photographs just by turning his/her head around 180 degrees (see

Figure 3).

In line with feedback obtained during the design process, the virtual audience consists of seven avatars depicting of adults and children (see

Figure 4) so that the group resembles a family gathering. Avatars are placed near the user so that continuous optical contact between the user and the audience is ensured. Bearing in mind that elder users are more prone to nausea effects when immersed in a VR environment [

23] both the user and the virtual characters do not move around so that effects of nausea [

24] for the user are minimized. However, the virtual characters perform animations so that the user gets the feeling of dealing with real (live) humans [

25]. In order to have interactions with the user, audio instructions are heard from the virtual audience to encourage the user to start the narration. At the same time, low-pitched nature sounds are heard in the background to achieve more immersion and relaxation for the user.

The application was created using the Unity3D platform and is compatible with smartphones, allowing users to utilize it with affordable portable VR headsets. The only prerequisite is for the smartphone to have a gyroscope for tracking user head movements. The cost of a suitable VR headset typically ranges from 5 to 50 Euros, and a compatible smartphone starts at around 150 Euros. Considering that a majority of elderly individuals already possess smartphones, the minimal additional cost is unlikely to deter most users from employing this application in their homes. The primary challenge associated with low-cost VR headsets is an increased risk of cyber-sickness [

24]. To mitigate this issue in the proposed application, the speed of movement is restricted to avoid sudden changes in viewpoint, and users are encouraged to use the application while seated.

To use the audio instructions of the virtual audience, the Narakeet tool [

26] was used so that the voices of the avatars sounded realistic. The application environment as well as some elements of the application has been selected from the Unity Asset Store. The avatars were selected from Unity Asset Store [

27], and the animation was added from Mixamo.com [

28]. The choice of movements selected for this application show typical body movements adopted during a conversation, increasing in that way the fidelity of the virtual audience.

5. Experimental Evaluation

The aim of the evaluation is to assess the impact of the application on elderly users. More specifically we aim to determine whether elder users believe that the proposed VR application could help the elderly to reduce the feelings of social isolation and loneliness, could offer and stimulate the interest of the elderly to start telling stories from their younger years and finally to study whether the application could improve the overall sense of well-being. Other issues related to the usability and attractiveness of the application was also investigated. The following research questions were posed:

Research Question (RQ1): Are elderly people willing to use the virtual reality application?

Research Question (RQ2): Do elderly people believe that the VR application can help to overcome feelings of loneliness?

Research Question (RQ3): Do elderly people believe that the VR application can help to increase their levels of well-being?

5.1. Participants

Fifty volunteers participated in the experiment. To collect a sample of 50 users, we had to attend places frequented by the elderly such as village squares, cafes, churches, rehabilitation centers and nursing homes. The data collection process was not easy since it was a time-consuming process to find participants who were willing, and were able to do the evaluation. For example, users with serious vision, hearing, and other related health problems were not able to participate in the process. Data collection lasted two months. Concerning the participants, 19 (38%) were males, and 31 (62%) were females, with the highest percentage of participants aged 79 years and above. More specifically seven participants were 55-59 years old, nine participants were 60-65 years old, 11 participants were 66-69 years old, three participants were 70-75 years old, and 20 participants were 79 years old and above. With regards to participants’ occupation and mobility level, 76% of them were retired, and 28% had a mobility problem that makes it difficult for them to move. Prior to taking part in the experiment all participants were informed about the purpose of the study and the experimental procedure was explained. Furthermore, the volunteers were informed that they had the right to withdraw their consent to participate in the study at any time. The conduction of the experiment received approval from the National Bioethics Committee, ensuring that all ethical considerations were considered during the experiment.

5.2. Methodology and Instruments

At the beginning of the experiment, the operator presented the subject with the research protocol. The protocol includes information on the purpose of the study, the headset installation procedure, and the VR immersion time. All participants were free to ask any questions they deemed necessary.

