Submitted:

24 March 2024

Posted:

26 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

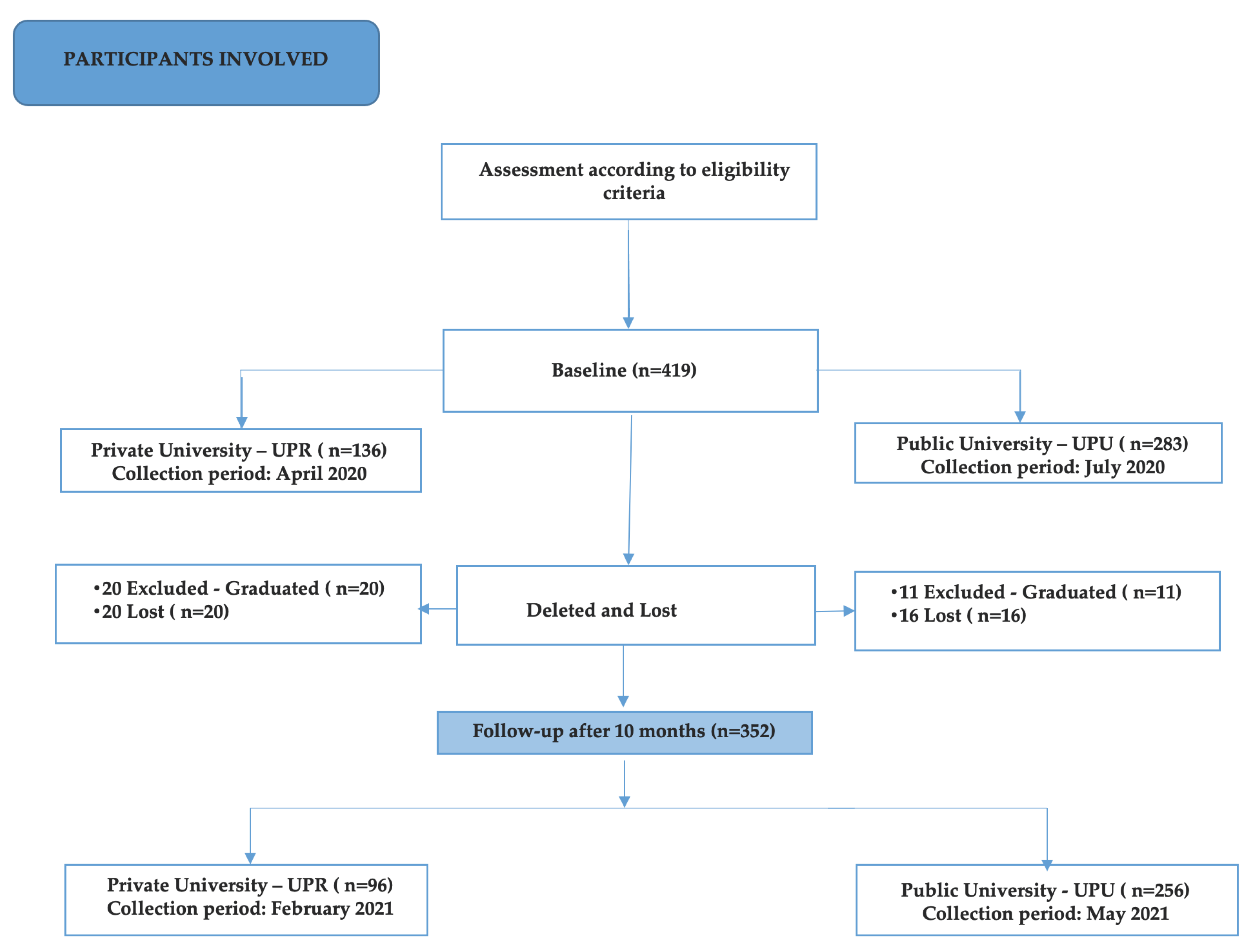

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Sociodemographic Data

2.5. Assessment of Sleep and Drowsiness

2.6. Stress Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castioni R, Melo AAS de, Nascimento PM, Ramos DL. Federal universities in the Covid-19 pandemic: student access to the internet and 12 emergency remote teaching Essay: avalpolpúblEduc [Internet]. 2021Apr;29(111):399–419. [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti LMR, Guerra M das GGV. The challenges of public universities post-Covid-19 pandemic: the Brazilian case. Essay: avalpolpúblEduc [Internet]. 2022Jan;30(114):73–93. [CrossRef]

