1. Introduction

Nearly 120 million people in the United States experience unhealthy levels of ozone and particulate pollution, and among them over five million are residents or commuters in the city of Chicago [

1]. Fine particulate matter (PM

2.5) is one of the most harmful air pollutants, as these particles are small enough to enter the lungs and bloodstream [

2]. PM

2.5 is also an important topic of study for its relevance to climate change, as a type of aerosol that can have cooling or warming effects on the climate [

3]. It is also important for its relevance to environmental justice, as neighborhoods of low-income or high-minority residents tend to experience higher concentrations of and exposure to PM

2.5 [

1,

4,

5].

In general, PM

2.5 concentrations in Chicago have decreased in recent years, though the proportion of those concentrations attributable to vehicles and other local sources has increased [

6]. Concentrations vary widely across the city and vary significantly by season [

7,

8]. Additionally, though particulate matter originating from outdoor sources has been widely studied, indoor PM

2.5 levels have received less attention and are important because outdoor air pollution can infiltrate inside buildings, and indoor sources of particulate matter exist as well. Most Americans spend about 90% of their time indoors [

9], so studying indoor PM

2.5 is important to assess peoples’ overall air pollution exposure.

When examining the variation of PM

2.5 in an urban setting, elevation is a factor to consider, given the prominence of high-rise apartments and office buildings in which many people live and work daily. Chicago is ranked the second “tallest” city in North America, based on the number of skyscrapers – 308 buildings in the city over 60 meters tall [

10]. Furthermore, residents in high-rise buildings tend to be white, young, college-educated, and in higher income brackets [

11]. These patterns are a continuation of Chicago’s history of residential segregation. Interestingly, the people living on the highest floors in a given high-rise building are generally those with the highest incomes of all the tenants in the building, with individuals with lower incomes living toward the bottom [

12], as units on higher floors offer residents better views and more access to natural light and are therefore more expensive. This is highly relevant to the intersection of environmental justice with the topic of urban air pollution.

Past studies have indicated that air pollutant concentrations tend to decrease with increasing altitude, as demonstrated, for example, by Bisht et al. [

13] studying black carbon and particulate matter in Delhi, India; KAILA [

14] studying NO

2 and PM

2.5 in Helsinki, Finland; and Liu et al. [

15] studying PM

2.5 in two neighborhoods in Nanjing, China. As explained by Liao et al. [

16], who studied PM

2.5 in Taipei, Taiwan, this decrease in many cases may be due to increased distance at higher altitudes from ground-level sources such as traffic emissions. A particular area of concern in urban areas is the problem of street canyons, when buildings lined up on both sides of a road prevent ventilation and dilution of pollutants. According to Liu et al. [

15], within street canyons there often exists a specific height at which peak pollutant concentration occurs, which may not be at ground level. How PM

2.5 varies with height around high-rise buildings in Chicago is not well studied. Therefore, we conducted a project in an office building in the Edgewater neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Location

To increase our understanding about vertical variations of PM

2.5 in urban areas, we installed eight PurpleAir sensors (four PA-II outdoor sensors and four PA-I indoor sensors) between April 8 and May 7, 2023, in an 11-floor office building in Edgewater, Chicago. The building and the period of the data collection were decided based on the availability of volunteering office occupants who allowed us to temporarily install an indoor sensor inside their office and an outdoor sensor on the exterior wall of their office. All four offices are located on the side of the building that faces away from a major road. The Edgewater neighborhood, located on the north side of the city, is situated next to Lake Michigan, containing several parks, beaches, and major roadways. According to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning [

17], in 2023 there were about 56,296 residents in Edgewater, and about 56% are White, 17% Hispanic, 13% Black, 13% Asian, and 1% “Other.” The median age is 37.7 years old, the median annual income is

$61,872, and the employment rate is 93.5%. Edgewater was a good test neighborhood for its urban location and proximity to roadways and sufficiently tall buildings from which to measure air pollution levels as they vary by height.

2.2. PurpleAir Data

PurpleAir is a network of sensors that measure indoor and outdoor PM

2.5. Data are collected by PurpleAir sensors using a beam from a laser counter that reflects off particles present in an air sample. The reflections translate to estimates of real-time mass concentrations of particulate matter present in the air sample. Each PurpleAir sensor contains two channels, which alternate reading air samples every five seconds, corresponding to an average reading of the sensor every two minutes [

18]. We used PA-II outdoor sensors and PurpleAir Touch indoor sensors to monitor outdoor and indoor air quality, respectively. These sensors measure PM

2.5 and record temperature, relative humidity, and barometric pressure.

PurpleAir sensors were chosen because their data are already integrated into experimental maps (https//fire.airnow.gov) developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Forest Service. Prior work has evaluated the performance of monitors in the PurpleAir network, and newly established correction factors can be used to correct reported PM

2.5 values to better agree with Federal Equivalent Method (FEM) measurements [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Following the recommendation for outdoor air quality monitors in the U.S., as used in O’Dell et al. [

23], we used the correction factor developed by Barkjohn et al. [

22], as shown below:

in which PA

cf_1 is the average of the PM

2.5 values in μg/m

3 measured by Channels A and B over a two-minute interval with the conversion factor equal to 1, and RH is relative humidity in percent. According to O’Dell et al. [

23], this correction factor can be applied to indoor sensors as well, and therefore we applied it to measurements taken by both outdoor and indoor sensors. In addition, we discarded data points whose PM

2.5 values were less than 0 μg/m

3 or greater than 80 μg/m

3. According to more reliable data retrieved from EPA air quality monitors, in this location there were no days during our study period in which the average PM

2.5 levels exceeded 80 μg/m

3.

