1. Introduction

Farmed salmon constitutes Canada's third-largest seafood export by value, accounting for over 70% of the total production volume and more than 80% of the overall farm-gate value. While salmon cultivation occurs in Atlantic Canada, the primary hub of the industry is in British Columbia, the largest agri-food export region. Salmon aquaculture in British Columbia commenced in the late 1970s, and by 2021, the industry produced 84,171 tonnes with an economic value of $692,381,000 (Canadian). The salmon farming sector has played a pivotal role in managing freshwater and marine resources, contributing significantly to the economic and social well-being of coastal communities (Noakes et al., 2002).

Research on salmon has consistently been a focal point in the domain of consumer perception analysis. Osmond et al. (2023) conducted an exploratory investigation into Canadian consumer perceptions and behaviors regarding salmon. Zheng et al. (2023) employed a Random Parameters Logit (RRL) model to scrutinize heterogeneity in preferences, integrating perceptions of genetically modified (GM) farmed salmon. Grundvåg Ottesen (2006) provided valuable insights into Norwegian consumer perceptions of salmon, while Gaedeke (2001) explored perceptions regarding both wild-caught and farmed salmon. Numerous studies have delved into the influence of information on consumer perceptions and behavior. Qin and Brown (2006) investigated the impact of process and product-related information, Budhathoki et al. (2021) delved into the provision of production method information, Nickoloff et al. (2007) explored the effects of conflicting health information, Onozaka et al. (2023) focused on geographic origin information coupled with sustainable measures, Whitmarsh and Palmieri (2011) examined environmental preferences, and Muñoz-Colmenero et al. (2017) identified economic reasons favoring wild-caught over farmed products as primary drivers. Moreover, research has explored the intricate relationship between perception and behavior. Onozaka et al. (2014) employed Latent Class Analysis (LCA) embedded in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to study the impact of perceptions of healthiness, value for money, and convenience on salmon consumption frequencies. Zheng et al. (2018) utilized an ordered logit model to investigate perceptions of consumption attributes (clean, tasty, nutritious) and their influence on the purchase habits of Alaskan salmon. Suzuki et al. (2019) employed SEM to explore the post-disaster consumer perception effect on seafood purchase intent. Zheng et al. (2021) applied the RPL model to assess Chinese consumers' willingness to pay, incorporating perceptions of the production environment and food safety attributes. Alfnes et al. (2006) designed 20 choice scenarios with posted prices to investigate consumers' willingness to pay for the color of salmon using a mixed logit model. Myrland et al. (2004) applied the Fishbein-Ajzen approach to study consumer perception and the frequency of Norwegian salmon consumption. This extensive research is indispensable for the thriving Canadian salmon industry.

However, in early 2023, the Canadian government chose not to renew licenses for 15 salmon farms around British Columbia's Discovery Islands, following a prior decrease in license issuances by 22 in 2022 (Government of Canada, 2024). This policy shift within the salmon farming industry resulted in an approximate 25% reduction in the total number of salmon farms in British Columbia (CAIA, 2023). This governmental intervention carries noteworthy implications. Primarily, it is poised to create a scarcity of Canadian salmon, leading to a 13% reduction in exports and a decline in Canada's market share within the US market. Furthermore, this regulatory measure is anticipated to trigger a 12.7% increase in the retail price of Canadian salmon (CAIA, 2023), potentially prompting Canadian consumers to substitute domestically farmed salmon with imports or other seafood. Considering that salmon holds the first position in Canada's seafood choices (Nourish Food Marketing, 2022), such a shift may adversely impact Canadians' consumption satisfaction. Additionally, the ensuing escalation in potential adverse effects has reverberations on employment and income levels within Canadian coastal and Indigenous communities (BCSFA, 2023; CAIA, 2023). Specifically, more than 300 Mowi workers will lose their jobs due to this shutdown order (BIV, 2023).

Salmon has also been intrinsically linked to Indigenous livelihood and culture for centuries. Notably, the historical entwinement of Alaska Natives with salmon extends beyond 10,000 years (Carothers et al., 2021). However, recent decades have borne witness to a decline in wild salmon populations attributed to multifaceted factors, including climate change, overfishing, and diseases (Jacob et al., 2010). While the Fisheries Act prioritizes Indigenous ceremonial and subsistence fishing, the loss of cultural diversity has not received the same attention as the loss of biological diversity (Ween & Colombi, 2013). Research conducted by Carothers et al. (2021) highlighted the impending threats to the sustainability of six Sugpiaq villages in the Kodiak Archipelago due to lost fisheries access and the cumulative impacts of restricted access management. Similarly, Steel et al. (2021) underscored the mounting challenges faced by Haíłzaqv Nation fishers in accessing salmon within their traditional territories due to escalating fuel costs and boat maintenance fees.

Building upon insights derived from prior research and recognizing the decline in salmon farm licenses in British Columbia, this study aims to address a critical gap by incorporating consumers' perceptions of Indigenous rights within the Canadian salmon industry. The objectives of this research include (1) attaining a comprehensive understanding of four consumer perceptions—namely, environmental sustainability, economic considerations, Indigenous rights, and price increase—across diverse consumer profiles through a cross-national online survey; (2) identifying factors that influence these four consumer perceptions; and (3) assessing the impact of these four perceptions, in conjunction with socio-demographic variables and consumer motivations (with specific emphasis on the perceived importance of price and perceived importance of origin), on seven purchasing behaviors concerning Canadian salmon products. To facilitate the dimension reduction of perception sub-domains and capture latent information from all questionnaire items using a more limited number of features, the Graded Response Model (GRM) is employed. Additionally, the intricate analysis is conducted using Cumulative Link Models (Schmidt, 2012).

This study is strategically positioned to provide valuable insights for both policymakers and stakeholders within the salmon industry. By leveraging the findings of this research, policymakers can effectively navigate the complex challenge of balancing environmental sustainability with Indigenous rights in the formulation of salmon farm licensing policies. This sophisticated approach could involve the development of policies that endorse a sustainable number of licenses for farmed salmon production, not only catering to established consumer demand but also incorporating culturally sustainable measures to support the livelihoods and employment opportunities of Indigenous communities, including Indigenous-led programs and the sustainable expansion of farm salmon licenses. Given its significance as an economic driver for Canadian aquaculture and seafood production (BCSFA, 2023), this balanced approach is crucial for bolstering the salmon sector's contribution to Canada's Blue Economy Strategy. Stakeholders, in turn, will gain a comprehensive understanding of purchasing behaviors aligned with consumer perceptions, enabling informed adjustments to enhance market strategies accordingly.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection

Data collection for this study was conducted through a transnational online survey administered from January 8th to January 15th, 2024. The survey employed a sample size of 1,101 Canadian residents, selected using a randomized approach within regions of Canada, including British Columbia, the Prairies, Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic provinces. Angus Reid was entrusted with survey administration to facilitate the random selection of participants. To ensure comprehensive representation across age and gender categories within each region, the determination of the sample for each was guided by the imperative to align with the data guidelines established by Statistics Canada in 2020. Participation in the survey was entirely voluntary, and individuals who chose to participate received an electronic message containing a comprehensive survey description along with the link to access it. Throughout the entire survey process, the anonymity of participants was maintained.

Before the official commencement of the online survey, a translation of all questions into French was undertaken, accompanied by subsequent adjustments and verification. The questionnaire encompasses 2 items featuring agreement-based questions, 1 open-ended question, 10 socio-demographic queries, and 34 Likert scale questions. For this study, exclusive focus is given to closed questions. A copy of the questionnaire is appended in

Appendix S1 of the Supplementary Material.

2.2. Descriptive Statistics

Originally, 1,101 independent observations were obtained through the survey. Question 1 was designed to determine eligibility, requiring participants to confirm that they were over 18 years old and had resided in Canada for the last 12 months. Question 2 aimed to assess participants’ understanding of the survey. Consequently, the dataset underwent refinement by excluding responses marked as 'disagree' in either Question 1 or Question 2. Furthermore, one instance of missing data in one of the Likert scale questions was removed, resulting in a final sample size of 1,078. Notably, the category 'Raw foodist (a diet consisting mainly of raw fruits, vegetables, legumes, sprouts, and nuts)' was consolidated with the 'Other' category due to the presence of only one observation. Frequencies for socio-demographics are detailed in

Table 1.

We also have encoded the 34 Likert questions from Q2 to Q35 as follows: ‘1’ for ‘strongly disagree’, ‘2’ for ‘disagree’, ‘3’ for ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘4’ for ‘agree’, and ‘5’ for ‘strongly agree’.

Table 2 provides frequencies for these 34 variables.

2.3. Statistic Models

2.3.1. Graded Response Model

When each increasing option of questions reflects increasing levels of the perception domain, the Graded Response Model (GRM) (van der Linden and Hambleton, 2013) can be used to summarize all questions in the domain. Suppose a perception domain has items with each item has possible options for . Then the GRM estimate the probabilities of answering through where represents the answer of the respondent, is a -dimensional latent trait used to characterize the domain, is a latent continuous variable for item and are the corresponding threshold parameters to be estimated. The relationship between the latent trait and the latent variable can be written as where , is the slope matrix with rows and columns, and is a -dimensional Gaussian random vector.

Given the observations for the perception domain, the GRM estimates for each item by estimating the slope matrix and the thresholds parameters . The resulting curves of for are called trace plot of item , indicating how the probability of responding to item will change according to the change of the latent trait . Once slope matrix and the thresholds parameters are estimated, the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimator of latent trait can be obtained by maximizing the posterior distribution of given and for each participant . The resulting MAP estimator of is defined as the measurement of the level of the perception domain in this paper.

2.3.2. Multiple Linear Regression

If the latent trait is a scalar, i.e. , then it can be used as a continuous outcome for a multiple linear regression model and fitted by the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation. The variables of the perceived importance of price (Q13) and the perceived importance of origin (Q14) are dichotomized by combining the answers 'Strongly disagree,' 'Disagree', and 'Neither agree nor disagree' into the category 'Do not perceive as important', while the answers 'Agree' and 'Strongly agree' are combined into the category 'Perceive as important'. The new transformations are defined as and . To study the relationship between perception domains and consumer profiles, the following regression model is estimated: , where is the intercept. The socio-demographic variables (question D1-D9 and Q1) are all transformed into binary dummy variables.

2.3.3. Logistic Regression

The perception of a price increase (Q34) is dichotomized by combining the answers 'Strongly disagree', 'Disagree', and 'Neither agree nor disagree' into the category 'Do not perceive a price increase', while the answers 'Agree' and 'Strongly agree' are combined into the category 'Perceive a price increase'. The new transformation is defined as . Hence, the percentage of perceive a price increase can be analyzed using logistic regression: , where is the intercept. The socio-demographic variables (question D1-D9 and Q1) are all transformed into binary dummy variables.

2.3.4. Cumulative Link Model

The consumer purchasing behavior is analyzed using the cumulative link model (CLM) (Schmidt, 2012) with the logistic link function:

where

is respondent

’s answer to the question related to consumer purchasing behavior,

is the threshold parameter,

,

, and

are the latent traits of environmental sustainability, economical considerations, and Indigenous rights obtained by the GRM. All analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.2).

