Background

Schistosomiasis also known as bilharzia remain a public health threat. The disease co-morbidities including HIV and other STIs is common in poor settings [

1,

2,

3]. The control of schistosomiasis remain a public health issue with a global estimate of 200,000 annual death rate [

4]. About 25% of people with HIV are reported to be co-infected with helminths including schistosomiasis [

5]. Praziquantel treatment has shown great progress for urinary schistosomiasis into the therapeutic arsenal [

6]. The benefits of this drug are its easy administration, low toxic effects and low side effect intensity [

7]. These significant factors have contributed to the tolerance of individualized and mass treatments and their easy application, however, failure of various proportions of Praziquantel treatment was reported [

8,

9,

10]. Traditional medicine (TM) has been widely used for schistosomiasis in Africa [

11]. People living in third world countries tend to use traditional medicine in complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs), including schistosomiasis and co- morbidities according to their attitudes and beliefs [

12,

13]. This study aimed to assess perceptions of participants on the availability of Praziquantel and to ascertain whether individuals infected with schistosomiasis used concurrently African traditional medicines with this treatment.

An increase in the incidence of non-communicable diseases contributes greatly to the burden of schistosomiasis and adds burden to already strained health systems due to the high prevalence of infectious diseases [

14]. For mass treatment to prevent co-morbidities in schistosomiasis management, the World Health Organization (WHO) suggested preventive chemotherapy in primary healthcare systems for elimination of the infection [

15,

16]. Traditional medicine has played an important role in rural areas where many plants are alternatively used to treat infectious diseases including schistosomiasis but not well documented [

17]. About 70 and 80 percent of South Africans are estimated to use traditional medicine [

18].

South Africa, like many developing countries, has a pluralistic health care system where a modernized first- world healthcare system coexists with a variety of non- conventional medical systems, including traditional practices and beliefs [

19]. TM has demonstrated its contribution to the management of schistosomiasis, the reason for the increased use of TM, including dissatisfaction with the effectiveness of Praziquantel, with certain concerns about adverse effects and misconceptions that TM is seen as natural and therefore safer, even if used with prescription drugs or, in particular, when used [

20]. Therefore, it is assumed that the referral system will play a crucial role in health and well-being through cooperation between health professionals and traditional health Practitioners [

21,

22]. The role of TCAM in the provision of primary health care is recognized in the health policy documents of some Sub- Saharan African countries in the context of limited access to essential health services, especially in poor settings [

23]. The concurrent use of conventional treatement with medicinal plants is not well documented. The documentation through patients personal medical records (PMR) should allow people to track their medical information. Preserving a PMR promotes greater personal involvement in healthcare and emphasizes communication between individuals and clinicians [

24].

The perceptions on the concurrent use of Praziquantel with herbal medicine in the management of schistosomiasis is not well documented. This study assessed respondents’ views and perceptions in the use of Praziquantel and traditional medicine to treat schistosomiasis. The collected data will serve as reference for evaluating the impact of the concurrent use of traditional end modern medicine in the management of schistosomiasis.

Methods

Ethical Considerations

The Biomedical Research Ethics of the University of KwaZulu-Natal under reference BE477/17 and the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health under reference number HRKM451/17 approved this study and informed consents was sought from all respondents.

Study Design

This study was a cross–sectional descriptive study, using an exploratory approach. This approach was used to bring additional insights in understanding the management of schistosomiasis in rural communities of KwaZulu-Natal. Three sources of data were used citing HCPs, Patients seen by THPs and patients who might have crossed the conventional and traditional treatment.

