1. Introduction

On January 1, 2018, the International Financial Reporting Standard 9 (IFRS 9) came into effect within the European Union (EU), superseding the International Accounting Standard 39 (IAS 39). IFRS 9 introduced a new model for the recognition of Loan Loss Provisions (LLP)1, named Expected Credit Loss (ECL). This standard responds to criticisms leveled at IAS 39 and its advocated Incurred Credit Loss (ICL) model. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) (2011) highlights the ICL model's failure to timely reflect credit losses, which creates a cyclical effect on the economy, potentially exacerbating negative impacts in financial crisis contexts, like the one that began in 2007.

In recent decades, financial markets have undergone unprecedented development and have taken a significant stance in guiding corporate business, particularly for financial institutions (Ferreira, 2011). The granting of credit by these institutions has been in the spotlight, with the financial sector being highly sensitive to economic cycle fluctuations (Gebhardt, 2016). Excessive use of financial instruments by banks, and the untimely recognition of LLPs, can jeopardize the bank's continuity and, consequently, the financial sector, potentially spreading the crisis to other economic sectors (Novotny-Farkas, 2016). This is exemplified by the last high-risk mortgage credit (subprime) crisis and, subsequently, the financial crisis and real economy crises worldwide, necessitating a reassessment of the approach to financial instruments (Pucci, 2017).

Although risk management is a process developed by banking institutions, based on the organization's strategy with the primary aim of identifying potential impacting situations, the truth is, after one or more crises, new rules and impositions emerge for the financial sector to prevent new crises based on past events (retrospective vision). Even before the 2007 crisis, Bikker and Metzemakers (2005) noted that LLPs were substantially higher when GDP growth was lower, reflecting the increased risk from the economic cycle downturn. Thus, by minimizing risks through the early recognition of LLPs, financial institutions can, to some extent, mitigate systemic impacts, avoiding affecting their continuity. Pucci (2017) states that at the onset of the 2007 crisis, IAS 39 was blamed for leveraging the negative effects of the economic crisis by underestimating LLPs, leading various entities to demand significant changes, including the G20 and The Financial Stability Forum. The lack of timeliness in recognizing LLPs, and its impact on the adequacy of capital reserves, led to the contraction of balance sheets, contributing to the increase in systemic risk during the financial crisis (Bushman & Williams, 2015; Gebhardt & Novotny-Farkas, 2011).

After this financial crisis, both the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), responsible for issuing international financial reporting standards, and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), with jurisdiction in the United States, considered the development of a new aggregate standard for highly complex financial instruments as a necessity but also a significant challenge (Ferreira, 2011). The ECL model is divided into three phases, aiming to anticipate losses derived from granted credit, requiring LLPs to be recognized before defaults occur. This model also incorporates a new approach for recognizing financial assets, based on cash flow characteristics and the business model inherent to the asset in question. This new approach results in a unique impairment model, applied to all financial instruments. The IASB and FASB designed similar models. However, the FASB model recognizes all expected losses from loan grants, while the IASB model only recognizes part of these losses initially, with the remaining loss recognized when a "significant increase" in credit risk occurs (Giner & Mora, 2019).

Novotny-Farkas (2016) also highlights the role of regulators and the importance they can have in the proper application of the IFRS 9's ECL model. If regulators are overly conservative and excessively interventionist, they can jeopardize the consistency and integrity of financial reports. Consequently, Regulation (EU) 2017/2395 of December 12 defines the transitional regime to reduce the impact of introducing that standard on the financial sector's own funds on the first day of application, termed day one. This regulation allows deferring the impacts of introducing IFRS 9 on the financial sector for up to five years, necessitating the annulment of this transitional regime's adjustments. Thus, analyzing the effects of day one on financial stability, focusing on the ECL model and its impact on the regulatory capital of financial institutions, reveals a relevant and highly interesting topic for banking regulators and the literature in the field. Considering the research already conducted on the said day one, it is expected that the adoption of the IFRS 9's ECL model had a negative impact on the capitals of Portuguese banks, especially after the financial bailout of 2011 and the capital injection into the country's major banks (EBA, 2018; EY, 2018; Groff & Mörec, 2021; Khan & Damyanova, 2018; Löw et al., 2019).

