Submitted:

25 March 2024

Posted:

25 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Data

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Herd Vitality

2.4. Sustainability Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Breeders Indicators

3.2. Economic Metrics

3.3. Herd Management Pointers

3.4. Sustainability Assessment

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Molotsi, A. H., Dube, B., & Cloete, S. W. (2019). The Current Status of Indigenous Ovine Genetic Resources in Southern Africa and Future Sustainable Utilisation to Improve Livelihoods. Diversity, 12(1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Al-Khaza’leh, J. M. K. (2018). Goat Farming and Breeding in Jordan. IntechOpen. Chapter 17. Pages 368-380. [CrossRef]

- Jetter Christopher. (2008). "An Assessment of Subsidy Removal Effects on and Future Sustainability for Livestock Sector of in the Northern Jordanian Badia". Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 7. https://digitalcollections. sit.edu/isp_collection/7.

- Paraskevopoulou, C., Theodoridis, A., Johnson, M., Ragkos, A., Arguile, L., Smith, L., Vlachos, D., & Arsenos, G. (2019). Sustainability Assessment of Goat and Sheep Farms: A Comparison between European countries. Sustainability, 12 (8), 3099. [CrossRef]

- Koluman, N., Durmuş, M., & Güngör, İ. (2023). Improving reproduction and growth characteristics of indigenous goats in smallholding farming system. Ciência Rural, 54, e20230028. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hunaiti Dokhi Abdel-Rahim. (2007). The main structure of livestock holdings, characteristics and distribution, analysis of the results of the agricultural census. College of Agriculture, Mutah University. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. http://www.dos.gov.jo/dos_home_a/main/agriculture/ census/papers/paper_3.pdf.

- SAS, (2012). Institute Inc.: SAS/STAT User’s Guide: Version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., and Cary, NC, USA. https://Support.Sas.Com/En/ Books.Html.

- Wade, M. J. (1979). Sexual Selection and Variance in Reproductive Success. The American Naturalist. [CrossRef]

- Payne, R. B. (1979). Sexual Selection and Intersexual Differences in Variance of Breeding Success. The American Naturalist. [CrossRef]

- Scherer, L., Tomasik, B., Rueda, O. et al., (2018). Framework for integrating animal welfare into life cycle sustainability assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 23, 1476–1490. [CrossRef]

- De Olde, E. M., Bokkers, E. A., & De Boer, I. J. (2017). The Choice of the Sustainability Assessment Tool Matters: Differences in Thematic Scope and Assessment Results. Ecological Economics, 136, 77-85. [CrossRef]

- Lianou, D. T., & Fthenakis, G. C. (2021). Dairy Sheep and Goat Farmers: Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Their Associations with Health Management and Performance on Farms. Land, 10(12), 1358. [CrossRef]

- Hassan D.I., Mbap S.T. and Naibi S.A. (2015). Socio-Economic Characteristics of Yankasa Sheep and West African Dwarf Goat’s Farmers and Their Production Constraints in Lafia, Nigeria. International Journal of Food, Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences. Vol.5 (1), pp. 82-93. http://www.cibtech.org/jfav.htm.

- Shivakumara C., Reddy B.S., Patil S. S. (2020). Socio-Economic Characteristics and Composition of Sheep and Goat Farming under Extensive System of Rearing. Agricultural Science Digest. 40(1): 105-108. [CrossRef]

- Sagarnaga Villegas, Leticia Myriam and Salas González, José María and Aguilar Ávila, Jorge. (2015). Production Costs, Equilibrium, and Target Prices of a Goat Farm in Hidalgo, Mexico. XIV International Business and Economy Conference Bangkok, Thailand. [CrossRef]

- Tsiouni, M., Mamalis, S., Aggelopoulos, S. (2022). The Effect of Financial and Non-financial Factors on the Productivity and Profitability of the Goat Industry: A Modelling Approach to Structural Equations. In: Mattas, K., Baourakis, G., Zopounidis, C., Staboulis, C. (eds) Food Policy Modelling. Cooperative Management. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Lima, E., Green, M., Lovatt, F., Davies, P., King, L., & Kaler, J. (2019). Use of bootstrapped, regularised regression to identify factors associated with lamb-derived revenue on commercial sheep farms. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 174, 104851. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K., Dixit, A.K., Roy, A.K., Singh, S.K. (2013). Goat Rearing: A Pathway for Sustainable Livelihood Security in Bundelkhand Region. Agricultural Economics Research Review. Vol. 26. https://ageconsearch. umn.edu/record/158491.

