1. Introduction

Intra-abdominal cystic formations represent heterogeneous pathologies with varied localization and clinical manifestation. The first challenge in front of a giant intra-abdominal cystic lesion is identifying the starting organ [

1,

2]. The clinical picture of intra-abdominal cystic lesions varies from acute manifestations, non-specific symptoms, or accidental discovery [

3,

4]. The mass effect in giant formations causes non-specific symptomatology, which can delay the diagnosis. This phenomenon also happened in the presented case. The association of information obtained from imaging investigations [ultrasound, C.T., M.R.I.], laboratory analyses, and the clinical picture is essential to obtaining a preoperative diagnosis. However, the therapeutic strategy can be changed intraoperatively, depending on the characteristics of the lesion [

5,

6,

7]. The purpose of this work is that starting from the presented case, we tried to systematize intra-abdominal lesions according to the organ of origin and to make the preoperative diagnosis of an intra-abdominal cystic lesion in the pediatric patient easy to perform. The preoperative identification of the characteristics of an intra-abdominal formation and the effect on the adjacent organs facilitates surgical intervention and shortens the anesthetic time.

2. Case Presentation

A 2-year-old girl presents to the emergency service with a fever of 38.5 °C, loss of appetite, and apathy. The febrile syndrome started 2-3 days ago. It is slightly improved by the administration of NSAIDs, and following the pediatric consultation, the diagnostics were a mild respiratory infection. However, the apathy and lack of appetite were present for approximately 4-5 months; they evolved progressively and were added to transit disorders and weight stagnation. The patient comes from a disorganized family. The medical file was incomplete due to the family's lack of involvement. The girl was placed in the care of the state, and the delayed transfer of medical information led to the delay in the diagnosis. The child has been institutionalized for about one year, so there is no data on her health status from the first year of life. For about a week, the patient refused food, is apathetic, has reduced motor activity, refuses to mobilize, and prefers static activities. She becomes agitated when placed supine, preferring the lateral position. The clinical examination noted that the abdomen had an increased globular volume without collateral circulation and a decrease in fatty tissue on the abdomen, chest, limbs, and face. It does not present palpable adenopathies. At presentation, the patient weighs 11 kg, and I.P. is 0.65. On palpation, the abdomen is slightly depressed, without muscular contracture; palpating an abdominal tumor with liquidity character, which occupies the entire abdominal cavity, cannot be mobilized during bimanual palpation (

Figure 1).

An abdominal ultrasound was performed, highlighting a voluminous abdominopelvic cystic expansive formation with an irregular outline delimited by a thin wall. The lesions are multiloculated and multiseptate, with several solid hyperechoic areas adhering to the septa. The axial dimensions of the lesions are 160/90 mm; the described lesion moves the intestinal loops and both kidneys, with the demarcation line present posteriorly. The uterus and left ovary do not have modified echographic characters, and intraperitoneal fluid is absent.

To accurately specify the diagnosis, an abdominal pelvic MRI was performed. It shows a voluminous abdominal-pelvic cystic expansive formation, with convex contour, relatively well delimited by a thin wall, multiloculated, multiseptate, with moderate parietal gadolinophilia and at the level of the septa, partially altered content due to the presence of areas with intermediate T2 signal, with dimensions of approximately 86/157/230 mm [AP/T/CC]. The described formation presents the following reports:

- -

Superior, the lesion has a mass effect on the liver, spleen, stomach, and transverse colon, which appear displaced superiorly, with the border of separation;

- -

Inferior, the lesion comes in contact with the upper wall of the urinary bladder, with the limit of separation;

- -

Posteriorly, the lesion comes into contact with the intestinal loops

- -

Anteriorly, it comes in contact with the anterior abdominal wall

Ovaries are challenging to visualize, imprinted by the formation described—the uterus without expansive formations. The urinary bladder was examined in fullness, regular parietal contour, and homogeneous liquid. Liver with an anteroposterior diameter of the right lobe of ~ 117 mm and the lobe left ~ 65 mm, with a homogeneous structure without focal lesions. Undilated intra-/ extrahepatic bile ducts. The cholecyst is dilated, a wall with average thickness and liquid content, without stones. The spleen has a 74 mm diameter and a homogeneous structure. Pancreas, adrenal glands, and both kidneys, with normal M.R.I. appearance. Intraperitoneal liquid with a maximum thickness at the pelvic level of 10 mm. Without abdominal and pelvic adenopathy. No suspicious bone lesions were noted (

Figure 2).