This study aims to analyze the effect of applying the new ECL model of IFRS 9 on the level of Loan Loss Allowances (LLAs) in loans, own equity, and the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio, on the first day of January 2018, in Portuguese banks. The study highlights the negative impact of adopting the ECL model on 13 Portuguese commercial banks, showing that there was a significant increase in LLAs and, consequently, a reduction in the value of assets, own equity, and the CET1 ratio, taking into account the impact of Regulation 2017/2395 of December 12. This research differs from previous studies by considering the impact of Regulation 2017/2395 of December 12, adopting an innovative methodological approach, which can be useful for professionals and researchers in future studies. Indeed, the methodology used in previous research (Dantas et al., 2017 and Groff & Mörec, 2021), involving the comparison of means to assess the scenario before and after day one, was adapted to analyze the impacts on LLAs, own equity, and the CET1 ratio of banks in Portugal. With this approach, the study makes a significant contribution to the literature on the adoption of the ECL model of IFRS 9, highlighting the importance of regulators and standard setters in its implementation.

The present study is divided into five chapters. Following this introductory chapter, comes the literature review and hypothesis formulation. The third chapter presents the analysis model and the variables used in the empirical study, as well as the sample and methods of data collection and processing. In the fourth chapter, the statistical analysis is carried out, data normality is tested, and the results obtained are discussed. Lastly, the fifth chapter presents the main conclusions of the study, its limitations, and identifies some proposals for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Normative and Regulatory Frameworks

The study focuses on the normative and regulatory response to the challenges posed by the 2007 financial crisis, highlighting the development of IFRS 9 by the IASB as an innovative standard for the recognition and measurement of financial instruments. Ferreira (2011) and Silva (2017) acknowledge the IASB's effort to overcome complexities in formulating a comprehensive standard, introducing a logical model that incorporates the concept of expected losses. Bischof and Daske (2016) perceive IFRS 9 as a result of political compromise, balancing different perspectives.

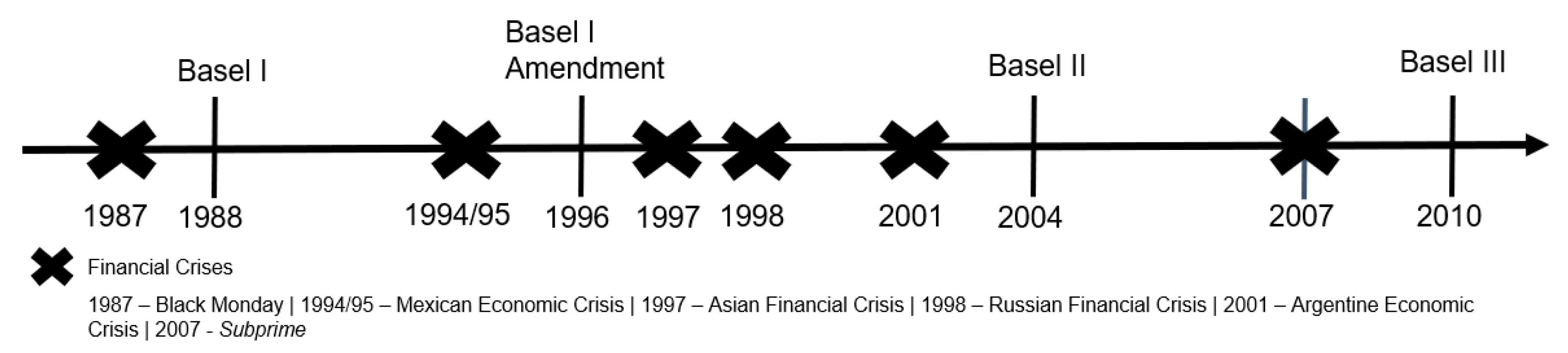

Despite the economic and social consequences, financial crises provide institutions with an opportunity to correct and implement control and supervision mechanisms, contributing to the minimization of future crises' impacts. Indeed, as

Figure 1 shows, regulation, particularly the Basel Accords, always follows financial crises, aiming to address existing failures, meaning regulators tend to act more reactively than from a preventive standpoint.

In terms of loss recognition, the transition from the ICL model to the ECL model marks a significant change, anticipating the recognition of losses before their actual occurrence. Giner & Mora (2019) discuss the previous prohibition of recognizing losses based on future events to prevent the manipulation of results.

IFRS 9 introduces a new paradigm with three classification phases based on credit risk deterioration, determining the calculation of expected losses. Phase 1 involves operations without a significant increase in credit risk (IFRS 9, §5.5.3), Phase 2 addresses operations with a significant increase in risk without impairment (IFRS 9, §5.5.9), and Phase 3 includes impaired operations (IFRS 9, §B5.5.37), similar to the approach under IAS 39 (IAS 39, §§58-59).

