Submitted:

27 March 2024

Posted:

29 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Primary Care

1.2. Secondary Care

1.3. Tertiary Care

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Evaluating Efficiency in Healthcare

2.2. Model Orientation

2.3. Input & Output Variables

2.4. Second-Stage Tobit Regression Variables

3. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of Efficiency: First-Stage DEA Application

4.2. Determinants of Inefficiency: Second-Stage Tobit Regression

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yip, W. , Hafez R., “Improving Health System Efficiency: Reforms For Improving the Efficiency of Health Systems (Lessons From 10 Country Cases),” World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/185989 (accessed Nov. 24, 2022).

- Alatawi, A.D.; Niessen, L.W.; Khan, J.A.M. Efficiency evaluation of public hospitals in Saudi Arabia: an application of data envelopment analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e031924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasnim, N.; Afzal, M.N.I. An empirical investigation of country level efficiency and national systems of entrepreneurship using Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) and the TOBIT model. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2018, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebaid, A.; Bahari, Z. The Nexus between Government Expenditure and Economic Growth: Evidence of the Wagner’s Law in Kuwait. Rev. Middle East Econ. Finance 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabah, A.M.; Haghparast-Bidgoli, H.; Skordis, J. Measuring the Efficiency of Public Hospitals in Kuwait: A Two-Stage Data Envelopment Analysis and a Qualitative Survey Study. Glob. J. Heal. Sci. 2020, 12, p121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Perrelle, L.; Radisic, G.; Cations, M.; Kaambwa, B.; Barbery, G.; Laver, K. Costs and economic evaluations of Quality Improvement Collaboratives in healthcare: a systematic review. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibbee, A. , Padrini F., “Balancing Health Care Quality and Cost Containment,” Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/557213833552 (acessed Nov. 12, 2022).

- Balkhi, B.; Alshayban, D.; Alotaibi, N.M. Impact of Healthcare Expenditures on Healthcare Outcomes in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region: A Cross-Country Comparison, 1995–2015. Front. Public Heal. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Kiadaliri, A.; Jafari, M.; Gerdtham, U.-G. Frontier-based techniques in measuring hospital efficiency in Iran: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 312–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell M., J. , “The measurement of productive efficiency,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, vol. 120, 1957. http://www.jstor. 2343. [Google Scholar]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Some Models for Estimating Technical and Scale Inefficiencies in Data Envelopment Analysis. Manag. Sci. 1984, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Makuta, I.F. Changes in productivity in healthcare services in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2022, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker R., D. , Cooper W. W., Seiford L. M., Zhu J., “Returns to scale in DEA" in Handbook on Data Envelopment Analysis, 2nd ed, Springer, 2011, pp. 41-70.

- Gok, M.S.; Sezen, B. Analyzing the Efficiencies of Hospitals: An Application of Data Envelopment Analysis. J. Glob. Strat. Manag. 2011, 2, 137–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, B. Non-Parametric and Parametric Applications Measuring Efficiency in Health Care. Heal. Care Manag. Sci. 2003, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varabyova, Y.; Müller, J.-M. The efficiency of health care production in OECD countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-country comparisons. Heal. Policy 2016, 120, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, V.J.M.; Poh, K.L. Integrated Analysis of Healthcare Efficiency: A Systematic Review. J. Med Syst. 2017, 42, 8–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou El-Seoud M., S. , “Measuring efficiency of reformed public hospitals in Saudi Arabia: An application of data envelopment analysis,” International Journal of Economics and Management Sciences, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 36-62, 2013. [CrossRef]

- O’neill, L.; Rauner, M.; Heidenberger, K.; Kraus, M. A cross-national comparison and taxonomy of DEA-based hospital efficiency studies. Socio-Economic Plan. Sci. 2008, 42, 158–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynkkynen, L.-K.; Vrangbæk, K. Comparing public and private providers: a scoping review of hospital services in Europe. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-S.; Chiu, C.-M.; Huang, Y.-C.; Lang, H.-C.; Chen, M.-S. Evaluating the Operational Efficiency and Quality of Tertiary Hospitals in Taiwan: The Application of the EBITDA Indicator to the DEA Method and TOBIT Regression. Healthcare 2021, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshkumar, P.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: Understanding the best evidence in primary healthcare. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2013, 2, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatawi, A.D.; Niessen, L.W.; Khan, J.A.M. Determinants of Technical Efficiency in Public Hospitals: The Case of Saudi Arabia. Heal. Econ. Rev. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.; Newbrander, W. Tackling wastage and inefficiency in the health sector. World Health Forum. 1994, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Demerjian, P.; Lev, B.; McVay, S. Quantifying Managerial Ability: A New Measure and Validity Tests. Manag. Sci. 2012, 58, 1229–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.-K.; Chen, L.-C.; Li, R.-K.; Tsai, C.-H. Using the DEA-R model in the hospital industry to study the pseudo-inefficiency problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 2172–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyphur M., J. , Zhang Z., Preacher K. J., Bird L. J., Humphrey S. E., LeBreton J. M., "The handbook of multilevel theory, measurement, and analysis, 1st ed, American Psychological Association, 2018.

- Coelli T., J. , Rao D. S. P., O’Donnell C. J., Battese G. E., "An introduction to efficiency and productivity analysis. 2nd ed, Springer, 2005.

- Sarkis, J.; Talluri, S. Efficiency measurement of hospitals: issues and extensions. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

1 No slacks were reported for the discharges output variable. The amount of slack for each inefficient hospital, along with their target values show precise inputs and outputs quantities each inefficient hospital should aim to reach for that hospital to achieve full efficiency. It is not provided in this paper due to limited publication space. |

2 *P ≤0.10, 10% level of significance. **P ≤0.05, 5% level of significance. ***P ≤0.01, 1% level of significance. Standard errors are adjusted for clustered observations. |

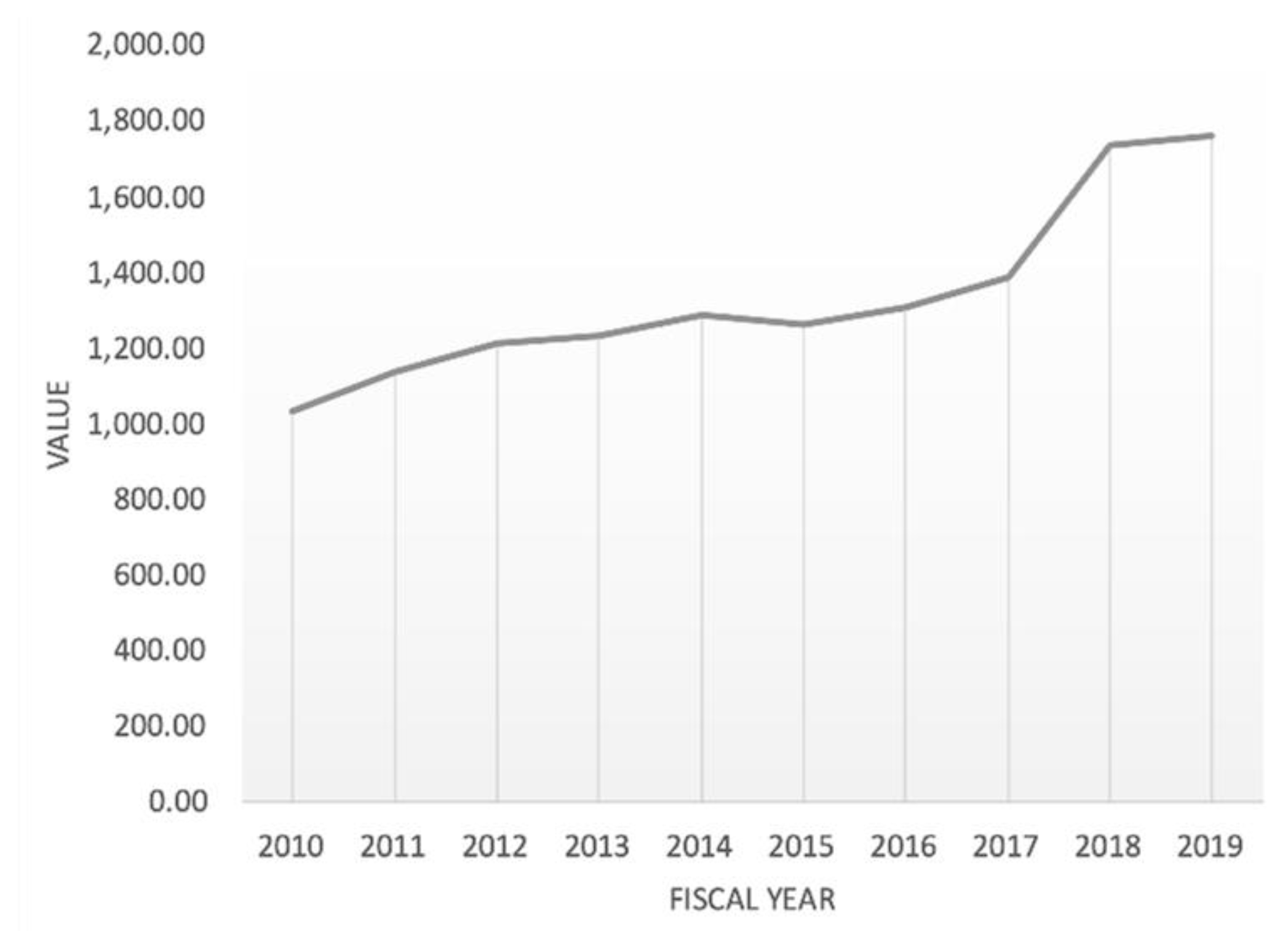

| DATE | VALUE | CHANGE % |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 1,758.67 | 1.43% |

| 2018 | 1,733.81 | 25.22% |

| 2017 | 1,384.58 | 5.85% |

| 2016 | 1,308.11 | 3.89% |

| 2015 | 1,259.18 | -2.01% |

| 2014 | 1,285.01 | 4.58% |

| 2013 | 1,228.77 | 1.34% |

| 2012 | 1,212.57 | 6.89% |

| 2011 | 1,134.39 | 9.77% |

| 2010 | 1,033.38 | 1.65% |

| CRS technical efficiency | VRS technical efficiency | Scale efficiency | RTS | Public hospital type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | |||||

| Al-Adan | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al-Amiri | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.98 | IRS | General |

| Al-Farwaniya | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al-Jahra | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al-Sabah | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.98 | IRS | General |

| Mubarak Al-Kabir | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.98 | DRS | General |

| Al-Razi | 0.70 | 0.70 | 1.00 | IRS | Specialized |

| Physical Med. & Rehab Facility | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Maternity Hospital | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | DRS | Specialized |

| Chest Diseases Hospital | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.92 | IRS | Specialized |

| Infectious Disease Facility | 0.33 | 0.56 | 0.59 | IRS | Specialized |

| Ibn Sina Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Kuwait Cancer Control Center | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.81 | IRS | Specialized |

| Allergy & Respiratory Center | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Sabah Al-Ahmad Urology Center | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | IRS | Specialized |

| Average | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.92 | ----- | ----- |

| 2016 | |||||

| Al-Adan Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al-Amiri Hospital | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.96 | IRS | General |

| Al-Farwaniya Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al -Jahra Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al-Sabah Hospital | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.98 | IRS | General |

| Mubarak Al-Kabir Hospital | 0.78 | 0.78 | 1.00 | IRS | General |

| Al-Razi Hospital | 0.64 | 0.64 | 1.00 | DRS | Specialized |

| Physical Med. & Rehab Facility | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Maternity Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Chest Diseases Hospital | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.91 | IRS | Specialized |

| Infectious Disease Facility | 0.30 | 0.53 | 0.56 | IRS | Specialized |

| Ibn Sina Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Kuwait Cancer Control Center | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.78 | IRS | Specialized |

| Allergy & Respiratory Center | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Sabah Al-Ahmad Urology Center | 0.47 | 1.00 | 0.47 | IRS | Specialized |

| Average | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.91 | ----- | ----- |

