1. Introduction

Campaigns to support health care in family practice situations often take the form of communicative intervention (Alwell & Cobb, 2009; Chinn, 2017; Dodd, 2017; Karamidehkordi et al., 2021). A communicative intervention is an attempt to intervene or address a health disparity by generating new possibilities for action through dialogue and discourse (Barbour et al., 2018). As Krebs and Dutta illustrate, the terms communicative intervention in a health context can describe a variety of project models (Dutta & Kreps, 2013). Two well studied contrasting models of communicative intervention are the commercial and the social-marketing model (Andreasen, 2012; French et al., 2009; Nowak et al., 2015; Wood, 2008). The commercial model (or promotional approach) (Byerley, 2021) emphasizes a rational theory of knowledge, using an informative approach to communication, and designing messages for a one-way transfer of expert knowledge. In contrast, the social-marketing model or cultural approach emphasizes an individualized, narrative theory of knowledge, using a strategic approach to communication, and designing messages collaboratively with trusted speakers. Which is more effective?

In a 2021 study of interventions to address vaccine hesitancy, Byerley studied examples of the commercial and social-marketing approaches (Attwell & Freeman, 2015; Gordon et al., 2006; Schoeppe et al., 2017) to determine the effectiveness of the approaches in situations where communicative intervention (CI) was used to encourage the clinical practice of vaccination. Examining 25 studies using one or the other approach primarily, Byerley found evidence that studies using the social-marketing approach “...are far more likely to be successful than those that display attributes of the promotional approach (Byerley, 2021, p. 29).” The present study builds on Byerley’s work by attempting to answer the question, “Why are social-marketing public health campaigns successful?” by analyzing communicative evidence: texts, records, documentation, and participant consensus. The assumption is that if community conversations are to be the medium of diffusion of information about the expert-based health mitigation, then the evidence of that would be found in the recorded conversations and discussions of those participating in the intervention. The intervention topic in this case study is a medical approach to alcohol use disorder (AUD). We hope to show both how and why social-marketing techniques can stimulate community awareness of the intervention topic so that, again in this case, AUD treatment in family-practice settings can have a more lasting, sustained effect.

The setting of the intervention (a rural community in British Columbia) had been studied earlier to determine the possible causes of the lack of uptake of medical AUD treatment (Szelest et al., 2021). Evidence of the efficacy of the medical intervention had been presented to the family-practice community previously (Our Story, n.d.) and an initial rise in treatment was confirmed. However, researchers found that, in the long run, the effect of the informative approach diminished over time. “The findings confirm that presenting to prescribing providers first enables system change and presenting to non-prescribing personnel ensures a more supportive cultural change (Szelest et al., 2021, p. 288).” They further note that:

Sustainability is a key consideration in improvement projects. Although the current study indicates that system change is possible, additional investigation of the mechanism of this change would provide an in-depth understanding and provide insight into key criteria needed to sustain this change (p. 288). [Italics added.]

In health promotion, the phenomenon of positive effects in the short term but dissipating effects in the long term has been noted by researchers (Gordon et al., 2006, p. 30). Acting on the recommendation of Szelest et al. the organization conducting the

additional intervention (the Canadian Alcohol Use Disorder Society (

www.cauds.org), formed a partnership with academic communications researchers to investigate pathways for developing sustainable system change in the community. The project was appealing to this expertise-driven organization because it held the promise to mitigate the lack of community support and awareness of the medical AUD solution. Working with academic researchers in a participatory-action mode also held the promise of developing a model for replicating the intervention in other communities. For the researchers, the project held the possibility of identifying insights into communicative intervention through communicative analysis (Fedorova, 2019) as the evaluation approach.

The analytical approach used in this study is communicative analysis. Communicative analysis is defined as the study of communicative behaviour in texts to measure the achievement of goals and objectives in a social context (Rigotti & Rocci, 2006; Wallat & Piazza, 1997). Similar to discourse analysis, communicative analysis sees texts (meeting minutes, organizational records, conversations) as embodiments of information flow and connectivity of people involved in social change. Studies of information flow (Moro et al., 2016; Wu & Huang, 2019) typically trace the diffusion of content, expert processes, or ideas in social or health contexts. Studies of connectivity (Croucher, 2011; Murillo-Sandoval et al., 2016; Trickett & Beehler, 2017) trace the building of networks, groups, and coalitions within social contexts. This study looks at both these key characteristics of communication in a social-marketing, participatory health intervention campaign.

The purpose of this article is to describe the evaluation of the health intervention campaign, both in the quality of its activities and the degree of community engagement they achieved. We employ well known methods of formative and summative evaluation using communication artifacts: evaluation reports and meeting minutes. This article will demonstrate how a communicative analysis can help researchers in communication theory, health intervention, public health, and family practice understand the role of social marketing in fostering community support for clinical interventions.

Characteristics of the study

According to Dutta and Kreps there are five types of communicative interventions in health: message-based, training-based, technology-based, policy-based, and community-based (Dutta & Kreps, 2013, pp. 5–6). Community-based interventions can be of two types: expert-driven, in which participation, “serves as a mechanism for diffusing the expert-driven solutions,” (p. 8) and community-driven, or shaped by grass-roots community members. The present study is about a group consisting of the partnership of 1) a society dedicated to mitigating alcohol use disorder (the “experts” in prescription and nursing for AUD) 2) a grass-roots organization, dedicated to improving rural health care in the community and 3) a regional health authority whose goal was to decrease community stigma around AUD. Both these types of groups exist in many health jurisdictions. We considered this intervention as expert-led because the health society (CAUDS) initiated the contact, organized the project, and functioned as an administrative sponsor.

The project timeline covers a period of one year and focuses on the partnership working group, which consisted of members from the following areas:

The medical treatment for AUD in family-practice settings and the discipline of organizational improvement

Communication facilitation and academic research

Community health, grass-roots advocacy

Community engagement programming by a regional health authority.

Table 1 shows the activities that the group participated in over the year:

A presentation at the junior high school wellness conference

A social-media presence

A presentation to the town council

A public event featuring alcohol-free cocktails

A showing and discussion of a documentary film about alcohol use disorder

Planning to set up an AUD group with activities in the high school.

While all six activities occurred in the same community during the same one-year time period, we focus this evaluation on three of them (the school presentation, the town council presentation, and the public event) because of their potential to engage decision-makers (educators, legislators, and public influencers) in the social ecology of the community (Trickett & Beehler, 2017). The socio-ecological model, described in the next section, provides a framework that justifies our focus on these three activities.

2. Literature Review

This review briefly describes the four scholarly conversations that guide the work. The first is the scholarly conversation in community engagement, followed by a discussion of research on the data-modeling approach used, and the situational-influence model used.

2.1. Community Engagement

The scholarly backdrop for this study is the research conversation surrounding community engagement over the last 20 years. Over that time, models have focused increasingly on strategies for overcoming systemic barriers to health (Brunton et al., 2017; Dutta & Kreps, 2013) and on tailoring approaches to specific communities, for example the mineral industry (Harvey & Brereton, 2005), Indigenous communities (Czaykowska-Higgins, 2009), community health (O’Mara-Eves et al., 2013), and research, education, and social care (Vaughn et al., 2018). Our study focuses on a health intervention in a rural community. It was assumed that the relationship between the community and the intervening health society was asymmetrical, in the sense that an awareness of medicines to treat alcohol use disorder was not widely known or acted upon in this community. For this study the researcher wanted both to participate in the intervention and also study the communicative artifacts (records of discussions) that it produced. The communicative analysis in this study focuses on informative and connective communication behaviors found in discussion data: records of meeting minutes collected and analyzed after the intervention. To facilitate this analysis, the discussion data was first structured or tagged using a framework of learning known as Epistemic Network Analysis. The following section briefly reviews these two important components of the study.

2.2. Communicative Analysis

As a basis for evaluating effectiveness of campaigns in social ecologies, we employ methods of communicative analysis. Communicative analysis is a broad term that refers to the methodical analysis of human social interaction through records of communicative behaviour (Borysov & Vasylieva, 2022; Charaudeau, 2002; Cooren, 2004; Wallat & Piazza, 1997). Communication theorists often refer to two characteristics of communicative behavior: information flow from one person or group to another; and networking, or the creation of webs of influence among persons. Communication both carries messages and it influences communities (Carey, 2007; Grabill & Simmons, 1998; Jones, 2013; Kawamoto et al., 2020). Communicative behaviour is recorded in a variety of text, voice, and social-media-related activity. In this paper we investigate whether organizational quality and effectiveness in health interventions can be traced by looking at textual evidence of information flow and networking (Cross et al., 2003; Kleinberg & Ligett, 2013; Nieves & Osorio, 2013).

Communicative analysis is how we measure the informative and connective dynamics of communication as they change over the period of the intervention. Our communicative analysis relies on two analysis frameworks. The Epistemic Learning Network framework illuminates the communication dynamics in the intervention working group meeting minutes, and the Socio-Ecological framework models the layered systems of influence of the activities and the group members.

2.3. Epistemic Network Analysis Model

Epistemic Network Analysis is a framework for modeling communicative behaviors and learning networks in groups. A number of frameworks or models for understanding communication networks in groups have been described in the literature (Butscher et al., 2024; Emmert, 1989; Koopmans et al., 2011; E. W. J. Lee et al., 2017; Pettigrew et al., 2001). Epistemic Network Analysis (ENA) is one such heuristic (Shaffer et al., 2016, 2017). Epistemic Network Analysis, is a theory-based approach to learning analytics. It contrasts with a data-driven approach, but can be used in tandem or alignment with data-driven analysis. The scholars who developed ENA make the point that the data can not speak for themselves, and that a theoretical approach plays a critical role in analysis. As the authors state, “An epistemic frame is thus revealed by the actions and interactions of an individual engaged in authentic tasks (or simulations of authentic tasks) (Shaffer et al., 2017, p. 175).”

