1. Introduction

Dating back before the establishment of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) in 1999, performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) have been a major concern in sports from the lowest to the highest level of competition [

1,

2]. The use of these substances, as defined and listed in the WADA code, is a direct threat to the ideal of fair competition and the overall integrity of sports, while potentially risking both physical and mental health of its users [

3,

4]. However, traditional anti-doping policies have been primarily based on detection and punishment, which has failed to solve the problems arising from doping in competitive sports, suggesting for the development and implementation of new and improved approaches [

5,

6].

It is understood that the factors behind the decision to dope are complex and comprise environmental, social and psychological aspects [

7,

8,

9], thus, requiring different angles of investigation and inquiry in order to better understand and deal with this phenomenon. In this sense, research on the psychosocial determinants of doping behavior in sports is growing, having the attitudes toward doping at its core [

6]. Such construct of doping attitudes has been measured and studied as a set of one’s values, views and beliefs regarding doping and it has been considered a direct predictor of doping susceptibility and behavior [

10,

11].

Developed in 2002, the Performance Enhancing Attitude Scale (PEAS) [

12,

13] is currently the most widely adopted psychometric measurement of doping attitudes in international sports literature [

6], with higher scores represent and more lenient, or favorable, attitude towards doping. Such scale has even been used in six WADA-funded research projects across Europe, Africa and Australia [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of the PEAS [

6] found a total of 82 studies adopting this tool, moreover, this review revealed a total of 10 different versions of the PEAS available across over 15 languages.

Despite its worldwide adoption, research using the PEAS have been most predominant in European countries (53.7%), with some contributions from Asia (22%), Oceania (8.5%), Africa (7.3%), North America (6.1%) and multinational samples (2.4%), however, no PEAS research on doping attitudes was found with South American samples [

6]. Analysis of other systematic reviews of the doping psychosocial literature [

10,

20,

21,

22,

23] revealed no studies from South America as well. Furthermore, manual searches performed on February of 2024 for the terms “doping”, “performance enhancing drugs” and “performance enhancing substances” on the main South American research database (SCIELO) revealed no psychological study of doping published within Brazilian journals, with most publications being focused on consequences of PED use, descriptive informative data and narrative reviews. In this sense, research in South American countries can provide insights as to the validity of the PEAS in a different cultural setting.

Therefore, it is possible to observe a cultural gap in the evidence for psychosocial factors related to doping attitudes in sports, which is absent in South America, along with a limitation to the application of the PEAS in the Portuguese language. In order to fill the cultural continental gap in the doping attitude literature as well as to unlock the adoption of the PEAS for Portuguese-speaking individuals, the present study sought to translate and adapt the original 17-item version of the PEAS from English to Brazilian Portuguese and test its psychometric properties in a sample of Brazilian athletes. Present research could provide the foundations to build capacity and further advance both psychological and social science research on doping in Brazil and other Portuguese-speaking nations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Performance Enhancement Attitude Scale (PEAS)

The original scale in English [

13] comprises 17 items to assess athletes’ attitudes towards the use of prohibited performance-enhancing drugs, these 17 items came from an original poll of 97 items which sought to represent 26 specific topics related to performance-enhancement in sports, such as hypocrisy, knowledge, known health risks, different forms of pressure, sports culture, regulations, unfair advantages, success, injuries and others. Despite the heterogeneity of items across varied subjects, the 17 items represent a unidimensional measurement of attitudes towards PEDs. Statements are answered in a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1-Strongly disagree to 6-Strongly agree and are scored as the total sum of items and a possible score ranging from 17 to 102 points, where higher scores suggest a more lenient or favorable attitude towards PEDs.

2.2. Evidence Based on the Content of the Scale

This step followed the recommendations of Pasqualli [

24]. Four experts with doctorate degrees in psychology and/or physical education, native Portuguese speakers and fluent in the English language participated in the translation (English->Portuguese) and back-translation (Portuguese->English) processes. Two experts independently translated the original scale from English to Brazilian Portuguese and these two versions were analyzed by the authors in order to produce a first version of the scale in Portuguese. The first version was then translated back to English by the remaining two experts, who worked independently.

After analyzing the agreement between each version and performing minor improvements, a new version in Portuguese was generated and presented to a small group of 20 young swimming athletes from the city of Maringá, south of Brazil, as a pilot study to obtain feedback on the response process. Suggestions were made by the athletes in order to improve comprehension. Finally, the final version of the PEAS in Brazilian Portuguese was ready for further testing, and can be referred to as “Escala de Atitudes para Melhoria de Rendimento” (EAMR) in Portuguese.

Four other individuals, experts in the field of Sports Psychology, evaluated the EAMR according to its language clarity, theoretical relevance and practical pertinence, items were rated in a scale of 1 (no clarity/relevance) to 5 (very clear/relevant). Responses from each evaluator we averaged to compose the Content Validity Coefficient (CVC), for which values above 0.80 are considered adequate. These experts also provided feedback and suggestions for minor adjustments.

2.3. Evidence Based on the Response Process, Internal Structure and Reliability of the Scale

2.3.1. Sample Characteristics

For this following step, a total of 1035 Brazilian athletes participated in the study by answering the Portuguese-PEAS by pen and paper, however, 37 subjects were excluded for being aged under 18 and other 04 responses were excluded due to the incorrect filling of the questionnaires. Thus, final sample comprised 994 athletes with an average age of 22.79±4.87 years, being 559 (56%) males and 435 (44%) females, who competed in a variety of individual (N=495, 49.7%) and team (N=499, 50.3%) sports. Highest competitive experience of athletes varied from state/provincial (14.9%), national collegiate (31.9%), national (26%) and international (27.2%) levels.

