1. Introduction

Vaccines have been and remain one of the most profound advancements in medical science. They are potent tools that bolster immune defenses, protecting individuals from debilitating diseases and often saving lives. The significance of vaccines extends beyond personal well-being, contributing to collective (herd) immunity within communities. By achieving high vaccination rates, we create a shield that guards vulnerable populations and reduces the spread of infectious diseases. Thus, the importance of vaccines cannot be overstated. They represent a cornerstone of public health efforts and a testament to our capacity to prevent and control potentially devastating illnesses.

The recent SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has raised concerns regarding vaccine participation and immunity. Similar to discussions surrounding mask usage, SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have been discussed in the context of the safety and convenience of the individual rather than the importance of herd immunity and protecting immunosuppressed individuals [

1]. These discussions are consistent with the observed rise in vaccine hesitancy and non-medical vaccine exemption trends in the U.S. [

2]. This increase in vaccine hesitancy is concerning, as shown by an analysis of the 2018 measles epidemic in New York, which demonstrated that a vaccination rate of 79.5% was insufficient to guarantee herd immunity [

1].

Understanding the factors that motivate or disincentivize individuals from getting immunized is crucial to maintain public health [

3]. For example, some individuals may lack awareness about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, or they may not fully comprehend the importance of population-wide participation in order to protect the entire community. Others may feel pressured to question scientific and medical consensus regarding vaccinations [

4]. By recognizing and addressing these factors, efforts can be made to encourage individuals and communities to get vaccinated.

Several studies have attempted to shed light on factors that may contribute to vaccine resistance and hesitancy [

5]. Researchers have developed survey instruments to examine potential correlations between vaccine hesitancy and political affiliations [

6] and parents’ beliefs about immunizations [

7]. Examination of responses from focus groups has revealed that some parents object to vaccines due to fewer cases of vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) in the U.S. Some parents feel that vaccine-induced immunity is unnatural and express a lack of trust in expert opinions [

7].

Other factors include philosophical beliefs, religious beliefs, and safety concerns [

8]. As the prevalence of VPDs has decreased, the number of groups opposing vaccines on religious and philosophical grounds has increased, and this opposition is fundamental, unrelated to safety concerns. Historical examples, such as establishment of the Anti-Vaccination League in London in 1853, illustrate widespread objections to vaccination laws [

9]. Religious objections to vaccines, as described by Lynnfield and Daum (2014), are often related to the origins of vaccines [

8]. For example, Catholics may be concerned about vaccines derived from cell lines of aborted fetuses, while Jewish and Muslim individuals may be concerned about the porcine constituents in certain vaccines. Representatives from these religious denominations have typically advocated for vaccines, explaining that that those seeking to be immunized are not responsible for the abortions and that the porcine components undergo sufficient alteration during vaccine development. However, individual members within these denominations may still feel differently and choose not to vaccinate [

8].

Surveys have proven to be valuable tools for examining the relationship between health literacy and utilization of medical services [

10], as well as for investigating the factors associated with vaccine resistance and hesitancy. For example, Wang

et al. (2018) conducted a survey to explore parents’ opinions on vaccines following a scandal and their “vaccine literacy,” or their knowledge of vaccines [

11,

12]. Wang

et al. (2018) found that parents with better vaccine literacy were more likely to trust vaccines [

11]. Furthermore, these findings present an interesting question: if vaccine literacy is negatively correlated with vaccine hesitancy, increasing the public’s understanding of vaccines could increase vaccine participation and help eliminate harmful diseases [

13].

Recent studies on potential correlations between vaccine literacy and hesitancy have produced conflicting results. One study conducted in urban and rural communities in India found a positive association between maternal health literacy and childhood vaccination with diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP3) [

14]. In contrast, a different study conducted in Israel found a negative association between parental critical and communicative health literacy and compliance with vaccinations [

13]. More research is needed to truly uncover whether these results are due to differences in other demographic factors or simply due to a lack of correlation between vaccine hesitancy and literacy.

This study aimed to examine the correlation between vaccine literacy and hesitancy in parents and legal guardians of elementary school-aged children. Due to the conflicting results described previously, we had no prediction whether a correlation would exist. We did, however, predict that those parents who filed for vaccine exemptions, and were thus vaccine hesitant or resistant, would be the minority. Our prediction was based on a survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that estimated only 2.2% of kindergartners in Indiana were unvaccinated during the 2019-2020 school year [

15].

