Submitted:

29 March 2024

Posted:

29 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Origin of the Isolates of L. monocytogenes Used in Our Study

2.2. Study Design and Sources of Samples

2.3 Investigation of the Variables or Factors Associated with the Distribution of Genomic Characteristics of L. monocytosis Isolates

2.4 Isolation and Identification of L. monocytogenes Isolates

2.5 DNA Extraction from L. monocytogenes Isolates

2.6 Whole-Genome Sequencing, Genomic Analysis, Assembly, and Annotation

2.7. In Silico MLST

2.8. Resistance and Virulence Profiles

2.9. Construction of the Phylogenetic Tree for L. monocytogenes Isolates and Correlation with Source and Type of Samples

2.10. Provirus Detection

2.11. Detection of CRISPR-Cas System

2.12. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overall Frequency of Detection of STs and Genetic Materials

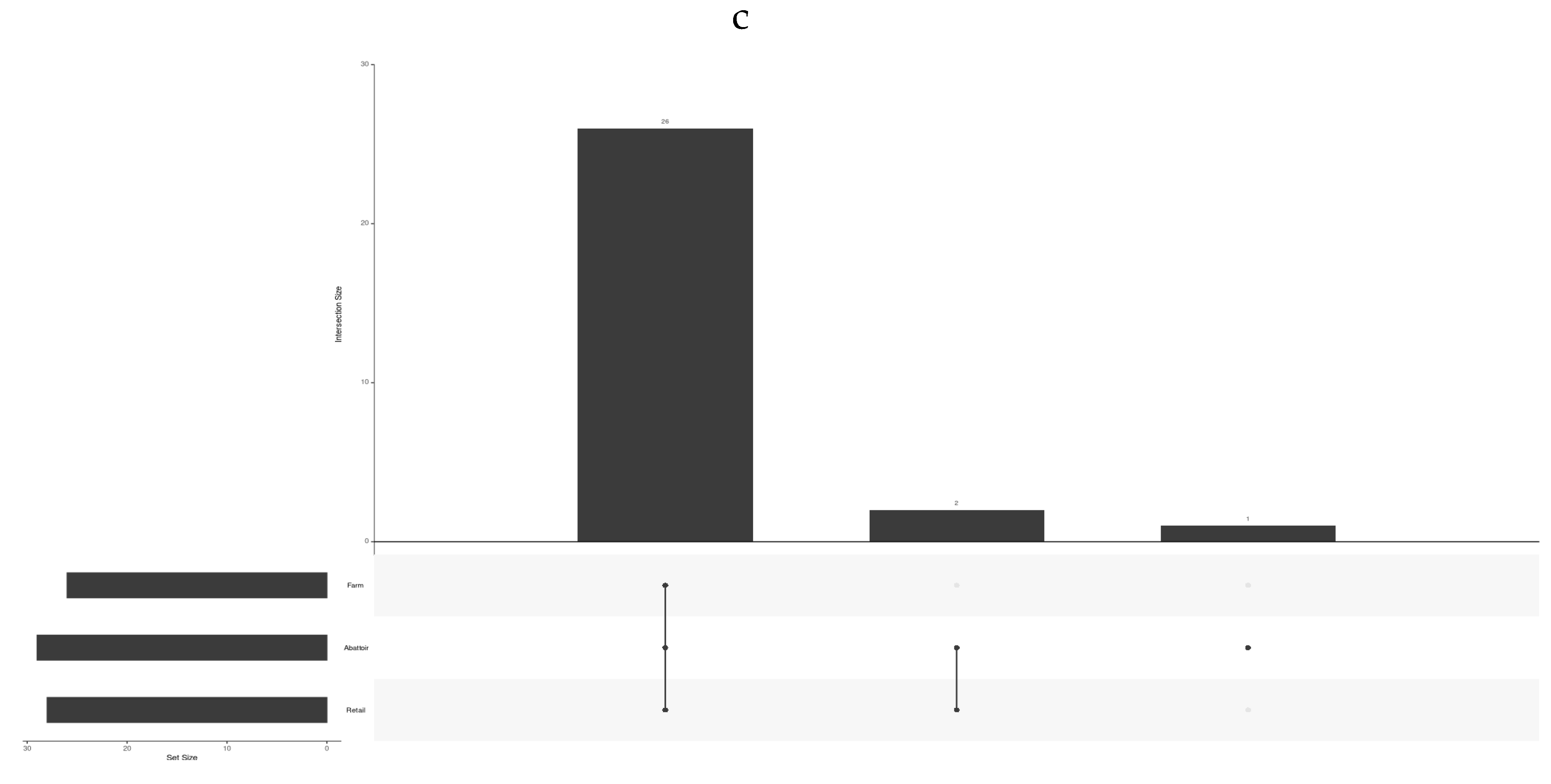

3.1.1. Influence of the Three Beef Industries (Cattle Farms, Abattoirs, and Retail) on the Frequency of STs, Virulence and AMR Genes, Plasmids, Provirus, and the CRISPR-Cas System

