1. Introduction

The tourism industry is now an essential component of the economy of the whole world. It has a substantial impact on the expansion and advancement of a significant number of nations. It has emerged as one of the sectors expanding at one of the highest rates globally, contributing to the production of jobs, earnings in foreign currency, and regional development. Over the years, Australia has attracted many visitors worldwide because of its varied topography, animal population, and extensive cultural history. Policymakers and industry stakeholders in Australia must understand the factors that determine the flow of tourists into the nation to develop successful policies to attract and manage tourism there.

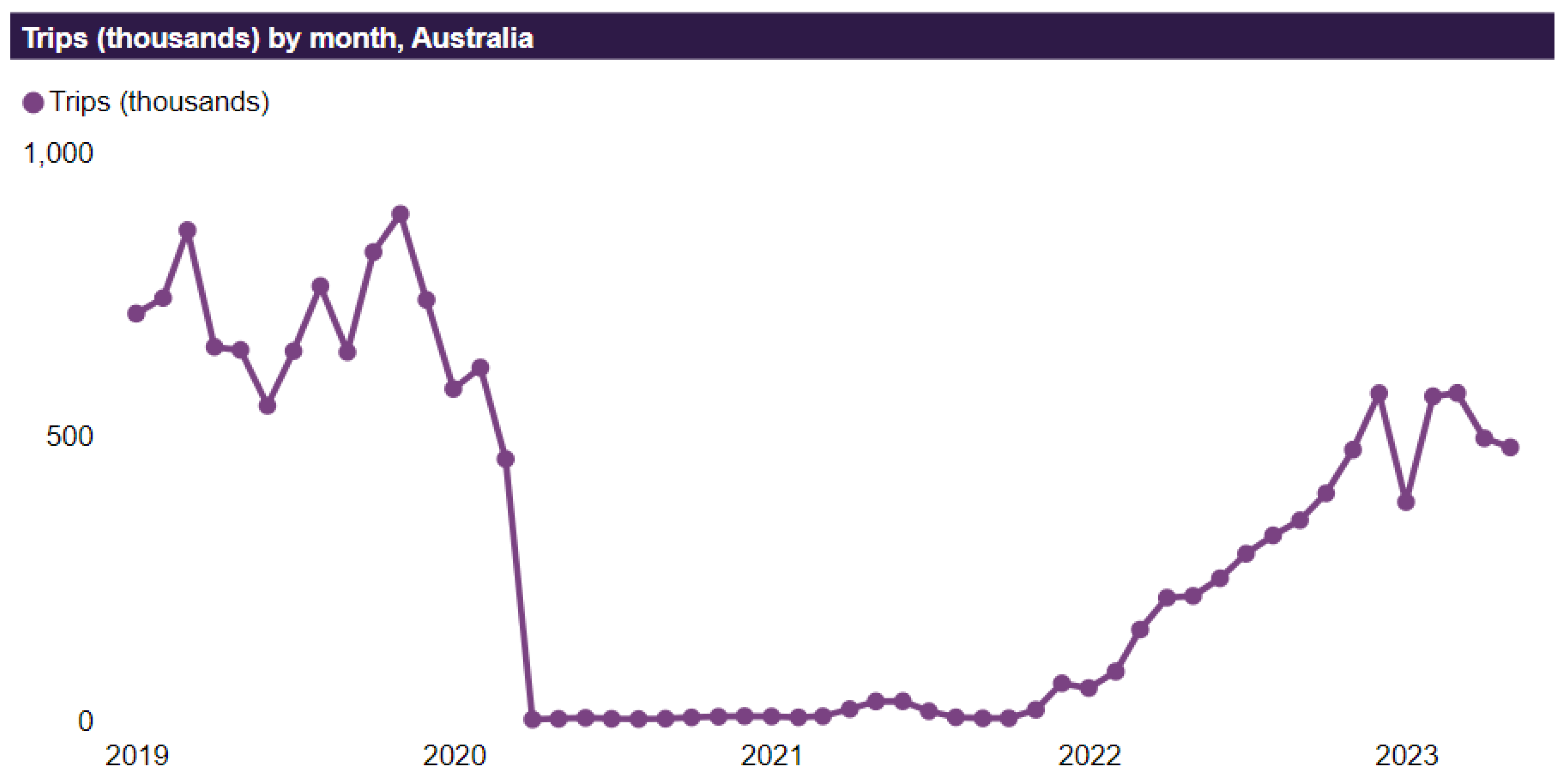

Figure 1.

International Tourism Trend of Australia. (Source: Author’s Compilation based on Australian Bureau of Statistics).

Figure 1.

International Tourism Trend of Australia. (Source: Author’s Compilation based on Australian Bureau of Statistics).

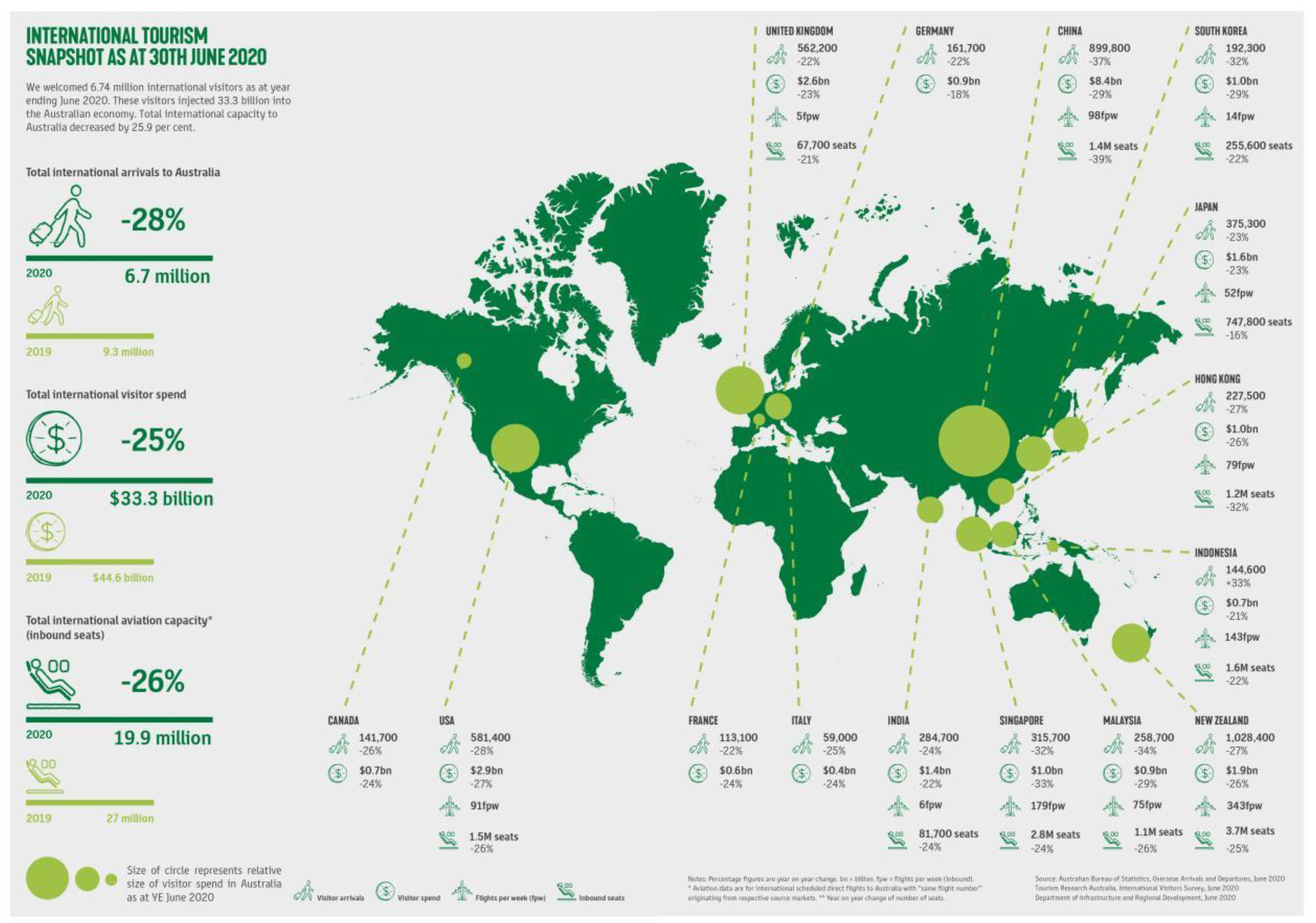

Figure 2.

