1. Introduction

Arbovirus infections correspond to viral infections caused by several viruses transmitted by hematophagous arthropods, which have emerged worldwide [

1]. There is a great variety of these viruses in the Amazon Rainforest, regarded as the world’s largest reservoir of arboviruses due to its rich biodiversity of arthropod vectors and wild vertebrates, which are the hosts for these viruses, besides having favorable climatic conditions for the maintenance of the life cycles of arboviruses [

2].

In this scenario, more than thirty types of arboviruses have already been associated with diseases in humans in the Brazilian Amazon, including dengue (DENV), yellow fever (YFV), Zika (ZIKV), chikungunya (CHIKV), Oropouche (OROV) and Mayaro (MAYV) [

2,

3]. For example, the OROV (

Orthobunyavirus,

Peribunyaviridae) causes a disease called Oropouche fever, which can lead to symptoms such as fever, headache, myalgia, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, arthralgia, photophobia, retro-ocular pain, rash, and hemorrhagic signs. After the recovery, in some cases, the disease recurs. A few cases develop into Aseptic meningitis [

4]. The OROV circulates mainly in Central and South America, causing human outbreaks [

5]. The OROV circulates in wild and urban environments. Sylvatically, the virus is transmitted by

Aedes serratus and

Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes to marsupials, sloths, primates, and birds. In contrast, in urban environments, the OROV is transmitted by

Culicoides paraensis insects to humans, the primary host [

6].

Arbovirus infections can be asymptomatic or symptomatic. The symptomatic clinical forms can manifest themselves in different levels of clinical intensity, from oligosymptomatic to more severe conditions. It is worth noting that the same arbovirus can determine different clinical syndromes and, on the other hand, the same symptomatology can be determined by various types of arboviruses due to factors such as viral titer, time of exposure, virus strain, and individual resistance [

7,

8].

Regarding the factors of individual resistance that can alter the intensity of the symptomatology of arboviruses, the individual’s dietary pattern plays a role since the immune response is dependent upon cell replication and the synthesis of active protein compounds and is, therefore, strongly affected by the nutritional status of the individual, which determines the cellular metabolic ability and the efficiency at which the cell reacts to stimuli, thus initiating and perpetuating the system of organic protection and self-repair [

9].

In this regard, calories, amino acids, vitamins A, D, E, pyridoxine, cyanocobalamin, folic acid, iron, zinc, copper, magnesium, and selenium are some of the nutrients for which a close relationship has already been established between their organic status and immune system function [

9]. Nonetheless, the effect of individual nutrients has progressively been shown to be insufficient to explain the relationship between food and health. Several studies have shown that the beneficial effect on disease prevention stems from the food itself and from combinations of nutrients and other chemical compounds that are part of the food matrix rather than single nutrients [

10].

Thus, by taking into consideration the impact of arboviruses on public health in Brazil and in the world and the importance of nutrients and food for strengthening the body’s defenses against diseases and acceptable minimization of symptoms, this study aimed to investigate the possible association between the occurrence of clinical manifestations caused by arboviruses and the dietary pattern of the population under study.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was analytical, cross-sectional, and quantitative and conducted in the Expedito Ribeiro settlement, located in the rural area of Santa Bárbara do Pará, in Pará State, which has a population estimated at approximately 120 families, according to information from the settlement’s neighborhood association, about 600 hectares in size, 80% of which being native forests (legal reserve).

The population under study included residents of the Expedito Ribeiro Settlement of both genders and any age group who were investigated during a febrile outbreak in the area from January to February 2018. Symptomatic individuals and asymptomatic individuals at the time of recruitment who reported having had signs and symptoms within an interval of up to three months before the date of the investigation were included in this study to identify recent infection by testing for IgM antibodies to certain arboviruses. Symptomatic individuals not infected by arboviruses were excluded, as well as those with incomplete data, who had moved from the settlement, or who were not located, thus making it impossible to apply the food frequency questionnaire.

