Submitted:

12 March 2024

Posted:

13 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Genetics of Psoriasis

2.1. Genes Associated with the IL23 Pathway

2.2. Limitations of GWAS

2.3. Functional Annotation of SNPs

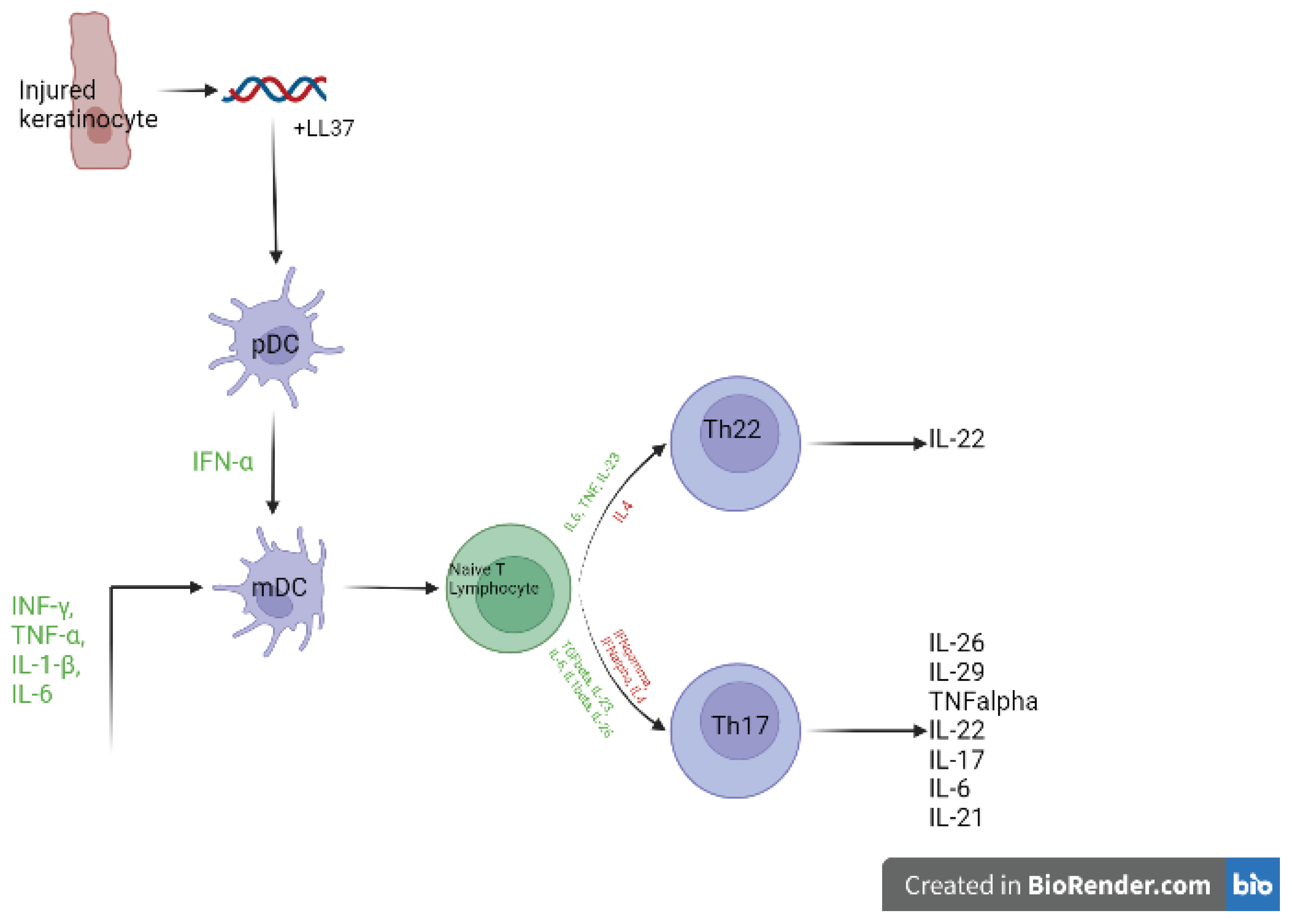

3. Pathogenesis

3.1. Main Intracellular Pathways

| Cell type | Stimulant | Intracellular signalling | Production | References |

| Keratinocyte | TNFα | NFκB | IL23 | [20,49,65] |

| IL-17 | ACT1/TRAF6 NFκB/MAPK | IL23 | ||

| IL-36 | MyD88/IRAK/ MAPK/ NFκB | IL23 | ||

| IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | CCL20 | ||

| TGFβ | ||||

| Th17 | IL-36 | MyD88/IRAK/ MAPK/ NFκB | IL-23 | [60,65] |

| IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IL-17 | ||

| IL-22 | ||||

| IFNγ | ||||

| IL-2 | ||||

| IL-29 | ||||

| ILC3 | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IL-23 | [57,65]. |

| IL-17 | ||||

| Monocytes | Mycobacterium | NFκB | IL-23 | [65]. |

| IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IL-22 | ||

| Macrophage | IFNγ | JAK/STAT1 | IL-23 | [66,67]. |

| Microbial infection | Dependent on microbe | IL-23 | ||

| IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | Increased IL23R expression | ||

| TNFα | ||||

| IL-36γ | MyD88/IRAK/ MAPK/ NFκB | IL-23 | ||

| IL-23 Macrophage | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IL-17A/F | [68]. |

| IL-22 | ||||

| IFNγ | ||||

| Myeloid dendritic cell | IFNα | JAK/STAT1/2 | IL-23 | [51]. |

| IFNγ | JAK/STAT1 | IL-23 | ||

| TNFα | NFκB | IL-23 | ||

| Langerhans cell | IL-36γ | MyD88/IRAK/ MAPK/ NFκB | IL-23 | [51] |

| Skin resident memory T cells | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | Proliferation | [69,70] |

| IL-17 | ||||

| Naïve T cell | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | Inhibition of Treg convergence | [71] |

| Th1 | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IFNγ | [65]. |

| IL-26 | ||||

| IL-17 | ||||

| IL-22 | ||||

| IL-29 | ||||

| Th22 | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IL-22 | [72]. |

| Neutrophil | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IL-17 | [57,73]. |

