1. Introduction

End-of-life (EoL) care, though lacking a precise definition, generally refers to healthcare provided to individuals approaching death. This care encompasses ongoing treatment for the underlying disease, and palliative measures to manage symptoms and enhance quality of life (QoL) [

1]. The provision of EoL care typically involves a collaborative decision-making process, often supported by an established advanced care plan [

1]. Emerging evidence from multiple studies suggests that initiating EoL care in a timely manner can bring about numerous benefits [

2,

3,

4]. These include enhancing patients' QoL, alleviating symptoms, and potentially reducing the unnecessary utilization of acute care services—which extends beyond just cancer patients [

2,

3,

4]. Despite the beneficial effects of EoL and palliative care, global statistics indicate that only around 14% of patients in need receive palliative care [

5]. Even in high-income countries, the results are comparable [

6].

In Norway, where healthcare services are predominantly public and free, municipalities oversee primary health care, including primary palliative care and local emergency rooms (emergency primary healthcare clinics); while specialist healthcare is provided by four health regions, typically upon referral from primary care [

7,

8]. Palliative care is integrated into public health services, with specialist palliative care centers in hospitals staffed by at least one palliative care physician and one oncology nurse (ON). These specialists are available for consultation within hospitals and by primary care clinicians (general practitioners and ONs), who can also refer patients to them [

8].

The geographical location of individuals has wide-ranging implications for healthcare delivery, costs, and, notably, for individuals' preferences regarding end-of-life care, particularly the desire to spend their final days at home [

6,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] . Despite the widespread preference for home-based care at the end of life, the opportunity to do so is only available to a relatively small percentage of individuals, typically ranging from 10% to 30% in most countries [

6,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14], including Norway [

15].

Gomes and her team identified several essential conditions that are almost prerequisites for patients to have the option of spending their final days at home. These conditions include the patient's own preference, the family's preference, access to home palliative care, and the availability of district or community nursing [

16]. In order to fulfill more individuals' desires to receive end-of-life care at home and to comprehensively address their needs, Kellehear stresses that "end-of-life care is everyone's business," thereby extending responsibility beyond just families and healthcare services to encompass communities [

17].

Research has consistently demonstrated a rise in healthcare service utilization during the final months of life [

18,

19,

20,

21]. However, there remains a need to fully understand the key variables that define service utilization from both a community perspective and patient characteristics. Our study endeavors to address this gap by examining potential disparities in service utilization during the twelve months leading up to death among patients with breast cancer, dementia, and heart failure. Additionally, we aim to identify individual and institutional factors that might influence the likelihood of patients dying at home.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria and Data Sources

Utilizing data from the Norwegian Causes of Death Registry (NCDR), our analysis includes all patients who passed away in 2019 with underlying diagnoses of breast cancer (ICD-10 D05), dementia (ICD-10 F00-F03), or heart failure (ICD-10 I60, I61, I63-I64). By employing personal identification numbers obtained from the NCDR, we combined data from various registers, including the National Patient Register (a discharge register), the Municipal Patient and User Register, the Education Register, and KOSTRA - a register that describes municipal use of resources. The Directorate of Health oversees the first two registers, while Statistics Norway manages the latter two.

Data was collected for the period covering the last 365 days before the date of death for each patient, except for variables describing the patients’ co-morbidities where we collected data from the National Patent Register and the Municipal Patient and User Register for up to two years before the death date. All data were anonymized for the researchers.

2.2. Outcomes

The main outcomes were health service use the last 365 days before the death day (D0), including GP visits, hours of home nursing per week, short- and long-term stays in municipal institutions (mainly nursing homes), as well as outpatient and inpatient stays in hospitals. Additionally, our analysis specifically investigated into a binary variable indicating whether patients were at home (1) or in institutions (0), i.e., nursing home or hospital, on the day before their death (D-1). The reason for using D -1 as the time of measurement for ‘Dying at home’ was that services were not registered consistently on the death day.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

The characteristics of the cohorts were described by frequencies for categorical variables and by median for continuous variables.

To identify variables associated with ‘dying at home’ we performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 96% confidence intervals (CI). We made separate analyses for the three cohorts that were defined by the causes of death with two groups of variables included, variables on patient and variables on municipal level. Variables on individual level including gender, age categorized in 10-year age bands from 50 to 89 years and with patients below 50 and above 90 years in separate groups, marital status, education (primary, secondary, and higher education) and number of comorbidities (0, 1-2, 3-4, 5 and above). Variables on municipal level included person-years of GPs and caring personnel in total, all normalized by 10 000 inhabitants.

We registered data on 15 comorbidities (se

Appendix A) from up to two years before the death day. Comorbidities were generated from registration of both primary and secondary diagnoses and from both hospital inpatient and outpatient stays as well as consultations with GPs registered in the Municipal Patient and User Register for up to two years before the death date.