Epistemic Network Analysis is based on the concept that textual interactions about specific events are related to one another for that event but not related to other events. In other words, language surrounding one event is characteristic of that event and not necessarily other events. Following this reasoning, textual interactions for one event “represent meaningful cognitive connections among the epistemic frame elements” of the event itself (Shaffer et al., 2017, p. 178). The epistemic frame elements are flexible and have been applied in various arenas, including surgeons’ communication during operating procedures and concepts in historical records (Shaffer et al., 2016, p. 10). Shaffer et al. argue that these framing elements represent “isolated elements of experiential knowledge” and through their semantic connections, create a “pattern of associations among knowledge, skills, habits of mind, and other cognitive elements that characterize communities of practice (Shaffer et al., 2016, p. 11; Wegner, 2004).”

A key result in ENA is a “co-occurrence.” A co-occurrence is a measurement of an association between concepts (Ba et al., 2023; Blanchet et al., 2020; Gries & Durrant, 2020). The term co-occurrence is used in corpus linguistics to indicate terms that appear together or near one another. It asserts that when they correlate in frequency they also imply a “semantic or functional similarity (Gries & Durrant, 2020, p. 142).” In ENA a co-occurrence is taken to suggest a learning relationship or to indicate a similarity of thinking.

This article focuses on the communicative actions of individuals engaged in planning and conducting of activities intended to stimulate information flow and interconnected understandings of the medical treatment of AUD in family practice settings. Analyzing the communication surrounding the school presentation, the town council presentation, and the public event can provide evidence of information flow and engagement: potentially the evidence needed to argue for the overall quality and effectiveness of the intervention.

2.4. The Socio-Ecological Model

A number of models for social environments have been developed and are being used in the systemic structuring of ecologies for health interventions (O’Mara-Eves et al., 2013; Pinto et al., 2021; Spain et al., 2017). Our study was designed using the socio-ecological model of health ecologies (B. C. Lee et al., 2017; McMurray, 2006; Schmitz, 2016). The

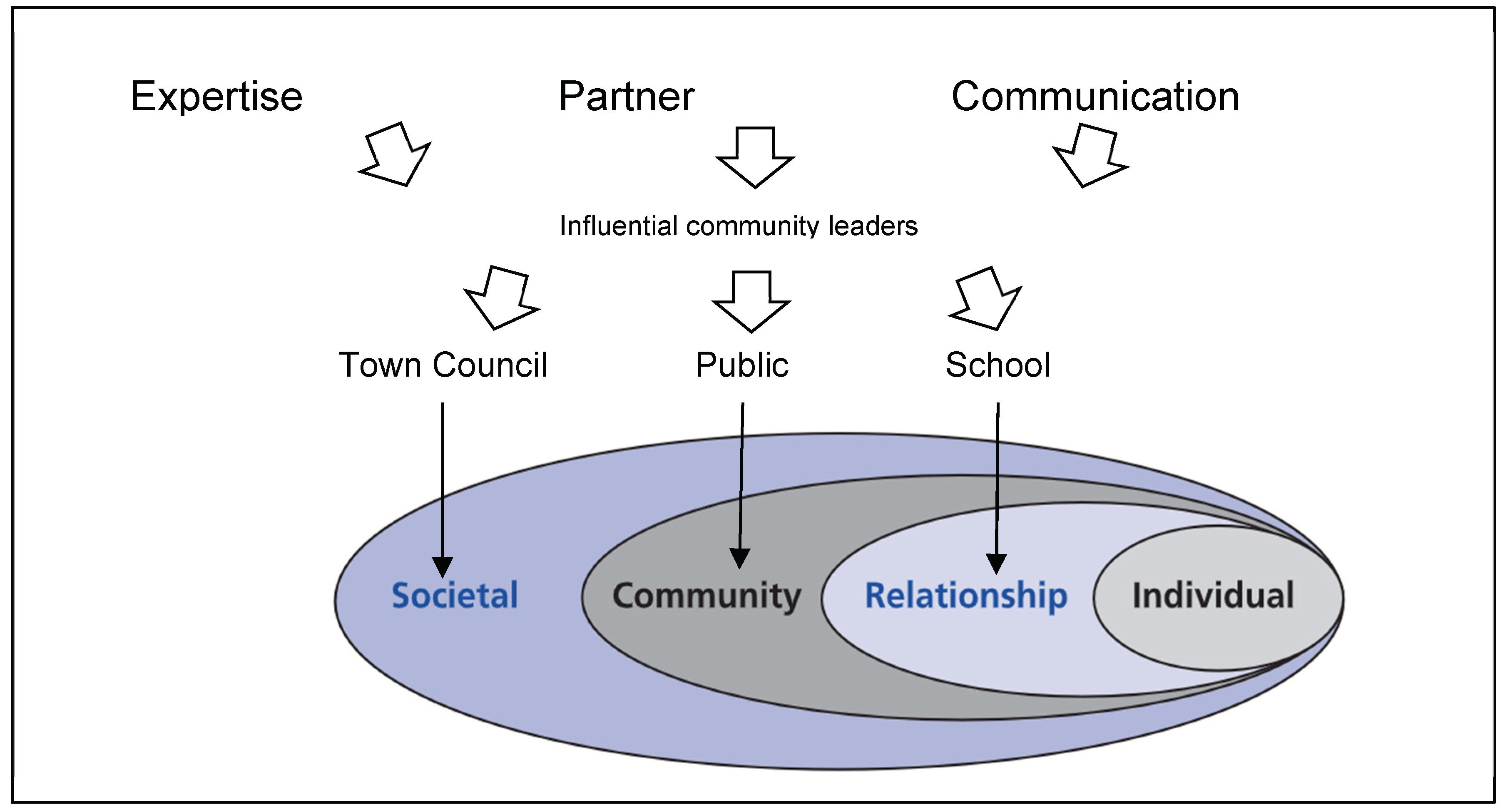

socio-ecological model situates communicative behavior within a systemic view of the health ecology or the social environment surrounding the stakeholding individual (Aldoory et al., 2022; Aldoory & Toth, 2021; Liska & Cronkhite, 1995; Murillo-Sandoval et al., 2016). According to Bronfenbrenner, this theory (see

Figure 1) is a “...conceptual framework for analyzing the layers of the environment that have a formative influence on children (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).” Apart from children, the model has also been applied to health and violence (Krug et al., 2002), sexual abuse reduction (Goldman & Padayachi, 1997), public relations (Aldoory & Toth, 2021) and other areas. The application to community health (Kousoulis & Goldie, 2021; B. C. Lee et al., 2017; McMurray, 2006) was of interest to us in this complex partnership study. As Goodman notes, “The literature on social ecology emphasizes the need for multiple intervention strategies targeted at multiple social strata (Goodman et al., 1996, p. 35).”

Our study focuses on evaluating three activities, each one situated in one of the three ecological strata of the model: relationship (as participants in the school system), community (as members of the public), and societal (as participants in the municipal government). We argue that evidence of information transfer and network building in these three areas can indicate the success of the intervention. But the method is not simple. The project strategy, worked out ahead of time, was to energize and engage with community leaders. If community leaders could engage with expertise leaders, health program leaders, and communication leaders (researchers) in the working group, then flow and influence would occur through the community leaders to the community, naturally, as expected given the social-marketing campaign model being employed. As

Scheme 1 shows, the community engagement intervention was conducted along the channels through which it was intended to exert influence. The evaluative analysis in this paper was also conducted on evidence found in these channels of information and influence.

3. Methods and Methods

As Butterfoss and others argue, the process of evaluation of community projects can take a number of forms: stakeholder-based, democratic and empowerment-based, and participatory action-based (Butterfoss et al., 2001). We formed our evaluation process around participatory action. We followed the approach of Goodman et al. of using two evaluative methods: a

formative evaluation to measure quality of events and a

summative evaluation to measure the effectiveness of the intervention as a whole (Goodman et al., 1994, 1996; Taras, 2008). According to Kealy and others, formative methods support ongoing processes of improvement, while summative methods measure competence or mastery (Kealey, 2010; Smith & Brandenburg, 2008). This two-pronged approach is appropriate because the intervention was a new type of initiative for the Canadian Alcohol Use Disorder Society. Their objective was to conduct successful community engagement activities but also to understand the group informational and networking dynamics so they could replicate the success in future interventions. They needed to evaluate and learn from each activity (formatively), but also evaluate and learn from the year-long project itself (summatively).

Table 1 outlines the differences between formative and summative evaluation.

Formative Evaluation Method

In formative evaluation, the practice of the lead organization was to use qualitative and quantitative data sources to document quality. These sources included: attendance counts, social media postings, testimonials and conversations, and observations by family-practice clinicians. These data sources document the perception of quality of the social-marketing activities. Members of the lead organization had a background in improvement science (Bhat & Bhat, 2019; Jagosh et al., 2015) which made this collaborative method a natural fit.The lead organization used consensus evaluation meetings (Anders & Batchelder, 2012; Bova, 2022; Carlsen et al., 2000) to gather stakeholder feedback about activities and also about technology used. The formative observations and results were first circulated among group participants for review and additional consultation, and then compiled into a formal report. That report included comments about targeted activities, a section on lessons learned, and a section on recommendations.

The lead organization also used a software platform called AimiHub to manage and record organizational improvement (AimiHub - Strategic Improvement Management Platform, n.d.). The platform facilitated management of goals and objectives using team charters, meeting scheduling, sponsor reports, and data analysis with visualization tools. Evidence of quality was collected in this platform according to a “plan-do-study-act” (PDSA) model for each activity. This platform allowed the sponsor organization to track the workflow of the project and was a reliable repository of observations when it came time for the formative evaluation report.