Therefore, the study sampling was made up of 95 individuals. Blood samples were taken for laboratory analysis of arbovirus infections, of which 40 were asymptomatic, each living with or near febrile cases, and 55 participants were symptomatic. Virological exams were performed for the samples collected up to the fifth day after the onset of symptoms: viral isolation in cell cultures and genome detection by real-time RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) for Dengue, Zika, Mayaro, and Chikungunya. Serological tests were performed for samples collected after the fifth day from the onset of symptoms: in-house IgM Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)/Dengue, Zika, Mayaro (MAYV), Chikungunya (CHIKV), and Oropouche and Hemagglutination Inhibition assays (including a panel of 18 types of arboviruses of different genera: Alphavirus (Eastern equine encephalitis, Western equine encephalitis, Mayaro, and Mucambo/MUCV), Flavivirus (West Nile, Yellow Fever, Ilheus, Saint Louis Encephalitis, Rocio, Zika, Dengue serotypes 1, 2, 3, 4) and Orthobunyavirus (Tacaiuma, Oropouche, Catu) [

11].

Moreover, a clinical epidemiological form from the Brazilian Notification Disease Information System (SINAN) [

12] for arboviruses was applied, aiming to obtain information such as the epidemiological profile and the clinical manifestations, which were used in performing the statistical analyses between clinical manifestations and dietary pattern.

To collect dietary pattern data, a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) (Supplementary

Figure 1) was used, which included food options from the different food groups, with the respective indication of intake frequency, with the possibility of indicating the number of portions eaten and the method or type of preparation.

The dietary pattern was evaluated by analyzing food intake by food groups of the population being studied in comparison with the daily values recommended by the Brazilian Ministry of Health [

13] for eight food group categories, namely: 1) Cereals, tubers, roots and derivatives; 2) Beans; 3) Fruits and natural fruit juices; 4) Vegetables; 5) Milk and milk derivatives; 6) Meats and eggs; 7) Oils, fats and oilseeds; 8) Sugars and sweets. The number of portions recommended for each food group can be observed in

Table 1.

The food frequency was analyzed according to five categories, based on the adjustment in the consumption of food groups, according to the recommendations of the Brazilian Ministry of Health [

8], as follows: 1) Very Poor; 2) Bad; 3) Regular; 4) Good; 6) Excellent (

Table 2).

The chi-square test (χ2) was performed for the statistical analysis, followed by the β test, to indicate the need to apply the correspondence analysis technique for the data that exhibited statistical significance. This technique seeks to study the relationship between qualitative variables, thus allowing for visualizing frequency associations amongst the categories of the variables.

The statistical analyses were performed at the Statistical Package for Social Science - SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, 1999) and Minitab 19®. The significance level established for all the tests was 5% (p < 0.05).

3. Results

Out of the 95 individuals investigated, more than half (52.63%) were female, with a predominance of the 24-34 age group (18.96%), with just over a third (36.83%) working as farmers. The average age was 36 years, the minimum was two years, and the maximum was 79 years.

The biological materials (blood and serum) submitted to the various laboratory tests allowed for the diagnosis of the cases investigated, and they were classified as positive or negative for arbovirus. From this perspective, out of the 95 individuals studied in the outbreak, slightly more than half (50.53%) were classified as positive, 87.50% of which were symptomatic and 12,5 % asymptomatic.

After all the laboratory tests were performed, it was identified that the febrile outbreak in the mentioned Settlement in 2018 was due to OROV (47.37 %). There were also isolated cases of MAYV infection (1.05 %) and co-infection by OROV and CHIKV (2.11%) [

11].

