1. Introduction

As industrialization and urbanization advance rapidly, the quality of life for residents has significantly improved. Urban residents’ growing interest in rural tourism has been noted (Cronin & Evans, 2020). Due to its advantages, such as low cost, high safety, and low population density, rural tourism is poised to become the preferred choice for urban dwellers seeking leisure and vacation experiences (An & Alarcon, 2020). However, the influx of many urban residents has led to explosive growth in rural tourism, triggering numerous environmental issues (Grilli & Curtis, 2021). The rural ecological environment is confronted with challenges such as emissions from private vehicle exhaust, littering, uncontrolled fires during picnics, environmentally unfriendly wastewater treatment resulting from agricultural and processing activities, and non-native rural landscape construction (Kalthaus & Sun, 2021).

In the past decade, an increasing number of scholars have shifted their focus toward environmental issues, and concurrently, a growing body of literature has delved into the investigation of pro-environmental behaviors (Lange & Dewitte, 2019). Previous research has traditionally regarded tourists’ environmentally friendly behaviors as critical for mitigating overdevelopment in the tourism industry and addressing inappropriate tourist conduct (Lange, 2023; Lange & Dewitte, 2019). However, little literature is carried out on the relationship between tourism nostalgia and pro-environmental behaviors that must be addressed. Routledge argues that nostalgia positively influences pro-environmental behaviors in tourism, with leisure engagement and place attachment serving as mediating factors (Howell et al., 2019; Routledge et al., 2012; Shin & Jeong, 2022). Nostalgia emotions impact environmental conservation behaviors in heritage tourism, where subjective attitudes, perceptions, behavioral control, subjective norms, and existential meaning act as mediating factors. Nostalgia positively influences pro-environmental behaviors in historical and cultural areas, with perceived value and a sense of awe serving as mediating factors (Tsai et al., 2020; Wang & Chao, 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

Prior research on pro-environmental behavior has predominantly focused on individual psychological factors. However, these psychological factors are often overlooked in predicting actual pro-environmental behaviors. When examining the mechanisms influencing pro-environmental behaviors, individuals’ social behaviors and cognitions may change significantly due to major external environmental events such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Doherty, 2022) It has been observed that people’s behaviors vary significantly in different contexts (Contreras-Contreras et al., 2023). However, consideration has yet to be given to the factors influencing the psychological and cognitive changes among urban residents in the post-pandemic era. Therefore, it is imperative to understand further how psychological factors influence tourists’ cognitive responses and pro-environmental behaviors (Chirico et al., 2023; Ertz et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2016; Thabet et al., 2023).

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Tourism Nostalgia and Pro-Environmental Behavior

Nostalgia is a commonly observed phenomenon in people’s daily lives, triggered by factors such as valuable scenes or meaningful events. Nostalgia emotions serve essential psychological functions as positive, self-relevant, and social emotions (Yuriev et al., 2018; Zhou & Wang, 2022). Nostalgia is a psychological variable that stimulates emotion and cognition; it can elicit positive actions or behavioral tendencies and enhance social connections, promoting social interactions (Wu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). Tourism activities and destinations often serve as intrinsic sources of nostalgia. In the field of tourism studies, Tourism Nostalgia is considered a ‘journey home.’ Christie et al. (Tang et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2020). conducted an in-depth investigation into nostalgia beyond mere ‘memory recall,’ recognizing a dynamic relationship between tourism and nostalgia. Thus, tourism can be a significant trigger and container for nostalgia, while nostalgia can constitute a crucial experiential element or motivation in tourism. However, nostalgia has multiple meanings across various disciplines, encompassing emotions, cognition, personality, behavior, and social phenomena (Howell et al., 2019; Routledge et al., 2012; Shin & Jeong, 2022).

Pro-environmental behavior primarily refers to actions taken at the individual or household level that are beneficial to the environment or aim to minimize negative impacts. Yusliza starting from personal responsibility and values, define conscious actions by humans to avoid or address environmental problems as pro-environmental behavior (Yusliza et al., 2020). Consider individual or organizational behaviors that involve sustainable and restrained development and utilization of natural resources as pro-environmental behavior (Yuriev et al., 2018). Pro-environmental behavior as actions that result in fewer negative impacts on the environment, such as turning off lights and recycling energy (Ajibade et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2020; Wu & Geng, 2020). Participating in green activities promoting sustainable development and reducing or eliminating negative environmental impacts as pro-environmental behavior (Jiang et al., 2023; Lin & Wu, 2018; Liu et al., 2021). Therefore, the hypothesis is as follows:

H1a: Tourism nostalgia positively contributes to the environmental responsibility.

H1b: Tourism nostalgia positively contributes to awe.

H1c: Tourism nostalgia positively contributes to pro-environmental behavior.

2.2. The Mediating Effect of Environmental Responsibility

Environmental responsibility is individuals’ sense of duty when facing environmental issues, representing their cognitive awareness of the responsibility for maintaining the overall environment (Yang et al., 2015; Yue et al., 2020). This sense of responsibility can guide individuals to adopt a more proactive stance towards environmental issues, believing in their capacity to effect change and being more willing to address environmental problems (Vives, 2022) actively. There is a strong correlation between environmental responsibility and individuals’ environmental conservation behaviors (Kim & Statman, 2012; Li et al., 2020). Individuals with heightened environmental responsibility are more inclined to take measures beneficial to environmental management (Sharpe et al., 2022; Vives, 2022; Yang et al., 2021).

When addressing environmental issues, individuals often incur costs such as time and money, potentially placing them in a dilemma between personal and societal interests (Straßer et al., 2022). In such situations, intrinsic environmental responsibility is activated, compelling individuals to engage in behaviors conducive to the environment (Severo et al., 2021). The willingness to participate in societal practices that promote energy conservation, emission reduction, and environmental protection becomes a benchmark for assessing the strength of individuals’ social responsibility awareness (Islam, 2008).Therefore, the following hypotheses are posited:

H2a Environmental responsibility positively promotes pro-environmental behavior.

H2b Environmental responsibility positively promotes awe.