Using these qualitative and quantitative methods allowed the project to unfold naturally using the energy, contacts, networks, and organizational structures that were familiar to the participants. Extensive work went into preparing for a community-wide day-long, kick-off workshop to ensure that participants represented recognized community leaders in the three zones of socio-ecological influence. The workshop facilitators used appreciative inquiry procedures to identify program objectives that built on community strengths, resilience, and history (Carter et al., 2007; Sandu, 2011; Whitney & Trosten-Bloom, 2010). After the workshop the working group was formed (Cowan et al., 2022; Walzer et al., 2016). The working group began with 12 community leaders in health, education, civil service, social service agencies and police. Early in the year this larger group was reduced to a working group of about 6 to 8 persons consisting of community leaders, representatives of the provincial health region, engagement managers from the sponsor or lead organization, and the participatory researchers. The working group met regularly, kept minutes, and organized the intervention activities. A research assistant and an intern with community connections assisted with planning, surveys, data analysis, and reporting. As the year drew to a close, the formative evaluation was done in meetings of the working group.

Summative Evaluation Method

The summative evaluation focuses on information about engagement activity as represented in data from the meeting minutes of this working group. The summative evaluation process aims to determine the value or effectiveness of a project in order to “form a decision-making basis about [the project]” (Smith & Brandenburg, 2008).” The anticipated decision about the project was whether or not to repeat the intervention based on evidence of engagement with the community. Unlike the formative evaluation, the summative evaluation does not focus on ways to improve the activities, but on whether the activities engaged with important sectors of the community and achieved the goals of the lead or expert organization.

Summative evaluation attempts to document engagement by looking beyond the informative to the networking dynamics of the working group as recorded in the meeting minutes. Seen through a communicative lens, meeting minutes may be able to show whether messages about the medical treatment for alcohol use disorder engaged with the community. The analysis of meeting minutes has been done in previous research (Nagao et al., 2015; Tomobe & Nagao, 2007). Known as “discussion mining” the process of extracting summative information from minutes follows a process of semantic annotation of relevant discussion content (Nagao, 2007; Nagao et al., 2005). In our case we wanted to annotate content that connects the intervention activities with the community. To accomplish this, the summative evaluation used Epistemic Network Analysis (Shaffer et al., 2017) to identify relationships among the knowledge or semantic categories in the working group as represented by the various members names. In discussions of the ENA, evidence of these relationships is called a “co-occurrence.” Expressed as an axiom we can assert that: The co-occurrence of shared knowledge in the minutes of the working group may be taken as positive evidence that the intervention was a success and merited replication. In the next section we discuss the process of semantic annotation and text analysis.

Text Analysis

The text analysis for the summative evaluation focused on the text of these meetings, collected over the course of a year (in this case from January to November). The partnership working group conducted 18 planning and debriefing meetings. The text of the minutes were processed by removing headings, dates, and locale identifying information (Huberman & Miles, 2002). They were then assembled into a text-only corpus containing 18 files (Cheng & Others, 2013; Egbert & Schnur, 2018; Mautner, 2009; Orpin, 2005). Names in attendance lists were replaced by participant roles according to the semantic categories identified by the Epistemic Network Analysis heuristics. The cleaned files were imported into the data analysis platform Voyant Tools (Voyant Tools, n.d.) for analysis. Voyant Tools is a web-based text analysis and visualization platform that allows the researcher to explore features of word frequency, concordances of terms, word clouds, and topic modeling. The platform is useful for identifying known characteristics of text, associated with specific words or word frequencies, in a corpus consisting of collections of text files over time.

The Epistemic Network Analysis heuristic breaks the situational data into categories that contain information about, 1) a set of objects or concepts, 2) the ways concepts relate to one another, and 3) a series of time periods based on 4) evidence about the relations between the objects (Shaffer et al., 2016, p. 23). In our case these “objects” were identified with the persons who participated in the working group. The names (in lists, speaking designations, and task assignments) were seen as participation indicators (Dringus & Ellis, 2005, p. 149).

As mentioned earlier, the analysis was done on a corpus of 18 text-only files from the meetings over the period from January to November. The minutes in raw form contained the names of the persons attending the meetings and then the names of persons speaking and assigned to roles or tasks. To anonymize the data the name of the community was substituted, across the 18 files, with the term [locale]. Once this was done the names of persons in the files were substituted with the concepts or roles identified in the Epistemic Network Analysis heuristic discussed above.

Figure 1 shows an example from one set of minutes showing how the names of persons were substituted with ENA concepts or roles.

Text processing was carried out using Voyant Tools. The minutes corpus was loaded into the platform and a line and stacked bar graph, using the Trends tool, was created showing the frequency of the terms or participation indicators in each of the minutes texts. Term frequencies were also calculated for the minutes surrounding the three activities to obtain graphs showing the mix of participation indicators before and after each activity. The results from the formative and summative analysis are discussed in the next section.

4. Results

The following section presents the findings of the communicative analysis, first with examples from the formative evaluation, and second with the analytical categories of the ENA analysis and the automated text analysis that comprise the summative evaluation.

4.1. Formative Evaluation Results

The activities of the intervention were analyzed by the principles of formative assessment (Black & Wiliam, 2009, p. 8). The working group participants wrote a comprehensive internal evaluation report providing an in-depth analysis of the Community Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) activities implemented in the community. The report identified six activities undertaken by the working group (see

Table 2). For each activity a measure was identified in terms of increases in awareness and information flow, increases in community networking. Outcomes were recorded during a consensus meeting held late in the year.

The evaluation records evidence of quality: successes in raising awareness, involving the community, and destigmatizing AUD, with valuable insights from stakeholders, clinicians, and People with Lived Experience (PWLE). The report highlights key lessons learned, emphasizing the significance of effective messaging, community leadership, and ongoing support for the medical intervention for AUD. Informed by these lessons, strategic recommendations are presented, informing future actions to further strengthen AUD activities and cultivate a positive and supportive community environment. The insights derived from the evaluation contribute to the group discourse on addressing AUD, fostering positive change, and nurturing a culture of understanding and empathy in the community.

In this article we sought further insights into the formative evaluation results by looking at them through a communicative lens. The following section discusses this analysis.

4.1.1. Communicative Dimensions of Formative Evaluation

As

Table 3 shows, the formative evaluation was a communication event in itself. It created a lively record of observations, comments, and other evidence that was used to adjust the approaches to intervention activities by the expert organization.

With foundations in improvement science (Crow, 2024; Wandersman et al., 2000) and other academic and professional disciplines, this evaluation provides narrative-based improvement data to inform future interventions.

Table 4 shows three examples of improvement information obtained from formative evaluation.

