1. Introduction

Calcium is an essential element of human physiology. It enhances bone density, muscle contraction, signal transmission, and vascular tone [

1]. Adequate calcium intake is crucially involved in ensuring bone health, especially in postmenopausal women [

2,

3]. Low dietary calcium intake is associated with many adverse effects, including osteoporosis and fracture risk. However, high calcium intake has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Since the 2008 Auckland Calcium Study, there have been concerns about the adverse effects of high-calcium supplements with respect to CVD [

4], with subsequent studies demonstrating that high calcium intake might increase the risk of CVD [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Contrastingly, other studies have shown that neither dietary or supplemental calcium intake was associated with death caused by CVD, heart disease, or cerebrovascular disease among women aged >50 years [

10,

11]. Therefore, it remains unclear whether calcium intake is associated with the risk of CVD. Numerous clinical studies have reported a positive effect of calcium intake on CVD, with increased dietary calcium intake being associated with a decreased risk of CVD [

12,

13]. A meta-analysis in 2020 emphasized that dietary calcium intake did not increase the risk of CVD, while supplemental calcium intake increased the risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and CVD [

14].

Based on the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the United States Institute of Medicine (IOM), the recommended dietary allowance is 1000 mg/day for premenopausal women and 1200 mg/day for women aged >50 years [

15,

16]. However, calcium consumption in Korean women has been shown to be much lower than recommended. A large prospective Korean cohort study reported that the mean daily calcium intake was ≈500 mg/day [

11]. Therefore, it is important to evaluate cardiovascular risk according to calcium intake in the Korean female population. Accordingly, this study aimed to evaluate the association between daily calcium intake and CVD risk in postmenopausal Korean women using data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The KNHANES was conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, recruiting ≈10,000 representative noninstitutionalized civilians aged ≥1 year since 1998. In this study, we analyzed survey data collected from 2005 to 2021. This survey was conducted at 3-year intervals until 2007, and annually henceforth. The survey included a health interview, nutrition examination, and health examination (physical measurements, laboratory test results, bone mineral density, and body mass index [BMI]). Trained interviewers conducted health interviews and health examinations during home visits, and the surveys were completed by the participants or through an interview format. Subsequently, a trained dietitian conducted nutritional surveys using a 24-h dietary recall and a food frequency questionnaire.