Figure 5 shows users during the experimental evaluation procedure. For data collection, user observation, interviews, and questionnaires were used. The questionnaire used consisted of three parts (part A, B and C), with closed-ended questions. Part A concerned mainly demographic data (gender, age, work status and physical mobility). Questions in Part B and C of the questionnaire were based on existing loneliness [

29], well-being [

30] and usability [

31] questionnaires. A number of questions from the aforementioned questioners were selected so that a customized questionnaire that suits the research questions of the experiments was formulated. The first nine questions (

Table 1) of Part B and C of the questionnaires were identical so that differences in responses before and after the intervention were quantified. In addition to the common questions, Part C of the questionnaire contained questions related to the attractiveness/usability of the application, the immersion levels of the users, and also included questions related to the overall impression of the users towards the application. Participant responses were on a 1-5 Likert scale from “Strongly disagree=1” to “Strongly agree=5” with closed type questions to enable grouping and analysis of results.

At the beginning of the evaluation process, participants completed Part A and Part B of the questionnaire, and afterwards they had the chance to use the VR application for about 3-7 minutes. Upon completing the use of the application, users completed Part C of the questionnaire (

Table 2). Then the researcher conducted an open-ended interview based on the comments they mentioned during the use of the application in order to develop more comments and thoughts to improve the application. The total duration of the interviews ranged from 5 to 20 minutes. For the data analysis, the package SPSS was used. In the analysis, both descriptive and inferential statistics were applied for exploring the differences amongst the groups and utilizing statistical tests, paired sample t-test, and independent samples t-test. Then followed the analysis of the interviews, where some phrases/keywords were grouped to see the opinions of the users quantitatively. At the same time, important reports and comments reported by users have been recorded.

5.3. Quantitative Results

The results of the paired sample t-test before and after the intervention are presented. This test is used because the samples are depended since it has to do with the same persons in different circumstances (before and after the interference). The null hypothesis (H0) is that there is no significant statistical difference regarding the responses of the participants before and after the intervention and the alternative (H1) is that there is a statistically significant difference with regard to the responses of the users before and after the intervention. Based on the results (

Table 3) there is statistically significant difference with a p-value smaller than 0,05 for the pair of questions B5-C5 “I believe there are virtual reality applications that help me not feel alone”. For the remaining pairs of questions, although there is a difference in the mean values, no statistically significant differences were recorded before and after the intervention.

The results of the non-parametric Wilcoxon Sign Rank Test before and after the intervention are presented. This test is used because the samples are paired, and the data are in ordinal scale since it has to do with the same persons in different circumstances (before and after the intervention).

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 show the results of the analysis for each group, and the pairs of questions where statistically significant difference was observed. With reference to the results of the questionnaires, it was observed that in all the participants but also in the results of each group only in question B5/C5 “I believe there are VR applications that help me not feel alone.” There was a significant p value for all groups (

Table 3). We can justify this because people who have never had contact before have come into contact with virtual reality, since it helped them understand what a virtual environment is and what it offers them. It was observed that many people were willing to use the application if they had the VR headset and smartphone equipment. A large percentage were positive about using a VR app, but not for everyday use. As observed in the age group of 70 and over there is a significant p value of .022 for question B1/C1 “Would I be interested in using a virtual reality application in my daily life to socialize with other people” and correspondingly for question B5/C5 the p value is .000. This indicates that older people realized what virtual reality is useful as a means of enhancing socialization. Given that the proposed application is not a collaborative application, it is implied that the users considered the presence of a virtual audience as a step towards socialization. It was observed that people who did not have someone near them in the physical environment were more positive to use the app more often if they had the equipment. For question B6/C6 “I feel healthy” for the age group of 55-69 years there was a significant p value of .035. The specific age group has the ability to socialize with colleagues and family, mobility meaning they have the ability to move for their needs and have more direct contact with technology, meaning they are in better physical condition than the 70 and over group and using virtual reality on a daily basis is not their priority. In question B9/C9 “I am satisfied with everything in my life” there was a significant p value .049 in the Non-Disability Group with the difference in answers decreasing in the second part of the questionnaire. We believe this is justified because after using the application, a reflection was made on the expectations they had set in the first part of the questionnaire, with the result that they recalled memories from their young years and upon completion of the application came to the present day and came into contact with the present day difficulties they may face due to age.