2.4. Procedures

The process of gathering data took place during two different competitions: the 2018 Paraná Open Games, a state level competition, and the 2018 Brazilian College Games, the main national collegiate level event, which were both held at the State of Paraná, South Region of Brazil. Prior to the events, an authorization was obtained from the Sports Secretary of Paraná and the Brazilian Confederation of College Sports (CBDU). Athletes were approached at either the competition sites or their respective housing, according to the athlete’s availability. All participants voluntarily agreed to take part in the present research by reading and signing an Informed Consent Term. Researchers and assistants were available to solve any questions or doubts during questionnaires’ filling with were done in person on pen & paper.

2.5. Data Analysis

All of the following analysis were performed using MS Excel, R package and RStudio, packages used were readxl, xlsx, mice, psych, MVN, lavaan, qgraph, Hmisc, corrplot, polycor and semPlot. As previously described, 04 subjects were excluded from the final sample due to incorrectly filling of the instruments, however, a few supposedly-random missing cases were still present and were kept in the dataset. These missing cases were imputed through the MICE algorithm (Multiple Imputation Chained Equations). Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, quartiles and frequency) were used for sample characteristics and to assess items’ response patterns. Data univariate normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which revealed a non-parametric distribution. Multivariate normality was assessed by the Mardia test, revealing a non-parametric multivariate distribution. Due to the ordinal nature of Likert scales, item-to-item correlations were calculated using Polychoric correlation, while Polyserial correlations were applied between item and scale total score.

To test the internal structure of the Brazilian PEAS, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) were conducted with the WLSMV estimation method. The following fit indices were used to assess model adequacy: Adjusted Chi-Squared (X2/df < 3.00), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > 0.95), Comparative Fit Index (CFI > 0.95), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < 0.08) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR < 0.08) [

25]. The Average Variance Extracted was also assessed, for which values of AVE > 0.5 can be considered a satisfactory indicator of construct validity [

26,

27]. Items’ internal consistency was verified using the Cronbach’s Alpha (α > 0.7), McDonald’s Omega (ω > 0.7) and Composite Reliability (CR > 0.7) methods [

28].

In line with the complexity of the doping phenomena, a last and innovative step was performed to provide another look at the scale’s internal structure, a Network Analysis. For this matter, Spearman correlations were performed in order to create a correlation matrix, this matrix is then used by the network and the LASSO algorithm to calculate and plot a visual network of partial correlations between variables. The Least-Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) forces potentially trivial and spurious correlations to zero and returns a network with only the strongest associations [

29]. This method is data-driven and will provide a contrast to the theory, by producing a sparse network we minimize the likelihood of finding false positives.

The network is composed by nodes (circles) representing variables, which are connected by lines. The color and width of such lines also reflect the direction (positive/negative) and strength (r) of associations, furthermore, node positioning is also calculated by the algorithm to reflect the interaction between nodes and how information travels through the network [

30]. The threshold for the network was set as ‘TRUE’ and the regularization parameter lambda was set to high (λ = 0.5). To provide more information about the network and its most relevant nodes, the Network Centrality Indices (Strenght, Closeness and Betweenness) were also calculated.

3. Results

3.1. Evidence Based on the Content of the Scale

Table 1 presents the final writing of each item in Portuguese as well as its respective original item in English, alongside the CVC for each item in Portuguese, as assessed by four independent experts. The CVCi represents the items’ average score of each criterion (i.e., language clarity, theoretical relevance and practical pertinence). All of the items showed adequate scores (CVCi > 0.80) with the exception of item 10 (CVCi = 0.56), which was retained for further analysis for not compromising the overall instrument (CVCtotal = 0.90). This question was also a source of doubts for some participants during data gathering, reflecting that its content might need to be better adapted to the Portuguese language in order to convey the same original meaning with clarity.