2.3. The Correlation between Outdoor and Indoor PM2.5

We analyzed the correlation between outdoor and indoor PM

2.5 to examine the infiltration of outside air into the building following the method of Lv et al. [

24], expressed with the following equation:

where C

in is the actual indoor PM

2.5 concentration, C

out is the actual outdoor PM

2.5 concentration, C

s represents the concentration of PM

2.5 generated from indoor sources. F

in is the infiltration coefficient, representing the factor by which PM

2.5 generated outdoors enters into the building, which depends on the ventilation system and permeability of the building. In the most efficiently ventilated buildings, F

in should theoretically be zero, indicating that the building is not “leaky” or vulnerable to pollutant infiltration from the outdoors.

2.4. Colocation and Data Collection

We co-located our four outdoor sensors by placing them side-by-side together outside the office building for a week between March 29 and April 4, 2023, to determine to what extent the sensors’ readings agreed with each other. To correct the differences observed between sensors during this co-location, we used these data to calculate how much the mean PM2.5 concentration of each sensor deviated from the mean across all four sensors. These amounts of deviation were added to all future data points for each respective sensor. The same process was done for the four indoor PurpleAir sensors co-located inside over the same week-long period.

We then installed a pair of indoor and outdoor sensors for an office on each floor (one, four, six, and nine) of the building (

Table 1). They were positioned on the inside and outside of the office’s exterior wall that faces away from the roadside. The four offices were selected based on the voluntary willingness of occupants to allow installation for one month, i.e., between April 8 and May 7, 2023. In addition to the data provided by the sensors we installed, we obtained data from another outdoor PurpleAir sensor in Edgewater, situated on the fourteenth floor of a condominium about 800 m away from the office building. Even though this sensor was on a different building, we decided it would be beneficial to examine its data as well because of the higher elevation of the sensor.