Study Sites

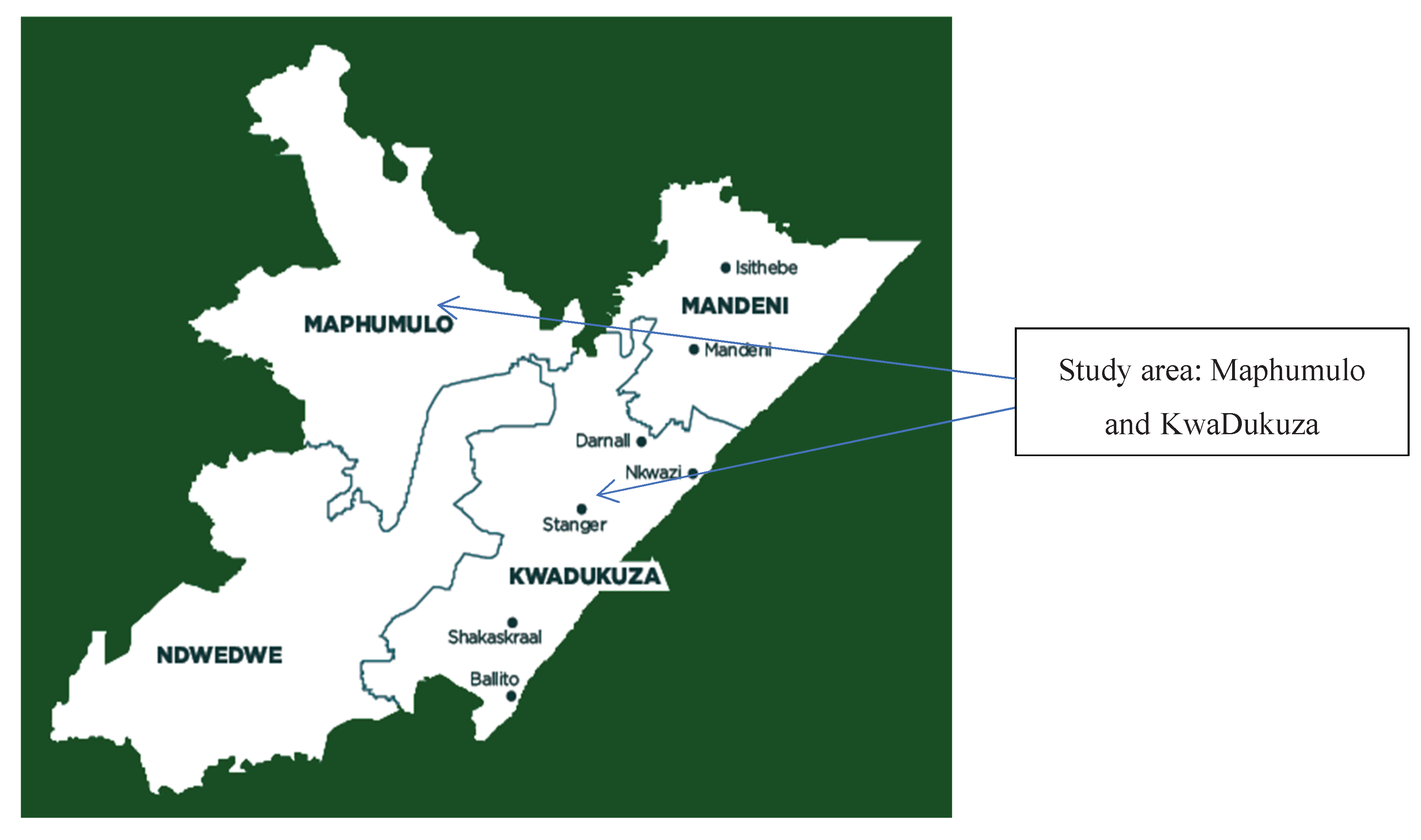

ILembe District Municipality is situated on the east coast of KwaZulu-Natal bordering the Indian Ocean, it is surrounded by: Umzinyathi to the north, the Indian Ocean to the east, eThekwini to the south (Durban), Umgungundlovu to the west and Uthungulu to the north-east. ILembe consists of four local municipalities located between Durban and Richards Bay: Mandeni, KwaDukuza, Maphumulo and Ndwedwe. The town straddles the Tugela River [

25]. This study was conducted in areas surrounding Kwadukuza and Mamphumulo municipalities where healthcare facilities visited citing Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC): Amandlalathi, Mpise, Otimati, Oqaqeni, Mpumelelo and Shakaskraal Clinics, one Community Healthcare centre (CHC): Kwadukuza Clinic, Level one of Healtchcare: Umphumulo and Untunjambili Hospitals, Level two of healthcare: Stanger Hospital. A previous study in ILembe district reported that schistosomiasis was prevalent over the past years [

26].

Figure 1.

A geographic map of the in iLembe district.

Figure 1.

A geographic map of the in iLembe district.

Study Population, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Study Population

This study recruited healthcare workers including medical doctors, pharmacists, nurses and pharmacist assistants from 10 healthcare facilities. Traditional health practitioners interviewed in a previous study as well as patients recruited from the five different facilities during the data collection period from January to April 2023 referred patients included in this study to the researchers.

Inclusion Criteria

Respondents who have had the infection between 2020 and early 2023 were included to generate keys findings [

27,

28]. Ten patients who had the disease outside the study period (2018 and end 2019) were included to gather their perceptions about the concurrent use of traditional medicine and conventional prescribed antischistosomal medicines. Male and female respondents aged 18 years old and above with schistosomiasis history were included.

Exclusion Criteria

Healthcare workers managing schistosomiasis and patients who had the disease but not available at the time of data collection were excluded from this study. Patients with doubtful information about schistosomiasis were excluded as well from this study.

Sampling Technique and Study Size Calculation

A purposeful sampling method was used to gather data from respondents who have treated, either managed or suffered from schistosomiasis during the study period.

This study aimed to detect at least 10% difference in the concurrent use of traditional medicine and conventional antischistosomal treatment, thus the sample size calculation was based on an expected prevalence of 10% considered as a response distribution, a margin of error of 5% and 95% confidence intervals [

29]. The population in the study area was estimated at 657 612 (

https://municipalities.co.za/demographic/117/ilembe-district-municipality). Thus, the minimum recommended sample size was 139 respondents. The sample size of respondents was determined using the formula as described by Lwanga (1991) and Daniel (1999) [

29]:

Where Z statistic as 1.96 for the confidence level of 95%, P is 0.8 as the expected proportion of the characteristics were measured in the study area [

30]; d is the precision of 0.05 for 95% confidence interval. Since it was a prospective study, attritions were expected for various reasons, unsigned consent and assented forms, absence of respondents, failure to provide information or not being available during subsequent survey; an increase of 10-20% was added to the minimum sample size of 139 yielding 159 respondents included in the final analysis.

Procedure for Recruitment and Selection of Respondents

Three categories of respondents were recruited in this study. THPs from the previous study directed the researchers to their patients in their different locations in the study area. The researchers approached them during the day, for those not available interviews were done via phone calls. An isiZulu speaking person assisted with translation for those respondents who could not express themselves in English. Healthcare workers who have treated schistosomiasis were recruited in the 10 facilities and were interviewed at their workplace during business hours. HCWs directed the researchers to patients who had a history of schistosomiasis at the outpatient department. Researchers went to check the patients’ medical records as per healthcare workers’ directions.