4.1.2. Summary of Formative Findings

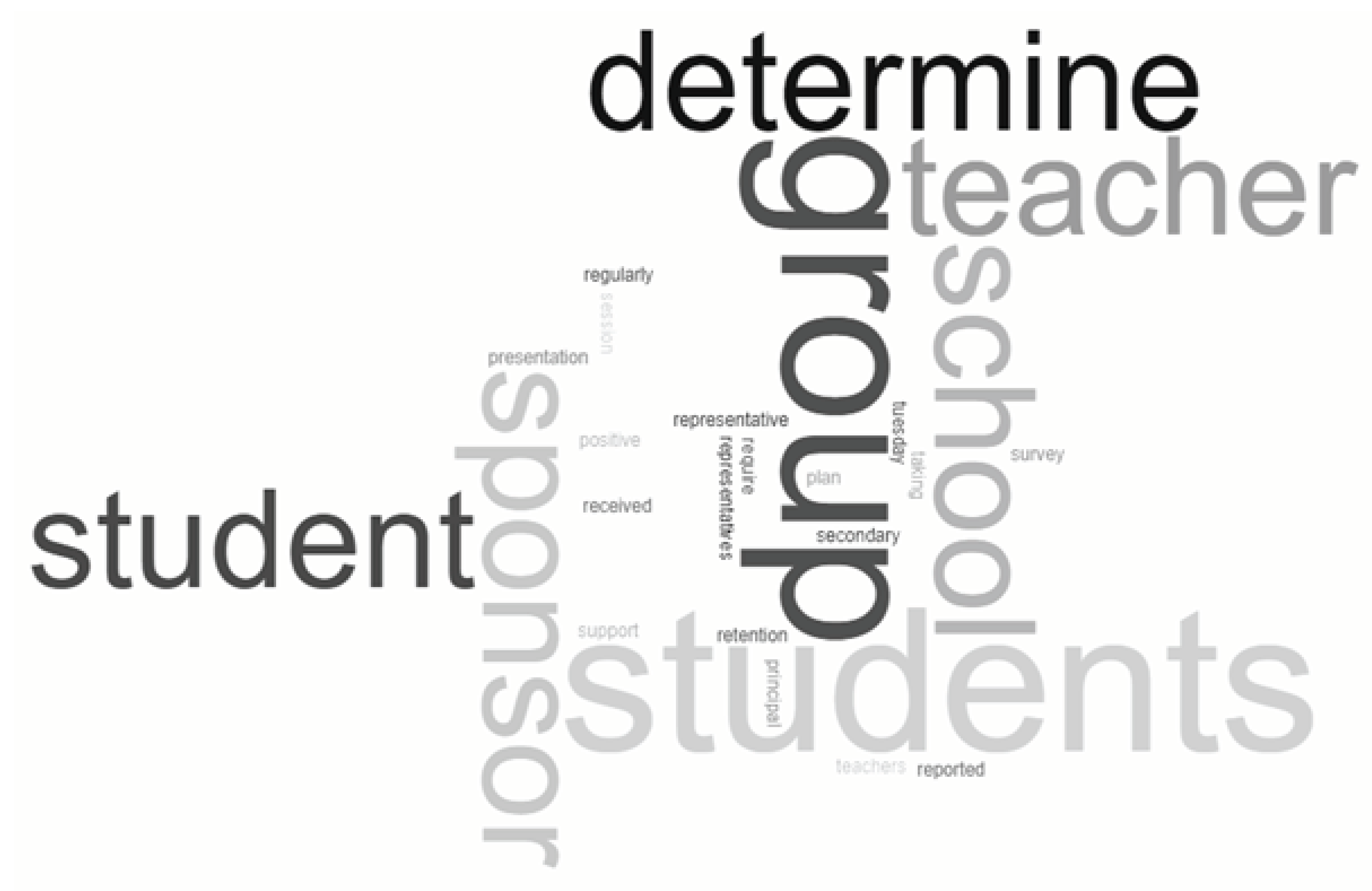

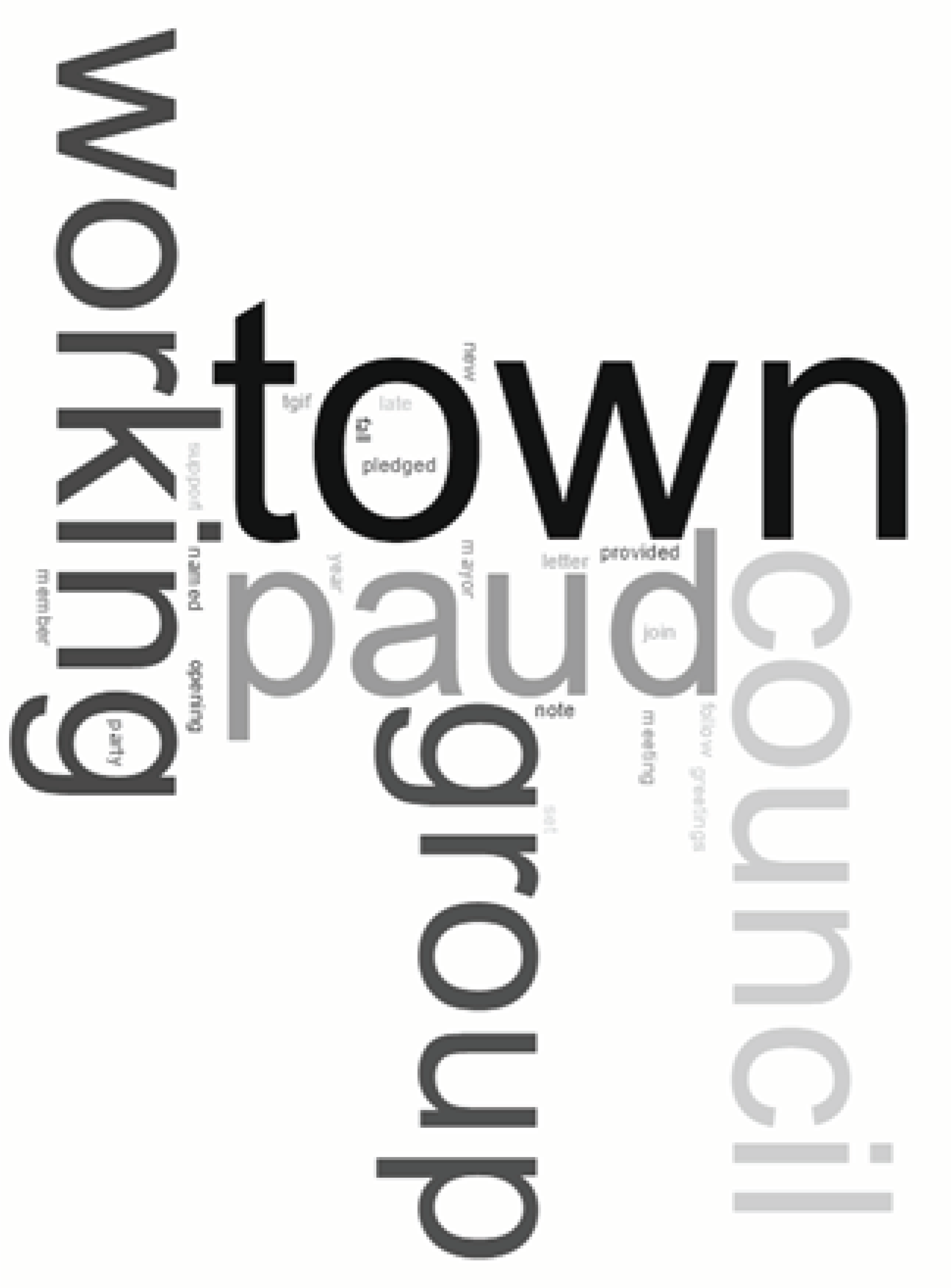

The need to identify best practices for the future is challenging because of the complexity, data uncertainties, and ever-changing nature of intervention activities (Johnson et al., 2015; Kapucu, 2006). As a data collection task, it results in a body of authentic data (in text form) that can nourish discussions about subsequent interventions by the individuals who are most familiar with the situation: the working group members who participated in meetings, discussions, email trails, and presentations. As such, it is evaluation information that stands for itself (Diller & Phelps, 2008; Gunasekara & Gerts, 2017; Hanifah & Irambona, 2019; Rapchak et al., 2015; Whitlock & Nanavati, 2013). Known as

authentic assessment, it is based on the idea that, because they are artifacts, evaluative statements themselves are open for interpretation by future program planners. As an illustration of what a subsequent interpretation might look like,

Table 5 shows an example of three word-cloud analyses of the formative results focusing on the three key areas of anticipated community engagement.

However, because of their focus on specific activities of an intervention, formative evaluation statements tell us about pieces of the picture. To obtain a comprehensive picture of engagement a complementary summative evaluation method is needed.

4.2. Summative Evaluation

Unlike the formative evaluation, the summative evaluation asks the question “how effective was it, or did it meet our needs (Smith & Brandenburg, 2008, p. 35)?” Our summative evaluation looks for evidence of effectiveness in existing conversations: the meeting minutes of the working group. As discussed above, this process followed two steps: first we applied the heuristic of the Epistemic Network Analysis (ENA) to identify the communicative elements; and second we analyzed the patterns of communicative elements for evidence of engagement.

4.2.1. Epistemic Network Analysis Findings

Our analysis now turns to the group itself and the communicative dynamics found in the meeting minutes corpus. The following results of the Epistemic Network Analysis heuristic represents the case as a model learning system consisting of: objects, relations, stanzas, and evidence. Definitions of these terms come from Shaffer et al. (Shaffer et al., 2016). For our analysis we identified objects, relations, and stanzas or intervals.

Objects

Objects are things or people or concepts to be modeled. In our case this would be the roles and expertise of the members of the AUD working group. The group consisted of four “objects” or persons with expertise and the role these areas played in the group. The following list discusses these persons according to their communicative roles.

The next analysis looks at these objects and their relations to one another in terms of learning.

Relations

Relations are associations between objects, connections to social ties that link one object to another (Shaffer et al., 2016, p. 24). These relations or functional groupings of persons can be identified by the analyst for the sake of modeling the overall goal of carrying out an effective social-marketing intervention. While all persons performed both functions at the same time, for our analysis we chose to align the relations among the objects along the lines of their primary communicative function: to inform (i. e. fill a gap of expertise between mitigative and non-mitigative behaviour) or to connect as part of a growing network of influence.

Table 7 represents the analysis using the

objects and

relations aspects of ENA. It shows how group members can be assigned by their roles or “relations” to the diffusion of information (“informative”) or the shaping of a network of trust in the community (“connective”). These two relations were chosen because they are the two recognized roles of communicative behaviour (Carey, 2007). For this reason, the “communication” object was seen as having a “connective” relation in this case because it helped keep the group together and was not a channel of the health mitigation information. That role, or “relation” was assigned to the “expert”. In a situation where an asymmetrical relationship exists, such as was the case in the community

before the intervention, the ability to identify how expert information flows and network connections are built can guide and enrich our summative analysis. Because CAUDS was the intervention sponsor and organizer (emphasized below), their voices and messages were seen as the primary informational content being infused into the community networks.

Evidence

Evidence, in the epistemic network model, refers to specific elements of the data that can be used to identify the relations being modeled. Evidence was available from a number of sources, but our focus was on the meeting minutes. The minutes were taken by the research team and others during the entire project. The next analysis looks at the relations of the objects and relations over time or in periods called stanzas.

Stanzas

Stanzas are units of time, stages in a process, or any way of identifying a unit in the data for quantifying discrete relations among objects. The AUD working group conducted a number of meetings and events during the year (November 2022 to November 2023.) During this time, members communicated externally with friends, restaurant owners, employers, colleagues, educators, police officers, researchers, and numerous members of the public. You can not conduct a visible health campaign in a small town without communicating about it to a variety of audiences. This communication was both informative (giving talks, sharing brochures, posting on Facebook) and also connective (aligning with persons about community goals, planning with others, proposing for research funding, and soliciting donations.) The group also communicated internally to share information (meeting schedules, documents, clarifications) and to connect (define terms of reference, clarify roles, and show kindness and consideration to fellow human beings.) To identify stanzas, however, requires a parsing of this body of discussion activity into meaningful segments.

For the sake of identifying these segments in the overall process, we focus on three primary events that the group conducted and which, if it did nothing else, represent the major communicative efforts of the year, in the following order.

The school presentation. This event was conducted in February 2023 as part of a secondary school educational event focusing on “wellness.” The activity involved going to the school and making presentations about alcohol and alcohol-use disorder to students and teachers. It had repercussions throughout the project in terms of following up, evaluating, and planning for the future.

The presentation to the Town Council. This event occurred on April 2023l. This presentation defined the AUD intervention project and asked for cooperation from the town council.

The “Thank Goodness it’s Free (T. G. I. F.)” event. This was the most public of the events and it took place in a public square in August 2023.

While the group participated in other events during the year (such as a volunteer fair and the screening of an AUD documentary), the events with the potential to engage the socio-ecological environment were: the presentation in the school, the presentation at a meeting of the Town Council, and the alcohol-free event held in a public setting. These events engaged friends and families, government, and the stakeholder community. These are the sectors in which decisions to support the medical treatment of AUD in a clinical setting needs to be made, and where [expert] and [partner] messaging needs to be used. So, while the group achieved a number of outcomes during the year, evaluating the networking and information sharing of these three events will serve as focus points for summative evaluation using automated text analysis tools.

Summary of ENA Analysis

According to Shaffer, Collier and Ruis, “Segmenting data into stanzas thus makes it possible to accurately model the relations between objects based on evidence in the data (Shaffer et al., 2016, p. 24).” This process of segmenting data into stanzas suggests that a communicative analysis of the Alcohol Use Disorder working group can productively use the element definitions above (objects, relations, stanzas, and evidence) to create a rich representation of the communicative intervention. Communication analysis focusing on informative and connective communication characteristics surrounding these events may yield evidence of success for the summative evaluation.