3. Results

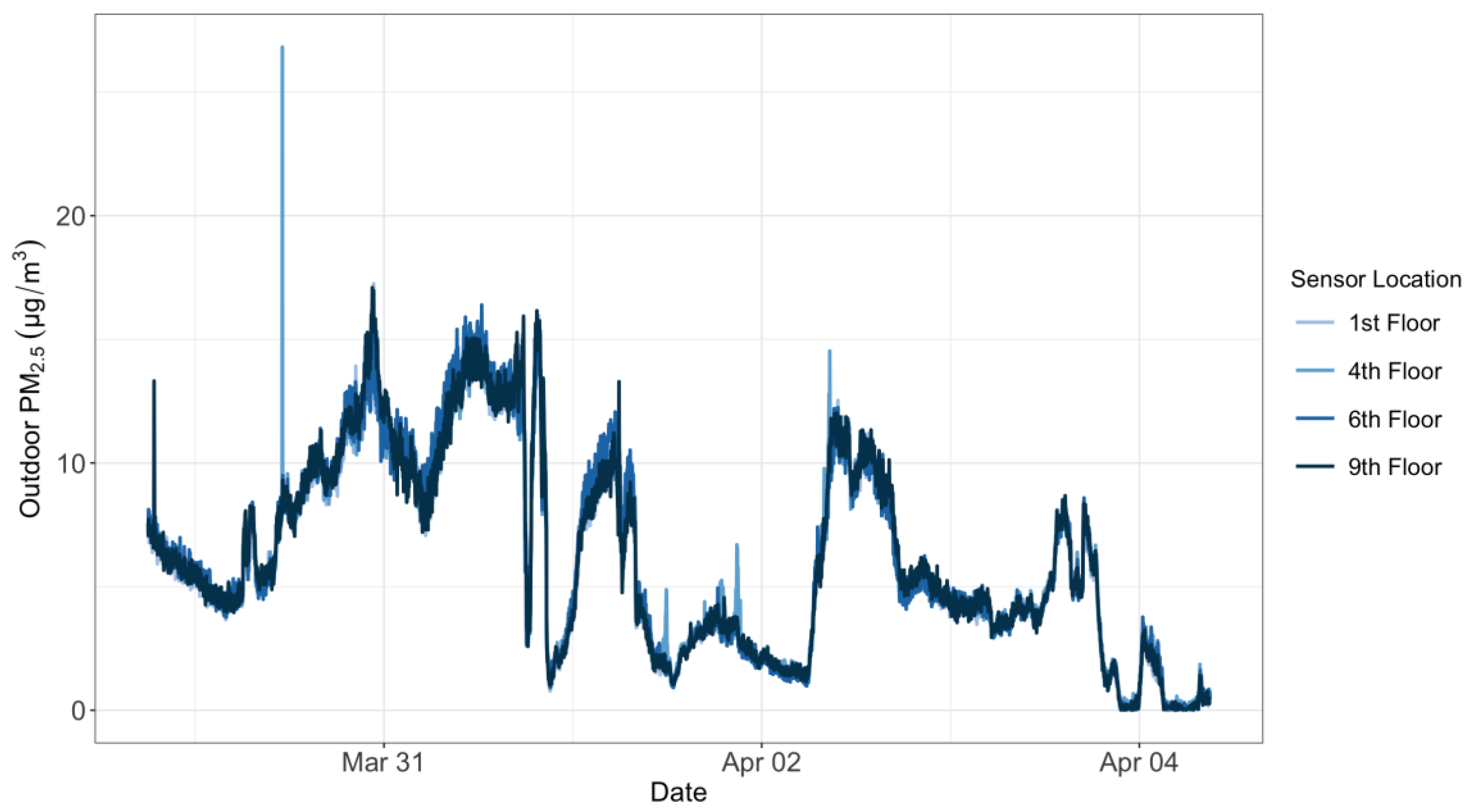

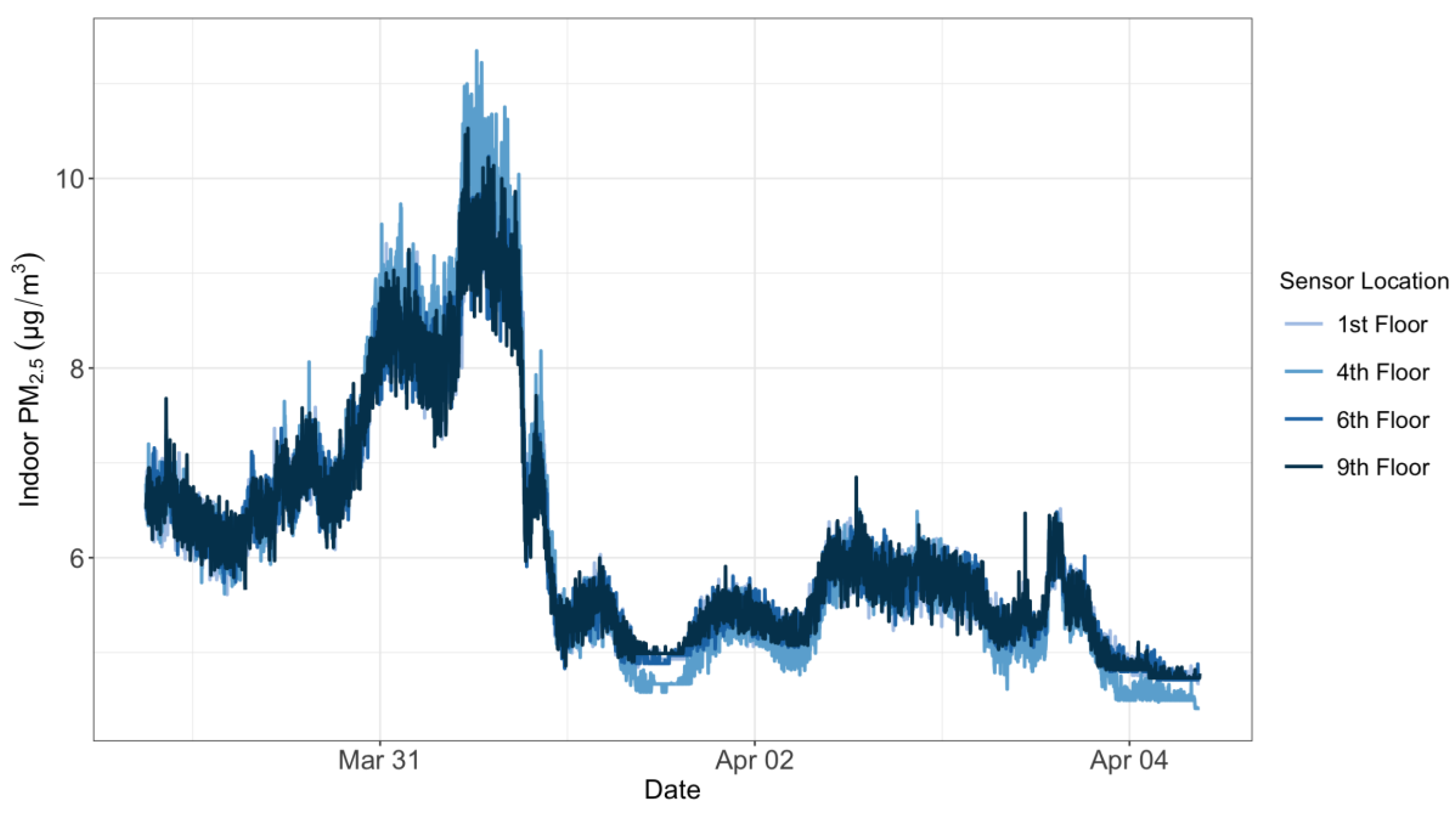

We conducted co-location tests for both indoor and outdoor sensors for a week between March 29 and April 4, 2023. Raw PM

2.

5 measurements taken by each sensor were corrected based on the relative humidity values using Equations 1 and 2. We then interpolated the corrected PM

2.5 to regularly gridded two-minute intervals to perform a comparative evaluation of the sensors. Our results show that each outdoor sensor agreed closely with the other outdoor sensors (the R-squared value between any two sensors is between 0.97 and 0.99) (

Figure 1). The same was true for the co-location results of the indoor sensors (the R-squared value between any two sensors is between 0.96 and 0.97) (

Figure 2). The average PM

2.5 concentration of each outdoor sensor during the week displayed biases that ranged between -0.16 and +0.15 mg/m

3 from the mean value of all the four outdoor sensors combined. The biases for the four indoor sensors ranged between -0.10 and +0.22 mg/m

3. These biases were removed from the observations before we compared PM

2.5 levels at different floors in the office building. The co-location test did not include the public outdoor sensor installed on the 14

th floor of the condominium. Therefore, we did not remove any potential bias for this 14

th floor sensor.

