1. Introduction

Agricultural sector plays a significant role towards South African’s economy as it contributes 4, 2% of the Gross domestic product (GDP) [

1]. The sector remains vulnerable to climate change risks taking into consideration that agricultural system is rain-fed dependent, with low adaptive capacity [

2,

3]. The economic impact of climate change in South Africa is related to many aspects as it led to the sector experiencing a decline in the GDP, subsequently leading to loss in job opportunities, and foreign exchange earnings [

4]. Maize crop plays a crucial role in the country’s food security as it is considered a stable food for households and source of feed for livestock [

5]. Maize contributes to household consumption because it is cheap and easily accessible [

5]. Subsequently, the crop contributes towards poverty alleviation through provision of income for rural households, improvement of livelihoods, and sustainable development goals [

6,

7,

8]. The methods of maize cultivation in smallholder farming make the crop become highly susceptible to effects of climate change. Agriculture depends on climate to guarantee crop productivity, profitability, and quality of life [

9]. Therefore, climate change poses the key hazards to agricultural production as it alters precipitation, temperature, carbon dioxide, climate variability, and nutrient uptake [

10]. Not only maize is subjected to climate change (extreme weather and unreliable rainfall), but smallholder farmers are also exposed to climate changes as they have limited access to resources and capacity to adapt to these risks [

11,

12].

This necessitates for smallholder farmers to assess the impact of these risks and address them through various improved adaptation strategies. Climate change-related challenges dictate for smallholder farmers to adopt climate-smart agriculture (CSA) practices, but they have limited access to land and land ownership [

13,

14,

15] that permits them. CSA is a strategy to support agricultural systems globally while concurrently addressing three challenge areas through enhancing agriculture’s resilience to climate change, mitigating its effects (by enabling the farming sector to seize greenhouse gases), and guaranteeing global food security through creative financing, policies, and practices [

16,

17,

18]. Crop insurance, rainwater harvesting, drought-tolerant maize seeds, crop rotation, diversification, site-specific nutrient management, and conservation agriculture are examples of CSA. Some farmers use crop diversification as a strategy to mitigate climate change risks, reduce crop failure risk, and resist shocks. Literature has indicated that CSA is a key solution towards reducing the risks imposed and challenges caused by climate change, and therefore farmers need to adopt the practice of CSA [

19,

20]. It has been reported that the adoption rate of these adaptation strategies (CSA) remains relatively low by smallholder maize farmers due to high costs associated with the adoption and limited knowledge about these CSA practices [

21,

22,

23].

According to the project

’s suggested premise, farmers are particularly vulnerable to the negative impacts of climate change, but they also lack coordinated efforts and management plans to address these challenges. Furthermore, even those who are aware of the changes find it challenging to adjust for the various variables that the current study investigated. The aim of this study was to analyze the willingness to adopt CSA among smallholder maize farmers and socio-economic factors influencing their willingness to adopt selected areas. Farmers

’ adaptive response to climate change is limited due to socio-economic factors influencing the available adaptation options [

24]. The study examines socioeconomic factors such as age, education, gender, farm size, farming experience, information about climate-smart agriculture, exposure to climate risks and farmers sensitivity towards the risks.

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Description of the Study Areas

The study was conducted at three selected areas: Ga-Makanye in Polokwane Municipality, Gabaza in Greater Tzaneen local Municipality, and Gabaza in Greater Giyani Municipality in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Ga-Makanye is a small village situated outside Polokwane and it has a total of 9536 population [

25]. The area is dominated by black and Sepedi speaking individuals. Gabaza is also a small village outside Tzaneen town dominated by black people mainly consisting of different tribes. The area is dominated by XiTsonga speaking individuals. Giyani is a town situated in the eastern part of the town and consist of 8098 population dominated by Xitsonga tribe [

25]. The study chose these three areas due to different agro-ecological zones and climatic conditions experienced [

26,

27].

Figure 1.

South African map showing 5 Districts in Limpopo Province. Source: Author’s compilation (2024).

Figure 1.

South African map showing 5 Districts in Limpopo Province. Source: Author’s compilation (2024).

2.2. Research Design

The study used multipurpose research design to validate both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. The multipurpose research design is essential because it does not only afford integration of quantitative and qualitative data, but it also provides an opportunity to researchers to use strength of one data to mitigate the weaknesses of the other data [

28]. Measures of dispersion (Descriptive statistics) and Double-hurdle model estimated using Probit and Tobit regression model were utilized to analyze factors influencing the willingness to adopt CSA among farmers.