4.2.2. Data Representations

Results of the communicative analysis of the working group are presented in three areas: the term frequency analysis, ENA visualization and network analysis.

ENA Visualization

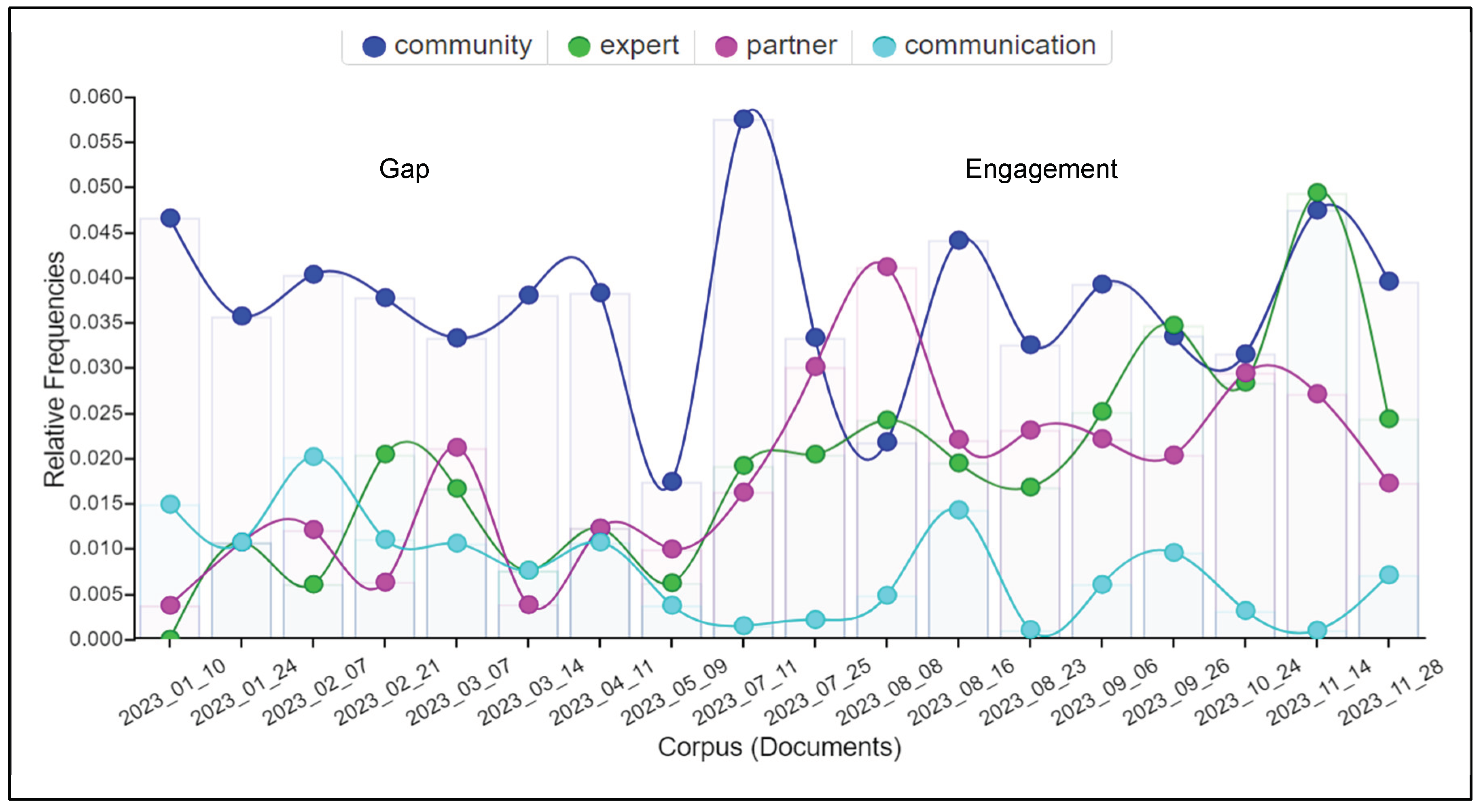

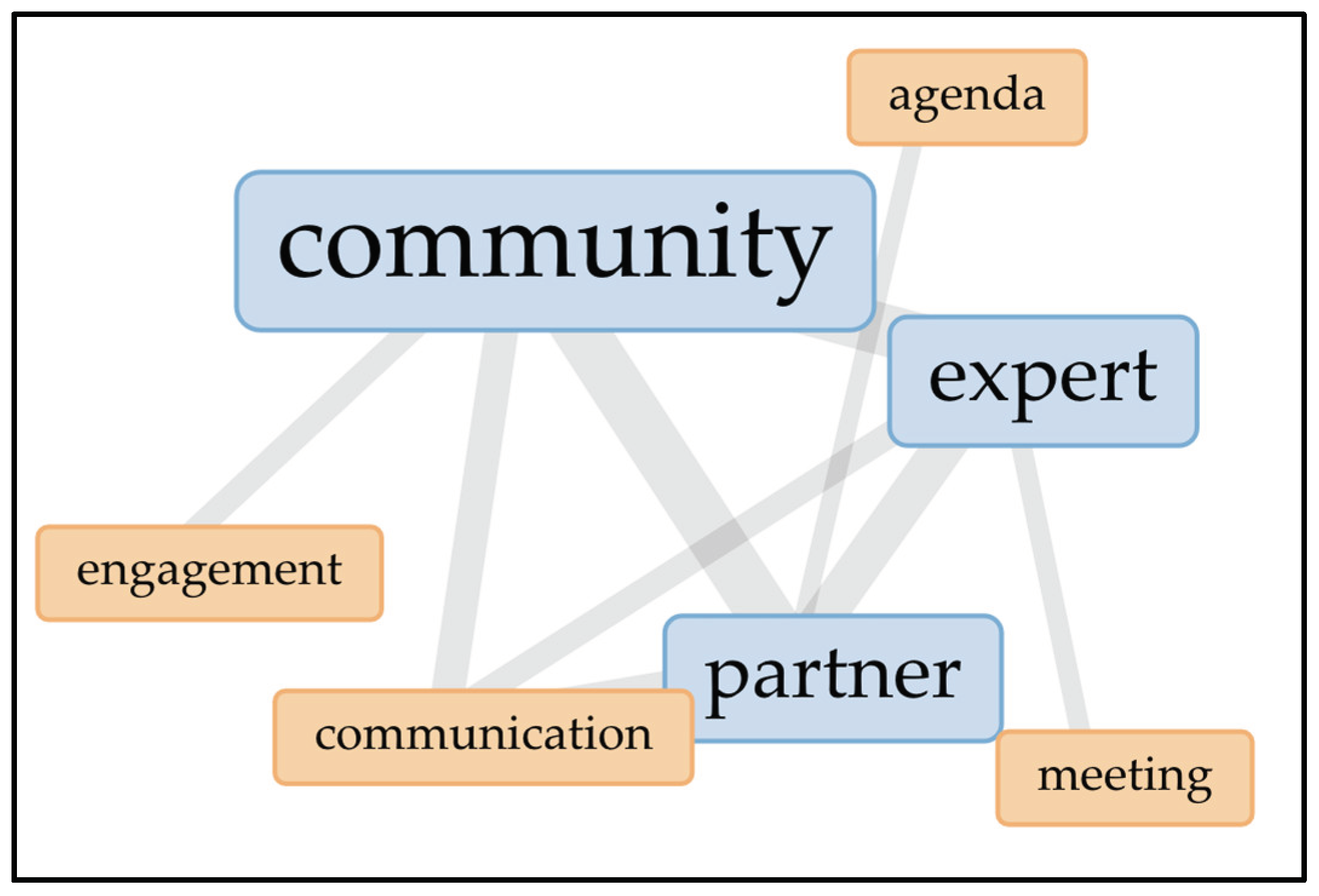

The visualization in

Figure 2 shows graphically the frequency of participation indicators aligned with the four elements of the epistemic analysis described above. A number of trends might be discernible from this graph.

The graph in

Figure 2 shows an upward trend in the frequency of the voices of the [expert] organization and the [partner] representatives.

The presence of the spokespersons for [communication] and the [community] remained steady during the year.

Frequency of spokespersons for the [community] was higher all year long (despite some one-off fluctuations) at between 35% and 45%.

Frequency of spokespersons for [communication] and research remained lower (under 20%).

Frequency of spokespersons for the [expert] organization and the [partner] organization rose from under 20% to between 25% and 30%.

In terms of relations, these trends represent communicative relationships in which information (about medical treatments for AUD) was coexistent with collective impact (Kania et al., 2014; Springett, 2017). Put in other terms, the messaging of the expert organization seems to have adjusted over time in the project showing more co-occurrence with that of the community. In this way, a co-occurrence of objects, which we have in this case identified with the informational and connective characteristics of communication, may reveal instances where the participants in the meeting reached a shared meaning. If that is so, then areas of co-occurrence--where the expert, partner, and community speakers appear more convergent--seem to appear later in the year. In some areas of the graph the expert and the community appear to occupy a similar discursive space.

