1. Introduction

Contemporary approaches to cultural heritage preservation subsume interdisciplinary collaboration and establishing balanced, integrative and sustainable processes of space management. With that aim, they point out the necessity for widening the scope of protection – from single monuments and historical buildings to wider spatial entities – historical towns, traditional settlements, cultural and historical landscapes [

1,

2]. These contemporary approaches demand establishing active relations between conservation of the natural and built environment on one hand, and urban and spatial planning on the other. These relations would enable settlements to develop in according with contemporary life conditions. In particular, they should be established for the simultaneous consideration of the different levels of space – from landscape, settlements, and buildings all the way to building details and materials. The existing spatial features should be identified, interpreted and used as the starting point for future development.

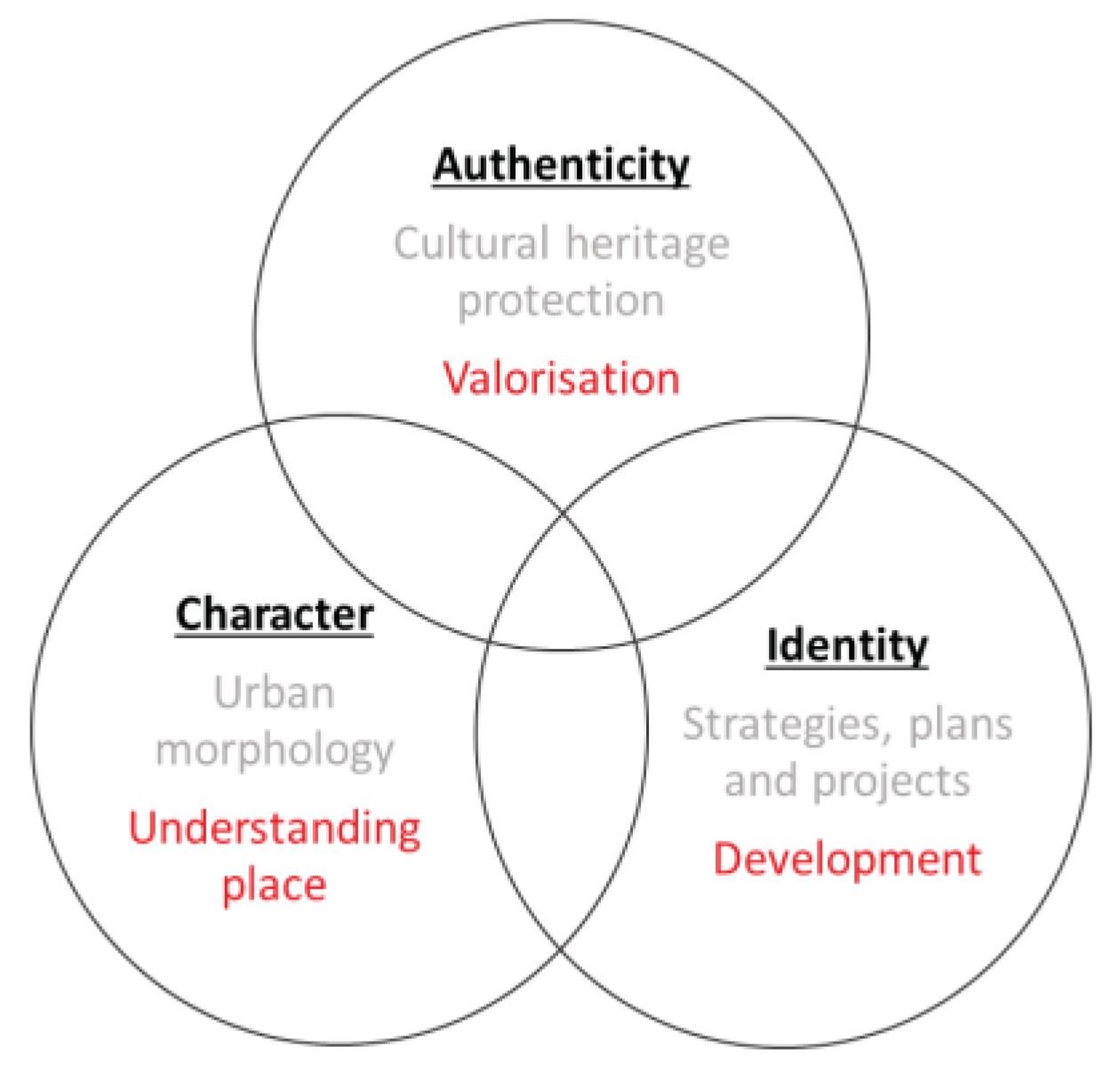

Three concepts can be singled out: authenticity, character and identity. They are sometimes used as synonyms, but in every discipline relevant for planning future development, each has a specific definition and significance (

Figure 1). In documents related to cultural heritage protection, special importance is given to the concept of authenticity [

3], which is one of the criteria for evaluating and declaring items part of the World Heritage List. The idea of character has been central to the urban morphology approaches that attempt to relate the description of a spatial area to the prescription for its future development. In his manual for the design of Stratford upon Avon, Kropf identifies local specificities at different spatial levels and considers possibilities for integrating them into design procedures. Being tied to local and traditional is not anachronistic, but rather an incentive to innovation [

4]. In strategic and planning documents, the most relevant of the three abovementioned is the concept of identity – local, regional, and national [

5,

6,

7].

1.1. Stara Planina Mountain and Its Natural and Cultural Potential

Stara Planina Mountain has underdeveloped natural and cultural potential in the Republic of Serbia. The set of values already recognized through strategic documents could be applied to this area – peaceful, healthy, traditional, preserved and authentic [

7].

