Submitted:

18 May 2024

Posted:

20 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

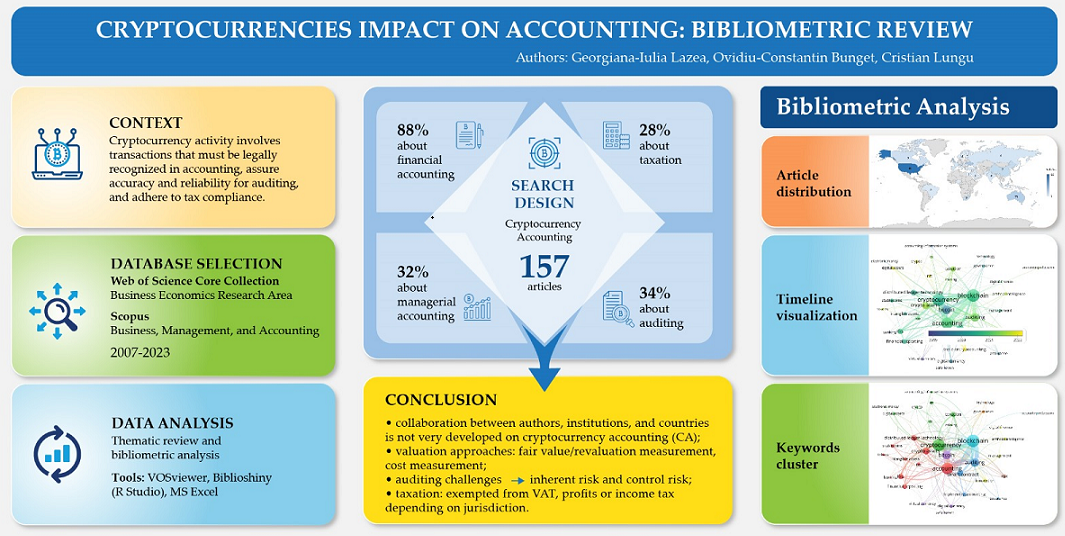

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Method

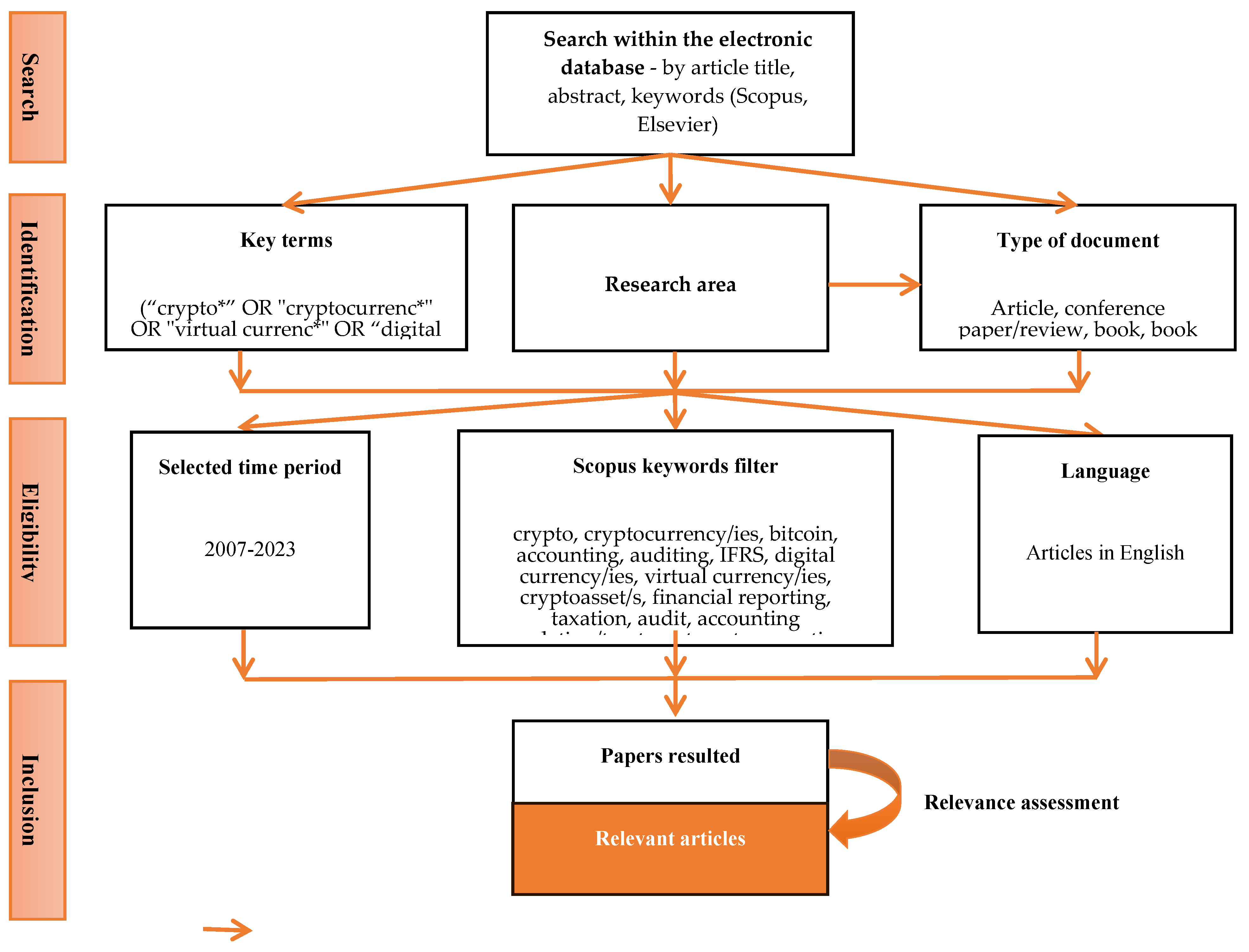

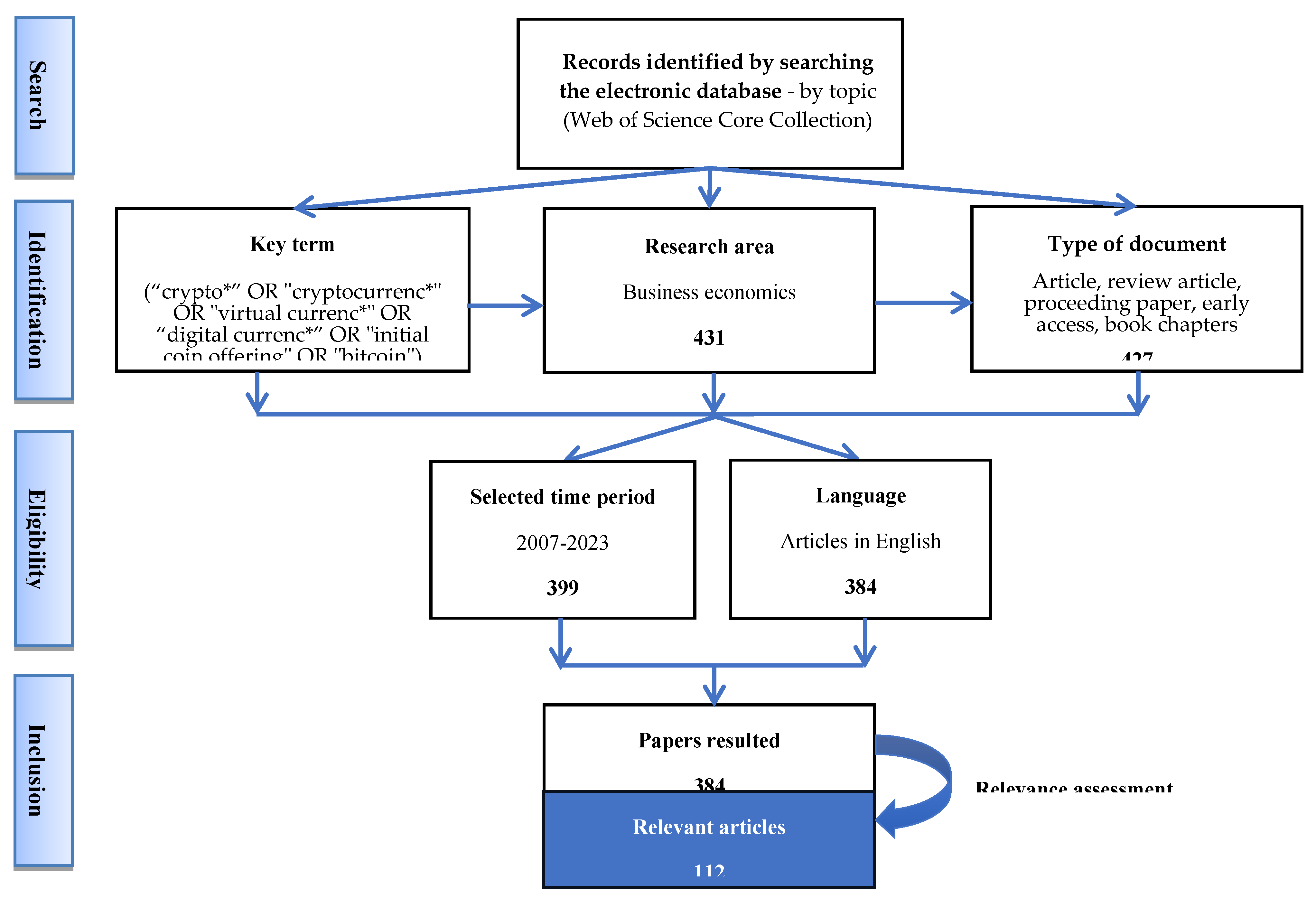

2.1. Keywords and Data Selection

2.2. Method of Data Refining and Data Analysis

3. Descriptive Bibliometric Analysis

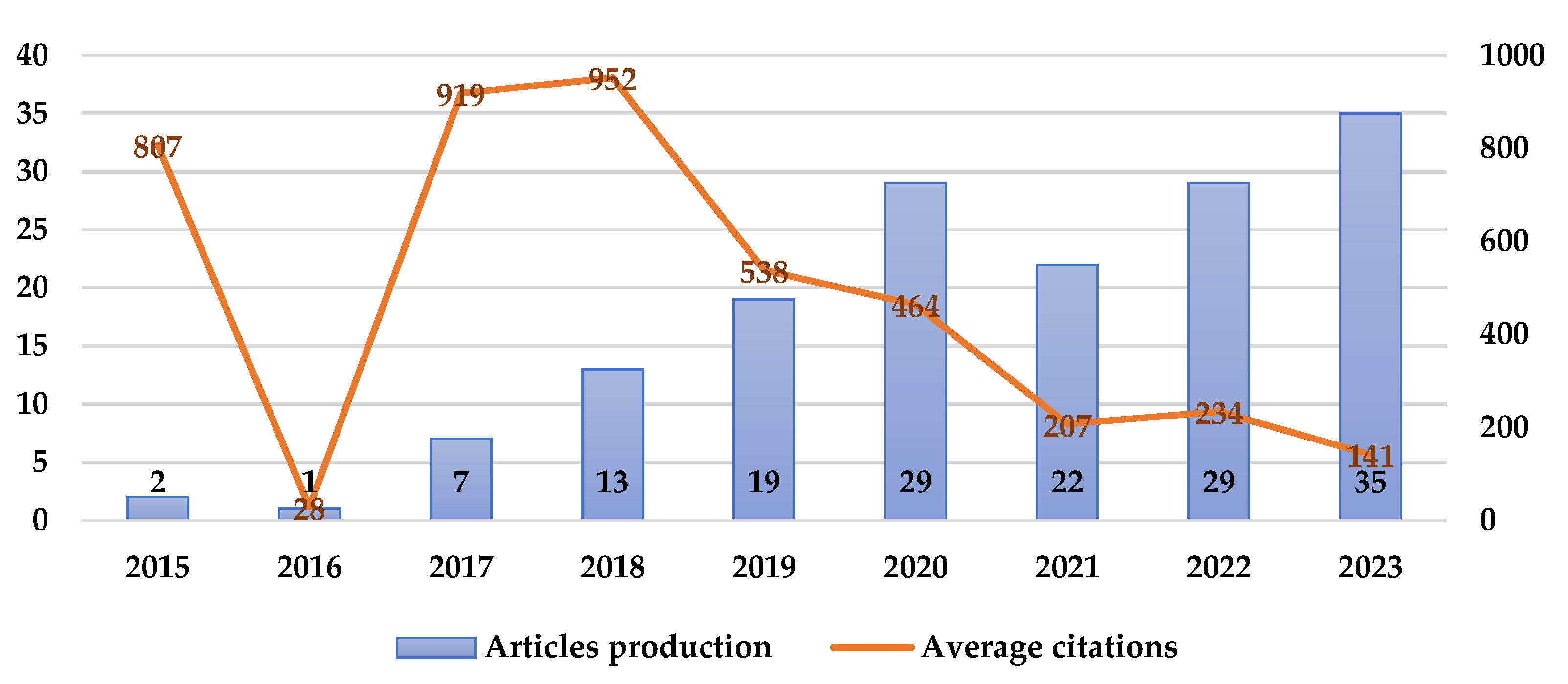

3.1. Annual Scientific Production and Citations

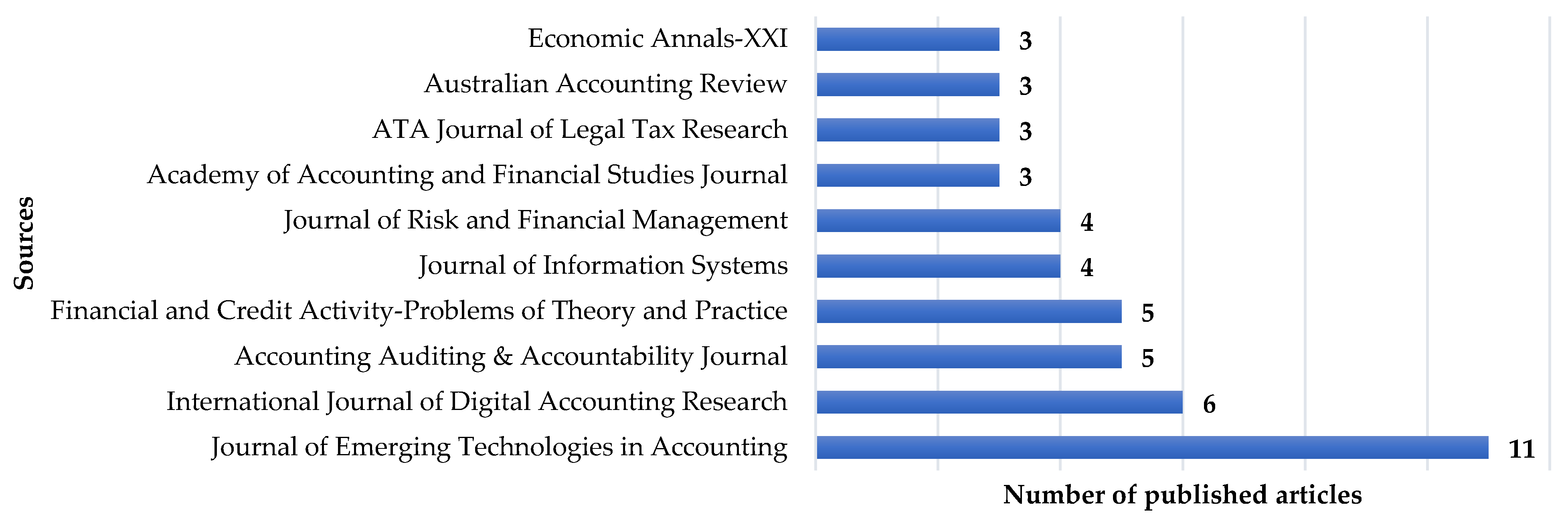

3.2. Publications’ Sources

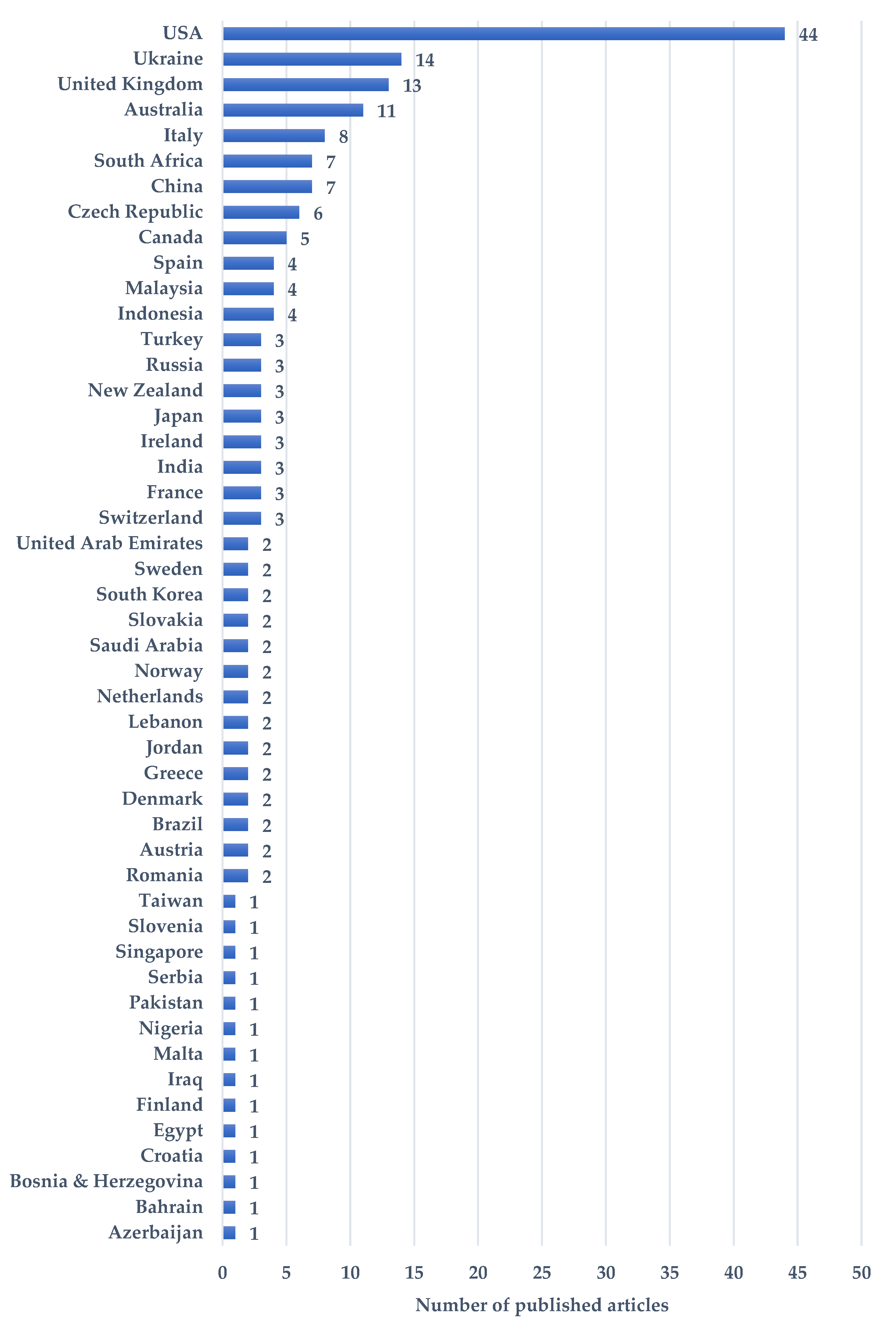

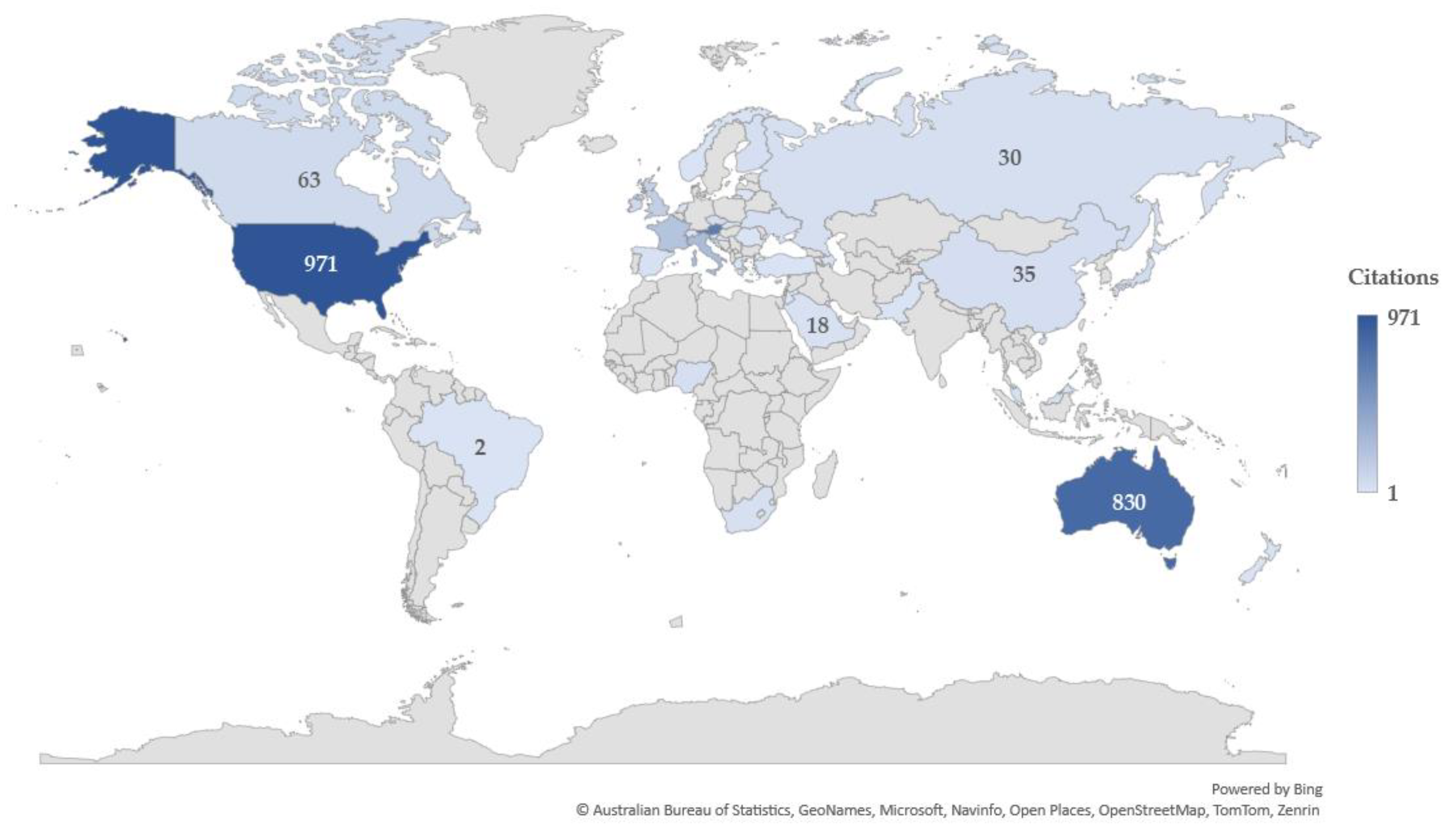

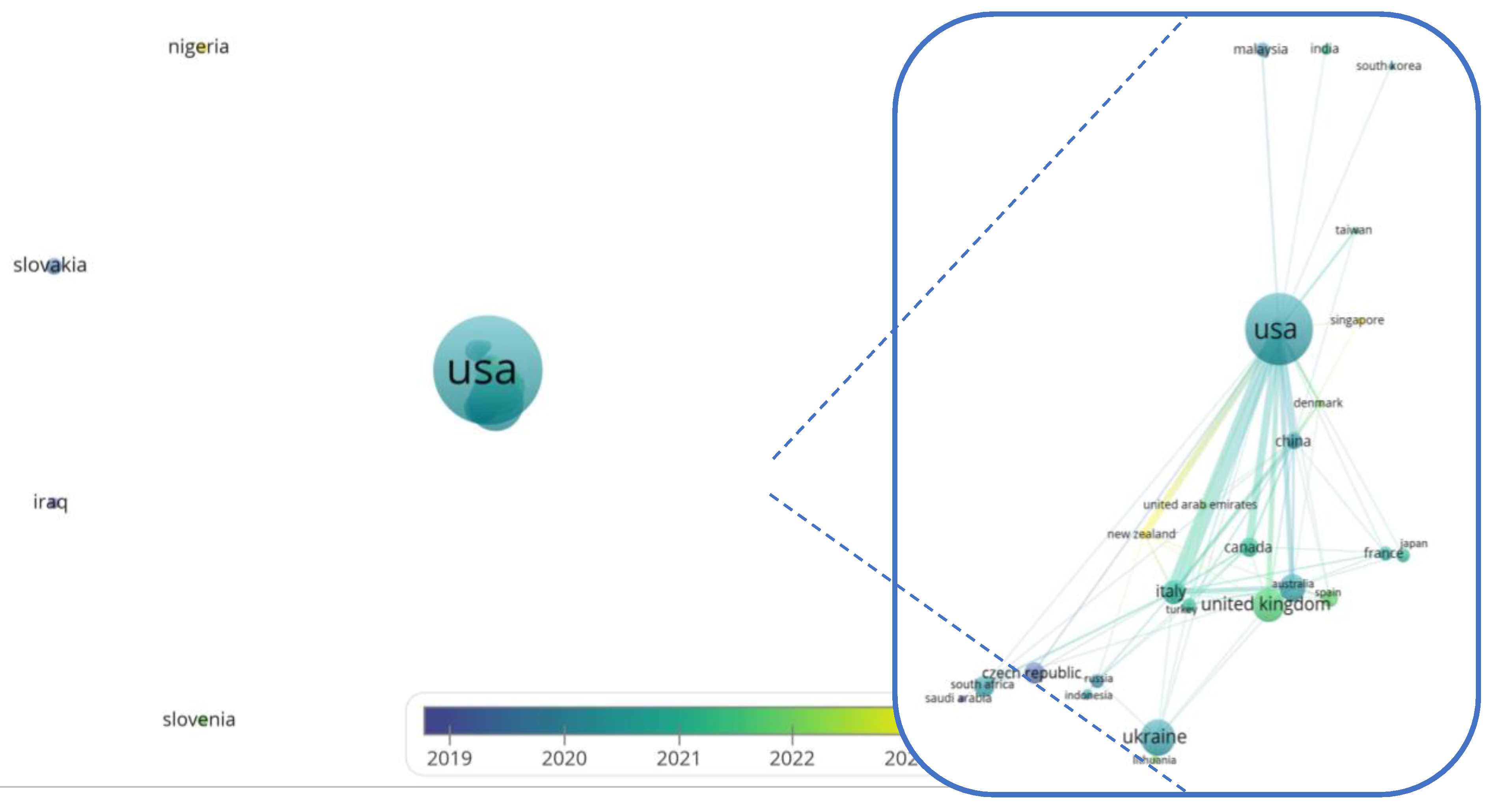

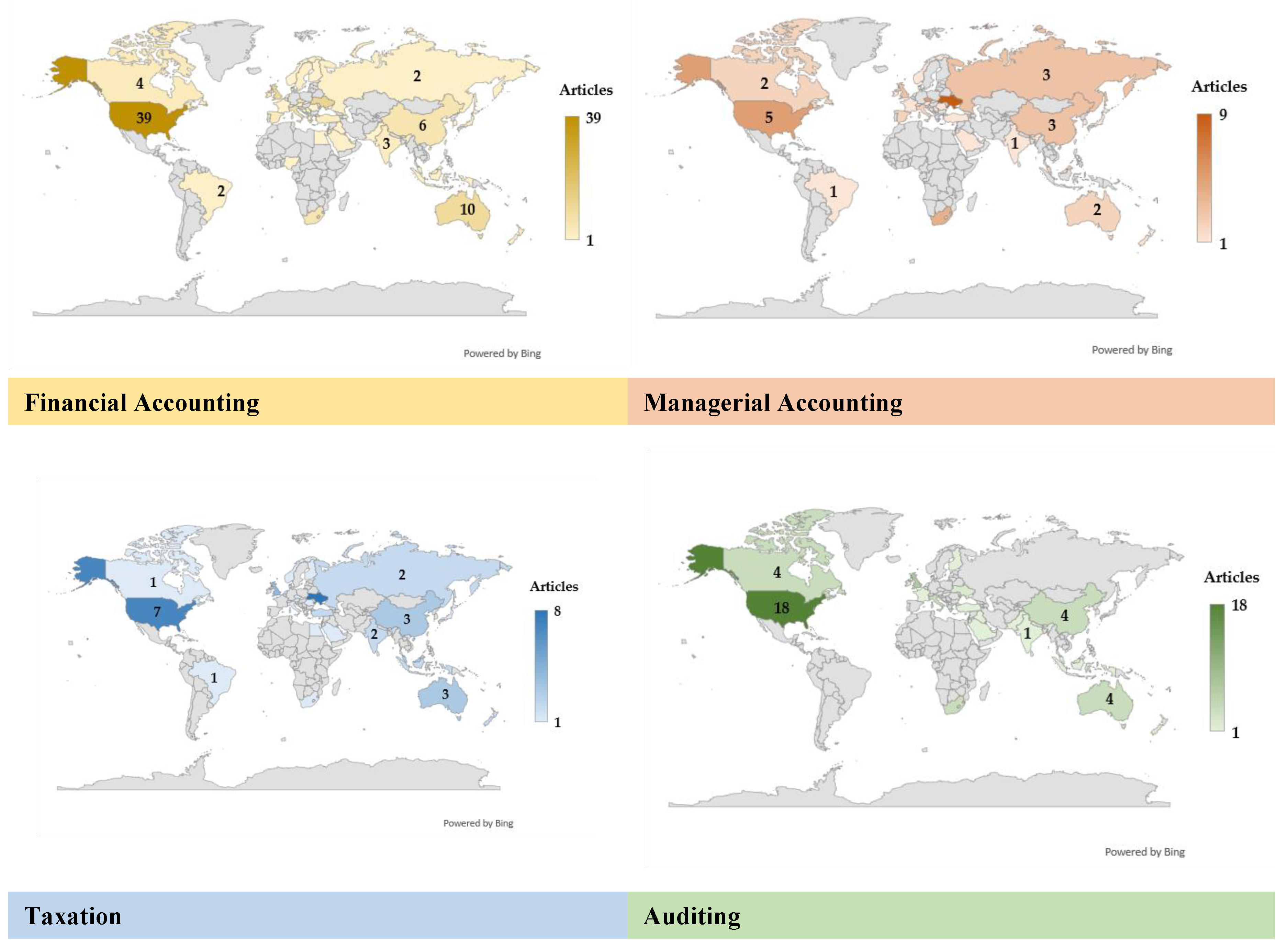

3.3. Countries Scientific Production and Citation Analysis

- The first cluster contains the Czech Republic (six articles, five total link power), Indonesia (two articles, two total link power), Italy (seven documents, 54 total link power), Russia (three documents, seven total link power), and South Africa (six articles, eight total link power), which added their contribution to the research topic between 2019-2020;

- The second network formed by a central node, the USA (41 documents, 91 total link power), indicating a significant role in international research, India (two articles, one total link power), Malaysia (three articles, two total link power), and South Korea (one article, one total link power), with articles released around 2020;

- The third cluster shows the interconnection between China (four manuscripts, 34 total link power), Singapore (one document, two total link power), and Taiwan (one item, four total link power), which added its contribution recently, between 2021-2023;

- The fourth network contains the United Kingdom as a central node because it released 12 documents, with a total link strength of 18. It is followed by Australia (nine articles, 31 total link power) and Spain (four documents, seven total link power), which contributed between 2021-2022;

- The fifth interconnection was created between the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (one article released, five total link strength), Canada (five documents, 22 total link power), and Turkey (three documents, 13 total link power), which added its contribution around the year 2022;

