Submitted:

18 March 2024

Posted:

19 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

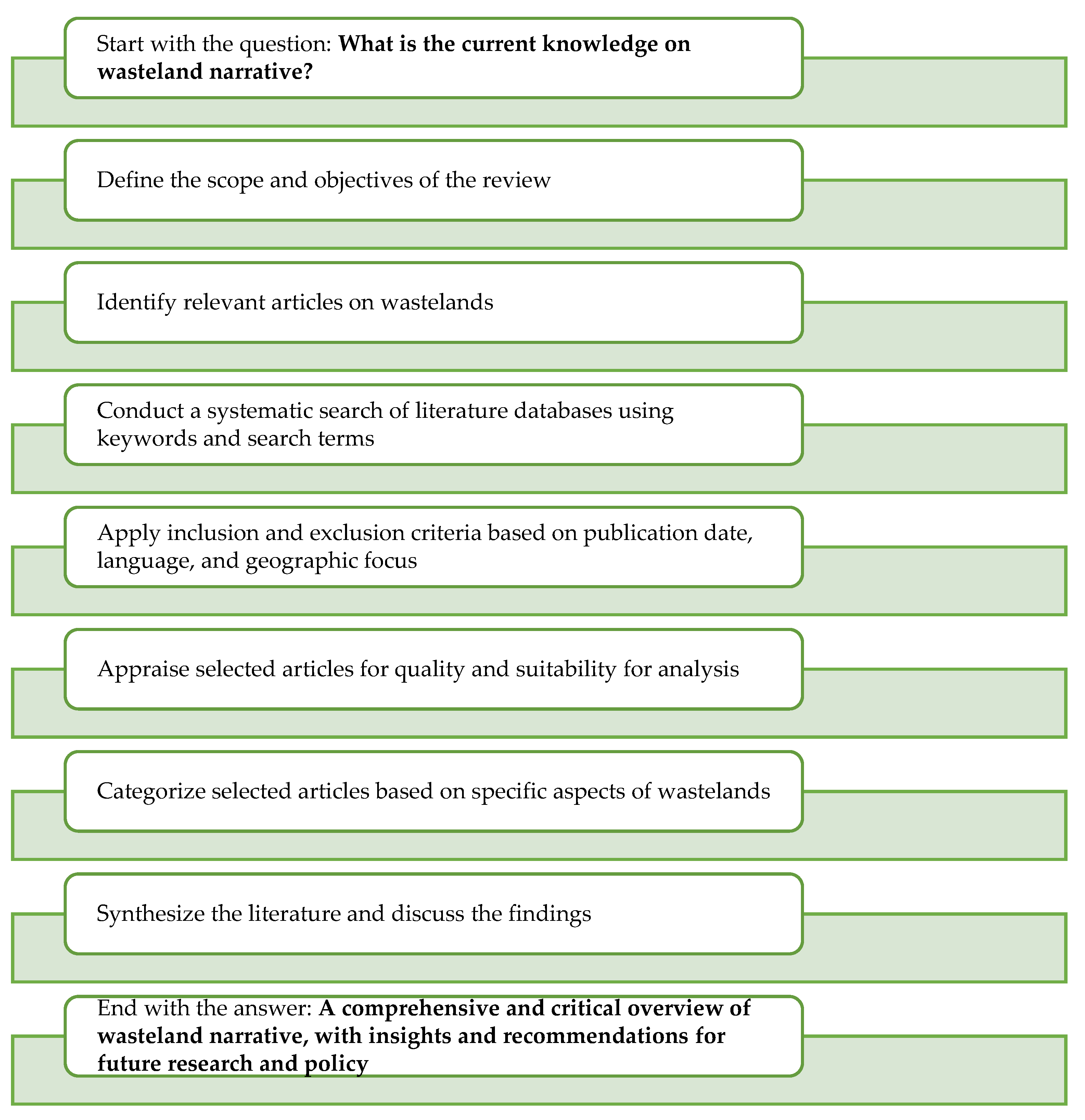

- 1)

- Initiation: The process starts with defining the scope and objectives of the review to guide the search for relevant articles on wastelands.

- 2)

- Database Search: A systematic search of literature databases is conducted, using keywords and search terms related to wastelands to ensure comprehensive coverage of the topic.

- 3)

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Articles are subjected to inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine their relevance to the review. Criteria such as publication date, language (English), and geographic focus are applied to filter out irrelevant or duplicate publications (Brocke et al., 2009). Selected articles are further appraised for their quality and suitability for analysis, assessing their methodological rigor, relevance, and reliability.

- 4)

- Categorization of Selected Articles: Selected articles are categorized based on specific aspects of wastelands to facilitate a comprehensive synthesis of the literature. Categories include decade-wise, discipline-wise, and region-wise classifications, among others.

-

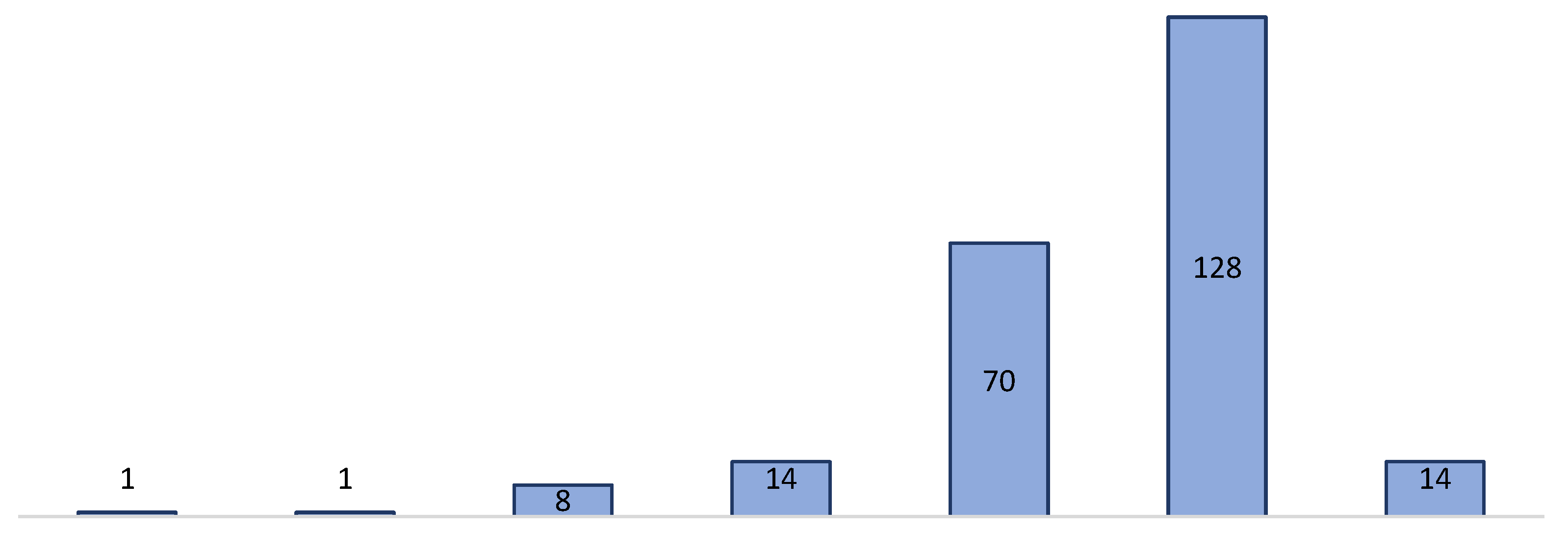

Decade-wise Published Literature: Literature is divided into seven decades from the 1960s to the present, revealing a swift increase in academic publications on wasteland-related topics from the 2000s onwards, peaking during 2010 to 2019 (see Figure 2).

-

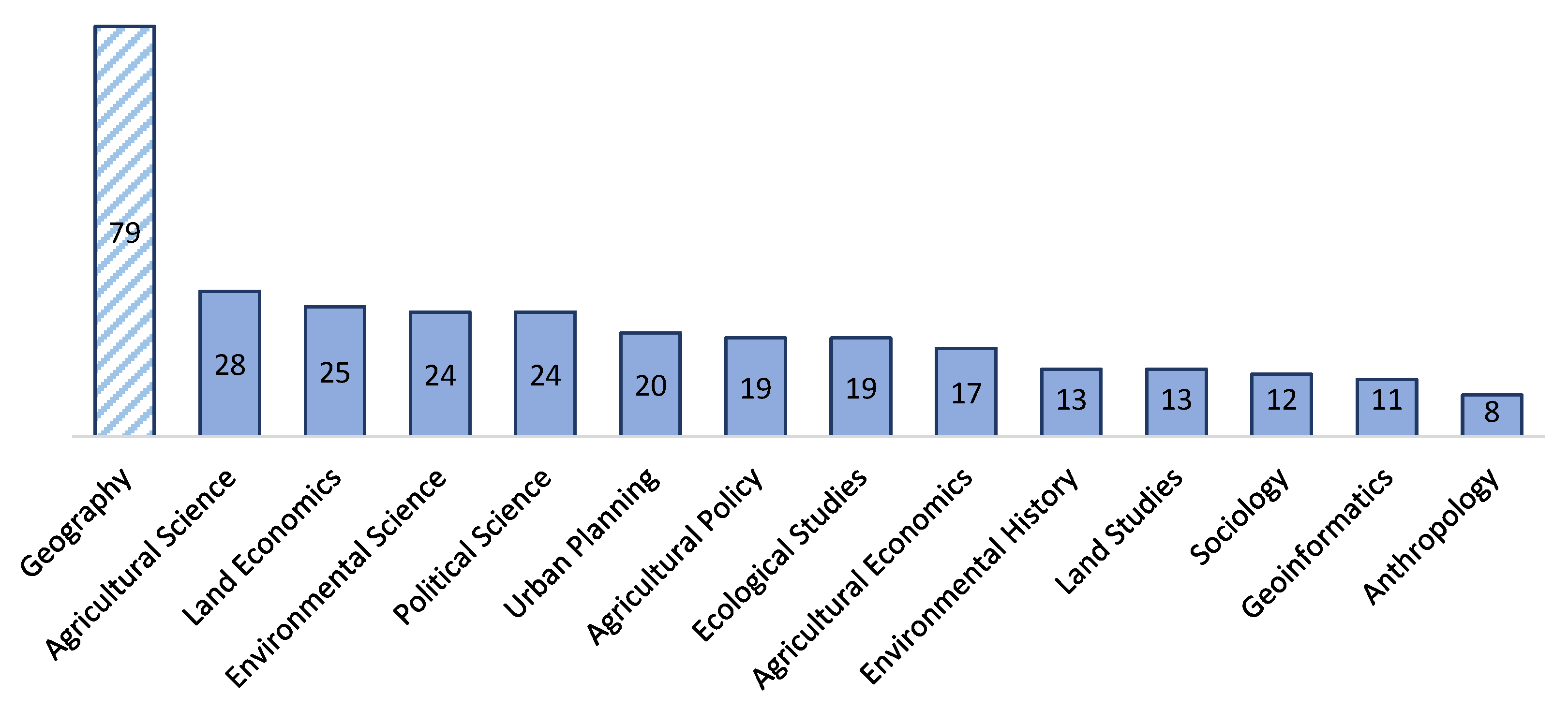

Discipline-wise Published Literature: Literature is classified based on discipline, with some pieces potentially assigned to multiple disciplines. For example, literature focusing on geospatial techniques and agricultural science may overlap (see Figure 3).