| LL36 | ||||

| Extracellular trap formation | ||||

| Treg | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IFNγ | [74]. |

| TNFα | ||||

| IL-17A | ||||

| γδT cell | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IL-17 | [75,76] [77] |

| IL-22 | ||||

| αβT cell | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IL-17 | [78]. |

| NK22 | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IL-22 | [49,57] |

| NK17 | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | Differentiation | |

| IL-17 | ||||

| IFNγ | ||||

| NKT1 | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IFNγ | [79] |

| MAIT17 cells | IL-23 | JAK/STAT3 | IL-17 | [80] |

4. Treatments

| Drug | Target | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ustekinumab | P40 subunit shared by IL12 and IL23 | Disrupts Th1 and Th17 differentiation and IL12 and IL23 signaling | [64,96] |

| GuselkumabTildrakizumabRisankizumab | P19 subunit of IL23 | Disrupt Th17 and IL23 signaling | [57,90,93,97,98] |

| SecukinumabIxekinumab | IL17A | Prevents both IL17A homodimers and IL17a-IL17F heterodimers binding to their receptors. | [21,57,64,99,100] |

| Brodalumab | IL17RA | Due to the commonality of the IL17RA chain in receptor complexes, interrupts signaling of IL-17A, IL-17C and IL-17F homodimers and the IL-17A/F heterodimer | |

| Bimekizumab | IL17A/F | Prevents IL17A and F homodimers and the IL17A-IL17F homodimer binding to their receptors. | [95] |

| EtanerceptAdalimumabInfliximabCertolizumab | TNF-α | Indirect impact on IL17, by regulation of IL23 production from myeloid or CD11c+ dendritic cells. | [57,64,101] |

4.1. The Need for Personalised Stratified Medicine in Psoriasis

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Barker J. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1301-15.

- Myers, W.A.; Gottlieb, A.B.; Mease, P. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: clinical features and disease mechanisms. Clin. Dermatol. 2006, 24, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health, O. Global report on psoriasis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 2016.

- Michalek, I.; Loring, B.; John, S. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 31, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.A.N.; Armstrong, A.W. Clinical and Histologic Diagnostic Guidelines for Psoriasis: A Critical Review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2012, 44, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB, Jr., Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(3 Pt 1):401-7.

- PCDS PCDS-. Psoriasis: an overview and chronic plaque psoriasis [Webpage]. 2022 [cited 2022 22/11/2022]. Available from: https://www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/psoriasis-an-overview.

- Capon, F.; Semprini, S.; Novelli, G.; Chimenti, S.; Fabrizi, G.; Zambruno, G.; Murgia, S.; Carcassi, C.; Fazio, M.; Mingarelli, R.; et al. Fine Mapping of the PSORS4 Psoriasis Susceptibility Region on Chromosome 1q21. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2001, 116, 728–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange A, Capon F, Spencer CC, Knight J, Weale ME, Allen MH, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies new psoriasis susceptibility loci and an interaction between HLA-C and ERAP1. Nat Genet. 2010;42(11):985-90.

- Hwang, S.T.; Nijsten, T.; Elder, J.T. Recent Highlights in Psoriasis Research. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, L.C.; Stuart, P.E.; Tian, C.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Das, S.; Zawistowski, M.; Ellinghaus, E.; Barker, J.N.; Chandran, V.; Dand, N.; et al. Large scale meta-analysis characterizes genetic architecture for common psoriasis associated variants. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray-Jones, H. Defining the key biological and genetic mechanisms involved in psoriasis: University of Manchester; 2018.

- Lambert, S.; Swindell, W.R.; Tsoi, L.C.; Stoll, S.W.; Elder, J.T. Dual Role of Act1 in Keratinocyte Differentiation and Host Defense: TRAF3IP2 Silencing Alters Keratinocyte Differentiation and Inhibits IL-17 Responses. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 1501–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellett M, Meier B, Mohanan D, Schairer R, Cheng P, Satoh TK, et al. CARD14 Gain-of-Function Mutation Alone Is Sufficient to Drive IL-23/IL-17-Mediated Psoriasiform Skin Inflammation In Vivo. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(9):2010-23.

- Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, G.; Huang, J.; Songyang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Lin, X. Gain-of-Function Mutation of Card14 Leads to Spontaneous Psoriasis-like Skin Inflammation through Enhanced Keratinocyte Response to IL-17A. Immunity 2018, 49, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yao, Q.; Mariscal, A.G.; Wu, X.; Hülse, J.; Pedersen, E.; Helin, K.; Waisman, A.; Vinkel, C.; Thomsen, S.F.; et al. Epigenetic control of IL-23 expression in keratinocytes is important for chronic skin inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mössner, R.; Wilsmann-Theis, D.; Oji, V.; Gkogkolou, P.; Löhr, S.; Schulz, P.; Körber, A.; Prinz, J.; Renner, R.; Schäkel, K.; et al. The genetic basis for most patients with pustular skin disease remains elusive. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 178, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Kennedy, P.J.; Nestler, E.J. Epigenetics of the Depressed Brain: Role of Histone Acetylation and Methylation. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Zeng, J.; Yuan, J.; Deng, X.; Huang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, P.; Feng, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; et al. MicroRNA-210 overexpression promotes psoriasis-like inflammation by inducing Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2551–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, Y.; Cui, L.; Shi, Y.; Guo, C. Advances in the pathogenesis of psoriasis: from keratinocyte perspective. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebwohl, M.; Strober, B.; Menter, A.; Gordon, K.; Weglowska, J.; Puig, L.; Papp, K.; Spelman, L.; Toth, D.; Kerdel, F.; et al. Phase 3 Studies Comparing Brodalumab with Ustekinumab in Psoriasis. New Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1318–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart Philip E, Nair Rajan P, Tsoi Lam C, Tejasvi T, Das S, Kang Hyun M, et al. Genome-wide Association Analysis of Psoriatic Arthritis and Cutaneous Psoriasis Reveals Differences in Their Genetic Architecture. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2015;97(6):816-36.