H2c Environmental responsibility acts as a mediator in the relationship between tourism nostalgia and pro-environmental behavior.

2.3. The Mediating Effect of Awe

Awe refers to the experience individuals undergo when facing vast phenomena, where they perceive their own insignificance and gain insights into self-cognition and their relationships with others and the environment (Guo et al., 2021). Awe enhances the sense of connection with others or the surrounding environment, instigates positive emotions of self-transcendence. And encourages individuals to be more attentive to environmental changes, contributing to increased pro-environmental behavior (Chirico et al., 2023). Extensive literature has investigated the sense of grandiosity induced by awe, using the variable of ‘diminished self’ to explore how the sense of insignificance triggered by awe further influences pro-environmental behavior (Biresselioglu et al., 2018; Kaplan et al., 2023).

Meanwhile, Awe has separately examined changes in the self-other relationship component such as the positive correlation between people’s awe of nature and perceived connection with others and the positive correlation with individual life satisfaction (Kaplan et al., 2016). Awe emotion effectively expands the self-concept, and when the natural environment becomes integrated into an individual’s self-concept, it stimulates pro-environmental behavior (Lashari et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022). Tourists engaging in “individual-environment” interactions in rural areas find that awe can enhance self-identity and a sense of belonging, reduce anxiety, and influence self-efficacy (Lin & Wu, 2018; Liu et al., 2021; Yusliza et al., 2020).Therefore, the hypothesis is as follows:

H3: Awe Positively Promotes Pro-Environmental Behavior

H3:Awe Mediates the Relationship Between Tourism Nostalgia and Pro-Environmental Behavior

2.4. Chain-Mediated Effects of Environmental Responsibility and Awe

Social cognitive theory posits that individual cognition, behavior, environment, and interactions collectively influence behavior (Chiu et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2020). It asserts that human behavior is a form of cognition about oneself and the surrounding environment. Human environmental cognition can manifest as awe and environmental responsibility in this context. Consumer environmental responsibility determines how products’ value is perceived and directly influences consumer intent (Routledge et al., 2012). Routledge found that tourists with higher environmental responsibility are more likely to be aware of the impact of their actions on the environment, thus adopting behaviors favorable to the environment (Afsar & Umrani, 2020; Zhao et al., 2018).

Howell conducted research on the environmental quality of tourist attractions, revealing a significant positive role of self-efficacy and environmental responsibility in influencing attraction quality (Holtbrügge & Dögl, 2012; Kim & Statman, 2012). Furthermore, self-efficacy does not directly affect behavioral intent but rather achieves its impact through the influence of environmental responsibility on pro-environmental behavior. Therefore, environmental responsibility enhances tourists’ green perceived value in the pro-environmental domain, influencing their pro-environmental behaviors (Chwialkowska et al., 2020; Wu & Geng, 2020).Therefore, it is hypothesized as follow:

H4:Chain-Mediated Effects of Environmental Responsibility and Awe in the Relationship between Tourism Nostalgia and Pro-Environmental Behavior.

2.5. The Moderating Effect of Environmental Concern

Environmental concern refers to an individual’s degree of attention to the natural environment (Bakaki et al., 2019). Environmental concern represents a new way of thinking, related to anthropocentric altruism. People care about the environment primarily because they perceive environmental degradation as a threat to human health, and their foremost concern is the safety of their living environment, expressing self-interest (Benzidia et al., 2021; Bissing-Olson et al., 2013; Bockarjova & Steg, 2014). The deterioration of personal threats caused by the environment is a significant factor contributing to responsible environmental behavior (Zhang & Wen, 2008; Zhang et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2016). In analyzing the mechanism forming consumer green consumption behavior, Bamberg clarified the role mechanism of environmental knowledge in consumer green purchasing behavior through significance tests and the distinct impact of green cognition (Zhao et al., 2018; Zhou, 2022; Zhou & Wang, 2022).

Numerous studies indicate that tourism nostalgia significantly influences pro-environmental behavior through the moderating effect of environmental concern (He et al., 2021). Another prevalent perspective suggests that the relationship between tourism nostalgia and pro-environmental behavior is largely influenced by other mediating or moderating factors, such as environmental values, environmental concern, perceived behavioral control, perception of behavioral outcomes, personal experience, and habits (Golob et al., 2019; Koklic et al., 2019). Studies reveal that pro-environmental behavior is particularly influenced by psychological factors. From the perspective of pro-environmental behavior, emphasizing psychological cognition rather than cognitive appeals seems to more effectively promote consumers’ pro-environmental behavior (Díaz et al., 2020). It is evident that providing environmental information and emphasizing environmental concern play a crucial role in fostering environmental concern. Therefore, it is hypothesized as follow:

H5a The moderating effect of environmental concern between tourism nostalgia and pro-environmental behavior is significant.

H5b The moderating effect of environmental concern between environmental responsibility and pro-environmental behavior is significant.

H5c The moderating effect of environmental concern between awe and pro-environmental behavior is significant.