5.4. Qualitative Results

During the interviews/observations participants expressed several interesting views regarding the application. There were participants where recounting their youthful memories evoked feelings of emotion, joy, nostalgia, and sadness. In particular, the oldest participant, who was 100 years old with excellent mental perception and vision, mentioned that such an application would make him forget the daily life of living in the rehabilitation house and felt a thrill to be able to see again photos from his home town. There were also people who stated that they would like to use this app frequently and select different photographs every time they use it. It was also observed that some participants living in rehabilitation houses were reluctant towards virtual reality technology as most of them did not have compatible smartphones and did not want to learn anything new about technology. Overall based on user feedback it seems that users were positive towards the first contact with VR and if they had the equipment they would like to use it again.

For the analysis of the interviews the most frequent keywords/phrases mentioned by the participants were registered (

Table 8).The most frequently mentioned keyword is “They don’t feel lonely in everyday life (26/50 participants)” hence for most participants it was not necessary to use the VR applications as a means of compacting loneness. In particular, most people mentioned that at their current age, they have family close to them (spouses, children, and grandchildren) and prefer to socialize with them instead of using virtual reality. The keyword “Useful for people who feel alone (21/50)” comes in second place implying that although most users believe that it is not necessary for them to you the application, they realize the importance of the application for older people who live alone and don’t have someone to talk to. Several positive keywords related to the application such as “Easy to use” (18/50), “Nice Interface” (17/50), “VR Positive” (17/50), and “immersion” (16/50) was registered indicating the acceptance of the users towards the design and functionality of the application. Also, some users reported that they found it enjoyable that there was a virtual audience because it encouraged them to start the storytelling. Examples of negative keywords registered are “blurred vision” (15/50) which concerns both the quality of the equipment and the reduced vision of the participants due to age, “VR Negative (13/50)” and “Not interested in VR (9/50)” where it was mostly from people who are not interested in using virtual reality since they prefer to socialize with their family members. Finally, the last keyword was “Feeling lonely (8/50)” where elderly people who may live in nursing homes or live alone reported feeling lonely and would like someone to talk to.

6. Discussion

According to the quantitative and qualitative results obtained by exposing elderly users to a memory recalling storytelling VR application, it is observed that elderly users believe such an application can be useful for improving their overall wellbeing. An important factor is that they can use the equipment themselves so that they do not need the support of another person in contrast to the work of Luijkx et al. [

32] where it mentions the involvement of the whole family for the use of a virtual application. Based on the research questions posed the following conclusions are reached:

-Research Question (RQ1): Are elderly people willing to use the virtual reality application?

From both the qualitative and quantitative results, it was observed that the majority of the elder users are willing to use the virtual reality application. This is especially true for the participants’ group of 70-79 + years, who mention that would be interested in using a VR application in their daily lives to socialize with other people. However, a percentage of the users expressed their unwillingness to use the VR application due to their lack of knowledge of new technologies. We believe that if elder people are provided with training towards the use of new technologies, the acceptance of elderly users for VR technology will be increased.

-Research Question (RQ2): Do elderly people believe that the VR application can help to overcome feelings of loneliness?

Elderly believed that the specific application can indeed reduce the feeling of loneliness felt by the elderly. In particular, they mentioned that through the application they forget that they are in the real environment and it motivated them to start the narratives in the virtual audience. We believe that two characteristics of the application contributed to this observation. Firstly, the ability to enter a storytelling experience [

33], and secondly the presence of the virtual audience that motivated further the users to start the storytelling according to the interviews. Since storytelling is among the favorite activities for elderly [

34], storytelling in a VR environment proved to be a feasible alternative when direct contact with a real audience is not feasible.

-Research Question (RQ3): Do elderly people believe that the VR application can help to increase their levels of well-being?

Most users had positive feelings during the use of the application. Overall, even the people who said that they would not like to use the application at this time because they do not think it is necessary either because of their age or because they have people close to them in their family environment, said that it will be useful and enjoyable for people who they feel alone to escape their loneliness.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

The aim of the present research was to study whether elder people believe that the proposed virtual reality application could help the elderly cope with feelings of loneliness and social isolation. Through the use of the application, the factors that influence users on how receptive they are to a new application were also studied. As a general picture, it can be noted that users are positive towards this technology but would like to use it only when they really need it, that is, when they feel lonely and would like to have someone to talk to.