- Tsoi, L.C.; Spain, S.L.; Knight, J.; Ellinghaus, E.; Stuart, P.E.; Capon, F.; Ding, J.; Li, Y.; Tejasvi, T.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; et al. Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, K.; Kullo, I.J. Methods for the selection of tagging SNPs: a comparison of tagging efficiency and performance. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 15, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, K.K.-H.; Marson, A.; Zhu, J.; Kleinewietfeld, M.; Housley, W.J.; Beik, S.; Shoresh, N.; Whitton, H.; Ryan, R.J.H.; Shishkin, A.A.; et al. Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature 2015, 518, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Sun, L.; Yin, X.; Gao, J.; Sheng, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; He, C.; Qiu, Y.; Wen, G.; et al. Whole-exome SNP array identifies 15 new susceptibility loci for psoriasis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray-Jones, H. Defining the key biological and genetic mechanisms involved in psoriasis. Manchester: University of Manchester; 2016.

- Ray-Jones, H.; Eyre, S.; Barton, A.; Warren, R.B. One SNP at a Time: Moving beyond GWAS in Psoriasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filkor, K.; Hegedűs, Z.; Szász, A.; Tubak, V.; Kemény, L.; Kondorosi. ; Nagy, I. Genome Wide Transcriptome Analysis of Dendritic Cells Identifies Genes with Altered Expression in Psoriasis. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e73435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, A.; Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Dewell, S.; Krueger, J.G. Transcriptional Profiling of Psoriasis Using RNA-seq Reveals Previously Unidentified Differentially Expressed Genes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Li, K.; Fuentes-Duculan, J.; Hayden, K.; Brodmerkel, C.; Krueger, J.G. Expanding the Psoriasis Disease Profile: Interrogation of the Skin and Serum of Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 2552–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, A.P.; Hong, E.L.; Hariharan, M.; Cheng, Y.; Schaub, M.A.; Kasowski, M.; Karczewski, K.J.; Park, J.; Hitz, B.C.; Weng, S.; et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.D.; Kellis, M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 40, D930–D934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consortium, G. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science. 2020;369(6509):1318-30.

- Fairfax, B.P.; Humburg, P.; Makino, S.; Naranbhai, V.; Wong, D.; Lau, E.; Jostins, L.; Plant, K.; Andrews, R.; McGee, C.; et al. Innate Immune Activity Conditions the Effect of Regulatory Variants upon Monocyte Gene Expression. Science 2014, 343, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding J, Gudjonsson JE, Liang L, Stuart PE, Li Y, Chen W, et al. Gene expression in skin and lymphoblastoid cells: Refined statistical method reveals extensive overlap in cis-eQTL signals. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(6):779-89.

- Joehanes, R.; Zhang, X.; Huan, T.; Yao, C.; Ying, S.-X.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Demirkale, C.Y.; Feolo, M.L.; Sharopova, N.R.; Sturcke, A.; et al. Integrated genome-wide analysis of expression quantitative trait loci aids interpretation of genomic association studies. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmiedel BJ, Singh D, Madrigal A, Valdovino-Gonzalez AG, White BM, Zapardiel-Gonzalo J, et al. Impact of Genetic Polymorphisms on Human Immune Cell Gene Expression. Cell. 2018;175(6):1701-15.e16.

- Shi, C.; Ray-Jones, H.; Ding, J.; Duffus, K.; Fu, Y.; Gaddi, V.P.; Gough, O.; Hankinson, J.; Martin, P.; McGovern, A.; et al. Chromatin Looping Links Target Genes with Genetic Risk Loci for Dermatological Traits. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 1975–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden, N.H.; Broome, L.R.; Dudbridge, F.; Johnson, N.; Orr, N.; Schoenfelder, S.; Nagano, T.; Andrews, S.; Wingett, S.; Kozarewa, I.; et al. Unbiased analysis of potential targets of breast cancer susceptibility loci by Capture Hi-C. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 1854–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifsud, B.; Tavares-Cadete, F.; Young, A.N.; Sugar, R.; Schoenfelder, S.; Ferreira, L.; Wingett, S.W.; Andrews, S.; Grey, W.; A Ewels, P.; et al. Mapping long-range promoter contacts in human cells with high-resolution capture Hi-C. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burren OS, Rubio García A, Javierre BM, Rainbow DB, Cairns J, Cooper NJ, et al. Chromosome contacts in activated T cells identify autoimmune disease candidate genes. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):165.

- Hansen, A.S.; Cattoglio, C.; Darzacq, X.; Tjian, R. Recent evidence that TADs and chromatin loops are dynamic structures. Nucleus 2017, 9, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.J.; Barajas, B.C.; Furlan-Magaril, M.; Lopez-Pajares, V.; Mumbach, M.R.; Howard, I.; Kim, D.S.; Boxer, L.D.; Cairns, J.; Spivakov, M.; et al. Lineage-specific dynamic and pre-established enhancer–promoter contacts cooperate in terminal differentiation. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christova, R. Chapter Four - Detecting DNA–Protein Interactions in Living Cells—ChIP Approach. In: Donev R, editor. Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology. 91: Academic Press; 2013. p. 101-33.

- Simeonov, D.R.; Gowen, B.G.; Boontanrart, M.; Roth, T.L.; Gagnon, J.D.; Mumbach, M.R.; Satpathy, A.T.; Lee, Y.; Bray, N.L.; Chan, A.Y.; et al. Discovery of stimulation-responsive immune enhancers with CRISPR activation. Nature 2017, 549, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton IB, D’Ippolito AM, Vockley CM, Thakore PI, Crawford GE, Reddy TE, et al. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):510-7.

- Reali, E.; Ferrari, D. From the Skin to Distant Sites: T Cells in Psoriatic Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vičić, M.; Kaštelan, M.; Brajac, I.; Sotošek, V.; Massari, L.P. Current Concepts of Psoriasis Immunopathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Tan Z, Liu H, Liu Z, Wu Y, Li J. Expression of plasmacytoid dendritic cells, IRF-7, IFN-alpha mRNA in the lesions of psoriasis vulgaris. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2006;26(6):747-9.