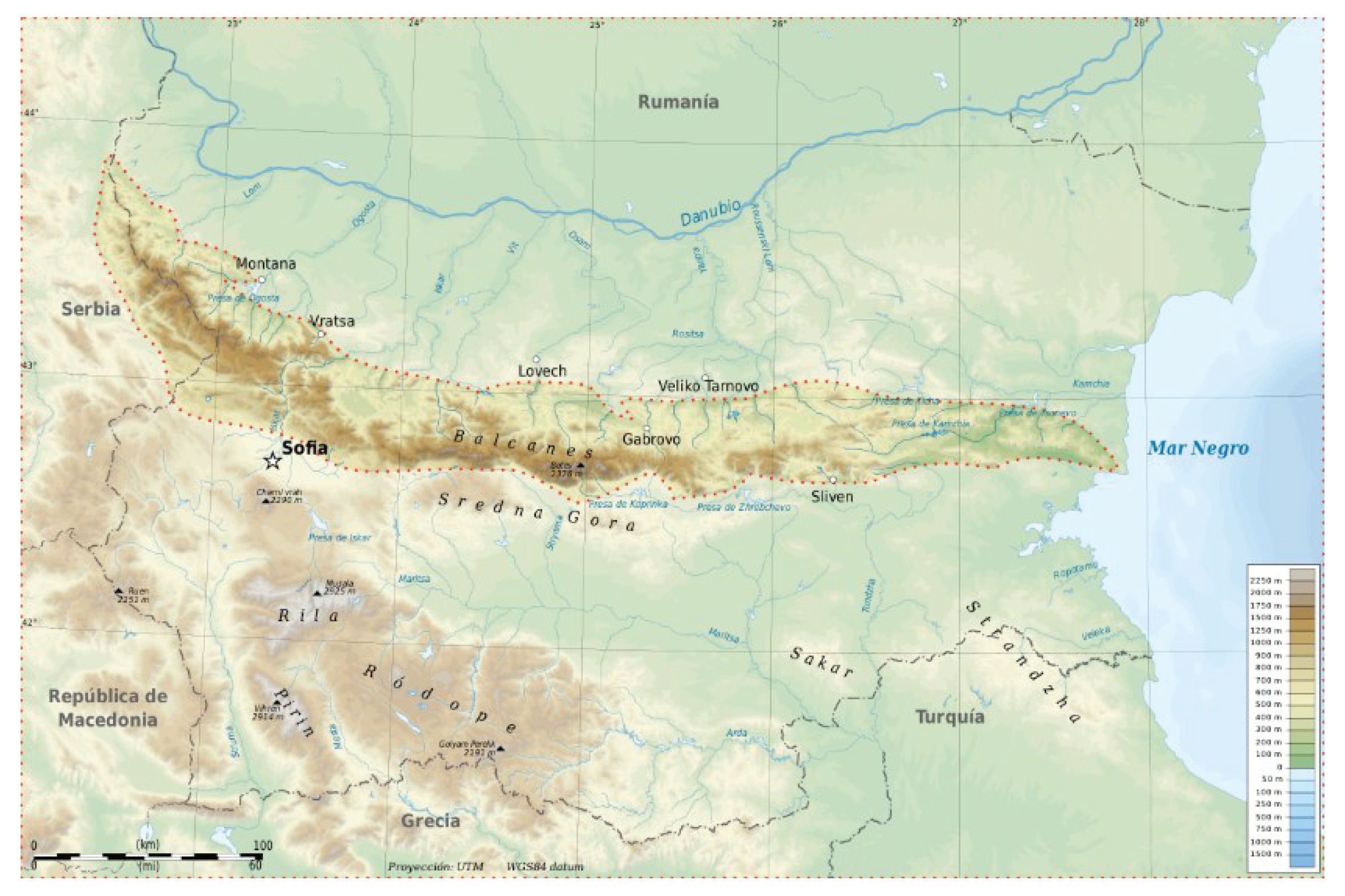

Stara Planina is a high mountainous area of Serbia located on the eastern border with Bulgaria. In the geographical sense, it belongs to the wider massif of the Balkan Mountains, which in the west-east direction mostly stretches through Bulgaria to the Black Sea (

Figure 2). The part of the mountain massif located in Serbia is protected by national laws as a nature park due to the exceptional value of its flora and fauna, geological diversity, landscape beauty and cultural heritage, including: medieval monasteries, folk architecture, traditional customs and local activities. Given the high natural and anthropogenic resources that characterize the area, Stara Planina is one of the development priorities of Serbia, right after the Danube [

8]. For the subject area it covers, a Spatial Plan for the Special Purpose Area has been adopted [

6]. It states that Stara Planina is the highest quality highland area in the Republic of Serbia, suitable for modern activities of year-round tourism and recreation, as well as cultural presentations, the ecologically exclusive agricultural production of healthy food, and other activities complementary to the nature park and tourism (forestry, water management, clean energy production, clean industrial and craft processing, etc.,

Figure 3). It is characterized by preserved nature, which on the one hand is an advantage in the sense that it is not endangered by excessive tourism, as is the case with popular destinations such as Zlatibor, Kopaonik and other mountains. On the other hand, its benefits are not sufficiently available, due to the lack of traffic and infrastructure connections, depopulation processes and the extinguishing of vital functions of the settlement. The main question is how to establish the right balance between development and protection. Namely, the natural and cultural heritage of Stara Planina need to be viewed in the context of wider spatial and geographical units, as part of the heritage of the Balkan Peninsula, as observed by geographer Jovan Cvijić [

9]. In his work on the Balkan Peninsula, he introduces his own understanding of anthropogeography, which in many ways forms the basis for today’s research of cultural areas and belts, and which has become an unavoidable theoretical starting point for the characterization of natural landscapes and historical urban landscapes.

This paper is focused on the typical rural settlements in the area of Stara Planina Mountain in Serbia, which are material evidence of the cultural and historical past of Serbia and the Balkans. These settlements are distinguished by their authenticity, identity and character, which have still not been destroyed by inappropriate development. We have sad examples of high-quality mountain areas in Serbia with obvious negative effects of urbanization, globalization and homogenization. Such areas highlight the need to prevent these effects in the mountain areas that are threatened by a possible disbalance between tourism development and inherited values, by appropriate sustainable development strategies.

2. Analysis of the Different Levels of Settlements

Traditional settlements on Stara Planina Mountain were formed over a long period. The process of their evolution includes various developmental stages in which the physical structure of the settlements was adapted to the needs of the inhabitants, and the settlements gradually acquired their own form and character. In general, settlements have the same types of elements, but what gives them identity and diversity are those specific elements that can be observed at different levels of detail: the main directions of growth and formation, public spaces, buildings, architectural details, materials, etc. The question is: to what extent are the specific characteristics of these settlements taken into account in the valid planning documentation that plans their future development? Are they recognized and treated in any way?

This brings us to Kropf’s idea of character and area analysis [

4]. Character is defined as the combined effect of all the characteristics that make a place recognizable. Character is not only the physical space but also the location, wider context, human activities and historical development. To identify the character of a place, it is necessary to observe and analyze it at different levels of scale: areas, land, types of settlements and types of houses, building details and materials (

Figure 4).

2.1. The Landscape Level

Starting from the landscape level, we can notice that the wider area of Stara Planina Mountain is characterized by exceptional natural features, a favorable climate, hydrological and hydrogeological specificities, forests, waters, rich flora and fauna. The large range of altitude enables the survival of endemic plant species, especially medicinal plants. The area has the features of hilly and mountainous relief, with an altitude of 200 to 2000 m above sea level. The climate is temperate continental in the lower parts, with variations in the valleys and a mountain climate in the heights. The area of agricultural land is over 55% of the territory, of which most is pastures, and then some arable land [

6].