-

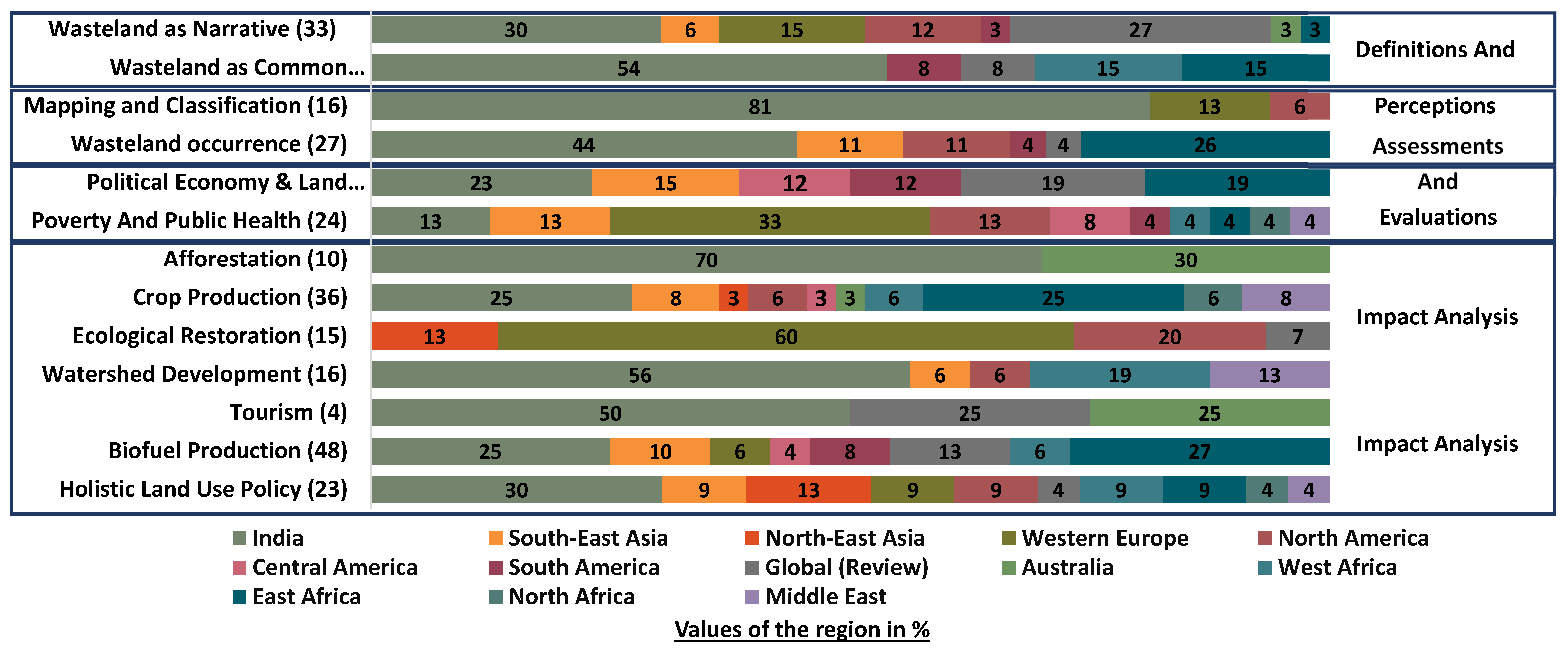

Region-wise Published Literature: Literature is classified regionally, with some pieces potentially counted more than once if they cover multiple regional case studies (see Figure 4). Regional perspectives are further overlaid onto issues associated with wasteland (see Figure 5), with a specific focus on the Indian context.Figure 4. Region-wise academic published literature on Wasteland.

- 2.1.

-

Structure of the Review: Based on the meta-analysis mentioned above, we structure our narrative review into two major parts:

- 2.1.1.

-

Global Overview of Wastelands: To recognize the global picture of wasteland narrative, we focus on two particular elements: the meaning and the policies associated with wasteland. This includes:

- −

- Understanding how the term ‘waste’ is used in the global north and the global south (Paul et al., 2015).

- −

- Examining the basic differences of wasteland narrative in the global north and south, particularly in their geo-physical setup, causes of wasteland formation, and its association with livelihood. We also compare the differences of wasteland-aided policies (Sylvester et al., 2013).

- −

- The primary purpose of this global overview of wasteland is to provide the readers with a comprehensive background for understanding the current knowledge on wasteland narrative and then overlay it with a case-specific study in the Indian scenario. This deductive way of narrative review may serve as a viable policy-making approach on wasteland, where planners can get the explicit details of wasteland in the Indian case by incorporating the holistic global overview as well.

- 2.1.2.

-

Case-Specific Study in India: For the Indian case study, we aim to recapitulate what is known, and we do so by creating and using themes and grouping categories derived from the literature. The grouping categories of literature are primarily based on three consecutive themes of wasteland narratives:

- −

-

Understanding the multidimensional perspective of wasteland: We follow these steps to highlight different perspectives of wasteland in the Indian scenario:

- First, out of the total 94 literatures of wasteland in the Indian scenario, we set aside 18 literatures that explicitly define the meaning of wasteland as a finite concept.

- Second, we group the 18 definitions into a chronological order to represent the decade-wise shifting in perspective in the wasteland narrative from 1960s to present (Table A1, Appendix A).

- Third, based on the available 18 definitions, we further extract four individual interlinking perspectives: Agro-economic perspective, Bio-physical perspective, Property right perspective, and Political perspective of wasteland in the Indian context.

- −

- Emphasizing different categories of wasteland: Although a number of different national organizations (Table A2, Appendix B), such as Indian Council of Agriculture Research and National Wasteland Development Board, have already classified different categories of wasteland, these classifications are very much integrated with the geo-physical aspect rather than integrating the socio-economic and political aspects of wasteland category. Therefore, we further categorize different wasteland classes in an interdisciplinary mode, where the bases of wasteland category are further classified into four types and 15 sub-types (Table A3, Appendix C).

- −

-

Examining the policy associated with wasteland: To evaluate the wasteland-aided policy, we follow two consecutive steps that endorse the deductive way of interpretation:

- First, we classify the wasteland and land revenue system in the colonial era, which depicts the historical background of wasteland in India.

- Second, we further reclassify the post-colonial wasteland policy into three segments depending on the approaches of wasteland-aided policies (Table A5, Appendix E).

- After discussing the general overview of wasteland in the entire country, we further obtain region/state-specific wasteland-aided developmental approaches (Table A6, Appendix F).

3. Understanding the Concept of Wasteland in Global Context

- In the global south, wastelands are predominant in the rural sector, whereas planners emphasize urban wastelands in the global north.

- In the global south, the formation of wasteland and regional marginality are associated with each other. In the global north, the relation between wasteland and regional marginalization is not unambiguously connected.

- In the global south, the development approaches to wasteland are significantly overwhelmed with economic prosperity (through energy security and job creation) and ecological restoration. Whereas in the context of the global north, the re-establishment of wasteland is predominantly emphasized by ecological restoration.

- In the global south, land use policy for wasteland regeneration is associated with unequal power relations and land grabs, which is not signified in the global north.

4. Understanding Wasteland in Indian Context

4.1. Perspectives on Defining Wasteland in India:

4.2. Classification of Wasteland:

- 1)

- Wasteland’s causal factors:

- a)

- Wasteland due to natural factors: Wastelands form due to natural inputs like wind and water erosion or natural degradation. For example, rocky outcrops, gullied / ravenous land, glaciated areas, and sandy areas naturally produce where human economic activity may not be possible.

- b)

-

Wasteland due to anthropogenic factors: The socio-cultural, economic, and political processes are responsible for creating marginal lands, which can be recognized as anthropogenic Wasteland. We can classify anthropogenic Wasteland into three categories-

- (i)

- Socio-cultural Wasteland: This type of Wasteland is mainly formed by socio-cultural factors [154], such as land fragmentation due to family disputes causes social Wasteland.

- (ii)

- Political Wasteland: The political fabrication creates a solid foundation of disputes and obstruction of development policy. The formation of a political Wasteland is the product of the disputes among the local farmers, private enterprises, and local government. In this regard, Singur, in the Hooghly district of West Bengal, India, sets a perfect example of the formation of politics. The state government announces the promotion of Tata Motors Company for the ‘Nano’ factory (Small Car factory) in Singur, some 30 km NE of Kolkata city. Nevertheless, the policy’s central issue was selecting agricultural land, which was one of the prime agro-based regions in the district and for the state. As a result, the opposition party raised agitation against the land acquisition with the help of the local farmers. As a result, Tata Motors Group left West Bengal and chose Gujarat state for their Nano factory [155]. The result ended with the origin of wastelands in Singur [156], where the disputes have made the land unfit for agriculture and industry.

- (iii)

- Wasteland due to economic activity: Mining, other industrial activities, and ‘jhum’ farming reduce soil fertility [157]. In India, mining wastelands are predominant, whereas chemically contaminated land is another category of Wasteland, sometimes recognized as Brownfield land in European countries.

- 2)

- Wasteland’s potential usability

- a)

- Cultivable Wasteland: Cultivable wastelands are the specific group of Wastelands suitable for reuse through effective management. For example, salt-affected land, gullied /ravenous land, water-logged or marshy land, upland with or without scrub, Jhum or forest blank and sandy areas are the categories of cultivable or utilizable Wasteland. Some types of cultivable Wasteland can be re-utilizable for agricultural production, which is categorized as cultivable Wasteland [158]. Nevertheless, the extent of potentially reusable culturable Wasteland depends on the regional policy and economic affluence within a region.