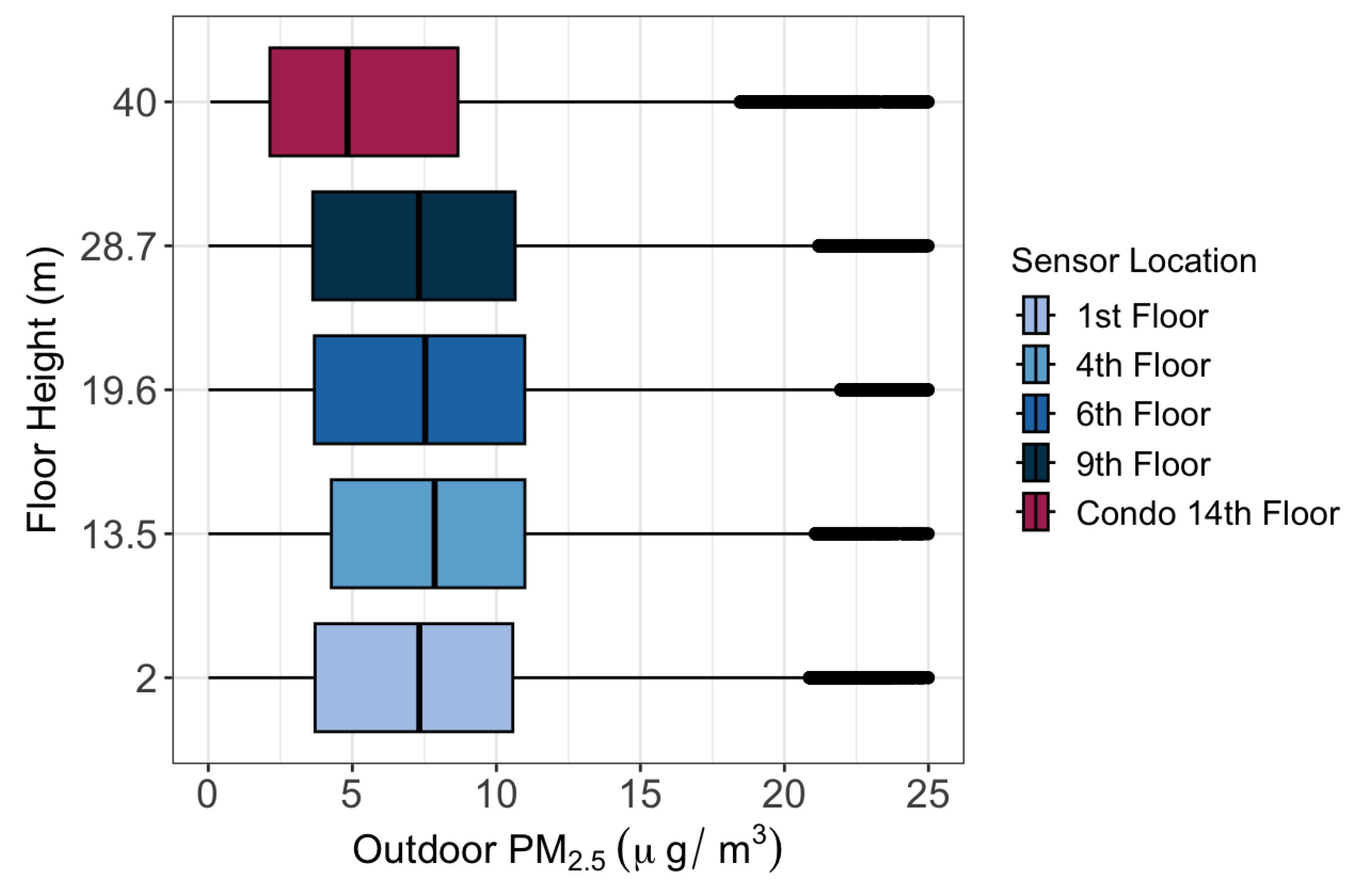

During the one-month study period between April 8 and May 7, 2023, data collected by the outdoor sensors were first corrected based on the relative humidity value using Equations 1 and 2 and then their biases were removed based on the co-location results. The results indicated that the median PM

2.5 concentration increased with increasing height between the 1

st and 4

th floors (

Figure 3). The median outdoor PM

2.5 concentrations decreased for each successive level of altitude beyond the 4

th floor by 0.11 μg/m

3 per meter elevation. Statistical tests (Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn test) showed significant differences between every outdoor sensor compared to every other outdoor sensor, except for one pair (the 1