- Çelik N, Ceylan B, Ünsal A, Çağan Ö. Depression in health college students: relationship factors and sleep quality. Psychol Health Med. 2019Jun;24(5):625-630. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco JP, Giacomin HT, Tam WW, Ribeiro TB, Arab C, Bezerra IM, Pinasco GC.Mental health problems among medical students in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Psychiatry. 2017 Oct Dec;39(4):369-378. [CrossRef]

- Basudan S, Binanzan N, Alhassan A. Depression, anxiety and stress in dental students. Int J Med Educ. 2017 May 24;8:179-186. [CrossRef]

- 6. León-Manco RA, Agudelo -Suárez AA, Armas -Vega A, Figueiredo MC, Verdugo- PaivaF , Santana-Pérez Y, Viteri -García A. Perceived Stress in Dentists and Dental Students of Latin America and the Caribbean during the Mandatory Social Isolation Measures for the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 May 30;18(11):5889. [CrossRef]

- Wright KP Jr, Linton SK, Withrow D, Casiraghi L, Lanza SM, Iglesia H, Vetter C, Depner CM. Sleep in university students prior to and during COVID-19 Stay-at-Home orders. Curr Biol. 2020 Jul 20;30(14):R797-R798. [CrossRef]

- Du C, Adjepong M, Zan MCH, Cho MJ, Fenton JI, Hsiao PY, Keaver L, Lee H, LudyMJ, Shen W, Swee WCS, Thrivikraman J, Amoah-Agyei F, de Kanter E, Wang W, TuckerRM. Gender Differences in the Relationships between Perceived Stress, Eating Behaviors, Sleep, Dietary Risk, and Body Mass Index. Nutrients. 2022 Feb28;14(5):1045. [CrossRef]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP;STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014 Dec;12(12):1495-9. [CrossRef]

- Bertolazi AN, Fagondes SC, Hoff LS, Dartora EG, Miozzo IC, de Barba ME, Barreto SS. Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Sleep Med. 2011 Jan;12(1):70-5. [CrossRef]

- Bertolazi AN, Fagondes SC, Hoff LS, Pedro VD, Menna Barreto SS, Johns MW.Portuguese -language version of the Epworth sleepiness scale: validation for use in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2009 Sep;35(9):877-83. English, Portuguese. [CrossRef]

- Luft CD, Sanches Sde O, Mazo GZ, Andrade A. Brazilian version of the Perceived Stress Scale: translation and validation for the elderly [ Brazilian version of the Perceived Stress Scale : translation and validation for the elderly ]. rev Public health. 2007 Aug;41(4):606-15. Portuguese. [CrossRef]

- Sott MK, Bender MS, da Silva Baum K. Covid-19 Outbreak in Brazil: Health, Social, Political, and Economic Implications. Int J Health Serv. 2022Oct;52(4):442-454. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues EC, Mendonça RD, Camargo PP, Menezes MC, Carvalho NC, Meireles AL. Home food insecurity during the suspension of classes in Brazilian public schools due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrition. 2022 Jan;93:111448. Erratum in: Nutrition. 2022 Mar;95:111563. [CrossRef]

- Ramos Socarras L, Potvin J, Forest G. COVID-19 and sleep patterns in adolescents and young adults. Sleep Med. 2021 Jul;83:26 -33. [CrossRef]

- Smit AN, Juda M, Livingstone A, U SR, Mistlberger RE. Impact of COVID-19 social-distancing on sleep timing and duration during a university semester. PloS One. 2021 Apr 26;16(4):e 0250793. [CrossRef]

- Benham G. Stress and sleep in college students prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stress Health. 2021 Aug;37(3):504-515. [CrossRef]

- Alyoubi A, Halstead EJ, Zambelli Z, Dimitriou D. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Students' Mental Health and Sleep in Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Sep 4;18(17):9344. [CrossRef]

