Key Points

GDBs, which provide a natural fit for network-based representation of biological information, are becoming increasingly popular as a way to manage and query heterogeneous data, and to provide new insights into data connections.

Knowledge graphs facilitate discovery of unexpected relationships across integrated multi-modal data that can lead to generation of new hypotheses in systems biology.

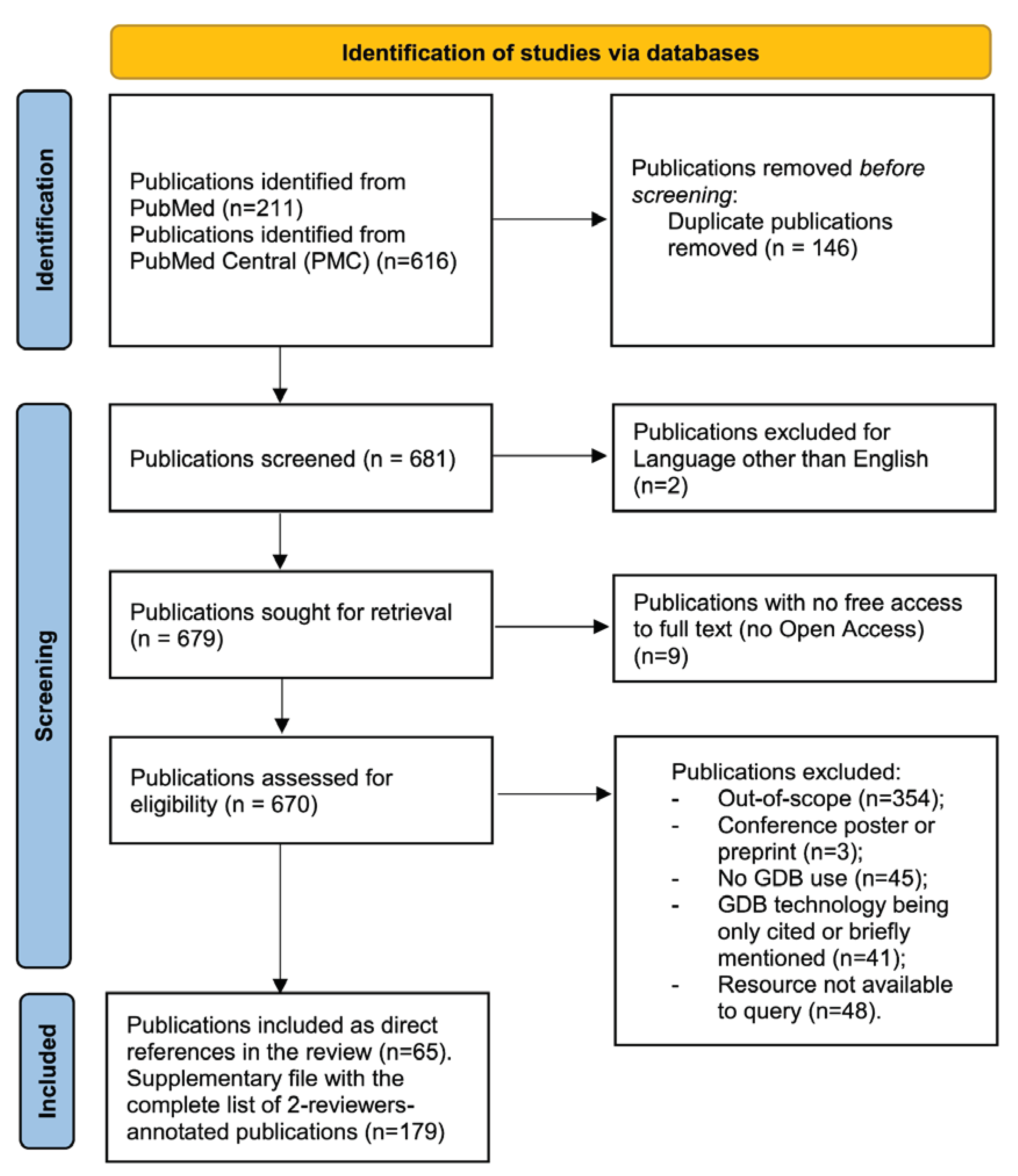

This review is based on 681 systematically identified GDB-related publications from the fields of biology and bioinformatics in PubMed and PMC repositories, further filtered down to 179 publications based on applicability in systems biology.

We outline the prospects of applying GDBs in systems biology with technologies such as Elasticsearch.

We highlight the ongoing efforts towards the development of unified GDB platforms for integration and exchange of heterogeneous biomedical data between multiple projects.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, new technologies and approaches emerged to extract large amounts of biological data, to interconnect data types across biological layers (proteins, metabolites, pathways, drugs, etc.) and to capture complex data relationships such as drug-biomarker-disease. Traditional approaches of storing biological data in a tabular format using relational databases present shortcomings when integrating biological content that is diverse, complex, and highly connected [

1]. Such data are important for systems biology [

2], where biological processes are studied by assembling and modelling the entirety of relevant knowledge. This requires efficient exploration of highly connected and heterogeneous data and their inter-relationships [

3].

GDBs have become popular for data integration, exploration, and visualisation in systems biology due to their potential to overcome the limitations of the relational approach [

1,

4,

5]. Graphs can naturally integrate and represent interactions between heterogeneous biological entities, allowing for efficient data traversal and exploration without the need to join multitudes of tables, a computationally expensive task [

1,

4]. GDBs are particularly efficient for querying highly interconnected data such as pathway data [

1,

6,

7], where execution performance for complex queries on gene-related paths and relationships between proteins is greatly improved using a GDB solution [

7].

Here, we provide a systematic review on the application of GDBs in systems biology. We focus on the problems addressed by the GDB methodology, on identified solutions, their advantages and limitations. We also discuss approaches towards harmonised KGs. Finally, we review current needs and new research questions in systems biology and related domains in the context of GDBs.

The review focuses on the top available GDB technologies (db-engines.com/en/ranking/graph+dbms) including but not limited to ArangoDB, Neo4j, OrientDB and Virtuoso. Initially, we automatically extracted a set of 681 publications on GDB applications in systems biology with a cut-off date of 31/03/2023. Each of the abstracts was then manually and independently annotated by two reviewers to assess relevance, applicability, documentation, and sustainability for further inclusion in this review. Finally, a list of 179 publications was considered for the review. Code developed for automatic publication metadata extraction and the manual annotations for each publication are available at github.com/ilyamazein/gdbreview. Details on the protocol including the inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the Methods section and corresponding supplementary files.