Data Analysis

All data were first entered twice in an Excel spreadsheet, cross - checked and then transferred to data were entered into and analyzed by statistical package for social sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics) statistical software version 25.0 package for Windows. Descriptive statistics were used including frequency, percentage, and categorical data represented as tables. Analysis of associations between; continuous variable used Chi-squared tests. A p value ≤ 0.05 was estimated as statistically significant. Each of the selected respondents gave their point of views in the management of schistosomiasis. This approach was used to generate in-depth understanding of the issue [

28]. Data were reviewed, individual components were analyzed and compared to other cases as a requirement of collective case studies [

32].

Results

Demographic Assessments of Respondents

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents showed that the majority were recruited in Stanger Hospital (46/159 (28.9%) [22 – 36.6]). Most of them were females (120/159 (75.5%) [68 – 81.9]), and where not married (98/159 (61.6%) [53.6 – 69.2]), 56/159 (35.2%) [27.8 – 43.2] had a degree as the highest study level. On respondents’ profession 93/159 (58.5%) [50.4 – 66.2] were nurses. The majority (104 (65.4%) [57.5 -72.8]) were Christians. See

Table 1 for details.

Phase 1: Assessment of healthcare professionals and patients’ perception towards use of TM and orthodox medicine for the treatment of Schistosomiasis with co-morbidities

The phase one enrolled 20 patients referred to researchers by THPs in the previous study, 124 HCWs in healthcare facilities selected in the study as well as 15 patients who have been using the mainstream healthcare system for the management of schistosomiasis.

Self-Reports of HCWs on Availability of Praziquantel (Biltricide®)

The comparison of the availability of Praziquantel (Biltricide®) and the level of healthcare facilities shows that out of the 124 respondents, the majority (106/124; 85.5%) argued that Praziquantel (Biltricide®) was available in the facilities. Most of the respondents (114/124; 91.9%) reported that medicines were purchased directly by the facilities for free distribution to patients. Although about (10/124; 8.1%) of the respondents argued that they did not know if medicines were purchased directly by the facilities for distribution to patients. More so, out of the 91.9% of the respondents that argues that medicines were purchased directly by the facilities for distribution to patients, 49.2% of them worked in rural areas and 42.7% of them worked in semi-urban areas.

A correlation has been found with a p-value set at < 0.05, suggesting that there is a strong relationship between level of healthcare facilities and the availability of Praziquantel (Biltricide®). The level of a healthcare facilities is a key factor that determines the availability of Praziquantel (Biltricide®) in rural area facilities (p = 0.006).

Table 2.

Assessment of HCWs perception on Praziquantel (Biltricide®) availability.

Table 2.

Assessment of HCWs perception on Praziquantel (Biltricide®) availability.

| |

Praziquantel (Biltricide®) Availability by respondents(n) |

| Healthcare Facilities/ Number of facilities (10) |

Yes |

No |

Don’t Know |

Total, n= 124, N, (%), [CI 95%] |

| PHC (6) |

29 |

Nil |

1 |

30 (24.2%) [17 – 32.7] |

| CHC (1) |

7 |

Nil |

Nil |

11 (5.6%) [2.3 – 11.3] |

| Level 1 (2) |

28 |

4 |

9 |

41 (33.1%) [24.9 – 42.1] |

| Level 2 (1) |

42 |

Nil |

4 |

46 (37.1%) [28.6-46.2] |

| Total |

106 |

4 |

14 |

124 (100.0%) |

When testing the relationship between the Praziquantel (Biltricide®) availability perception and the concurrent use of TM and conventional treatment (CT) perception for the treatment of Schistomiasis, there was no significant relationship between the concurrent use of TM and CT by patients for the treatment of schistosomiasis in the study area (X2 = 3.042, p = 0.551).

Self-Reports by HCWs About Patients’ Record Keeping and Visits to Healthcare Facilities for Schistosomiasis

It is indicated that all respondents working in the different level of healthcare facilities kept record of patients suffering from schistosomiasis using patients’ files in most cases (105/124; 84.7%). Most of the 124 respondents (111/124; 89.5%) always retrieved and consulted patients’ files for follow up each time they visit facilities.

Table 3.

Assessment of record keeping and visits to healthcare facilities for schistosomiasis.

Table 3.

Assessment of record keeping and visits to healthcare facilities for schistosomiasis.

| |

Types of Record Keeping |

| Facilities |

Filing System |

Registry System |

Notification form (NMC) |

Others |

Total N, (%), [CI 95%] |

| PHC |

18 |

Nil |

12 |

Nil |

30 (24.2%) [17– 32.7] |

| CHC |

7 |

Nil |

Nil |

Nil |

7 (5.6%) [2.3 – 11.3] |

| Level 1 |

36 |

Nil |

Nil |

5 |

41 (33.1%) [24.9 – 42.1] |

| Level 2 |

44 |

2 |

Nil |

Nil |

46 (37.1%) [28.6 – 46.2] |

| Total |

105 |

2 |

12 |

5 |

124 (100.0%) |

Perceptions of HCWs about the Concurrent Use of Traditional Medicine and Conventional Prescribed Medicines

Majority of healthcare professionals (76/124; 61.3%) reported that they did not know whether their patients used concurrently TM and CT for the treatment of Schistomiasis. In comparing the availability of Praziquantel (Biltricide®) in facilities with its concurrent use with TM showed that most of the respondents (62/124; 50.0%) of the 85.5% of the respondents that argued positively on the availability of the Praziquantel (Biltricide®) in the facility reported that their patient do not concurrently used TM and CT for the treatment of schistomiasis.

