Submitted:

25 March 2024

Posted:

27 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Rotavirus

2. Viroplasms

2.1. Spatial and Temporal Organization

2.2. Replication Steps within Viroplasms

2.2. NSP5

2.2. NSP2

2.5. VP2

3. Host Cell Cytoskeleton

3.1. Microtubules

3.1. MT-Dependent Molecular Motors

3.1. Actin

3.4. Actin-Dependent Molecular Motors

3.5. Intermediate Filaments

3.6. Viroplasm Interaction with Host Components

4. Viral Factories Interaction with Host Components of Other dsRNA Viruses

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams WR, Kraft LM: Epizootic Diarrhea of Infant Mice: Identification of the Etiologic Agent. Science 1963, 141:359-360. [CrossRef]

- Bishop RF, Davidson GP, Holmes IH, Ruck BJ: Virus particles in epithelial cells of duodenal mucosa from children with acute non-bacterial gastroenteritis. The Lancet 1973, 302:1281-1283. [CrossRef]

- Crawford SE, Ramani S, Tate JE, Parashar UD, Svensson L, Hagbom M, Franco MA, Greenberg HB, O'Ryan M, Kang G, et al: Rotavirus infection. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2017, 3:1-16.

- Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD, Duque J, Parashar UD: 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2012, 12:136-141. [CrossRef]

- Vesikari T, Karvonen A, Prymula R, Schuster V, Tejedor JC, Cohen R, Meurice F, Han HH, Damaso S, Bouckenooghe A: Efficacy of human rotavirus vaccine against rotavirus gastroenteritis during the first 2 years of life in European infants: randomised, double-blind controlled study. The Lancet 2007, 370:1757-1763.

- Hallowell BD, Tate J, Parashar U: An overview of rotavirus vaccination programs in developing countries. Expert Review of Vaccines 2020, 19:529-537. [CrossRef]

- Fauquet CM: Taxonomy, Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. Encyclopedia of Virology 2008.

- Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA: Virus taxonomy: VIIIth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press; 2005.

- Lefkowitz EJ, Dempsey DM, Hendrickson RC, Orton RJ, Siddell SG, Smith DB: Virus taxonomy: the database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46:D708-D717. [CrossRef]

- Matthijnssens J, Theuns S: Minutes of the 7th Rotavirus Classification Working Group (RCWG) Meeting. In 12th International Double Stranded RNA Virus Symposium; Goa Marriott Beach Resort & Spa, Goa, India. 2015.

- Johne R, Tausch SH, Ulrich RG, Schilling-Loeffler K: Genome analysis of the novel putative rotavirus species K. Virus Research 2023, 334:199171. [CrossRef]

- Johne R, Schilling-Loeffler K, Ulrich RG, Tausch SH: Whole Genome Sequence Analysis of a Prototype Strain of the Novel Putative Rotavirus Species L. In Viruses, vol. 142022. [CrossRef]

- Asensio-Cob D, Rodríguez JM, Luque D: Rotavirus Particle Disassembly and Assembly In Vivo and In Vitro. Viruses 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Prasad BVV, Wang GJ, Clerx JPM, Chiu W: Three-dimensional structure of rotavirus. Journal of Molecular Biology 1988, 199:269-275. [CrossRef]

- Pesavento JB, Crawford SE, Estes MK, Venkataram Prasad BV: Rotavirus Proteins: Structure and Assembly. In Reoviruses: Entry, Assembly and Morphogenesis. Edited by Roy P. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2006: 189-219.

- Dormitzer PR, Sun ZY, Wagner G, Harrison SC: The rhesus rotavirus VP4 sialic acid binding domain has a galectin fold with a novel carbohydrate binding site. EMBO J 2002, 21:885-897. [CrossRef]

- Isa P, López S, Segovia L, Arias CF: Functional and structural analysis of the sialic acid-binding domain of rotaviruses. Journal of Virology 1997, 71:6749-6756. [CrossRef]

- Isa P, Arias CF, López S: Role of sialic acids in rotavirus infection. Glycoconjugate Journal 2006, 23:27-37. [CrossRef]

- Huang P, Xia M, Tan M, Zhong W, Wei C, Wang L, Morrow A, Jiang X: Spike Protein VP8* of Human Rotavirus Recognizes Histo-Blood Group Antigens in a Type-Specific Manner. Journal of Virology 2012, 86:4833-4843. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez M, Isa P, Sánchez-San Martin C, Pérez-Vargas J, Espinosa R, Arias CF, López S: Different Rotavirus Strains Enter MA104 Cells through Different Endocytic Pathways: the Role of Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis. Journal of Virology 2010, 84:9161-9169. [CrossRef]

- Li B, Ding S, Feng N, Mooney N, Ooi YS, Ren L, Diep J, Kelly MR, Yasukawa LL, Patton JT, et al: Drebrin restricts rotavirus entry by inhibiting dynamin-mediated endocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114:E3642-E3651.