3. Results

3.1. Cronbach’s Alpha Reliability Test

The Likert scale questions demonstrate a robust level of internal consistency, as evidenced by Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.852, 0.795, and 0.923 in

Table 3 for each sub-domain (environmental sustainability, economic considerations, and Indigenous rights). Surpassing the commonly accepted threshold of 0.7 for internal consistency, these obtained values (0.852, 0.795, 0.923) indicate a notably high degree of reliability in this survey.

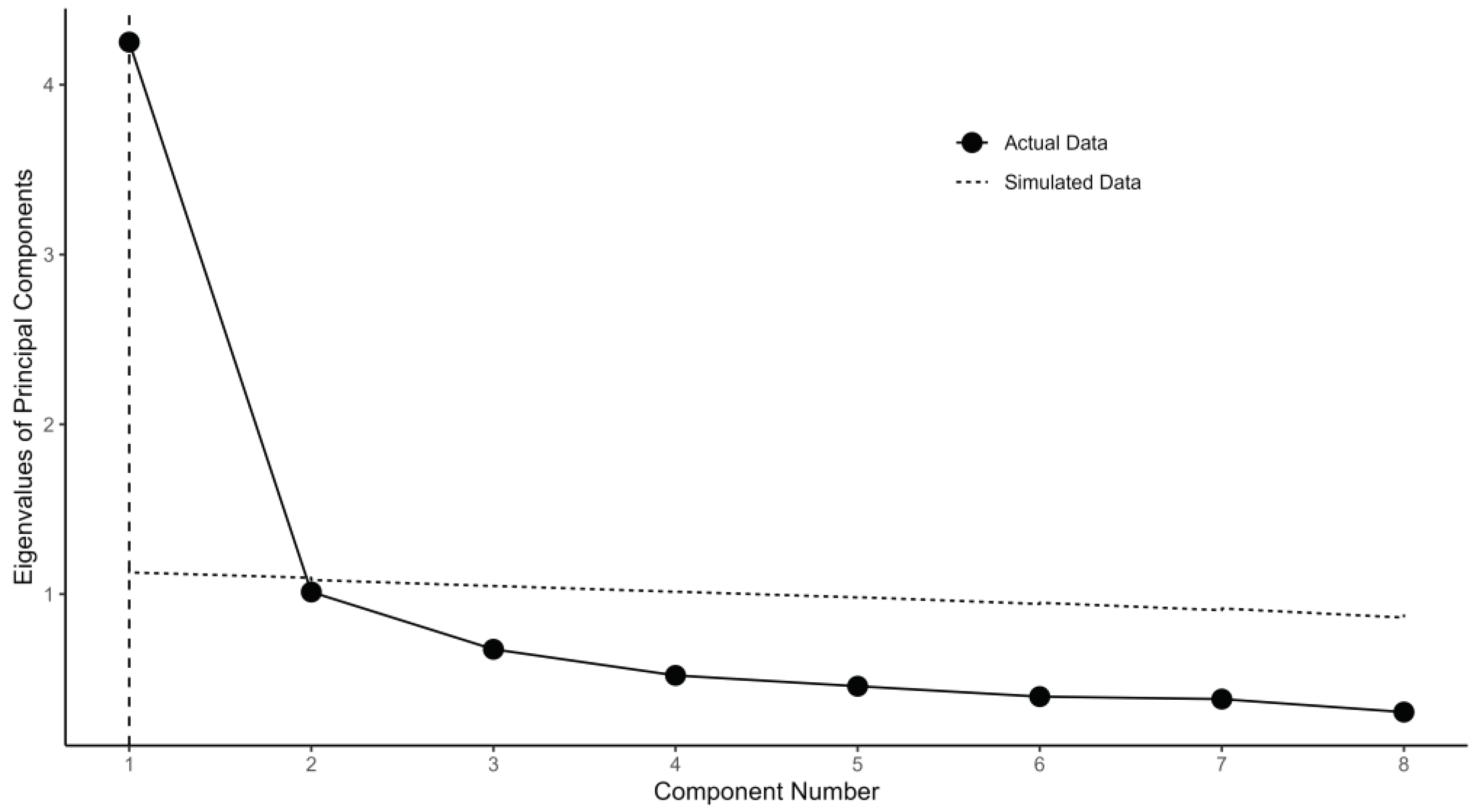

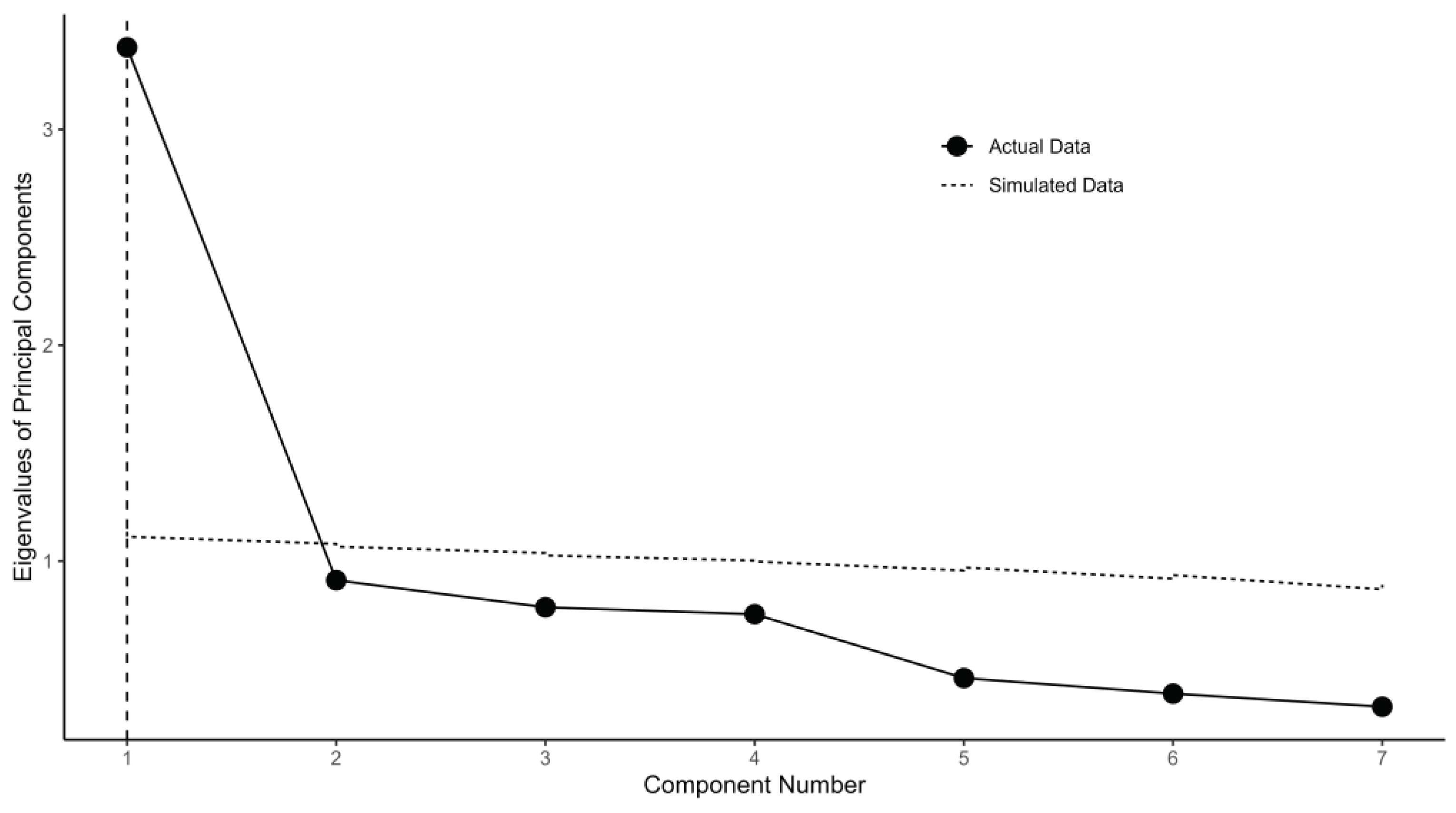

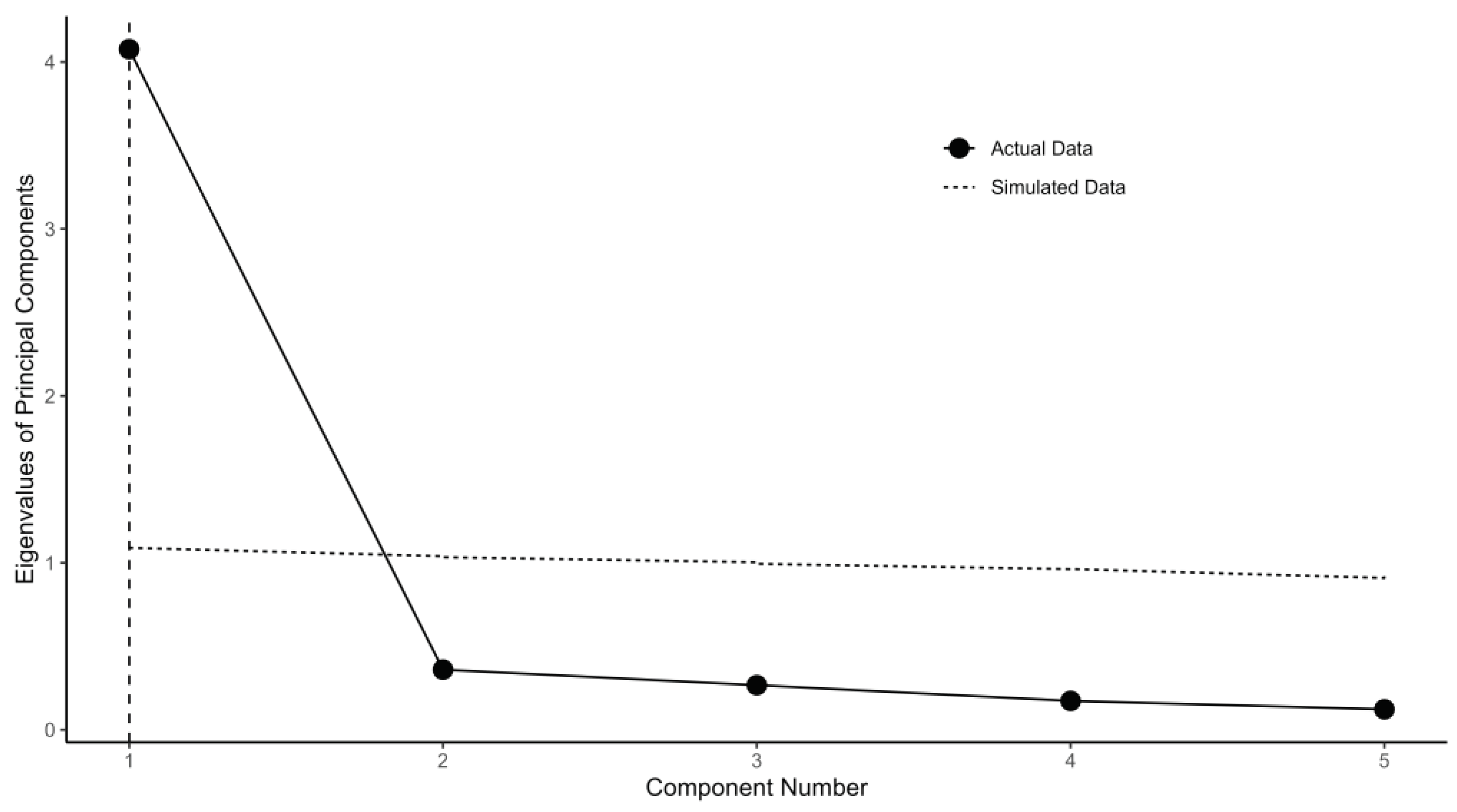

3.2. Dimensionality Test: Parallel Analysis

The parallel analysis is used to determine , the dimension of the latent traits for each domain. The parallel analysis generates simulated random matrices for obtaining the eigenvalues from the principal component analysis (PCA). The lowest component number for which the minimal PCA eigenvalue from the actual data is below that of the simulated data is chosen as the value of (Horn, 1965).

