1. Introduction

The landscape of medical research is underscored by ever-present Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues (ELSI). As a fundamental aspect of all scientific inquiries, ELSI considerations play an indispensable role in guiding the ethical conduct, legal framework, and social implications of research endeavors. Although ELSI has firmly established its presence across the medical research spectrum [

1], its integration into the realm of newborn screening (NBS) research remains an area in which more cohesive and comprehensive implementation is needed.

For 15 years, the Newborn Screening Translational Research Network (NBSTRN) was a robust infrastructure dedicated to facilitating and expanding groundbreaking NBS research [

2]. Founded in 2008 as a key component of the Hunter Kelly Newborn Screening Program at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) [

3] through a contract with the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), NBSTRN grew into an international network involved in supporting cutting-edge research and population-based pilots. Although the NBSTRN contract was not renewed and the network was discontinued on March 25, 2024, the findings from this survey underscore the ongoing challenges in ELSI research. With rapid advancements in medical technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), genomic sequencing, and gene therapy, it is imperative to understand the current landscape of ELSI needs. This knowledge is crucial for designing more effective and relevant tools and resources for the NBS community.

The History of the NBSTRN ELSI Advantage Tool

The evidence review processes for adding new conditions to state NBS panels rely on data from pilot studies aimed at assessing the potential benefits and harms of screening. However, the consideration of ELSI aspects of NBS within such research has been limited. To help address this need, in 2019, the NBSTRN Bioethics and Legal Workgroup published a paper based on a study that focused on the ELSI concerns of various NBS stakeholders [

4]. The goal was to provide resources to help researchers integrate ELSI into NBS pilot studies. The Workgroup facilitated a series of professional and public discussions that engaged diverse NBS stakeholders to identify important existing and emerging ELSI challenges accompanying NBS. The meetings resulted in the identification of nine key ELSI questions related to (a) the types of results parents may receive through NBS and (b) the initiation and implementation of NBS for a condition within the NBS system.

The study uncovered significant insights regarding ELSI that are crucial for the array of NBS stakeholders. It emphasized the importance of accurately identifying researchers’ ELSI-related needs. The integration of the identified ELSI questions from this study has the potential to enable NBS programs to better understand the potential impact of screening for a new condition on newborns and families. This understanding can inform policy decisions aimed at maximizing benefits and minimizing potential adverse medical or social implications of screening.

Drawing from the study’s findings, the workgroup crafted the NBSTRN ELSI Advantage tool, a comprehensive resource that addressed prevalent ELSI themes pertinent to the NBSTRN community. It served to assist the NBS research community in thinking about ELSI considerations that may arise in the planning and implementation of NBS research.

ELSI Advantage included the NBS ELSI Research Repository, a curated resource that provided a summary and linked to key publications that address ELSI considerations in newborn screening research. Additionally, the ELSI Advantage included the ELSI Video Library, a central hub for accessing a variety of ELSI-related video content such as webinars, Network Meetings, the NBS Research Summit, and Monthly Pilot Calls. In the future, we anticipate the development of similar tools and resources that will continue to provide this level of support to the NBS community.

The Significance of ELSI in NBS Research

NBS programs for genetic disorders, conducted by the states, stand as a testament to one of the most triumphant public health initiatives in the U.S. Since the inception of the first successful test in the 1960s, these programs have expanded to include screenings for at least 81 conditions [

5], significantly facilitating the early intervention for newborns with genetic disorders. The recent two decades have witnessed a rapid expansion in NBS capabilities fueled by technological advancements.

The technological expansion and complexity of NBS research underscore the urgent requirement to address ELSI considerations comprehensively, starting from research conception to its culmination. This is particularly critical given the multi-dimensional scope of NBS research, which includes evaluating potential conditions for the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) [

6]. The RUSP review process reveals the intricate relationship between ELSI elements and NBS research, emphasizing that ELSI aspects are as crucial as the clinical factors. These aspects span the emotional impact on families, implications for population health, the preparedness of state programs for screening expansion, and equitable access to such screenings.