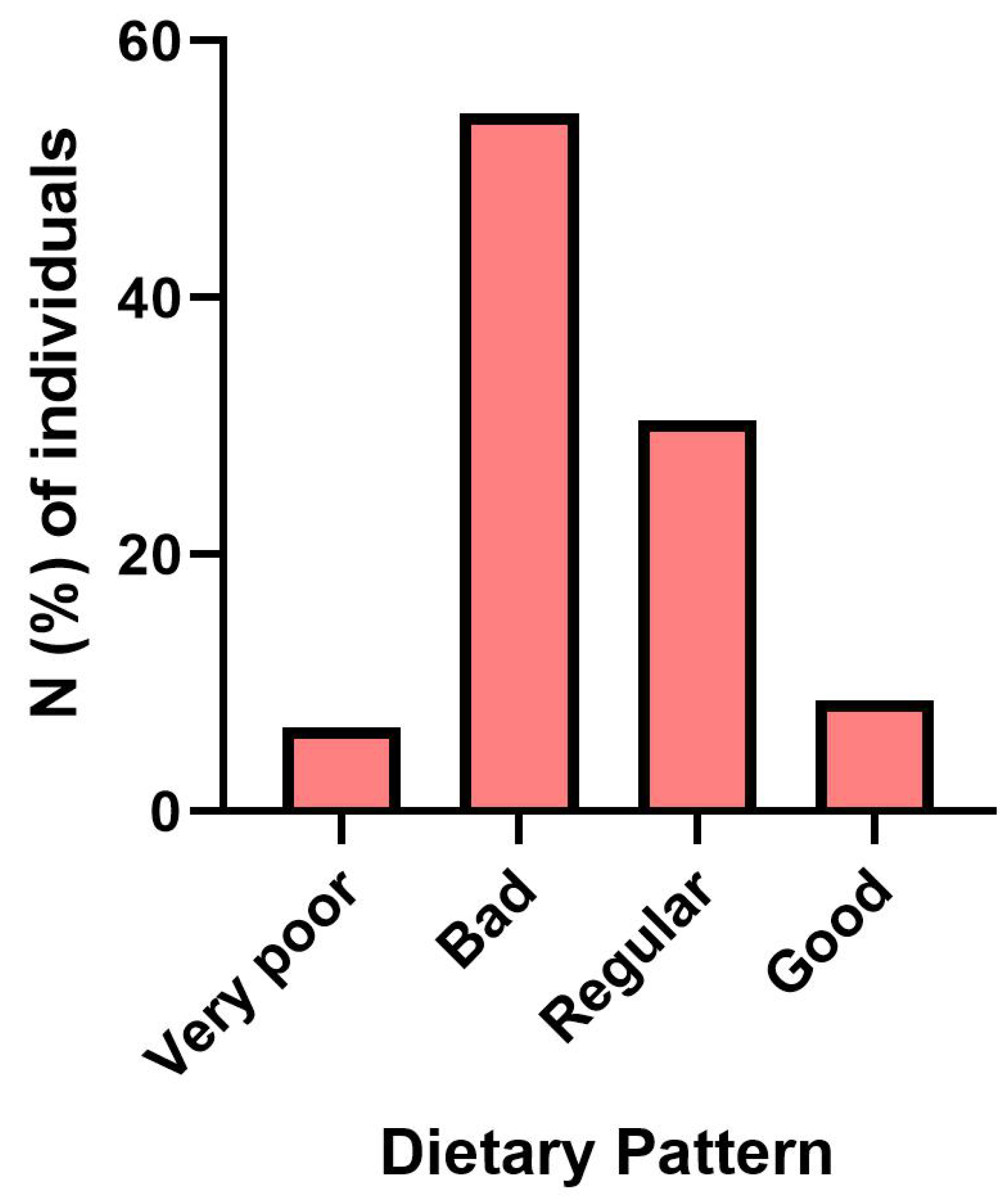

Six of the 48 positive cases were asymptomatic, and 42 were symptomatic. Regarding the dietary pattern, from the 48 cases of positives, we were able to interview 46 cases. After analyzing the frequency of food intake per food type, the frequency of food intake per food group, and the intake of daily portions per food group according to the recommendations of the Brazilian Ministry of Health, it was possible to conclude that out of the 46 individuals being analyzed, the vast majority (91.30%) had a dietary pattern regarded as inadequate, with 6.52% being very poor, 54.35% bad, 30.43% regular and 8.70% good. It is worth noting that no records of a dietary pattern were classified as excellent (

Figure 1).