- Henning K, Ey S, Shaw D. Perfectionism, the imposter phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. MedEduc. 1998 Sep;32(5):456-64. [CrossRef]

- 20. Basudan S, Binanzan N, Alhassan A. Depression, anxiety and stress in dental students. Int J Med Educ. 2017 May 24;8:179-186. [CrossRef]

- Marelli S, Castelnuovo A, Somma A, Castronovo V, Mombelli S, Bottoni D,Leitner C, Fossati A, Ferini-Strambi L. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on sleep quality in university students and administration staff. J Neurol. 2021Jan;268(1):8-15. [CrossRef]

- Gusman MS, Grimm KJ, Cohen AB, Doane LD. Stress and sleep across the onset of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: impact of distance learning on US college students' health trajectories. Sleep. 2021 Dec 10;44(12 ):zsab 193. [CrossRef]

- Pelucio L, Simões P, Dourado MCN, Quagliato LA, Nardi AE. Depression and anxiety among online learning students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. BMC Psychol. 2022 Aug 3;10(1):192. [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani JS, AlRabeeah SM, Aldhahir AM, Siraj R, Aldabayan YS, Alghamdi SM,Alqahtani AS, Alsaif SS, Naser AY, Alwafi H. Sleep Quality, Insomnia, Anxiety, Fatigue, Stress, Memory and Active Coping during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Apr 19;19(9):4940. [CrossRef]

- Ghrouz AK, Noohu MM, Dilshad Manzar M, Warren Spence D, Ba Hammam AS, Pandi -Perumal SR. Physical activity and sleep quality in relation to mental health among college students. Sleep Breath. 2019 Jun;23(2):627-634. [CrossRef]

- Du C, Zan MCH, Cho MJ, Fenton JI, Hsiao PY, Hsiao R, Keaver L, Lai CC, Lee H, Ludy MJ, Shen W, Swee WCS, Thrivikraman J, Tseng KW, Tseng WC, Doak S, Folk SYL,Tucker RM. The Effects of Sleep Quality and Resilience on Perceived Stress, Dietary Behaviors, and Alcohol Misuse: A Mediation-Moderation Analysis of Higher Education Students from Asia, Europe, and North America during the COVID-19Pandemic. Nutrients. 2021 Jan 29;13(2):442. [CrossRef]

- Kumar N, Gupta R. Disrupted Sleep During a Pandemic. Sleep Med Clin. 2022Mar;17(1):41-52. [CrossRef]

- Lu P, Yang L, Wang C, Xia G, Xiang H, Chen G, Jiang N, Ye T, Pang Y, Sun H, Yan L, Su Z, Heyworth J, Huxley R, Fisher J, Li S, Guo Y. Mental health of new undergraduate students before and after COVID-19 in China. Sci Rep. 2021 Sep22;11(1):18783. [CrossRef]

- Neculicioiu VS, Colosi IA, Costache C, Sevastre-Berghian A, Clichici S. Time to Sleep?- A Review of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sleep and MentalHealth. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Mar 16;19(6):3497. [CrossRef]

- Kilius E, Abbas NH, McKinnon L, Samson DR. Pandemic Nightmares: COVID-19Lockdown Associated With Increased Aggression in Female University Students'Dreams. Front Psychol. 2021 Mar 5;12:644636. [CrossRef]

- Genta FD, Rodrigues Neto GB, Sunfeld JPV, Porto JF, Xavier AD, Moreno CRC, Lorenzi -Filho G, Genta PR. COVID-19 pandemic impact on sleep habits, chronotype, and health-related quality of life among high school students: a longitudinal study. J Clin Sleep Med 2021 Jul 1;17(7):1371-1377. [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriou A, Rokou A, Arvaniti A, Nena E, Steiropoulos P. Sleep Quality and Mental Health of Medical Students in Greece During the COVID-19 Pandemic. FrontPublic Health. 2021 Nov 19;9:775374. [CrossRef]

