Submitted:

18 March 2024

Posted:

19 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review on Earthquake Preparedness

1.1.1. Influence of Gender and Age on Preparedness for Earthquakes-Induced Disasters

1.1.2. Influence of Education and Marital Status on Preparedness for Earthquakes-Induced Disasters

1.1.3. Influence of Employment Status and Income Level on Preparedness for Earthquakes-Induced Disasters

1.1.4. Influence of Disability on Preparedness for Earthquakes-Induced Disasters

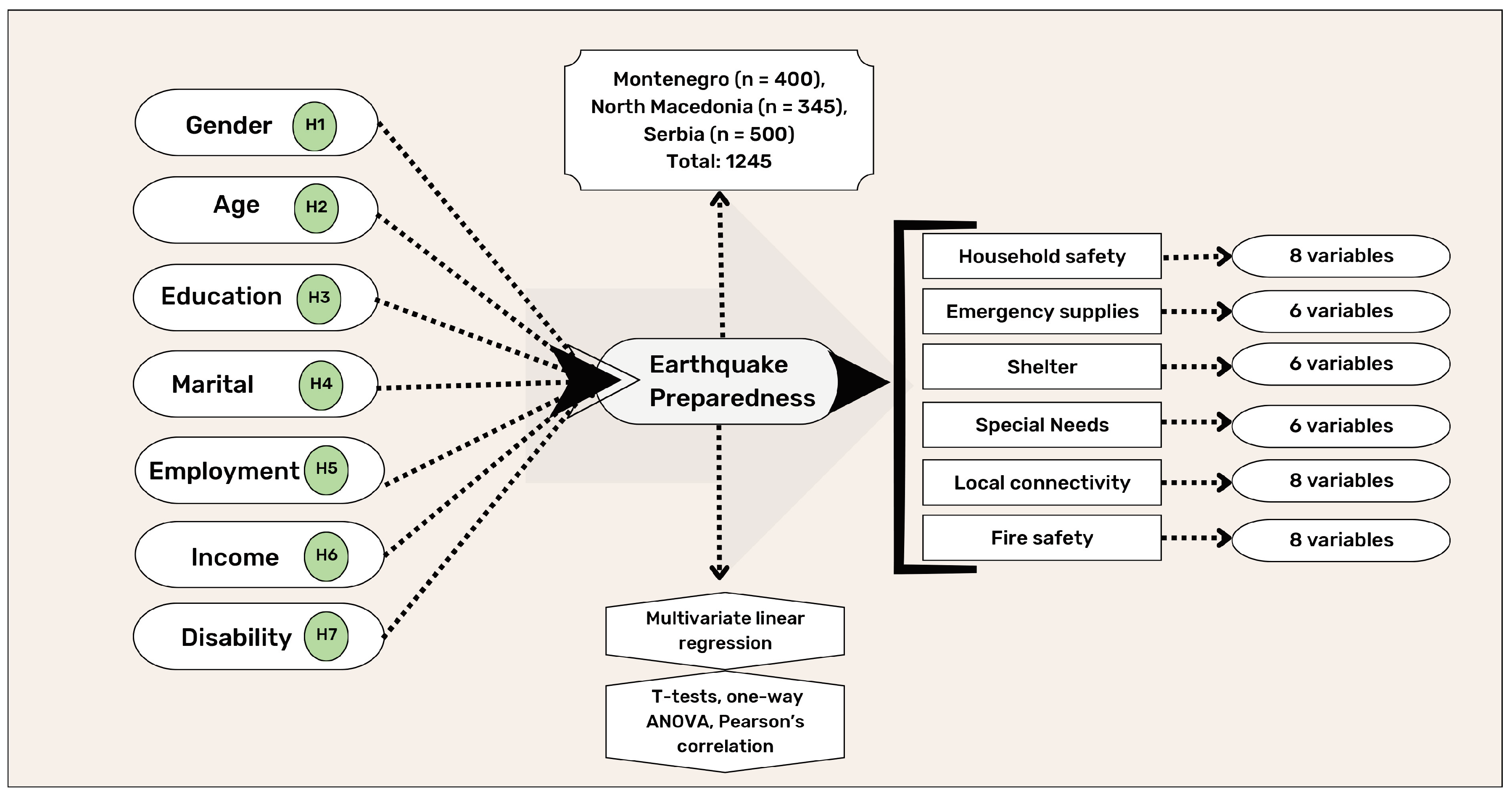

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Socio-Economic and Demographic Characteristics

2.3. Questionnaire Design

2.4. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. The Predictors of Earthquake Preparedness in Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia

| Predictor variable |

Household preparedness | Community preparedness | Disaster preparation | Earthquake risk awareness | Reinforced house | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Gender | −0.028 | 0.105 | −0.011 | 0.253 | 0.110 | 0.102* | −0.142 | 0.132 | −0.049* | 0.153 | 0.124 | 0.055 | 0.326 | 0.112 | 0.130* |

| Age | 0.850 | 0.135 | 0.354** | 0.523 | 0.142 | 0.214** | 0.540 | 0.170 | 0.190 | −0.599 | 0.160 | −0.218** | −0.121 | 0.145 | −0.049 |

| Education | −0.339 | 0.116 | −0.133* | −0.317 | 0.121 | −0.122* | −0.208 | 0.146 | −0.069* | −0.558 | 0.137 | −0.191** | −0.331 | 0.124 | −0.126* |

| Marital status | 0.183 | 0.129 | 0.075 | 0.058 | 0.135 | 0.023 | 0.428 | 0.162 | 0.147 | −0.219 | 0.153 | −0.078 | 0.539 | 0.138 | 0.213 |

| Employment | 0.040 | 0.107 | 0.016 | −0.048 | 0.112 | −0.019 | −0.121 | 0.135 | −0.040* | −0.494 | 0.127 | −0.169 | 0.207 | 0.115 | 0.078* |

| Income | 0.228 | 0.470 | 0.021 | −0.406 | 0.492 | −0.036 | 0.218 | 0.592 | 0.017 | 0.504 | 0.556 | 0.040** | −0.461 | 0.504 | −0.040 |

| Disability | −0.028 | 0.105 | −0.011 | 0.253 | 0.110 | 0.102 | −0.142 | 0.132 | −0.049 | 0.153 | 0.124 | 0.055 | 0.326 | 0.112 | 0.130 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.135 | 0.086 | 0.024 | 0.074 | 0.070 | ||||||||||

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Perceptions and Preparedness Levels for Earthquake Disasters across Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia

| Variables | Countries | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montenegro M(SD) |