- France (three articles, seven total link power) and Japan (three documents, three total link power) form the sixth couple, being active between 2020 – 2021;

- In the seventh cluster we can remark Ukraine (14 articles, seven total link power) and Lithuania (one article, one total link power), with published articles between 2021-2022.

3.4. Authors Network and Productivity

3.5. Citations at Institutions Level

4. Bibliometric Analyses of the Topics Researched

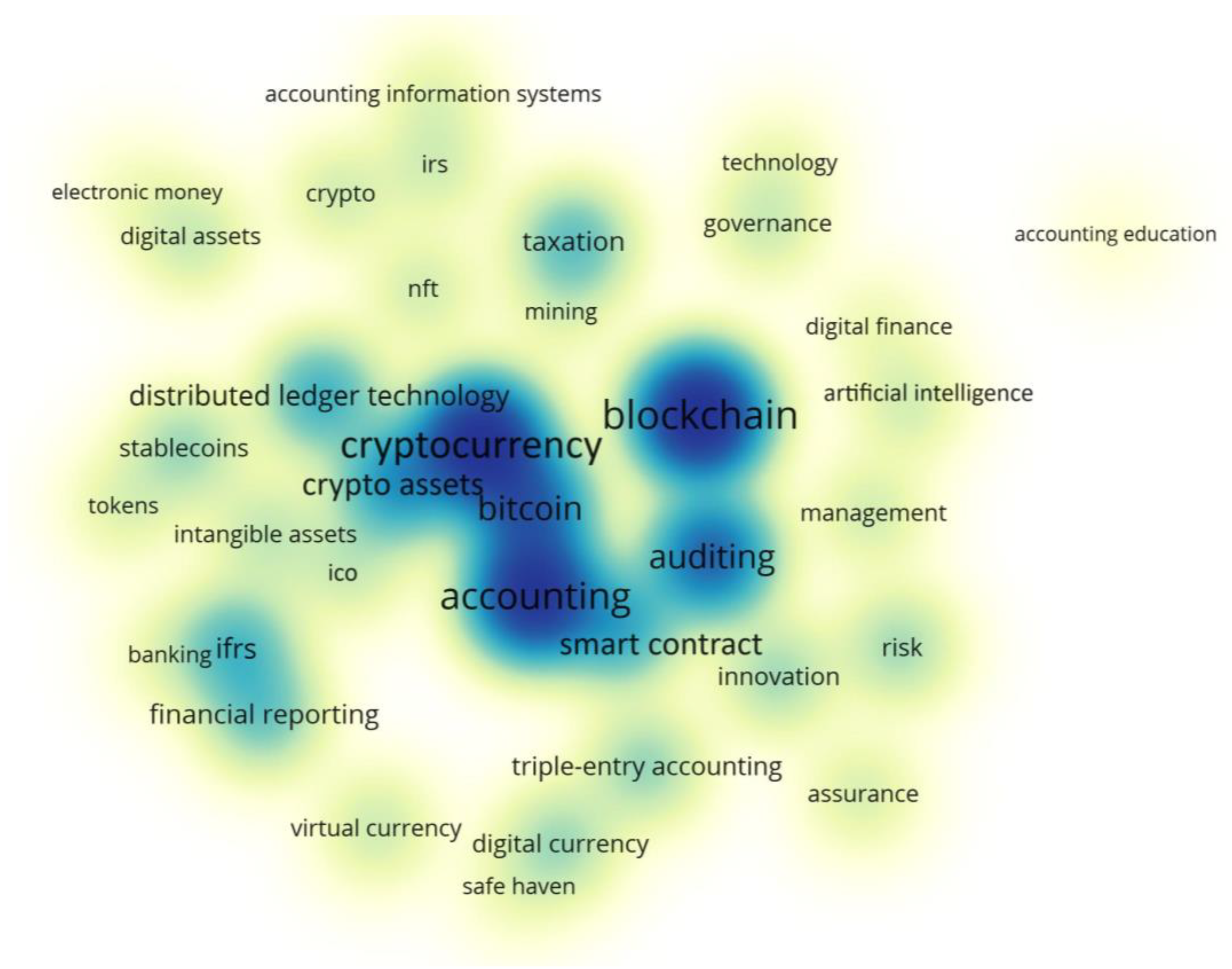

4.1. Keywords Co-occurrence Analysis

4.2. Thematic Analysis

4.3. Results and Discussions

4.3.1. Insights on Financial Accounting Regarding Cryptocurrencies

- A key distinction emerges when examining how US and international companies account for cryptocurrencies. According to Luo and Yu (2022), US companies typically rely on the cost method for cryptocurrencies categorized as intangible assets. This approach reflects any decrease in value as impairment losses. In contrast, international companies following IFRS often utilize the fair value method, as evidenced by Morozova et al. (2020) and Niftaliyev (2023). This method emphasizes the current market value of the cryptocurrency, providing a more dynamic picture. However, Vasicek, Dmitrovic, and Cicak (2019) identify a fundamental mismatch between cryptocurrencies and current IFRS accounting regulations. While fair value through profit or loss (FVTPL) might appear to be a logical valuation approach, it is not permitted under IFRS (Ramassa and Leoni 2022; Vasicek, Dmitrovic, and Cicak 2019). IFRS (2019) offers some guidance, recommending classification as either inventory or long-term intangible asset, but the initial valuation is based on the acquisition cost. This approach may not reflect the nature of cryptocurrency prices (Vodáková and Foltyn 2020b).

- Raiborn and Sivitanides (2015) delve into the debate over valuation methods, proposing two main options: fair value accounting, potentially applicable for short-term and long-term investments in cryptocurrencies, or the historical cost for long-term investments.

- 3.