In transitioning to IFRS 9, banks reclassified financial assets according to the new requirements, determined LLPs based on the new rules, and adjusted retained earnings and other comprehensive income accordingly. Prior to this, Regulation (EU) 2017/2395 of December 12 was published to mitigate any potential impact on European banks' own funds from adopting the ECL model and, therefore, a sudden decrease in the CET1 ratio (§3 of the Regulation). This transitional regime has a maximum duration of five years, allowing part of the day one LLPs to be included in Tier 1 capital and gradually reduced to zero, ensuring the full application of IFRS 9 immediately after the transitional period ends (§5 of the Regulation). According to §9 of the Regulation, banks were required to publicly disclose in their reports and accounts, in a separate section of the Annex, their own funds, their capital ratios, and their leverage ratio, irrespective of the transitional regime's application, so stakeholders could determine the impact of the IFRS 9 model.

Choosing Portugal as a jurisdiction for a study on the ECL model's impact is justified by various factors intrinsic to its banking sector and economic-financial context. Firstly, the high ratio of Non-Performing Loans, which reached 17.48% in 2015, posed a systemic risk to the country's financial stability, underscoring the importance of credit risk management (Costa, 2016). The stress tests conducted between 2011 and 2012, coordinated by the European Banking Authority (EBA) in cooperation with the ESRB and Banco de Portugal, focused on the country's main banking groups, revealing remarkable resilience to the imposed adverse conditions (Banco de Portugal, 2011). This resilience is particularly notable given the deterioration in stock market capitalization and liquidity conditions during the financial and sovereign debt crisis in the Eurozone, requiring extraordinary public and private recapitalization measures.

The crisis highlighted the need for deleveraging in the Portuguese economy and the adjustment of strategies in the banking sector to ensure the banks' sustainability and solvency (Augusto & Félix, 2014; Arias et al., 2020). In this context, Banco de Portugal set clear goals for the sector, including reducing indebtedness and ensuring sustainable banking business models, which are crucial for the effective implementation of the IFRS 9's ECL model. This standard imposes stricter disclosure requirements, with the potential for greater market discipline. However, there are risks of a contraction in the accounting for LLPs, which could compromise the integrity of financial reports, especially in jurisdictions with greater incentives for earnings management (Novotny-Farkas, 2016; Marton & Runesson, 2017; Resende et al., 2024). Gomaa et al. (2019) demonstrate that, although the replacement of the ICL model with the ECL model provides for higher reserves, these will be less than anticipated, not offsetting the potential positive effects of the new model. The COVID-19 crisis further tested the application of the ECL model, with banks adopting conservative approaches, partly due to guidance from the IASB, and facing challenges in assessing the increase in credit risk (IASB, 2020; Salazar et al., 2023). In the Portuguese context, Resende et al. (2024) also found evidence of an increase in LLAs but below expectations given the economic risks.

Portugal thus represents an important case study due to its unique experience with significant financial challenges, regulatory and economic policy measures adopted in response to recent crises, and the central role of credit risk management in the context of implementing the IFRS 9's ECL model.

2.2. Normative and Regulatory Frameworks

As previously mentioned, one of the topics that have received special attention in this field is the so-called "day one," related to the first day of applying IFRS 9 and the new ECL model, due to the potential impact on financial stability. The focus on the regulatory capital of financial institutions proves to be a relevant and highly interesting subject for banking regulators and literature in the area (Nuss & Sattar, 2014; EBA, 2016; KPMG, 2016; ESRB, 2017). Although regulators initially expected significant reclassifications, banks assumed from the beginning that the classification and measurement requirements of IFRS 9 would not significantly impact capital requirements (EBA, 2016). Furthermore, the results of preliminary studies on impairments resulting from the IFRS 9 ECL model varied widely among banks, revealing an anticipated average increase in day one financial asset impairments between 18% (EBA, 2016) and 42% European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) (2017), compared to IAS 39. Nuss and Sattar (2014) estimated that implementing IFRS 9 requirements would cause a significant increase in the level of LLPs, predicted to be around 50%. On the other hand, KPMG (2016) forecasted an increase in LLPs during the transition that could range between 30% and 250% for mortgage loans, and between 25% and 60% for other credits.

Thus, considering the study's goal, based on the results of predictive studies indicating that the adoption of the IFRS 9 ECL model would have a significant positive impact on LLAs (EBA, 2016; EBA, 2018; ESRB, 2017, Groff & Mörec, 2021; KPMG, 2016; Nuss & Sattar, 2014), the following hypothesis is formulated to be empirically tested:

H1: The adoption of the ECL model had a positive impact on the level of LLAs on the credits of Portuguese banks.