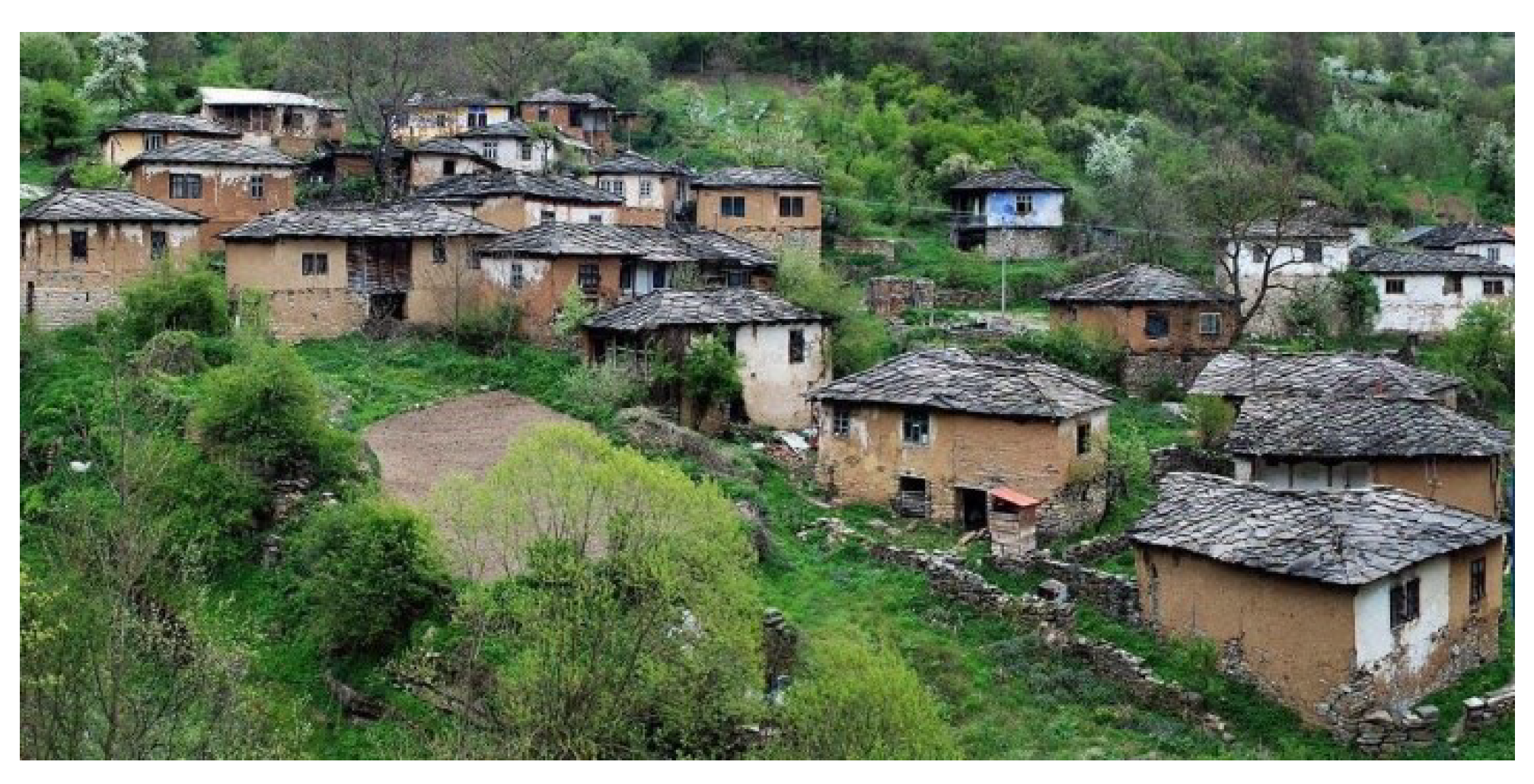

2.2. Types of Settlements

Cvijić notes that all the villages in the mountain area of Stara Planina are not a dispersed type, as is the case with most other villages in the high mountains in Serbia. He explains that they are a clustered type instead, more similar to villages in Serbian valleys [

9]. Indeed, the erosion forms which are part of the Stara Planina karst relief – sinkholes, bays, karst fields and plenty of river valleys – provided a way for the development of this type of settlement. Most of them are situated along the perimeter of the valley, where the springs and rivers are. Consequently, the settlements grew longitudinally along with the directions of the rivers. According to their clustered type, the villages are compact, with a high density and winding streets as a consequence of organic growth (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The agricultural fields are outside the settlements and not around the houses. The settlements have a core with public buildings – church, school, pub – usually located in a narrow area with limited possibilities for spatial development. The villages are divided into areas or neighborhoods, sometimes separated by natural obstacles: rivers, streams, rocks, ravines, etc. [

10].

The clustered type of Stara Planina villages could be surprising since their geographical position is in high mountains, where the dispersed type of rural settlements is expected. However, besides the previously mentioned natural-specific reasons for this type of development, there are also societal and historical ones. This part of Serbia has been greatly influenced by Byzantine and Turkish culture, which left traces both in urban and rural settlements. They produced specific characteristics such as the winding streets with cramped shops, cul-de-sacs, timber construction buildings and details, such as “ćepenak” (tur. ‘kepenk’), which are wooden window wings on shops. The especially harsh period under Turkish rulers developed the population’s desire for compact villages, i.e. stronger connections between the members of the community. This type of compact village, built for the Turkish hirelings, is also known as the Chitluk type and it can be recognized in the wider area in the Balkans inhabited also by Turks, Greeks and Macedonians (tur. Çiftlik, gr. τσιφλίκι, mcd. чифлиг).

2.3. Types of Houses and Vernacular Architecture

Besides types of settlements, the specific character of the rural settlements in Stara Planina can be observed at the level of the typical buildings – residential houses are the dominant form of buildings, then sacral buildings and agricultural ones. All of these are influenced by regional characteristics and the natural environment, as well as societal and historical circumstances.