International Tourism Snapshot of Australia. (Source: Author’s Compilation based on Australian Bureau of Statistics).

Figure 2.

International Tourism Snapshot of Australia. (Source: Author’s Compilation based on Australian Bureau of Statistics).

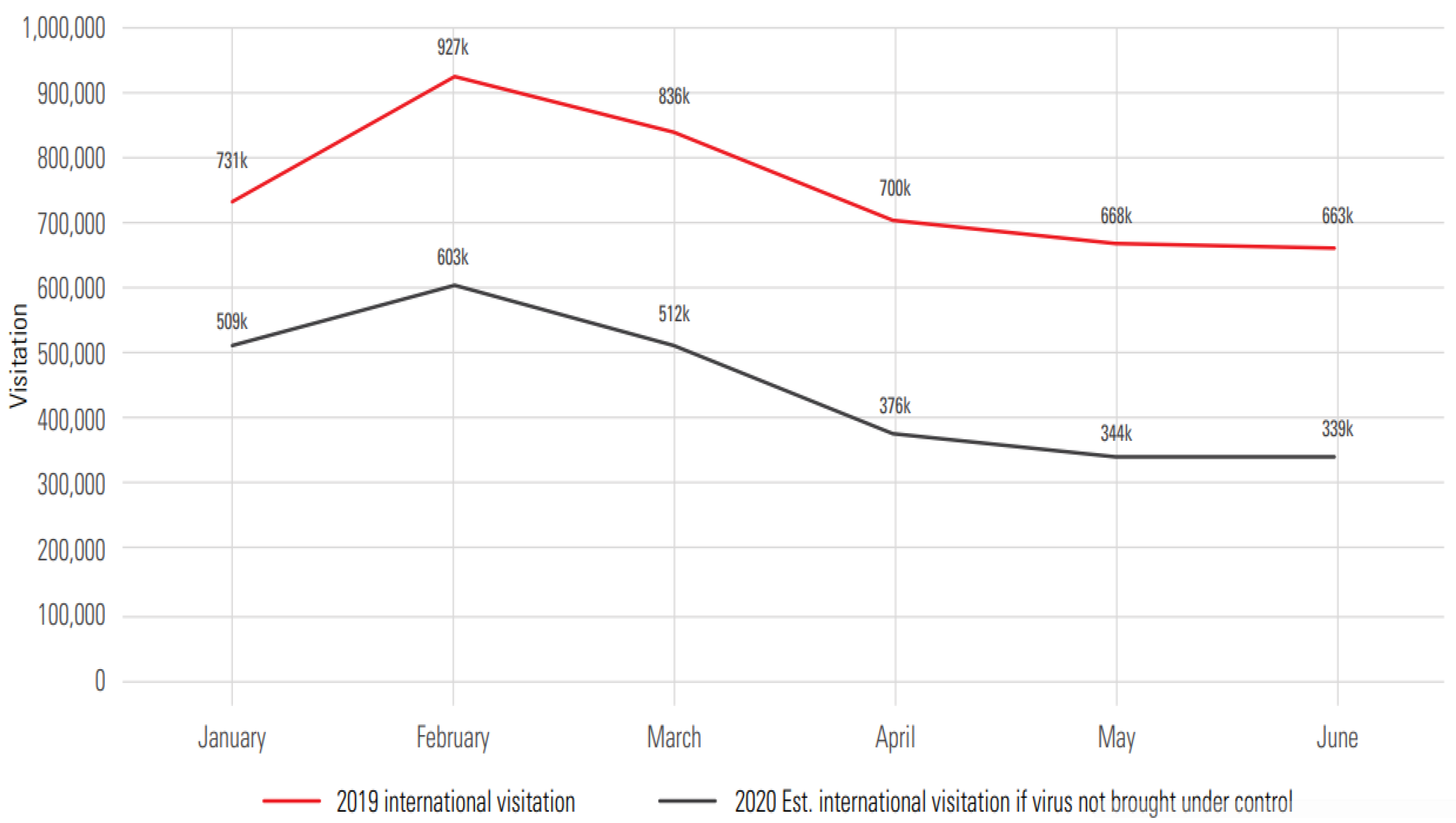

Figure 3.

Estimated Potential Decrease in Total International Visitation to Australia. (Source: Author’s Compilation based on Australian Bureau of Statistics).

Figure 3.

Estimated Potential Decrease in Total International Visitation to Australia. (Source: Author’s Compilation based on Australian Bureau of Statistics).

In tourism research, the gravity model has seen widespread use to analyze the variables that influence visitor flows between nations. This model conceptualizes visitor flows as being impacted by the economic scale of nations and the distance between such countries. It derives its inspiration from Newton's law of gravity. It is an effective method of data analysis in researching bilateral tourist flows and identifying the primary factors that influence these flows. Besides, this model helps the researchers to reveal the intricate linkages and interactions by including GDP, population, distance, and other socio-economic considerations that are the driving force behind tourist migrations.

Although several studies have utilized the gravity model to study the factors that determine international tourism flows, more research is needed to focus primarily on Australian visitor flow. To design focused marketing strategies and foster sustainable tourism development, it is essential to understand the variables that attract visitors to Australia and affect the decision-making processes of these tourists. This study aims to fill in this vacuum in the existing research by using a gravity model to investigate the factors determining the number of tourists visiting Australia. Numerous research studies have been conducted utilizing gravity models to investigate the elements determining international visitor flows. These studies have provided valuable insights into the factors that influence tourism patterns. For example, Smith and Goulias (2012) investigated some influential determinants affecting the visits of tourists to the United States. They instituted that distance, cultural similarity, currency rates, and income levels can inspire international tourists.

Similarly, in a study of Chinese outbound tourism, it has been emphasized the significance of income, currency rates, and distance in driving tourist flows (Song and Li, 2008). Moreover, Pearce and Wu (2016) found the same in a study of Australia that the amount of tourist traffic was significantly impacted by factors such as distance, cultural affinity, income levels, and currency exchange rates. However, further research is required to understand the factors determining Australia's tourist flow, for instance, gross domestic product, gross domestic product per capita, migratory stocks, population size, and cost of living, which have not been explored yet. Hence, this paper contributes to the larger area of gravity modeling in tourism research and broadens our knowledge of the elements that influence the movements of tourists.

This study is anticipated to make several significant additions to the current body of research on international tourism and the factors determining visitor flows. First, it will give insights into the particular elements that influence the flow of tourists to Australia. This will provide a fresh viewpoint on a location with distinct natural and cultural attractions. Second, the results will assist policymakers and industry players in Australia in developing successful strategies to both attract and manage the influx of tourists from other countries.

The remaining portions of this document are structured as follows: In the next section, "

Section 2," a theoretical review of the gravity model and its use in tourist research is presented. The methodology and data-collecting procedures used in this research are discussed in the third section. The empirical results are presented in

Section 4, and a discussion of the findings. In the fifth section, we provide an in-depth analysis and our interpretation of the findings. In the last quarter of the study, titled "Conclusion," a summary of the most important results, a discussion of the consequences of those findings, and suggestions for further research are presented.