Although initial studies indicated that most of the major European banks recorded a negative impact on their net assets, which was in line with the predictions of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) (2017) and the European Commission (2021), a more significant increase in banks' LLPs was expected, which would lead to a greater impact on net assets than what was observed with the implementation of the ECL model.

From the initial studies, the EBA (2018) gathered empirical evidence reported from the said day one, in which financial institutions felt the first effects of its application. That study confirmed the initial predictions of the transition to the ECL model, reporting additional LLPs and a reduction in banks' capitals. From the literature review, it was found that the studies already published differ in the methodologies used and show different results. The study by Ernst & Young (EY) (2018) focuses on changes in LLPs and coverage ratios. Khan and Damyanova (2018) focus on the aggregate impact of IFRS 9 on banks' equity, while Löw et al. (2019) detail the impact of this new model in various countries with different jurisdictions. On the other hand, Groff and Mörec (2021) focused on the IFRS 9 transition, noting an increase in the recognition of LLAs and a decrease in Slovenian banks' own capitals.

EY (2018) analyzed disclosures in reports and accounts on the transition to IFRS 9 of twenty large banks located in Europe, the United Kingdom, and Canada. All German banks and two Canadian banks reported an increase in financial asset losses in the transition to IFRS 9. However, banks assumed that the reported impact was less than expected before the transition, due to adopted policies of anticipating economic downturns, a forward-looking perspective already incorporated into impairment models, reflecting macroeconomic conditions and reclassifications to Fair Value Through Profit or Loss (FVTPL). Khan and Damyanova (2018) found similar results for a sample of 16 European banks with total assets over 300 billion euros. Also, Groff and Mörec (2021) investigated the day one impact of IFRS 9 on LLAs and equity of banks in Slovenia. The authors found evidence of an increase in LLAs and a decrease in the equity of banks in that country. Likewise, the EBA (2018), in a study covering 54 financial institutions from 20 Member States, confirms predictions regarding the increase in LLAs and the reduction of banks' own capital as a result of applying IFRS 9.

Hence, regulators, following various crises, have adopted a more preventive approach, as exemplified by the publication of the aforementioned regulation, establishing a five-year transitional regime to absorb the impact of introducing IFRS 9 in the financial sector. This regulation allowed banks to mitigate the impact of adopting IFRS 9. For this reason, to understand the real impacts on Portuguese banks resulting from the application of the new ECL model present in the said standard, it becomes necessary to cancel out the adjustments resulting from the said regulation.

According to the EBA (2016), the adoption of the IFRS 9 ECL model was not expected to have a significant impact on banks' own equity, possibly already anticipating the adoption of preventive measures by regulators and standard setters, such as Regulation (EU) 2017/2395 of December 12. In turn, the studies reviewed in the literature review demonstrate an increase in financial asset losses with the adoption of IFRS 9 and the new ECL model, having a negative impact on own equity (EBA, 2018; EY, 2018; Groff & Mörec, 2021; Khan & Damyanova, 2018; KPMG, 2016). In this sense, to test the impact of adopting the ECL model on the own equity of Portuguese banks, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H2: The adoption of the ECL model had a positive impact on the level of LLAs on the own equity of Portuguese banks.

Löw et al. (2019), based on a sample of 78 systemically important banks supervised by the European Central Bank, observed an average impact on the CET1 ratio of minus twenty basis points, with a standard deviation of 145 basis points, mainly due to the increase in LLAs, reducing on average the net equity by 1.8%. The study also showed that banks reclassified, on average, only 4.6% of financial assets. Moreover, of the 78 banks analyzed, only nine reported a combined positive effect of financial asset impairments and provisions for off-balance sheet exposures on the bank's equity. This study included one Portuguese bank in its sample (BCP), showing an impact on the CET1 ratio of -0.35% and on the own capital divided by the total asset of -3.8%.

Thus, another aspect to analyze is the effect of adopting the ECL model on the respective ratios required by regulators, in particular, the CET1 ratio. Regarding this ratio, the studies reviewed report significant negative impacts due to the increase in impairments on credits with the adoption of the ECL model (EY, 2018; KPMG, 2016; Löw et al., 2019). The empirical analysis of the impact of adopting the ECL model on the CET1 ratios of Portuguese banks will be based on the following research hypothesis:

H3: The adoption of the ECL model as anticipated in IFRS 9 had a negative impact on the CET1 ratio of Portuguese banks.

3. Methodology

3.1. Analysis Model and Variables

Research

Table 1 illustrates the design of this initial study, outlining the objectives, hypotheses, and the methodology adopted for data collection and processing.