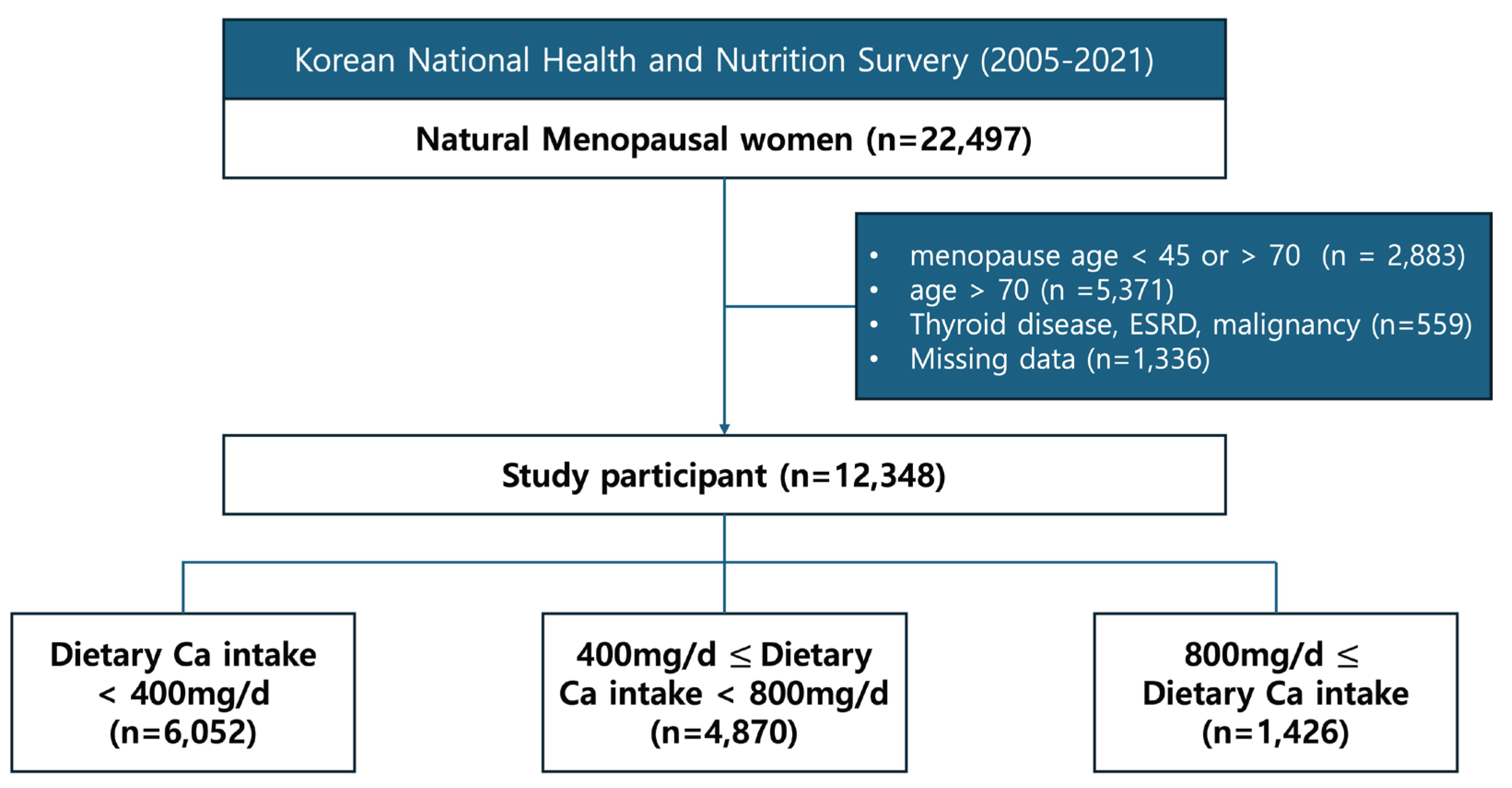

Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the participants. We excluded women with menopause due to iatrogenic causes, including bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy. Among 22,497 women who had natural menopause, we excluded 2883 women who had menopause before and after the age of 45 and 70 years, respectively. Additionally, we excluded 5,371 women aged > 70 years and 1,336 women with missing data regarding calcium intake. Finally, we excluded 559 women with thyroid dysfunction, end-stage renal disease, and malignancy, which may involve altered calcium metabolism. Ultimately, 12,348 participants were included in this study.

2.2. Data Collection

Clinical data were collected from standardized questionnaires, including the participants’ menarche age, menopausal age, smoking history, exercise frequency, alcohol consumption, history of hormone replacement therapy, history of oral contraceptive use, history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, education, income, and daily calcium intake. Further, self-reported medical history, including history of stroke, angina, MI, was obtained. Exercise was defined as physical activity characterized by moderate or vigorous exercise for >20 minutes. High alcohol intake was defined by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare as drinking more than seven servings (male) or five servings (female) of alcohol more than twice a week.

Daily calcium intake was determined as the sum of the amounts of calcium contained in the foods consumed individually per day. Daily energy and nutrient intake were calculated using the Korean Food Composition Database of the Rural Development Administration. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine (approval no. 4-2023-1382).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous and categorical variables are presented as weighted mean (± standard error) and weighted row percent (standard error), respectively. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared test. Analysis of variance was used to compare baseline characteristics according to dietary calcium levels. Logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the odds ratios (ORs) among the different calcium intake groups. The SURVEYFREQ, SURVEYMEANS, and SURVEYREG SURVEYLOGISTIC were used to calculate the statistics. All statistical analyses and visualizations were performed using R (version 4.2.1; The R Foundation,

www.R-project.org) and SAS 9.4 version (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was set at a two-sided P-value <0.05.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of the study participants. Among 12,348 included participants, 6052, 4870, and 1426 women who had daily calcium intake <400 mg/day, 400–800 mg/day, and >800 mg/day, respectively. Only 338 (2.7%) women consumed more calcium per day than the intake recommended by the North American Menopause Society, which is 1200 mg/day for women aged >50 years. Three groups were established based on the daily dietary calcium intake: <400 mg, 400–800 mg, and >800 mg. The risks of CVD, stroke, angina, and MI were assessed in each group. Subgroup analysis was performed according to the postmenopausal duration (≤10 vs. >10 postmenopausal years).

