Introduction

Contextualizing Human-Wildlife Conflict (HWC)

Human-wildlife conflict (HWC) poses a significant global challenge, arising from the competition between humans and wildlife for resources and space (Nyhus, 2016). The expansion of human populations, agricultural activities, and technological advancements exacerbate this issue, historically leading to the decline or eradication of various species. Understanding these patterns is complex due to the interplay of biological and behavioral factors, compounded by seasonal changes and resource availability (Soulsbury and White, 2015). In recent years, a paradigm shift from conflict to coexistence has occurred, driven by heightened awareness of biodiversity and the implementation of conservation efforts (Treves and Karanth, 2003; Woodroffe et al., 2005). Despite these advancements, the influence of social factors such as religion and cultural beliefs on human-wildlife conflict is often overlooked (Dickman, 2010). Cultural narratives and religious practices significantly shape perceptions and attitudes, as evident in regions like Asia where primate species, including Bonnet Macaques, are revered yet face conflict due to their commensal nature (Singh and Rao, 2004; Prokop et al., 2009).

Bonnet Macaques: A Spotlight on their Role in HWC

Within regions of India and its neighbouring territories, several macaque species coexist with humans as commensals. The Bonnet Macaques in South India is a typical example. Bonnet Macaques are large, endemic, habitat-generalist macaques native to South India. They prefer human-dominated habitats, particularly along roadsides where vegetation provides cover and are well-known crop raiders (Sugiyama, 1971; Singh and Rao, 2004). Therefore, conflicts with humans have resulted in injuries, unplanned translocations and killings of macaques (Sugiyama, 1971; Kumara et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2011). In recent decades, the Bonnet Macaque population has experienced a significant decline attributed to the 'range extension' of Rhesus Macaques. Habitat loss and fragmentation further contribute to this decline, as human-wildlife conflict prompts the translocation and elimination of Bonnet Macaques from affected areas. Several studies have reported decline of the populations in forest habitat. However, long-term monitoring of populations has revealed that Bonnet Macaques have become extinct from high-conflict areas as a result of culling (Singh and Rao, 2004; Singh et al., 2011).

The importance of cultural and religious protection around temples and sacred sites serves as a means for primate survival in Asia, where monkeys are revered and safeguarded near places of worship (Southwick and Siddiqi, 1994). However, severe resource conflicts may lead to hostile encounters, putting these revered animals at risk of attack and even death (Singh and Rao, 2004). Several primate species in India hold strong religious significance, being revered as deities (Radhakrishna, 2013). Similar to numerous Asian countries, India experiences widespread human-wildlife conflict with primates featuring prominently in such conflicts (Anand and Radhakrishna, 2017).

Bridging Gaps in Understanding Sustainable Coexistence

This study aims to address these complexities, examining public attitudes towards human-monkey conflict in temple premises through structured questionnaires. By investigating the socio-economic factors influencing these conflicts and delving into the unique context of the sacred grove, this research strives to contribute valuable insights. Through comprehensive exploration, this study not only enhances our understanding of the delicate balance between human practices and wildlife conservation but also serves as a model for coexistence between humans and other commensal species. The findings from this research are expected to inform strategies that promote sustainable coexistence, fostering harmony between humans and wildlife in landscapes dominated by human activities.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

The research was conducted within the premises of Sree Thurayil Kavu Bhagavathi Temple (11.3012° N, 75.8513° E) located at Kuruvattoor village, Karanthur, Kozhikode, Kerala. The temple sits within a ten-acre sacred grove inhabited by monkeys and is situated near the Punoor river, covering approximately 17.94 square kilometers (6.93 square miles) with an elevation of 5 meters (16 feet) above sea level. The temple houses a Swayambhu shila, a stone sculpture of divine appearance, and worships Hanuman as one of the Upa Devatas. A unique practice, ‘Prasadamootu,’ involves providing food offerings to monkeys as a part of temple rituals, symbolizing the close association between Hanuman and the monkeys in the temple ecosystem. This location was chosen due to its scenic beauty, attracting a significant number of human visitors, and the existing human-monkey conflict, making it a pertinent site for study.