Knowledge and Prevalence of Schistosomiasis among Patients Seen by Both THPs and HCWs

On views and experiences of respondents on the treatment of schistosomiasis, 12 respondents out of 15 who visited healthcare facilities and met THPs were women. The maximum duration of the disease reported was a month as reported many respondents using TM and those using CT. A treatment, which consisted of antibiotics (15 days prescription) and Praziquantel (Biltricide®) (single dose), was reported by respondents. Patients referred by THPs to the researchers indicated the use of medicinal plants in the management of schistosomiasis. They all reported that they did not use conventional treatment for schistosomiasis. Most respondents (8/20, 40%) seen by THPs used TM occasionally while the ones who crossed the two systems used TM only once.

On the other side, patients seen by HCPs reported that schistosomiasis were frequent in women (10/15, 66.7%), they reported as well that the disease duration was a month (11/15, 73.3%). It is reported that 8/15, 53.3% have crossed CT and TM but they used the mainstream healthcare facility to be examined as asked me them THPs to find out if the disease was treated well. Most respondents reported to have been on Biltricide®, single dose and Antibiotics (12/15, 80%). Results showed that 10/15, 66.7% agreed to have used TM for schistosomiasis not on regular basis but only once.

Table 4.

Table 4. Knowledge and prevalence of schistosomiasis among patients.

Table 4.

Table 4. Knowledge and prevalence of schistosomiasis among patients.

| Category (variables) |

Patients seen by only by THPs, n=20 |

Patients seen by HCPs, n=15 |

Total, N= 35 N (%) [CI 95%] |

| Type of Schistosomiasis |

Bilharzia in women |

Nil |

12 |

12 (34.3%) [19.1-52.2] |

| Bilharzia in man |

Nil |

3 |

3 (8.6%) [1.8-23.1] |

| Disease duration |

Two weeks |

Nil |

2 |

2 (5.7%) [0.7-19.2] |

| Almost month |

Nil |

1 |

1 (2.9%) [0.1-14.9] |

| A month |

14 |

11 |

25 (71.4%) [53.7-85.4] |

| Two months |

6 |

1 |

7 (20%) [ 8.4-36.9] |

| Treatment duration |

No modern treatment, I went to the facility to be examined as asked me the THP to find out if the disease was treated well |

Nil |

8 |

8 (22.9%) [10.4-40.1] |

| 15 days |

10 |

Nil |

10 (28.6%) [14.6-46.3] |

| One day |

10 |

1 |

11 (31.4%) [16.9-49.3] |

| Types of treatment received in the past for this disease |

Biltricide |

Nil |

3 |

3 (8.6%) [1.8-23.1] |

| Imbiza |

Nil |

12 |

12 (34.3%) [19.1-52.2 ] |

| Current treatment for the disease |

Imbiza (Herbal medicine mixture) |

18 |

15 |

33 (94.3%) [80.8-99.3] |

| Modern medicine (didn’t use TM after consulting the THP) |

2 |

Nil |

2 (5.7%) [0.7-19.7] |

| Other treatment used than conventional medicines for schistosomiasis |

Yes |

Nil |

12 |

12 (34.3%) [19.1-52.2 ] |

| No |

Nil |

3 |

3 (8.6%) [1.8-23.1] |

| Conventional medicine used for schistosomiasis |

Biltricide, single dose |

Nil |

2 |

2(5.7%) [0.7-19.7] |

| Biltricide, single dose and Antibiotics |

Nil |

12 |

12(34.3%) [19.1-52.2] |

| None |

Nil |

1 |

1(2.9%) [0.1-14.9] |

| Frequency of use of TM/ CT for schistosomiasis |

Occasionally |

8 |

5 |

13(37.1%) [21.5-55.1] |

| Only once |

5 |

10 |

15 (42.9%) [26.3-60.6] |

| Weekly |

7 |

Nil |

7 (20%) [8.4-36.9] |

Perceptions about the Use of TM Either Alone or in Combination with Conventional Medicines among Patients Seen by Both THPs and HCWs

Respondents reported that they used TM only when stopped the use of modern medicine for those who have crossed the two healthcare systems (9/15, 60%), they were motivated by their curiosity and belief on the choice of the use of traditional medicines (12/15, 80%). They reported to have used TM because it stopped the bleeding for those who visited healthcare facilities and used TM (12/15, 80%).

The majority (12/15, 80%) of respondents reported that TM can be recommended to be used widely against schistosomiasis. Patients (8/15, 53.3%) who crossed the two systems mentioned that they did not disclose to HCPs that they used TM because they usually tell them to avoid the use of TM because it damages organs or makes the modern treatment not work properly when using conventional treatment with traditional herbs. The overall yearly cost for TM used was R1000 or 84.75$ (Rate 1$=11.8R at the time of data collection) reported by the majority (8/15, 53.3%) of patients who have used CT and TM.

Respondents who consulted THPs self-reported a particular perceived benefit obtained from the use of TM including a good treatment of the disease and relief of its symptoms (18/20, 90%). Few respondents (8/20, 40%) reported experiencing unwanted effects after the use of TM such as running stomach (diarrhoea), vomiting and nausea; however, they were satisfied on the performance of TM used for schistosomiasis. Most respondents seen by THPS (18/20, 90%) reported that TM can be recommended to be used widely against schistosomiasis.

Table 5.

Table 5. Perceptions on the use of TM either alone or in combination with conventional medicines.

Table 5.

