Introduction

Over the past several decades, the study of theory of mind (ToM) has garnered increasing interest from a diverse range of research fields, as evidenced by numerous studies (François & Rossetti, 2020; Fu et al., 2023; Schaafsma et al., 2015), and its theoretical framework has been debated extensively by philosophers, psychologists, and neuroscientists. Moreover, ToM research has recently been applied to computational modeling and artificial intelligence (AI) to better understand and simulate the mental states and behaviors of others (Gurney et al., 2021; Ho et al., 2022; Langley et al., 2022; Ong et al., 2020; Rusch et al., 2020). At the same time, the economics of emotions (EoE) has seen rapid advancement, with the aim of rendering the human mind programmable in tandem with AI progression (Kadokawa, 2023). The EoE model seeks to categorize all human emotions by applying a unified and straightforward structure to the human mind. Thus, just as neuroscience has significantly advanced ToM research through discoveries such as mirror neurons, EoE's mind modeling can contribute to ToM studies in disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, and cognitive science. Specifically, EoE's mind modeling focuses on human recognition and evaluation, with the primary goal of quantitatively defining emotions that arise from these processes. By modeling the mind in this manner, it becomes possible to explain methods for analyzing the mental states of individuals in specific contexts.

Various ToM have been developed to represent mental states such as rationality, modularity, simulation, executive, and theory theory (TT) accounts (Goldman, 2006; Mahy et al., 2014). The study of the mind within the EoE has a strong affinity with simulation theory (ST) because EoE seeks to give answers how people mindread others, which have been the central question of ST (Goldman, 2006).

1 Specifically, the five-steps (5S) model in EoE is characterized by a deductive analysis of the individual mind, based on the premise that individuals share the same recognitions, evaluations, and emotions in a given situation. When we analyze the mental states of others, we simulate their behaviors in relation to ourselves, as if we were in their position. In 5S model, we simulate the mental state of another based on how we would feel, think, and act, and this method of understanding others' mental states is the same as that used in ST. We next briefly review relevant studies in ST.

Simulation Theory

ST seeks to understand another person's mental state by imagining oneself in the same situation and simulating the other person's behavior in response to that imagined situation (Goldman, 2009; Gordon, 1992; Harris, 1992; Shanton & Goldman, 2010). The process of representing and understanding another's mental state in ST is often described as that is what I would do if that were me (Short, 2015) and putting ourselves in their shoes (Luca & Gordon, 2017). ST is relevant to both low-level mindreading, which is based on facial expressions, and high-level mindreading, which involves making plans and devising strategies (Shanton & Goldman, 2010). Enthusiasm for ST grew when the discovery of the "mirror system" by neuroscientists and cognitive scientists seemed to support the concept of ST (Gallese & Goldman, 1996; Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004). Furthermore, subsequent findings in neuroscience have supported the simulation perspective in mindreading (Gallese & Goldman, 1996; Mahy et al., 2014). Additionally, ST has successfully explained the developmental trajectory of ToM reasoning, from early success in false-belief tests, to later understanding of more complex ToM tasks (Carpendale & Lewis, 2004; Schwanenflugel et al., 1996). These findings align with later research showing a relationship between children's ToM and their imaginative abilities (Lillard & Kavanaugh, 2014; Sidera et al., 2021; Taylor & Carlson, 1997). Furthermore, ST has potential applications not only in interpersonal simulation, but also in intrapersonal simulation, such as re-experiencing episodic memories and pre-experiencing imaginations in planned behaviors (Shanton & Goldman, 2010), thus broadening the scope of ST.

ToM conceptually includes ST, but ST has been met with skepticism by numerous scholars. For example, Daniel Dennett suggested that ST inevitably merges with TT, because simulating requires reliance on knowledge, which is organized as a theory during the simulation process (Dennett, 1978). Recognizing patterns by simulating others' minds leads to these patterns being considered theories in mindreading. As more patterns are identified in simulations, they become increasingly theorized, ultimately leading to ST being supplanted by TT (Jackson, 1999). Furthermore, Heal (1994) contended that simulators inherently use an implicit theory; when we use our own emotions to predict someone else's, we are effectively employing a tacit theory of emotions. Nichols and Stich (2003) even proposed that the term "simulation" be discarded, arguing that ST lacks the specificity to stand out as an independent theory distinct from others. Additionally, Saxe (2005) questioned the inability of ST to account for why people make consistent mistakes when predicting others' mental states. Goldman and Sebanz (2005) countered with the “incorrect input argument,” stating that systematic errors in mindreading are not due to a fundamental problem with the simulation mechanism, but rather with the quality of the data fed into the simulation. As a result, hybrid theories that partially integrate TT, rather than relying solely on ST, have become the standard (Goldman & Sebanz, 2005; Nichols & Stich, 2003; Perner, 1996).

The debate and criticism surrounding ST often arise because ST or hybrid theory is inherently abstract, and does not offer a clear method for simulating the mental states of others. Therefore, it is essential for the development of ST to present a model of the mind that provides a specific and general framework to explain how individuals simulate the mental states of others. The goal of this study is to introduce a model that advances ST, drawing from the 5S model in EoE. This 5S model contributes to the study of ToM from three distinct perspectives.

Three Merits of Introducing the 5S Model

First, ST and hybrid theories present only simplified concepts, and do not explain how individuals actually simulate the mental states of others (Gallese & Goldman, 1996; Goldman, 2006; Saxe, 2005). The critical aspect is to explain the decision-making or factual-reasoning mechanisms that mediate between the input of beliefs and desires and the output of specific behaviors. Although these mechanisms are the most crucial part of the ToM, they have remained unexplored, because they are treated as a black box. Without a clear and specific framework for the decision-making mechanism, simulation theorists will not be able to fully address the collapse argument (Dennett, 1978) or the systematic error argument (Saxe, 2005). Therefore, the first advantage of incorporating the EoE model into the study of ToM is to provide a specific method for simulating others' minds and to assist in removing the ambiguities that have led to various debates and criticisms of ST.

Second, even though the hybrid theory has become the mainstream within ST (Perner, 1996), we cannot ascertain the necessity of tacit theory in mindreading, or the extent of its necessity to supplement the shortcomings of ST, unless we are certain about the capacity of simulation-based mindreading to understand others' mental states without the aid of tacit theory. Therefore, to confirm the need for tacit theory in mindreading, it is crucial to identify the limitations of ST, which can be employed to explain others' mental states, by explaining specific and general methods of simulation. Once the boundaries of simulation are identified, they can be used to identify the limits of ST, and tacit theory can be used to explain the mental state beyond these boundaries. Thus, the second advantage is that the 5S model could assist in defining the limitations of ST.

Third, and most importantly, the structure of the 5S model potentially tied to emotions appeared in the process of behavior. If there is a formal mental model, it has to define various types of emotions that emerge during the simulation process, which are based on individual’s desires and beliefs. However, the currently simulation model is not developed enough to provide the reason why various emotions arise in individual’s consciousness in the process of behavior, which sometimes positively encourage behaviors or hampers them negatively. In other words, although the ToM should be a theory that not only aids in understanding others' mental states, but also assists in empathizing with the emotions that surface in their consciousness, none of the current ST or hybrid theories provide a clear framework to capture and define others' emotions. More specifically, when attempting to endow AI with a mind, the ToM must be clear and logical so that it can be programmed into a computer. When programming the mind, it is necessary to quantitatively define desires, beliefs, and emotions. The only existing model that quantitatively defines the magnitude of desires, beliefs, and emotions is the EoE model. Therefore, introducing the 5S model is essential for the further development of ToM.