- Wang, A.; Bai, Y. Dendritic cells: The driver of psoriasis. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestle FO, Conrad C, Tun-Kyi A, Homey B, Gombert M, Boyman O, et al. Plasmacytoid predendritic cells initiate psoriasis through interferon-alpha production. J Exp Med. 2005;202(1):135-43.

- Okada, Y.; Wu, D.; Trynka, G.; Raj, T.; Terao, C.; Ikari, K.; Kochi, Y.; Ohmura, K.; Suzuki, A.; Yoshida, S.; et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature 2014, 506, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueyama, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Tsujii, K.; Furue, Y.; Imura, C.; Shichijo, M.; Yasui, K. Mechanism of pathogenesis of imiquimod-induced skin inflammation in the mouse: A role for interferon-alpha in dendritic cell activation by imiquimod. J. Dermatol. 2014, 41, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiricozzi, A.; Romanelli, P.; Volpe, E.; Borsellino, G.; Romanelli, M. Scanning the Immunopathogenesis of Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malissen, B.; Tamoutounour, S.; Henri, S. The origins and functions of dendritic cells and macrophages in the skin. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes JE, Yan BY, Chan TC, Krueger JG. Discovery of the IL-23/IL-17 Signaling Pathway and the Treatment of Psoriasis. The Journal of Immunology. 2018;201(6):1605-13.

- Wojno, E.D.T.; Hunter, C.A.; Stumhofer, J.S. The Immunobiology of the Interleukin-12 Family: Room for Discovery. Immunity 2019, 50, 851–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Trepicchio, W.L.; Oestreicher, J.L.; Pittman, D.; Wang, F.; Chamian, F.; Dhodapkar, M.; Krueger, J.G. Increased Expression of Interleukin 23 p19 and p40 in Lesional Skin of Patients with Psoriasis Vulgaris. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 199, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calautti, E.; Avalle, L.; Poli, V. Psoriasis: A STAT3-Centric View. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvist-Hansen, A.; Hansen, P.R.; Skov, L. Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis with JAK Inhibitors: A Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 10, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, M.; Muromoto, R.; Akimoto, T.; Sekine, Y.; Kon, S.; Diwan, M.; Maeda, H.; Togi, S.; Shimoda, K.; Oritani, K.; et al. Tyk2 is a therapeutic target for psoriasis-like skin inflammation. Int. Immunol. 2013, 26, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, D.; Shen, R.; Li, D.; Hu, Q.; Yan, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, F.; Wan, H.; Dong, P.; et al. Discovery of a novel RORγ antagonist with skin-restricted exposure for topical treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreschi, K.; Balato, A.; Enerbäck, C.; Sabat, R. Therapeutics targeting the IL-23 and IL-17 pathway in psoriasis. Lancet 2021, 397, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W.; Rutz, S.; Crellin, N.K.; Valdez, P.A.; Hymowitz, S.G. Regulation and Functions of the IL-10 Family of Cytokines in Inflammation and Disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 29, 71–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madonna, S.; Girolomoni, G.; Dinarello, C.A.; Albanesi, C. The Significance of IL-36 Hyperactivation and IL-36R Targeting in Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgewood, C.; Fearnley, G.W.; Berekmeri, A.; Laws, P.; Macleod, T.; Ponnambalam, S.; Stacey, M.; Graham, A.; Wittmann, M. IL-36γ Is a Strong Inducer of IL-23 in Psoriatic Cells and Activates Angiogenesis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zhu, L.; Tian, H.; Sun, H.-X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y. IL-23-induced macrophage polarization and its pathological roles in mice with imiquimod-induced psoriasis. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuk, S.; Schlums, H.; Sérézal, I.G.; Martini, E.; Chiang, S.C.; Marquardt, N.; Gibbs, A.; Detlofsson, E.; Introini, A.; Forkel, M.; et al. CD49a Expression Defines Tissue-Resident CD8+ T Cells Poised for Cytotoxic Function in Human Skin. Immunity 2017, 46, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokura, Y.; Phadungsaksawasdi, P.; Kurihara, K.; Fujiyama, T.; Honda, T. Pathophysiology of Skin Resident Memory T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Wang, M.; Gao, H.; Zheng, A.; Li, J.; Mu, D.; Tong, J. The Role of Helper T Cells in Psoriasis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 788940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhen T, Geiger R, Jarrossay D, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Production of interleukin 22 but not interleukin 17 by a subset of human skin-homing memory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(8):857-63.

- Menter, A.; Krueger, G.G.; Paek, S.Y.; Kivelevitch, D.; Adamopoulos, I.E.; Langley, R.G. Interleukin-17 and Interleukin-23: A Narrative Review of Mechanisms of Action in Psoriasis and Associated Comorbidities. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 11, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi Y, Chen Z, Zhao Z, Yu Y, Fan H, Xu X, et al. IL-21 Induces an Imbalance of Th17/Treg Cells in Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis Patients. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1865.

- Cai, Y.; Xue, F.; Quan, C.; Qu, M.; Liu, N.; Zhang, Y.; Fleming, C.; Hu, X.; Zhang, H.-G.; Weichselbaum, R.; et al. A Critical Role of the IL-1β–IL-1R Signaling Pathway in Skin Inflammation and Psoriasis Pathogenesis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 139, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartwig T, Pantelyushin S, Croxford AL, Kulig P, Becher B. Dermal IL-17-producing γδ T cells establish long-lived memory in the skin. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45(11):3022-33.

- Polese, B.; Zhang, H.; Thurairajah, B.; King, I.L. Innate Lymphocytes in Psoriasis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai Y, Shen X, Ding C, Qi C, Li K, Li X, et al. Pivotal role of dermal IL-17-producing γδ T cells in skin inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35(4):596-610.

- Yip, K.H.; Papadopoulos, M.; Pant, H.; Tumes, D.J. The role of invariant T cells in inflammation of the skin and airways. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019, 41, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisarska MM, Dunne MR, O’Shea D, Hogan AE. Interleukin-17 producing mucosal associated invariant T cells - emerging players in chronic inflammatory diseases? European Journal of Immunology. 2020;50(8):1098-108.