This introduction has offered a summary of the study subject and emphasized the importance of knowing the factors determining the number of tourists visiting Australia. This research intends to shed light on the fundamental elements driving tourist flows to Australia by adopting a gravity model approach as its method of inquiry. The results will contribute to academic research and practical consequences for decision-makers in the tourism policy-making sector and stakeholders in the tourist industry. In the following parts of this article, we will go further into the methodology, findings, and analysis to give a complete knowledge of the factors determining the number of tourists visiting Australia.

1.1. A Brief Overview of the Australian Tourism Sector and the Impact of COVID-19 on Australian Tourism

Australia, sometimes known as the "Land Down Under," is a huge, diverse southern hemisphere nation. It is the world's sixth-largest nation by land area, with 7.7 million square kilometers, and is bounded by the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Australia is known for its breathtaking natural vistas, including the renowned Sydney Opera House and the Great Barrier Reef, the wide desert, and ancient rainforests.

The nation has a population of more than 25 million people, with the majority concentrated in big cities like Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth, and Adelaide. Canberra is the capital city and the seat of the Australian government.

Australia has a diverse cultural legacy developed by Indigenous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who have lived on the continent for tens of thousands of years. In the late 18th century, European exploration and colonization started, leading to the foundation of a British colony that subsequently became a federation of six states and two territories, becoming the current country of Australia in 1901.

The Australian economy is highly developed and one of the wealthiest in the world. Mining, agriculture, manufacturing, and services are all critical industries. The flourishing Australian tourist industry is a crucial contribution to the economy.

1.2. The Australian Tourism Industry and Air Traffic Flow

The Australian tourist industry is an integral part of the country's economy, providing employment, cash, and opportunities for cultural interaction. Air traffic flow is an essential measure of the health of the tourist industry since it reflects the movement of both international and domestic travelers to and from Australia.

The development of foreign airlines' routes to Australia and the rising desire from Australian citizens to go overseas have aided the rise of air traffic flow throughout the years. The country's allure stems from its diversified offers, which include world-famous sites, natural marvels, bustling cities, and rare species.

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, Australia's aviation passenger movements exhibited a constant rising trend, according to statistics from the Australian Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE). Total passenger movements reached a record 164 million in 2019, with foreign travelers accounting for a significant portion of this figure (BITRE, 2019). This consistent development reflected Australia's appeal as a preferred location for worldwide travelers.

The leading international airports in Australia, such as Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Perth, served as vital entry points for foreign travelers. Millions of passengers arrive and depart from these airports each year, promoting economic activity and cultural contact between Australia and the rest of the globe.

1.3. The Impacts of Covid-19 on Australian Tourism

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 had an unprecedented and devastating effect on the worldwide tourist sector, with Australia being one of the most severely impacted nations. Numerous travel restrictions, border closures, and quarantine procedures were put in place to stop the spread of the virus. The effects of the pandemic were felt across the travel sector, from airlines and hotels to tour operators, restaurants, and retail enterprises. Many businesses had financial difficulties, resulting in job losses and temporary closures. Domestic tourism suffered as state and territory borders were blocked on a regular basis in response to localized outbreaks.

As a consequence, aviation traffic into and out of Australia fell precipitously. International travel came to a halt as several nations locked their borders to prevent sick people from entering. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), international air travel demand fell by 98.1% in 2020 compared to the previous year (IATA, 2020). The Australian government reacted quickly to safeguard public health by instituting severe border restrictions and travel prohibitions. As a result, passenger movements at the country's main international airports decreased significantly, affecting airlines, airport operators, and various other tourism-related businesses. The closing of international borders resulted in a significant loss of incoming tourist earnings, which had a knock-on impact on the Australian economy. According to Tourism Research Australia, the predicted loss in foreign tourist expenditure during the epidemic was billions of euros (Tourism Research Australia, 2021).

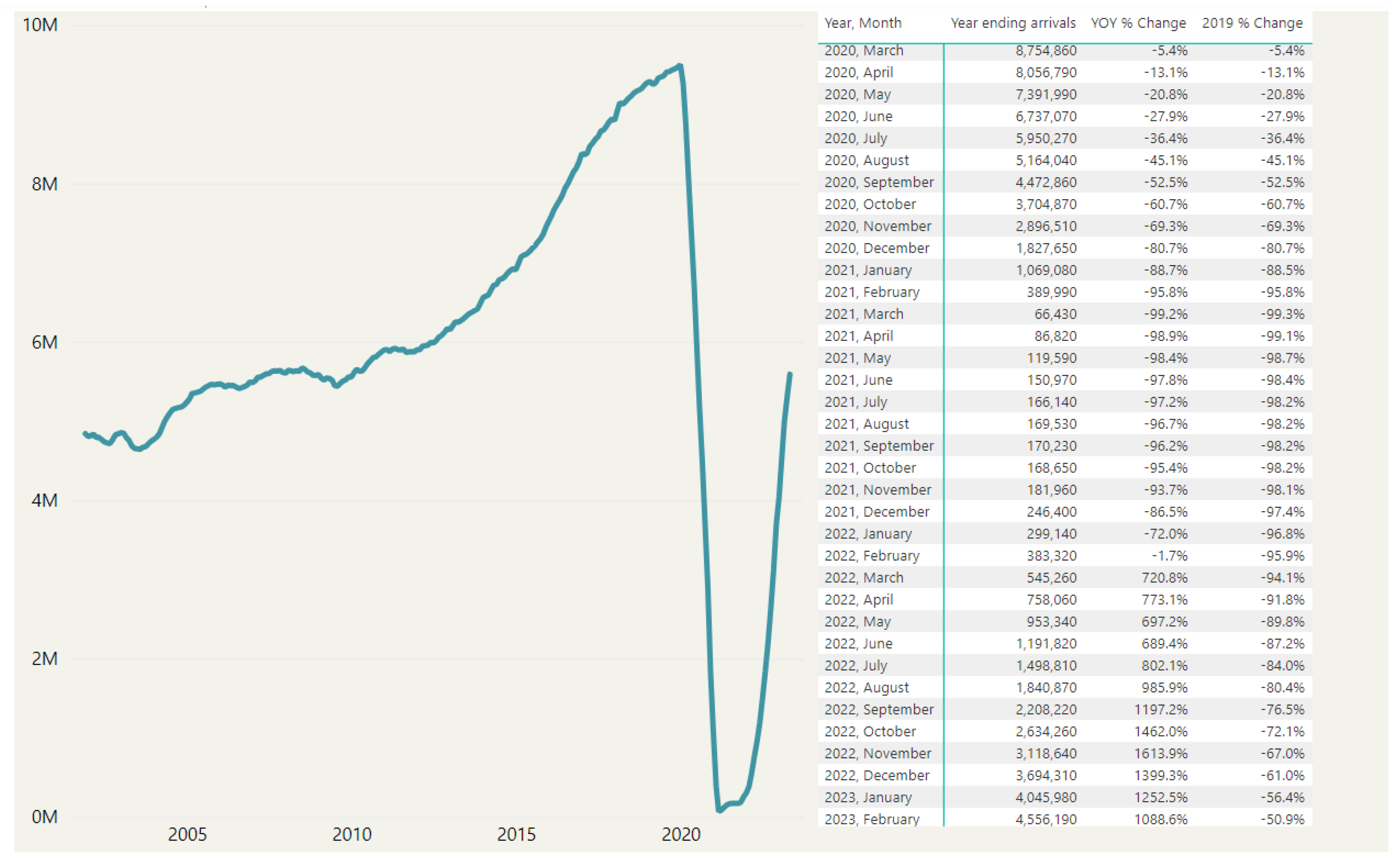

Figure 4.

Year-ending arrivals and YOY% change in Australian tourism (Source: Author’s Compilation based on Australian Bureau of Statistics).