3.2. Evidence Based on the Response Process

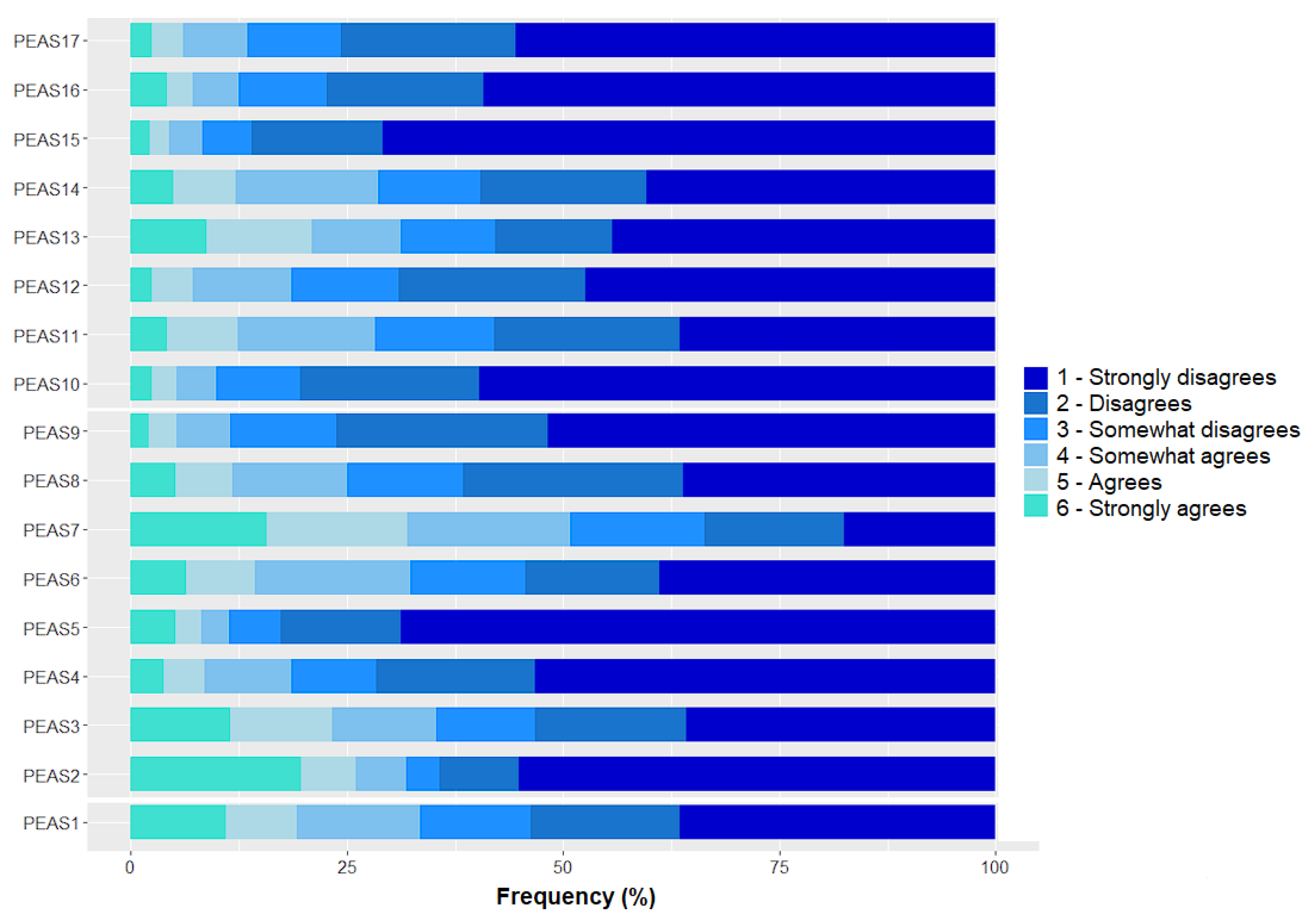

Frequency of item responses (

Figure 1) showed a clear predominance of scores ranging between 1 (strongly disagree) and 3 (somewhat disagree), meaning that the majority of the sample disagrees with the statements being presented and, thus, have a negative attitude towards doping. In this sense, it is possible to highlight items 5 (“Athletes should not feel guilty about breaking the rules and taking performance enhancing drugs.”) and 15 (“Doping is not cheating since everyone does it.”) as the most disagreed upon. In simpler terms, the present sample mostly agreed that athletes should feel guilty for breaking the rules and that doping is in fact cheating, whether or not others opt to do it, which suggests the involvement of morals or sports ethics as factors that could keep these athletes away from doping.

On the other hand, item 7 (“Health problems related to rigorous training and injuries are just as bad as from doping”) divided the sample, with about 50% agreeing or disagreeing to some degree with this statement. Such a result might suggest a possible entry door for athletes who are already sacrificing some of their health in exchange for performance and are either willing to go further, or those who are looking for a compensation due to the time lost while injured. Item 2 presented the higher frequency of extreme responses, with almost a quarter of the sample strongly agreeing that “Doping is necessary to be competitive”.

3.3. Evidence Based on the Internal Structure and Reliability of the Scale

Diving further into the scale’s characteristics,

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix of items and the single dimension of doping attitudes. The majority of item-item correlations ranged between r = 0.15 to 0.50, which is desirable in order to avoid possibly redundant items (r > 0.50) or items that do not share their variance with the remaining items within the same dimension or factor (r < 0.15). Item 6 (“Athletes are pressured to take performance-enhancing drugs”) was the most independent item, sharing mostly weak item-item correlations and the smallest item-total correlation. Meanwhile, item 15 (“Doping is not cheating since everyone does it”) presented the higher item-total correlation (r = 0.79), followed by items 4 (recreational drugs) and 8 (media exaggeration) (r = 0.71).

For the next step of analysis, a CFA model was tested with direct paths between a single latent factor representing doping attitudes and each of the 17 items (Model 1). Overall, this first model did not perform poorly, however, acceptable fit was not achieved due to high adjusted chi-squared (>3.00) and low CFI and TLI (<0.95) [X2/df = 4.54; p <0.01; RMSEA = 0.06 (0.055-0.065); p-RMSEA < 0.01; CFI = 0.84; TLI = 0.82; SRMR = 0.057].