- Tang, L.; Yang, X.; Liang, Y.; Xie, H.; Dai, Z.; Zheng, G. Transcription Factor Retinoid-Related Orphan Receptor γt: A Promising Target for the Treatment of Psoriasis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldminz AM, Au SC, Kim N, Gottlieb AB, Lizzul PF. NF-κB: An essential transcription factor in psoriasis. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2013;69(2):89-94.

- Ramnath D, Tunny K, Hohenhaus DM, Pitts CM, Bergot AS, Hogarth PM, et al. TLR3 drives IRF6-dependent IL-23p19 expression and p19/EBI3 heterodimer formation in keratinocytes. Immunol Cell Biol. 2015;93(9):771-9.

- Lysell, J.; Padyukov, L.; Kockum, I.; Nikamo, P.; Ståhle, M. Genetic Association with ERAP1 in Psoriasis Is Confined to Disease Onset after Puberty and Not Dependent on HLA-C*06. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahil SK, Wilson N, Dand N, Reynolds NJ, Griffiths CEM, Emsley R, et al. Psoriasis treat to target: defining outcomes in psoriasis using data from a real-world, population-based cohort study (the British Association of Dermatologists Biologics and Immunomodulators Register, BADBIR). Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(5):1158-66.

- Reich K, Gooderham M, Green L, Bewley A, Zhang Z, Khanskaya I, et al. The efficacy and safety of apremilast, etanercept and placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: 52-week results from a phase IIIb, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (LIBERATE). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(3):507-17.

- Barker, J.; Hoffmann, M.; Wozel, G.; Ortonne, J.-P.; Zheng, H.; van Hoogstraten, H.; Reich, K. Efficacy and safety of infliximab vs. methotrexate in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of an open-label, active-controlled, randomized trial (RESTORE1). Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 165, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurat JH, Stingl G, Dubertret L, Papp K, Langley RG, Ortonne JP, et al. Efficacy and safety results from the randomized controlled comparative study of adalimumab vs. methotrexate vs. placebo in patients with psoriasis (CHAMPION). Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(3):558-66.

- ten Bergen LL, Petrovic A, Krogh Aarebrot A, Appel S. The TNF/IL-23/IL-17 axis—Head-to-head trials comparing different biologics in psoriasis treatment. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2020;92(4):e12946.

- Gordon, K.B.; Strober, B.; Lebwohl, M.; Augustin, M.; Blauvelt, A.; Poulin, Y.; A Papp, K.; Sofen, H.; Puig, L.; Foley, P.; et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and ustekinumab-controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet 2018, 392, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, K.A.; Blauvelt, A.; Bukhalo, M.; Gooderham, M.; Krueger, J.G.; Lacour, J.-P.; Menter, A.; Philipp, S.; Sofen, H.; Tyring, S.; et al. Risankizumab versus Ustekinumab for Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis. New Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1551–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langley RG, Tsai TF, Flavin S, Song M, Randazzo B, Wasfi Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate response to ustekinumab: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III NAVIGATE trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):114-23.

- Reich, K.; Armstrong, A.W.; Foley, P.; Song, M.; Wasfi, Y.; Randazzo, B.; Li, S.; Shen, Y.-K.; Gordon, K.B. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: Results from the phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator–controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 76, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blauvelt A, Papp K, Gottlieb A, Jarell A, Reich K, Maari C, et al. A head-to-head comparison of ixekizumab vs. guselkumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: 12-week efficacy, safety and speed of response from a randomized, double-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(6):1348-58.

- Gordon, K.B.; Foley, P.; Krueger, J.G.; Pinter, A.; Reich, K.; Vender, R.; Vanvoorden, V.; Madden, C.; White, K.; Cioffi, C.; et al. Bimekizumab efficacy and safety in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE READY): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths CE, Strober BE, van de Kerkhof P, Ho V, Fidelus-Gort R, Yeilding N, et al. Comparison of ustekinumab and etanercept for moderate-to-severe psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(2):118-28.

- Sawyer, L.M.; Malottki, K.; Sabry-Grant, C.; Yasmeen, N.; Wright, E.; Sohrt, A.; Borg, E.; Warren, R.B. Assessing the relative efficacy of interleukin-17 and interleukin-23 targeted treatments for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of PASI response. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0220868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong AW, Puig L, Joshi A, Skup M, Williams D, Li J, et al. Comparison of Biologics and Oral Treatments for Plaque Psoriasis: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(3):258-69.

- Blauvelt, A.; Reich, K.; Tsai, T.-F.; Tyring, S.; Vanaclocha, F.; Kingo, K.; Ziv, M.; Pinter, A.; Vender, R.; Hugot, S.; et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis up to 1 year: Results from the CLEAR study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 76, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, K.B.; Blauvelt, A.; Papp, K.A.; Langley, R.G.; Luger, T.; Ohtsuki, M.; Reich, K.; Amato, D.; Ball, S.G.; Braun, D.K.; et al. Phase 3 Trials of Ixekizumab in Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis. New Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE) NIfHaCE. Psoriasis 2022 [Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/psoriasis/management/trunk-limbs/.

- Menting SP, Coussens E, Pouw MF, van den Reek JM, Temmerman L, Boonen H, et al. Developing a Therapeutic Range of Adalimumab Serum Concentrations in Management of Psoriasis: A Step Toward Personalized Treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(6):616-22.