Pre- and Post-Event Analysis

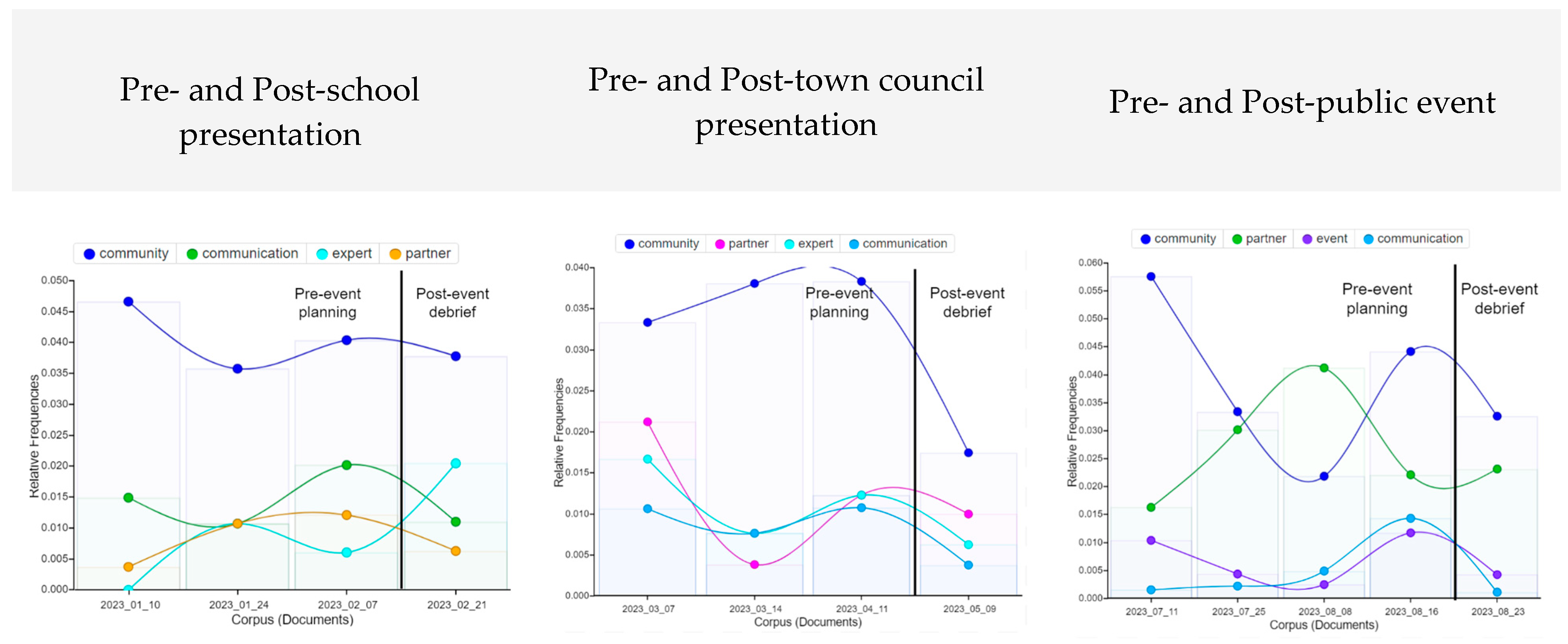

The Epistemic Network Analysis that resulted in our ability to measure the frequency of semantic influence (as indicated by the frequency that semantic objects occur) also allows us to examine the discourse surrounding each of the three socio-ecologically distinct activities (or stanzas) occurred.

Figure 3 shows term frequency charts for the three activities, each in distinct socio-ecological zones. Moreover, they represent the one or two planning meetings leading up to the event, and the debriefing meetings that the group typically held after the activity.

A number of patterns relating to this representation could be found. One pattern is that the discussion voices representing the community appear most frequently in all three charts. This may indicate that, in the beginning, or planning stage, of the activity, the community voices, representing the natural thought in the community before the intervention activity, occur frequently and in a different register than the voices of the expert and partner voices. However, the top line in all three graphs tends to lower in the debrief meeting (the last one in each of the graphs), putting it more at the frequency level of the other voices. Seen in terms of information flow and connectivity, the “informational” voices of the expert and partner grow closer to a co-occurrence with the community voices.

Network Analysis

The following image (

Figure 4) shows the connections among the elements of the meetings corpus and the number of connecting lines (based on proximity analysis) that they show. This graph was created using the Voyant Tools

Links tool (Sampsel, 2018). The thicker the connecting line the more frequent the association. From this diagram it appears that community, expert, and partner are the three key informative associations (the thicker connective lines or “edges” (Yan & Gregory, 2012)) formed in the working group. Communication (or the research element) was minimalized but remained important because it connected the community, partner, and expert objects.

The evidence here connects the expert, partner, and community, with strong ties, community being the most important or central in the network (Freeman, 1978; Johnson et al., 2015). As a representation of the meeting minutes data, the diagram indicates the formation of a network, one of the goals of the project and a characteristic of successful social-marketing campaigns.

5. Discussion

In this section we look at the limits of the formative and summative evaluative approaches, and reflect on the limitations of the present study.

5.1. Formative Evaluation

The results of the formative evaluation made it clear that the partnership group activities were seen as high in quality. However, the evaluation of the activities was based on memory, observation and anecdote, and the record itself is fraught with the uncertainties of meetings and regular attendance of a small group of persons. The timeliness of evaluative information or feedback was irregular. For example, months after the school presentation was over, the group learned that an AUD advocacy group of students had been formed. This delay of results is not unusual in social-marketing settings. It is one of the characteristics of social-marketing approaches that distinguishes it from commercial marketing. Other characteristics of communication can be seen in the ad-hoc process of creating the formative evaluation. What might seem to be subjective evaluations of activities can nonetheless provide insights for planning and adjustments.

5.2. Summative Evaluation

It is tempting to read the ENA visualization results and the post- and pre-event analyses as support for the idea that the key informative elements (CAUDS) and the key connective elements (community members, partners, and researchers) in these discussions are “engaging” because they show co-occurrence (Gries & Durrant, 2020). Gries and Durrant call this the distributional hypothesis, “which holds that linguistic elements that are similar in terms of their distributional patterning in corpora also exhibit some semantic or functional similarity” (Gries & Durrant, 2020, pp. 141–142) However, it is important to remember that these co-occurrences are based on a framework that operates by tagging names of people with socio-ecological status pertinent to the concept of an expert-driven health intervention. Further, following our method, a person’s name or “voice” was given an assumed semantic validity (Glazier et al., 2021) by being identified with either a connective or informative role in the discourse. This assumption is based on the person’s name being written in the document. The person’s name being written in the document is a recording behavior of the person taking the minutes, who might have gotten the name wrong or ascribed the comment to the wrong person. But there are more considerations here than accounting for simple mistakes. As illustrated in the example below, assumptions about engagement and semantic validity are based on the Epistemic Network Analysis theory used in the evaluation. A closer look at how semantic validity was assigned to names of people in the meetings is provided below can help us contextualize our validity claims.

Suppose the minutes read, “Jeff thinks the presentation is too long.” If Jeff, who represents the health authority was identified as a “partner” object, the name “Jeff” was then substituted in the corpus by the concept tag of “[partner]”: a tag or participation indicator further associated with connectivity in the communicative analysis of relations. What can we make of the comment then? We might infer that Jeff is suggesting a revision to the information in the presentation (created by the [expert]) so the presentation will go over better with its intended audience. Can we see this as proof of engagement (because Jeff is engaging with the messaging of the [expert] speaker?) Rather than proof we more likely might just have a clue. That being the case, thinking in socio-cultural terms, this scrap of discourse could be seen as a micro-behavior: an instance at the micro level of a broader pattern of engagement (de Abreu, 2000; Rebedea et al., 2008). The validity of our analysis hinges on these kinds of theoretical assumptions and other questions, such as data limits.

5.3. Data Limits

A number of questions about the data need to be examined. For example: Were the meeting minutes the only source of data for summative evaluation? There might be evidence of engagement in data from formal inquiry with community members, or from an ongoing process of engagement evaluation (a practice of asking, “Are we engaging?”) This practice is widely encouraged by researchers in quality improvement (Langley et al., 2009). The reality of the situation is that engagement is multifaceted. Theoretically, engagement occurs when community members express or embody mitigative behaviors almost unconsciously. Mask wearing, for example, is, for some, an adopted mitigation against disease spread, but its scientific efficacy has been questioned (Rancourt, 2020). However, many people perform it without making a rational connection to epidemiological knowledge. For these persons, mask wearing aligns with cultural values of care and group identity (Barker & Kellogg, 2022). A social-marketing intervention such as the one discussed in this paper, attempts to measure change at this complex level of motivation.

A few other limitations on the data and process could be noted.

The textual data (the corpus of 40,000 words) could be too limited.

The minutes keeper might be inconsistent, making mistakes in taking minutes, using an idiosyncratic style of recording while also participating.

The heuristic evaluation could be expanded. Other frameworks (for example mental models (Chen, 2020)) may provide alternative ways of structuring semantic contributions to meeting discussions.

A final consideration has to do with questions that are not asked. How did roles shift during the intervention? Did people go on vacations, leaves, or get replaced? What extraneous diversions could have affected the taking of minutes? No magic lens points directly to engagement. The very act of initiating, funding, and following through of a well planned, year-long series of activities on the part of concerned citizens might yield nothing but itself as evidence of engagement (Barker & Mitchel, 2021).

6. Conclusion

This research study began by responding to a mandate to perform an “additional investigation of the mechanism” of change that would provide insight into key criteria needed to sustain this change (Szelest et al., 2021). The question remains: “What are the criteria to sustain this change?” Our answer to the question lies in the process used. We assumed that the sustaining of change, given the social-marketing approach, would be found in the recorded co-occurrence of words of the expert organization in the words of the working group members, and, through them, the words, conversations, and discussions of the families, friends, schoolmates, and governing bodies that make up the socio-ecological environment of the AUD sufferer in this location. The research tools in the process (formative and summative frameworks, Epistemic Network Analysis, text data visualizations) allowed for the systematic reduction of and focus on voluntary discursive behavior (talk recorded in meeting minutes). That representation seemed to show just such a co-occurrence of expert message talk and community talk. We also discussed how this process could have taken different paths by looking at different evidence with different lenses. The resulting criteria, in the end, would seem to lie in co-occurrence. Did the intervention give voice to influential persons, and did that strategy lead to the natural flow of useful information and the creation of supportive community networks? The criteria for sustained change then, would be seen in the co-occurrence of expert messengers and community messengers in a shared discursive space (a meeting) that focuses on goal-oriented group activity (i. e. presentations in influential family, community, and social arenas).