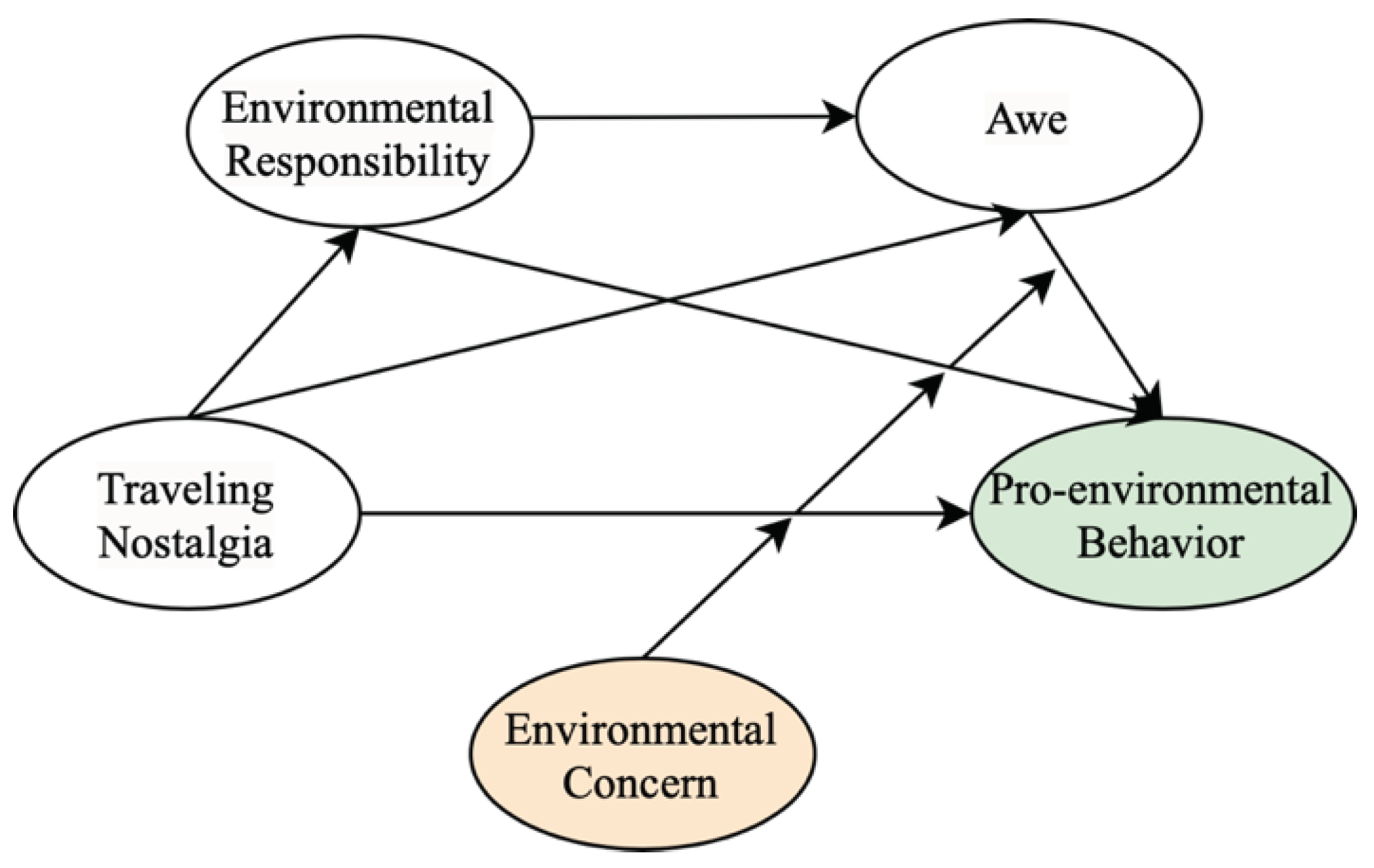

Based on the hypotheses above, the theoretical framework proposed in

Figure 1.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study selected urban tourists with rural tourism experiences as the research participants and employed a questionnaire survey method to collect data. The measurement scales were primarily adapted from well-established scales used by both domestic and foreign scholars, with modifications made to suit the rural tourism context. All items were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale. The questionnaire comprised six main sections:

The first section consisted of the Tourism Nostalgia Scale, adapted with reference to studies by McDonald et al. (McDonald et al., 2014). The second section included the Environmental Responsibility Scale, adapted with reference to studies by Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2019).The third section featured the Awe Scale, adapted with reference to studies by Yan & Jia (Yan & Jia, 2021).The fourth section involved the Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale, adapted with reference to scales developed by Lee et al. (Lee et al., 2015; White & Sintov, 2017).The fifth section contained the Environmental Concern Scale, adapted with reference to the scale constructed by He (He et al., 2018).The sixth section collected participants’ basic demographic information.The content and structure of the questionnaire were designed to suit the specific characteristics of rural tourism, ensuring its relevance and effectiveness in capturing the targeted constructs.

3.2. Data Collection and Sample Analysis

This study employed a sampling survey to distribute questionnaires, recognizing that the prerequisite for rural pro-environmental behavior is engaging in rural tourism. To ensure the reliability and validity of the measurement scales, a pre-survey was conducted by distributing 70 questionnaires offline. Of the 70 distributed questionnaires, 61 valid responses were collected, resulting in an effective response rate of 87.14%. The data were collected through self-administered questionnaires. All measurement scales underwent rigorous reliability and validity tests during the pre-survey, and based on these results, a formal questionnaire was developed.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Details

The primary data collection occurred in two waves. The first wave took place from August 1 to August 15, 2023, and the second wave from August 16 to September 1, 2023. The questionnaires were distributed online using the ‘Question Star’ platform, ensuring a diverse geographical representation of respondents from across the country. In total, 656 questionnaires were distributed, and 656 were collected. After screening, 535 questionnaires were deemed valid, resulting in an effective response rate of 82%. The demographic variables considered in this study included gender, age, education level, and average monthly income. Specific details regarding the sample structure are provided in

Table 1.

Table 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of the sample under investigation. Of the surveyed individuals, 258 were male, constituting 48.2% of the sample, while 277 were female, making up 51.8%. This indicates a slightly higher proportion of females among the respondents, but the overall gender distribution remains relatively balanced. In terms of age, the primary age groups among the surveyed individuals were 21-35 years and 36-45 years.

Regarding educational attainment, the majority held a bachelor’s degree, followed by those with education levels below college and a relatively lower number with postgraduate education. Concerning the frequency of annual travel, the majority of respondents (39.8%) reported traveling three times or less per year, with 213 individuals falling into this category. Additionally, 168 respondents (31.4%) reported traveling 4-8 times annually, 88 individuals (16.4%) reported traveling 9-15 times, and 66 individuals (12.3%) reported traveling 16 times or more each year. Thus, the majority of respondents reported traveling three times or less annually, followed by those who traveled 4-8 times.

4.2. Reliability and Validity

To ensure the reliability of the constructs used in the study, internal consistency reliability was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliabilities (see

Table 2). The values of composite reliability, for all variables are within the recommended range (0.70–0.90). The values of composite reliability for all variables remained within the lower bound Cronbach’s alpha and the upper bound composite reliability, confirming a higher level of internal consistency within the constructs.