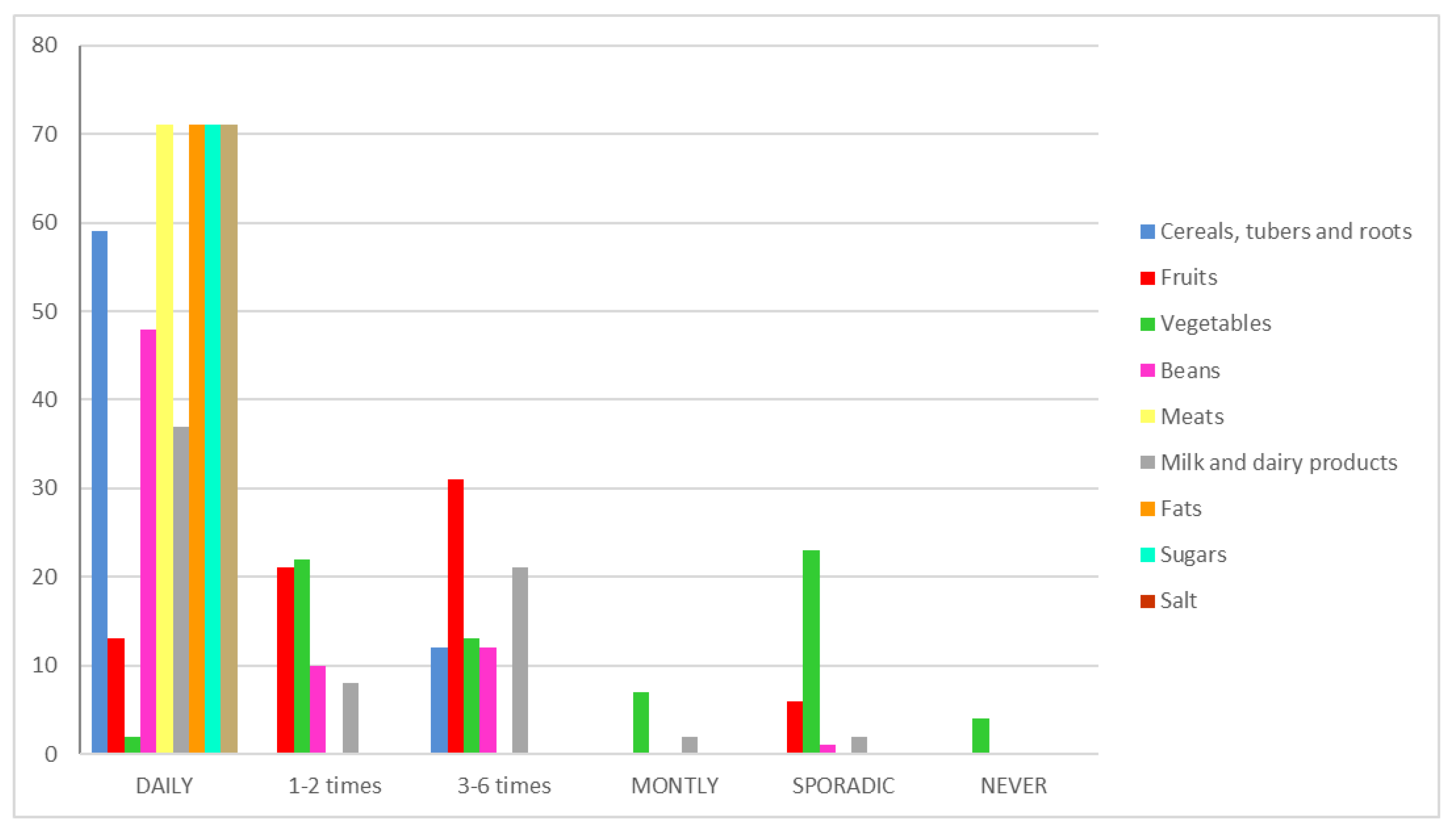

After analyzing the food frequency of the population of the settlement, it was possible to observe a low frequency of consumption of processed foods, such as canned foods, soft drinks, biscuits, processed juice, industrialized seasoning, and mayonnaise, as well as low consumption of ready-to-eat snacks, such as pizza, snacks, and sandwiches. On the other hand, it was observed that the basis of this population’s diet consists of cassava flour, rice, bread, eggs, beans, natural seasonings, vegetable oil, refined sugar, tapioca, various types of meat (beef, pork, poultry, fish, offal, and sausages), seasonal fruits and natural fruit juice (

Figure 2).

We also identified some foods that are not part of the eating habits of this population, such as dairy products (cheese, yogurt, cottage cheese), vegetables (lentils, peas, chickpeas, fava beans, and soybeans), mayonnaise, alcoholic beverages, nuts and tacacá (an Amazonian delicacy) (

Figure 2).

After characterizing the laboratory results, clinical manifestations, and dietary pattern classification, we statistically compared the food pattern classification according to the presence or absence of symptoms using the chi-square test to identify possible associations. Our results showed that the food pattern classification ‘bad’ was the most frequent, with statistical significance since p<0.05 (

Table 3).

Since statistical significance was identified in the previous association, a complementary analysis, called correspondence analysis, was performed to identify which dietary pattern is more associated with symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. In this regard,

Table 4 shows that symptomatic individuals are more associated with bad dietary patterns, with a 96.06% confidence level. In contrast, asymptomatic individuals are more associated with good dietary patterns, with a 79.03% confidence level (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Our results indicate an association between dietary patterns and the development of Oropouche fever symptoms during the febrile outbreak that occurred in the Expedito Ribeiro Settlement in Santa Bárbara do Pará, Pará state, Brazil, in 2018, mainly caused by OROV, although there were also two