The average age of women showed a trend of decreasing with increasing dietary calcium intake as follows: 59.58 (±0.1), 58.76 (±0.1), and 58.71 (±0.18) years for daily calcium intake <400 mg/day, 400~800 mg/day, and >800 mg/day, respectively. The ages at menopause showed no significant among-group differences (50.73 [±0.05], 50.79 [±0.05], and 50.78 [±0.09] years for the corresponding groups [p=0.43]).

Regarding socioeconomic factors, daily calcium intake was positively correlated with education level, income level, and urban residence. Moreover, daily calcium intake was negatively correlated with BMI and the prevalence of comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia. Moreover, dyslipidemia and insulin use were less prevalent in populations with high calcium intake. However, oral contraceptive use did not significantly differ among the groups. Women with calcium intake of 400–800 mg/day had the highest percentage of hormonal therapy compared with the other calcium intake groups. Regarding lifestyle parameters, higher daily calcium intake was associated with less excessive alcohol consumption and more frequent physical exercise; however, the daily calcium intake was not associated with smoking history.

Logistic regression analysis was performed to minimize the effects of differences in baseline characteristics. Model 1 was adjusted for age, while Model 2 was adjusted for age, menopausal age, income, urban area, education, insulin usage, BMI, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, high alcohol intake, smoking, exercise, oral contraceptive use, and hormonal therapy usage.

Table 2 shows the association of daily calcium intake with the risk of CVD in all women (age: 45–70 years). CVDs were classified as stroke, angina, and MI. In the unadjusted analysis, in women with daily calcium intake of 400–800 mg, there were significantly decreased ORs for all CVD (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.61–0.92) and angina (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.33–0.99). Additionally, in women with daily calcium intake > 800 mg, there were significantly decreased ORs for stroke (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.35–0.92) and angina (OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.1–0.91). However, the adjusted OR showed that calcium intake at any level did not affect the risk of CVD events in women aged 45¬–70 years.

Table 3 depicts the risk of CVD in each daily calcium intake group for women with <10 years of postmenopausal status. In Model 2, women with daily calcium intake >400 and ≤800 mg showed non-significantly decreased ORs for all CVDs (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.49¬–1.36). In women with daily calcium intake >800 mg, there was a non-significantly decreased OR for all CVDs (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 0.87–3.76). Calcium intake at any level did not affect the risk of CVD events in women who had been postmenopausal for <10 years.

Table 4 shows the risk of CVD in each daily calcium intake group for women with >10 years of postmenopausal status. In women with a daily calcium intake of >800 mg, the unadjusted model showed a reduced risk for all CVDs (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.26–0.8), stroke (OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.2–0.78), and MI (OR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.23–0.98). Adjusted multivariable analysis revealed significantly decreased risks of all CVDs (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.11–0.64), stroke (OR, 0.06; 95% CI, 0.01-0.42), and MI (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.11-0.64) with daily calcium intake >800 mg.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that women with menopausal duration >10 years, but not ≤10 years, experienced a reduced risk of CVD events, stroke, and MI when their daily calcium intake exceeded 800 mg. Our findings are consistent with previous reports that increased dietary calcium intake was associated with decreased CVD risk. A prospective cohort study of 74245 women aged 30–55 years in the Nurses’ Health Study reported a negative correlation between calcium consumption and CVD risk. After 24 years of follow-up, there was a decreased risk of coronary artery disease in women with a daily calcium intake >1000 mg [

17]. A Korean study reported that in women aged >50 years, increased dietary calcium consumption was associated with a decreased CVD risk [

13], especially in women without obesity [

12]. Other studies have reported that neither dietary nor supplemental calcium intake was associated with death caused by CVD, heart disease, or cerebrovascular disease in women aged >50 years [

10,

11]. A meta-analysis in 2020 emphasized that dietary calcium intake did not increase the risk of CVD but that calcium supplementation might increase the risk of MI and CVD [

14].

Several mechanisms may explain the positive effect of appropriate calcium intake on the risk of CVD among women who have been menopausal for >10 years. Estrogen is crucially involved in regulating intracellular calcium homeostasis [

7]. By regulating the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and limiting calcium overload, it prevents cardiovascular diseases caused by elevated calcium levels in women. Additionally, it decreases the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases associated with cardiac diastolic dysfunction in postmenopausal women. Long-term estrogen withdrawal alters calcium homeostasis-related proteins (L-type Ca2+ channel, ryanodine receptor, sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, and sodium-calcium exchanger) in cardiomyocytes [

18]. Changes in the calcium homeostasis cycle are major risk factors for cardiac systolic and diastolic dysfunction as well as the mechanism of CVD. The effect of calcium on CVD seems to vary across different menopause stages. Moreover, estrogen and calcium contribute to cholesterol metabolism. In postmenopausal women, decreased estradiol levels result in increased serum cholesterol concentration, metabolic syndrome, carotid intima-media thickness, and CVD [

7].