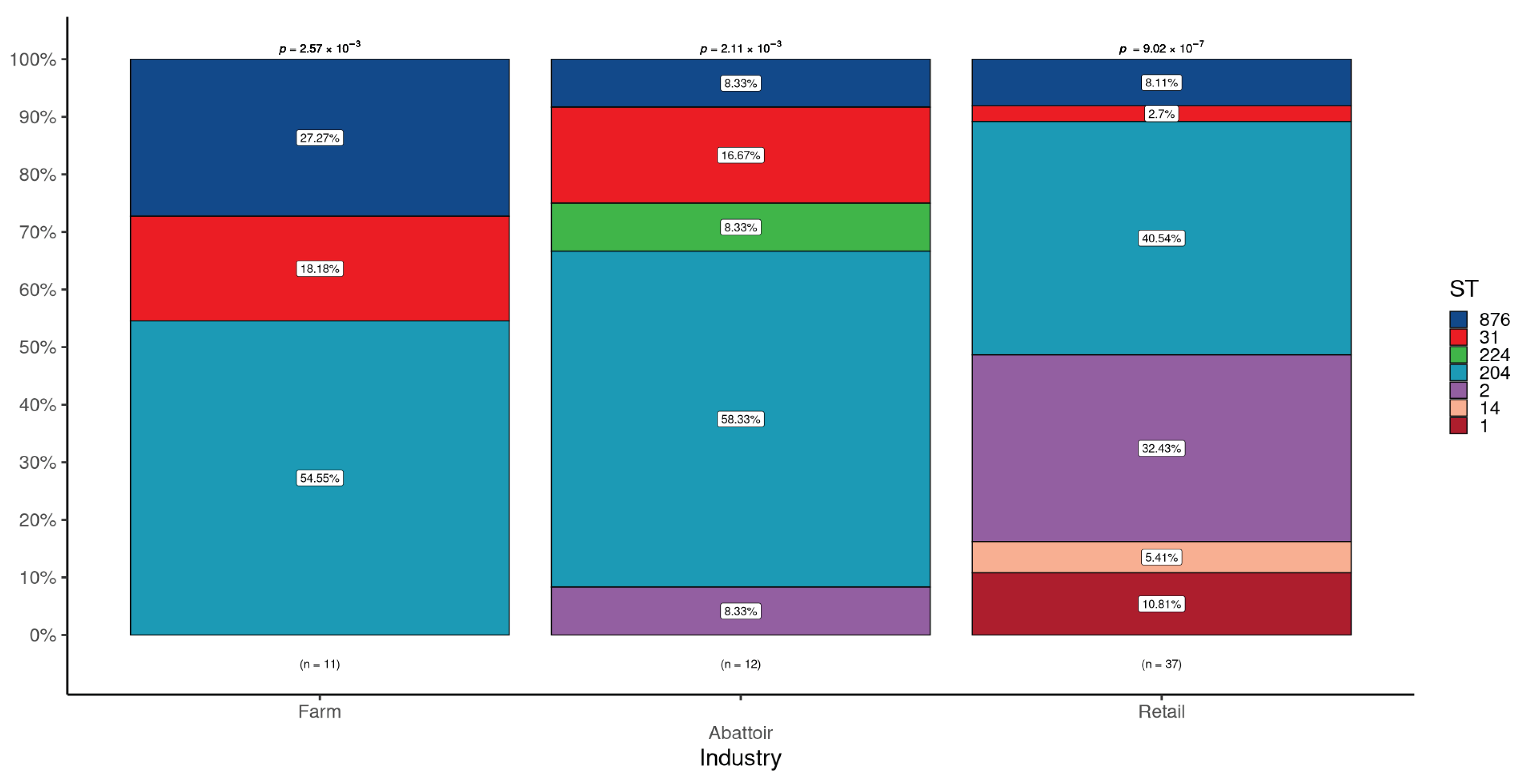

3.1.2. Detection of STs in L. monocytogenes According to Industries

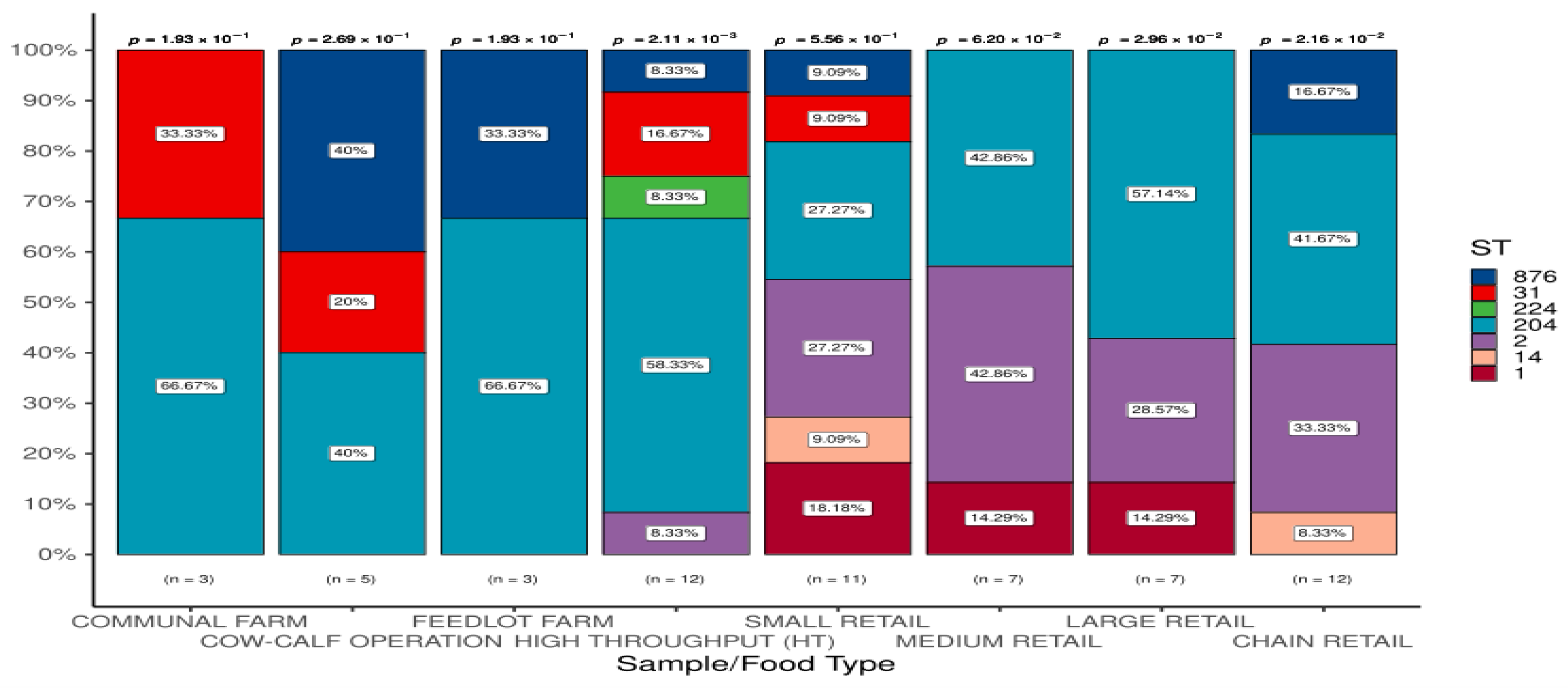

3.1.3. Detection of STs in L. monocytogenes According to Sample/Food Types

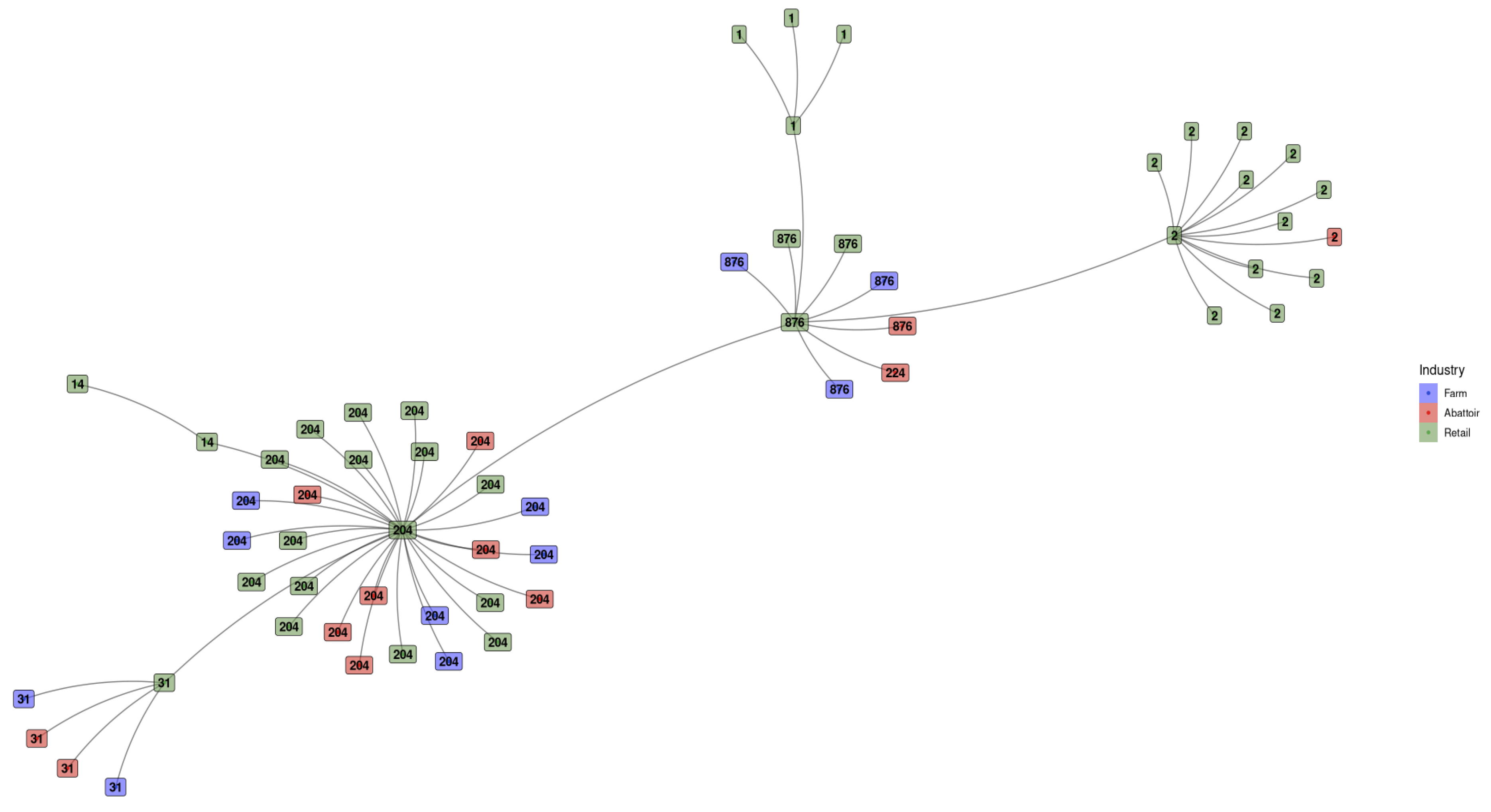

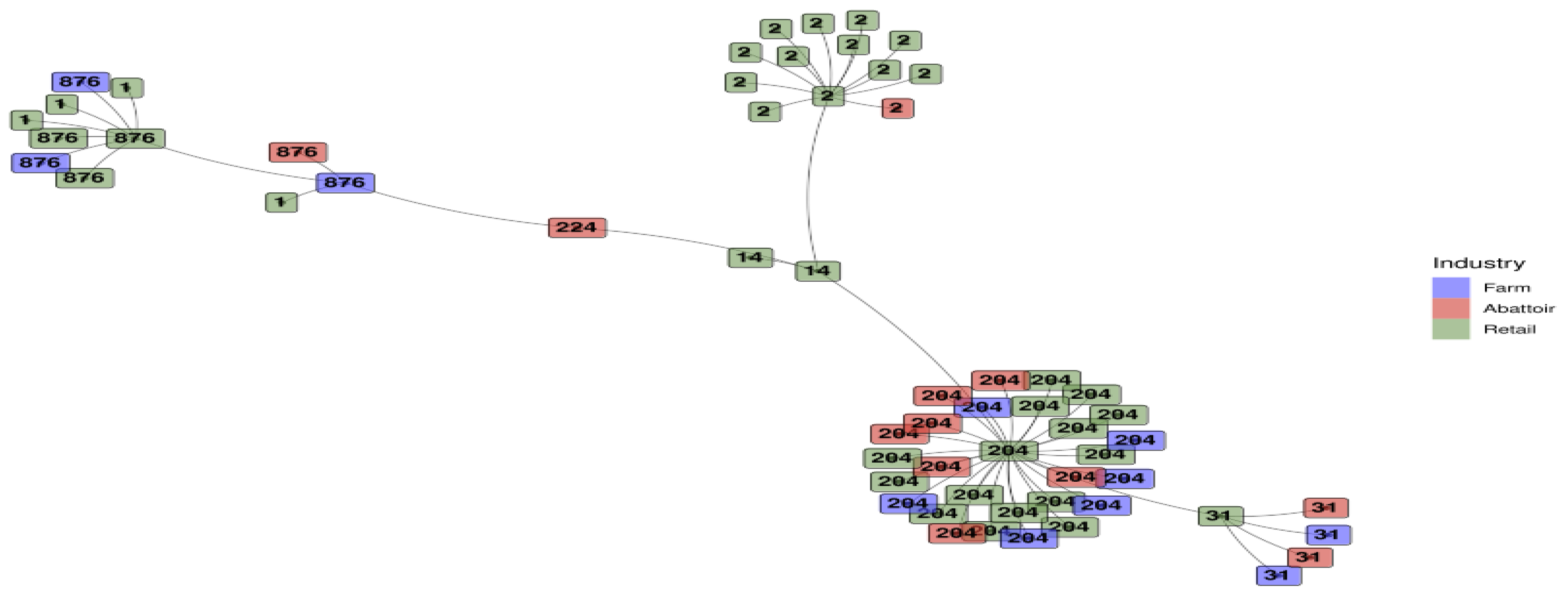

3.1.4. Minimum Spanning Tree Based on Sequence Types for L. monocytogenes Detected Across the Different Industries

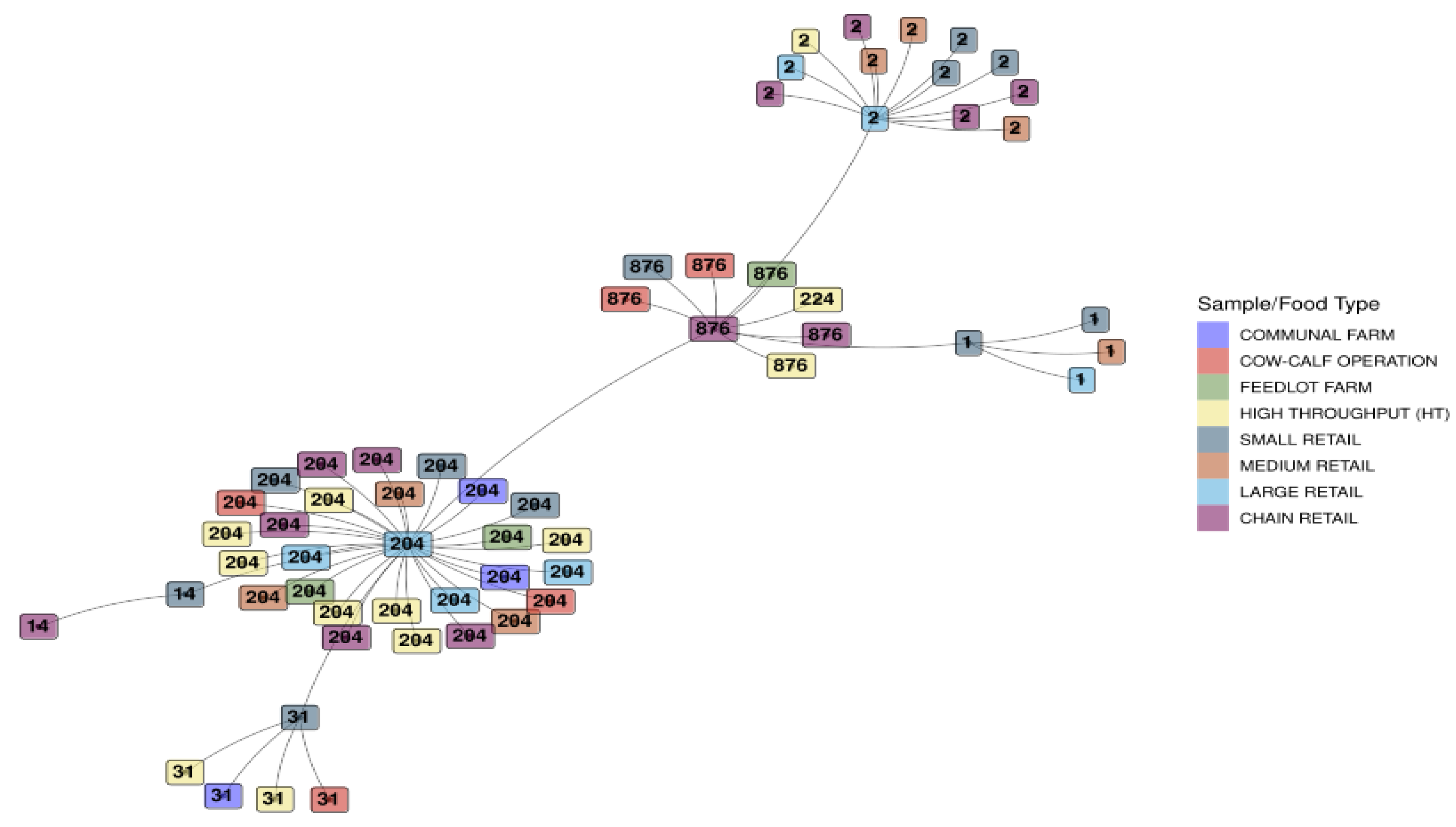

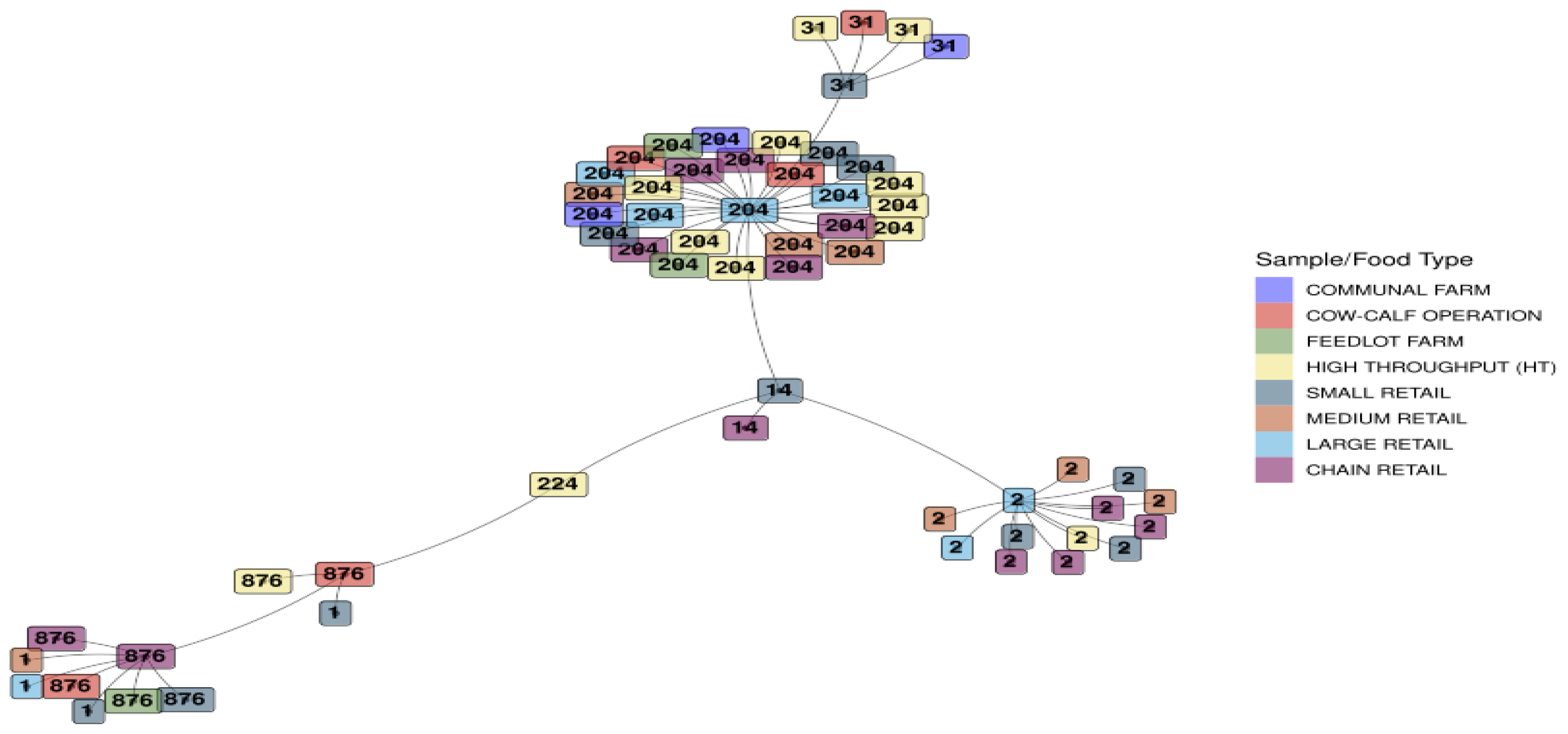

3.1.5. Minimum Spanning Tree Based on Sequence Types for L. monocytogenes Detected Across the Sample/Food Types

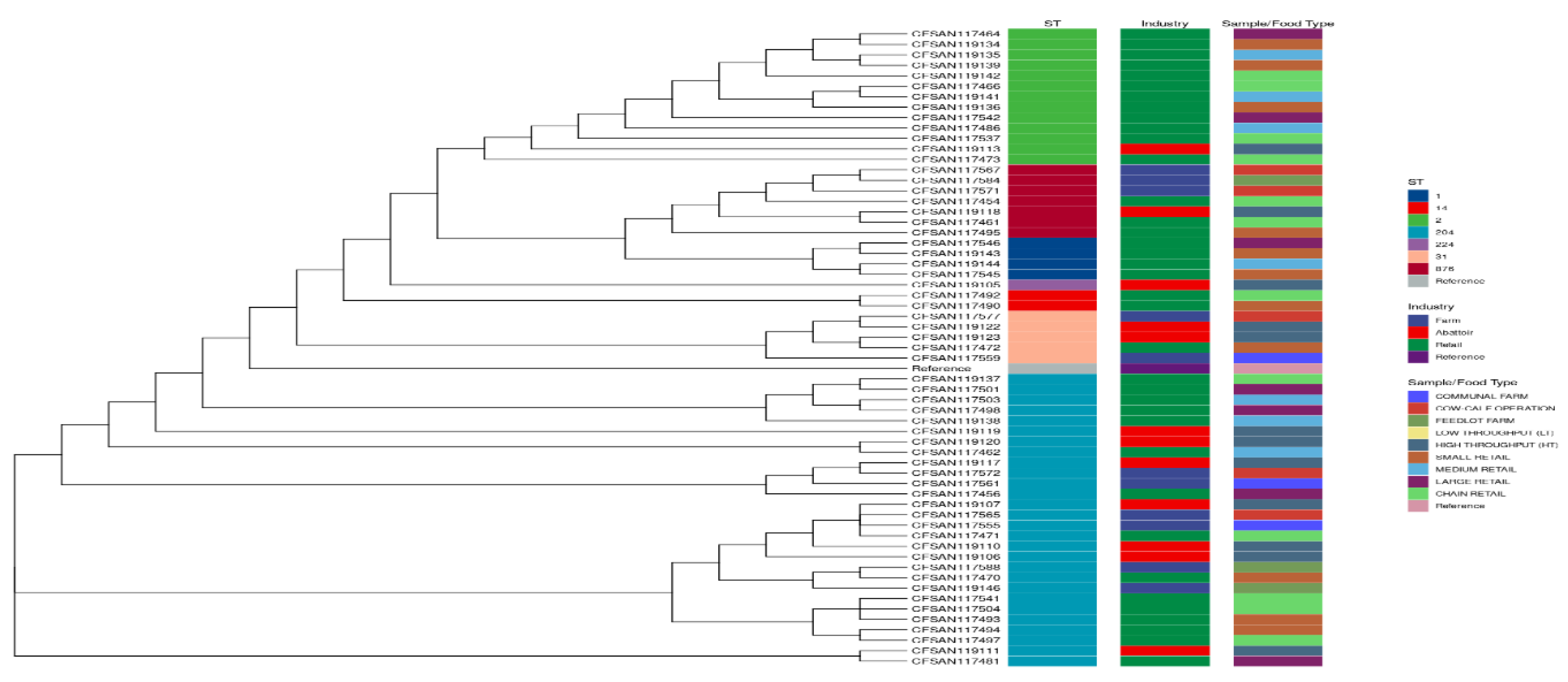

3.1.6. Phylogenies of L. monocytogenes According to STs, Industry, and Sample/Food Type

3.2. Distribution of Clonal Complexes (CC) among L. monocytogenes Isolates

3.3. Occurrence of Virulence Factors in L. monocytogenes Isolates According to the Industries and Sample/Food Samples