- Arias CF, Silva-Ayala D, López S: Rotavirus Entry: a Deep Journey into the Cell with Several Exits. Journal of Virology 2015, 89:890-893. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Salinas Marco A, Silva-Ayala D, López S, Arias Carlos F: Rotaviruses Reach Late Endosomes and Require the Cation-Dependent Mannose-6-Phosphate Receptor and the Activity of Cathepsin Proteases To Enter the Cell. Journal of Virology 2014, 88:4389-4402.

- Golantsova Nina E, Gorbunova Elena E, Mackow Erich R: Discrete Domains within the Rotavirus VP5* Direct Peripheral Membrane Association and Membrane Permeability. Journal of Virology 2004, 78:2037-2044.

- Patton JT, Silvestri LS, Tortorici MA, Carpio V-D, Taraporewala ZF: Rotavirus genome replication and morphogenesis: role of the viroplasm. Reoviruses: entry, assembly and morphogenesis 2006:169-187.

- Lawton JA, Estes MK, Prasad BVV: Three-dimensional visualization of mRNA release from actively transcribing rotavirus particles. Nature Structural Biology 1997, 4:118-121. [CrossRef]

- Petrie BL, Graham DY, Hanssen H, Estes MK: Localization of rotavirus antigens in infected cells by ultrastructural immunocytochemistry. Journal of General Virology 1982, 63:457-467. [CrossRef]

- Arnold Michelle M: The Rotavirus Interferon Antagonist NSP1: Many Targets, Many Questions. Journal of Virology 2016, 90:5212-5215.

- Padilla-Noriega L, Paniagua O, Guzmán-León S: Rotavirus protein NSP3 shuts off host cell protein synthesis. Virology 2002, 298:1-7. [CrossRef]

- Morelli M, Ogden KM, Patton JT: Silencing the alarms: Innate immune antagonism by rotavirus NSP1 and VP3. Virology 2015, 479-480:75-84. [CrossRef]

- Taylor JA, O'Brien JA, Lord VJ, Meyer JC, Bellamy AR: The RER-Localized Rotavirus Intracellular Receptor: A Truncated Purified Soluble Form Is Multivalent and Binds Virus Particles. Virology 1993, 194:807-814. [CrossRef]

- López T, Camacho M, Zayas M, Nájera R, Sánchez R, Arias Carlos F, López S: Silencing the Morphogenesis of Rotavirus. Journal of Virology 2005, 79:184-192. [CrossRef]

- Trask SD, McDonald SM, Patton JT: Structural insights into the coupling of virion assembly and rotavirus replication. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012, 10:165-177. [CrossRef]

- Shah PNM, Gilchrist JB, Forsberg BO, Burt A, Howe A, Mosalaganti S, Wan W, Radecke J, Chaban Y, Sutton G, et al: Characterization of the rotavirus assembly pathway in situ using cryoelectron tomography. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31:604-615.e604.

- Musalem C, Espejo RT: Release of Progeny Virus from Cells Infected with Simian Rotavirus SA11. Journal of General Virology 1985, 66:2715-2724. [CrossRef]

- Cevallos Porta D, López S, Arias CF, Isa P: Polarized rotavirus entry and release from differentiated small intestinal cells. Virology 2016, 499:65-71. [CrossRef]

- Gardet A, Breton M, Trugnan G, Chwetzoff S: Role for actin in the polarized release of rotavirus. J Virol 2007, 81:4892-4894. [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Cerro Ó, Eichwald C, Schraner EM, Silva-Ayala D, López S, Arias CF: Actin-Dependent Nonlytic Rotavirus Exit and Infectious Virus Morphogenetic Pathway in Nonpolarized Cells. Journal of Virology 2018, 92. [CrossRef]

- Altenburg BC, Graham DY, Kolb Estes M: Ultrastructural study of rotavirus replication in cultured cells. Journal of General Virology 1980, 46:75-85. [CrossRef]

- Contin R, Arnoldi F, Campagna M, Burrone OR: Rotavirus NSP5 orchestrates recruitment of viroplasmic proteins. J Gen Virol 2010, 91:1782-1793. [CrossRef]

