Submitted:

25 March 2024

Posted:

26 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Research Framework

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

3.1.1. Research Subject Co-Occurrence Analysis

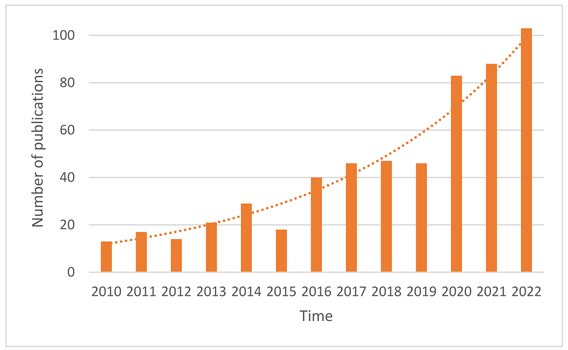

3.1.2. Analysis of Publication Trends and Publication Sources

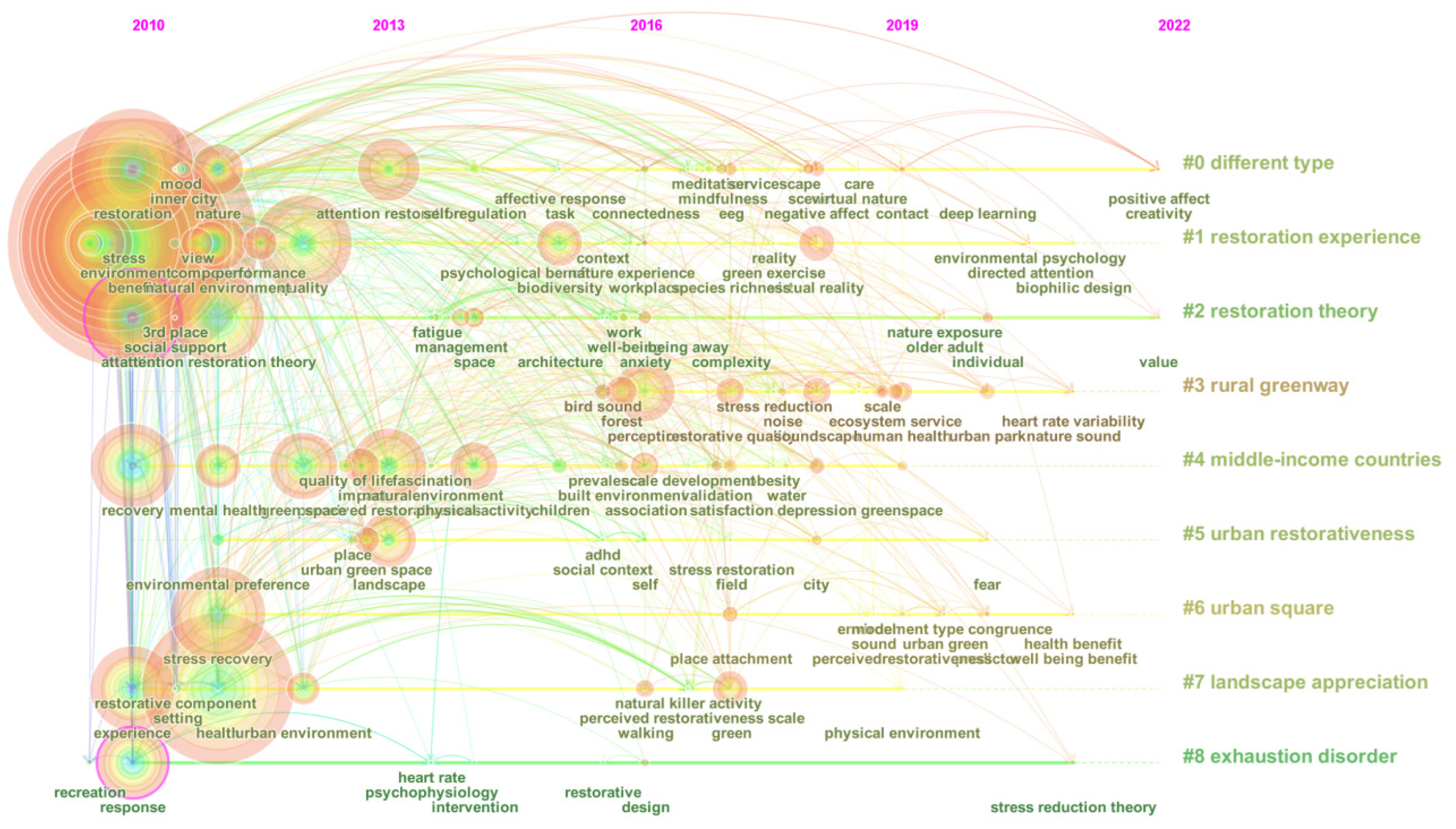

3.1.3. Keyword Atlas Analysis

3.1.4. Knowledge Base Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

3.2.1. Summary of Empirical Research Based on Quantitative Analysis

Research Methods and Steps

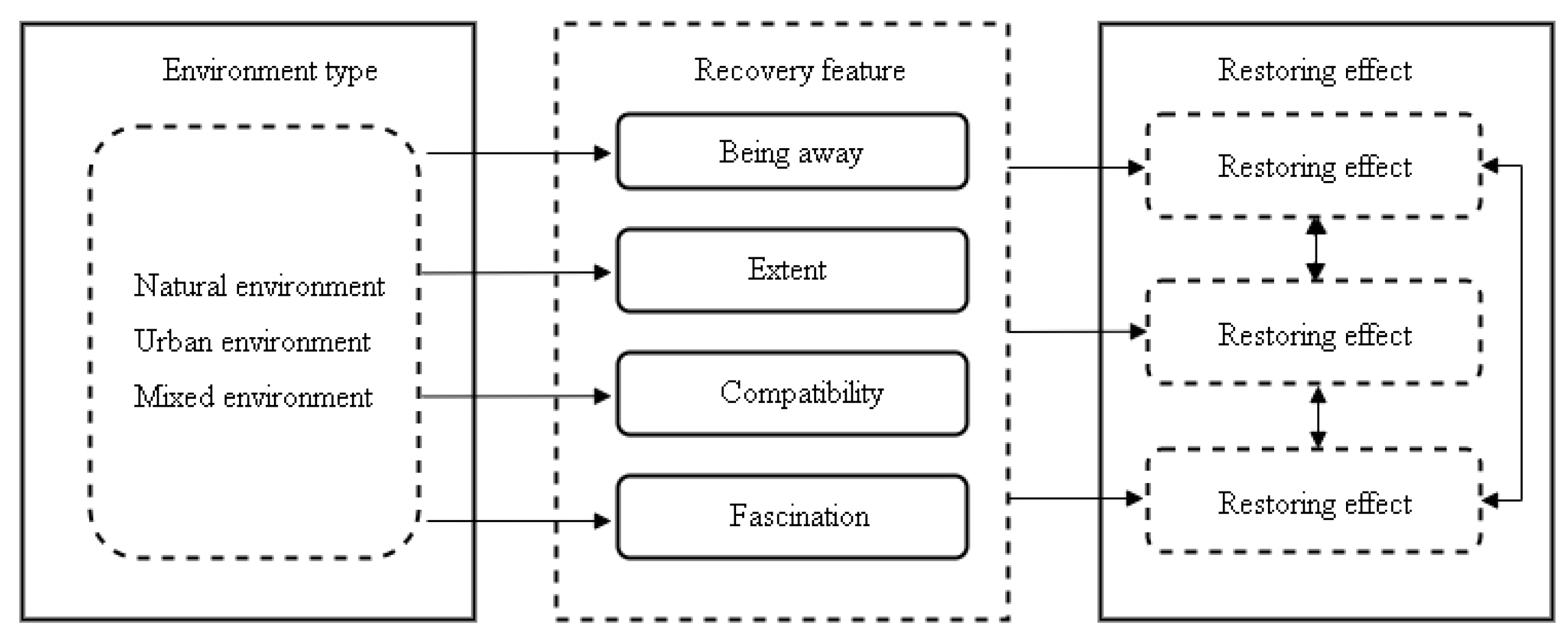

Classification of Environment Types

Evolution of Measurement Methods

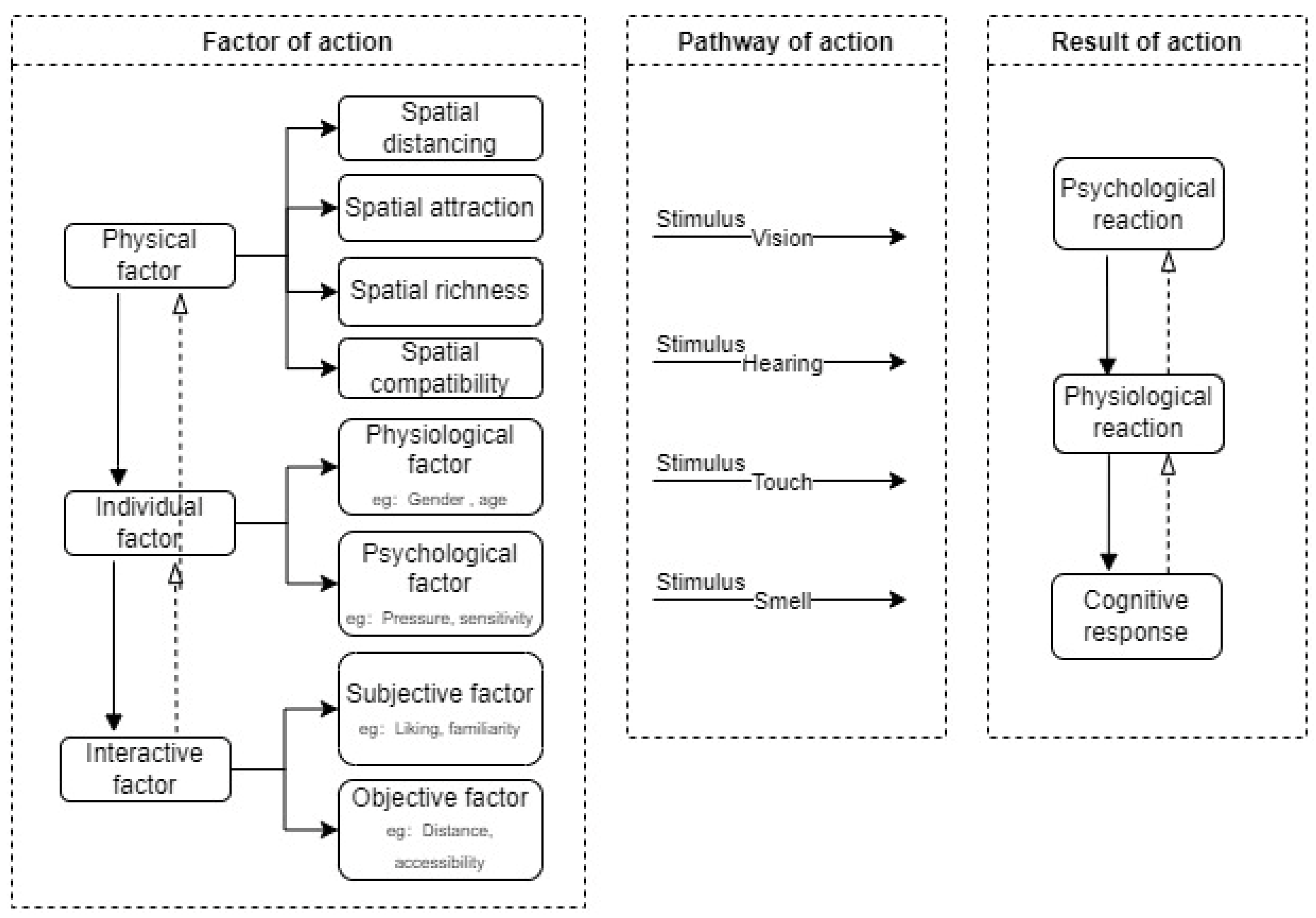

3.2.2. Analysis of Research Fields Based on Action Mechanism

Subjective Exploration of the Psychological Level

Objective Exploration on the Physiological Level

Validation Research on a Cognitive Level

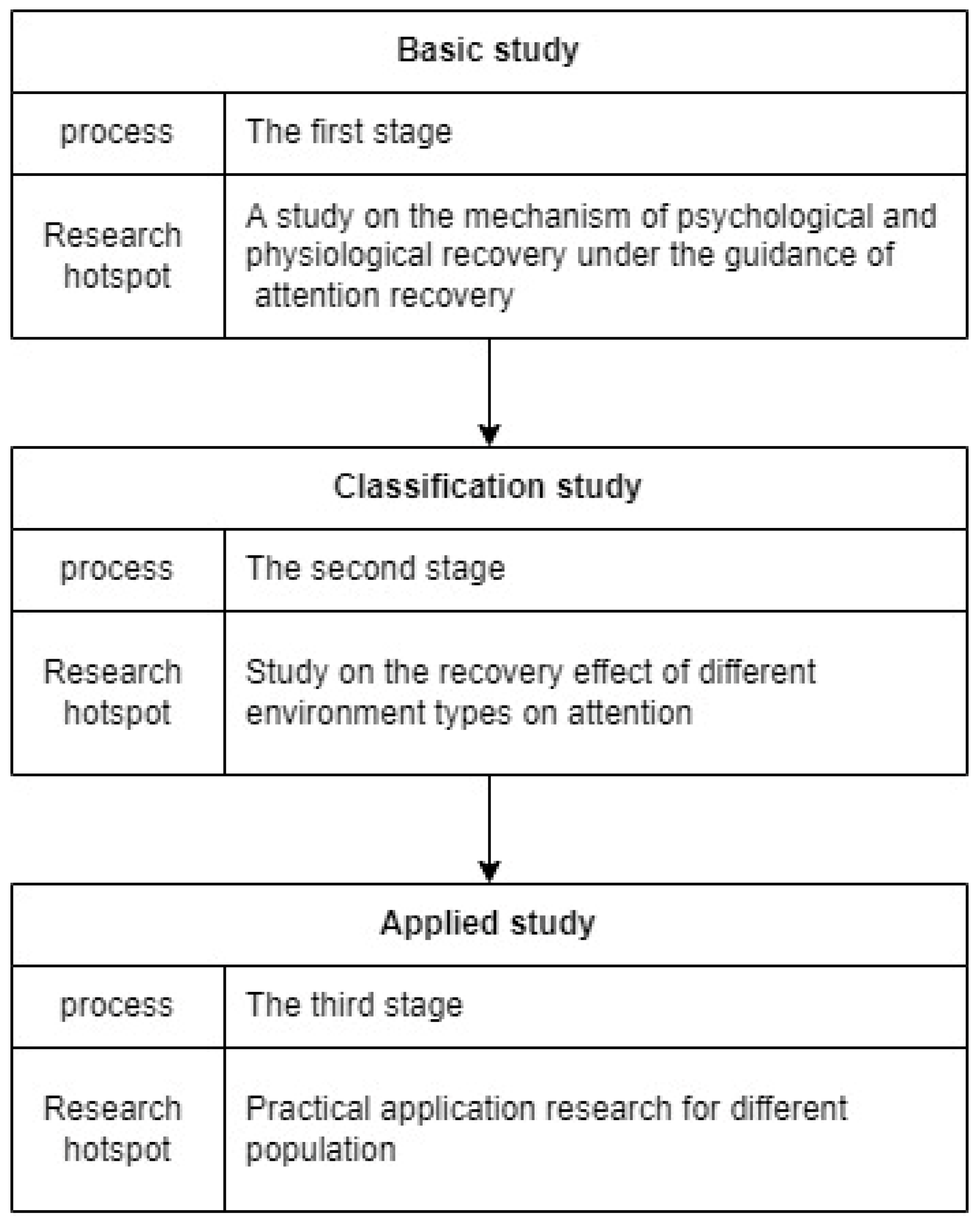

3.2.3. Development Process and Trend Analysis Based on Research

Review the Development Process of Attention Recovery Research

Trends in Attention Restoration Research

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Most studies on attention restoration are rooted in changing social lifestyles and concepts across countries, the growing desire for vibrant architectural spaces, and the exploration of healthy building standards like WELL. While these theories have elucidated the potential of architectural spaces for attention recovery, there remains uncharted territory for integrating attention recovery research with architectural design and translating these theories into specific design