2. Materials and Methods

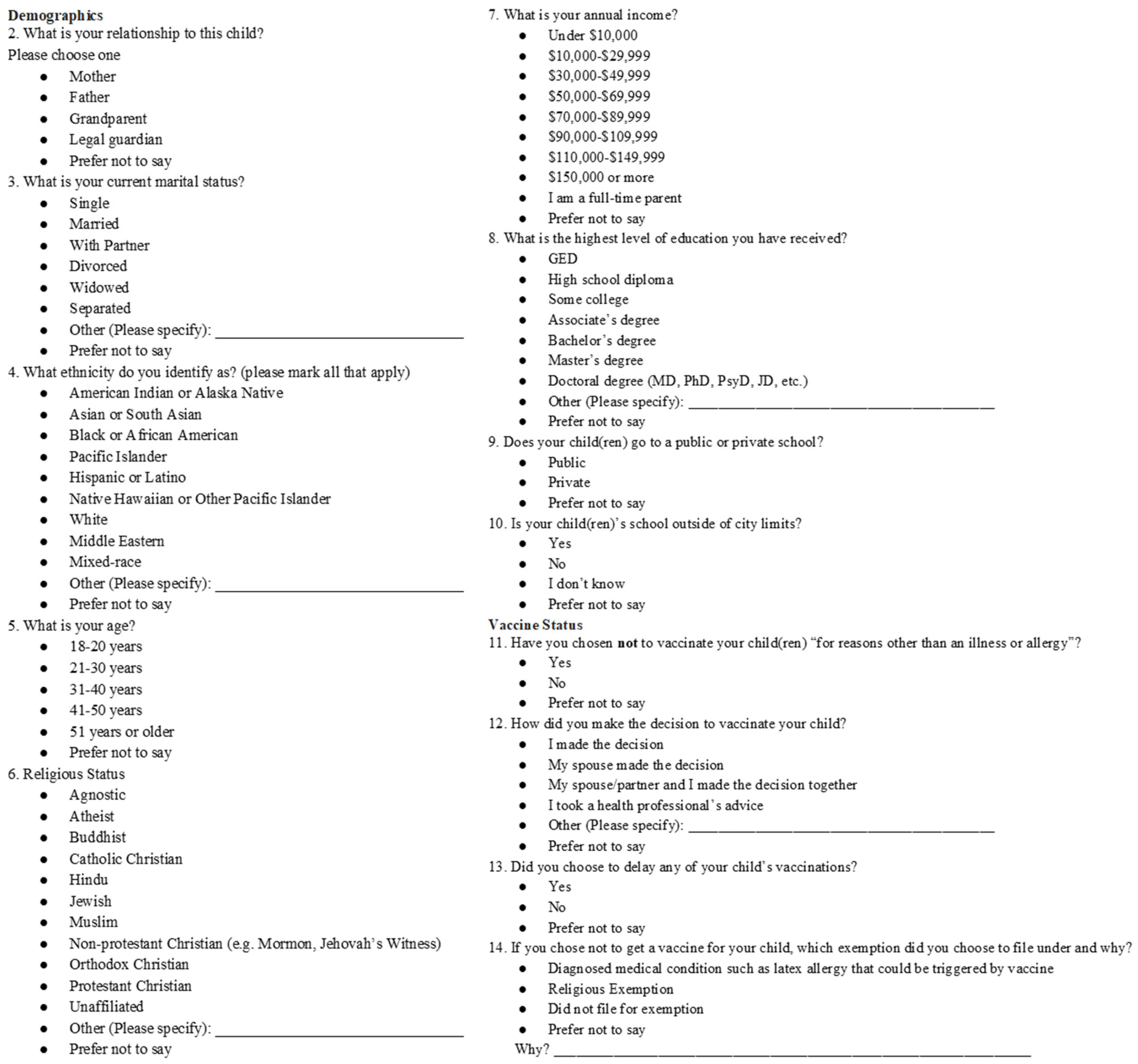

A 25-question, anonymous survey was utilized to collect data from participating parents or legal guardians of elementary-age students between September 23, 2021, to January 9, 2022. The survey questionnaire (

Figure A1, see Appendix section) included questions regarding demographics (adapted from Evans, 2015) [

16], child vaccination status, and parental understanding of vaccines. The survey was made available in English and Spanish for the bilingual population.

The survey was disseminated both electronically and in-person. Flyers were sent by principals and directors to parents and legal guardians at a public elementary school, private school, Early Childhood Development Center, and bilingual community center in South Bend, as well as two additional private schools in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Flyers were also posted on the parent Facebook pages for a private and a public school in South Bend, Indiana. Additionally, the survey was advertised by the Saint Mary’s College Vaccine Ambassadors team while tabling on campus and at COVID-19 and influenza vaccine clinics at a local church in South Bend, Indiana.