- Cheung W, Gill M, Esposito A, Kaminski Clemens F, Courousse N, Chwetzoff S, Trugnan G, Keshavan N, Lever A, Desselberger U: Rotaviruses Associate with Cellular Lipid Droplet Components To Replicate in Viroplasms, and Compounds Disrupting or Blocking Lipid Droplets Inhibit Viroplasm Formation and Viral Replication. Journal of Virology 2010, 84:6782-6798. [CrossRef]

- Contin R, Arnoldi F, Mano M, Burrone OR: Rotavirus replication requires a functional proteasome for effective assembly of viroplasms. J Virol 2011, 85:2781-2792. [CrossRef]

- Lopez T, Silva-Ayala D, Lopez S, Arias CF: Replication of the Rotavirus Genome Requires an Active Ubiquitin-Proteasome System. Journal of Virology 2011, 85:11964-11971. [CrossRef]

- Vetter J, Papa G, Tobler K, Rodriguez Javier M, Kley M, Myers M, Wiesendanger M, Schraner Elisabeth M, Luque D, Burrone Oscar R, et al: The recruitment of TRiC chaperonin in rotavirus viroplasms correlates with virus replication. mBio 2024, 0:e00499-00424.

- Gonzalez RA, Espinosa R, Romero P, Lopez S, Arias CF: Relative localization of viroplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum-resident rotavirus proteins in infected cells. Archives of virology 2000, 145:1963-1973. [CrossRef]

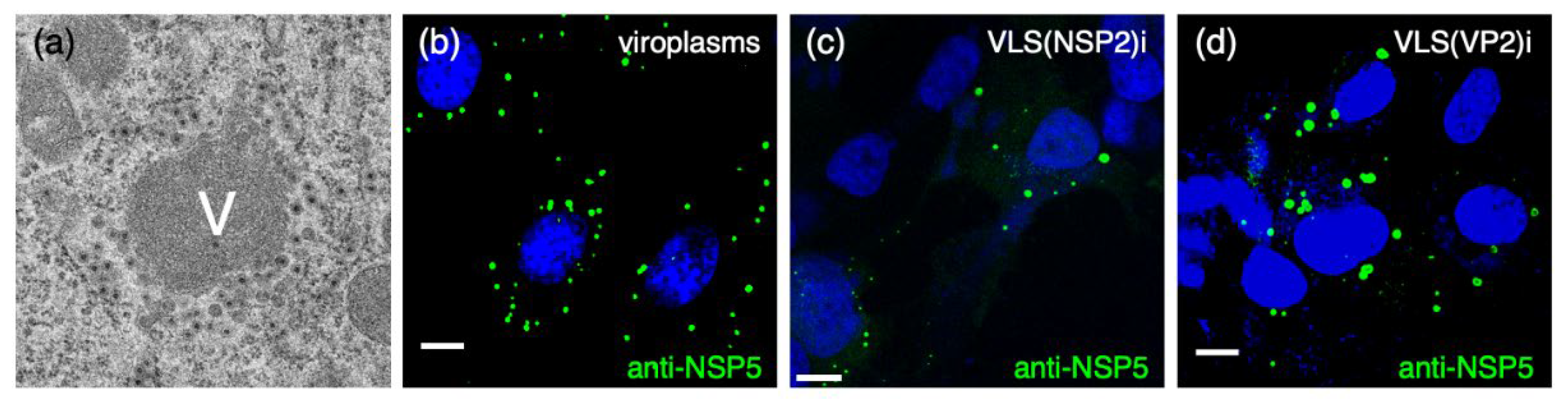

- Eichwald C, Rodriguez JF, Burrone OR: Characterization of rotavirus NSP2/NSP5 interactions and the dynamics of viroplasm formation. J Gen Virol 2004, 85:625-634.

- Carreño-Torres JJ, Gutiérrez M, Arias CF, López S, Isa P: Characterization of viroplasm formation during the early stages of rotavirus infection. Virol J 2010, 7:350. [CrossRef]

- Eichwald C, Arnoldi F, Laimbacher AS, Schraner EM, Fraefel C, Wild P, Burrone OR, Ackermann M: Rotavirus viroplasm fusion and perinuclear localization are dynamic processes requiring stabilized microtubules. PLoS One 2012, 7:e47947. [CrossRef]

- Geiger F, Acker J, Papa G, Wang X, Arter WE, Saar KL, Erkamp NA, Qi R, Bravo JPK, Strauss S, et al: Liquid–liquid phase separation underpins the formation of replication factories in rotaviruses. The EMBO Journal 2021, 40:e107711.