2.2.1. Sampling Method(s) and Sample Size

The study employed multistage random sampling technique. In the first stage, Limpopo Province was purposefully, selected as the main area because of the prevalence of smallholder rural maize farming, which contributes to food security within the province and country. Secondly, two districts were purposively selected, which are Capricorn (dry sub-humid) and Mopani (semi-arid) due to different agro-ecological climate zones. Thirdly, Ga-Makanye village was purposively selected from Capricorn District in the Polokwane Municipality and two areas, which are Gabaza and Giyani Municipality were purposively selected from Mopani Municipality, respectively. Because researchers were unfamiliar with the study region and there were no maize farmers’ population, households were used as a proxy because majority of rural households in South Africa grow maize for consumption and income generation. The study used 209 sample sizes that was selected using Purposive Snowball sampling method. The study used Yamane’s formula to select the sample size for each area

There was no population for smallholder rural maize farmers’, the study has used number of households as a proxy to draw up sampling frame for sample size.

Ga-Makanye (n) = , Gabaza (n) = , Giyani (n) =

2.2.2. Data Collection

The study used primary cross-sectional data. The data was collected using both qualitative and quantitative methods to understand farmers’ willingness to adopt to CSA and factors influencing adoption [

29,

30]. The study used structured questionnaires, focused group discussions (FGDs) and Likert scale to collect data from the respondents. The collected data was used to describe socio-economic characteristics of maize farmers’ as well as factors influencing willingness to adopt (WTA) to adopt CSA.

2.2.3. Model Specification

The study uses Double-hurdle regression model estimated using Probit and Tobit (truncated). The model used is as follows:

“is considered as variable that explained the decision to adopt to CSA by smallholder maize farmers’,

is the variable that is observed adoption decision and takes the value of 1 if the smallholder farmer is willing to adopt at least 3 CSA practices and 0 if otherwise

is a dormant variable used to describe the decision on factors affecting the adoption

is observable variable of adoption measured as the number of CSA practices to adopt

C and X gives the direction for independent variables for the decision to adopt

and are the parameters to be estimated.

The equation below was used to calculate the direction of the relationship of the indicators. This gives rise to the Ordinary least squares equation for the variables. It is as follows.

2.2.4. Analytical Techniques

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics was used to offer a summary of the sample and its measures. Specifically, descriptive statistics was used to analyze the central tendencies, this includes, mean values, median and mode to address and describe the socioeconomic characteristics of smallholder maize farmers in selected areas of Ga-Makanye, Gabaza, and Giyani.

Double-hurdle regression model

The study used the Double-hurdle model on the presumption that CSA adoption willingness involves two separate judgments [

29]. According to Cragg [

32], Double-hurdle model implies that smallholder farmers would make two consecutive decisions on whether to adopt CSA [

21,

31]. Equations (6) and (7) reflect the first hurdle, the CSA adoption (Yes/No) factor, which was estimated using a Probit model. A truncated count distribution model was used in the second hurdle to find factors that affect adoption willingness.

In the Double-Hurdle model, the regression analysis of the probability to adopt CSA is estimated using a truncated regression procedure given by the following equation [

31].

Table 1.

Description of model variables for double-hurdle regression model.

Table 1.

Description of model variables for double-hurdle regression model.

| Dependent variable |

|

Description and Unit of Measurement |

|

| Willingness to adopt CSA |

WTA*i |

Binary: 1 = farmer is willing to adopt climate-smart agriculture

0= otherwise |

|

| Variable label |

Variable type |

Description |

Expected sign |

| Farm size (FS) |

Continuous |

Size of the farm in hectares |

+/- |

| Educational level (EL) |

Continuous |

Number of years spend in school |

+ |

| Gender (GND) |

Dummy |

1 = if the farmer is a female, 0= otherwise |

+ |

| Age (AG) |

Continuous |

Age of the farmers in years |

+/- |

| Agricultural experience (AE) |

Continuous |

Number of years practicing agriculture |

+/- |

| Household size (HS) |

Continuous |

Number of household members |

+/- |

| Income diversification (ID) |

Dummy |

1= farmer diversify their level of income, 0= otherwise |

+ |

| Crop diversification (CD) |

Dummy |

1 = farmer diversify their crop production, 0= otherwise |

+ |

| Access to extension services (AES) |

Dummy |

1= farmer has access to extension services, 0= otherwise |

+ |

| Information about climate-smart agriculture (ICSA) |

Dummy |

1= farmer has access to information, 0= otherwise |

+ |

| Exposure of the farm to climate risks (E) |

Dummy |

1= farmer is exposed to climate risks, 0= otherwise |

+ |

| Sensitivity to climate risks (S) |

Dummy |

1= farmer is sensitive to climate risks, 0= otherwise |

+/- |

| Insurance (IS) |

Dummy |

1= farmer has insurance, 0= otherwise |

- |

| Cooperative membership (CM) |

Dummy |

1= farmer is cooperative member, 0= otherwise |

+/- |

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.1.1. Smallholder Maize Farmers’ Willingness to Adopt CSA in Ga-Makanye, Gabaza, and Giyani