isolated cases of CHIKV and MAYV. We showed that a bad dietary profile is associated with symptomatic cases of Oropouche fever, while a good one is associated with asymptomatic cases. Our study is one of the few published studies associating dietary patterns and arbovirus symptomatology. This highlights the importance of nutrition as a protective factor for developing symptoms caused by the arboviruses, specifically the OROV.

Most of the studied population lives out of farming activities, which promotes contact with arbovirus vectors, thus prompting a sylvan outbreak by OROV in 2018 since the virus has already been detected in this area and surrounding municipalities. The Amazon Region provides highly favorable conditions for the OROV in nature, and this virus is transmitted by some vectors, especially the Culicoides paraensis (‘midge’), which in rural cycles has natural breeding sites such as barks exposed to the weather and that accumulate water in cocoa and other fruit crops.

Freitas and colleagues (1982) [

14] conducted a study during an OROV outbreak in the municipality of Santa Izabel, in Pará State, in 1979. They observed that the ratio between symptomatic and asymptomatic cases was about 2:1, with 63% of symptomatic individuals being identified. Interestingly, most OROV infections are of the symptomatic type, which was also observed in the herein study, with 87% of the OROV cases being of the symptomatic type.

Regarding dietary pattern, although the diet basis of the population under study is made up of more natural/healthier foods, with low consumption of processed foods, most of the study population did not have an appropriate dietary pattern since the analysis of the daily intake of food groups by portion recommended by the Brazilian Ministry of Health identified several inadequacies, and some groups – such as cereals, tubers, roots, and derivatives – were consumed in a larger number of servings than recommended. In contrast, the group of vegetables was consumed in a very low number of servings or not consumed at all. Interestingly, the metropolitan area of Belém (Pará State, Brazil) is a place with a wide variety of regional foods and a diversity of nutrients, and the study site is a settlement of farmers who work in farming.