Data management and analyses were conducted in SAS Studio 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population

In 2019, 606 patients succumbed to breast cancer, 2900 to dementia and 1415 to heart failure. Among breast cancer patients median age were 73.0 years, dementia patients 88.4 years and heart failure patients 86.2 years (

Table 1), When classified by 10-year age bands, the highest number of deaths occurred in the 70-79 age group, with 147 cases (24.3%), for the breast cancer patients while in the two other groups the highest numbers of death were in the age group 90 years and above.

The breast cancers patients deviate from the two other groups also by a higher share being married, by fewer comorbidities, and higher education levels – naturally reflecting these patients’ younger age.

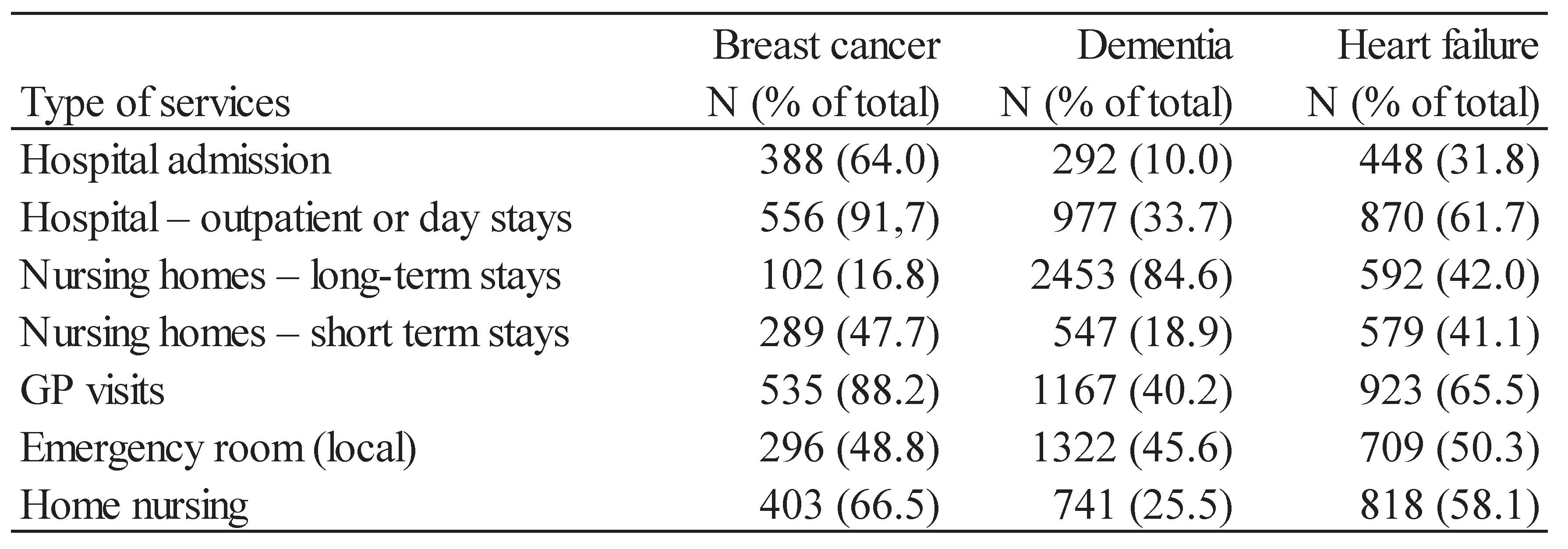

3.2. Service Use at End-of-Life

In the year leading up to their death, a significant proportion of breast cancer patients (64.0%) experienced at least one hospital admission, with 388 patients affected. Furthermore, 556 patients (91.7%) received hospital treatments either as outpatients or during day stays. In contrast, the utilization of hospitals among patients with dementia in the years preceding death was notably lower, with only 10% admitted to hospitals and 33% receiving outpatient consultations or day stays. Dementia patients, however, were frequent users of nursing homes.

Breast cancer patients were found to make extensive use of general practitioner (GP) services and frequently visited local emergency rooms (emergency primary healthcare clinics). Conversely, dementia patients had a different utilization pattern, with fewer individuals visiting GPs. It is important to note that while in nursing homes, patients receive medical services from an attending physician who is not part of the GP list patient system.

In terms of care profile, heart failure patients fell somewhere between the utilization patterns observed in cancer and dementia patients.

Table 2.

Patients use of health service last 365 days of life (number of patients with at least one visit).

Table 2.

Patients use of health service last 365 days of life (number of patients with at least one visit).