Laboratory tests revealed WBC 22,000 10^3/mm^3, RBC 3.73 10^6/ul L, hemoglobin 8.99 g/dL, hematocrit 28 %, C reactive protein 7.77mg/dL, total proteins 4.8 g/dL, V.S.H. 92 mm/h, procalcitonin 3.9 ng/ml. The preoperative preparation of the patient aimed to correct the imbalances by administration of Albumin, Vitalipid, enteral solutions of electrolytes, and energetically enriched enteral solutions.

Surgical intervention was decided, and median exploratory laparotomy was performed; the abdominal formation tends to herniation when entering the peritoneal cavity. The cyst has adhesion to the peritoneum. It is multilobed and well-defined, with a thin wall through the transparency. Adhesions are lysed by digitoclasia and electrocautery. We made a breach in the cystic cavity, which decompressed and exteriorized. The tumor has a diameter of 22/15 cm after partial decompression and starts from the great omentum. It has a contact area with greater curvature of the stomach, and all the small intestinal loops are agglutinated subhepatically. The tumor was excised entirely [

Figure 3], an intraperitoneal drain was placed, and the abdominal wall was closed.

The subsequent evolution was favorable; with the resumption of intestinal transit in 24 hours, the intraperitoneal drain was removed on the fourth postoperative day. The patient remained hospitalized for 14 days, and during this period, the nutritional recovery was initiated so that in 2 months, the patient gained 1400 g in weight. Also, appetite and intestinal transit normalized. In addition, motor activity has improved, as has the patient's interest in age-specific activities. The patient was clinically and sonographically monitored at three months. The serial ultrasounds performed did not show the recurrence of the lesions.

