Submitted:

20 March 2024

Posted:

20 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Enhancement of Photocatalytic Efficiency

2.1. Element Doping

2.2. Heterojunction Construction

2.3. Other Improvement Strategies

2.3.1. Sensitizers

2.3.2. Defect Engineering

2.3.3. Surface Modification and Morphology Control

2.3.4. Nobel Metal Deposition (Plasmonic Photocatalysts)

2.4. Photocatalysts with Support Materials

3. Photocatalytic Mechanisms in Nanomaterial-Mediated Plastic Degradation

3.1. Techniques Used to Investigate Mechanisms

3.2. Mechanism of Photocatalysis

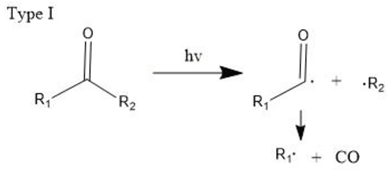

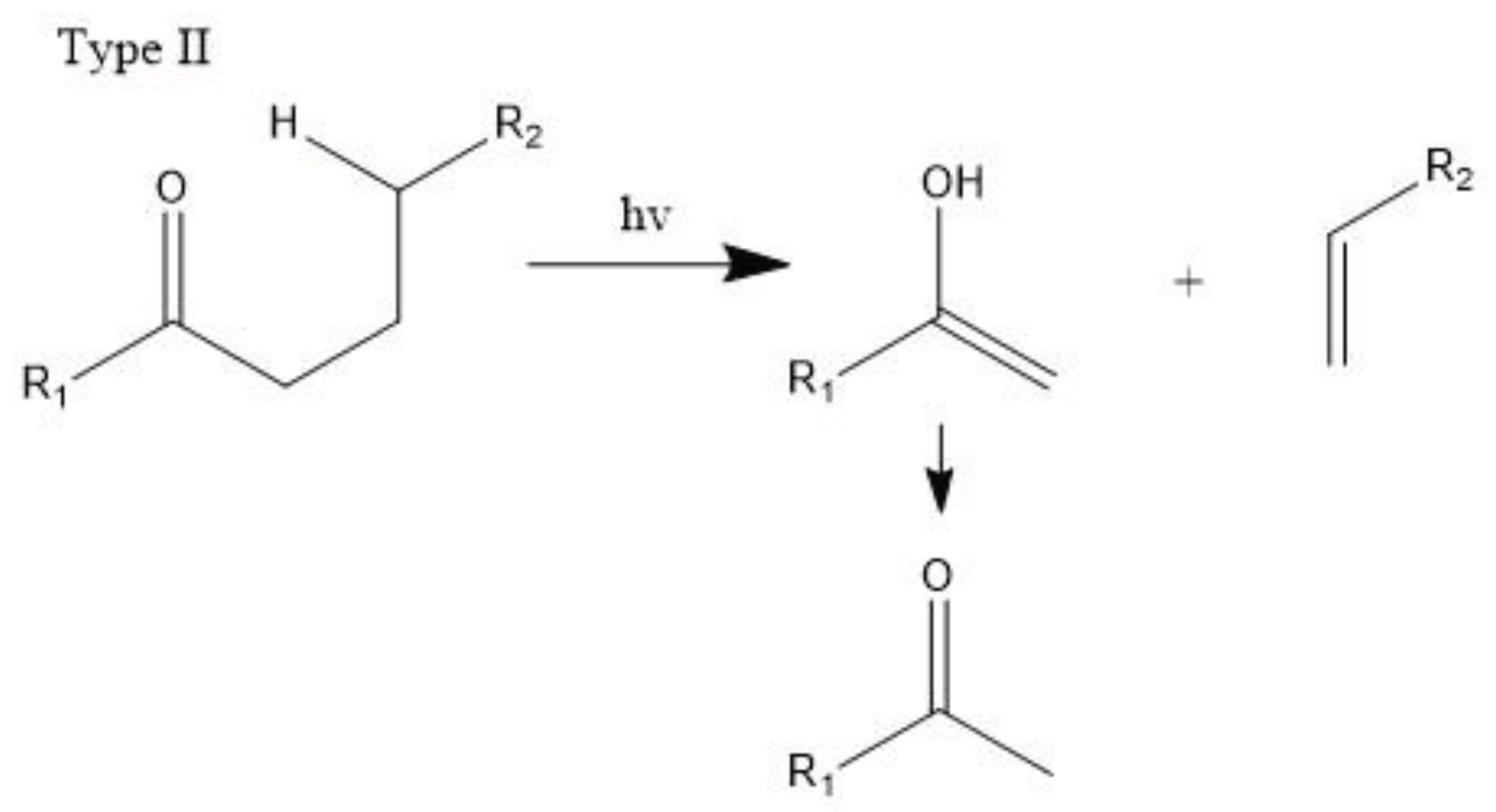

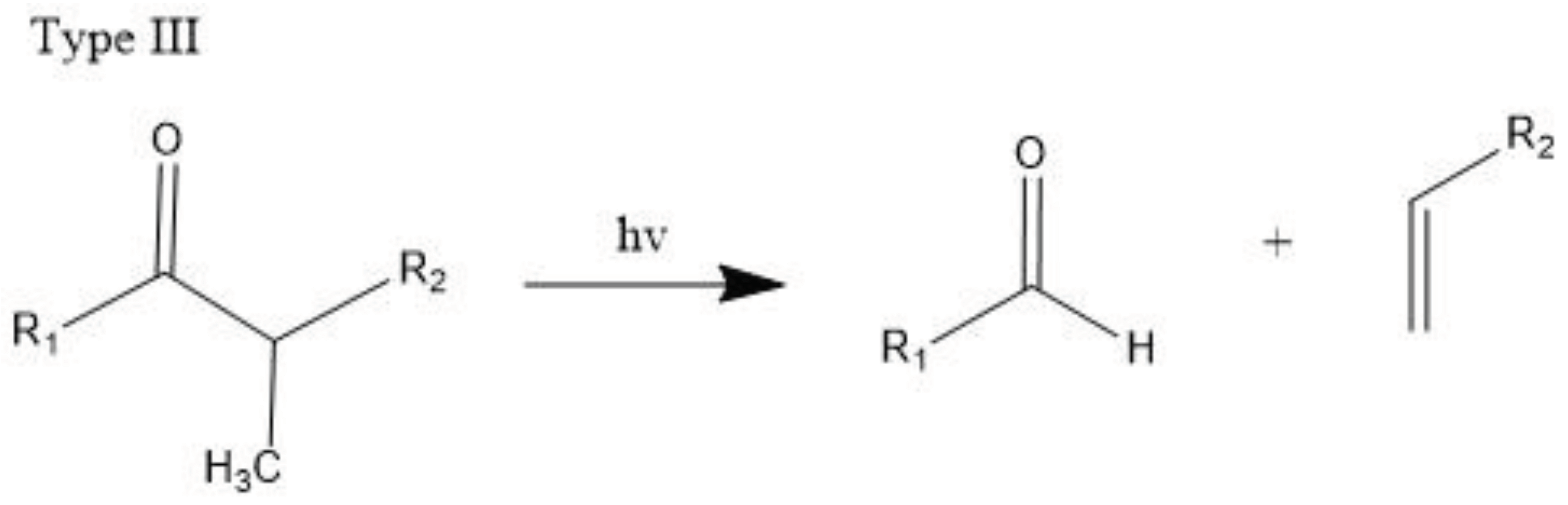

3.2.1. Free Radical Mechanism

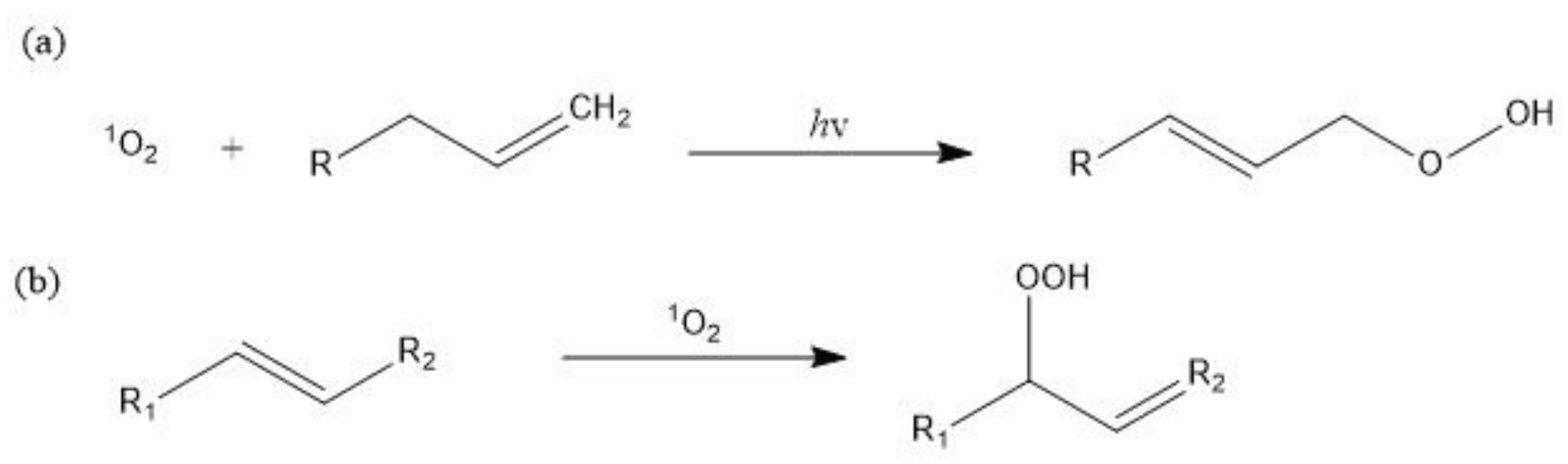

3.2.2. Singlet Oxygen Oxidation Mechanism

4. Conclusion and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD iLibrary Plastics Use in 2019 Available online:. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/data/global-plastic-outlook/plastics-use-in-2019_efff24eb-en (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Häder, D.-P.; Banaszak, A.T.; Villafañe, V.E.; Narvarte, M.A.; González, R.A.; Helbling, E.W. Anthropogenic Pollution of Aquatic Ecosystems: Emerging Problems with Global Implications. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 713, 136586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erren, T.; Zeuß, D.; Steffany, F.; Meyer-Rochow, B. Increase of Wildlife Cancer: An Echo of Plastic Pollution? Nat Rev Cancer 2009, 9, 842–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machovsky-Capuska, G.E.; Amiot, C.; Denuncio, P.; Grainger, R.; Raubenheimer, D. A Nutritional Perspective on Plastic Ingestion in Wildlife. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 656, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; Huang, W.; Chen, M.; Song, B.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y. (Micro)Plastic Crisis: Un-Ignorable Contribution to Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Change. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 254, 120138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhatib, D.; Oyanedel-Craver, V. A Critical Review of Extraction and Identification Methods of Microplastics in Wastewater and Drinking Water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 7037–7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.L.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S. The Physical Impacts of Microplastics on Marine Organisms: A Review. Environmental Pollution 2013, 178, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermabessiere, L.; Dehaut, A.; Paul-Pont, I.; Lacroix, C.; Jezequel, R.; Soudant, P.; Duflos, G. Occurrence and Effects of Plastic Additives on Marine Environments and Organisms: A Review. Chemosphere 2017, 182, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazouli, M.; Nejati, H.; Hashempour, Y.; Dehbandi, R.; Nam, V.T.; Fakhri, Y. Occurrence of Microplastics (MPs) in the Gastrointestinal Tract of Fishes: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 815, 152743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Pedriza, A.; Jaumot, J. Interaction of Environmental Pollutants with Microplastics: A Critical Review of Sorption Factors, Bioaccumulation and Ecotoxicological Effects. Toxics 2020, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, X.; Soo, H.S.; Wang, F.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, H. Photocatalytic Conversion of Plastic Waste: From Photodegradation to Photosynthesis. Advanced Energy Materials 2022, 12, 2200435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.G.; E. ; Capuska; HTTPS://ORCID.ORG/0000-0001-8698-8424; Andrades, R. Plastic Ingestion as an Evolutionary Trap: Toward a Holistic Understanding. Science 2021, 373, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, H.A.; van Velzen, M.J.M.; Brandsma, S.H.; Vethaak, A.D.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Lamoree, M.H. Discovery and Quantification of Plastic Particle Pollution in Human Blood. Environ Int 2022, 163, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015; 2015; p. Public Law No.114-114 Stat. 3129.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature IUCN 2017 : International Union for Conservation of Nature Annual Report 2017; IUCN, 2018.