- b)

- Uncultivable Wasteland: Due to meteorological and geographical factors, a few categories of lands that are not fit for use are known as uncultivable Wasteland. Among this group of Wasteland, barren hills, ridges, rock outcrops, and snow-covered areas do not attain any economic uses. Though, we cannot deny their inherent environmental significance, accommodating essential ecological activities on the earth’s surface.

4.3. Management Strategies of Wasteland in India:

- Land revenue system and perception of wasteland during the British raj

- 2.

- Wasteland and its management in the post-independence period

- The first stage (1950-1980):

- The second stage (1980-2000):

- Third stage (2000-present):

4.4. Wasteland Management in India: the Challenges and Recommendation

- a)

- Challenges of wasteland reclamation in India:

- -

- The historical influence of wasteland narrative: The historical notation of wasteland remains the same in present day India’s land-use policy as it did in previous historical periods. Likewise, in the Indian context, the colonial notation of and approach to wasteland is visible, as it is in other parts of the globe. For example, deserts were considered an obstacle for the early European-American settlers in the USA as they were devoid of production and human settlement. From the Native American viewpoint, deserts are not regarded as waste due to their ecological value [194]. The southwestern desert in America is often considered a wasteland which allows the demolition of such lands in a method of nuclear colonialism. As a result, the desert part of America has turned from a wasteland to a literal wasteland [195]. In the context of literal wasteland formation, in India the open natural ecosystem or sometimes the semi-arid ecosystem are tagged as degraded wasteland site in land use classification, without considering its ecosystem valuation. This array of different misclassification carried out through the historical colonial land use policy [196].

- -

- Policy inconsistency: After the commencement of NWDB in 1985, ecological importance of wasteland was prioritized, but before that, wastelands were only judged as valuable from an economic outlook. There was always a clash between ecological restoration and economic enhancement in wasteland reclamation policy. For example, wasteland reclamation through Eucalyptus plantations in the social forestry program can effectively achieve economic security. In most cases, Eucalyptus extracts groundwater from deep inside, and the soil becomes dry with low moisture content.

- -

- Lack of explicit wasteland development policy: Not all land reclamation policies fully consider wasteland development. For example, watershed management only considers wasteland reclamation individually. Rather it is for the overall development of a certain area. On the other hand, social forestry is regarded as one of the prime wasteland reclamation policies. Ideally, it is for protecting natural forests and sustaining local dependency on natural forest resources. Nevertheless, these policies may only be considered an optimum wasteland policy for some regions. For example, social forestry may not be applied in dryland areas due to water scarcity. Even as the Global Energy Network Institute shows, there are only a few specific regions in India (a few states of central and southern India) where the climatic and lithological structure is favorable for the growth of biofuel [197].

- -

- Regional inequalities: Unequal and improper capital investment can be regarded as the organizational cause of land degradation and wasteland formation. In India, less developed regions are experiencing low capital investment due to geographical constraints, climatic variability, and political instability, which results from the concentration of wasteland hotspots being restricted in some specific zones. Low regional affluence also creates the foundation for wasteland conversion.

- -

- Problem to identify wasteland: Different academic centers, research institutes, and government organizations identify it in multiple ways with their different methodologies. This sets out multiple notations of wasteland (ranging from degraded land to fallow), and based on that, the areal extension of wasteland varies in different registered documents.

- -

- Struggle between local farmers and state policies: The struggle between environment versus economic development often drives the land reclamation policy to the extent of disputes between the state government and the local community. Moreover, in a few parts of India, the wasteland reclamation policy has become land-grab-related disputes between local farmers and the state government [198]. This indicates how land-related policies are sometimes less comprehensive, making a particular community vulnerable.

- -

- Lack of comprehensive database: Multiple laws administrated by different government organizations at the central, state, and district levels; these include the ministries of Law and Justice, Rural Development, Mining, Industries, Infrastructure, Urban Development, Tribal Affairs, Home Affairs, and Defense. As which result, there is no comprehensive record available as it will become difficult to manage over a thousand original and active central and state land laws [199].and mismanagement is a predominant example in India that combines with different associated factors [200]. Sometimes the formation of wasteland is driven by socio-political factors rather than physical inputs [30]. Nevertheless, whether the wasteland is good or bad must not be ignored by us, as it is a product of nature, and if it is worse, it would still be preoccupied with the long-run environment and human relations [46].

- b)

- Necessity and recommendation to retrieve wasteland:

- Identifying wastelands per their characteristics is the primary task for effective land-use planning. Which leads to the separate identification of cultivable and uncultivable wastelands. Cultivable wastelands are the potential for plantation, so identifying the culturable wasteland and integrating it with the population cluster, regional climate, soil characteristics, and geology is the best way to analyze crop suitability.

- Apart from the culturable wasteland, the unculturable wastelands can be utilized for other economic activities, excluding agriculture. Sometimes scenic beauty can be useful to convert a landscape into a tourist destination. For example, Kimberly’s “Big Hole,” which results from diamond mining (Mining Wasteland), has been developed into a famous tourist destination. Whereas Chornobyl (Ukraine) and Fukushima (Japan), both sites are experienced nuclear massacres, are now becoming world-class tourist attractions [204].

- The Assessment of current farmland is necessary to understand the degree of degradation so that current farmland may protect from the degradation process.

- Wasteland identification needs to have certain criteria to have a clear separation of wasteland and cropland. Incorporating geospatial techniques, a field-based study by soil scientists, an agro-economic survey by planners, and opinions from local commons directly linked up with lands are mandatory for long-term effective land utilization.

- A participatory approach is the key for wasteland reclamation and long-term SLU in any region of India. The main reason participatory approaches are recognized as an integral part of resource management is the reliability of local commons on resources and their decision-making ability to conserve the localized resources.

- Circular land utilization is another innovative way to reuse sustainable utilization of vacant and underutilized sites through infill measures. Circular land use aims to reuse derelict sites by prioritizing inner development over outer development. In parts of Western Europe, the circular utilization of wasteland through the stages of recycling-production-reuse is significant where the contaminated topsoil is distant, and subsoil reutilizes for economic activity [162]. However, the circular land utilization through wasteland reclamation is much more abundant in the global North than the global South because wastelands in the global South are significantly abundant in rural sets up, which are not the product of contamination.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Decades | Definitions | Perspectives | References (India) |

References(Global) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 to 1969 | Left out without being cultivated for some reasons | Agro-economic | [207] | - |

| 1970 to 1979 | Not available | Not available | Not available | - |

|

1980 to 1989 |

Underutilized degraded land due to soil and water management | Bio-Physical | [11] | - |

| Ecologically unstable with lack of tree and crop | Bio-physical | [208] |

- |

|

| Degraded land with inherent or imposed disabilities | Bio-Physical | [209] | - | |

| Degraded lands that are currently underutilized | Bio-Physical | [52] | [66] | |

|

1990 to 1999 |

Common property lands used by the rural poor for fuelwood and fodder gathering | Property Rights | [115] | - |

| Underutilized degraded land that can be reclaimed through reasonable effort | Bio-Physical | [210] | [64] | |

| “Bad” and needed to be eliminated | Political | [87] | ||

| 2000 to 2009 | Miscellaneous land types that are presently not suitable for production | Agro-economic | [9] | [80] |

| Common property lands | property rights | [113,114] | - | |

|

2010 to present |

Politically malleable term applied from fallow to agroforestry lands | Political | [45] | 57 |

| Degraded lands that are currently underutilized | Bio-Physical | [117] | [67,68] | |

| Wastelands are political constructions | Political | [56,57] | [56] | |

| Production of biomass is less than its optimum productivity | Ecological and economic | [211] | [81,89] | |

| Any lands which are not privately owned | Property rights | [86] | - | |

| Empty, unproductive spaces can be improved for economic and environmental aspects | Agro-economic | [10] | [164] |

Appendix B

| Types of wastelands | Subtypes | Percentage (%) of area covered by each category |

|---|---|---|

| Gullied/Ravinous land | Medium Ravine | 0.20 |

| Deep/Very deep Ravine | 0.09 | |

| Scrubland (land with or without scrub) | Land with dense scrub | 2.25 |

| Land with open scrub | 3.03 | |

| Waterlogged and marshy land | Permanent | 0.05 |

| Seasonal | 0.16 | |

| Land affected by salinity/alkalinity | Moderate | 0.14 |

| Strong | 0.05 | |

| Shifting Cultivation | Current Jhum | 0.12 |

| Abandoned Jhum | 0.14 | |

| Scrub Forest (underutilized notified forest land) | Scrub dominated | 2.63 |

| Agricultural land inside notified forest land | 0.66 | |

| Degraded Pastures/grazing land | - | 0.20 |

| Degraded land under plantation crops | - | 0.01 |

| Sands (Coastal/desert/riverine) | Sands- coastal sand | 0.02 |

| Sands- desert sands | 0.25 | |

| Semi-stabilized to stabilized (> 40m) dune | 0.28 | |

| Semi-stabilized to stabilized moderately high (15- 40m) dune | 0.36 | |

| Sands – Riverine | 0.09 | |

| Mining /Industrial Wasteland | Mining Wasteland | 0.07 |

| Industrial Wasteland | 0.01 | |

| Barren rocky area | - | 2.87 |

| Snow cover and/or glacial area | - | 3.28 |

| Total | - | 16.96 |

Appendix C

| Basis of wasteland category | Main types of wastelands | Subtypes of wasteland | Nature and prospect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Based on causative agents | Natural wasteland | rocky out crop, |

Natural wastelands are appeared physically where mostcases were water and wind erosion are the leading cause |

| gullied/ravinous land, | |||

| glaciated areas | |||

| sandy areas | |||

|

Anthropogenic wasteland |

Political wasteland | Kind of disputed land where most of the cases there is a struggle between state policy and local community | |

| Socio-cultural wasteland | Another category of disputed wasteland where struggle is made between families or within a family | ||

| Wasteland due to economic activity (Industry, mining and Jhum cultivation) | Occurs due to unsustainable man-environment relations which are potential for reuse. | ||

| Based on potential uses | Culturable wasteland | salt-affected land, | Caused by naturally and Human induced factors still they can reuse through proper management |

| gullied /ravenous land, | |||

| water-logged or marshy land, | |||

| upland with or without scrub, | |||

| Jhum or forest blank and | |||

| sandy areas | |||

| Unculturable wasteland | Barren hill, ridge, or rock outcrop | Naturally produced which are not possible to use for production or economic activities. | |

|

snow covered areas |

Appendix D

| Country | Site | Approach | Reclamation Process | Organization | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | Indus basin | Reclamation of salt affected Wasteland | Land and water conservation through ground water treatment | Provincial Irrigation Departments (PIDs) and Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) | [212] |

| Quetta, Zhob, Killa part of Baluchistan | Prevent watershed degradation | Delay Action Dams (DAD) to recharge the ground water for maintaining ecological balance | IUCN, 2008 | [213] | |

| Egypt | Nile delta region |

IWRM approach |

Strengthening surface and ground water management with capacity building approach | The World Bank Global Environmental Facility(GEF) Trust Fund initiated the project in 2011. |