Figure 4.

Year-ending arrivals and YOY% change in Australian tourism (Source: Author’s Compilation based on Australian Bureau of Statistics).

The Australian government launched several economic stimulus programs, financial aid, and targeted assistance measures to help the suffering tourist industry. These measures attempted to assist firms in remaining solvent, retaining employment, and preparing for the future reopening of international borders when it was safe. Despite the difficulties, Australia's tourist industry displayed tenacity and adaptation. Many tour companies turned their attention to domestic travelers, emphasizing local travel experiences and distinctive sites inside the nation. As the globe steadily recovers from the epidemic, Australia's rich natural and cultural attractions are also prepared to capture travelers once again and contribute to the country's tourist sector's rebirth.

2. Literature Review

The existing research on the tourist flow is quite extensive. By synchronizing the recent literature based on the determinants of the tourist flow, positive impacts of tourism, economic benefits, and cultural implications, this paper incorporates a comprehensive analysis to explore the determinants of tourist flow, considering both positive and negative consequences and the barriers to international tourism.

Exploring a good number of studies, it has been found that weather conditions can impact tourism as a strong determinant. Muñoz et al. (2023) described that weather conditions considerably impact tourism demand across all seasons. It revealed that both temperature and precipitation had a considerable impact on the number of tourist arrivals. For instance, temperature strongly impacted tourist arrivals during summer, while rainfall played a more prominent role in the shoulder seasons. Another study highlighted the concentration of tourist arrivals during specific months and the challenge of attracting visitors during off-peak periods. The research identified several factors, including climatic conditions, cultural events and festivals, school holidays, and marketing efforts, contributing to tourism seasonality (Duro & Turrion-Prats, 2019).

On the other hand, multiple linguistic factors, including official languages, lingua franca, linguistic proximity, and language preferences, can significantly impact international tourist arrivals. A common official language between the source and destination countries positively influenced international tourist arrivals. Countries sharing the same official language exhibited higher tourism flows due to improved communication and reduced language barriers (Khalid et al., 2022). Okafor et al. (2018) also confirmed that a shared language can enhance communication, cultural exchange, and familiarity, positively influencing tourism flows.

In addition, spillover effects can also positively impact tourism flow. The presence of spatial spillover effects influenced China's outbound tourist flow to the Silk Road destinations (Deng & Hu, 2019). In another research, Kim et al. (2022) also confirmed that visitor flows to one attraction can positively influence the popularity and demand for neighboring attractions. The control variables, such as attraction characteristics (e.g., size, uniqueness), accessibility measures (e.g., transportation infrastructure, travel time), and socio-economic factors (e.g., population, income levels) interacting with visitor flows, further shape the spillover effects. Likewise, Socio-Demographic Factors, Destination Image, and Marketing, Infrastructure and Accessibility, and Push and Pull factors are some important determinants that also influence international tourist flows (Gidebo, 2021) (Yerdelen et al., 2020) (Fernández et al., 2020). In addition, factors such as travel costs, income levels, transportation networks, accommodation, food, population, size, and destination attractiveness exhibit varying degrees of influence on tourist flows (Zhu et al., 2018) (Smolčić et al., 2017) (Khoshnevis et al., 2017).

Moreover, the 'multilateral resistance to tourism' concept highlighted that destination attractiveness is crucial to tourists' travel decisions. This analysis reveals that tourists are more likely to choose beautiful destinations and exhibit a 'pull factor,' thereby influencing the overall tourism flows (Harb & Bassil, 2020) (De la Peña, Núñez-Serrano, Turrión, and Velázquez, 2019). Furthermore, Bazargani and Kiliç (2021) emphasized the importance of these factors contributing to tourism competitiveness and their impact on the overall performance of the tourism sector. Also, another study in Australia found that tourism expenditure, employment, value-added, resource efficiency, visitor satisfaction, and community well-being enhance tourism productivity (Pham, 2020).

Tourism flows can also influence migration flows and vice versa, indicating that these two phenomena are interrelated and mutually reinforcing. Positive perceptions of a destination, including safety, quality of life, and cultural richness, can attract tourists and potential migrants (Santana-Gallego & Paniagua, 2022). In addition, a migrant community from a particular country in a destination country was correlated with increased tourist arrivals from that country (Okafor et al., 2022). Moreover, focusing on EU28 countries, a study found that migrants can act as a bond between their home countries and their host countries, attracting visitors from their home countries to visit them. Furthermore, in another study on EU member states, Provenzano and Baggio (2017) highlighted that the contribution of human migration, specifically VFR travel (visits made by individuals to their friends and relatives residing in another location), positively impacts destination economies. Also, it promotes cultural tourism and attracts visitors interested in experiencing different cultures (Provenzano, 2020).

Moreover, Zhang et al. (2019) describe that cultural factors, such as language and religious similarities, positively impact bilateral international tourist flows. Similarly, another study on GCC countries implies that cultural similarities between GCC countries and potential destinations positively influence outbound tourism (Balli et al., 2020). Nevertheless, cultural differences also shape tourism patterns, suggesting that cultural factors still influence tourists' destination choices (Yang et al., 2019).

Besides, happiness can also be an essential indicator of tourism growth. Paniagua et al. (2022) found that happiness influences tourism decisions. They explained that higher happiness levels were associated with increased tourism demand, suggesting that individuals with higher subjective well-being are more likely to engage in travel and tourism activities. In addition, in different studies, Waqas-Awan et al. (2021) and Bao and Xie (2019) described that personal income can influence international tourism expressively. The authors found that there has been a positive association between personal income and tourism behavior. Besides, another study on GCC countries highlighted that income level escalation influences residents engaging in international travel (Balli et al., 2020).

Moreover, it has also been emphasized that tourist arrivals or expenditures are a better indicator for predicting and understanding tourism demand (Rosselló-Nadal & He, 2020). Nevertheless, currency fluctuations and exchange rates can affect tourism demand (Nguyen & Valadkhani, 2020). Another research also investigated the influence of exchange rates on tourism demand, as exchange rate fluctuations can affect travel costs (Tavares & Leitao, 2017). However, a favorable exchange rate and a solid economic performance positively affect international tourist arrivals (Shafiullah et al., 2019) (Xu et al., 2019) (Vítová et al., 2019).

In addition, some determinants of inbound tourism, such as economic factors, geographic factors, travel restrictions, exchange rates, air connectivity, and cultural similarities, are key drivers of tourism demand (Altaf, 2021) (Ghosh, 2022). Similarly, another study on SIDS (Small Island Developing States) countries described those factors, including GDP per capita, population size, air connectivity, distance from source markets, and political stability, significantly affecting tourist arrivals (Takahashi, 2019). In addition, some more determinants include economic growth, inflation, oil prices, transportation costs, and political stability, which also affects the arrival of international tourists (Martins et al., 2017) (Pham et al., 2017). Besides, some trust elements include perceived safety, perceived attractiveness, destination image, prior experience, and familiarity with the destination also play a significant role in shaping tourists' trust toward goals (Artigas et al., 2017).

Moreover, Cultural heritage sites create a unique appeal for tourists. Their global recognition, historical significance, and cultural appeal significantly stimulate visitor numbers (Panzera et al., 2021). Likewise, focusing on Italy, a study indicates that certain regions in a particular country can be more attractive to tourists based on natural landscapes, cultural heritage, infrastructure, and services (Giambona & Grassini, 2020) (Pompili et al., 2019). Additionally, it has been reported that having more memorable experiences is more likely to exhibit positive behavioral intentions among tourists, including revisiting the destination, recommending it to others, and engaging in positive word-of-mouth (Sharma & Nayak, 2019).