As outlined in

Table 1, the study adopts a quantitative methodology to assess the impact of implementing the IFRS 9 ECL model on the level of LLAs in loans, own equity, and the CET1 ratio of Portuguese banks. The basis for this analysis is a comparative approach, adapted from the studies of Dantas et al. (2017) and Groff & Mörec (2021), focusing on the comparison of before and after the implementation of IFRS 9 and its ECL model. This method involves comparing averages of collected data, suitable for samples with fewer than 30 observations. Depending on the normality of the variables' distribution, the t-test is applied for variables with a normal distribution and the Wilcoxon test for those that do not follow this distribution (Laureano, 2020). For the variables

,

and

it was necessary to cancel the adjustments of the transitional regime introduced by Regulation (EU) 2017/2395 of December 12, which allows deferring the impacts of introducing IFRS 9 in the financial sector for up to five years, with

being added.

3.2. Analysis Model and Variables

The sample for this study was determined from the database of the Portuguese Banking Association, which, as of October 2020, listed 15 commercial banks with consolidated reports and accounts available for the years 2017 and 2018. It was from these reports and accounts that all necessary data for constructing the variables used in the study were manually collected. Two banks (CBI and Santander Consumer Finance) were excluded due to the unavailability of all required elements for the study, resulting in a final sample of 13 commercial banks.

Table 2 presents the identification and characterization of the Portuguese banks in the final sample, ordered by descending total assets as of 12-31-2017. As observed, on the last day of the year 2017, the total accumulated assets across all banks in the sample amounted to 348 billion euros.

The sample analysis highlights the dominance of the four largest Portuguese banks (CGD, BCP, Santander, and Novo Banco), which together constitute 77.66% of the total assets in the sample, with CGD, BCP, and Novo Banco having undergone state intervention, as previously mentioned. Conversely, the four smallest banks (BIG, Credibom, CTT, and Alves Ribeiro) represent only 1.37% of the total assets, illustrating the size disparity within the Portuguese banking sector. The analysis of reveals differences relative to the asset size of the banks, particularly with Santander and Novo Banco, where the latter, benefiting from state aid, exhibits a higher despite a smaller asset size compared to Santander. The also reflect significant differences, with Novo Banco showing the highest , while Santander has the lowest relative to its total assets. Montepio and other smaller banks, such as Credibom and Alves Ribeiro, demonstrate high in comparison to their size.

With the implementation of IFRS 9, a nominal overall negative impact was observed, marked by an increase in by 842 million euros, predominantly in larger banks (Novo Banco, BCP, Montepio, and CGD), justified by their larger size. Conversely, smaller banks (GCA and Credibom) and the two largest banks (Santander and BPI) exhibited smaller impacts, highlighting the variation of impact according to scale and nature of banking operations. A distinct outcome was seen with BIG, being the only bank to register a negative impact in , possibly due to its business model focused on investments and capital markets, diverging from the typical credit risk exposure of other commercial banks. The proportion of in relation to reveals that Montepio, Credibom, Novo Banco, and BCP were the most affected, aligning with the largest impacts observed, except for CGD which, benefiting from significant state capital injections, managed to mitigate the impact of the ECL model adoption better. The bank Credibom, specialized in consumer credit, stands out among the most affected, reflecting its greater exposure to the new model due to its focus on consumer credit.

Following,

Table 3 presents the assets of banks in the sample that were most impacted by the adoption of the IFRS 9 ECL model. It is important to note that

influenced three major asset groups, specifically: investments in credit institutions; customer loans; and debt instruments, measured at amortized cost.

It can be observed that for most banks, customer loans were the asset category most negatively influenced by the impact of adopting the IFRS 9 ECL model. However, the assets that suffered the greatest impact in CTT and Haitong banks were investments in credit institutions. In the case of Finantia bank, the most impacted assets were debt instruments. As previously mentioned, BIG was the only bank with a positive impact from the ECL model on its assets, specifically on customer loans. According to the information disclosed by the bank in its 2018 annual report, the positive impact was due to the positive revaluation of customer loans, stemming from the new ECL model.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Normality Tests

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables under study, providing an overview of the basic characteristics of the data, including measures of central tendency such as mean and median, and measures of dispersion such as standard deviation.