[51] |

| Jordon | Zarqa river basin | Range land restoration through ‘Al-Hima’ approach(traditional land management system in the Arab region) | sustainable, collective use of land resources amongst relevant communities by protecting natural resources, rangelands, and forests | With the assistance of IUCN and the Jordanian Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) since 2010 | [214] |

| Ethiopia | Gunung district (Areka) | Maintaining soil fertility and prevent erosion | African Highland Initiative (AHI) has developed methodologies and processes that could be useful for soil fertility management | Awassa Research center, the Awassa College of Agriculture, CIAT and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), 1997 | [215] |

| Brazil | Paraná III watershed (Itaipu dam) | Rain fed intensification for the development of family farming | Preventing top soil erosion through Contour bunds, with terraces in between, constructed across the slope | From 2008 it was based on civil society’s participation in the farming settlements Onwards 2015 it received the partial assistance from the United Nations Water for Life program |

[216] |

| Indonesia | Buru district, Maluku province and Malang in east Java in Indonesia |

Indigenous approach to modify the fallow vegetations | Producing fallow or secondary vegetation during the inter-cropping phase | This intensive shifting cultivation system primarily carried out through the local aboriginal farmers Onwards 2011, The International Development Research Center (IDRC-Canada) provide their support to intact this traditional approach |

[217] |

| Philippines, | Tinoc and I fugao in Philippines; | The traditional “Banaue Rice Terrace” agro forestry system | In such method rice is planted in terraces, whereas tree planted above the terraces which acts as a natural water supplier for the crop | This is one of the oldest traditional farming strategy by I fugao farmers which exists for more than 2000 years | [218] |

| Tanzania |

Shinyanga and Arusha region | Silvi-pastoral system | Ngitiri: a successful traditional method of land rehabilitation in Shinyanga, the extensive ground cover of shrubs, grasses, herbs, and forbs also help prevent soil erosion | With the collaboration of Tanzania Forest Services (TFS Agency) and Sukuma agropastoral community from 2000 onwards |

[219] |

| Burkina Faso | Yatenga province | Agro forestry | Complex cropping system concentrating runoff water and manure in micro± watersheds | Institut de Recherche pour le deâveloppement (IRD) | [220] |

| Uganda | Upper Nile, Victoria | Watershed management | Gully reclamation for productive purposes | USCAPP (Uganda Soil Conservation and Agroforestry Pilot Project) in 1992 | [221] |

| China |

Shanxi Province | Ecological restoration | Vegetation establishment and ecosystem creation to optimize land productivity and soil fertility | The Municipal Land Bureau, the Mining Group, and the Department of Land Expropriation from 1991–1995 | [222] |

| Germany | demolition sites in Berlin | Industrial wasteland restoration | Introduction of native grassland species(Steppe and Prairies) which has low maintenance cost | This innovation was carried out with the effort by German Research Foundation | [223] |

| England | Industrial Contaminated sites in London and other cities | Gentle Remediation Options (GRO) through Managing contaminated site restoration with ecological enhancement | Removes the surface soils, store them carefully, and then replace them in their original sequence and then vegetation cover. | Implemented by the Department of Environment, food and Rural Affairs in 2009 onwards | [35,161] |

Appendix E

| Stages | Sub-stages | Main programme and policies | Specific features | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colonial wasteland policies | First half of 19th century (till 1920) | Land revenue system Land was regarded as an economic entity only |

Forest, pastures, and grazing ground was regarded as waste | [165] |

| Second half of 19thcentury (from 1920-1950) | Deforestation to expand agricultural land | Forest was no longer regarded as waste due to ship building industry in England | 168] | |

| Post-colonial wasteland policy | First stage (From 1950-1980) |

Redistribution of land and tenancy reform | Unproductive lands(wastelands) were mainly distributed among the poor | [169] |

| Conservation of dry regions | Improvement in dry and drought prone area through dry farming | [199] | ||

| Formation of National Commission on Agriculture (NCA) | Estimated total area of wasteland and initiate a centralized wasteland development programme | [170] | ||

| Integrated watershed development programme in the catchment of flood | Enhance productivity and tackle menace of floods | [188] | ||

| First stage of social forestry | Concept of productive forest where the main aim was to achieve ecology and economic sustenance | [178] | ||

| Second stage (1980-2000) |

Formation of National wasteland development board | Wasteland utilization through forestation and tree plantations to tackle the demand of fuel wood and fodder | [172] | |

| National Land Use and Conservation Board | Introduction of desert and drought area development programme | [95] | ||

| Integrated wasteland development programme | Wasteland development mainly in non-forest areas | [95] | ||

|

National watershed development projects |

For a comprehensive development with the integration of land and water | [173] | ||

| Third stage (From 2000 onwards) |

Second stage of social forestry |

Oilseed production to produce renewable energy and employment generation in wasteland dominated areas | [176] | |

| Formation of national rain fed area authority |

Holistic development in rain fed area | [199] | ||

| Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) and water security | Rainwater harvesting, development of ground water and comprehensive land, water development. | [224] |

Appendix F

| State and region | Approach | Reclamation Process | Organization | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madhya Pradesh (Chambal Valley) | Ravine Reclamation | To restrict the progressive growth of ravines and utilize lands for productive purposes | Central Ravine Reclamation Board in 1967 | [225] |

| Andhra Pradesh |

Watershed Approach | Microsite improvement is done by digging pits at spacing and of a size appropriate to the tree species | International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in 2007 | [54] |

| Andhra Pradesh |

Bio-Diesel plantation | Rehabilitate Common Property Resources (CPRs) with Biodiesel Plantations (Jatrohpacurcas and Pongamiapinnata) Which is a Participatory Approach through the formation of Self-Help Group(SHG) |

International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in 2007 | [54] |

| Rajasthan | Fodder Grasses Plantations | semi-arid systems, livestock is the mainstay of livelihoods for the survival, were common grazing lands are used to support fodder requirements of the livestock population |

ICRISAT and BAIF Institute of Rural Development | [42] |

| Dehradun-Mussoorie (Limestone Mined Areas in Shahastrdhara belt in the Himalayan region), Uttarakhand |

Vegetation in Rehabilitation | Sustain esthetic attractiveness and visual impact on ecology through the plantation. (Eulaliopsisbinata). | Forest Research Institute and CSWCRTI, Dehradun and Eco task Force in 2001 | [226] |

| Neyveliin,Tamilnadu | Afforestation | Ecological stability and aesthetic enhancement through the plantation | Neyveli Lignite Corporation (Tamil Nadu), India from 1970 to 1986 | [227] |

| Gujarat (wastelands in Mahi River stretch) | Agroforestry System | An indigenous Bamboo and Anjan grass (Cenchrusciliaris)-based silvo-pastoral system for enhancing the productivity of ravines | Anand-based Foundation for Ecological Security (FES), Gujarat State Watershed Management Agency (GSWMA), Gujarat State Land Development Corporation (GSLDC), Forest, and Agricultural departments | [228] |

| Kota, Rajasthan | Fruit-Based Agroforestry | Productive Utilization of Ravines Through Fruit-Based Agroforestry |

CSWCRTI, Research Centre, Kota (2006 to 2011) | [229] |

| Sukhomajri in Panchkula district, Haryana | Watershed Development Programmers | agricultural development and equitable distribution of irrigation water | CSWCRTI, Research Centre Chandigarh & Hill Resource Management Society (HRMS) in 1980s | [230] |

| lower and middle Himalayas in Tehri & Garhwal districts, Uttarakhand | Watershed Management | integrated watershed management project (IWMP) for soil and water conservation for Horticulture development and crop production | Central Soil and Water Conservation Research and Training Institute, Dehradun during 1975–86 | [231] |

| Andhra Pradesh | Afforestation | Carbon sequestration and wasteland treatment through Jatropha curcas | International Crop Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) from 2004 was to 2006 | [232] |

| Satpura region, Madhya Pradesh | Afforestation | Reclamation of degraded wasteland through the plantation of medicinal plant | Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (CIMAP), Lucknow and National Botanical Research Institute (NBRI) Lucknow in 1982 and 1989 | [233] |

| Sodic lands of Sultanpur district, Uttar Pradesh | Afforestation | Rehabilitation of Sodic Soil Through Leguminous Trees Plantation | Forest Soil and Land Reclamation Division, Forest Research Institute, Dehra Dun, 2002 | [234] |

| Khurda Bhubaneswar, Odisha | Reclamation of Salt affected Wasteland | Biodrainage plantation of trees (Acacia Mangium, Casuarina Equisetifolia) | ICAR-Indian Institute of Water Management, Bhubaneswar, 2011 | [235] |

| Bundelkhand region (Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh) | Rain fed and supplemental irrigation | Single and double cropping: cereal, beans /mixed for market, complemented with dairy | International Crop Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics | [236] |

References

- Edrisi, S.A.; Abhilash, P.C. Exploring marginal and degraded lands for biomass and bioenergy production: An Indian scenario. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2016, 54, 1537-1551. [CrossRef]

- Wiegmann, K.; Hennenberg, K.J.; Fritsche, U.R. Degraded land, and sustainable bioenergy feedstock production. In Joint international workshop on high nature value criteria and potential for sustainable use of degraded lands.2008.

- Chakraborty, G. Roots and Ramifications of a Colonial construct: The Wastelands in Assam. Institute of Development Studies. 2012.

- Maantay, J. A. The collapse of place: Derelict land, deprivation, and health inequality in Glasgow, Scotland. Cities and the EnvironmentCATE. 2013, 1, 10.

- Dickinson, N. M.; Hartley, W.; Louise A.; Uffindell, A. N.; Rawlinson, P. H.; Putwain, P. Robust biological descriptors of soil health for use in reclamation of brownfield land. Land Contamination & Reclamation. 2005, 4, 317-326.