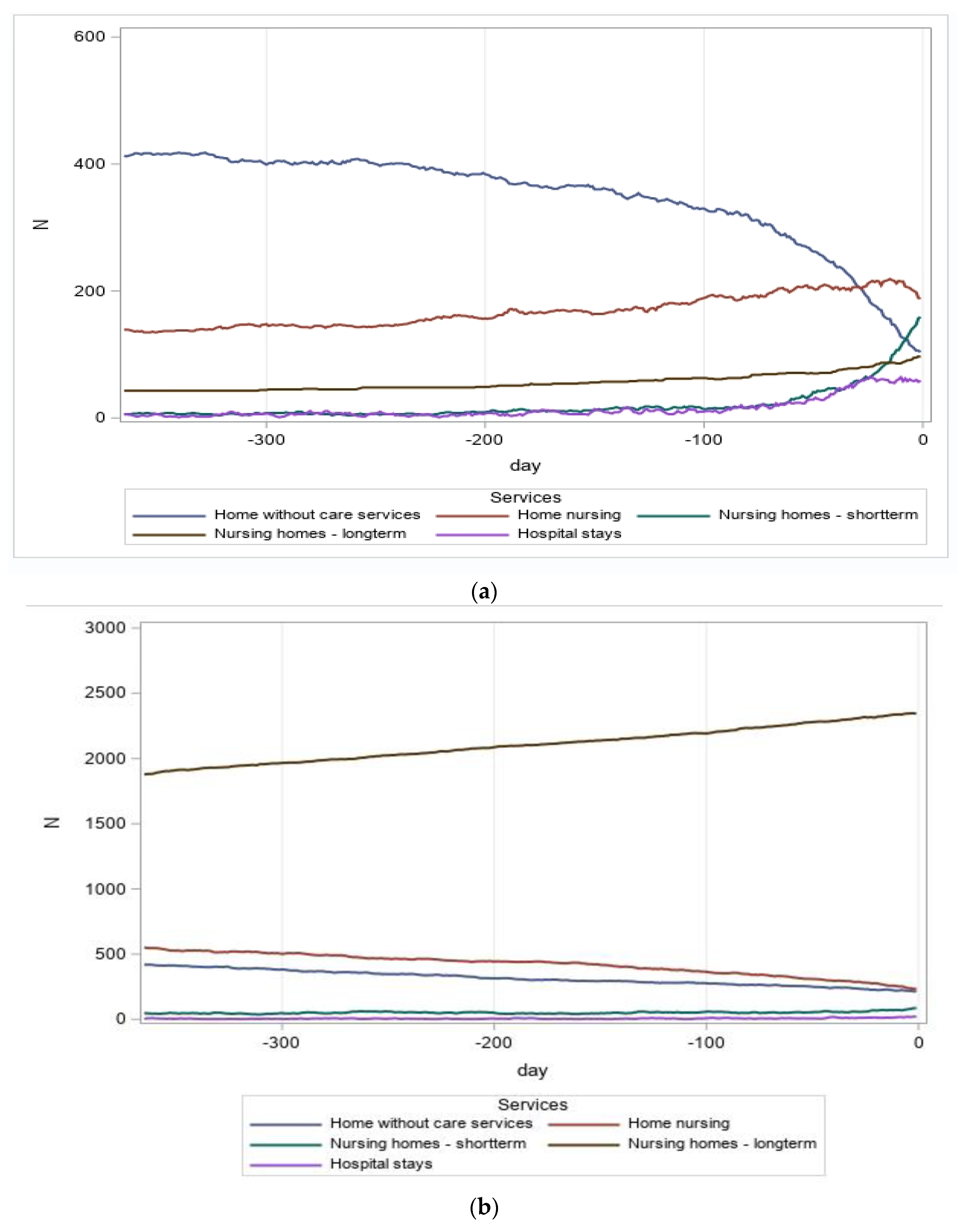

The dynamic changes in service utilization are further illustrated in

Figure 1a-1c, highlighting the use of services during each of the final 365 days before death among the patient groups. For all three patient groups, hospital stays remained relatively low but gradually increased during the last two months of life. Long-term stays in nursing homes were frequent and steadily increasing among dementia patients, while they remained at a lower level among breast cancer patients. Notably, there was a significant increase in short-term stays in nursing homes among breast cancer patients during the last 2-3 months of life. Furthermore, for the breast cancer patients, a progressive increase in home nursing was observed until the last 4-6 weeks, followed by a decline in the number of recipients. This decrease was primarily due to patients being transferred to nursing homes, especially for short-term stays.

The proportion of patients residing at home without any of the aforementioned services gradually diminished, particularly for the breast cancer patients. This trend corresponded to the increasing number of patients receiving care in hospitals, nursing homes, and through home nursing services.