- Paiva T, Reis C, Feliciano A, Canas-Simião H, Machado MA, Gaspar T, Tomé G, Branquinho C, Silva MR, Ramiro L, Gaspar S, Bentes C, Sampaio F, Pinho L, Pereira C, Carreiro A, Moreira S, Luzeiro I, Pimentel J, Videira G, Fonseca J, Bernarda A, Vaz Castro J, Rebocho S, Almondes K, Canhão H, Matos MG. Sleep and Awakening Quality during COVID-19 Confinement: Complexity and Relevance for Health and Behavior. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Mar 28;18(7 ):3506. [CrossRef]

- Viselli L, Salfi F, D'Atri A, Amicucci G, Ferrara M. Sleep Quality, Insomnia Symptoms, and Depressive Symptomatology among Italian University Students before and during the Covid-19 Lockdown. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Dec18;18(24):13346. [CrossRef]

- Stone JE, Phillips AJK, Chachos E, Hand AJ, Lu S, Carskadon MA, Klerman EB, Lockley SW, Wiley JF, Bei B, Rajaratnam SMW; CLASS Study Team. In-person vs home schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: Differences in sleep, circadian timing, and mood in early adolescence. J Pineal Res. 2021 Sep;71(2 ):e 12757. [CrossRef]

- Galindo- Aldana GM, Padilla-López LA, Torres-González C, García-León IA, Padilla -Bautista JA, Alvarez- Núñez DN. Effects of Socio-Familial Behavior on Sleep Quality Predictive Risk Factors in Individuals under Social Isolation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Mar 20;19(6):3702. [CrossRef]

- Saguem BN, Nakhli J, Romdhane I, Nasr SB. Predictors of sleep quality in medical students during COVID-19 confinement. Encephale. 2022 Feb;48(1 ):3-12. [CrossRef]

- Blume M, Rattay P. Association between Physical Activity and Sleep Difficulties among Adolescents in Germany: The Role of Socioeconomic Status. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Sep 14;18(18):9664. [CrossRef]

- Markofski MM, Jennings K, Hodgman CF, Warren VE, LaVoy EC. Physical activity during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is linked to improved mood and emotion. Stress Health. 2022 Aug;38(3):490-499. [CrossRef]

- Muradyan A, Macheiner T, Mardiyan M, Sekoyan E, Sargsyan K. The Evaluation of Biomarkers of Physical Activity on Stress Resistance and Wellness. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2022 Jun;47(2):121-129. [CrossRef]

- Albert KM, Newhouse PA. Estrogen, Stress, and Depression: Cognitive and Biological Interactions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2019 May 7;15:399-423. [CrossRef]

- Sikka N, Juneja R, Kumar V, Bala S. Effect of Dental Environmental Stressors and Coping Mechanisms on Perceived Stress in Postgraduate Dental Students. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2021 Sep-Oct;14(5):681-688. [CrossRef]

- Rijal D, Paudel K, Adhikari TB, Bhurtyal A. Stress and coping strategies among higher secondary and undergraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023 Feb 15;3(2 ):e 0001533. [CrossRef]

- Michaeli D, Keough G, Perez-Dominguez F, Polanco- Ilabaca F, Pinto-Toledo F, Michaeli J, Albers S, Achiardi J, Santana V, Urnelli C, Sawaguchi Y, RodríguezP, Maldonado M, Raffeeq Z, de Araujo Madeiros O, Michaeli T. Medical education and mental health during COVID-19: a survey across 9 countries. Int J Med Educ.2022 Feb 26;13:35 -46. [CrossRef]

- Fawaz M, Samaha A. E-learning: Depression, anxiety, and stress symptomatology among Lebanese university students during COVID-19 quarantine. Nurs Forum. 2021Jan;56(1):52-57. [CrossRef]

- Dpereira MB, Casagrande AV, Almeida BC, Neves BA, da Silva TCRP, Miskulin FPC, Perissotto T, Ribeiz SRI, Nunes PV. Mental Health of Medical Students Before and During COVID-19 Pandemic: a 3-Year Prospective Study. Med Sci Educ. 2022 Jun29;32(4):873-881. [CrossRef]

- David MCMM, Vieira GR, Leôncio LML, Neves LDS, Bezerra CG, Mattos MSB, Santos NFD, Santana FH, Antunes RB, Araújo JF, Matos RJB. Predictors of stress in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord Rep. 2022 Dec;10:100377. [CrossRef]