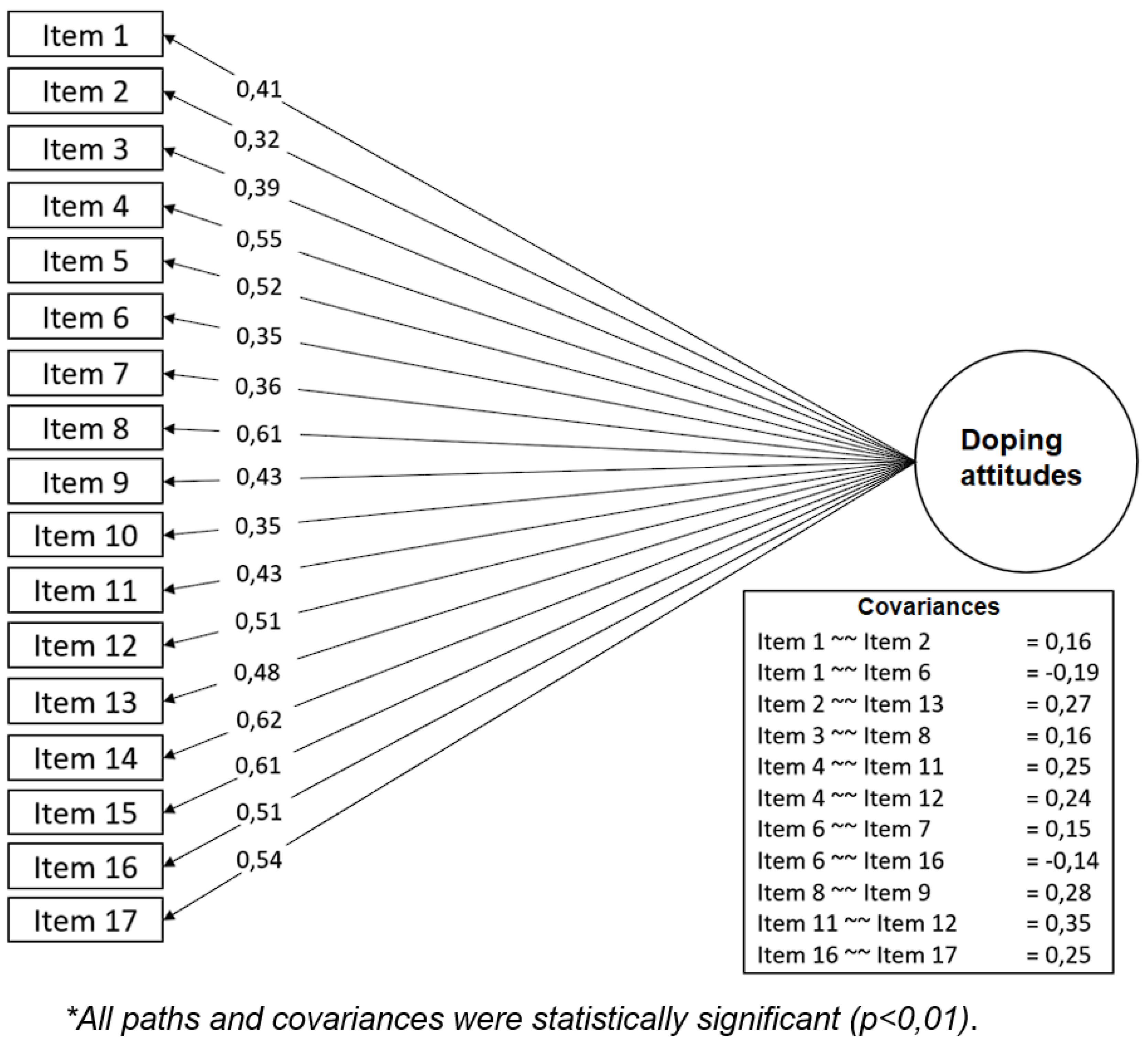

In order to achieve the desired model fit indices, further steps of analysis were conducted by adding covariances between items according to the suggested modification indices, which will be summed up to the final model. A total of 11 covariances were added, for instance, between statements on recreational drugs (items 4, 10, 11 and 12), media opinion (items 8 and 9), need or unavoidability of doping (items 2 and 3), underestimation of doping-related health problems (items 3 and 8), among others. The final model (

Figure 2) presented acceptable fit and good evidence of construct validity [X2/df = 2.04; p <0.01; RMSEA = 0.032 (0.026-0.038); p-RMSEA = 1.00; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.035].

We opted for the route of allowing covariances instead of excluding items because a few factors suggested that each item had its contribution to the overall factor, since factor loadings were all close or greater than 0.40, the standardized residuals were low (<2) (Mullan et al., 1997), expected change > 0.25 according to the modification indices, and all items retained factor loadings’ significant p-values (z-score > 1.96) (Brown, 2015). Besides, previous analysis (

Table 2) did not point towards strong collinearity of items. Since there is still no consensus regarding a single short-version for this scale [

6], preserving items and their respective information seemed reasonable for now, raising the need for further investigation to determine if there is a consensus for a short-form of the PEAS in Brazilian Portuguese.

Reliability indicators were all satisfactory (> 0.80), according to Cronbach’s alfa (α = 0.83 [0.81-0.84]), McDonald’s Omega (ω = 0.84), and Composite Reliability (CR = 0.83). However, only 23% of the average variance of the scale was explained (AVE = 0.23), which falls bellow the desired value of 0.50. A possible explanation for this result might be the complex and multifactorial nature of the investigated phenomenon, for which single items will hardly ever be able to explain high amounts of variance, and attest for the difficulty of trying to estimate and predict one’s attitudes to dope.