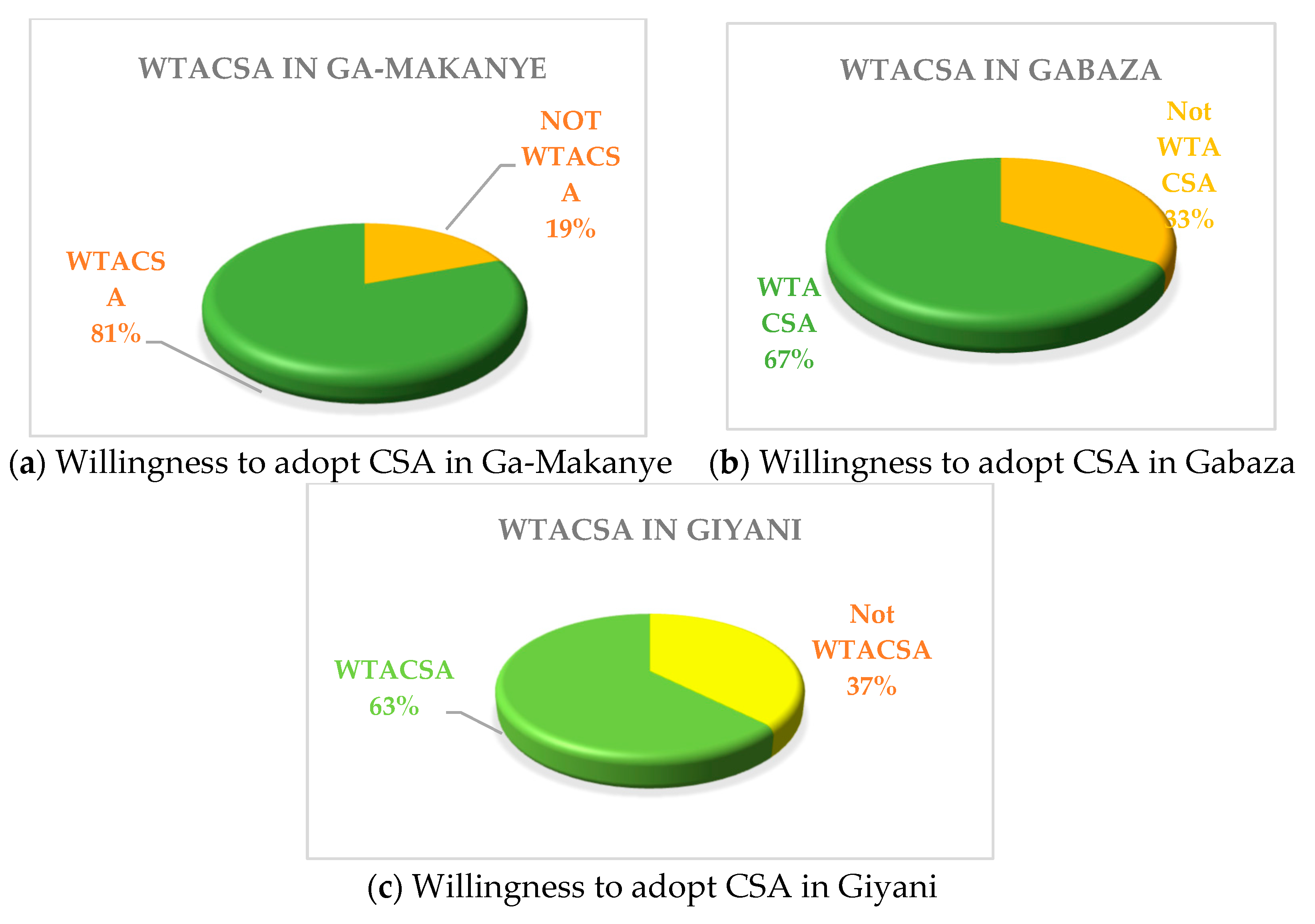

Figure 2a shows a larger proportion (81%) of sampled smallholder maize farmers in Ga-Makanye willing to adopt climate-smart agriculture (CSA). These farmers were willing to adopt CSA as an adaptation strategy to mitigate the risks posed by climate change. Conversely, a small number (19%) expressed unwillingness to adopt these CSA. Furthermore,

Figure 2b shows sampled smallholder maize farmers’ decision to adopt the CSA in Gabaza. About 67% of these farmers were willing to adopt CSA and 33% of them were unwilling to adopt these adaptation strategies due to illiteracy levels and limited capacity to understand new information and felt like these practices will be challenging to learn.