- Elberdín, L.; Fernández-Torres, R.M.; Paradela, S.; Mateos, M.; Blanco, E.; Balboa-Barreiro, V.; Gómez-Besteiro, M.I.; Outeda, M.; Martín-Herranz, I.; Fonseca, E. Biologic Therapy for Moderate to Severe Psoriasis. Real-World Follow-up of Patients Who Initiated Biologic Therapy at Least 10 Years Ago. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsakok, T.; Rispens, T.; Spuls, P.; Nast, A.; Smith, C.; Reich, K. Immunogenicity of biologic therapies in psoriasis: Myths, facts and a suggested approach. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 35, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaisman-Mentesh, A.; Gutierrez-Gonzalez, M.; DeKosky, B.J.; Wine, Y. The Molecular Mechanisms That Underlie the Immune Biology of Anti-drug Antibody Formation Following Treatment With Monoclonal Antibodies. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazonovs, A.; Kennedy, N.A.; Moutsianas, L.; Heap, G.A.; Rice, D.L.; Reppell, M.; Bewshea, C.M.; Chanchlani, N.; Walker, G.J.; Perry, M.H.; et al. HLA-DQA1*05 Carriage Associated With Development of Anti-Drug Antibodies to Infliximab and Adalimumab in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hässler, S.; Bachelet, D.; Duhaze, J.; Szely, N.; Gleizes, A.; Abina, S.H.-B.; Aktas, O.; Auer, M.; Avouac, J.; Birchler, M.; et al. Clinicogenomic factors of biotherapy immunogenicity in autoimmune disease: A prospective multicohort study of the ABIRISK consortium. PLOS Med. 2020, 17, e1003348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Degner, J.; Davis, J.W.; Idler, K.B.; Nader, A.; Mostafa, N.M.; Waring, J.F. Identification of HLA-DRB1 association to adalimumab immunogenicity. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0195325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berna-Rico, E.; Perez-Bootello, J.; de Aragon, C.A.-J.; Gonzalez-Cantero, A. Genetic Influence on Treatment Response in Psoriasis: New Insights into Personalized Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Reek J, Coenen MJH, van de L’Isle Arias M, Zweegers J, Rodijk-Olthuis D, Schalkwijk J, et al. Polymorphisms in CD84, IL12B and TNFAIP3 are associated with response to biologics in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(5):1288-96.

- Costanzo, A.; Bianchi, L.; Flori, M.L.; Malara, G.; Stingeni, L.; Bartezaghi, M.; Carraro, L.; Castellino, G. ; the SUPREME Study Group Secukinumab shows high efficacy irrespective ofHLA-Cw6status in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque-type psoriasis: SUPREME study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 179, 1072–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzo, M.; D’adamio, S.; Silvaggio, D.; Lombardo, P.; Bianchi, L.; Talamonti, M. In which patients the best efficacy of secukinumab? Update of a real-life analysis after 136 weeks of treatment with secukinumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2019, 20, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli M, Galluzzo M, Madonna S, Scarponi C, Scaglione GL, Galluccio T, et al. HLA-Cw6 and other HLA-C alleles, as well as MICB-DT, DDX58, and TYK2 genetic variants associate with optimal response to anti-IL-17A treatment in patients with psoriasis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2021;21(2):259-70.

- van Vugt, L.; Reek, J.v.D.; Meulewaeter, E.; Hakobjan, M.; Heddes, N.; Traks, T.; Kingo, K.; Galluzzo, M.; Talamonti, M.; Lambert, J.; et al. Response to IL-17A inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab cannot be explained by genetic variation in the protein-coding and untranslated regions of the IL-17A gene: results from a multicentre study of four European psoriasis cohorts. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 34, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, R.; Carrascosa, J.; Fumero, E.; Schoenenberger, A.; Lebwohl, M.; Szepietowski, J.; Reich, K. Time to relapse after tildrakizumab withdrawal in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who were responders at week 28: post hoc analysis through 64 weeks from reSURFACE 1 trial. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 35, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauvelt A, Leonardi CL, Gooderham M, Papp KA, Philipp S, Wu JJ, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Continuous Risankizumab Therapy vs Treatment Withdrawal in Patients With Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis: A Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatology. 2020;156(6):649-58.

- Leonardi, C.L.; Kimball, A.B.; A Papp, K.; Yeilding, N.; Guzzo, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Dooley, L.T.; Gordon, K.B. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 1). Lancet 2008, 371, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, H.-Y.; Hui, R.C.-Y.; Tsai, T.-F.; Chen, Y.-C.; Liao, N.-F.C.; Chen, P.-H.; Lai, P.-J.; Wang, T.-S.; Huang, Y.-H. Predictors of time to relapse following ustekinumab withdrawal in patients with psoriasis who had responded to therapy: An 8-year multicenter study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 88, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regnault, M.M.; Konstantinou, M.; Khemis, A.; Poulin, Y.; Bourcier, M.; Amelot, F.; Livideanu, C.B.; Paul, C. Early relapse of psoriasis after stopping brodalumab: a retrospective cohort study in 77 patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, 1491–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umezawa, Y.; Torisu-Itakura, H.; Morisaki, Y.; ElMaraghy, H.; Nakajo, K.; Akashi, N.; Saeki, H. ; the Japanese Ixekizumab Study Group Long-term efficacy and safety results from an open-label phase III study (UNCOVER-J) in Japanese plaque psoriasis patients: impact of treatment withdrawal and retreatment of ixekizumab. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 33, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, K.B.; Gottlieb, A.B.; Leonardi, C.L.; Elewski, B.E.; Wang, A.; Jahreis, A.; Zitnik, R. Clinical response in psoriasis patients discontinued from and then reinitiated on etanercept therapy. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2006, 17, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottlieb, A.B.; Evans, R.; Li, S.; Dooley, L.T.; Guzzo, C.A.; Baker, D.; Bala, M.; Marano, C.W.; Menter, A. Infliximab induction therapy for patients with severe plaque-type psoriasis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2004, 51, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinco, G.; Balato, N.; Buligan, C.; Campanati, A.; Dastoli, S.; Di Meo, N.; Gisondi, P.; Lacarubba, F.; Musumeci, M.L.; Napolitano, M.; et al. A multicenter retrospective case-control study on Suspension of TNF-inhibitors and Outcomes in Psoriatic patients (STOP study). G. Ital. di Dermatol. e Venereol. 2019, 154, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shestopaloff, K.; Hollis, B.; Kwok, C.H.; Hon, C.; Hartmann, N.; Tian, C.; Wozniak, M.; Santos, L.; West, D.; et al. Response to anti-IL17 therapy in inflammatory disease is not strongly impacted by genetic background. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 110, 1817–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Locus | Notable gene(s) in literature | Study Population | Index SNP | Index SNP annotation | P-value |