strategies. The inherent subjectivity of attention recovery design strategies poses substantial challenges, influenced by personal perceptions, cultural variations, and diverse empirical backgrounds, further exacerbated by the absence of standardized guidelines for applying attention recovery theory in architectural practice. To address these issues, future research should adopt a more comprehensive approach, integrating attention recovery theory into a practical design framework.

- (2)

- Most empirical studies on attention recovery are conducted in controlled laboratory settings, enabling researchers to explore intricate interactions between environmental factors and cognitive processes. However, some psychologists have pointed out a significant disparity between simulated environments and the real world in terms of sensory stimulation. This disparity can impact the assessment of environmental restorative effects. Environmental elements like natural light, ambient sounds, tactile sensations and olfactory cues recreated in a lab setting may not fully capture the richness and complexity of the real world. Consequently, cognitive responses triggered in artificial environments may differ substantially from those in real-world settings. As empirical research advances, addressing this discrepancy becomes crucial for enhancing the validity of research findings. Researchers must bridge the gap between laboratory simulations and natural ecosystems and refine research methodologies to identify factors influencing attention recovery.

- (3)

- When selecting a sample population, it is common to prioritize young individuals, particularly college students, due to their distinctive cognitive characteristics. Nevertheless, one of the key sources of variability in psychological studies is the composition of the survey respondents, as diverse populations, age groups, cultural backgrounds, and life experiences can yield distinct cognitive responses. Overreliance on a single population, such as college students, heightens the risk of empirical bias and limits the generalizability of findings across various populations and environmental contexts. Given that the prevalent use of college students has raised concerns among researchers, future studies should opt for a diverse and representative sample. This includes individuals from different age brackets, occupational backgrounds, cultural contexts, and daily routines, to mitigate issues like experimental errors stemming from subject demographics.

- (4)

- Currently, the majority of studies predominantly explore the visual aspects of environmental stimulation while overlooking the restorative potential offered by the environment through auditory, tactile, and olfactory stimuli. Expanding the scope of research to encompass multi-sensory stimulation can enrich individuals’ spatial experiences. For instance, the gentle breeze or the rhythmic sound of flowing water in the auditory domain can evoke feelings of calm and relaxation. Tactile elements like unique textures or soft seating surfaces contribute to a sense of comfort. Moreover, natural fragrances or soothing scents in the olfactory realm can elicit positive emotional responses. Integrating diverse sensory dimensions fosters multifaceted restorative experiences and cognitive responses, thereby enhancing attention recovery.

- (5)

- Lastly, the majority of prior studies have primarily focused on quantifying the impact of natural environments or natural elements on individual attention, physical well-being, and mental health, often overlooking investigations into urban environments. Despite the substantial body of evidence confirming the restorative attributes of natural elements, urban environments also possess significant restorative potential. While research on urban environments has seen a slight uptick in recent years, it remains relatively limited and fragmented, lacking in-depth exploration (Myers, 2022). Addressing this gap necessitates interdisciplinary collaboration among psychologists, architects, urban planners, and other stakeholders. This collaboration should aim to analyze how various urban elements influence cognitive recovery in individuals and advance the revitalization of urban environments in the context of contemporary society.

Funding

References

- Wang Shiqi. Research on design strategy of university campus space environment in cold regions with attention restoration goal. Tutor: MEI Hongyuan. Harbin Institute of Technology, 2020.

- Ulrich R S, Simons R F, Losito, B.D.; et al. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of environmental psychology 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Yuan, J.; Arfaei, N.; Catalano, P.J.; Allen, J.G.; Spengler, J.D. Effects of the biophilic indoor environment on stress and anxiety recovery: A between-subjects experiment in virtual reality. Environ. Int. 2019, 136, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge university press, 1989.

