Submitted:

27 March 2024

Posted:

27 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A simple, objective, noninvasive method that captures early lesions and the diverse states of endometriosis, including their localization and spread.

- A scoring system to stratify severe cases and guide referrals to specialized facilities.

- An anatomically intuitive and easily shareable format akin to the TNM classification facilitates information exchange between physicians and patients.

- A method capable of capturing temporal changes, useful as an indicator for surgical, medicinal, recurrent, and infertility interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects

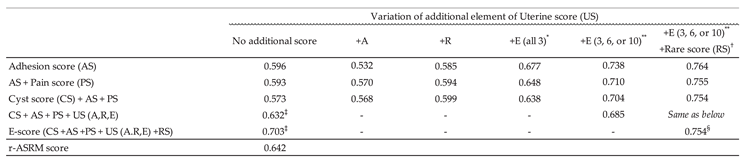

2.2. NMS-E Method Overview

- I.

- Physical finding Map: This foundational layer captures a wide array of endometriosis-related data collected during examinations. It is the basis for the subsequent layers, organizing the extensive information into a visual and anatomical format.

- II.

- NMS-E Summary: Building on the Physical finding Map, this layer condenses the detailed observations into a concise equation, facilitating a standardized summary of the endometriosis condition akin to the TNM classification used in oncology.

- III.

- E-Score: The culmination of the NMS-E method, this layer translates the summarized data into a singular numeric value, representing the severity of endometriosis. The E-Score integrates four critical elements derived from the previous layers: cyst, adhesion, pain, and uterine scores.