These changes cause inadequacies in the dietary pattern. They can negatively impact a population’s health and quality of life since macronutrients and micronutrients are essential for the proper functioning of the immune system. Numerous nutritional states, such as malnutrition, obesity, and micronutrient deficiencies, can negatively impact the immune function. These immune dysfunctions can then lead to changes in host susceptibility or severity of infection [

15].

The studied population consumes a greater quantity of portions of cereals, tubers, roots, and derivatives, which may be related to the low cost and ease of access, as well as the cultural influence of these foods on the dietary pattern, as is the case of rice and flour of cassava. Although this food group contributes most to the energy supply, excessive consumption can lead to health problems, such as excess weight, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and high blood pressure, among other chronic non-communicable diseases.

When we analyzed the personal morbid antecedents of the studied population, arterial hypertension and diabetes were among the most frequent morbidities, given that they may be related to the inadequate daily consumption of portions of food, especially from the cereal and tubers group, as they are rich in simple carbohydrates and poor in fiber, causing constant glycemic changes that, if not adequately monitored, can generate insulin resistance with subsequent progression to diabetes, in addition to hypertension and other chronic non-communicable conditions.

In this regard, when analyzing the comparisons between the dietary pattern and other results of the laboratory tests for arbovirus, we identified that there was a statistical association (p<0.05) between clinical manifestations and dietary pattern so that those who had a better, more adequate dietary pattern did not develop symptoms, even though they were positive cases, as observed in the six asymptomatic positive cases of OROV.

Furthermore, when analyzing eight cases who reported they had Mayaro fever during a 2008 outbreak, we observed that one of the asymptomatic cases for this 2018 outbreak had a dietary pattern rated as good, and the other three asymptomatic cases were rated as regular. On the other hand, when the dietary pattern of symptomatic individuals for the 2018 outbreak who also had Mayaro fever in 2008 was analyzed, the classification of the dietary pattern ranged from very poor to bad, thus corroborating the result that dietary pattern influences the onset of clinical manifestations.

Similar data was found by Mishra and colleagues (2017) [

16] when studying 300 patients with dengue fever who had various health complications such as malnutrition, electrolyte imbalance, and insufficient dietary intake. After being admitted to the hospital, these patients were treated with diet and medication, and the diet was hyper-protein, low-fat, and non-spicy. They were given liquids more frequently and in larger quantities. The study results showed that diet therapy restored food intake and favored nutritional status and electrolyte balance recovery.

These data strengthen the importance of an adequate diet for the prevention and fast recovery of organic homeostasis, not only to non-transmissible chronic diseases but also to infectious diseases that have not been well investigated and are associated with food and nutrition. It should be noted that the research herein is one of the few studies addressing the association between the occurrence of arboviruses and food and should serve as a benchmark and stimulus for new studies since these diseases are recurrent in the country. Some are endemic to the Amazon region.

Furthermore, these data draw attention to the need to strengthen public policies that promote not only the avoidance of fast-food consumption but also reinforce the adequate daily consumption of the different food groups according to the official guides and the food pyramid. In addition, it is necessary to foster nutritional education activities to make the population aware of the importance and quality of local foods and their contribution to health and disease prevention.

5. Conclusions

Therefore, we concluded that an association was found between dietary patterns and the development of Oropouche fever-related symptoms, thus characterizing food as a protective factor against the development of clinical manifestations in Oropouche infections. However, further studies are required.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.C. (1º author) and L.M.; methodology, V.C. (1º author), R.A.; validation, R.A., P.V., L.M.; investigation, V.C. (1º author), R.A.; data curation, V.C. (1º author); writing—original draft preparation, V.C. (1º author); writing—review and editing, V.C., P.V., L.M; visualization, V.C. (1º author) and V.C..; supervision, L.M.; funding acquisition, L.M and P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Evandro Chagas Institute.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research of Instituto Evandro Chagas (CEP/IEC) (protocol code 3.259.808). All participants were informed about the study and signed an informed consent form authorizing the use of their data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the entire team of the Arbovirology and Hemorrhagic Fevers Department of the Evandro Chagas Institute for performing the laboratory tests and to the health agents of the Expedito Ribeiro Settlement, especially Joelma, and Ivanilson.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weaver, S.C.; Reisen, W.K. Present and future arboviral threats; 2010; Vol. 85; ISBN 4097472429.