st and 9

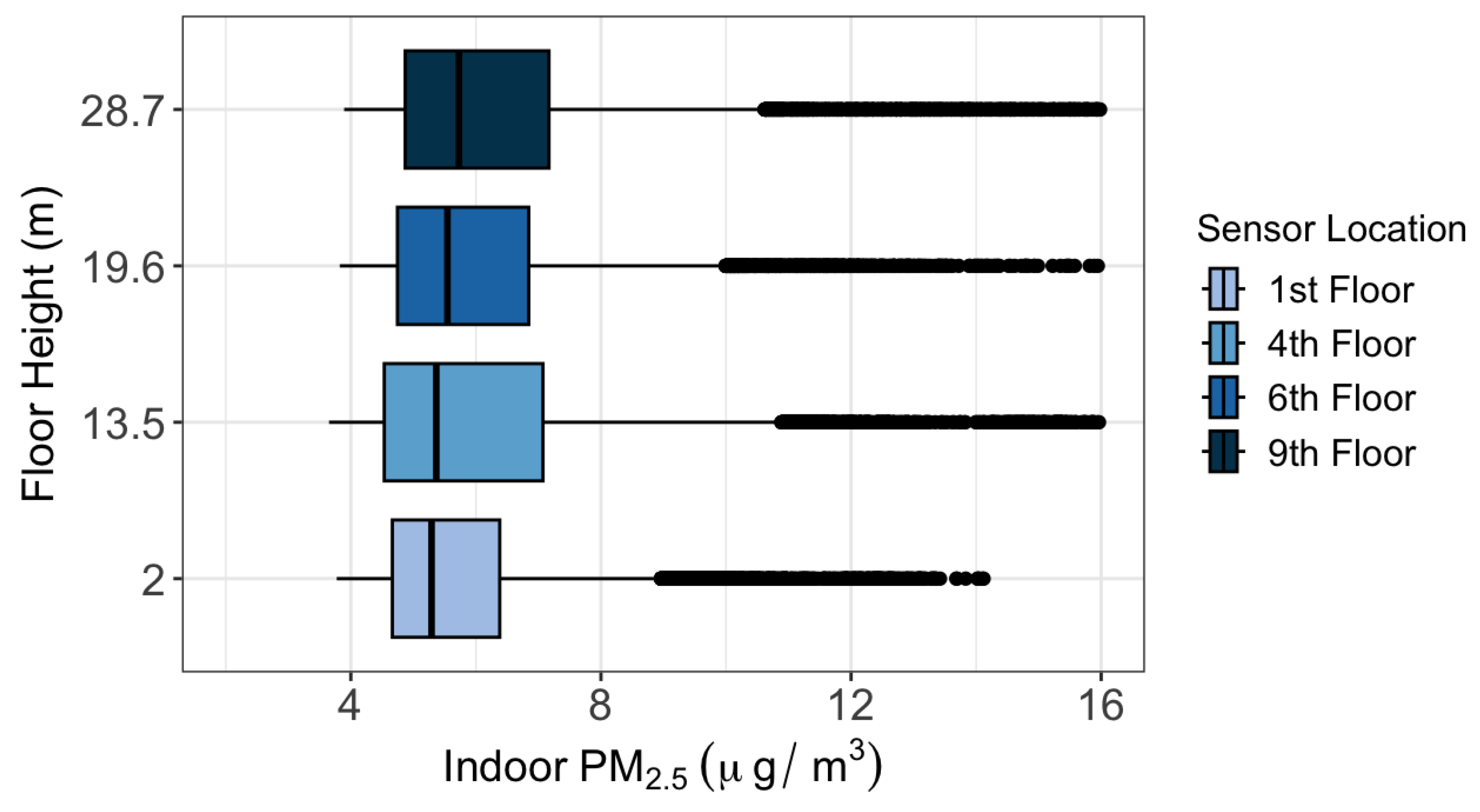

th floors). For indoor air quality, the median PM

2.5 concentration increased with increasing height (+0.02 μg/m

3 per meter elevation) for all levels (

Figure 4). Although small, these differences between every indoor sensor were statistically significant.