Figure 1 depicts the comparison between the PCA eigenvalues from actual data of Q19-Q20 and Q22-Q27 (environmental sustainability domain) and randomly simulated data. Note that the blue cross (eigen values of PCA from the actual data) stays below both the red dotted (simulated data) and dashed (resampled data) lines for component number 2-8. This indicates

for the environmental sustainability domain.

Figure 2 depicts the comparison between the PCA eigenvalues from actual data of Q28-Q33 and Q35 (economical consideration domain) and randomly simulated data. Note that the blue cross (eigen values of PCA from the actual data) stays below both the red dotted (simulated data) and dashed (resampled data) lines for component number 2-7. This indicates

for the economical consideration domain.

Figure 3 depicts the comparison between the PCA eigenvalues from actual data of Q11-Q12, Q17, Q24, and Q29 (Indigenous rights domain) and randomly simulated data. Note that the blue cross (eigen values of PCA from the actual data) stays below both the red dotted (simulated data) and dashed (resampled data) lines for component number 2-5. This indicates

for the Indigenous rights domain.

In sum, the dimension is confirmed by the parallel analysis for all three perception domains environmental sustainability, economical consideration, and Indigenous rights. This result simplifies the GRM model to the normal ogive model discussed by Samejima (1968) first.

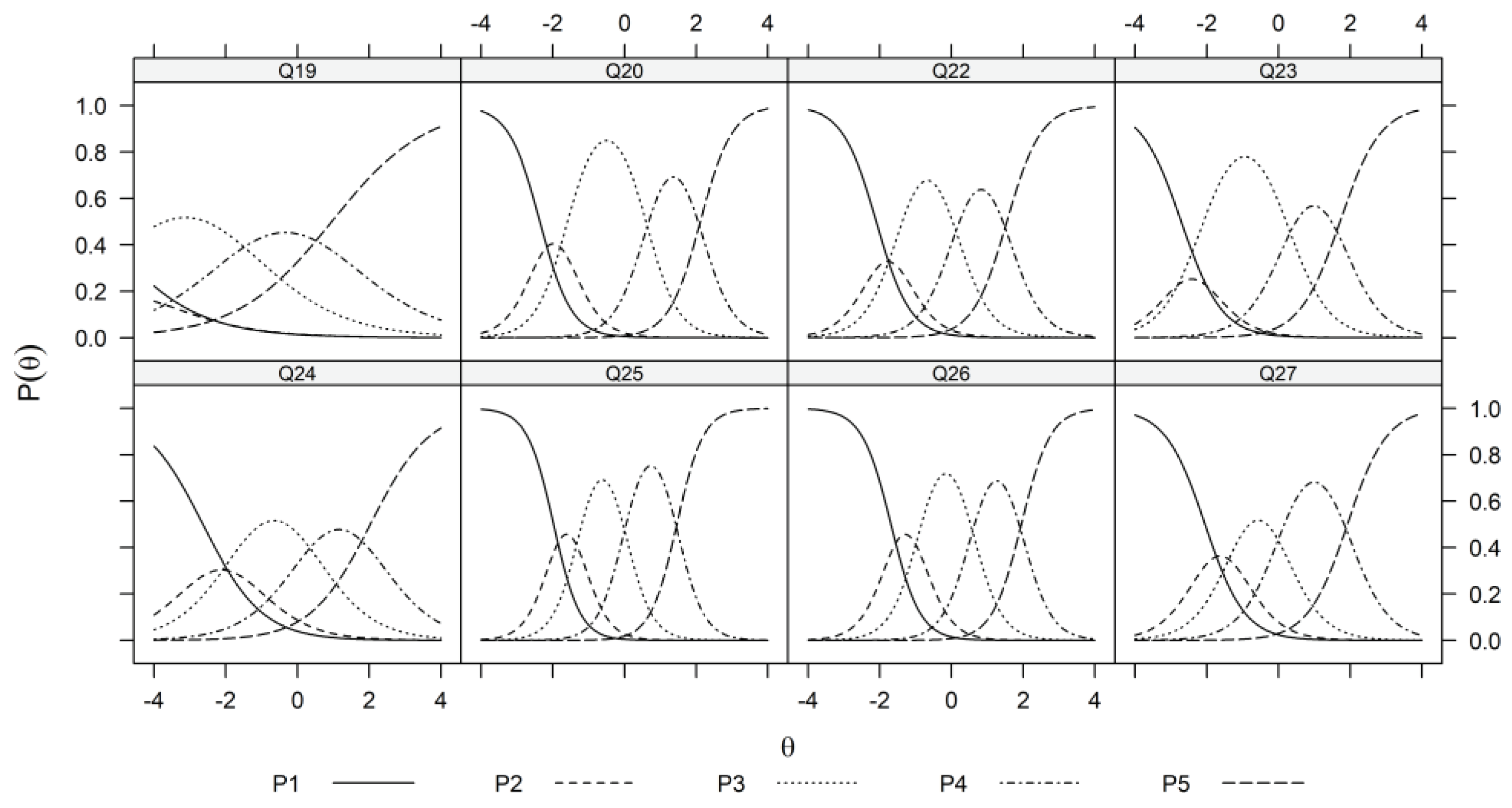

3.3. The GRM Results

As unidimensional graded response model is recommended for developing the latent trait for items Q19, Q20, Q22, Q23, Q24, Q25, Q26, and Q27, for which ‘5’ represent the positive impact of salmon farming on environmental sustainability, the fitted probabilities for answering 1-5 given the latent trait

can be depicted by

Figure 4.

Similarly, the recommended unidimensional graded response model by the parallel analysis develops the latent trait for items Q19, Q20, Q22, Q23, Q24, Q25, Q26, and Q27, for which ‘5’ represent the positive impact of salmon farming on economic consideration, the fitted probabilities for answering 1-5 given the latent trait

can be depicted by

Figure 5.

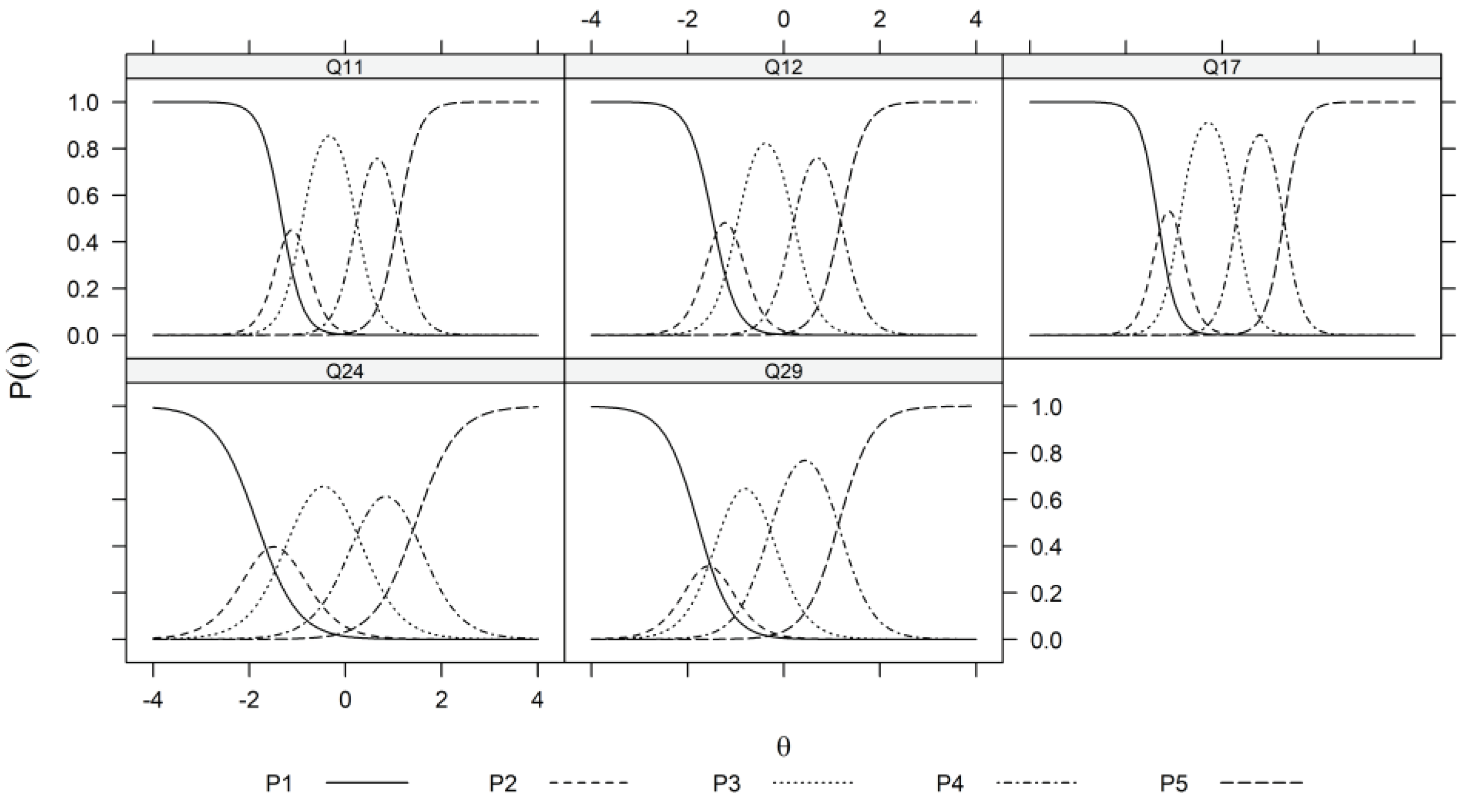

Again, the recommended unidimensional graded response model by the parallel analysis develops the latent trait for items Q11, Q12, Q17, Q24, and Q29, for which ‘5’ represent the positive impact of salmon farming on supporting Indigenous rights, the fitted probabilities for answering 1-5 given the latent trait

can be depicted by

Figure 6.