3.3.1. Frequency of virulence factors according to the industries

3.3.2. Frequency of Virulence Factors According to the Sample/Food Types

3.4. Frequency of Resistance genes in L. monocytogenes Isolates

3.5. Occurrence of AMR Plasmids in L. monocytogenes Isolates

3.6. Frequency of Proviruses/Prophages in the Isolates of L. monocytogenes

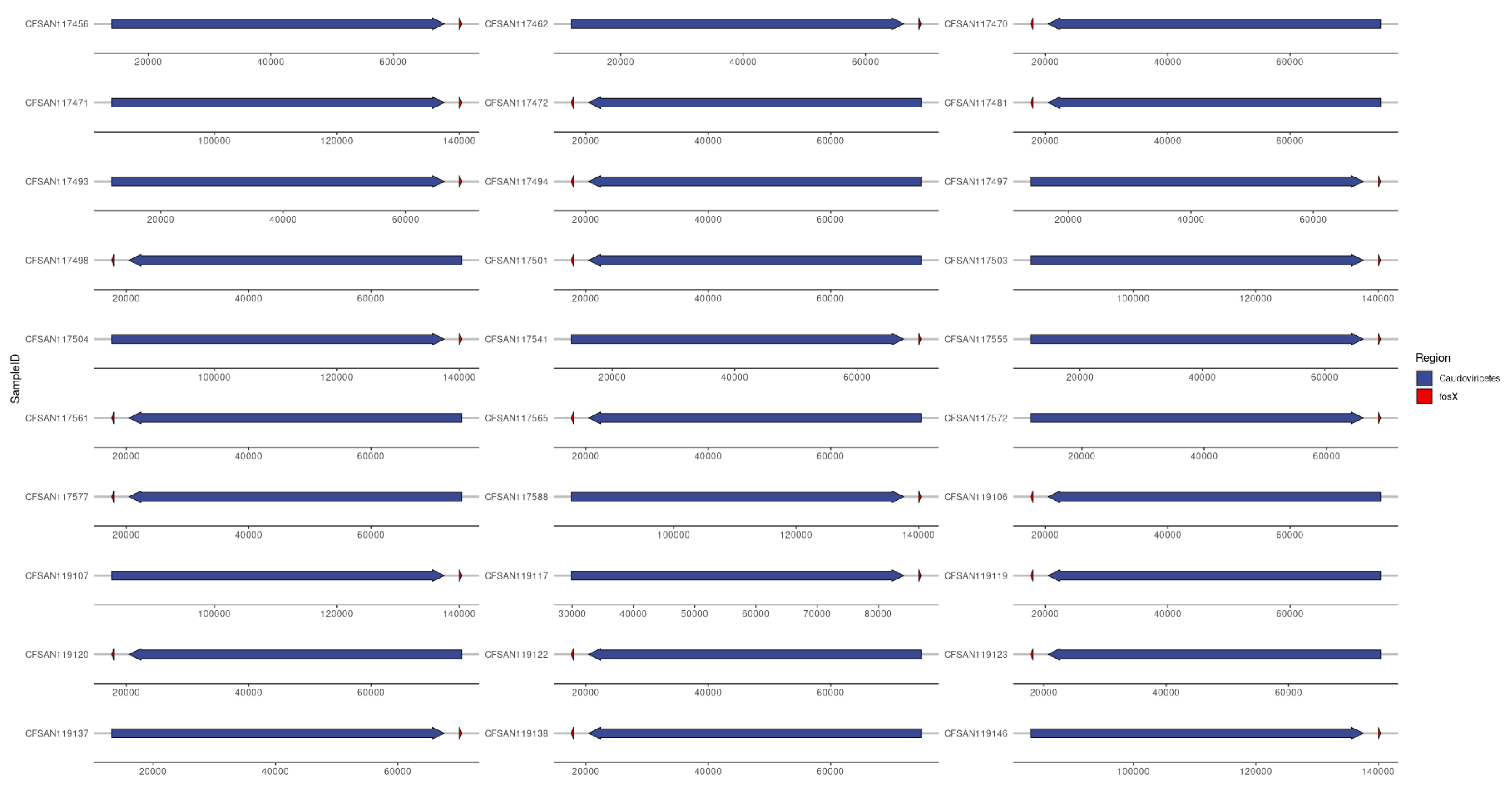

3.7. Frequency of Detection of the CRISPR-Cas System in L. monocytogenes Isolates

3.8. Provirus/Phage and AMR Co-Location (Provirus or Phage as Classification)

3.9. Characteristics of L. monocytogenes Recovered from RTE Beef Products

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olanya, O.M.; Hoshide, A.K.; Ijabadeniyi, O.A.; Ukuku, D.O.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Niemira, B.A.; Ayeni, O. Cost estimation of listeriosis (Listeria monocytogenes) occurrence