Table 5. Perceptions on the use of TM either alone or in combination with conventional medicines.

| Category (variables) |

Patients seen only by THPs, n=20 |

Patients seen by HCPs, n=15 |

Total, N= 35 N (%) [CI 95%] |

| Explanation of the use of conventional and Traditional medicine |

The respondent started using TM only when stopped the use of modern medicine |

Nil |

9 |

9 (25.7%) [12.5-43.3] |

| Was using conventional medicine during the same period as he was using TM so that both will work together |

Nil |

6 |

6 (17.1%) [6.6-33.6 ] |

| Motivation/ perceptions of the choice of the use of traditional medicines |

Curiosity and belief |

Nil |

12 |

12 (34.2%) [19.1-52.2 ] |

| MM disappoint |

Nil |

3 |

3 (8.6%) [1.8-23.1] |

| Benefit obtained from the use of TM |

Yes, no more bleeding, nor blood and itching when urinating |

Nil |

12 |

12 (34.3%) [19.1-52.2 ] |

| None |

Nil |

3 |

3 (8.6%) [1.8-23.1] |

| Disease treatment and relieved symptoms |

18 |

Nil |

18 (51.4%) [34-68.6] |

| It didn’t work well |

2 |

Nil |

2 (2.7%) [0.7-19.7] |

| Any unwanted effect from the used of any medicines either alone or in combination (CT and/or T) for Schistosomiasis |

Yes |

8 |

Nil |

8 (22.9%) [10.4-40.1] |

| No |

12 |

15 |

27 (77.1%) [59.9-89.6] |

| Experience on any unwanted effect from the TM use (specification) |

Running stomach (diarrhoea), vomiting and Nausea |

9 |

Nil |

9 (25.7%) [12.5-43.3] |

| None |

11 |

Nil |

11 (31.4%) [16.9-49.3] |

| Satisfaction on the performance of TM/CT used for Schistosomiasis |

Satisfied |

18 |

12 |

30 (85.7%) [69.7-95.2] |

| No idea |

2 |

3 |

5 (14.2%) [4.8-30.3] |

| Use of either TM/both against Schistosomiasis and recommend it for someone with Schistosomiasis |

Yes |

18 |

12 |

30 (85.7%) [69.7-95.2] |

| Not sure |

2 |

3 |

5 (14.2%) [4.8-30.3] |

| Choice of TM over CT |

Yes, just went to Hospital for exam not treatment |

Nil |

5 |

5 (14.2%) [4.8-30.3] |

| Yes, Solution and no coming back of the infection |

Nil |

7 |

7 (20%) [8.4-36.9 ] |

| No |

Nil |

3 |

3 (8.6%) [1.8-23.1] |

| Mention to the HCPs of TM use for Schistosomiasis management |

Yes |

Nil |

3 |

3 (8.6%) [1.8-23.1] |

| No |

Nil |

12 |

12 (34.3%) [19.1-52.2 ] |

| Patient disclosure to Doctor on TM use |

He said it doesn’t work and might not be helpful |

Nil |

1 |

1 (2.9%) [0.1-14.9] |

| He said that traditional medicines can have side effects that won’t be controlled if used together with traditional herbs |

Nil |

6 |

6 (17.1%) [6.6-33.6] |

| The HCP said that it damages organs or make the modern treatment not work properly |

Nil |

8 |

8 (22.9%) [10.4-40.1] |

| Traditional medicine supply |

From the market of traditional herbs |

Nil |

5 |

5 (14.2%) [4.8-30.3] |

| From the relations |

Nil |

2 |

2 (2.7%) [0.7-19.7] |

| From the TM practitioner |

Nil |

8 |

8 (22.9%) [10.4-40.1] |

| Cost of TM for a year |

Almost R 1000 (84.75$) |

Nil |

8 |

8 (22.9%) [10.4-40.1] |

| Almost R 1500(127.11$) |

Nil |

5 |

5 (14.2%) [4.8-30.3] |

| Almost R 2000 (169.49$) |

Nil |

2 |

2 (2.7%) [0.7-19.7] |

Phase 2: Assessment of Medical Chart Records of Patients with History of Schistosomiasis

Evidence of Documentation of the Use of TM for Schistosomiasis and Comorbidities among Patients

In phase two, medical chart records of patients with schistosomiasis were analyzed. Overall, 39 medical chart records were analyzed and none documented the use of TM. Out of 39 files retrieved, two medical records were from patients seen in phase one. The information given verbally to researchers on the use on traditional treatment was not reported in their medical chart records. These two above patients fell among seven cases of patients with history of schistosomiasis and other comorbidities including HIV and other STIs.

Table 6.

Schistosomiasis with other associated conditions.

Table 6.

Schistosomiasis with other associated conditions.

| Categories |

Frequency of associated disease conditions to schistosomiasis |

Total |

N (%) 95% CI |

| Frequency of schistosomiasis |

Sub-categories |

|

|

|

| schistosomiasis alone |

11 |

None |

11 |

(8.5%) [4.3-14.6 ] |

| schistosomiasis associated with HIV |

5 |

Diarrhoea (3), Genital ulcers or itching (1) and other (5) |

9 |

14 |

(10.8%) [6-17.4 ] |

| 7 |

STI & TB (7) and other (31) |

38 |

45 |

(34.6%) [26.5– 43.5] |

| 3 |

other non-infectious diseases: Hypertension (3) and other (5) |

8 |

11 |

(8.5%) [4.3-14.6] |

| 5 |

Hematuria (5), respiratory problem (2) and other (5) |

12 |

17 |

(13.1%) [7.8-20.1] |

| schistosomiasis associated with other diseases conditions |

2 |

Hypertension (2), Blood in urine (1), Genital ulcers or itching (1) and other (9) |

13 |

15 |

(11.5%) [6.6 – 18.3] |

| 6 |

Hematuria (6), STI & TB (1) and other (4) |

11 |

17 |

(13.1%) [7.8 – 20.1] |

| Total |

39 |

91 |

130 |

|

Assessment of Prescribed Conventional Medicines for Schistosomiasis and Comorbidities

Table 7 below presents the most prescribed medicines for patients with history of schistosomiasis and comorbidities. The most frequent documented medicine for schistosomiasis was Praziquantel (Biltricide

®). For infectious comorbidities, antiretroviral medicines (60/219, 27.39%) and antibiotics (44/219, 20.1%) were the most prescribed medicines with Praziquantel (Biltricide

®).