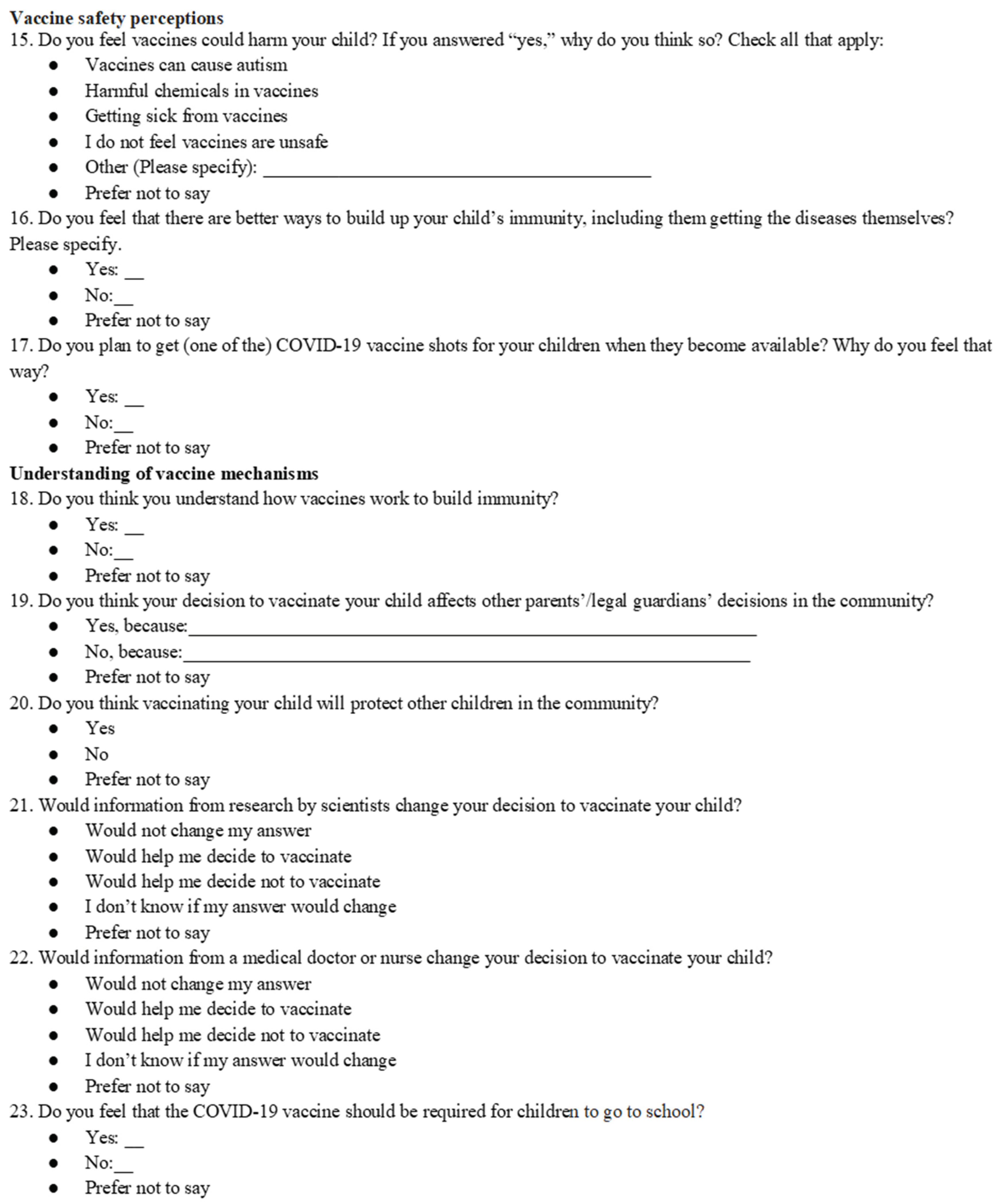

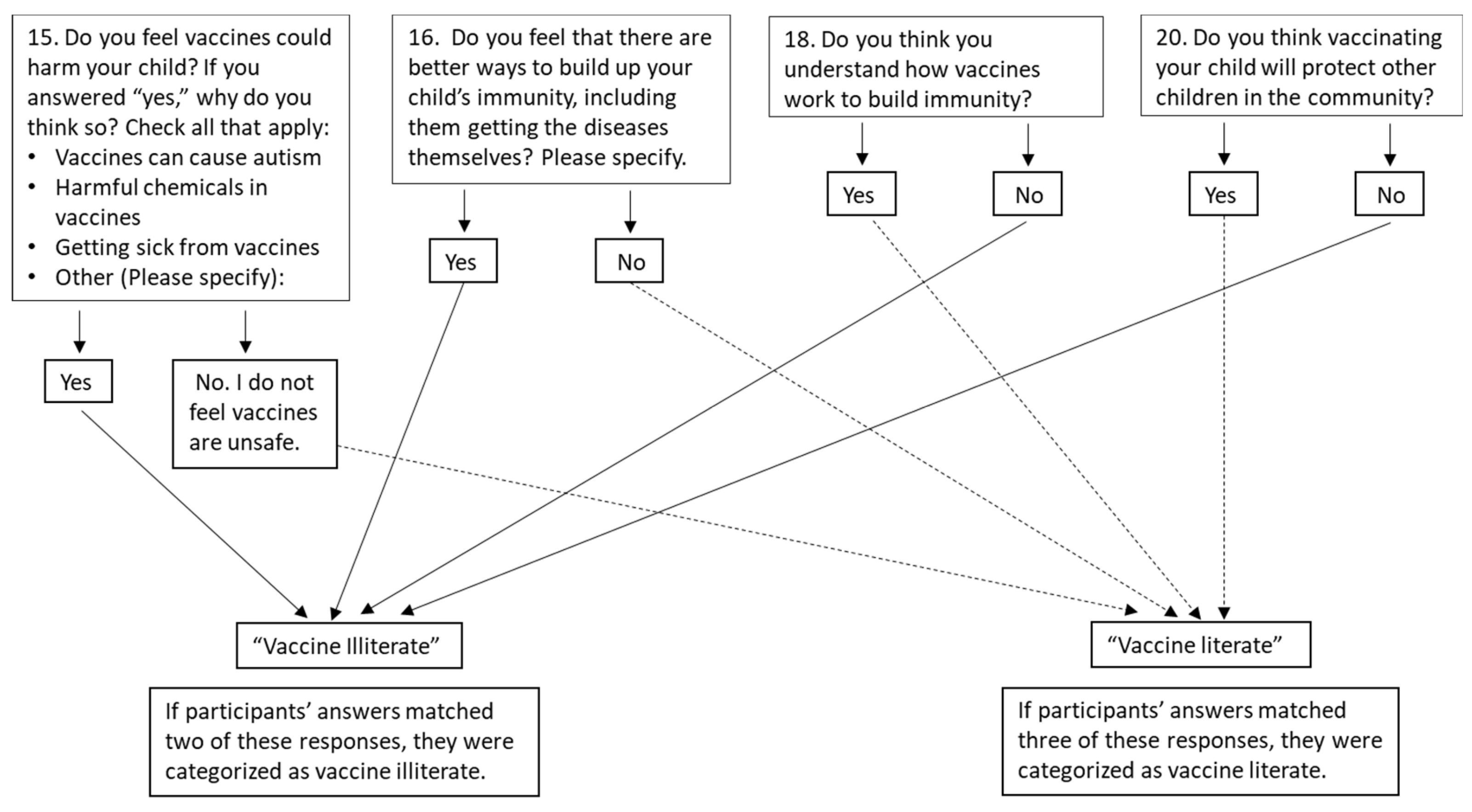

For data analysis, participants were sorted into one of four groups according to their responses to the vaccine hesitancy and literacy questions (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). For example, the participant could be vaccine literate and unhesitant, vaccine literate and hesitant, vaccine illiterate and unhesitant, and vaccine illiterate and hesitant. Participants who answered at least three literacy questions correctly were considered “literate” and participants who answered at least two literacy questions incorrectly were considered “illiterate.” Participants who left literacy questions blank or answered “prefer not to say,” and therefore did not answer either at least three questions correctly or at least two questions incorrectly, were considered neither vaccine literate nor illiterate and were not included in the statistical analysis. 17 participants who answered “yes” to Question 11 (“Have you chosen not to vaccinate your child(ren) ‘for reasons other than an illness or allergy?’” [

7], and were therefore resistant, were excluded from the hesitancy tests to prevent these participants from being included in the “unhesitant” group. Potential correlations were analyzed with Chi-squared tests utilizing the “R” software [

17].

The first Chi-Squared analysis examined hesitancy towards all vaccines and vaccine literacy. Hesitancy was assessed through Question 13 [“Did you choose to delay any of your child’s vaccinations?” [

7], and vaccine literacy was assessed using Questions 15 (Do you feel vaccines could harm your child? If you answered “yes,” why do you think so?”), 16 [“Do you feel that there are better ways to build up your child’s immunity, including them getting the diseases themselves? Please specify.” [

7], 18 (“Do you think you understand how vaccines work to build immunity?”), and 20 (“Do you think vaccinating your child will protect other children in the community?”).