Note that the trace plots

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 are based on the estimated values

and

. Hence by assuming standard normal priors, the MAP estimation of the latent traits can be obtained for all participants. The resulting values for each perception domain are summarized in

Table 4.

Throughout the rest of the paper, we shall refer to ‘environmental sustainability’ as the MAP estimator of the latent trait , ‘economic considerations’ as the MAP estimator of latent trait , and ‘Indigenous rights’ as the MAP estimator of latent trait for all respondent .

3.4. Perceptions and Consumer Profiles

Linear regression analysis on socio-demographic variables (D1-D9 and Q1),

and

are employed to examine their relationships with consumer perceptions concerning environmental sustainability, economic considerations, Indigenous rights, and price increase. In this subsection, we scrutinize the variations in these perceptions across diverse consumer profiles. The findings are presented in

Table 5.

The results elucidated in

Table 5 unveil the substantial negative influences of dietary preferences (particularly among respondents aligning with categories such as flexitarian, vegan, and others), gender (especially in cases where respondents prefer to withhold disclosure), age, education (specifically those holding a registered apprenticeship or other trades certificate or diploma), and geographic location, specifically focusing on residency within British Columbia, on the perception of environmental sustainability in salmon farming. In contrast, household size, especially those characterized by a single child, and respondents residing in small towns, communities, or rural areas, along with the perceived importance of price and origin, demonstrate conspicuous positive significance in their association with the perception of environmental sustainability in salmon farming.

Table 5 provides additional insights, revealing that dietary preferences (specifically aligning with categories such as flexitarian, vegan, vegetarian, and others), gender (particularly pronounced among non-binary/third-gender respondents and those preferring to withhold disclosure), age (notably within the range of the 1965-1979 bracket), education (especially the possession of a registered apprenticeship or other trades certificate or diploma), and geographic location (specifically for those residing in British Columbia) exert significant negative impacts on the perception of economic considerations. Conversely, household size, especially those with one or two children, geographical location (with respondents residing in Quebec), residential zones (particularly those in urban cores), and the perceived importance of price and origin wield positive influences on the perception of economic considerations.

The results presented in

Table 5 highlight the negative statistical significance of the vegan and other dietary preferences, gender (especially in cases where respondents prefer to withhold disclosure), age (particularly within the range preceding 1979), education (specifically the possession of a registered apprenticeship or other trades certificate or diploma), and geographic location (specifically for those residing in British Columbia) in shaping perception of Indigenous rights. Conversely, gender (especially female), geographical location (with respondents residing in Quebec), residential zones (particularly those in urban cores), and the perceived importance of price and origin manifest significantly positive influences on the perception of Indigenous rights.

Finally, the results in

Table 5 also demonstrate significant negative impacts on the perception of a price increase associated with dietary preferences, specifically lacto-ovo vegetarian and vegetarian preferences. In contrast, respondents' purchase history and the perceived importance of price and origin exhibit significant positive associations with the perception of a price increase.

3.5. Purchasing Behaviors

In this subsection, cumulative link models are employed to examine the impact of socio-demographic variables (D1-D9 and Q1), as well as transformed variables

,

, and

, on consumers' purchasing behaviors. The primary objective is to elucidate the intricate relationship between consumer perceptions and actual purchasing decisions and to evaluate the extent to which concerns related to perceptions of environmental sustainability, economic considerations, Indigenous rights, and price increase influence consumer choices. Seven purchasing behaviors (Q5, Q7, Q8, Q9, Q11, Q17, Q21) are selected as response outcomes. The ensuing results are presented in

Table 6.

The findings presented in

Table 6 highlight the negative statistical significance of pescatarian and vegetarian dietary preferences, as well as gender (particularly female), on the behavior of selecting fresh (never been frozen) salmon over frozen salmon. Conversely, the perception of economic considerations, geographical location (specifically respondents residing in Quebec), residential zones (particularly those in urban cores), respondents' purchase history, the perceived importance of origin, and the perception of a price increase demonstrate significantly positive influences on the behavior of choosing fresh (never been frozen) salmon over frozen salmon. It should be noted that a unit increase in the perception of economic considerations corresponds to a 0.426 increase in such purchase behavior, and a unit increase in the perception of a price increase corresponds to a 0.200 increase.

The findings in

Table 6 underscore the negative statistical significance of lacto-ovo vegetarian, vegan, and vegetarian dietary preferences, as well as income (particularly in the range of

$35,000 and

$49,999), on the behavior of purchasing Canadian-sourced salmon. Conversely, the perception of economic considerations, age (particularly within the range preceding 1979), respondents' purchase history, the perceived importance of origin, and the perception of a price increase demonstrate significantly positive influences on the behavior of purchasing Canadian-sourced salmon. Notably, a unit increase in the perception of economic considerations corresponds to a 0.759 increase in such purchase behavior, and a unit increase in the perception of a price increase corresponds to a 0.275 increase.

The findings in

Table 6 unveil the negative statistical significance of flexitarian, vegetarian, and other dietary preferences, as well as residential zones (particularly those in urban cores), on the behavior of selecting Canadian farm-raised salmon over salmon from another country. Conversely, the perception of environmental sustainability, the perception of economic considerations, age (particularly within the range preceding 1979), income (particularly in the

$100,000 and

$149,999 bracket), the perceived importance of origin, and the perception of a price increase demonstrate significantly positive influences on the behavior of purchasing Canadian farm-raised salmon over salmon from another country. Specifically, a unit increase in the perception of environmental sustainability corresponds to a 0.432 increase in such purchase behavior, a unit increase in the perception of economic considerations is linked to a 0.612 increase, and a unit increase in the perception of a price increase is associated with a 0.270 increase.

The findings in

Table 6 reveal the positive statistical significance of the perception of environmental sustainability, the perception of economic considerations, the perception of Indigenous rights, and education (especially with a college, CEGEP, or other non-university certificate or diploma, and high school diploma or equivalent) in influencing the behavior of choosing Canadian farm-raised salmon over foreign wild salmon. Particularly, a unit increase in the perception of environmental sustainability is associated with a 0.710 increment in such purchase behavior. Similarly, a unit increase in the perception of economic considerations corresponds to a 0.769 increase, and a unit increase in the perception of Indigenous rights is linked to a 0.227 increase in such purchase behavior.

The findings in

Table 6 indicate the negative statistical significance of the perception of environmental sustainability, flexitarian dietary preference, as well as education (particularly those with a high school diploma or equivalent), on the behavior of purchasing more Canadian farm-raised salmon to support Indigenous communities. Conversely, the perception of Indigenous rights demonstrates significantly positive influences on the behavior of buying more Canadian farm-raised salmon to support Indigenous communities. Notably, a unit increase in the perception of environmental sustainability corresponds to a 0.357 decrease in such purchase behavior, while a unit increase in the perception of a price increase is linked to a 6.487 increase.

The findings in

Table 6 reveal the negative statistical significance of the perception of economic considerations and age (especially within the range of the 1946-1964 bracket) on the behavior of purchasing more Canadian farm-raised salmon from farms that support Indigenous communities. Conversely, the perception of Indigenous rights demonstrates significantly positive influences on the behavior of buying more Canadian farm-raised salmon from farms that support Indigenous communities. Moreover, a unit increase in the perception of economic considerations corresponds to a 0.551 decrease in such purchase behavior, while a unit increase in the perception of a price increase is associated with a 7.915 increase.

Finally, the findings presented in

Table 6 elucidate the negative statistical significance of marital status (especially married or common-law), education (excluding the categorization ‘some high school’), the perceived importance of price, and the perception of a price increase on the behavior of willingness to pay more for salmon with a sustainable certification label. In contrast, the perception of environmental sustainability, Indigenous rights, pescatarian dietary preference, gender (especially female), income (those exceeding

$100,000), residential zones (particularly those in urban cores), and the perceived importance of origin demonstrate significantly positive influences on the behavior of paying more for salmon with a sustainable certification label. Additionally, a unit increase in the perception of environmental sustainability corresponds to a 0.471 increase in such purchase behavior, a unit increase in the perception of Indigenous rights is linked to a 0.889 increase, while a unit increase in the perception of a price increase is associated with a 0.285 decrease.

4. Discussion

This study contributes to the assessment of four perceptions: environmental sustainability, economic considerations, Indigenous rights, and price increase, and investigates their impacts on seven purchasing behaviors. Regarding environmental sustainability, statistically significant negative effects are evident in dietary preferences, gender, age, education, and geographic location, in contrast to positive correlations related to household size, residential zones, and the perceived importance of price and origin. Economic considerations mirror this pattern, exhibiting the same negative impact factors as environmental sustainability, indicating positive associations with household size, geographic location, residential zones, and the perceived importance of price and origin. In the context of Indigenous rights, analogous negative impact factors emerge as in environmental sustainability, while positive influences arise from determinants such as gender, geographic location, residential zones, and the perceived importance of price and origin. Concerning the perception of a price increase, negative effects associated with dietary preferences emerge, whereas positive correlations are established for respondents’ purchase history and the perceived importance of price and origin.

In the domain of consumer purchasing behaviors, particularly in the choice between fresh and frozen salmon (Q5), this study reveals negative effects associated with specific dietary preferences and female gender. Conversely, positive determinants include economic considerations, a price increase, Quebec residence, urban dwelling, purchase history, and the perceived importance of origin. Concerning the choice of Canadian-sourced salmon (Q7), negative impacts are linked to certain dietary preferences and income, while positive factors encompass economic considerations, a price increase, age, purchase history, and the perceived importance of origin. Negative influences on the selection of Canadian farm-raised salmon over those from another country (Q8) involve specific dietary preferences and urban residence, while positive impacts include environmental sustainability, economic considerations, a price increase, age, higher income, and the perceived importance of origin. Notably, the deduction drawn from these two purchasing behaviors (Q7 and Q8) implies that Canadians demonstrate a preference for Canadian-sourced farmed salmon compared to products from other countries, as evidenced by the observed statistical significance of the perceived importance of origin. Opting for Canadian farm-raised over foreign wild salmon (Q9) is positively influenced by environmental sustainability, economic considerations, Indigenous rights, and education. Negative effects on supporting Indigenous communities (Q11) stem from considerations of environmental sustainability, lower education, and specific dietary preferences, while positive factors include perceptions of Indigenous rights. Purchasing from farms supporting Indigenous communities (Q17) incurs negative effects correlated with economic considerations and age, while positive factors are associated with perceptions of Indigenous rights. Lastly, the willingness to pay more for sustainably certified salmon (Q21) is negatively influenced by marital status, education, perceived importance of price, and a price increase. Positive inclinations towards such behavior are associated with environmental sustainability, perceptions of Indigenous rights, specific dietary preferences, female gender, higher income, urban living, and the perceived importance of origin. The quantitative impact of perceptions of environmental sustainability, economic considerations, Indigenous rights, and a price increase on consumer purchasing behaviors has been systematically calculated.