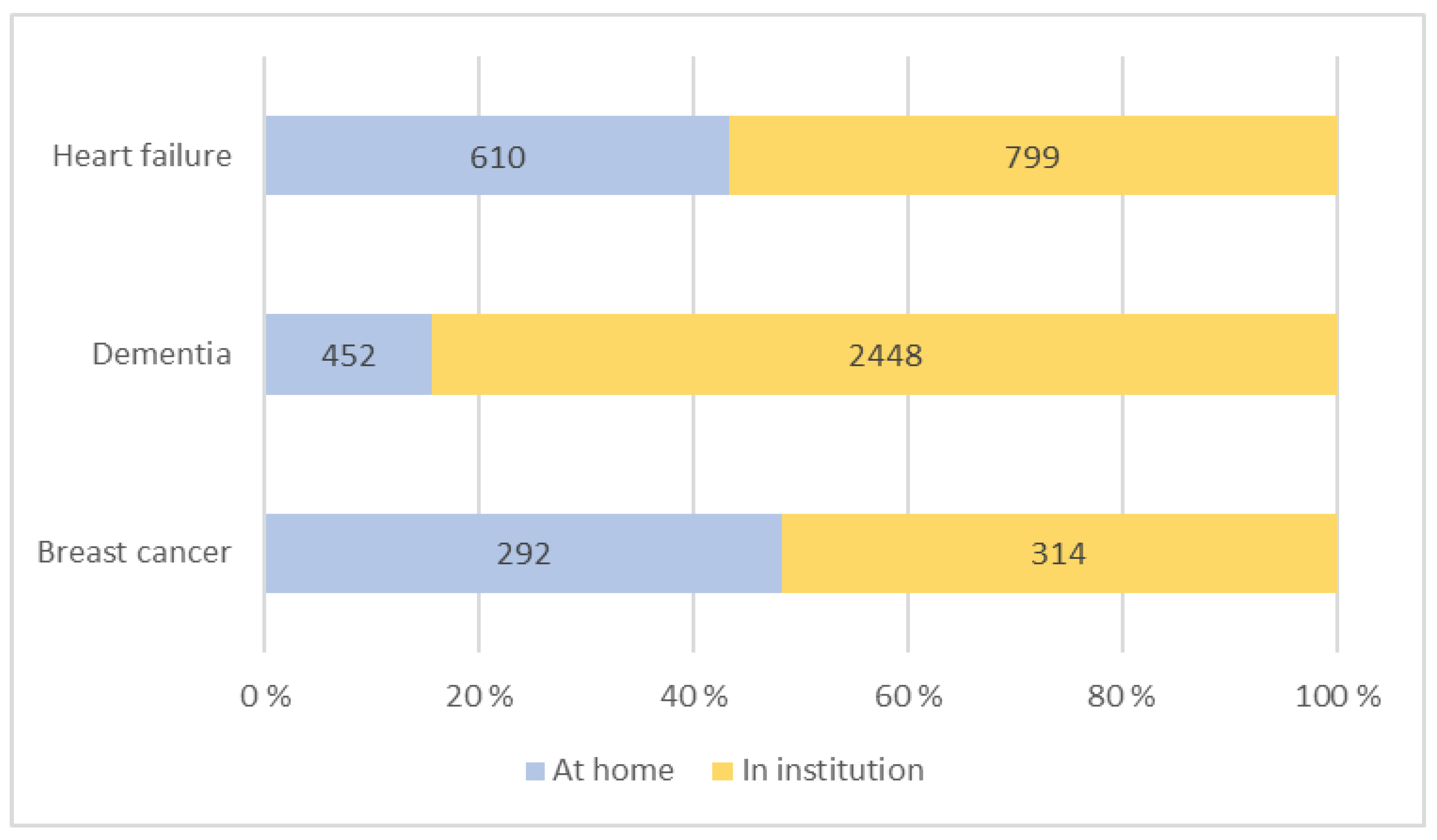

3.3. Factors Associated with Home Care at End-of-Life

The vast majority of patients (84%) who passed away from dementia did so in institutions (

Figure 2). Similarly, 57% of heart failure patients passed away in institutions. In contrast, for breast cancer patients, the distribution is almost equal, with 52% passing away in institutions and 48% at home.