- Fabbretti E, Afrikanova I, Vascotto F, Burrone OR: Two non-structural rotavirus proteins, NSP2 and NSP5, form viroplasm-like structures in vivo. J Gen Virol 1999, 80 ( Pt 2):333-339.

- Borodavka A, Dykeman EC, Schrimpf W, Lamb DC: Protein-mediated RNA folding governs sequence-specific interactions between rotavirus genome segments. eLife 2017, 6:e27453.

- Patton JT, Jones MT, Kalbach AN, He YW, Xiaobo J: Rotavirus RNA polymerase requires the core shell protein to synthesize the double-stranded RNA genome. J Virol 1997, 71:9618-9626. [CrossRef]

- Periz J, Celma C, Jing B, Pinkney JN, Roy P, Kapanidis AN: Rotavirus mRNAS are released by transcript-specific channels in the double-layered viral capsid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110:12042-12047.

- Ruiz MC, Leon T, Diaz Y, Michelangeli F: Molecular Biology of Rotavirus Entry and Replication. TheScientificWorldJOURNAL 2009, 9:879851. [CrossRef]

- Campagna M, Eichwald C, Vascotto F, Burrone OR: RNA interference of rotavirus segment 11 mRNA reveals the essential role of NSP5 in the virus replicative cycle. J Gen Virol 2005, 86:1481-1487. [CrossRef]

- Martin D, Ouldali M, Ménétrey J, Poncet D: Structural organisation of the rotavirus nonstructural protein NSP5. J Mol Biol 2011, 413:209-221. [CrossRef]

- Martin D, Charpilienne A, Parent A, Boussac A, D'Autreaux B, Poupon J, Poncet D: The rotavirus nonstructural protein NSP5 coordinates a [2Fe-2S] iron-sulfur cluster that modulates interaction to RNA. FASEB J 2013, 27:1074-1083. [CrossRef]

- Eichwald C, Jacob G, Muszynski B, Allende JE, Burrone OR: Uncoupling substrate and activation functions of rotavirus NSP5: phosphorylation of Ser-67 by casein kinase 1 is essential for hyperphosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101:16304-16309. [CrossRef]

- Eichwald C, Vascotto F, Fabbretti E, Burrone OR: Rotavirus NSP5: mapping phosphorylation sites and kinase activation and viroplasm localization domains. J Virol 2002, 76:3461-3470. [CrossRef]

- Afrikanova I, Fabbretti E, Miozzo MC, Burrone OR: Rotavirus NSP5 phosphorylation is up-regulated by interaction with NSP2. J Gen Virol 1998, 79 ( Pt 11):2679-2686. [CrossRef]

- Campagna M, Budini M, Arnoldi F, Desselberger U, Allende JE, Burrone OR: Impaired hyperphosphorylation of rotavirus NSP5 in cells depleted of casein kinase 1alpha is associated with the formation of viroplasms with altered morphology and a moderate decrease in virus replication. J Gen Virol 2007, 88:2800-2810. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Vega MA, González RA, Duarte M, Poncet D, López S, Arias CF: The C-terminal domain of rotavirus NSP5 is essential for its multimerization, hyperphosphorylation and interaction with NSP6. J Gen Virol 2000, 81:821-830. [CrossRef]

- Arnoldi F, Campagna M, Eichwald C, Desselberger U, Burrone OR: Interaction of rotavirus polymerase VP1 with nonstructural protein NSP5 is stronger than that with NSP2. J Virol 2007, 81:2128-2137. [CrossRef]

- Papa G, Venditti L, Arnoldi F, Schraner EM, Potgieter C, Borodavka A, Eichwald C, Burrone OR: Recombinant rotaviruses rescued by reverse genetics reveal the role of NSP5 hyperphosphorylation in the assembly of viral factories. Journal of Virology 2020, 94:1-23. [CrossRef]

- Bar-Magen T, Spencer E, Patton JT: An ATPase activity associated with the rotavirus phosphoprotein NSP5. Virology 2007, 369:389-399. [CrossRef]

- Silvestri LS, Taraporewala ZF, Patton JT: Rotavirus replication: plus-sense templates for double-stranded RNA synthesis are made in viroplasms. J Virol 2004, 78:7763-7774. [CrossRef]

- Taraporewala Z, Chen D, Patton JT: Multimers formed by the rotavirus nonstructural protein NSP2 bind to RNA and have nucleoside triphosphatase activity. J Virol 1999, 73:9934-9943. [CrossRef]