Data Collection

Data were gathered using a purposive sampling approach, involving two groups of respondents living within different distances from the temple area. The first group (n=50) resided within a 1 sq. km radius, while the second group (n=50) was selected from within a 2 sq. km radius, representing residents on the opposite bank of the Punoor river. A structured questionnaire, comprising four parts, was administered through household interviews.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS ver.24 software. The chi-square test of independence was performed to examine relationships between categorical variables. Six socioeconomic variables (Age, Gender, Religion, Occupation, Education, Annual Income) were analyzed concerning the dependent variables (Knowledge of KFD, Presence of monkeys as a problem, Perception of monkeys having religious significance, and feeding of monkeys). A significance level of p < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance, evaluating associations between variables.

The data entry process included strict quality control measures to ensure accuracy. Observed frequencies were compared to expected frequencies, and chi-square statistics along with associated p-values were calculated to identify significant associations between variables as shown in

Table 1. Gender was excluded as a variable for knowledge of KFD due to its non-influential role based on literature and preliminary analysis.

| Independent variables. |

Dependent variables |

| Age |

The presence of monkeys as a problem |

| Gender |

Knowledge of KFD |

| Religion |

Perception of monkeys having religious significance |

| Occupation |

Feeding of monkeys |

| Education |

- |

| Annual Income |

- |

Hypotheses Testing

In addition to descriptive analyses, this study aimed to test specific hypotheses related to human attitudes and practices concerning monkeys were formulated and tested rigorously- Religion has a significant influence on how people perceive the religious significance of monkeys, Education has a substantial role in raising awareness about not feeding monkeys and Religion obligation is the main driver for the practice of feeding monkeys.

Results

The study participants were predominantly Hindus (78%), with smaller percentages of Muslims (6%) and Christians (4%). Gender distribution was balanced, with 53% female and 47% male participants. Educational qualifications varied, ranging from 8th standard to post-graduation, with 12% having no formal education and 4% being students. Regarding income, 36% didn't disclose, 16% earned 0-50 thousand annually, 34% earned 50 thousand-1 lakhs, 8% earned 1-1.5 lakhs, and 6% earned above 1.5 lakhs.

Faith-Based Perspectives: Impact of Occupational Diversity and Religious Affiliation