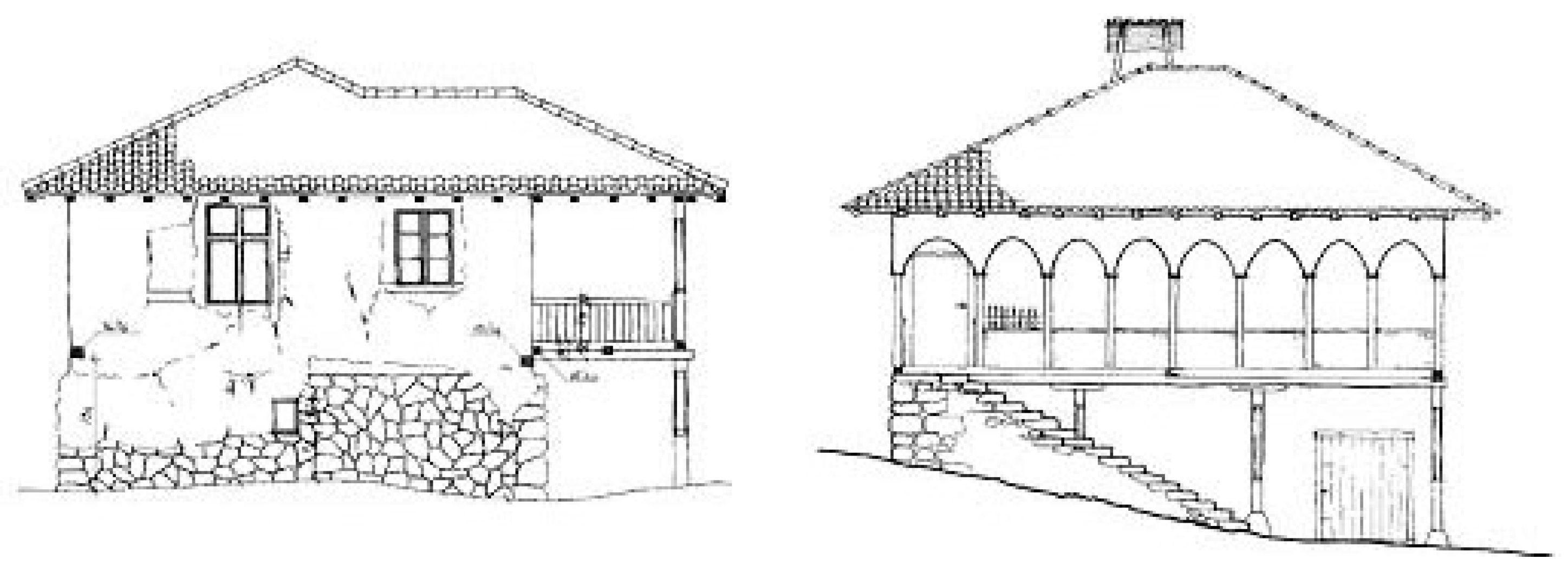

The residential buildings show recognizable regional features of traditional Balkan architecture [

11]. In the Stara Planina settlements, a variation of the Moravian type of house is recognizable (

Figure 7). It owes its name to the fact that it originated in the area of the river Morava, so it represents a lowland type of house. As is the case with the settlements, this is again something irregular for high mountain house types in Serbia, which are usually log cabins. Cvijić explained these exceptions due to the specificity of the karst relief in Stara Planina and the gravitation of settlements to valleys with climate conditions different to mountains. He also explained that the type shows Byzantine, Aegean, Turkish and Eastern influences. In this area, it is a variety similar to Bulgarian and Macedonian houses, because they had to be simple and plain and reflect the low social status of dwellers – under Turkish rulers.

The construction is ‘bondruk’ – a wooden skeleton infilled with organic material or brick. The house has a simple square or rectangular layout and consists of a basement which is partially buried due to the relief and an upper residential floor usually containing two rooms and a porch. In older house types, the roof above the porch is supported by an architrave construction, while in newer types, false arches are added. The basement is walled with stone, and the upper residential section is a combination of wood and plaster. The roof covering is shingles, which is a traditional covering from the earliest times [

12,

13].

The sacral buildings predominantly bear hallmarks of Byzantine civilization.

The agricultural buildings testify to old customs and agricultural production processes, which are an important element of immaterial cultural heritage. Among these buildings we can identify old watermills, barns, baskets and ‘pojate’. A pojata is a very specific type of house for farmers, outside the village, in the vicinity of their agricultural fields. There, farmers used to spend almost half a year, visiting their village house during saints’ days and for administrative purposes.

2.4. Materials and Details

The houses were built of available natural materials: wood, earth and stone. The silhouette of the chimney on a sloping roof covered with shingles is the most noticeable detail of the old house-type. Chimneys were built in the same way as the walls – they were made of wooden veneers covered with mud, which protected them from sparks. This appearance of chimneys was common in most parts of Serbia in the past. Usually, it was a wicker chimney, whose top was wider than the base. When covered with shingles, it is called a ‘komin’, and when not covered it is called ‘gologlavi’ (bareheaded).

The houses were erected on foundations of crushed stone in drywall or mud mortar. The shape of the stone, its structure and color influenced the great variety of ways of stacking and the appearance of the stone walls. The walls were built in a wooden skeletal structure with a filling of wooden interlacing plastered with mud, called ‘chatma’. The original weave was made of reeds, then of splinters, while the mortar made of mud was mixed with chaff.

One of the characteristic features of the old-style house is the porch with a raised section, called a ‘bed’, because for most of the year it was used for sleeping. Pillars and pillows, as constructive elements, appear on the porch, and in larger houses in the basement. They were decorated with carvings, which expressed aesthetic preferences. In general, the decoration was modest, in accordance with the low economic status of dwellers.

The appearance and size of the window openings is another element of the old house, which acted not only as a functional but also an aesthetic element (

Figure 8). In the beginning, they were simple openings, closed with a goat-skin or bladder. Later they were replaced by windows with wooden bars, with more complex decoration in wealthier families [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

3. Guidelines for Sustainable Development

By conducting an analysis following different scales of the observed area and coming to data on the existing characteristics and specifics of the site at different levels of detail, we can suggest an inventory of resources applicable for any future development. The key starting point for a successful outcome in future development is based on a thorough analysis of the existing situation and characteristics. This analysis sets limitations but also provides a source of possible solutions.

As Cvijić noticed, mountain settlements represent an important visual quality in the landscape, which contributes to the perception of its uniqueness. Like any architectural form, it has a psychologically perceived and visually aesthetic function. ‘A traveler who has stayed in the mountains for a long time, deserted and without traces of human work and life, feels joy when descending into the valleys, he encounters the first houses, scattered or crowded. At that moment, it is clearest to him how much the houses contribute to the appearance of the landscape.’ [

9]. Cvijić would say that a house is mainly an anthropogeographical and cultural-historical subject, and as mentioned in the introduction, we will consider the types of houses and their evolution from that point of view. This is exactly what puts the house and ordinary vernacular architecture at the center of a more recent and expanded approach to cultural heritage protection. Therefore, the arrangement of rural settlements should maintain and prolong the landscape, bearing in mind that minor changes at the settlement level may have a cumulative effect on the landscape.