Discussion

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the community, three hospitals, one community health clinic and six primary health clinics in the iLembe District in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. This study found that at least sixty percent of the HCPs (76/124; 61.3%) reported that they did not know whether their patients used concurrently TM and CT for the treatment of schistomiasis. This finding may be justified by an old study stating that patients who crossed the two healthcare systems did not fully disclose their use of TM to HCWs [

33]. In addition, another study in Western cape, South Africa reported that HCWs were stigmatizing the concurrent use of TM and CT in health conditions [

34].

It was reported that there was no relationship between the availability of Praziquantel (Biltricide

®) in healthcare facilities and the concurrent use of TM and CT for the treatment of Schistomiasis (X

2 = 3.042, p = 0.551). Thus, the availability of Praziquantel (Biltricide

®) in the facilities does not imply the concurrent use of TM and CT by patients for the treatment of schistomiasis in the study areas due to the belief on the use of TM. This finding is in agreement with another study which demonstrated that Praziquantel was available in endemic areas of South Africa including KwaZulu-Natal [

35]. Another study argued that patients crossed from the mainstream healthcare system to traditional medicine, despite the availability of conventional treatment [

36]. The same authors further indicated that HCWs in charge had to be increased in endemic areas for follow-ups to avoid the risk of reinfection and which might be the reason why patients use cross the two healthcare systems. These viewpoints above may justify the concurrent use of CT and TM in the management of schistosomiasis. Many studies have suggested In their study, suggested that the treatment on NTDs has to be extended to the entire community considering socio-cultural beliefs and accessibility [

37,

38].

The findings show that the maximum treatment duration for schistosomiasis was a month for follow up as reported the majority of respondents seen by THPs. Not much is known about the treatment duration for those crossing the two healthcare systems. This finding met the length of treatment duration of schistosomiasis using TM as reported in a study conducted in Mali where the treatment duration was reported to be 1 to 30 days for schistosomiasis to be treated depending on the plant used [

39].

Most respondents seen by THPs in this study used medicinal plants for the management of schistosomiasis; they did not use orthodox conventional medicines while a few respondents crossed the two systems. The use of TM was previously reported for their antihelmintic activity for the management of schistosomiasis in Zimbabwe [

40]. This was also supported by another study conducted in Cameroon on the antischistosomal activity of African medicinal plants [

41].

Another finding from this study was a perceived credit to be given to traditional healers for the management of schistosomiasis. Traditional medicine representing a parallel healthcare system to orthodox medicine, the researchers in this study hold a view that collaboration between HCWs and THPs should be improved. This is in line with another study which indicated that collaboration of THPs and HCWs was an important component of controlling the concurrent misuse of TM and conventional medicine by patients to avoid uncontrollable side effects [

42].

A minority of patients seen by THPs in this study (8/20, 40%) reported unwanted effects citing running stomach (diarrhoea), vomiting and nausea after the use of TM for schistosomiasis. A study conducted in South Africa showed that the use of TM came with unwanted effects due to the way plants were used including their preparation and dosage[

43]. The same authors also recommended that communication between users and prescribers was an important component in the healing process where people relied on TM as primary healthcare.

This study reported that community clients consulting THPs collected their medicinal treatment mostly from THPs and the overall yearly cost reported was R1000 (84.75

$). This finding is in agreement with another study conducted in South Africa showing that TM was not a cheaper alternative easily accessible but expensive comparing to local public healthcare facilities where treatment is free of charge sometime [

44].

Findings of this study revealed that schistosomiasis was associated mainly with sexual transmitted infections mostly HIV. Another study also suggested that schistosoma infection might have an active role in HIV transmission and disease progression within low and middle income settings [

45]. Another study showed that the co-infection of schistosomiasis with HIV had immunological consequences [

46]. Another study conducted in Tanzania reported that co-infections of HIV and Schistomiasis has a an effect on the patient immune system [

47].

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study investigated the traceability on the concurrent use of CT and TM in the management of schistosomiasis with comorbidities. It could be of interest for the improvement of the collaboration of THPs and HCWs in the management schistosomiasis. However, a few limitations were due to relatively small sample size, the results possibly cannot be generalized to the entire population of patients with history of schistosomiasis and comorbidities in South Africa. Therefore, similar studies are warranted in other parts of South Africa about schistosomiasis being a neglected tropical disease and not too many people suffering from it in the general population.

Conclusion

In this study, HCWs reported that they were not aware whether their patients used concurrently TM and CT for the treatment of schistomiasis. Furthermore, patients seen by THPs in this study relied on medicinal plants for the management of schistosomiasis; they did not use orthodox conventional medicines while a few of them crossed the two systems. This study found that respondents believed that credit could be given to traditional healers for the management of schistosomiasis. More future investigations in endemic areas of South Africa could contribute to the knowledge of other medicinal plants used by THPs for schistosomiasis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G-A.M., writing—original draft preparation, A.G-A.M. and M.N., writing—review and editing, A.G-A.M, N.A.M, S.C.U, T.W.M, K.G.M, N.N, B.S.A, K.B and H.M.K; supervision, M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Biomedical Research Ethics of the University of KwaZulu-Natal under reference BE477/17 and the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health under reference number HRKM451/17 approved this study and informed consents was sought from all respondents.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the tremendous collaboration and support of the Indigenous Knowledge Holders and the Traditional Healers Organisation leaders in the iLembe District. A.G-A.M received a stipend and running expenses from the College of Health Sciences. In addition, A.G-A.M also got a stipend from DST/NRF–Centre in Indigenous Knowledge Systems of the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author’s Information

Aganze Gloire-Aimé Mushebenge is a PhD’s scholar in the Discipline of Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Health Sciences, Westville Campus, University of KwaZulu-Natal, P B X54001, Durban 4000, and South Africa.