Besides, flight availability can be another important determinant for international tourism. In a study, it has been highlighted that Increases in seat capacity are associated with higher tourist arrivals, indicating a positive relationship between flight availability and international tourism flows (Alderighi & Gaggero, 2019). Additionally, the availability of low-cost flights increases accessibility and affordability, attracting more tourists to the destination. Hence, low-cost carriers significantly stimulate visitor arrivals and expand the tourism market (Santos & Cincera, 2018). Nevertheless, Alexander and Merkert (2017) claimed that market characteristics, economic conditions, infrastructure availability, and regulatory frameworks could be challenging for air freight transportation.

Besides, several journals have studied the impact of ICT and infrastructure development in the tourism sector. Adeola and Evans (2020) strongly believe that there is a positive association between ICT development and tourism growth in Africa. Improved access to ICT, including internet connectivity and mobile phone usage, contributes to enhanced information dissemination, marketing, and communication within the tourism sector, attracting more tourists. Likewise, Improvements in tourism-related infrastructure, such as the expansion of hotel capacity and the enhancement of transportation facilities and recreational amenities, contribute to increased tourism demand and attract more international visitors to urban destinations (Lim et al., 2019).

Hence, these dynamics bring substantial direct and indirect economic benefits tourism generates. Some immediate economic benefits generated by tourism include employment creation, income generation, foreign exchange earnings, and tax revenue. Similarly, some indirect economic advantages on related industries, such as agriculture, manufacturing, and services, and the potential for stimulating entrepreneurship and investment (Li et al., 2018). Moreover, these features impact knowledge exchange and collaboration among tourism stakeholders by creating favorable tourism features (Czernek, 2017). Besides, an interesting study found that Panda diplomacy initiatives, such as the loaning of pandas to other countries, are associated with increased interest and visitation from Chinese tourists. The presence of pandas in host countries serves as a symbolic attraction and motivates Chinese tourists to visit (Okafor et al., 2021).

However, several studies investigated the negative impacts on international tourist arrivals. In a recent survey, it was probed that extreme weather conditions (excessively hot or cold temperatures, heavy precipitation) had a more pronounced impact on tourism demand than moderate variations (Muñoz et al., 2023). Likewise, various types of natural disasters, such as hurricanes, earthquakes, floods, and volcanic eruptions, lead to a decline in tourist arrivals in affected destinations (Rosselló et al., 2020). Moreover, air pollution can act as a deterrent to international tourists. Xu and Dong (2020) found that higher levels of air pollution, represented by PM2.5 concentration, are associated with reduced tourist arrivals to China.

Besides, Ghosh (2022) analyzes the effects of previous pandemics and the unprecedented challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic; the author provides insights into the magnitude and duration of the impact on tourism demand. The study highlights the necessity of implementing effective crisis management strategies, enhancing health-related infrastructure and communication, and developing targeted recovery plans to rebuild tourism demand. Likewise, Farzanegan et al. (2021) also investigated the global nature of the pandemic and the broader implications it has had on tourism. Their analysis found the pandemic's effects on international tourist arrivals.

There is also a negative relationship between distance and inbound tourism demand. The greater geographical distance between Australia and Asian countries was found to deter tourism flows. This highlights the role of space as a barrier to travel and suggests that proximity plays a significant role in tourism demand (Ghosh, 2022). Likewise, another study on Turkey reveals a negative association between distance and tourism demand. Countries closer to Turkey tend to generate higher tourist flows, indicating the influence of proximity on travel decisions (Ulucak et al., 2020). Additionally, Islands and geographically isolated destinations experience lower tourist arrivals than mainland destinations (Dropsy et al., 2020).

Moreover, Khan et al. (2021) investigated the influence of economic uncertainty on tourism trends. The study finds a negative relationship between economic uncertainty and tourism demand. Higher levels of economic uncertainty are associated with decreased tourism demand, as individuals and households become more cautious about their travel expenditures during uncertain economic times. Similarly, uncertainties related to travel arrangements, destination characteristics, unfamiliar cultural environments, personal safety, health concerns, financial risks, and socio-political stability also affect tourists' decision-making (Karl, 2018) (Habibi, 2017).

In addition, higher levels of political risk, including political instability, corruption, and social unrest, hurt tourism development (Ghalia et al., 2019). Besides armed conflict, military expenditure also affects tourism arrivals negatively. A study indicates that countries experiencing armed conflicts tend to attract fewer tourists due to safety concerns, perceived risks, and disruptions to tourism infrastructure and services (Khalid et al., 2020). Moreover, terrorism incidents have a negative impact on tourism demand. Both international and domestic tourist arrivals in Kenya are significantly affected by acts of terrorism. Tourists exhibit heightened sensitivity to security concerns and are likelier to avoid destinations with a history of terrorist incidents (Buigut, 2018).

Overall, adding to the current literature, this paper gives new insights about Australian tourism from a novel viewpoint. Besides, using a gravity model, it aims to fill the research gap by examining the variables influencing the number of tourists that visit Australia. Additionally, this study not only contributes to the refinement of gravity models in the context of Australian tourism but also sheds light on the intricate interplay between various determinants of tourist flow. Moreover, going beyond conventional models, this study commences a nuanced examination of the impact of the COVID-19 period, allowing for a dynamic understanding of the tourism landscape.

3. Model

The gravity model was applied widely to describe a variety of macroeconomic variables including tourist revenues (Morley et al., 2014) cross-border migration (Beine & Parsons, 2015), among other things.

Our empirical model of tourist flow was constructed using the Gravity framework and was based on the method suggested by Lueth and Ruiz-Arranz (2008), Ahmed and Martnez-Zarzoso (2016), Silva et al. (2022), and Ahmed et al. (2021). The fundamental paradigm for tourist flow to Australia from partner countries, denoted by ''i'' (home country) and ''j'' (partner country) is as follows:

The model assumes tourist flow is directly proportional to home and partner countries' GDP and inversely proportional to Distance. Taking natural log on both sides, equation (i) can be rewritten as

Here, = Tourist flow to home country i from country j at time t, = GDP of country i (home country at time t, = GDP of country j (partner country) at time t = Distance between country i and j andis the random error term.

Since the paper deals with tourist flow to Australia (home country) from their partner countries, we can incorporate '' i=1, 2...36'' in the equation. The model can be further extended using a set of suitable control variables

.

To extend the Gravity model of tourist flow, first, we take a standard set of gravity control variables like population, contiguity, common language, and shared colonial history from the dynamic Gravity dataset (Gravity Portal: Dynamic Gravity Dataset (n.d.)). Since determining the effect that COVID-19 has on the amount of money that is sent back home is our primary aim, the first thing that we do is include a COVID dummy into the Gravity model. The COVID dummy variable is assumed to have a value of 0 for periods that occur before the COVID breakout, and it is assumed to have a value of 1 for periods that occur after the COVID breakout. In addition to this, we also performed estimations using the following explanatory variables: No. Regarding the number of COVID cases, the number of COVID deaths, and the rollout of vaccinations in both the home country and partner countries. The extended linear models can be written as;

4. Data & Variables

We use air traffic flow to figure out the monthly statistics on tourist flow to Australia from its partner countries (January 2018 to May 2022). Monthly Industrial Production Index (IPI) statistics are used as an alternative for monthly GDP data as a proxy for GDP. This is because monthly GDP data is not available. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) gathered monthly IPI data from International Financial Statistics. IOM is where migration statistics are collected. The Dynamic Gravity datasets created by the United States International Trade Commision are used to determine distance and standard gravity control factors like population, contiguity, common language, common colonial origin, etc. Data on cases, deaths, and vaccinations for COVID are gathered from the Our World in Data website. To identify the COVID Pandemic phases, a COVID dummy is created. Pre-COVID periods (January 2018–January 2020) are indicated by the reference dummy 0. Periods of the COVID pandemic (February 2020 to May 2022) are denoted by 1.