2.2.1. Detailed Layer Descriptions

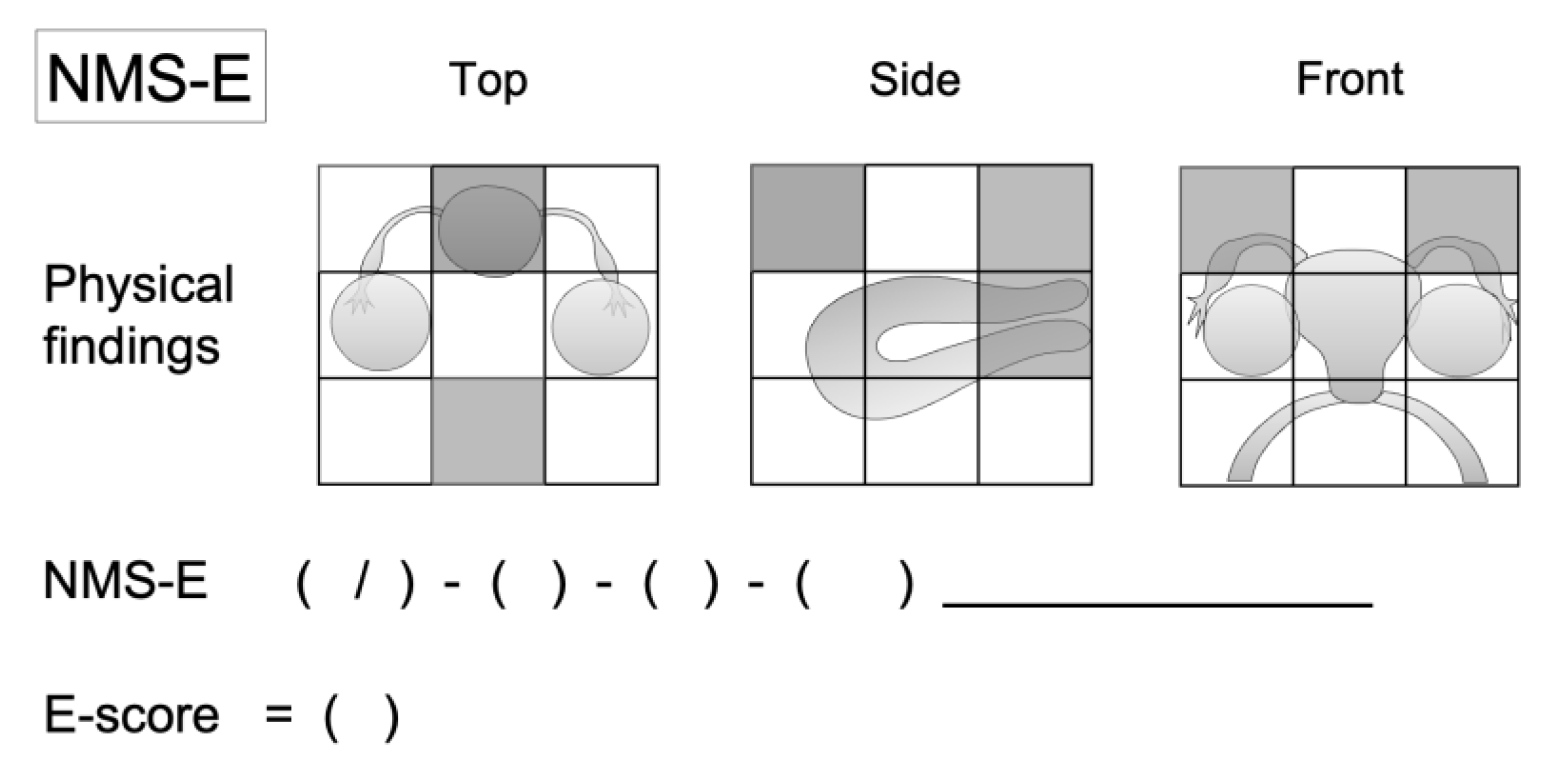

2.2.2. The Measurement and Recording Methods for the Four Conditions of Endometriosis

- I.

- Endometrioma: endometrioma is measured using the maximum diameter in transvaginal ultrasonography (to one decimal place, in cm). The findings are recorded in the central row's left cell of the left 3x3 grid (corresponding to the right adnexal region of the patient) or the right cell (corresponding to the left adnexal region). For multi-cystic conditions, the total maximum diameter is used. For non-endometriomas, the cyst type's initial is prefixed before the size [Appendix A - NMS-E Example 3]. If tubal lesions are identified, their abbreviations (e.g., hydrosalpinx: h.s) are also recorded [Appendix A - NMS-E Example 4]. For summarization, the rounded-up value of the cyst's maximum diameter is recorded as the cyst score for each side. Figure 2 shows a right endometrioma of 6.5cm and a left endometrioma of 2.4cm. For summarization, values are rounded up, resulting in 7/3. The maximum score for a single endometrioma is 5. Thus, the cyst score for this case is right 5 + left 3 = 8 points.

- II.

- Adhesion: Adhesion is measured at ten locations using transvaginal ultrasonography cross-sectional (five locations) and longitudinal (five locations) images of the uterus ovaries. Adhesions are assessed based on the presence or absence of the sliding sign at each location. The sliding sign is a method to diagnose adhesions by checking if there is movement between the target organ and surrounding tissue when pressed with the ultrasound probe [23]. The presence of movement indicates no adhesions (-), while the absence indicates adhesions (+). For more details on the measurement method, refer to the adhesion score paper [21]. Measurement locations include the space between the right ovary and right pelvic wall (Rt. O-side), between the right ovary and uterus (Rt. O-Ut.), between both ovaries (Inter O-O), between the left ovary and uterus (Lt. O-Ut.), between the left ovary and left pelvic wall (Lt. O-Side), and the upper (Upper ant.), middle (Mid. ant.) parts of the anterior surfaces of the uterus, and the upper (Upper post.), middle (Mid.post.), and lower (Lower post.) parts of the posterior surfaces of the uterus. Figure 2 shows adhesions at four locations in the cross-sectional view and three in the longitudinal view, resulting in an adhesion score of 7/10. This value is directly added to the E-score.

- III.