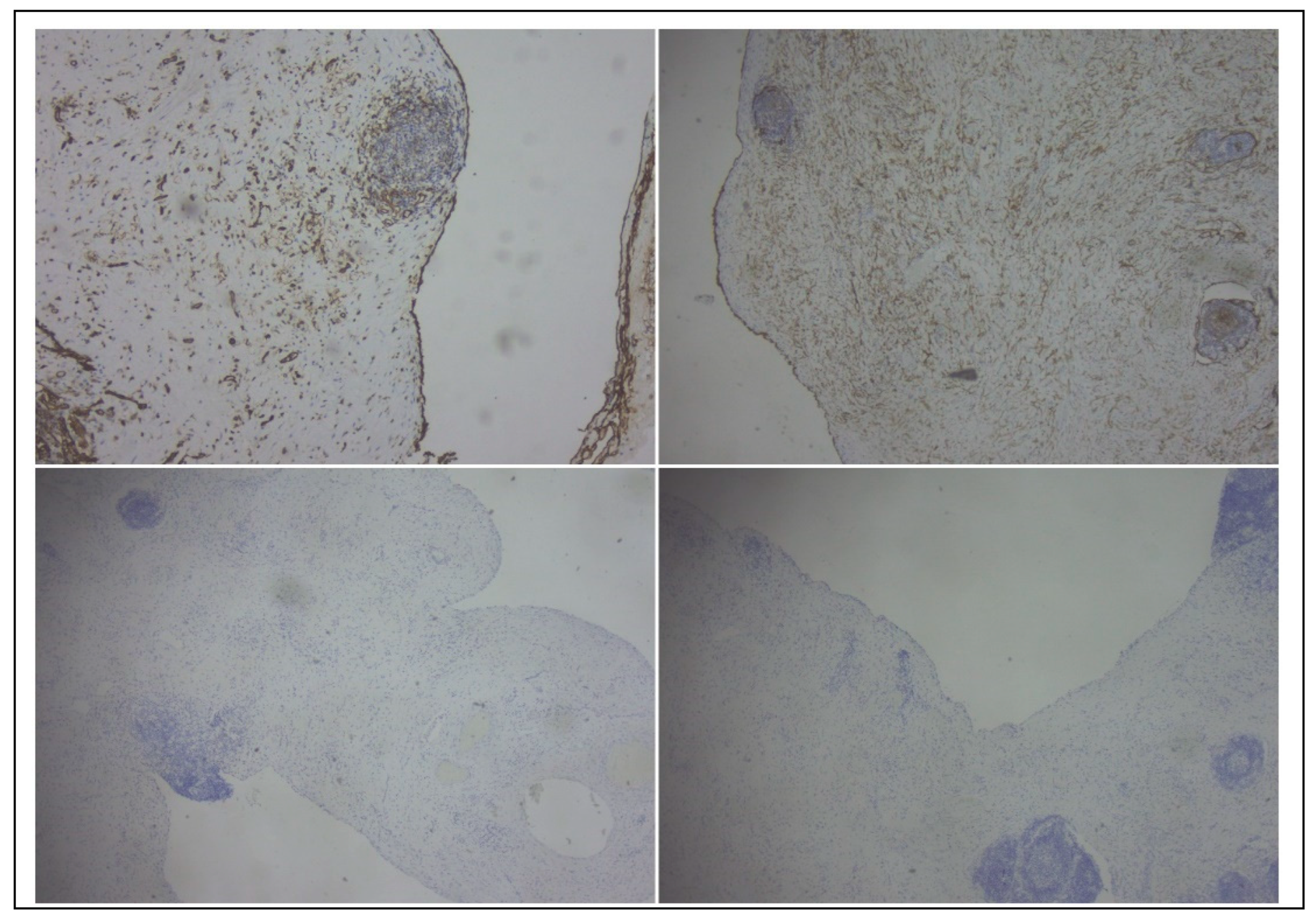

The gross examination of the resection specimen revealed a multicystic mass with a smooth external surface, measuring 17x14x4 cm, filled with serous type fluid and a soft inner lining. The walls of the cysts had variable widths, a grey-pink color, and elastic consistency. At the microscopic examination, the walls of the cysts were lined by flattened, bland cells and consisted of varying amounts of fibro collagenous stroma with lymphoid aggregates. Immunohistochemistry was performed, and the lining cells were positive for CD31 and Podoplanin and negative for WT1 and PAX8, confirming the diagnosis of cystic lymphangioma (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

3. Discussion

90% of lymphangiomas occur in children under two years of age. They are preferentially located in the head and neck [75%] and axilla [20%]. The abdominal location of lymphangiomas is rare, and precisely, this location allows the lesion to grow and cause late symptoms [

8]. Intra-abdominal lymphangioma is a rare entity. In the abdomen, lymphangioma occurs most commonly in the mesentery, followed by the omentum, mesocolon, and retroperitoneum.

Abdominal lymphangiomas are classified as follows [

9]:

I- pedicled with the clinical manifestation dominated by torsion

II- sessile located between the layers of the mesentery

III- retroperitoneal

IV- multicentric with the involvement of both intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal organs

The starting point of an intra-abdominal cystic lesion can be a parenchymal organ. The organ can be identified quickly in these conditions, allowing the doctor to focus on the differential diagnosis of organ lesions. However, with increased mobility, the cysts that develop from the rest of the intra-abdominal organs have centrifugal development and occupy the same space, the abdominal cavity [

10,

11,

12]. This determines that these lesions have similar characteristics, making it challenging to identify the organ belonging before the operation. Giant cystic formations modify the anatomical reports and become space-replacing formations, and the starting point is even more challenging to assess preoperatively. Ultrasonography, Computed tomography, and Magnetic resonance imaging studies are helpful for diagnosis and surgical planning of abdominal cyst lymphangioma by determining its location and relation to surrounding structures[

13]. Nevertheless, the careful evaluation of the characteristics of the formation, the effect on the adjacent organs, the age of the patient, and the clinical picture can provide elements of differential diagnosis [

14]. To characterize a cystic lesion from an imagistic view, the following elements must be observed: the contents of the cyst, the unilocular or multilocular type, the thickness of the walls, the presence of internal septa, the presence of calcifications, the presence of a solid component, debris or blood. In

Table 1, the characteristics of formations starting from an intra-abdominal organ.

Abdominal cystic lesions have different symptomatology depending on the organ of origin and size. However, when the lesions are extensive and become space-replacing formations, the present symptomatology is non-specific, determined by their mechanical complications [

14,

15].

The clinical picture varies from incidental discovery to acute abdomen. The most common clinical form is non-specific symptomatology of partial intestinal obstruction, anorexia with a palpable, mobile, recalcitrant, painless tumor mass, nausea, stagnation/loss of weight. Children can also present recurrent intestinal transit disorders [

16,

17,

18].