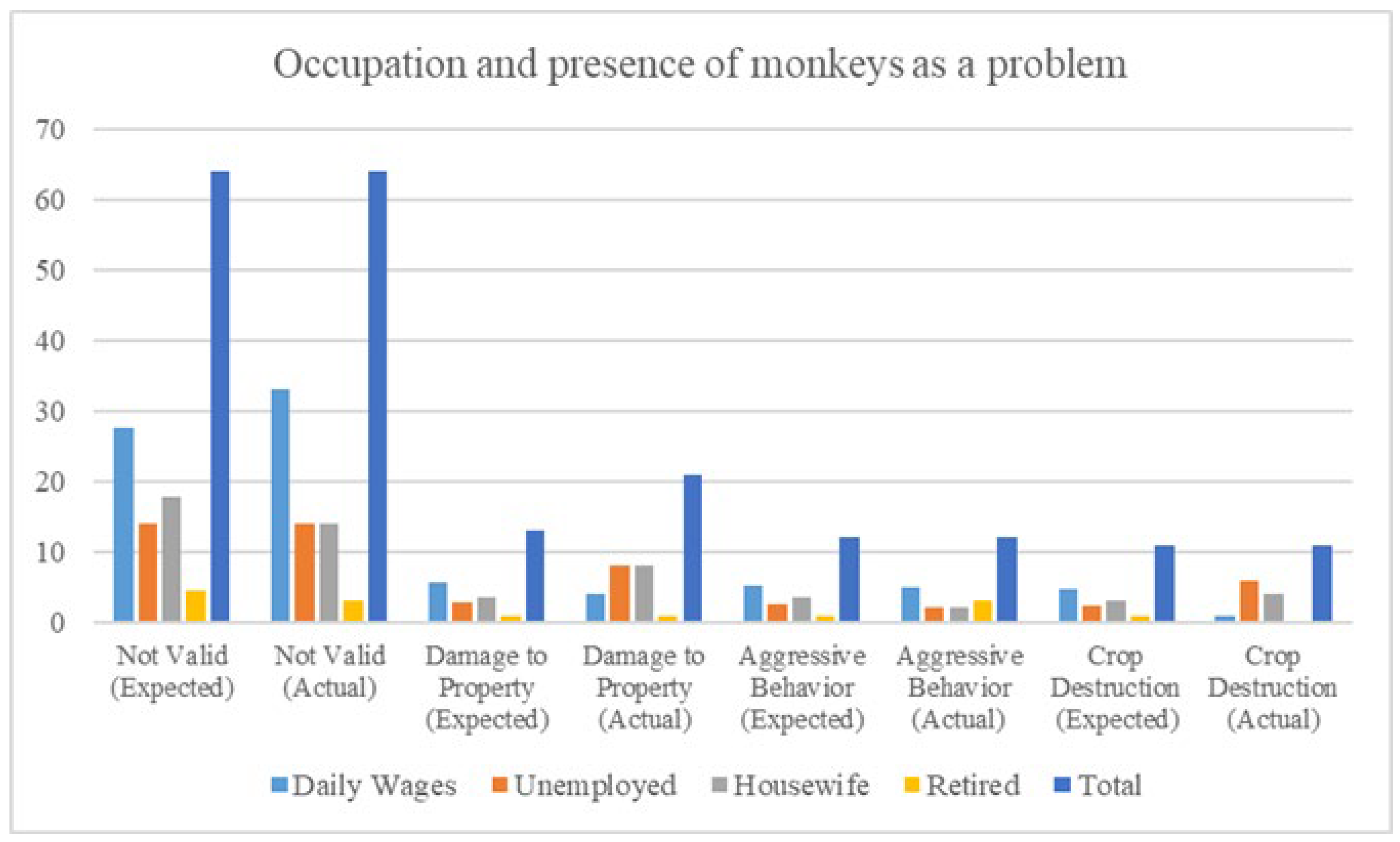

The results of the chi-square test indicated a statistically significant relationship (χ²= 26.529, df=9, p= 0.002), suggesting that occupation significantly influenced how respondents perceived the presence of Bonnet Macaques as a problem in its various dimensions.