The second Chi-squared analysis examined COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and vaccine literacy. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was assessed through Questions 17 (“Do you plan to get (one of the) COVID-19 vaccine shots for your children when they become available? Why do you feel that way?”) and 23 (“Do you feel that the COVID-19 vaccine should be required for children to go to school?”), and vaccine literacy was assessed through Questions 15, 16, 18, and 20. Participants were asked if they planned to get their children vaccinated for COVID-19 when vaccines became available because children in this age group were not yet eligible for the vaccine when data collection began.

The third Chi-squared analysis examined resistance towards all vaccines and vaccine literacy. Resistance was assessed through Question 11 [“Have you chosen not to vaccinate your child(ren) ‘for reasons other than an illness or allergy?’” [

7], and vaccine literacy was assessed through Questions 15, 16, 18, and 20.

Additional Chi-squared analyses were conducted to examine correlations between hesitancy towards all vaccines and vaccine literacy in terms of participants’ income and education levels. Participants were placed into income and education brackets based on their answers to Questions 7 (“What is your annual income?”) and 8 (“What is the highest level of education you have received?”), respectively.

3. Results

A total of 115 responses were collected. Of the 115 participants who responded, 107 answered “I agree to participate” to Question 1 and were included in the statistical analysis. Some responses were not included in the Chi-Squared tests because participants were neither vaccine literate nor vaccine illiterate. Demographics of the sampled population are shown in

Table 1. 89 of the 107 responses were completed by mothers. If participants identified with more than one race, they were only categorized as “mixed race” to avoid counting participants more than once (

Table 1).