- Jayaram H, Taraporewala Z, Patton JT, Prasad BVV: Rotavirus protein involved in genome replication and packaging exhibits a HIT-like fold. Nature 2002, 417:311-315. [CrossRef]

- Taraporewala Zenobia F, Jiang X, Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Jayaram H, Prasad BVV, Patton John T: Structure-Function Analysis of Rotavirus NSP2 Octamer by Using a Novel Complementation System. Journal of Virology 2006, 80:7984-7994. [CrossRef]

- Chamera S, Wycisk K, Czarnocki-Cieciura M, Nowotny M: Cryo-EM structure of rotavirus B NSP2 reveals its unique tertiary architecture. Journal of Virology 2024, 0:e01660-01623. [CrossRef]

- Kattoura MD, Clapp LL, Patton JT: The rotavirus nonstructural protein, NS35, possesses RNA-binding activity in vitro and in vivo. Virology 1992, 191:698-708. [CrossRef]

- Kattoura MD, Chen X, Patton JT: The Rotavirus RNA-Binding Protein NS35 (NSP2) Forms 10S Multimers and Interacts with the Viral RNA Polymerase. Virology 1994, 202:803-813. [CrossRef]

- Bravo JPK, Bartnik K, Venditti L, Acker J, Gail EH, Colyer A, Davidovich C, Lamb DC, Tuma R, Calabrese AN, Borodavka A: Structural basis of rotavirus RNA chaperone displacement and RNA annealing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [CrossRef]

- Kumar M, Jayaram H, Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Jiang X, Taraporewala Zenobia F, Jacobson Raymond H, Patton John T, Prasad BVV: Crystallographic and Biochemical Analysis of Rotavirus NSP2 with Nucleotides Reveals a Nucleoside Diphosphate Kinase-Like Activity. Journal of Virology 2007, 81:12272-12284.

- Criglar Jeanette M, Crawford Sue E, Zhao B, Smith Hunter G, Stossi F, Estes Mary K: A Genetically Engineered Rotavirus NSP2 Phosphorylation Mutant Impaired in Viroplasm Formation and Replication Shows an Early Interaction between vNSP2 and Cellular Lipid Droplets. Journal of Virology 2020, 94:10.1128/jvi.00972-00920.

- Nichols SL, Nilsson EM, Brown-Harding H, LaConte LEW, Acker J, Borodavka A, McDonald Esstman S: Flexibility of the Rotavirus NSP2 C-Terminal Region Supports Factory Formation via Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation. J Virol 2023, 97:e0003923. [CrossRef]

- Montero H, Rojas M, Arias Carlos F, López S: Rotavirus Infection Induces the Phosphorylation of eIF2α but Prevents the Formation of Stress Granules. Journal of Virology 2008, 82:1496-1504. [CrossRef]

- Buttafuoco A, Michaelsen K, Tobler K, Ackermann M, Fraefel C, Eichwald C: Conserved Rotavirus NSP5 and VP2 Domains Interact and Affect Viroplasm. J Virol 2020, 94. [CrossRef]

- Akhmanova A, Steinmetz MO: Microtubule minus-end regulation at a glance. Journal of Cell Science 2019, 132:jcs227850. [CrossRef]

- Mitchison TJ: Localization of an Exchangeable GTP Binding Site at the Plus End of Microtubules. Science 1993, 261:1044-1047.

- Gittes F, Mickey B, Nettleton J, Howard J: Flexural rigidity of microtubules and actin filaments measured from thermal fluctuations in shape. Journal of Cell Biology 1993, 120:923-934. [CrossRef]

- Janke C, Bulinski JC: Post-translational regulation of the microtubule cytoskeleton: mechanisms and functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011, 12:773-786. [CrossRef]

- Westermann S, Weber K: Post-translational modifications regulate microtubule function. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2003, 4:938-948. [CrossRef]

- Reed NA, Cai D, Blasius TL, Jih GT, Meyhofer E, Gaertig J, Verhey KJ: Microtubule Acetylation Promotes Kinesin-1 Binding and Transport. Current Biology 2006, 16:2166-2172. [CrossRef]

- Alper Joshua D, Decker F, Agana B, Howard J: The Motility of Axonemal Dynein Is Regulated by the Tubulin Code. Biophysical Journal 2014, 107:2872-2880. [CrossRef]

- Goodson HV, Jonasson EM: Microtubules and Microtubule-Associated Proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2018, 10.

- Bodakuntla S, Jijumon AS, Villablanca C, Gonzalez-Billault C, Janke C: Microtubule-Associated Proteins: Structuring the Cytoskeleton. Trends in Cell Biology 2019, 29:804-819.