3.1. The Landscape Characteristics

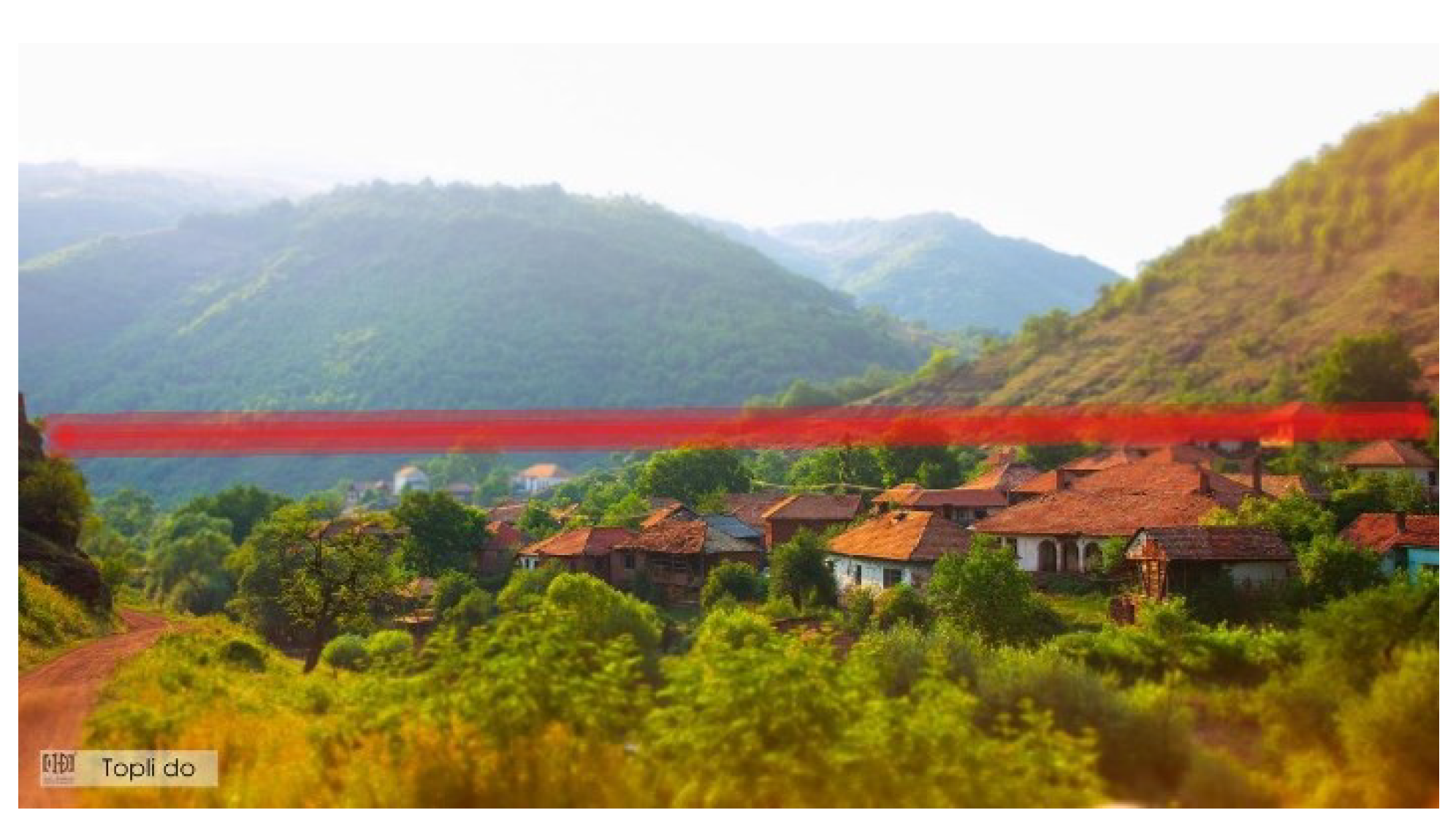

The clustered rural settlements of Stara Planina, mainly situated in the river valleys, have a clearly visible visual identity which needs to be preserved. This entails the principle that topography restrictions must be set so that in the case of new construction, the entire settlement remains below a certain height level (red line in

Figure 9).

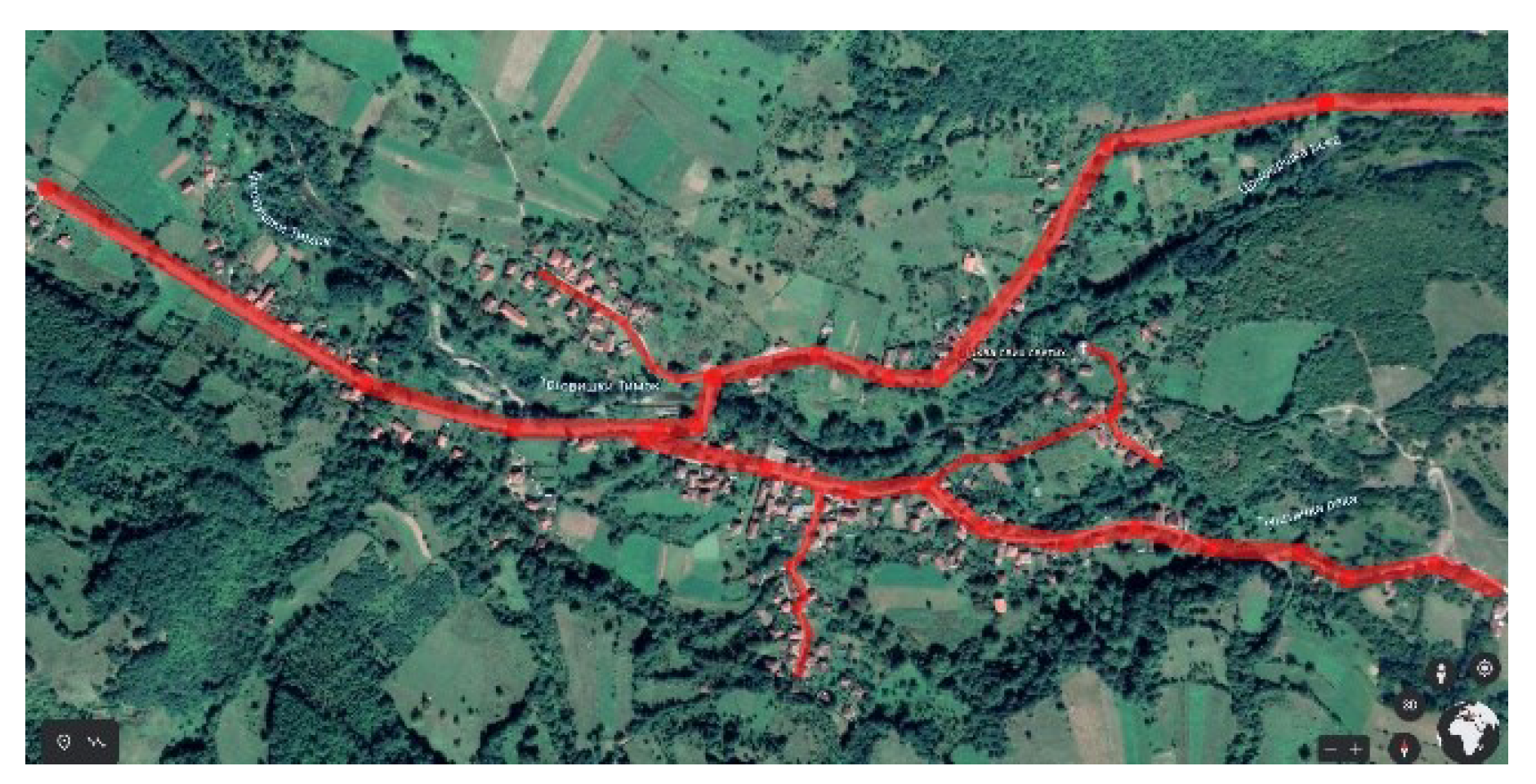

Also, in the case of settlement expansion, the inherited principle of spontaneous development along the rivers or perpendicular to them should be obeyed (red lines in

Figure 10). Also, new buildings must not block or obstruct the views.