- Pain: Pain is evaluated using NRS out of 10 based on pain induced by palpation during pelvic examination in seven pelvic regions centered around the uterine cervix: I. Right adnexal region, II. Right uterosacral ligament area, III. Anterior vaginal wall area, IV. Cervical area, V. Pouch of Douglas, VI. Left adnexal region, VII. Left uterosacral ligament area. The values are recorded in the corresponding cells of the right 3x3 grid. The details of this mapping, including pain intensity in each region, are referenced in the Pain Score paper [22]. The highest point among the seven areas is the Max Pain score. In Figure 2, the highest point is 8 in the Douglas pouch area, making the patient's Pain score 8. This value is directly added to the E-score.

- IV.

- Uterine Lesion: Uterine lesion is mainly evaluated using transvaginal ultrasonography. The assessed conditions include Retroverted uterus (R), Endometriotic nodules (E), and Adenomyosis (A). Uterine fibroids (M) are evaluated but not scored. All detected conditions, such as R, A, E, and M lesions and their sizes (if applicable), are recorded in the central cell of the middle row of the central grid or the anatomically corresponding cell along with their size. Endometriotic nodules (E) are depicted as hypoechogenic lesions similar to adenomyosis outside the uterus (lesions larger than 1cm in diameter are defined as E in this assessment) [7]. E lesions detected as nodules during pelvic examination are also marked in the corresponding cell on the right grid. The definition of a retroverted uterus (R) is when the angle formed by the cervical and uterine body axes is less than 180 degrees posteriorly [24]. Adenomyosis (A) appears on transvaginal ultrasound as a heterogeneously enlarged uterus with myometrial cysts, asymmetric myometrial thickening, poorly defined areas of echogenicity, etc. [7]. Figure 2 displays a 2.4 cm endometriotic nodule located at the center of the posterior uterine surface, along with adenomyosis. When summarizing, these lesions are shown as A and E, and when scoring, each lesion is given 3 points, giving a total of 6 points. However, in some data of this research, E lesions between 1cm and 2cm are scored as 3 points, between 2cm and 3cm as 6 points, and larger than 3cm as 10 points.

- V.

- Rare-site Endometriosis: Rare-site Endometriosis is treated separately from the abovementioned four states. The diagnostic methods vary depending on the location of the lesion. Lesions considered for rare-site endometriosis evaluation include intestinal endometriosis, bladder endometriosis, ureteral endometriosis, vaginal endometriosis, cutaneous endometriosis, etc. If these are observed, they are added to the end of the NMS-E as additional notation (Appendix A - Example 5). In scoring, rare-site endometriosis is tentatively assigned 10 points.