In the Background section, we briefly introduce relational and graph databases. We then present examples of GDB applicability with a focus on several topics in systems biology including pathway network analysis, biological ontologies and COVID-19 research in the Results section. There, we also discuss analytical methods enabled by GDBs in systems biology. In the Discussion, we address challenges as well as future prospects of applying GDB technologies in the biological domain and we conclude by outlining general advantages of GDB usage in systems biology and beyond.

2. Background

Relational Databases

Relational databases are well established and widely used for storing and querying biological data [

8]. They are founded on the concept of tables (or relations). A table represents a type of entity. The columns represent named attributes of the entity, and the rows represent instances of the entity itself. Each row of a table should be identified by a unique key (formed by one or more attributes, usually a unique ID attribute) called its primary key. A relational database may be queried using a query language, usually SQL (Structured Query Language).

Relational databases have many algorithms for the efficient retrieval of bulk structured data [

9]. However, they work best with data in a suitable, uniform structure, namely non-sparsely populated and well-defined tables. When presented with highly connected, sparsely populated or heterogeneous data, a relational database becomes less efficient. Specifically, the time and computational resources required to complete complex queries involving several joins among multiple tables increase considerably, thus making exploration of inter-connected data challenging [

1,

6].

Graph Databases

A GDB represents data and their inter-relationships using a graph, where an object or concept can be represented as a node and a relationship between two objects as an edge. Notably, GDBs are schema-optional: the representation of objects and relationships in the graph is not necessarily determined by a schema, does not require an initial normalisation step, and can be adapted without the need to restructure the database itself [

5,

10]. The two most frequent graph models are

Resource Description Framework (RDF) stores (w3.org/TR/rdf-concepts) and

labelled property graph (LPG) databases [

5].

The RDF model is a World Wide Web consortium (W3C) standard used to describe resources and relationships between them in the form of triples (w3.org/TR/2004/REC-rdf-concepts-20040210). A triple is composed of three elements: a subject, an object, and a predicate that describes the relationship between them (see Supplementary File 1A for an example). Each element of a triple is generally denoted using an Internationalised Resource Identifier (IRI), such as a URL. A set of triples forms an RDF graph, where resources are nodes and relationships are edges between these nodes. RDF stores are typically queried using SPARQL (w3.org/TR/rdf-sparql-query), which is a declarative language that aims to be similar to SQL.

The LPG model enriches the base graph structure with additional features: 1) nodes may have one or more labels that indicate their type(s); 2) edges must have one type; 3) both edges and nodes may have a set of properties defined as key-value pairs (see Supplementary File 1B for an example). Currently, one of the most popular LPG database management platforms in systems biology is Neo4j (neo4j.com), which has its own declarative language, Cypher.

3. Results

We manually annotated the initial set of 681 publications identified by queries in PubMed and PMC (see Methods). We then selected 179 publications as the most suitable for this review.

To further guide the reader through the analysed GDBs, we present four major topics that serve as a list of contents for our Results section, where we articulate our findings, highlighting stand-out methodologies, approaches, and resources. These topics are:

‘Pathway and network exploration’ - Applications of GDBs for the exploration of biomolecular pathways and networks, focusing on the Systems Biology Graphical Notation (SBGN) standard format [

11] and protein-protein interactions (PPIs);

‘Analytical approaches and tools enabled by GDBs’ - Methods and tools based on graph algorithms facilitated by the GDB integration. For the software-based publications, we considered tool availability and sustainability, online and public access.

‘Ontologies’ - Graph-based ontologies for biological data integration and transformation.

‘Systems biology use case: COVID-19 resources’ - KGs adapted or newly developed for the COVID-19 research.

Throughout the selected publications the use of LPGs seems to have supplanted the use of the more traditional RDF stores by approximately 7 times: among the papers mentioning at least one GDB that were selected to appear in this review, 87% mentioned an LPG, while only 12% mentioned an RDF store (1% mentioned both). From the GDB technology point of view, 82% of the selected publications reported the use of Neo4j, 8% of Virtuoso, 4% of AllegroGraph.

Each of the 179 selected publications has been carefully evaluated by at least two independent reviewers, the complete annotated list can be found in Supplementary

Table 1.

We followed the PRISMA 2020 approach for systematic review reporting (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses - PRISMA: prisma-statement.org) [

12]. The workflow for publication selection is shown in

Figure 1.

Pathway and Network Exploration

Process Description

The major standard formats to encode model information in systems biology are Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) [

13], SBGN [

11] and the Biological Pathway Exchange (BioPAX) [

14].

A frequently used graphical representation of process descriptions is the SBGN Process Description language (PD), which provides detailed information about biological processes [

15]. Process description based pathway databases include Reactome [

16,

17,

18], PANTHER [

19], Recon human metabolic network [

20], and others (

Table 1), in which interactions are presented in the form of molecular processes with connected regulatory proteins and complexes. Reactome (reactome.org) is a knowledge base of biomolecular pathways originally stored in a relational database format, but also available in the Neo4j GDB format [

6,

16,

17,

18]. The Neo4j Reactome shows greatly improved query efficiency when compared to the relational database [

6]. Recon2 is a genome-scale human metabolic network stored initially in SBML format with the visualisation built in CellDesigner on the MINERVA platform [

21]. The Neo4j version of Recon2 is available on GitHub (

Table 1) for exploration and querying [

22]. The StonPy tool [

23] made it possible to create Neo4j resources for the Atlas of Cancer Signalling Network (ACSN) and PANTHER pathway database, with new possibilities for analysis and comparison of Reactome, PANTHER and ACSN [

24]. The StonPy library also allowed building a Neo4j instance of the COVID-19 Disease Map [

23].

The main advantage of these GDB resources is the access provided to the corresponding pathway resources, allowing their network-based exploration and analysis. These resources store the data in their own formats but through the Neo4j environment the data and relationships between them can be searched, compared and used in the same analytical pipeline [

24].

Table 1.

Examples of process description based pathway resources available in Neo4j.

Table 1.