in South Africa in 2017 and its food safety implications. Food contr 2019, 102, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilliard, A.; Leong, D.; O’Callaghan, A.; Culligan, E.P.; Morgan, C.A.; DeLappe, N.; Hill, C.; Jordan, K.; Cormican, M.; Gahan, C.G. Genomic characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolates associated with clinical listeriosis and the food production environment in Ireland. Genes 2018, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, M.M.; Brouwer, M.C.; Vázquez-Boland, J.A. and van de Beek, D.Human listeriosis. Clin Microbio Rev 2023, 36, e00060–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, P.; Sadana, J.R. Outbreak of Listeria ivanovii abortion in sheep in India. Vet Record 1999, 145, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillet, C.; Join-Lambert, O.; Le Monnier, A.; Leclercq, A.; Mechaï, F.; Mamzer-Bruneel, M.F.; Bielecka, M.K.; Scortti, M.; Disson, O.; Berche, P.; Vazquez-Boland, J. Human listeriosis caused by Listeria ivanovii. Emerg Infect Dis 2010, 16, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allam, M.; Tau, N.; Smouse, S.L.; Mtshali, P.S.; Mnyameni, F.; Khumalo, Z.T.; Ismail, A.; Govender, N.; Thomas, J.; Smith, A.M. Whole-genome sequences of Listeria monocytogenes sequence type 6 isolates associated with a large foodborne outbreak in South Africa, 2017 to 2018. Geno Anno 2018, 6, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbedel, S.; Prager, R.; Fuchs, S.; Trost, E.; Werner, G.; Flieger, A. Whole-genome sequencing of recent Listeria monocytogenes isolates from Germany reveals population structure and disease clusters. J.Clin Microbio 2018, 56, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union One Health 2021 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J 2022, 2, e07666. [Google Scholar]