The variance inflation factors (VIF) is determined to evaluate multicollinearities for all measurement items. All calculated VIF values are less than the suggested cut-off value (i.e., 5.0), confirming the absence of multicollinearity. Thus, there is no multi-collinearity problem. The discriminant validity (DV) of the model used in this study is estimated using Fornell and Larcker’s criterion.

Utilizing SPSS 26.0 and PLS-SEM software, the reliability and validity of the measurement scales were examined, and the results are presented in

Table 2. From

Table 2, it can be observed that the Cronbach’s α coefficients for each construct in the study are all greater than 0.7. According to the principle that “Cronbach’s α coefficients above 0.7 indicate good reliability of the scale,” it can be inferred that the measurement scales in the study exhibit good reliability. The standardized loading coefficients of each measurement item on the corresponding latent variables are all greater than 0.7, and the composite reliabilities (CR) for all constructs are greater than 0.7. Moreover, the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct is greater than 0.5. These findings indicate that the variables in this study possess good convergent validity.

Validity analysis is employed to represent the accuracy and effectiveness of the measurement scales. In this study, authoritative scales verified through multiple validations were adopted. The data feedback from pre-surveys was used for modification and optimization, ensuring good content validity.

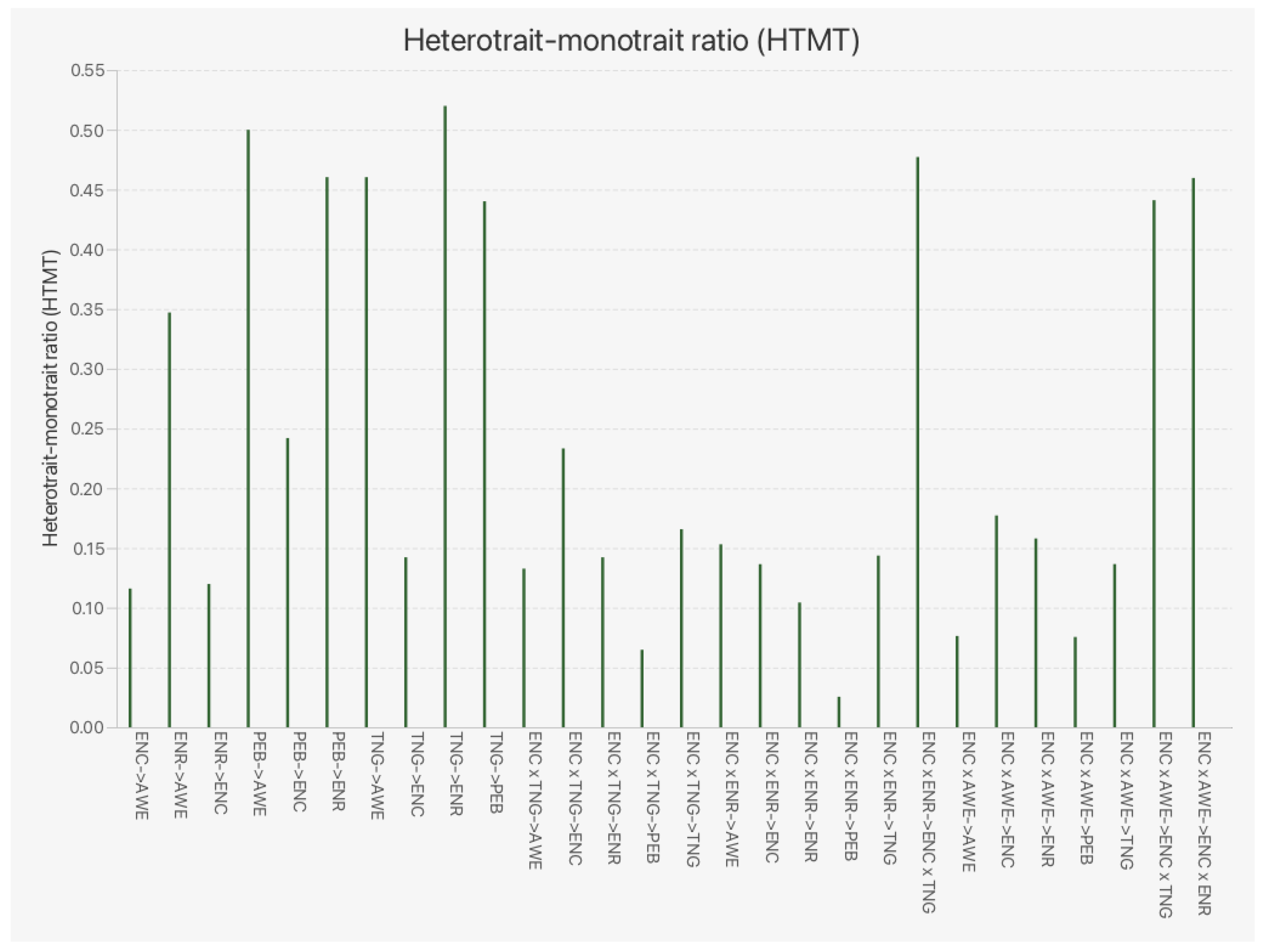

After confirming reliability and discriminant validity, we applied both the Fornell and Lacker’s criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio (see

Figure 2 and

Table 3 and

Table 4. The standard value of HTMT is less than 0.90, and any value exceeding this limit indicates low levels of discriminant validity. All values in the HTMT matrix were below the threshold value (i.e., 0.90) confirming a high level of discriminant validity.

According to the findings in

Table 3 presents the off-diagonal values(bold)in the above matrix are the square correlations between the latent constructs and the diagonals are AVEs. HTMT<0.9(Kline,2015;Henseler et al.,2015), This indicates that the discriminant validity of the measurement scales in the study is satisfactory.