This study is not exempt from certain limitations. Firstly, the recruitment of participants through convenience sampling may introduce selection bias, as individuals who perceive an increase in the price of salmon might be more inclined to participate with the anticipation of potential policies addressing the rising prices. Secondly, the formulation of survey questions carries the potential for subconscious bias. For instance, the wording of Question 34, "The price of salmon and other fish products has increased" may yield different responses compared to a counterpart statement such as "The price of salmon and other fish products has NOT increased". The subtle alteration in phrasing could influence participant responses and introduce unintended biases into the data collection process.

5. Conclusions

Based on the results of this study, several theoretical, managerial, and policy implications can be drawn, highlighting the significance of understanding perceptions related to environmental sustainability, economic considerations, Indigenous rights, and price increase in influencing consumer purchasing behaviors.

From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to the existing body of knowledge by shedding light on the intricate interplay between various perceptions and their impact on consumer decision-making processes. The findings underscore the importance of considering multiple factors, including individual preferences, socio-economic status, and cultural values, in understanding consumer behavior within the context of sustainability and ethical considerations. Moreover, the identification of both positive and negative associations between perceptions and purchasing behaviors provides valuable insights into the complexity of consumer decision-making, emphasizing the need for a nuanced understanding of these dynamics in theoretical frameworks.

On a managerial level, the findings offer practical implications for businesses and marketers seeking to align their strategies with consumer preferences and values. By recognizing the significance of environmental sustainability, economic considerations, Indigenous rights, price sensitivity, coupled with consumer motivation of origin in shaping purchasing behaviors, businesses can tailor their product offerings, marketing messages, and pricing strategies to resonate with consumers' values and priorities. Illustratively, the perceptive recognition of Canadians' preference for domestically sourced salmon and their inclination to choose Canadian farm-raised salmon over those from other countries broadens the scope of business opportunities within the realm of marketing. Additionally, understanding the differential impact of these perceptions across demographic segments enables firms to develop targeted marketing campaigns and product innovations that appeal to specific consumer segments, thereby enhancing competitiveness and market positioning.

From a policy standpoint, the results of this study underscore the importance of implementing regulatory frameworks and initiatives that promote sustainability, protect Indigenous rights, and address socio-economic disparities. Policies aimed at raising consumer awareness, promoting sustainable consumption practices, and ensuring transparency in supply chains can play a crucial role in influencing consumer behaviors and fostering a culture of responsible consumption. Furthermore, efforts to support Indigenous communities and promote fair trade practices can contribute to social equity and environmental stewardship, aligning with broader policy objectives related to sustainable development and social justice.

In conclusion, this study offers valuable insights into the complex interplay between perceptions and purchasing behaviors, highlighting the theoretical, managerial, and policy implications for understanding and influencing consumer decision-making processes. By addressing the underlying factors driving consumer preferences and values, businesses, policymakers, and stakeholders can work towards fostering more sustainable and ethical consumption patterns, thereby contributing to broader societal and environmental goals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Appendix S1: Questionnaire – Consumer Trust & Salmon in Canada.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the Agri-Food Analytics Lab for their generous funding and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alfnes, F.; Guttormsen, A.G.; Steine, G.; Kolstad, K. Consumers' Willingness to Pay for the Color of Salmon: A Choice Experiment with Real Economic Incentives. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 88, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BC Salmon Farmers Associations. BC Salmon Aquaculture Transition: Then & Now. BC Salmon Farmers. 2023. Available online: https://bcsalmonfarmers.ca/aquaculture/#reports.

- Budhathoki, M.; Zølner, A.; Nielsen, T.; Reinbach, H.C. The role of production method information on sensory perception of smoked salmon—A mixed-method study from Denmark. Food Qual. Preference 2021, 94, 104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business in Vancouver. Fish farmers launch legal challenge of fish farm closures. 2023. Available online: https://www.biv.com/news/resources-agriculture/fish-farmers-launch-legal-challenge-fish-farm-closures-8270979.

- Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance. 2023. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56c20b66e707eb013dc65bab/t/63fcd0b589b99b4dbc181e6f/1677512885644/Q1+2023_CAIA+Farm-Raised+Seafood+Report.pdf.

- Carothers, C.; Black, J.; Langdon, S.J.; Donkersloot, R.; Ringer, D.; Coleman, J.; Gavenus, E.R.; Justin, W.; Williams, M.; Christiansen, F.; et al. Indigenous peoples and salmon stewardship: A critical relationship. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaedeke, R.M. Consumer Consumption and Perceptions of Salmon. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2001, 7, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottesen, G.G. Do upstream actors in the food chain know end-users' quality perceptions? Findings from the Norwegian salmon farming industry. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2006, 11, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Number of commercial fishing licences issued by Pacific Region. 2024. Available online: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/stats/commercial/licences-permis/pacific-pacifique/pac22-eng.htm.

- Horn, J.L. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 1965, 30, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.; McDaniels, T.; Hinch, S. Indigenous culture and adaptation to climate change: Sockeye salmon and the St’át’imc people. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2010, 15, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Colmenero, M.; Juanes, F.; Dopico, E.; Martinez, J.L.; Garcia-Vazquez, E. Economy matters: A study of mislabeling in salmon products from two regions, Alaska and Canada (Northwest of America) and Asturias (Northwest of Spain). Fish. Res. 2017, 195, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrland, Ö.; Emaus, P.; Roheim, C.; Kinnucan, H. Promotion and consumer choices: Analysis of advertising effects on the Japanese market for Norwegian salmon. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2004, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickoloff, M.; Maynard, L.J.; Saghaian, S.H.; Reed, M.R. The effect of conflicting health information on frozen salmon consumption in Alberta, Canada. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2008, 39, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noakes, D.J.; Beamish, R.J.; Gregory, R. British Columbia's commercial salmon industry. North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission, Document 2002, 642, 13.

- Nourish food marketing. Canadians are eating more salmon than ever, but will it be home-grown from Canada? 2022. Available online: https://www.nourish.marketing/news/canadians-are-eating-more-salmon-than-ever-but-will-it-be-home-grown-from-canada.

- Onozaka, Y.; Hansen, H.; Sørvig, A. Consumer Product Perceptions and Salmon Consumption Frequency: The Role of Heterogeneity Based on Food Lifestyle Segments. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2014, 29, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onozaka, Y.; Honkanen, P.; Altintzoglou, T. Sustainability, perceived quality and country of origin of farmed salmon: Impact on consumer choices in the USA, France and Japan. Food Policy 2023, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmond, A.T.Y.; Charlebois, S.; Colombo, S.M. Exploratory analysis on Canadian consumer perceptions, habits, and opinions on salmon consumption and production in Canada. Aquac. Int. 2022, 31, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Brown, J.L. Consumer Opinions about Genetically Engineered Salmon and Information Effect on Opinions. Sci. Commun. 2006, 28, 243–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samejima, F. Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometr. Monogr. Suppl. 1969, 34 Pt 2, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J. Ordinal response mixed models: A case study; Montana State University: Montana, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, J.R.; Atlas, W.I.; Ban, N.C.; Wilson, K.; Wilson, J.; Housty, W.G.; Moore, J.W. Understanding barriers, access, and management of marine mixed-stock fisheries in an era of reconciliation: Indigenous-led salmon monitoring in British Columbia. FACETS 2021, 6, 592–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Oishi, T.; Kurokura, H.; Yagi, N. Which Aspects of Food Value Promote Consumer Purchase Intent after a Disaster? A Case Study of Salmon Products in Disaster-Affected Areas of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Foods 2019, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Handbook of modern item response theory, van der Linden, W.J., Hambleton, R.K., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- Ween, G.B.; Colombi, B.J. Two Rivers: The Politics of Wild Salmon, Indigenous Rights and Natural Resource Management. Sustainability 2013, 5, 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, D.; Palmieri, M.G. Consumer behaviour and environmental preferences: A case study of Scottish salmon aquaculture. Aquac. Res. 2011, 42, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, H.H.; Lu, Y. Consumer Purchase Intentions for Sustainable Wild Salmon in the Chinese Market and Implications for Agribusiness Decisions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, H.H.; Shogren, J.F. Fishing or Aquaculture? Chinese Consumers’ Stated Preference for the Growing Environment of Salmon through a Choice Experiment and the Consequentiality Effect. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2021, 36, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Nayga, R.M.; Yang, W.; Tokunaga, K. Do U.S. consumers value genetically modified farmed salmon? Food Qual. Preference 2023, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

PCA eigenvalues for actual data (Q19-Q20 and Q22-Q27) and simulated data for parallel analysis.

Figure 1.

PCA eigenvalues for actual data (Q19-Q20 and Q22-Q27) and simulated data for parallel analysis.

Figure 2.

This is a PCA eigenvalues for actual data (Q28-Q33 and Q35) and simulated data for parallel analysis.

Figure 2.

This is a PCA eigenvalues for actual data (Q28-Q33 and Q35) and simulated data for parallel analysis.

Figure 3.

PCA eigenvalues for actual data (Q11-Q12, Q17, Q24, and Q29) and simulated data for parallel analysis.

Figure 3.

PCA eigenvalues for actual data (Q11-Q12, Q17, Q24, and Q29) and simulated data for parallel analysis.

Figure 4.

Trace plots of sustainability items (Q19, Q20, Q22, Q23, Q24, Q25, Q26, and Q27). represents the unidimensional latent trait (sustainability) and represent the fitted probability of responding to each of the question items Q19, Q20, Q22, Q23, Q24, Q25, Q26, and Q27 at the sustainability level .

Figure 4.

Trace plots of sustainability items (Q19, Q20, Q22, Q23, Q24, Q25, Q26, and Q27). represents the unidimensional latent trait (sustainability) and represent the fitted probability of responding to each of the question items Q19, Q20, Q22, Q23, Q24, Q25, Q26, and Q27 at the sustainability level .

Figure 5.

Trace plots of economic consideration items (Q28, Q29, Q30, Q31, Q32, Q33, and Q35). represents the unidimensional latent trait (economic consideration) and represent the fitted probability of responding to each of the question items Q28, Q29, Q30, Q31, Q32, Q33, and Q35 at the economic consideration level .

Figure 5.

Trace plots of economic consideration items (Q28, Q29, Q30, Q31, Q32, Q33, and Q35). represents the unidimensional latent trait (economic consideration) and represent the fitted probability of responding to each of the question items Q28, Q29, Q30, Q31, Q32, Q33, and Q35 at the economic consideration level .

Figure 6.

Trace plots of economic consideration items (Q11, Q12, Q17, Q24, and Q29). represents the unidimensional latent trait (supporting Indigenous communities) and represent the fitted probability of responding to each of the question items Q11, Q12, Q17, Q24, and Q29 at the level of supporting Indigenous rights.

Figure 6.