- Bhattacharyya, R.; Ghosh, B. N.; Mishra, P. K.; Mandal, B.; Rao, C.S.; Sarkar, D.; Das, K.; Anil, K. S.; Lalitha, M.; Hati, K. M.; Franzluebbers, A. J. Soil degradation in India: Challenges and potential solutions. Sustainability. 2015, 4, 3528-3570. [CrossRef]

- Hoover, D. L.; Bestelmeyer, B.; Grimm, N. B.; Huxman, T. E.; Reed, S. C.; Sala, Osvaldo.; T. R. Seastedt.; Wilmer, H.; Ferrenberg, S. Traversing the Wasteland: A Framework for Assessing Ecological Threats to Drylands. BioScience. 2020, 1, 35-47. [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.; Sinha, D.K.; Ahmad, N. Dynamics of land degradation in Uttar Pradesh: Zone-wise analysis. Indian Journal of Economics and Development. 2020, 16(2), 221-228. [CrossRef]

- Deka, S. Evaluation and management of wastelands in Kamrup district of Assam. 2003.

- Baka, J.; Bailis, R. Wasteland energy-scapes: A comparative energy flow analysis of India’s biofuel and biomass economies. Ecological economics. 2014, 108, 8-17. [CrossRef]

- National Wasteland Development Board (NWDB).Description, Classification, Identification, and Mapping of Wastelands. New Delhi: Government of India. 1987.

- Alam, M. A. Regional planning and the waste land development in India: An overview. Asia-Pacific Journal of Social Sciences. 2013, 1, 152.

- Mehmood, M. A.; Ibrahim, M.; Rashid, U.; Nawaz, M.; Ali, S.; Hussain, A.; Gull, M. Biomass production for bioenergy using marginal lands. Sustainable Production and Consumption. 2017, 3-21. [CrossRef]

- Mathey, J.; Rößler, S.; Banse, J.; Lehmann, I.; Bräuer, A. Brownfields as an element of green infrastructure for implementing ecosystem services into urban areas. Journal of Urban Planning and Development. 2015, 3. [CrossRef]

- Kuzman, B.; Prodanović, R. Land Management in Modern Farm Production.2017.

- Boamah, E.F.; Walker, M. Legal pluralism, land tenure and the production of “nomotropic urban spaces” in post-colonial Accra, Ghana. Geography Research Forum. 2016, 36, 86-109.

- Alary, V.; Aboul-Naga, A.; Osman, M.A.; Daoud, I.; Abdelraheem, S.; Salah, E.; Juanes, X.; Bonnet, P. Desert land reclamation programs and family land dynamics in the Western Desert of the Nile Delta (Egypt), 1960–2010. World Development, 2018, 104,140-153. [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.A.; Al-Shankiti, A. Sustainable food production in marginal lands—Case of GDLA member countries. International soil and water conservation research. 2013, 1(1), 24-38. [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, G.S.; Shit, P.K.; Pal, D.K.; Guinea, P.N. Coastal Wasteland Identification and Mapping Using Satellite Data. Melanesian Journal of Geomatics and Property Studies. 2017, 3, 11-21.

- Venkanna, R.; Appalanaidu, K.; Tatababu, C.; Murty, M. Geospatial Analysis for Identification and Mapping of Wasteland Change In Sri PottiSriramulu Nellore District, Andhra Pradesh. Journal of Global Ecology and Environment. 2021, 12(3), 53-62.

- Narayan, L. R.A.; Rao, D.P.; Gautam, N.C. Wasteland identification in India using satellite remote sensing. Remote Sensing,1989, 10(1), 93-106. [CrossRef]

- Wankhade, S.G.; Nandanwar, S.B.; Sarode, R.B.; Shendre, N.M.; Autkar, A.V. Evaluation of Suitability of Medicinal Trees for Wasteland Management. Evaluation of different grain sorghum genotypes for stability and genotypes x environment. 2012, 36(2), 61.

- Balasubramani, K. Physical resources assessment in a semi-arid watershed: An integrated methodology for sustainable land use planning. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. 2018, 142, 358-379. [CrossRef]

- Warwade, P.; Hardaha, M.K.; Kumar, D.; Chandniha, S.K. Estimation of soil erosion and crop suitability for a watershed through remote sensing and GIS approach. Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences.2014, 84(1), 18-23. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P.; Biradar, C.; Louhaichi, M.; Ghosh, S.; Hassan, S.; Moyo, H.; Sarker, A. Finding a Suitable Niche for Cultivating Cactus Pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) as an Integrated Crop in Resilient Dryland Agroecosystems of India. Sustainability, 2019, 11(21). [CrossRef]

- Baka, J. The political construction of wasteland: Governmentality, land acquisition and social inequality in South India. Development and Change. 2013, 2, 409-428. [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I.; Hall, R.; Borras, Jr, S.M.; White, B.; Wolford, W.; The politics of evidence: Methodologies for understanding the global land rush. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Wondimu T, Gebresenbet F. Resourcing land, dynamics of exclusion and conflict in the Maji area, Ethiopia. Conflict, Security & Development. 2018, 6, 547-570. [CrossRef]

- Mahato, N.K. Deforestation, ecological deterioration and scientific forestry in Purulia, 1890s–1960s. History of Science, Technology, Environment, and Medicine in India. Routledge. 2021, 214-232.

- Menon, A. Colonial constructions ofagrarian fields and forests in the Kolli Hills. The Indian Economic & Social History Review.2004, 3, 315-337.

- Whitehead, J. Development and dispossession in the Narmada Valley. Pearson Education India. 2010.

- Hall, C.M. The ecological and environmental significance of urban wastelands and dross capes. Organising. Waste in the city. 2013, 21-40.

- Gill, V. Waste land or brownfield sites are vital for wildlife, BBC Nature. 2012. www.bbc.co.uk/nature/18513022 (accessed on 13 January 17, 2022).

- Muratet, A.; Machon, N.; Jiguet, F.; Moret, J.; Porcher, E. The role of urban structures in the distribution of wasteland flora in the greater Paris area, France. Ecosystems. 2007, 4, 661-671. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, A. D. Wasteland management and restoration in Western Europe. Journal of Applied Ecology. 1989 775-786. [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.; Patel, A.; Syed, B.A.; Gami, B.; Patel, P. Assessing economic feasibility of bio-energy feedstock cultivation on marginal lands. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2021, 154. [CrossRef]

- Prasath, C. H.; Balasubramanian, A.; Prasanthrajan, M.; Radhakrishnan, S. Performance evaluation of different tree species for carbon sequestration under wasteland condition. International Journal of Forestry and Crop Improvement. 2016, 1, 7-13. [CrossRef]

- Laprise, M.; Lufkin, S.; Rey, E. An indicator system for the assessment of sustainability integrated into the project dynamics of regeneration of disused urban areas. Building and Environment. 2015, 29-38. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D. K.; Singh, A. Salinity research in India-achievements, challenges and future prospects. 2015.

- Francis, G.; Raphael, E.; Becker, K. A concept for simultaneous wasteland reclamation, fuel production, and socio-economic development in degraded areas in India: Need, potential and perspectives of Jatropha plantations. Natural resources forum. 2005, 29, 12-24. [CrossRef]

- Ravindranath, N. H.; Lakshmi, C. S.; Manuvie, R.; Balachandra, P. Biofuel production and implications for land use, food production and environment in India. Energy Policy. 2011, 39,737-5745. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.K.; Singh, M.K.; Reddy, B.S.; Manohar, N.S. Potential of wastelands for mixed farming system in India. Range Management and Agroforestry. 2012, 2, 118-122.

- Nalepa, R.A. Land for Agricultural Development in the era of Land Grabbing: A Spatial Exploration of the Marginal Lands Narrative in Contemporary Ethiopia. 2013.

- Di Palma, V. Wasteland: A history. Yale University Press, 2014.

- Ariza-Montobbio, P.; Lele, S. Jatropha plantations for biodiesel in Tamil Nadu, India: Viability, livelihood trade-offs, and latent conflict. Ecological Economics. 2010, 2, 189-195. [CrossRef]

- Farley, P.; Roberts, M.S. Edgelands: Journeys into England’s true wilderness. Random House. 2012.

- Kang, S.; Post, W.M.; Nichols, J.A.; Wang, D.; West, T.O.; Bandaru, V.; Izaurralde, R.C. Marginal lands: Concept, assessment and management. Journal of Agricultural Science. 2013, 5, 129. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Tian, D.L.; Xie, R. X. Soil physical and chemical properties of the wasteland in Xiangtan manganese mine. Acta EcologicaSinica. 2006, 5, 1494-1501.

- Lal, R. Soil erosion by wind and water: Problems and prospects. Soil erosion research methods, Routledge. 2017, 1-10.

- Walsh, D.; Bendel, N.; Jones, R.; Hanlon, P. It’s not ‘just deprivation’: Why do equally deprived UK cities experience different health outcomes? Public health. 2010, 9, 487-95. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M. L. HIMA Mesopotamia: Community Generated Conservation in the Tigris Euphrates Watershed. International Workshop: Towards an Implementation Strategy for the Human Integrated Management Approach Governance System. 2013, 220.

- NRSC. Wastelands Atlas of India. National Remote Sensing Centre, Hyderabad. 2010, 140.

- Li, M.S., 2006. Ecological restoration of mine land with particular reference to the metalliferous mine wasteland in China: A review of research and practice. Science of the total environment, 357(1-3), pp.38-53. [CrossRef]

- Sreedevi, T.K.; Wani, S.P.; Osman, M.; Tiwari, S. Rehabilitation of degraded lands in watersheds. 2009, 205-220.

- Gaur, M.K.; Goyal, R.K.; Kalappurakkal, S.; Pandey, C.B. Common property resources in drylands of India. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 2018, 25(6), 491-499. [CrossRef]

- Borras, Jr. S. M.; Hall, R, Scoones, I.; White, B.; Wolford, W. Towards a better understanding of global land grabbing: An editorial introduction. The Journal of Peasant Studies. 2011, 2, 209-216. [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.; Levidow, L.; Fig, D.; Goldfarb, L.; Hoenicke, M.; Luisa, M. M. Assumptions in the European Union biofuels policy: Frictions with experiences in Germany, Brazil and Mozambique. The Journal of Peasant Studies. 2010, 37, 661-698. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P. Unravelling Foucault’s different spaces. History of the human sciences. 2006, 4, 75-90. [CrossRef]

- Doron, G. M. The dead zone and the architecture of transgression. City. 2000, 2, 247-263. [CrossRef]

- Hough, M. Principles for regional design. The urban design reader. Routledge. 2013, 545-553. [CrossRef]

- Haid, C. Landscapes of wilderness – Heterotopias of the post-industrial city, paper presented at Framing the City, Royal Northern College of Music. 2011.

- Ramson, W. Wasteland to wilderness: Changing perceptions of the environment. The humanities and the Australian environment. 1991, 5-20.