- Brandt R, Lee G: Orientation, assembly, and stability of microtubule bundles induced by a fragment of tau protein. Cell Motility 1994, 28:143-154. [CrossRef]

- Walczak CE, Shaw SL: A MAP for Bundling Microtubules. Cell 2010, 142:364-367. [CrossRef]

- Greber UF, Way M: A Superhighway to Virus Infection. Cell 2006, 124:741-754. [CrossRef]

- Walsh D, Naghavi MH: Exploitation of Cytoskeletal Networks during Early Viral Infection. Trends in Microbiology 2019, 27:39-50. [CrossRef]

- Eichwald C, Ackermann M, Nibert ML: The dynamics of both filamentous and globular mammalian reovirus viral factories rely on the microtubule network. Virology 2018, 518:77-86. [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto M, Cai D, Sugiyama M, Suzuki R, Aizaki H, Ryo A, Ohtani N, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Wakita T, et al: Functional association of cellular microtubules with viral capsid assembly supports efficient hepatitis B virus replication. Scientific Reports 2017, 7:10620.

- Jouvenet N, Monaghan P, Way M, Wileman T: Transport of African Swine Fever Virus from Assembly Sites to the Plasma Membrane Is Dependent on Microtubules and Conventional Kinesin. Journal of Virology 2004, 78:7990-8001. [CrossRef]

- Dodding MP, Way M: Coupling viruses to dynein and kinesin-1. The EMBO Journal 2011, 30:3527-3539. [CrossRef]

- Roberts AJ: Emerging mechanisms of dynein transport in the cytoplasm versus the cilium. Biochemical Society Transactions 2018, 46:967-982. [CrossRef]

- Roberts AJ, Kon T, Knight PJ, Sutoh K, Burgess SA: Functions and mechanics of dynein motor proteins. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2013, 14:713-713. [CrossRef]

- King SM: The dynein microtubule motor. In Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Cell Research, vol. 1496. pp. 60-75: Elsevier; 2000: 60-75.

- Taylor MP, Koyuncu OO, Enquist LW: Subversion of the actin cytoskeleton during viral infection. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2011 9:6 2011, 9:427-439. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez R, Holmes KC: Actin Structure and Function. Annual Review of Biophysics 2011, 40:169-186.

- Tojkander S, Gateva G, Lappalainen P: Actin stress fibers – assembly, dynamics and biological roles. Journal of Cell Science 2012, 125:1855-1864.

- Rajan S, Kudryashov DS, Reisler E: Actin Bundles Dynamics and Architecture. In Biomolecules, vol. 132023. [CrossRef]

- Meenderink LM, Gaeta IM, Postema MM, Cencer CS, Chinowsky CR, Krystofiak ES, Millis BA, Tyska MJ: Actin dynamics drive microvillar motility and clustering during brush border assembly. Developmental cell 2019, 50:545-556. e544.

- Lehtimäki JI, Rajakylä EK, Tojkander S, Lappalainen P: Generation of stress fibers through myosin-driven reorganization of the actin cortex. eLife 2021, 10:e60710.

- Geiger B, Spatz JP, Bershadsky AD: Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2009, 10:21-33.

- Matozo T, Kogachi L, de Alencar BC: Myosin motors on the pathway of viral infections. Cytoskeleton 2022, 79:41-63.

- Sellers JR, Heissler SM: Nonmuscle myosin-2 isoforms. Current Biology 2019, 29:R275-R278. [CrossRef]

- Leduc C, Etienne-Manneville S: Intermediate filaments in cell migration and invasion: the unusual suspects. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2015, 32:102-112. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson JE, Dechat T, Grin B, Helfand B, Mendez M, Pallari H-M, Goldman RD: Introducing intermediate filaments: from discovery to disease. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2009, 119:1763-1771.

- Herrmann H, Bär H, Kreplak L, Strelkov SV, Aebi U: Intermediate filaments: from cell architecture to nanomechanics. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2007, 8:562-573.

- Desselberger U: The significance of lipid droplets for the replication of rotaviruses and other RNA viruses. J Biol Todays World 2020, 9:001-003.

- Murphy S, Martin S, Parton RG: Lipid droplet-organelle interactions; sharing the fats. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2009, 1791:441-447.