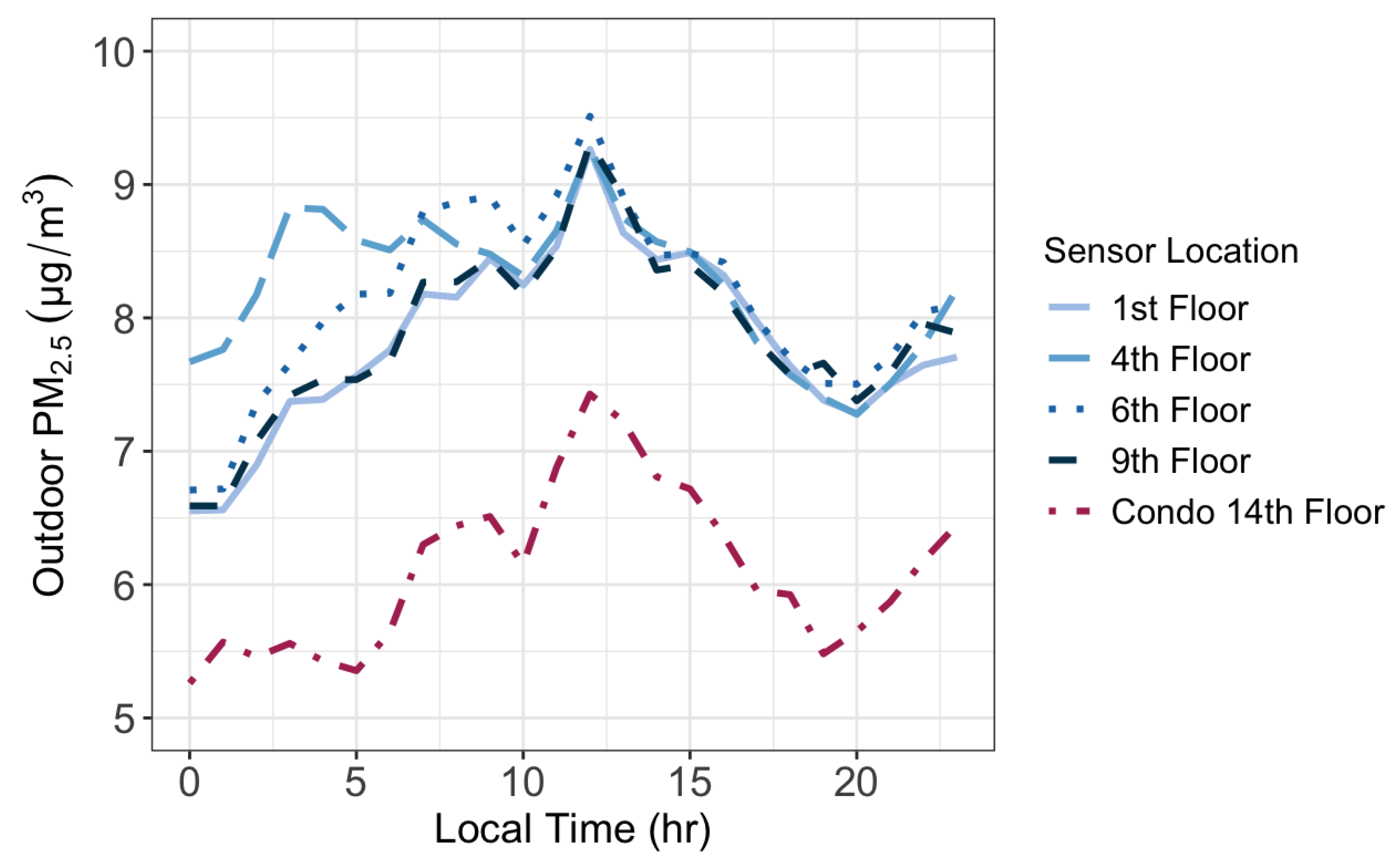

We calculated the hourly average PM

2.5 concentrations to study the diurnal cycles of the indoor and outdoor PM

2.5 at different floors. Outdoor PM

2.5 concentrations displayed a similar daily cycle at all floor heights (

Figure 5). They all decreased in the afternoon until 8 PM, then increased throughout the night and early morning followed by a drop between 9 AM and 10 AM and increased again until peaking at noon. Such variations are controlled not only by the diurnal changes in PM

2.5 emissions from traffic but also by the dynamics of the atmospheric boundary layer [

25]. The vertical mixing in the boundary layer is weak at night and strongest in the mid-afternoon causing air pollutants to accumulate at night and disperse in the afternoon. The most pronounced differences of PM

2.5 by floor height occurred between 12 AM and 8 AM when the atmospheric condition is stable and vertical mixing is weak.

Figure 5 also shows that PM

2.5 concentrations decreased as the height of the sensor increased except for the 1

st floor. That the 1

st floor PM

2.5 concentrations are lower than those at the 4

th floor is because the sensor at the 1

st floor is situated above bushes and surrounded by trees, which could have helped to clean the air by removing PM

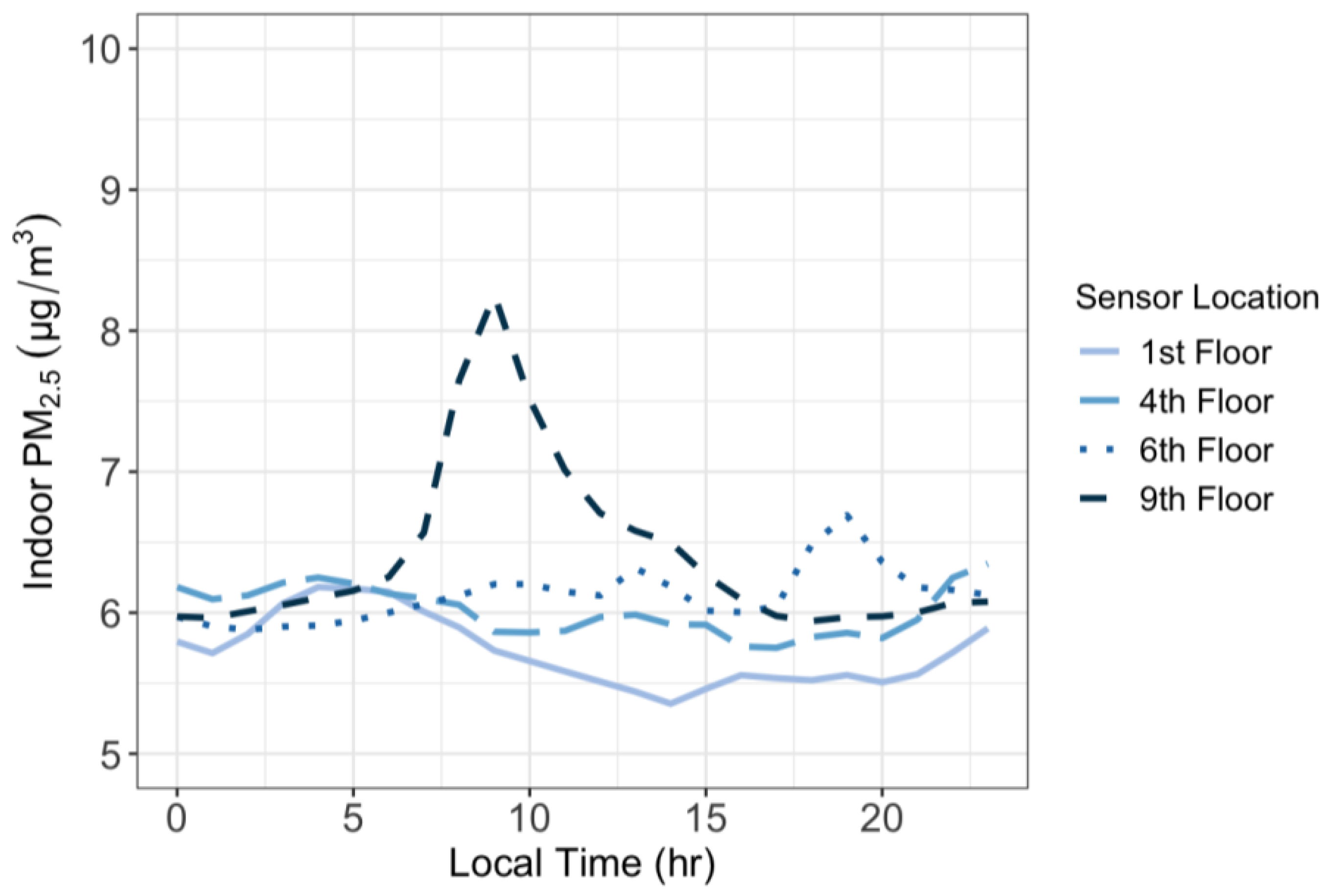

2.5 from the air. Indoor PM

2.5 concentrations, however, remained relatively constant over a day (

Figure 6), though with a late-morning spike in the concentration on the 9th floor. The greatest variation of indoor PM

2.5 by floor height appeared between the hours of 9 AM and 3 PM likely caused by the activities of office occupants during their work hours.