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of environmental psychology 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela K M, Klemettilä T, Hietanen J K. Evidence for rapid affective evaluation of environmental scenes. Environment and behavior 2002, 34, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: A literature review on restorativeness. Behavioral sciences 2014, 4, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markevych I, Schoierer J, Hartig, T.; et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environmental research 2017, 158, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratman Gregory N, Hamilton J Paul, Daily Gretchen, C. The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2012, 1249. [Google Scholar]

- Bratman Gregory N, Anderson Christopher B, Berman Marc G, Cochran Bobby, de Vries Sjerp, Flanders Jon, Folke Carl, Frumkin Howard, Gross James J, Hartig Terry, Kahn Peter H, Kuo Ming, Lawler Joshua J, Levin Phillip S, Lindahl Therese, MeyerLindenberg Andreas, Mitchell Richard, Ouyang Zhiyun, Roe Jenny, Scarlett Lynn, Smith Jeffrey R, van den Bosch Matilda, Wheeler Benedict W, White Mathew P, Zheng Hua, Daily Gretchen, C. Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective. Science advances 2019, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Liisa Tyrväinen, Ann Ojala, Kalevi Korpela, Timo Lanki, Yuko Tsunetsugu, Takahide Kagawa. The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2014, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Marc, G. Berman, Ethan Kross, Katherine, M. Krpan, Mary K. Askren, Aleah Burson, Patricia J. Deldin, Stephen Kaplan, Lindsey Sherdell, Ian H. Gotlib, John Jonides. Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 2012, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Giuseppe Carrus, Massimiliano Scopelliti, Raffaele Lafortezza, Giuseppe Colangelo, Francesco Ferrini, Fabio Salbitano, Mariagrazia Agrimi, Luigi Portoghesi, Paolo Semenzato, Giovanni Sanesi. Go greener, feel better? The positive effects of biodiversity on the well-being of individuals visiting urban and peri-urban green areas. Landscape and Urban Planning 2015, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Eleanor Ratcliffe, Birgitta Gatersleben, Paul T. Sowden. Bird sounds and their contributions to perceived attention restoration and stress recovery. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2013, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Agnes E. Van den Berg, Anna Jorgensen, Edward R. Wilson. Evaluating restoration in urban green spaces: Does setting type make a difference? Landscape and Urban Planning 2014, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Katherine N. Irvine, Richard A. Fuller, Kevin J. Gaston, Lucy E. Keniger. What are the Benefits of Interacting with Nature? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2013, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Ohly Heather, White Mathew P, Wheeler Benedict W, Bethel Alison, Ukoumunne Obioha C, Nikolaou Vasilis, Garside Ruth. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. Journal of toxicology and environmental health. Part B Critical reviews 2016, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H., Lee, P.J., Jung, T., & Swenson, A. Effects of the aural and visual experience on psycho-physiological recovery in urban and rural environments. Applied Acoustics 2020, 169, 107486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Otsuka, T., Kobayashi, M., Wakayama, Y., Inagaki, H., Katsumata, M., Hirata, Y., Li, Y., Hirata, K., Shimizu, T., Suzuki, H., Kawada, T., & Kagawa, T. Acute effects of walking in forest environments on cardiovascular and metabolic parameters. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2011, 111, 2845–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D.K., Barton, J.L., & Gladwell, V.F. Viewing nature scenes positively affects recovery of autonomic function following acute-mental stress. Environ Sci Technol 2013, 47, 5562–5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartig, T., Evans, G.W., Jamner, L.D., Davis, D.S., & G¨arling, T. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2003, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedblom, M., Gunnarsson, B., Iravani, B., Knez, I., Schaefer, M., Thorsson, P., & Lundstrom, J. N. Reduction of physiological stress by urban green space in a multisensory virtual experiment. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 10113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtchanov, D., & Ellard, C. Physiological and affective responses to immersion in virtual reality: Effects of nature and urban settings. Journal of Cyber Therapy and Rehabilitation 2010, 3, 359–373. [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag-Öström, E., Nordin, M., Lundell, Y., Dolling, A., Wiklund, U., Karlsson, M., Carlberg, B. and Järvholm, L.S. Restorative effects of visits to urban and forest environments in patients with exhaustion disorder. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 2014, 13, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emfield A.G., Neider MB. Evaluating visual and auditory contributions to the cognitive restoration effect. Frontiers in psychology 2014, 5, 548. [Google Scholar]