- Singh, V. K., Suresh, A., Gupta, D. C., & Jakhmola, R. C. (2005). Common property resources rural livelihood and small ruminants in India: A review. The Indian Journal of Animal Sciences, 75(8). https://epubs.icar.org.in/index.php/ IJAnS/article/view/9466.

- Charles Byaruhanga, James Oluka, Stephen Olinga. (2015). Socio-economic Aspects of Goat Production in a Rural Agro-pastoral System of Uganda. Universal Journal of Agricultural Research 3(6): 203-210. [CrossRef]

- Morris, S. (2009). Economics of sheep production. Small Ruminant Research, 86(1-3), 59-62. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sharafat, Meqbel Msallam. (2001). Government policies affecting the sheep industry in the northern Jordanian Badia and Bedouin responses, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4319/.

- Bdour, M. A., Zyadeen , A. F., & Alkawalit , N. T. (2023). Estimating Economic Returns of Sheep and Goat Rearing in Karak Governorate. Jordan Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 19(2), 142–152. [CrossRef]

- Dossa, L. H., Sangaré, M., Buerkert, A., & Schlecht, E. (2015). Production objectives and breeding practices of urban goat and sheep keepers in West Africa: Regional analysis and implications for the development of supportive breeding programs. SpringerPlus, 4(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo, J. A., Gelez, H., Ungerfeld, R., Hawken, P. A., & Martin, G. B. (2009). The ‘male effect’ in sheep and goats—Revisiting the dogs. Behavioral Brain Research, 200(2), 304-314. [CrossRef]

- Sharifian, A., Gantuya, B., Wario, H. T., Kotowski, M. A., Barani, H., Manzano, P., Krätli, S., Babai, D., Biró, M., Sáfián, L., Erdenetsogt, J., Qabel, Q. M., & Molnár, Z. (2023). Global principles in local traditional knowledge: A review of forage plant-livestock-herder interactions. Journal of Environmental Management, 328, 116966. [CrossRef]

- Farrell L., P. Creighton, A. Bohan, F. McGovern, N. McHugh. (2022). Bio-economic modeling of sheep meat production systems with varying flock litter size using field data, animal, Volume 16, Issue 10, 100640. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, L., Obeidat, J.M., Al-Ani, F.K., & Vet, J. (2005). Risk Factors for Lamb and Kid Mortality in Sheep and Goat Farms in Jordan. http://uni-sz.bg/ bjvm/vol08-No2-03.pdf.

- Thiruvenkadani, A. K., & Karunanithi, K. (2007). Mortality and replacement rate of Tellicherry and its crossbred goats in Tamil Nadu. The Indian Journal of Animal Sciences, 77(7). 590-594. https://epubs.icar.org.in/index.php/IJAnS/ article/view/5504.

- Dwyer CM. (2014). Maternal behavior and lamb survival: from neuroendocrinology to practical application. Animal. 2014; 8(1):102-112. [CrossRef]

- Al-Najjar K., S. Salhab, R. Al-Merestani, K. Reiad, W. Al-Azzawi, M. Dawa, H. Omed, and M. Saatci. (2010). Environmental factors affecting kid mortality in Shami goats. Kafkas Univ. Vet Fak Derg., 16(3): 431-435. [CrossRef]

- Roukbi, M., Al-Omar, A. N., Al-Najjar, K., Salam, Z., Al-Suleiman, H., Mourii, M., & Jourié, S. (2016). Seroprevalence of antibodies to Chlamydophila abortus in small ruminants in some provinces in Syria. Net Journal Agricultural Science. Vol. 4(2), 29-34. https://www.netjournals.org/z_NJAS_16_019.html.