5. Result and Discussions

LN_GDPD represents the natural logarithm of the destination country's gross domestic product (GDP). The coefficient values (2.767, 2.909, 3.103, 0.917) indicate that an increase in destination country GDP is associated with an increase in Australian tourist flow. The coefficients are statistically significant (marked by ***), suggesting a strong relationship between GDP and tourist flow. LN_GDPP variable represents the natural logarithm of the GDP per capita of the destination country. The negative coefficient values (-0.0586, -0.0583, -0.0592, -0.0519) suggest that a higher GDP per capita in the destination country is associated with a decrease in Australian tourist flow. The coefficients are statistically significant, indicating a substantial impact of GDP per capita on tourist flow. LN_Mig_D represents the natural logarithm of the migration stock of the destination country. The positive coefficient values (0.00944, 0.00932, 0.00827, 0.00699) suggest that a more extensive migration stock in the destination country is associated with increased Australian tourist flow. The coefficients are statistically significant, indicating a positive relationship between migration stock and tourist flow. LN_Mig_P represents the natural logarithm of the migration stock of the origin country. The negative coefficient values (-0.00921, -0.00875, -0.00699, -0.00961) suggest that a more extensive migration stock in the origin country is associated with a decrease in Australian tourist flow. The coefficients are statistically significant, indicating a negative impact of migration stock on tourist flow. LNDIST is the natural logarithm of the distance between the origin and destination countries. The coefficient values (0.0120, 0.0144, 0.0321, 0.0499) suggest a greater distance between the countries is associated with increased Australian tourist flow. However, the coefficients are not statistically significant, indicating that space may not substantially impact tourist flow.

LN_T_POP_D represents the natural logarithm of the population of the destination country. The coefficient values (-2.054, -1.268, -0.553, -0.00495) suggest that a larger population in the destination country is associated with a decrease in Australian tourist flow. However, the coefficients are not statistically significant, indicating that the population may not substantially impact tourist flow. LN_TPOP_P is the natural logarithm of the people of the origin country. The positive coefficient values (0.0246, 0.0262, 0.0260, 0.0276) suggest that a larger population in the origin country is associated with increased Australian tourist flow. The coefficients are statistically significant, indicating a positive relationship between people and tourist flow. COL variable represents the cost of living in the destination country. The coefficient values (0.0222, 0.0264, 0.0272, 0.0208) suggest that a higher cost of living in the destination country is associated with increased Australian tourist flow. However, the coefficients are not statistically significant, indicating that the cost of living may have little impact on tourist flow.

Table: 1 goes here

Table: 2 goes here

Table: 3 goes here

6. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Using a gravity model as our method, the purpose of this research was to analyze the factors determining the number of tourists visiting Australia. We tried to understand the primary forces responsible for the flow of tourists to Australia by researching a wide variety of economic, demographic, and sociocultural issues. The results contribute to academic research and practical implications for policymakers and industry stakeholders. Both sets of audiences may benefit from these contributions. The assessment of the gravity model yielded some notable findings on the factors that determine the flow of tourists to Australia. A destination country's total and per capita GDP were shown to influence the number of tourists that visited that country favorably. This indicates that as the economic size and wealth of the destination country increase, more visitors are drawn to Australia. Secondly, the migration rate has a positive impact on both the country of origin and the country of destination. Thirdly, the diaspora population is another driving force behind improved tourism between nations. Nevertheless, distance did not turn out to be a statistically significant factor in tourism in Australia. Hence, physical proximity might play a minor role in visiting Australia.

However, determinants like accessibility and transportation infrastructure might lessen the effect of physical distance. In addition, it was shown that the cultural similarities between countries had a statistically significant impact on the flow of tourists. These finding also suggests that shared cultural characteristics and interests affect travel choices.

The results of this research have significant repercussions for the decision-makers and industry stakeholders engaged in the marketing and administration of Australian tourism. Following is a list of policy proposals that have been presented based on the identified determinants:

a) Economic Policies: Governments should prioritize programs that seek to improve the economic well-being of the country to which they export their goods. This involves activities such as promoting economic development, improving infrastructure, and developing a favorable business climate to attract more visitors. In addition, there should be efforts made to enhance the accessibility of tourist-related services and goods as well as their capacity to compete in the market.

b) Engaging the Diaspora Because migration stocks have a beneficial impact on tourism flows, officials should seriously consider developing focused marketing tactics that involve and use the diaspora groups. The marketing of Australia as a preferred destination among these groups may be facilitated through collaborative efforts such as cultural festivals, exchange programs, and community-based tourism projects. These kinds of projects can be found in Australia.

c) Marketing and Branding: The findings show the need to present Australia's distinctive cultural history and natural attractions to prospective visitors. This is especially important because Australia has many natural attractions. Marketing initiatives have to center on presenting the varied landscapes, native cultures, and culinary traditions of the nation, as well as the abundant animals. Increased exposure and the ability to appeal to a wider variety of travelers may be achieved via partnerships with foreign travel agents, airlines, and internet platforms.

d) connection and Infrastructure: Since distance was not identified as a critical factor, officials could focus on enhancing relationships and transportation infrastructure to make it simpler for people to visit Australia. Increasing visitor arrivals may be helped by improving air connections and airline routes and streamlining the visa application and approval procedure.

e) Collaborative Partnerships: To build comprehensive tourist policies, governments and other players in the sector should work together to foster partnerships. In this context, "collaboration" refers to working with the commercial sector, tourist boards, travel agencies, and local communities to guarantee sustainable tourism practices, destination management, and the preservation of natural and cultural assets.

f) Research and Monitoring: To effectively modify policies and plans, continuous monitoring of tourist trends, market dynamics, and developing consumer preferences is vital. It is essential to invest in research and data collecting to obtain insights about developing tourist habits and preferences, making it easier to make decisions based on facts.

Even though this research contributes to our understanding of the factors that determine the number of tourists that visit Australia, it is essential to note that it has significant limitations. To begin, the gravity model method considers just a fraction of the potential variables that influence the flow of tourists. Other unobserved factors may play a part in the phenomenon. In a further study, it could be worthwhile to investigate the possibility of including other factors, such as currency exchange rates, levels of political stability, the image of the destination, and the amount spent on marketing.

The second primary emphasis of the research was on the arrival of tourists to Australia. The study of outbound tourism from Australia would give a complete knowledge of the tourist flows between countries and the reciprocal impacts between nations.

This research only employed cross-sectional data for its analysis, severely hindering the capacity to portray temporal dynamics and causation accurately. In further investigations, longitudinal data may be used to investigate how the factors that influence the number of tourists that visit Australia have changed over time.

In conclusion, for policymakers and other industry stakeholders to establish successful strategies for supporting sustainable tourism development, they need to have a solid grasp of the factors that determine the flow of tourists to Australia. This research gives unique insights into the elements that determine visitor flows to Australia. These findings also have practical implications for policy formation, marketing, and the administration of tourist destinations. Australia can position itself as an appealing and competitive tourist destination in the global market if it follows the recommendations about the policies to be implemented and continuously monitors tourism trends.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Adeola, O., & Evans, O. (2020). ICT, infrastructure, and tourism development in Africa. Tourism Economics, 26(1), 97-114.

- Agiomirgianakis, G., Serenis, D., & Tsounis, N. (2014). Exchange rate volatility and tourist flows into Turkey. Journal of Economic Integration, 700-725.

- Alderighi, M., & Gaggero, A. A. (2019). Flight availability and international tourism flows. Annals of Tourism Research, 79, 102642.

- Alexander, D. W., & Merkert, R. (2017). Challenges to domestic air freight in Australia: Evaluating air traffic markets with gravity modelling. Journal of Air Transport Management, 61, 41-52.

- Altaf, N. (2021). Modelling the international tourist arrivals in India. Tourism Planning & Development, 18(6), 699-708.

