Submitted:

22 March 2024

Posted:

25 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

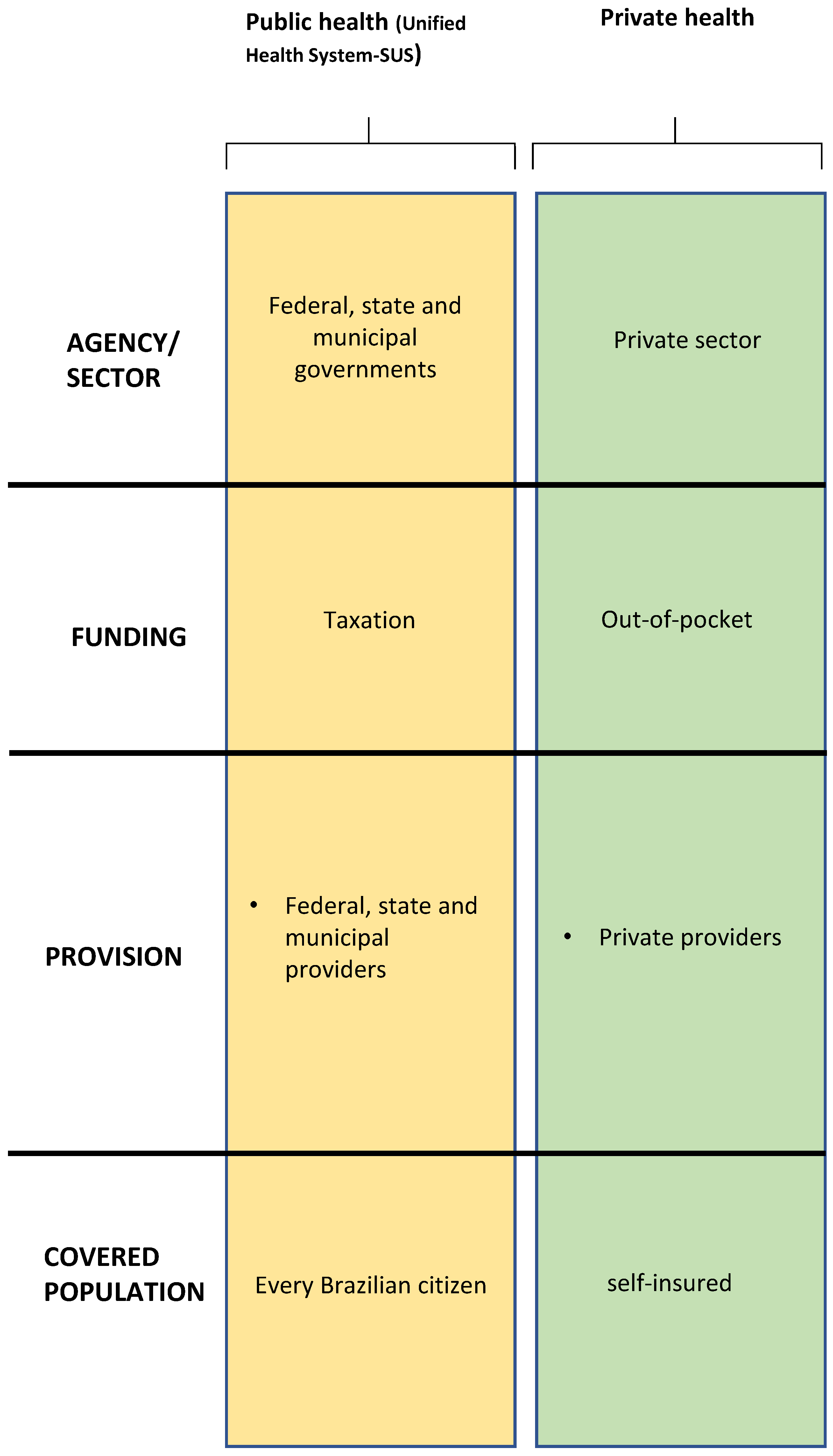

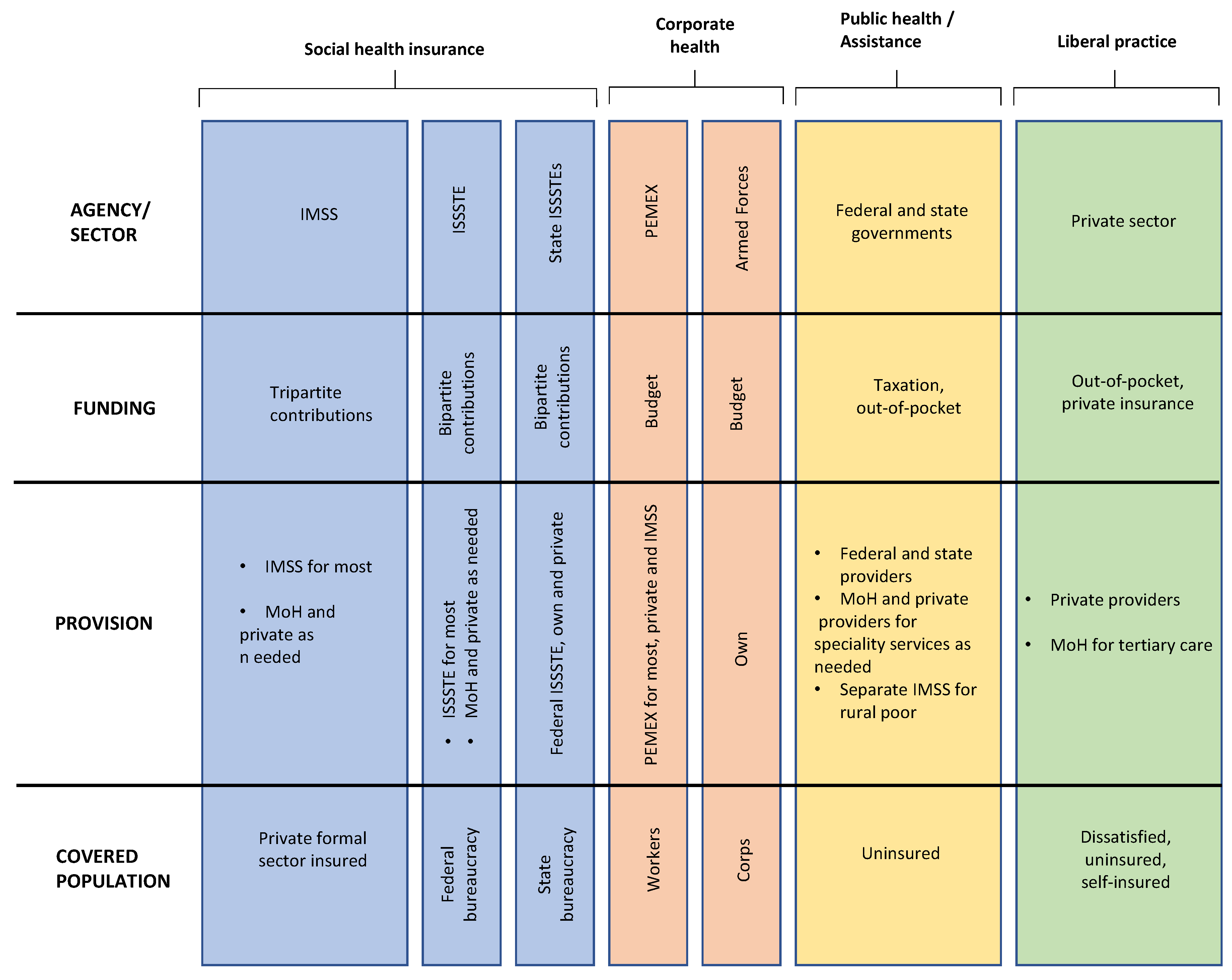

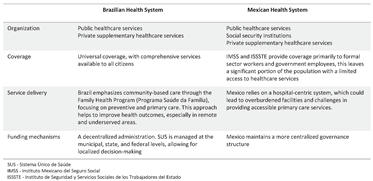

2. Health System in Latin America—A Brief Description of the Health Systems in Brazil and Mexico

2.1. Brazilian Health System

2.2. Mexican Health System

3. Methods

3.1. Panel Study Methodology

3.2. Data Acquisition

4. Results

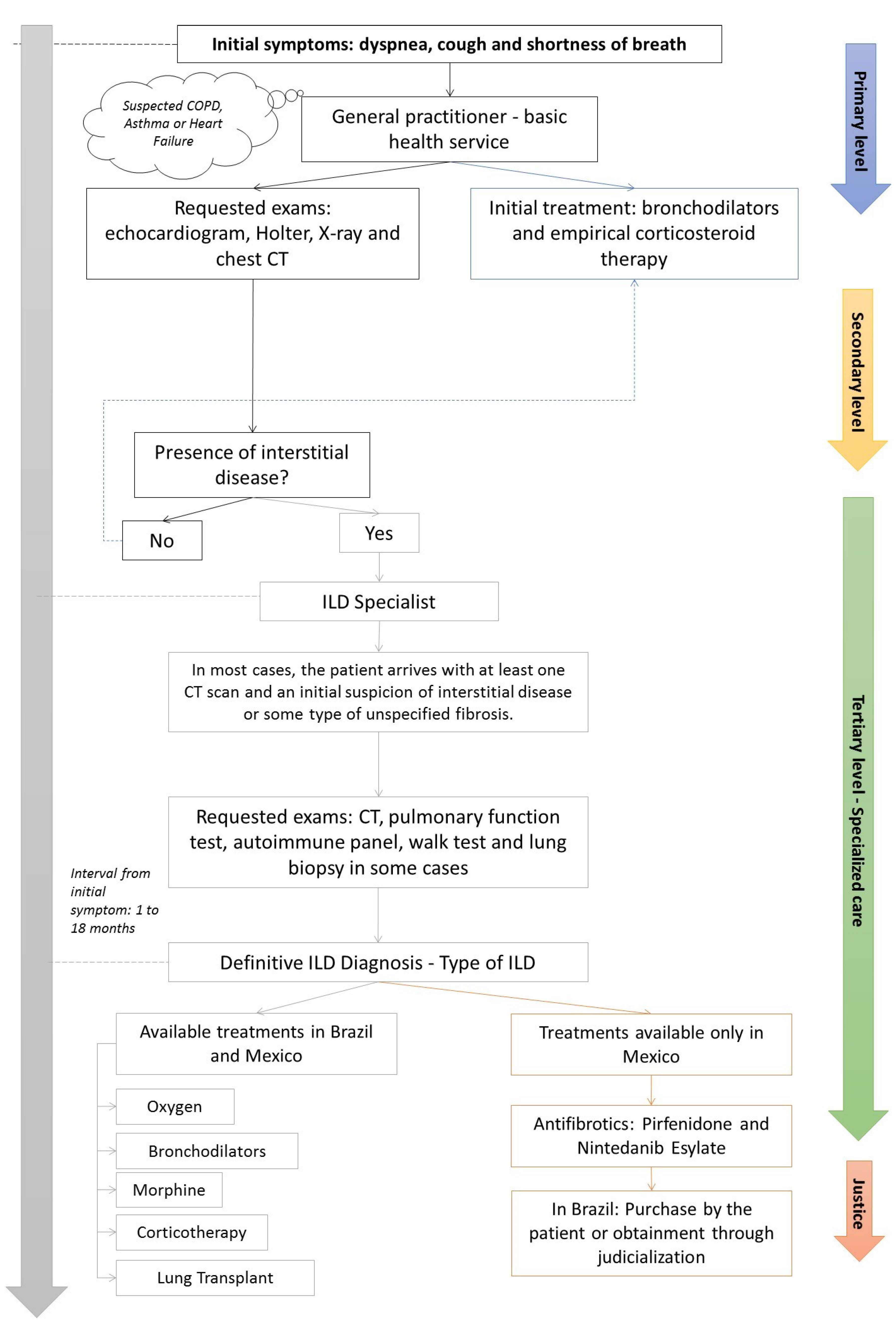

4.1. Patient’s Journey

4.2. Antifibrotic Therapy for ILD

4.3. ILD Associated to COVID-19

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Mikolasch TA, Garthwaite HS, Porter JC. Update in diagnosis and management of interstitial lung disease. Clin Med. 2017, 17, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociedade Brasileira De Pneumologia E Tisiologia. Diretrizes De Doenças Pulmonares Intersticiais Da Sociedade Brasileira De Pneumologia E Tisiologia. Jornal Brasileiro De Pneumologia. J Bras Pneumol. 2012, 38 Suppl. 2, S1–S133.

- Verma S, Slutsky AS. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis — New Insights. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356, 1370–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari S, Caminati A. IPF: new insight on pathogenesis and treatment. Allergy. 