Trace plots of economic consideration items (Q11, Q12, Q17, Q24, and Q29). represents the unidimensional latent trait (supporting Indigenous communities) and represent the fitted probability of responding to each of the question items Q11, Q12, Q17, Q24, and Q29 at the level of supporting Indigenous rights.

Table 1.

Frequencies (percentage) for socio-demographics.

Table 1.

Frequencies (percentage) for socio-demographics.

| Variables |

Levels |

Frequency |

| Dietary Preferences (D1) |

Consumer with no dietary preferences |

867 (80.43%) |

| Consumer with specific religious or cultural dietary preferences |

22 (2.04%) |

| Flexitarian (vegetarian who occasionally eats meat and fish) |

54 (5.01%) |

| Lacto-ovo vegetarian (diet free of animal flesh but eats eggs and milk products) |

14 (1.30%) |

| Pescatarian (diet free of land animal flesh but eats eggs, fish, and milk products) |

25 (2.32%) |

| Vegan (diet free of all animal-based products) |

17 (1.58%) |

| Vegetarian (diet free of meat, fish, and fowl flesh) |

16 (1.48%) |

| Other† |

63 (5.84%) |

| Gender (D2) |

Male |

515 (47.77%) |

| Female |

538 (49.91%) |

| Non-binary / third gender |

18 (1.67%) |

| Prefer not to say |

7 (0.65%) |

| Marital Status (D3) |

Divorced, separated, or widowed |

127 (11.78%) |

| Married or common-law |

730 (67.72%) |

| Single |

221 (20.50%) |

| Age (D4) |

Before 1946 |

38 (3.53%) |

| From 1946 to 1964 |

347 (32.19%) |

| From 1965 to 1979 |

206 (19.11%) |

| From 1980 to 1994 |

366 (33.95%) |

| After 1994 |

121 (11.22%) |

| Household Size (D5) |

None |

727 (67.44%) |

| One |

171 (15.86%) |

| Two |

137 (12.71%) |

| Three or more |

43 (3.99%) |

| Education (D6) |

Advanced University Degree (Graduate) |

197 (18.27%) |

| College, CEGEP or Other Non-University Certificate or Diploma |

276 (25.60%) |

| High School Diploma or Equivalent |

129 (11.97%) |

| Registered Apprenticeship or Other Trades Certificate or Diploma |

82 (7.61%) |

| Some High School |

19 (1.76%) |

| University Degree, Certificate or Diploma |

375 (34.79%) |

| Geographic Location (D7) |

Atlantic Canada |

77 (7.14%) |

| British Columbia |

156 (14.47%) |

| Northern Region |

3 (0.28%) |

| Ontario |

396 (36.73%) |

| Prairies |

186 (17.25%) |

| Quebec |

260 (24.12%) |

| Income (D8) |

Less than $35,000 |

103 (9.55%) |

| Between $35,000 and $49,99 |

97 (9.00%) |

| Between $50,000 and $74,999 |

161 (14.94%) |

| Between $75,000 and $99,999 |

185 (17.16%) |

| Between $100,000 and $149,999 |

297 (27.55%) |

|

$150,000 + |

235 (21.80%) |

| Residential Zone (D9) |

Suburban |

392 (36.36%) |

| Small town, community, or rural |

283 (26.25%) |

| Urban Core |

403 (37.38%) |

| Purchase History (Q1) |

No |

169 (15.68%) |

| Yes |

909 (84.32%) |

Table 2.

Frequencies (percentage) for variables from Question 2 to Question 35.

Table 2.

Frequencies (percentage) for variables from Question 2 to Question 35.

| Variables |

Names |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

| Q2 |

I enjoy eating salmon |

118 (10.95%) |

66 (6.12%) |

141 (13.08%) |

353 (32.75%) |

400 (37.11%) |

| Q3 |

I enjoy eating salmon on special occasions |

113 (10.48%) |

94 (8.72%) |

275 (25.51%) |

370 (34.32%) |

226 (20.96%) |

| Q4 |

I enjoy eating salmon regularly |

143 (13.27%) |

191 (17.72%) |

228 (21.15%) |

353 (32.75%) |

163 (15.12%) |

| Q5 |

I prefer purchasing fresh (never been frozen) salmon over frozen salmon |

67 (6.22%) |

108 (10.02%) |

357 (33.12%) |

302 (28.01%) |

244 (22.63%) |

| Q6 |

I enjoy eating salmon because it is a healthy choice |

71 (6.59%) |

55 (5.10%) |

187 (17.35%) |

513 (47.59%) |

252 (23.38%) |

| Q7 |

I want to buy salmon that comes from Canada |

48 (4.45%) |

15 (1.39%) |

169 (15.68%) |

416 (38.59%) |

430 (39.89%) |

| Q8 |

If I had the choice between farm-raised salmon from Canada or another country, I would buy Canadian salmon |

37 (3.43%) |

33 (3.06%) |

173 (16.05%) |

411 (38.13%) |

424 (39.33%) |

| Q9 |

If I had a choice between buying wild salmon from a foreign country or farm-raised salmon from Canada, I would buy the Canadian salmon |

101 (9.37%) |

147 (13.64%) |

252 (23.38%) |

303 (28.11%) |

275 (25.51%) |

| Q10 |

Most of the fresh (never been frozen) salmon in stores is from salmon farms |

16 (1.48%) |

33 (3.06%) |

539 (50.00%) |

397 (36.83%) |

93 (8.63%) |

| Q11 |

I would purchase more Canadian farm-raised salmon if this supported Indigenous communities in Canada |

116 (10.76%) |

94 (8.72%) |

416 (38.59%) |

291 (26.99%) |

161 (14.94%) |

| Q12 |

100% of current farmed salmon in BC is supported and overseen by local First Nations. This makes me more likely to buy BC farmed salmon |

94 (8.72%) |

102 (9.46%) |

420 (38.96%) |

318 (29.50%) |

144 (13.36%) |

| Q13 |

Price is an important factor when purchasing salmon products |

25 (2.32%) |

60 (5.57%) |

193 (17.90%) |

470 (43.60%) |

330 (30.61%) |

| Q14 |

When I buy salmon, it’s important for me to know where it comes from |

23 (2.13%) |

52 (4.82%) |

195 (18.09%) |

496 (46.01%) |

312 (28.94%) |

| Q15 |

I prefer Atlantic salmon over Pacific salmon |

64 (5.94%) |

129 (11.97%) |

663 (61.50%) |

138 (12.80%) |

84 (7.79%) |

| Q16 |

I prefer wild Atlantic salmon to farm-raised Atlantic salmon |

17 (1.58%) |

35 (3.25%) |

508 (47.12%) |

323 (29.96%) |

195 (18.09%) |

| Q17 |

I would purchase more Canadian farm-raised salmon from farms that have local Indigenous community support and oversight |

111 (10.30%) |

97 (9.00%) |

447 (41.47%) |

308 (28.57%) |

115 (10.67%) |

| Q18 |

I enjoy eating salmon because it is a more sustainable protein than other options |

76 (7.05%) |

102 (9.46%) |

516 (47.87%) |

293 (27.18%) |

91 (8.44%) |

| Q19 |

Marine resource management and sustainability practices are very important for Canada’s salmon farming sector |

19 (1.76%) |

19 (1.76%) |

216 (20.04%) |

445 (41.28%) |

379 (35.16%) |

| Q20 |

Canadian salmon farms are improving their environmental sustainability |

43 (3.99%) |

62 (5.75%) |

642 (59.55%) |

285 (26.44%) |

46 (4.27%) |

| Q21 |

I would pay more for salmon with a sustainable certification label |

80 (7.42%) |

181 (16.79%) |

385 (35.71%) |

337 (31.26%) |

95 (8.81%) |

| Q22 |

I believe sustainable-certified salmon farming is the future of salmon production for Canada |

63 (5.84%) |

65 (6.03%) |

431 (39.98%) |

402 (37.29%) |

117 (10.85%) |

| Q23 |

Canadian farm-raised salmon has a lower carbon footprint than imported salmon |

36 (3.34%) |

34 (3.15%) |

543 (50.37%) |

354 (32.84%) |

111 (10.30%) |

| Q24 |

I believe that Indigenous community oversight over salmon farms will help improve their sustainability |

74 (6.86%) |

111 (10.30%) |

432 (40.07%) |

334 (30.98%) |

127 (11.78%) |

| Q25 |

I believe salmon farms support wild salmon stock recovery because they reduce pressure on the wild stocks |

60 (5.57%) |

85 (7.88%) |

385 (35.71%) |

442 (41.00%) |

106 (9.83%) |

| Q26 |

I believe that the benefits of salmon farms are greater than any risks |

91 (8.44%) |

133 (12.34%) |

516 (47.87%) |

283 (26.25%) |

55 (5.10%) |

| Q27 |

I believe that salmon can be responsibly farmed in the ocean |

79 (7.33%) |

109 (10.11%) |

361 (33.49%) |

445 (41.28%) |

84 (7.79%) |

| Q28 |

I think the salmon farming sector is heavily regulated |

45 (4.17%) |

150 (13.91%) |

626 (58.07%) |

221 (20.50%) |

36 (3.34%) |

| Q29 |

I like the idea of supporting coastal and Indigenous communities by purchasing Canadian farm-raised salmon |

69 (6.40%) |

60 (5.57%) |

304 (28.20%) |

470 (43.60%) |

175 (16.23%) |

| Q30 |

I have confidence in the quality and welfare of salmon from Canada because of the oversight of the regulatory framework |

54 (5.01%) |

111 (10.30%) |

418 (38.78%) |

411 (38.13%) |

84 (7.79%) |

| Q31 |

Supporting Canada’s youngest food production workforce in salmon farming is important to me |

48 (4.45%) |

80 (7.42%) |

477 (44.25%) |

379 (35.16%) |

94 (8.72%) |

| Q32 |

I think Canada should produce more salmon to benefit Canadian consumers |

45 (4.17%) |

49 (4.55%) |

321 (29.78%) |

489 (45.36%) |

174 (16.14%) |

| Q33 |

Canada exports most of its salmon |

13 (1.21%) |

44 (4.08%) |

834 (77.37%) |

151 (14.01%) |

36 (3.34%) |

| Q34 |

The price of salmon and other fish products has increased |

5 (0.46%) |

9 (0.83%) |

137 (12.71%) |

523 (48.52%) |

404 (37.48%) |

| Q35 |

I believe that reducing the BC farm-raised salmon supply in the North American market will negatively impact the retail price |

16 (1.48%) |

54 (5.01%) |

450 (41.74%) |

413 (38.31%) |

145 (13.45%) |

Table 3.

Cronbach Alpha Reliability Test.

Table 3.