Although laparoscopic treatment is an elegant method, it was not an option due to the voluminous lesion. As cited in the specialized literature, laparoscopic techniques for the excision of voluminous lesions presuppose punction of the lesion, with partial decompression to obtain the space necessary for surgical maneuvers. Laparoscopic treatment of voluminous intra-abdominal lesions is challenging due to the increased risk of injuring the lesion, the impossibility of obtaining a suitable working space, and the risk of incompletely excising the lesion. Sclerotherapy is a form of palliative treatment with limited indications for children due to local complications and the high rate of recurrence. The main indication for sclerotherapy is the proximity of a major blood vessel, which makes surgical resection risky [

19].

The presented patient had non-specific symptoms, and her visit to the doctor was due to a respiratory infection. Lymphangioma is a benign congenital lesion that occurs due to the failure of communication in the intrauterine period [

20] between the small intestinal lymphatic vessels and the major intestinal lymphatic vessels, which causes the cystic dilation of the lymphatic space [

21,

22]. The incidence of lymphangioma of the omentum is low, with approximately 1:20,000 hospitalizations in pediatric hospitals, most under the age of 10 and with an average age of appearance of 4.5 years [

23,

24]. The condition is slightly more common in males in the pediatric population [60%] than in the adult population [predominantly in women]. Mesenteric lymphatic cysts are four times more common than omental cysts [

25,

26]. In the presented patient, the location was at the level of the greater omentum. However, the literature also describes locations such as lesions at the level of the gastrocolic or gastro-lineal ligament [

27,

28]. Therefore, surgical treatment with a curative visa is the treatment of choice. In the presented case, this objective was accomplished without recurrence postoperatively in the first six months, significantly improving the quality of life[

29].

4. Conclusions

Intra-abdominal cystic lesions represent a challenge for both the radiologist and the surgeon. The investigations cannot accurately suggest the type of injury so that the therapeutic plan can change intraoperatively. In the presented case, the lesion was proven postoperatively to have a starting point in the greater omentum and could be completely resected.

Funding

The manuscript received no funding

Data Availability Statement

On reasonable demand

Acknowledgments

I.L.C. produced the conceptual frame of the manuscript and results, A. P., M. L, and C. B. contributed to results, R.M., A.N., C.N.L., I.S., and C.I.C performed the literature screening and contributed to discussions; all author agreed to the content of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferrero L, Guanà R, Carbonaro G, Cortese MG, Lonati L, Teruzzi E, Schleef J. Cystic intra-abdominal masses in children. Pediatr Rep. 2017 Oct 6;9(3):7284. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Vega I Cystic Lymphangioma: an Uncommon Cause of Pediatric Abdominal Pain. Int J Pathol Clin Res 2017(3:)053. [CrossRef]

- Hager, J., Haeussler, B., Mueller, T., Maurer, K., Rauchenzauner, M., Fruehwirth, M.. Intraabdominal Cystic Lymphangiomas in Children: A Single Center Experience. International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, North America, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.H., Tiu, C.M., Lui, W.Y. et al. Mesenteric and omental cysts: An ultrasonographic and clinical study of 15 patients. Gastrointest Radiol 1991. 16, 311–314. [CrossRef]

- Wootton-Gorges SL, Thomas KB, Harned RK, Wu SR, Stein-Wexler R, Strain JD. Giant cystic abdominal masses in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35(12):1277-88. [CrossRef]

- Approach to Cystic Lesions in the Abdomen and Pelvis, with Radiologic-Pathologic CorrelationJoseph H. Yacoub, Jennifer A. Clark, Edina E. Paal, and Maria A. Manning RadioGraphics 2021 41:5, 1368-1386.

- Geer LL, Mittelstaedt CA, Staab EV, Gaisie G. Mesenteric cyst: sonographic appearance with C.T. correlation. Pediatr Radiol 1984;14:102-104.