North Macedonia M(SD) | Serbia M(SD) |

||

| Household preparedness level | 2.98 (1.12) | 3.52 (0.82) | 3.26 (1.20) | 3.25 (1.05) |

| Community preparedness level | 2.49 (1.02) | 2.74 (1.07) | 2.95 (1.22) | 2.73 (1.10) |

| Damaged house | 2.92 (1.09) | 3.15 (1.10) | 3.13 (1.20) | 3.07 (1.13) |

| Geological knowledge level | 2.35 (1.31) | 2.30 (1.39) | 2.28 (1.43) | 2.31 (1.38) |

| Earthquake house proof | 7.5*−92.5% | 18.6*−81.4% | 13.2*−85.6 | 13.1*−86.9 |

| Reinforced house | 2.97 (1.02) | 3.18 (1.25) | 1.88 (0.32) | 2.67 (0.86) |

| Furnutire secured | 16*−84% | 25.5*−74.5% | 13.2*−85.6 | 18.2*−81,8 |

| Variables | Countries | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montenegro Yes/No (%) |

North Macedonia Yes/No (%) | Serbia Yes/No (%) |

||

| Prepared emergency kit | 40/60 | 64.1/34.8 | 48.8/51.2 | 50.9/49.1 |

| Examined emergency kit contents | 33.5/66.5 | 44.1/55.9 | 62/38 | 46.5/53.5 |

| Easily access emergency kit | 35.3/66.5 | 62.9/30.1 | 64/36 | 54/46 |

| Other emergency supplies | 27.3/72.7 | 54.5/44.3 | 48/52 | 43/57 |

| Emergency supplies rating | 57.3/42.7 | 29.3/70.7 | 51/49 | 45.8/54.2 |

| Community emergency supplies | 10/90 | 8.1/91.9 | 52/48 | 23.3/76.7 |

| Variables | Countries | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montenegro Yes/No (%) |

North Macedonia Yes/No (%) | Serbia Yes/No (%) |

||

| Special care needed | 32.8/67.2 | 62.6/37.4 | 56/44 | 50.46/49.54 |

| Elderly killed injured | 29.7/70.3 | 27/73 | 43.6/56.4 | 33.4/66.6 |

| Family cannot evacuate alone | 24.3/75.7 | 27/73 | 31.2/68.8 | 27.5/72.5 |

| Family difficulties in evacuation | 37.1/62.9 | 38/62 | 57.5/42.5 | 44.2/55.8 |

| Places for vulnerable groups | 2.88*(1.32) | 3.20* (1.36) | 3.18* (1.50) | 3.08 (1.39) |

| Guide for impairments | 2.49* (1.22) | 2.82* (1.25) | 3.28* (1.44) | 3.69 (1.30) |

| Support for vulnerable | 2.89* (1.20) | 3.28* (1.23) | 4.15* (1.08) | 3.44 (1.17) |

| Variables | Countries | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montenegro Yes/No (%) |

North Macedonia Yes/No (%) | Serbia Yes/No (%) |

||

| Participation - disaster preparation | 1.95 (1.19) | 2.08 (1.27) | 2.14 (1.42) | 2.05 (1.29) |

| Earthquake risk awareness | 2.57 (1.23) | 2.85 (1.21) | 2.93 (1.37) | 2.78 (1.27) |

| Neighbours ' rescue ability | 2.95 (1.04) | 3.20 (0.93) | 3.26 (1.22) | 3.13 (1.06) |

| The person for disaster preparedness | 20.3*/79.7% | 15.1*/74.9% | 38.4/61.6% | 24.6/75.4 |

| Communication about disasters | 2.28 (1.16) | 2.31 (1.25) | 2.13 (1.28) | 2.24 (1.23) |

| Disaster preparedness adviser | 36.8*/63.2% | 23.2*/76.8% | 46/54% | 35.3/64.7 |

| Communication with neighbours | 3.31 (1.21) | 3.85 (1.27) | 4.23 (1.04) | 3.79 (1.17) |

| Businesses' helpfulness in disasters | 2.80 (1.09) | 2.86 (1.06) | 3.22 (1.23) | 2.96 (1.12) |

| Variables | Countries | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montenegro M(SD) |

North Macedonia M(SD) | Serbia M(SD) |

||

| Fire extinguisher usage | 41.8*/58.2% | 66.1*/33.9% | 69.6*/30.4% | 59.26/40.74 |

| Home fire extinguisher | 18.5*/81.5% | 30.1*/69.1% | 34.4*/65.6% | 27.66/72.34 |

| Hydrant usage | 2.33 (1.37) | 2.35 (1.46) | 2.14 (1.24) | 3.83 (1.35) |

| Initial fire suppression | 2.29 (1.36) | 2.70 (1.46) | 2.88 (1.65) | 3.38 (1.49) |

| House proximity | 3.06 (1.35) | 2.98 (1.28) | 3.60 (1.33) | 3.21 (1.32) |

| Fire truck access | 69.5*/30.5% | 82.6*/17.4% | 80.4*/19.6% | 77.5/22.5 |

| Improper parking frequency | 4.16 (1.21) | 4.28 (1.14) | 4.16 (1.30) | 4.2 (3.65) |

3.4. Influences of Demographic and Socioeconomic Factors on Perceptions and Preparedness Levels for Earthquake Disasters across Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia

| Variables | Education | Marital status | Employment | Income level | Ownership of property | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Household preparedness level | 12.06 | 0.001* | 16.38 | 0.001** | 14.54 | 0.001** | 3.03 | 0.029* | 0.654 | 0.520 |

| Community preparedness level | 11.45 | 0.001* | 12.47 | 0.001** | 8.43 | 0.004* | 4.03 | 0.007* | 0.042 | 0.959 |

| Damaged house | 4.25 | 0.002* | 13.09 | 0.001** | 53.20 | 0.001** | 2.91 | 0.034* | 1.99 | 0.138 |

| Geological knowledge level | 3.68 | 0.006* | 6.08 | 0.001** | 11.62 | 0.001** | 21.55 | 0.001** | 2.82 | 0.060 |

| Reinforced house | 4.55 | 0.001** | 1.44 | 0.056 | 24.40 | 0.001** | 1.27 | 0.283 | 6.52 | 0.002* |

| Places for vulnerable groups | 2.71 | 0.030* | 1.64 | 0.053 | 4.52 | 0.034* | 0.572 | 0.634 | 3.53 | 0.030* |

| Guide for impairments | 3.85 | 0.004* | 5.71 | 0.001** | 5.19 | 0.023* | 4.75 | 0.003* | 14.13 | 0.001** |