As future plans we will rely on the needs of the users to improve the application. In particular, an important factor is that most users suggested is having personal photos in the application and allowing the user to select the photographs to be displayed. In addition an increased interaction of the virtual audience according to the narrative they receive from the user will be explored. Also, in the future we plan to assess the quality of the storytelling provided by the user using dedicated presentation evaluation techniques[

35]. Within this context users could earn points based on the storytelling quality, so that a game-based rewarding VR experience is offered. Also the prospect of turning the application into on-line collaborative that allows multiple users to discuss photographs and interact with each other, will be explored.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.A. and A.L.; methodology, Z.A. and A.L.; software, Z.A.; validation, Z.A. and A.L.; formal analysis, Z.A. and E.D.; investigation, Z.A.; data curation, Z.A., A.L., and E.D.; writing—original draft, Z.A. and A.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.A. and A.L.; visualization, Z.A.; supervision, A.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Most of the work described in this paper was supported by a Cyprus State Scholarships Foundation PhD Studentship to Zoe Anastasiadou.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present study has undergone an ethics review process and was approved by the National Bioethics Committee (Ref. Number: ΕΕΒΚ ΕΠ 2023.01.167) thereby ensuring that all stages of the research was conducted according to ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bauer, A. C. M., & Andringa, G. (2020, September 9). The Potential of Immersive Virtual Reality for Cognitive Training in Elderly | Gerontology | Karger Publishers. Retrieved January 27, 2024, from Karger Publishers website. 9 September. [CrossRef]

- Van Houwelingen-Snippe, J., Ben Allouch, S., & Van Rompay, T. J. L. (2021). Virtual Reality Representations of Nature to Improve Well-Being among Older Adults: a Rapid Review. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science. [CrossRef]

- Lee, L. N., Kim, M. J., & Hwang, W. J. (2019). Potential of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Technologies to Promote Wellbeing in Older Adults. Applied Sciences, (17), 3556. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M., & Lupton, D. (2021). Pandemic fitness assemblages: The sociomaterialities and affective dimensions of exercising at home during the COVID-19 crisis. Convergence, 27(5), 1222-1237.

- Liu, H., Wang, Z., Mousas, C., & Kao, D. (2020, November). Virtual reality racket sports: Virtual drills for exercise and training. In 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR) (pp. 566-576). IEEE.

- Singh, D. K. A., Rajaratnam, B. S., Palaniswamy, V., Pearson, H., Raman, V. P., & Bong, P. S. (2012). Participating in a virtual reality balance exercise program can reduce risk and fear of falls. Maturitas, (3), 239–243. [CrossRef]

- Oppert, M. L., Ngo, M., Lee, G. A., Billinghurst, M., Banks, S., & Tolson, L. (2023). Older adults’ experiences of social isolation and loneliness: Can virtual touring increase social connectedness? A pilot study. Geriatric Nursing, 270–279.

- Peleg-Adler, R., Lanir, J., & Korman, M. (2018). The effects of aging on the use of handheld augmented reality in a route planning task. Computers in Human Behavior, 52–62. [CrossRef]

- Mostajeran, F., Steinicke, F., Ariza Nunez, O. J., Gatsios, D., & Fotiadis, D. (2020). Augmented Reality for Older Adults: Exploring Acceptability of Virtual Coaches for Home-based Balance Training in an Aging Population. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. [CrossRef]

- Rose, V., Stewart, I., Jenkins, K. G., Tabbaa, L., Ang, C. S., & Matsangidou, M. (2019). Bringing the outside in: The feasibility of virtual reality with people with dementia in an inpatient psychiatric care setting. Dementia, (1), 106–129. [CrossRef]

- Lera, F. J., Rodríguez, V., Rodríguez, C., & Matellán, V. (2013). Augmented Reality in Robotic Assistance for the Elderly. In International Technology Robotics Applications (pp. 3–11). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Skurla, M. D., Rahman, A. T., Salcone, S., Mathias, L., Shah, B., Forester, B. P., & Vahia, I. V. (2021). Virtual reality and mental health in older adults: a systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, (2), 143–155. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z., Lee, J. E., McDonough, D. J., & Albers, C. (2020). Virtual Reality Exercise as a Coping Strategy for Health and Wellness Promotion in Older Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Clinical Medicine, (6), 1986. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P. L., Zimand, E., Hodges, L. F., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2005). Cognitive behavioral therapy for public-speaking anxiety using virtual reality for exposure. Depression and Anxiety, (3), 156–158. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. J., & Park, S. J. (2020). Immersive Experience Model of the Elderly Welfare Centers Supporting Successful Aging. Frontiers in Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X. (2017). Designing VR experience for older adults and determine its impact on their overall well-being. Doctoral Dissertation.