- Martínez JL, Eichwald C, Schraner EM, López S, Arias CF: Lipid metabolism is involved in the association of rotavirus viroplasms with endoplasmic reticulum membranes. Virology 2022, 569:29-36. [CrossRef]

- Mattion NM, Cohen J, Aponte C, Estes MK: Characterization of an oligomerization domain and RNA-binding properties on rotavirus nonstructural protein NS34. Virology 1992, 190:68-83. [CrossRef]

- Hua J, Patton JT: The Carboxyl-Half of the Rotavirus Nonstructural Protein NS53 (NSP1) Is Not Required for Virus Replication. Virology 1994, 198:567-576. [CrossRef]

- Weclewicz K, Kristensson K, Svensson L: Rotavirus causes selective vimentin reorganization in monkey kidney CV-1 cells. Journal of General Virology 1994, 75:3267-3271. [CrossRef]

- Brunet J-P, Cotte-Laffitte J, Linxe C, Quero A-M, Géniteau-Legendre M, Servin A: Rotavirus infection induces an increase in intracellular calcium concentration in human intestinal epithelial cells: role in microvillar actin alteration. Journal of virology 2000, 74:2323-2332. [CrossRef]

- Jourdan N, Brunet Jean P, Sapin C, Blais A, Cotte-Laffitte J, Forestier F, Quero A-M, Trugnan G, Servin Alain L: Rotavirus Infection Reduces Sucrase-Isomaltase Expression in Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells by Perturbing Protein Targeting and Organization of Microvillar Cytoskeleton. Journal of Virology 1998, 72:7228-7236. [CrossRef]

- Weclewicz K, Svensson L, Billger M, Holmberg K, Wallin M, Kristensson K: Microtubule-associated protein 2 appears in axons of cultured dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord neurons after rotavirus infection. Journal of Neuroscience Research 1993, 36:173-182. [CrossRef]

- Campbell Elle A, Reddy Vishwanatha RAP, Gray Alice G, Wells J, Simpson J, Skinner Michael A, Hawes Philippa C, Broadbent Andrew J: Discrete Virus Factories Form in the Cytoplasm of Cells Coinfected with Two Replication-Competent Tagged Reporter Birnaviruses That Subsequently Coalesce over Time. Journal of Virology 2020, 94:10.1128/jvi.02107-02119.

- Parker John SL, Broering Teresa J, Kim J, Higgins Darren E, Nibert Max L: Reovirus Core Protein μ2 Determines the Filamentous Morphology of Viral Inclusion Bodies by Interacting with and Stabilizing Microtubules. Journal of Virology 2002, 76:4483-4496.

- Heath CM, Windsor M, Wileman T: Aggresomes Resemble Sites Specialized for Virus Assembly. Journal of Cell Biology 2001, 153:449-456. [CrossRef]

- Lahaye X, Vidy A, Pomier C, Obiang L, Harper F, Gaudin Y, Blondel D: Functional Characterization of Negri Bodies (NBs) in Rabies Virus-Infected Cells: Evidence that NBs Are Sites of Viral Transcription and Replication. Journal of Virology 2009, 83:7948-7958. [CrossRef]

- Criglar Jeanette M, Hu L, Crawford Sue E, Hyser Joseph M, Broughman James R, Prasad BVV, Estes Mary K: A Novel Form of Rotavirus NSP2 and Phosphorylation-Dependent NSP2-NSP5 Interactions Are Associated with Viroplasm Assembly. Journal of Virology 2014, 88:786-798.

- Martin D, Duarte M, Lepault J, Poncet D: Sequestration of free tubulin molecules by the viral protein NSP2 induces microtubule depolymerization during rotavirus infection. J Virol 2010, 84:2522-2532. [CrossRef]

- Dhillon P, Tandra Varsha N, Chorghade Sandip G, Namsa Nima D, Sahoo L, Rao CD: Cytoplasmic Relocalization and Colocalization with Viroplasms of Host Cell Proteins, and Their Role in Rotavirus Infection. Journal of Virology 2018, 92:10.1128/jvi.00612-00618.

- Zambrano JL, Sorondo O, Alcala A, Vizzi E, Diaz Y, Ruiz MC, Michelangeli F, Liprandi F, Ludert JE: Rotavirus infection of cells in culture induces activation of RhoA and changes in the actin and tubulin cytoskeleton. PLoS One 2012, 7:e47612. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Zeng Carl QY, Morris Andrew P, Estes Mary K: A Functional NSP4 Enterotoxin Peptide Secreted from Rotavirus-Infected Cells. Journal of Virology 2000, 74:11663-11670.