- Lin, S.; Huang, H.; Ma, T.; Zhang, Y. Photocatalytic Oxygen Evolution from Water Splitting. Advanced Science 2021, 8, 2002458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; Chen, X.; Han, H.; Li, C. Titanium Dioxide-Based Nanomaterials for Photocatalytic Fuel Generations. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9987–10043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tofa, T.S.; Kunjali, K.L.; Paul, S.; Dutta, J. Visible Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Microplastic Residues with Zinc Oxide Nanorods. Environ Chem Lett 2019, 17, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, R.; Nithya, P.M.; Girish Kumar, S. Noble Metal Deposited Graphitic Carbon Nitride Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts. Applied Surface Science 2020, 508, 145142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.G.; Kavitha, R. A Review on Non Metal Ion Doped Titania for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants under UV/Solar Light: Role of Photogenerated Charge Carrier Dynamics in Enhancing the Activity. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2013, 140–141, 559–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Lin, S.; Ren, K.; Li, C.; Zhang, F. Revealing the Effects of Transition Metal Doping on CoSe Cocatalyst for Enhancing Photocatalytic H2 Production. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2023, 328, 122503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Ullah, R.; Butt, A.M.; Gohar, N.D. Strategies of Making TiO2 and ZnO Visible Light Active. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2009, 170, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Zhang, N.; Gao, C.; Xiong, Y. Defect Engineering in Photocatalytic Materials. Nano Energy 2018, 53, 296–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurišić, A.B.; Leung, Y.H.; Ng, A.M.C. Strategies for Improving the Efficiency of Semiconductor Metal Oxide Photocatalysis. Mater. Horiz. 2014, 1, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Lin, H.; Song, H.; Yang, L.; Tang, D.; Deng, F.; Ye, J. Efficient and Selective Photocatalytic CH4 Conversion to CH3OH with O2 by Controlling Overoxidation on TiO2. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Fabrication of a Novel High Photocatalytic Ag/Ag3PO4/P25 (TiO2) Heterojunction Catalyst for Reducing Electron-Hole Pair Recombination and Improving Photo-Corrosion. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 065515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ma, W.; Chen, C.; Zhao, J.; Shuai, Z. Efficient Degradation of Toxic Organic Pollutants with Ni2O3/TiO2-XBx under Visible Irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 4782–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, T.; Fujishima, A.; Konishi, S.; Honda, K. Photoelectrocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide in Aqueous Suspensions of Semiconductor Powders. Nature 1979, 277, 637–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habisreutinger, S.N.; Schmidt-Mende, L.; Stolarczyk, J.K. Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 on TiO2 and Other Semiconductors. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2013, 52, 7372–7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.-C.; Li, J.-R.; Lv, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Guo, G. Photocatalytic Organic Pollutants Degradation in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Energy & Environmental Science 2014, 7, 2831–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Zhu, J. DEGRADATION OF ORGANIC POLLUTANTS IN FLOCCULATED LIQUID DIGESTATE USING PHOTOCATALYTIC TITANATE NANOFIBERS: MECHANISM AND RESPONSE SURFACE OPTIMIZATION. Front. Agr. Sci. Eng. 2023, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Tian, Y.; Gao, M.; Cheng, F.; Lan, J.; Chen, H.; Lanoue, M.; Huang, S.; Tian, R. Efficient Photocatalytic Core/Shell of Titanate Nanowire/RGO 2024.

- Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Tu, W.; Chen, G.; Xu, R. Metal-Free Photocatalysts for Various Applications in Energy Conversion and Environmental Purification. Green Chemistry 2017, 19, 882–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Huang, J. Design, Modification and Application of Semiconductor Photocatalysts. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 2018, 93, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X. Elemental Doping for Optimizing Photocatalysis in Semiconductors. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 12642–12646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Collins, T.; Akhter, A.; Huang, Y.; Tian, Z.R. Mo-Doped Titanate Nanofibers from Hydrothermal Syntheses for Improving Bone Scaffold. Characterization and Application of Nanomaterials 2024, 7, 3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöttner, L.; Erker, S.; Schlesinger, R.; Koch, N.; Nefedov, A.; Hofmann, O.T.; Wöll, C. Doping-Induced Electron Transfer at Organic/Oxide Interfaces: Direct Evidence from Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 4511–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaki, M.R.D.; Shafeeyan, M.S.; Raman, A.A.A.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Application of Doped Photocatalysts for Organic Pollutant Degradation - A Review. Journal of Environmental Management 2017, 198, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, H.; Noguchi, Y.; Miyayama, M. Gap-State Engineering of Visible-Light-Active Ferroelectrics for Photovoltaic Applications. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, P.; Tian, Y.; Thornburgh, S.; Malloy, M.; Roeder, L.; Zhang, L.; Patel, M.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Tian, Z.R. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Valve Metal Ta-Doped Titanate Nanofibers for Potentially Engineering Bone Tissue. Characterization and Application of Nanomaterials 2024, 6, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.K.; Mathpal, M.C.; Kumar, P.; Singh, M.K.; Soler, M.A.G.; Agarwal, A. Structural, Optical and Photoconductivity of Sn and Mn Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2015, 622, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; Peng, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Niu, J.; Zhao, J. A Novel Fe(III) Porphyrin-Conjugated TiO2 Visible-Light Photocatalyst. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2015, 174–175, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, B.; Krishanmurthy, K.R. Nitrogen Incorporation in TiO2: Does It Make a Visible Light Photo-Active Material? International Journal of Photoenergy 2012, 2012, e269654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.J.; Yang, S.; Lee, H. Surface Analysis of N-Doped TiO2 Nanorods and Their Enhanced Photocatalytic Oxidation Activity. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2017, 204, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Zhou, L.; Duan, X.; Sun, H.; Ao, Z.; Wang, S. Degradation of Cosmetic Microplastics via Functionalized Carbon Nanosprings. Matter 2019, 1, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Luo, H.; Zhang, F.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, H. Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of the Persistent PET Fiber-Based Microplastics over Pt Nanoparticles Decorated N-Doped TiO2 Nanoflowers. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2022, 4, 1094–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.; Yu, J.; Jaroniec, M.; Wageh, S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A. Heterojunction Photocatalysts. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1601694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Dou, Y.; Wu, F.; Yao, Y.; Andersen, H.R.; Hélix-Nielsen, C.; Lim, S.Y.; Zhang, W. In-Situ Formation of Ag2O in Metal-Organic Framework for Light-Driven Upcycling of Microplastics Coupled with Hydrogen Production. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2022, 319, 121940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Wu, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhu, K.; Li, Z.; Jin, X.; Hou, Y.; Xi, Q.; Cong, M.; Liu, P.; et al. Combination of Ultrafast Dye-Sensitized-Assisted Electron Transfer Process and Novel Z-Scheme System: AgBr Nanoparticles Interspersed MoO3 Nanobelts for Enhancing Photocatalytic Performance of RhB. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2017, 206, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, A.J. Photoelectrochemistry and Heterogeneous Photo-Catalysis at Semiconductors. Journal of Photochemistry 1979, 10, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, J. Feasible Degradation of Polyethylene Terephthalate Fiber-Based Microplastics in Alkaline Media with Bi2O3@N-TiO2 Z-Scheme Photocatalytic System. Advanced Sustainable Systems 2022, 6, 2100516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J.; Wageh, S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Jaroniec, M. Direct Z-Scheme Photocatalysts: Principles, Synthesis, and Applications. Materials Today 2018, 21, 1042–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Mohamed, A.R.; Ong, W.-J. Z-Scheme Photocatalytic Systems for Carbon Dioxide Reduction: Where Are We Now? Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2020, 59, 22894–22915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Wen, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Yu, Y. Chemically Stable and Reusable Nano Zero-Valent Iron/Graphite-like Carbon Nitride Nanohybrid for Efficient Photocatalytic Treatment of Cr(VI) and Rhodamine B under Visible Light. Applied Surface Science 2016, 386, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Xu, Q.; Low, J.; Jiang, C.; Yu, J. Ultrathin 2D/2D WO3/g-C3N4 Step-Scheme H2-Production Photocatalyst. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2019, 243, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z. In Situ XPS Proved Graphdiyne (CnH2n-2)-Based CoFe LDH/CuI/GD Double S-Scheme Heterojunction Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Evolution. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 311, 123229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ai, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Zhong, D.; Cai, Y.; Johansson, E.; Boschloo, G.; Jin, W.; et al. Magnetic Carbon Nanotube Modified S-Scheme TiO2-x/g-C3N4/CNFe Heterojunction Coupled with Peroxymonosulfate for Effective Visible-Light-Driven Photodegradation via Enhanced Interfacial Charge Separation. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 308, 122897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, B.; Fan, J.; Yu, J. S-Scheme Heterojunction Photocatalyst. Chem 2020, 6, 1543–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelin, C.; Hoffmann, N. Photosensitization and Photocatalysis—Perspectives in Organic Synthesis. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 12046–12055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, M.R. Review: Dye Sensitized Solar Cells Based on Natural Photosensitizers. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Shi, L.; Zhu, Y. Enhancement of Photocatalytic Degradation of Polyethylene Plastic with CuPc Modified TiO2 Photocatalyst under Solar Light Irradiation. Applied Surface Science 2008, 254, 1825–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Gao, X.; Lv, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yin, X.; Liu, Y.; Fang, J.; Yu, X.; Ma, X.; Ma, T.; et al. Decade Milestone Advancement of Defect-Engineered g-C3N4 for Solar Catalytic Applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Lei, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, Y. Defect Engineering in Earth-Abundant Electrocatalysts for CO 2 and N 2 Reduction. Energy & Environmental Science 2019, 12, 1730–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Si, Y.; Li, B.; Yang, L.; Dai, W.; Luo, S. Atomic-Level and Modulated Interfaces of Photocatalyst Heterostructure Constructed by External Defect-Induced Strategy: A Critical Review. Small 2021, 17, 2004980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, M.; Zhang, J.-W.; Wu, Y.-W.; Pan, L.; Shi, C.; Zou, J.-J. Role of Vacancies in Photocatalysis: A Review of Recent Progress. Chemistry – An Asian Journal 2020, 15, 3599–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ni, K.; Ye, J.; Xie, J.; Zhu, Y.; Song, L. Tailoring the Structure of Carbon Nanomaterials toward High-End Energy Applications. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1802104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhang, L.; Du, A.; Gao, G.; Chen, J.; Yan, X.; Brown, C.L.; Yao, X. Defect Graphene as a Trifunctional Catalyst for Electrochemical Reactions. Advanced Materials 2016, 28, 9532–9538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, L.; Yu, G. Synthesis of N-Doped Graphene by Chemical Vapor Deposition and Its Electrical Properties. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 1752–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.P.; Guo, C.; Zheng, Y.; Qiao, S.-Z. Surface and Interface Engineering of Noble-Metal-Free Electrocatalysts for Efficient Energy Conversion Processes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Peng, H.-Q.; Yang, R.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Lee, C.-S.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, W. Iron Vacancies Induced Bifunctionality in Ultrathin Feroxyhyte Nanosheets for Overall Water Splitting. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1803144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tsai, C.; Koh, A.L.; Cai, L.; Contryman, A.W.; Fragapane, A.H.; Zhao, J.; Han, H.S.; Manoharan, H.C.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; et al. Activating and Optimizing MoS2 Basal Planes for Hydrogen Evolution through the Formation of Strained Sulphur Vacancies. Nature Mater 2016, 15, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lv, S.; Shen, Y.; Li, W.; Lin, L.; Li, Z. Advancements in Heterojunction, Cocatalyst, Defect and Morphology Engineering of Semiconductor Oxide Photocatalysts. Journal of Materiomics 2024, 10, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzill, M. Fundamental Aspects of Surface Engineering of Transition Metal Oxide Photocatalysts. Energy & Environmental Science 2011, 4, 3275–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Lu, G.; Yan, Z.; Liu, J.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y. Microplastic Degradation by Hydroxy-Rich Bismuth Oxychloride. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 405, 124247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, D. Photocatalysis: From Fundamental Principles to Materials and Applications. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 6657–6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, M.W.; Sobhani, H.; Nordlander, P.; Halas, N.J. Photodetection with Active Optical Antennas. Science 2011, 332, 702–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.L.; Liu, R.-S.; Tsai, D.P. Plasmonic Photocatalysis. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2013, 76, 046401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maulana, D.A.; Ibadurrohman, M. ; Slamet Synthesis of Nano-Composite Ag/TiO2 for Polyethylene Microplastic Degradation Applications. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1011, 012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadli, M.H.; Ibadurrohman, M.; Slamet, S. Microplastic Pollutant Degradation in Water Using Modified TiO2 Photocatalyst Under UV-Irradiation. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1011, 012055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Warren, S.; Thimsen, E. Plasmonic Solar Water Splitting. Energy & Environmental Science 2012, 5, 5133–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linic, S.; Christopher, P.; Ingram, D.B. Plasmonic-Metal Nanostructures for Efficient Conversion of Solar to Chemical Energy. Nature Mater 2011, 10, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, S.; Guo, W.; Hu, Y.; Huang, J.; Mulcahy, J.R.; Wei, W.D. Surface-Plasmon-Driven Hot Electron Photochemistry. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2927–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Jiang, R.; Wang, F.; Fang, C.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.C. Plasmon-Enhanced Chemical Reactions. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 5790–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T.R.; Paik, T.; Klein, D.R.; Naik, G.V.; Caglayan, H.; Boltasseva, A.; Murray, C.B. Shape-Dependent Plasmonic Response and Directed Self-Assembly in a New Semiconductor Building Block, Indium-Doped Cadmium Oxide (ICO). Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 2857–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Kriegel, I.; Milliron, D.J. Shape-Dependent Field Enhancement and Plasmon Resonance of Oxide Nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 6227–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchala, S.; Elayappan, V.; Lee, H.-G.; Shanker, V. Chapter 7 - Plasmonic Photocatalysis: An Extraordinary Way to Harvest Visible Light. In Photocatalytic Systems by Design; Sakar, M., Balakrishna, R.G., Do, T.-O., Eds.; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 187–216 ISBN 978-0-12-820532-7.