- Hall, C. M. The worthless lands hypothesis and Australia’s national parks and reserves. Australia’s ever-changing forests. Australian Defense Force Academy, Canberra, Australia. 1988, 441-459.

- Hall, C. M. Wasteland to World Heritage. Melbourne University Press, 1992.

- Haase, D. Urban ecology of shrinking cities: An unrecognized opportunity? Nature and Culture. 2008, 1, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Nabarro, R. The General Problem of Urban Wasteland. Built Environment. 1980, 3, 159.

- Fairburn, J.; Walker, G.; Smith, G. Investigating environmental justice in Scotland: Links between measures of environmental quality and social deprivation. 2005.

- Pagano, M.A.; Bowman, A. O. Vacant land in cities: An urban resource. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy. 2000, 1-9.

- Furlan, C. Unfolding Wasteland. Mapping Landscapes in Transformation: Multidisciplinary Methods for Historical Analysis. 2019, 131. [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government Vacant and Derelict Land Survey. Statistical Bulletin Planning Series. Edinburgh: A National Statistics Publication for Scotland. 2012.

- Bambra, C.; Robertson, S.; Kasim, A.; Smith, J.; Cairns-Nagi, J.M.; Copeland, A.; Finlay, N.; Johnson, K. Healthy land? An examination of the area-level association between brownfield land and morbidity and mortality in England. Environment and Planning A. 2014, 2, 433-454. [CrossRef]

- Grimski, D.; Ferber, U. Urban brownfields in Europe. Land Contamination and Reclamation. 2001, 1, 143-148.

- Gray, L. Comparisons of health-related behaviours and health measures in Greater Glasgow with other regional areas in Europe. Glasgow: Glasgow Centre for Population Health. 2008.

- Franz, M.; Pahlen, G.; Nathanail, P.; Okuniek, N.; Koj, A. Sustainable development and brownfield regeneration. What defines the quality of derelict land recycling? Environmental Sciences. 2006, 2, 135-151. [CrossRef]

- Brender, J. D.; Maantay, J. A.; Chakraborty, J. Residential proximity to environmental hazards and adverse health outcomes. American journal of public health. 2011, 37-52. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, C. M.; Forman, D.L.; Rothlein, J. E. Hazard screening of chemical releases and environmental equity analysis of populations proximate to toxic release inventory facilities in Oregon. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1998, 4, 217-226. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.; Lee, C.; Powers, C. Public health and brownfields: Reviving the past to protect the future. American Journal of Public Health. 1998, 12, 1759-1760. [CrossRef]

- Redecker, A. P. Historical aerial photographs and digital photogrammetry for impact analyses on derelict land sites in human settlement areas. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2008, 5-10.

- Ramakrishna, W.; Rathore, P.; Kumari, R.; Yadav, R. Brown gold of marginal soil: Plant growth promoting bacteria to overcome plant abiotic stress for agriculture, biofuels and carbon sequestration. Science of the Total Environment. 2020, 711. [CrossRef]

- Suntana, A.S.; Vogt, K.A.; Turnblom, E.C.; Upadhye, R. Bio-methanol potential in Indonesia: Forest biomass as a source of bioenergy that reduces carbon emissions. Applied energy. 2009, 215-221. [CrossRef]

- Ayambire, R.A.; Amponsah, O.; Peprah, C.; Takyi, S.A. A review of practices for sustaining urban and peri-urban agriculture: Implications for land use planning in rapidly urbanising Ghanaian cities. Land Use Policy. 2019, 84, 260-277. [CrossRef]

- Hought, J.; Birch-Thomsen, T.; Petersen, J.; de, Neergaard.; A, Oelofse, M. Biofuels, land use change and smallholder livelihoods. A case study from Banteay Chhmar, Cambodia. Applied Geography. 2012, 525-532. [CrossRef]

- Portner, B. Frames in the Ethiopian debate on biofuels. Africa Spectrum. 2013, 48(3), 33-53. [CrossRef]

- Skaria, A. Shades of wildness tribe, caste, and gender in western India. Journal of Asian Studies. 1997, 726-745. [CrossRef]

- Bridge, G. Resource triumphalism: Postindustrial narratives of primary commodity production. Environment and Planning A. 2001, 12, 2149-2173. [CrossRef]

- Locke, J. [1680]) Second Treatise of Government. Hollywood: Simon and Brown Mol A P J and Sonnenfeld D A (eds) (2000) Ecological Modernisation Around the World: Perspectives and Critical Debates. New York: Frank Cass. 2011.

- Gidwani, V. K. Wasteland the Permanent Settlement in Bengal. Economic and Political Weekly. 1992, 39-46.

- Lin, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ahmad, N.; Han, Q. A scientometric analysis and visualization of global research on brownfields. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2019, 26(17), 17666-17684. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, M. and Sen, J. A Spatio-temporal Assessment of Brownfield Transformation in a Metropolis: Case of Kolkata India. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bromley, D.W. Formalising property relations in the developing world: The wrong prescription for the wrong malady. Land use policy. 2009, 1, 20-27. [CrossRef]

- Atapattu, S. S.; Kodituwakku, C. D.; Agriculture in South Asia and its implications on downstream health and sustainability: A review. Agricultural Water Management. 2009, 3, 361-373. [CrossRef]

- Gexsi, L.L.P. Global market study on Jatropha. Final Report Prepared for the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF), London, Berlin. 2008.

- Lama, A.D., Klemola, T., Saloniemi, I., Niemelä, P., Vuorisalo, T. Factors affecting genetic and seed yield variability of Jatropha curcas (L.) across the globe: A review. Energy for Sustainable Development. 2018, 42, 170-182. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. A note on rising food prices. World Bank policy research working paper. 2008, 4682.

- Baka, J. Making space for energy: Wasteland development, enclosures, and energy dispossessions. Antipode. 2017, 4, 977-996. [CrossRef]

- Naybor, D. Land as fictitious commodity: The continuing evolution of women’s land rights in Uganda. Gender, Place & Culture. 2015, 6, 884-900. [CrossRef]

- Zerga, B. Land Resource, Uses, and Ownership in Ethiopia: Past, Present and Future. International Journal of Scientific Research Engineering Technology. 2016, 1.

- Wu, J. The Oxford handbook of land economics. Oxford University Press. 2014.

- Cervero, R. Linking urban transport and land use in developing countries. Journal of Transport and Land Use. 2013, 1, 7-24. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, N.; Nkonya, E.; von, B. J. Land degradation, poverty and marginality. Marginality, Springer, Dordrecht. 2014, 181-202.

- Zhu, H. Underlying motivation for land use change: A case study on the variation of agricultural factor productivity in Xinjiang, China. Journal of Geographical Sciences. 2013, 1041-1051. [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, H.K.; Ruesch, A.S.; Achard, F.; Clayton, M.K.; Holmgren, P.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A.; Tropical forests were the primary sources of new agricultural land in the 1980s and 1990s. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010, 38, 16732-16737. [CrossRef]

- Whitt, L. A.; Roberts, M.; Norman, W.; Grieves, V.; Belonging to land: Indigenous knowledge systems and the natural world. Okla. City UL Rev. 2001, 26, 701.

- Kim, J.; Mahoney, J. T. Property rights theory, transaction costs theory, and agency theory: An organizational economics approach to strategic management. Managerial and decision economics. 2005, 4, 223-242. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. From land use right to land development right: Institutional change in China’s urban development. Urban Studies. 2004, 7, 1249-1267. [CrossRef]

- Albertus, M.; Diaz-Cayeros, A; Magaloni, B.; Weingast, B.R. Authoritarian survival and poverty traps: Land reform in Mexico. World Development. 2016, 77, 154-170. [CrossRef]

- Broegaard, R.J. Land tenure insecurity and inequality in Nicaragua. Development and Change. 2005, 5, 845-864. [CrossRef]

- Sklenicka, P. Classification of farmland ownership fragmentation as a cause of land degradation: A review on typology, consequences, and remedies. Land use policy. 2016, 57, 694-701. [CrossRef]

- Assefa, E.; Hans-Rudolf, B. Farmers’ perception of land degradation and traditional knowledge in Southern Ethiopia—Resilience and stability. Land Degradation & Development. 2016, 6, 1552-1561. [CrossRef]

- Magnan, A. The financialization of agri-food in Canada and Australia: Corporate farmland and farm ownership in the grains and oilseed sector. Journal of Rural Studies. 2015, 41, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, B.; Swinton, S. M. Investment in soil conservation in northern Ethiopia: The role of land tenure security and public programs. Agricultural economics. 2003, 1, 69-84. [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Bert, F.; Podesta, G.; Krantz, D.H. Ownership effect in the wild: Influence of land ownership on agribusiness goals and decisions in the Argentine Pampas. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics. 2015, 1, 162-170. [CrossRef]

- Kadekodi, G. K. Common property resource management: Reflections on Theory and the Indian Experience. Oxford University Press. 2004.

- Chopra, K. Wastelands and common property land resources.” In seminar-new Delhi-Malyika Singh. 2001, 24-31.

- Ostrom, E. Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge university press, 1990.

- Thomaz, E.L.; Luiz, J.C. Soil loss, soil degradation and rehabilitation in a degraded land area in Guarapuava (Brazil). Land Degradation & Development. 2012, 1, 72-81. [CrossRef]

- Harms, E.; Baird, I.G. Wastelands, degraded lands and forests, and the class (ification) struggle: Three critical perspectives from mainland Southeast Asia. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography. 2014, 35(3), 289-294. [CrossRef]

- Pederson, D.T. Stream piracy revisited: A groundwater-sapping solution. GSA TODAY. 2001, 9, 4-11. [CrossRef]

- Flowers, R.M.; Wernicke, B.P.; Farley, K.A. Unroofing, incision, and uplift history of the southwestern Colorado Plateau from apatite (U-Th)/He thermochronometry. Geological Society of America Bulletin. 2008, 5-6, 571-587. [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, W. J. D.; Sammons, G. Seasonal land degradation risk assessment for Arizona. Proceedings of the 30th international symposium on remote sensing of environment. 2003, 10-14.

- Powell, R. B.; Kellert, S.R.; Ham, S.H. Interactional theory and the sustainable nature-based tourism experience. Society and Natural Resources. 2009, 8, 761-776. [CrossRef]

- Shit, P.K.; Paira, R.; Bhunia, G.; Maiti, R. Modeling of potential gully erosion hazard using geo-spatial technology at Garbheta block, West Bengal in India. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment. 2015, 1-2, 2. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Guchhait, S. K. Geomorphic threshold estimation for gully erosion in the lateritic soil of Birbhum, West Bengal, India. Soil Discussions. 2016, 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Roy, P.B. Identifying tourism potential of Gangani, India; a swot-ahp approach. Asean: The power of one. 2015, 131.