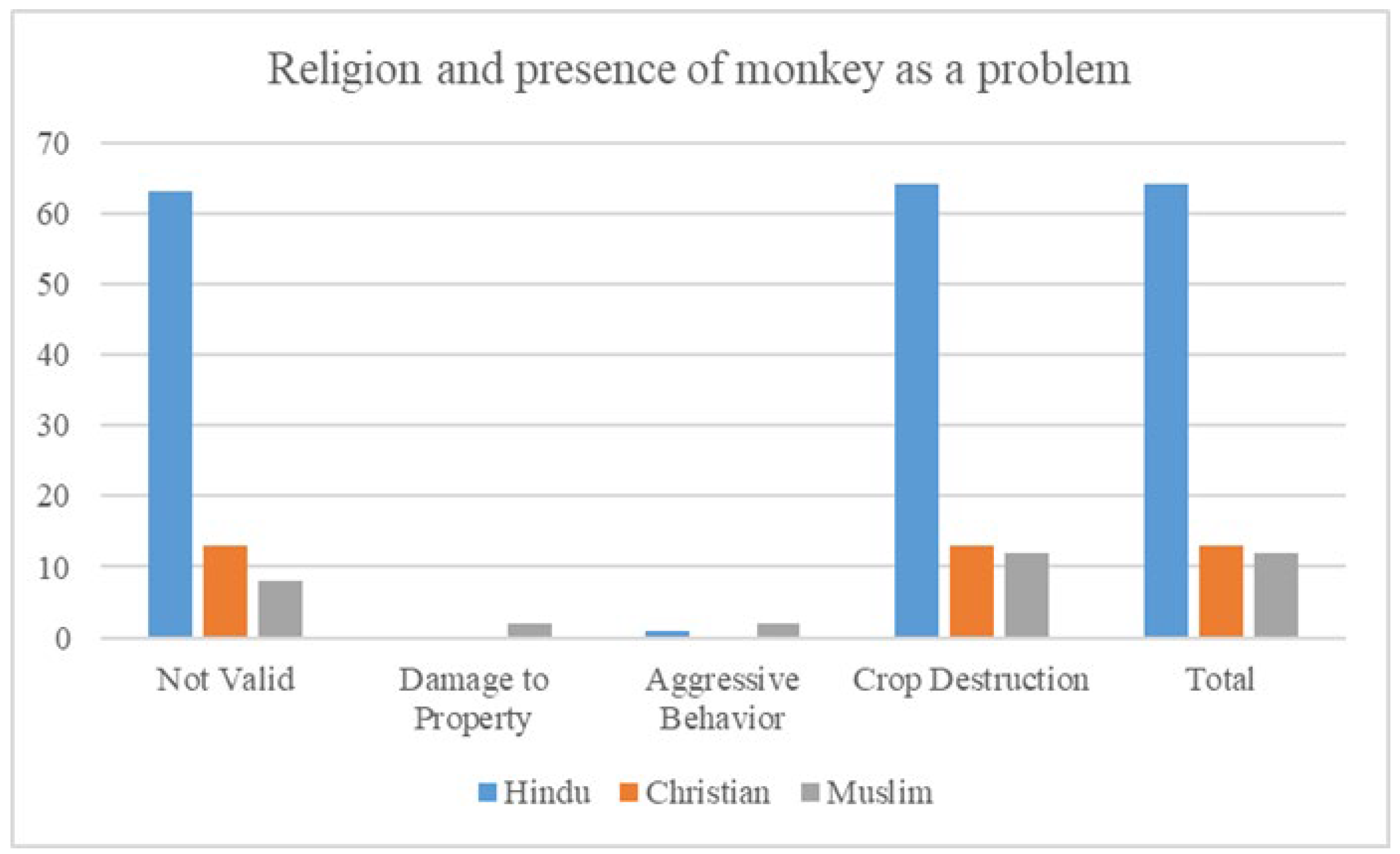

The analysis revealed a statistically significant relationship (χ²= 23.371, df=6, p= 0.001), indicating that religious affiliation significantly influenced how respondents perceived the presence of Bonnet Macaques as a problem.

Educational Impact on Disease Awareness.