Hence, in the remainder of this article, we introduce the basic 5S model and argue that the 5S model can contribute to the development of ToM. Specifically, the 5S model contributes to the concise representation of decision-making or factual reasoning mechanisms that have been a black box in ST. In other words, in conventional ST, when elements such as desires and beliefs are input, individual intentions and actions are assumed to be output, but the crucial process from input to output has been ambiguous. In contrast, the 5S model succeeded in concisely expressing the decision-making mechanism. In other words, in the 5S model, perceiving an incentive triggers the expression of a desire in an individual’s consciousness, leading to the expression of various related desires. When the relationships between the desires expressed in consciousness are sorted out, the magnitude of rewards and costs for behavior, as well as the mental state of others, become clear, which allows us to predict the behavior of others.

In the next section, we will first define desire satisfaction as the goal of an individual's behavior, and then define the emotion of satisfaction that is expressed when a desire is satisfied. Next, in order to predict the behavior of individuals and understand their mental states, we will define the relationships among the desires that constitute their recognitions. In other words, when individuals try to increase their feelings of satisfaction, they do not impulsively satisfy the desires that appear in their consciousness, but instead, they preferentially try to satisfy the desires that contribute to increasing their feelings of satisfaction. When the priority desires to be satisfied are determined, it becomes apparent which desires must be satisfied and which must not be, thereby establishing the hierarchy of desires. Finally, based on the recognition of the relationship between desires, when we distinguish between desires that constitute rewards and costs, we can determine the optimal behavior for individuals and clarify the underlying mental states supporting that behavior.

Simulation of the Five-Steps Model

First, following the standard view of desire-satisfaction theory (McDaniel & Bradley, 2008; Schueler, 1995), it is assumed that the objective of an individual's behavior is to fulfill the intensity of the impulse that fuels the desire

2. All individual behavior is explained in terms of fulfilling this impulse intensity as it appears in consciousness. In EoE, the emotion expressed when the impulse intensity is fulfilled is termed satisfaction, while the emotion expressed when the impulse intensity cannot be fulfilled is termed dissatisfaction. Therefore, the goal of an individual's behavior in EoE is to maximize the consequential emotion of satisfaction and minimize the consequential emotion of dissatisfaction by fulfilling the desire to the greatest extent possible.

In the meantime, when individuals attempt to satisfy impulse intensity as much as possible, they distinguish between desirable and undesirable desires out of desires present in consciousness. The judgement of the desirability here is made based on its contribution to the satisfaction of impulses. When it is not possible to satisfy all impulses, we will necessarily choose the most important desire supported by the strongest impulse, since the satisfaction of impulses is always the objective of individuals. Then, desirable desires arise at that time as desires aiming at satisfying the conditions for the fulfilment of the most important desire, and undesirable desires are distinguished as disturbing desires that prevent the most important desire from being satisfied. By distinguishing the qualitative difference of desires, the recognition of behavior will be created, and it will become possible to accurately evaluate behaviors. Therefore, in this section, we will introduce the five steps to evaluate behaviors in decision-making.