Engagement, however, is an phenomenon that often requires communication theories and learning frameworks to quantify it. Using these tools, the actual evidence and impact is only implicit in the research representations. What our study has shown is that relatively simple practices could be followed to produce a naturalistic representation of the influence of expert thinking. Meeting minutes, for example, that record of who said what can provide just such a representation. Posts and comments on social media can also yield evidence of engagement, that can be tagged easily by recording and anonymizing the names of the posters. For each of these text archives, a tool as simple as a word cloud or “tag cloud” (Wikipedia contributors, 2023), can be a starting point for finding terms that suggest co-occurrence and, as we have seen, engagement.

7. Recommendations

A variety of formative evaluation evidence (anecdotes, quick surveys, conversations, and Facebook comments) can attest to the reach of engagement in this case, suggesting that the model could be spread. This reach of engagement may, in subsequent interventions, suggest domains for further summative evaluation following the methods of communicative analysis used here. But without talk about the topic and how to share it, there will be little evidence that can be mined for characteristics of communicative engagement. Where discourse is produced consistently, and with a clear function, a record will probably be kept. Most likely such a record will indicate both information flow and connectivity, which may, in turn, be used as evidence of engagement.

Author Contributions

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines for authorship.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the following agencies: The Trottier Family Fund; The Kule Institute for Advanced Studies, University of Alberta; and the MITACS Business Strategy Internship Program.

Conflicts of Interest and Ethics Statements

The project has received approval from the Alberta Research Information Services, Human Research Ethics Board 2 (Pro00122122).

References

- AimiHub - Strategic Improvement Management Platform. AimiHub - Strategic Improvement Management Platform. (n.d.). Available online: https://aimihub.com/ (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Aldoory, L.; Parrish, C.; Toth, E.L. A SOCIO-ECOLOGICAL MODEL OF INFLUENCE. Women in Mass Communication: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion 2022, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Aldoory, L.; Toth, E.L. The Future of Feminism in Public Relations and Strategic Communication: A Socio-Ecological Model of Influences. Rowman & Littlefield 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alwell, M.; Cobb, B. Social and Communicative Interventions and Transition Outcomes for Youth with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals 2009, 32, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, R.; Batchelder, W. Cultural consensus theory for multiple consensus truths. J. Math. Psychol. 2012, 56, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, A.R. Rethinking the Relationship between Social/Nonprofit Marketing and Commercial Marketing. J. Public Policy Mark. 2012, 31, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwell, K.; Freeman, M. I Immunise: An evaluation of a values-based campaign to change attitudes and beliefs. Vaccine 2015, 33, 6235–6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, J.B.; Gill, R.; Barge, J.K. Organizational Communication Design Logics: A Theory of Communicative Intervention and Collective Communication Design. Commun. Theory 2018, 28, 332–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.; Kellogg, J. Exploring the Colgate Model: A Case Study of the Role of Crisis and Risk Communication in Higher Education. J. Educ. Learn. 2022, 11, p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.; Mitchel, C. Community-Service Agency Communicative Collaboration During COVID-19 Pandemic. ALIGN Journal Special Edition 2021, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ba, S.; Hu, X.; Stein, D.; Liu, Q. Assessing cognitive presence in online inquiry-based discussion through text classification and epistemic network analysis. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 54, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, B.A.; Bhat, G.J. Formative and summative evaluation techniques for improvement of learning process. European Journal of Business & Social Sciences 2019, 7, 776–785. [Google Scholar]

- Black, P.; Wiliam, D. Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability(formerly: Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education) 2009, 21, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, F.G.; Cazelles, K.; Gravel, D. Co-occurrence is not evidence of ecological interactions. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23, 1050–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borysov, O.; Vasylieva, O. Communicative Analysis of Dialogical Interaction. Central Eur. J. Commun. 2022, 15, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bova, D.M. Building Consensus for Sustainable Development: Evaluation Theory Insights. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 11, 104–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brunton, G.; Thomas, J.; O’mara-Eves, A.; Jamal, F.; Oliver, S.; Kavanagh, J. Narratives of community engagement: a systematic review-derived conceptual framework for public health interventions. BMC Public Heal. 2017, 17, 944–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butscher, F.; Ellinger, J.; Singer, M.; Mall, C. Influencing factors for the implementation of school-based interventions promoting obesity prevention behaviors in children with low socioeconomic status: a systematic review. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2024, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfoss, F.D.; Francisco, V.; Capwell, E.M. Stakeholder Participation in Evaluation. Heal. Promot. Pr. 2001, 2, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byerley, L. E. Using a Conceptual Framework to Analyse Communicative Interventions that Address Vaccine Hesitancy. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J. W. A CULTURAL APPROACH. Theorizing Communication: Readings Across Traditions 2007, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen, J.; Getz, D.; Soutar, G. Event Evaluation Research. Event Manag. 2000, 6, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.A.; Ruhe, M.C.; Weyer, S.; Litaker, D.; Fry, R.E.; Stange, K.C. An Appreciative Inquiry Approach to Practice Improvement and Transformative Change in Health Care Settings. Qual. Manag. Heal. Care 2007, 16, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charaudeau, P. A communicative conception of discourse. Discourse Stud. 2002, 4, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; et al. Corpus-based linguistic approaches to critical discourse analysis. The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics 2013, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. Risk communication in cyberspace: a brief review of the information-processing and mental models approaches. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 36, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, D. Review of Interventions to Enhance the Health Communication of People With Intellectual Disabilities: A Communicative Health Literacy Perspective. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2016, 30, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooren, F. The Communicative Achievement of Collective Minding: Analysis of Board Meeting Excerpts. Management Communication Quarterly 2004, 17, 517–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, E.S.; Dill, L.J.; Sutton, S. Collective Healing: A Framework for Building Transformative Collaborations in Public Health. Heal. Promot. Pr. 2021, 23, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, R.; Parker, A.; Prusak, L.; Borgatti, S.P. Knowing what we know: Supporting knowledge creation and sharing in social networks. Networks in the Knowledge Economy 2003, 208–231. [Google Scholar]

- Croucher, S.M. Social Networking and Cultural Adaptation: A Theoretical Model. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 2011, 4, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, R. Improvement Science: Methods for Researchers and Program Evaluators; Myers Education Press, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Czaykowska-Higgins, E. (2009). Research models, community engagement, and linguistic fieldwork: Reflections on working within Canadian Indigenous communities. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/4423.

- de Abreu, G. Relationships between macro and micro socio-cultural contexts: implications for the study of interactions in the mathematics classroom. Educational Studies in Mathematics 2000, 41, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diller, K.R.; Phelps, S.F. Learning Outcomes, Portfolios, and Rubrics, Oh My! Authentic Assessment of an Information Literacy Program. portal: Libr. Acad. 2008, 8, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, J. L. Augmentative and Alternative Communication Intervention: An Intensive, Immersive, Socially Based Service Delivery Model.; Plural Publishing, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dringus, L.P.; Ellis, T. Using data mining as a strategy for assessing asynchronous discussion forums. Comput. Educ. 2005, 45, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.J.; Kreps, G.L. Reducing health disparities: communication interventions; Peter Lang New York: NY, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Egbert, J., & Schnur, E. (2018). The role of the text in corpus and discourse analysis: Missing the trees for the forest. Corpus Approaches to Discourse. [CrossRef]

- Emmert, P. (1989). Measurement of Communication Behavior. Longman.

- Fedorova, L.L. Semiotics of Advertising: The Functional-Communicative Analysis. Vestnik NSU. Series: Hist. Philol. 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L. C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Social Networks 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, J.; Blair-Stevens, C.; McVey, D.; Merritt, R. Social Marketing and Public Health: Theory and practice; OUP Oxford, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glazier, R.A.; Boydstun, A.E.; Feezell, J.T. Self-coding: A method to assess semantic validity and bias when coding open-ended responses. Res. Politi- 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J.D.; Padayachi, U.K. The prevalence and nature of child sexual abuse in Queensland, Australia. Child Abus. Negl. 1997, 21, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.M.; Wandersman, A.; Chinman, M.; Imm, P.; Morrissey, E. An ecological assessment of community-based interventions for prevention and health promotion: Approaches to measuring community coalitions. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1996, 24, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R.M.; Wandersman, A.; et al. FORECAST: A formative approach to evaluating community coalitions and community-based initiatives. Journal of Community Psychology, 1994, 24, 6–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, R.; McDermott, L.; Stead, M.; Angus, K. The effectiveness of social marketing interventions for health improvement: what’s the evidence? Public Health 2006, 120, 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabill, J.T.; Simmons, W.M. Toward a critical rhetoric of risk communication: Producing citizens and the role of technical communicators. Tech. Commun. Q. 1998, 7, 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, S. T., & Durrant, P. (2020). Analyzing Co-occurrence Data. In M. Paquot & S. T. Gries (Eds.), A Practical Handbook of Corpus Linguistics (pp. 141–159). Springer International Publishing.

- Gunasekara, C.; Gerts, C. Enabling Authentic Assessment: The Essential Role of Information Literacy. J. Aust. Libr. Inf. Assoc. 2017, 66, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifah, M.; Irambona, A. Authentic assessment: Evaluation and its application in science learning. Psychol. Evaluation, Technol. Educ. Res. 2019, 1, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, B., & Brereton, D. (2005). Emerging models of community engagement in the Australian minerals industry. International Conference on Engaging Communities, Brisbane, 1. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bruce-Harvey/publication/43459873_Emerging_Models_of_Community_Engagement_in_the_Australian_Minerals_Industry/links/5570b59908ae2f213c2237d5/Emerging-Models-of-Community-Engagement-in-the-Australian-Minerals-Industry.pdf.

- How a small town rallied together to address alcohol use. (n.d.). Interior Health. Retrieved March 15, 2024, from https://www.interiorhealth.ca/stories/how-small-town-rallied-together-address-alcohol-use.

- Huberman, M., & Miles, M. B. (2002). The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion. SAGE.