2010, 65, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller-Mang C, Ringl H, Herold C. Interstitial Lung Diseases. In: Nikolaou K, Bamberg F, Laghi A, Rubin GD, eds. Multislice CT. Medical Radiology. Springer International Publishing; 2017:261-288. 2. [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo P, Ryerson CJ, Putman R, et al. Early diagnosis of fibrotic interstitial lung disease: challenges and opportunities. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2021, 9, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer DJ, Martinez FJ. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Longo DL, ed. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, 1811–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher TM, Bendstrup E, Dron L, et al. Global incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2021, 22, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddini-Martinez J, Ferreira J, Tanni S, et al. Brazilian guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Official document of the Brazilian Thoracic Association based on the GRADE methodology. J Bras Pneumol. 2020, 46, e20190423–e20190423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez FJ, Safrin S, Weycker D, et al. The Clinical Course of Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Ann Intern Med 2005, 142(12_Part_1), 963. [CrossRef]

- Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018, 198, e44–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elicker B, Pereira CADC, Webb R, Leslie KO. Padrões tomográficos das doenças intersticiais pulmonares difusas com correlação clínica e patológica. J bras pneumol. 2008, 34, 715–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty KR, Andrei AC, King TE, et al. Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia: Do Community and Academic Physicians Agree on Diagnosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007, 175, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomelli R, Liakouli V, Berardicurti O, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: current and future treatment. Rheumatol Int. 2017, 37, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea1 G, Bocchino2 M. The challenge of diagnosing interstitial lung disease by HRCT: state of the art and future perspectives. J Bras Pneumol 2021, e20210199. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European lung foundation. Interstitial lung disease (ILD). accessed in 13/04/2021 available in: https://europeanlung.org/en/information-hub/lung-conditions/interstitial-lung-disease/.