- Popa, Ș.; Apostol, D.; Bîcă, O.; Benchia, D.; Sârbu, I.; Ciongradi, C.I. Prenatally Diagnosed Infantile Myofibroma of Sartorius Muscle—A Differential for Soft Tissue Masses in Early Infancy. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung MA, Brandt ML, St-Vil D, Yazbeck S. Mesenteric cysts in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1991 Nov;26(11):1306-8. [CrossRef]

- Nicolet V, Grignon A, Filiatrault D, Boisvert J. Sonographic appearance of an abdominal cystic lymphangioma. 8: J Ultrasound Med 1984;3:85-86. [CrossRef]

- del Pilar Pereira-Ospina, R. , Montoya-Sanchez, L.C., Abella-Morales, D.M. et al. Male infant patient with a mesenteric cyst in the greater and lesser omenta: a case report. Int J Emerg Med 202013, 24. [CrossRef]

- Steyaert H, Guitard J, Moscovici J, Juricic M, Vaysse P, Juskiewenski S. Abdominal cystic lymphangioma in children: benign lesions that can have a proliferative course. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(5):677-80. [CrossRef]

- Macpherson RI. Gastrointestinal tract duplications: clinical, pathologic, etiologic, and radiologic considerations. Radio- Graphics 1993;13(5):1063–1080. [CrossRef]

- Oxenberg, J. Giant Intraperitoneal Multiloculated Pseudocyst in a Male. Case Rep Surg 2016;2016:4974509. [CrossRef]

- Parada Villavicencio C, Adam SZ, Nikolaidis P, Yaghmai V, Miller FH. Imaging of the Urachus: Anomalies, Complications, and Mimics. RadioGraphics 2016;36(7):2049–2063.

- Kim SK, Lim HK, Lee SJ, Park CK. Completely isolated enteric duplication cyst: case report. Abdom Imaging 2003;28[1]:12–14. [CrossRef]

- Rattan KN, Nair VJ, Pathak M, Kumar S. Pediatric chylolymphatic mesenteric cyst: a separate entity from cystic lymphangioma—a case series. J Med Case Reports 2009;3(1):111. [CrossRef]

- de Perrot M, Bründler M, Tötsch M, Mentha G, Morel P. Mesenteric cysts: toward less confusion? Dig Surg 2000;17[4]:323–328.

- Metaxas G, Tangalos A, Pappa P, Papageorgiou I. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the mesentery: a case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol 2009;7(1):47. [CrossRef]

- C. Luzzatto, P. Midrio, T. Toffolutti, and V. Suma, "Neonatal ovarian cysts: management and follow-up," Pediatric Surgery International, vol. 16, no. 1-2, pp. 56–59, 2000. [CrossRef]

- P. de Lagausie, A. Bonnard, D. Berrebi et al., "Abdominal lymphangiomas in children: interest of the laparoscopic approach," Surgical Endoscopy2007, 21, 7:1153–1157. [CrossRef]

- P. Agarwal, P. Agarwal, R. Bagdi, S. Balagopal, M. Ramasundaram, and B. Paramaswamy, "Ovarian preservation in children for adenexal pathology, current trends in laparoscopic management and our experience," Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons, 2014;19, 2:65–69. [CrossRef]

- H. Takiff, R. Calabria, L. Yin, and B. E. Stabile, "Mesenteric cysts and intra-abdominal cystic lymphangiomas," Archives of Surgery, 1985;120, 11: 1266–1269. [CrossRef]

- Wedge JJ, Grosfeld JL, Smith JP. Abdominal masses in the newborn: 63 cases. J Urol. 1971;106(5):770-5. [CrossRef]

- KITTLE, C. F., JENKINS, H. P., AND DRAGSTEDT, L. R.: Patent Omphalomesenteric Duct and Its Relation to the Diverticulum of Meckel. Arch. Surg1947; 54: 10-36. [CrossRef]

- SHALLOW, T. A., EGER, S. A., AND WAGNER, F. B., JR.: Congenital Cystic Dilatation of the Common Bile Duct: Case Report and Review of Literature. Ann. Surg. , 1943;117: 355-386.

- PACHMAN, D. J.: Enterogenous Intramural Cysts of the Intestines. Am. J. Dis. Child.1997;58: 485-505. [CrossRef]

- Brice Antao, Jeffrey Tan, Feargal Quinn, "Laparoscopic Excision of Large Intra-Abdominal Cysts in Children: Needle Hitch Technique", Case Reports in Medicine, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Gayen, Rajarshi, et al. "Giant retroperitoneal cystic lymphangioma—a case report with review of literature." IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences 14 (2015): 69-71.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).