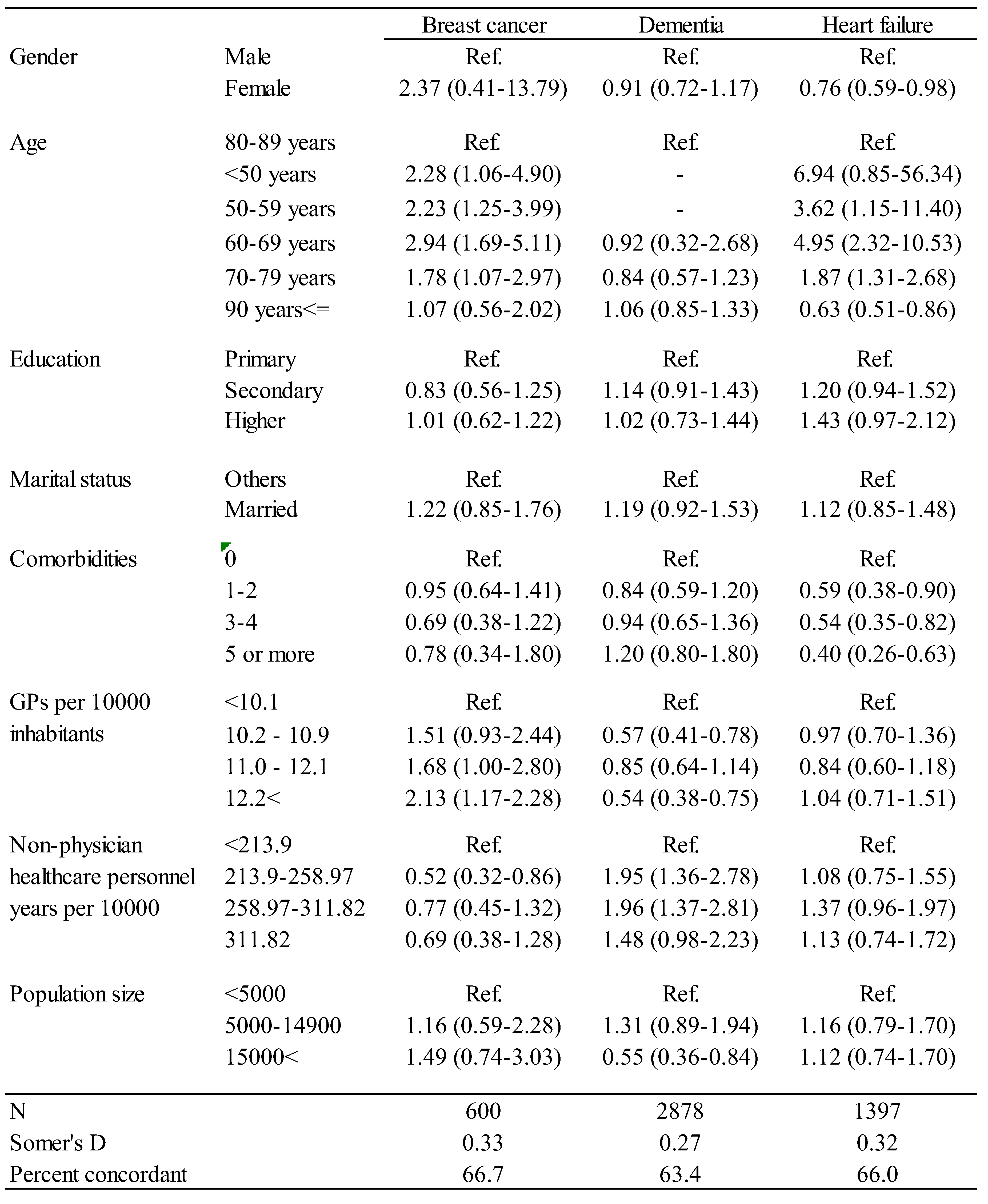

The associations between patient characteristics and place of care during the last day before death are presented in

Table 3. It is evident that, except for the dementia patients, strong associations exist between the variable describing age groups and staying at home on the last day of life, with the lowest age groups demonstrating significantly higher odds of staying at home compared to older age groups. While there are indications that the odds of staying at home on the last day of life increase with educational level, the relationship is only significant for the heart failure patients. Moreover, an increase in the number of comorbidities decreases the odds of staying at home, with significant effects observed for the heart failure patients.

The likelihood of cancer patients receiving end-of-life care at home is higher when there are more general practitioners available, while the likelihood of the other two patient groups receiving home care increases with the availability of non-physician healthcare workers. It is important to highlight that the notable disparities are observed between the group that has the least access to municipal care services and the other three categories. This implies that when access to care is severely restricted, patients are more inclined to spend their remaining days away from home.

4. Discussion

In our study, we evaluated the utilization of healthcare services over the last twelve months of life among patients with breast cancer, dementia, and heart failure. The most significant difference was observed in hospitalizations and long-term care in nursing homes. Patients with dementia were most frequently placed in nursing homes, while patients with heart failure and breast cancer patients were more frequently hospitalized. The breast cancer and heart failure patients had a higher likelihood of dying at home. Furthermore, the availability of general practitioners increased the probability of end-of-life care at home for cancer patients, while the availability of non-physician healthcare workers increased the likelihood of staying at home for the other two patient groups.