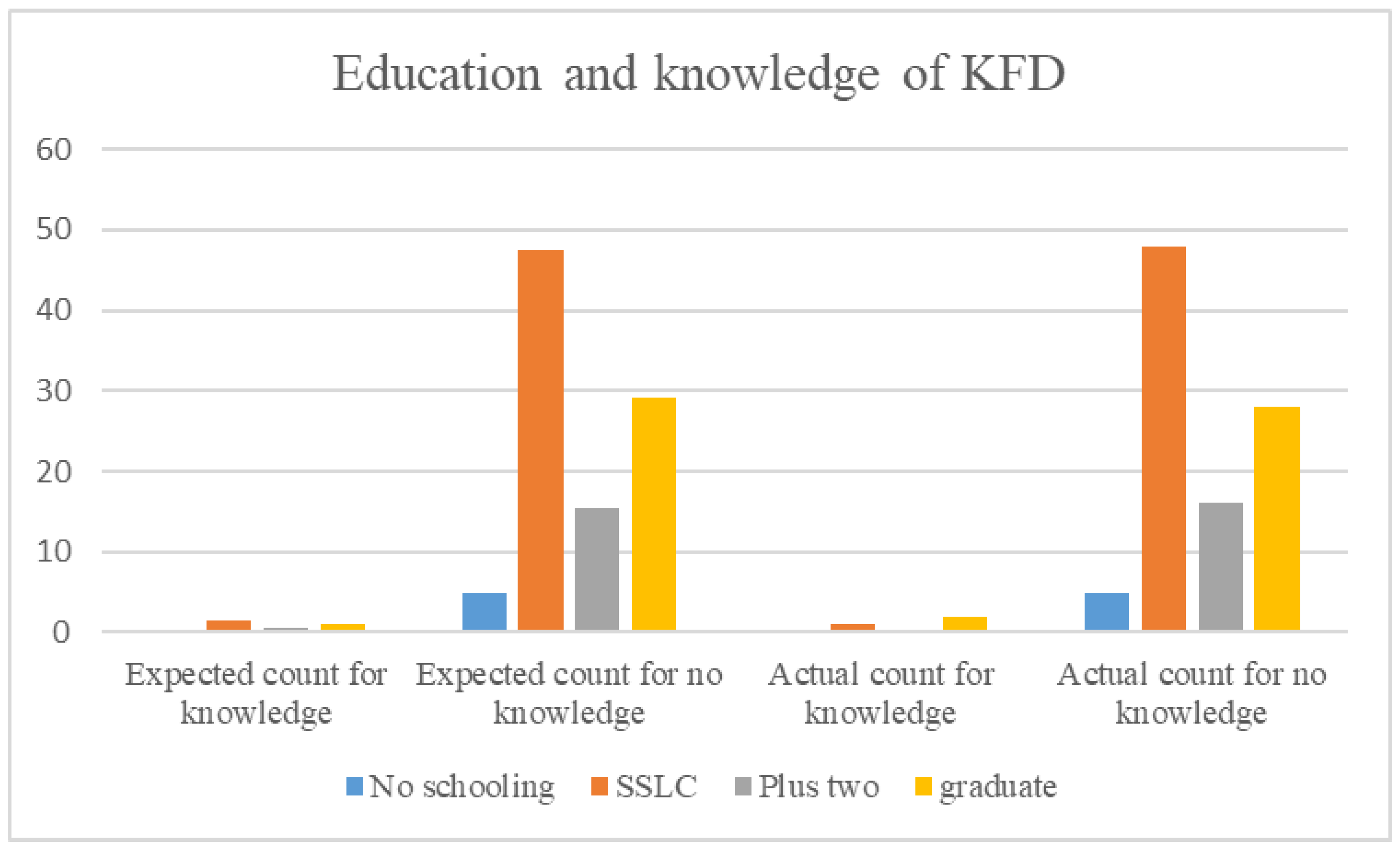

The chi-square test yielded a chi-square value of 2.190 and a p-value of 0.534 with three degrees of freedom, exceeding the conventional significance level of 0.05, indicating that no statistically significant relationship exists between education and knowledge of KFD.

These findings underscore that, regardless of the education level, education did not substantially influence knowledge of KFD among the surveyed individuals.

Age and Religion in the Significance of Monkeys.