Analyzing the descriptive statistics of the variables and , it is observed that the data dispersion for these is greater than for the other study variables, indicating a higher asymmetry regarding the impacts on own equity resulting from the increase in LLA levels with the adoption of the IFRS 9 ECL model. Conversely, the variables and exhibit little dispersion, indicating some homogeneity regarding the impacts on LLA resulting from the adoption of the ECL model. Among the thirteen banks in the sample, it is noted that Novo Banco presents a value above 1 for the variables and , meaning that the LLA exceed its own equity. As previously mentioned, Novo Banco underwent state intervention through the Resolution Fund and was recovering its own equity as of 12-31-2017.

In terms of the overall sample, it can also be verified that the mean of is 0.183, while the mean of is 0.179, suggesting a slight decrease in the quality of the banks' regulatory capital on day one.

To choose the most appropriate statistical test for the study's hypothesis testing, it is necessary to verify the data's normality.

As observed in

Table 5, the variables

,

,

and

exhibit a normal distribution and are thus suitable for the t-test (Laureano, 2020, p. 42). Conversely, the variables

and

do not follow a normal distribution, requiring the use of the Wilcoxon test (Laureano, 2020, p. 173).

4.2. Analysis and Discussion of Results

Table 6 provides a summary of the statistical tests used and their respective results.

From the analysis of the presented results, Hypothesis 1 is validated, concluding that there was a significant positive impact with the adoption of the IFRS 9 ECL model on the level of LLA over customer loans, resulting from the increase in LLAs of Portuguese banks. This demonstrates higher reserves for future events compared to the ICL model of IAS 39 (p-value < 0.05). In other words, the positive impact on LLAs implied a significant decrease in the net value of loans resulting from the adoption of the IFRS 9 ECL model. The obtained result is in line with the expectations of previously analyzed studies, which estimated increases in LLAs with the adoption of the ECL model of IFRS 9 (EBA, 2016; EBA, 2018; ESRB, 2017, Groff & Mörec, 2021; KPMG, 2016; Nuss & Sattar, 2014).

Hypothesis 2 is also validated, concluding that there was a positive impact on the level of LLAs over the own equity of Portuguese banks with the adoption of the new ECL model (p-value <0.05). The obtained result confirms the expectations and findings of analyzed studies, where negative impacts on the levels of own equity in European banks were observed with the transition to the ECL model of IFRS 9 (EBA, 2018; EY, 2018; Groff & Mörec, 2021; Khan & Damyanova, 2018; KPMG, 2016).

Finally, Hypothesis 3 is also validated, concluding that there was a significant negative impact with the adoption of the IFRS 9 ECL model on the CET1 ratio of Portuguese banks (p-value <0.05). The obtained result aligns with the literature review, where negative impacts on the CET1 ratio in European banks were expected with the adoption of the new ECL model of IFRS 9 (EY, 2018; KPMG, 2016; Löw et al., 2019).

In summary, the results obtained for Portuguese banks show significant negative impacts on the net values of loans, own equity, and the CET1 ratio upon the adoption of the IFRS 9 ECL model, due to the widespread increase in LLAs. Thus, Portuguese banks exhibit higher reserves with the ECL model compared to the ICL model, being better prepared for economic downturns.

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Studies

This study represents an initial approach to the impact of adopting the IFRS 9 ECL model on the level of LLAs in loans, own equity, and the CET1 ratio of Portuguese banks. The financial sector is crucial in any jurisdiction, especially for Portugal, which sought external assistance in 2011 and underwent a financial adjustment program. Portuguese banks have been subjected to stress tests and state aids, with five out of the thirteen banks analyzed resorting to help for recapitalization, and one bank still receiving state aids for capitalization.

The study aims to analyze the impact of adopting the IFRS 9 ECL model on the level of LLAs in loans, own equity, and the CET1 ratio of Portuguese banks, on January 1, 2018, designated day one. The study focused on thirteen Portuguese commercial banks, selected from a pool of fifteen banks from the Portuguese Banking Association, excluding two due to lack of data. All data were manually collected from the consolidated reports and accounts for 2017 and 2018. The adopted methodology was based on approaches adapted from previous studies, such as Dantas et al. (2017) and Groff & Mörec (2021), comparing means of the same sample in different contexts. The results suggest that the impact is negative and statistically significant on the values of customer loans, own equity, and the CET1 ratio due to a widespread increase in LLA levels, thus enhancing the reserves improving the capacity of Portuguese banks to deal with future economic downturns.