- Gomaa, Gomaa, and Stampone (2019) examine a scenario where an accounting consulting service is paid for using cryptocurrency, understanding them as a legitimate form of payment. Rella (2020) would recognize them as money, “turning them into monetary commodities”. Yee, Heong, and Chin (2020) emphasize the potential of fair value measurement when cryptocurrencies are received as payment.

- 4.

- Procházka (2018; 2019) argues for fair value accounting for crypto investments and highlights scenarios where cryptocurrencies can be treated as cash or foreign currency (even if not legal tender), imagining scenarios like receiving crypto as payment (Rella 2020). He also explores how crypto might be used for hedging or derivative contracts under IFRS 9 and suggests treating it as a non-financial investment.

4.3.2. Insights on Managerial Accounting Regarding Cryptocurrencies

4.3.3. Insights on Taxation of Cryptocurrencies

4.3.4. Insights on Auditing of Cryptocurrencies

5. Conclusions

- How does pseudonymity interact with regulation regarding cryptocurrency holdings?

- How can the financial reporting of cryptocurrencies comply with the existing standards, or can we explore whether new standards are necessary?

- Which valuation approach is more effective for measuring cryptocurrency value over time?

- Which tax regulations would be appropriate for mining, trading, or staking activities with cryptocurrencies?

- Development of audit methodologies designed explicitly for crypto assets.

- The application of blockchain technology and triple-entry accounting in auditing and accounting of crypto assets.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- (Abdennadher et al. 2022) Abdennadher, S., R. Grassa, H. Abdulla, and A. Alfalasi. 2022. “The Effects of Blockchain Technology on the Accounting and Assurance Profession in the UAE: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 20 (1): 53–71. [CrossRef]

- (Adams and Bailey 2021) Adams, M.T., and W.A. Bailey. 2021. “Emerging Cryptocurrencies and IRS Summons Power: Striking the Proper Balance between IRS Audit Authority and Taxpayer Privacy.” The ATA Journal of Legal Tax Research 19 (1): 61–81. [CrossRef]

- (Adelowotan and Coetsee 2021) Adelowotan, M., and D. Coetsee. 2021. “Blockchain Technology And Implications For Accounting Practice.” Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal. Allied Business Academies.