- Cufaoglu, G.; Ambarcioglu, P.; Ayaz, N.D. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of Listeria spp. and antibiotic resistant Listeria monocytogenes isolates from foods in Turkey. Lwt 2021, 144, 111210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnci̇li̇, G.K.; Aydemi̇r, M.E.; Akgöl, M.; Kaya, B.; Kanmaz, H.; Öksüztepe, G.; Hayaloğlu, A.A. Effect of Rheum ribes L. juice on the survival of Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Salmonella Typhimurium and chemical quality on vacuum packaged raw beef. LWT 2021, 150, 112016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Moosekian, S.R.; Todd, E.C.; Ryser, E.T. Growth of Listeria monocytogenes in different retail delicatessen meats during simulated home storage. J. food Prot 2012, 75, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaître, N.; De Reu, K.; Haegeman, A.; Schaumont, D.; De Zutter, L.; Geeraerd, A.; Rasschaert, G. Study of the transfer of Listeria monocytogenes during the slaughter of cattle using molecular typing. Meat sci 2021, 175, 108450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, W.; Sun, T.; Gorris, L.G.; Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Dong, Q. The prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in meat products in China: A systematic literature review and novel meta-analysis approach. Inte J. food Microbio 2020, 312, 108358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, T.; Buys, E.M. (2022). Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis: The role of stress adaptation. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaloumi, S.; Aspridou, Z.; Tsigarida, E.; Gaitis, F.; Garofalakis, G.; Barberis, K.; Koutsoumanis, K. Quantitative risk assessment of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat (RTE) cooked meat products sliced at retail stores in Greece. Food Microbio 2021, 99, 103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Sun, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Dong, Q. Probabilistic model for estimating Listeria monocytogenes concentration in cooked meat products from presence/absence data. Food Res Inte 2020, 131, 109040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, J.D.; Borucki, M.K.; Mandrell, R.E.; Gorski, L. Serotyping of Listeria monocytogenes by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and identification of mixed-serotype cultures by colony immunoblotting. J. Clin Microbio 2003, 41, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, K.; Jordan, K. Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) Analysis of Listeria monocytogenes. Listeria Monocytogenes: Meth Proto, 2021; 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, D.; Luque-Sastre, L.; Parker, C.T.; Huynh, S.; Eshwar, A.K.; Nguyen, S.V.; Fanning, S. Whole-genome sequencing-based characterization of 100 Listeria monocytogenes isolates collected from food processing environments over a four-year period. MSphere 2019, 4, e00252-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chang, X.; Qin, S.; Song, Y.; Tian, J.; Ma, A. Analysis of 90 Listeria monocytogenes contaminated in poultry and livestock meat through whole-genome sequencing. Food Res Inte 2022, 159, 111641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Chen, Y.; Gorski, L.; Ward, T.J.; Osborne, J.; Kathariou, S. Listeria monocytogenes source distribution analysis indicates regional heterogeneity and ecological niche preference among serotype 4b clones. mBio. 2018, 9, e00396–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, J.K.; Didelot, X.; Lecuit, M.; Korkeala, H.L. monocytogenes MLST Study Group.; Achtman, M. The ubiquitous nature of Listeria monocytogenes clones: a large-scale M ultilocus S equence T yping study. Enviro Microbio 2014, 16, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papić, B.; Kušar, D.; Zdovc, I.; Golob, M.; Pate, M. Retrospective investigation of listeriosis outbreaks in small ruminants using different analytical approaches for whole genome sequencing-based typing of Listeria monocytogenes. Infec, Gen Evolu 2020, 77, 104047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.M.; Tau, N.P.; Smouse, S.L.; Allam, M.; Ismail, A.; Ramalwa, N.R.; Thomas, J. Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes in South Africa, 2017–2018: Laboratory activities and experiences associated with whole-genome sequencing analysis of isolates. Foodborne Path Dis 2019, 16, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Guo, W. Analysis of multilocus sequence typing and virulence characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from Chinese retail ready-to-eat food. Front Microbio 2016, 7, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, A.; Lefrancq, N.; Wirth, T.; Leclercq, A.; Borges, V.; Gilpin, B.; Dallman, T.J.; Frey, J.; Franz, E.; Nielsen, E.M.; Thomas, J.; Pightling, A.; Howden, B.P.; Tarr, C.L.; Gerner-Smidt, P.; Cauchemez, S.; Salje, H.; Brisse, S.; Lecuit, M. Listeria CC1 Study Group. Emergence and global spread of Listeria monocytogenes main clinical clonal complex. Sci Adv 2021, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Valladares, G.; Danielsson-Tham, M.L.; Tham, W. Implicated food products for listeriosis and changes in serovars of Listeria monocytogenes affecting humans in recent decades. Foodborne Path Dis 2018, 15, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiktorczyk-Kapischke, N.; Skowron, K.; Wałecka-Zacharska, E. Genomic and pathogenicity islands of Listeria monocytogenes—overview of selected aspects. Front Mole Biosci 2023, 10, 1161486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, P.D.; Draper, L.A.; Lawton, E.M.; Daly, K.M.; Groeger, D.S.; Casey, P.G.; Hill, C. Listeriolysin S, a novel peptide haemolysin associated with a subset of lineage I Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS pathogens 2008, 4, e1000144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Rump, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Meng, J. Molecular subtyping and virulence gene analysis of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from food. Food Microbio 2013, 35, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminov, R.I. A brief history of the antibiotic era: lessons learned and challenges for the future. Front Microbio 2010, 1, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Arrieta, K.; Matamoros-Montoya, K.; Arias-Echandi, M.L.; Huete-Soto, A.; Redondo-Solano, M. (2021). Presence of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat meat products sold at retail stores in Costa Rica and analysis of contributing factors. J. Food Prot 2021, 84, 1729–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obaidat, M.M.; Kiryluk, H.; Rivera, A.; Stringer, A.P. Molecular serogrouping and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes from local dairy cattle farms and imported beef in Jordan. LWT 2020, 127, 109419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shourav, A.H.; Hasan, M.; Ahmed, S. Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Listeria spp. isolated from cattle farm environment in Bangladesh. J. Agri Food Res 2020, 2, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Sastre, L.; Arroyo, C.; Fox, E.M.; McMahon, B.J.; Bai, L.I.; Li, F.; Fanning, S. Antimicrobial resistance in Listeria species. Microbio Spect 2018, 6, 6–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktorczyk-Kapischke, N.; Skowron, K.; Grudlewska-Buda, K.; Wałecka-Zacharska, E.; Korkus, J.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. Adaptive response of Listeria monocytogenes to the stress factors in the food processing environment. Front Microbio 2021, 12, 710085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielowska, C.; Korsak, D.; Chapkauskaitse, E.; Decewicz, P.; Lasek, R.; Szuplewska, M.; Bartosik, D. Plasmidome of Listeria spp.—The repA-Family Business. Inte J. Mole Sci 2021, 22, 10320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, A.S.; Call, D.R.; Broschat, S.L. PARGT: A software tool for predicting antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Sci rep 2020, 10, 11033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz-Esser, S.; Anast, J.M.; Cortes, B.W. A large-scale sequencing-based survey of plasmids in Listeria monocytogenes reveals global dissemination of plasmids. Front Microbio 2021, 12, 653155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mafuna, T.; Matle, I.; Magwedere, K.; Pierneef, R.E.; Reva, O.N. Whole genome-based characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolates recovered from the food chain in South Africa. Front Microbio 2021, 12, 669287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.K.; Stasiewicz, M.J.; Benjakul, S.; Vongkamjan, K. Genomic analysis of prophages recovered from Listeria monocytogenes lysogens found in seafood and seafood-related environment. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy-Denomy, J.; Qian, J.; Westra, E.R.; Buckling, A.; Guttman, D.S.; Davidson, A.R.; Maxwell, K.L. Prophages mediate defense against phage infection through diverse mechanisms. ISME J. 2016, 10, 2854–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Knabel, S.J. Prophages in Listeria monocytogenes contain single-nucleotide polymorphisms that differentiate outbreak clones within epidemic clones. J. Clin Microbio 2008, 46, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, H.T.K.; Benjakul, S.; Vuddhakul, V.; Vongkamjan, K. Host Range of Listeria Prophages Induced from Lysogenic Listeria Isolates from Foods and Food-related Environments in Thailand. Food App Biosci Inno Techn 2019, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.K.; Benjakul, S.; Vongkamjan, K. Characterization of Listeria prophages in lysogenic isolates from foods and food processing environments. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0214641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza-Mellado, M.D.R.; Vilchis-Rangel, R.E. Review of CRISPR-Cas systems in Listeria species: current knowledge and perspectives. Inte J.Microbio 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafuna, T.; Matle, I.; Magwedere, K.; Pierneef, R.E.; Reva, O.N. Comparative Genomics of Listeria Species Recovered from Meat and Food Processing Facilities. Microbio Spect 2022, 10, e01189–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hupfeld, M.; Trasanidou, D.; Ramazzini, L.; Klumpp, J.; Loessner, M.J.; Kilcher, S. A functional type II-A CRISPR–Cas system from Listeria enables efficient genome editing of large non-integrating bacteriophage. Nucleic acids res 2018, 46, 6920–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveau, H.; Garneau, J.E.; Moineau, S. CRISPR/Cas system and its role in phage-bacteria interactions. Ann Rev Microbio 2010, 64, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchaca, A.; Dos Santos-Neto, P.C.; Mulet, A.P.; Crispo, M. CRISPR in livestock: From editing to printing. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohadi, E.; Azarnezhad, A.; Lotfollahi, L.; Asadollahi, P.; Kaviar, V.H.; Razavi, S.; Sadeghi Kalani, B. Evaluation of Genetic Content of the CRISPR Locus in Listeria monocytogenes Isolated From Clinical, Food, Seafood and Animal Samples in Iran. Cur Microbio 2023, 80, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Flores, J.; Holý, O.; Bustamante, F.; Lepuschitz, S.; Pietzka, A.; Contreras-Fernández, A.; Castillo, C.; Ovalle, C.; Alarcón-Lavín, M.P.; Cruz-Córdova, A.; Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J. Virulence and antibiotic resistance genes in Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated from ready-to-eat foods in Chile. Front Microbio 2022, 12, 796040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Govender, N.; McCarthy, K.M.; Erasmus, L.K.; Doyle, T.J.; Allam, M.; Ismail, A.; Ramalwa, N.; Sekwadi, P.; Ntshoe, G.; Shonhiwa, A. Outbreak of listeriosis in South Africa associated with processed meat. New Eng J.Med 2020, 382, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, I.F. An outbreak of caprine listeriosis in the Western Cape. J. South Afri Vet Asso 1977, 48, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Matle, I.; Mafuna, T.; Madoroba, E.; Mbatha, K.R.; Magwedere, K.; Pierneef, R. Population structure of non-ST6 Listeria monocytogenes isolated in the red meat and poultry value chain in South Africa. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gana, J.; Gcebe, N.; Pierneef, R.E.; Chen, Y.; Moerane, R.; Adesiyun, A.A. Genomic Characterization of Listeria innocua Isolates Recovered from Cattle Farms, Beef Abattoirs, and Retail Outlets in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gana, J. Prevalence, risk factors, and molecular characterization of Listeria species from cattle farms, beef abattoirs and retail outlets in Gauteng, South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Thrusfield, M. Sample size determination. Vet. Epidemiol. 2007, 3, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. Available online: http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.186072.114. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaumeil, P.A.; Mussig, A.J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Parks, D.H. GTDB-Tk: A toolkit to classify genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1925–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. mlst Github. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/mlst (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Jolley, K.A.; Maiden, M.C. BIGSdb: scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, A.; Criscuolo, A.; Pouseele, H.; Maury, M.M.; Leclercq, A.; Tarr, C.; Björkman, J.T.; Dallman, T.; Reimer, A.; Enouf, V. Whole genome-based population biology and epidemiological surveillance of Listeria monocytogenes. Nat. Microbio. 2016, 2, 16185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Abricate, Github. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/abricate (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PloS one 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G. Using ggtree to visualize data on tree-like structures. Curr. Proto. Bioinform. 2020, 69, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, A.P.; Roux, S.; Schulz, F.; Babinski, M.; Xu, Y.; Hu, B.; Chain, P.S.; Nayfach, S.; Kyrpides, N.C. Identification of mobile genetic elements with geNomad. Nat Biotechno 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abby, S.S.; Néron, B.; Ménager, H.; Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P. MacSyFinder: a program to mine genomes for molecular systems with an application to CRISPR-Cas systems. PloS one 2014. 9, e110726. [CrossRef]