- Evensen KH, Raanaas RK, Hagerhall C.M.; et al. Restorative elements at the computer workstation: A comparison of live plants and inanimate objects with and without window view. Environment and Behavior 2015, 47, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman G N, Daily G C, Levy B J.; et al. The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. Landscape and Urban Planning 2015, 138, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotti, M., Klein, E., Golem, D., Piepenbrink, E., & Kaplan, K. Is Viewing a Nature Video After Work Restorative? Effects on Blood Pressure, Task Performance, and Long-Term Memory. Environment and Behavior 2015, 47, 947–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.H., Saeidi-Rizi, F., McAnirlin, O., Yoon, H., & Pei, Y. The role of methodological choices in the effects of experimental exposure to simulated natural landscapes on human health and cognitive performance: A systematic review. Environment and Behavior 2020, 0013916520906481. [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi, M.; Endo, J.; Akatsuka, S.; Uno, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Seko, Y. Influence of forest walking on blood pressure, profile of mood States, and stress markers from the viewpoint of aging. J. Aging Gerontol. 2013, 1, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.J., Tsunetsugu, Y., Kasetani, T., Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunetsugu, Y., Park, B.J., Ishii, H., Hirano, H., Kagawa, T., Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the forest) in an old-growth broadleaf forest in Yamagata prefecture, Japan. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2007, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beute F., De Kort Y A W. Natural resistance: Exposure to nature and self-regulation, mood, and physiology after ego-depletion. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2014, 40, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E., Buyung-Ali, L., Knight, T.M., Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar]

- Bratman, G.N., Daily, G.C., Levy, B.J., Gross, J.J. The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 138, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly Heather, White Mathew P, Wheeler Benedict W, Bethel Alison, Ukoumunne Obioha C, Nikolaou Vasilis, Garside Ruth. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments.. Journal of toxicology and environmental health. Part B, Critical reviews, 2016, 19.

- Lyu K, de Dear R, Brambilla A.; et al. Restorative benefits of semi-outdoor environments at the workplace: Does the thermal realm matter? Building and Environment 2022, 222, 109355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon J.Y., Jo H.I., Lee K. Potential restorative effects of urban soundscapes: Personality traits, temperament, and perceptions of VR urban environments. Landscape and Urban Planning 2021, 214, 104188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag-Öström E, Nordin M, Lundell Y.; et al. Restorative effects of visits to urban and forest environments in patients with exhaustion disorder. Urban forestry & urban greening 2014, 13, 344–354. [Google Scholar]

- Evensen K H, Raanaas R K, Hagerhall C.M..; et al. Restorative elements at the computer workstation: A comparison of live plants and inanimate objects with and without window view. Environment and Behavior 2015, 47, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson M P, Schilhab T, Bentsen P. Attention Restoration Theory II: A systematic review to clarify attention processes affected by exposure to natural environments. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B 2018, 21, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg A E, Jorgensen A, Wilson E R. Evaluating restoration in urban green spaces: Does setting type make a difference? Landscape and Urban Planning 2014, 127, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumann K, Gärling T, Stormark K M. Rating scale measures of restorative components of environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2001, 21, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P. Affective priming of perceived environmental restorativeness. International Journal of Psychology 2014, 49, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M., Kim, S., & Lee, J. Pilot study on the physio-psychological effects of botanical gardens on the prefrontal cortex activity in an adult male group. J. People Plants Environ 2022, 25, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.J., Tsunetsugu, Y., Kasetani, T., Hirano, H., Kagawa, T., Sato, M., & Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the forest)–using salivary cortisol and cerebral activity as indicators. Journal of Physiological Anthropology 2007, 26, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C., Lyu, B., Deng, S., Yu, Y., Li, N., Lin, W., Li, D., & Chen, Q. Benefits of a three-day bamboo forest therapy session on the physiological responses of university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H., Song, C., Ikei, H., Park, B.J., Kagawa, T., & Miyazaki, Y. Combined effect of walking and forest environment on salivary cortisol concentration. Frontiers in Public Health 2019, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.P., Lee, H.Y., & Luo, X.Y. The effect of virtual reality forest and urban environments on physiological and psychological responses. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 2018, 35, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geniole, S.N., David, J.P.F., Euz’ebio, R.F.R., Toledo, B.Z.S., Neves, A.I.M., & McCormick, C.M. Restoring land and mind: The benefits of an outdoor walk on mood are enhanced in a naturalized landfill area relative to its neighboring urban area. Ecopsychology 2016, 8, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Otsuka, T., Kobayashi, M., Wakayama, Y., Inagaki, H., Katsumata, M., Hirata, Y., Li, Y., Hirata, K., Shimizu, T., Suzuki, H., Kawada, T., & Kagawa, T. Acute effects of walking in forest environments on cardiovascular and metabolic parameters. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2011, 111, 2845–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A., Tao, J., Li, G., Jiang, M., Aii, L., Zhihui, J., Zongfang, L., & Qibing, C. Effects of walking in bamboo forest and city environments on brainwave activity in young adults. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2018, 2018, 9653857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, J.P., Knight, A.T., Strong, E.A., Heng, V., Neale, C., Cromie, R., & Vercammen, A. The application of wearable technology to quantify health and wellbeing Co-benefits from urban wetlands. Frontiers in Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Corazon, S.S., Sidenius, U., Poulsen, D.V., Gramkow, M.C., & Stigsdotter, U.K. Psycho-physiological stress recovery in outdoor nature-based interventions: A systematic review of the past eight years of research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.C., Jacoby, S.F., & South, E.C. Does spending time outdoors reduce stress? A review of real-time stress response to outdoor environments. Health & Place 2018, 51, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett J, J. The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. 2016.