Examples of process description based pathway resources available in Neo4j.

| Database |

Content |

Accessible at |

Publications |

| Reactome |

Pathways in SBML- and SBGN-compatible format |

github.com/reactome/graph-core |

[6] |

| Plant Reactome |

Pathways in SBML- and SBGN-compatible format |

plantreactome.gramene.org/ |

[25] |

| Recon2 |

Metabolic pathways in SBML format |

github.com/ibalaur/MetabolicFramework |

[22] |

| PANTHER |

Pathways built in CellDesigner in SBML- and SBGN-compatible format |

Can be installed using StonPy (github.com/adrienrougny/stonpy) |

[23,24] |

| Atlas of Cancer Signalling Network |

Signalling network of cancer-related mechanisms built in CellDesigner in SBML- and SBGN-compatible format |

Can be installed using StonPy (github.com/adrienrougny/stonpy) |

[23,24] |

| COVID-19 Disease Map |

Signalling pathways in SBML- and SBGN-compatible format focused on the COVID-19 mechanisms |

c19dm-neo4j.lcsb.uni.lu/browser/ |

[26] |

| KEGG Pathway Database |

Signalling and metabolic pathways |

biochem4j.org/ |

[27] |

Protein-Protein Interactions

Information on PPIs is fundamental for understanding the functioning of biological systems [

28]. Well-established PPI DBs are broadly available (including [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]).

In a graph, proteins can be represented as nodes and PPIs as edges [

28,

37]. Due to their capabilities in facilitating network-based integration, querying and analysis, GDB approaches gained popularity for managing PPI data [

38]. Here, we outline the specific advantages of GDBs for management of PPI data focusing on i) heterogeneous data integration and exploration and ii) support for network-based analysis and modelling. We provide several prominent examples of well-established GDBs for each group. Other examples are provided in Supplementary File PPI.

PPI networks can be extremely large and complex, involving thousands of protein/complex interactions in interconnected pathways [

37]. For a proper understanding of biological systems, PPI data have to be integrated with other additional data types [

28,

39]. GDBs i) provide means for the integration of multimodal data types, such as gene expression, disease biomarkers, drug targets, pathway involvements, tissue and cell type association [

1,

40,

41,

42] and ii) allow for flexible and expressive queries on PPI networks [

43,

44,

45,

46]. Heterogeneous data integration within one single GDB enables comprehensive analysis and interpretation of biological phenomena by considering multiple layers of systems biology simultaneously [

47]. For example, the SmartGraph knowledge base integrates data on compounds and targets, focusing on drug-target interactions and PPI [

48]. The Network-based Drug Repurposing and exploration (NeDRex) platform integrates several biomedical data types (including genes, proteins, drugs and their targets) with their interrelationships and uses the inner PPI network as a central and major layer in network-based analysis aimed towards drug repurposing and disease module identification [

42]. IntAct is a comprehensive open-source curated resource that provides detailed information on PPIs and molecular complexes, facilitating the exploration of interaction networks in biological systems. The IntAct Neo4j component empowers researchers to perform advanced queries and visualisation of the integrated data, streamlining the computational analysis of intricate molecular networks [

43]. The Protein Data Bank in Europe Knowledge Base (PDBe-KB) [

44,

45,

46] is a well-established open-access repository on proteomic data (3D structures, functional and biophysical annotations). A hybrid relational-GDB approach is implemented: an Oracle component that is more efficient on simple queries and a Neo4j solution that permits executing more sophisticated queries and analysis [

45].

GDBs are also suitable for network-based analysis. The underlying graph representation of the content in GDBs facilitates implementation of graph-based algorithms such as i) path finding, identifying the connections or pathways between different molecular entities within complex networks, ii) similarity functions, comparing and analysing molecular entities based on their properties and connections within a network, and iii) community detection, identifying densely connected groups or clusters within a network. Such graph-based algorithms provide means for detection of hidden patterns in interconnected data as well as for prediction of novel associations or interactions between entities in biological networks [

40,

42,

49,

50]. For example, SmartGraph [

48] used network-based inference to perform

in-silico prediction of novel relationships between compounds and targets, exploring the complex landscape of drug-target and target-target interactions. In [

50], a combined approach of a human PPI network (integrating over 200.000.000 interactions involving more than 20000 proteins) and regulatory network was developed to explore pathologic features of neurodegeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The Clinical Knowledge Graph (CKG) is an open-source platform that integrates data on various biomedical concepts (e.g. proteins, tissues, peptides, drugs, biological function, cellular components) and their inter-relationships from clinical experimental studies, public databases, and specialised literature. It focuses on proteomics analysis and interpretation via incorporated statistical algorithms and machine learning (ML). CKG uses a Neo4j GDB to manage the knowledge base composed of millions of nodes and inter-relationships and has developed a library for optimised implementation of graph-based algorithms including path finding, similarity functions, and community detection [

49].

Ontologies

An ontology is a set of concepts and relationships between these concepts, that describes a domain of knowledge. Ontologies play a role in a wide variety of tasks in bioinformatics, allowing researchers to define and share a common conceptualisation of a domain in a formal way. Numerous ontologies have been defined to describe different subdomains of biology and in particular systems biology [

14,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64].

Ontologies and GDBs

RDF and ontologies are tightly linked technologies in the realm of the semantic web. RDF enables a linked data paradigm [

65], used in ontologies to create a semantic layer that enables formal reasoning and knowledge discovery. Most ontologies available online are represented and exchanged using the Web Ontology Language (OWL) (w3.org/TR/owl-guide), which is built on top of the RDF format. Ontologies can thus be represented as RDF triples and queried using SPARQL (w3.org/TR/rdf-sparql-query). Some RDF stores also include reasoning capabilities supporting direct OWL-based inferences (e.g. AllegroGraph, Virtuoso). Most of the mentioned systems biology ontologies are stored using RDF stores, but some also use Neo4j as their endpoint (see

Table 2). Tools such as Owl2Neo4j [

66] may be used to store an OWL ontology in a Neo4j database automatically.

Ontologies for Data Integration in GDBs

Ontologies may be used as backbones to integrate data from different sources into one database. In the context of GDBs, this may be facilitated by the tight integration of ontologies into the RDF framework. The (semi-)automatic integration process generally relies on the transformation of heterogeneous data into uniform ontology-backed RDF triples using rules (e.g. the Knowledge Base of Biomedicine (KaBOB) [

67]), probabilistic models (e.g. GORouter [

72]), or shared guidelines (e.g. Bio2RDF [

73]). The integration process may result in unique RDF stores (KaBOB, GORouter) or in a series of individual although homogeneous stores that can be queried using federated SPARQL queries (Bio2RDF) [

74].