Our research findings aligned with those of other authors [

6,

22,

23]. Several studies note that dementia patients are less frequently hospitalized at EoL, and the frequency of hospitalizations also decreases for other elderly patients with chronic conditions and those where palliative needs were timely recognized [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Socioeconomic status and the availability of beds in nursing homes influence visits to emergency departments in the last year of life [

31]. The significance of nursing homes has been studied by Chu and colleagues, who assess that the accessibility of care in nursing homes significantly reduces rehospitalizations of dementia patients in the final stage of life [

26].

As indicated by the results of our study, patients with cancer and heart failure are more frequently hospitalized or treated in the emergency department in the last month of life, which typically entails higher treatment costs [

32,

33,

34,

35]. The utilization of healthcare services is influenced by numerous factors. Williamson describes the positive impact of education and socioeconomic status[

31]. We observed lower utilization of healthcare services among higher-educated patients with heart failure but not for other two groups of patients. Except for dementia patients, we observed that with higher age the use of health care services increase, firmed by numerous other researches [

24,

28,

29,

36,

37]. Comorbidity had a weak negative impact on the utilization of healthcare services in our study, a finding echoed by other authors [

29,

38,

39]. Some researchers emphasize the need to consider care pathways of patients when assessing factors influencing the utilization of healthcare services in the final months[

40]. Home-based palliative care and support are also associated with a greater likelihood of dying at home [

41,

42,

43,

44] a desire often expressed by many patients and their families [

45,

46,

47,

48]. Unfortunately, the frequency of palliative care for patients is lower than would be necessarily for enabling dying at home, especially for non-cancer patients [

39].

A strength of our analysis is the use of data registries that cover the whole Norwegian population. Our sample could have been larger by including a longer period for example 2019-2021. However, as the Covid-19 pandemic affected health care use we decided not to do so.

5. Conclusion

The utilization of healthcare services at the end of life (EoL) cannot be easily explained due to the complexity of situations and variables involving both patients and communities. Advanced care planning should encompass this complexity to facilitate a greater number of patients fulfilling their desire to pass away at home.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Erika Zelko; Methodology, Terje P. Hagen; Data curation, Terje P. Hagen; Writing – original draft, Terje P. Hagen and Erika Zelko; Writing – review & editing, Terje P. Hagen and Erika Zelko.

Institutional Review Board Statement

DPIA for the NORCHER project was granted March 30th, 2020, and ethical approval granted by the South-Eastern Regional Ethics Committee of Norway (ref. 170128) October 25th, 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to use of register data only.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the Norwegian Patient Registry, the Norwegian Registry for Primary Health Care and Statistics Norway have been used in this publication. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors, and no endorsement by the registry owners is intended nor should be inferred.

Acknowledgments

TPHs was partly funded by the Norwegian Research Council (NRC) through the Norwegian Centre for Health Services Research (NORCHER), NRC-grant number 296114.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Appendix A. Comorbidities

| Comorbidity |

ICD-10 codes |

| Stroke |

I60-I66, I68-I69, G45 |

| Dementia |

F00-F03, G30 |

| Hypertension |

I10-I15 |

| Coronary artery disease |

I20-I25 |

| Atrial fibrillation |

I48 |

| Cardiac insufficiency |

I50 |

| Diabetes mellitus |

E10-E14 |

| Atherosclerosis |

I70 |

| Cancer |

C, D0 |

| COPD and asthma |

J44-J46 |

| Depression |

F32-F34 |

| Parkinson’s disease |

G20 |

| Mental disorders |

F2, F30-F31 |

| Renal insufficiency |

N18 |

| Alcoholism |

F10-F19 |

References

- Lee, J.H.; Hwang, K.K. End-of-Life Care for End-stage Heart Failure Patients. Korean Circ J 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill L, P.G.T. , Baruah R, et al. Integration of a palliative approach into heart fail. Eur J Heart Fai 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, B.; Song, Y.; Chang, L.; Tan, B. Effects of early palliative care on patients with incurable cancer: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2022, 31, e13620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott CL, E.R. , Khandelwal N, Steiner JM, Feemster LC, Sibley J, Lober WB, Curtis JR. The Association of Advance Care Planning Documentation and End-of-Life Healthcare Use Among Patients With Multimorbidity. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. he Association of Advance Care Planning Documentation and End-of-Life Healthcare Use Among Patients With Multimorbidity. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- care, P. p. https://www.who.int>health-topics.

- Depoorter V, V.K. , Decoster L, Silversmit G, Debruyne PR, De Groof I, Bron D, Cornélis F, Luce S, Focan C, et al.. End-of-Life Care in the Last Three Months before Death in Older Patients with Cancer in Belgium: A Large Retrospective Cohort S. 2023.