- (Alamad 2019) Alamad, S. 2019. “Financial and Accounting Principles in Islamic Finance.” Financial and Accounting Principles in Islamic Finance. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- (Albizri and Appelbaum 2021) Albizri, Abdullah, and Deniz Appelbaum. 2021. “Trust but Verify: The Oracle Paradox of Blockchain Smart Contracts.” Journal of Information Systems 35 (2): 1–16. [CrossRef]

- (Alhasana and Alrowwad 2022) Alhasana, KAH, and AMM Alrowwad. 2022. “National Standards of Accounting and Reporting in the Era of Digitalization of the Economy.” Financial and Credit Activity: Problems of Theory and Practice. Fintech Aliance LLC. [CrossRef]

- (Al-Htaybat, Hutaibat and von Alberti-Alhtaybat 2019) Al-Htaybat, K., K. Hutaibat, and L. von Alberti-Alhtaybat. 2019. “Global Brain-Reflective Accounting Practices Forms of Intellectual Capital Contributing to Value Creation and Sustainable Development.” Journal of Intellectual Capital. Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley Bd16 1wa, W Yorkshire, England: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (Alles and Gray 2020) Alles, M., and G.L. Gray. 2020. “What Accountants Need to Know about Blockchain.” Information For Efficient Decision Making: Big Data, Blockchain And Relevance. World Scientific Publishing Co. [CrossRef]

- (Alles and Gray 2023) Alles, M., and G.L. Gray. 2023. “Hope or Hype? Blockchain and Accounting.” International Journal of Digital Accounting Research. Universidad de Huelva. [CrossRef]

- (Alsalmi, Ullah and Rafique 2023) Alsalmi, N., S. Ullah, and M. Rafique. 2023. “Accounting for Digital Currencies.” Research in International Business and Finance 64. [CrossRef]

- (ALSaqa, Hussein and Mahmood 2019) ALSaqa, ZH, AI Hussein, and SM Mahmood. 2019. “The Impact of Blockchain on Accounting Information Systems.” Journal of Information Technology Management. University of Tehran. [CrossRef]

- (Altukhov, Nozhkina and Dushevina 2020) Altukhov, PL, EB Nozhkina, and EM Dushevina. 2020. “Process Approach to the Creation of Intellectual-Information Management System of Industrial Enterprise Development.” edited by DB Solovev, 128:1758–65.

- (Al-Wreikat, Almasarwah and Al-Sheyab 2023) Al-Wreikat, A., A. Almasarwah, and O. Al-Sheyab. 2023. “Blockchain Technology, Cryptocurrencies and Transforming Accounting Fees.” International Journal of Electronic Business 19 (1): 95–122. [CrossRef]

- (Ammous 2018) Ammous, S. 2018. “Can Cryptocurrencies Fulfil the Functions of Money?” Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance. Ste 800, 230 Park Ave, New York, NY 10169 USA: Elsevier Science Inc. [CrossRef]

- (Angeline et al. 2021) Angeline, YKH, WS Chin, TT Tenk, and Z Saleh. 2021. “Accounting Treatments for Cryptocurrencies in Malaysia: The Hierarchical Component Model Approach.” Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 14 (2): 137–71. [CrossRef]

- (Appelbaum et al. 2022) Appelbaum, D., E. Cohen, E. Kinory, and S.S. Smith. 2022. “Impediments to Blockchain Adoption.” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 19 (2): 199–210. [CrossRef]

- (Appelbaum and Nehmer 2020) Appelbaum, D., and R.A. Nehmer. 2020. “Auditing Cloud-Based Blockchain Accounting Systems.” Journal of Information Systems. 9009 Town Center Parkway, Lakewood Ranch, FL, United States: Amer Accounting Assoc. [CrossRef]

- (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017) Aria, M., and C. Cuccurullo. 2017. “bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis.” Journal of Inometrics (11(4)): 959-975. Accessed 2024. https://www.bibliometrix.org/home/.

- (Atik and Kelten 2021) Atik, A., and GS Kelten. 2021. “Blockchain Technology and Its Potential Effects on Accounting: A Systematic Literature Review.” Istanbul Business Research. Istanbul Univ, Sch Business, Istanbul, 34322, Turkey: Istanbul Univ, Sch Business. [CrossRef]

- (Barros, Bertolai and Carrijo 2023) Barros, F, J Bertolai, and M Carrijo. 2023. “Cryptocurrency Is Accounting Coordination: Selfish Mining and Double Spending in a Simple Mining Game?” Mathematical Social Sciences 123 (May): 25–50. [CrossRef]

- (Baur, Hong and Lee 2018) Baur, D.G., K. Hong, and A.D. Lee. 2018. “Bitcoin: Medium of Exchange or Speculative Assets?” Journal of International Financial Markets Institutions & Money. Po Box 211, 1000 Ae Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science Bv. [CrossRef]

- (Bauer et al. 2023) Bauer, Tim D., J. Efrim Boritz, Krista Fiolleau, Bradley Pomeroy, Adam Vitalis, and Pei Wang. 2023. “Cataloging the Marketplace of Assurance Services.” Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, November, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- (Beigman et al. 2023) Beigman, E., G. Brennan, S.-F. Hsieh, and A.J. Sannella. 2023. “Dynamic Principal Market Determination: Fair Value Measurement of Cryptocurrency.” Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance 38 (4): 731–48. [CrossRef]

- (Belluci, Bianchi and Manneti 2022) Bellucci, M., D. Cesa Bianchi, and G. Manetti. 2022. “Blockchain in Accounting Practice and Research: Systematic Literature Review.” Meditari Accountancy Research 30 (7): 121–46. [CrossRef]

- (Bennett et al. 2020) Bennett, S., K. Charbonneau, R. Leopold, L. Mezon, C. Paradine, A. Scilipoti, and R. Villmann. 2020. “Blockchain and Cryptoassets: Insights from Practice*.” Accounting Perspectives. Canadian Academic Accounting Association. [CrossRef]

- (Blahušiaková 2022) Blahušiaková, M. 2022. “Accounting for Holdings of Cryptocurrencies in the Slovak Republic: Comparative Analysis.” Contemporary Economics 16 (1): 16–31. [CrossRef]

- (Bohme et al. 2015) Boehme, R., N. Christin, B. Edelman, and T. Moore. 2015. “Bitcoin: Economics, Technology, and Governance.” Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2014 Broadway, Ste 305, Nashville, TN 37203 USA: Amer Economic Assoc. [CrossRef]

- (Bondarenko, Kichuk and Antonov 2019) Bondarenko, O., O. Kichuk, and A. Antonov. 2019. “The Possibilities of Using Investment Tools Based on Cryptocurrency in the Development of the National Economy.” Baltic Journal of Economic Studies. Valdeku Iela 62-156, Riga, Lv-1058, Latvia: Baltic Journal Economic Studies. [CrossRef]

- (Bonyuet 2020) Bonyuet, D. 2020. “Overview and Impact of Blockchain on Auditing.” International Journal of Digital Accounting Research 20: 31–43. [CrossRef]

- (Borri 2019) Borri, N. 2019. “Conditional Tail-Risk in Cryptocurrency Markets.” Journal of Empirical Finance. Po Box 211, 1000 AE Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science Bv. [CrossRef]

- (Borri and Shakhnov 2022) Borri, N., and K. Shakhnov. 2022. “The Cross-Section of Cryptocurrency Returns.” Review of Asset Pricing Studies. Great Clarendon St, Oxford OX2 6dp, England: Oxford Univ Press. [CrossRef]

- (Borthick and Pennington 2017) Borthick, A. Faye, and Robin R. Pennington. 2017. “When Data Become Ubiquitous, What Becomes of Accounting and Assurance?” Journal of Information Systems 31 (3): 1–4. [CrossRef]

- (Bouri et al. 2017) Bouri, E., N. Jalkh, P. Molnar, and D. Roubaud. 2017. “Bitcoin for Energy Commodities before and after the December 2013 Crash: Diversifier, Hedge or Safe Haven?” Applied Economics. 2-4 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon OX14 4rn, Oxon, England: Routledge Journals, Taylor & Francis Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (Bourveau et al. 2022) Bourveau, T., E.T. De George, A. Ellahie, and D. Macciocchi. 2022. “The Role of Disclosure and Information Intermediaries in an Unregulated Capital Market: Evidence from Initial Coin Offerings.” Journal of Accounting Research 60 (1): 129–67. [CrossRef]

- (Bozdoğanoğlu 2022) Bozdoğanoğlu, B. 2022. “Evaluation of the Effects of Technology Literacy and Digital Financial Literacy on the Investment and Taxation Process in Crypto Assets.” Current Issues and Empirical Studies in Public Finance. Peter Lang AG. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85138957012&partnerID=40&md5=5eaf96405cfa6b1f821d82dae2bc58e5.

- (Bunget and Trifa 2023) Bunget, Ovidiu Constantin, and Georgiana Iulia Trifa. 2023. “Cryptoassets – Perspectives of Accountancy Recognition in the Technological Era.” Audit Financiar 21 (171): 526–51. [CrossRef]

- (Bunget and Lungu 2023) Bunget, Ovidiu-Constantin, and Cristian Lungu. 2023. “A Bibliometric Analysis of the Implications of Artificial Intelligence on the Accounting Profession.” CECCAR Business Review 4 (5): 65–72. [CrossRef]

- (Buhussain and Hamdan 2023) Buhussain, G., and A. Hamdan. 2023. “Blockchain Technology and Audit Profession.” In Contrib. Manag. Sci., Part F1640:715–24. Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. [CrossRef]

- (Caliskan 2020) Caliskan, K. 2020. “Data Money: The Socio-Technical Infrastructure of Cryptocurrency Blockchains.” Economy And Society. 2-4 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon OX14 4rn, Oxon, England: Routledge Journals, Taylor & Francis Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (Casey and Vigna 2018) Casey, Michael, and Paul Vigna. 2018. The Truth Machine: The Blockchain and the Future of Everything. First edition. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- (Cassidy et al. 2020) Cassidy, J., MHA Cheng, T. Le, and E. Huang. 2020. “A Toss of a (Bit)Coin: The Uncertain Nature of the Legal Status of Cryptocurrencies.” eJournal of Tax Research. University of New South Wales.

- (Chiu et al. 2022) Chiu, Tiffany, Victoria Chiu, Tawei Wang, and Yunsen Wang. 2022. “Using Textual Analysis to Detect Initial Coin Offering Frauds.” Journal of Forensic Accounting Research 7 (1): 165–83. [CrossRef]

- (Chou et al. 2021) Chou, CC, NCR Hwang, GP Schneider, T Wang, CW Li, and W Wei. 2021. “Using Smart Contracts to Establish Decentralized Accounting Contracts: An Example of Revenue Recognition.” Journal of Information Systems 35 (3): 17–52. [CrossRef]

- (Chou, Agrawal and Birt 2022) Chou, JH, P. Agrawal, and J. Birt. 2022. “Accounting for Crypto-Assets: Stakeholders’ Perceptions.” Studies in Economics and Finance. Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley Bd16 1WA, W Yorkshire, England: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (Church, Smith and Kinory 2021) Church, K.S., S.S. Smith, and E. Kinory. 2021. “Accounting Implications of Blockchain: A Hyperledger Composer Use Case for Intangible Assets.” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 18 (2): 23–52. [CrossRef]

- (Cong et al. 2023) Cong, LW, W Landsman, E Maydew, and D Rabetti. 2023. “Tax-Loss Harvesting with Cryptocurrencies.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 76 (2–3): 101607. [CrossRef]

- (Corbet, Urquhart and Yarovaya 2020) Corbet, S., A. Urquhart, and L. Yarovaya. 2020. Cryptocurrency and Blockchain Technology. Cryptocurrency and Blockchain Technol. Cryptocurrency and Blockchain Technology. De Gruyter. [CrossRef]

- (Coyne and McMickle 2017) Coyne, JG, and PL McMickle. 2017. “Can Blockchains Serve an Accounting Purpose?” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 14 (2): 101–11. [CrossRef]

- (Cyrus 2023) Cyrus, R. 2023. “Custody, Provenance, and Reporting of Blockchain and Cryptoassets.” The Emerald Handbook on Cryptoassets: Investment Opportunities and Challenges. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (Dai, He and Yu 2019) Dai, J, N He, and H Yu. 2019. “Utilizing Blockchain and Smart Contracts to Enable Audit 4.0: From the Perspective of Accountability Audit of Air Pollution Control in China.” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 16 (2): 23–41. [CrossRef]

- (Dai and Vasarhelyi 2017) Dai, J, and MA Vasarhelyi. 2017. “Toward Blockchain-Based Accounting and Assurance.” Journal of Information Systems 31 (3): 5–21. [CrossRef]

- (Davenport and Usrey 2023) Davenport, S.A., and SC. Usrey. 2023. “Crypto Assets: Examining Possible Tax Classifications.” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 20 (2): 55–70. [CrossRef]

- (Derun and Mysaka 2022) Derun, I, and H Mysaka. 2022. “Digital Assets in Accounting: The Concept Formation and the Further Development Trajectory.” Economic Annals-XXI 195 (1–2): 59–70. [CrossRef]

- (Desai 2023) Desai, H. 2023. “Infusing Blockchain in Accounting Curricula and Practice: Expectations, Challenges, and Strategies.” International Journal of Digital Accounting Research. Universidad de Huelva. [CrossRef]

- (DeVries 2016) DeVries, Peter D. 2016. “An Analysis of Cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, and the Future.” International Journal of Business Management and Commerce 1 (2): 1–9.