- Jagosh, J.; Bush, P.L.; Salsberg, J.; Macaulay, A.C.; Greenhalgh, T.; Wong, G.; Cargo, M.; Green, L.W.; Herbert, C.P.; Pluye, P. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Heal. 2015, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.L.; Safadi, H.; Faraj, S. The Emergence of Online Community Leadership. Inf. Syst. Res. 2015, 26, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J. P. (2013). A cultural approach to the study of mediated citizenship. In Mediated Citizenship (pp. 161–180). Routledge.

- Kania, J., Hanleybrown, F., & Juster, J. S. (2014). Essential mindset shifts for collective impact. collectiveimpact-guide.dk. https://www.collectiveimpact-guide.dk/s/Essential_Mindset_Shifts_for_Collective_Impact.pdf.

- Kapucu, N. Interagency Communication Networks During Emergencies: Boundary Spanners in Multiagency Coordination. American Review of Public Administration 2006, 36, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamidehkordi, E.; Mousavi, S.K.; Zamani-Abnili, F.; Es'Haghi, S.R.; Ghasemi, J.; Gholami, H.; Moayedi, A.A.; Shagholi, R. Communicative interventions for preventing the novel Coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak: insights from Iran’s rural and farming communities. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2021, 28, 275–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, E.; Ito-Masui, A.; Esumi, R.; Ito, M.; Mizutani, N.; Hayashi, T.; Imai, H.; Shimaoka, M. Social Network Analysis of Intensive Care Unit Health Care Professionals Measured by Wearable Sociometric Badges: Longitudinal Observational Study. J. Med Internet Res. 2020, 22, e23184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kealey, E. Assessment and Evaluation in Social Work Education: Formative and Summative Approaches. J. Teach. Soc. Work. 2010, 30, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinberg, J.; Ligett, K. Information-sharing in social networks. Games Econ. Behav. 2013, 82, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, L.; Bernaards, C.M.; Hildebrandt, V.H.; Schaufeli, W.B.; de Vet Henrica, C.W.; van der Beek, A.J. Conceptual frameworks of individual work performance: a systematic review. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine / American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2011, 53, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousoulis, A.A.; Goldie, I. A Visualization of a Socio-Ecological Model for Urban Public Mental Health Approaches. Front. Public Heal. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, E.G.; A Mercy, J.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Zwi, A.B. The world report on violence and health. Lancet 2002, 360, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, G.J.; Moen, R.D.; Nolan, K.M.; Nolan, T.W.; Norman, C.L.; Provost, L.P. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance; John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.C.; Bendixsen, C.; Liebman, A.K.; Gallagher, S.S. Using the socio-ecological model to frame agricultural safety and health interventions. J. Agromedicine 2017, 22, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.W.J.; Ho, S.S.; O Lwin, M. Explicating problematic social network sites use: A review of concepts, theoretical frameworks, and future directions for communication theorizing. New Media Soc. 2016, 19, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liska, J. R., & Cronkhite, G. (1995). An Ecological Perspective on Human Communication Theory. Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

- Mautner, G. Corpora and critical discourse analysis. Contemporary Corpus Linguistics 2009, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- McMurray, A. (2006). Community Health and Wellness: A Socio-ecological Approach. Mosby Elsevier.

- Moro, S.; Rita, P.; Vala, B. Predicting social media performance metrics and evaluation of the impact on brand building: A data mining approach. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3341–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Sandoval, S. L., Peon-Escalante, I. E., & Badillo-Piña, I. (2016). A Communication System for Socio-Ecological Processes. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the ISSS - 2016 Boulder, CO, USA, 1(1). http://journals.isss.org/index.php/proceedings60th/article/view/2888.

- Nagao, K. Discussion Mining: Knowledge Discovery from Semantically Annotated Discussion Content. Annual Conference of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 158–168.

- Nagao, K.; Inoue, K.; Morita, N.; Matsubara, S. Automatic Extraction of Task Statements from Structured Meeting Content. 7th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, PortugalDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 307–315.

- Nagao, K.; Kaji, K.; Yamamoto, D.; Tomobe, H. Discussion Mining: Annotation-Based Knowledge Discovery from Real World Activities. Pacific-Rim Conference on Multimedia. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 522–531.

- Nieves, J.; Osorio, J. The role of social networks in knowledge creation. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pr. 2013, 11, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, G.J.; Gellin, B.G.; MacDonald, N.E.; Butler, R. Addressing vaccine hesitancy: The potential value of commercial and social marketing principles and practices. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4204–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mara-Eves, A.; Brunton, G.; McDaid, D.; Oliver, S.; Kavanagh, J.; Jamal, F.; Matosevic, T.; Hardenberg, A.; Thomas, J. Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Public Health Res. 2013, 1, 1–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpin, D. Corpus Linguistics and Critical Discourse Analysis: Examining the ideology of sleaze. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 2005, 10, 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Our Story. (n.d.). Canadian Alcohol Use Disorder Society. Available online: https://www.cauds.org/our-story (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Pettigrew, K. E., Fidel, R., & Bruce, H. (2001). Conceptual frameworks in information behavior. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology (ARIST), 35(43-78). http://faculty.washington.edu/fidelr/RayaPubs/ConceptualFrameworks.pdf.

- Pinto, R.M.; Park, S. (.; Miles, R.; Ni Ong, P. Community engagement in dissemination and implementation models: A narrative review. Implement. Res. Pr. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancourt, D. (2020). Masks don’t work: A review of science relevant to covid-19 social policy. viXra. https://pearl-hifi.com/11_Spirited_Growth/10_Health_Neg/04_Pandemics/05_COVID_19/Masks/04_Masks_Dont_Work__A_Review_of_Science_Relevant_to_COVID-1_Social_Policy.pdf.

- Rapchak, M.E.; Lewis, L.A.; Motyka, J.K.; Balmert, M. Information Literacy and Adult Learners: Using Authentic Assessment to Determine Skill Gaps. Adult Learning 2015, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebedea, T.; Trausan-Matu, S.; Chiru, C.-G. Extraction of Socio-semantic Data from Chat Conversations in Collaborative Learning Communities. European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 366–377.

- Rigotti, E.; Rocci, A. Towards a definition of communication context. Foundations of an interdisciplinary approach to communication. Studies in Communication Sciences 2006, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Sampsel, L.J. Voyant Tools. Music Reference Services Quarterly 2018, 21, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandu, A. Appreciative Philosophy - Towards a Constructionist Approach of Philosophical and Theological Discourse. Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies, 2011. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1767692.

- Schmitz, O. J. (2016). Socio-ecological Systems Thinking. In The New Ecology. [CrossRef]

- Schoeppe, J.; Cheadle, A.; Melton, M.; Faubion, T.; Miller, C.; Matthys, J.; Hsu, C. The Immunity Community: A Community Engagement Strategy for Reducing Vaccine Hesitancy. Heal. Promot. Pr. 2017, 18, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, D.W.; Collier, W.; Ruis, A.R. A Tutorial on Epistemic Network Analysis: Analyzing the Structure of Connections in Cognitive, Social, and Interaction Data. J. Learn. Anal. 2016, 3, 9–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, D. W., University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA, Ruis, A. R., & University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. (2017). Epistemic network analysis: A worked example of theory-based learning analytics. In Handbook of Learning Analytics (pp. 175–187). Society for Learning Analytics Research (SoLAR).

- Smith, M.E.; Brandenburg, D.C. Summative evaluation. Performance Improvement Quarterly 2008, 4, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, L.; Walls, G.; Julve, M.; O’meara, K.; Schmid, T.; Kalaitzaki, E.; Turajlic, S.; Gore, M.; Rees, J.; Larkin, J. Neurotoxicity from immune-checkpoint inhibition in the treatment of melanoma: a single centre experience and review of the literature. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springett, J. Impact in participatory health research: what can we learn from research on participatory evaluation? Educational Action Research 2017, 25, 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szelest, I.; Harries, B.; Motluk, L.; Harries, J. How prescribing available pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorder can impact the healthcare system: A retrospective quality improvement study. Healthcare Management Forum / Canadian College of Health Service Executives = Forum Gestion Des Soins de Sante / College Canadien Des Directeurs de Services de Sante 2021, 34, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taras, M. Summative and formative assessment: Perceptions and realities. Active Learning in Higher Education 2008, 9, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomobe, H.; Nagao, K. Discussion Ontology: Knowledge Discovery from Human Activities in Meetings. Annual Conference of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 33–41.

- Trickett, E.J.; Beehler, S. Participatory action research and impact: an ecological ripples perspective. Educ. Action Res. 2017, 25, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, L.M.; Whetstone, C.; Boards, A.; Busch, M.D.; Magnusson, M.; Määttä, S. Partnering with insiders: A review of peer models across community-engaged research, education and social care. Heal. Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, 769–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voyant Tools. (n.d.). Retrieved May 24, 2021, from https://voyant-tools.org/.

- Wallat, C.; Piazza, C. Evaluation and Policy Analysis: A Communicative Framework. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 1997, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzer, N.; Weaver, L.; McGuire, C. Collective impact approaches and community development issues. Community Dev. 2016, 47, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandersman, A.; Imm, P.; Chinman, M.; Kaftarian, S. Getting to outcomes: a results-based approach to accountability. Evaluation Program Plan. 2000, 23, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D. The Collaborative Construction of a Management Report in a Municipal Community of Practice: Text and Context, Genre and Learning. Journal of Business and Technical Communication 2004, 18, 411–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, B.; Nanavati, J. A systematic approach to performative and authentic assessment. Ref. Serv. Rev. 2013, 41, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, D. D., & Trosten-Bloom, A. (2010). The Power of Appreciative Inquiry: A Practical Guide to Positive Change. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Wikipedia contributors. (2023, December 12). Tag cloud. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tag_cloud&oldid=1189486436.

- Wood, M. Applying Commercial Marketing Theory to Social Marketing: A Tale of 4Ps (and a B). Soc. Mark. Q. 2008, 14, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Huang, L. A new accident causation model based on information flow and its application in Tianjin Port fire and explosion accident. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 182, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Gregory, S. Finding missing edges in networks based on their community structure. Phys. Rev. E 2012, 85, 056112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).