These results satisfy the Fornell and Lacker’s criterion as all the square root of AVE (off-diagonal value) in

Table 5, are higher than each of the correlations, which indicates the greater level of discriminant validity.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

Table 4 displays the results of the multiple regression model, with pro-environmental behavior as the dependent variable and nostalgia, environmental responsibility, and awe as independent variables. As shown in the table, in Model 1, the regression coefficient of nostalgia on environmental responsibility is significantly positive (β=0.464, P<0.001). In Model 2, the regression coefficient of nostalgia on awe is significantly positive (β=0.340, P<0.001), and the regression coefficient of environmental responsibility on awe is also significantly positive (β=0.154, P<0.01). In Model 3, the regression coefficients of nostalgia (β=0.153, P<0.001), environmental responsibility (β=0.249, P<0.001), and awe (β=0.316, P<0.001) on pro-environmental behavior are all significantly positive. From Model 1 to Model 3, it can be observed that environmental responsibility and awe mediate the relationship between nostalgia and pro-environmental behavior.

In this study the SPSS 26.0 and PLS-SEM software, with the Process procedure, was employed to examine the multiple indirect effects of green self-efficacy and perceived green value. A Bootstrap resampling method was applied with 5,000 samples to construct a 95% confidence interval. The results of the mediation analysis are presented in

Table 6.

As indicated in the table, for the path “TNG→ENR→PEB” the indirect effect was found to be 0.117, with a confidence interval of [0.068, 0.175]. Since the interval does not include zero, it suggests that environmental responsibility plays a significant mediating role in the relationship between nostalgia and pro-environmental behavior. Similarly, for the path “TNG→AWE→PEB” the indirect effect was 0.109, with a confidence interval of [0.068, 0.158], indicating a significant mediation effect of awe in the relationship between nostalgia and pro-environmental behavior. Furthermore, for the path “TNG→ENR→AWE→PEB,” the indirect effect was 0.023, with a confidence interval of [0.008, 0.042], signifying the significant combined mediation effects of environmental responsibility and awe in the relationship between nostalgia and pro-environmental behavior.

Table 7.

Moderating Effects Test of Environmental Concern.

Table 7.

Moderating Effects Test of Environmental Concern.