Ontology-Based GDB Queries

Data can be retrieved from GDBs using database-specific query languages. While all RDF stores may be queried using SPARQL, there is no unique standard language for LPG databases (see Table S2.2 in Supplementary File 2). A means to overcome this heterogeneity in query languages is to build systems that allow users to query databases in natural language. In some systems the transformation process is knowledge-based and guided by the ontology that backs the GDB [

75]. For example, the OntoNLQA framework can be used to automatically answer natural language questions based on parasite immunology data stored in an RDF store backed by an ontology [

76]. Ontologies may also be used to check the correctness of user input queries in the context of GDBs [

77].

Systems Biology Use-Case: COVID-19 Resources

During the COVID-19 pandemic, GDB approaches have contributed to the development of i) molecular pathways [

43], ii) clinical trials and drug repurposing [

78,

79,

80,

81], iii) ontology resources related to COVID-19 [

82,

83,

84], and iv) application of graph-based methods for the exploration of COVID-19 mechanisms, comorbidities, and risk factors [

84,

85,

86] (see Supplementary File COVID-19). A classification of the COVID-19 KGs using GDBs based on their main application domain is provided in [

87].

During the pandemic, many efforts focused on integrating heterogeneous COVID-19 data to facilitate data exploration and visualisation of molecular pathways and disease mechanisms. KGEV is a web framework for the construction, exploration, and visualisation of COVID-19 KGs [

84], which was used to develop a COVID-19 KG by integrating data from the CORD-19 dataset [

88]. Semantic relationships are enriched by integrating knowledge from several public biomedical repositories and ontologies [

30,

70,

71,

89,

90,

91,

92]. The KGEV framework uses Neo4j to store and query the data and can be extended to other diseases. The gcCov is a coronavirus genotype-phenotype KG based on a semantic web framework (employing RDF and Neo4j) and open linked data. This database provides a resource for structural and sequence similarities among coronaviruses and may therefore aid in the identification of cross-neutralising antibodies that bind to multiple CoV antigens, which may be relevant for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infections [

86].

Data exploration and visualisation of KGs are also employed in several comprehensive COVID-19 community projects, including CovidGraph (healthecco.org) [

83] and COVID-19-Net (github.com/covid-19-net/covid-19-community). CovidGraph integrates COVID-related data such as publications and patents, clinical trial data, biomedical data, and computational systems biology models into a Neo4j GDB to provide a single point of access to these diverse data sources. The COVID-19-Net project uses a Neo4j approach to integrate heterogeneous biological data types (both health and pathogen-related) with environmental characteristics to facilitate exploration of COVID-19 mechanisms by looking at interdependencies among host-pathogen-environment systems. The IntAct Coronavirus interactome dataset integrates protein-protein and RNA-protein interactions involving SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV and can be explored in the Neo4j version of IntAct [

43]. KG-COVID-19 (Neo4j-based) [

80] and COVID-19 KG (Virtuoso-based) [

82] are comprehensive knowledge bases for ML applications and downstream analysis in COVID-19 drug repurposing. KG-COVID-19 integrates primarily data on drug targets, protein interactions, protein functional annotations, and disease ontologies [

80]. COVID-19 Knowledge Graph is developed using text mining and relevant curated biological databases [

82].

Among the COVID-19 GDBs, many have been used as an approach to explore candidates for drug repurposing using computational modelling approaches. In this context, a novel method using neural networks (involving several graph completion algorithms) and literature curation approaches was developed for identification of candidates for COVID-19 drug repurposing. The work uses Neo4j to store semantic relationships among the data (e.g. relationships on inhibition, interaction, association, causality between drugs and other biological concepts) and to help with navigation and visualisation of the integrated resources. The Neo4j functionality was also used in a computational analytical step to evaluate the plausibility of several highly-ranked drug candidates returned by the graph-based completion component [

78]. Identification of possible drugs for treatment can also be achieved by a graph neighbourhood search, as performed on a COVID-19 KG constructed using the KGEV framework [

84]. In addition, a shortest path approach identified similarities in pathways (alterations) in obese people and COVID-19 patients. In COVID-19 pharmacology research, a workflow for semiautomated integration of multi-modal data was used to develop the Neo4COVID19 resource, which describes a network of host-host, host-pathogen, and drug-target interactions for COVID-19 [

81].

4. Discussion

Challenges and Lessons Learned

GDBs, and in particular LPGs, are a relatively new technology compared to RDBs. An effort to use these tools efficiently is ongoing and new techniques are constantly developed. Moreover, the LPGs ecosystem is not completely mature, and still undergoes rapid changes. LGPs notably lack a standardised query language (similar to SQL for relational databases or SPARQL for RDF), despite progress on openCypher (opencypher.org) and ISO’s Graph Query Language (gqlstandards.org). In addition, while some specific GDBs, such as Neo4j or Virtuoso, are offered as free and open source versions, they lack important features such as access control. This limits the free use of GDBs for integrating sensitive data, such as electronic medical records.

The term “integrated resources” refers to GDBs that assimilate data from multiple sources. Integrated resources facilitate i) discovery of new connections across data from multiple sources (e.g. Pathway and network exploration) and ii) semantic enrichment by combining data and ontologies (see Ontologies). They offer a single query language and access to a platform combining multiple databases.

A large portion of reviewed GDBs for systems biology are integrated resources (93 integrated for 3 primary), which suggests that RDBs are still the main technology for primary data sources. This could be explained by the fact that i) GDBs are still a new technology compared to RDBs, ii) they might be difficult to adopt, and iii) they are less efficient than RDBs for some types of queries (e.g. complex queries with aggregates) or for structured data that are not densely interconnected [

93].

GDBs are adequate for integrating data: they are schema-optional, they are efficient for visualising and retrieving highly connected data, and they are compatible with ontologies. However, GDBs still face challenges inherent to integration of heterogeneous data types originating from multiple resources and the sustainability of these integrated resources [

94,

95,

96]. This latter issue is particularly significant, as among the 93 publications that report accessible resources for data integration, only 20 are regularly updated (see Supplementary File Integrated Resources). These difficulties can be addressed with standardised approaches (see

Efforts towards a uniform development of knowledge bases) or with the use of specific GDB technologies, such as federated queries [

97].