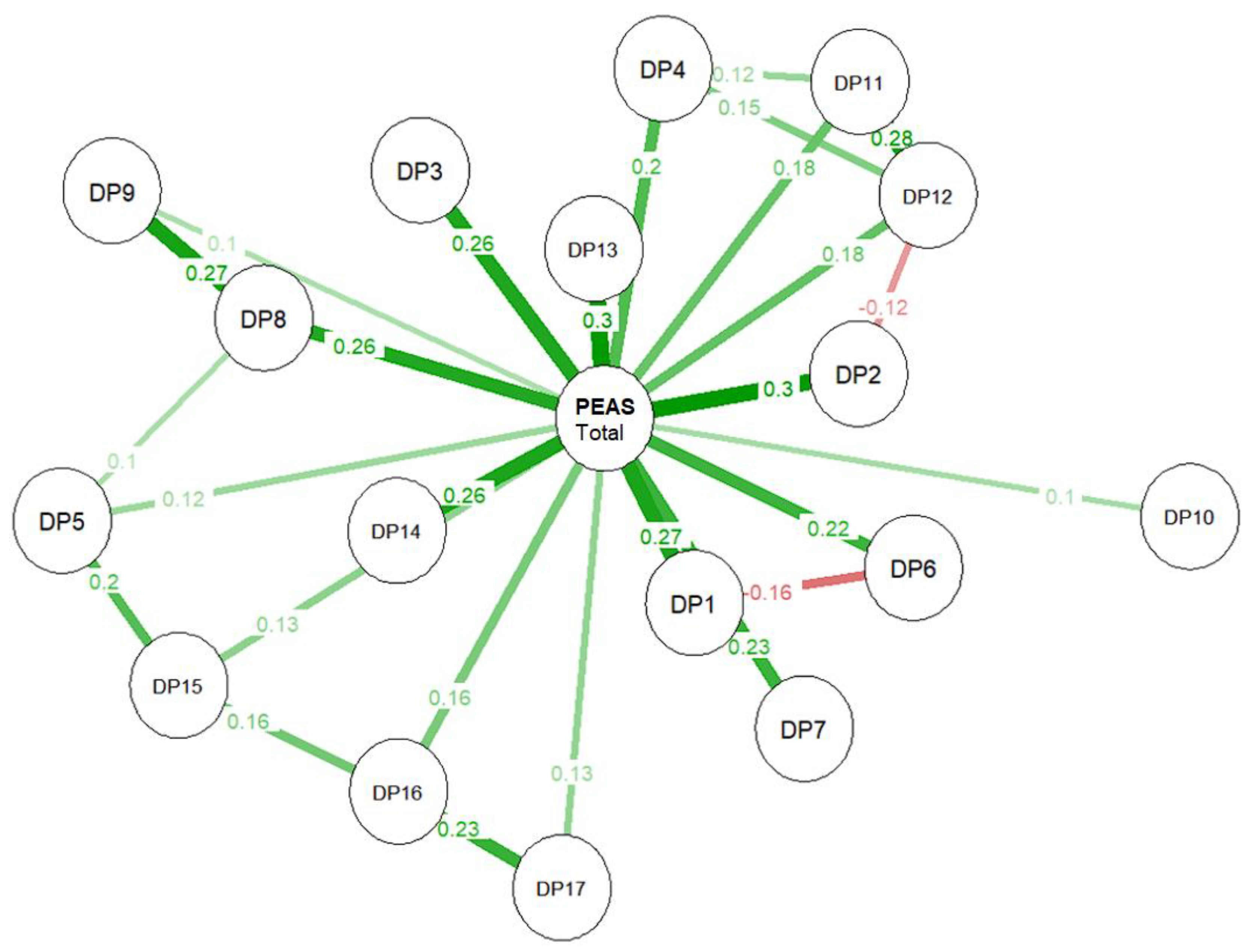

The network analysis results (

Figure 3) supported the findings from the CFA model. Total score on PEAS was positioned at the center of the network with all items distributed across all directions with no significant clustering of items. This structure also shows that all items had a direct connection to the main construct of doping attitudes and despite a series of associations between items, no second structure or dimension emerged, reinforcing the scale’s unidimensional characteristic. Similar to the CFA model, items interacted with each other but were still better explained by the single latent factor of doping attitudes. Another similarity was the low strength of associations (r ≤ 0.30), as evidenced through the AVE result.