| |

β |

Sample mean |

Standard deviation |

T statistics |

P values |

Result |

| AWE -> PEB |

0.315 |

0.314 |

0.046 |

6.818 |

0 |

Support |

| ENC -> PEB |

0.185 |

0.189 |

0.053 |

3.483 |

0 |

Support |

| ENR -> AWE |

0.157 |

0.158 |

0.046 |

3.41 |

0.001 |

Support |

| ENR -> PEB |

0.264 |

0.264 |

0.05 |

5.301 |

0 |

Support |

| TNG -> AWE |

0.342 |

0.341 |

0.053 |

6.429 |

0 |

Support |

| TNG -> ENR |

0.467 |

0.469 |

0.049 |

9.576 |

0 |

Support |

| TNG -> PEB |

0.161 |

0.161 |

0.048 |

3.345 |

0.001 |

Support |

| ENC x TNG -> PEB |

0.136 |

0.135 |

0.045 |

2.992 |

0.003 |

Support |

| ENC x ENR -> PEB |

-0.01 |

-0.017 |

0.06 |

0.163 |

0.87 |

Not Support |

| ENC x AWE -> PEB |

0.115 |

0.115 |

0.056 |

2.047 |

0.041 |

Support |

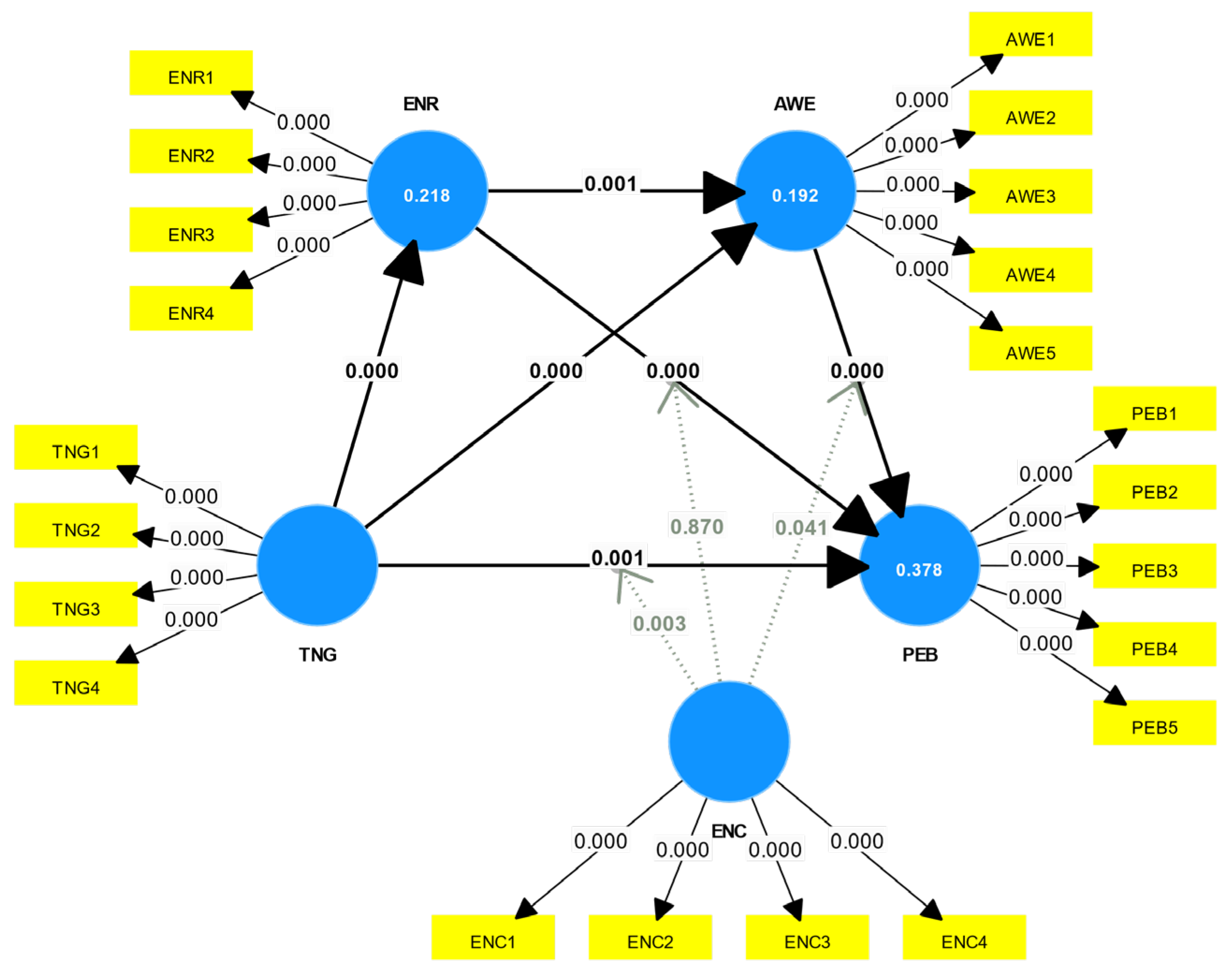

Table 8 and

Figure 3 exhibit all the proposed hypotheses, AWE→PEB (β=0.315,p-value=0<0.05), confirming the hypothesis that the moderating effect of environmental concern exists in the relationship between Nostalgia tourism and pro-environmental behavior. ENC→PEB (β=0.185, p-value=0<0.05); ENR→AWE (β=0.157, p-value=0.001<0.05); ENR→PEB (β=0.264, p-value=0<0.05); TNG→AWE (β=0.342, p-value=0<0.05);TNG→ENR (β=0.467, p-value=0<0.05); TNG→ PEB (β=0.161, p-value=0.001<0.05); ENC x TNG→PEB (β=0.136, p-value=0.003<0.05) and ENC x AWE→PEB (β=0.115, p-value=0.041<0.05) the hypothesis Support;

ENC x ENR→PEB(β=-0.01, p-value=0.87>0.05), hence hypothesis is Not Supported due to its relationship direction being opposite as hypothesized.

5. Conclusion & Contribution

5.1. Conclusion

Based on the framework of emotional event theory, this study attempts to explore the impact mechanism of Nostalgia tourism on rural tourists’ pro-environmental behavior in the post-pandemic era. The study draws four main conclusions:

Overall, the regression coefficient of Nostalgia tourism on pro-environmental behavior is significantly positive, indicating a significant positive impact of Nostalgia tourism on pro-environmental behavior. When the sample is divided by gender, the regression coefficient of Nostalgia tourism on pro-environmental behavior is positive but not significant for male participants, suggesting that Nostalgia tourism does not have a significant positive impact on pro-environmental behavior for male participants. In contrast, for female participants, the regression coefficient of Nostalgia tourism on pro-environmental behavior is significantly positive, indicating a significant positive impact among female participants. It can be observed that there is a significant gender difference in the impact of Nostalgia tourism on pro-environmental behavior, with a more pronounced influence among female consumers.

The interaction term between Nostalgia tourism and environmental concern has a significant regression coefficient on pro-environmental behavior, indicating the moderating effect of environmental concern in the relationship between Nostalgia tourism and pro-environmental behavior. However, the interaction term between environmental responsibility and environmental concern on pro-environmental behavior has a positive but insignificant regression coefficient, suggesting that the moderating effect of environmental concern in the relationship between environmental responsibility and pro-environmental behavior is not supported. Nostalgia tourism is a crucial antecedent variable for environmental responsibility and awe in rural tourist destinations. As a prevalent contemporary attitude and social phenomenon, Nostalgia is prominently expressed in rural tourist destinations. In the post-pandemic era, the more urban residents engage in Nostalgia tourism, the greater their influence on environmental responsibility and awe in rural areas. Additionally, Nostalgia tourism has a greater impact on awe than environmental responsibility.

The numerical value of environmental responsibility on pro-environmental behavior reaches statistical significance, indicating that tourists’ environmental responsibility for rural tourist destinations in the post-pandemic era can effectively influence their pro-environmental behavior in rural areas. It is consistent with the research findings of Qu Ying et al., which used domestic mass tourists in Sanya as samples, carrying out that environmental responsibility identity plays a positive role in driving pro-environmental behavior.

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

This study analyzed the impact of Nostalgia tourism on tourists’ pro-environmental behavior, delving into the underlying mechanisms of psychological variables such as environmental responsibility, awe and environmental concern on tourists’ pro-environmental behavior, highlighting their intrinsic correlations. Furthermore, it underscored the significant roles of these variables in influencing tourists’ pro-environmental behavior. Firstly, this research was conducted within the context of China, providing robust theoretical support for current studies in the Chinese tourism market and validating and supplementing existing research findings related to Nostalgia tourism.

In addition, the study revealed the mediating effects of environmental responsibility and awe between Nostalgia tourism and tourists’ pro-environmental behavior. Tourists, in the process of implementing pro-environmental behavior, need to be mindful of both their self-responsibility for achieving environmental goals and the impact of their behavior on the environment to effectively stimulate environmental responsibility and translate it into actual pro-environmental behavior. Lastly, the study found that awe is the most substantial mediating effect between Nostalgia tourism and tourists’ behavior. While environmental responsibility significantly influences the relationship between Nostalgia tourism and tourists’ pro-environmental behavior, its effect is less pronounced. Both environmental responsibility and awe are crucial factors affecting tourists’ implementation of pro-environmental behavior, with Nostalgia tourism serving as a significant latent variable capable of eliciting environmental responsibility and awe, transforming them into pro-environmental behavior. This study enriches the research in Nostalgia tourism and pro-environmental behavior, providing new insights for the study of the role of nostalgia in other pro-environmental behaviors.

5.3. Future Implications

Firstly, it is essential to strengthen the promotion and education on environmental issues, encouraging tourists to participate in eco-friendly activities and enhancing their environmental responsibility. The government can utilize mass media such as the Internet, television, and newspapers to disseminate information about environmental issues to the general public. Focusing on ecological topics closely related to tourists’ immediate interests, such as air and water pollution, can be emphasized. Presenting the current state of pollution through various forms of publicity and reporting aims to make tourists aware of the severity of environmental protection, triggering emotional resonance among consumers.