Figure 2c indicates about 63% of smallholder maize farmers’ decision to adopt CSA in Giyani and 37% of them who exhibited a reluctance to adopt CSA as their adaptation strategies. Farmers in the three selected study areas mentioned that adopting CSA will require high capital intensive, more costs associated with production and limited resources, hence, they were not willing to adopt.

Table 2 depicts the descriptive results for the categorical socioeconomic variables in the three selected areas: Ga-Makanye, Gabaza, and Giyani. From the table, there is an equal gender distribution in Ga-Makanye while in Gabaza and Giyani there are more female farmers at about 77% and 70, 8%. Smallholder maize farmers in Ga-Makanye were moderately to adequately educated with about 42% and 15.4% of the farmers who obtained secondary and tertiary education, respectively. However, in Gabaza and Giyani, more farmers about 33,3 % and 42,7%, respectively obtained no education, suggesting lower literate levels. Moreover, 14,9% and 10,4 farmers in Gabaza and Giyani managed to obtain tertiary education with 15, 4%, 14, 9%, and 10, 4%.

Additionally,

Table 2 revealed that more farmers had access to extension services at Ga-Makanye, Gabaza, and Giyani with about 59, 3%, 66, 7%, and 49%, respectively. This implies that farmers mostly get disseminated information about their production activities, however, these results are disputed by accessibility to information about CSA. There were fewer maize farmers from the sampled areas that had access to information pertaining adaptation strategies (CSA). Thus, 50%, 44, 8% and 45, 8% farmers were aware about various ways to mitigate against the risks posed by climate change in Ga-Makanye, Gabaza and Giyani, respectively.

A greater proportion of sampled maize farmers were highly exposed to the risks posed by climate change in Ga-Makanye (85%), Gabaza (86%) and Giyani (85%). Farmers were exposed to risks such as pest damage, high temperatures, and unreliable rainfall. Larger percentage of farmers in Ga-Makanye, Gabaza, and Giyani, 73%, 63%, and 67% were highly sensitive to climate risks, respectively.

3.1.2. Measures of Dispersion of the Sampled Smallholder Maize Farmers in Ga-Makanye, Gabaza, and Giyani

The study found a significant difference in maize farmers’ age and experience, with older farmers (83 years) having more experience (70 years) and younger ones having less. The average farmer lived with 5 people and had 4 hectares of land. The two-tailed t-test showed that older farmers had more experience, while younger farmers had less experience, and it was statistically significant at 5% level.

Table 3.

Measures of dispersion of the sampled smallholder maize farmers in Ga-Makanye.

Table 3.

Measures of dispersion of the sampled smallholder maize farmers in Ga-Makanye.

| Socioeconomic variable |

Mean |

St. Deviation |

Min |

Max |

T-test (Sig. 2-tailed) |

Age

|

60 |

18, 57 |

21 |

83 |

51, 7** |

Experience

|

24 |

20, 59 |

3 |

70 |

78, 9** |

Household size

|

5 |

2, 21 |

2 |

11 |

93, 2** |

| Farm size |

4 |

4, 63 |

0, 50 |

19 |

60, 7** |

The study reveals that the average age and experience level of smallholder maize farmers vary significantly. The mean difference between farmers aged 23 and 1 year and those with more years of experience was found to be extremely significant. The average farmer lived with 5 people and had 2 hectares of land (See

Table 4). The results suggest that older farmers have more experience, while younger farmers have less agricultural experience on the field.

The study reveals that smallholder maize farmers have an average age of 64 and 27 years, with varying degrees of experience (See

Table 5). The average farmer lives with 6 people and has 2 hectares of land. The results show that the t-test values are smaller than the 95% significance level, indicating that the mean values of farmers

’ age and experience do not significantly differ from one another.

3.2. Econometric Results

3.2.1. Test for Multicollinearity

The study used IBM SPSS 29.0 to conduct a multicollinearity test on a binary expected outcome regression model. The test used the variance inflator factor (VIF) to analyze the total effect of each independent variable against all independent variables. The study excluded insurance and age variables due to potential autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity problems. The results indicate that there is sufficient evidence that all variables had VIF that is less than 2 and < 10 (0, 4 – 0,1), with mean VIF of 1, 2885 for the sampled variables (N= 209). These results indicate that there is no multicollinearity problem in the model for sample.

Table 5.

Variance inflation factors (VIFs) of the regressors.

Table 5.