- Donalisio, M.R.; Freitas, A.R.R.; Zuben, A.P.B. Von Arboviruses emerging in Brazil: challenges for clinic and implications for public health. Rev. Saude Publica 2017, 51, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amerasinghe, F.P.; Chua, K.B.; Daszak, P.; Hyatt, A.D.; Molyneux, D.; Thomson, M.; Yameogo, D.L.; Mwelecele-Malecela-Lazaro; Vasconcelos, P. ; Rubio-Palis, Y. Survey of wild food plants for human consumption in Elaziğ (Turkey). Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2005, 14, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sakkas, H.; Bozidis, P.; Franks, A.; Papadopoulou, C. Oropouche Fever: A Review. Viruses 2018, 10, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Rosa, J.F.T.; De Souza, W.M.; de Paula Pinheiro, F.; Figueiredo, M.L.; Cardoso, J.F.; Acrani, G.O.; Nunes MR, T. Oropouche virus: clinical, epidemiological, and molecular aspects of a neglected Orthobunyavirus. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2017, 96, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro FP, Travassos da Rosa APA, Travassos da Rosa JFS, et al. Oropouche Virus: I. A Review of Clinical, Epidemiological, and Ecological Findings. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1981, 30, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, P.F.; Rosa, A.P.A.T. da; Degallier, N.; Rosa, J.F.S.T. da; Pinheiro, F.P. Clinical and ecoepidemiological situation of human arboviruses in Brazilian Amazonia. Ciênc. cult. (Säo Paulo) 1992, 44, 117–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, P.F.C.; Travassos da Rosa, A.P.A.; Pinheiro, F.P.; Shope, R.E.; Travassos da Rosa, J.F.S.; Rodrigues, S.G.; Degallier, N.; Da, T.; Rosa, E.S. Arboviruses pathogenic for man in Brazil. An Overv. Arbovirology Brazil Neighb. countries. 1998, 72–99. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetto, M.A.; Gomes, M.D.O.S.; Jeremias, J.T.; Oliveira, L.D.; Carciofi, A.C. Imunonutrição: o papel da dieta no restabelecimento das defesas naturais. Acta Scien Vet. 2007, 35, 230–232. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil Guia Alimentar para a População Brasileira Guia Alimentar para a População Brasileira; 2014; ISBN 9788561091699.

- Carvalho, V.L.; Azevedo, R.S.S.; Carvalho, V.L.; Azevedo, R.S.; Henriques, D.F.; Cruz, A.C.R.; Vasconcelos, P.F.C.; Martins, L.C. Arbovirus outbreak in a rural region of the Brazilian Amazon. J Clin Virol. 2022, 150-151, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SINAN. Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação. Ficha de Investigação Febre do Nilo e outras arboviroses de importância em Saúde Pública. Available in: https://portalsinan.saude.gov.br/images/documentos/Agravos/Febre_do_Nilo/FEBRE_DO_NILO.pdf Accessed: 03/30/24.

- Brasil. Guia alimentar para a população brasileira; 2008; ISBN 8533411545.

- Freitas, R.B.; Pinheiro, F.P.; Santos, M.A. V; Travassos da Rosa, A.P.A.; Travassos da Rosa, J.F.S.; Freitas, E.N. de Epidemia de vírus ouopouche no leste do Estado do Pará, 1979. Rev. da Fundação SESP 1982, XXV, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Weger-Lucarelli, J.; Auerswald, H.; Vignuzzi, M.; Dussart, P.; Karlsson, E.A. Taking a bite out of nutrition and arbovirus infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Agrahari, K.; Shah, D.K. Prevention and control of dengue by diet therapy. Int. J. Mosq. Res. 2017, 4, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).