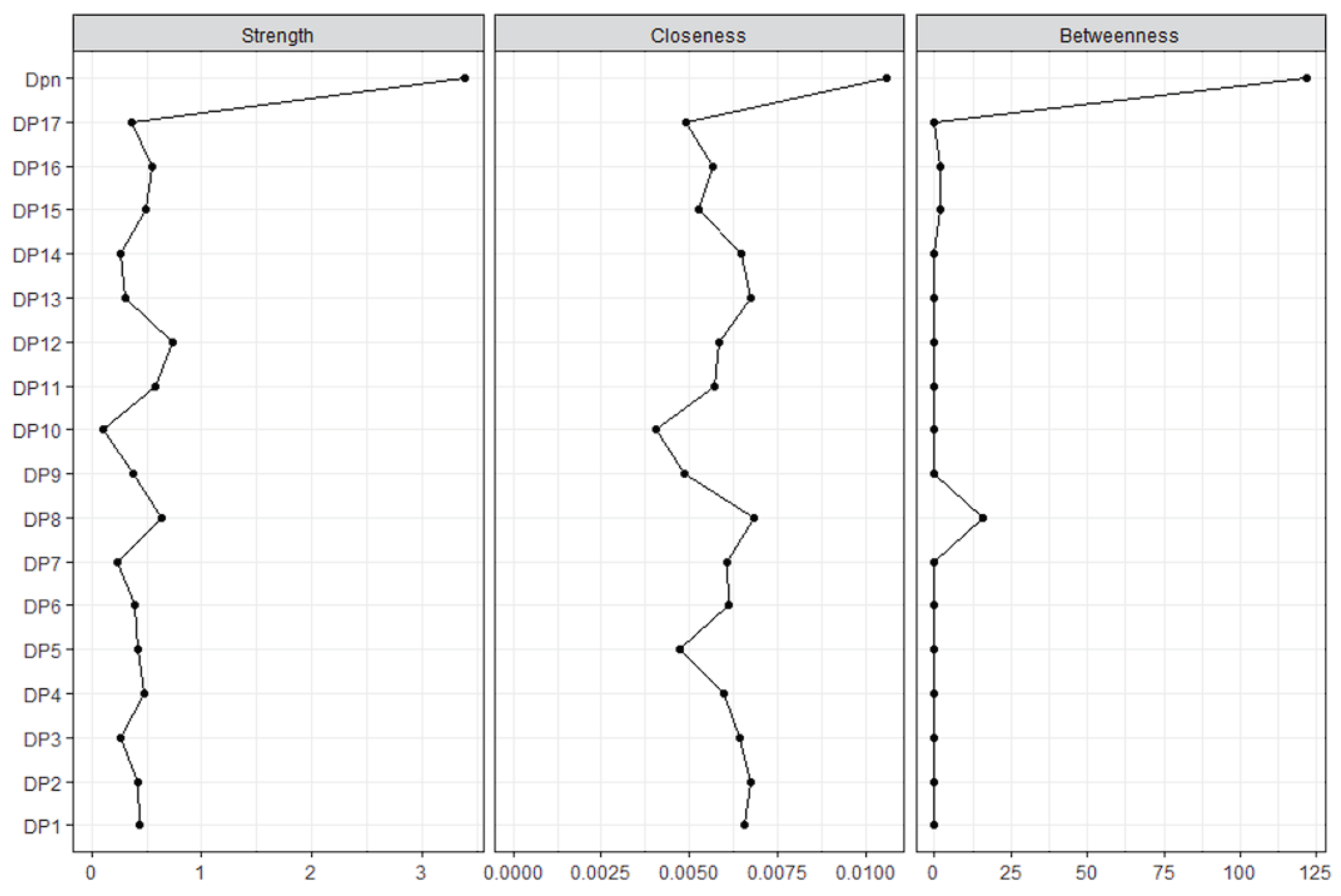

Network centrality indices (

Figure 4) aid in finding the most influential or important nodes within a complex network. Items 8, 11 and 12 presented the higher degrees of strength of associations, however, only item 8 acted as a bridge connecting a few other nodes. Moreover, all other nodes had zero degrees of betweenness, reinforcing their single and direct connection to the main construct of doping attitudes. Levels of closeness were overall low and similar between nodes. Due to its levels of closeness and between being among the top and being the only item node with some degree of betweenness, results suggest that item 8 is the most influential node in the network, a part from the total score of doping attitudes.

3.4. Measurement Invariance

Based on the final CFA model (

Figure 2), two other series of CFA were performed in order to test measurement invariance between males and females (Invariance Model 1 – Sex) and between athletes from individual and team sports (Invariance Model 2 – Sport type). The compound results of all invariance models are shown in

Table 3. The PEAS reached the highest degree of model invariance (full uniqueness) for both sex and sport type, meaning that the scale’s configural structure, loadings, intercepts and residuals did not vary according to the athletes’ sex or type of sport.

4. Discussion

The present investigation aimed to perform a transcultural adaptation of the PEAS to the context of Brazilian sports, providing evidences of validity based on the content, reliability and internal structure of the scale. Despite being the most widely adopted tool to assess doping attitudes in psychological and social research, and already being available in many languages, this was the first work to translate and adapt the PEAS to Portuguese. In this sense, the present study fills a major gap in psychological doping inquiry by making this important psychometric tool available to Brazilian and other Portuguese-speaking researchers and those who work with sports, besides being the first study to bring evidences from the PEAS in a South American sample.

Overall, the scale presented satisfactory indices in all steps of the process. The committee of experts found that items in the Brazilian Portuguese version of the scale have clear language, theoretical relevance and practical pertinence (CVC = 0.90). Correlations between items and item-dimension were, for the most part, low to moderate (r = 0.15 to 0.50) which suggest that items are somewhat related but with no significant levels of collinearity or existence of a second factor, possibly highlighting the unique contribution of each statement in the scale. The final CFA model, allowing for 11 covariances, presented excellent fit [X2/df = 2.04; p <0.01; RMSEA = 0.032 (0.026-0.038); p-RMSEA = 1.00; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.035]. All three reliability indicators showed satisfactory values as well (α, ω, and CR > 0.8). Network analysis provided further support for the PEAS internal consistency and reliability by having a data-driven multivariate representation of the scale’s item dynamics.

This was the first study to apply network analysis to study the PEAS’s content and structure, such method is still not common in psychometric or even exploratory research in sports sciences, however, it is a powerful tool to analyzed complex relationships, patterns, visualize data and reveal core features of a complex system which can offer great application for psychological inquiry [

31]. Interestingly, results from network analysis provided support for the factor structure found through CFA that added covariances instead of excluding items, as 09 item-item associations emerged on a network with a single factor, where each item was directly and mainly connected to the overall attitude dimension, showing items’ uniqueness and individual contribution, as well as a high degree of covariances between items.

In the present study we opted to maximize item retention in the CFA model due to the sufficient strength of factor loadings (close to or above 0.40), low standardized residuals (<2), sufficient expected change according to the modification indices (> 0.25) and factor loadings’ significant p-values (z-score > 1.96) [

32,

33]. This approach was also observed in the French validation study [

34] which also included a high number of covariances, 08 in total, as opposed to excluding items.