List of Abbreviations

THP (Traditional Health Practitioner), TM (Traditional medicine), CT (Conventional Treatment), WHO (World Health Organization), HCP (Healthcare Professional), HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus, ATBs: Antibiotics.

References

- Leutscher PDC, Ramarokoto C-E, Hoffmann S, Jensen JS, Ramaniraka V, Randrianasolo B, Raharisolo C, Migliani R, Christensen NJCid: Coexistence of urogenital schistosomiasis and sexually transmitted infection in women and men living in an area where Schistosoma haematobium is endemic. 2008, 47, 775–782.

- Modjarrad K, Zulu I, Redden DT, Njobvu L, Freedman DO, Vermund SHJTAjotm, hygiene: Prevalence and predictors of intestinal helminth infections among human immunodeficiency virus type 1–infected adults in an urban African setting. 2005, 73, 777–782.

- Steinmann P, Keiser J, Bos R, Tanner M, Utzinger JJTLid: Schistosomiasis and water resources development: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimates of people at risk. 2006, 6, 411–425.

- WHO WHO: Schistosomiasis, Fact Sheet No 115. Available online: http://www who int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs115/en (accessed on 12 December 2018).

- Abaasa A, Asiki G, Ekii AO, Wanyenze J, Pala P, van Dam GJ, Corstjens PL, Hughes P, Ding S, Pantaleo GJWor: Effect of high-intensity versus low-intensity praziquantel treatment on HIV disease progression in HIV and Schistosoma mansoni co-infected patients: a randomised controlled trial. 2018, 3.

- De Clercq D, Vercruysse J, Kongs A, Verle P, Dompnier J, Faye P: Efficacy of artesunate and praziquantel in Schistosomahaematobium infected schoolchildren. J Acta Tropica 2002, 82, 61–66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva IMd, Thiengo R, Conceição MJ, Rey L, Lenzi HL, Pereira Filho E, Ribeiro PC: Therapeutic failure of praziquantel in the treatment of Schistosoma haematobium infection in Brazilians returning from Africa. J Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2005, 100, 445–449. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doenhoff MJ, Pica-Mattoccia L: Praziquantel for the treatment of schistosomiasis: its use for control in areas with endemic disease and prospects for drug resistance. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy 2006, 4, 199–210. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King CH, Muchiri EM, Mungai P, Ouma JH, Kadzo H, Magak P, Koech DK, hygiene: Randomized comparison of low-dose versus standard-dose praziquantel therapy in treatment of urinary tract morbidity due to Schistosoma haema tobium infection. J The American journal of tropical medicine 2002, 66, 725–730.

- Liang Y, Coles G, Doenhoff M: Detection of praziquantel resistance in schistosomes. J Tropical Medicine International Health 2000, 5, 72–72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cock I, Selesho M, Van Vuuren S: A review of the traditional use of southern African medicinal plants for the treatment of selected parasite infections affecting humans. J Journal of ethnopharmacology 2018.

- Bodeker G, Ong C-K: WHO global atlas of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine Available at: apps.who.int/bookorders/MDIbookPDF/Book/11500614.pdfAccessed , vol. 1: World Health Organization; 2005. 21 January.

- WHO.: Human papillomavirus and HPV Vaccines: Technical Information for Policy-makers Health Professionals. Available at: http://www. who. int/reproductive-health/publications/hpvvaccines_techinfo/hpvtechinfo_nocover. pdf 2002.

- Dalal S, Beunza JJ, Volmink J, Adebamowo C, Bajunirwe F, Njelekela M, Mozaffarian D, Fawzi W, Willett W, Adami H-O: Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: what we know now. J International journal of epidemiology 2011, 40, 885–901.

- Broekmans J, Migliori G, Rieder H, Lees J, Ruutu P, Loddenkemper R, Raviglione eMJERJ: European framework for tuberculosis control and elimination in countries with a low incidence: recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO), International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (IUATLD) and Royal Netherlands Tuberculosis Association (KNCV) Working Group. 2002, 19, 765–775.

- Hotez PJ, Molyneux DH, Fenwick A, Kumaresan J, Sachs SE, Sachs JD, Savioli LJNEJoM: Control of neglected tropical diseases. 2007, 357, 1018–1027.

- McGaw LJ, Van der Merwe D, Eloff JNJTVJ: In vitro anthelmintic, antibacterial and cytotoxic effects of extracts from plants used in South African ethnoveterinary medicine. 2007, 173, 366–372.