- Sedghikhanshir A, Zhu Y, Beck M R.; et al. The Impact of Visual Stimuli and Properties on Restorative Effect and Human Stress: A Literature Review. Buildings 2022, 12, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto Y, van der Leij A R, Sligte I.G..; et al. Bottom-up and top-down attention are independent. Journal of vision 2013, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohly H, White M P, Wheeler B W.; et al. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B 2016, 19, 305–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menardo E, Brondino M, Hall R.; et al. Restorativeness in natural and urban environments: A meta-analysis. Psychological Reports 2021, 124, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk C L, Remington R W, Johnston J C. Involuntary covert orienting is contingent on attentional control settings. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human perception and performance 1992, 18, 1030. [Google Scholar]

- Berto, R. The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: A literature review on restorativeness. Behavioral sciences 2014, 4, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fandetti, R. Attention Restoration Theory: Urban Versus Natural Stimuli Effects on Working Memory. California State University, Long Beach, 2022.

- Schumann F, Steinborn M B, Kürten J.; et al. Restoration of attention by rest in a multitasking world: Theory, methodology, and empirical evidence. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 1415. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C O, Browning W D, Clancy J O.; et al. Biophilic design patterns: Emerging nature-based parameters for health and well-being in the built environment. ArchNet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 2014, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm S, Dearborn L, Pomeroy J. Nature and the City: Measuring the Attention Restoration Benefits of Singapore’s Urban Vertical Greenery. Technology| Architecture+ Design 2018, 2, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson M P, Dewhurst R, Schilhab T.; et al. Cognitive restoration in children following exposure to nature: Evidence from the attention network task and mobile eye tracking. Frontiers in psychology 2019, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela K, De Bloom J, Kinnunen U. From restorative environments to restoration in work. Intelligent Buildings International 2015, 7, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshbaum M N, Donbavand J. Making the most out of life: Exploring the contribution of attention restorative theory in developing a non-pharmacological intervention for fatigue. Palliative & supportive care 2014, 12, 473–480. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson K, Thatcher A. Do indoor plants improve performance outcomes?: Using the attention restoration theory. In Proceedings of the 20th Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2018) Volume VIII: Ergonomics and Human Factors in Manufacturing, Agriculture, Building and Construction, Sustainable Development and Mining 20. Springer International Publishing, 2019; 591-604.

- Boggs, J. The Roles of Biophilic Attitudes and Auditory Stimuli within Attention Restoration Theory. University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 2018.

- Asim F, Shree V. The impact of Biophilic Built Environment on Psychological Restoration within student hostels. Visions for Sustainability, 2019.

- Green, J. Back to nature for good: Using biophilic design and attention restoration theory to improve well-being and focus in the workplace. 2012.

- Jaggard C, E. The Effect of Intentionally Engaging Attention when Viewing Restorative Environments: Exploring Attention Restoration Theory. Indiana State University, 2014.

- Lu M, Fu J. Attention restoration space on a university campus: Exploring restorative campus design based on environmental preferences of students. International journal of Environmental research and public health 2019, 16, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue Miao, Zhang Xinshuo, Zhang Junjie. Analysis of knowledge graph of pro-nature building design and its health benefit. Southern Architecture, 2022; 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich R S, Simons R F, Losito B D.; et al. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of environmental psychology 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith L, E. Attention restoration theory and the open office: Addressing mental fatigue in low stimulus screeners and creative class workers through biophilic design. 2013.

- Elzinga L A, J. The green office: The influence of plants at the office, effectuating a more natural environment, on restoration from mental fatigue and stress as mediated by restorative characteristics among office employees. University of Twente, 2020.

- Myers M, G. Visual art as a restorative, placed-based biophilic coping mechanism in the workplace: A case study. Kent State University, 2020.

- Evensen K H, Raanaas R K, Hagerhall C M.; et al. Restorative elements at the computer workstation: A comparison of live plants and inanimate objects with and without window view. Environment and Behavior 2015, 47, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson K, Thatcher A. Do indoor plants improve performance outcomes?: Using the attention restoration theory. In Proceedings of the 20th Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2018) Volume VIII: Ergonomics and Human Factors in Manufacturing, Agriculture, Building and Construction, Sustainable Development and Mining 20. Springer International Publishing, 2019; pp. 591–604.

- Amirbeiki F, Khaki Ghasr A. Investigating the Effects of Exposure to Natural Blue Elements on the Psychological Restoration of University Studentsity Students. Iran University of Science & Technology 2020, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, E. Sound and soundscape in restorative natural environments: A narrative literature review. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 570563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang S, Ou D, Mak C M. The impact of indoor environmental quality on work productivity in university open-plan research offices. Building and Environment 2017, 124, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theory | Author | Time | Content | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theories related to attention recovery | Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) | Roger Ulrich | 1979 | When an individual is in a state of stress or stress, exposure to some natural environment can alleviate the physical, psychological, and behavioral damage caused by the stressor. | |

| Attention Restorative Theory (ART) | Autonomous attention and involuntary attention concepts | William James | 1892 | William James developed the concept of voluntary attention and involuntary attention. When the object itself is not attractive but has to pay attention to it, people mobilize autonomous attention, and vice versa. | |