While the Spanish version of the scale also maintained all 17 items, adding only 03 covariances for the larger sample, it is important to mention that authors in this study only used normalized Chi-Square and RMSEA fit indices to state that the scale had adequate fit without the need for further inclusion of covariances [

35], while CFI and TLI, the main reason for model adjustments in the present study, where not presented. Moreover, Persian versions of the scale were found with 09 [

36] and 14 items [

37]. The German version of PEAS by Elbe & Brand [38] included only 06 items, and the Polish version had 11 items [39].

It is possible to observe a tendency to exclude PEAS items and aim for shorter versions. The number of items in the PEAS is still a subject of debate, as no consensus has been found between authors, the systematic review of the PEAS by Folkerts et al. [

6] revealed ten different and shorter versions of the scale with no single item from the original scale being present in all other versions. These authors even suggest that a revised short-version of the scale is needed for a “master version” to be used consistently across investigations. Based on present findings and the psychometric literature for PEAS, we suggest that original studies should always start with the complete 17-item version. Nevertheless, the complete version with all 17 items is still the most adopted one [

6], which can then be refined through further data analysis.

Considering the complexity of doping as a whole, which encompasses an immeasurable interaction between individual and sociocultural factors which can play a role in an athlete’s decision to dope or stay clean, it is not so difficult to understand why so much contrast present in the literature. Such complexity factor might also be responsible for the lower-than-ideal values of AVE reported in the present findings. Moreover, it is possible that this is first study to even report values of AVE for this scale.

Despite all of the controversy present in the literature, our findings are enough to support and recommend the adoption of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the PEAS here proposed. The majority of problems and inconsistencies found across the wide range of PEAS versions might reflect the complex nature of the doping phenomena itself rather than major problems with the scale and its statements.

Still, some limitations are worth mentioning: by seeking to validate an instrument for the overall Brazilian population, a heterogenous sample was adopted and included individuals from all regions of the country across a variety of sports, which limits our understanding of specificities related to doping attitudes. However, the measurement invariance models suggest that the goal of producing a scale for the broader population of Brazilian athletes might have been achieved, at least for sex and type of sport. Since this is the first study to analyze the psychometric properties of the PEAS for this language, comparisons to further compare and discuss the adoption, exclusion or rewriting of items was also limited.

Future investigations should carry on the continuous process of scale validation and refinement by providing more evidences of validity across other sports populations in Brazil as well as other Portuguese-speaking countries. Further analysis should include correlate variables in order to assess external validity and provide psychological evidence of doping attitudes in Brazil, since there is an absolute absence of studies on this specific topic in the entirety of South American journals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C. and L.F.; methodology, R.C. and L.F.; software, R.C.; validation, P.V.S.A. and E.B.; formal analysis, R.C. and E.B.; investigation, R.C. and P.V.S.A.; resources, R.C. and L.F.; data curation, P.V.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C., P.V.S.A. and E.B.; writing—review and editing, R.C. and L.F.; visualization, E.B.; supervision, L.F.; project administration, L.F.; funding acquisition, L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Brazilian governmental agencies CNPq (Process 309903/2022-0) and CAPES.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was part of a larger institutional project titled “Developmental process of positive psychological variables in the context of sports”, which was approved by the Permanent Committee of Ethics in Human Research of the State University of Maringá (COPEP-UEM) under the appreciation number 5.658.001.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, as further described in the Procedures section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- World Anti-Doping Association. (2015). World anti-doping code 2015. Available at https://www.wada-ama.org/en/what-we-do/the-code.

- Aguilar-Navarro, M., Salinero, J.J., Munoz-Guerra, J., Plata, M.D.M., & Del Coso, J. (2020) Sport-specific use of doping substances: Analysis of World Anti-Doping Agency doping control tests between 2014 and 2017. Substance Use & Misuse 55(8), 1361-1369. [CrossRef]

- Elbe, A.; Barkoukis, V. (2017) The psychology of doping. Current Opinion in Psychology, 16, 67-71.

- Nicholls, A.R.; Madigan, D.J.; Backhouse, S.H.; Levy, A.R. (2017) Personality traits and performance enhancing drugs: The Dark Triad and doping attitudes among competitive athletes. Personality and Individual Differences, 112, 113-116.

- Barkoukis, V.; Lazuras, L.; Tsorbatzoudis, H.; Rodafinos, A. (2013) Motivational and social cognitive predictors of doping intentions in elite sports: an integrated approach. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine Science and Sports, 23, 330-340.

- Folkerts, D., Loh, R., Petróczi, A., Brueckner, S. (2021) The Performance Enhancement Attitude Scale (PEAS) reached ‘adulthood’: Lessons and recommendations from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology of Sport & Exercise. [CrossRef]

- Lazuras, L.; Barkoukis, V.; Tsorbatzoudis, H. (2015) Toward an integrative model of doping use: an empirical study with adolescent athletes. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 37(1), 37-50.

- Hauw, D., & Bilard, J. (2017). Understanding appearance-enhancing drug use in sport using an enactive approach to body image. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 2088.

- Petróczi, A., Norman, P., and Brueckner, S. (2017). “Can we better integrate the role of anti-doping in sports and society? A psychological approach to contemporary value-based prevention,” in Acute Topics in Anti-Doping, Vol. 62 (Karger Publishers), 160–176.

- Ntoumanis, N.; Ng, J.Y.; Barkoukis, V.; Backhouse, S. (2014). Personal and psychosocial predictors of doping use in physical activity settings: a meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 44(11), 1603-1624.

- Petróczi, A. (2002). Exploring the doping dilemma in elite sport: Can athletes' attitudes be responsible for doping? [Published doctoral dissertation]. University of Northern Colorado.