The decision-making power regarding condition inclusion within NBS programs lies with State programs, which are informed by federal RUSP guidelines. The RUSP’s rigorous review process, conducted by the ACHDNC, appraises conditions through an evidence-based lens, examining the gravity of the condition, screening validity, and treatment availability, among other pivotal factors [

7].

ELSI's complexity in NBS research calls for a consolidated approach to aid researchers. The disparate landscape of NBS research often leads to fragmented data sharing and a lack of standardized methodologies. ELSI, as an essential component of NBS, represents an area where researchers frequently encounter challenges in integrating these considerations into their pilot study frameworks.

Understanding ELSI Needs in NBS Research

Identifying ELSI needs for pilot studies will enable NBS researcher initiatives to tailor their support more effectively and ensure that ELSI considerations are seamlessly integrated into the fabric of NBS research, thereby advancing the welfare of newborns and their families. Some of the ELSI considerations that are recurring in many ESLI discussions include parental consent, parental and family wellbeing, screening panel decision-making, expansion of NBS programs, whole genome sequencing in newborns, and legal issues of public health programs.

The approach to obtaining parental consent for NBS is a controversial issue, and methods used among state NBS programs vary considerably. Researchers face a similar challenge in obtaining parental consent for NBS pilot studies [

8] The actions for which consent can be needed include the collection of a blood sample from the infant for screening, long-term storage of the sample, its use in future research, and even the sale of the sample for other purposes. Parental consent issues can go beyond getting a yes or no answer. It can include the timing of consent, active or passive consent (opt-in versus opt-out), parental understanding of what consent includes, and others.

Parental consent issues in NBS are periodically brought to the attention of the general public via news reports. For instance, a 2020 news report from California [

9] and a 2023 news report from New Jersey [

10] raise the issue of the legality of NBS dried blood spot samples being used by law enforcement. News reports such as these can foster public distrust in NBS programs and highlight the ongoing ELSI challenges facing state NBS programs and NBS researchers.

The well-being of parents and families can be affected by numerous aspects of NBS, such as the method of communicating screening results, false-positive results, the need for further diagnostic tests, and other aspects. Researchers in the U.S. and beyond continue to grapple with fully understanding the scope of these issues and comprehensively implementing best practices to address them[

11,

12]

State NBS programs determine which disorders to include in their NBS panels, and ELSI considerations are part of their decision-making process. Some of the most commonly considered ELSI aspects include [

13,

14]:

What are the potential benefits/harms of adding/excluding a condition from the state panel?

Is the disorder a significant public health problem?

Will any subpopulations be inordinately affected by the decision?

Does the state public health system have the technical and financial ability to perform the screening, diagnosis, treatment, and subsequent monitoring?

What are the potential impacts on equitable access to screening and treatment for the condition?

These and other ELSI aspects need to be examined and standardized for use by state NBS programs and in NBS pilot studies.

Expanding NBS on a state or national level requires the input of numerous stakeholders who often have differing experiences and opinions. Many of the concerns are related to potential social and ethical issues of NBS expansion, such as [

15,

16,

17]:

Screening for untreatable conditions

Screening for late-onset conditions

Screening and reporting of carrier information

Increased parental anxiety and communication burdens

Risk of a negative self-concept in the diagnosed, societal stigmatization, and insurance or employment discrimination

The suggestion of health risks in extended family members who did not consent to screening

Potential for discrimination or stigmatization due to an untreatable diagnosis or carrier status

These considerations highlight the need to include parents, clinicians, and other stakeholders in the discussions of NBS expansion policies.

The question of whether to integrate whole genome sequencing (WGS) into NBS presents ELSI and other concerns for multiple stakeholders. Parental attitudes toward WGS, and the expectations that drive their attitudes, are important aspects of the discussion [

18]. State NBS programs would have to consider the logistical, financial, and legal issues associated with adopting WGS [

18,

19]. Ethical issues such as how much information to share with parents, how that would impact parental consent, how the diagnosis of an untreatable disorder would help or harm the family, the increased burdens on clinicians, and many others [

20,

21,

22].