In addition, governments and relevant authorities should actively guide consumers to participate in eco-friendly practices, stimulating emotional responses towards environmental protection and increasing consumers’ sense of environmental responsibility. Through eco-friendly practices, consumers can appreciate the importance of actively participating in environmental practices, learn effective environmental protection methods, and be motivated to contribute to improving the ecological situation. This approach aims to enhance consumers’ sense of environmental responsibility.

6. Research Limitations and Prospects

While this study has yielded valuable conclusions, it has certain limitations. Firstly, the research should have taken into account different product categories. Various product categories may exert differing influences on environmental responsibility, awe, and environmental concern, thereby leading to distinct impacts on pro-environmental behavior. Subsequent research could explore the boundary conditions shaping pro-environmental behavior, investigating whether different characteristics inherent in various product categories act as moderating variables between certain variables. This would help clarify the mechanisms underlying consumers’ pro-environmental behavior within different product categories.

Secondly, regarding data collection, the sample scope and size of the survey data may have influenced the study results. Future research could broaden the sample scope and increase the sample size, surveying consumers from diverse occupations and regions to enhance sample representativeness. Finally, Combining demographic characteristics such as occupation and region with psychological factors in the analysis would allow for a comprehensive study. Analyzing the psychological mechanisms of different groups would add specificity to the research, making it more targeted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Afsar, B.; Umrani, W.A. Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior at workplace: The role of moral reflectiveness, coworker advocacy, and environmental commitment. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2020, 27, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibade, F.O.; Adelodun, B.; Lasisi, K.H.; Fadare, O.O.; Ajibade, T.F.; Nwogwu, N.A.; Sulaymon, I.D.; Ugya, A.Y.; Wang, H.C.; Wang, A. Environmental pollution and their socioeconomic impacts. In Microbe mediated remediation of environmental contaminants; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 321–354. [Google Scholar]

- An, W.; Alarcon, S. How can rural tourism be sustainable? A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaki, Z.; Böhmelt, T.; Ward, H. The triangular relationship between public concern for environmental issues, policy output, and media attention. Environmental Politics 2019, 29, 1157–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzidia, S.; Makaoui, N.; Bentahar, O. The impact of big data analytics and artificial intelligence on green supply chain process integration and hospital environmental performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2021, 165, 120557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biresselioglu, M.E.; Demirbag Kaplan, M.; Yilmaz, B.K. Electric mobility in Europe: A comprehensive review of motivators and barriers in decision making processes. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2018, 109, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockarjova, M.; Steg, L. Can Protection Motivation Theory predict pro-environmental behavior? Explaining the adoption of electric vehicles in the Netherlands. Global Environmental Change 2014, 28, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, A.; Pizzolante, M.; Borghesi, F.; Bartolotta, S.; Sarcinella, E.D.; Cipresso, P.; Gaggioli, A. “Standing Up for Earth Rights”: Awe-Inspiring Virtual Nature for Promoting Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2023, 26, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, M.-C.; Kuo, T.-C.; Liao, H.-T. Design for sustainable behavior strategies: Impact of persuasive technology on energy usage. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 248, 119214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwialkowska, A.; Bhatti, W.A.; Glowik, M. The influence of cultural values on pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 268, 122305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Contreras, P.; Cuesta-Valiño, P.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P. Happiness and its relationship to expectations of change and sustainable behavior in a post-COVID-19 world. Journal of Management Development 2023, 42, 458–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, C.J.; Evans, W.N. Private precaution and public restrictions: what drives social distancing and industry foot traffic in the COVID-19 era? 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, M.F.; Charry, A.; Sellitti, S.; Ruzzante, M.; Enciso, K.; Burkart, S. Psychological factors influencing pro-environmental behavior in developing countries: Evidence from Colombian and Nicaraguan students. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11, 580730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, M. Investigating Levels of Climate Change Action and Pro-Environmental Behaviour Post the Covid-19 Pandemic. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ertz, M.; Karakas, F.; Sarigöllü, E. Exploring pro-environmental behaviors of consumers: An analysis of contextual factors, attitude, and behaviors. Journal of Business Research 2016, 69, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, U.; Podnar, K.; Koklič, M.K.; Zabkar, V. The importance of corporate social responsibility for responsible consumption: Exploring moral motivations of consumers. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2019, 26, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Curtis, J. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviours: A review of methods and approaches. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yu, Z.; Ma, Z.; Xu, D.; Cao, S. What factors have driven urbanization in China? Environment, Development and Sustainability 2021, 24, 6508–6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhan, W.; Hu, Y. Consumer purchase intention of electric vehicles in China: The roles of perception and personality. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 204, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Wang, M.; Li, W. The impact of motivation, intention, and contextual factors on green purchasing behavior: New energy vehicles as an example. Business Strategy and the Environment 2021, 30, 1249–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtbrügge, D.; Dögl, C. How international is corporate environmental responsibility? A literature review. Journal of international management 2012, 18, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.P.; Kitson, J.; Clowney, D. Environments past: Nostalgia in environmental policy and governance. Environmental Values 2019, 28, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N. Public awareness about environmental issues: perspective Bangladesh. Asian Affairs 2008, 30, 30–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Li, M.; Gu, Y.; Yang, J. What Is Affecting the Popularity of New Energy Vehicles? A Systematic Review Based on the Public Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalthaus, M.; Sun, J. Determinants of Electric Vehicle Diffusion in China. Environmental and Resource Economics 2021, 80, 473–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, B.; Miller, E.G.; Iyer, E.S. Shades of awe: The role of awe in consumers’ pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Gruber, J.; Reinthaler, M.; Klauenberg, J. Intentions to introduce electric vehicles in the commercial sector: A model based on the theory of planned behaviour. Research in Transportation Economics 2016, 55, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Kim, M.; Han, H.-S.; Holland, S. The determinants of hospitality employees’ pro-environmental behaviors: The moderating role of generational differences. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2016, 52, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Statman, M. Do corporations invest enough in environmental responsibility? Journal of Business Ethics 2012, 105, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koklic, M.K.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K.; Zabkar, V. The interplay of past consumption, attitudes and personal norms in organic food buying. Appetite 2019, 137, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F. Behavioral paradigms for studying pro-environmental behavior: A systematic review. Behavior Research Methods 2023, 55, 600–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashari, Z.A.; Ko, J.; Jang, J. Consumers’ intention to purchase electric vehicles: Influences of user attitude and perception. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Bonn, M.A.; Cho, M. Consumer motives for purchasing organic coffee. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2015, 27, 1157–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Furuoka, F.; Nikitina, L.; Uchiyama, Y.; Lim, B.; Pazim, K.H. Does perceived behavioural control moderate domestic travel intention during the COVID-19 pandemic in China? Anatolia 2022, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Huang, L.M.; He, M.; Ye, B.H. Understanding pro-environmental behavior in tourism: Developing an experimental model. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2023, 57, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liao, G.; Albitar, K. Does corporate environmental responsibility engagement affect firm value? The mediating role of corporate innovation. Business Strategy and the Environment 2020, 29, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wu, W. Why people want to buy electric vehicle: An empirical study in first-tier cities of China. Energy Policy 2018, 112, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, Y. Environmental regulation and green innovation: Evidence from China’s new environmental protection law. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 297, 126698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.I.; Newell, B.R.; Denson, T.F. Would you rule out going green? The effect of inclusion versus exclusion mindset on pro-environmental willingness. European Journal of Social Psychology 2014, 44, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge, C.; Wildschut, T.; Sedikides, C.; Juhl, J.; Arndt, J. The power of the past: Nostalgia as a meaning-making resource. Memory 2012, 20, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, E.A.; De Guimarães, J.C.F.; Dellarmelin, M.L. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on environmental awareness, sustainable consumption and social responsibility: Evidence from generations in Brazil and Portugal. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 286, 124947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, E.; Ruepert, A.; van der Werff, E.; Steg, L. Corporate environmental responsibility leads to more pro-environmental behavior at work by strengthening intrinsic pro-environmental motivation. One Earth 2022, 5, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.H.; Jeong, M. Does a virtual trip evoke travelers’ nostalgia and derive intentions to visit the destination, a similar destination, and share?: Nostalgia-motivated tourism. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2022, 39, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Straßer, P.; Nikendei, C.; Bugaj, T.J.; Kühl, M.; Kühl, S.J. Environmental issues hidden in medical education: What are the effects on students’ environmental awareness and knowledge? Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen 2022, 174, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Xu, A.; Su, X.; Zheng, M. NOSTALGIC ECOTOURISM: HOW NOSTALGIA AFFECTS ECOTOURSITS’BEHAVIOUR. Journal of Environmental Protection and Ecology 2020, 21, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar]