- (Dunn, Jenkins and Sheldon 2021) Dunn, R.T., J.G. Jenkins, and M.D. Sheldon. 2021. “Bitcoin and Blockchain: Audit Implications of the Killer Bs.” Issues in Accounting Education 36 (1): 43–56. [CrossRef]

- (Dyball and Seethamraju 2021) Dyball, M.C., and R. Seethamraju. 2022. “Client Use of Blockchain Technology: Exploring Its (Potential) Impact on Financial Statement Audits of Australian Accounting Firms.” Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 35 (7): 1656–84. [CrossRef]

- (Fomina et al. 2019) Fomina, O., O. Moshkovska, O. Avhustova, O. Romashko, and D. Holovina. 2019. “Current Aspects of the Cryptocurrency Recognition in Ukraine.” Banks and Bank Systems 14 (2): 203–13. [CrossRef]

- (Fuller and Markelevich 2020) Fuller, SH, and A. Markelevich. 2020. “Should Accountants Care about Blockchain?” Journal of Corporate Accounting and Finance 31 (2): 34–46. [CrossRef]

- (Gan, Tsoukalas and Netessine 2021) Gan, J., G. Tsoukalas, and S. Netessine. 2021. “Initial Coin Offerings, Speculation, and Asset Tokenization.” Management Science. INFORMS Inst. for Operations Res. and the Management Sciences. [CrossRef]

- (Gao 2023) Gao, X. 2023. “Digital Transformation in Finance and Its Role in Promoting Financial Transparency.” GLOBAL FINANCE JOURNAL. RADARWEG 29, 1043 NX AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS: ELSEVIER. [CrossRef]

- (Garanina, Ranta and Dumay 2022) Garanina, T., M. Ranta, and J. Dumay. 2022. “Blockchain in Accounting Research: Current Trends and Emerging Topics.” Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal. Emerald Group Holdings Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (García-Monleón, Erdmann and Arilla 2023) García-Monleón, F., A. Erdmann, and R. Arilla. 2023. “A Value-Based Approach to the Adoption of Cryptocurrencies.” Journal of Innovation and Knowledge 8 (2). [CrossRef]

- (Gietzmann and Grossetti 2021) Gietzmann, M, and F Grossetti. 2021. “Blockchain and Other Distributed Ledger Technologies: Where Is the Accounting?” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 40 (5). [CrossRef]

- (Gomaa, Gomaa and Stampone 2019) Gomaa, A.A., M.I. Gomaa, and A. Stampone. 2019. “A Transaction on the Blockchain: An AIS Perspective, Intro Case to Explain Transactions on the ERP and the Role of the Internal and External Auditor.” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 16 (1): 47–64. [CrossRef]

- (Guo et al. 2021) Guo, Feng, Stephanie Walton, Patrick R. Wheeler, and Yiyang (Ian) Zhang. 2021. “Early Disruptors: Examining the Determinants and Consequences of Blockchain Early Adoption.” Journal of Information Systems 35 (2): 219–42. [CrossRef]

- (Gurdgiev and Fleming 2021) Gurdgiev, C., and A. Fleming. 2021. “Informational Efficiency and Cybersecurity: Systemic Threats to Blockchain Applications.” Innovations in Social Finance: Transitioning Beyond Economic Value. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- (Hampl and Gyönyörová 2021) Hampl, F, and L Gyönyörová. 2021. “Can Fiat-Backed Stablecoins Be Considered Cash or Cash Equivalents Under International Financial Reporting Standards Rules?” Australian Accounting Review 31 (3): 233–55. [CrossRef]

- (Han et al 2023) Han, H., RK. Shiwakoti, R. Jarvis, C. Mordi, and D. Botchie. 2023. “Accounting and Auditing with Blockchain Technology and Artificial Intelligence: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Accounting Information Systems. Radarweg 29, 1043 NX Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- (Handoko, Gunawan and Djati 2022) Handoko, BL, BA Gunawan, MFP Djati, and ACM. 2022. “Importance Of Blockchain Within The Big 4 CPA Firms: Cryptocurrency’s Existence.” In Universitas Bina Nusantara, 190–96. [CrossRef]

- (Harrast, McGilsky and Sun 2022) Harrast, S.A., D. McGilsky, and Y. Sun. 2022. “Determining the Inherent Risks of Cryptocurrency: A Survey Analysis.” Current Issues in Auditing 16 (2): A10–17. [CrossRef]

- (Hazar 2020) Hazar, H.B. 2020. “Anonymity in Cryptocurrencies.” Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics 14 (1): 171–78. [CrossRef]

- (Holub and Johnson 2018) Holub, M., and J. Johnson. 2018. “Bitcoin Research across Disciplines.” Information Society 34 (2): 114–26. [CrossRef]

- (Huang, Deng and Chan 2023) Huang, R.H., H. Deng, and A.F.L. Chan. 2023. “The Legal Nature of Cryptocurrency as Property: Accounting and Taxation Implications.” Computer Law and Security Review 51. [CrossRef]

- (Hubbard 2023) Hubbard, B. 2023. “Decrypting Crypto: Implications of Potential Financial Accounting Treatments of Cryptocurrency.” Accounting Research Journal 36 (4–5): 369–83. [CrossRef]

- (IFRS 2019) IFRS Foundation. (2019). Holding of Cryptocurrencies. https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/meetings/2019/june/ifric/ap12-holdings-of-cryptocurrencies.pdf.

- (IAS 16) IFRS Foundation. 2024. IAS 16 Property, Plant and Equipment. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-16-property-plant-and-equipment/.

- (IAS 2) IFRS Foundation. 2024. IAS 2 Inventories. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-2-inventories/.

- (IAS 32) IFRS Foundation. 2024. IAS 32 Financial Instruments: Presentation. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-32-financial-instruments-presentation/.

- (IAS 38) IFRS Foundation. 2024. IAS 38 Intangible Assets. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-38-intangible-assets/.

- (IAS 39) IFRS Foundation. 2024. IAS 39 Financial Instruments: Recognition and Measurement. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-39-financial-instruments-recognition-and-measurement/.

- (IAS 40) IFRS Foundation. 2024. IAS 40 Investment Property. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-40-investment-property/.

- (IAS 7) IFRS Foundation. 2024. IAS 7 Statement of Cash Flows. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-7-statement-of-cash-flows/.

- (IAS 8) IFRS Foundation. 2024. IAS 8 Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-8-accounting-policies-changes-in-accounting-estimates-and-errors/.

- (IFRS 13) IFRS Foundation. 2024. IFRS 13 Fair Value Measurement. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ifrs-13-fair-value-measurement/.

- (IFRS 5) IFRS Foundation. 2024. IFRS 5 Non-current Assets Held for Sale and Discontinued Operations. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ifrs-5-non-current-assets-held-for-sale-and-discontinued-operations/.

- (IFRS 9) IFRS Foundation. 2024. IFRS 9 Financial Instruments. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ifrs-9-financial-instruments/.

- (Ilham et al. 2019a) Ilham, RN, EKA Fachrudin, AS Silalahi, and J Saputra. 2019. “Comparative of the Supply Chain and Block Chains to Increase the Country Revenues via Virtual Tax Transactions and Replacing Future of Money.” International Journal of Supply Chain Management. ExcelingTech.

- (Ilham et al. 2019b) Ilham, RN, EKA Fachrudin, AS Silalahi, J Saputra, and W Albra. 2019. “Investigation of the Bitcoin Effects on the Country Revenues via Virtual Tax Transactions for Purchasing Management.” International Journal of Supply Chain Management. ExcelingTech.

- (Jackson and Luu 2023) Jackson, AB, and S Luu. 2023. “Accounting For Digital Assets.” Australian Accounting Review 33 (3): 302–12. [CrossRef]

- (Jayasuriya and Sims 2023) Jayasuriya, DD, and A Sims. 2023. “From the Abacus to Enterprise Resource Planning: Is Blockchain the Next Big Accounting Tool?” Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal 36 (1): 24–62. [CrossRef]

- (Jeong and Lim 2023) Jeong, Anna Y., and Jee-Hae Lim. 2023. “The Impact of Blockchain Technology Adoption Announcements on Firm’s Market Value.” Journal of Information Systems 37 (1): 39–65. [CrossRef]

- (Jumde and Cho 2020) Jumde, A., and BY Cho. 2020. “Can Cryptocurrencies Overtake the Fiat Money?” International Journal of Business Performance Management. Inderscience Publishers. [CrossRef]

- (Juškaitė and Gudelytė-Žilinskienė 2022) Juškaitė, L., and L. Gudelytė-Žilinskienė. 2022. “Investigation of the Feasibility of Including Different Cryptocurrencies in the Investment Portfolio for its Diversification.” Business, Management and Economics Engineering. Vilnius Gediminas Technical University. [CrossRef]

- (Kaden, Lingwall and Shonhiwa 2021) Kaden, SR., JW. Lingwall, and TT. Shonhiwa. 2021. “Teaching Blockchain through Coding: Educating the Future Accounting Professional.” Issues in Accounting Education 36 (4): 281–90. [CrossRef]

- (Kampakis 2022) Kampakis, S. 2022. “Auditing Tokenomics: A Case Study and Lessons from Auditing a Stablecoin Project.” Journal of the British Blockchain Association 5 (2). [CrossRef]

- (Klopper and Brink 2023) Klopper, N., and S.M. Brink. 2023. “Determining the Appropriate Accounting Treatment of Cryptocurrencies Based on Accounting Theory.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16 (9). [CrossRef]

- (Kochergin 2020) Kochergin, D.A. 2020. “Economic Nature and Classification of Stablecoins.” Finance: Theory and Practice. Financial University under The Government of Russian Federation. [CrossRef]

- (Koker and Koutmos 2020) Koker, TE., and D. Koutmos. 2020. “Cryptocurrency Trading Using Machine Learning.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- (Kokina, Mancha and Pachamanova 2017) Kokina, J., R. Mancha, and D. Pachamanova. 2017. “Blockchain: Emergent Industry Adoption and Implications for Accounting.” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 14 (2): 91–100. [CrossRef]

- (Kolková 2018) Kolková, A. 2018. “The Use of Cryptocurrency in Enterprises in Czech Republic.” In Technical University of Ostrava, edited by O Dvoulety, M Lukes, and J Misar, 541–52.

- (Kontozis 2019) Kontozis, Nikolas. 2019. “VAT Treatment of Cryptocurrencies.” PwC, 2019. https://www.pwc.com.cy/en/press-room/articles-2019/vat-treatment-of-cryptocurrencies.html.

- (Lardo et al. 2022) Lardo, Alessandra, Katia Corsi, Ashish Varma, and Daniela Mancini. 2022. “Exploring Blockchain in the Accounting Domain: A Bibliometric Analysis.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 35 (9): 204–33. [CrossRef]

- (Lee, Appelbaum and Mautz 2022) Lee, LS, D Appelbaum, and RDM Mautz. 2022. “Blockchains: An Experiential Accounting Learning Activity.” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 19 (1): 181–97. [CrossRef]

- (Lombardi et al. 2022) Lombardi, R., C. de Villiers, N. Moscariello, and M. Pizzo. 2022. “The Disruption of Blockchain in Auditing – a Systematic Literature Review and an Agenda for Future Research.” Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 35 (7): 1534–65. [CrossRef]

- (Luo and Yu 2022) Luo, M., and S. Yu. 2022. “Financial Reporting for Cryptocurrency.” Review of Accounting Studies. [CrossRef]

- (Maffei, Casciello and Meucci 2021) Maffei, M., R. Casciello, and F. Meucci. 2021. “Blockchain Technology: Uninvestigated Issues Emerging from an Integrated View within Accounting and Auditing Practices.” Journal of Organizational Change Management. Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley Bd16 1WA, W Yorkshire, England: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (Makurin 2023) Makurin, A. 2023. “Technological Aspects and Environmental Consequences of Mining Encryption.” Economics Ecology Socium 7 (1): 61–70. [CrossRef]

- (Makurin et al. 2023) Makurin, A, A Maliienko, O Tryfonova, and L Masina. 2023. “Management of Cryptocurrency Transactions from Accounting Aspects.” Economics Ecology Socium 7 (3): 26–35. [CrossRef]

- (Matusky 2017) Matusky, T. 2017. “Accounting of Cryptocurrencies.” In University of Economics Bratislava, edited by J Wallner, 313–21.

- (McCallig, Robb and Rohde 2019) McCallig, J., A. Robb, and F. Rohde. 2019. “Establishing the Representational Faithfulness of Financial Accounting Information Using Multiparty Security, Network Analysis and a Blockchain.” International Journal of Accounting Information Systems. Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accinf.2019.03.004. [CrossRef]

- (McGuigan, Ghio and Kern 2021) McGuigan, N., A. Ghio, and T. Kern. 2021. “Designing Accounting Futures: Exploring Ambiguity in Accounting Classrooms through Design Futuring.” Issues in Accounting Education 36 (4): 325–51. [CrossRef]

- (Moore 2017) Moore, Louella. 2017. “Carving Nature at Its Joints: The Entity Concept in an Entangled Society.” Accounting Historians Journal 44 (2): 125–38. [CrossRef]

- (Morozova et al. 2020) Morozova, T., R. Akhmadeev, L. Lehoux, A. Yumashev, G. Meshkova, and M. Lukiyanova. 2020. “Crypto Asset Assessment Models in Financial Reporting Content Typologies.” Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 7 (3): 2196–2212. [CrossRef]

- (Mosteanu and Faccia 2020) Mosteanu, NR, and A. Faccia. 2020. “Digital Systems and New Challenges of Financial Management - FinTech, XBRL, Blockchain and Cryptocurrencies.” Quality-Access to Success. Str Vasile Parvan Nr 14, Sector 1, Postal Code 010 216, Bucharest, 00000, Romania: Soc Romana Pentru Asigurarea Calitatii.