Special care should be taken to preserve the view along the winding streets in the settlements, connecting different points with important landmarks such as the church, or with the surrounding landscape (

Figure 11).

Besides taking care of the height levels, vegetation should be carefully selected. It completes the image of the settlement and makes what we call the ‘soft edge’ (green line in

Figure 12) between the settlement and the landscape. Stara Planina Mountain already has its own set of authentic types of vegetation that need to be applied. There are five belts of forests and forest communities, namely: oak, beech and spruce forests, a belt of subalpine vegetation and a belt of curves.

3.2. The Inner Arrangement of the Settlements

In addition to the relationship with the landscape, it is important to preserve the inner arrangement of the settlements. This subsumes recognizing, preserving and improving the characteristic elements and relationships between them, as well as the existing logic of roads and landmarks – important buildings, crossroads and views.

Kropf would state that any new development should be adapted to the location and not the location to the development. The reconstruction of existing and construction of new forms should be adaptable and multifunctional. Some of the important characteristics of the physical structure can be seen in documents acquired from the institutions of protection as the starting point. Also, Kropf points out that restrictions resulting from analysis of the existing state are not an obstacle to innovation. On the contrary, they do not prevent creativity but rather channel it into ‘innovation with purpose’ and attributes such as the locality, sustainability and equity. The purpose of his manual is to act as a corrective in considering requests for construction and spatial interventions [

4].

3.3. Examples of Good Practice

There are good examples of new development in rural areas of Serbia which are based on the intrinsic qualities of the traditional settlements. One of them is a recently built holiday complex in the village Vrelo on Stara Planina [

14]. The complex is envisaged as a holiday place for employees in the local baking industry (city of Pirot). Following the principles of traditional settlements, it has been successfully constructed in the natural environment. According to the topography, the buildings are cascaded and grouped to evoke the sense of being a clustered type of Stara Planina Mountain village. On top of that, but not in contrast, high-quality materials are used and a high level of comfort is achieved so that it corresponds with contemporary demands for vacation facilities.

Another good example is a house in Mokrin [

15]. It is not on Stara Planina Mountain, but rather it is in a lowland village of Vojvodina in Serbia. Still, it gives good lessons of using traditional values and joining them with contemporary life. On one hand, it evokes the features of a traditional house and on the other, it introduces modern materials and elements. In particular, it introduces contemporary content in the form of new technologies, which give it the nickname ‘cyber-house’. It is envisaged for professionals of various profiles, enabling a remote working environment with plenty of accompanying leisure activities and services, such as enjoying nature and an authentic rural environment, traditional products, sports, etc.

Figure 14.

New development according to traditional settlement values in Mokrin.

Figure 14.

New development according to traditional settlement values in Mokrin.

There are type-morphological studies that aim to develop strategies to preserve the character of specific places, on the basis of applying explicit building rules that would maintain a balance between economic pressures and quality. One of them is a study of the area of St. Gervais-Les-Bains in the Alps in France [

16]. It describes the situation in which the space began to be threatened by the excessive construction of ski resorts, which began to erode the character of the area. An analysis of the possibility of integrating a typology of buildings into planning documents showed that analyzing the existing situation required a lot of time although it could certainly represent a valuable source of material. However, using such a typology depends on the political will of the actors implementing the plans. In essence, it is possible to implemented a typology only in environments where there is awareness of local communities and support in the local self-government to take into account those aspects of decision-making about space that are not legally binding, but that concern the quality of the environment.

A good example of a local initiative for the protection of authentic rural settlements is the association The Most Beautiful Villages of France, which was formed in 1982 on the initiative of one of the local government representatives and expanded to other countries, gaining a position as a European association. The specific features of rural settlements as cultural assets were recognized by this initiative, and to revitalize villages, promotional material was developed. But in the core of the agenda is not tourism but vitality – making settlements and the lives of their inhabitants viable, and not simply to meet tourist preferences at any cost. This vitality can be triggered by considering the settlement as a part of the landscape and an element of cultural heritage, putting it in the center of a regeneration strategy. Policies for preserving cultural heritage in this way relate to sustainable development strategies [

17,

18].

4. Perspectives for a New Sustainable Development

In the previous part of the paper, the expediency of morphological analyses at all levels of space and the possibility of their integration into planning guidelines were demonstrated. These analyses can be especially useful for the protection of objects and entities that are not registered as cultural heritage, and whose fate is often uncertain and depends on the planning approach [

19]. In addition, in the practice of conservation in Serbia, there is a professional attitude reflecting the need for characterizing the landscape of the whole state territory, as well as for forcing the spatial dimension of cultural heritage protection. That subsumes registering entire spatial entities that include natural and cultural heritage in the status of spatial cultural-historical units, cultural landscapes, geoparks, etc. [

20]. Authors who specifically analyze the vernacular architecture of the rural settlements on Stara Planina Mountain suggest that it can be protected as an architectural reserve [

21]. It is another of the concepts of protection that implies interdisciplinary cooperation, with the aim of creating specific spatial units that unite built and natural heritage, innovating infrastructure and content with the aim of revitalization, the development of tourism and achieving economic effects.

Also, various contributions to recognizing, valorizing, planning, using, and managing cultural landscapes in Serbia have been developed [

22]. By introducing the category of cultural landscapes in Serbian law [

23] in 2021. the perspectives have been opened for improving the up-to-date conservation and planning practice.