| 1p36.3 | MTHFR | CHN | rs2274976 | Missense: MTHFR | 2.33 x 10-10 |

| 1p36.23 | SLC45A1, TNFRSF9 | EUR | rs11121129 | Intergenic | 1.7 x 10-8 |

| 1p36 | IL-28RA | EUR | rs7552167 | 4.2kb 5’ of IL-28RA | 8.5 x 10-12 |

| CHN | rs4649203 | 5.5kb 5’ of IL-28RA | 9.74 x 10-11 | ||

| 1p36.11 | RUNX3 | EUR | rs7536201 | 1.5kb 5’ of RUNX3 | 2.3 x 10-12 |

| 1p36.11 | ZNF683 | CHN | rs10794532 | Missense: ZNF683 | 4.18 x 10-8 |

| 1p31.3 | IL-23R | EUR | rs9988642 | 441bp 3’ of IL-23R | 1.1 x 10-26 |

| CHN | chr1: 67,421,184 (build hg18) | Nonsynonymous: IL-23R | 1.94 x 10-11 | ||

| 1p31.3 | C1orf141 | CHN | rs72933970 | Missense: C1orf141 | 1.23 x 10-8 |

| 1p31.1 | FUBP1 | EUR | rs34517439 | Intronic: DNAJB4 | 4.43 × 10−9 |

| 1q21.3 | LCE3B, LCE3D | EUR | rs6677595 | 3.6kb 3’ of LCE3B | 2.1 x 10-33 |

| CHN | rs10888501 | 175bp 3’ of LCE3E | 6.48 x 10-13 | ||

| 1q22 | AIM2 | CHN | rs2276405 | Stop-gained: AIM2 | 3.22 x 10-9 |

| 1q24.3 | FASLG | EUR | rs12118303 | Intergenic | 3.02 × 10−10 |

| 1q31.1 | LRRC7 | EUR | rs10789285 | Intergenic | 1.43 x 10-8 |

| 1q31.3 | DENND1B | EUR | rs2477077 | Intronic: DENND1B | 3.05 x 10-8 (meta) |

| 1q32.1 | IKBKE | EUR | rs41298997 | Intronic: IKBKE | 2.37 × 10−8 |

| 2p16.1 | FLJ16341, REL | EUR | rs62149416 | Intronic: FLJ16341 | 1.8 x 10-17 |

| 2p15 | B3GNT2 | EUR | rs10865331 | Intergenic | 4.7 x 10-10 |

| 2q12.1 | IL1RL1 | CHN | rs1420101 | Intronic: IL1RL1 | 1.71 x 10-10 |

| 2q24.2 | KCNH7, IFIH1 | EUR | rs17716942 | Intronic: KCNH7 | 3.3 x 10-18 |

| CHN | rs13431841 | Intronic: IFIH1 | 2.96 x 10-9 | ||

| 3p24.3 | PLCL2 | EUR | rs4685408 | Intronic: PLCL2 | 8.58 x 10-9 |

| 3q11.2 | TP63 | EUR | rs28512356 | 400bp 3’ of TP63 | 4.31 x 10-8 |

| 3q12.3 | NF-ΚBIZ | EUR | rs7637230 | Intronic: RP11-221J22.1 | 2.07 x 10-9 |

| 3q13 | CASR | CHN | rs1042636 | Missense: CASR | 1.88 x 10-10 |

| 3q26.2-q27 | GPR160 | CHN | rs6444895 | Intronic: GPR160 | 1.44 x 10-12 |

| 4q24 | NF-ΚB1 | CHN | rs1020760 | Intronic: NF-ΚB1 | 2.19 x 10-8 |

| 5p13.1 | PTGER4, CARD6 | EUR | rs114934997 | Intergenic | 1.27 x 10-8 |

| 5q14 | ZFYVE16 | CHN | rs249038 | Missense: ZFYVE16 | 2.14 x 10-8 |

| 5q15 | ERAP1, LNPEP | EUR | rs27432 | Intronic: ERAP1 | 1.9 x 10-20 |

| CHN | rs27043 | Intronic: ERAP1 | 6.50 x 10-12 | ||

| 5q31 | IL13, IL4 | EUR | rs1295685 | 3’-UTR: IL13 | 3.4 x 10-10 |

| 5q33.1 | TNIP1 | EUR | rs2233278 | 5’-UTR: TNIP1 | 2.2 x 10-42 |

| CHN | rs10036748 | Intronic: TNIP1 | 4.26 x 10-9 | ||

| 5q33.3 | IL12B | EUR | rs12188300 | Intergenic | 3.2 x 10-53 |

| CHN | rs10076782 | Intronic: RNF145 | 4.11 x 10-11 | ||

| 5q33.3 | PTTG1 | CHN | rs2431697 | Intergenic | 1.11 x 10-8 |

| 6p25.3 | EXOC2, IRF4 | EUR | rs9504361 | Intronic: EXOC2 | 2.1 x 10-11 |

| 6p22.3 | CDKAL1 | EUR | rs4712528 | Intronic: CDKAL1 | 8.4 x 10-11 |

| 6q23.3 | TRAF3IP2 | EUR | rs33980500 | Missense: TRAF3IP2 | 4.2 x 10-45 |

| TNFAIP3 | EUR | rs582757 | Intronic: TNFAIP3 | 2.2 x 10-25 | |

| 6q25.3 | TAGAP | EUR | rs2451258 | Intergenic | 3.4 x 10-8 |

| 7p14.3 | CCDC129 | CHN | rs4141001 | Missense: CCDC129 | 1.84 x 10-11 |

| 7p14.1 | ELMO1 | EUR | rs2700987 | Intronic: ELMO1 | 4.3 x 10-9 |

| 8p23.2 | CSMD1 | CHN | rs10088247 | Intronic: CSMD1 | 4.54 x 10-9 |

| 9p21.1 | DDX58 | EUR | rs11795343 | Intronic: DDX58 | 8.4 x 10-11 |

| 9q31.2 | KLF4 | EUR | rs10979182 | Intergenic | 2.3 x 10-8 |

| 10q21.2 | ZNF365 | EUR | rs2944542 | Intronic: ZNF365 | 1.76 × 10−8 |

| 10q22.2 | CAMK2G, FUT11 | EUR | rs2675662 | Intronic: CAMK2G | 7.35 x 10-9 |

| 10q22.3 | ZMIZ1 | EUR | rs1250544 | Intronic: ZMIZ1 | 3.53 x 10-8 |

| 10q23.31 | PTEN, KLLN, SNORD74 | EUR | rs76959677 | Intergenic | 2.75 × 10−8 |

| 10q24.31 | CHUK | EUR | rs61871342 | Intronic: BLOC1S2 | 1.56 × 10−9 |

| 11p15.4 | ZNF143 | CHN | rs10743108 | Missense: ZNF143 | 1.70 x 10-8 |

| 11q13 | RPS6KA4, PRDX5 | EUR | rs694739 | 256bp 5’ of AP003774.1 | 3.71 x 10-9 |