- Saunes, I.S.; Karanikolos, M.; Sagan, A. Norway: Health System Review. Health Syst Transit 2020, 22, 1–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johansen, M.L.; Ervik, B. Talking together in rural palliative care: a qualitative study of interprofessional collaboration in Norway. BMC Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KAGes, S. , Koordination, Palliativbetreuung, Steiermark. Sterbeorte Österreich 2020 [cited 2024 26.01.2024]. 2020. p. https://www.hospiz.at/hospiz-palliative-care/sterben-in-oesterreich-zahlen-und-fakten/.

- Croatian, B. , of, Statistics. Natural Change in Population, 2022 2024 [cited 2024 29.01.2024].. 2022.

- National, I. , for, Health, Protection. Places of deaths in Slovenia. 2022.

- Abba K, L.-W.M. , Horton S. Discussing end of life wishes–the impact of community interventions? BMC Palliative Care 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rainsford, S.; Glasgow, N.J.; MacLeod, R.D.; Neeman, T.; Phillips, C.B.; Wiles, R.B. Place of death in the Snowy Monaro region of New South Wales: A study of residents who died of a condition amenable to palliative care. Aust J Rural Health 2018, 26, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen J; Houttekier D, O. -P.B., Miccinesi G, Addington-Hall J, Kaasa S, et al.. Which patients with cancer die at home? A study of six European countries using death certificate data. J Clin Oncol. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kjellstadli, C.; Allore, H.; Husebo, B.S.; Flo, E.; Sandvik, H.; Hunskaar, S. General practitioners' provision of end-of-life care and associations with dying at home: a registry-based longitudinal study. Fam Pract 2020, 37, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes B, C.N. , Koffman J, Higginson IJ. Is dying in hospital better than home in incurable cancer and what factors influence this? BMC medicine. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- A., K. A., K. Compassionate communities: end-of-life care as everyone’s responsibility. 2013.

- Koroukian, S.M.D., S. L. ; Vu, L.; al., e. Incidence of Aggressive End-of-Life Care Among Older Adults With Metastatic Cancer Living in Nursing Homes and Community Settings. 2023.

- Luta, X.; Diernberger, K.; Bowden, J.; Droney, J.; Hall, P.; Marti, J. Intensity of care in cancer patients in the last year of life: a retrospective data linkage study. Br J Cancer 2022, 127, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Shen, C.; Van Scoy, L.J.; Boltz, M.; Joshi, M.; Wang, L. End-of-Life Costs of Cancer Patients With Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022, 64, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leniz J, Y.D. , Yorganci E, Williamson LE, Suji T, Cripps R, Higginson IJ, Sleeman KE. Exploring costs, cost components, and associated factors among people with dementia approaching the end of life: A systematic review. 2021.

- O'Connor N, F.S. , Kernohan WG, Drennan J, Guerin S, Murphy A, Timmons S. A scoping review of the evidence for community-based dementia palliative care services and their related service activities. 2022.

- van der Steen JT, L.D.N. , Gijsberts MHE, Vermeulen LH, Mahler MM,. The BA. Palliative care for people with dementia in the terminal phase: a mixed-methods qualitative study to inform service development. 2017.

- Nothelle, S.; Kelley, A.S.; Zhang, T.; Roth, D.L.; Wolff, J.L.; Boyd, C. Fragmentation of care in the last year of life: Does dementia status matter? J Am Geriatr Soc 2022, 70, 2320–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diernberger, K.; Luta, X.; Bowden, J.; Fallon, M.; Droney, J.; Lemmon, E.; Gray, E.; Marti, J.; Hall, P. Healthcare use and costs in the last year of life: a national population data linkage study. BMJ Support Palliat Care, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.P.; Huang, C.Y.; Kuo, C.J.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, C.T.; Yang, T.W.; Liu, H.C. Palliative care for nursing home patients with dementia: service evaluation and risk factors of mortality. BMC Palliat Care 2020, 19, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leniz J, H.I. , Yi D, Ul-Haq Z, Lucas A, Sleeman KE. Identification of palliative care needs among people with dementia and its association with acute hospital care and community service use at the end-of-life: A retrospective cohort study using li. 2021.