Variance inflation factors (VIFs) of the regressors.

| Explanatory variables |

Collinearity statistics |

|

| |

VIF |

1/VIF |

| Farm size (in hectares) |

1, 097 |

0, 911 |

| Educational level |

1, 805 |

0, 554 |

| Gender of a maize farmer |

1, 069 |

0, 935 |

| Agricultural experience |

1, 900 |

0, 526 |

| Household size |

1, 058 |

0, 945 |

| Income diversification |

1, 332 |

0, 750 |

| Crop diversification |

1, 200 |

0, 833 |

| Access to extension services |

1, 169 |

0, 855 |

| Information about CSA |

1, 201 |

0, 833 |

| Exposure to climate risks |

1, 263 |

0, 792 |

| Sensitivity to climate risks |

1, 335 |

0, 749 |

| Farmers’ cooperative membership |

1, 033 |

0, 968 |

| Mean VIF |

1, 2885 |

|

3.2.2. First Hurdle: Probit Regression Model of Results of Sampled Smallholder Maize Farmers in Ga-Makanye, Gabaza, and Giyani (n= 209)

The Double-hurdle regression results are presented in

Table 6 and

Table 7. The regression model’s Wald statsitics was significant at 1% suggesting a good fit of the model as a whole, Prob >chi2 = 0, 0000, which gives the study sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis that all regression coefficients in each hurdle are jointly equal to zero.

The first hurdle shows factors that influence the decision to adopt climate-smart agriculture (CSA) while the second hurdle shows factors that influence the adoption rate and intensity of use among smallholder maize farmers. From the results, a key factor in influencing the decision-making process towards adoption of adapatation strategies is the farmers’ literacy level and accessibility to new information, which requires comprehension skills obtained from educational backgrounds. From the results shown on

Table 6, smallholder maize farmers’ eduvational level (EL) p= 0, 2961, Crop diverisfication (CD) p= 0, 4276, and information about CSA (ICSA) p= 0, 5034 positively influenced the willingnes (decision) to adopt CSA. Conversly, smallholder maize farmers agriucltural experience (AE) p= 0, 1621, and household size (HS) p= 0, 0726 negatively influenced the decision to adopt CSA.

3.2.3. Second Hurdle: Probit Regression Model of Results of Sampled Smallholder Maize Farmers in Ga-Makanye, Gabaza, and Giyani (n= 209)

The results of the second hurdle from the Double-hurdle regression model (estimated via Tobit model) are presented in

Table 7. The second hurdle estimated the drivers of the adoption of CSA, which uses a maximum likelihood estimator efficient and consistent model parameter. The resuls depeicted on

Table 7, indicate that smallholder maize farmers’ EL p= 0, 2816, CD p= 0, 3881, ICSA p= 0, 4355 positively infleunced the adoption of CSA and intesnity to use these practices to adapat towards climate change. Maize farmers’ HS p= 0, 0061 =, and farmers AE p= 0, 0134 negatively infleunced the adoption of CSA to adapt towards climate change.

4. Discussion

The coefficients in the first hurdle (estimated via the Probit model) indicates how various factors affects the decision of adopting CSA. The results shows that smallholder maize farmers’ educational level (EL) is positive and statistically significant at 5% level. This positive effect implies that, 1 additional years in farmers’ educational level will posivietly influence the decision to adoopt CSA by 29, 61%. These results seem to be plausible with findings of Hitayezu et al. [

33] and Roco et al. [

34] [

33,

34], which showed that farmers educational levels posivitely influence the adoption of adapatation strategies because educationl achievements contribute to providing farmers with necessary skills and knowledge for implemeting desired adapatation strategies. Conversely, several writers discovered that the adoption of CSA practices was inversely correlated with the level of education [

42,

43,

44]. It follows that farmers with lower levels of education develop fewer comprehension abilities and are less conscious of climate change, which makes them less inclined to react to its impacts.

The coefficient of farmers’ agricultural experience (AE) is negative and sigficant at 5% level. This inverse relationship between farmers’ years in farming and adoption of CSA implies that, for every year that a farmer gain experince, there is 1, 6% likelihood that their decision to adopt CSA will be reduced. This results suggest that farmers with longer farming experience are more aware of risks posed by climate change and have already taken steps to mitigate those risks. Research by Ainembabazi & Mugisha [

35], suggests that agricultural experience positively impacts CSA adoption, as farmers with extensive experience appreciate the benefits of implementing CSA principles. However, Abegunde [

36] found no significant relationship between farming experience and CSA practice adoption.

Smallholder maize farmers’ ability to diversity their crops (CD) was found to be positive and statistically signicant at 5%. This postive effect implies that, 1% increase in farmers producing other crops than maize will results in a 42, 76% increase in farmers decision to adopt CSA. These results are consistent with research by Agbenyo et al. [

37] that showed that crop diversification is a key factor in CSA strategies to support resilience towards climate change.