- (Munteanu et al. 2023) Munteanu, I., K-A. Aivaz, A. Micu, A. Capatana, and V. Jakubowicz. 2023. “Digital Transformations Imprint Financial Challenges: Accounting Assessment Of Crypto Assets And Building Resilience In Emerging Innovative Businesses.” Economic Computation And Economic Cybernetics Studies And Research. Piata Romana, Nr 6, Sector 1, Bucuresti, 701731, Romania: Editura ASE.

- (Nakamoto 2009) Nakamoto, Satoshi. 2009. “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.” https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf.

- (Niftaliyev 2023) Niftaliyev, S.G. 2023. “Problems Arising in the Accounting of Cryptocurrencies.” Financial and Credit Activity: Problems of Theory and Practice 3 (50): 76–86. [CrossRef]

- (Ntanos et al. 2020) Ntanos, S., S. Asonitou, D. Karydas, and G. Kyriakopoulos. 2020. “Blockchain Technology: A Case Study from Greek Accountants.” Edited by Kavoura A, Kefallonitis E, and Theodoridis P. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer Science and Business Media B.V. [CrossRef]

- (Nylen and Huels 2022) Nylen, PC., and BW. Huels. 2022. “Using Unrelated IRS Guidance as a Framework for Taxing Crypto Transactions: Revenue Procedure 2019-18.” The ATA Journal of Legal Tax Research 20 (1): 30–46. [CrossRef]

- (Obu and Ukpere 2022) Obu, OC, and WI. Ukpere. 2022. “The Implications of the Incursion of Cryptocurrency on the Effectiveness of Fiscal Policy.” Review of Applied Socio-Economic Research. Pro Global Science Association. [CrossRef]

- (O’Leary 2018) O’Leary, D.E. 2018. “Open Information Enterprise Transactions: Business Intelligence and Wash and Spoof Transactions in Blockchain and Social Commerce.” Intelligent Systems in Accounting, Finance and Management 25 (3): 148–58. [CrossRef]

- (Ozeran and Gura 2020) Ozeran, A, and N Gura. 2020. “Audit and Accounting Considerations on Cryptoassets and Related Transactions.” Economic Annals-XXI 184 (7–8): 124–32. [CrossRef]

- (Ozili 2023) Ozili, PK. 2023. “CBDC, Fintech and Cryptocurrency for Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability.” Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance. Emerald Publishing. [CrossRef]

- (Pan, Vaughan and Wright 2023) Pan, L., O. Vaughan, and C.S. Wright. 2023. “A Private and Efficient Triple-Entry Accounting Protocol on Bitcoin.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16 (9). [CrossRef]

- (Pandey and Gilmour 2024) Pandey, D., and P. Gilmour. 2024. “Accounting Meets Metaverse: Navigating the Intersection between the Real and Virtual Worlds.” Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. Floor 5, Northspring 21-23 Wellington Street, Leeds, W Yorkshire, England: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (Pantielieieva et al. 2019) Pantielieieva, N. M., N. Rogova V, S. M. Braichenko, S. Dzholos V, and A. S. Kolisnyk. 2019. “Current Aspects of Transformation of Economic Relations: Cryptocurrencies and Their Legal Regulation.” Financial and Credit Activity-Problems of Theory and Practice. Pr-Kt Peremohy, 55, Kharkiv, 61174, Ukraine: Natl Bank Ukraine, Univ Banking, Kharkiv Inst Banking.

- (Papp, Almond and Zhang 2023) Papp, A., D. Almond, and S. Zhang. 2023. “Bitcoin and Carbon Dioxide Emissions: Evidence from Daily Production Decisions.” Journal of Public Economics. Po Box 564, 1001 Lausanne, Switzerland: Elsevier Science SA. [CrossRef]

- (Parrondo 2020) Parrondo, L. 2020. “DLT-Based Tokens Classification towards Accounting Regulation.” In FEMIB - Proc. Int. Conf. Financ., Econ., Manag. IT Bus., edited by Baudier P., Arami M., and Chang V., 15–26. SciTePress. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85088368491&partnerID=40&md5=8079373cce7b9633805456da0502ee83.

- (Parrondo 2023) Parrondo, L. 2023. “Cryptoassets: Definitions and Accounting Treatment under the Current International Financial Reporting Standards Framework.” Intelligent Systems in Accounting, Finance and Management. John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- (Păunescu 2018) Păunescu, M. 2018. “The Accountant’s Headache: Accounting for Virtual Currencies Transactions.” In Bucharest University of Economic Studies, 145–59.

- (Pedreño, Gelashvili and Nebreda 2021) Pedreño, EP, V Gelashvili, and LP Nebreda. 2021. “Blockchain and Its Application to Accounting.” Intangible Capital 17 (1): 1–16. [CrossRef]

- (Pelucio-Grecco, dos Santos Neto and Constancio 2020) Pelucio-Grecco, M.C., J.P. dos Santos Neto, and D. Constancio. 2020. “Accounting for Bitcoins in Light of IFRS and Tax Aspects.” Revista Contabilidade e Financas 31 (83): 275–82. [CrossRef]

- (Pflueger, Kornberger and Mouritsen 2022) Pflueger, D, M Kornberger, and J Mouritsen. 2022. “What Is Blockchain Accounting? A Critical Examination in Relation to Organizing, Governance, and Trust.” European Accounting Review, December. [CrossRef]

- (Pieters and Vivanco 2017) Pieters, G., and S. Vivanco. 2017. “Financial Regulations and Price Inconsistencies across Bitcoin Markets.” Information Economics and Policy. Radarweg 29, 1043 NX Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- (Pimentel and Boulianne 2020) Pimentel, E, and E Boulianne. 2020. “Blockchain in Accounting Research and Practice: Current Trends and Future Opportunities.” Accounting Perspectives 19 (4): 325–61. [CrossRef]

- (Pimentel et al. 2021) Pimentel, E., E. Boulianne, S. Eskandari, and J. Clark. 2021. “Systemizing the Challenges of Auditing Blockchain-Based Assets.” Journal of Information Systems 35 (2): 61–75. [CrossRef]

- (Procházka 2018) Procházka, D. 2018. “Accounting for Bitcoin and Other Cryptocurrencies under IFRS: A Comparison and Assessment of Competing Models.” International Journal of Digital Accounting Research 18: 161–88. [CrossRef]

- (Procházka 2019) Procházka, D. 2019. “Is Bitcoin a Currency or an Investment? An IFRS View.” In Springer Proc. Bus. Econ., edited by Procházka D., 217–26. Springer Science and Business Media B.V. [CrossRef]

- (Proelss, Schweizer, and Sevigny 2023) Proelss, J., D. Schweizer, and S. Sevigny. 2023. “Is Bitcoin ESG-Compliant? A Sober Look.” European Financial Management. 111 River St, Hoboken 07030-5774, NJ USA: Wiley. [CrossRef]

- (Raiborn and Sivitanides 2015) Raiborn, C, and M Sivitanides. 2015. “Accounting Issues Related to Bitcoins.” Journal of Corporate Accounting and Finance 26 (2): 25–34. [CrossRef]

- (Ram, Maroun and Garnett 2016.) Ram, A., W. Maroun, and R. Garnett. 2016. “Accounting for the Bitcoin: Accountability, Neoliberalism and a Correspondence Analysis.” Meditari Accountancy Research 24 (1): 2–35. [CrossRef]

- (Ramassa and Leoni 2022) Ramassa, P., and G. Leoni. 2022. “Standard Setting in Times of Technological Change: Accounting for Cryptocurrency Holdings.” Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 35 (7): 1598–1624. [CrossRef]

- (Rana et al. 2023) Rana, T., J. Svanberg, P. Öhman, and A. Lowe. 2023. “Introduction: Analytics in Accounting and Auditing.” In Handb. of Big Data and Analytics in Account. and Auditing, 1–13. Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- (Reepu 2019) Reepu. 2019. “Blockchain: Social Innovation in Finance & Accounting.” International Journal of Management. IAEME Publication. [CrossRef]

- (Rella 2020) Rella, L. 2020. “Steps towards an Ecology of Money Infrastructures: Materiality and Cultures of Ripple.” Journal of Cultural Economy 13 (2): 236–49. [CrossRef]

- (Salawu and Moloi 2018) Salawu, M.K., and T. Moloi. 2018. “Benefits of Legislating Cryptocurrencies: Perception of Nigerian Professional Accountants.” Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal 22 (6). https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85061856468&partnerID=40&md5=c82546d028992b4ce7a1f44284df2182.

- 148. (Sarwar et al. 2023) Sarwar, MI, K Nisar, I Khan, and D Shehzad. 2023. “Blockchains and Triple-Entry Accounting for B2B Business Models.” Ledger. 3960 Forbes Ave, Pittsburgh, PA 15260 USA: Univ Pittsburgh, Univ Library System. [CrossRef]

- (Schmitz and Leoni 2019) Schmitz, J., and G. Leoni. 2019. “Accounting and Auditing at the Time of Blockchain Technology: A Research Agenda.” Australian Accounting Review. 111 River St, Hoboken 07030-5774, NJ USA: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1111/auar.12286. [CrossRef]

- (Sethibe and Malinga 2021) Sethibe, T., and S. Malinga. 2021. “Blockchain Technology Innovation: An Investigation of the Accounting and Auditing Use-Cases.” In Proc. Eur. Conf. Innov. Entrepren., ECIE, edited by Matos F., Ferreiro M.D.F., Salavisa I., and Rosa A., 892–900. Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited. [CrossRef]

- (Sheldon 2023) Sheldon, Mark D. 2023. “Preparing Auditors to Evaluate Blockchains Used to Track Tangible Assets.” Current Issues in Auditing, December, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- (Shvayko and Grebeniuk 2020) Shvayko, ML, and NO Grebeniuk. 2020. “Current Crediting Instruments Influencing Investment Climate in Ukraine.” Financial and Credit Activity-Problems of Theory and Practice 1 (32): 414–23.

- (Smith 2018) Smith, S.S. 2018. “Implications of Next Step Blockchain Applications for Accounting and Legal Practitioners: A Case Study.” Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal 12 (4): 77–90. [CrossRef]

- (Smith 2021a) Smith, S.S. 2021a. “Crypto Accounting Valuation, Reporting, and Disclosure.” The Emerald Handbook of Blockchain for Business. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (Smith 2021b) Smith, S.S. 2021b. “Decentralized Finance & Accounting – Implications, Considerations, and Opportunities for Development.” International Journal of Digital Accounting Research 21: 129–53. [CrossRef]

- (Smith 2023) Smith, S.S. 2023. “The Cryptoasset Auditing and Accounting Landscape.” The Emerald Handbook on Cryptoassets: Investment Opportunities and Challenges. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (Smith and Castonguay 2020) Smith, S.S., and J.J. Castonguay. 2020. “Blockchain and Accounting Governance: Emerging Issues and Considerations for Accounting and Assurance Professionals.” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting. American Accounting Association. [CrossRef]

- (Smith, Petkov and Lahijani 2019) Smith, S.S., R. Petkov, and R. Lahijani. 2019. “Blockchain and Cryptocurrencies – Considerations for Treatment and Reporting for Financial Services Professionals.” International Journal of Digital Accounting Research 19: 59–78. [CrossRef]

- (Soepriyanto, Havidz and Handika 2023) Soepriyanto, G., S.A.H. Havidz, and R. Handika. 2023. “Crypto Goes East: Analyzing Bitcoin, Technological and Regulatory Contagions in Asia–Pacific Financial Markets Using Asset Pricing.” International Journal of Emerging Markets. [CrossRef]

- (Sokolenko et al. 2019) Sokolenko, L., T. Ostapenko, O. Kubetska, O. Portna, and T. Tran. 2019. “Cryptocurrency: Economic Essence and Features of Accounting.” Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal 23 (Special Issue 2). https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85071699405&partnerID=40&md5=aae414a62836e6bbf8b4416444e8d6be.

- (Stern and Reinstein 2021) Stern, M., and A. Reinstein. 2021. “A Blockchain Course for Accounting and Other Business Students.” Journal of Accounting Education. Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (Stratopoulos 2020) Stratopoulos, T.C. 2020. “Teaching Blockchain to Accounting Students.” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting. 9009 Town Center Parkway, Lakewood Ranch, FL, United States: Amer Accounting Assoc. [CrossRef]

- (Tang and Tang 2019) Tang, Qingliang, and Lie Ming Tang. 2019. “Toward a Distributed Carbon Ledger for Carbon Emissions Trading and Accounting for Corporate Carbon Management.” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 16 (1): 37–46. [CrossRef]

- (Tapscott and Tapscott 2016) Tapscott, Don, and Alex Tapscott. 2016. Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology behind Bitcoin Is Changing Money, Business, and the World. International edition. New York, New York: Portfolio/Penguin.

- (Terando, Cataldi and Mennecke 2017) Terando, WD, B Cataldi, and BE Mennecke. 2017. “Impact of the IRC Section 475 Mark-to-Market Election on Bitcoin Taxation.” ATA Journal of Legal Tax Research 15 (1): 66–76. [CrossRef]

- (Tiron-Tudor, Mierlita and Manes Rossi 2024) Tiron-Tudor, Adriana, Stefania Mierlita, and Francesca Manes Rossi. 2024. “Exploring the Uncharted Territories: A Structured Literature Review on Cryptocurrency Accounting and Auditing.” The Journal of Risk Finance 25 (2): 253–76. [CrossRef]

- (Tsujimura and Tsujimura 2019) Tsujimura, K., and M. Tsujimura. 2019. “Flow of Funds Analysis: A Combination of Roman Law, Accounting and Economics.” In Stat. J. IAOS, 35:691–702. IOS Press. [CrossRef]

- (Tzagkarakis and Maurer 2023) Tzagkarakis, G., and F. Maurer. 2023. “Horizon-Adaptive Extreme Risk Quantification for Cryptocurrency Assets.” Computational Economics. Van Godewijckstraat 30, 3311 GZ Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. [CrossRef]

- (van Eck and Waltman 2023) van Eck, Nees Jan, and Ludo Waltman. 2023. VOSviewer Manual. Accessed 2024. https://www.vosviewer.com/documentation/Manual_VOSviewer_1.6.20.pdf.