- Raccanello D, Balbontín -Alvarado R, Bezerra DDS, Burro R, Cheraghi M, Dobrowolska B, Fagbamigbe AF, Faris ME, França T, González-Fernández B, Hall R, Inasius F, Kar SK, Keržič D, Lazányi K, Lazăr F, Machin- Mastromatteo JD, MarôcoJ, Marques BP, Mejía-Rodríguez O, Méndez Prado SM, Mishra A, Mollica C, NavarroJiménez SG, Obadić A, Mamun-Ur-Rashid M, Ravšelj D, Tatalović Vorkapić S,Tomaževič N, Uleanya C, Umek L, Vicentini G, Yorulmaz Ö, Zamfir AM, AristovnikA. Higher education students' achievement emotions and their antecedents in e-learning amid COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country survey. Learn Instr. 2022 Aug;80:101629. [CrossRef]

- Camargo CP, Tempski PZ, Busnardo FF, Martins MA, Gemperli R. Online learning and COVID-19: a meta-synthesis analysis. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2020 Nov6;75:e2286. [CrossRef]

| UPU (%) | UPR (%) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Feminine | 208 (73.5) | 101 (74.3) | 0.867 |

| Masculine | 75 (26.5) | 35 (25.7) | ||

| Race | Mixed race or brown | 75 (26.5) | 61(44.9) | <0.001 |

| White | 183 (64.7) | 60 (44.1) | ||

| Black | 21 (7.4) | 11 (8.1) | ||

| Yellow | 4 (1.4) | 4 (2.9) | ||

| marital status | Single | 279 (98.6) | 126 (92.6) | 0.006 |

| Married | 2 (0.7) | 6 (4.4) | ||

| Unity stable | 2 (0.7) | 4 (2.9) | ||

| Family income | up to 1 salary | 14 (4.9) | 7 (5.1) | 0.907 |

| +from 1 to 3 salaries | 91 (32.2) | 49 (36.0) | ||

| + from 3 to 5 salaries | 91 (32.2) | 39 (28.7) | ||

| + from 5 to 15 salaries | 73 (25.8) | 33 (24.3) | ||

| + 15 salaries | 14 (4.9) | 8 (5.9) | ||

| Lives with | Spouse | 15 (5.3) | 1 (0.7) | 0.229 |

| Parents / sibling | 242 (85.5) | 123 (90.4) | ||

| Relatives | 17 (6.0) | 9 (6.6) | ||

| Friends | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| Alone | 6 (2.1) | 2 (1.5) | ||

| Number of children | No he has son | 283 100.0) | 128 (94.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.4) | ||

| 2 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| 3 or more | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| Improved a little | 51 (19.9) | 19 (19.8) | 0.009 | |

| Improved very much | 29 (11.3) | 13 (13.5) | ||

| The relationship with the | It got a little worse | 43 (16.8) | 8 (8.3) | |

| people who live with | It got very worse | 8 (3.1) | 1 (1.0) | |

| you: | Stays the same | 118 (46.1) | 44 (45.8) | |

| I live alone | 7 (2.7) | 11 (11.5) | ||

| Comparing the beginning of the Pandemic with the current moment, please select the option that best represents you current health status | 1. I don't worry as much as I used to | 6 (2.3) | 3 (3.1) | 0.103 |

| 2. I worry more about my family than about myself | 155 (60.5) | 46 (47.9) | ||

| 3. I worry about myself and my family | 95 (37.1) | 47 (49.0) | ||

| Considering the Pandemic situation, select the option that best represents you professionally | 1. I worry a little because I will soon be part of the job market | 94 (36.7) | 53 (55.2) | <0.001 |

| 2. I have no concerns about this at the moment | 41 (16.0) | 4 (4.2) | ||

| 3. I have great concerns because the recession is big | 121 (47.3) | 39 (40.6) | ||

| Had COVID | Yes | 55 (21.5) | 27 (28.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 173 (67.6) | 43 (44.8) | ||

| Perhaps | 28 (10.9) | 26 (27.1) | ||

| I lost a family member or | Yes | 110 (43.0) | 49 (51.0) | 0.175 |

| friend | No | 146 (57.0) | 47 (49.0) |

| Parameter | Exp(B) | 95%CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University | UPR | 1,137 | 0.776 | 1,666 | 0.510 |