Cronbach Alpha Reliability Test.

| Sub-domain |

Variables |

Cronbach Alpha |

95% Confidence boundaries |

| Environmental sustainability |

Q19-Q20, Q22-Q27 |

0.850 |

Feldt |

(0.836, 0.863) |

| Duhachek |

(0.836, 0.863) |

| Economic considerations |

Q28-Q33, Q35 |

0.795 |

Feldt |

(0.776, 0.813) |

| Duhachek |

(0.778, 0.813) |

| Indigenous Rights |

Q11-Q12, Q17, Q24, Q29 |

0.923 |

Feldt |

(0.916, 0.930) |

| Duhachek |

(0.916, 0.930) |

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for the MAP estimated unidimensional latent traits.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for the MAP estimated unidimensional latent traits.

| Sub-domain |

Minimal |

1st Quartile |

Median |

Mean |

3rd Quartile |

Maximal |

Standard Deviation |

| Environmental sustainability |

-3.11 |

-0.52 |

0.05 |

-0.00 |

0.56 |

2.70 |

0.94 |

| Economic considerations |

-3.21 |

-0.54 |

0.02 |

-0.00 |

0.57 |

2.71 |

0.92 |

| Indigenous rights |

-2.27 |

-0.52 |

-0.09 |

-0.00 |

0.66 |

2.01 |

0.96 |

Table 5.

Results for four perceptions.

Table 5.

Results for four perceptions.

| |

Variables |

Levels |

Perception Outcomes |

| |

|

|

Environmental Sustainability |

Economic Considerations |

Indigenous Rights |

Price Increase |

| Method |

|

|

OLS |

OLS |

OLS |

Logistic |

| Socio-demographic |

D1 (Dietary Preferences) |

Consumer with no dietary preferences Consumer with no dietary preferences |

Reference |

| Consumer with specific religious or cultural dietary preferences |

-0.163 |

-0.103 |

-0.021 |

-0.648 |

| (0.385) |

(0.564) |

(0.913) |

(0.334) |

| Flexitarian (vegetarian who occasionally eats meat and fish) |

-0.303* |

-0.226* |

-0.088 |

-0.563 |

| (0.012) |

(0.050) |

(0.487) |

(0.201) |

| Lacto-ovo vegetarian (diet free of animal flesh but eats eggs and milk products) |

-0.051 |

-0.009 |

0.112 |

-2.268** |

| (0.828) |

(0.968) |

(0.650) |

(0.001) |

| Pescatarian (diet free of land animal flesh but eats eggs, fish, and milk products) |

0.035 |

0.054 |

0.264 |

-1.049 |

| (0.841) |

(0.748) |

(0.151) |

(0.067) |

| Vegan (diet free of all animal-based products) |

-1.357*** |

-1.262*** |

-0.884*** |

-1.162 |

| (0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.052) |

| Vegetarian (diet free of meat, fish, and fowl flesh) |

-0.314 |

-0.546** |

-0.080 |

-1.219* |

| (0.151) |

(0.009) |

(0.726) |

(0.047) |

| Other |

-0.349** |

-0.354*** |

-0.238* |

-0.255 |

| (0.002) |

(0.001) |

(0.044) |

(0.590) |

| D2 (Gender) |

Male |

Reference |

| Female |

-0.052 |

-0.058 |

0.172** |

0.329 |

| (0.334) |

(0.266) |

(0.003) |

(0.124) |

| Non-binary / third gender |

-0.114 |

-0.550** |

0.266 |

-0.363 |

| (0.591) |

(0.007) |

(0.234) |

(0.625) |

| Prefer not to say |

-0.964** |

-0.907** |

-0.725* |

-0.775 |

| (0.003) |

(0.004) |

(0.034) |

(0.520) |

| D3 (Marital Status) |

Divorced, separated, or widowed |

Reference |

| Married or common-law |

0.091 |

0.098 |

0.112 |

-0.114 |

| (0.312) |

(0.250) |

(0.235) |

(0.762) |

| Single |

-0.004 |

-0.078 |

0.113 |

-0.260 |

| (0.973) |

(0.434) |

(0.303) |

(0.539) |

| D4 (Age) |

After 1994 |

Reference |

| Before 1946 |

-0.469** |

-0.103 |

-0.418* |

-0.060 |

| (0.006) |

(0.524) |

(0.019) |

(0.944) |

| From 1946 to 1964 |

-0.311** |

-0.053 |

-0.382*** |

-0.387 |

| (0.002) |

(0.585) |

(0.000) |

(0.342) |

| From 1965 to 1979 |

-0.358*** |

-0.207* |

-0.242* |

-0.460 |

| (0.001) |

(0.037) |

(0.027) |

(0.258) |

| From 1980 to 1994 |

-0.203* |

-0.153 |

-0.121 |

-0.384 |

| (0.032) |

(0.091) |

(0.224) |

(0.301) |

| D5 (Household Size) |

None |

Reference |

| One |

0.186* |

0.208** |

0.083 |

-0.461 |

| (0.018) |

(0.005) |

(0.313) |

(0.127) |

| Two |

0.127 |

0.206* |

-0.067 |

-0.046 |

| (0.138) |

(0.012) |

(0.350) |

(0.891) |

| Three or more |

-0.205 |

-0.084 |

0.084 |

-0.835 |

| (0.140) |

(0.527) |

(0.645) |

(0.064) |

| D6 (Education) |

Advanced University Degree (Graduate) |

Reference |

| College, CEGEP or Other Non-University Certificate or Diploma |

-0.058 |

-0.062 |

-0.152 |

0.577 |

| (0.491) |

(0.444) |

(0.088) |

(0.084) |

| High School Diploma or Equivalent |

-0.038 |

-0.044 |

-0.120 |

0.450 |

| (0.705) |

(0.645) |

(0.257) |

(0.247) |

| Registered Apprenticeship or Other Trades Certificate or Diploma |

-0.450*** |

-0.349** |

-0.395** |

0.363 |

| (0.000) |

(0.002) |

(0.001) |

(0.441) |

| Some High School |

0.085 |

-0.163 |

-0.218 |

0.459 |

| (0.690) |

(0.423) |

(0.331) |

(0.537) |

| University Degree, Certificate or Diploma |

0.137 |

0.074 |

0.023 |

0.198 |

| (0.072) |

(0.309) |

(0.773) |

(0.483) |

| D7 (Geographic Location) |

Atlantic Canada |

Reference |

| British Columbia |

-0.438*** |

-0.370** |

-0.261* |

-0.747 |

| (0.000) |

(0.001) |

(0.038) |

(0.186) |

| Northern Region |

-0.450 |

0.150 |

0.253 |

-1.241 |

| (0.374) |

(0.755) |

(0.633) |

(0.406) |

| Ontario |

-0.043 |

0.004 |

0.174 |

-0.615 |

| (0.689) |

(0.972) |

(0.120) |

(0.236) |

| Prairies |

-0.053 |

-0.105 |

0.068 |

-0.786 |

| (0.646) |

(0.342) |

(0.578) |

(0.147) |

| Quebec |

0.216 |

0.327** |

0.355** |

-0.538 |

| (0.053) |

(0.002) |

(0.002) |

(0.318) |

| D8 (Income) |

Less than $35,000 |

Reference |

| Between $35,000 and $49,999 |

-0.076 |

-0.053 |

0.062 |

0.099 |

| (0.540) |

(0.654) |

(0.630) |

(0.829) |

| Between $50,000 and $74,999 |

0.057 |

0.020 |

0.066 |

0.811 |

| (0.609) |

(0.850) |

(0.571) |

(0.078) |

| Between $75,000 and $99,999 |

-0.133 |

-0.161 |

-0.133 |

0.054 |

| (0.240) |

(0.136) |

(0.260) |

(0.901) |

| Between $100,000 and $149,999 |

-0.108 |

-0.087 |

-0.115 |

0.161 |

| (0.328) |

(0.405) |

(0.318) |

(0.702) |

|

$150,000 + |

-0.139 |

-0.161 |

-0.220 |

0.199 |

| (0.238) |

(0.151) |

(0.074) |

(0.656) |

| D9 (Residential Zone) |

Suburban |

Reference |

| Small town, community, or rural |

0.143* |

0.105 |

0.068 |

0.128 |

| (0.036) |

(0.104) |

(0.340) |

(0.643) |

| Urban Core |

0.114 |

0.129* |

0.205** |

0.042 |

| (0.068) |

(0.031) |

(0.002) |

(0.861) |

| Q1 (Purchase History) |

No |

Reference |

| Yes |

0.099 |

0.181* |

0.074 |

1.229*** |

| (0.207) |

(0.016) |

(0.366) |

(0.000) |

| |

(Perceived importance of price) |

No |

Reference |

| Yes |

0.433*** |

0.478*** |

0.350*** |

1.050*** |

| (0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

| |

(Perceived importance of origin) |

No |

Reference |

| Yes |

0.151* |

0.194** |

0.339*** |

1.141*** |

| (0.019) |

(0.002) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

| |

Adjusted R2

|

|

0.1932 |

0.2325 |

0.1595 |

- |

Table 6.

Results for purchasing behaviors by using cumulative link model.

Table 6.

Results for purchasing behaviors by using cumulative link model.

| |

Variables |

Levels |

Purchasing Behaviors |

| |

|

|

Q5 (Selection of fresh (never been frozen) salmon over frozen salmon) |

Q7 (Purchase Canadian-sourced salmon) |

Q8 (Selection of Canadian farm-raised salmon over salmon from another country) |

Q9 (Selection of Canadian farm-raised salmon over foreign wild salmon) |

Q11 (Purchase more Canadian farm-raised salmon to support Indigenous communities) |

Q17 (Purchase more Canadian farm-raised salmon from farms that support Indigenous communities) |

Q21 (Willingness to pay more for salmon with a sustainable certification label) |

| |

Environmental Sustainability |

-0.211 |

-0.216 |

0.432*** |

0.710*** |

-0.357* |

-0.114 |

0.471*** |

| (0.050) |

(0.066) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.028) |

(0.524) |

(0.000) |

| |

Economic Considerations |

0.426*** |

0.759*** |

0.612*** |

0.769*** |

-0.229 |

-0.551** |

-0.015 |

| (0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.168) |

(0.003) |

(0.901) |

| |

Indigenous Rights |

0.062 |

0.157 |

0.163 |

0.227* |

6.487*** |

7.915*** |

0.889*** |

| (0.462) |

(0.090) |

(0.074) |

(0.011) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

| Socio-demographic |

D1 (Dietary Preferences) |

Consumer with no dietary preferences |

Reference |

| Consumer with specific religious or cultural dietary preferences |

0.317 |

0.297 |

-0.212 |

-0.659 |

-0.453 |

0.471 |

0.020 |

| (0.452) |

(0.503) |

(0.595) |

(0.105) |

(0.476) |

(0.548) |

(0.962) |

| Flexitarian (vegetarian who occasionally eats meat and fish) |

0.222 |

-0.007 |

-0.614* |

-0.041 |

-0.757* |

-0.007 |

0.295 |

| (0.382) |

(0.981) |

(0.029) |

(0.879) |

(0.036) |

(0.987) |

(0.281) |

| Lacto-ovo vegetarian (diet free of animal flesh but eats eggs and milk products) |

0.200 |

-1.341* |

-0.061 |

0.061 |

-0.368 |

-0.043 |

0.144 |

| (0.688) |

(0.012) |

(0.905) |

(0.899) |

(0.642) |

(0.965) |

(0.763) |

| Pescatarian (diet free of land animal flesh but eats eggs, fish, and milk products) |