- Thabet, W.M.; Badar, K.; Aboramadan, M.; Abualigah, A. Does green inclusive leadership promote hospitality employees’ pro-environmental behaviors? The mediating role of climate for green initiative. The Service Industries Journal 2023, 43, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-T.; Hsu, H.; Chen, C.-C. An examination of experiential quality, nostalgia, place attachment and behavioral intentions of hospitality customers. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 2020, 29, 869–885. [Google Scholar]

- Vives, A. Social and environmental responsibility in small and medium enterprises in Latin America. In Corporate Citizenship in Latin America: New Challenges for Business; Routledge, 2022; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Chao, C.-H. Nostalgia decreases green consumption: The mediating role of past orientation. BRQ Business Research Quarterly 2020, 23, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, H.; Sarigöllü, E.; Xu, W. Nostalgia prompts sustainable product disposal. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 2020, 19, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.V.; Sintov, N.D. You are what you drive: Environmentalist and social innovator symbolism drives electric vehicle adoption intentions. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2017, 99, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Geng, L.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, K. Greening in nostalgia? How nostalgic traveling enhances tourists’ proenvironmental behaviour. Sustainable Development 2020, 28, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Geng, L. Traveling in haze: How air pollution inhibits tourists’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 707, 135569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; Jia, W. The influence of eliciting awe on pro-environmental behavior of tourist in religious tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2021, 48, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Su, C. Going green: How different advertising appeals impact green consumption behavior. Journal of Business Research 2015, 68, 2663–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wong, C.W.; Miao, X. Analysis of the trend in the knowledge of environmental responsibility research. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 278, 123402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Sheng, G.; She, S.; Xu, J. Impact of consumer environmental responsibility on green consumption behavior in China: The role of environmental concern and price sensitivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O.; Francoeur, V.; Paillé, P. Overcoming the barriers to pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 182, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.Y.; Amirudin, A.; Rahadi, R.A.; Nik Sarah Athirah, N.A.; Ramayah, T.; Muhammad, Z.; Dal Mas, F.; Massaro, M.; Saputra, J.; Mokhlis, S. An Investigation of Pro-Environmental Behaviour and Sustainable Development in Malaysia. Sustainability 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.-m.; Wen, Z.-g. Review and challenges of policies of environmental protection and sustainable development in China. Journal of Environmental Management 2008, 88, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S. Extending the theory of planned behavior to explain the effects of cognitive factors across different kinds of green products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Wan, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, D. Information perspective for understanding consumers’ perceptions of electric vehicles and adoption intentions. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2022, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bai, X.; Shang, J. Is subsidized electric vehicles adoption sustainable: Consumers’ perceptions and motivation toward incentive policies, environmental benefits, and risks. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 192, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gong, X.; Jiang, J. Dump or recycle? Nostalgia and consumer recycling behavior. Journal of Business Research 2021, 132, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Cavusgil, E.; Zhao, Y. A protection motivation explanation of base-of-pyramid consumers’ environmental sustainability. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2016, 45, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Lu, J.; He, W. Relation between awe and environmentalism: The role of social dominance orientation. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S. The effect of COVID-19 risk perception on pro-environmental behavior of Chinese consumers: Perspectives from affective event theory. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 1093999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, Y. How negative anthropomorphic message framing and nostalgia enhance pro-environmental behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: An SEM-NCA approach. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 977381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).