This brief review hints at the scale of ELSI considerations in NBS research. The need for more comprehensive guidance and support for researchers could not be clearer.

NBSTRN Bioethics and Legal Workgroup Survey: ELSI Researcher Needs

This paper describes the effort to identify NBS researchers’ ELSI needs by conducting a survey aimed at researchers involved in NBS-related studies. The purpose of the survey was to assess the ethical and legal challenges that NBS researchers face and to determine what kinds of resources they need to plan and complete their NBS studies successfully.

The survey aimed to identify the ELSI needs during the development of a research study. The survey was designed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the existing and emerging ELSI challenges associated with NBS research. The data obtained from the survey will be used to inform NBS researchers on how to address the ethical, legal, and social issues surrounding NBS research.

2. Materials and Methods

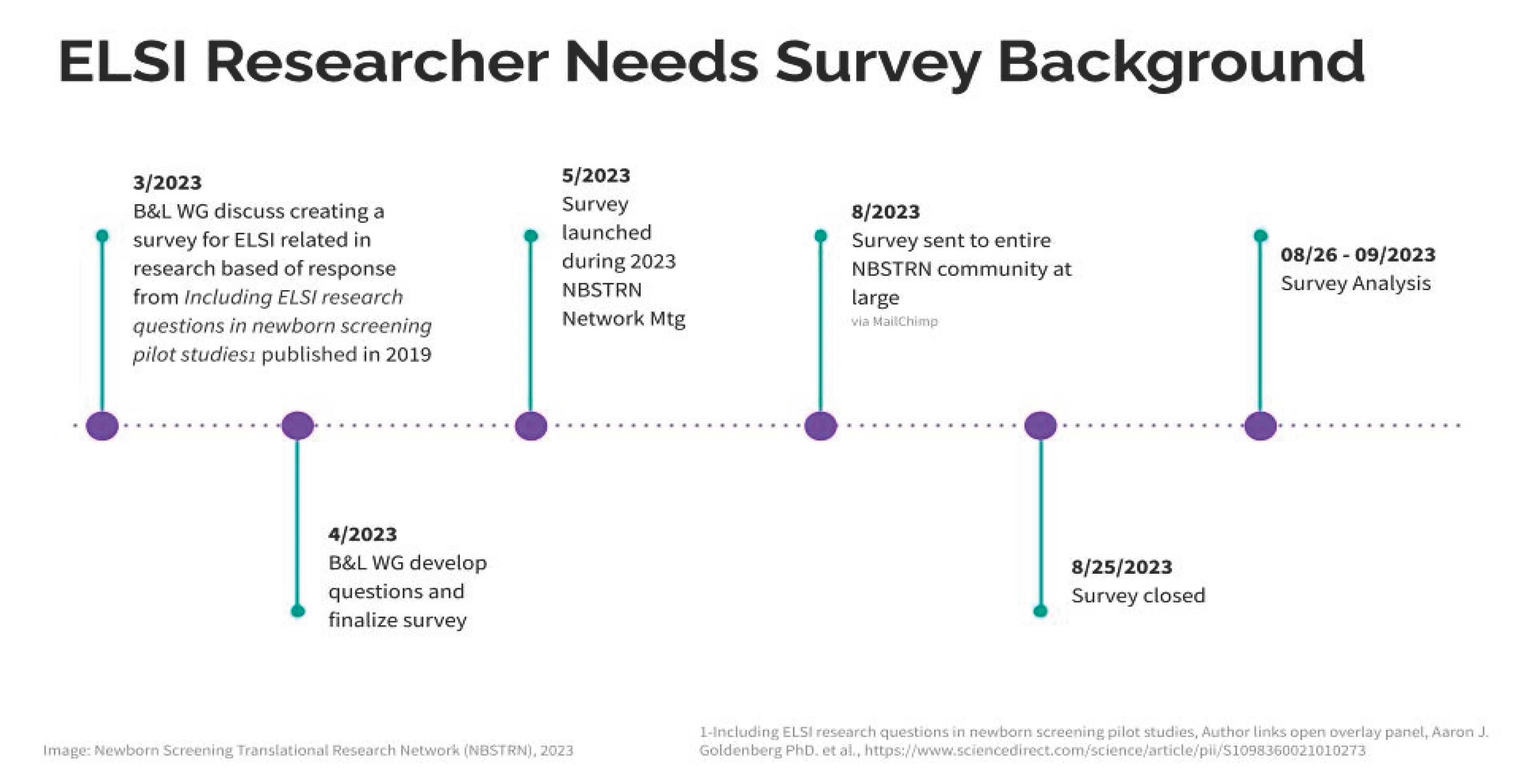

Survey Design: Initiated in March 2023, the survey was systematically developed to elucidate specific research queries unaddressed by prior literature. A series of expert workgroup meetings were conducted, followed by iterative feedback loops via email, culminating in the final instrument's construction within the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) repository [

23]. The survey was structured to include multiple-choice questions enabling participants to self-identify their role within the newborn screening research space, including their affiliation with institutions or state programs. Additionally, the survey featured open-ended questions allowing respondents to provide text responses. These open responses offered in-depth insights into participants' self-identification and perspectives on ethical, legal, and social issues pertinent to the newborn screening research space. This dual-faceted approach facilitated the collection of both quantitative data, through predetermined response options, and qualitative data, through textual elaborations, thus enriching the understanding of the stakeholder landscape within this field.

Participants: The survey targeted NBS researchers and professionals, encompassing individuals from various institutional and programmatic backgrounds actively engaged in NBS research development.

Objectives: The primary goal was to catalog the ELSI pertinent to NBS research.

Data Collection: The survey was deployed during the NBSTRN Network Meeting on May 18, 2023, and was followed by a comprehensive outreach campaign that included social media engagement. To ensure a wide reach within the NBSTRN community, broader dissemination efforts began on August 15, 2023, with the survey remaining open until August 25, 2023.