- Ma, J., Zhao, D., Xu, N., & Yang, J. (2023). The effectiveness of immersive virtual reality (VR) based mindfulness training on improvement mental-health in adults: A narrative systematic review. EXPLORE, (3), 310–318. [CrossRef]

- Matsangidou, M., Schiza, E., Hadjiaros, M., Neokleous, K. C., Avraamides, M., Papayianni, E., … Pattichis, C. S. (2020). Dementia: I Am Physically Fading. Can Virtual Reality Help? Physical Training for People with Dementia in Confined Mental Health Units. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (pp. 366–382). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. C., Sit, C. H. P., Tang, T. W., & Tsai, C. L. (2020). Psychological and physiological responses in patients with generalized anxiety disorder: The use of acute exercise and virtual reality environment. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(13), 4855.

- Tammy Lin, J. H., & Wu, D. Y. (2021). Exercising with embodied young avatars: how young vs. older avatars in virtual reality affect perceived exertion and physical activity among male and female elderly individuals. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 693545.

- Anastasiadou, Z., & Lanitis, A. (2022). Development and Evaluation of a Prototype VR Application for the Elderly, that can Help to Prevent Effects Related to Social Isolation. 2022 International Conference on Interactive Media, Smart Systems and Emerging Technologies (IMET). [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadou, Z., & Lanitis, A. (2023). Determining Optimum Audience for Storytelling VR Applications for the Elderly. 36th International Conference on Computer Animation and Social Agents (CASA 2023).

- Ijaz, K., Tran, T. T. M., Kocaballi, A. B., Calvo, R. A., Berkovsky, S., & Ahmadpour, N. (2022). Design considerations for immersive virtual reality applications for older adults: a scoping review. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 6(7), 60.

- Cheiran, J. F. P., Rodrigues, A., & Pimenta, M. S. (2021). Virtual look around: comparing presence, cybersickness and usability for virtual tours across different devices. Journal on Interactive Systems, (1), 191–205. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y., & Wang, Y. (2024, January). Evaluating the Effect of Outfit on Personality Perception in Virtual Characters. In Virtual Worlds (Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 21-39). MDPI.

- Narakeet—Easily Create Voiceovers and Narrated Videos Using Realistic Text to Speech! (2023, February 12). Retrieved January 27, 2024, from Narakeet website: http://www.narakeet.com. 12 February.

- Unity Asset Store. (2023, February 12). Retrieved January 27, 2024, from Unity website: https://assetstore.unity.com/. 12 February.

- Mixamo. (2023, February 12). Retrieved January 27, 2024, from Mixamo website: http://www.mixamo.com. 12 February.

- Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a Measure of Loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, (3), 290–294. [CrossRef]

- Meaning and Happiness.com » Blog Archive » Oxford Happiness Questionnaire. (2008, October 17). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from Meaning and Happiness.com website: http://www.meaningandhappiness.com/oxford-happiness-questionnaire/214/.

- Brooke, J. (1996). SUS: A “Quick and Dirty” Usability Scale. In Usability Evaluation In Industry (pp. 207–212). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Luijkx, K., Peek, S., & Wouters, E. (2015). “Grandma, You Should Do It—It’s Cool” Older Adults and the Role of Family Members in Their Acceptance of Technology. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, (12), 15470–15485. [CrossRef]

- Langellier, K., & Peterson, E. (2011). Storytelling In Daily Life. Temple University Press.

- Scott, K., & DeBrew, J. K. (2009). Helping Older Adults Find Meaning and Purpose Through Storytelling. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, (12), 38–43. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadou, E. A., & Lanitis, A. (2023). A Systematic Approach for Automated Lecture Style Evaluation Using Biometric Features. In Computer Analysis of Images and Patterns (pp. 3–12). Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).