- Snowder, G., Stellflug, J., & Van Vleck, L. (2004). Genetic correlation of ram sexual performance with ewe reproductive traits of four sheep breeds. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 88(3-4), 253-261. [CrossRef]

- 34. Matika O., J.B. Van Wyk, G.J. Erasmus and R.L. Baker. (2001). Phenotypic and genetic relationships between lamb and ewe traits for the Sabi sheep of Zimbabwe. South African Journal of Animal Science. Vol. 31 No. 3. 215-222. [CrossRef]

- Näsholm, A., & Danell, Ö. (1996). Genetic relationships of lamb weight, maternal ability, and mature ewe weight in Swedish fine wool sheep. Journal of Animal Science, 74(2), 329-339. [CrossRef]

- 36. Madibela OR., BM Mosimanyana, WS Boitumelo, TD Pelaelo. (2002). Effect of supplementation on reproduction of wet season kidding Tswana goats. Vol. 32 No. 1, 14-22. [CrossRef]

- Josiane, M., Gilbert, H., & Johann, D. (2019). Genetic Parameters for Growth and Kid Survival of Indigenous Goat under Smallholding System of Burundi. Animals, 10(1), 135. [CrossRef]

- Montaldo, H., Valencia-Posadas, M., Wiggans, G., Shepard, L., & Torres-Vázquez, J. (2009). Short communication: Genetic and environmental relationships between milk yield and kidding interval in dairy goats. Journal of Dairy Science, 93(1), 370-372. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2009-2593. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, B. U., Herms, T. L., Runge, M., & Ganter, M. (2022). A Q fever outbreak on a dairy goat farm did not result in Coxiella burnetii shedding on neighboring sheep farms – An observational study. Small Ruminant Research, 215, 106778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2022.106778. [CrossRef]

- Manyeki, J., Kidake, B., Mulei, B., Kuria, S. (2022). Mortality in Galla Goat Production System in Southern Rangelands of Kenya: Levels and Predictors. Journal of Agricultural Production, 3(2), 48-57. [CrossRef]

- Silva, S. R., Almeida, M., Ribeiro, D. M., Guedes, C., González Montaña, J. R., Pereira, A. F., Zaralis, K., Geraldo, A., Tzamaloukas, O., Cabrera, M. G., Castro, N., Argüello, A., E., L., J., Á., Martín, M. J., G., L., Stilwell, G., & De Almeida, A. M. (2021). Extensive Sheep and Goat Production: The Role of Novel Technologies towards Sustainability and Animal Welfare. Animals, 12(7), 885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12070885. [CrossRef]

- Caroprese, M., Albenzio, M., Sevi, A. (2015). Sustainability of Sheep and Goat Production Systems. In: Vastola, A. (eds) The Sustainability of Agro-Food and Natural Resource Systems in the Mediterranean Basin. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Pavan Kumar, Abubakar Ahmed Abubakar, Akhilesh Kumar Verma, Pramila Umaraw, Muideen Adewale Ahmed, Nitin Mehta, Muhammad Nizam Hayat, Ubedullah Kaka & Awis Qurni Sazili. (2023). New insights in improving sustainability in meat production: opportunities and challenges, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 63:33, 11830-11858. [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.C., Austrheim, G., Asheim, L.J. et al., (2016). Sheep grazing in the North Atlantic region: A long-term perspective on environmental sustainability. Ambio 45, 551–566. [CrossRef]

- Ripoll-Bosch, R., Díez-Unquera, B., Ruiz, R., Villalba, D., Molina, E., Joy, M., Olaizola, A., & Bernués, A. (2011). An integrated sustainability assessment of mediterranean sheep farms with different degrees of intensification. Agricultural Systems, 105(1), 46-56. [CrossRef]

- Molotsi, A., Dube, B., Oosting, S., Marandure, T., Mapiye, C., Cloete, S., & Dzama, K. (2017). Genetic Traits of Relevance to Sustainability of Smallholder Sheep Farming Systems in South Africa. Sustainability, 9(8), 1225. [CrossRef]