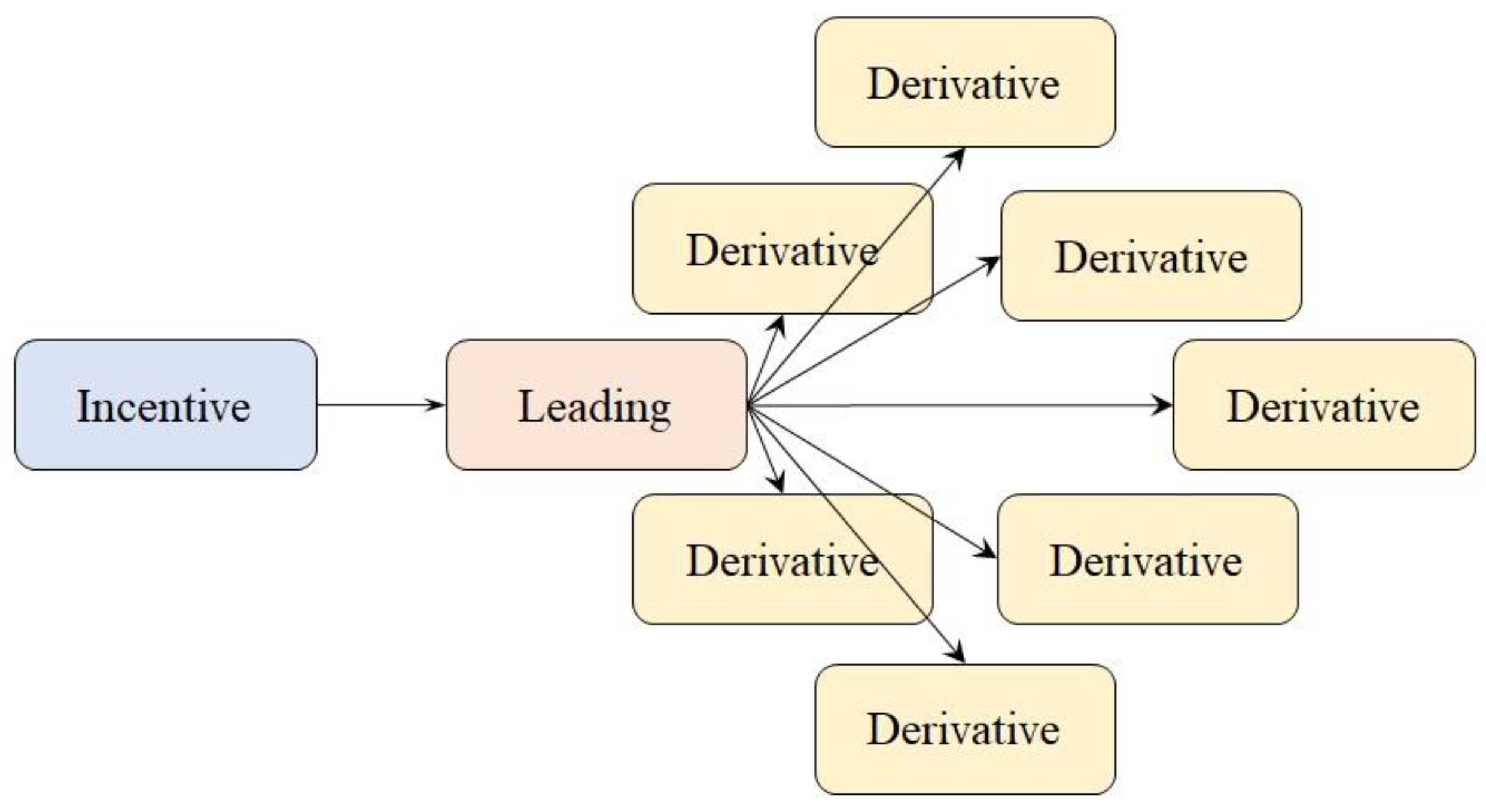

Step 1: Derivation of Desires Relevant to the Situation

The first step is to comprehend all desires relevant to the situation. The purpose of EoE is to model the mental and behavioral processes that occur from the emergence of a desire in consciousness to its fulfillment or non-fulfillment. The factor that initially triggers a desire in consciousness is referred to as an incentive. The desire that is induced by this incentive is known as the leading desire. This desire includes all sensations that can be expressed in the form “I want to…”. In EoE, terms such as want, need, urge, appetite, craving, and so on, as long as they can be expressed in the form “I want to…,” are represented as a desire Conversely, when an action is taken to satisfy a leading desire, desires that cannot be satisfied by the action and those that can be simultaneously satisfied emerge in our consciousness. Additionally, desires that must be fulfilled in preparation for the action also appear in consciousness. These desires that arise in consciousness when we attempt to act to satisfy the leading desire are termed derivative desires. The EoE's model of the mind thus begins by deriving these derivative desires from the leading desire.

Figure 1.

the expansion of consciousness from the leading desire to the derivative desires.

Figure 1.

the expansion of consciousness from the leading desire to the derivative desires.

For instance, using the ice cream task from Perner and Wimmer (1985) as a reference, we can establish the following sequence of leading and derivative desires. First, when Mary observes an ice cream truck parked in the park, the truck serves as a stimulus, sparking an urge to consume ice cream in Mary's mind. This urge subsequently evolves into a desire to eat the ice cream, and the expressed desire at that moment becomes Mary's leading desire. At this point, when Mary attempts to fulfill her desire to eat ice cream, two types of desires emerge in her consciousness: those that can be satisfied by the action of eating ice cream and those that cannot. For example, if Mary desires to engage in a conversation with John while eating ice cream, this desire can be fulfilled simultaneously with her action of eating ice cream. Conversely, if Mary has a desire to save money for other purchases, or a desire to decrease her calorie intake and lose weight, these desires cannot be satisfied by the action of eating ice cream. When these two types of desires, those that can be satisfied by the action of eating ice cream and those that cannot, emerge in Mary's consciousness, they are recognized as derivative desires. The process of generating derivative desires from leading desires is referred to as the expansion of consciousness. In the EoE model, desires derived from the expansion of consciousness are differentiated based on their interrelationships. We now introduce the three types of relationships between desires to distinguish them

3.

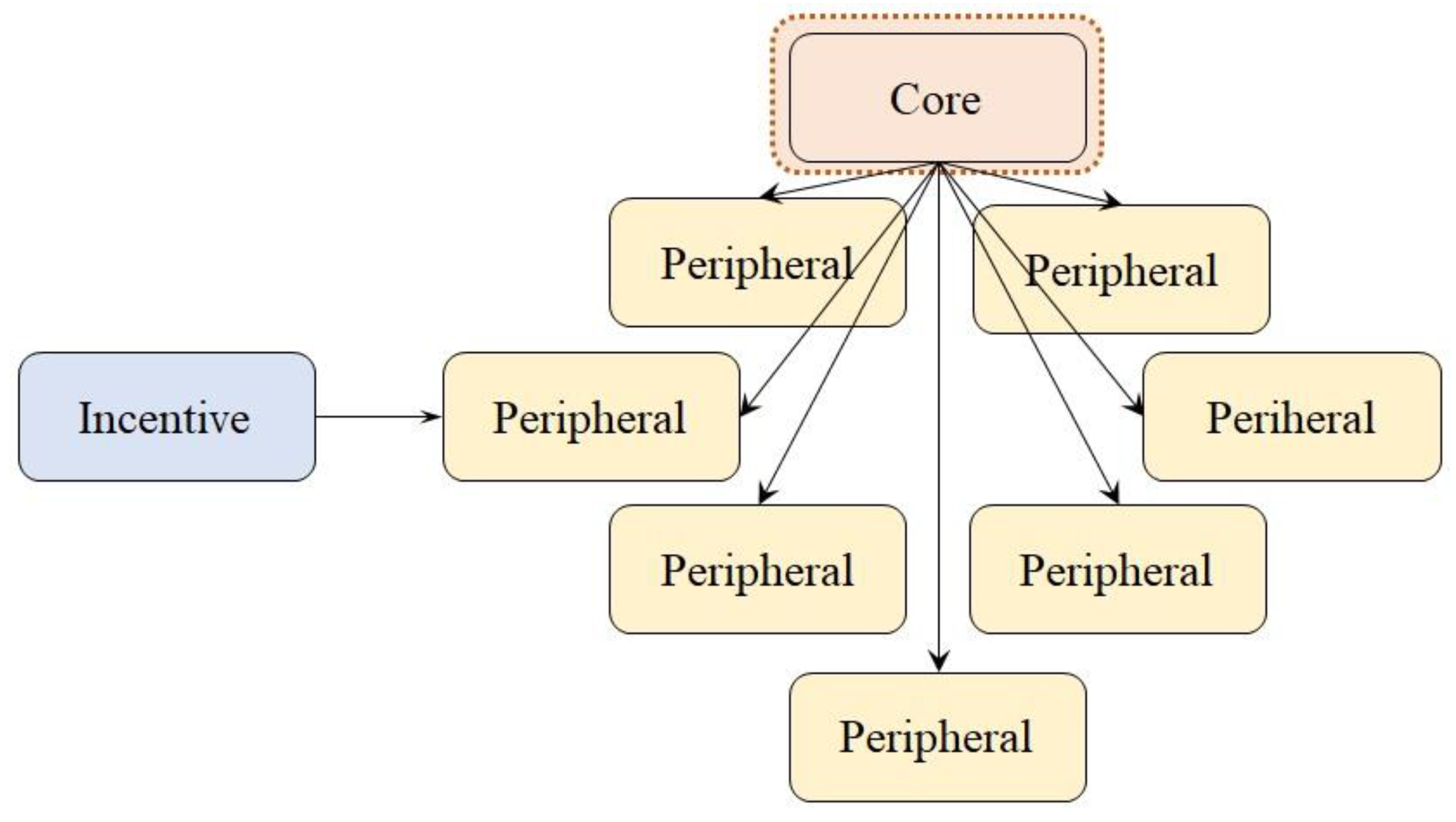

Step 2: Choice of the Goal to the Situation

The second step is to create a recognition of the order relationship between desire. It is feasible to identify the desires among the leading and derivative desires that significantly contribute to enhancing the resulting emotion of satisfaction. The desire that contributes the most to this increase in satisfaction is thus termed the core desire. When defining the core desire for the situation in which the individual finds themselves, the goal of the person's behavior will be to fulfill this core desire, and the behavior will subsequently be structured around this core desire. When only one core desire is selected from the leading and derivative desires, the remaining desires are labeled as peripheral desires. These peripheral desires will then be categorized into conditional desires, coinciding desires, and conflicting desires, which are discussed later.

Figure 2.

the concentration of consciousness from the peripheral desires to the core desire and the recognition of order relationship.