- Couvin, D.; Bernheim, A.; Toffano-Nioche, C.; Touchon, M.; Michalik, J.; Néron, B.; Rocha, E.P.; Vergnaud, G.; Gautheret, D.; Pourcel, C. CRISPRCasFinder, an update of CRISRFinder, includes a portable version, enhanced performance and integrates search for Cas proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W246–W251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grissa, I.; Vergnaud, G.; Pourcel, C. (2007). CRISPRFinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic acids res 2007, 35, W52–W57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Team, R. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; RStudio, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Maechler, M. Finding groups in data: Cluster analysis extended Rousseeuw et al. R Package Version 2019, 2, 242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, E.; Schliep, K. ape 5.0: An environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csardi, G.; Nepusz, T. The igraph software package for complex network research. Int. J. Complex Syst. 2006, 1695, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tyner, R.C.; Briatte, F.; Hofmann, H. Network Visualization with ggplot2. R J. 2017, 9, 26–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratil, I. Visualizations with statistical details: The ‘ggstatsplot’ approach. J. Open. Source Soft. 2021, 61, 3167. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, N. ggsci: Scientific journal and Sci-Fi themed color palettes for ‘ggplot2’. In R Package Version; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kaptchouang Tchatchouang, C.D.; Fri, J.; De Santi, M.; Brandi, G.; Schiavano, G.F.; Amagliani, G.; Ateba, C.N. Listeriosis outbreak in South Africa: a comparative analysis with previously reported cases worldwide. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayode, A.J.; Semerjian, L.; Osaili, T.; Olapade, O.; Okoh, A.I. Occurrence of multidrug-resistant Listeria monocytogenes in environmental waters: a menace of environmental and public health concern. Front Envir Sci 2021, 9, 737435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matle, I.; Mbatha, K.R.; Madoroba, E. A review of Listeria monocytogenes from meat and meat products: Epidemiology, virulence factors, antimicrobial resistance and diagnosis. Onderstepoort J. Vet Res 2020, 1–20. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-opvet-v87-n1-a9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurtado, A.; Ocejo, M.; Oporto, B. Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes shedding in domestic ruminants and characterization of potentially pathogenic strains. Vet Microbio 2017, 210, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Hu, P.; Li, Q.; Zhang, S.; Li, H.; Chang, J.; Lu, S. Prevalence and transmission characteristics of Listeria species from ruminants in farm and slaughtering environments in China. Emer Micr Infect 2021, 10, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Amadoro, C.; Conficoni, D.; Giaccone, V.; Colavita, G. Occurrence, diversity of Listeria spp. isolates from food and food-contact surfaces and the presence of virulence genes. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, E.M.; Allnutt, T.; Bradbury, M.I.; Fanning, S.; Chandry, P.S. (2016). Comparative genomics of the Listeria monocytogenes ST204 subgroup. Front Microbio 2016, 7, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennison, A.V.; Masson, J.J.; Fang, N.X.; Graham, R.M.; Bradbury, M.I.; Fegan, N.; Fox, E.M. Analysis of the Listeria monocytogenes population structure among isolates from 1931 to 2015 in Australia. Front Microbio 2017, 8, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, R.; Stephan, R.; Althaus, D.; Brisse, S.; Maury, M.; Tasara, T. (2015). Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated during 2011–2014 from different food matrices in Switzerland. Food Contr 2015, 57, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, J.C.; Mercoulia, K.; Tomita, T.; Easton, M.; Li, H.Y.; Bulach, D.M.; Stinear, T.P.; Seemann, T.; Howden, B.P. 2016. Prospective whole-genome sequencing enhances national surveillance of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Clin Microbio 2016, 54, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, B.; Perich, A.; Gómez, D.; Yangüela, J.; Rodríguez, A.; Garriga, M.; Aymerich, T. Diversity and distribution of Listeria monocytogenes in meat processing plants. Food Microbio 2014, 44, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bespalova, T.Y.; Mikhaleva, T.V.; Meshcheryakova, N.Y.; Kustikova, O.V.; Matovic, K.; Dmitrić, M.; Zaitsev, S.S.; Khizhnyakova, M.A.; Feodorova, V.A. Novel sequence types of Listeria monocytogenes of different origin obtained in the Republic of Serbia. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Doijad, S.; Wang, W.; Lian, K.; Pan, X.; Koryciński, I.; Hu, Y.; Tan, W.; Ye, S.; Wang, Z.; Pan, Z.; Chakraborty, T.; Jiao, X. Genetic Diversity of Listeria monocytogenes Isolates from Invasive Listeriosis in China. Foodborn Path Dis 2020, 17, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centorotola, G.; Ziba, M.W.; Cornacchia, A.; Chiaverini, A.; Torresi, M.; Guidi, F.; Cammà, C.; Bowa, B.; Mtonga, S.; Magambwa, P.; D'Alterio, N.; Scacchia, M.; Pomilio, F.; Muuka, G. Listeria monocytogenes in ready to eat meat products from Zambia: phenotypical and genomic characterization of isolates. Front Microbio, 2023; 14, 1228726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myintzaw, P.; Pennone, V.; McAuliffe, O.; Begley, M.; Callanan, M. Association of Virulence, Biofilm, and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes with Specific Clonal Complex Types of Listeria monocytogenes. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiavano, G.F.; Ateba, C.N.; Petruzzelli, A.; Mele, V.; Amagliani, G.; Guidi, F.; De Santi, M.; Pomilio, F.; Blasi, G.; Gattuso, A.; Di Lullo, S.; Rocchegiani, E.; Brandi, G. 2021. Whole-Genome Sequencing Characterization of Virulence Profiles of Listeria monocytogenes Food and Human Isolates and In Vitro Adhesion/Invasion Assessment. Microorganisms 2021, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Meng, F.; Deng, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Jiao, X.; Li, S.; Liu, M. Genomic epidemiology of hypervirulent Listeria monocytogenes CC619: Population structure, phylodynamics and virulence. Microbio Res 2024, 280, 127591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madden, R.H.; Hutchison, M.; Jordan, K.; Pennone, V.; Gundogdu, O.; Corcionivoschi, N. 2018. Prevalence and persistence of Listeria monocytogenes in premises and products of small food business operators in Northern Ireland. Food Contr 2018, 87, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melero, B.; Stessl, B.; Manso, B.; Wagner, M.; Esteban-Carbonero, O.J.; Hernandez, M.; Rovira, J.; Rodriguez-Lazaro, D. Listeria monocytogenes colonization in a newly established dairy processing facility. Inter J. Food Microbio 2019, 289, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, L.; Cooley, M.B.; Oryang, D.; Carychao, D.; Nguyen, K.; Luo, Y.; Weinstein, L.; Brown, E.; Allard, M.; Mandrell, R.E.; Chen, Y. Prevalence and Clonal Diversity of over 1,200 Listeria monocytogenes Isolates Collected from Public Access Waters near Produce Production Areas on the Central California Coast during 2011 to 2016. Appl Envi Microbio 2022, 88, e00357-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenal-Francisque, V.; Lopez, J.; Cantinelli, T.; Caro, V.; Tran, C.; Leclercq, A.; Lecuit, M.; Brisse, S. Worldwide distribution of major clones of Listeria monocytogenes. Emer Inf Dis 2011, 17, 1110–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matle, I.; Mbatha, K.R.; Lentsoane, O.; Magwedere, K.; Morey, L.; Madoroba, E. Occurrence, serotypes, and characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes in meat and meat products in South Africa between 2014 and 2016. J. Food Saf. 2019, 39, e12629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomáštíková, Z.; Gelbíčová, T.; Karpíšková, R. Population structure of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from human listeriosis cases and from ready-to-eat foods in the Czech Republic. J.Food Nutr Res 2019, 58, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Segerman, B. The most frequently used sequencing technologies and assembly methods in different time segments of the bacterial surveillance and RefSeq genome databases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbio. 2020, 10, 527102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Boland, J.A.; Kuhn, M.; Berche, P.; Chakraborty, T.; Domı́nguez-Bernal, G.; Goebel, W.; González-Zorn, B.; Wehland, J.; Kreft, J. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin Microbio Rev 2001, 14, 584–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmour, M.W.; Graham, M.; Van Domselaar, G.; Tyler, S.; Kent, H.; Trout-Yakel, K.M.; Larios, O.; Allen, V.; Lee, B.; Nadon, C. High-throughput genome sequencing of two Listeria monocytogenes clinical isolates during a large foodborne outbreak. BMC Geno 2010, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matle, I.; Pierneef, R.; Mbatha, K.R.; Magwedere, K.; Madoroba, E. Genomic diversity of common sequence types of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from ready-to-eat products of animal origin in South Africa. Genes 2019, 10, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centorotola, G.; Ziba, M.W.; Cornacchia, A.; Chiaverini, A.; Torresi, M.; Guidi, F.; Cammà, C.; Bowa, B.; Mtonga, S.; Magambwa, P.; D’Alterio, N. Listeria monocytogenes in ready to eat meat products from Zambia: phenotypical and genomic characterization of isolates. Front Microbio 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayode, A.J.; Okoh, A.I. Assessment of the molecular epidemiology and genetic multiplicity of Listeria monocytogenes recovered from ready-to-eat foods following the South African listeriosis outbreak. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 20129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.; Zaiser, A.; Leitner, R.; Quijada, N.M.; Pracser, N.; Pietzka, A.; Ruppitsch, W.; Schmitz-Esser, S.; Wagner, M.; Rychli, K. Virulence characterization and comparative genomics of Listeria monocytogenes sequence type 155 strains. BMC Geno 2020, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Ji, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, W.; WANG, F.; Huang, X. Molecular Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes Strains Isolated from imported Food in China from 14 countries/regions, 2003-2018. Front Cell Infect Microbio 2023, 13, 1287564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manqele, A. Prevalence and characterization of Salmonella spp. in slaughter cattle, abattoir environment, and meat sold at retail outlets in Gauteng, South Africa. University of Pretoria, South Africa. 2018.