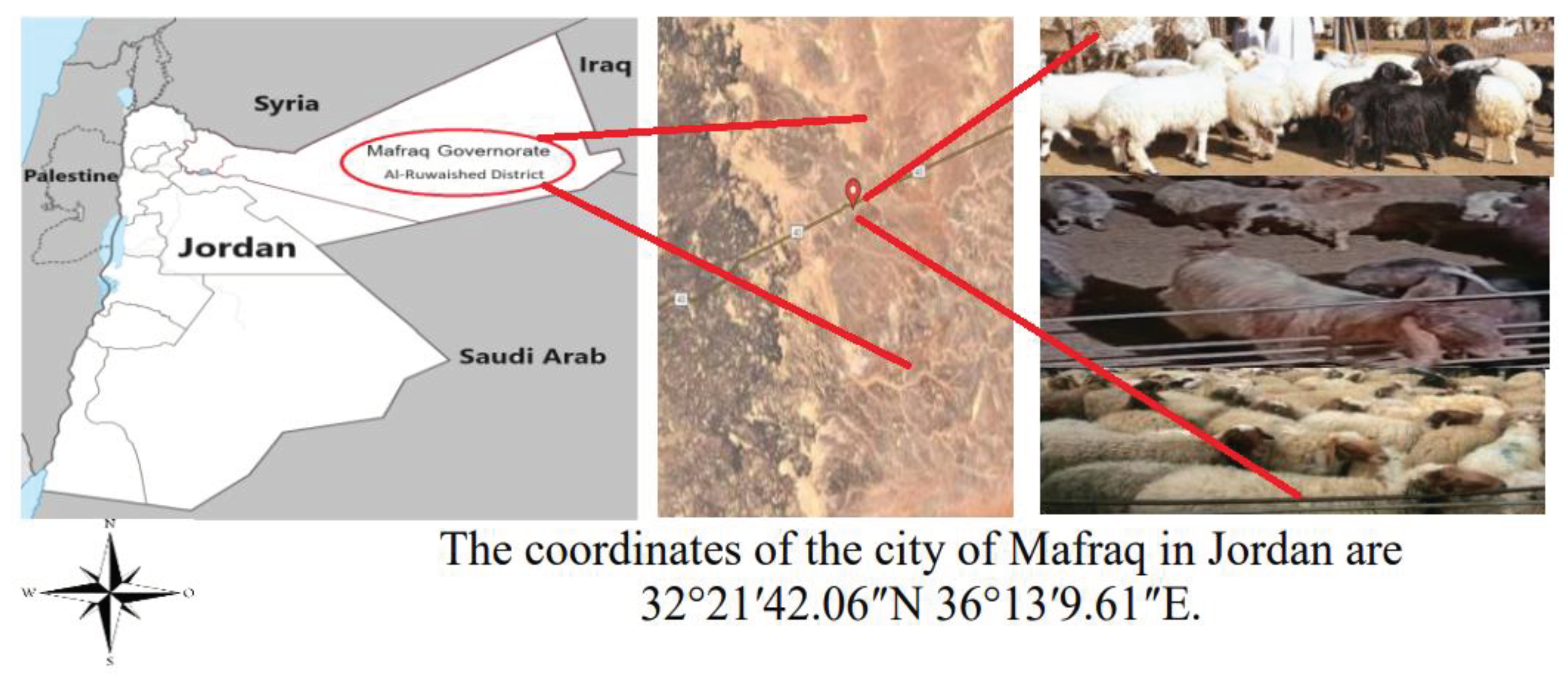

- Awad, R., Titi, H., Mohamed-Brahmi, A., Jaouad, M., & Gasmi-Boubaker, A. (2023). Small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District, Jordan. Regional Sustainability, 4(4), 416-424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsus.2023.11.006. [CrossRef]

- Peacock, C., and Sherman, D. (2010). Sustainable goat production—Some global perspectives. Small Ruminant Research, 89(2-3), 70-80. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/ j.smallrumres.2009.12.029. [CrossRef]

- Assan, N. (2023). Goat - A Sustainable and Holistic Approach in Addressing Triple Challenges of Gender Inequality, Climate Change Effects, Food and Nutrition Insecurity in Rural Communities of Sub-Saharan Africa. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Koşum, N., Taşkin, T., Engindeniz, S., Kandemir, Ç. (2019). Goat Meat Production and Evaluation of Its Sustainability in Turkey. Ege Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi, 56(3), 395-407. https://doi.org/10.20289/zfdergi. 520488. [CrossRef]

| Indicators | Level of education | Land ownership | Land cultivation | Fodder cultivation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience of breeder/ Years | 0.89** | 0.80** | 0.82** | 0.86** |

| Level of education | 0.79** | 0.83** | 0.84** | |

| Land ownership | 0.96** | 0.73** | ||

| Land cultivation | 0.76** |

| S.O.V | DF | Mean Square | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual return | Pr>F | Revenue/ Animal | Pr>F | ||