Figure 2.

the concentration of consciousness from the peripheral desires to the core desire and the recognition of order relationship.

Core desires can be categorized into two types. The first type is influenced by the intensity of the impulse. This means that an individual's behavior is aimed at enhancing the resulting emotion of satisfaction by fulfilling the impulse's intensity to the greatest extent possible. When the impulse supporting a specific desire is at its peak, it becomes feasible to enhance the resulting emotion of satisfaction by fulfilling that desire. Consequently, the desire with the strongest impulse will contribute significantly to the enhancement of the resulting emotion of satisfaction, and this desire will then become the core desire. In this context, the core desire determined based on the impulse's intensity is referred to as the impulse-type core desire.

Another core desire emerges when conditions exist that can fulfill a specific desire, and efforts are made to meet these conditions to enhance the level of satisfaction. In essence, when the fulfillment of one desire creates the possibility of meeting the requirements for satisfying multiple desires, that desire may take precedence. Furthermore, when fulfilling a desire allows for the satisfaction of various impulses, it indirectly contributes to the expansion of satisfaction. Even if the intensity of the impulses supporting the desire is not particularly strong, if satisfying that desire leads to an increase in the resulting emotion of satisfaction, then that desire is identified as a primary motivation that should be prioritized, and is more desirable than other desires. Such primary motivations, determined based on their desirability, are thus referred to as chord-type core desires.

Consider the following example of an impulse-based core desire. First, imagine that Mary has four desires present in her consciousness: the desire to eat ice cream, the desire to converse with John, the desire to purchase something she wants, and the desire to start a diet. If the impulse supporting the desire for ice cream is the strongest, this desire is selected to be fulfilled from the list of desires. Consequently, the desire for ice cream becomes the impulse-based core desire, while the other three desires are relegated to peripheral desires. In terms of a chord-based core desire, dieting could also become a priority for Mary if it allows her to wear clothes she previously could not, or to gain John's affection. Even if the impulses supporting the desire to diet are not particularly strong, the desire to diet may become a core desire if it enables her to satisfy a variety of desires. Thus, the desire to diet becomes the core desire to meet the conditions for satisfying other desires, and it becomes a chord-based core desire.

The distinction between core and peripheral desires is known as the recognition of the order relationship

4. This cognitive process determines which desire should be prioritized as the basis for decision-making and actions aimed at enhancing emotional satisfaction. When individuals have differing perceptions of this hierarchy, it prompts a discussion about which desires most effectively contribute to increased emotional satisfaction and whether the prioritization is accurate. When the recognition of the order relationship correctly identifies the core desire that should be prioritized based on an individual's specific circumstances, that person's decisions and actions are guided by this core desire. This deliberate focus on the core desire for guiding decisions and actions is referred to as the concentration of consciousness. In turn, when there is a concentration of consciousness on the core desire, a secondary desire may arise to fulfill the necessary conditions to satisfy that core desire. Next, we discuss such secondary desires.

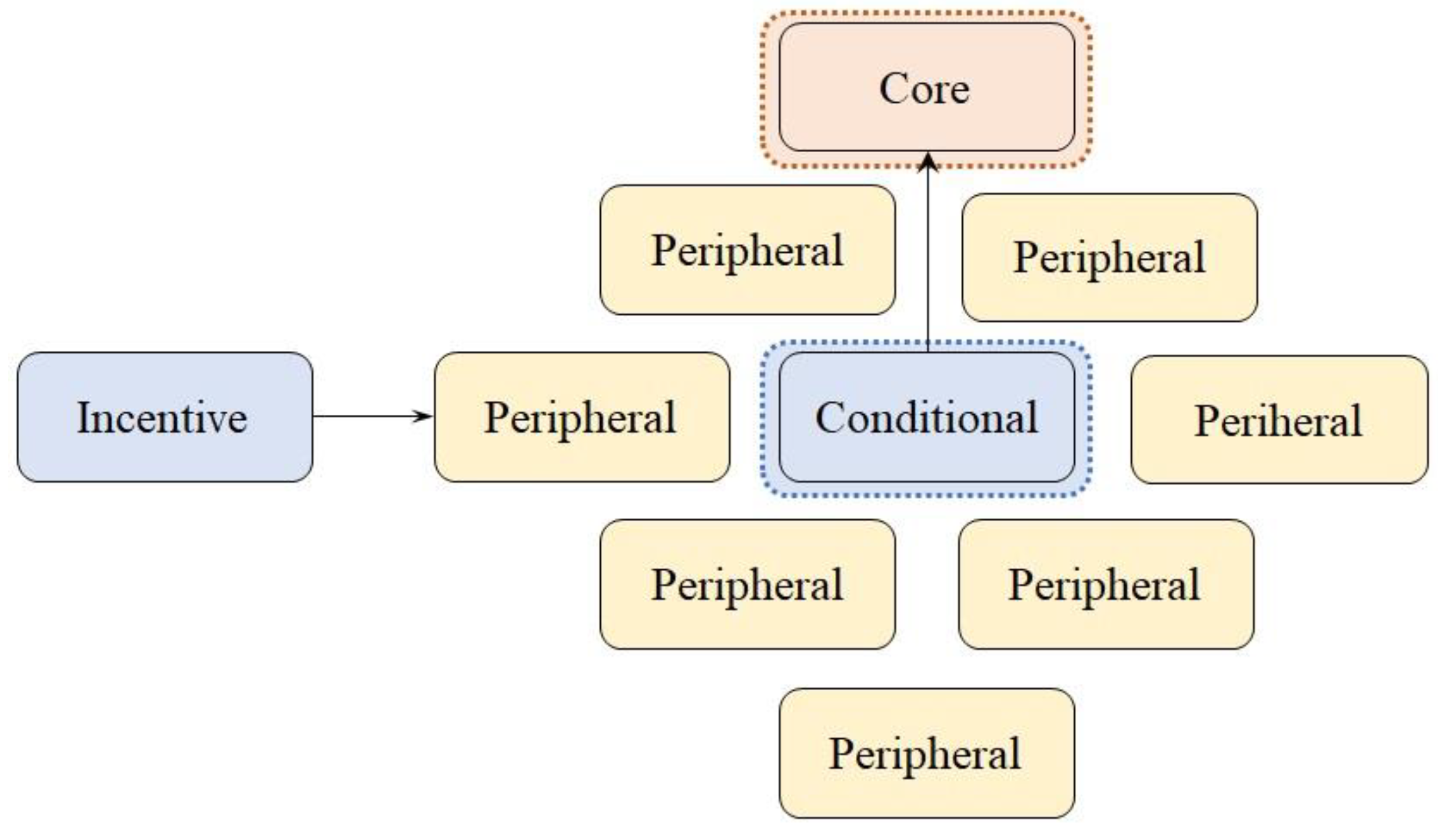

Step 3: Analysis of the Condition to Achieve the Goal

The third step is to create a recognition of the condition relationship between desire. When an individual seeks to fulfill a core desire, they may encounter specific conditions that must be met to achieve this goal. The motivation to meet these conditions induce a desire to satisfy the prerequisites for the fulfillment of the core desire. So, we shall distinguish the desire as a conditional desire from the peripheral desires

5. The intrinsic impulse behind the conditional desires is relatively weak. However, the fulfillment of the conditional desires is essential, because the core desire cannot be satisfied without it. In the process of trying to satisfy a conditional desire, one may exert effort beyond the weak impulse that typically characterizes it. The conditional desires are articulated through the phrase "I want to…," which, although indicative of a weaker impulse, is crucial for satisfying the stronger core desire. Thus, by fulfilling the conditional desires, one indirectly enhances overall satisfaction by enabling the fulfillment of the core desire

6. The phrase "I want to…" signifies an intention that is vital for achieving the underlying core motivation, despite its weaker impulse (see

Figure 3).