Perspectives

GDBs are suitable for systems biology and will support future automated model generation and machine learning tasks. However, they need to be standardised, documented and maintained to unlock their potential. Therefore, key points when planning a GDB application are i) building on established approaches that aim at standardising KG creation, ii) following the principles of Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability and Reusability (FAIR) [

98] for the data included and the principles of Transparency, Responsibility, User focus, Sustainability and Technology (TRUST) [

99] for the KG itself, and iii) automating the GDB maintenance.

Elasticsearch and GDBs

Elasticsearch (elastic.co) is a distributed open-source search and analysis platform that can process large-scale data of various types, including text, numerical, structured and unstructured data. Elasticsearch is based on indexing, where an index is a collection of documents related to each other. It uses a data structure called an inverted index that connects every unique word appearing in any document to all the documents of the collection it appears in, allowing fast full-text searches. When presented with a new document, Elasticsearch stores it and re-builds an inverted index.

Elasticsearch and GDB technologies have been recently combined, for example, creating optimised systems for semantic indexing and classification of biomedical literature [

106] or knowledge bases that enable exploration of drug molecular mechanisms for precision medicine [

107]. In systems biology, the Alliance of Genome Resources, which integrates data from the major model organisms databases, uses Neo4j as a database and the Elasticsearch technology as a search service [

108]. To this end, the Alliance harmonised data models of the different sources and curation workflows. As a result, all sources can be integrated into a single database with a unified data model, which facilitates queries spanning over several organisms and enables cross-organism investigation.

5. Conclusions

We observe a rapid increase in the use of GDBs: while in 2012, only 17 PubMed publications cited any of the GDB approaches mentioned in this review, there were more than 190 in 2022. In systems biology, GDBs have been proven efficient for storing data that are naturally organised in the form of graphs, such as pathways and molecular networks. For this type of data, where exploration comes to follow nodes along paths, GDBs turn out to be more efficient than relational databases, since they are less computationally expensive. The GDB approach also offers significant additional advantages (schema-optional, better visualisation, embedded graph algorithms) that all together make it a great candidate for data integration, exploration and analysis in systems biology. For this reason, we observe a growing number of publicly available GDB-based KGs that integrate data from multiple sources and often constitute substantial knowledge bases on more generic (e.g. human cancer) or more focused topics (e.g. COVID-19) of systems biology. The construction of such KGs often relies on non-sustainable workflows that fetch and merge data from the desired sources into one GDB, sometimes backed by ontologies that help structure the used data model. While these KGs offer readily and efficiently accessible data on specific systems biology topics, the way they are built and their growing number brings consequential issues, such as their redundancy, heterogeneity and sustainability. These issues may be solved in the future by standardising the use of common workflows and data models for building KGs, and by organising their construction and maintenance around durable communities or consortia.

6. Methods

In this systematic review, we performed the following steps. First, we scrutinised the use of GDB technologies as reported in the DB-Engines resource (db-engines.com, reference date 09/2023). We then proceeded with the automatic retrieval of GDB-related publications in systems biology from the PubMed and PMC repositories. Each entry from this list of publications was manually annotated by two reviewers. We focused on the following areas: networks, pathways, ontologies, methodological approaches and softwares, and we discussed selected examples from each of these groups. In addition, we considered the following criteria: i) the use of a specific GDB technology (e.g. AllegroGraph, ArangoDB, GraphDB, Neo4j, OrientDB, Virtuoso), and ii) the applicability in systems biology, such as disease-specific (e.g. breast cancer, COVID-19), domain-specific (e.g. rare diseases, neurodegenerative disorders), or broader areas (e.g. PPI, molecular maps). The list itself was refined for further consideration in the current review. We performed further in depth review for the refined list of publications. Priority for selection was given to the publications presenting projects that are actively maintained and are potentially likely to be reused in systems biology. Additional supporting examples are provided in specific tables. Details on the methods of this systematic review are provided in Supplementary File 2. We provide the annotated list of publications with corresponding PubMed and DOI urls, at: github.com/ilyamazein/gdbreview.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: IM, AR, AM, RH, LG, LM, JW, MO, RS, VS, LJJ, DW, IB. Methodology: IM, AR, AM, RH, LG, LM, JW, LJJ, DW, IB. Investigation: IM, AR, AM, RH, LG, LM, JW, IB. Formal analysis: IM, IB. Python scripts: IM, AR. Initial draft preparation, IM. Review and editing: all authors. Project coordination: IB. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Availability

All relevant data are provided within this publication and supplementary files. An updated version of the annotated tables with all relevant publications is available via github.com/ilyamazein/gdbreview.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to thank the Pre-Publication Check (PPC) team at LCSB-UNILU for the comments and assistance with ensuring the FAIRness and reproducibility of this work.

Competing interests

RS is a co-founder and a shareholder of MEGENO S.A. and ITTM S.A. VS is a co-founder and a shareholder of ITTM S.A. LJJ is a founder, owner and scientific advisor of Intomics A/S. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Lysenko, A.; Roznovăţ, I.A.; Saqi, M.; et al. Representing and querying disease networks using graph databases. BioData Min. 2016, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, H. Systems biology: a brief overview. Science 2002, 295, 1662–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graw, S.; Chappell, K.; Washam, C.L.; et al. Multi-omics data integration considerations and study design for biological systems and disease. Mol. Omics 2021, 17, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Have, C.T.; Jensen, L.J. Are graph databases ready for bioinformatics? Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2013, 29, 3107–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timón-Reina, S.; Rincón, M.; Martínez-Tomás, R. An overview of graph databases and their applications in the biomedical domain. Database J. Biol. Databases Curation 2021, 2021, baab026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabregat, A.; Korninger, F.; Viteri, G.; et al. Reactome graph database: Efficient access to complex pathway data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1005968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.-H.; Kim, S.-K.; Kim, S.-Y. Use of Graph Database for the Integration of Heterogeneous Biological Data. Genomics Inform. 2017, 15, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biological database modeling. 2008.