- Alvarez-Diaz, M., D'Hombres, B., Ghisetti, C., & Pontarollo, N. (2020). Analysing domestic tourism flows at the provincial level in Spain by using spatial gravity models. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(4), 403-415.

- Artigas, E. M., Yrigoyen, C. C., Moraga, E. T., & Villalón, C. B. (2017). Determinants of trust towards tourist destinations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(4), 327-334.

- Balli, F., Balli, H. O., & Louis, R. J. (2016). The impacts of immigrants and institutions on bilateral tourism flows. Tourism Management, 52, 221-229.

- Bao, J., & Xie, H. J. (2019). Determinants of domestic tourism demand for Guilin. Journal of China Tourism Research, 15(1), 1-14.

- Bazargani, R. H. Z., & Kiliç, H. (2021). Tourism competitiveness and tourism sector performance: Empirical insights from new data. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 73-82.

- Bento, J. P. C. (2014). The determinants of international academic tourism demand in Europe. Tourism Economics, 20(3), 611-628.

- Buigut, S. (2018). Effect of terrorism on demand for tourism in Kenya: A comparative analysis. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 18(1), 28-37.

- Corne, A., & Peypoch, N. (2020). On the determinants of tourism performance. Annals of Tourism Research, 85, 103057.

- Cró, S., & Martins, A. M. (2020). Foreign Direct Investment in the tourism sector: The case of France. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100614.

- Czernek, K. (2017). Tourism features as determinants of knowledge transfer in the process of tourist cooperation. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(2), 204-220.

- de la Peña, M. R., Núñez-Serrano, J. A., Turrión, J., & Velázquez, F. J. (2019). A new tool for the analysis of the international competitiveness of tourist destinations based on performance. Journal of Travel Research, 58(2), 207-223.

- De Vita, G. (2014). The long-run impact of exchange rate regimes on international tourism flows. Tourism Management, 45, 226-233.

- Deng, T., & Hu, Y. (2019). Modelling China’s outbound tourist flow to the ‘Silk Road’: A spatial econometric approach. Tourism Economics, 25(8), 1167-1181.

- Dropsy, V., Montet, C., & Poirine, B. (2020). Tourism, insularity, and remoteness: A gravity-based approach. Tourism Economics, 26(5), 792-808.

- Durbarry, R. (2008). Tourism taxes: Implications for tourism demand in the UK. Review of Development Economics, 12(1), 21-36.

- Duro, J. A., & Turrion-Prats, J. (2019). Tourism seasonality worldwide. Tourism Management Perspectives, 31, 38-53.

- Eilat, Y., & Einav*, L. (2004). Determinants of international tourism: a three-dimensional panel data analysis. Applied Economics, 36(12), 1315-1327.

- Eryiğit, M., Kotil, E., & Eryiğit, R. (2010). Factors affecting international tourism flows to Turkey: A gravity model approach. Tourism Economics, 16(3), 585-595.

- Etzo, I., Massidda, C., & Piras, R. (2014). Migration and outbound tourism: Evidence from Italy. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 235-249.

- Farzanegan, M. R., Gholipour, H. F., Feizi, M., Nunkoo, R., & Andargoli, A. E. (2021). International tourism and outbreak of coronavirus (COVID-19): A cross-country analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 60(3), 687-692.

- Fernández, J. A. S., Azevedo, P. S., Martín, J. M. M., & Martín, J. A. R. (2020). Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in the countries most visited by international tourists: Proposal of a synthetic index. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100582.

- Fourie, J., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2011). The impact of mega-sport events on tourist arrivals. Tourism management, 32(6), 1364-1370.

- Fourie, J., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2013). The determinants of African tourism. Development Southern Africa, 30(3), 347-366.

- Fourie, J., Rosselló, J., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2015). Religion, religious diversity and tourism. Kyklos, 68(1), 51-64.

- Ghalia, T., Fidrmuc, J., Samargandi, N., & Sohag, K. (2019). Institutional quality, political risk and tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 32, 100576.

- Ghani, G. M. (2016). Tourist arrivals to Malaysia from Muslim countries. Tourism Management Perspectives, 20, 1-9.

- Ghosh, S. (2021). Inbound Australian tourism demand from Asia: a panel gravity model. Journal of Economic Studies, 48(7), 1388-1400.

- Ghosh, S. (2022). Modelling inbound international tourism demand in Australia: Lessons from the pandemics. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(1), 71-81.

- Giambona, F., & Grassini, L. (2020). Tourism attractiveness in Italy: Regional empirical evidence using a pairwise comparisons modelling approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(1), 26-41.

- Gidebo, H. B. (2021). Factors determining international tourist flow to tourism destinations: A systematic review. Journal of Hospitality Management and Tourism, 12(1), 9-17.5.

- Gil-Pareja, S., Llorca-Vivero, R., & Martínez-Serrano, J. A. (2007). The impact of embassies and consulates on tourism. Tourism Management, 28(2), 355-360.

- Groizard, J. L., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2018). The destruction of cultural heritage and international tourism: The case of the Arab countries. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 33, 285-292.

- Grosche, T., Rothlauf, F., & Heinzl, A. (2007). Gravity models for airline passenger volume estimation. Journal of Air Transport Management, 13(4), 175-183.

- Gutiérrez, A., & Miravet, D. (2016). The determinants of tourist use of public transport at the destination. Sustainability, 8(9), 908.

- Habibi, F. (2017). The determinants of inbound tourism to Malaysia: A panel data analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(9), 909-930.

- Harb, G., & Bassil, C. (2020). Gravity analysis of tourism flows and the ‘multilateral resistance to tourism’. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(6), 666-678.

- Karl, M. (2018). Risk and uncertainty in travel decision-making: Tourist and destination perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 57(1), 129-146.

- Khadaroo, J., & Seetanah, B. (2008). The role of transport infrastructure in international tourism development: A gravity model approach. Tourism management, 29(5), 831-840.

- Khalid, U., Okafor, L. E., & Aziz, N. (2020). Armed conflict, military expenditure and international tourism. Tourism Economics, 26(4), 555-577.

- Khalid, U., Okafor, L. E., & Sanusi, O. I. (2022). Exploring diverse sources of linguistic influence on international tourism flows. Journal of Travel Research, 61(3), 696-714.

- Khan, K., Su, C. W., Xiao, Y. D., Zhu, H., & Zhang, X. (2021). Trends in tourism under economic uncertainty. Tourism Economics, 27(4), 841-858.

- Khoshnevis Yazdi, S., & Khanalizadeh, B. (2017). Tourism demand: A panel data approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(8), 787-800.

- Kim, Y. R., Liu, A., Stienmetz, J., & Chen, Y. (2022). Visitor flow spillover effects on attraction demand: A spatial econometric model with multisource data. Tourism Management, 88, 104432.

- Li, K. X., Jin, M., & Shi, W. (2018). Tourism as an important impetus to promoting economic growth: A critical review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26, 135-142.

- Li, Z., Huo, T., Shao, Y., Zhao, Q., & Huo, M. (2022). Inbound tourism–a bibliometric review of SSCI articles (1993–2021). Tourism Review, 77(1), 322-338.

- Lim, C., Zhu, L., & Koo, T. T. (2019). Urban redevelopment and tourism growth: Relationship between tourism infrastructure and international visitor flows. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(2), 187-196.

- Lorde, T., Li, G., & Airey, D. (2016). Modeling Caribbean tourism demand: an augmented gravity approach. Journal of Travel Research, 55(7), 946-956.

- Majewska, J. (2015). Inter-regional agglomeration effects in tourism in Poland. Tourism Geographies, 17(3), 408-436.

- Marrocu, E., Paci, R., & Zara, A. (2015). Micro-economic determinants of tourist expenditure: A quantile regression approach. Tourism Management, 50, 13-30.