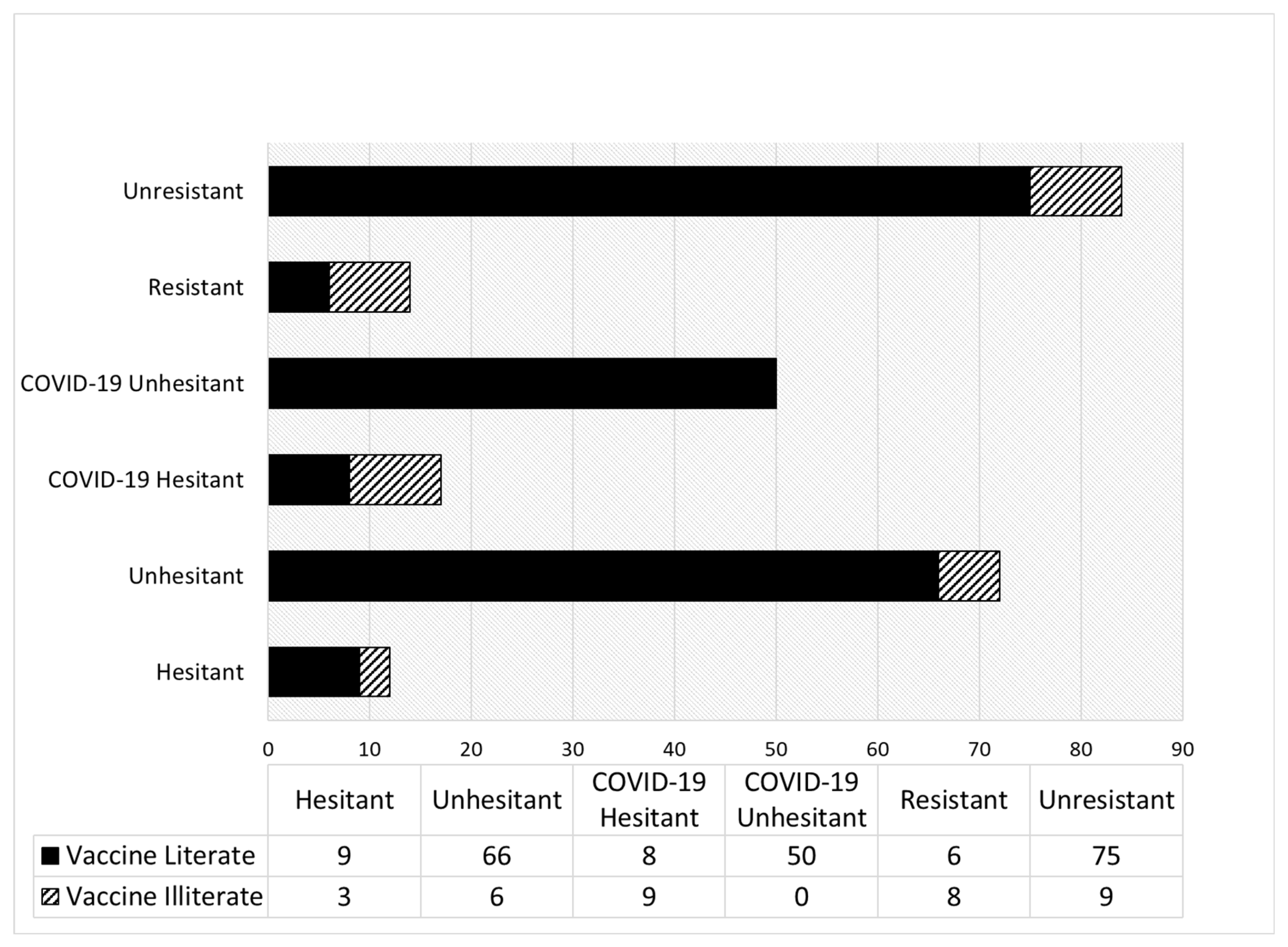

88 participants were unresistant and answered either “yes” or “no” to Question 13 [“Did you choose to delay any of your child’s vaccinations?” [

7] and were therefore “hesitant” or “unhesitant” towards all vaccines. 84 of these individuals also answered either at least three of the vaccine literacy questions correctly or answered at least two of the vaccine literacy questions incorrectly and were included in the first Chi-squared test. The remaining four were neither vaccine literate nor vaccine illiterate. Of the 84 people who answered the vaccine literacy and vaccine hesitancy questions, 66 were literate and unhesitant, nine were literate and hesitant, six were illiterate and unhesitant, and three were illiterate and hesitant (

Figure 3). Although the majority of literate individuals were not hesitant, no significant negative correlation between vaccine literacy and vaccine hesitancy was found (

P>0.05).

67 participants were unresistant and answered either “yes” for both Questions 17 (“Do you plan to get (one of the) COVID-19 vaccine shots for your children when they become available?”) and 23 (“Do you feel that the COVID-19 vaccine should be required for children to go to school?”) or “no” for both Questions 17 and 23 and were included in the second Chi-squared test which examined a correlation between vaccine literacy and vaccine hesitancy towards the COVID-19 vaccine. Of these, 50 were literate and unhesitant, eight were literate and hesitant, zero were illiterate and unhesitant, and nine were illiterate and hesitant (

Figure 3). A significant negative correlation between vaccine literacy and vaccine hesitancy towards the COVID-19 vaccine was found (P=0.0000003086). 11 people said “yes” to Question 17 and “no” to Question 23, indicating they intended to immunize their child for COVID-19 but did not think the COVID-19 vaccine should be required for school. None of the participants said “no” to Question 17 and “yes” to Question 23 (

Figure 3).

The third Chi-squared test examined vaccine resistance and vaccine literacy. 98 participants were either vaccine literate or illiterate and answered either “yes” or “no” to Question 11 [“Have you chosen

not to vaccinate your child(ren) ‘for reasons other than an illness or allergy?’” [

7]. 75 participants were unresistant and vaccine literate, six were resistant and vaccine literate, nine were unresistant and vaccine illiterate, and eight were resistant and vaccine illiterate (

Figure 3). A significant negative correlation was found between vaccine literacy and vaccine resistance (P=0.001105).