- Kriegel, A.; Trukhnov, B.M. SQL bible: explore the new SQL standard ; write more effective queries or develop code ; work with Oracle, IBM DB2, and SQL Server. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, N.; Green, A.; Guagliardo, P.; et al. Cypher: An Evolving Query Language for Property Graphs. Proc. 2018 Int. Conf. Manag. Data 2018, 1433–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Novère, N.; Hucka, M.; Mi, H.; et al. The Systems Biology Graphical Notation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hucka, M.; Finney, A.; Sauro, H.M.; et al. The systems biology markup language (SBML): a medium for representation and exchange of biochemical network models. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2003, 19, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, E.; Cary, M.P.; Paley, S.; et al. The BioPAX community standard for pathway data sharing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougny, A.; Touré, V.; Moodie, S.; et al. Systems Biology Graphical Notation: Process Description language Level 1 Version 2. 0. J. Integr. Bioinforma. 2019, 16, 20190022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabregat, A.; Sidiropoulos, K.; Viteri, G.; et al. Reactome pathway analysis: a high-performance in-memory approach. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jassal, B.; Matthews, L.; Viteri, G.; et al. The reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D498–D503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, M.; Jassal, B.; Stephan, R.; et al. The reactome pathway knowledgebase 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D687–D692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, H.; Muruganujan, A.; Ebert, D.; et al. PANTHER version 14, more genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D419–D426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, I.; Swainston, N.; Fleming, R.M.T.; et al. A community-driven global reconstruction of human metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noronha, A.; Daníelsdóttir, A.D.; Gawron, P.; et al. ReconMap: an interactive visualization of human metabolism. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2017, 33, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaur, I.; Mazein, A.; Saqi, M.; et al. Recon2Neo4j: applying graph database technologies for managing comprehensive genome-scale networks. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2017, 33, 1096–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougny, A.; Balaur, I.; Luna, A.; et al. StonPy: a tool to parse and query collections of SBGN maps in a graph database. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2023, 39, btad100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rougny, A.; Touré, V.; Albanese, J.; et al. SBGN Bricks Ontology as a tool to describe recurring concepts in molecular networks. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbab049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naithani, S.; Gupta, P.; Preece, J.; et al. Plant Reactome: a knowledgebase and resource for comparative pathway analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D1093–D1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazein, A.; Acencio, M.L.; Balaur, I.; et al. A guide for developing comprehensive systems biology maps of disease mechanisms: planning, construction and maintenance. Front. Bioinforma. 2023, 3, 1197310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swainston, N.; Batista-Navarro, R.; Carbonell, P.; et al. biochem4j: Integrated and extensible biochemical knowledge through graph databases. PloS One 2017, 12, e0179130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonawane, A.R.; Weiss, S.T.; Glass, K.; et al. Network Medicine in the Age of Biomedical Big Data. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermjakob, H.; Montecchi-Palazzi, L.; Lewington, C.; et al. IntAct: an open source molecular interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D452–D455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; et al. STRING v11, protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshava Prasad, T.S.; Goel, R.; Kandasamy, K.; et al. Human Protein Reference Database--2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D767–D772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oughtred, R.; Rust, J.; Chang, C.; et al. The BioGRID database: A comprehensive biomedical resource of curated protein, genetic, and chemical interactions. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 2021, 30, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herwig, R.; Hardt, C.; Lienhard, M.; et al. Analyzing and interpreting genome data at the network level with ConsensusPathDB. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1889–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licata, L.; Briganti, L.; Peluso, D.; et al. MINT, the molecular interaction database: 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D857–D861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlyar, M.; Rossos, A.E.M.; Jurisica, I. Prediction of Protein-Protein Interactions. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 2017, 60, 8.2.1–8.2.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttlin, E.L.; Ting, L.; Bruckner, R.J.; et al. The BioPlex Network: A Systematic Exploration of the Human Interactome. Cell 2015, 162, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Ho, A.; Huang, H.-Y.; et al. Dissecting the human protein-protein interaction network via phylogenetic decomposition. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, V.; Bodein, A.; Scott-Boyer, M.-P.; et al. Overview of methods for characterization and visualization of a protein-protein interaction network in a multi-omics integration context. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 962799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Benner, M.J.; Hancock, R.E.W. NetworkAnalyst--integrative approaches for protein-protein interaction network analysis and visual exploration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W167–W174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelstein, D.S.; Zietz, M.; Rubinetti, V.; et al. Hetnet connectivity search provides rapid insights into how biomedical entities are related. GigaScience 2022, 12, giad047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.H.; Soman, K.; Akbas, R.E.; et al. The scalable precision medicine open knowledge engine (SPOKE): a massive knowledge graph of biomedical information. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2023, 39, btad080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadegh, S.; Skelton, J.; Anastasi, E.; et al. Network medicine for disease module identification and drug repurposing with the NeDRex platform. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Toro, N.; Shrivastava, A.; Ragueneau, E.; et al. The IntAct database: efficient access to fine-grained molecular interaction data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D648–D653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.; Váradi, M.; Nadzirin, N.; et al. PDBe aggregated API: programmatic access to an integrative knowledge graph of molecular structure data. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2021, 37, 3950–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Anyango, S.; Appasamy, S.D.; et al. PDBe and PDBe-KB: Providing high-quality, up-to-date and integrated resources of macromolecular structures to support basic and applied research and education. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 2022, 31, e4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDBe-KB consortium. PDBe-KB: collaboratively defining the biological context of structural data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D534–D542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Gil, A.; Fernández-Breis, J.T.; Boeker, M. Analysis and visualization of disease courses in a semantically-enabled cancer registry. J. Biomed. Semant. 2017, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoránszky-Kőhalmi, G.; Sheils, T.; Oprea, T.I. SmartGraph: a network pharmacology investigation platform. J. Cheminformatics 2020, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Colaço, A.R.; Nielsen, A.B.; et al. A knowledge graph to interpret clinical proteomics data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Re, D.B.; Le Verche, V.; et al. Systematic elucidation of neuron-astrocyte interaction in models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using multi-modal integrated bioinformatics workflow. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bono, B.; Gillespie, T.; Surles-Zeigler, M.C.; et al. Representing Normal and Abnormal Physiology as Routes of Flow in ApiNATOMY. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 795303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Huang, X.; Xie, C.; et al. GREG-studying transcriptional regulation using integrative graph databases. Database J. Biol. Databases Curation 2020, 2020, baz162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerzner, E.; Lex, A.; Sigulinsky, C.L.; et al. Graffinity: Visualizing Connectivity in Large Graphs. Comput. Graph. Forum J. Eur. Assoc. Comput. Graph. 2017, 36, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, K.; Meyyappan, T. Compact in-memory representation of large graph databases for efficient mining of maximal frequent sub graphs. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2021, 33, e5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambusch, F.; Waltemath, D.; Wolkenhauer, O.; et al. Identifying frequent patterns in biochemical reaction networks: a workflow. Database J. Biol. Databases Curation 2018, 2018, bay051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Mendoza, L.; Marrero-Ponce, Y.; Beltran, J.A.; et al. Graph-based data integration from bioactive peptide databases of pharmaceutical interest: toward an organized collection enabling visual network analysis. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2019, 35, 4739–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, A.; Fiannaca, A.; La Paglia, L.; et al. BioGraph: a web application and a graph database for querying and analyzing bioinformatics resources. BMC Syst. Biol. 2018, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtot, M.; Juty, N.; Knüpfer, C.; et al. Controlled vocabularies and semantics in systems biology. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011, 7, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauro, H.M.; Bergmann, F.T. Standards and ontologies in computational systems biology. Essays Biochem. 2008, 45, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, T.H.; Tripathy, S.J.; Sy, M.F.; et al. The Neuron Phenotype Ontology: A FAIR Approach to Proposing and Classifying Neuronal Types. Neuroinformatics 2022, 20, 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D330–D338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schriml, L.M.; Arze, C.; Nadendla, S.; et al. Disease Ontology: a backbone for disease semantic integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D940–D946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unni, D.R.; Moxon, S.A.T.; Bada, M.; et al. Biolink Model: A universal schema for knowledge graphs in clinical, biomedical, and translational science. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2022, 15, 1848–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Brun, C.; Remy, E.; et al. GOToolBox: functional analysis of gene datasets based on Gene Ontology. Genome Biol. 2004, 5, R101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizer, C.; Heath, T.; Idehen, K.; et al. Linked data on the web (LDOW2008). Proc. 17th Int. Conf. World Wide Web 2008, 1265–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekschas, F.; Gehlenborg, N. SATORI: a system for ontology-guided visual exploration of biomedical data repositories. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2018, 34, 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, K.M.; Bada, M.; Baumgartner, W.A.; et al. KaBOB: ontology-based semantic integration of biomedical databases. BMC Bioinformatics 2015, 16, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natale, D.A.; Arighi, C.N.; Blake, J.A.; et al. Protein Ontology (PRO): enhancing and scaling up the representation of protein entities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D339–D346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Huang, H.; Ross, K.E.; et al. Protein ontology on the semantic web for knowledge discovery. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shefchek, K.A.; Harris, N.L.; Gargano, M.; et al. The Monarch Initiative in 2019, an integrative data and analytic platform connecting phenotypes to genotypes across species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D704–D715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhler, S.; Carmody, L.; Vasilevsky, N.; et al. Expansion of the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) knowledge base and resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D1018–D1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Shi, Y.; Lu, Q.; et al. GORouter: an RDF model for providing semantic query and inference services for Gene Ontology and its associations. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9 Suppl 1, S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleau, F.; Nolin, M.-A.; Tourigny, N.; et al. Bio2RDF: towards a mashup to build bioinformatics knowledge systems. J. Biomed. Inform. 2008, 41, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.-H.; Frost, H.R.; Marshall, M.S.; et al. A journey to Semantic Web query federation in the life sciences. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10 Suppl 10, S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiaee, A.H.; Doshi, P.; Minning, T.; et al. From Questions to Effective Answers: On the Utility of Knowledge-Driven Querying Systems for Life Sciences Data. Data Integr. Life Sci. 2013, 7970, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiaee, A.H.; Minning, T.; Doshi, P.; et al. A framework for ontology-based question answering with application to parasite immunology. J. Biomed. Semant. 2015, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgonek, J.; Hurt, T.; Michlíková, V.; et al. Advanced SPARQL querying in small molecule databases. J. Cheminformatics 2016, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Hristovski, D.; Schutte, D.; et al. Drug repurposing for COVID-19 via knowledge graph completion. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 115, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleem, J.; Granet, R.; Ramakrishnan, S.; et al. Knowledge Graph-Based Approaches to Drug Repurposing for COVID-19. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 4058–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, J.T.; Unni, D.; Callahan, T.J.; et al. KG-COVID-19, A Framework to Produce Customized Knowledge Graphs for COVID-19 Response. Patterns N. Y. N 2021, 2, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoránszky-Kőhalmi, G.; Siramshetty, V.B.; Kumar, P.; et al. A Workflow of Integrated Resources to Catalyze Network Pharmacology Driven COVID-19 Research. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ross, K.E.; Gavali, S.; et al. COVID-19 Knowledge Graph from semantic integration of biomedical literature and databases. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2021, 37, 4597–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gütebier, L.; Bleimehl, T.; Henkel, R.; et al. CovidGraph: a graph to fight COVID-19. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2022, 38, 4843–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xu, D.; Lee, R.; et al. Expediting knowledge acquisition by a web framework for Knowledge Graph Exploration and Visualization (KGEV): case studies on COVID-19 and Human Phenotype Ontology. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo-Fernández, D.; Baksi, S.; Schultz, B.; et al. COVID-19 Knowledge Graph: a computable, multi-modal, cause-and-effect knowledge model of COVID-19 pathophysiology. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2021, 37, 1332–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Fan, G.; Shen, Z.; et al. gcCov: Linked open data for global coronavirus studies. mLife 2022, 1, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Nardi, C.; Oberije, C.; et al. Knowledge Graphs for COVID-19, An Exploratory Review of the Current Landscape. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Lo, K.; Chandrasekhar, Y.; et al. CORD-19, The Covid-19 Open Research Dataset. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10706v4. [Google Scholar]