- Ni Chroinin, D.; Goldsbury, D.E.; Beveridge, A.; Davidson, P.M.; Girgis, A.; Ingham, N.; Phillips, J.L.; Wilkinson, A.M.; Ingham, J.M.; O'Connell, D.L. Health-services utilisation amongst older persons during the last year of life: a population-based study. BMC Geriatr 2018, 18, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.; Chen, C.; Ho, S.; Hooi, B.; Chin, L.S.; Merchant, R.A. Healthcare utilisation in the last year of life in internal medicine, young-old versus old-old. BMC Geriatr 2020, 20, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nze Ossima, A.; Szfetel, D.; Denoyel, B.; Beloucif, O.; Texereau, J.; Champion, L.; Vie, J.F.; Durand-Zaleski, I. End-of life medical spending and care pathways in the last 12 months of life: A comprehensive analysis of the national claims database in France. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023, 102, e34555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, L.E.; Leniz, J.; Chukwusa, E.; Evans, C.J.; Sleeman, K.E. A population-based retrospective cohort study of end-of-life emergency department visits by people with dementia: multilevel modelling of individual- and service-level factors using linked data. Age Ageing 2023, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.E.; Olsen, M.K.; McDermott, C.L.; Bowling, C.B.; Hastings, S.N.; White, T.; Casarett, D. Factors associated with hospital admission in the last month: A retrospective single center analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado-Tineo, J.P.; Oscanoa-Espinoza, T.; Vasquez-Alva, R.; Huari-Pastrana, R.; Delgado-Guay, M.O. Emergency Department Use by Terminally Ill Patients: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021, 61, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, R. , Srasuebkul, P., Langton, J.M. et al. Health care use and costs at the end of life: a comparison of elderly Australian decedents with and without a cancer history. 2018.

- Langton, J.M.; Reeve, R.; Srasuebkul, P.; Haas, M.; Viney, R.; Currow, D.; Pearson, S.A. Health service use and costs in the last 6 months of life in elderly decedents with a history of cancer: a comprehensive analysis from a health payer perspective. Br J Cancer 2016, 114, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlay, S.M.; Redfield, M.M.; Jiang, R.; Weston, S.A.; Roger, V.L. Care in the last year of life for community patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2015, 8, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, P.; Roe, L.; McGarrigle, C.A.; Kenny, R.A.; Normand, C. End-of-life experience for older adults in Ireland: results from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing (TILDA). BMC Health Serv Res 2020, 20, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.; Normand, C.; Cassel, J.B.; Del Fabbro, E.; Fine, R.L.; Menz, R.; Morrison, C.A.; Penrod, J.D.; Robinson, C.; Morrison, R.S. Economics of Palliative Care for Hospitalized Adults With Serious Illness: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2018, 178, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.; Pasman, H.R.; Donker, G.A.; Deliens, L.; Van den Block, L.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.; on behalf of, E. End-of-life care in general practice: A cross-sectional, retrospective survey of 'cancer', 'organ failure' and 'old-age/dementia' patients. Palliat Med 2014, 28, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnelv, G. , Hagen, T.P., Forma, L. et al. Care pathways at end-of-life for cancer decedents: registry based analyses of the living situation, healthcare utilization and costs for all cancer decedents in Norway in 2009-2013 during their last 6 months of 2022.

- Quinn, K.L. , Hsu, A. T., Smith, G., Stall, N., Detsky, A. S., Kavalieratos, D.,... & Tanuseputro, P. Association between palliative care and death at home in adults with heart failure. 2020.

- van der Plas, A.G.; Oosterveld-Vlug, M.G.; Pasman, H.R.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D. Relating cause of death with place of care and healthcare costs in the last year of life for patients who died from cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure and dementia: A descriptive study using registry data. Palliat Med 2017, 31, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn KL, H.A. , Smith G, Stall N, Detsky AS, Kavalieratos D, Lee DS, Bell CM, Tanuseputro P. Association Between Palliative Care and Death at Home in Adults With Heart Failure. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn KL, S.T. , Campos E, Graham C, Kavalieratos D, Mak S, Steinberg L, Tanuseputro P, Tuna M, Isenberg SR. Regional collaborative home-based palliative care and health care outcomes among adults with heart failure. 2022.

- Spary-Kainz, U.; Posch, N.; Paier-Abuzahra, M.; Lieb, M.; Avian, A.; Zelko, E.; Siebenhofer, A. Palliative Care Survey: Awareness, Knowledge and Views of the Styrian Population in Austria. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelko, E.; Ramsak Pajk, J.; Skvarc, N.K. An Innovative Approach for Improving Information Exchange between Palliative Care Providers in Slovenian Primary Health-A Qualitative Analysis of Testing a New Tool. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benini, F.; Fabris, M.; Pace, D.S.; Verno, V.; Negro, V.; De Conno, F.; Orzalesi, M.M. Awareness, understanding and attitudes of Italians regarding palliative care. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2011, 47, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, C.; Tishelman, C.; Benkel, I.; Furst, C.J.; Molander, U.; Rasmussen, B.H.; Sauter, S.; Lindqvist, O. Public awareness of palliative care in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 2018, 46, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).