- M’Bra, I.C.; García-Muñoz, P.; Drogui, P.; Keller, N.; Trokourey, A.; Robert, D. Heterogeneous Photodegradation of Pyrimethanil and Its Commercial Formulation with TiO2 Immobilized on SiC Foams. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2019, 368, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allé, P.H.; Garcia-Muñoz, P.; Adouby, K.; Keller, N.; Robert, D. Efficient Photocatalytic Mineralization of Polymethylmethacrylate and Polystyrene Nanoplastics by TiO2/β-SiC Alveolar Foams. Environ Chem Lett 2021, 19, 1803–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, I.; Bacha, A.-U.-R.; Li, K.; Cheng, H.; Wang, T.; Liu, Y.; Ajmal, S.; Yang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, L. Complete Photocatalytic Mineralization of Microplastic on TiO2 Nanoparticle Film. iScience 2020, 23, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Peng, X.; Xue, J.; Wei, Y.; Sun, Y.; Dai, Y. A Biomass-Derived, All-Day-Round Solar Evaporation Platform for Harvesting Clean Water from Microplastic Pollution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 11013–11024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, I.A.; Alberto, E.A.; Silva Júnior, A.H.; Macuvele, D.L.P.; Padoin, N.; Soares, C.; Gracher Riella, H.; Starling, M.C.V.M.; Trovó, A.G. A Critical Review on Microplastics, Interaction with Organic and Inorganic Pollutants, Impacts and Effectiveness of Advanced Oxidation Processes Applied for Their Removal from Aqueous Matrices. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 424, 130282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, H.; Fan, Q.; Xiong, F.; Liu, S.; Li, D.-S.; Liu, B. Halide Perovskite Composites for Photocatalysis: A Mini Review. EcoMat 2021, 3, e12079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Choi, W. Solid-Phase Photocatalytic Degradation of PVC–TiO2 Polymer Composites. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2001, 143, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Xiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, X. Photocatalytic Aging Process of Nano-TiO2 Coated Polypropylene Microplastics: Combining Atomic Force Microscopy and Infrared Spectroscopy (AFM-IR) for Nanoscale Chemical Characterization. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 404, 124159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Chen, Q.; Jiang, W.; Wang, L.; Xie, H.; Kalogerakis, N.; Ma, Y.; Ji, R. A Carbon-14 Radiotracer-Based Study on the Phototransformation of Polystyrene Nanoplastics in Water versus in Air. Environmental Science: Nano 2019, 6, 2907–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Chai, M.; Zhu, Y. Solid-Phase Photocatalytic Degradation of Polystyrene Plastic with TiO2 as Photocatalyst. Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2003, 174, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Chai, M.; Zhu, Y. Photocatalytic Degradation of Polystyrene Plastic under Fluorescent Light. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 4494–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, P.; Wu, X.; Shi, H.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Gao, S. Insight into Chain Scission and Release Profiles from Photodegradation of Polycarbonate Microplastics. Water Research 2021, 195, 116980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajire, A.A.; Mohammed, A.A. Green Synthesis of Palladium Nanoparticles Using Ananas Comosus Leaf Extract for Solid-Phase Photocatalytic Degradation of Low Density Polyethylene Film. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2019, 7, 103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramana, C.; Botsa, S.M.; Shyamala, P.; Muralikrishna, R. Photocatalytic Degradation of Polyethylene Plastics by NiAl2O4 Spinels-Synthesis and Characterization. Chemosphere 2021, 265, 129021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.K.; Surekha, P.; Rajagopal, C.; Chatterjee, S.N.; Choudhary, V. Studies on the Photo-Oxidative Degradation of LDPE Films in the Presence of Oxidised Polyethylene. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2007, 92, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Q.Y.; Li, H. Photocatalytic Degradation of Plastic Waste: A Mini Review. Micromachines (Basel) 2021, 12, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrycay, E.G.; Bandiera, S.M. Chapter Two - Involvement of Cytochrome P450 in Reactive Oxygen Species Formation and Cancer. In Advances in Pharmacology; Hardwick, J.P., Ed.; Cytochrome P450 Function and Pharmacological Roles in Inflammation and Cancer; Academic Press, 2015; Vol. 74, pp. 35–84.

- Rabek, J.F.; Rånby, B. The Role of Singlet Oxygen in the Photooxidation of Polymers. Photochemistry and Photobiology 1978, 28, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R. Photosensitized Generation of Singlet Oxygen. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2006, 82, 1161–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Zhu, B.; Cheng, B.; Macyk, W.; Wang, L.; Yu, J. Catalytic Conversion of Styrene to Benzaldehyde over S-Scheme Photocatalysts by Singlet Oxygen. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, E.; Haddad, R. Photodegradation and Photostabilization of Polymers, Especially Polystyrene: Review. Springerplus 2013, 2, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Sharma, N. Mechanistic Implications of Plastic Degradation. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2008, 93, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).