- Petróczi, A.; Aidman, E. (2009). Measuring explicit attitude toward doping: review of the psychometric properties of the Performance Enhancement Attitude Scale. Psychology of Sport and Exercise,10, 390-396.

- Moran, A., Guerin, S., Kirby, K., & MacIntyre, T. (2008). The development and validation of a doping attitudes and behaviour scale (WADA Social Science Research Report). World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). https://www.wadaama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/moran_final_report.pdf.

- Bondarev, D., Galchinskiy, V., Ajitskiy, K., & Labskir, V. (2009). A study of surroundings’influence on attitude towards and behavior regarding doping (WADA Social Science Research Report). World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).https://www.wadaama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/bondarev_eng_-_final_report_2009_funded_-_attitude_and_behaviour.pdf.

- Dimeo, P., Allen, J., Taylor, J., Dixon, S., & Robinson, L. (2011). Team dynamics and doping in sport: A risk or a protective factor (WADA Social Science Research Report). World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). https://www.wadaama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/dimeo_team_dynamics_2011_report_en.pdf.

- Skinner, J., Moston, S., & Engelberg, T. (2012). The relationship between moral code, participation in sport, and attitudes, towards performance enhancing drugs in young people (WADA Social Science Research Report). World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). https://www.wadaama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/skinner_moston_engelberg_2012_final_report_to_wada_30-03-12.pdf.

- Kamenju, J., Mwisukha, A., & Rintaugu E. (2016). Awareness, Perception and Attitude to Performance-enhancing drugs and Substance use Among Athletes in Teacher Training Colleges in Kenya (WADA Social Science Research Report). World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/awareness_perception_and_attitude_to_peds_in_kenya_-_kamenju.pdf.

- Morente-Sánchez, J.; Zabala, M. (2013). Doping in sport: a review of elite athletes’ attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge. Sports Medicine, 43(6), 395-411.

- Blank, C., Kopp, M., Niedermeier, M., Schnitzer, M., Schobersberger, W. (2016) Predictors of doping intentions, susceptibility, and behaviour of elite athletes: a meta-analytic review. SpringerPlus, 5, 1333. [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.K.C.; Tang, T.C.W. ; Gucciardi, D.F.; Ntoumanis, N.; Dimmock, J.A.; Donovan, R.J.; Hardcastle, S.J.; Hagger, M.S. (2018). Psychological and behavioural factors of unintentional doping: a preliminary systematic review. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Mallinson-Howard, S.H.; Grugan, M.C.; Hill, A.P. (2019). Perfectionism and attitudes towards doping in athletes: a continuously cumulating meta-analysis and test of the 2x2 model. European Journal of Sport Science. [CrossRef]

- Pasquali, L. (2007). Validade dos Testes Psicológicos: Será Possível Reencontrar o Caminho? Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 23, Special Number, 99-107.

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Hu, L.-t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Balbin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tathan, R. (2009). Análise multivariada de dados. São Paulo, SP: Bookman.

- DeVellis, R.F. (2012). Scale Development: Theory and Applications. SAGE Publications.

- Wang, S., Jones, P., Dreier, M., Elliott, H., And Grilo, C. (2018). Core psychopathology of treatment-seeking patients with binge-eating disorder: a network analysis investigation. Psychol. Med., 49, 1923–1928. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.B.O, Matheus, R.F., Parreiras, F.S., & Parreiras, T.A.S. (2006) Estudo da rede de coautoria e da interdisciplinaridade na produção científica com base nos métodos de análise de redes sociais: avaliação do caso do programa de pós-graduação em ciência da informação - Ppgci/Ufmg. Encontros bibli: rev. Elet. De bibliotec. E cienc. Da inf., p. 179–194. [CrossRef]

- Hevey D. (2018). Network analysis: a brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychol Behav Med. 25;6(1):301-328. [CrossRef]

- Mullan, E., Markland, D., Ingledew, D. (1997). A graded conceptualisation of self-determination in the regulation of exercise behaviour: Development of a measure using confirmatory factor analytic procedures, Personality and Individual Differences, 23(5), 745-752. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2015) Confirmatory Factor analysis for applied research. The Guilford Press: New York.

- Hauw, D., Crettaz von Roten, F., Mohamed, S., & Antonini Philippe, R. (2016). Psychometric properties of the French-language version of the Performance Enhancement Attitude Scale (PEAS). European Review of Applied Psychology, 66(1), 15-21. [CrossRef]

- Morente-Sánchez, J., Femia-Marzo, P., & Zabala, M. (2014). Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Spanish version of the Performance Enhancement Attitude Scale (Petróczi, 2002). Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 13(2), 430-438.

- Divkan, B., Tojari, F., Mosavi, S.M., & Ganjouei, F. (2013). Development and validation of Performance Enhancement Attitude toward Doping scale in elite athletes of Iran. Advances in Environmental Biology, 7(11), 3345-3349.

- Soltanabadi, S., Tojari, F., Manouchechri, J. (2014). Validity and reliability of measurement instruments of doping attitudes and doping behavior in iranian professional athletes of team sports. Indian Journal of Fundamental and Applied Life Sciences, 4(S4), 280-286.

- Elbe, A.-M., & Brand, R. (2016). The effect of an ethical decision-making training on young athletes' attitudes toward doping. Ethics & Behavior, 26(1), 32-44. [CrossRef]

- Sas-Nowosielski, K., & Budzisz, A. (2018). Attitudes toward doping among Polish athletes measured with the Polish version of Petroczi’s Performance Enhancement Attitude Scale. Polish Journal of Sport and Tourism, 25(2), 10-13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).