- Manjunatha, A.V.; Anik, A.R.; Speelman, S.; Nuppenau, E.A. Impact of land fragmentation, farm size, land ownership and crop diversity on profit and efficiency of irrigated farms in India. Land use policy. 2013, 31, 397-405. [CrossRef]

- Venkateswarlu A. Pattern of land distribution and tenancy in rural Andhra Pradesh. Centre for Economic and Social Studies; 2003.

- Korovkin, T. Creating a Social Wasteland? Non-traditional Agricultural Exports and Rural Poverty in Ecuador. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies,2005, 79, 47-67. [CrossRef]

- Brockett, C.D. Land, power, and poverty: Agrarian transformation and political conflict in Central America. Routledge.2019.

- Choi, J.J. Political Cleavages in South Korea. In State and society in contemporary Cornell University Press, Korea. 2018, 13-50.

- Sauer, S.; Mészáros, G. The political economy of land struggle in Brazil under Workers’ Party governments. Journal of Agrarian Change. 2017, 2, 397-414. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M. Centering labor in the land grab debate. The Journal of Peasant Studies. 2011, 2, 281-298. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M. What is land? Assembling a resource for global investment. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 2014, 39(4), 589-602. [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Byerlee, D. Rising global interest in farmland: Can it yield sustainable and equitable benefits? The World Bank. 2011.

- Wolford, W.; Borras, Jr. S. M.; Hall, R.; Scoones, I.; White, B. Governing global land deals: The role of the state in the rush for land. Development and change. 2013, 2, 89-210. [CrossRef]

- Baka, J. What wastelands? A critique of biofuel policy discourse in South India. Geoforum. 2014, 315-323. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, S.; See, L.; Van Der Velde, M.; Nalepa, R. A.; Perger, C.; Schill, C.; McCallum, I.; Schepaschenko, D.; Kraxner, F.; Cai, X.; Zhang, X. Downgrading recent estimates of land available for biofuel production. Environmental science & technology. 2013, 3, 1688-1694. [CrossRef]

- Jasani, N.; Sen, A. Asian food and rural income. Credit Suisse. Asia Pacific Equity Research Macro/Multi Industry. 2008.

- Giampietro, M.; Mayumi, K. The biofuel delusion: The fallacy of large scale agro-biofuels production. Routledge. 2009.

- Ganguli, S.; Somani, A.; Motkuri, R.K.; Bloyd, C.N. India alternative fuel infrastructure: The potential for second-generation biofuel technology (No. PNNL-28283). Pacific Northwest National Lab. (PNNL), Richland, WA (United States). 2018.

- Hunsberger, C.; German, L.; Goetz, A. “Unbundling” the biofuel promise: Querying the ability of liquid biofuels to deliver on socio-economic policy expectations. Energy Policy. 2017,108, 791-805. [CrossRef]

- Palanisami, K.; R. Venkatram. Thiruvannamalai – District Agricultural Plan. Centre for Agricultural and Rural Development Studies (CARDS), Tamil Nadu Agricultural University. 2008.

- Mookiah, S.; Kumar, S. Problems and Prospects of Unorganized Workers in Tamilnadu. 2018.

- Grajales, J. State involvement, land grabbing and counterinsurgency in Colombia. Development and Change. 2013, 2, 211-232. [CrossRef]

- Wolford, W. Environmental Justice and the Construction of Scale in Brazilian Agriculture. Society & Natural Resources. 2008,7, 641–55. [CrossRef]

- Makki, F.; Geisler, C. Development by dispossession: Land grabbing as new enclosures in contemporary Ethiopia. International Conference on global land grabbing, Future Agricultures Sussex, UK. 2011.

- Baletti, B. Saving the Amazon? Land Grabs and sustainable soy as the new logic of conservation. International. Conference of Global Land Grabbing. 2011.

- Burnod, P.; Gingembre, M. A. R. Competition over authority and access: International land deals in Madagascar. Development and change. 2013, 2, 357-37. [CrossRef]

- Grajales, J. A land full of opportunities? Agrarian frontiers, policy narratives and the political economy of peace in Colombia. Third World Quarterly. 2020, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R. L. Political ecology: A critical agenda for change. Social nature: Theory, practice and politics. 2001, 151-169.

- National Remote Sensing Agency Department of Space. Mapping of Wastelands in India from Satellite Images. Project report (Hyderabad Government of India). 1985.

- Indian Council of Agriculture Research (ICAR). Technologies for wasteland development, Degraded Soils-Their Mapping through Soil Surveys, New Delhi. 1987, 1-17.

- NRSA. Wastelands Atlas of India. National Remote Sensing Agency, Hyderabad. 2000, 81.

- NRSA. Category wise wasteland classes during 2015-2016. Wasteland Atlas of India. National Remote Sensing Agency, Hyderabad. 2019.

- van Duppen, J.L.C.M. The Cuvrybrache as Free Place-The diverse meanings of a wasteland in Berlin (Master’s thesis). 2010.

- Das, R. The Politics of Land, Consent, and Negotiation: Revisiting the Development-Displacement Narratives from Singur in West Bengal. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal. 2016,13. [CrossRef]

- Pal, M. Organization at the margins: Subaltern resistance of Singur. Human Relations. 2016, 69(2), 419-438. [CrossRef]

- Olaniya, M.; Bora, P.K.; Das, S.; Chanu, P.H. Soil erodibility indices under different land uses in Ri-Bhoi district of Meghalaya (India). Scientific Reports, 2020, 10(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Quli, S.M.S.; Mushtaq, T. Wasteland reclamation strategy for household timber security of tribes in Jharkhand, India. Journal of Applied and Natural Science. 2017, 9(4), 2264-2271. [CrossRef]

- Doust, S.J.; Erskine, P.D.; Lamb, D. Direct seeding to restore rainforest species: Microsite effects on the early establishment and growth of rainforest tree seedlings on degraded land in the wet tropics of Australia. Forest Ecology and Management. 2006, 1-3, 333-343. [CrossRef]

- Chirwa, P.W.; Larwanou, M.; Syampungani, S.; Babalola, F.D. Management and restoration practices in degraded landscapes of Eastern Africa and requirements for up-scaling. International Forestry Review. 2015, 3, 20-30. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S. An Assessment of the Potential for Bio-based Land Uses on Urban Brownfields (Doctoral dissertation, Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology. 2020.

- Pahlen, G.; Glöckner, S. Sustainable regeneration of European brownfield sites. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment. 2004.

- Nathanail, C.P.; Sustainable brownfield regeneration. Dealing with Contaminated Sites. Springer, Dordrecht. 2011, 1079-1104.

- Spadaro, P.; Rosenthal, L. River and harbor remediation: “polluter pays,” alternative finance, and the promise of a “circular economy”. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 2020, 20(12), 4238-4247. [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, V. Peasant pasts: History and memory in western India. University of California Press. 2007.

- Guha, R. The unquiet woods: Ecological change and peasant resistance in the Himalaya. University of California Press; 2000. [CrossRef]

- Tully, J. An approach to political philosophy: Locke in contexts. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Iqbal, I. Governing the Wasteland Ecology and Shifting Political Subjectivities in Colonial Bengal. RCC Perspectives. 2014, 3, 39-44. [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, R.S.; Bhende, M.J. Land Resources and Policy in Karnataka. Institute for Social and Economic Change. 2013,132.

- Hazra, A. Land reforms: Myths and realities. Concept Publishing Company. 2006.

- Besley, T.; Leight, J.; Pande, R.; Rao, V. Long-run impacts of land regulation: Evidence from tenancy reform in India. Journal of Development Economics. 2016,118, 72-87. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B. N.; Suresh, G. Crop diversification with oilseed crops for-maximizing productivity, profitability and resource conservation. Indian Journal of Agronomy. 2009, 2, 206-214. [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, S.; Khola, O.P.; Kannan, K.; Hombegowda, H.C.; Singh, D.V.; Sundarambal, P.; Thilagam, V.K. Comprehensive impact assessment of watershed development projects in lower Bhavani catchments of Tamil Nadu. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 2021, 1, 66-73. [CrossRef]

- Mathur, K.; Jayal, N.G. Drought management in India: The long-term perspective. Disasters. 1992, 16(1), 60-65. [CrossRef]

- Emg, U.N. Global drylands: A UN system-wide response. Environment Management Group of the United Nations Geneva. 2011.

- Qadir, M.; Schubert, S.; Oster, J.D.; Sposito, G.; Minhas, P.S.; Cheraghi, S.A.; Murtaza, G.; Mirzabaev, A, Saqib, M. High-magnesium waters and soils: Emerging environmental and food security constraints. Science of the total environment. 2018, 1108-1117. [CrossRef]

- Ratna Reddy, V.; Gopinath Reddy, M.; Galab, S.; Soussan, J.; Springate-Baginski, O. Participatory watershed development in India: Can it sustain rural livelihoods? Development and change. 2004, 2, 297-326.

- Sengar, R. S.; Chaudhary, R,Kureel, R. S. Jatropha plantation for simultaneous waste land reclamation fuel production and socio-economic development in degraded areas in India. Bulletin of Pure & Applied Sciences-Botany. 2014, 13-36. [CrossRef]

- Chanakya, H.N.; Mahapatra, D.M.; Sarada, R.; Abitha, R. Algal biofuel production and mitigation potential in India. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 2013, 1, 113-136. [CrossRef]

- Van Eijck, J.; Romijn, H.; Smeets, E.; Bailis, R.; Rooijakkers, M.; Hooijkaas, N.; Verweij, P.; Faaij, A. Comparative analysis of key socio-economic and environmental impacts of smallholder and plantation based jatropha biofuel production systems in Tanzania. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2014, 25-45. [CrossRef]

- Osorio, L.R.M.; Salvador, A.F.T.; Jongschaap, R.E.E.; Perez, C.A.A.; Sandoval, J.E.B.; Trindade, L.M.; Visser, R.G.F.; van L.E.N. High level of molecular and phenotypic biodiversity in Jatropha curcas from Central America compared to Africa, Asia and South America. BMC plant biology. 2014, 14(1), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Van Eijck, J.; Smeets, E.; Faaij, A. Jatropha: A Promising Crop for Africa’s Biofuel Production? Bioenergy for sustainable development in Africa, Springer, Dordrecht. 2012, 27-40.