- Richter M: Traditional medicines and traditional healers in South Africa. Available from: http://www.tac.org.za/Documents/ResearchPapers/Traditional_Medicine_briefing.pdf. Accessed on 21 January 2019. J Treatment action campaign 2003, 17, 4–29. [Google Scholar]

- F̀reeman M, Motsei M: Planning health care in South Africa—is there a role for traditional healers? J Social Science Medicine 1992, 34, 1183–1190. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch N, Berry D: Differences in perceived risks and benefits of herbal, over-the-counter conventional, and prescribed conventional, medicines, and the implications of this for the safe and effective use of herbal products. J Complementary therapies in medicine 2007, 15, 84–91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayele AA, Tegegn HG, Haile KT, Belachew SA, Mersha AG, Erku DA: Complementary and alternative medicine use among elderly patients living with chronic diseases in a teaching hospital in Ethiopia. J Complementary therapies in medicine 2017, 35, 115–119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes GD, Aboyade OM, Beauclair R, Mbamalu ON, Puoane TR: Characterizing herbal medicine use for Noncommunicable diseases in urban South Africa. J Evidence-based complementary alternative medicine 2015, 2015.

- Sambo L: Health systems and primary health care in the African region. J The African Health Monitor 2011, 14, 2–3.

- Kupchunas WRJON: Personal health record: new opportunity for patient education. 2007, 26, 185–191.

- Scott D, Curtis B, Twumasi FOJH, place: Towards the creation of a health information system for cancer in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. 2002, 8, 237–249.

- Banhela N, Taylor M, Gift Zulu S, Sund Strabo L, Floerecke Kjetland E, Gunnar Gundersen S: Environmental factors influencing the distribution and prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium in school attenders of ILembe and uThungulu Health Districts, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Southern African Journal of Infectious Diseases 2017, 32, 132–137.

- Miles MB, Huberman M: Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. CA: Sage Publications Inc.; 1994.

- Pearson P, Steven A, Howe A, Sheikh A, Ashcroft D, Smith PJJHSRP: Learning about patient safety: organisational context and culture in the education of healthcare professionals. 2010, 15.

- Naing L, Winn T, Rusli BJAooS: Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. 2006, 1, 9–14.

- Lankford B, Pringle C, Dickens C, Lewis F, Chhotray V, Mander M, Goulden M, Nxele Z, Quayle LJRttNERCL, Norwich,, Anglia PUoE et al.: The impacts of ecosystem services and environmental governance on human well-being in the Pongola region, South Africa. 2010.

- Patton MQ: Qualitative evaluation and research methods: SAGE Publications, inc; 1990.

- Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh AJBmrm: The case study approach. 2011, 11, 100.

- Peltzer K, Ramlagan SJS: Cannabis use trends in South Africa. 2007, 13.

- Okoror TA, BeLue R, Zungu N, Adam AM, Airhihenbuwa CO: HIV Positive Women’s Perceptions of Stigma in Health Care Settings in Western Cape, South Africa. Health Care for Women International 2014, 35, 27–49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truter I, Steenkamp LJAJfPA, Sciences H: Anthelmintic drug dispensing in South Africa: An analysis of community pharmacy dispensing data. 2017, 2017(Supplement 1.1):106-117.

- Coulibaly J, Ouattara M, Barda B, Utzinger J, N’Goran E, Keiser JJTm, disease i: A rapid appraisal of factors influencing praziquantel treatment compliance in two communities endemic for schistosomiasis in Côte d’Ivoire. 2018, 3, 69.

- Ross AG, Olveda RM, Chy D, Olveda DU, Li Y, Harn DA, Gray DJ, McManus DP, Tallo V, Chau TNJTJoid: Can mass drug administration lead to the sustainable control of schistosomiasis? 2014, 211, 283–289.

- Krentel A, Fischer PU, Weil GJJPntd: A review of factors that influence individual compliance with mass drug administration for elimination of lymphatic filariasis. 2013, 7, e2447.

- Bah S, Diallo D, Dembélé S, Paulsen BS: Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used for the treatment of schistosomiasis in Niono District, Mali. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2006, 105, 387–399. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroyi AJEAoMP: Use of Ethnomedicinal Herbs to Treat and Manage Schistosomiasis in Zimbabwe: Past Trends and Future Directions. 2018.

- Simoben CV, Ntie-Kang F, Akone SH, Sippl W: Compounds from African Medicinal Plants with Activities against Protozoal Diseases: Schistosomiasis, Trypanosomiasis and Leishmaniasis. 2018.

- Schierenbeck I, Johansson P, Andersson LM, Krantz G, Ntaganira JJGph: Collaboration or renunciation? The role of traditional medicine in mental health care in Rwanda and Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. 2018, 13, 159–172.

- Van der Kooi R, Theobald SJAJoT, Complementary, Medicines A: Traditional medicine in late pregnancy and labour: perceptions of Kgaba remedies amongst the Tswana in South Africa. 2006, 3, 11–22.

- Mander M, Ntuli L, Diederichs N, Mavundla KJSAhr: Economics of the traditional medicine trade in South Africa: health care delivery. 2007, 2007, 189–196.

- Downs JA, Dupnik KM, van Dam GJ, Urassa M, Lutonja P, Kornelis D, Claudia J, Hoekstra P, Kanjala C, Isingo RJPntd: Effects of schistosomiasis on susceptibility to HIV-1 infection and HIV-1 viral load at HIV-1 seroconversion: A nested case-control study. 2017, 11, e0005968.

- Efraim L, Peck RN, Kalluvya SE, Kabangila R, Mazigo HD, Mpondo B, Bang H, Todd J, Fitzgerald DW, Downs JAJJoaids: Schistosomiasis and impaired response to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients in Tanzania. 2013, 62, e153.

- Stete K, Glass TR, van Dam GJ, Ntamatungiro A, Letang E, Claudia J, Corstjens PL, Ndege R, Mapesi H, Kern WVJPntd: Effect of schistosomiasis on the outcome of patients infected with HIV-1 starting antiretroviral therapy in rural Tanzania. 2018, 12, e0006844.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).