- Onyeka, L.O.; Adesiyun, A.A.; Keddy, K.H.; Madoroba, E.; Manqele, A.; Thompson, P.N. Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli contamination of raw beef and beef-based ready-to-eat products at retail outlets in Pretoria, South Africa. J. Food Prot 2020, 83, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phung, T.; Tran, T.; Pham, D.; To, A.; Le, H. Occurrence and molecular characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from ready-to-eat meats in Hanoi, Vietnam. Italian J. Food Saf 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durso, L.M.; Cook, K.L. Impacts of antibiotic use in agriculture: what are the benefits and risks? Curr 0pin Microbio 2014, 19, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henton, M.M.; Eagar, H.A.; Swan, G.E.; Van Vuuren, M. Part VI. Antibiotic management and resistance in livestock production. SAMJ: South Afric Med J 2011, 101, 583–586. [Google Scholar]

- Van, T.T.H.; Yidana, Z.; Smooker, P.M.; Coloe, P.J. Antibiotic use in food animals worldwide, with a focus on Africa: Pluses and minuses. J. Glob Antimicro Resis 2020, 20, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scortti, M.; Han, L.; Alvarez, S.; Leclercq, A.; Moura, A.; Lecuit, M.; Vazquez-Boland, J. Epistatic control of intrinsic resistance by virulence genes in Listeria. PLoS Genetics 2018, 14, e1007525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, M.I.; Vázquez, S.; Cornejo, C.; D'Alessandro, B.; Braga, V.; Caetano, A.; Betancor, L.; Varela, G. Does Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes contribute significantly to the burden of antimicrobial resistance in Uruguay? Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 583930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanes, R.M.; Huang, Z. Investigation of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Listeria monocytogenes from 2010 through to 2021. Inte J. Envir Res Pub Health 2022, 19, 5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salyers, A.A.; Amabile-Cuevas, C.F. Why are antibiotic resistance genes so resistant to elimination? Antimicro Agents Chemo 1997, 41, 2321–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hingston, P.; Brenner, T.; Truelstrup Hansen, L.; Wang, S. Comparative analysis of Listeria monocytogenes plasmids and expression levels of plasmid-encoded genes during growth under salt and acid stress conditions. Toxins 2019, 11, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebrun, M.; Loulergue, J.; Chaslus-Dancla, E.; Audurier, A. Plasmids in Listeria monocytogenes in relation to cadmium resistance. Appl Enviro Microbio 1992, 58, 3183–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Hoffmann, M.; Allard, M.W.; Brown, E.W.; Chen, Y. Microevolution and gain or loss of mobile genetic elements of outbreak-related Listeria monocytogenes in food processing environments identified by whole genome sequencing analysis. Front Microbio 2020, 11, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, P.; Wang, Y.; Gan, L.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Ji, S.; Song, Z.; Jiang, H.; Ye, C. Function and distribution of the conjugative plasmid pLM1686 in foodborne Listeria monocytogenes in China. Inte J. Food Microbio 2021, 352, 109261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpentier, E.; Gerbaud, G.; Courvalin, P. Conjugative mobilization of the rolling-circle plasmid pIP823 from Listeria monocytogenes BM4293 among gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacterio 1999, 181, 3368–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scortti, M.; Han, L.; Alvarez, S.; Leclercq, A.; Moura, A.; Lecuit, M.; Vazquez-Boland, J. Epistatic control of intrinsic resistance by virulence genes in Listeria. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007525, Erratum in: PLoS Genet. 2018 Oct 15;14(10):e1007727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, H.; Ye, L.; Yan, H.; Meng, H.; Yamasak, S.; Shi, L. Comparative analysis of CRISPR loci in different Listeria monocytogenes lineages. Biochem Biophy Res Comm 2014, 454, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuenne, C.; Billion, A.; Mraheil, M.A.; Strittmatter, A.; Daniel, R.; Goesmann, A.; Barbuddhe, S.; Hain, T.; Chakraborty, T. Reassessment of the Listeria monocytogenes pan-genome reveals dynamic integration hotspots and mobile genetic elements as major components of the accessory genome. BMC Geno 2013, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, C.; Brown, P.; Kathariou, S. Use of bacteriophage amended with CRISPR-Cas systems to combat antimicrobial resistance in the bacterial foodborne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Industry | No. of samples tested |

No. (%) positive for L. monocytogenes |

No. of isolates tested |

No. (%) of isolates L. monocytogenes that belong to ST: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST1 | ST2 | ST14 | ST31 | ST204 | ST224 | ST876 | ||||

| Cattle farms a | 328 | 11 (3.4) | 11 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (18.2) | 6 (54.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (27.3) |

| Abattoirs b | 262 | 12 (4.6) | 12 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | 7 (58.3) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) |

| Retail outlets c | 400 | 37 (9.3) | 37 | 4 (10.8) | 12 (32.4) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.7) | 15 (40.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.1) |

| p-value | 0.002 | 0.560 | 0.044 | 1 | 0.134 | 0.475 | 1 | 0.204 | ||

| Total | 990 | 60 (6.1) d | 60 | 4 (6.7) | 13 (21.7) | 2 (3.3) | 5 (8.3) | 28 (46.7) | 1 (1.7) | 7 (11.7) |

| Characteristics of seven L. monocytogenes isolates recovered from RTE products: | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate ID# | CFSAN117454 | CFSAN117466 | CFSAN117473 | CFSAN117497 | CFSAN117498 | CFSAN117503 | CFSAN117545 |

| Source | Chain-Retail | Chain-Retail | Chain-Retail | Chain-Retail | Large-Retail | Medium-Retail | Small-Retail |

| Sample type | Vienna | Biltonga | Beef polonyb | Beef polonyb | Beef polonyb | Beef polonyb | Beef polonyb |

| Serogroup | IVb | Ivb | IVb | 11a | 11a | 11a | IVb |

| MLST | 876 | 2 | 2 | 204 | 204 | 204 | 1 |

| Clonal complex | 1 | 2 | 2 | 204 | 204 | 204 | 1 |

| No. of virulence factors | 39 | 32 | 32 | 35 | 34 | 34 | 39 |

| LIPI-1 | Positivec | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positived | Positivee |

| Internalins A&B | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| LIPI-3 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Othersf | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| AMR gene: FosX | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| AMR gene: vga(G) | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| AMR Plasmid | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| CRISPR-cas | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Proviruses | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| aBiltong: A delicacy made of spiced dried raw meat (beef and game) widely consumed in the country | |||||||

| bBeef polony: A popularly consumed product responsible for the 2018-2019 large outbreak of human listeriosis in South Africa | |||||||

| cOf the six LIPI-1 virulence, negative for the actA gene | |||||||

| dOf the six LIPI-1 virulence, negative for the hly gene | |||||||

| eOf the six LIPI-1 virulence, negative for the actA gene | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).