If we represent the core desire as C and the conditional desire as N, then the core desire represents an individual's primary goal or purpose, while the conditional desire is a means or method to achieve that core goal. The relationship between these desires can be articulated through motivational statements: one might say, "I want to do N in order to do C," or "I want to do C by doing N." In these statements, "C" is the purpose, and "N" is the instrumental action taken to reach "C." The conditional desire (N) is characterized by a weaker impulse, because it is not an end in itself, but a step toward satisfying the core desire (C). However, the fulfillment of the core desire is contingent upon the satisfaction of the conditional desire, which is why the conditional desire can also be expressed with the phrase "I want to…" This expression indicates a desire to fulfill the core desire, and thus the intensity of the impulse behind the core desire is indirectly manifested in the "I want to…" articulation of the conditional desire.

This distinction of the conditional desire is called the recognition of a condition relationship. The concept of a condition relationship refers to an individual's understanding of the necessary actions or conditions required to fulfill a fundamental core desire. When individuals hold different perceptions or beliefs about how to satisfy such a core desire, these variances can lead to discussions or disputes. The focus of these debates is on the validity or accuracy of each person's recognition of a condition relationship, essentially questioning whose understanding of the necessary conditions for satisfying the core desire is correct.

In this section, we have outlined the core desires that demand immediate satisfaction and the conditional desires that facilitate the fulfillment of these core desires. However, when attempting to satisfy a core desire through a conditional desire, there may be desires that impede this process and others that promote it. We will next analyze the desires that either conflict with or align with the core and conditional desires.

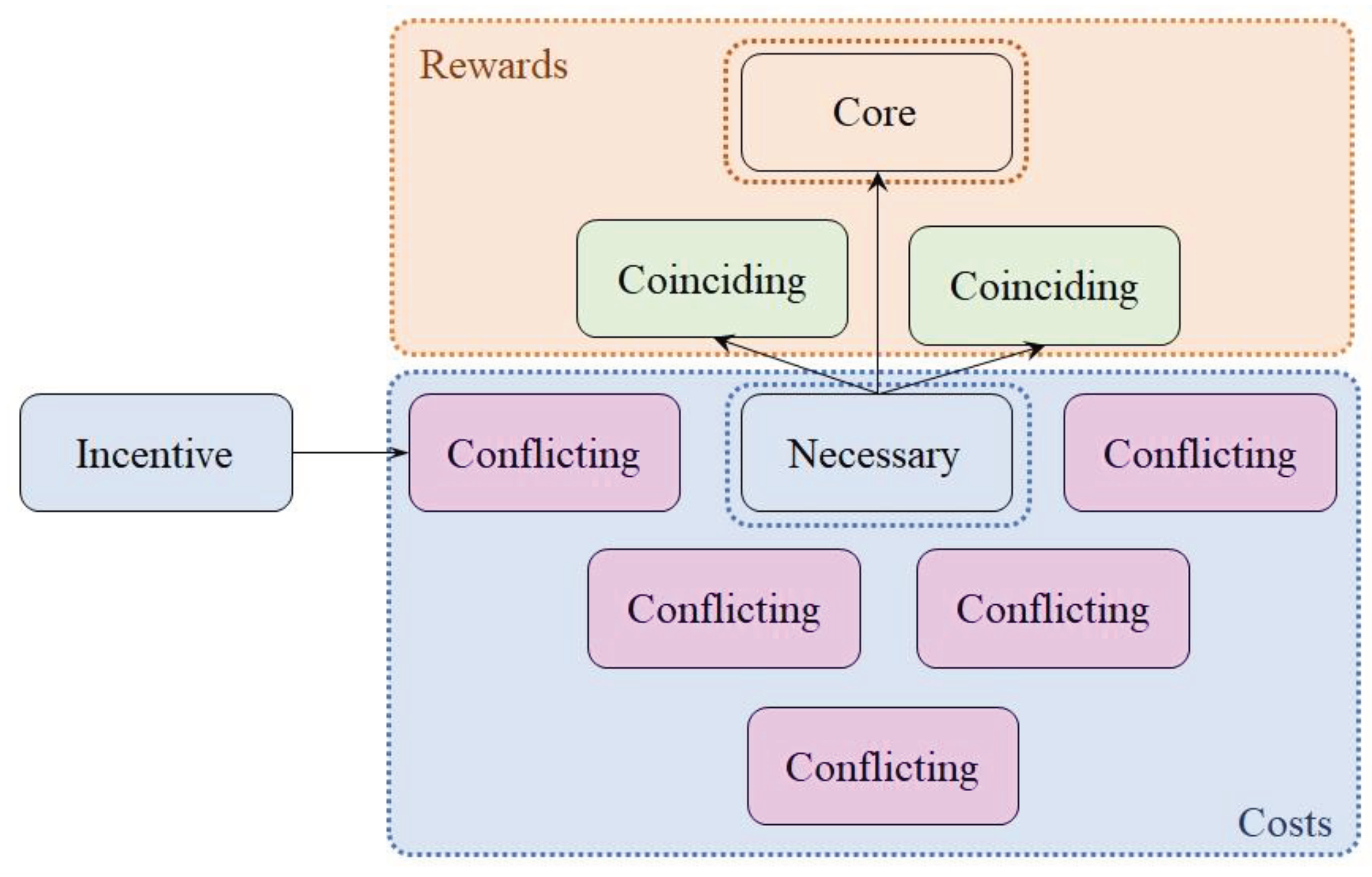

Step 4: Analysis of the Conflicting and Coinciding Desires

The fourth step is to create a recognition of the dependency relationship between desire. When attempting to fulfill a conditional desire to meet a core desire, an individual may encounter a conflicting desire that cannot be satisfied simultaneously with the conditional desire. This conflicting desire becomes an obstacle to fulfilling the core desire if it is pursued with an intensity that rivals or surpasses the conditional desire. The impulses fueling the conflicting desire can become so strong that they override the impulses to satisfy the conditional desire. However, indulging in the conflicting desire ultimately prevents the fulfillment of the core desire, leading to its recognition as a desire that should not be pursued. Despite the powerful impulse behind the conflicting desire, it must be suppressed to allow for the satisfaction of the conditional desire, which in turn satisfies the core desire. The conflicting desire is characterized by a strong "I want to..." impulse that, if acted upon, disrupts the fulfillment of more essential psychological needs. Conversely, not fulfilling the conflicting desire, despite its compelling nature, can lead to an increased sense of satisfaction, because it allows for the necessary and core desires to be met.