-1.071** |

0.037 |

0.797 |

-0.255 |

0.506 |

0.592 |

1.113** |

| (0.006) |

(0.931) |

(0.062) |

(0.496) |

(0.353) |

(0.365) |

(0.005) |

| Vegan (diet free of all animal-based products) |

-0.776 |

-1.089* |

0.035 |

0.635 |

1.358 |

-1.653 |

-0.107 |

| (0.122) |

(0.036) |

(0.943) |

(0.215) |

(0.078) |

(0.169) |

(0.840) |

| Vegetarian (diet free of meat, fish, and fowl flesh) |

-1.236* |

-1.559** |

-0.920* |

-0.110 |

-0.345 |

1.093 |

0.911 |

| (0.012) |

(0.002) |

(0.049) |

(0.812) |

(0.603) |

(0.133) |

(0.052) |

| Other |

-0.085 |

0.015 |

-0.628* |

-0.383 |

-0.116 |

0.237 |

0.197 |

| (0.733) |

(0.955) |

(0.020) |

(0.127) |

(0.733) |

(0.542) |

(0.439) |

| D2 (Gender) |

Male |

Reference |

| Female |

-0.441*** |

0.035 |

-0.079 |

0.056 |

-0.105 |

-0.071 |

0.373** |

| (0.000) |

(0.786) |

(0.718) |

(0.648) |

(0.544) |

(0.719) |

(0.002) |

| Non-binary / third gender |

-0.415 |

-0.344 |

-0.449 |

-0.232 |

-1.125 |

-0.588 |

0.095 |

| (0.354) |

(0.492) |

(0.345) |

(0.619) |

(0.079) |

(0.432) |

(0.838) |

| Prefer not to say |

0.125 |

0.192 |

0.218 |

0.991 |

-0.890 |

1.562 |

1.215 |

| (0.850) |

(0.795) |

(0.769) |

(0.165) |

(0.326) |

(0.148) |

(0.112) |

| D3 (Marital Status) |

Divorced, separated, or widowed |

Reference |

| Married or common-law |

-0.366 |

-0.213 |

-0.093 |

-0.007 |

-0.415 |

0.238 |

-0.446* |

| (0.064) |

(0.323) |

(0.660) |

(0.973) |

(0.143) |

(0.455) |

(0.024) |

| Single |

-0.254 |

-0.043 |

-0.097 |

-0.072 |

-0.287 |

-0.183 |

-0.397 |

| (0.270) |

(0.864) |

(0.695) |

(0.759) |

(0.390) |

(0.628) |

(0.089) |

| D4 (Age) |

After 1994 |

Reference |

| Before 1946 |

-0.054 |

1.088** |

0.953* |

0.222 |

-0.432 |

-0.705 |

0.097 |

| (0.887) |

(0.009) |

(0.021) |

(0.550) |

(0.416) |

(0.222) |

(0.793) |

| From 1946 to 1964 |

-0.275 |

0.707** |

0.701** |

0.327 |

0.172 |

-1.103*** |

0.420 |

| (0.215) |

(0.003) |

(0.003) |

(0.143) |

(0.605) |

(0.004) |

(0.063) |

| From 1965 to 1979 |

-0.016 |

0.722** |

0.643** |

0.253 |

-0.476 |

-0.511 |

0.108 |

| (0.944) |

(0.003) |

(0.007) |

(0.274) |

(0.167) |

(0.198) |

(0.644) |

| From 1980 to 1994 |

-0.009 |

0.362 |

0.354 |

0.242 |

-0.537 |

-0.313 |

0.184 |

| (0.966) |

(0.102) |

(0.097) |

(0.237) |

(0.084) |

(0.384) |

(0.385) |

| D5 (Household Size) |

None |

Reference |

| One |

0.004 |

-0.173 |

0.064 |

0.172 |

0.212 |

0.078 |

0.068 |

| (0.982) |

(0.348) |

(0.726) |

(0.326) |

(0.388) |

(0.787) |

(0.697) |

| Two |

0.031 |

-0.125 |

-0.090 |

-0.185 |

0.213 |

-0.192 |

0.236 |

| (0.866) |

(0.534) |

(0.648) |

(0.321) |

(0.433) |

(0.532) |

(0.437) |

| Three or more |

-0.352 |

0.086 |

0.042 |

-0.068 |

0.445 |

-0.297 |

0.294 |

| (0.262) |

(0.790) |

(0.891) |

(0.819) |

(0.271) |

(0.519) |

(0.130) |

| D6 (Education) |

Advanced University Degree (Graduate) |

Reference |

| College, CEGEP or Other Non-University Certificate or Diploma |

-0.069 |

-0.115 |

0.233 |

0.602** |

-0.357 |

-0.198 |

-0.526** |

| (0.714) |

(0.561) |

(0.240) |

(0.001) |

(0.172) |

(0.509) |

(0.005) |

| High School Diploma or Equivalent |

0.073 |

-0.390 |

0.115 |

0.576* |

-0.845** |

0.486 |

-0.658** |

| (0.743) |

(0.100) |

(0.627) |

(0.010) |

(0.008) |

(0.185) |

(0.004) |

| Registered Apprenticeship or Other Trades Certificate or Diploma |

0.294 |

0.158 |

0.336 |

0.311 |

-0.713 |

-0.289 |

-0.674* |

| (0.255) |

(0.579) |

(0.235) |

(0.249) |

(0.072) |

(0.520) |

(0.014) |

| Some High School |

0.067 |

-0.465 |

0.307 |

0.764 |

-0.070 |

-1.088 |

-0.188 |

| (0.895) |

(0.374) |

(0.540) |

(0.129) |

(0.918) |

(0.151) |

(0.685) |

| University Degree, Certificate or Diploma |

0.019 |

-0.255 |

-0.165 |

0.197 |

-0.425 |

0.320 |

-0.424* |

| (0.909) |

(0.150) |

(0.349) |

(0.233) |

(0.067) |

(0.232) |

(0.012) |

| D7 (Geographic Location) |

Atlantic Canada |

Reference |

| British Columbia |

0.221 |

0.419 |

-0.006 |

-0.242 |

0.309 |

-0.414 |

0.103 |

| (0.405) |

(0.151) |

(0.982) |

(0.367) |

(0.412) |

(0.341) |

(0.702) |

| Northern Region |

-0.862 |

-0.790 |

-0.189 |

-1.892 |

-1.874 |

-1.895 |

0.619 |

| (0.384) |

(0.449) |

(0.847) |

(0.091) |

(0.164) |

(0.360) |

(0.552) |

| Ontario |

0.149 |

-0.167 |

-0.068 |

-0.338 |

-0.066 |

-0.306 |

-0.074 |

| (0.529) |

(0.520) |

(0.787) |

(0.154) |

(0.844) |

(0.439) |

(0.759) |

| Prairies |

0.144 |

0.183 |

0.167 |

-0.119 |

0.153 |

-0.553 |

-0.349 |

| (0.572) |

(0.513) |

(0.536) |

(0.640) |

(0.677) |

(0.199) |

(0.176) |

| Quebec |

0.608* |

-0.295 |

0.348 |

0.210 |

0.075 |

-0.524 |

-0.007 |

| (0.015) |

(0.279) |

(0.193) |

(0.404) |

(0.832) |

(0.214) |

(0.977) |

| D8 (Income) |

Less than $35,000 |

Reference |

| Between $35,000 and $49,999 |

-0.324 |

-0.725* |

0.094 |

-0.201 |

0.290 |

-0.032 |

0.238 |

| (0.236) |

(0.014) |

(0.746) |

(0.474) |

(0.473) |

(0.945) |

(0.384) |

| Between $50,000 and $74,999 |

-0.044 |

-0.476 |

0.099 |

-0.124 |

0.007 |

-0.269 |

0.453 |

| (0.857) |

(0.078) |

(0.706) |

(0.627) |

(0.984) |

(0.517) |

(0.069) |

| Between $75,000 and $99,999 |

0.006 |

-0.397 |

0.185 |

-0.220 |

0.057 |

-0.408 |

0.261 |

| (0.981) |

(0.148) |

(0.484) |

(0.394) |

(0.878) |

(0.328) |

(0.298) |

| Between $100,000 and $149,999 |

0.088 |

-0.231 |

0.543* |

0.080 |

0.177 |

-0.043 |

0.637** |

| (0.720) |

(0.388) |

(0.035) |

(0.754) |

(0.621) |

(0.916) |

(0.009) |

|

$150,000 + |

0.096 |

-0.450 |

0.404 |

-0.279 |

0.066 |

-0.340 |

0.643* |

| (0.712) |

(0.113) |

(0.142) |

(0.299) |

(0.863) |

(0.433) |

(0.014) |

| D9 (Residential Zone) |

Suburban |

Reference |

| Small town, community, or rural |

0.108 |

0.173 |

-0.036 |

0.088 |

0.143 |

-0.288 |

0.260 |

| (0.467) |

(0.287) |

(0.821) |

(0.562) |

(0.503) |

(0.242) |

(0.087) |

| Urban Core |

0.313* |

-0.109 |

-0.341* |

-0.216 |

-0.195 |

-0.291 |

0.439** |

| (0.022) |

(0.455) |

(0.019) |

(0.120) |

(0.321) |

(0.191) |

(0.002) |

| Q1(Purchase History) |

No |

Reference |

| Yes |

0.861*** |

1.175*** |

0.121 |

0.009 |

0.082 |

-0.186 |

-0.054 |

| (0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.500) |

(0.960) |

(0.751) |

(0.543) |

(0.758) |

| |

(Perceived importance of price) |

No |

Reference |

| Yes |

0.043 |

-0.066 |

0.280 |

-0.043 |

0.263 |

-0.093 |

-0.694*** |

| (0.769) |

(0.674) |

(0.070) |

(0.768) |

(0.211) |

(0.702) |

(0.000) |

| |

(Perceived importance of origin) |

No |

Reference |

| Yes |

0.800*** |

1.874*** |

0.827*** |

-0.089 |

-0.135 |

0.401 |

1.122*** |

| (0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.530) |

(0.511) |

(0.091) |

(0.000) |

| |

(Price increase) |

No |

Reference |

| Yes |

0.200* |

0.275** |

0.270** |

0.044 |

-0.039 |

-0.205 |

-0.285** |

| (0.022) |

(0.003) |

(0.003) |

(0.617) |

(0.760) |

(0.155) |

(0.002) |

| Threshold coefficients |

(Strongly Disagree | Disagree) |

|

-1.110* |

-1.139 |

-1.616** |

-2.692*** |

-8.511*** |

-11.622*** |

-3.805*** |

| (0.047) |

(0.062) |

(0.007) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

|

(Disagree | Neither agree nor disagree) |

|

0.104 |

-0.704 |

-0.798 |

-1.227** |

-5.855*** |

-8.032*** |

-2.073*** |

| (0.851) |

(0.245) |

(0.174) |

(0.030) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |