1. Introduction

In recent years, the frequency and severity of natural disasters such as floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, and wildfires have increased worldwide [

1]. These disasters have devastating impacts on communities and individuals. For instance, according to the emergency events database (2024), 1.7 billion people have been impacted by natural disasters over the last decade (2013-2023), killing 319,931 people and resulting in over 1.9 trillion USD in damage cost. Natural disasters have caused substantial damage to human lives beyond mortality in many aspects. In terms of physical damages, people lose their properties, infrastructure and services (electricity, transportation, water supply, and alike), immediately after a significant disaster [

3]. Nevertheless, disasters often deliver long-term consequences on people's lives including job losses, emotional breakdowns, financial downturns, injuries, and disabilities [

4,

5]. Therefore, it is crucial for the disaster management community to seek and adopt novel and improved approaches to fully prepare, effectively respond, and successfully recover from disasters.

Social media (SM) has emerged as a valuable technology in aiding disaster management (DM) activities in the prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery phases of the disaster management cycle [

1,

6]. It facilitates two-way communication, where people become both the producer and the consumer of the information [

7]. Furthermore, the ubiquitous nature of social media has ensured that real-time disaster information is shared with a wider audience, including individuals, government bodies, media, and non-government organisations. For example, according to Lam et al. [

8], SM has served millions of requests by different community sectors, for information, donations, rescue requests, and protection during crisis events.

Despite several applications and advantages, the use of SM in DM was also impeded by various challenges. With the widespread and increased reliance on SM data in disaster management, the risks of misleading information and improper conduct were inevitable. In addition, as discussed previously, people are suffering from the consequences of a critical disaster in the long term. Yet all the community members are not benefited equally by social media platforms [

9]. Undoubtedly, these circumstances of social media are creating serious challenges for the use of SM as a disaster management tool [

10]. As a result, investigating the possible strategies to overcome these challenges in SM use for DM is also essential. Unfortunately, only limited attention has been given to exploring the challenges and strategies within the current research landscape. Several researchers, including [

8] and Singla and Agrawal [

11], have emphasised the need for new/ improved concepts across disciplinary and methodological boundaries to address these challenges, and to ensure the validity and reliability of SM data. Therefore, this study aims to conduct a comprehensive literature review to identify current challenges and possible strategies in the context of SM and DM. Below objectives were established to achieve the aim of the study:

Identify the SM platforms used in different types of disasters

Identify the community-related challenges for using SM in DM

Examine the strategies to overcome challenges for using SM in DM

The rest of the paper is organised into four main sections.

Section 2 explains the methodology adopted for the study, whereas the bibliometric analysis of the publications is presented in

Section 3.

Section 4 addresses the results and findings under each objective of the study. Finally, the conclusions, along with the practical implications, recommendations and future research possibilities are presented in

Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

The study conducted a systematic review of the literature to fully assess the challenges and strategies related to the application of SM in DM. A method of systematic identification and collation of available literature under a research focus is commonly referred to as a systematic literature review [

12]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 protocol was followed to conduct the systematic review. PRISMA, as a comprehensive guideline, aims to enhance the transparency and scientific quality of reported systematic reviews or meta-analyses [

13] [

14]. According to Snyder [

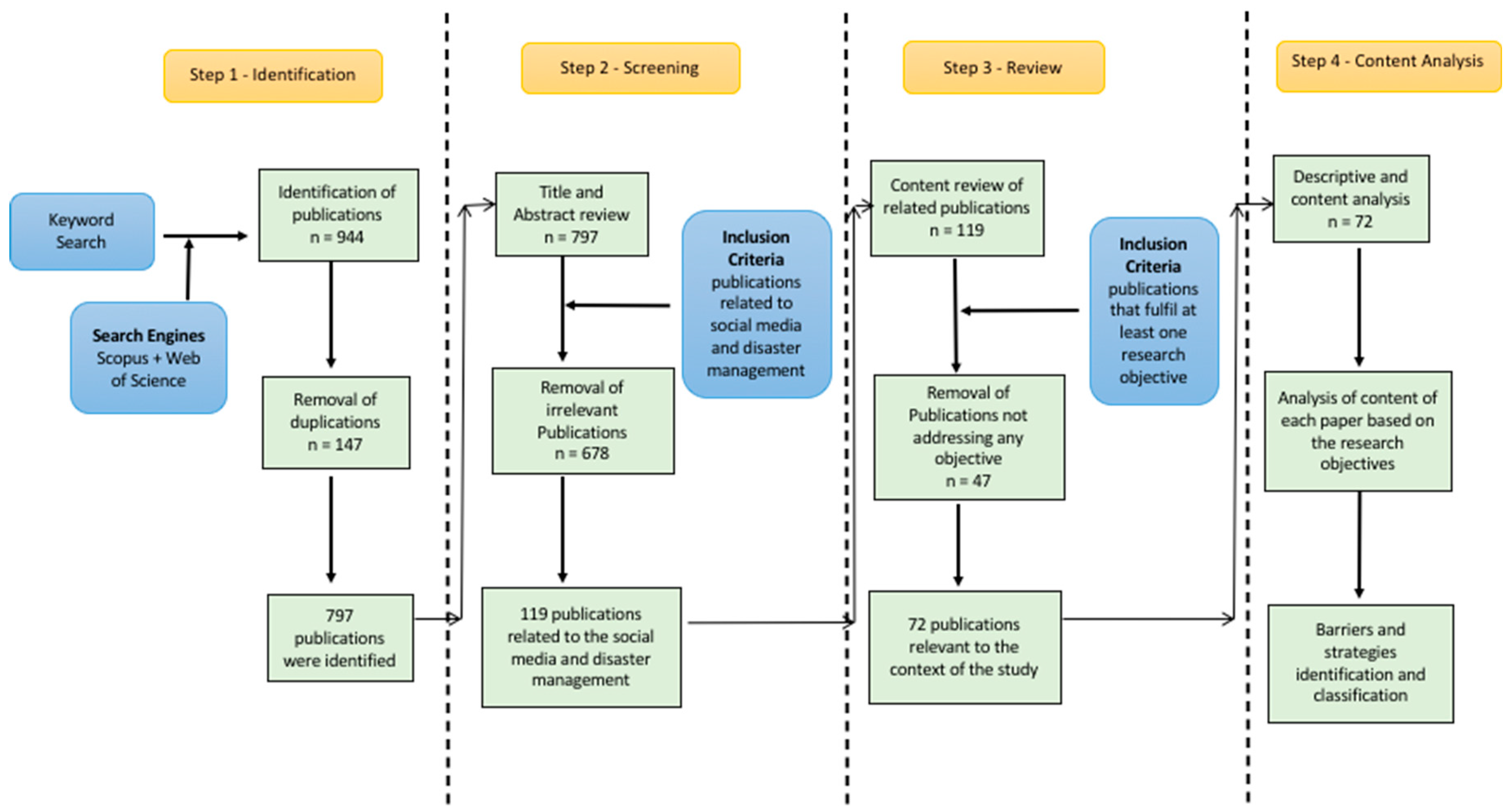

15], this type of review follows a rigorous and transparent process that involves identification, critical appraisal, and synthetisation of relevant research. The methodological process involved a preliminary database search, screening of retrieved literature and a descriptive analysis of the most relevant literature. Subsequently, a four-stage selection process was employed to select the most relevant publications for content analysis. This process incorporated the identification of available literature (Step 1), review of title and abstract (Step 2), content review (Step 3), and descriptive content analysis (Step 4).

Figure 1 depicts an overview of the research process adopted for the study.

2.1. Identification of Papers

To identify pertinent publications related to the research focus, the study utilised two prominent databases, Scopus, and Web of Science. The initial literature retrieval was performed using the Scopus database, given its extensive coverage of scientific publications [

16]. A careful combination of keywords and Boolean operators was employed to retrieve publications from each database; ("Social media" OR "Facebook" OR "Twitter" OR "WeChat" OR "Instagram" OR "snapchat" OR "YouTube" OR "reddit" OR "WhatsApp" ) AND ( "Prevent*" OR "prepare*" OR "response" OR "recover*" OR "manage*" ) AND ( "Disaster" OR "bushfire" OR "Wildfire" OR "Flood" OR "Hazard" OR "emergenc*" OR "Earthquake" OR "Drought" OR "tsunami" OR "Cyclone" OR "Landslide" OR "Volcano*" OR "Hurricane" OR "Storm" OR "Heatwave" ) AND ( "Communit*" OR "Generation" OR "Age cohort" OR "underserved" OR "vulnerable" OR "well served" OR "young" ) AND ( "barrier" OR "obstacle" OR "challenge" OR "Strateg*" OR "tactic"). To increase the likelihood of capturing all relevant academic papers, specific names of certain social media platforms and disasters were incorporated as keywords. Consequently, the identification of challenges is more focused towards the communities to ensure the study is contextually valuable, culturally sensitive, and inclusive. While there were no constraints on the year of publication during the retrieval of publications, the language was limited to English. However, to uphold the methodological rigor of this systematic review, non-academic and technical documents such as reports, discussions, websites, and similar materials were deliberately omitted, notwithstanding their widespread accessibility.

Through a primary search in the Scopus database, 657 publications were identified in total. Following an expanded search in the Web of Science database, 147 papers were found to be duplicated. As a result, no further database searches were conducted. The expanded search in the Web of Science database resulted in retrieving 140 unique publications. Consequently, the preliminary database search yielded 797 distinct publications, all of which were published prior to the cut-off date of November 22, 2023. These 797 articles underwent a screening process, which involved a thorough examination of the title and abstract to assess their suitability for inclusion in the systematic review. The screening process led to the exclusion of 678 articles. In the subsequent phase of the process, a content review was conducted on the remaining 119 publications to further evaluate their alignment with the research objectives. This resulted in a selection of 72 articles as the most pertinent publications for descriptive and content analysis. A summary of the relevant papers and their sources are presented in

Table 1.

2.2. Descriptive and Content Analysis

In this stage, a final number of 72 articles were used to conduct bibliometric and content analysis. Frequency counts were used to obtain an overview of the years of publication and the distribution of the articles. This was also supported by data visualisation and analysis software. The main software used in this study to perform bibliometric analysis is VOS Viewer. It was used to analyse and visualise the data using a co-occurrence network of the bibliometric data. Consequently, the content of the relevant 72 papers was categorised according to research objectives in the form of a codebook. All available information from each paper and for each objective was identified and reported. While some of the papers explicitly indicated the challenges and strategies, others required thorough analysis to identify them. Based on this analysis, the final set of challenges and strategies for the use of SM in DM were conceptualised.

3. Bibliometric Analysis of the Publications

3.1. Co-occurrence Network of Keywords

Keywords of a particular research reflect the theme of the study. When all keywords are mapped together, in a specific field of study, it provides a clear representation of the existing knowledge area [

87,

88]. Also, the network of co-occurrence keywords illustrates the scholarly relationships between keywords. Therefore, a keyword co-occurrence network was created for the current study utilising the VOS viewer software. Out of the available keyword types (author keywords, index keywords and all keywords), the author keywords were used to illustrate the keywords' co-occurrence network. This limitation helped to generate a readable and clear image of the main keywords.

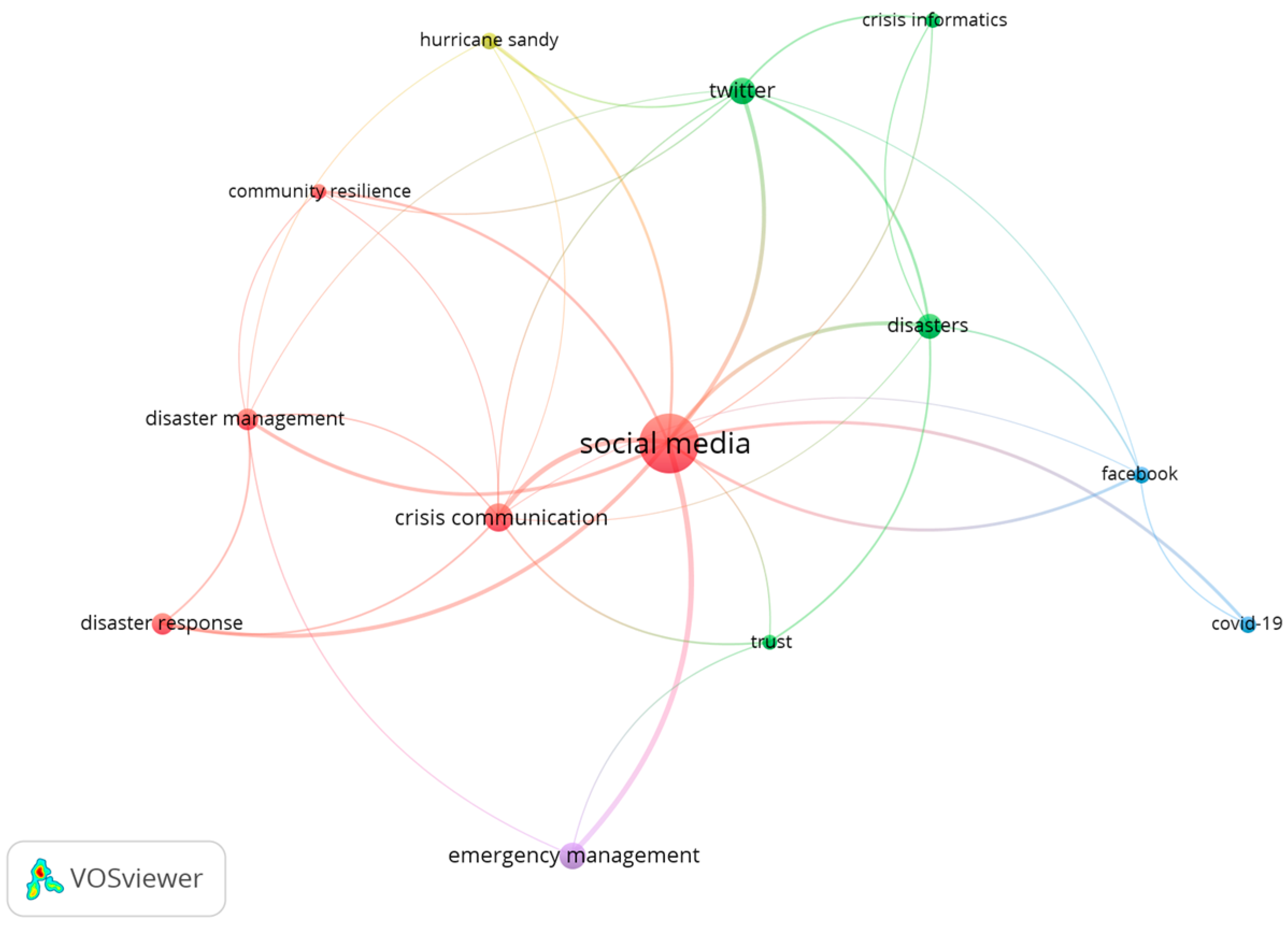

In VOS viewer, the minimum number of occurrences of a keyword was set to 3, in order to generate an optimum and legible network. Out of 208 keywords, 13 keywords met the threshold with 5 clusters, 35 links and a total link strength of 51, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Furthermore, the keywords which express the same meaning, such as disaster and disasters, crisis communication, communication, and disaster communication, were merged to appear as disasters and crisis communication respectively. The size of each node indicates the number of occurrences of the keyword, while the link strength connecting two keywords shows the number of articles in which they appeared together [

89]. The top keywords identified from the illustrated network are social media, crisis communication, emergency management, twitter, and disasters. It was also identified that the ‘social media’ keyword is strongly linked (highly appeared) with the emergency management, crisis communication, disasters, and disaster management keywords respectively.

3.2. Collaboration Network of Countries

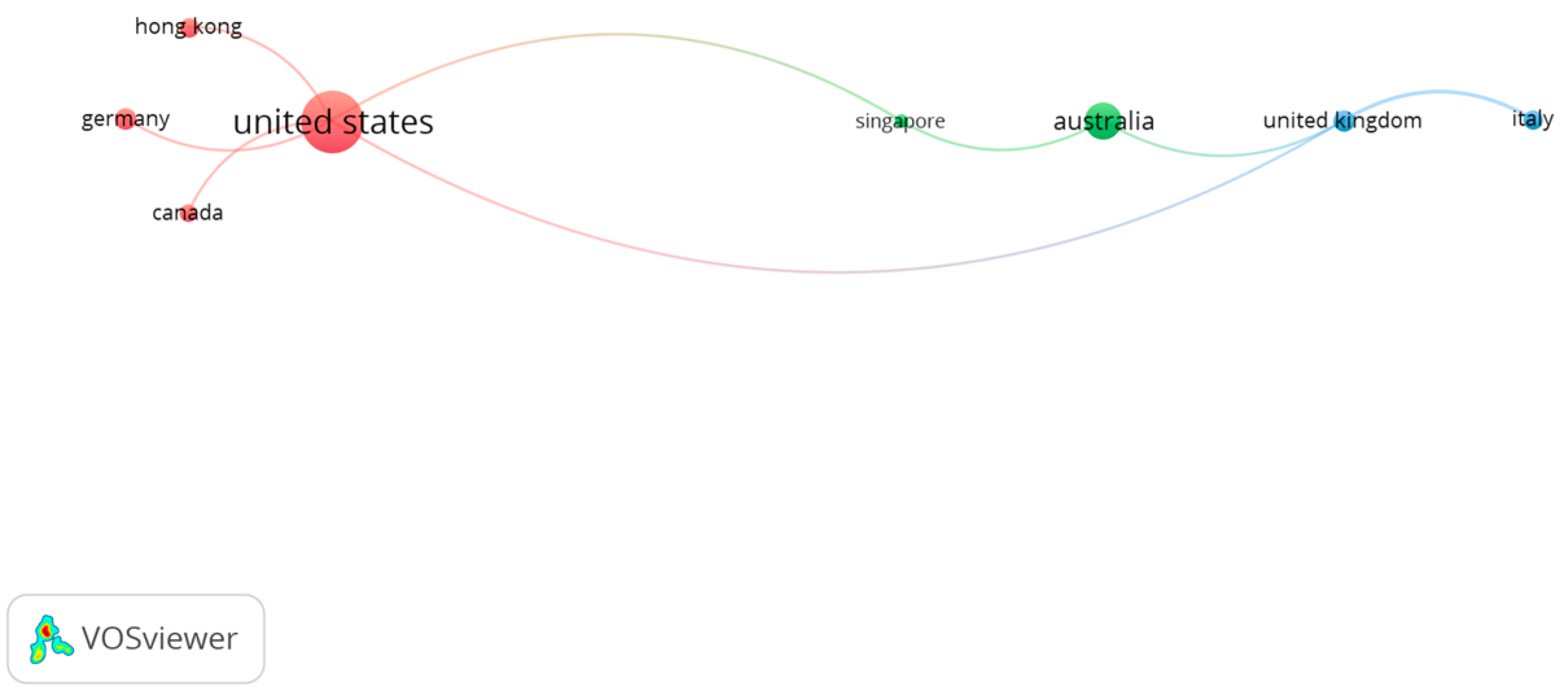

The collaboration network of countries helps determine which nations are leading the research in a particular field. Some countries contribute to a specific research domain than others. Therefore, an internationally collaborative network of countries was illustrated using the same software, VOS Viewer, to determine the leading publications and their collaborations across nations. The minimum number of documents and citations of a country were both set to 2. This again helped in establishing an optimum and legible network. Even though, 9 countries out of 21 met this threshold, only 8 were found to be connected.

Figure 3 depicts the International collaboration network of the countries with 3 clusters, 8 links and a total link strength of 9. The size of the node indicates the number of documents published by each country related to SM in DM. The United States, Australia, Germany, and the United Kingdom have published a relatively higher number of publications. The variation of publications among active countries is presented in

Table 2, along with the number of citations and total link strength. The United States leads the SM in the DM research field, followed by Australia and the United Kingdom. This review is limited to articles published in English. This language limitation may be certainly a factor to this level of dominance by English-speaking countries. In terms of co-authorship, the United Kingdom and Italy emerge as the highly collaborative countries in publications. Subsequently, the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Italy, and Singapore exhibit a significant level of collaboration.

3.3. Annual Trend of Publications

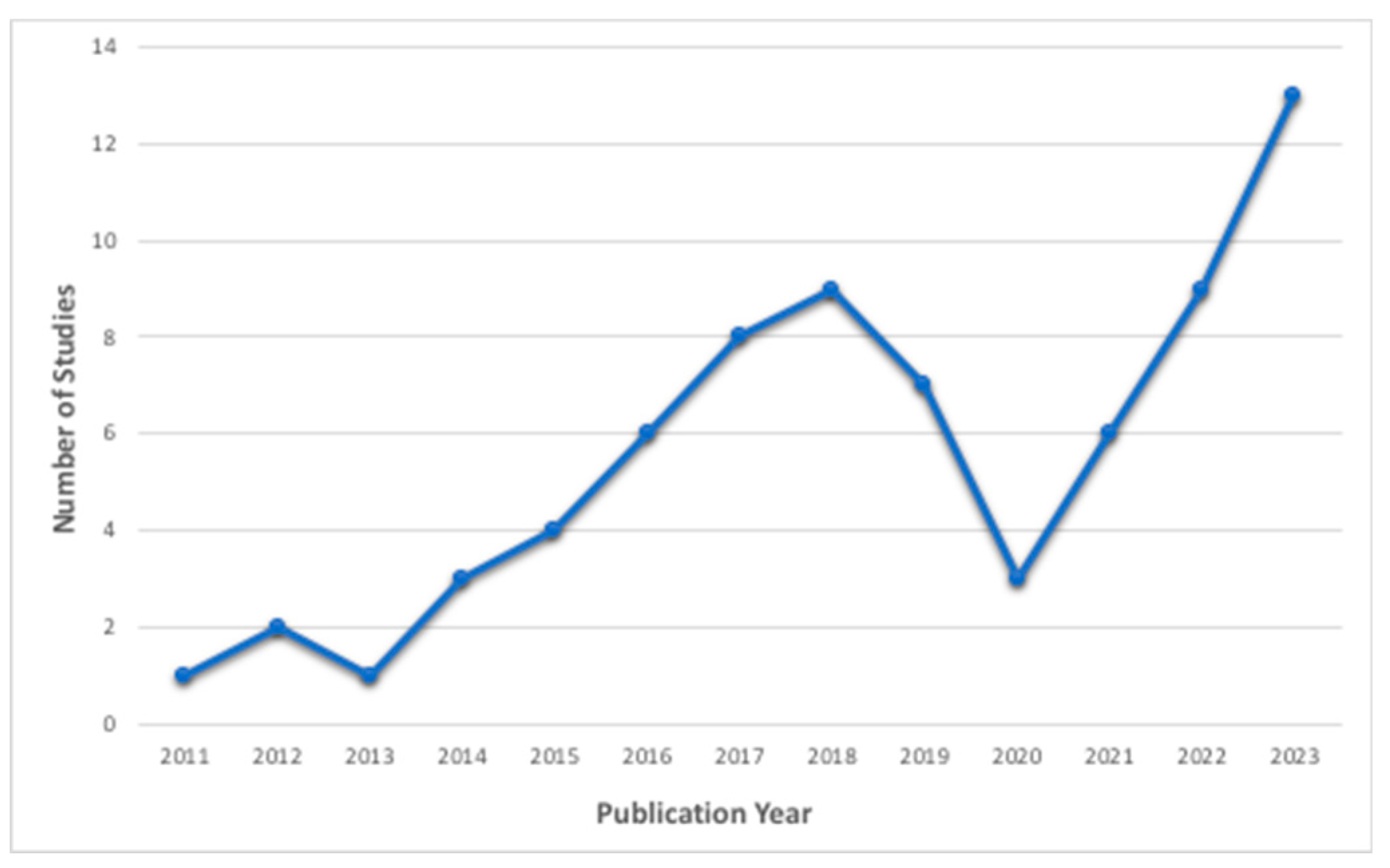

The annual publication trend indicates the level of attention given to a specific field of study by both researchers and industry practitioners.

Figure 4 presents the yearly publication pattern for the current study. Despite having no restrictions on the publication year of the articles, the first relevant paper on the use of SM in DM emerged in 2011. This is not surprising, as a noticeable number of studies on the topic have been published around 2010, following a very limited publication period of 2006–2010 [

90]. Since then, the utilisation of SM in DM studies has grown gradually until 2020, in line with the previous reviews of Ogie et al. [

3] and Fauzi [

90]. However, a slight decline in publications was observed in 2019 and 2020, possibly due to the shifted focus towards COVID-19 research. Nevertheless, there was a significant increase in the number of studies from 2020 to 2023. The number reached its peak with 13 articles in 2023. Overall, there was little and varied progress in the articles published on SM in DM until 2020, and the annual trend of published articles has dramatically increased afterwards.

4. Content Analysis of the Publications

4.1. Social Media Platforms and Disaster Types

In reviewing the articles, the SM platforms and disaster types were recorded and illustrated. This facilitates the researchers to understand the frequency of disaster types and SM platforms documented in the reviewed literature. It is usual to encounter an article involving multiple disaster types and SM platforms in a single study. In contrast, some articles have not utilised any of the specific disaster types or SM platforms. Instead, they have generally investigated the use of SM for DM in their studies. Therefore, the total count of the illustrated SM platforms and disaster types is not precisely aligned with the overall number of studies (72) reviewed.

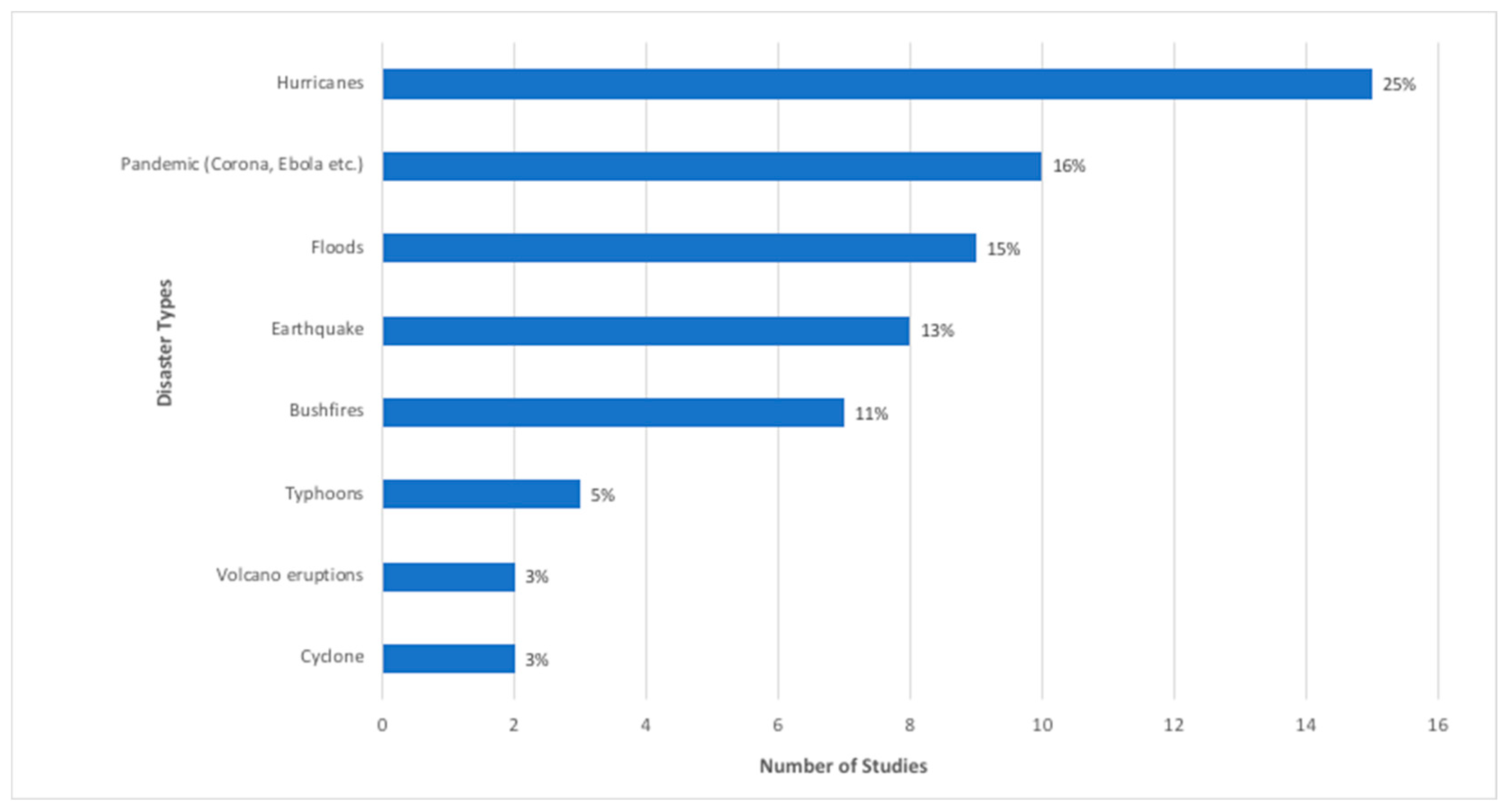

As shown in

Figure 5, hurricanes, pandemics, floods, earthquakes, and bushfires were the most prevalent disasters highlighted in the systematic review. Additionally,

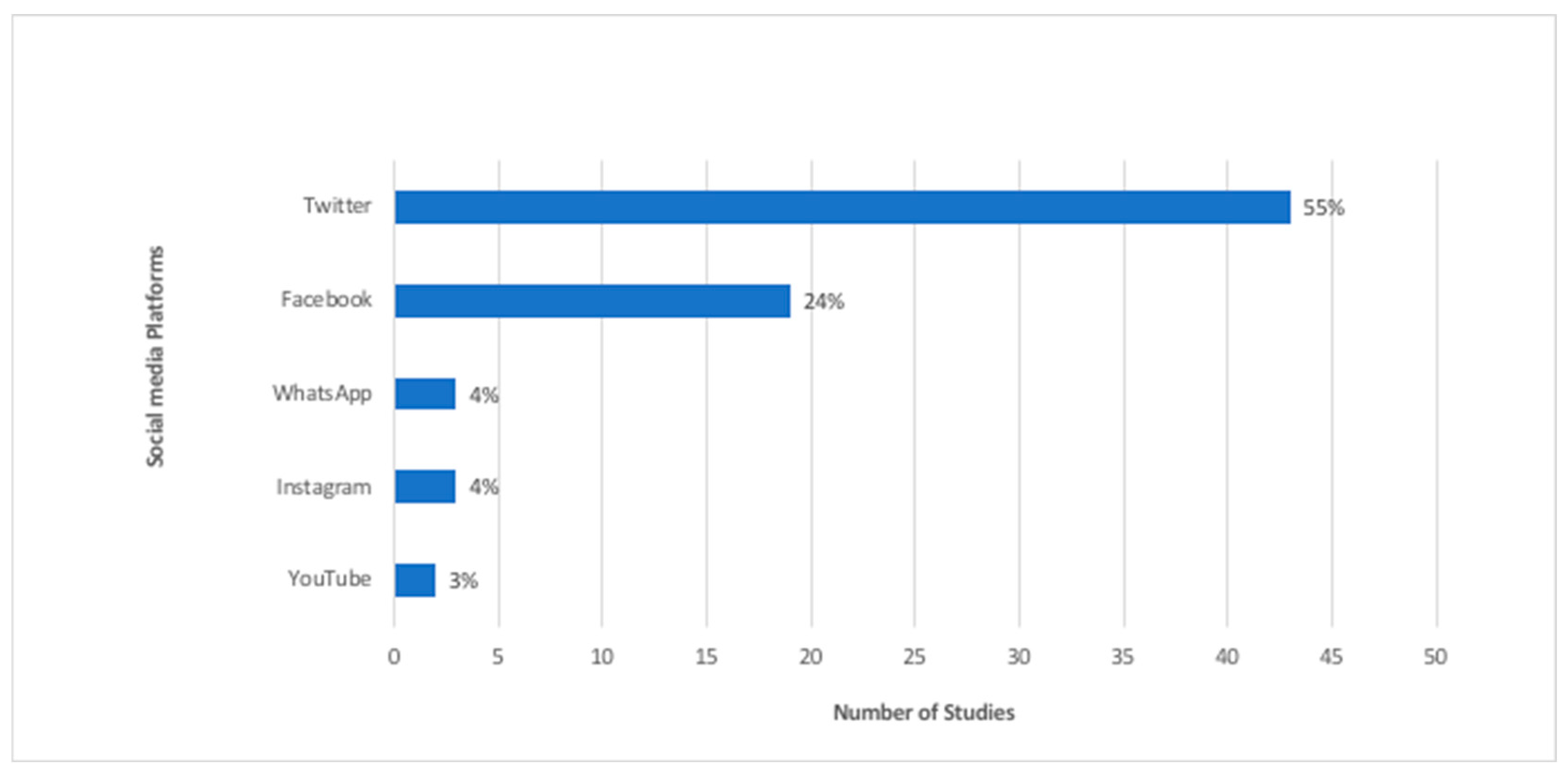

Figure 5 excluded the least reported disasters, such as storms, landslides, tornadoes, heatwaves, and tsunamis, as they have appeared only once in the reviewed literature. Effective management of these disasters was mostly investigated using Twitter as the key SM platform, as depicted in

Figure 6. Twitter was used in 55% of the articles, while Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram were used in 24%, 4%, and 4% of the articles, respectively. All these predominant SM platforms are more common and well-known among social communities. However, the review identified platforms like Myspace, TikTok, Snapchat, Nextdoor, WeChat, Weibo, and Telegram as the least appearing platforms in the literature. Geographical bias, age cohorts, and low popularity might be the reasons for reduced investigations on these platforms by researchers. For instance, being domestic apps, WeChat and Weibo were mostly used in Chinese studies only. TikTok and Snapchat, on the other hand, are still popular with the younger community. With the increasing number of users, especially among younger generations, who are expected to bear the burden of addressing future disaster risks, these platforms may evolve into a leading platform for future DM [

3]. Hence, it will be important for future research to explore the possible and effective use of such platforms in DM.

Overall, the use of SM in DM is highly dominant by hurricanes and Twitter, in terms of disaster type and SM platform, within the reviewed literature. Notwithstanding, the pertinent papers also discussed the management of prevailing disasters such as bushfires, earthquakes, and floods using several social media platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and WhatsApp.

4.2. Challenges to the Use of SM in DM

Following the four-step methodology explained in

Section 2, a total of 18 challenges were identified in the study. The challenges were ranked based on the number of appearances in the analysed papers. Even though the number of appearances is almost same for most of the challenges, there are few exemptions determined. For example, spread of misinformation, insufficient human resources to manage SM use, lack of trust in information and authorities, and poor information quality/ content have been mentioned by several researchers significantly than other challenges. Additionally, some of the challenges emerged from the practical evidence, when researchers were conducting case studies on SM use in DM.

Table 3 presents the identified challenges with their rank and references. The references column of

Table 3 provides the reference to the studies in which the relevant challenge was mentioned and explained.

The challenges were categorised into 6 categories namely, human resources, data, culture, value, technology and language related challenges. This categorisation improves the clarity, understandability and simplicity of the challenges derived from the literature. Further, the categorisation leads the study to establish a conceptual model at the end of the study. The categorisation technique was adopted from the study Anson et al.[

21], where the challenges to the selection and use of SM analysis tools were classified using the same set of categories. The taxonomy of these categories was developed based on the main focus of each challenge. Subsequently, the 5 main categories with their associated challenges are depicted in

Table 4. A detailed discussion of the categorised challenges is then presented in subsequent sections.

4.2.1. Data Related Challenges

The first set of challenges impeding the effective use of SM in DM is data-related challenges. This set of challenges is predominantly associated with the information and its features, disseminated through SM platforms. This set of challenges includes problems related to data verification, poor information, data ownership, data credibility, data processing and analysis. As indicated in previous studies, rumors have been a common concern during disasters [

8]. But the growth of false information, questions the point of using SM as a DM tool [

30], [

72]. consequently, the unavailability of any verification methods to ensure the authenticity of data makes it even more problematic. Further, this false and unverified information negatively affects both the victims and responders by causing failed rescue operations, misallocation of resources and confusion among the public. This misinformation becomes critical when mixed with the poor information quality and content of the posts. Not only these messages easily be mistaken as false news, but also hinder the process of data processing and analysis. Poor quality and content of information include duplicate, incomplete and vague information which resulted in information overload to process and analyse [

72]. Additionally, data from unverified sources are being shared through SM platforms frequently. As a result, a low level of credibility on information disseminated through SM platforms has arisen. This limits the timely and effective decision-making by officials unless reliable information is received [

47]. Therefore, improving methods to detect false news, disseminate quality content, validate the accuracy and reliability of SM data are urgently needed

4.2.2. Social Challenges

The second set of challenges comprises the social aspects of a community, or country, which prevent the smooth implementation of the SM in DM. The findings of the systematic review indicate that spreading misinformation, lack of trust, resistance to change, disparities among social groups, different levels of community expectations, difficulties in learning SM platforms, and insufficient human resources establish the key challenges from a social perspective. Furthermore, language barriers and miscommunications resulting from the linguistic differences of the users also fall under the social category of the classification.

First, the growth of misinformation (inaccurate/outdated information) and disinformation (intentionally misleading/false information) in the form of ‘fake news’ in SM platforms, questions the point of using SM as a DM tool [

30,

91]. Continuous improvement of sharing false information in SM platforms is the most mentioned challenge in the literature. Trust, as a cultural aspect, generally influences how individuals perceive and rely on information. In some cultures, official sources, authorities, and institutions are highly trusted while in others, mistrust is more prevalent. The latter, which is the mistrust towards information and authorities, emerged as a challenge for the use of SM in DM [

41] [

28]. Mistrust towards authorities mostly arises when people believe authorities do not utilise SM as a formal tool to communicate with citizens [

66]. The nature of spreading false news, poor information, and rumors in SM platforms, as explained in section 4.2.1., contributes to the lack of trust towards the information shared. This mistrust prevents community members from seeking information on SM during disasters, making it pointless to share disaster information with them. Community members are not motivated to use SM when their expectations are not met. Similarly, the gap between personal exceptions of emergency services in responding to requests on SM, and the extent to which emergency services are aware of and able to respond to those requests, plays a vital role in the effective utilisation of SM for DM. Additionally, the heterogeneous background of SM users is also a concern within the context of DM. For example, users are found to be biased in SM use, with young, educated, and urban citizens generally using it more [

8]. Conversely, underserved communities such as low socioeconomic status people, old/ isolated people, minor populations, and people with disabilities, barely use any SM platforms [

18]. This raises fundamental questions on the validity of using SM in DM. Finally, fear, uncertainty, and doubt among emergency managers about using new forms of data, such as SM, impose the ‘resistant to change’ behavior within the organisations and thereby challenge the official use of SM as a DM tool.

The effectiveness of using any tools and technologies in DM depends greatly on available resources, especially human resources. The successful management of disasters using SM is significantly influenced by the availability of human resources. In a survey of over 200 emergency managers, half of them reported not having made any use of SM, identifying a lack of staff as the key obstacle [

26]. The current study also evident that the lack of human resources to manage SM is one of the frequently cited challenges in the literature. Training and time are the two key concerns related to the lack of human resources within DM organisations [

47]. Initially, officials struggle with vast amounts of information due to lack of training [

27] [

45]. To comply, it requires the personnel to perform and expertise in communication tasks daily [

24]. Secondly, as per McCormick [

27], the staff does not have enough time to respond or receive information through SM during disasters, mainly due to the lack of staff and expertise. The volume of posts published by users also affects the time it takes officials to keep up with requests during a disaster [

47]. Therefore, a proper allocation of human resources is also vital. Following these circumstances, SM platforms are often seen as a secondary element instead of a formal institutional tool, challenging the potential use of SM in managing devastating disasters [

81].

Language challenges, as a result of linguistic differences of the users, can arise in several forms. The predominant form of challenge, in the context of SM, is communication among multilingual communities. Specifically, if the victim and the responder are from diverse language backgrounds, possible miscommunications are inevitable. Importantly, the lack of options available in languages, apart from English has prevented indigenous people from using SM platforms, during disasters [

19]. Even though, automated translation tools are provided by some SM platforms, their accuracy is questionable. Furthermore, the use of sub languages or slang within some demographic groups such as teenagers, can also act as a challenge when extracting disaster-related data [

21]. For example, abbreviations such as TC (Take Care) are not understood by all users. These challenges may not only impede the use of SM but also result in data from such groups being excluded from the analysis during the disaster.

4.2.3. Technology Related Challenges

This category refers to the challenges related to technological features that hinder the selection and utilisation of a social media platform by its users. It includes internet connectivity issues, the digital divide, and challenges in identifying and clearing bottlenecks. From a user perspective, internet connectivity problems and the digital divide are the primary challenges. Loss of internet connection, especially during disasters, poses significant challenges as it not only hinders victims' access to critical information but also limits the surveillance operations by humanitarian actors [

20]. For instance, in the Australian context, researchers have pointed out that the extensive use of SM for disaster communication is impeded by scarce internet in rural and remote Australia [

19]. The digital divide, which refers to the inaccessibility of internet services, yields similar consequences and impacts [

74]. It is primarily evident in the least developed countries, but marginalised populations in developed countries are also experiencing the same. Interestingly, for certain populations, the digital divide can also be a choice, as they decide not to engage with technology or refuse digital literacy [

47]. However, the digital divide is a significant challenge to the effective implementation of SM in DM, significantly impacting access to information, resource mobilisation, and social communication. Issues in the information flow of SM platforms (bottlenecks), resulting from technological issues such as algorithm limitations and capacity problems, also remain problematic for its use in DM.

4.2.4. Legal Challenges

The final category of challenges to the effective use of SM in DM is legal challenges. Based on legal considerations, policy breaches and privacy violations, are classified under this category. Policy breaches and privacy rights violations, often visible in SM platforms, prevent the continuous use of SM in DM as a safe and potential tool. These violations include policy breaches imposed by SM platforms (ex: non-offensive comments policy) [

30]. Sharing misleading information, offensive responses and comments, and disclosure of confidential data of an organisation or an individual, are frequently common in SM platforms. However, there is no regulatory authority of SM for DM to prevent such violations and assure the privacy rights of the individuals [

11]. Therefore, the establishment and frequent monitoring of regulatory authorities, specifically for SM use in DM is required.

4.3. Stratergies to Overcome the Challenges for Using SM in DM

A total of 15 strategies to overcome challenges, were identified following the process of systematic literature review. The strategies were ranked based on the frequency of their mentions in the analysed papers. The results are presented in

Table 5 along with their references and corresponding ranks. Subsequently, the strategies were categorised into three main categories for clear and simple representation, namely: organisations, social media companies and individuals. The strategies were thoughtfully distributed among these three sectors of the SM community that could contribute to improving SM use in DM. Lam et al. [

8] followed a similar classification to categorise strategies related to improving SM use in disaster resilience. Proposed strategies for each of the three sectors are outlined in

Table 6. As evident in the

Table 6, the number of strategies for organisations and social media companies is comparatively higher than for individuals. This highlights the crucial role that organisations and SM companies can play in overcoming the challenges associated with SM use for DM. Both of these sectors possess substantial ability to reform the prevailing conditions within the subject area if needed. A detailed discussion of the strategies, classified under each community sector, is presented in the subsequent sections.

4.3.1. Organisations

The first set of strategies to overcome the challenges of SM use is organisations-related strategies. This includes all government and non-government organisations and agencies in the context of DM. As discussed previously, SM platforms are not yet considered a formal tool by officials to rely during disasters. Instead, SM platforms have been kept as a side tool. Therefore, strategies like comprehensive policy developments, the establishment of SM use guidelines, and the integration of SM with incident management systems can play a pivotal role in formalising SM use. For this to be possible, a broad policy framework is required that addresses user behavior, information confidentiality, integrity, and availability when accessing data or distributing government information [

27]. SM use guidelines, on the other hand, should address the best practices in emergencies that are valid across organisations to enable the inter-organisational overcoming of emergencies [

21]. Additionally, integrating SM with existing incident management systems will enhance the useability of SM as a formal tool to manage disasters [

8,

26]. Particularly, public safety answering points (PSAP) and emergency response systems (e.g., wired 911 emergency response system) are required to integrate with available SM platforms. Such integrations are already seen in some areas. For instance, an adaptable PSAP system, named Next Generation 911, is already being used in some parts of the United States [

8].

The study also suggests that raising awareness of the official accounts, which serve as a source of true information, would reduce the chance of misinformation and disinformation [

8]. Proactive engagement with the community, open and honest communication, delivery of consistent, factual and official information will further increase public trust in official accounts [

8], [

30]. Also, the formalised adoption and implementation of SM within the DM organisation requires new approaches, such as collaboration and partnerships. Establishing partnerships with private sector agencies, volunteer agencies, and more experienced agencies, as well as publishing policies to maintain consistency, can aid the formalised adoption and implementation of SM within the DM organisation [

47]. Another important strategy to overcome challenges related to SM in DM is revolutionising crisis intervention skills for digital environments. Traditional crisis intervention, which aims to assist victims and prevent serious long-term problems, is not sufficient to secure satisfactory results in the digital environment [

40]. Therefore, instead of using traditional methods like face-to-face emotional support, a hybrid mode of service, combining e-services with traditional methods, would be a great initiative. Finally, SM platforms can partner with relevant service providers to support this combination.

4.3.2. Individuals

Effective use of SM features by individuals greatly helps to overcome challenges related to SM use in DM. Starting with a fundamental set of features, SM platforms have undergone significant enhancements to fulfil the growing needs of users. For instance, real-time geotagging features, hashtags, and multimedia content integration in messages, provided by several SM platforms, help identify affected areas and locations immediately. However, despite the availability of such practical features, individual usage of these features is still low, which can be increased by their contributions. A survey conducted by Lam et al. [

8] to understand the individual use of SM during disasters, revealed that only 25% of respondents used hashtags (e.g., #hurricaneharveyrescue) for rescue requests. Moreover, geo-tagging enables users to share their location in real time, increasing the reliability of the content. Hashtags, on the other hand, improve the discoverability of the content while multimedia (images, videos and alike) provide the community with a comprehensive and dynamic representation of the situation. Thus, strategic use of these features by individuals can contribute to overcoming challenges such as poor information quality and the spread of misinformation, analysed in section 4.2.

4.3.3. Social Media Companies

The final set of strategies outlines the implementations related to SM companies. The key strategies include in this sector are developing methods to verify SM Information, implementing rapid and automated data mining and visualisation tools, and protection of data privacy of individuals. First and foremost, SM data verification has been a significant problem for every sector of the SM community. Therefore, development of compatible methods to verify information, disseminated through SM is an urgent need, especially during disasters [

28,

44]. Not only verification but an effective management of myths and misinformation is also required [

31]. For instance, assigning a label and warning to the posts that are false or potentially false could help eliminate the impacts of false news in a disaster event [

8]. SM companies can collectively work with other companies, researchers, and industry practitioners to seek advice and explore possibilities. However, improving methods to detect false news, validate reliability, and manage misinformation by SM companies are urgently needed. Secondly, manual searching, reading, and processing large amounts of data require intensive human resources and time, in the context of DM. On a positive note, rapid and automated data mining and visualisation systems enable the ability to deal with vast amounts of information, without the need for intensive human resources [

18]. Hence, SM companies can significantly reduce the problems of information overload and lack of human resources, by employing these systems. Finally, strict, and improved regulations, and actions to protect the data privacy of victims (e.g.: prevention of disclosure of sensitive data of victims) are also required by SM companies to enhance the effective utilisation of SM in DM [

49].

4.4. Conceptual Model

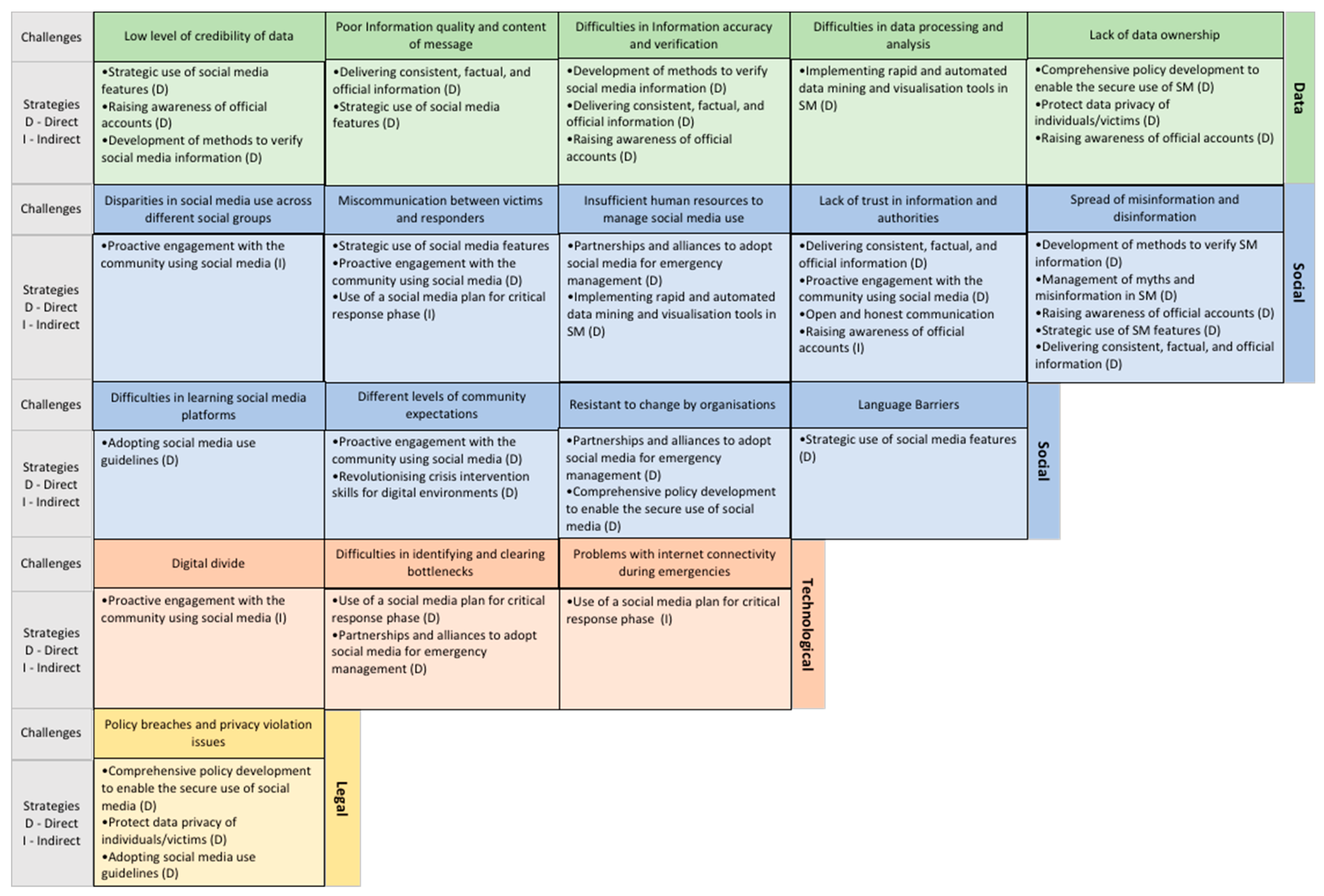

Identified challenges and strategies were mapped together to determine which barriers are addressed by existing strategies. Challenges were conceptualized together with the strategies that help overcome them. As some strategies can contribute to resolving more than one challenge, they were allocated to each challenge separately to enhance accuracy and reduce complexity in the conceptual model. Direct (D) and indirect (I) strategies were determined based on the main focus of challenges and strategies. Subsequently, the identified strategies are presented under each challenge by compiling findings from the literature review, as depicted in

Figure 7.

As shown in

Figure 7, some strategies directly contribute to overcoming challenges in each category. For instance, the challenge of 'difficulties in information accuracy and verification' can be directly addressed by developing methods to verify social media information. However, some strategies only have indirect or partial contributions to overcoming particular challenges. For example, proactive engagement with the community using social media will only reach part of the digitally divided population. The digital divide refers to the inaccessibility of internet services in some areas but can also be a choice made by some individuals who decide not to engage with technology or refuse digital literacy, as discussed in the section 4.2.3. The strategy of 'proactive engagement with the community using social media' is only relevant to such individuals, leaving fully inaccessible people with no direct strategy. Similar consequences can be observed with the challenge of 'disparities in social media use across different social groups'. Furthermore, the use of social media plans in the critical response phase is only relevant to alternative actions that officials and authorities can take. Emergency managers can plan alternative or traditional methods of communication if there are connectivity problems during emergencies. Yet, the original challenge remains unsolved or partially solved. It was observed that, out of all the proposed 15 strategies, none of them directly address the issues of social and geographical disparities, digital divide, and internet connectivity problems during emergencies as evident in the developed conceptual model. Therefore, it is suggested that future research should prioritise exploring and providing prictical strategies/solutions to overome these challenges. Conversly, the most prominent challenges identified include the spread of misinformation and disinformation, insufficient human resources to manage social media use, lack of trust in information and authorities, and poor information quality. These challenges have a considerable number of direct strategies to overcome them, indicating the satisfactory level of attention given in previous studies to highly cited challenges. Implementing these strategies in the context of DM requires combined contributions from organisations, individuals, and SM companies.

5. Conclusions

The study reported findings from a systematic literature review that aimed to identify key challenges and possible strategies for the use of SM in DM. The review included 72 papers from journals and conferences written in English and published before November 2023. The findings suggest that researchers are increasingly becoming interested in using SM as a DM tool. Scholars from countries such as the United States, Australia, Germany, and the United Kingdom made a significant contribution to the literature on the use of SM in DM. Overall, Twitter was the predominant SM platform used in DM, appearing in 55% of the papers, followed by Facebook at 24%. SM was used to manage a wide range of disasters, but the most significant disasters that appeared in the literature were hurricanes (25%), pandemics (16%), floods (15%), earthquakes (13%), and bushfires (11%). The content review of the papers identified 18 challenges to SM use in DM, classified and integrated into a classification under four categories: data, technology, social and legal. The ways in which these challenges could be overcome were discussed later in the study concerning three community sectors: organisations, individuals, and SM companies. A total of 15 strategies were discovered and a conceptual model has also been developed in the study.

The conceptual model provides a readily available point of reference for both the challenges and strategies to the use of SM in DM. This aids in encouraging industry practitioners to understand the prevailing challenges and direct the strategies towards the optimal use of SM. In addition, this study broadens the current knowledge on SM use in DM, associated with challenges and strategies that are essential for the successful utilisation of SM into DM context. Finally, the findings of the study serve as a valuable reference for both scholars and professionals who want to further explore SM use in DM practices and procedures.

In facilitating the insufficiently explored area of SM use in DM, this study suggests an empirical verification of the theoretical challenges and strategies. More specifically, most of the challenges and strategies were grounded in the views of researchers, which requires more verification in the form of empirical studies such as case studies. Therefore, future researchers are recommended to conduct such studies to further ensure the usability between the challenges and strategies presented in the study. Furthermore, it was noticed that the current research landscape is more dominant in developed countries such as the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom. Conversely, developing, and disaster-prone countries such as Bangladesh and Philippines are noticeably absent in the reviewed literature. Therefore, future research should explore the challenges and possible strategies to the use of SM in DM, across wider nations and cultures, to be more literate within the research focus. A unique set of challenges and strategies may be discovered from such studies, broadening the current state of art within the context. In addition, the use of SM in different socio-demographic groups in DM is under-researched within the literature. Instead, more generic attention has been given to the social communities. In the context of challenges and strategies, it is crucial to examine different socio-demographic groups such as low socioeconomic status people, old/ isolated people, minor populations, and people with disabilities, as they may face unique sets of challenges based on their conditions, and therefore it requires special type of strategies to overcome them.

Despite the significant contributions, the authors acknowledge the limitations of the study. Only two prominent databases were employed in the study to conduct the systematic literature review. As a result, the study might not refer to all the available literature in the research focus. Still, it is impossible to consider all the publications within a single review. Further, researchers also acknowledge the possible subjective judgments on selecting the most pertinent papers. Even though the authors used some strategies to minimise the possible individual bias such as regular discussions, full exclusion of such subjective judgments is not possible. However, significant contributions made by this study to the contexts of SM and DM are inevitable, as the study is one of the evolving studies to present a categorised set of challenges and strategies for the use of SM in DM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S., M.N., S.S. and S.P.; methodology, K.S., M.N., S.S. and S.P.; software, M.N.; formal analysis, K.S. and M.N.; investigation, K.S. and M.N.; resources, K.S.; data curation, M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S. and M.N.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and S.P.; visualization, K.S. and M.N.; supervision, S.S. and S.P..; funding acquisition, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ogie, R.I., et al., Crowdsourced social media data for disaster management: Lessons from the PetaJakarta.org project. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 2019. 73: p. 108-117. [CrossRef]

- The Emergency Events Database. 2024, Universit´e catholique de Louvain (UCL): Brussels, Belgium.

- Ogie, R.; James, S.; Moore, A.; Dilworth, T.; Amirghasemi, M.; Whittaker, J. Social media use in disaster recovery: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 70, . [CrossRef]

- Acikara, T.; Xia, B.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Hon, C. Contribution of Social Media Analytics to Disaster Response Effectiveness: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8860, . [CrossRef]

- Jamali, M., et al., Social media data and post-disaster recovery. International Journal of Information Management, 2019. 44: p. 25-37. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Regona, M.; Kankanamge, N.; Mehmood, R.; D’costa, J.; Lindsay, S.; Nelson, S.; Brhane, A. Detecting Natural Hazard-Related Disaster Impacts with Social Media Analytics: The Case of Australian States and Territories. Sustainability 2022, 14, 810, . [CrossRef]

- Mukkamala, A. and R. Beck. Social media for disaster situations: Methods, opportunities and challenges. in GHTC 2017 - IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference, Proceedings. 2017. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.

- Lam, N.S.N.; Meyer, M.; Reams, M.; Yang, S.; Lee, K.; Zou, L.; Mihunov, V.; Wang, K.; Kirby, R.; Cai, H. Improving social media use for disaster resilience: challenges and strategies. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 3023–3044, . [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, T.; Ngamassi, L.; Rahman, S. Examining the Factors that Influence the Use of Social Media for Disaster Management by Underserved Communities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2022, 13, 52–65, . [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, R.T.; McPhearson, T. Social-media data for urban sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 553–565, . [CrossRef]

- Singla, A.; Agrawal, R. Social media and disaster management: investigating challenges and enablers. Glob. Knowledge, Mem. Commun. 2022, 73, 100–122, . [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Mengersen, K.; Bennett, S.; Mazerolle, L. Viewing systematic reviews and meta-analysis in social research through different lenses. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 511, . [CrossRef]

- Wafa, W.; Sharaai, A.H.; Matthew, N.K.; Ho, S.A.J.; Akhundzada, N.A. Organizational Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (OLCSA) for a Higher Education Institution as an Organization: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2616, . [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, C., et al., PRISMA 2020 statement: What's new and the importance of reporting guidelines. Int J Surg, 2021. 88: p. 105918. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339, . [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zuo, J.; Wu, G.; Huang, C. A bibliometric review of green building research 2000–2016. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2019, 62, 74–88, doi:10.1080/00038628.2018.1485548.

- Van Wyk, H., et al., Searching for signal and borrowing wi-fi: Understanding disaster-related adaptations to telecommunications disruptions through social media. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 2023. 86. [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Liao, D.; Lam, N.S.; Meyer, M.A.; Gharaibeh, N.G.; Cai, H.; Zhou, B.; Li, D. Social media for emergency rescue: An analysis of rescue requests on Twitter during Hurricane Harvey. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 85, . [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.K.; Sibarani, R.; Lassa, J.; Nguyen, D.; Dimmock, A. How do Australians use social media during natural hazards? A survey. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 81, . [CrossRef]

- Bonati, S.; Nardini, O.; Boersma, K.; Clark, N. Unravelling dynamics of vulnerability and social media use on displaced minors in the aftermath of Italian earthquakes. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 89, . [CrossRef]

- Anson, S.; Watson, H.; Wadhwa, K.; Metz, K. Analysing social media data for disaster preparedness: Understanding the opportunities and barriers faced by humanitarian actors. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 21, 131–139, . [CrossRef]

- Velivela, V., et al. The Effectiveness of Social Media Engagement Strategy on Disaster Fundraising. in Proceedings of the International ISCRAM Conference. 2022. Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, ISCRAM.

- van Wyk, H. and K. Starbird. Analyzing social media data to understand how disaster-affected individuals adapt to disaster-related telecommunications disruptions. in Proceedings of the International ISCRAM Conference. 2020. Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, ISCRAM.

- Kaufhold, M.A. and C. Reuter. The impact of social media for emergency services: A case study with the fire department Frankfurt. in Proceedings of the International ISCRAM Conference. 2017. Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, ISCRAM.

- Peterson, S., C. Thompson, and C. Graham. Getting disaster data right: A call for real-time research in disaster response. in Proceedings of the International ISCRAM Conference. 2018. Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, ISCRAM.

- Grace, R., J. Kropczynski, and A. Tapia. Community coordination: Aligning social media use in community emergency management. in Proceedings of the International ISCRAM Conference. 2018. Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, ISCRAM.

- McCormick, S. New tools for emergency managers: an assessment of obstacles to use and implementation. Disasters 2016, 40, 207–225, . [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.M.; Bruns, A.; Newton, J. Trust, but verify: social media models for disaster management. Disasters 2017, 41, 549–565, . [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q., et al., Dynamics of Interorganizational Emergency Communication on Twitter: The Case of Hurricane Irma. Disasters, 2022.

- Stovall, W.K.; Ball, J.L.; Westby, E.G.; Poland, M.P.; Wilkins, A.; Mulliken, K.M. Officially social: Developing a social media crisis communication strategy for USGS Volcanoes during the 2018 Kīlauea eruption. Front. Commun. 2023, 8, . [CrossRef]

- Tabong, P.T.-N.; Segtub, M. Misconceptions, Misinformation and Politics of COVID-19 on Social Media: A Multi-Level Analysis in Ghana. Front. Commun. 2021, 6, . [CrossRef]

- Paton, D.; Irons, M. Communication, Sense of Community, and Disaster Recovery: A Facebook Case Study. Front. Commun. 2016, 1, . [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, A.; Bunker, D.; Levine, L.; Sleigh, A. Emergency management in the changing world of social media: Framing the research agenda with the stakeholders through engaged scholarship. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 112–120, . [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.C.; Hasan, S.; Sadri, A.M.; Cebrian, M. Understanding the efficiency of social media based crisis communication during hurricane Sandy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102060, . [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hastak, M. Social network analysis: Characteristics of online social networks after a disaster. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 38, 86–96, . [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Pinto, J.; Zhong, B. Building community resilience on social media to help recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 134, 107294–107294, . [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, H.; Platt, L.S. Examining risk and crisis communications of government agencies and stakeholders during early-stages of COVID-19 on Twitter. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 114, 106568–106568, . [CrossRef]

- Keim, M.K.; Noji, E. Emergent use of social media: A new age of opportunity for disaster resilience. Am. J. Disaster Med. 2011, 6, 47–54, . [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Lam, N.S.N.; Cai, H.; Qiang, Y. Mining Twitter Data for Improved Understanding of Disaster Resilience. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2018, 108, 1422–1441, . [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.H.C. and C.T. Zhou, Practice Update – Social-psychological emergency response during Wuhan lockdown: Internet-based crisis intervention. Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, 2022. 26(Special Issue): p. 159-165.

- Cooper, V.; Hayes, P.; Karanasios, S. Building Social Resilience and Inclusion in Disasters: A Survey of Vulnerable Persons' Social Media Use. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2022, 26, . [CrossRef]

- Dufty, N., Using social media to build community disaster resilience. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 2012. 27(1): p. 40-45.

- Kent, J.D.; Capello, H.T., Jr. Spatial patterns and demographic indicators of effective social media content during theHorsethief Canyon fire of 2012. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 40, 78–89, doi:10.1080/15230406.2013.776727.

- Tapia, A.H.; Moore, K. Good Enough is Good Enough: Overcoming Disaster Response Organizations’ Slow Social Media Data Adoption. Comput. Support. Cooperative Work. (CSCW) 2014, 23, 483–512, . [CrossRef]

- Tagliacozzo, S.; Magni, M. Government to Citizens (G2C) communication and use of social media in the post-disaster reconstruction phase. Environ. Hazards 2018, 17, 1–20, . [CrossRef]

- Todesco, M.; De Lucia, M.; Bagnato, E.; Behncke, B.; Bonforte, A.; De Astis, G.; Giammanco, S.; Grassa, F.; Neri, M.; Scarlato, P.; et al. Eruptions and Social Media: Communication and Public Outreach About Volcanoes and Volcanic Activity in Italy. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, . [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Johnson, P. Challenges in the adoption of crisis crowdsourcing and social media in Canadian emergency management. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 501–509, . [CrossRef]

- Khusna, N.I., et al., Social resilience and disaster resilience: A strategy in disaster management efforts based on big data analysis in Indonesian's twitter users. Heliyon, 2023. 9(9).

- Adam, N.R.; Shafiq, B.; Staffin, R. Spatial Computing and Social Media in the Context of Disaster Management. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2012, 27, 90–96, . [CrossRef]

- Poblete, B.; Guzman, J.; Maldonado, J.; Tobar, F. Robust Detection of Extreme Events Using Twitter: Worldwide Earthquake Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Multimedia 2018, 20, 2551–2561, . [CrossRef]

- Silver, A.; Matthews, L. The use of Facebook for information seeking, decision support, and self-organization following a significant disaster. Information, Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 1680–1697, . [CrossRef]

- Abedin, B.; Babar, A. Institutional vs. Non-institutional use of Social Media during Emergency Response: A Case of Twitter in 2014 Australian Bush Fire. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 729–740, . [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Yoo, E.; Yan, L.(.; Pedraza-Martinez, A. Speak with One Voice? Examining Content Coordination and Social Media Engagement During Disasters. Inf. Syst. Res. 2023, . [CrossRef]

- Mauroner, O.; Heudorfer, A. Social media in disaster management: How social media impact the work of volunteer groups and aid organisations in disaster preparation and response. Int. J. Emerg. Manag. 2016, 12, 196, . [CrossRef]

- Kim, K., K. Jung, and K. Chilton, Strategies of social media use in disaster management: Lessons in resilience from Seoul, South Korea. International Journal of Emergency Services, 2016. 5(2): p. 110-125.

- Laylavi, F.; Rajabifard, A.; Kalantari, M. A Multi-Element Approach to Location Inference of Twitter: A Case for Emergency Response. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 2016, 5, 56, . [CrossRef]

- Maldeniya, D.; De Choudhury, M.; Garcia, D.; Romero, D.M. Pulling through together: social media response trajectories in disaster-stricken communities. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 2023, 6, 655–706, . [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Jiang, Y.; Mostafavi, &.A. The Role of Local Influential Users in Spread of Situational Crisis Information. J. Comput. Commun. 2021, 26, 108–127, . [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Hanashima, M.; Sano, H.; Ikeda, M.; Handa, N.; Taguchi, H.; Usuda, Y. An Attempt to Grasp the Disaster Situation of “The 2018 Hokkaido Eastern Iburi Earthquake” Using SNS Information. J. Disaster Res. 2019, 14, 1170–1184, . [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; He, W.; He, Y.; Albert, S.; Howard, M. Using health belief model and social media analytics to develop insights from hospital-generated twitter messaging and community responses on the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2023, 36, 1483–1507, . [CrossRef]

- Gurman, T.A.; Ellenberger, N. Reaching the Global Community During Disasters: Findings From a Content Analysis of the Organizational Use of Twitter After the 2010 Haiti Earthquake. J. Heal. Commun. 2015, 20, 687–696, . [CrossRef]

- Bec, A.; Becken, S. Risk perceptions and emotional stability in response to Cyclone Debbie: an analysis of Twitter data. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 721–739, . [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, M.; Bunker, D.; Sorrell, T.C. Communicating shared situational awareness in times of chaos: Social media and theCOVID-19 pandemic. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 74, 1185–1202, . [CrossRef]

- Leong, C.; National University of Singapore; Pan, S.; Ractham, P.; Kaewkitipong, L.; University of New South Wales; Thammasat University ICT-Enabled Community Empowerment in Crisis Response: Social Media in Thailand Flooding 2011. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 16, 174–212, . [CrossRef]

- Akbar, G.G.; Kurniadi, D.; Nurliawati, N. Content Analysis of Social Media: Public and Government Response to COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia. J. Ilmu Sos. dan Ilmu Politi- 2021, 25, 16–31, . [CrossRef]

- Tagliacozzo, S.; Magni, M. Communicating with communities (CwC) during post-disaster reconstruction: an initial analysis. Nat. Hazards 2016, 84, 2225–2242, . [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E.C.; Takahashi, B. Log in if you survived: Collective coping on social media in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. New Media Soc. 2016, 19, 1778–1793, . [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Deng, Y.; Yang, W.; Li, B. "Help! Can You Hear Me?": Understanding How Help-Seeking Posts are Overwhelmed on Social Media during a Natural Disaster. Proc. ACM Human-Computer Interact. 2022, 6, 1–25, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lai, C.-H.; Xu, W.(. Tweeting about emergency: A semantic network analysis of government organizations’ social media messaging during Hurricane Harvey. Public Relations Rev. 2018, 44, 807–819, . [CrossRef]

- Wukich, C. Preparing for Disaster: Social Media Use for Household, Organizational, and Community Preparedness. Risk, Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2019, 10, 233–260, . [CrossRef]

- Hagen, L., et al., Crisis Communications in the Age of Social Media: A Network Analysis of Zika-Related Tweets. Social Science Computer Review, 2018. 36(5): p. 523-541. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Haunert, J.; Knechtel, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, Q.; Dehbi, Y. Social media insights on public perception and sentiment during and after disasters: The European floods in 2021 as a case study. Trans. GIS 2023, 27, 1766–1793, . [CrossRef]

- Al Momin, K.; Kays, H.M.I.; Sadri, A.M. Identifying Crisis Response Communities in Online Social Networks for Compound Disasters: The Case of Hurricane Laura and COVID-19. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2023, . [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.T.; Mueller, J.L.; Jones, M.L. Use of Social Media During Public Emergencies by People with Disabilities. WestJEM 21.2 March Issue 2014, 15, 567–574, . [CrossRef]

- Nagahawatta, R., et al. Strategic Use of Social Media in COVID-19 Pandemic. Pandemic Management by Sri Lankan Leaders and Health Organisations Using the CERC Model. in ACIS 2022 - Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Proceedings. 2022. Association for Information Systems.

- Fan, C., Y. Jiang, and A. Mostafavi. Seeding Strategies in Online Social Networks for Improving Information Dissemination of Built Environment Disruptions in Disasters. in Computing in Civil Engineering 2019: Data, Sensing, and Analytics - Selected Papers from the ASCE International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering 2019. 2019. American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).

- Reuter, C., et al. XHELP: Design of a cross-platform social-media application to support volunteermoderators in disasters. in Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings. 2015. Association for Computing Machinery.

- Ahmed, M.A., et al. Social Media Communication Patterns of Construction Industry in Major Disasters. in Construction Research Congress 2020: Computer Applications - Selected Papers from the Construction Research Congress 2020. 2020. American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).

- Salsabilla, F.P.; Hizbaron, D.R. Understanding Community Collective Behaviour Through Social Media Responses: Case of Sunda Strait Tsunami, 2018, Indonesia. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 325, 01021, . [CrossRef]

- Purohit, H., et al. With whom to coordinate, why and how in ad-hoc social media communities during crisis response. in ISCRAM 2014 Conference Proceedings - 11th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management. 2014. The Pennsylvania State University.

- Zhang, Y., et al. Fostering community resilience through adaptive learning in a social media age: Municipal twitter use in New Jersey following Hurricane Sandy. in ISCRAM 2015 Conference Proceedings - 12th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management. 2015. Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, ISCRAM.

- Jayathilaka, H.A.D.G.S., et al. Investigating the Variables that Influence the Use of Social Media for Disaster Risk Communication in Sri Lanka. in Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering. 2022. Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH.

- Nalluru, G., R. Pandey, and H. Purohit. Relevancy classification of multimodal social media streams for emergency services. in Proceedings - 2019 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing, SMARTCOMP 2019. 2019. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.

- Lee, K.S. Explicit disaster response features in social media: Safety check and community help usage on facebook during typhoon Mangkhut. in Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, MobileHCI 2019. 2019. Association for Computing Machinery, Inc.

- Tha, K.K.O., S.L. Pan, and L.M.S. Sandeep. Exploring Social media affordances in natural disaster: Case study of 2015 myanmar flood. in Proceedings of the 28th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, ACIS 2017. 2017. Formal Power Series and Algebraic Combinatorics.

- Dailey, D. and K. Starbird. Social media seamsters: Stitching platforms & audiences into local crisis infrastructure. in Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW. 2017. Association for Computing Machinery.

- De-Graft, J.O., et al., Barriers to the Adoption of Digital Twin in the Construction Industry: A Literature Review. Informatics, 2023. 10(1): p. 14. [CrossRef]

- Fatma, N.; Haleem, A. Exploring the Nexus of Eco-Innovation and Sustainable Development: A Bibliometric Review and Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12281, . [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E.D.R.S.; Kandpal, V.; Machado, M.; Martens, M.L.; Majumdar, S. A Bibliometric Analysis of Circular Economies through Sustainable Smart Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15892, . [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A. Social media in disaster management: review of the literature and future trends through bibliometric analysis. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 953–975, . [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Shahzad, K.; Shabbir, O.; Iqbal, A. Developing a Framework for Fake News Diffusion Control (FNDC) on Digital Media (DM): A Systematic Review 2010–2022. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15287, . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).