| Support for vulnerable | 8.45 | 0.001* | 8.59 | 0.001** | 0.55 | 0.457 | 15.53 | 0.001** | 4.46 | 0.012* |

| Disaster preparation | 2.51 | 0.001** | 7.78 | 0.001** | 0.33 | 0.565 | 0.438 | 0.726 | 3.31 | 0.037 |

| Earthquake risk awareness | 13.16 | 0.001** | 1.52 | 0.195 | 0.21 | 0.642 | 7.03 | 0.001** | 5.27 | 0.005* |

| Neighbours ' rescue ability | 0.812 | 0.518 | 0.153 | 0.962 | 0.735 | 0.392 | 5.43 | 0.001** | 0.47 | 0.624 |

| Communication about disasters | 5.92 | 0.001 | 8.40 | 0.001** | 4.84 | 0.028* | 0.800 | 0.494 | 0.663 | 0.516 |

| Businesses helpfulness | 2.59 | 0.036* | 2.85 | 0.023 | 7.32 | 0.007* | 8.60 | 0.001** | 1.62 | 0.197 |

| Hydrant usage | 3.43 | 0.009* | 1.23 | 0.057 | 0.135 | 0.713 | 5.78 | 0.001** | 1.58 | 0.206 |

| Improper parking frequency | 15.48 | 0.001** | 12.36 | 0.001** | 14.93 | 0.001** | 6.94 | 0.001** | 1.21 | 0.123 |

| Variables | Age | |

|---|---|---|

| Sig. | r | |

| Household preparedness level | 0.001** | −0.242 |

| Community preparedness level | 0.001** | −0.283 |

| Damaged house | 0.001** | 0.278 |

| Geological knowledge level | 0.324 | 0.028 |

| Reinforced house | 0.001** | 0.126 |

| Places for vulnerable groups | 0.312 | −0.029 |

| Guide for impairments | 0.024 | 0.064 |

| Support for vulnerable | 0.001** | 0.221 |

| Participation - disaster preparation | 0.001** | −0.101 |

| Earthquake risk awareness | 0.054 | 0.055 |

| Neighbours ' rescue ability | 0.066 | 0.052 |

| Communication about disasters | 0.796 | 0.007 |

| Communication with neighbours | 0.164 | 0.039 |

| Businesses' helpfulness in disasters | 0.001** | 0.183 |

| Hydrant usage | 0.253 | 0.032 |

| Initial fire suppression | 0.001** | 0.149 |

| Improper parking frequency | 0.817 | 0.007 |

| Variable | Fear of disasters | Disability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sig.(2-tailed) | X2 | Sig. (2-tailed) | X2 | |

| Household preparedness level | 0.001** | 57.29 | 0.069 | 8.71 |

| Community preparedness level | 0.001** | 28.33 | 0.096 | 7.89 |

| Damaged house | 0.001** | 51.82 | 0.057 | 9.21 |

| Geological knowledge level | 0.001** | 21.79 | 0.284 | 5.03 |

| Earthquake house proof | 0.276 | 1.18 | 0.381 | 0.767 |

| Reinforced house | 0.007* | 14.25 | 0.032* | 4.57 |

| Furnutire secured | 0.943 | 0.45 | 0.340 | 0.046 |

| Prepared emergency kit | 0.132 | 2.27 | 0.950 | 0.003 |

| Examined emergency kit contents | 0.139 | 0.99 | 0.070 | 3.27 |

| Easily access emergency kit | 0.228 | 1.45 | 0.159 | 6.59 |

| Other emergency supplies | 0.002* | 9.21 | 0.491 | 0.31 |

| Emergency supplies rating | 0.001** | 24.10 | 0.241 | 0.43 |

| Community emergency supplies | 0.001** | 22.04 | 0.342 | 0.52 |

| Designated shelter nearby | 0.001** | 21.08 | 0.160 | 1.97 |

| Route to shelter | 0.004* | 8.29 | 0.165 | 0.07 |

| Obstacle on route to shelter | 0.006* | 10.37 | 0.001** | 18.12 |

| Neighbour alert before evacuation | 0.240 | 1.54 | 0.962 | 0.291 |

| Shelter condition | 0.001** | 17.39 | 0.416 | 1.75 |

| Shelter management | 0.065 | 1.44 | 0.858 | 1.31 |

| Special care needed | 0.009* | 9.47 | 0.016* | 8.21 |

| Elderly killed injured | 0.001** | 44.26 | 0.748 | 1.93 |

| Family difficulties in evacuation | 0.264 | 1.24 | 0.705 | 0.78 |

| Places for vulnerable groups | 0.001** | 40.40 | 0.034* | 10.42 |

| Guide for impairments | 0.001** | 45.11 | 0.006* | 14.31 |

| Support for vulnerable | 0.007* | 14.25 | 0.050 | 4.52 |

| Participation - disaster preparation | 0.001** | 23.59 | 0.113 | 7.48 |

| Earthquake risk awareness | 0.001** | 33.27 | 0.018* | 11.85 |

| Neighbours ' rescue ability | 0.001** | 22.29 | 0.153 | 6.70 |

| The person for disaster preparedness | 0.490 | 0.48 | 0.054 | 0.89 |

| Communication about disasters | 0.387 | 4.14 | 0.044* | 9.80 |

| Disaster preparedness adviser | 0.57 | 3.98 | 0.556 | 0.027 |

| Communication with neighbours | 0.64 | 1.23 | 0.510 | 3.29 |

| Businesses' helpfulness in disasters | 0.072 | 2.56 | 0.261 | 5.24 |

| Fire extinguisher usage | 0.004* | 55.12 | 0.104 | 2.64 |

| Home fire extinguisher | 0.001* | 14.87 | 0.246 | 2.80 |

| Hydrant usage | 0.054 | 2.27 | 0.001* | 26.19 |

| Initial fire suppression | 0.123 | 3.43 | 0.010* | 15.01 |

| House proximity | 0.453 | 1.56 | 0.045* | 9.74 |

| Fire truck access | 0.321 | 1.21 | 0.63 | 0.91 |

| Improper parking frequency | 0.057 | 1.19 | 0.001** | 30.72 |

| Variable | F | t | Sig. (2-Tailed) |

Male M (SD) |

Female M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household preparedness level | 1.03 | 1.49 | 0.136 | 3.34 (1.21) | 3.18 (1.18) |

| Community preparedness level | 0.39 | 3.60 | 0.001** | 3.07 (1.22) | 2.67 (1.18) |