Similarly, cofficeint on information about CSA was found be positive and significant at 5% level. This positive effect shows that 1% increase in the infromation and awareness about CSA will increase smallholder maize farmers’ decision to adopt CSA by 50, 34% likelihood. These results seem to be plausible with findings of Kalu & Mbanasor [

38] and Dung [

39] that found that knwoledge about CSA positively influenced the adoption decision of these adapatation stratagies. However, coefficient of smallholder maize farmes’ household size was found to be negative and significant at 5% level. This negative effect shows the inverse relationship between farmers’ household size and decision to adopt CSA. This implies that, 1 additional member living with the farmer will decrease the likelihood to adopt CSA by 7, 26%. These results are consistent with findings of Malila et al. [

40] that found an inverse influence between household size and adoption decision among farmers.

The empirical results indicate that in the second hurdle, farmers’ educational level (EL) is positive and significant at 5% level. This positive effect indicates that education positively influence the intensity and adoption rate of CSA among smallholder farmers. This implies that an additional 1 year in farmers acquiring education will likely influence the adoption rate of CSA by 28, 16%. These findings are consistent with the first hurdle results, which indicate that smallholder maize farmers’ willingness to adopt CSA is positively influenced by their level of education. This indicates that because farmers can readily understand the information, knowledge, and skills required, education plays a critical role in influencing their desire to embrace improved agricultural techniques such as CSA practices and techniques.

Smallholder maize farmers’ farming experience (AE) was found to be negative and statistically significant at 5% level. However, this negative relationship implies that there is an inverse influence or not much influence of farmers’ adoption rate towards CSA. This implies that an additional year on farmers level of experience in production of maize will likely reduce the adoption rate by 13, 4% chances. The implication is that farmers who have longer experience in farming have identified various adaptation strategies to reduce their vulnerability towards risks posed by climate change. These results seem to be in line with the study of Makamane et al. [

24], which found that experience in farming lowers the adoption rate of various adaptation strategies including CSA.

The empirical results indicate that farmers’ household size (HS) is negatively influencing the adoption of CSA among smallholder maize farmers and is significant at 5% level. The inverse relationship between household size and CSA adoption implies that the variable HS will not influence the adoption of CSA as there is abundant labor as there are more people living with the farmer who may assist with farming activities. These findings align with conclusions of Malila et al. [

40], showing that household size does not exert a statistically significant impact on the adoption level of CSA practices. The findings imply that one added member living with the farmer will decrease the willingness to adopt the CSA practices by 0,61%. This is because smallholder farmers rely on family labour for production, so, if farmers have more hands required for their produce, they are less likely to adopt the practices.

Moreover, information about CSA was found to be positive and statistically significant at 5% level. This positive effect implies that, 1% increase in CSA information accessibility will increase the adoption of these adaptation strategies by 43, 55%. The implication is that farmers become aware about CSA through accessing information relating to these CSA. Furthermore, crop diversification (CD) as a CSA practice was found to be positively influencing the willingness to adopt CSA among smallholder maize farmers and it is significant at 5% level. This positive relationship implies that when farmers not solely produce maize, but rather produce other crops, they are likely to adopt CSA practices to mitigate the risks imposed by climate change. The implication is that a 1% increase in farmers diversifying their production will increase the adoption rate and use of CSA by 38, 8%. These results concur with findings of Awiti [

41] noting that crop diversification positively influence the labour cos share, implying that more labour is required in a diversified farming system, hence, crop diversification’s effects on production cost. The results do not necessarily imply CSA but show that crop diversification can be used as an improved farming technique to mitigate against the risks of climate change.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

The study aimed to analyze the socioeconomic factors influencing smallholder maize farmers’ willingness to adopt climate-smart agriculture (CSA). Subsequently, Double-Hurdle model was used to examine those factors, which influence smallholder maize farmers’ willingness to adopt CSA. Results showed that educational level, crop diversification, and information about CSA positively influenced farmers’ willingness to adopt CSA, while agricultural experience and household size negatively influenced it. The null hypothesis of this study stating that there are no factors that influence the willingness to adopt CSA is rejected as there is sufficient evidence that there are factors that influences the will to adopt CSA and consequently, the capacity of the smallholder farmers to adapt to climate related challenges. Department of Agriculture, Land Reform, and Rural Development should provide CSA workshops and educational programs to farmers, enhancing their knowledge and decision-making processes, and fostering relationships for future assistance.

Author Contributions

K.C.M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing, M.P.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review and editing L.S.G.; Writing-review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The MSc Study upon which this manuscript was extracted from was funded by the South African National Research Foundation, grant number PMDS22052414075. Furthermore, the University of Limpopo’s Risk and Vulnerability Science Centre provided material and financial support during the data collection.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the analysis is referred to in this article. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Both the South African National Research Foundation and the University of Limpopo ‘s Risk and Vulnerability Science Centre are acknowledged for the financial support for carrying out the study. Anonymous reviewers are acknowledged for the feedback on the earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interest. Thus, funders had no role in the design of the study; data collection, analyses, or interpretation; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Figure A1. South African map showing 5 districts.