Despite the strength of the impulse supporting a conflicting desire, when one refrains from satisfying it, the desire to "still want to..." emerges. Specifically, if the impulse behind the conflicting desire is strong, the initial desire of "I want to..." is quickly fulfilled as soon as one begins to indulge in the conflicting desire behavior. However, if the impulse is not entirely satisfied and one ceases the conflicting desire behavior to fulfill a more pressing desire, the residual desire of "still want to..." persists. For instance, the urge to drink water when extremely thirsty is satisfied upon drinking. Yet, if the impulse remains partially unfulfilled and the individual attempts to stop drinking, the desire to "still want to drink water" continues. Consequently, when an individual consciously chooses not to satisfy a conflicting desire despite the persistent desire, they must exert control over the impulse to maintain the cessation of the conflicting desire behavior.

When fulfilling a conditional desire to satisfy a core desire, a coinciding desire may emerge. This coinciding desire, which arises from satisfying the conditional desire, is distinct from the conditional desire that must be met and from a conflicting desire that should not be met. The coinciding desire is characterized by an intensity of impulse that encourages the fulfillment of the necessary desire. As long as the coinciding desire is accompanied by this intensity, satisfying it can help satisfying the core desire. However, the satisfaction of the coinciding desire is independent of the fulfillment of the core desire and is neither inherently necessary nor inherently counterproductive. Thus, the impulses supporting the coinciding desire are considered neutral. Furthermore, if satisfying the coinciding desire enhances the consequential emotion of satisfaction, it should be satisfied to the extent that the impulse is fully met, with no benefit in exceeding or not meeting this level of fulfillment (see

Figure 4).

For instance, Mary's wish to converse and play with John at the park becomes a coinciding desire when her conditional desire to visit the park allows her to satisfy these desires. In this case, the coinciding desire, accompanied by the intensity of its impulse, encourages the over-fulfillment of the conditional desire. Moreover, when Mary decides to visit the park both to engage with John and to purchase ice cream, the coinciding desire not only motivates her to fulfill the conditional desire, but also the core desire to enjoy ice cream. Conversely, if Mary's principal reason for visiting the park is to eat ice cream, the decision to play there is not her main motivation.

This distinction of the conditional desire is called the recognition of a condition relationship. The concept of recognition of dependency relationship refers to an individual's understanding that fulfilling their core and conditional desires can activate secondary motivations and inhibit opposing motivations. This recognition includes awareness of the potential benefits and drawbacks of the strategies used to achieve one's goals. When individuals have differing perceptions of these dependency relationships, the perceived pros and cons linked to a particular behavior become a topic of debate. Consequently, discussions ensue regarding the accuracy of each person's recognition of these dependency relationships.

Step 5: Evaluation of Cost and Reward of the Behavior

The fifth step is to evaluate behavior based on the three recognitions introduce above. The EoE theory posits that an individual's behavior is driven primarily by the goal to amplify feelings of satisfaction and diminish feelings of dissatisfaction. This is achieved by satisfying the intensity of the impulse that underlies a specific desire to the greatest extent possible. The reward or satisfaction derived from a behavior is directly proportional to the strength of the impulse that can be satisfied. In other words, the more intense the satisfied impulse, the greater the resulting emotion of satisfaction. Among the various desires, it is the core desire and coinciding desires that have the capacity to fully satisfy the intensity of the impulse. Consequently, the reward an individual can obtain from a behavior is determined by the intensity of the impulses that support the core desire and coinciding desires, which can be fully satisfied by that behavior.

Conversely, the intensity of an unsatisfied impulse defines the cost associated with a particular behavior. Initially, an individual will strive to meet the conditions for fulfilling a conditional desire, even when the initial desire or impulse (“I want to…”) is no longer present, leading to over-fulfillment of this desire. Subsequently, even after the intensity of the initial impulse is fully satisfied, a new desire or impulse (“I don't want to … anymore”) emerges from the attempt to over-fulfill the conditional desire. When this new impulse cannot be satisfied, it results in a feeling of dissatisfaction. Therefore, the intensity of the unsatisfied impulse (“I don't want to … anymore”) determines the cost of over-fulfilling the conditional desire. In other words, the greater the intensity of the unsatisfied impulse, the higher the psychological cost of over-fulfilling the desire.

Even when a conflicting desire is not fully suppressed, the intensity of the associated impulse remains unsatisfied. This means that an individual attempts to fulfill a conditional desire by resisting the conflicting desire, despite the persistent desire expressed as “I still want to…” This desire becomes evident when the impulse supporting the conflicting desire is not fully satisfied, but the individual strives to resist the conflicting desire. Consequently, when the conflicting desire is not fully suppressed, the intensity of the “I still want to…” impulse remains unsatisfied, leading to feelings of dissatisfaction. The intensity of this unsatisfied impulse then determines the magnitude of the psychological cost associated with the under-suppression of the conflicting desire. Therefore, the cost of a particular behavior, determined by the unsatisfied impulse, depends on the balance between the strength of the conditional desire that needs to be over-fulfilled and the strength of the conflicting desire that needs to be under-fulfilled.

The behavior of individuals can be understood through a model that includes both vertical and horizontal dimensions. The vertical dimension refers to the complete satisfaction of an individual's core and coinciding desires, which is perceived as a reward for their behavior. On the other hand, the horizontal dimension involves the over-fulfillment of conditional desires, essential for survival and wellbeing, and the under-fulfillment of conflicting desires, which individuals strive to avoid. This over-fulfillment and under-fulfillment are seen as the costs associated with behavior. In this model, individuals aim to maximize their rewards, achieved through the complete fulfillment of core and coinciding desires, and minimize their costs, incurred through the over-fulfillment of conditional desires and under-fulfillment of conflicting desires.

The emotions expressed when predicting the outcome of an action can be defined by considering the perceived benefits of fully satisfying the core and coinciding desires, and the perceived drawbacks of over-satisfying the conditional desire and under-satisfying the conflicting desires. First, the acquisition of rewards is fraught with uncertainty. This means that even if the conditional desires are more than satisfied and the conflicting desires are less than satisfied, it remains uncertain whether the core desire and the coinciding desires can be fully satisfied. Consequently, an emotion of dissatisfaction emerges when the core desire and coinciding desires remain unfulfilled, despite efforts to satisfy the conditional desires and avoid the conflicting desires.

John is able to discern Mary's mental state, recognizing that her intention to consume ice cream is a conscious craving. This is evident from her action of returning home to retrieve money specifically for purchasing ice cream. John also understands that Mary's primary motivation is her desire to eat ice cream. Moreover, he realizes that her intention to go back to the park is driven by her belief that the ice cream vendor is there, which is a necessary component of her consciousness to achieve her goal. However, this belief is based on incorrect information, because the ice cream vendor is actually at the church, not the park. John is aware that Mary's actions are being directed by a false belief. Upon discovering that Mary is unaware of the ice cream vendor's true location, John predicts that she will mistakenly head to the park in pursuit of ice cream.