Of the unresistant participants who were either vaccine literate or vaccine illiterate, more participants were hesitant towards the COVID-19 vaccine than were hesitant towards vaccines in general. 12 participants answered “yes” to Question 13 [“Did you choose to delay any of your child’s vaccinations?” [

7] demonstrating their hesitancy towards vaccines in general. 17 people answered “no” to both Questions 17 (“Do you plan to get (one of the) COVID-19 vaccine shots for your children when they become available?”) and 23 (“Do you feel that the COVID-19 vaccine should be required for children to go to school?”), demonstrating their hesitancy towards the COVID-19 vaccine (

Figure 3). 15 of these COVID-19 hesitant participants were not hesitant towards vaccines in general. This was demonstrated by a participant who answered “no” to Question 13, but said they were “only nervous about the COVID-19 vaccine” and did not plan on getting this vaccine for their child.

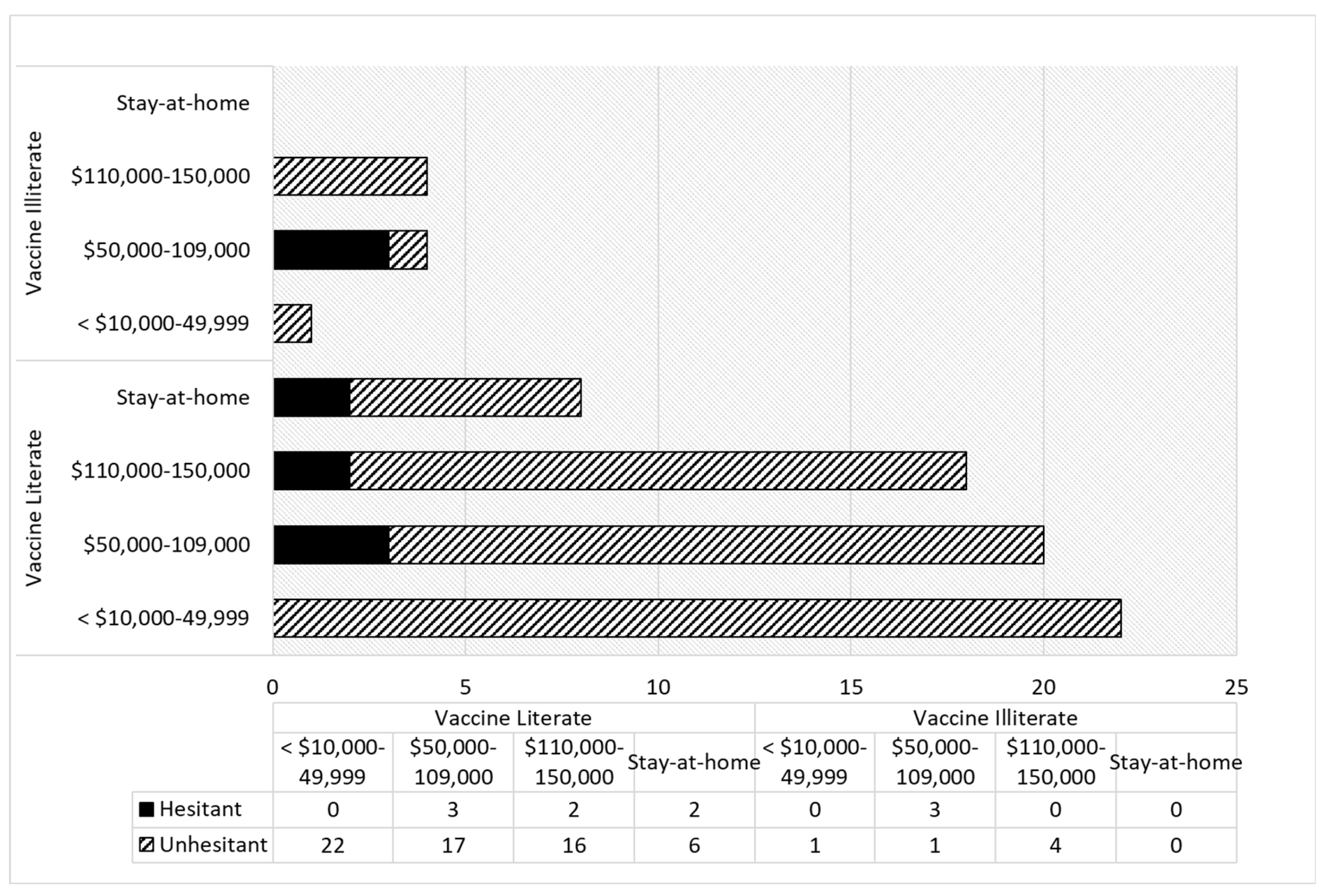

Vaccine hesitancy and vaccine literacy were compared at different income and education levels to determine if different correlations existed between the two variables at different levels. 77 participants who were unresistant and answered Question 7 (What is your annual income?) were sorted into four income subgroups: less than

$10,000-49,9999 (23 participants),

$50,000-109,000 (24 participants),

$110,000-150,000 or more (22 participants), and stay-at-home parents (8 participants) (

Figure 4). Chi-squared tests revealed no significant correlations for any of the groups (

P>0.05). It was not possible to calculate a p-value for the less than

$10,000-49,9999 group because there were no hesitant individuals in this category. Additionally, it was not possible to calculate a p-value for the stay-at-home parents because there were no vaccine illiterate participants in this category (

Figure 4).