The results of this study are relevant and make a significant contribution to the literature on the adoption of the IFRS 9 ECL model by considering not only the but also the impact of Regulation 2017/2395 of December 12, offering this study an innovative analysis compared to previous studies. The confirmation of significant negative impacts on the values of customer loans (due to a significant increase in LLAs), own equity, and the CET1 ratio, as a result of day one by Portuguese banks, demonstrates the commitment and effort of these institutions in applying the requirements of the IFRS 9 ECL model. Moreover, this study provides empirical evidence on the impact of adopting the IFRS 9 ECL model on the in banks of a specific jurisdiction, Portugal, which had not been studied before, considering the impacts of Regulation (EU) 2017/2395 of December 12. This approach is innovative and can be useful for sector professionals and researchers in future studies, offering important insights to understand the effects of adopting the IFRS 9 ECL model and the significant contributions by regulators and standard setters for its successful implementation.

This study significantly contributes to the knowledge about the IFRS 9 ECL model by exploring the direct implications of adopting this standard in Portuguese banks, with particular attention to the and the integration of the effects of Regulation (EU) 2017/2395 of December 12. By showing that Portuguese banks had reductions in the values of customer loans, own equity, and CET1 ratios right at the beginning of the model's application, aligning with the results found in the literature review, it confirms the importance of regulators in the application of new accounting rules, by allowing the deferral of the IFRS 9 and its ECL model impact for five years. Indeed, with that regulation, regulators contributed to a smooth transition of the IFRS 9 impacts, avoiding potential systemic risks such as non-compliance with CET1 ratios due to their reduction, which could cause constraints on the Portuguese banking sector. Additionally, by demonstrating an increase in reserves in line with expectations, the study reinforces the importance of the normative change to the ECL model, enabling higher reserves for economic downturns, contributing to a more resilient economy and a more transparent and prudent banking sector.

The main limitations of this study relate to using a small sample of banks, a consequence of intending to study in-depth a single jurisdiction, Portugal. This approach allowed analyzing the behavior of Portuguese banks in the transition to the new IFRS 9 ECL model in a uniform European context of regulation and supervision provided by the EBA while focusing on the economic and political peculiarities of Portugal.

For future studies, it would be important to compare the behavior of a fair value model with the current ECL model in recognizing LLPs, as well as to analyze the future impacts of the ECL model in different economic cycles and the quality of information disclosed by banks, both from day one information and information from subsequent periods. It would also be important to study the extent to which intervention by regulators and standard-setting bodies influenced the successful application of the IFRS 9 ECL model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.; methodology, M.R.; validation, C.C. (Carla Carvalho) and C.C. (Cecília Carmo); formal analysis, M.R.; investigation, M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.; writing—review and editing, C.C. (Carla Carvalho) and C.C. (Cecília Carmo) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript..

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study with sources as outlined in

Section 3.2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 |

In the specialized literature on the subject, it is common to encounter the terms Loan Loss Provisions (LLPs) and Loan Loss Allowances (LLAs) to designate credit impairment losses. For the sake of uniformity in the terminology used in studies, this research will use the abbreviation LLP to express credit impairment losses recognized in the period, and LLA for the accumulated credit impairment losses, following the approach of Salazar et al. (2023). |

References

- Arias, J.; Maquieira, C.; Jara, M. Do legal and institutional environments matter for banking system performance? Econ. Res. 2020, 33, 2203–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto, Francisco, and Sónia Félix. 2014. O impacto da recapitalização bancária no acesso ao crédito por empresas não financeiras. Lisbon: Banco de Portugal. Available online: https://www.bportugal.pt/paper/o-impacto-da-recapitalizacao-bancaria-no-acesso-aocredito- por-empresas-nao-financeiras (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- de Portugal, B. Exercício de stress test Europeu: Principais resultados dos bancos portugueses; Banco de Portugal: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. 2017. Regulatory treatment of accounting provisions–interim approach and transitional arrangements. Basel: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d401.htm.

- Bikker, J.A.; Metzemakers, P.A.J. Bank provisioning behaviour and procyclicality. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2005, 15, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIS. Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems; (revised); Bank for International Settlements: Basel, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jannis, B.; Holger, D. Interpreting the European Union’s IFRS endorsement criteria: The case of IFRS 9. Account. Eur. 2016, 13, 129–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushman, R.M.; Williams, C.D. Delayed expected loss recognition and the risk profile of banks. J. Account. Res. 2015, 53, 511–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2021. Report on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 as regards requirements for credit risk, credit valuation adjustment risk, operational risk, market risk and the output floor. Belgium: European Commission. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2023-0030_EN.html.

- Carlos Silva, C. Desafios para o sistema financeiro e competitividade da economia; Banco de Portugal: Lisbon, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dantas, J.A.; Micheletto, M.A.; Cardoso, F.A.; Franca de Sa Freire, A.A.P. Credit losses in Brazilian banks: Expected losses and incurred models and impact of IFRS 9. Rev. De Gestão Finanças E Contab. 2017, 1, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBA. 2016. Report on results from the EBA impact assessment of IFRS 9. Paris: European Banking Authority. https://eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/1360107/EBA+Report+on+impact+assessment+of+IFRS9.