The optimal dietary calcium intake for a positive effect on cardiovascular outcomes remains controversial. Several studies have reported the harmful effects of high calcium intake on CVD in men, premenopausal women, and menopausal women [

4,

5,

8]. We found that a daily calcium intake >800 mg was associated with reduced CVD in women who had been menopausal for >10 years. However, we could not determine the recommended upper limit of calcium intake. In our study, only 2.7% of the women had a daily calcium intake >1200 mg, with no significant association with CVD events. Since there were relatively few participants with a calcium intake >1200 mg/day, we did not analyze this subgroup. The recommended dietary calcium intake varies across health associations and countries. Similar to our study, a Swedish prospective longitudinal cohort study recommended that women aged >50 years should take 800 mg of calcium daily [

8]. Moreover, adverse outcomes did not increase with a total calcium intake of 600–1400 mg/d. Daily calcium intake >1400 mg was associated with the risk of CVD and ischemic heart disease, but not stroke. Based on the AACE and IOM, the recommended dietary allowance is 1000 mg/day for premenopausal women and 1200 mg/day for women aged >50 years [

15,

16]. The National Osteoporosis Guidelines Group in the UK recommends a reference calcium intake of 700 mg/day [

19]. The European Menopause and Andropause Society recommends a daily intake of elemental calcium of 700–1200 mg [

2]. Based on these recommendations and our findings, we suggest that the modest calcium intake for Korean women should be 800–1200 mg/day and not exceed 1400 mg/day.

This study has several strengths, including its large sample size and numerous cardiovascular events. Additionally, this study was based on data from the KNHANES, which suggests that the study participants represent the general population of Korean citizens. Finally, we adjusted for several important confounding factors related to CVD risk, including age, menopausal age, insulin use, BMI, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, high alcohol intake, smoking, exercise, oral contraceptive use, and hormonal therapy use.

However, this study has several limitations. First, all medical histories and calcium intake were self-reported, which may have led to recall bias. However, other studies have also used the food frequency questionnaire to assess daily calcium intake [

5,

10,

17], with a recent review demonstrating that it is a valid method for assessing dietary mineral intake, especially calcium intake [

8]. Second, a self-reported history of angina can be further divided into unstable, stable, and variant angina. The pathophysiology of these angina types differs; accordingly, it is difficult to assume that all patients with angina have coronary artery disease. Therefore, further studies with accurate diagnoses rather than self-reported histories are warranted. Finally, calcium intake was calculated based on the dietary consumption of calcium-containing foods, without considering the supplemental calcium intake. Calcium supplements might increase the risk of CVD [

14], with supplementary calcium intake >1000 mg/day being reported to be associated with CVD [

20]. A report based on the 2015 KNHANES showed that although the total calcium intake from food among female participants was 467.5 mg, the total calcium intake from food and supplements was 540.1 mg [

21]. Accordingly, dietary calcium supplementation may not account for major changes in the total daily calcium intake, and thus may have had minimal effects in this study.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings suggest that appropriate dietary calcium intake (> 800 mg/day) decreases the prevalence of cardiovascular events in women who have been menopausal for >10 years.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L., C.T., S.S.; methodology, HR.K.; software, HR.K.; validation, E.C., J.B.; formal analysis, HR.K.; investigation, J.L., C.T.; resources, HY.K., B.Y., S.S.; data curation, J.K., C.T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L., C.T.; writing—review and editing, J.L., E.C., J.B.; visualization, C.T.; supervision, HY.K., B.Y., S.K.S.; project administration, S.K.S.; funding acquisition, S.K.S.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by an MEF Fellowship conducted as part of the Education and Research Capacity Building Project at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, implemented by the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) in 2023. (No. 2021-00020-3).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine (approval no. 4-2023-1382).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We analyzed survey data from Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) collected from 2005 to 2021 conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Data are publicly available through the KNHANES website (