- (Vasicek, Dmitrovic and Cicak 2019) Vasicek, D, V Dmitrovic, and J Cicak. 2019. “Accounting of Cryptocurrencies under IFRS.” In University of Rijeka, edited by ML Simic and B Crnkovic, 550–63.

- (Vedapradha and Ravi 2023) Vedapradha, R., and H. Ravi. 2023. “Blockchain: An EOM Approach to Reconciliation in Banking.” Innovation & Management Review. Floor 5, Northspring 21-23 Wellington Street, Leeds, W Yorkshire, England: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- (Veuger 2021) Veuger, J. 2021. “Digitization and Blockchain in Finance, The Netherlands in 2020 and 2021.” International Journal of Applied Economics, Finance and Accounting. Online Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- (Vičič and Tošić 2022) Vičič, J., and A. Tošić. 2022. “Application of Benford’s Law on Cryptocurrencies.” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 17 (1): 313–26. [CrossRef]

- (Vigna and Casey 2015) Vigna, Paul, and Michael J. Casey. 2015. The Age of Cryptocurrency: How Bitcoin and the Block- Chain Are Challenging the Global Economic Order. St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

- (Vincent and Davenport 2022) Vincent, N.E., and S.A. Davenport. 2022. “Accounting Research Opportunities for Cryptocurrencies.” Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 19 (1): 79–93. [CrossRef]

- (Vincent and Wilkins 2020) Vincent, N.E., and A.M. Wilkins. 2020. “Challenges When Auditing Cryptocurrencies.” Current Issues in Auditing 14 (1): A46–58. [CrossRef]

- (Vodáková and Foltyn 2020a) Vodáková, J, and J Foltyn. 2020a. “Financial Reporting of Cryptocurrencies.” In Masaryk University Brno, edited by KS Soliman, 12325–30.

- (Vodáková and Foltyn 2020b) Vodáková, J, and J Foltyn. 2020b. “Valuation of Cryptocurrencies in Selected EU Countries.” In Masaryk University Brno, edited by KS Soliman, 15529–34.

- (Volosovych and Baraniuk 2018) Volosovych, S., and Y. Baraniuk. 2018. “Tax Control of Cryptocurrency Transactions in Ukraine.” Banks and Bank Systems 13 (2): 89–106. [CrossRef]

- (Vumazonke and Parsons 2023) Vumazonke, N, and S Parsons. 2023. “An Analysis of South Africa’s Guidance on the Income Tax Consequences of Crypto Assets.” South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 26 (1). [CrossRef]

- (Yan, Yan and Gupta 2022) Yan, HQ, KJ Yan, and R Gupta. 2022. “A Survey of the Accounting Industry on Holdings of Cryptocurrencies in Xiamen City, China.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15 (4). [CrossRef]

- (Yang and Hamori 2021) Yang, L., and S. Hamori. 2021. “The Role of the Carbon Market in Relation to the Cryptocurrency Market: Only Diversification or More?” International Review of Financial Analysis. Ste 800, 230 Park Ave, New York, NY 10169 USA: Elsevier Science Inc. [CrossRef]

- (Yatsyk and Shvets 2020) Yatsyk, T, and V Shvets. 2020. “Cryptoassets as an Emerging Class of Digital Assets in the Financial Accounting.” Economic Annals-XXI 183 (5–6): 106–15. [CrossRef]

- (Yee, Heong and Chin 2020) Yee, T.S., A.Y.K. Heong, and W.S. Chin. 2020. “Accounting Treatment of Cryptocurrency: A Malaysian Context.” Management and Accounting Review 19 (3): 119–49.

- (Yu, Lin and Tang 2018) Yu, T, ZW Lin, and QL Tang. 2018. “Blockchain: The Introduction and Its Application in Financial Accounting.” Journal of Corporate Accounting and Finance 29 (4): 37–47. [CrossRef]

- (Zadorozhnyi et al. 2022) Zadorozhnyi, ZM, V Muravskyi, M Humenna-Derij, and N Zarudna. 2022. “Innovative Accounting and Audit of the Metaverse Resources.” Marketing and Management of Innovations, no. 4: 10–19. [CrossRef]

- (Zadorozhnyi, Murayskyi and Shevchuk 2018) Zadorozhnyi, ZMV, VV Murayskyi, and OA Shevchuk. 2018. “Management Accounting of Electronic Transactions With the Use of Cryptocurrencies.” Financial and Credit Activity-Problems of Theory and Practice 3 (26): 169–77. [CrossRef]

- (Zakaria 2022) Zakaria, H. 2022. “The Role of International Tax Accounting in Assessing Digital and Virtual Tax Issues.” Accounting, Finance, Sustainability, Governance and Fraud. Springer. [CrossRef]

- (Zelic and Baros 2018) Zelic, D., and N. Baros. 2018. “Cryptocurrency: General Challenges of Legal Regulation and the Swiss Model of Regulation.” Edited by T Studzieniecki, M Kozina, and DS Alilovic. Economic and Social Development (Esd 2018): 33rd International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development “Managerial Issues in Modern Business.” International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development. Mihanoviceva 4, Varazdin, 00000, Croatia: Varazdin Development & Entrepreneurship Agency.

- (Zianko, Nechyporenko and Waldshmidt 2022) Zianko, V. V., T. D. Nechyporenko, and I. M. Waldshmidt. 2022. “Adaptation Mechanism of the Crypto Industry in the Process of Virtualization of Financial Flows.” Academy Review. Sicheslavska Naberezhna St, 18, Dnipro, 49000, Ukraine: Alfred Nobel Univ. [CrossRef]

| Country | Citations | Country | Citations | Country | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 971 | Malta | 47 | Saudi Arabia / Spain | 18 |

| Australia | 830 | Czech Republic | 45 | New Zealand | 10 |

| Austria | 696 | China | 35 | Slovakia / UAE | 7 |

| Italy | 269 | Russia | 30 | South Korea | 6 |

| France | 219 | Malta | 47 | Lithuania / Turkey | 4 |

| United Kingdom | 135 | Nigeria | 26 | Singapore / Slovenia | 3 |

| Ireland | 71 | Ukraine | 26 | Brazil / Jordan / Norway | 2 |

| Canada | 63 | Finland | 25 | Romania / Switzerland | 2 |

| Lebanon | 61 | South Africa | 24 | Croatia / Greece / Pakistan | 1 |

| Japan | 47 | Malaysia | 21 | Azerbaijan / Netherlands | 1 |

| Cluster | Authors |

|---|---|

| Cluster 1 – red (27 items): | Appelbaum, Castonguay, Chou, Church, Clark, Cohen, Coyne, Dai, Dunn, Dyball, Eskandari, Hwang, Jenkins, Kinory, Kokina, Li, Mancha, McMickle, Nehmer, Pachamanova, Schneider, Seethamraju, Sheldon, Smith, Vasarhelyi, Wang, Wei |

| Cluster 2 – green (19 items): | Akhmadeev, Ammous, Boulianne, Cho, Fuller, Gilmour, Gyonyorova, Hampl, Jayasuriya, Jumde, Lehoux, Lukiyanova, Markelevich, Morozova, Pandey, Pimentel, Sims, Yumashev |

| Cluster 3 – blue (18 items): | Botchie, De V, Gomaa A, Gomaa M, Han, Holub, Jarvis, Johnson, Lombardi, McCallig, Mordi, Moscariello, Pizzo, Ramassa, Robb, Rohde, Shiwakoti, Stampone |

| Cluster 4 – yellow (16 items): | Alsalmi, Avhustova, Fomina, Gelashvili, Lin, Moshkovska, Nebreda, Pedreno, Rafique, Raiborn, Romashko, Sivitanides, Tang, Ullah, Yu T |

| Cluster 5 – purple (15 items): | Agrawal, Birt, Bourveau, Chou, Cong, De G, Ellahie, Jackson, Landsman, Luo, Luu, Macciocchi, Maydew, Rabetti, Yu S |

| Cluster 6 – turquoise (12 items): | Baraniuk, Beigman, Bellucci, Bianchi, Brennan, Gan, Hsieh, Manetti, Netessine, Sannella, Tsoukalas, Volosovych |

| Publication Title | Authors | Journal | Year | Citations | Average / year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Bitcoin: Economics, Technology, and Governance” | Bohme, R et al. | “Journal of Economic Perspectives” | 2015 | 696 | 69.60 |

| “Bitcoin: Medium of Exchange or Speculative Assets?” | Baur, DG; Hong, K and Lee, AD | “Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money” | 2018 | 604 | 86.29 |

| “Toward Blockchain-Based Accounting and Assurance” | Dai, J and Vasarhelyi, MA | “Journal of Information Systems” | 2017 | 297 | 37.13 |

| “Bitcoin for Energy Commodities Before and After the December 2013 Crash: Diversifier, Hedge or Safe Haven?” | Bouri, E et al. | “Applied Economics” | 2017 | 216 | 27.00 |

| “Conditional Tail-Risk in Cryptocurrency Markets” | Borri, N | “Journal of Empirical Finance” | 2019 | 168 | 28.00 |

| “Blockchain: Emergent Industry Adoption and Implications for Accounting” | Kokina, J; Mancha, R and Pachamanova, D | “Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting” | 2017 | 134 | 16.75 |

| “Accounting and Auditing at the Time of Blockchain Technology: A Research Agenda” | Schmitz, J and Leoni, G | “Australian Accounting Review” | 2019 | 128 | 21.33 |

| “Can Blockchains Serve an Accounting Purpose?” | Coyne, JG and McMickle, PL | “Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting” | 2017 | 101 | 12.63 |

| “Financial Regulations and Price Inconsistencies Across Bitcoin Markets” | Pieters, G and Vivanco, S | “Information Economics and Policy” | 2017 | 93 | 11.63 |

| “Bitcoin Research Across Disciplines” | Holub, M and Johnson, J | “The Information Society” | 2018 | 75 | 10.71 |

| Institution | Documents | Citations | Total link power |

|---|---|---|---|

| City University of New York Cuny System | 6 | 81 | 20 |

| Rutgers State University | 5 | 310 | 51 |

| Columbia University | 3 | 91 | 8 |

| Concordia University | 3 | 56 | 26 |

| Montclair State University | 3 | 36 | 22 |

| Masaryk University Brno | 3 | 9 | 12 |

| Taras Shevchenko National University Kyiv | 3 | 7 | 12 |

| Southwestern University of Finance & Economics | 2 | 326 | 55 |

| Luiss University | 2 | 183 | 0 |

| University of Genoa | 2 | 139 | 33 |

| RMIT University | 2 | 128 | 23 |

| Shenzhen University | 2 | 94 | 19 |

| University of Auckland | 2 | 40 | 47 |

| University Witwatersrand | 2 | 24 | 15 |

| Clusters | Most relevant key terms | Occurrences | Total link strength | Main topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cluster 1 red (ten items) |

accounting | 58 | 167 | Financial accounting and reporting |

| crypto assets | 20 | 59 | ||

| IFRS | 15 | 35 | ||

| distributed ledger technology | 11 | 40 | ||

| financial reporting | 10 | 27 | ||

| stablecoins | 4 | 19 | ||

| intangible assets | 4 | 13 | ||

| ICO (initial coin offering) | 3 | 12 | ||

| tokens | 3 | 8 | ||

| banking | 3 | 6 | ||

|

Cluster 2 green (nine items) |

cryptocurrency | 84 | 182 | Taxation |

| taxation | 16 | 32 | ||

| digital assets | 5 | 12 | ||

| crypto | 5 | 10 | ||

| IRS | 3 | 10 | ||

| NFT | 3 | 10 | ||

| accounting information systems | 3 | 7 | ||

| mining | 3 | 6 | ||

| electronic money | 3 | 4 | ||

|

Cluster 3 blue (four items) |

auditing | 31 | 92 | Auditing |

| smart contract | 13 | 46 | ||

| triple-entry accounting | 6 | 20 | ||

| assurance | 3 | 9 | ||

|

Cluster 4 yellow (four items) |

innovation | 5 | 18 | Innovation management |

| artificial intelligence | 4 | 10 | ||

| management | 3 | 10 | ||

| digital finance | 3 | 5 | ||

|

Cluster 5 purple (four items) |

bitcoin | 43 | 91 | Investments |

| digital currency | 6 | 18 | ||

| virtual currency | 5 | 11 | ||

| safe haven | 3 | 5 | ||

| Cluster 6 turquoise | blockchain | 80 | 196 | Accounting |

| (two items) | accounting education | 3 | 2 | education trends |

| Cluster 7 orange | governance | 4 | 11 | Frameworks |

| (two items) | technology | 3 | 5 |

| Authors | Country | Financial Accounting | Managerial Accounting | Taxation | Auditing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdennadher, S et al. (2022) | United Arab Emirates | ||||