- Martins, L. F., Gan, Y., & Ferreira-Lopes, A. (2017). An empirical analysis of the influence of macroeconomic determinants on World tourism demand. Tourism management, 61, 248-260.

- Massidda, C., Etzo, I., & Piras, R. (2015). Migration and inbound tourism: an Italian perspective. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(12), 1152-1171.

- Morley, C., Rosselló, J., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2014). Gravity models for tourism demand: theory and use. Annals of tourism research, 48, 1-10.

- Muñoz, C., Álvarez, A., & Baños, J. F. (2023). Modelling the effect of weather on tourism: does it vary across seasons? Tourism Geographies, 25(1), 265-286.

- Nguyen, J., & Valadkhani, A. (2020). Dynamic responses of tourist arrivals in Australia to currency fluctuations. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 71-78.

- Okafor, L. E., Khalid, U., & Burzynska, K. (2022). The effect of migration on international tourism flows: the role of linguistic networks and common languages. Journal of Travel Research, 61(4), 818-836.

- Okafor, L. E., Khalid, U., & Then, T. (2018). Common unofficial language, development and international tourism. Tourism Management, 67, 127-138.

- Okafor, L. E., Tan, C. M., & Khalid, U. (2021). Does panda diplomacy promote Chinese outbound tourism flows?. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 49, 54-64.

- Paniagua, J., Peiró-Palomino, J., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2022). Does happiness drive tourism decisions?. Economic Modelling, 111, 105824.

- Panzera, E., de Graaff, T., & de Groot, H. L. (2021). European cultural heritage and tourism flows: The magnetic role of superstar World Heritage Sites. Papers in Regional Science, 100(1), 101-122.

- Park, Y. S. (2016). Determinants of Korean Outbound Tourism. Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 4(2), 92-98.

- Peng, B., Song, H., Crouch, G. I., & Witt, S. F. (2015). A meta-analysis of international tourism demand elasticities. Journal of Travel Research, 54(5), 611-633.

- Pham, T. D. (2020). Tourism productivity theory and measurement for policy implications: The case of Australia. Journal of Travel Research, 59(2), 247-266.

- Pham, T. D., Nghiem, S., & Dwyer, L. (2017). The determinants of Chinese visitors to Australia: A dynamic demand analysis. Tourism Management, 63, 268-276.

- Pompili, T., Pisati, M., & Lorenzini, E. (2019). Determinants of international tourist choices in Italian provinces: A joint demand–supply approach with spatial effects. Papers in Regional Science, 98(6), 2251-2273.

- Prideaux, B. (2005). Factors affecting bilateral tourism flows. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(3), 780-801.

- Provenzano, D. (2020). The migration–tourism nexus in the EU28. Tourism Economics, 26(8), 1374-1393.

- Provenzano, D., & Baggio, R. (2017). The contribution of human migration to tourism: The VFR travel between the EU 28 member states. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(4), 412-420.

- Rosselló, J., Becken, S., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2020). The effects of natural disasters on international tourism: A global analysis. Tourism management, 79, 104080.

- Rosselló-Nadal, J. (2014). How to evaluate the effects of climate change on tourism. Tourism Management, 42, 334-340.

- Rosselló-Nadal, J., & He, J. (2020). Tourist arrivals versus tourist expenditures in modeling tourism demand. Tourism Economics, 26(8), 1311-1326.

- Santana-Gallego, M., & Paniagua, J. (2022). Tourism and migration: Identifying the channels with gravity models. Tourism Economics, 28(2), 394-417.

- Santana-Gallego, M., Ledesma-Rodríguez, F. J., & Pérez-Rodríguez, J. V. (2016). International trade and tourism flows: An extension of the gravity model. Economic Modelling, 52, 1026-1033.

- Santeramo, F. G., & Morelli, M. (2016). Modelling tourism flows through gravity models: A quantile regression approach. Current issues in Tourism, 19(11), 1077-1083.

- Santos, A., & Cincera, M. (2018). Tourism demand, low cost carriers and European institutions: The case of Brussels. Journal of transport geography, 73, 163-171.

- Seetanah, B., Sannassee, R., & Rojid, S. (2015). The impact of relative prices on tourism demand for Mauritius: An empirical analysis. Development Southern Africa, 32(3), 363-376.

- Shafiullah, M., Okafor, L. E., & Khalid, U. (2019). Determinants of international tourism demand: Evidence from Australian states and territories. Tourism Economics, 25(2), 274-296.

- Sharma, P., & Nayak, J. K. (2019). Understanding memorable tourism experiences as the determinants of tourists' behaviour. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(4), 504-518.

- Smolčić Jurdana, D., & Soldić Frleta, D. (2017). Satisfaction as a determinant of tourist expenditure. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(7), 691-704.

- Solarin, S. A. (2014). Tourist arrivals and macroeconomic determinants of CO2 emissions in Malaysia. Anatolia, 25(2), 228-241.

- Takahashi, K. (2019). Tourism demand and migration nexus in Small Island Developing States (SIDS): applying the tourism demand model in the Pacific region. Island Studies Journal, 14(1), 163-173.

- Tavares, J. M., & Leitao, N. C. (2017). The determinants of international tourism demand for Brazil. Tourism Economics, 23(4), 834-845.

- Turrión-Prats, J., & Duro, J. A. (2018). Tourist seasonality and the role of markets. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 23-31.

- Ulucak, R., Yücel, A. G., & İlkay, S. Ç. (2020). Dynamics of tourism demand in Turkey: Panel data analysis using gravity model. Tourism Economics, 26(8), 1394-1414.

- Van De Vijver, E., Derudder, B., O’Connor, K., & Witlox, F. (2016). Shifting patterns and determinants of Asia-Pacific tourism to Australia, 1990–2010. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(12), 1357-1372.

- Velasquez, M. E. B., & Oh, J. (2013). What determines international tourist arrivals to Peru? A gravity approach. International Area Studies Review, 16(4), 357-369.

- Vietze, C. (2012). Cultural effects on inbound tourism into the USA: a gravity approach. Tourism Economics, 18(1), 121-138.

- Vítová, P., Harmáček, J., & Opršal, Z. (2019). Determinants of tourism flows in small island developing states (SIDS). Island studies journal, 14(2), 3-22.

- Waqas-Awan, A., Rosselló-Nadal, J., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2021). New insights into the role of personal income on international tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 60(4), 799-809.

- Xu, B., & Dong, D. (2020). Evaluating the impact of air pollution on China’s inbound tourism: A gravity model approach. Sustainability, 12(4), 1456.

- Xu, L., Wang, S., Li, J., Tang, L., & Shao, Y. (2019). Modelling international tourism flows to China: A panel data analysis with the gravity model. Tourism Economics, 25(7), 1047-1069.

- Yang, Y., & Wong, K. K. (2012). The influence of cultural distance on China inbound tourism flows: A panel data gravity model approach. Asian Geographer, 29(1), 21-37.

- Yang, Y., Liu, H., & Li, X. (2019). The world is flatter? Examining the relationship between cultural distance and international tourist flows. Journal of Travel Research, 58(2), 224-240.

- Yerdelen Tatoglu, F., & Gul, H. (2020). Analysis of tourism demand using a multi-dimensional panel gravity model. Tourism Review, 75(2), 433-447.

- Zhang, Y., & Zhang, A. (2016). Determinants of air passenger flows in China and gravity model: deregulation, LCCs, and high-speed rail. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy (JTEP), 50(3), 287-303.

- Zhang, Y., Li, X., & Wu, T. (2019). The impacts of cultural values on bilateral international tourist flows: A panel data gravity model. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(8), 967-981.

- Zhu, L., Lim, C., Xie, W., & Wu, Y. (2018). Modelling tourist flow association for tourism demand forecasting. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(8), 902-916.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).