To understand what caused the indoor air quality to change, we compared the indoor and outdoor daily average PM

2.5 concentrations observed by the four paired indoor and outdoor sensors. By conducting a linear regression test, our results show a positive correlation between the indoor PM

2.5 and the outdoor PM

2.5 (

Figure 7 and

Table 2), indicating the influence of outside air on the indoor air quality through infiltration. The infiltration factors, represented by the slope of the linear fitted line (F

in), vary between 0.22 and 0.29. The intercept of the linear fitted line represents the average amount of PM

2.5 attributable to indoor sources (C

s), and it ranges between 3.91 μg/m

3 and 4.23 μg/m

3 across the four floors. In comparison, the C

s and F

in values for office buildings in Daqing, China, were 4.83 μg/m

3 and 0.72, respectively [

24]. We then estimated the contribution of outdoor PM

2.5 to indoor PM

2.5 using the method in Lv et al. [

24] by calculating C

outF

in/C

in. Our results show the contributions of outdoor PM

2.5 to the mean indoor PM

2.5 are between 30% and 40% across the four floors, which are lower than the contribution rate of 79% in Lv et al. [

24].

4. Discussion

This study conducted in Edgewater, Chicago, focused on analyzing the vertical profile of PM2.5 concentrations in both outdoor and indoor environments of high-rise buildings using PurpleAir sensors. The near-ground layer of the atmosphere is typically not probed by conventional instruments such as satellites, lidar, or air balloons. The PurpleAir sensors offer a low-cost method to investigate the fine vertical resolution of PM2.5 concentration change in the area.

We found good agreement among PurpleAir sensors during the one-week co-location period between March 29 to April 4, 2023, indicating the reliability of the sensors for the study. The findings revealed that PM2.5 concentrations decreased at 0.11 μg/m3 per meter for each successive level beyond the 4th floor. This trend may be attributed to the increasing distance from ground-level pollution sources, such as traffic, as elevation increased. That PM2.5 on the 1st floor is lower than on the 4th floor is likely due to the fact that the outdoor sensor was situated above bushes and there are trees nearby. The vegetation could have helped to increase the dry deposition of PM2.5. Indoor PM2.5 concentrations increased with increasing height at 0.02 μg/m3 per meter elevation, from 5.3 μg/m3 at the first floor to 5.8 μg/m3 at the 9th floor, which is mostly likely caused by the greater infiltration coefficient which is 0.22 at the 1st floor and 0.29 at the 9th floor.

Hourly averages of outdoor PM2.5 concentrations showed the clearest variation by height between the hours of 12 AM and 8 AM. The same pattern of outdoor PM2.5 concentration increasing between the 1st and 4th floors, then decreasing after the 4th floor, still holds over this period. Mornings exhibit the most variation due to the low atmospheric boundary layer overnight, resulting in little atmospheric mixing and more distinct stratification with height. For the indoor sensors, the clearest variation in air quality by height appeared to be between 9 AM and 3 PM. This could be due to this period being the peak of the workday with the most activity in the building occurring.

Comparing outdoor to indoor PM2.5, for each floor their concentrations were positively correlated; the indoor air pollution stayed at a concentration lower than outside. This follows logically given that we expect most of the PM2.5 sources in this setting to originate outdoors. The Fin values, or the slopes of the regression lines, are low and indicate that there are low factors of infiltration of outdoor PM2.5 penetrating inside the building. The Cs values, or the indoor intercepts of the regression lines, indicated that the sources of indoor air pollution were low, around 4 μg/m3.

A potential limitation of this study was that the sensors at different floor heights were not placed exactly above one another, but distributed along the same wall of the building according to the location of the office in which an occupant was willing to host a sensor. Additionally, the chosen condominium building is a few blocks away and may experience slightly different primary emission sources of PM2.5 compared to the office building.

This project serves as a case study for two buildings in Edgewater, Chicago, for one month in spring. A full understanding of the vertical profile of PM2.5 concentration requires a longer and more extensive period of study, incorporating greater temporal and spatial coverage and greater vertical extent. Future research could include a greater number of different sensor heights and could incorporate a greater degree of control between heights, with data collection periods spanning multiple seasons of the year and examining how weather impacts outdoor air quality and how building type influences infiltration indoors.

Research on this topic will provide a greater nuance to our understanding of how people in urban areas may be exposed to different levels of air pollution while on different building floors, as air quality is an important topic for its relevance to climate science, public health, and environmental justice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.W.; Methodology, M.M.W.; Software, M.M.W.; Validation, M.M.W., A.R., and P.J.; Formal analysis, M.M.W. and A.R.; Investigation, M.M.W. and A.R.; Resources, P. J.; Data curation, M.M.W., A.R., and M.C.R.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.W.; writing—review and editing, M.M.W., A.R., M.C.R.W., and P.J.; visualization, M.M.W., A.R., M.C.R.W.; supervision, M.C.R.W. and P.J.; project administration, P.J.; funding acquisition, P. J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science Foundation’s GEOPAths program through Award Number 2119465.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Olivia Sablan and Emily Fischer at Colorado State University for guidance on handling of PurpleAir measurements and providing feedback to the analyses. We especially thank the four occupants for allowing us to install PurpleAir sensors in their offices.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- American Lung Association. (2022). State of the Air 2022, www.lung.