- EBA. 2018. First observations on the impact and implementation of IFRS 9 by EU Institutions. Paris: European Banking Authority. https://eba.europa.eu/sites/default/documents/files/documents/10180/2087449/bb4d7ed3-58de-4f66-861e-45024201b8e6/Report on IFRS 9 impact and implementation.pdf?retry=1.

- ESRB. 2017. Financial stability implications of IFRS. Germany: European Systemic Risk Board. https://www.esrb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/reports/20170717_fin_stab_imp_IFRS_9.en.pdf.

- European Union. 2017. Regulation (EU) 2017/2395 of the european parliament and of the council of 12 december 2017. Belgium: European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32017R2395.

- EY. 2018. IFRS 9 expected credit loss. London: Ernst & Young. https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-ifrs-9-expected-credit-loss/$File/ey-ifrs-9-expected-credit-loss.pdf.

- Ferreira, D. Instrumentos Financeiros; Rei dos Livros: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt, G. Impairments of Greek government bonds under IAS 39 and IFRS 9: A case study. Account. Eur. 2016, 13, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, G.; Novotny-Farkas, Z. . Mandatory IFRS adoption and accounting quality of European banks. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2011, 38, 289–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giner, B.; Mora, A. Bank loan loss accounting and its contracting effects: The new expected loss models. Account. Bus. Res. 2019, 49, 726–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.; Kanagaretnam, K.; Mestelman, S.; Shehata, M. Testing the efficacy of replacing the incurred credit loss model with the expected credit loss model. Eur. Account. Rev. 2019, 28, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman Grof, M.; Mörec, B. IFRS 9 transition effect on equity in a post bank recovery environment: The case of Slovenia. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2021, 34, 670–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IASB. 2004. International Accounting Standard 39-Financial Instruments: Recognition and Measurement.

- IASB. 2014. International Financial Reporting Standard 9–Financial Instruments.

- IASB. 2020. IFRS 9 and COVID-19. Available online: https://cdn.ifrs.org/-/media/feature/supporting-implementation/ifrs-9/ifrs-9-ecl-and-coronavirus.pdf?la=en (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Khan, E.; Damyanova, V. European bank´s capital survives new IFRS 9 accounting impact, but concerns remain. S&P Global Market Intelligence. 2018. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/research/european-banks-capital-survives-new-ifrs-9-accounting-impact-but-concerns-remain. (accessed on 16 February 2021).

- KPMG. IFRS 9 Instrumentos Financeiros: Novas regras sobre a classificação e mensuração de ativos financeiros, incluindo a redução no valor recuperável. 2016. Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2016/04/ifrs-em-destaque-01-16.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Laureano, R. Testes de hipóteses e regressão: O meu manual de consulta rápida; Edições Sílabo: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Löw, Edgar, Schmidt, Lisa Emma, and Thiel, Lars Franz. 2019. Accounting for financial instruments under IFRS 9: First-time application effects on European banks’ balance sheets. European Banking Institute Working Paper Series 2019–n.º 48. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3622311.

- Marton, J.; Runesson, E. The predictive ability of loan loss provisions in banks: Effects of accounting standards, enforcement and incentives. Br. Account. Rev. 2017, 49, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny-Farkas, Z. The interaction of the IFRS 9 expected loss approach with supervisory rules and implications for financial stability. Account. Eur. 2016, 13, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nus, J.; Sattar, O. Balloning loss reserves could deflate bank capital. Financ. Report. 2014, 20, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pucci, R. Accounting for Financial Instruments in an Uncertain World: Controversies in IFRS in the Aftermath of the 2008 Financial Crisis. Doctoral thesis, Copenhagen Business School, Frederiksberg, Denmark. 2017. Available online: https://research.cbs. dk/en/publications/accounting-for-financial-instruments-in-an-uncertain-world-contro (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Resende, M.; Carvalho, C.; Carmo, C. Impacts of the Expected Credit Loss Model on Pro-Cyclicality, Earnings Management, and Equity Management in the Portuguese Banking Sector. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, Y.; Merello, P.; Zorio-Grima, A. IFRS 9, banking risk and COVID-19: Evidence from Europe. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 56, 104130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.S. IFRS 9—Instrumentos Financeiros—Introdução às Regras de Reconhecimento e Mensuração; Vida Económica: Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).