| 2017 | |||||

| Al-Adan Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al-Amiri Hospital | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.96 | IRS | General |

| Al-Farwaniya Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al -Jahra Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al-Sabah Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Mubarak Al-Kabir Hospital | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1.00 | IRS | General |

| Al-Razi Hospital | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.97 | DRS | Specialized |

| Physical Med. & Rehab Facility | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Maternity Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Chest Diseases Hospital | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.91 | IRS | Specialized |

| Infectious Disease Facility | 0.42 | 0.63 | 0.67 | IRS | Specialized |

| Ibn Sina Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Kuwait Cancer Control Center | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.80 | IRS | Specialized |

| Allergy & Respiratory Center | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Sabah Al-Ahmad Urology Center | 0.62 | 1.00 | 0.62 | IRS | Specialized |

| Average | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.93 | ----- | ----- |

| 2018 | |||||

| Al-Adan Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al-Amiri Hospital | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.98 | IRS | General |

| Al-Farwaniya Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al -Jahra Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al-Sabah Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Mubarak Al-Kabir Hospital | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.99 | IRS | General |

| Al-Razi Hospital | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.96 | IRS | Specialized |

| Physical Med. & Rehab Facility | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Maternity Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Chest Diseases Hospital | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.92 | IRS | Specialized |

| Infectious Disease Facility | 0.44 | 0.73 | 0.60 | IRS | Specialized |

| Ibn Sina Hospital | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.98 | IRS | Specialized |

| Kuwait Cancer Control Center | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.81 | IRS | Specialized |

| Allergy & Respiratory Center | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Sabah Al-Ahmad Urology Center | 0.46 | 1.00 | 0.46 | IRS | Specialized |

| Average | 0.791 | 0.860 | 0.914 | ----- | ----- |

| 2019 | |||||

| Al-Adan Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al-Amiri Hospital | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.97 | IRS | General |

| Al-Farwaniya Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al -Jahra Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | General |

| Al-Sabah Hospital | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.97 | IRS | General |

| Mubarak Al-Kabir Hospital | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.98 | DRS | General |

| Al-Razi Hospital | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.97 | DRS | Specialized |

| Physical Med. & Rehab Facility | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Maternity Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Chest Diseases Hospital | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.92 | IRS | Specialized |

| Infectious Disease Facility | 0.28 | 0.56 | 0.50 | IRS | Specialized |

| Ibn Sina Hospital | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Kuwait Cancer Control Center | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.82 | IRS | Specialized |

| Allergy & Respiratory Center | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | CRS | Specialized |

| Sabah Al-Ahmad Urology Center | 0.57 | 1.00 | 0.57 | IRS | Specialized |

| Average | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.91 | ----- | ----- |

| Pooled 2015-2019 sample (N=75 observations) | |||||

| CRS technical efficiency | VRS technical efficiency |

Scale efficiency |

IRS [N (%)] |

DRS [N (%)] |

|

| Mean | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 34 (45.3%) | 6 (8%) |

| Std. dev. | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| Min. | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.91 | ||