Data Analysis: Analysis of the survey responses commenced on August 26, 2023, by the NBSTRN team in conjunction with the Bioethics and Legal Workgroup co-chairs. This comprehensive review was concluded on September 25, 2023. For a visual representation of the project timeline, refer to

Figure 1.

3. Results

The NBSTRN conducted a survey aimed at researchers involved in NBS-related pilot studies. Administered by the NBSTRN Bioethics and Legal Workgroup, the survey objective was to identify the needs of researchers regarding ethical, legal, and social issues involved in newborn screening research. The survey aimed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the existing and emerging ELSI challenges associated with NBS research. The survey results will serve as valuable insights for NICHD and will function as a guide to better support NBS researchers and State NBS programs.

Eighty-eight (88) respondents completed the 13-question survey. Their responses are detailed in

Table 1.

Themes Shared by Participants

Sources of Information and Guidance (Question 5): Participants identified a variety of resources they consult when encountering legal or ethical issues in NBS research:

Self-conducted biological and legal research, including primary sources and contacts with skilled individuals

United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

Professional societies

Literature-based evidence

Geneticist colleagues

Legal documents

Newborn Screening consultants and in-house legal teams

Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at universities, and major professional groups such as the Society for Inherited Metabolic Disorders (SIMD), Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL), and ACMG

A blend of colleague advice and direct research, noting concerns about conservatism and scope creep in the field.

Usefulness of NBSTRN ELSI Resources (Question 6): Those who found the NBSTRN ELSI resources helpful provided the following insights:

ELSI resources are unique, encompassing emerging topics with contributions from diverse experts.

These resources aid in program development, partner discussions, and bolster best practices.

The resources are utilized for ensuring confidentiality in NIH-funded studies.

They offer clear and concise guidance.

The NBSTRN website is a significant resource for participants.

They serve as a foundation for constructing ELSI-compliant research proposals.

Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues Faced (Open-Ended Question): Participants reported various ethical, legal, and social challenges in their work:

Obtaining informed consent and dealing with the complexities of screening for new genetic diseases.