| Adams, MT and Bailey, WA (2021) | USA | ||||

| Adelowotan, M and Coetsee, D (2021) | South Africa | ||||

| Alamad, S.(2019) | United Kingdom | ||||

| Alhasana, KAH and Alrowwad, AMM (2022) | Jordan | ||||

| Alles, M and Gray, GL (2020) | USA | ||||

| Alles, M and Gray, GL (2023) | USA | ||||

| Al-Htaybat, K; Hutaibat, K and von Alberti-Alhtaybat, L (2019) | Saudi Arabia, Jordan | ||||

| Al-Wreikat, A; Almasarwah, A and Al-Sheyab, O (2023) | USA | ||||

| Alsalmi, N; Ullah, S and Rafique, M (2023) | United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia | ||||

| ALSaqa, ZH, Hussein, AI and Mahmood, SM (2019) | Iraq | ||||

| Altukhov, P; Nozhkina, E and Dushevina, E (2020) | Russia | ||||

| Ammous, S (2018) | Lebanon | ||||

| Angeline, YKH et al. (2021) | Malaysia | ||||

| Appelbaum, D and Nehmer, RA (2020) | USA | ||||

| Appelbaum, D et al. (2022) | USA | ||||

| Atik, A and Kelten, GS (2021) | Turkey | ||||

| Barros, F; Bertolai, J and Carrijo, M (2023) | Brazil | ||||

| Baur, DG; Hong, K and Lee, AD (2018) | Australia, South Korea | ||||

| Beigman, E et al. (2023) | USA | ||||

| Bellucci, M; Bianchi, DC and Manetti, G (2022) | Italy | ||||

| Bennett, S et al. (2020) | Canada, United Kingdom | ||||

| Blahušiaková, M (2022) | Slovakia | ||||

| Böhme, R et al. (2015) | Austria, SUA | ||||

| Bondarenko, O; Kichuk, O and Antonov, A (2019) | Ukraine | ||||

| Borri, N (2019) | Italy | ||||

| Borri, N and Shakhnov, K (2022) | Italy, United Kingdom | ||||

| Bouri, E et al. (2017) | France, Lebanon, Norway | ||||

| Bourveau, T et al.(2022) | USA | ||||

| Bonyuet, D (2020) | USA | ||||

| Bozdoğanoğlu, B (2022) | Turkey | ||||

| Buhussain, G and Hamdan, A (2023) | Bahrain | ||||

| Caliskan, K (2020) | USA | ||||

| Cassidy, J et al. (2020) | New Zealand, United Kingdom, Australia | ||||

| Chou, CC et al. (2021) | USA, Taiwan | ||||

| Chou, JH; Agrawal, P and Birt, J (2022) | Australia | ||||

| Church, KS; Smith, SS and Kinory, E (2021) | USA | ||||

| Corbet, S; Urquhart, A and Yarovaya, L (2020) | Ireland, United Kingdom | ||||

| Coyne, JG and McMickle, PL (2017) | USA | ||||

| Cong, LW et al. (2023) | USA, Singapore | ||||

| Cyrus, R (2023) | USA | ||||

| Dai, J; He, N and Yu, HZ (2019) | China | ||||

| Dai, J and Vasarhelyi, MA (2017) | USA, China | ||||

| Davenport, SA and Usrey, SC (2023) | USA | ||||

| Derun, I and Mysaka, H (2022) | Ukraine | ||||

| Desai, H (2023) | USA | ||||

| Dunn, RT; Jenkins, JG and Sheldon, MD (2021) | USA | ||||

| Dyball, MC and Seethamraju, R (2022) | Australia | ||||

| Fomina, O et al. (2019) | Ukraine | ||||

| Fuller, SH and Markelevich, A (2020) | USA | ||||

| Gan, J; Tsoukalas, G and Netessine, S (2021) | USA | ||||

| Gao, XX (2023) | China | ||||

| Garanina, T; Ranta, M and Dumay, J (2022) | Finland, Australia, Netherlands, Denmark | ||||

| García-Monleon, F; Erdmann, A and Arilla, R (2023) | Spain | ||||

| Gietzmann, M and Grossetti, F (2021) | Italy | ||||

| Gomaa, AA; Gomaa, MI and Stampone, A (2019) | USA | ||||

| Gurdgiev, C and Fleming, A (2021) | USA, Ireland | ||||

| Hampl, F and Gyönyörová, L (2021) | Czech Republic | ||||

| Han, HD et al. (2023) | United Kingdom | ||||

| Handoko, BL; Gunawan, BA and Djati, MFP (2022) | Indonesia | ||||

| Harrast, SA; McGilsky, D and Sun, Y (2022) | USA | ||||

| Hazar, HB (2020) | Turkey | ||||

| Holub, M and Johnson, J (2018) | Australia | ||||

| Huang, RH; Deng, H and Chan AFL (2023) | China | ||||

| Hubbard, B (2023) | USA | ||||

| Ilham, RN et al. (2019a) | Indonesia, Malaysia | ||||

| Ilham, RN et al. (2019b) | Indonesia, Malaysia | ||||

| Jackson, AB and Luu, S (2023) | Australia | ||||

| Jayasuriya, DD and Sims, A (2023) | New Zealand | ||||

| Jumde, A and Cho, BY (2020) | United Arab Emirates, South Korea | ||||

| Juskaite, L and Gudelyte-Zilinskiene, L (2022) | Lithuania | ||||

| Kaden, SR; Lingwall, JW and Shonhiwa, TT (2021) | USA | ||||

| Kampakis, S (2022) | United Kingdom | ||||

| Kokina, J; Mancha, R and Pachamanova, D (2017) | USA | ||||

| Kolková, A (2018) | Czech Republic | ||||

| Klopper, N and Brink, SM (2023) | South Africa | ||||

| Kochergin, DA (2020) | Russia | ||||

| Koker, TE and Koutmos, D (2020) | USA | ||||

| Lee, LS; Appelbaum, D and Mautz, RDM (2022) | USA | ||||

| Lombardi, R; de Villiers, C and Pizzo, M (2022) | Italy, New Zealand, South Africa | ||||

| Luo, M and Yu, SC (2022) | China | ||||

| Maffei, M; Casciello, R and Meucci, F (2021) | Italy | ||||

| Makurin, A et al. (2023) | Ukraine | ||||

| Makurin, A (2023) | Ukraine | ||||

| Matusky, T (2017) | Slovakia | ||||

| McCallig, J; Robb, A and Rohde, F (2019) | Ireland, Australia | ||||

| McGuigan, N; Ghio, A and Kern, T (2021) | USA | ||||

| Morozova, T et al. (2020) | Russia, Switzerland | ||||

| Mosteanu, NR and Faccia, A (2020) | Malta, United Kingdom | ||||

| Munteanu et al. (2023) | Romania | ||||

| Niftaliyev, SG (2023) | Azerbaijan | ||||

| Ntanos, S et al. (2020) | Greece | ||||

| Nylen, PC and Huels, BW (2022) | USA | ||||

| Obu, OC and Ukpere, WI (2022) | Norway | ||||

| O’Leary, D (2018) | USA | ||||

| Ozeran, A and Gura, N (2020) | Ukraine | ||||

| Ozili, PK (2023) | Nigeria | ||||

| Pan, L; Vaughan, O and Wright, CS (2023) | United Kingdom | ||||

| Pandey, D and Gilmour, P (2023) | India, United Kingdom | ||||

| Pantielieieva, NM et al. (2019) | Ukraine | ||||

| Papp, A; Almond, D and Zhang, S (2023) | Switzerland | ||||

| Parrondo, L (2020) | Spain | ||||

| Parrondo, L (2023) | Spain | ||||

| Păunescu, M (2018) | Romania | ||||

| Pedreño, EP; Gelashvili, V and Nebreda, LP (2021) | Spain | ||||

| Pelucio-Grecco, MC; dos Santos Neto, JP and Constancio, D (2020) | Brazil | ||||

| Pflueger, D; Kornberger, M and Mouritsen, J (2022) | France, Austria, Sweden, Denmark | ||||

| Pieters, G and Vivanco, S (2017) | USA | ||||

| Pimentel, E et al. (2021) | Canada | ||||

| Pimentel, E and Boulianne, E (2020) | Canada | ||||

| Proelss, J; Schweizer, D and Sevigny, S (2023) | Canada | ||||

| Procházka, D (2018) | Czech Republic | ||||

| Procházka, D (2019) | Czech Republic | ||||

| Raiborn, C and Sivitanides, M (2015) | USA | ||||

| Ram, A; Maroun, W and Garnett, R (2016) | South Africa | ||||

| Ramassa, P and Leoni, G (2022) | Italy | ||||

| Rana, T et al. (2023) | Sweden, Australia | ||||

| Reepu (2019) | India | ||||

| Rella, L (2020) | United Kingdom | ||||

| Salawu, MK and Moloi, T (2018) | South Africa | ||||

| Sarwar, MI et al. (2023) | Pakistan | ||||

| Schmitz, J and Leoni, G (2019) | Australia, Italy | ||||

| Sethibe, T and Malinga, S (2021) | South Africa | ||||

| Shvayko, ML and Grebeniuk, NO (2020) | Ukraine | ||||

| Smith, SS (2018) | USA | ||||

| Smith, SS (2021a) | USA | ||||

| Smith, SS (2021b) | USA | ||||

| Smith, SS (2023) | USA | ||||

| Smith, SS and Castonguay, JJ (2020) | USA | ||||

| Smith, SS; Petkov, R and Lahijani, R (2019) | USA | ||||

| Soepriyanto, G; Havidz, SAH and Handika, R (2023) | Indonesia, Japan | ||||

| Stratopoulos, TC (2020) | Canada | ||||

| Sokolenko, L et al. (2019) | Ukraine | ||||

| Stern, M and Reinstein, A (2021) | USA | ||||

| Terando, WD; Cataldi, B and Mennecke, BE (2017) | USA | ||||

| Tsujimura, K and Tsujimura, M (2019) | Japan | ||||

| Tzagkarakis, G and Maurer, F (2023) | Greece, France | ||||

| Vasicek, D; Dmitrovic, V and Cicak, J (2019) | Croatia, Serbia | ||||

| Vedapradha, R and Ravi, H (2023) | India | ||||

| Veuger, J (2021) | Netherlands | ||||

| Vicic, J and Tosic, A (2022) | Slovenia | ||||

| Vincent, NE and Davenport, SA (2022) | USA | ||||

| Vincent, NE and Wilkins, AM (2020) | USA | ||||

| Vodáková, J and Foltyn, J (2020a) | Czech Republic | ||||

| Vodáková, J and Foltyn, J (2020b) | Czech Republic | ||||

| Volosovych, S and Baraniuk, Y (2018) | Ukraine | ||||

| Vumazonke, N and Parsons, S (2023) | South Africa | ||||

| Yan, HQ; Yan, KJ and Gupta, R (2022) | China, Australia | ||||

| Yang, L and Hamori, S (2021) | China, Japan | ||||

| Yatsyk, T and Shvets, V (2020) | Ukraine | ||||

| Yee, TS; Heong, AYK and Chin, WS (2020) | Malaysia | ||||

| Yu, T; Lin, ZW and Tang, QL (2018) | China, Australia, United Kingdom | ||||

| Zadorozhnyi, ZMV; Murayskyi, VV and Shevchuk, OA (2018) | Ukraine | ||||

| Zadorozhnyi, ZMV et al. (2022) | Ukraine | ||||

| Zakaria, H (2022) | Egypt | ||||

| Zelic, D and Baros, N (2018) | Switzerland, Bosnia & Herzegovina | ||||

| Zianko, VV; Nechyporenko, TD and Waldshmidt, IM (2022) | Ukraine | ||||

| Total articles number | 157 | 138 | 51 | 45 | 53 |

| Total percentage | 100% | 87% | 32% | 28% | 34% |

| Authors | Fair value or revaluation treatment | Cost treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Alsalmi, Ullah, and Rafique (2023) | ||

| Alhasana and Alrowwad (2022) | ||

| Angeline et al. (2021) | ||

| Beigman et al. (2023) | ||

| Bellucci, Cesa Bianchi, and Manetti (2022) | ||

| Blahušiaková (2022) | ||

| Corbet, Urquhart, and Yarovaya (2020) | ||

| Derun and Mysaka (2022) | ||

| Fomina et al. (2019) | ||

| Huang, Deng, and Chan (2023) | ||

| Hubbard (2023) | ||

| Jackson and Luu (2023) | ||

| Jayasuriya and Sims (2023) | ||

| Klopper and Brink (2023) | ||

| Luo and Yu (2022) | ||

| Makurin et al. (2023) | ||

| Morozova et al. (2020) | ||

| Niftaliyev (2023) | ||

| Pandey and Gilmour (2023) | ||

| Parrondo (2023) | ||

| Păunescu (2018) | ||

| Pimentel and Boulianne (2020) | ||

| Procházka (2018) | ||

| Raiborn and Sivitanides (2015) | ||

| Ram, Maroun, and Garnett (2016) | ||

| Ramassa and Leoni (2022) | ||

| Smith, Petkov, and Lahijani (2019) | ||

| Vasicek, Dmitrovic, and Cicak (2019) | ||

| Vodáková and Foltyn (2020b) | ||

| Volosovych and Baraniuk (2018) | ||

| Yan, Yan, and Gupta (2022) | ||

| Yatsyk and Shvets (2020) | ||

| Yee, Heong, and Chin (2020) | ||

| Zadorozhnyi, Murayskyi, and Shevchuk (2018) | ||

| Total | 31 | 18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).