- Sapeta, H.; Costa, J.M.; Lourenco, T.; Maroco, J.; Van der Linde, P.; Oliveira, M.M. Drought stress response in Jatropha curcas: Growth and physiology. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2013, 76-84. [CrossRef]

- Achten, W.M.; Verchot, L.; Franken, Y.J.; Mathijs, E.; Singh, V.P.; Aerts,Muys, B. Jatropha bio-diesel production and use. Biomass and bioenergy. 2008, 12, 1063-1084. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Zaidi, A.Z.; Malik, S. Identification of Suitable Sites for Plantation of Biofuel Source Jatropha C. using Geospatial Techniques. Journal of Space Technology. 2015, 5(1).

- Rathmann, R.; Szklo, A.; Schaeffer, R. Land use competition for production of food and liquid biofuels: An analysis of the arguments in the current debate. Renewable energy. 2010, 1, 14-22. [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.; Vadivelu, G.A. Common property resources in different agro-climatic landscapes in India. Conservation and society. 2006, 132-154.

- Kerr J, Foley C, Chung K, Jindal R. Reconciling environment and development in the clean development mechanism. Journal of Sustainable Forestry. 2006, 1, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.P.; Singh, H.P.; Sreedevi, T.K.; Pathak, P.; Rego, T.J.; Shiferaw, B.; Iyer, S.R. Farmer-participatory integrated watershed management: Adarsha watershed, Kothapally India. 2003.

- Alemu, B.; Kidane, D. The implication of integrated watershed management for rehabilitation of degraded lands: Case study of ethiopian highlands. J Agric Biodivers Res. 2014, 6, 78-90.

- Bhan, S. Land degradation and integrated watershed management in India. International Soil and Water Conservation Research. 2013, 1, 49-57. [CrossRef]

- Moran, E.C.; Woods, D.O. Comprehensive watershed planning in New York State: The Conesus Lake example. Journal of Great Lakes Research. 2009, 35, 10-14. [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, H.M.; Ffolliott, P.F.; Brooks, K.N. Integrated watershed management: Connecting people to their land and water. CABI. 2007.

- Hooks, G.; Smith, C. L. The treadmill of destruction: National sacrifice areas and Native Americans. American Sociological Review. 2004, 4, 558-75. [CrossRef]

- Endres, D. From wasteland to waste site: The role of discourse in nuclear power’s environmental injustices. Local Environment. 2009, 10, 917-37. [CrossRef]

- Madhusudan, M.D. and Vanak, A.T., 2023. Mapping the distribution and extent of India’s semi-arid open natural ecosystems. Journal of Biogeography, 50(8), pp.1377-1387. [CrossRef]

- Snehi, S.K.; Prihar, S.S.; Gupta, G.; Singh, V.; Raj, S.K.; Prasad, V. The current status of new emerging begomoviral diseases on Jatropha species from India. J Plant PatholMicrobiol. 2016, 357. [CrossRef]

- Sigamany, I. Land rights and neoliberalism: An irreconcilable conflict for indigenous peoples in India? International Journal of Law in Context. 2017, 3, 369-387. [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, R.S. Current land policy issues in, India. 2003.

- Zhang, Y. The credibility of slums: Informal housing and urban governance in India. Land use policy. 2018, 876-890. [CrossRef]

- Dolisca, F.; McDaniel, J.M.; Teeter, L.D.; Jolly, C.M. Land tenure, population pressure, and deforestation in Haiti: The case of Forêt des Pins Reserve. Journal of Forest Economics. 2007, 4, 277-289. [CrossRef]

- Ramsundar, B. Population Growth and Sustainable Land Management in India. Population. 2011, 10.

- Saigal, S. Greening the wastelands: Evolving discourse on wastelands and its impact on community rights in India. 13th Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study on Commons. 2011.

- Maboeta, M. Soils: A wasteland of opportunities. 2015.

- Thompson, M. Rubbish theory: The creation and destruction of value. Encounter. 1979, 12-24. [CrossRef]

- Strasser, S. Waste and Want: The Other Side of Consumption.1992, 5.

- Ministry of food and agriculture. Location and utilisation of wastelands in India. Wasteland survey and reclamation committee report. New Delhi government of India. 1961.

- Bhumbla, D. R.; Khare, A. Estimate of Wastelands in India. Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development. 1984, 18.

- CSIR. Plants for Reclamation of Wastelands. Pub. & Inf. Directorate, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi. 1990.

- NRSC. Technical guidelines: Integrated study to Combat Drought for Sustainable Development. Department of Space, Hyderabad. 1991.

- Chakravarty, S.; Dey, A. N.; Shukla, G. Growing TBOS for Wasteland Development. Environment and Ecology. 2010, 3, 1502-1506.

- Qureshi, A.S.; McCornick, P.G.; Sarwar, A.; Sharma, B.R. Challenges and prospects of sustainable groundwater management in the Indus Basin, Pakistan. Water resources management. 2010, 8, 1551-1569. [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M.; Jamil, M.; Anwar, F.; Awan, A.A.; Muhammad, S. Review A Review on Rangeland Management in Pakistan, Bottlenecks and Recommendations. Biological Sciences-PJSIR. 2018, 2, 115-120. [CrossRef]

- Myint, M. M., & Westerberg, V. (2014). An economic valuation of a large-scale rangeland restoration project through the Hima system in Jordan. ELD Initiative. Nairobi: IUCN.

- Amede, T.; Belachew, T.; Geta, E. Reversing the degradation of arable land in the Ethiopian Highlands. Managing Africa’s Soils. 2001, 23.

- Mello, I., Roloff, G., Laurent, F., Gonzalez, E., & Kassam, A. (2023). Sustainable Land Management with Conservation Agriculture for Rainfed Production: The Case of Paraná III Watershed (Itaipu dam) in Brazil. Rainfed systems intensification and scaling of water and soil management: Four case studies of development in family farming, 99-126.

- Imang, N., Inoue, M., & Sardjono, M. A. (2008). Tradition and the influence of monetary economy in swidden agriculture among the Kenyah people of East Kalimantan, Indonesia. International Journal of Social Forestry, 1(1), 61-82.

- Castonguay, A. C., Burkhard, B., Müller, F., Horgan, F. G., & Settele, J. (2016). Resilience and adaptability of rice terrace social-ecological systems: A case study of a local community’s perception in Banaue, Philippines. Ecology and Society, 21(2). [CrossRef]

- Rubanza, C.D.; Shem, M.N.; Ichinohe, T.; Fujihara, T. Biomass production and nutritive potential of conserved forages in silvopastoral traditional fodder banks (Ngitiri) of Meatu District of Tanzania. Asian-Australasian journal of animal sciences. 2006, 7, 978-983. [CrossRef]

- Roose, E.; Kabore, V.; Guenat, C. Zaï, practice: A West African traditional rehabilitation system for semiarid degraded lands, a case study in Burkina Faso. Arid Soil Research and Rehabilitation. 1999, 4, 343-355. [CrossRef]

- Rockstrom, J. Water resources management in smallholder farms in Eastern and Southern Africa: An overview. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Part B: Hydrology, Oceans and Atmosphere. 2000, 3, 275-283. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Marrs, R. Ecological restoration and land reclamation in open-cast mines in Shanxi Province, China. Journal of Environmental Management. 2000, 3, 205-215. [CrossRef]

- Köppler, M. R., Kowarik, I., Kühn, N., & von der Lippe, M. (2014). Enhancing wasteland vegetation by adding ornamentals: Opportunities and constraints for establishing steppe and prairie species on urban demolition sites. Landscape and Urban Planning, 126, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, V.C.; Garg, A.; Patil, J.P.; Thomas, T. Formulation of integrated water resources management (IWRM) plan at district level: A case study from Bundelkhand region of India. Water Policy. 2020, 22(1), 52-69. [CrossRef]

- Pani, P. Controlling gully erosion: An analysis of land reclamation processes in Chambal Valley, India. Development in Practice. 2016, 8, 1047-1059. [CrossRef]

- Juyal, G.P.; Katiyar, V.S.; Dhadwal, K.S.; Joshie, P.; Arya, R.K. Mined area rehabilitation in Himalayas: Sahastradhara experience. Central Soil and water Conservation Research and Training Institute, Dehradun. 2007, 104.

- Narayana, M. P. Neyveli open cast mine. A review of environmental management of mining operation in India. Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi. 1987, 54–62.

- Chaturvedi, O.P.; Kaushal, R.; Tomar, J.M.; Prandiyal, A.K.; Panwar, P. Agroforestry for wasteland rehabilitation: Mined, ravine, and degraded watershed areas. In Agroforestry Systems in India: Livelihood Security & Ecosystem Services. Springer, New Delhi. 2014, 233-271.

- Parandiyal, A.K.; Sethy, B.K.; Somasundaram, J.; Ali, S.; Meena, H.R. Potential of Agroforestry for the Rehabilitation of Degraded Ravine Lands. In Agroforestry for Degraded Landscapes. Springer, Singapore. 2020, 229-251.

- Kerr, J. Sharing the benefits of watershed management in Sukhomajri, India. Selling forest environmental services: Market-based mechanisms for conservation and development. 2002, 327-343.

- Sharda, V.N.; Sikka, A.K.; Juyal, G.P. Participatory integrated watershed management: A field manual. Central Soil & Water Conservation Research & Training Institute; 2006.

- Wani, S.P.; Chander, G.; Sahrawat, K.L.; Rao, C.S.; Raghvendra, G.; Susanna, P.; Pavani, M. Carbon sequestration and land rehabilitation through Jatropha curcas (L.) plantation in degraded lands. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment. 2012, 112-120. [CrossRef]

- Kiran, K.R.; Rani, M.; Pal, A. Reclaiming degraded land in India through the cultivation of medicinal plants. Bot Res Int. 2009, 174-181.

- Mishra, A.; Sharma, S. D. Leguminous trees for the restoration of degraded sodic wasteland in eastern Uttar Pradesh, India. Land Degradation & Development. 2003, 2, 245-261. [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.K.; Sahoo, N.; Roy, Chowdhury, S.; Mohanty, R.K.; Kundu, D.K.; Behera, M.S.; Patil, D.U.; Kumar, A. Reclamation of coastal waterlogged wasteland through bio drainage. J Indian Soc Coastal Agric Res. 2011, 2, 57-62.

- Garg, K.K., Anantha, K.H., Barron, J., Singh, R., Dev, I., Dixit, S. & Whitbread, A.M.. 2020. Scaling-up Agriculture Water Management Interventions for Building System Resilience in Bundelkhand Region of Central India.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).