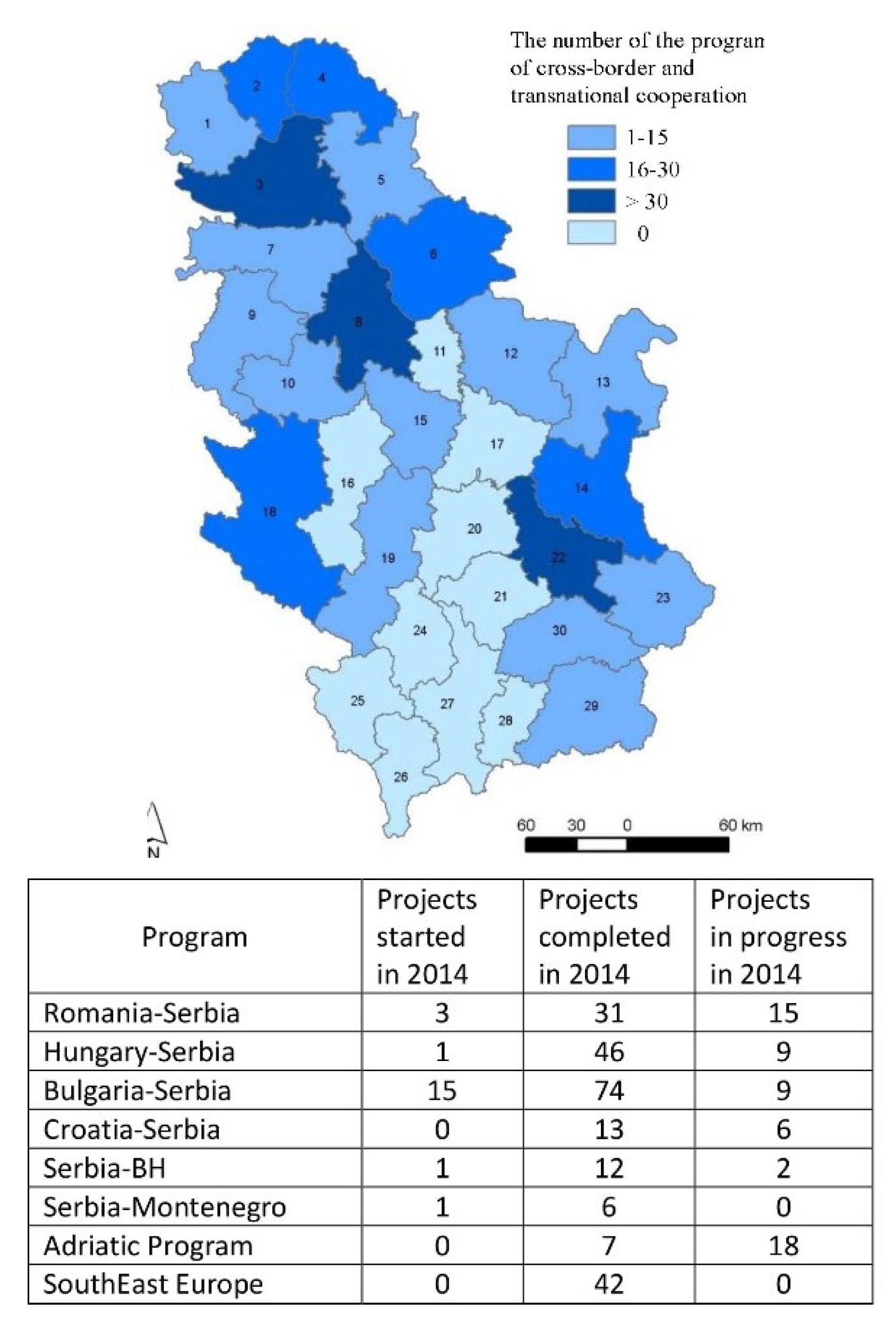

In addition to research, planning and strategic documents for the development of the area, there are important international programs and projects, among which those that belong to the group of cross-border cooperation programs between Serbia and Bulgaria stand out (

Figure 15 [

24]). One example is the Ad Vision project for strengthening the capacity of sustainable tourism development in the border area of Stara Planina, which especially emphasizes the development of adventure tourism. The project envisages a list of resources, a roadmap for adventure tourism, conferences and seminars, competitions in disciplines such as orienteering, and the presentation of results through websites, mobile applications, catalogs and movies. In this way, the management capacity of the destination is raised, and a specific tourist product is developed (

Figure 16a [

25]). Another example is the Via Militaris project, which uses the experimental methodology of the Living Laboratory or Living Lab in order to interact and create development alliances between individuals, companies and institutions. The Nišava-Iskra-Marica valley, which ends with Istanbul, is one of the main roads on the Balkan Peninsula from Roman and Byzantine times to the present day. One of the results is an innovative tourist tool for information and joint creation – the Living Lab platform and mobile application (

Figure 16b [

26]). One more interesting project is the Creative Caravan, whose activities are based on education for business and creative industries for a selected group of young people from Serbia and Bulgaria who aim to work in a real business environment with micro enterprises. New models of communication and presentation are planned. This concept is also applicable in the rural areas of Stara Planina, where it is necessary to stimulate the revival of old crafts, but also the introduction of new activities and contents in order to revitalize the area (

Figure 16c [

27]).

In addition to these projects directly related to the Stara Planina area, it is useful to consult other international projects for creating strategies and plans, because they often contain ideas and concepts that transcend the boundaries of administrative areas, and enable connections with the region, thus attracting investment.

5. Conclusion

Stara Planina, with its natural and anthropogenic potential, represents one of Serbia’s development priorities. In recent decades, the sustainable protection of cultural heritage has become a key global challenge. In this context, trends towards large-scale urbanization open up questions such as: how can new development take place while respecting and maintaining the intrinsic values and unique qualities inherited from previous generations, especially in rural areas, whilst protecting features that are not under institutional protection and belong to ordinary vernacular architecture?

It is necessary to develop the skills of defining, researching, protecting, using and managing the architectural heritage. This requires knowledge of different methodologies and thematic approaches relevant to these skills. The following stand out: the improvement of planning methodology through the provision of planning guidelines, based on a detailed analysis of the existing situation at all spatial levels; improvement of the practice of conservation for larger spatial units, that is, an integrative approach to the protection of cultural landscapes; using examples of good practice and adapting them to the specifics of the location and the context of conservation and planning; and participation in cross-border and international cooperation programs, which increases the visibility of heritage, and thus its chances of inclusion in contemporary development programs and projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N. and B.M.; methodology, A.N. and B.M.; formal analysis, A.N. and B.M.; investigation, A.N. and B.M.; resources, A.N. and B.M.; data curation, A.N. and B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N.; writing—review and editing, A.N. and B.M.; visualization, A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this paper is supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (No. 451-03-68/2023-14/200006).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Council of Europe. Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020: Towards an Inclusive, Smart and Sustainable Europe of Diverse Regions, 2011, Gödöllő.

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, 2011, Vienna.

- UNESCO&ICOMOS&ICCROM. Тhe Nara Document on Authenticity, 1993, Japan.

- Kropf, K. Stratford-on-Avon. District Design Guide. Stratford-upon-Avon: Stratford-on-Avon District Council, UK, 2001.

- National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. Zakon o prostornom planu Republike Srbije 2010 [Law on the Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia, 2010-2020], Službeni glasnik RS (Official Gazette RS), No. 88/2010, Belgrade, 2010.

- 6. National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. Prostorni plan područja Parka prirode i turističke regije Stara Planina [Spatial Plan of the Natural Park Area and Tourist Region of Stara Planina], Službeni glasnik RS (Official Gazette RS), No. 115/2008, Belgrade, 2008.

- 7. Faculty of Economics-Belgrade University. Strategija razvoja turizma opštine Dimitrovgrad [Strategy of tourism development of the Dimitrovgrad Municipality], Beograd, 2008.