Applying whole genome sequencing (WGS) in primary care and as a supplement to NBS.

Managing consent in large-scale interventions and the use of residual dried blood spots (DBS).

Navigating state regulations and policies, particularly concerning research on de-identified data and genetic traits.

Addressing ethical justifications for waived consent in public health surveillance/research.

Protecting individual privacy and handling data in longitudinal studies.

Balancing research with public health mandates and population-based studies.

Observing ethical, legal, and equitable standards in public health research.

In summary, survey participants reported approaches for obtaining information on legal and ethical issues in newborn screening research, using both individual initiatives and a variety of established resources like the USPSTF, professional societies, and scientific literature. They discussed the necessity to consult with experts and in-house legal teams and to reference both academic works and professional group guidelines. Participants disclosed how they face numerous challenges including obtaining informed consent, particularly in large-scale interventions and when dealing with new genetic disease screenings and whole genome sequencing in primary care settings. Privacy concerns, the use of residual dried blood spots, and data sharing with public health officials were prominent issues. Moreover, the survey underscored the difficulties of conducting research on marginalized populations and navigating restrictive state codes and outdated NBS programs. Participants highlighted the importance of protecting patient privacy in research design and called for more consistent and ethical research practices to address these challenges.

4. Discussion and Future Efforts

The survey data suggest that while there have been notable advancements in the incorporation and evolution of Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues within the realm of NBS research, considerable work remains. A significant portion of respondents, including those from state NBS programs and researchers, underscored the necessity of ELSI considerations in their work. These findings highlight an opportunity to bolster collaborations, particularly between researchers and IRBs, to fortify the ethical planning of pilot studies.

The community's strong emphasis on privacy and informed consent reflects the collective experience within the field and indicates a conscious prioritization of these ethical tenets. Our analysis further reveals a substantial demand for additional ELSI training and education, suggesting that, while still valued, traditional literature resources may benefit from being supplemented with structured, interactive forums such as seminars and workshops.

Survey participants expressed a preference for educational formats that facilitate direct engagement and real-time discussion, revealing a potential gap in current educational offerings. Moreover, despite the utilization of the NBSTRN’s ELSI Advantage tool by 30% of the community, there exists a pronounced need for enhancing visibility and access to such resources.

Future investments in ELSI tools and resources as identified in the survey could be addressed through several funding initiatives:

ELSI Resource Development Grants: These grants would focus on creating accessible, patient-centric resources that address the burgeoning ELSI challenges identified by the NBS research community. Emphasis would be placed on privacy and informed consent tools, catering to the nuanced requirements of rare disease research.

Collaborative Education Programs: With an expressed preference for interactive and structured learning, funding could support the establishment of seminars and workshops. These would serve to disseminate current ELSI practices and foster a collaborative learning environment, integrating patient advocacy groups in the educational design to ensure patient-relevant outcomes.

Digital Engagement Platforms: Investments could be allocated towards developing digital platforms for ELSI education and discussion. These platforms would encourage cross-disciplinary collaboration and facilitate real-time dialogue among researchers, clinicians, and patient groups.

Ethics Consultation Services: Recognizing the need for ongoing support in navigating ethical complexities, programs such as the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN) could establish a consultative service within its consortia. This service would be tasked with providing expert advice on ethical considerations in clinical trial design and implementation, especially for rare diseases where the ethical landscape can be particularly complex.

Legal and Regulatory Navigation Tools: Considering the diverse regulatory environments encountered across research sites, funding could be targeted to the development of tools that aid rare disease researchers in understanding and complying with local and international regulations, thereby ensuring the ethical conduct of rare disease research.

Data Sharing and Privacy Initiatives: With big data playing an increasingly critical role in research, funding could support the creation of protocols and best practices that ensure the ethical use and sharing of data, while respecting patient privacy and the specific confidentiality concerns associated with rare diseases in the newborn screening space.