- Xu A, Bellamy AR, Taylor JA: Immobilization of the early secretory pathway by a virus glycoprotein that binds to microtubules. The EMBO Journal 2000, 19:6465-6474. [CrossRef]

- Jing Z, Shi H, Chen J, Shi D, Liu J, Guo L, Tian J, Wu Y, Dong H, Ji Z, et al: Rotavirus Viroplasm Biogenesis Involves Microtubule-Based Dynein Transport Mediated by an Interaction between NSP2 and Dynein Intermediate Chain. J Virol 2021, 95:e0124621. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Su Justin M, Samuel Charles E, Ma D: Measles Virus Forms Inclusion Bodies with Properties of Liquid Organelles. Journal of Virology 2019, 93:10.1128/jvi.00948-00919.

- Glück S, Buttafuoco A, Meier AF, Arnoldi F, Vogt B, Schraner EM, Ackermann M, Eichwald C: Rotavirus replication is correlated with S/G2 interphase arrest of the host cell cycle. PLoS One 2017, 12:e0179607. [CrossRef]

- Akhmanova A, Steinmetz MO: Control of microtubule organization and dynamics: two ends in the limelight. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2015, 16:711-726.

- Condemine W, Eguether T, Couroussé N, Etchebest C, Gardet A, Trugnan G, Chwetzoff S: The C Terminus of Rotavirus VP4 Protein Contains an Actin Binding Domain Which Requires Cooperation with the Coiled-Coil Domain for Actin Remodeling. Journal of Virology 2018, 93. [CrossRef]

- Berkova Z, Crawford SE, Blutt SE, Morris AP, Estes MK: Expression of rotavirus NSP4 alters the actin network organization through the actin remodeling protein cofilin. Journal of virology 2007, 81:3545-3553. [CrossRef]

- Gardet A, Breton M, Fontanges P, Trugnan G, Chwetzoff S: Rotavirus spike protein VP4 binds to and remodels actin bundles of the epithelial brush border into actin bodies. J Virol 2006, 80:3947-3956. [CrossRef]

- Vetter J, Papa G, Seyffert M, Gunasekera K, De Lorenzo G, Wiesendanger M, Reymond JL, Fraefel C, Burrone OR, Eichwald C: Rotavirus Spike Protein VP4 Mediates Viroplasm Assembly by Association to Actin Filaments. J Virol 2022:e0107422. [CrossRef]

- Nikolic J, Le Bars R, Lama Z, Scrima N, Lagaudrière-Gesbert C, Gaudin Y, Blondel D: Negri bodies are viral factories with properties of liquid organelles. Nature Communications 2017, 8:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Nejmeddine M, Trugnan G, Sapin C, Kohli E, Svensson L, Lopez S, Cohen J: Rotavirus spike protein VP4 is present at the plasma membrane and is associated with microtubules in infected cells. J Virol 2000, 74:3313-3320. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Gao W, Li J, Wu W, Jiu Y: The Role of Host Cytoskeleton in Flavivirus Infection. Virologica Sinica 2019, 34:30-41. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L-J, Xia L, Liu S-L, Sun E-Z, Wu Q-M, Wen L, Zhang Z-L, Pang D-W: A “Driver Switchover” Mechanism of Influenza Virus Transport from Microfilaments to Microtubules. ACS Nano 2018, 12:474-484. [CrossRef]

- Brunet J-P, Jourdan N, Cotte-Laffitte J, Linxe C, Géniteau-Legendre M, Servin A, Quéro A-M: Rotavirus Infection Induces Cytoskeleton Disorganization in Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells: Implication of an Increase in Intracellular Calcium Concentration. Journal of Virology 2000, 74:10801-10806. [CrossRef]

- Broering TJ, Parker JSL, Joyce PL, Kim J, Nibert ML: Mammalian Reovirus Nonstructural Protein μNS Forms Large Inclusions and Colocalizes with Reovirus Microtubule-Associated Protein μ2 in Transfected Cells. Journal of Virology 2002, 76:8285-8297. [CrossRef]

- Bussiere LD, Choudhury P, Bellaire B, Miller CL: Characterization of a Replicating Mammalian Orthoreovirus with Tetracysteine-Tagged μNS for Live-Cell Visualization of Viral Factories. J Virol 2017, 91. [CrossRef]

- Dales S: Association Between The Spindle Apparatus and Reovirus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1963, 50:268-275.

- Sharpe AH, Chen LB, Fields BN: The interaction of mammalian reoviruses with the cytoskeleton of monkey kidney CV-1 cells. Virology 1982, 120:399-411. [CrossRef]

- Eaton BT, Hyatt AD: Association of Bluetongue Virus with the Cytoskeleton. Volume 151989: 233-273.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).