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2023). Particulate Matter (PM) Basics. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2001), Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by J. T. Houghton et al., Cambridge Univ. Press, New York.

- Liu J, Clark LP, Bechle MJ, Hajat A, Kim S-Y, Robinson AL, Sheppard L, Szpiro AA, Marshall JD. Disparities in air pollution exposure in the United States by race/ethnicity and income, 1990–2010. Environ Health Perspect. 2021, 129. [Google Scholar]

- Mikati, I., Benson, A. F., Luben, T. J., Sacks, J. D., & Richmond-Bryant, J. Disparities in Distribution of Particulate Matter Emission Sources by Race and Poverty Status. American journal of public health 2018, 108, 480–485. [CrossRef]

- Milando, C., Huang, L., & Batterman, S. Trends in PM2.5 emissions, concentrations and apportionments in Detroit and Chicago. Atmospheric Environment 2016, 129, 197–209.

- Bell, M. L., Dominici, F., Ebisu, K., Zeger, S. L., & Samet, J. M. Spatial and temporal variation in PM2.5 chemical composition in the United States for health effects studies. Environmental health perspectives 2007, 115, 989–995.

- Pinto, J. P. , Lefohn, A. S., & Shadwick, D. S. Spatial variability of PM2.5 in urban areas in the United States. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2004, 54, 440–449. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (1989). Report to Congress on indoor air quality: Volume 2. EPA/400/1-89/001C. Washington, DC.

- Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. (2023). Skyscraper Center - Chicago. Skyscraper Center. https://www.skyscrapercenter.com/city/chicago.

- Muszynski, A. (2020). High Rise Living: The Change in Chicago Dwelling Patterns (Unpublished bachelor’s thesis). University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

- Verhaeghe, P. P., Coenen, A., & Van de Putte, B. Is Living in a High-Rise Building Bad for Your Self-Rated Health? Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 2016, 93, 884–898. [CrossRef]

- Bisht, D. S., Tiwari, S., Dumka, U. C., Srivastava, A. K., Safai, P. D., Ghude, S. D., Chate, D. M., Rao, P. S. P., Ali, K., Prabhakaran, T., Panickar, A. S., Soni, V. K., Attri, S. D., Tunved, P., Chakrabarty, R. K., & Hopke, P. K. Tethered balloon-born and ground-based measurements of black carbon and particulate profiles within the lower troposphere during the foggy period in Delhi, India. Science of the Total Environment 2016, 573, 894–905. [CrossRef]

- KAILA. (2019). HSY Effect of distance and height on air quality, https://www.hsy.fi/en/air-quality-and-climate/information-for-urban-planning/effect-of-distance-and-height-on-air-quality/.

- Liu, F., Zheng, X., & Qian, H. Comparison of particle concentration vertical profiles between downtown and urban forest park in Nanjing (China). Atmospheric Pollution Research 2018, 9, 829–839.

- Liao, H.T., Lai, Y.C., Chao, H.J., Wu, C.F. Vertical Characteristics of Potential PM2.5 Sources in the Urban Environment. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2023, 23, 220361. [CrossRef]

- Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. (2023). Edgewater: A Snapshot of Change in Chicago's Far North Side. CMAP. https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/126764/Edgewater.pdf.

- PurpleAir. (2023). What do PurpleAir Sensors Measure, and How Do They Work? https://community.purpleair.com/t/what-do-purpleair-sensors-measure-and-how-do-they-work/3499.

- Magi, B.I., Cupini, C., Francis, J., Green, M., & Hauser, C. Evaluation of PM2.5 measured in an urban setting using a low-cost optical particle counter and a Federal Equivalent Method Beta Attenuation Monitor. Aerosol Science and Technology 2020, 54, 147–159. [CrossRef]

- Malings, C., Tanzer, R., Hauryliuk, A., Saha, P.K., Robinson, A.L., Presto, A.A., & Subramanian, R. Fine particle mass monitoring with low-cost sensors: Corrections and long-term performance evaluation. Aerosol Science and Technology 2020, 54, 160–174. [CrossRef]

- Mehadi, A., Moosmüller, H., Campbell, D.E., Ham, W., Schweizer, D., Tarnay, L., & Hunter, J. Laboratory and field evaluation of real-time and near real-time PM2.5 smoke monitors. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2020, 70, 158–179. [CrossRef]

- Barkjohn, K.K., Gantt, B., & Clements, A.L. Development and application of a United States wide correction for PM2.5 data collected with the PurpleAir sensor. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021, 14, 4617–4637. [CrossRef]

- O’Dell, K., Ford, B., Burkhardt, J., Magzamen, S., Anenberg, S. C., Bayham, J., Vischer, E. V., & Pierce, J. R. Outside in: the relationship between indoor and outdoor particulate air quality during wildfire smoke events in western US cities. Environmental Research: Health 2022, 1, 015003.

- Lv, Y., Wang, H., Wei, S., Zhang, L., & Zhao, Q. The correlation between indoor and outdoor particulate matter of different building types in Daqing, China. Procedia engineering 2017, 205, 360–367.

- Manning, M. I., Martin, R. V., Hasenkopf, C., Flasher, J., & Li, C. Diurnal patterns in global fine particulate matter concentration. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 2018, 5, 687–691.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).