Thus far, we have identified desires using three types of relationships: order, condition, and dependency. Desires are then classified as either desirable or undesirable, depending on whether they enhance the consequential emotion of satisfaction. The EoE framework defines emotions by the strength of the impulse driving the desire and the desirability of acting on that impulse. Specifically, the desirability of the impulse is assessed when deciding whether to act on it. This decision differentiates impulses qualitatively, and these qualitative differences distinguish one emotion from another. Moreover, the choice to fulfill a desire is influenced by recognitions and evaluations. Thus, within the EoE, emotions are interconnected through these recognitions and evaluations, which also form the basis for analyzing individuals' mental states. Next, we introduce motivational emotions, which are characterized by both the quantitative intensity of the impulse and its qualitative desirability.

Understanding the Mental State

The 5S model has been introduced in this paper so far, but how can we understand the mental state of others through the five steps introduced so far? In order to understand the mental state of others, we should focus on the following three points. First, it is the feeling of enjoyment that appears when we are able to satisfy our desire impulses. Second, it will be a feeling of suffering that appears when we control the desire impulse. Third, it is an emotion that appears when the magnitude of uncertainty and difficulty associated with an action changes. In this section, we will summarize the three points to focus on when trying to understand the psychological states of others.

Emotions for Rewards and Costs

The above results predict that individuals will engage in more rewarding behaviors and clarify the process by which the output of behavior is derived from the input of leading desires arising from incentives, which has been a black box in ST. First, the enjoyment of satisfying the impulses that support the desire will be manifested when the goal can be achieved by satisfying the conditions, and it is possible to understand the individual’s mental state in this process. In other words, it is possible to understand the evolving emotion of enjoyment that arise while trying to satisfy the core desire and coinciding desires in the individual's consciousness.

Simultaneously, it is possible to grasp the progressive emotions of suffering that emerge during the over-fulfillment of conditional desires and the under-fulfillment of conflicting desires. It is also possible to understand the motivational emotions that appear when individuals try to over-fulfill the conditional desires and under-fulfill the conflicting desires. Individuals will also be able to understand that feelings of fear and determination are expressed when uncertainty about the ability to satisfy the core desire and the coinciding desires changes, and feelings of depression and patience are expressed when the difficulty caused by over-fulfillment of the conditional desire and under-fulfillment of the conflicting desires changes. Thus, the EoE model allows us to predict individual behavior based on the recognition of the relationship between desires, and to analyze mental states based on the vertical and horizontal structures. The EoE model is able to succinctly express the decision-making mechanism, which has been ambiguous in ST.

Emotions to Achieve Goals

Next, based on these three recognitions, it is possible to differentiate between desires that should be satisfied and those that should not be satisfied to enhance the consequential emotion of satisfaction. The following three distinctions can be made. First, when the core desire is identified by the order relationship, it is recognized as a priority desire for fulfillment. Second, when a conditional desire is identified by a condition relationship, it is recognized as a desire that must be satisfied to meet the conditions for fulfilling the core desire. Third, when conflicting desires are identified by dependency relationships, they are recognized as desires that should not be satisfied. Among these desires, the conditional desire and conflicting desire are important. This is because, to increase the consequential emotion of satisfaction, it is necessary to more than satisfy the conditional desire, and less than satisfy the conflicting desire. To achieve this, one must control the intensity of impulses.

A conditional desire is identified as a compelling inclination that serves to satisfy a core desire. Owing to its desirability, there is a tendency to overindulge in this desire. For instance, if Mary has a conditional desire to go to the park, over-fulfilling this desire might lead to the emergence of a contrary desire, such as "I don't want to walk to the park anymore." To maintain balance and prevent satisfying such contrary desire, it is important to regulate the strength of this new, opposing impulse. Conversely, conflicting desires are characterized as unwanted inclinations that, despite being counterproductive to a core desire, still arise. These conflicting desires are typically under-fulfilled, owing to their undesirability. For example, if Mary's core desire is to be active and go to the park, but she experiences a conflicting desire such as "I still want to rest at home," this conflicting desire would be under-fulfilled to align with the satisfaction of the core desire. Again, managing the intensity of the impulse associated with the conflicting desire is crucial to ensure it does not overpower the conditional desire

7.

The EoE model defines motivational emotions based on the intensity of impulses that are perceived as either desirable or undesirable. A conditional desire is a desire that must be satisfied to fulfill the core desire, and it is considered desirable if its fulfillment contributes to greater satisfaction. Even if the impulse behind a conditional desire is weak, it is deemed desirable if satisfying the desire is believed to enhance satisfaction. The intensity of the impulse, coupled with a judgment about its desirability, is termed a motivational emotion. Motivational emotions are categorized into those that are desirable and those that are not. However, emotions that underpin conditional desires are inherently associated with desirability because they are thought to lead to an increase in the consequential emotion of satisfaction. The desirability of a motivational emotion is thus always evaluated based on its potential to augment this feeling of satisfaction. The EoE model further defines motivational emotions that strengthen conditional desires by their desirability, such as passion, improvement, diligence, honesty, contribution, goodwill, respect, humility, innocence, fascination, struggle, and encouragement. These emotions are considered positive because they are aligned with the individual's assessment that fulfilling the conditional desire will result in greater satisfaction.

Conversely, conflicting desires act as barriers to the satisfaction of a core desire. In essence, if an conflicting desire is satisfied, the core desire cannot be, thereby preventing an increase in the resulting emotion of satisfaction. Even if the impulse supporting the conflicting desire is strong, it is deemed undesirable if the conflicting desire is judged not to be satisfied. When the strength of this impulse is paired with a judgement of its undesirability, it becomes a motivational emotion. The EoE model defines these motivational emotions that support the conflicting desire in terms of their desirability, with examples such as negligence, depravity, indolence, insincerity, fatigue, malice, arrogance, loss, indifference, retirement, and abandonment. In summary, a motivational emotion is the intensity of the impulse, accompanied by a judgement about whether it should or should not be satisfied, with the ultimate goal of enhancing the consequential emotion of satisfaction.

The emotions discussed in this paper include motivational emotions, which are triggered by personal recognition, and anticipatory emotions, which arise when an individual contemplates the potential outcomes of their actions. Motivational emotions are a result of an individual's self-awareness or self-perception, while anticipatory emotions are based on personal evaluation. This evaluation involves assessing the potential rewards and costs associated with a particular behavior or response to a situation. The rewards and costs refer to the perceived benefits and drawbacks, respectively, that could result from the action. Next, we further analyze the emotions that are elicited when individuals evaluate the potential rewards and costs of their actions.

Emotions to Cope with Uncertainty and Difficulty

Finaly, the emotions expressed when predicting the outcome of an action can be defined by considering the perceived benefits of fully satisfying the core and coinciding desires, and the perceived drawbacks of over-satisfying the conditional desire and under-satisfying the conflicting desires. First, the acquisition of rewards is fraught with uncertainty. This means that even if the conditional desires are more than satisfied and the conflicting desires are less than satisfied, it remains uncertain whether the core desire and the coinciding desires can be fully satisfied. Consequently, an emotion of dissatisfaction emerges when the core desire and coinciding desires remain unfulfilled, despite efforts to satisfy the conditional desires and avoid the conflicting desires.