| Concept of directed attention | Messalam | 1985 | Directed Attention, which is similar to Directed attention, is considered important for human health in modern neuro medicine. | ||

| Put forward the theory and the characteristics of the recovery environment | Stephen Kaplan | 1983 | To refine the theoretical framework and fascination, the Kaplans added three other features of the restorative environment -- being away, extent, and compatibility. | ||

| Psychological perspectives and natural experience | Stephen Kaplan | 1989 | The environment restores directed attention by providing certain qualities and provides individuals with opportunities for contemplation. This process is called a restorative experience. Accordingly, such an environment is a restorative environment. | ||

| Integration of the natural recovery benefit framework | Stephen Kaplan | 1995 | Strong and continuous use of directed attention will lead to the consumption of this resource, making individuals frequent errors and impulsive behavior, but in a restorative environment, individuals can effectively recover attention. | ||

| Effect Object | Effector | Effect Mechanism | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject Word | Total | Centrality | Subject Word | Total | Centrality | Subject Word | Total | Centrality |

| Stress | 142 | 0.03 | Environment | 149 | 0.1 | Benefit | 174 | 0.09 |

| Preference | 108 | 0.08 | Restorative Environment | 99 | 0.06 | Exposure | 121 | 0.09 |

| Health | 106 | 0.08 | Green Space | 48 | 0.09 | Restoration | 90 | 0.06 |

| Attention | 74 | 0.17 | Urban | 44 | 0.02 | Stress Recovery | 69 | 0.07 |

| Response | 54 | 0.12 | Natural Environment | 42 | 0.05 | Experience | 60 | 0.08 |

| Perception | 42 | 0.05 | Landscape | 42 | 0.1 | Perceived Restorativeness | 56 | 0.06 |

| Mental Health | 37 | 0.02 | Biodiversity | 36 | 0.06 | Psychological Restoration | 53 | 0.03 |

| Performance | 24 | 0.04 | Virtual Reality | 28 | 0.01 | Attention Restoration | 45 | 0.03 |

| Human Health | 15 | 0.01 | Forest | 26 | 0.02 | Impact | 28 | 0.03 |

| Anxiety | 12 | 0.04 | Space | 21 | 0.04 | Association | 22 | 0.01 |

| Author | Publication Time | Cited Frequency | Article Title | Research Content |

| Markevych | 2017 | 866 | Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance | The paper explores the interdisciplinary evidence linking green spaces to health. |

| Keniger, LE | 2013 | 556 | What are the Benefits of Interacting with Nature? | The study constructs new typologies of human-nature experiences and employs them to assess the benefits of human-nature interaction. |

| Bratman, GN | 2012 | 526 | The impacts of nature’s experience on human cognitive function and mental health | The synthesis of multiple disciplines outlines how exposure to nature and an individual’s preference for nature may influence the impact of the environment on mental functioning. |

| Tyrvainen, L | 2014 | 499 | The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment | The paper experimentally investigated the psychological and physiological effects of short-term visits to urban natural environments. |

| Bratman, GN | 2019 | 461 | Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective | The paper extends the assessment of ecosystem services to mental health and proposes a heuristic conceptual model for this purpose. |

| Berman, MG | 2012 | 389 | Interacting with nature improves cognition and affects individuals with depression | The study experimentally investigated the benefits of nature walks in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). |

| Carrus, G | 2015 | 387 | Go greener, feel better? The positive effects of biodiversity on the well-being of individuals visiting, urban and peri-urban green areas | Field studies assessed the benefits and subjective well-being of urban residents accessing four different types of green space. |

| Ohly, H | 2016 | 260 | Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments | The study experimentally explores the mechanism of environmental restorative experience. |

| Ratcliffe, E | 2013 | 204 | Bird sounds and their contributions to perceived attention restoration and stress recovery | The study found a relationship between bird calls, the most common type of sound in nature, and attention recovery. |

| Van den Berg, AE | 2014 | 193 | Evaluating restoration in urban green spaces: Does setting type make a difference? | The study examines the storability of urban public spaces with varying degrees of greening. The results indicate that the restoration of urban public spaces depends on individuals’ perceived needs and the physical characteristics of the environment. |

| Theory | Author | Time | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRICE | Hartig | 1997 | To measure the restorative nature of human-environment interaction, Hartig et al. developed the Perceptual Recovery Scale (PRS) to measure the quality of the restorative environment. |

| RCS | Laumann | 2001 | To make up for the shortcomings of PRS, Laumann et al. developed another set of environmental recovery component rating scales, which was named as Recovery Component Scale (RCS) in subsequent studies. |

| RS | Han K T. | 2003 | Han K T et al. developed a reliable and effective self-assessment method for the quality of natural environment restoration, called the self-assessment Restoration Scale (RS). |

| PRCQ | Pals | 2009 | Pals et al. believe that zoos have restorative features in addition to natural environments. Based on PRS and RCS, they designed the Perceptual restorative Feature Scale (PRCQ) for five kinds of restorative features of zoo attractions. |

| PDRQ | Lehto | 2013 | From the perspective of tourists, based on the theory of attention recovery, a 30-item PDRQ was developed. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).