http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Yonsei University College of Medicine for their generous support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Michos, E.D.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Heravi, A.S.; Appel, L.J. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation and implications for cardiovascular health. 2021, 77, 437–449. 2021, 77, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cano, A.; Chedraui, P.; Goulis, D.G.; Lopes, P.; Mishra, G.; Mueck, A.; et al. Calcium for the Prevention of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: EMAS Clinical Guide. Maturitas 2018, 107, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.K.; Chon, S.J.; Noe, E.B.; Roh, Y.H.; Yun, B.H.; Cho, S.; et al. Association of dietary calcium intake with metabolic syndrome and bone mineral density among the Korean population: KNHANES 2008-2011. Osteoporosis International: A journal established as a result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2017, 28, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolland, M.J.; Barber, P.A.; Doughty, R.N.; Mason, B.; Horne, A.; Ames, R.; et al. Vascular events in healthy older women receiving calcium supplementation: a randomized controlled trial. software (Clinical Research). 2008, 336, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.J.; Kruszka, B.; Delaney, J.A.; He, K.; Burke, G.L.; Alonso, A.; et al. Calcium Intake From Diet and Supplements and the Risk of Coronary Artery Calcification and its Progression Among Older Adults: 10-Year Follow-up of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Journal of the American Heart Association. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freaney, P.M.; Petito, L.; Colangelo, L.A.; Lewis, C.E.; Schreiner, P.J.; Terry, J.G.; et al. Association between Premature Menopause With Coronary Artery Calcium: The CARDIA Study. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2021, 14, e012959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Na, L.; Li, Y.; Gong, L.; Yuan, F.; Niu, Y.; et al. Long-term calcium supplementation may have adverse effects on serum cholesterol and carotid intima-media thickness in postmenopausal women: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. American Journal of Clin Nutrition. 2013, 98, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaëlsson, K.; Melhus, H.; Warensjö Lemming, E.; Wolk, A.; Byberg, L. Long term calcium intake and rates of all cause and cardiovascular mortality: community based prospective longitudinal cohort study. software (Clinical Research). 2013, 346, f228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, I.R.; Birstow, S.M.; Bolland, M.J. Calcium and cardiovascular diseases. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea). 2017, 32, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Q.; Murphy, R.A.; Houston, D.K.; Harris, T.B.; Chow, W.H. Dietary and supplemental calcium intake and cardiovascular disease mortality: the National Institutes of Health-AARP diet and health study. JAMA internal medicine. 2013, 173, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.Y.; Cho, H.J.; Lee, J.E. Lower Dietary Calcium Intake is Associated with a Higher Risk of Mortality in Korean Adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2022, 122, 2072–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, M.J.; Jang, J.Y.; Park, K. Association between dietary calcium intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease among Korean adults. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2020, 74, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Hong, A.R.; Cho, N.H.; Shin, C.S. Dietary calcium intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and fracture in a population with low calcium intake. American Journal of Clin Nutrition. 2017, 106, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Shi, X.; Xia, H.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Pan, D.; et al. Dietary calcium intake and calcium supplementation are associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies and randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2020, 39, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, P.M.; Petak, S.M.; Binkley, N.; Diab, D.L.; Eldeiry, L.S.; Farooki, A.; et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists/american college of endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2020 update. Endocrine practice: official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 2020, 26 (Suppl 1), 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D, Calcium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, editors. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright © 2011, National Academy of Sciences.; 2011.

- Paik, J.M.; Curhan, G.C.; Sun, Q.; Rexrode, K.M.; Manson, J.E.; Rimm, E.B.; et al. Calcium supplement intake and risk of cardiovascular disease in women. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2014, 25, 2047–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, L.; Machuki, J.O.; Wu, Q.; Shi, M.; Fu, L.; Adekunle, A.O.; et al. Estrogen and calcium handling proteins: new discoveries and mechanisms in cardiovascular diseases. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2020, 318, H820–H829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregson, C.L.; Armstrong, D.J.; Bowden, J.; Cooper, C.; Edwards, J.; Gittoes, N.J.L.; et al. UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Archives of osteoporosis. 2022, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myung, S.K.; Kim, H.B.; Lee, Y.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Oh, S.W. Calcium Supplements and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, L.N.; Yang, J.E.; Kweon, S.H.; Oh, K.W. Dietary supplement intake based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2015. Public Weekly Health Report. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).