Figure A2. Willingness to adopt CSA in Ga-Makanye.

Figure A3. Willingness to adopt CSA in Gabaza.

Figure A4. Willingness to adopt CSA in Giyani.

References

- Mpundu, M.; Bopape, O. Analysis of Farming Contribution to Economic Growth and Poverty Alleviation in the South African Economy: A Sustainable Development Goal Approach. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2022, 12, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.; Bourgoin, C.; Martinez-Valle, A.; Läderach, P. Vulnerability of the agricultural sector to climate change: The development of a pan-tropical climate risk vulnerability assessment to inform sub-national decision making. PLoS ONE 2019, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derbile, E.K.; Yiridomoh, G.Y.; Bonye, S.Z. Mapping the vulnerability of smallholder agriculture in Africa: Vulnerability assessment of food crop farming and climate change adaptation in Ghana. Sci Direct. J. Envc. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.M.; Thornton, R.Z.; Van Asten, P.; Lipper, L. Sustainable intensification: What is its role in Climate agriculture. Curr. Res. Enviro. Sustain. 2014, 8, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlatshwayo, S.I.; Ngidi, M.S.C.; Ojo, T.O.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Slotow, R. The determinants of crop productivity and its effect on food and nutrition security in rural communities of South Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1091333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, M.; Kariuki, S. Factors Determining the Adoption of New Agricultural Technology by Small Scale Farmers in Developing Countries. JESD 2015, 6, 208–216. [Google Scholar]

- Rangotao, P.M.A. Market Access Productivity of Smallholder Maize Farmers in Lepelle Nkumpi Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Doctoral Thesis, University of Limpopo, Mankweng, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hlophe-Ginindza, S.; Mpandeli, N.S. The Role of Small-Scale Farmers in Ensuring Food Security in Africa. Food Security in Africa. IntechOpen 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, W.; Ranal, M.; Santana, D. Reference values for germination and emergence measurements. Botany 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.A.; Tougeron, K.; Gols, R.; Heinen, R.; Abarca, M. Scientific Warning on Climate Change and insects. Biol. Sci. Fac. Publ. Smith Coll. 2022, 8. Northampton, M.A. Available online: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/bio_facpubs/259.

- Kamali, B.; Abbspour, K.C.; Lehmann, A.; Wehrli, B.; Yang, h. Spatial assessment of maize physical drought vulnerability in Sub-Saharan Africa: Linking drought exposure with crop failure. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnkeni, P.N.S.; Mutengwa, C.S.; Chiduza, C.; Beyene, S.T.; Araya, T.; Mnkeni, A.P.; Eiasu, B.; Hadebe, T. Actionable guidelines for the implementation of climate smart agriculture in South Africa. Volume 2: Climate Smart Agriculture Practices. A report compiled for the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries, 2019 South Africa.

- Makwela, M.A. Determinants of smallholder maize farmers’ varietal choice: A case study of Mogalakwena Local municipality Limpopo Province, South Africa. Master’s degree, University of Limpopo, Mankweng, South Africa, 2021.

- Ayinde, O.E.; Ajewole, O.O.; Adeyemi, U.T.; Salami, M.F. Vulnerability analysis of maize farmers to climate risk in Kwara state, Nigeria. Department of Agricultural Economics and Farm Management, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria. Agrosearch 2018, 18, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Climate -Smart Agriculture: Managing Ecosystems for Sustainable Livelihoods. FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. Available online: https://fao.org/climatechange/29790-0178d452d0ca9af024aad1092d4b78b1d.

- Matimolane, S.W. Impacts of Climate Variability and Change on Maize (Zea mays) production in Makhuduthamaga Local municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa. University of Venda, 2018; pp.90-91. Available online: http://dhl.handle.net/11602/1179.