| Land ownership | 1 | 7799.690 | 0.84 | 37.38126 | 0.43 |

| Land cultivation (Crops) | 1 | 1608904.51 | 0.01 | 0.06169 | 0.97 |

| Fodder cultivation | 1 | 491148.42 | 0.12 | 3.86538 | 0.80 |

| Lamb sales% | 1 | 610598.72 | 0.08 | 245.27786 | 0.04 |

| Kids sales % | 1 | 263846.88 | 0.26 | 2.15647 | 0.85 |

| Random Error | 47 | 203462.91 | 59.78057 | ||

| S.O.V | DF | Mean Square | Pr>F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education Level | 2 | 14045.57 | 0.17 |

| Experience/ years | 1 | 16676.19 | 0.14 |

| Age of Breeder/ years | 1 | 31574.82 | 0.04 |

| Experience × Education Level | 2 | 12673.41 | 0.20 |

| Age of Breeder × Education Level | 2 | 12450.66 | 0.20 |

| Age of Breeder × Experience | 1 | 12712.96 | 0.20 |

| Random Error | 43 | 7685.23 |

| Tables | DF | Values | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males Replacement × Mortality Age /month | 10 | 16.16 | 0.09 |

| Males Replacement × Lamb Mortality % | 27 | 22.61 | 0.70 |

| Males Replacement × Kids Mortality % | 14 | 12.58 | 0.55 |

| Males Replacement × Breeder Experience /years | 9 | 19.07 | 0.02 |

| Males Replacement × Level of Education | 2 | 0.10 | 0.95 |

| S.O.V | DF | Mean Square | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamb mortality% | Pr>F | Kids mortality% | Pr>F | Mortality age/ month | Pr>F | ||

| Other animals | 1 | 1.51987 | 0.38 | 1.09900 | 0.01 | 3.42165 | 0.61 |

| Mortality Months | 1 | 3.99646 | 0.15 | 0.13142 | 0.36 | 286.34653 | 0.01 |

| Level of education | 2 | 3.04641 | 0.21 | 0.04281 | 0.76 | 1.52911 | 0.89 |

| Experience/ years | 1 | 7.16296 | 0.04 | 0.06118 | 0.53 | 8.36724 | 0.42 |

| Weaning age /day | 1 | 1.72492 | 0.35 | 0.47220 | 0.09 | 21.61732 | 0.20 |

| Random Error | 46 | 1.93972 | 0.15905 | 13.14442 | |||

| Herds | Rams % |

Ewe not lambing% | Ewe lambing % |

All lambs % |

Lamb sales % |

Lamb mortality% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep% | -0.08 | -0.18 | 0.21 | -0.06 | 0.42** | -0.50** |

| Rams% | -0.06 | -0.42** | -0.44** | 0.18 | 0.26 | |

| Ewes not lambing% | -0.88** | -0.15 | -0.01 | -0.03 | ||

| Ewes lambing% | 0.33* | -0.06 | -0.11 | |||

| All lambs% | -0.75** | -0.21 | ||||

| Lamb sales% | -0.47** | |||||

| Bucks% | Non-kidding doe % | Kidding doe % | All kids % | Kids sales % |

Kids mortality % | |

| Goats% | -0.38** | -0.03 | 0.17 | -0.33* | 0.35** | 0.07 |

| Bucks% | 0.15 | -0.56** | 0.035 | -0.29* | 0.043 | |

| Non-kidding doe % | -0.90** | 0.10 | -0.13 | -0.19 | ||

| Kidding doe % | -0.07 | 0.24 | 0.12 | |||

| All kids% | -0.06 | -0.77** | ||||

| Kids sales% | -0.55** |

| Indicators | Sheep | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep % |

Ewes birth % | Lambs % |

Lamb survival % | Lamb sales % |

|

| Averages | 56.5 | 95.4 | 25.3 | 96.9 | 18.0 |

| Above average | 47.2 | 60.4 | 37.7 | 75.5 | 56.6 |

| Below average | 52.8 | 39.6 | 62.3 | 24.5 | 43.4 |

| Sustainability assessment | - | + | - | + | + |

| Indicators | Goats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goats % | Doe birth % | Kids % |

Kid survival % | Kid sales % |

|

| Averages | 43.5 | 95.4 | 23.4 | 94.9 | 17.9 |

| Above average | 45.3 | 54.7 | 52.8 | 47.2 | 69.8 |

| Below average | 54.7 | 45.3 | 47.2 | 52.8 | 30.2 |

| Sustainability assessment | - | + | + | - | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).