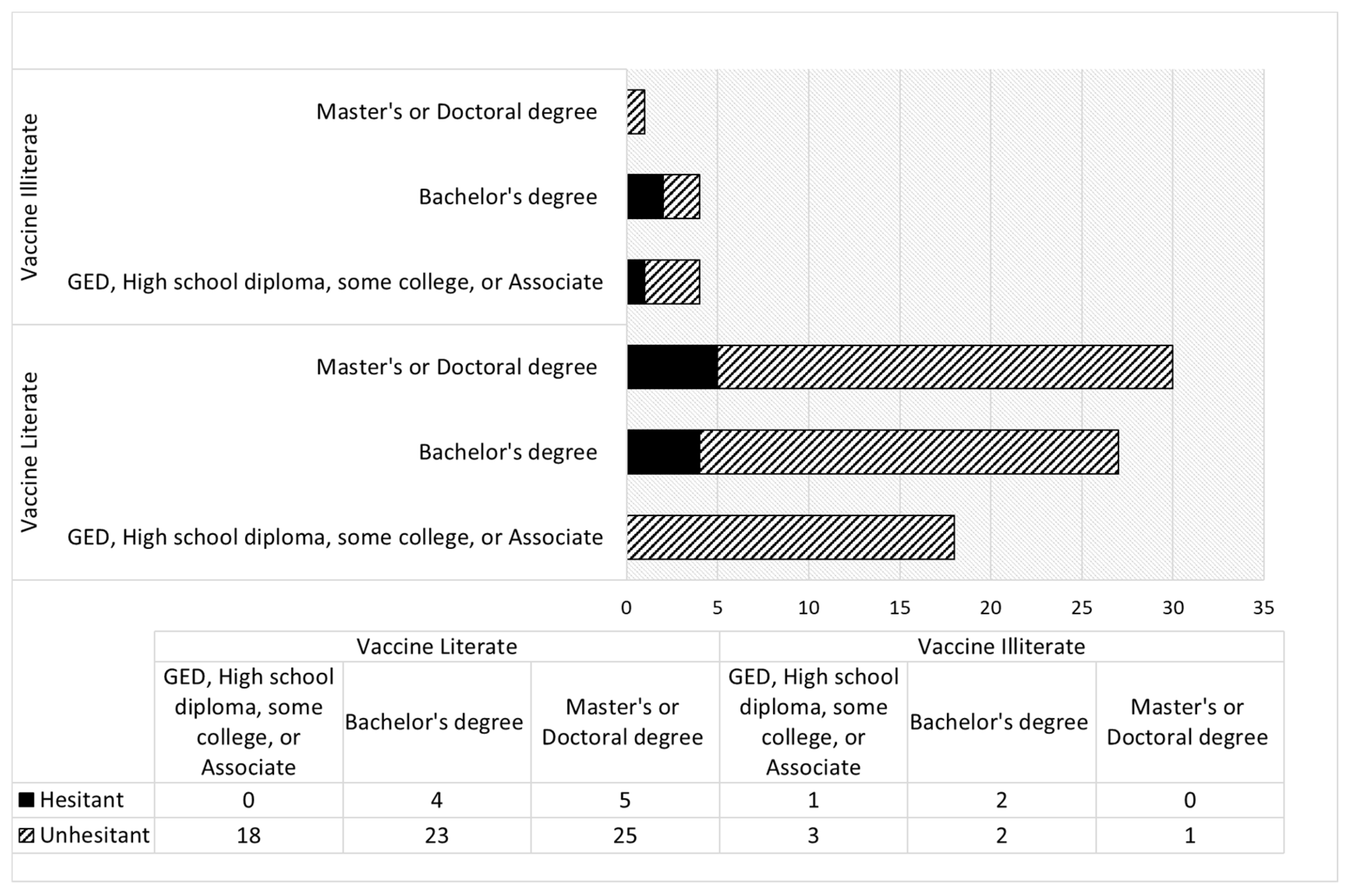

84 participants who were unresistant and answered Question 8 (What is the highest level of education you have received) were sorted into three educational subgroups: GED, high school diploma, some college, or an associate degree (22 participants); bachelor's degree (31 participants); and master's or a doctoral degree (31 participants) (

Figure 5). Chi-squared tests revealed no significant correlations for these groups (

P>0.05).

4. Discussion

Researchers have speculated that high health literacy correlates with low vaccine hesitancy. However, a low level of communicative health literacy has been found to increase the likelihood of childhood vaccination [

13]. It should be noted that “health literacy” refers to basic health knowledge relating to a variety of health decisions whereas “vaccine literacy” specifically refers to knowledge about vaccines and information that combats anti-vaccine sentiments [

12]. Individuals with high health literacy that understand the basic principles of health and wellness may not necessarily understand the importance of vaccines or vaccine mechanisms. Therefore, it is important to investigate a possible correlation between participants’ vaccine literacy and hesitancy [

18]. The independent variable, parental vaccine literacy, was determined through survey questions assessing participants’ understanding and concerns about vaccines. The dependent variable, parental vaccine hesitancy, was measured by the number of participants that delayed vaccinations for their children. Once the survey closed, statistical analysis was performed to exam any significant correlations between vaccine hesitancy and literacy.

The survey was completed by a significantly higher number of mothers compared to fathers, legal guardians, and grandparent combined (83.2% compared to 15.9%, respectively). This is supported by previous findings by Opel

et al. (2010) [

7]. Furthermore, participants predominantly identified as white compared to any other ethnicity. Both aspects could have influenced the results of this study.

When completing the survey, participants answered questions about vaccine literacy and their child’s vaccine status that indicated whether they were vaccine unhesitant, hesitant, or resistant. In this study, vaccine hesitancy is defined as the delay of vaccination to a later time, and vaccine rejection or resistance is defined as the refusal of vaccination, assuming the refusal is not medically related [

19]. These definitions refer to parents who are hesitant or resistant toward vaccines in general.

It is widely accepted that vaccine hesitancy rates can differ depending on the vaccine [

20]. Therefore, determining if vaccine literacy is correlated with higher vaccination rates is especially relevant during a pandemic. Questions 17 (“Do you plan to get (one of the) COVID-19 vaccine shots for your children when they become available?”) and 23 (“Do you feel that the COVID-19 vaccine should be required for children to go to school?”) determined whether participants were hesitant toward the COVID-19 vaccine. Overall, there was a higher level of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. 15 participants were “COVID-19 vaccine hesitant” but were not hesitant or resistant toward vaccines in general. One participant underlined this difference by stating, “for COVID-19 there are better ways to build up immunity.”

Questions 15, 16, 18, and 20 evaluated the participants’ vaccine literacy. For Question 15 (“Do you feel vaccines could harm your child?”), “I do not feel vaccines are unsafe” indicated vaccine literacy, with the understanding that the child had no allergies or medical conditions where temporary post-vaccine symptoms would be dangerous [e.g., fever-induced seizures [

21]. For Question 16, (“Do you feel that there are better ways to build up your child’s immunity, including them getting the diseases themselves?”), “no” indicated vaccine literacy [

13] because it is generally accepted that vaccines induce high immunoglobulin levels and T-cell responses, particularly in children, without patients having to expend energy or resources to fight viruses themselves. Moreover, studies have shown that vaccinated children may have a reduced risk of other unconnected infections [

22]. Therefore, vaccines are generally a safer and medically recommended option.

For both Questions 18 (“Do you think you understand how vaccines work to build immunity?”) and 20 (“Do you think vaccinating your child will protect other children in the community?”), “yes” indicated vaccine literacy. However, Question 18 was subjective, and it is plausible that some participants mistook their understanding of vaccines. Participants were identified as vaccine literate if they answered at least three of the four literacy questions correctly and “illiterate” if they answered at least two of the three questions incorrectly.

The significant negative correlations between vaccine literacy and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and vaccine literacy and resistance towards all vaccines indicate that vaccine literate participants were significantly less likely to be hesitant towards the COVID-19 vaccine or resistant toward all vaccines. However, the null hypothesis, that no significant negative correlation exists between vaccine literacy and vaccine hesitancy towards all vaccines, was supported.

The significant correlation between vaccine literacy and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is consistent with the findings of Johri

et al. (2015) and Wang

et al. (2018), but differs from the findings of Aharon

et al. (2016) [

11,

13,

14]. There are various possible explanations for this, one being that Aharon

et al. did not explicitly ask participants about vaccines. Using the Vaccine Health Literacy Scale adapted from Ishikawa

et al. (2008)

, Aharon

et al. asked participants whether they searched for and understood information on vaccines but did not ask questions that evaluated this understanding [

13,

23]. They did not, for example, ask participants if they were worried about vaccines causing autism [

13].

It would therefore be possible for participants to find inaccurate sources on vaccines and score well on this test without being vaccine literate. Participants would be more likely to undertake research autonomously if they felt the need to make decisions based either on their own intuition or to question the scientific consensus without advice from their healthcare provider [

4]. Additionally, vaccine hesitant or vaccine resistant parents who communicate with their child’s healthcare provider are more likely to change their minds and vaccinate their children [

24]. These findings suggest that if parents’ decision-making regarding childhood vaccination does not include their child’s healthcare provider, they are more likely to be vaccine hesitant as well as vaccine illiterate [

24].

While surveys are a relatively easy means of gathering and quantifying data from large populations, biases can still exist [

25]. Results may be skewed by coverage errors, sampling errors, nonresponse errors, or measurement errors [

26]. Coverage errors occur when the sample group is not diverse enough to represent the population. Sampling errors occur when not all members of the sample group are surveyed. Nonresponse errors occur when not all members of the sample group respond. Measurement errors occur when participants feel they cannot answer honestly or completely [

26]. These potential biases were considered when completing this survey to investigate vaccine hesitancy and how perceptions are affected by vaccine literacy [

19].

In future surveys, the questions can be revised to minimize the potential for miscommunications. For example, the phrase “but eventually got them vaccinated” could be added to the end of Question 13 (Did you choose to delay any of your child’s vaccination) to more clearly separate vaccine hesitant and not resistant participants. The metrics used to determine vaccine literacy can be edited to prevent participants from answering one question correctly and being considered literate. It would be wise to revise the subjective Question 18 (Do you think you understand how vaccines work to build immunity) and instead require correct answers for Questions 15, 16, and 20. It would be interesting to examine any significant negative correlations between vaccine literacy and hesitancy toward all vaccines, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and resistance toward vaccines with a more diverse sample size.

The results of this study indicate that education and teaching about the importance of vaccines for individual, community, and population health may lessen vaccine hesitancy among parents and may be an important factor in improving vaccination rates among the pediatric population.