- Remilekun, A.T.; Thando, N.; Nerhene, D.; Archer, E. Integrated Assessment of the Influence of Climate Change on Current and Future Intra-annual Water Availability in the Vaal River Catchment. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2021, 12, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwambene, B.; Saria, J.A.; Jiwaji, N.T.; Pauline, N.M.; Msofe, N.K.; Mussa, K.R.; Tegeje, J.; Messo, I.; Mwangi, S.S.; Shijia, S.M.Y. Smallhoder farmers’ perception and Understanding of Climate change and Climate Smart Agriculture in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania. J. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2015, 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Torquebiau, E.C.; Rosenzweig, A.M.; Chatrchyan, N.A.; Khosla, R. Identifying climate-smart agriculture research needs. Cah. Agric. 2018, 27, 26001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazibuko, N.L. Selection and implementation of Climate Smart Agricultural Technologies: Performance and willingness for adoption and mitigation. Mit. Clim. Chang. Agric. 2018, 3, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Senyolo, M.P.; Long, T.B.; Blok, V.; Omta, O. How the characteristics of innovations impact their adoption: An exploration of climate-smart agricultural innovations in South Africa. J. C. Prod. 2018, 172, 3825–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinyolo, S. Technology adoption and household food security among rural households in South Africa: The role of improved maize varieties. Technol. Soc. 2020, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangogo, D.; Dentoni, D.; Bijman, J. Adoption of climate-smart agriculture among smallholder farmers’: Does farmer entrepreneurship matter? Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makamane, A.; Van Niekerk, J.; Loki, O.; Mdoda, L. Determinants of Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) Technologies Adoption by Smallholder Food Crop Farmers in Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality, Free State, South African Journal of Agricultural Extension (SAJAE), 2023, 51, 52–74. Available online: https://sajae.co.za/article/view/16451 (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- StatsSA. Ga-Makanye population. 2022. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=4286&id=13152.

- Kephe, P.N.; Petja, B.M.; Ayisi, K.K. Examining the role of institutional support in enhancing smallholder oilseed producers’ adaptability to climate change in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Oilseeds Fats Crops Lipids 2020, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidoo, D.C.; Boateng, S.D.; Freeman, C.K.; Anaglo, J.N. The effects of smallholder maize farmers’ perception of climate change on their adaptation strategies: The vase of two agro-ecological zones in Ghana. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, T. Mixed Methods research. Definition, Guide and Examples. Scribbr. 2022. Available online: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/mixed-methods-research/.

- Senyolo, M.P.; Long, T.B.; Omta, O. Enhancing the adoption of climate-smart technologies using public-private partnership. Int. Food Agribus. Manag, 2021, 24, 755–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpandeli, S.; Maponya, P. The use of climate forecasts information by farmers in Limpopo Province South. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diendere, A.A. Farmers’ perceptions of climate change and farm-level adaptation strategies: Evidence from Bassila in Benin. Afri. J. Agri. Resour. Econom 2019, 14, 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cragg, J.G. Some statistical models for limited dependent variables with application to the demand for durable goods. Econometrica 1971, 39, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitayezu, A.; Wale, E.; Ortmann, G. Assessing farmers’ perceptions about climate change: A double-hurdle approach. Clim.risk.manag, 2017, 17, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roco, L.; Engler, A.; Ureta, B.B.; Roas, R.J. Farm level adaptation decisions to face climate change and variability: Evidence from central Chile. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 44, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainembabazi, J.H.; Mugisha, J. The role of farming experience on the adoption of agricultural technologies: Evidence from smallholder farmers in Uganda. J. Dev. Stud. 2014, 50, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegunde, V.O.; Sibanda, M.; Obi, A. Determinants of the adoption of Climate-Smart Agricultural practices by small-scale farming households in King Cetshwayo District Municipality, South Africa. Sustainability 2020, 12, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbenyo, J.S.; Nzengya, D.M.; Mwang, S.K. Perceptions of the use of mobile phones to access reproductive health care services in Tamale, Ghana. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1026393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalu, C.A.; Mbanasor, J.A. Factors influencing the Adoption of Climate-Smart Agricultural Technologies among Root Crop Farming Households in Nigeria. FARA Res. Rep. 2023, 7, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, T. Factors influencing Farmers’ Adoption of Climate-Smart Agriculture in Rice Production in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. Asian J. Agric Dev. 2020, 17, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malila, B.P.; Kaaya, O.E.; Lusambo, L.P.; Schaffner, U.; Kilawe, C.J. Factors influencing smallholder Farmer’s willingness to adopt sustainable land management practices to control invasive plants in northern Tanzania. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 19, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awiti, A. Climate Change and Gender in Africa: A Review of Impact and Gender-Responsive Solutions. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 895950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurgat, B.K.; Lamanna, C.; Kimaro, A.; Namoi, N.; Manda, L.; Rosenstock, T.S. Adoption of Climate smart Agriculture technologies in Tanzania. Orig. Res. Artic. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mthethwa, K.N.; Ngidi, M.S.C.; Ojo, T.O.; Hlatshwayo, S.I. The Determinants of Adoption and Intensity of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices among Smallholder Maize Farmers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negera, M.; Alemu, T.; Hagos, F.; Haileslassie, A. Determinants of adoption of climate smart agricultural practices among farmers in Bale-Eco region, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, 09824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).