| 11q13.1 | CFL1, FIBP, FOSL1 | EUR | rs118086960 | Intronic: CFL1 | 6.89 × 10−9 |

| 11q13.1 | AP5B1 | CHN | rs610037 | Synonymous: AP5B1 | 4.29 x 10-11 |

| 11q22.3 | ZC3H12C | EUR | rs4561177 | 1.7kb 5’ of ZC3H12C | 7.7 x 10-13 |

| 11q24.3 | ETS1 | EUR | rs3802826 | Intronic: ETS1 | 9.5 x 10-10 |

| 12p13.3 | CD27, LAG3 | CHN | rs758739 | Intronic: NCAPD2 | 4.08 x 10-8 |

| 12p13.2 | KLRK1, KLRC4 | EUR | rs11053802 | Intronic: KLRC1 | 4.17 × 10−9 |

| 12q13.3 | IL-23A, STAT2 | EUR | rs2066819 | Intronic: STAT2 | 5.4 x 10-17 |

| 12q24.12 | BRAP, MAPKAPK5 | EUR | rs11065979 | Intergenic | 1.67 × 10−8 |

| 12q24.31 | IL31 | EUR | rs11059675 | Intronic: LRRC43 | 1.50 × 10−8 |

| 13q12.11 | GJB2 | CHN | rs72474224 | Missense: GJB2 | 7.46 x 10-11 |

| 13q14.11 | COG6 | EUR | rs34394770 | Intronic: COG6 | 2.65 x 10-8 |

| 13q14.11 | LOC144817 | EUR | rs9533962 | Within LOC144817 | 1.93 x 10-8 |

| 13q32.3 | UBAC2, RN7SKP9 | EUR | rs9513593 | Intronic: UBAC2 | 3.60 × 10−8 |

| 14q13.2 | NF-ΚBIA | EUR | rs8016947 | Intronic: RP11-56B11.3 | 2.5 x 10-17 |

| 13q14.11 | LOC144817 | CHN | rs12884468 | Intergenic | 1.05 x 10-8 |

| 14q23.2 | SYNE2 | CHN | rs2781377 | Stop-gained: SYNE2 | 4.21 x 10-11 |

| 14q32.2 | RP11-61O1.1 | EUR | rs142903734 | Intronic: RP11-61O1.1 | 7.15 × 10−9 |

| 15q13.3 | KLF13 | EUR | rs28624578 | Intronic: KLF13 | 9.22 × 10−10 |

| 16p13.13 | PRM3, SOCS1 | EUR | rs367569 | 1.6kb 3’ of PRM3 | 4.9 x 10-8 |

| 16p11.2 | FBXL19, PRSS53 | EUR | rs12445568 | Intronic: STX1B | 1.2 x 10-16 |

| 17q11.2 | NOS2 | EUR | rs28998802 | Intronic: NOS2 | 3.3 x 10-16 |

| 17q12 | IKZF3 | CHN | rs10852936 | Intronic: ZPBP2 | 1.96 x 10-8 |

| 17q21.2 | PTRF, STAT3, STAT5A/B | EUR | rs963986 | Intronic: PTRF | 5.3 x 10-9 |

| 17q25.1 | TRIM47, TRIM65 | EUR | rs55823223 | Intronic: TRIM65 | 1.06 × 10−8 |

| 17q25.3 | CARD14 | EUR | rs11652075 | Missense: CARD14 | 3.4 x 10-8 |

| 17q21.2 | PTRF, STAT3, STAT5A/B | CHN | rs11652075 | Missense: CARD14 | 3.46 x 10-9 |

| 17q25.3 | TMC6 | CHN | rs12449858 | Missense: TMC6 | 2.28 x 10-8 |

| 18p11.21 | PTPN2 | EUR | rs559406 | Intronic: PTPN2 | 1.19 × 10−10 |

| 18q21.2 | POL1, STARD6, MBD2 | EUR | rs545979 | Intronic: POL1 | 3.5 x 10-10 |

| 18q22.1 | SERPINB8 | CHN | rs514315 | 3′ of SERPINB8 | 5.92 x 10-9 |

| 19p13.2 | TYK2 | EUR | rs34536443 | Missense: TYK2 | 9.1 x 10-31 |

| 19p13.2 | ILF3, CARM1 | EUR | rs892085 | Intronic: QTRT1 | 3 x 10-17 |

| 19q13.33 | FUT2 | EUR | rs492602 | Synonymous: FUT2 | 6.57 × 10−13 |

| 19q13.41 | ZNF816A | CHN | rs12459008 | Missense: ZNF816 | 2.25 x 10-9 |

| 20q13.13 | RNF114 | EUR | rs1056198 | Intronic: RNF114 | 1.5 x 10-14 |

| 21q22 | RUNX1 | EUR | rs8128234 | Intronic: RUNX1 | 3.74 x 10-8 |

| 21q22.11 | IFNGR2 | CHN | rs9808753 | Missense: IFNGR2 | 2.75 x 10-8 |

| 21q22.11 | SON | CHN | rs3174808 | Missense: SON | 1.15 x 10-8 |

| 22q11.21 | UBE2L3, YDJC | EUR | rs4821124 | 1kb 3’ of UBE2L3 | 3.8 x 10-8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).