| UPU | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Gender | F | 1,064 | 0.726 | 1,560 | 0.750 |

| M | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Assessment moment _ | Baseline | 0.627 | 0.480 | 0.819 | 0.001 |

| 10 months | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Income | up to 1 salary | 3,229 | 0.966 | 10,799 | 0.057 |

| 1 to 3 salaries | 1,079 | 0.560 | 2,079 | 0.820 | |

| 3 to 5 salaries | 1,085 | 0.554 | 2,126 | 0.812 | |

| 5 to 15 salaries | 0.876 | 0.447 | 1,718 | 0.700 | |

| + 15 salaries | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Relationship with household members | I live alone | 1,179 | 0.388 | 3,581 | 0.771 |

| It got worse very | 2,292 | 0.809 | 6,496 | 0.119 | |

| It got a little worse | 1,665 | 0.881 | 3,145 | 0.116 | |

| Stays the same | 0.890 | 0.538 | 1,473 | 0.650 | |

| Improved a little | 0.738 | 0.407 | 1,338 | 0.317 | |

| Very improved | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Routine | Only study | .667 | 0.405 | 1,096 | 0.110 |

| Study and others activities | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Physical activity | No | 1,303 | 0.955 | 1,778 | 0.095 |

| Yes | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Parameter | Exp(B) | 95%CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University | UPR | 0.881 | 0.612 | 1,269 | 0.496 |

| UPU | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Gender | F | 1,736 | 1,149 | 2,622 | 0.009 |

| M | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Assessment moment | Baseline | 0.579 | 0.454 | 0.737 | <0.001 |

| 10 months | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Income | up to 1 salary | 3,266 | 1,241 | 8,594 | 0.017 |

| 1 to 3 salaries | 1,355 | 0.661 | 2,777 | 0.407 | |

| 3 to 5 salaries | 1,487 | 0.719 | 3,075 | 0.285 | |

| 5 to 15 salaries | 0.894 | 0.429 | 1,860 | 0.764 | |

| + 15 salaries | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Relationship with household members | I live alone | 1,352 | 0.547 | 3,340 | 0.514 |

| It got very worse | 1,529 | 0.610 | 3,829 | 0.365 | |

| It got a little worse | 0.928 | 0.512 | 1,682 | 0.806 | |

| Stays the same | 0.710 | 0.435 | 1,160 | 0.171 | |

| Improved a little | 0.818 | 0.467 | 1,436 | 0.485 | |

| Improved very | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Routine | Only study | .787 | 0.493 | 1,257 | 0.317 |

| Study and others activities | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Activity physical | No | 1,411 | 1,039 | 1,917 | 0.027 |

| Yes | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Parameter | Exp(B) | 95% CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University | UPR | 0.093 | 0.013 | 0.680 | 0.019 |

| UPU | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Gender | F | 38,264 | 6,357 | 230,304 | 0.001 |

| M | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Assessment moment | Baseline | 1,535 | 0.483 | 4,879 | 0.468 |

| 10 months | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Income | up to 1 salary | 2,413 | 0.055 | 106,059 | 0.648 |

| 1 to 3 salaries | 5,200 | 0.392 | 68,971 | 0.211 | |

| 3 to 5 salaries | 4,833 | 0.364 | 64,087 | 0.232 | |

| 5 to 15 salaries | 2,982 | 0.237 | 37,582 | 0.398 | |

| + 15 salaries | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Relationship with household members | I live alone | 2,390 | 0.020 | 290,518 | 0.722 |

| It got very worse | 1233.357 | 17,872 | 85116.035 | 0.001 | |

| It got a little worse | 26,878 | 1,714 | 421,372 | 0.019 | |

| Stays the same | 0.986 | 0.114 | 8,552 | 0.990 | |

| Improved a little | 1,141 | 0.091 | 14,249 | 0.919 | |

| Improved very | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Routine | Only study | 0.200 | 0.020 | 1,984 | 0.169 |

| Study and others activities | 1 | . | . | . | |

| Activity physical | No | 7,800 | 1,786 | 34,077 | 0.006 |

| Yes | 1 | . | . | . | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).