When individuals strive to evade the resulting emotion of dissatisfaction, they aim to avoid the inability to fully satisfy their primary motivations (core desires) and secondary motivations (coinciding desires), after exceeding their conditional desires and underachieving their conflicting desires. This situation gives rise to an intensified impulse to avoid the inability to fully satisfy the core and coinciding desires, a phenomenon referred to as fear. Specifically, when there is increased uncertainty about the possibility of fully satisfying these desires, the intensity of the impulse, or fear, to avoid the inability to receive the reward intensifies. Conversely, when there is less uncertainty about satisfying these desires and the individual is confident about receiving the reward, the intensity of the impulse to achieve the reward strengthens. This increase in impulse intensity, driven by the certainty of reward, is referred to as determination.

Difficulties in paying the cost arise when trying to fully satisfy core desires and coinciding desires. This requires exceeding the requirements of conditional desires and falling short of the requirements of conflicting desires, which in turn necessitates managing the intensity of impulses and enduring the progressive emotion of suffering that arises. The level of suffering experienced determines the difficulty of the behavior. Individuals may try to avoid dissatisfaction by satisfying the strength of their impulses, but this can lead to conflicting choices and actions. Over-fulfilling conditional desires and under-fulfilling conflicting desires is inconsistent with the purpose of behavior, but it is necessary to achieve complete fulfillment of core desires and coinciding desires. When individuals attempt to over-fulfill conditional desires and under-fulfill conflicting desires, they may experience depression as a result of the intensity of the impulse to avoid this behavior. Conversely, when the difficulty associated with a behavior is reduced, the intensity of the impulse to receive a reward by paying the cost is strengthened, which is referred to as patience.

According to the information provided, fear arises when there is an increase in uncertainty related to receiving a reward, while depression arises when there is an increase in the difficulty associated with paying a cost. These emotions, fear and depression, act as barriers that prevent us from initiating and completing certain behaviors, and they are collectively referred to as anxiety. On the other hand, when there is an increase in the certainty of receiving a reward, the emotion of determination arises, and when there is a decrease in the difficulty of paying a cost, the emotion of patience arises. These emotions, determination and patience, serve as motivators for behavior and are collectively referred to as courage. Furthermore, both anxiety and courage are experienced when individuals anticipate the uncertainties and difficulties involved in initiating and completing actions, and these emotions are known as anticipatory emotions.

For example, when Mary goes to the park, but there is a higher probability of the ice-cream man not being there, she experiences fear, which is expressed as a strong impulse to avoid being unable to eat ice cream. Conversely, when it becomes clear that the ice-cream man will be in the park, Mary's impulse to eat ice cream intensifies, resulting in the emotion of determination. If Mary either exceeds the conditional desire to go to the park or falls short of the conflicting desire to stay home and rest, she experiences the progressive emotion of suffering. Additionally, when Mary tries to control the intensity of her impulse to eat ice cream, driven by her conditional desire and conflicting desires, she experiences the emotion of depression. Depression manifests as a strong impulse to avoid controlling the intensity of the impulse. However, when Mary is able to cycle to the park, the difficulty associated with the behavior decreases, and the intensity of her impulse to eat ice cream increases, leading to the emotion of patience.

Discussion

In this paper, we have introduced a framework for understanding the mental states of others based on the model of EoE. This framework will be frequently used in everyday conversations. For example, when a friend seeks advice, one would consider what the friend should do based on recognitions and evaluations, as presented in this paper. This means that when deciding on a course of action, one would discuss with the friend the goals to be achieved in the situation, based on the recognition of the order relationship. Additionally, based on the recognition of the condition relationship, one would discuss the ways and means of achieving the goal. Moreover, based on the dependency relationship, the advantages and disadvantages of certain behaviors would be discussed. Therefore, the model presented in this paper can be used not only to understand the mental state of others but also as a framework for consultation, problem-solving, and common human understanding. Furthermore, because the recognitions and evaluations presented here are based on laws and probabilities, the recognitions of the three relationships between desires and evaluations of reward and cost can be applied to all individuals, making the EoE model universally applicable (Strijbos & de Bruin, 2012).

Also, the EoE model presented in this paper offers insights into addressing various ToM-related issues. The model categorizes desires based on beliefs and differentiates the motivational emotions that support these desires into desirable and undesirable emotions, based on the categorization of the desire. This provides an answer to the question raised by Deonna and Teroni (2012) as to why emotions can be classified as positive or negative. For consequential and progressive emotions, emotions are positive when the intensity of the impulse can be satisfied and negative when it cannot. In terms of motivational emotions, those that contribute to greater satisfaction are considered desirable positive emotions, while those that hinder greater satisfaction are considered undesirable negative emotions. Additionally, anticipatory emotions such as determination and patience, which support desirable behavior, contribute to increasing satisfaction and are therefore positive emotions. On the other hand, emotions like fear and depression, which hinder desirable behavior and impede the increase in satisfaction, are considered negative emotions. Therefore, all emotions that arise in an individual's consciousness are driven by the goal of increasing the consequential emotion of satisfaction and can be categorized as positive or negative, depending on their contribution to increasing satisfaction.

However, the model has some limitations. First, the model of mind presented in this paper is subject to criticisms specific to economics. The model is based on assumptions, and if these assumptions are incorrect, the validity of the model itself can be questioned. However, the assumptions in this model are minimal, and it is difficult to explain individual behavior and mental states without making these assumptions. The model assumes that individuals act to fulfill their desires while considering the consequences of their actions. The assumption that individuals have desires is referred to as the assumption of desire, while the assumption that individuals think about the consequences of their actions is called the assumption of reason. When we argue against the assumption of desire, we are essentially claiming that individuals do not act to satisfy their desires or that they lack a sense of "I want to....” However, this claim is likely to be unacceptable to most people. Similarly, when we argue against the assumption of reason, we are suggesting that individuals always act spontaneously and impulsively, without considering the consequences of their actions. While there may be cases where individuals act impulsively due to an inability to control their impulses, such behavior is generally seen as undesirable, and individuals are encouraged to act based on rational thinking. Therefore, it becomes difficult to argue that individuals act without considering the consequences of their actions, as evidenced by the existence of words in human society such as goals, plans, self-control, and thoughtfulness.

Second, in the EoE model, two individuals can behave differently in response to the same situation, as long as they have different leading desires that emerge in their consciousness when perceiving the same incentives. Additionally, even if the same leading desire appears in consciousness, different knowledge can lead to different conditional desires or different conflicting desires, which can lead to different behaviors. Therefore, it is not always easy to predict the behavior of others or understand their mental states based on the EoE model. Moreover, the prediction of behavior and understanding of mental states based on the EoE model is based on the recognition of relationships among desires and does not account for systemic errors that occur in the creation of individual recognitions (Goldman & Sebanz, 2005; Saxe, 2005). Therefore, while the EoE model complements ST, constructing a complete ToM using only the EoE model is challenging, and the incomplete parts must be compensated for by other theories. For example, when two individuals behave differently in response to the same situation, the EoE will explain the differences in individual behavior only by differences in incentives and recognitions and will not consider differences in other factors. Therefore, when an individual's behavior can differ owing to factors other than incentives and recognitions, it is necessary to transform the EoE model into a hybrid model by integrating it with a theory that considers differences in other factors.