- 8. National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. Prostorni plan Republike Srbije, 2021-2035 [Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia], not adopted yet.

- Cvijić, J. Balkansko poluostrvo i južnoslovenske zemlje [Balkan Peninsula and South Slavic Countries], Beograd: Državna štamparija, 1922.

- Rodić, Z. Narodno graditeljstvo i stanovanje u Pirotu i okolini [Traditional architecture and housing in the Pirot region] In: V. Marjanović, Ed. Bulletin of the Ethnographic Museum in Belgrade, Volume 74, No.1, Belgrade: Ethnographic Museum, 2010.

- Kojić, B. Stara gradska i seoska arhitektura u Srbiji [Old urban and rural architecture in Serbia], Beograd: Prosveta, 1949.

- Radonjić Živkov, E. , Krstanović, B. Atlas narodnog graditeljstva Srbije. Narodno graditeljstvo opštine Knjaževac-Stara Planina [Atlas of Traditional Architecture of Serbia. Traditional Architecture of the Municipality of Knjaževac - Stara Planina], Beograd: Republički zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture, 2003.

- Ljubenov, G. Tradicionalno arhitektonsko nasleđe u regionu Stare planine - arhitektura koja nestaje. Beograd: OrionArt, posebno izdanje SANU br. 695, Odeljenje za likovne i muzičke umetnosti knj. 13, 2020.

- Jovanović, M. Kuće za odmor radnika pekare – Branković Mountain Resort na Staroj planini. https://www.gradnja.rs/brankovic-mountain-resort-stara-planina/, 2020, Accessed: 10.11.2020.

- Mokrin House of Ideas, https://www.mokrinhouse.com/, Accessed: 10.11.2020.

- Samuels, I. , Pattacini, L. From description to prescription: reflections on the use of a morphological approach in design guidance. Urban Design International 2, 1997, pp. 81-91.

- Les Plus Beaux Villages de France, https://www.les-plus-beaux-villages-de-france.org/fr/nos-villages/, Accessed: 10.11.2020.

- Ducros, H.B. The New Rural in Les Plus Beaux Villages de France: Heritage Preservation, Promotion and Valorization in the Post-Agricultural Village. Doctoral dissertation, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2014.

- Niković, A. , Manić, B. Тhe challenges of planning in the field of cultural heritage in Serbia, Facta Universitatis, Series: Architecture and Civil Engineering, XVI, 3, 2018, pp. 449-463.

- Niković, A. , Manić, B. Prostorna dimenzija zaštite kulturnog nasleđa u Srbiji: prilog unapređenju institucionalnog i pravnog okvira. U: Mrlješ, R. Zbornik radova: XI naučnostručna konferencija ‘Graditeljsko nasleđe i urbanizam’, Beograd: Zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture grada Beograda, 2021, pp. 346-359.

- Ljubenov, G. , Vuksanović Macura, Z. Arhitektonski rezervat kao oblik očuvanja nasleđa - primer sela Stare planine, Arhitektura i urbanizam, br. 54, 2022, pp. 44-59.

- Muminović, E. , Radosavljević, U., Beganović, Dž. Strategic Planning and Management Model for the Regeneration of Historic Urban Landscapes: The Case of Historic Center of Novi Pazar in Serbia. Sustainability, 2020; 12, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 23. National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia. Zakon o kulturnom nasleđu [Cultural Heritage Law], Službeni glasnik RS (Official Gazette RS), 2021, No. 129/21, 2021.

- 24. Ministry of Construction, Transport and Infrastructure of the Republic of Serbia. Izveštaj o ostvarivanju Prostornog Plana Republike Srbije i stanju prostornog razvoja 2014 [The Report on the Implementation of the Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia and the state of spatial development from 2014], Beograd, 2015.

- Interreg-IPA CBC, Bulgaria-Serbia. AD-VISION (Association “Regional partnerships for sustainable development – Vidin” (RPSD - Vidin)) http://advision.one, Accessed: 10.11.2020.

- Interreg-IPA CBC, Bulgaria-Serbia. Via Militaris-A Corridor for Sustainable Tourism Development https://www.viamilitaris.net/, Accessed: 10.11.2020.

- Interreg-IPA CBC, Bulgaria-Serbia. Creative Caravan https://www.creativecaravan.eu/participate_youth, Accessed: 10.11.2020.

Figure 1.

Overlapping approaches in achieving the sustainability of a high-quality built environment.

Figure 1.

Overlapping approaches in achieving the sustainability of a high-quality built environment.

Figure 2.

The wide regional context of the Stara planina mountain area.

Figure 2.

The wide regional context of the Stara planina mountain area.

Figure 3.

The variety of activities introduced in planning documents and strategies.

Figure 3.

The variety of activities introduced in planning documents and strategies.

Figure 4.

The idea of character and the analysis of the different levels of settlements.

Figure 4.

The idea of character and the analysis of the different levels of settlements.

Figure 5.

The clustered types of rural settlements in the Stara Planina Mountain area situated in valleys of the corresponding rivers, from the upper left to the lower right: a. Ćuštica, b. Dojkinci, c. Senokos, d. Gostuša, e. Janja, f. Topli Do. Source: Google Earth.

Figure 5.

The clustered types of rural settlements in the Stara Planina Mountain area situated in valleys of the corresponding rivers, from the upper left to the lower right: a. Ćuštica, b. Dojkinci, c. Senokos, d. Gostuša, e. Janja, f. Topli Do. Source: Google Earth.

Figure 6.

Gostuša village. Source: Republički zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture.

Figure 6.

Gostuša village. Source: Republički zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture.

Figure 7.

The types of vernacular residential buildings: a. older type, b. newer type.

Figure 7.

The types of vernacular residential buildings: a. older type, b. newer type.

Figure 8.

The building craftwork: a. drywall, b. chimney, c. window.

Figure 8.

The building craftwork: a. drywall, b. chimney, c. window.

Figure 9.

Restriction of height level for new development.

Figure 9.

Restriction of height level for new development.

Figure 10.

Restriction of directions of development.

Figure 10.

Restriction of directions of development.

Figure 11.

Preserving view and visual connections with nature.

Figure 11.

Preserving view and visual connections with nature.

Figure 12.

Preserving the ‘soft edges’ between the built environment and nature.

Figure 12.

Preserving the ‘soft edges’ between the built environment and nature.

Figure 13.

New development in Vrelo village on Stara Planina Mountain.

Figure 13.

New development in Vrelo village on Stara Planina Mountain.

Figure 15.

The number of cross-border and transnational cooperation projects.

Figure 15.

The number of cross-border and transnational cooperation projects.

Figure 16.

A variety of topics in international projects important for tackling and reviving traditional values of space: a. Ad Vision project; b. Via Militaris; c. Creative Caravan.

Figure 16.

A variety of topics in international projects important for tackling and reviving traditional values of space: a. Ad Vision project; b. Via Militaris; c. Creative Caravan.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).