| Damaged house | 0.17 | 1.65 | 0.098 | 3.23 (1.16) | 3.05 (1.21) |

| Geological knowledge level | 4.21 | 0.14 | 0.882 | 2.28 (1.33) | 2.26 (1.48) |

| Reinforced house | 2.96 | 2.26 | 0.024* | 3.45 (1.11) | 3.19 (1.31) |

| Places for vulnerable groups | 6.67 | 1.24 | 0.215 | 3.27 (1.40) | 3.10 (1.56) |

| Guide for impairments | 0.360 | 2.61 | 0.059 | 3.08 (1.48) | 3.42 (1.39) |

| Support for vulnerable | 6.42 | 1.94 | 0.057 | 4.04 (1.17) | 4.23 (1.01) |

| Disaster preparation | 0.262 | 0.60 | 0.545 | 2.10 (1.37) | 2.17 (1.46) |

| Earthquake risk awareness | 0.082 | 1.63 | 0.102 | 3.06 (1.40) | 2.85 (1.34) |

| Neighbours ' rescue ability | 4.95 | 0.26 | 0.792 | 3.24 (1.13) | 3.27 (1.29) |

| Communication about disasters | 9.74 | 1.55 | 0.122 | 1.65 (0.47) | 1.58 (0.49) |

| Communication with neighbours | 2.45 | -2.17 | 0.030* | 1.97 (1.16) | 2.22 (1.34) |

| Businesses helpfulness | 48.65 | 1.59 | 0.112 | 4.25 (0.98) | 4.22 (1.09) |

| Hydrant usage | 2.31 | 1.21 | 0.076 | 2.50 (1.47) | 2.28 (1,54) |

| Initial fire suppression | 1.18 | 0.21 | 0.083 | 3.11 (1.01) | 3.29 (1.34) |

| Improper parking frequency | 21.25 | 1.15 | 0.067 | 3.02 (1.31) | 3.12 (1.57) |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Questions |

Responses (circle the answer you believe best corresponds to reality) |

| Safety of the household | How do you assess the readiness of your household to respond to an earthquake on a scale of 1 to 5? (1 - insufficient; 5 - excellent). | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| How do you assess the readiness of your municipality/city to respond to an earthquake on a scale of 1 to 5? (1 - insufficient; 5 - excellent). | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Do you think your house (apartment) will be damaged in the event of an earthquake (intensity 6 on the MCS scale or stronger)? (1 - not at all; 5 - quite likely). | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Do you know the geological layers (soil composition) beneath your house? (1 - don't know at all; 5 - know very well). | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Have you checked the earthquake resistance of your house? | Yes No | |

| Is your house constructed with reinforced concrete? | Yes No | |

| Have you secured your furniture to the wall? | Yes No | |

| Do you think that buildings in your local municipality are constructed with reinforced concrete? (1 - none of them; 5 - all of them are constructed with reinforced concrete). | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Supplies | Do you have a first aid kit in your household? | Yes No |

| Have you checked the contents of the first aid kit, if you have one? | Yes No | |

| Do you keep the first aid kit in an easily accessible place? | Yes No | |

| Do you have any other emergency supplies? | Yes No | |

| Do you think your emergency supplies are sufficient in case of an emergency? (1 - not sufficient; 5 - very sufficient). | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Does your local government have emergency supplies? | Yes No | |

| Shelter | Do you know your designated shelter nearby? | Yes No |

| Do you know the route to the shelter? | Yes No | |

| Are there obstacles on the route to the shelter? | Yes No | |

| Will you call your neighbours when evacuating? | Yes No | |

| Do you know the condition of the designated shelter? | Yes No | |

| Do you know who manages the shelters? | Yes No | |

| Special Needs | Do you know which people require special care in emergencies, specifically in the case of earthquakes? | Yes No |

| Are you aware that the majority of casualties and injuries occur among the older population? (1 - don't know at all; 5 - know very well). | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Is there someone in your family who couldn't evacuate alone in the event of an earthquake? | Yes No | |

| Do you know where elderly, disabled individuals and infants live in your community? (1 - don't know at all; 5 - know very well). | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Do you know how to communicate with deaf or hearing-impaired individuals? (1 - don't know at all; 5 - know very well). | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Do you know what assistance older individuals, people with disabilities, and infants require? (1 - don't know at all; 5 - know very well). | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Local connectivity | Have you participated in any way in preparing the local government for disasters? (1 - not at all; 5 - completely) | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Do you think residents of your municipality/city are aware that an earthquake could occur in your local government? (1 - not aware at all; 5 - fully aware) | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Do you believe your neighbours can independently rescue themselves in the event of an earthquake (and to what extent)? (1 - not at all; 5 - definitely can) | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Does your local government have a reliable person working on disaster preparedness measures? | Yes No | |

| Do you talk to people in your municipality/city about natural disasters? (1 - I don't talk; 5 - I talk daily) | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Do you know someone who can advise you on disaster preparedness? | Yes No | |

| Do you communicate with your neighbours? (1 - I don't communicate with anyone, 5 - I communicate with everyone) | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Do you think businesses in your municipality/city are helpful in emergencies? (1 - not helpful at all; 5 - extremely helpful) | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Fire | Do you know how to use a fire extinguisher? | Yes No |

| Do you have a fire extinguisher for initial fires in your home/apartment? | Yes No | |

| Do you know where fire extinguishers and hydrants are in your neighbourhood? (1 - don't know at all; 5 - know very well) | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Have you used a hydrant or fire hose? | Yes No | |

| Have you heard of the phrase "Initial Fire Suppression"? (1 - never heard; 5 - heard many times) | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Are houses in your neighbourhood close to each other (distance less than 1 meter)? (1 - none are close; 5 - all are very close) | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Can fire trucks access any street in your neighbourhood? | Yes No | |

| Do you often see improperly parked cars? (1 - don't see them at all; 5 - see them every day) | 1 2 3 4 5 |

References

- Pereira, S.M.; Rego, I.E.; Mónico, L.S.M. Earthquake recommendations in Europe: a qualitative coding methodology for the analysis of preparedness and response recommendations from authorities. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2023, 96, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, J.; Tierney, K. Disaster preparedness: Concepts, guidance, and research. Colorado: University of Colorado 2006, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Halkia, G.; Ludwig, L.G. Household earthquake preparedness in Oklahoma: a mixed methods study of selected municipalities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2022, 73, 102872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, U.B.N.; Najam, F.A.; Rana, I.A. The impact of risk perception on earthquake preparedness: An empirical study from Rawalakot, Pakistan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2022, 76, 102989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwazu, G.C.; Chang-Richards, A. A framework of livelihood preparedness for disasters: A study of the Kaikōura earthquake in New Zealand. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2021, 61, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Kevin, R.; Shaw, R.; Filipović, M.; Mano, R.; Gačić, J.; Jakovljević, V. Household earthquake preparedness in Serbia – a study from selected municipalities. Acta Geographica 2019, 59. [Google Scholar]

- National Research, Council, Earth Division on, Studies Life, Sciences Committee on Disaster Research in the Social, Challenges Future, and Opportunities. Facing Hazards and Disasters: Understanding Human Dimensions: National Academies Press, 2006.