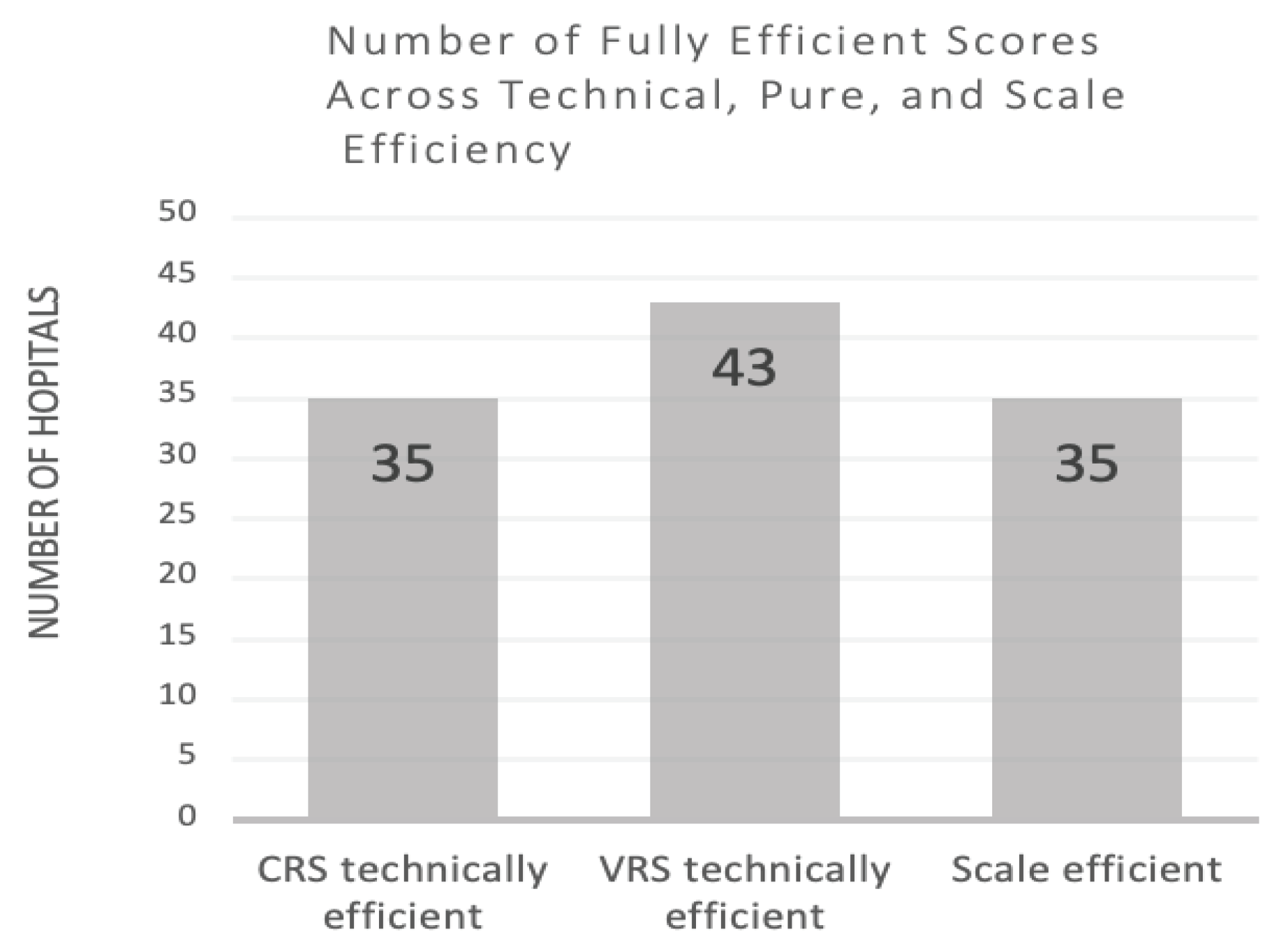

| No. of fully efficient scores | 35 (46.7%) |

43 (57.3%) | 35 (46.7%) |

||

| Input Slacks | Mean difference of values from targets | Standard Deviation |

Percent change to target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Beds | 67.10 | 77.76 | -16.37 |

| Physicians | 75.71 | 124.83 | -18.83 |

| Nurses | 169.23 | 212.93 |

-16.84 |

| Output Slacks | |||

| Outpatient & Emergency Visits | 4955.39 |

30509.59 |

1.13 |

| Explanatory Variables | Tobit Regression Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Hospitalbeds >327 (dummy variable for capacity) | 0.263*** |

| Catchment area population(n) | -0.00000159*** |

| External causes of morbidity & mortality in catchment area(n) | -0.0584 |

| <1 yr olddeaths in catchment (n) | 0.04891 |

| Females (%) | -0.0965* |

| Non-Kuwaitis (%) | -0.2083** |

| Children <5 years (%) | -3.632 |

| Elderly ≥65 years (%) | -21.107* |

| Physician-to-nurse ratio | 0.482** |

| Nurses per bed ratio | -0.0024* |

| _Constant | 2.906*** |

| Wald chi2(10) | 43.35 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000*** |

| Log pseudolikelihood | -4.986 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).