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

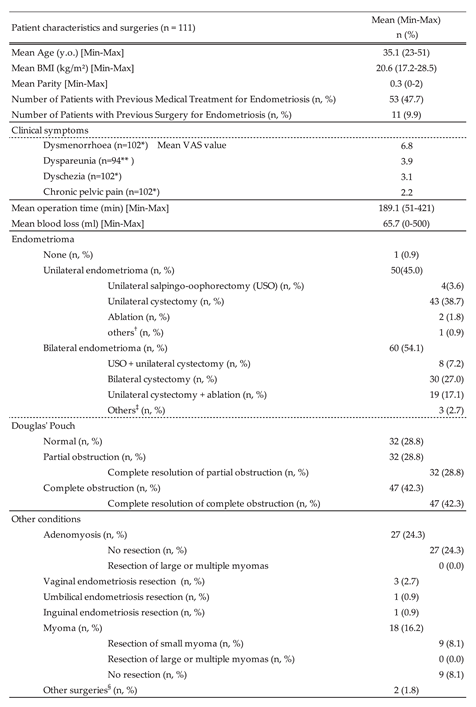

3.1. Demographics, Clinical Presentation, and Surgical Interventions in Endometriosis Patients

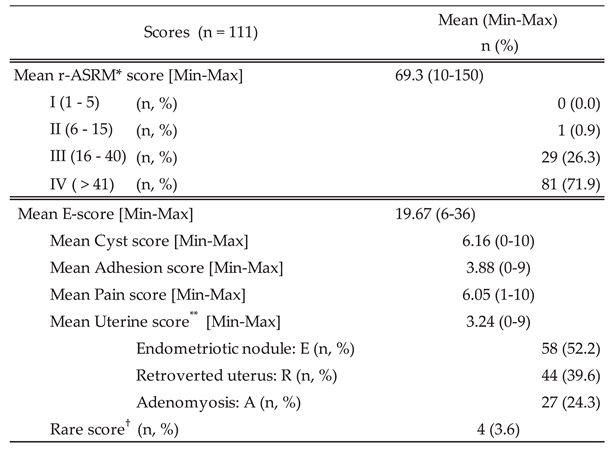

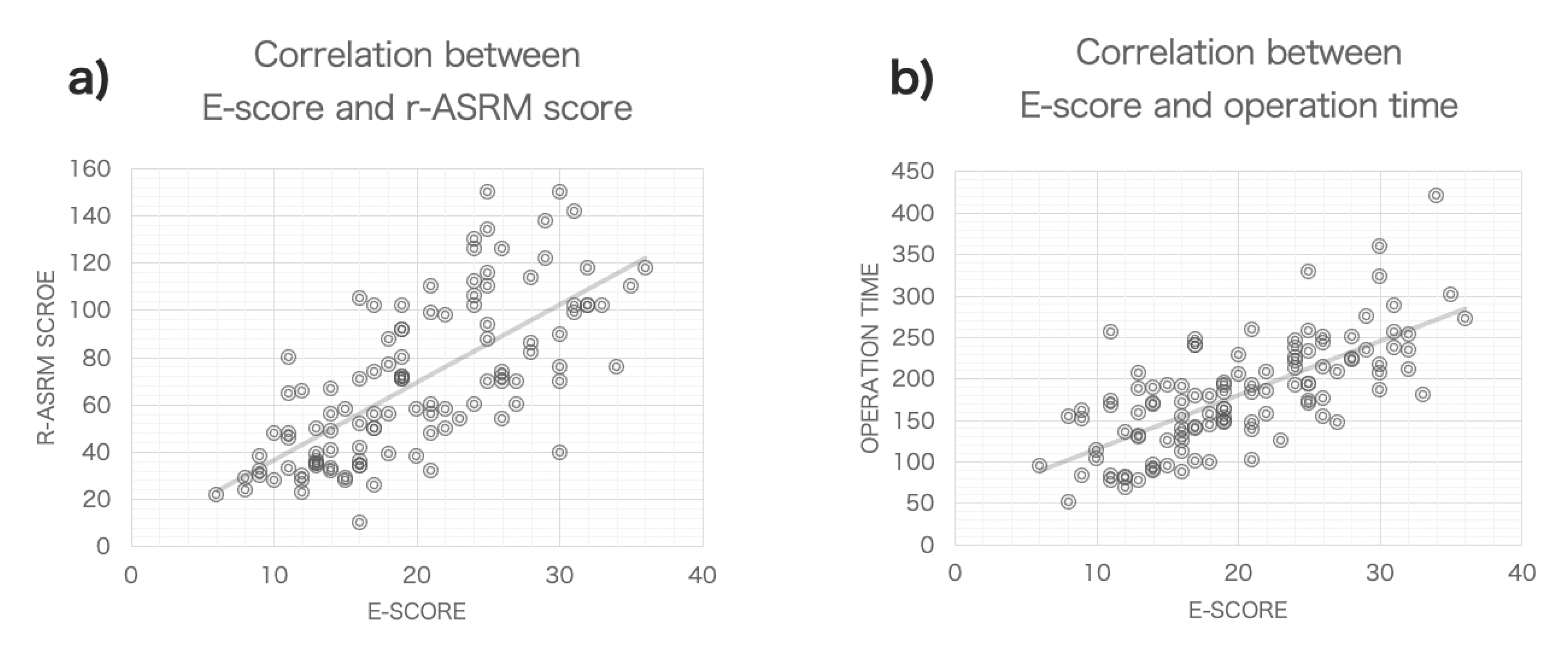

3.1.1. Assessment of Endometriosis Severity Using r-ASRM and E-Score Metrics

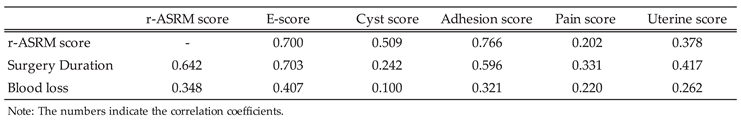

3.1.2. Correlation of Endometriosis Scoring Systems with Surgical Duration and Blood Loss

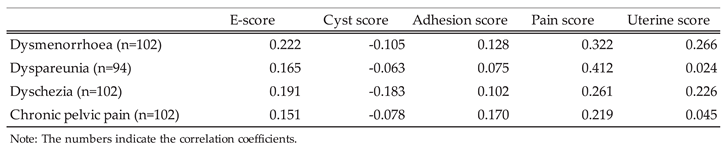

3.1.3. Correlation of Endometriosis Scoring Systems with Clinical Symptoms

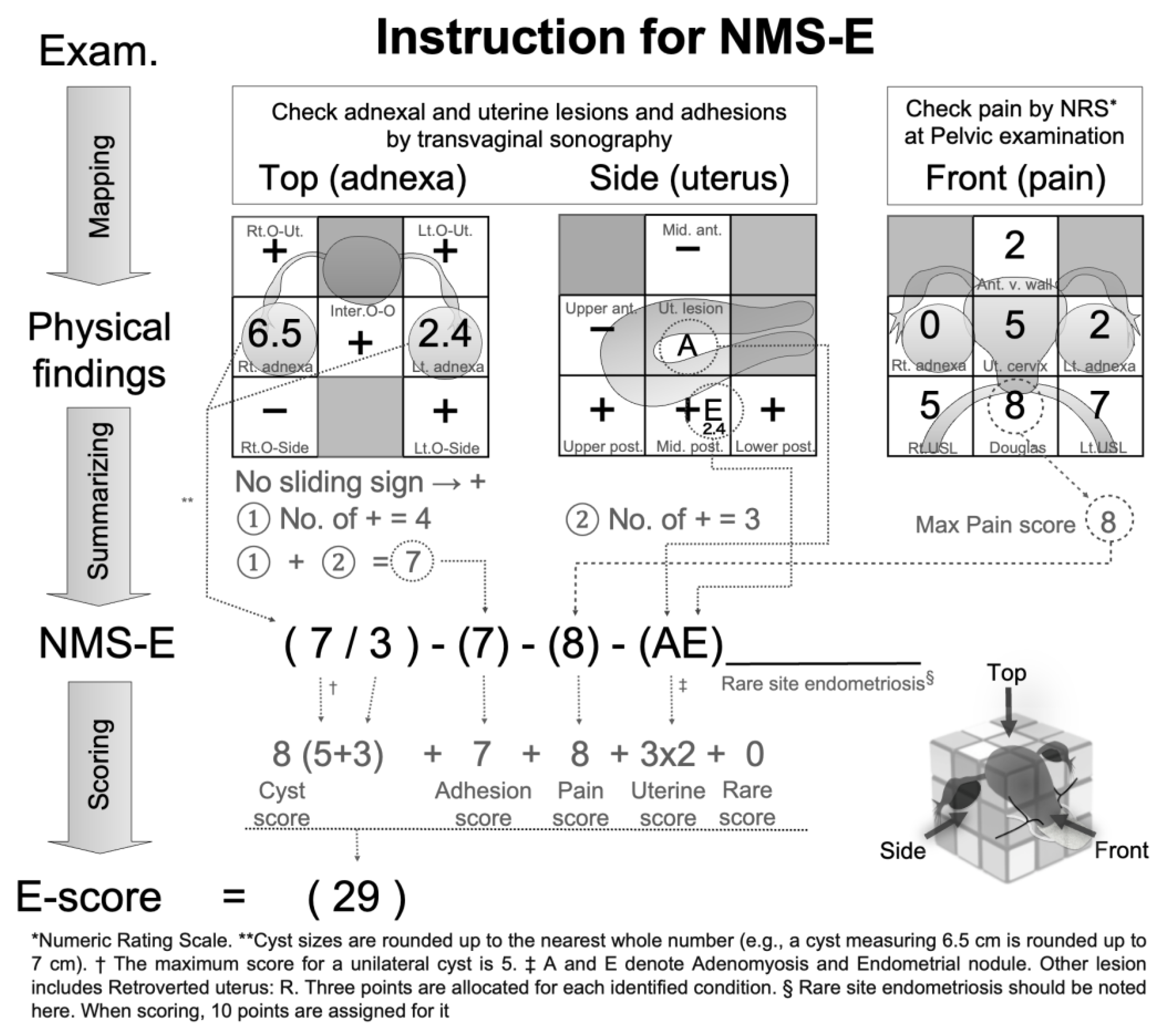

3.2. Refinement of Endometriotic Nodules Scoring and Its Impact on Surgical Duration Prediction in Endometriosis Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

NMS-E Examples

References

- Society, T.A.F. , Revised American Fertility Society classification of endometriosis: 1985. Fertil Steril 1985, 43, 351–2. [Google Scholar]

- Medicine, A.S.f.R. , Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril 1997, 67, 817–21. [Google Scholar]

- Society, T.A.F. , Classification of endometriosis. The American Fertility Society. Fertil Steril 1979, 32, 633–4. [Google Scholar]

- Tuttlies, F., et al., [ENZIAN-score, a classification of deep infiltrating endometriosis]. Zentralbl Gynakol. 2005, 127, 275–81.

- Haas, D., et al., Efficacy of the revised Enzian classification: a retrospective analysis. Does the revised Enzian classification solve the problem of duplicate classification in rASRM and Enzian? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013, 287, 941–5.

- Keckstein, J.; Saridogan, E.; Ulrich, U.A.; Sillem, M.; Oppelt, P.; Schweppe, K.W.; Krentel, H.; Janschek, E.; Exacoustos, C.; Malzoni, M.; et al. The #Enzian classification: A comprehensive non-invasive and surgical description system for endometriosis. Acta Obstet. et Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, S., et al., Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) grouUltrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016, 48, 318–32.

- Abrao, M.S., et al., Preoperative Ultrasound Scoring of Endometriosis by AAGL 2021 Endometriosis Classification Is Concordant with Laparoscopic Surgical Findings and Distinguishes Early from Advanced Stages. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 363–373.

- Abrao, M.S.; Andres, M.P.; Miller, C.E.; Gingold, J.A.; Rius, M.; Neto, J.S.; Carmona, F. AAGL 2021 Endometriosis Classification: An Anatomy-based Surgical Complexity Score. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, G.D.; Pasta, D.J. Endometriosis fertility index: the new, validated endometriosis staging system. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 1609–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomassetti, C.; Geysenbergh, B.; Meuleman, C.; Timmerman, D.; Fieuws, S.; D'Hooghe, T. External validation of the endometriosis fertility index (EFI) staging system for predicting non-ART pregnancy after endometriosis surgery. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exacoustos, C.; Malzoni, M.; Di Giovanni, A.; Lazzeri, L.; Tosti, C.; Petraglia, F.; Zupi, E. Ultrasound mapping system for the surgical management of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 102, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattot, C.; Huchon, C.; Paternostre, A.; Du Cheyron, J.; Chouillard, E.; Fauconnier, A. ENDORECT: a preoperative score to accurately predict rectosigmoid involvement in patients with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2019, 2019, hoz007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menakaya, U.; Reid, S.; Lu, C.; Bassem, G.; Infante, F.; Condous, G. Performance of ultrasound-based endometriosis staging system (UBESS) for predicting level of complexity of laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 48, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, N.P.; Hummelshoj, L.; Adamson, G.D.; Keckstein, J.; Taylor, H.S.; Abrao, M.S.; Bush, D.; Kiesel, L.; Tamimi, R.; Sharpe-Timms, K.L.; et al. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 32, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International working group of Aagl, E.E., et al., Endometriosis classification, staging and reporting systems: a review on the road to a universally accepted endometriosis classification(). Hum Reprod Open. 2021, 2021, hoab025.

- Beecham, C.T. Classification of endometriosis. 1966, 28, 437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa, M. , et al., Shinbu shikyuu naimakushou jutsuzen shindan no yoake NMS-E: Numerical Multi-scoring System of Endometriosis (Surgical Treatment of Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis: The Dawn of Preoperative Diagnosis for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis - NMS-E; Numerical Multi-scoring System of Endometriosis). Journal of Japan Society of Endometriosis 2015, 36: 77-81.

- Sekine, M., et al., Shikyuu naimaku shou ni taisuru aratana jutsuzen shindan hou: NMS-E no keichitsu eko ni yoru yuchaku hyouka wa kenja kan de saganai (No Differences in the Evaluation of Adhesions by Transvaginal Ultrasound Between Examiners Using the New Preoperative Evaluation Method NMS-E (Numerical Multi-scoring System of Endometriosis). Journal of Japan Society of Endometriosis. 2016, 37, 133–135.

- Ichikawa, M., et al., Naimakushou byōhen no atarashii rinshōteki hyōkahō - Jūrai no shikyūnaimakushō hyōkahō no tokuchō to kadai, soshite saishin no hyōkahō NMS-E no kaisetsu (A New Clinical Evaluation Method for Endometriosis Lesions: Characteristics and Challenges of Traditional Endometriosis Evaluation Methods, and an Explanation of the Latest Evaluation Method NMS-E). Rinshō Fujinka Sanka (Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics). 2020, 74, 526–537.

- Ichikawa, M.; Akira, S.; Kaseki, H.; Watanabe, K.; Ono, S.; Takeshita, T. Accuracy and clinical value of an adhesion scoring system: A preoperative diagnostic method using transvaginal ultrasonography for endometriotic adhesion. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa, M.; Shiraishi, T.; Okuda, N.; Nakao, K.; Shirai, Y.; Kaseki, H.; Akira, S.; Toyoshima, M.; Kuwabara, Y.; Suzuki, S. Clinical Significance of a Pain Scoring System for Deep Endometriosis by Pelvic Examination: Pain Score. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, S.; Lu, C.; Casikar, I.; Reid, G.; Abbott, J.; Cario, G.; Chou, D.; Kowalski, D.; Cooper, M.; Condous, G. Prediction of pouch of Douglas obliteration in women with suspected endometriosis using a new real-time dynamic transvaginal ultrasound technique: the sliding sign. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 41, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, S.; Ichikawa, M.; Kaseki, H.; Watanabe, K.; Ono, S.; Akira, S.; Takeshita, T. Accuracy of Transvaginal Ultrasonographic Diagnosis of Retroflexed Uterus in Endometriosis, with Magnetic Resonance Imaging as Reference. J. Nippon. Med Sch. 2023, 90, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enzelsberger, S.; Oppelt, P.; Nirgianakis, K.; Seeber, B.; Drahoňovský, J.; Wanderer, L.; Krämer, B.; Grübling, K.N.; Kundu, S.; Salehin, D.; et al. Preoperative application of the Enzian classification for endometriosis (The cEnzian Study): A prospective international multicenter study. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 129, 2052–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, D.; Chvatal, R.; Habelsberger, A.; Schimetta, W.; Wayand, W.; Shamiyeh, A.; Oppelt, P. Preoperative planning of surgery for deeply infiltrating endometriosis using the ENZIAN classification. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 166, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerriero, S.; Ajossa, S.; Gerada, M.; Virgilio, B.; Angioni, S.; Melis, G.B. Diagnostic value of transvaginal 'tenderness-guided' ultrasonography for the prediction of location of deep endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 2452–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnez, O.; Roman, H. Choosing the right surgical technique for deep endometriosis: shaving, disc excision, or bowel resection? Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcázar, J.L.; Martinez, A.; Duarte, M.; Welly, A.; Marín, A.; Calle, A.; Garrido, R.; Pascual, M.A.; Guerriero, S. Two-dimensional hysterosalpingo-contrast-sonography compared to three/four-dimensional hysterosalpingo-contrast-sonography for the assessment of tubal occlusion in women with infertility/subfertility: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum. Fertil. 2020, 25, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).