- Freshour, S.L.; Kiwala, S.; Cotto, K.C.; et al. Integration of the Drug-Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb 4. 0) with open crowdsource efforts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1144–D1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero, J.; Ramírez-Anguita, J.M.; Saüch-Pitarch, J.; et al. The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D845–D855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D523–D531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gene Ontology Consortium; Aleksander, S.A.; Balhoff, J; et al. The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224, iyad031. [Google Scholar]

- Kotiranta, P.; Junkkari, M.; Nummenmaa, J. Performance of Graph and Relational Databases in Complex Queries. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.E.; Gabbard, J.L.; Shukla, M.; et al. Data integration for dynamic and sustainable systems biology resources: challenges and lessons learned. Chem. Biodivers. 2010, 7, 1124–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapatas, V.; Stefanidakis, M.; Jimenez, R.C.; et al. Data integration in biological research: an overview. J. Biol. Res. Thessalon. Greece 2015, 22, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thessen, A.E.; Bogdan, P.; Patterson, D.J.; et al. From Reductionism to Reintegration: Solving society’s most pressing problems requires building bridges between data types across the life sciences. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasnain, A.; Mehmood, Q.; Sana EZainab, S.; et al. BioFed: federated query processing over life sciences linked open data. J. Biomed. Semant. 2017, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.J.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Crabtree, J.; Dillo, I.; et al. The TRUST Principles for digital repositories. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touré, V.; Le Novère, N.; Waltemath, D.; et al. Quick tips for creating effective and impactful biological pathways using the Systems Biology Graphical Notation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1005740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türei, D.; Korcsmáros, T.; Saez-Rodriguez, J. OmniPath: guidelines and gateway for literature-curated signaling pathway resources. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 966–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.; Schreiber, F.; Moodie, S.; et al. Systems Biology Graphical Notation: Activity Flow language Level 1 Version 1. 2. J. Integr. Bioinforma. 2015, 12, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, F.; Turei, D.; Gabor, A.; et al. Bringing data from curated pathway resources to Cytoscape with OmniPath. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2020, 36, 2632–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodchenkov, I.; Babur, O.; Luna, A.; et al. Pathway Commons 2019 Update: integration, analysis and exploration of pathway data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D489–D497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerami, E.G.; Gross, B.E.; Demir, E.; et al. Pathway Commons, a web resource for biological pathway data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D685–D690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura Bedmar, I.; Martínez, P.; Carruana Martín, A. Search and Graph Database Technologies for Biomedical Semantic Indexing: Experimental Analysis. JMIR Med. Inform. 2017, 5, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Cai, W.; Xi, C.; et al. AIMedGraph: a comprehensive multi-relational knowledge graph for precision medicine. Database J. Biol. Databases Curation 2023, 2023, baad006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance of Genome Resources Consortium. Alliance of Genome Resources Portal: unified model organism research platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D650–D658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himmelstein, D.S.; Lizee, A.; Hessler, C.; et al. Systematic integration of biomedical knowledge prioritizes drugs for repurposing. eLife 2017, 6, e26726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biomedical Data Translator Consortium. Toward A Universal Biomedical Data Translator. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2019, 12, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannestad, L.M.; Dančík, V.; Godden, M.; et al. Knowledge Beacons: Web services for data harvesting of distributed biomedical knowledge. PloS One 2021, 16, e0231916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, E.C.; Glen, A.K.; Kvarfordt, L.G.; et al. RTX-KG2, a system for building a semantically standardized knowledge graph for translational biomedicine. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, 23, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, D.; Gaulton, A.; Bento, A.P.; et al. ChEMBL: towards direct deposition of bioassay data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D930–D940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wishart, D.S.; Knox, C.; Guo, A.C.; et al. DrugBank: a comprehensive resource for in silico drug discovery and exploration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D668–D672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobentanzer, S.; Aloy, P.; Baumbach, J.; et al. Democratizing knowledge representation with BioCypher. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1056–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, J.D.; Whetzel, P.L.; Anderson, K.; et al. The Biomedical Resource Ontology (BRO) to enable resource discovery in clinical and translational research. J. Biomed. Inform. 2011, 44, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio-Hernandez, I.; Schwartzentruber, J.; Shrivastava, A.; et al. Network expansion of genetic associations defines a pleiotropy map of human cell biology. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Biographical Notes

Ilya Mazein is a PhD Student in the MeDaX group at the Medical Informatics department of the University Medicine Greifswald (UMG), working with biomedical data, machine learning, and graph databases.

Adrien Rougny is a researcher at the Luxembourg Centre for Systems Biomedicine (LCSB), University of Luxembourg (UNILU), working on the representation, modelling, and analysis of molecular networks.

Alexander Mazein is a researcher at LCSB, UNILU, working on a comprehensive representation of disease mechanisms, reusability in network biology, and data interpretation in translational medicine projects.

Ron Henkel is a researcher affiliated with the Medical Informatics department at UMG. His academic journey has its roots in databases and information systems, combined with a keen interest in systems biology.

Lea Gütebier is a PhD student at the Medical Informatics department at UMG, working on biomedical data integration, graph databases, and graph-based similarity algorithms.

Lea Michaelis is a PhD student at the MeDaX junior research group at the Medical Informatics department at UMG, working on data quality and similarity measures for medical data.

Marek Ostaszewski is a scientist and a project manager at LCSB, UNILU, working on IT applied to knowledge management in systems biomedicine, in particular in Parkinson’s disease, including clinical research.

Reinhard Schneider is the Head of the Bioinformatics Core facility, LCSB at UNILU. His team develops solutions for efficient data integration, interpretation, and exchange between the experimental, theoretical, and medical domains.

Venkata Satagopam is a Senior Research Scientist and Deputy Head of the Bioinformatics Core facility, LCSB at UNILU, working on different multi-disciplinary research projects that involve large data integration and knowledge management, clinical and translational data curation, harmonisation, integration, and analysis.

Lars Juhl Jensen is a professor at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Centre for Protein Research at the University of Copenhagen, working on literature mining, integration of large-scale experimental datasets, and analysis of biological interaction networks.

Dagmar Waltemath is a professor of Medical Informatics at UMG, working on semantic data integration, data standardisation in computational biology, graph databases, information retrieval, and research data management in the context of the FAIR data principles and biomedical sciences.

Judith, A.H. Wodke heads the MeDaX junior research group at the Medical Informatics department, UMG and works on FAIR bioMedical Data eXploration using graph technologies.

Irina Balaur is a post-doctoral researcher at LCSB, UNILU, working on translational research projects in various biomedical areas (including COVID-19, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer) and applying Neo4j technologies in connection to standard systems biology formats.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).