- Brown KK, Martinez FJ, Walsh SLF, et al. The natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J. 2020, 55, 2000085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V, et al. Nintedanib in Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases. N Engl J Med. 2019, 381, 1718–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, YN. Nintedanib: A Review in Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Diseases. Drugs. 2021, 81, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil. Constituição (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília, DF: Senado; 1988.

- PAIM Jairnilson, Travassos CMR, Almeida CM, Bahia L, Macinko J. O sistema de saúde brasileiro: história, avanços e desafios. The Lancet 2011, 377, 11–31.

- Fiocruz. PublicoxPrivado. Acessado em junho de 2021. Disponível em: https://pensesus.fiocruz.br/publico-x-privado.

- Minas Gerais - Secretaria de Estado de Saúde. Acessado em junho de 2021. Disponível em: https://www.saude.mg.gov.br/sus.

- Mexico. Health Systems in Transition-Mexico Health System Review 2020 Vol. 22 No. 2 2020.

- Health Systems in Transition Vol. 22 No. 2 2020.

- Campos RTO, Miranda L, Gama CAP, Ferrer AL, Diaz AR, Gonçalves L, et al. Oficinas de construção de indicadores e dispositivos de avaliação: uma nova técnica de consenso. Estudos e pesquisas em psicologia 2010, 10, 221.

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA) (Brasil). Consultas. Access in 21.Available in: https://consultas.anvisa.gov.br/#/medicamentos/25351456304201563/. 20 June.

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA) (Brasil).Consultas. Access in 21. Available in: https://consultas.anvisa.gov.br/#/medicamentos/25351496519201517/. 20 June.

- Comissão Nacional de Incorporação de Tecnologias no SUS (CONITEC) (Brasil). Access in 21. Available at: http://conitec.gov.br/tecnologias-em-avaliacao-demandas-por-status. 20 June.

- Mexico - Secretaria de Salud Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Access in 21. Available in: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/196773/Huerfanos_Otorgados_2015.pdf. 20 June.

- Mexico. Proposición con punto de acuerdo por el que la comisiòn permanente del h. congreso de la unión con pleno respeto a la división de poderes, exhorta a la secretaría de salud para que, en coordinación con las autoridades competentes analice definir a la fibrosis pulmonar idiopática (fpi) como una enfermedad catastrófica y fortalezca las acciones y estrategias para su prevención, detección y, en su caso, brindar el tratamiento oportuno en dicho padecimiento. Ciudad de México a, 24 de julio de 2018.

- Expert Panel: Rubin Adalberto MD, Grassman Ricardo MD, Díaz-Verduzco Manuel de Jesús MD, and Alemán-Márquez Ángel, from the Expert Panel of Reference Centers in Interstitial Lung Diseases in Latin America. June 2021.

- Rai DK, Sharma P, Kumar R. Post covid 19 pulmonary fibrosis. Is it real threat? Indian Journal of Tuberculosis. 2021, 68, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Zhou H, Zhou Y, et al. Risk factors associated with disease severity and length of hospital stay in COVID-19 patients. Journal of Infection. 2020, 81, e95–e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guler SA, Ebner L, Aubry-Beigelman C, et al. Pulmonary function and radiological features 4 months after COVID-19: first results from the national prospective observational Swiss COVID-19 lung study. Eur Respir J. 2021, 57, 2003690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrove GP, Bianchi P, Danese S, Lederer DJ. Barriers to timely diagnosis of interstitial lung disease in the real world: the INTENSITY survey. BMC Pulm Med. 2018, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vašáková M, Mogulkoc N, Šterclová M, Zolnowska B, Bartoš V, Pla ková M, et al. Does timeliness of diagnosis influence survival and treatment response in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Real-world results from the EMPIRE registry. European Respiratory Journal 2017; 50 (Suppl 61): PA4880. Poster presentation at the ERS International Congress 2017, 9–13/9/2017, Milan.

- Dempsey TM, Sangaralingham LR, Yao X, Sanghavi D, Shah ND, Limper AH. Clinical Effectiveness of Antifibrotic Medications for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019, 200, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).