- Mileti, Dennis. Disasters by Design:: A Reassessment of Natural Hazards in the United States: Joseph Henry Press, 1999.

- Alexander, D. Confronting Catastrophe, New Perspectives on Natural Disasters. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Lindell, Michael K, Kathleen J Tierney, and Ronald W Perry. Facing the Unexpected:: Disaster Preparedness and Response in the United States: Joseph Henry Press, 2001.

- Edward, Bryant. Natural Hazards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Coppola, Damon P. Introduction to International Disaster Management. New York: Elsevier, 2006.

- Perry, Ronald W. "What Is a Disaster?" In Handbook of Disaster Research, 1-15: Springer, 2007.

- Paul, Bimal Kanti. Environmental Hazards and Disasters: Contexts, Perspectives and Management: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- Tobin, Graham A, and Burrell E Montz. "Natural Hazards and Technology: Vulnerability, Risk, and Community Response in Hazardous Environments." In Geography and Technology, 547-70: Springer, 2004.

- Quarantelli, E.L. Catastrophes are different from disasters: some implications for crisis planning and managing drawn from Katrina. Understanding Katrina: Perspectives from the social sciences 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Quarantelli, E.L.; Perry, R. A social science research agenda for the disasters of the 21st century: Theoretical, methodological and empirical issues and their professional implementation. What is a disaster 2005, 325–396. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, Andreas, Thomas Luckenbach, Thomas Risse, Thomas Kirste, and Holger Kirchner. "Design Challenges for an Integrated Disaster Management Communication and Information System." Paper presented at the The First IEEE Workshop on Disaster Recovery Networks (DIREN 2002) 2002.

- Flint, C.; Brennan, M. Community emergency response teams: From disaster responders to community builders. Rural realities 2006, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Moe, T.L.; Gehbauer, F.; Senitz, S.; Mueller, M. Balanced scorecard for natural disaster management projects. Disaster Prevention and Management 2007, 16, 785–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, D. A framework for integrated emergency management. Public Administration Review 1985, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettieri, E.; Masella, C.; Radaelli, G. Disaster management: findings from a systematic review. Disaster Prevention and Management 2009, 18, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, Marlene, and Robert S Carmichael. Notable Natural Disasters. California: Salem Press, 2007.

- Thouret, J.-C. Urban hazards and risks; consequences of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions: an introduction. GeoJournal 1999, 49, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltman, Joseph P, John Lidstone, and Lisa M Dechano. International Perspectives on Natural Disasters: Occurrence, Mitigation, and Consequences. Vol. 21: Springer Science & Business Media, 2004.

- Cvetković, Vladimir. "Upravljanje Rizicima U Vanrednim Situacijama - Disaster Risk Management." Naučno-stručno društvo za upravljanje rizicima u vanrednim situacijama …, 2020.

- FEMA. Personal Preparedness in America: Findings from the Citizen Corps National Survey; 2009.

- Цветкoвић, В. Спремнoст за реагoвање на прирoдну катастрoфу - преглед литературе. Безбједнoст, пoлиција и грађани 2015, 1-2/15, 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Godschalk, David R. "Disaster Mitigation and Hazard Management." In Emergency Management: Principles and Practice for Local Government, edited by T. And Hoetmer Drabek, G. , 131-60. Washington, DC: International City Management Association, 1991.

- Faupel, C.E.; Kelley, S.P.; Petee, T. The impact of disaster education on household preparedness for Hurricane Hugo. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 1992, 10, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, David F, Richard A Colignon, Mahasweta M Banerjee, Susan A Murty, and Mary Rogge. Partnerships for Community Preparedness: US University of Colorado. Institute of Behavioral Science, 1993.

- Societies, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent. "Introduction to Disaster Preparedness." http://www.ifrc.org/Docs/pubs/disasters/resources/corner/dpmanual/all.pdf (accessed 30.04.).

- Tierney, K.J.; Lindell, M.K.; Perry, R.W. Facing the unexpected: disaster preparedness and response in the United States. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 2002, 11, 222–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Keith, and David N Petley. "Environmental Hazards. Assessing Risk and Reducing Disaster." Londona: Routledge, 2009.

- Said, A.M.; Ahmadun, F.l.-R.; Mahmud, A.R.; Abas, F. Community preparedness for tsunami disaster: a case study. Disaster Prevention and Management 2011, 20, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, S.; Eaton, J.L.; Feroz, S.; Bainbridge, A.A.; Hoolachan, J.; Barnett, D.J. Personal disaster preparedness: an integrative review of the literature. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness 2012, 6, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hémond, Y.; Robert, B. Preparedness: the state of the art and future prospects. Disaster Prevention and Management 2012, 21, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reininger, B.M.; Rahbar, M.H.; Lee, M.; Chen, Z.; Alam, S.R.; Pope, J.; Adams, B. Social capital and disaster preparedness among low income Mexican Americans in a disaster prone area. Social Science & Medicine 2013, 83, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Combs, J.P.; Slate, J.R.; Moore, G.W.; Bustamante, R.M.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Edmonson, S.L. Gender differences in college preparedness: A statewide study. The Urban Review 2010, 42, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabek, T.E. Social processes in disaster: Family evacuation. Social problems 1969, 16, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, K. Gender differences in human loss and vulnerability in natural disasters: a case study from Bangladesh. Indian Journal of Gender Studies 1995, 2, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano-Negrin, R.; Sheaffer, Z. Are women “cooler” than men during crises? Exploring gender differences in perceiving organisational crisis preparedness proneness. Women in Management Review 2004, 19, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M. Gender matters: Lessons for disaster risk reduction in South Asia. 2007.

- Mulilis, J.-P. Gender and Earthquake Preparedness: A Research Study of Gender Issues in Disaster Management: Differences in Earthquake Preparedness Due to Traditional Stereotyping or Cognitive Appraisal of Threat? 1999.

- Myers, M. ‘Women and children first’ Introducing a gender strategy into disaster preparedness. Gender & Development 1994, 2, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, F.H. Epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 1992, 60, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, H.; Kennedy, P.; Quarantelli, E.L.; Ressler, E.; Dynes, R. Handbook of disaster research; Springer Science & Business Media: 2009.

- Rüstemli, A.; Karanci, A.N. Correlates of earthquake cognitions and preparedness behavior in a victimized population. The Journal of Social Psychology 1999, 139, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomio, J.; Sato, H.; Matsuda, Y.; Koga, T.; Mizumura, H. Household and Community Disaster Preparedness in Japanese Provincial City: A Population-Based Household Survey. Advances in Anthropology 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.J.; Freidenburg, W.R. Gender and environmental risk concerns: a review and analysis of available research. Environment and Behavior 1996, 28, 302–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, R. "Communicating to a Diverse Population." Paper presented at the National Science and Technology Conference on Risk Assessment and Decision Making for Natural Hazards, Wash .C. 1995.

- Phillips, B.D. . "Gender as a Variable in Emergency Response." Paper presented at the The Loma Prieta Earthquake: Studies in Short Term Impacts., Boulder CO 1990.

- Noel, G.E. "The Role of Women in Health-Related Aspects of Emergency Management: A Caribbean Perspective." Paper presented at the The Gendered Terrain of Disaster: Through the Eyes of Women., Westport, Conn 1990.

- Able, E. , and M. Nelson. "Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women’s Lives." Albany, NY: SUNY Press 1990.

- Szalay, L.B., A. Inn, S.K. Vilov, and J.B. Strohl. Regional and Demographic Variations in Public Perceptions Related to Emergency Preparedness. . Bethesda. Md.: Institute for Comparative Social and Cultural Studies Inc., 1996.

- Murphy, R. Rationality and Nature: A Sociological Inquiry into a Changing Relationship. New York: Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994.

- Melick, M.E.; Logue, J.N. The effect of disaster on the health and well-being of older women. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 1985, 21, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murrell, S.A.; Norris, F.H. Resources, life events, and changes in positive affect and depression in older adults. American Journal of Community Psychology 1984, 12, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, M.; Aroni, S.; Coulson, A. Injuries in the Coalinga earthquake. The Coalinga earthquake of May 2 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R., M. Johnston, and E. Peters. "At a Competitive Disadvantage? The Fate of the Elderly in Collective Flight." Paper presented at the annual meeting of the North Central Sociological Association, Akron, OH 1989.

- Sattler, D.N.; Kaiser, C.F.; Hittner, J.B. Disaster Preparedness: Relationships Among Prior Experience, Personal Characteristics, and Distress1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2000, 30, 1396–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnis, K.K.; Johnston, D.M.; Ronan, K.R.; White, J.D. Hazard perceptions and preparedness of Taranaki youth. Disaster Prevention and Management 2010, 19, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Suar, D. Do lessons people learn determine disaster cognition and preparedness? Psychology & Developing Societies 2007, 19, 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hurnen, F.; McClure, J. The effect of increased earthquake knowledge on perceived preventability of earthquake damage. Australas. J. Disaster Trauma Stud. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, M. Social location and self-protective behavior: Implications for earthquake preparedness. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 1993, 11, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Becker, J.; Paton, D. Multi-agency community engagement during disaster recovery: Lessons from two New Zealand earthquake events. Disaster Prevention and Management 2012, 21, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, L.A.; Goltz, J.D.; Bourque, L.B. Preparedness and hazard mitigation actions before and after two earthquakes. Environment and behavior 1995, 27, 744–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittal, M.J.; McClure, J.; Siegert, R.J.; Walkey, F.H. Predictors of two types of earthquake preparation: survival activities and mitigation activities. Environment and behavior 2008, 40, 798–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEMA. Personal Preparedness in America: Findings from the Citizen Corps National Survey. 2009.

- Kellenberg, D.K.; Mobarak, A.M. Does rising income increase or decrease damage risk from natural disasters? Journal of urban economics 2008, 63, 788–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, S.; Aharonson-Daniel, L.; Shohet, I.M.; Peek-Asa, C.; Bar-Dayan, Y. Integrating epidemiological and engineering approaches in the assessment of human casualties in earthquakes. Natural Hazards 2015, 78, 1447–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L.; Notaro, S.J. Personal emergency preparedness for people with disabilities from the 2006-2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Disability and health journal 2009, 2, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Wang, H.; Du, Q.; Zeng, Y. Natural hazards preparedness in Taiwan: A comparison between households with and without disabled members. Health security 2017, 15, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrović, M. Advantages and limitations of online research method. Marketing 2014, 45, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, M. Geografsko-istorijski atlas Crne Gore: formiranje crnogorske teritorije: Prevalis-Duklja-Zeta-Crna Gora; Dukljanska akademija nauka i umjetnosti: 2022.

- Radojičić, B. Geografija Crne Gore; Dukljanska akademija nauka i umjetnosti: 2008.

- Ivanović, S. Zemljotresi fenomeni prirode; Crnogorska akademija nauka i umjetnosti: 1991.

- Dumurdzanov, N.; Serafimovski, T.; Burchfiel, B.C. Cenozoic tectonics of Macedonia and its relation to the South Balkan extensional regime. Geosphere 2005, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timiovska, L.S. A note on attenuation of earthquake intensity in Macedonia. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 1992, 11, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černih, D., and V. Čejkovska. "Seismic Monitoring and Data Processing in Seismological Observatory in Skopje—Republic of Macedonia—Basis for a Complex Geophysical Monitoring." 2015.

- Pekevski, Lazo. "Airport Conditions in Macedonia: Seismic Risks." In Geomagnetics for Aeronautical Safety: A Case Study in and around the Balkans, 271-79: Springer, 2006.

- Drogreshka, K.; Najdovska, J.; Chernih-Anastasovska, D. Seismic Zones and Seismicity of the Territory of the Republic of North Macedonia. Knowledge International Journal 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marovic, M.; Djokovic, I.; Pesic, L.; Radovanovic, S.; Toljic, M.; Gerzina, N. Neotectonics and seismicity of the southern margin of the Pannonian basin in Serbia. EGU Stephan Mueller Special Publication Series 2002, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolmasov, B.; Jovanovski, M.; Ferić, P.; Mihalić, M. Losses due to historical earthquakes in the Balkan region: Overview of publicly available data. Geofizika 2011, 28, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Dragicevic, S.; Filipovic, D.; Kostadinov, S.; Zivkovic, N.; Andjelkovic, G.; Abolmasov, B. Natural hazard assessment for land-use planning in Serbia. International Journal of Environmental Research 2011, 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Panić, M.; Kovačević-Majkić, J.; Miljanović, D.; Miletić, R. Importance of natural disaster education-case study of the earthquake near the city of Kraljevo: First results. Journal of the Geographical Institute Jovan Cvijic, SASA 2013, 63, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonijevic, S.K.; Arroucau, P.; Vlahovic, G. Seismotectonic Model of the Kraljevo 3 November 2010 Mw 5.4 Earthquake Sequence. Seismological Research Letters 2013, 84, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Tomer, M.; Lal, S.; Chopra, S.; Singh, S.; Prajapati, S.; Sharma, M.L.; Sandeep. Estimation of the source parameters of the Nepal earthquake from strong motion data. Natural Hazards 2016, 83, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Ronan, K.; Shaw, R.; Filipović, M.; Mano, R.; Gačić, J.; Jakovljević, V. Household earthquake preparedness in Serbia: A study of selected municipalities. Acta Geographica 2019, 59, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Dragašević, A.; Protić, D.; Janković, B.; Nikolić, N.; Predrag, M. Fire Safety Behavior Model for Residential Buildings: Implications for Disaster Risk Reduction. SSRN Electronic Journal 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigg, J.; Christie, N.; Haworth, J.; Osuteye, E.; Skarlatidou, A. Improved methods for fire risk assessment in low-income and informal settlements. International journal of environmental research and public health 2017, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; Zhou, C.; Li, A. Social and Economic Factors' Impact on Fire Safety Risks-Panel Data Model Based Analysis. 2018; pp. 1-5.

- Garcia, D.; Rimé, B. Collective emotions and social resilience in the digital traces after a terrorist attack. Psychological science 2019, 30, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drury, J.; Brown, R.; González, R.; Miranda, D. Emergent social identity and observing social support predict social support provided by survivors in a disaster: Solidarity in the 2010 Chile earthquake. European Journal of Social Psychology 2016, 46, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesio, S.L. International aspects of the disintegration of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Rocznik Instytutu Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej 2021, 19, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikichi, H.; Aida, J.; Tsuboya, T.; Kondo, K.; Kawachi, I. Can community social cohesion prevent posttraumatic stress disorder in the aftermath of a disaster? A natural experiment from the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. American journal of epidemiology 2016, 183, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagans, R.; McEvily, B. Network structure and knowledge transfer: The effects of cohesion and range. Administrative science quarterly 2003, 48, 240–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachinger, G.; Renn, O.; Begg, C.; Kuhlicke, C. The risk perception paradox—implications for governance and communication of natural hazards. Risk analysis 2013, 33, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kašťáková, E.; Chlebcová, A. Analysis of the Western Balkans Territories Using the Index of Economic Freedom. Studia Commercialia Bratislavensia 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammoh, L.A.; Dawson, I.G.J.; Katsikopoulos, K. How flood preparedness among Jordanian citizens is influenced by self-efficacy, sense of community, experience, communication, trust and training. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2023, 87, 103585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, J.; Toal-Sullivan, D.; Osullivan, T.L. Household emergency preparedness: a literature review. Journal of community health 2012, 37, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Martek, I.; Wang, G. Impacts of earthquake knowledge and risk perception on earthquake preparedness of rural residents. Natural Hazards 2021, 107, 1287–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, J. Stories of tragedy, trust and transformation? A case study of education-centered community development in post-earthquake Haiti. Progress in Planning 2018, 124, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtob, D.A. Remembering the future: Natural disaster, place, and symbolic survival. Rural sociology 2019, 84, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsizadeh, F.; Ibrion, M.; Mokhtari, M.; Lein, H.; Nadim, F. Bam 2003 earthquake disaster: On the earthquake risk perception, resilience and earthquake culture–Cultural beliefs and cultural landscape of Qanats, gardens of Khorma trees and Argh-e Bam. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2015, 14, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesa, B.W.; Steyn, G.S.; Otieno, F.A.O.F. A review of physical and socio-economic characteristics and intervention approaches of informal settlements. Habitat international 2011, 35, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longstaff, P.H.; Armstrong, N.J.; Perrin, K.; Parker, W.M.; Hidek, M.A. Building resilient communities: A preliminary framework for assessment. Homeland security affairs 2010, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, T. Understanding emergency preparedness in public agencies: The key role of managerial perceptions. Administration & Society 2022, 54, 424–450. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković et al. "Comparative Analysis of National Strategies for Protection and Rescue in Emergencies in Serbia and Montenegro with Emphasis on Croatia." 2014 201.

- Baker, E.J. Household preparedness for the aftermath of hurricanes in Florida. Applied Geography 2011, 31, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.N.; Nigg, J.; Louis-Charles, H.M.; Kendra, J.M. Household preparedness in an imminent disaster threat scenario: The case of superstorm sandy in New York City. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2019, 34, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, S.K. Measuring disaster-resilient communities: a case study of coastal communities in Indonesia. Journal of business continuity & emergency planning 2012, 5, 316–326. [Google Scholar]

- Shenk, D.; Ramos, B.; Joyce Kalaw, K.; Tufan, I. History, memory, and disasters among older adults: A life course perspective. Traumatology 2009, 15, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockie, L.; Miller, E. Understanding older adults’ resilience during the Brisbane floods: social capital, life experience, and optimism. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness 2017, 11, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, T.L.; Roberto, K.A.; Kamo, Y. Older adults’ responses to Hurricane Katrina: Daily hassles and coping strategies. Journal of Applied Gerontology 2010, 29, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak, M.A.; Sajib, A.M.; Quader, M.A.; Anjum, H. “We are feeling older than our age”: Vulnerability and adaptive strategies of aging people to cyclones in coastal Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2020, 48, 101595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Agyapong, V.I. The role of social determinants in mental health and resilience after disasters: Implications for public health policy and practice. Frontiers in public health 2021, 9, 658528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timalsina, R.; Songwathana, P. Factors enhancing resilience among older adults experiencing disaster: A systematic review. Australasian emergency care 2020, 23, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, M.; Lee, M.; Tullmann, D. Perceptions of disaster preparedness among older people in South Korea. International journal of older people nursing 2016, 11, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenxia, Z. The community resilience measurement throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond-an empirical study based on data from Shanghai, Wuhan and Chengdu. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2022, 67, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Schaubroeck, J. Organisational crisis-preparedness: The importance of learning from failures. Long range planning 2008, 41, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaş, I. Earthquake risk perception in Bucharest, Romania. Risk Analysis 2006, 26, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Liu, Y.-J.; Shi, Y. Do people feel less at risk? Evidence from disaster experience. Journal of Financial Economics 2020, 138, 866–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Nikolić, N.; Ocal, A.; Martinović, J.; Dragašević, A. A Predictive Model of Pandemic Disaster Fear Caused by Coronavirus (COVID-19): Implications for Decision-Makers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordström, K.; Wangmo, T. Caring for elder patients: Mutual vulnerabilities in professional ethics. Nursing ethics 2018, 25, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sze, J.A.; Gyurak, A.; Goodkind, M.S.; Levenson, R.W. Greater emotional empathy and prosocial behavior in late life. Emotion 2012, 12, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocal, A.; Cvetković, V.M.; Baytiyeh, H.; Tedim, F.; Zečević, M. Public reactions to the disaster COVID-19: A comparative study in Italy, Lebanon, Portugal, and Serbia. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Tanasić, J.; Ocal, A.; Kešetović, Ž.; Nikolić, N.; Dragašević, A. Capacity Development of Local Self-Governments for Disaster Risk Management. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 10406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerulli, D.; Scott, M.; Aunap, R.; Kull, A.; Pärn, J.; Holbrook, J.; Mander, Ü. The role of education in increasing awareness and reducing impact of natural hazards. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttarak, R.; Pothisiri, W. The role of education on disaster preparedness: case study of 2012 Indian Ocean earthquakes on Thailand’s Andaman Coast. Ecology and Society 2013, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Nikolić, N.; Nenadić, R.U.; Ocal, A.; Zečević, M.J.I.J.o.E.R.; Health, P. Preparedness and Preventive Behaviors for a Pandemic Disaster Caused by COVID-19 in Serbia. 2020, 17, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baytiyeh, H. Can disaster risk education reduce the impacts of recurring disasters on developing societies? Education and urban society 2018, 50, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rousan, T.M.; Rubenstein, L.M.; Wallace, R.B. Preparedness for natural disasters among older US adults: a nationwide survey. American journal of public health 2014, 104, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nipa, T.J.; Kermanshachi, S.; Patel, R. Impact of family income on public’s disaster preparedness and adoption of DRR courses. 2020.

- Cvetković, V.; Roder, G.O.A.; Tarolli, P.; Dragićević, S. The Role of Gender in Preparedness and Response Behaviors towards Flood Risk in Serbia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, M. Where to go? Strategic modelling of access to emergency shelters in Mozambique. Disasters 2004, 28, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecere, A.; Monteiro, R.; Ammann, W.J.; Giovinazzi, S.; Santos, R.H.M. Predictive models for post disaster shelter needs assessment. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2017, 21, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, M.; Goonetilleke, A.; Ahankoob, A.; Deilami, K.; Lawie, M. Disaster awareness and information seeking behaviour among residents from low socio-economic backgrounds. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2018, 31, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, G.R.; Tierney, K.J.; Dahlhamer, J.M. Businesses and disasters: Empirical patterns and unanswered questions. Natural Hazards Review 2000, 1, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichlin, M. The role of solidarity in social responsibility for health. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 2011, 14, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, B. Solidarity and care as relational practices. Bioethics 2018, 32, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. Mapping the vulnerability of older persons to disasters. International journal of older people nursing 2010, 5, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelman, A.; Ivey, S.L.; Tseng, W.; Dahrouge, D.; Brune, J.; Neuhauser, L. Responding to the deaf in disasters: establishing the need for systematic training for state-level emergency management agencies and community organizations. BMC health services research 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Montenegro n (%) | North Macedonia n (%) | Serbia n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 197 (49.3) | 148 (42.9) | 212 (42.2) |

| Female | 203 (50.7) | 197 (57.1) | 288 (57.6) | |

| Age | Up to 20 20-30 30-40 40-50 Over 50 |

36 (9) 141 (35.3) 107 (26.8) 57 (14.2) 59 (14.8) |

109 (31.6) 136 (39.4) 56 (16.2) 28 (8.1) 16 (4.6) |

80 (16) 180 (36) 140 (28) 70 (14) 30 (6) |

| Education | Secondary school Higher education Bachelor's degree Master's degree Doctorate |

159 (39.8) 25 (6.3) 146 (36.5) 38 (9.5) 17 (4.3) |

176 (51.01) 30 (8.7) 100 (28.9) 29 (8.41) 10 (2.90) |

225 (45) 50 (10) 150 (30) 55 (11) 20 (4) |

| Marital status | Single In a relationship Engaged Married Divorced |

138 (34.5) 96 (24) 16 (4) 120 (30) 24 (6) |

120 (34.7) 102 (29.5) 8 (2.32) 105 (30.4) 10 (2.9) |

144 (28.8) 122 (24.4) 4 (0.8) 216 (43.2) 14 (2.8) |

| Employment | Employed Unemployed |

298 (74.6) 102 (25.5) |

161 (46.7) 180 (52.2) |

202 (40.8) 296 (59.2) |

| Ownership of property | Personal Family member's Rented |

121 (30.3) 227 (56.8) 47 (11.8) |

60 (17.4) 241 (69.9) 32 (9.3) |

92 (18.4) 342 (68.4) 66 (13.2) |

| Household income | Up to 450 From 450 to 700 From 700 to 1000 Over 1000 |

23 (5.8) 64 (16) 126 (31.5) 187 (46.8) |

84 (24.3) 72 (20.9) 117 (33.9) 56 (16.2) |

72 (14.4) 162 (32.4) 206 (41.2) 60 (12) |

| Parenthood | Yes No |

172 (42.9) 228 (57.1) |

109 (31.5) 236 (68.4) |

180 (36) 320 (64) |

| Success in high school | Good Very good Excellent |

70 (17.5) 150 (37.5) 180 (45) |

24 (6.9) 68 (19.7) 253 (73.3) |

45 (9) 178 (35.6) 277 (55.4) |

| Disability | Yes No |

25 (6.3) 375 (93.7) |

15 (4.3) 330 (95.7) |

31 (6.2) 469 (93.8) |

| Variables | Countries | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montenegro Yes/No (%) |

North Macedonia Yes/No (%) | Serbia Yes/No (%) |

||

| Designated shelter nearby | 16/84 | 18.9/81.1 | 25.2/74.8 | 20.1/79/9 |

| Route to shelter | 15.8/84.2 | 37.1/62.9 | 25.6/74.4 | 26.16/73.84 |

| Obstacle on route to shelter | 15/85 | 66.9/33.1 | 14.5/85.5 | 32.13/67.87 |

| Neighbour alert before evacuation | 76.8/23.2 | 75.7/24.3 | 94/6 | 82.16/17.84 |

| Shelter condition | 9.5/80.5 | 18.6/81.4 | 23.6/76.4 | 17.2/82.8 |

| Shelter management | 6.8/93.2 | 17.4/82.6 | 15.6/84.4 | 13.26/86.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).