The proposed initiatives for ELSI resource funding, collaborative education programs, digital engagement platforms, ethics consultation services, legal navigation tools, and data sharing protocols are not just investments in NBS research infrastructure; they are investments in a future where rare disease research is conducted with the highest ethical standards, ensuring respect for participant privacy and informed consent. These measures will facilitate the advancement of NBS research from its current state towards a future where effective treatments for patients with rare diseases can be developed more efficiently and ethically.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.U. and A.B.; formal analysis, Y.U.; data curation, Y.U.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.U.; writing—review and editing, Y.U, K.C., A.B.; visualization, Y.U.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is funded in whole with Federal funds from the NICHD, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN275201800005C.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available within this article.

Acknowledgments

This paper and the research it presents could not have been accomplished without the exceptional support of the NBSTRN Bioethics and Legal Workgroup. Special thanks are due to Flavia Chen, MPH; Ed Goldman, JD, Co-Chair; Aaron J. Goldenberg, PhD, MPH, Co-Chair; Ingrid Holm, MD, MPH, Co-Chair; and Stacey Pereira, PhD. Their contributions were vital to the development of the ELSI Researcher Needs Survey, and their invaluable comments and feedback greatly enriched the reporting, results, and analysis of the survey data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ELSIhub. Available online at https://elsihub.org/. (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Newborn Screening Translational Research Network (NBSTRN. Available online at https://nbstrn.org/. (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC). Available online at https://www.hrsa.gov/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders. (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Goldenberg, A.J.; et al. Including ELSI research questions in newborn screening pilot studies. Genet. Med. : Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2019, 21, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newborn Screening in Your State. Available online at https://newbornscreening.hrsa.gov/your-state. (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP). Available online at https://www.hrsa.gov/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders/rusp. (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Condition Nomination and Review. Available online at https://www.hrsa.gov/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders/condition-nomination. (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Botkin, J.R.; et al. Parental permission for pilot newborn screening research: Guidelines from the NBSTRN. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e410–e417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, J. 2020. CBS13 Investigates: CA Still Storing Newborn DNA Without Consent. Golden State Killer Case Raising New Concerns. 13 CBS Sacramento. https://sacramento.cbslocal.com/2020/12/07/newborn-dnacalifornia-

consent-gsk-killer/.

- DiFilippo, D. 2023. Judge orders state to release information about police use of baby blood spots, /: Monitor. . https, 4 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chudleigh, J.; et al. Rethinking Strategies for Positive Newborn Screening Result (NBS+) Delivery (ReSPoND): A process evaluation of co-designing interventions to minimize impact on parental emotional well-being and stress. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2019, 5, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.; et al. The impact of false-positive newborn screening results on families: A qualitative study. Genet Med 2012, 14, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esquerda, M.; et al. Ethical questions concerning newborn genetic screening. Clinical Genetics 2020, 99, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therrell, B.L., Jr. Ethical, legal, and social issues in newborn screening in the United States. The Southeast Asian journal of tropical medicine and public health 2003, 34 Suppl 3, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, L.; et al. Parental Attitudes Toward Ethical and Social Issues Surrounding the Expansion of Newborn Screening Using New Technologies. Public Health Genomics 2011, 14, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhondt, J.L. Expanded newborn screening: Social and ethical issues. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 2010, 33, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, D.B.; et al. Ethical, legal, and social concerns about expanded newborn screening: Fragile X syndrome as a prototype for emerging issues. Pediatrics 2008, 121, e693–e704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, A. , Dodson, D., Davis, M. et al. Parents’ interest in whole-genome sequencing of newborns. Genet Med 2014, 16, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.S.; Smith, M.E. . Whole-Genome Screening of Newborns? The Constitutional Boundaries of State Newborn Screening Programs. Pediatrics 2016, 137 (Suppl 1), S8–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg AJ, Sharp RR. 2012. The Ethical Hazards and Programmatic Challenges of Genomic Newborn Screening. JAMA. 2012, 307, 461–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, T. 23 and Baby. Nature 2019, 576, S8–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White-Corey, Shelley; et al. 2021. Ethical implications of next-generation sequencing and the future of newborn screening. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2021, 33, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap) Repository. Available online at https://www.project-redcap.org/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).