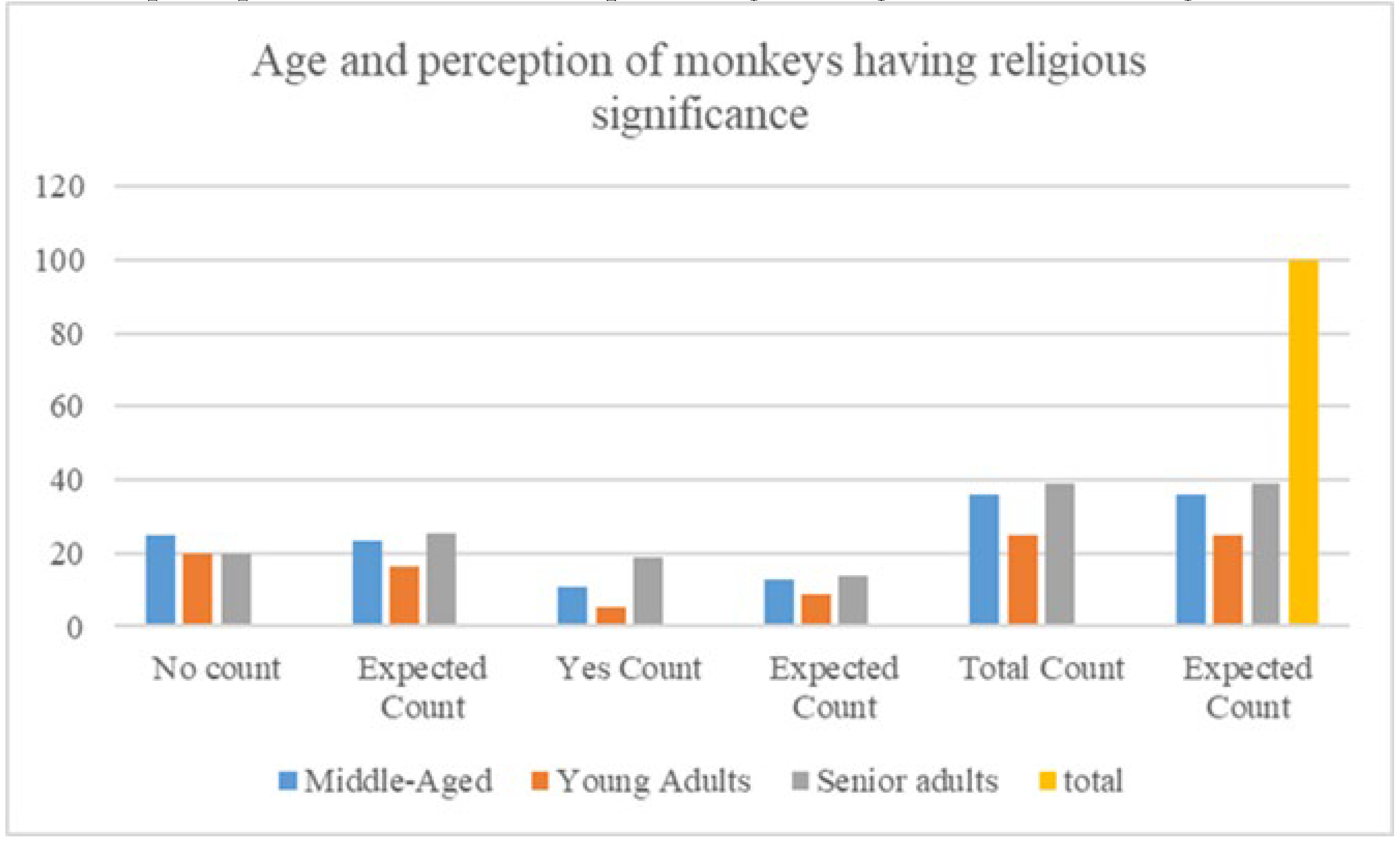

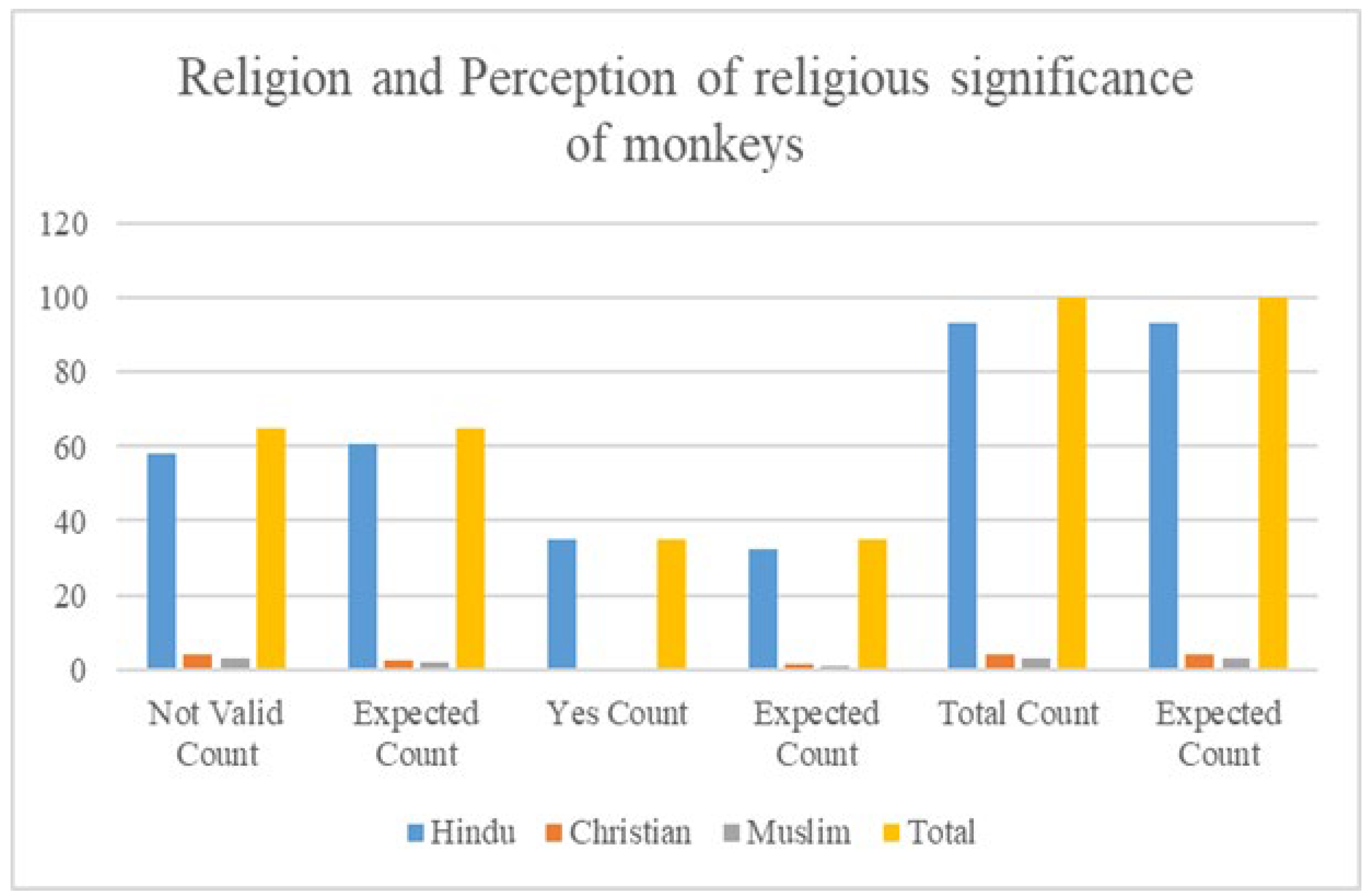

The chi-square test yielded a chi-square value of 6.011 with two degrees of freedom (p= 0.050). These results indicate that there is a statistically significant relationship between age groups and the perception of Bonnet Macaques' religious significance and religion

The study's chi-square test with a value of 4.053 and two degrees of freedom (p= 0.132) indicated no statistically significant association between religion and the perception of monkeys having religious significance. This finding contradicted the hypothesis, emphasizing that respondents' religious affiliation did not significantly influence this perception.

Educational Influence and Religious Belief: Shaping Public Attitudes and Practices.

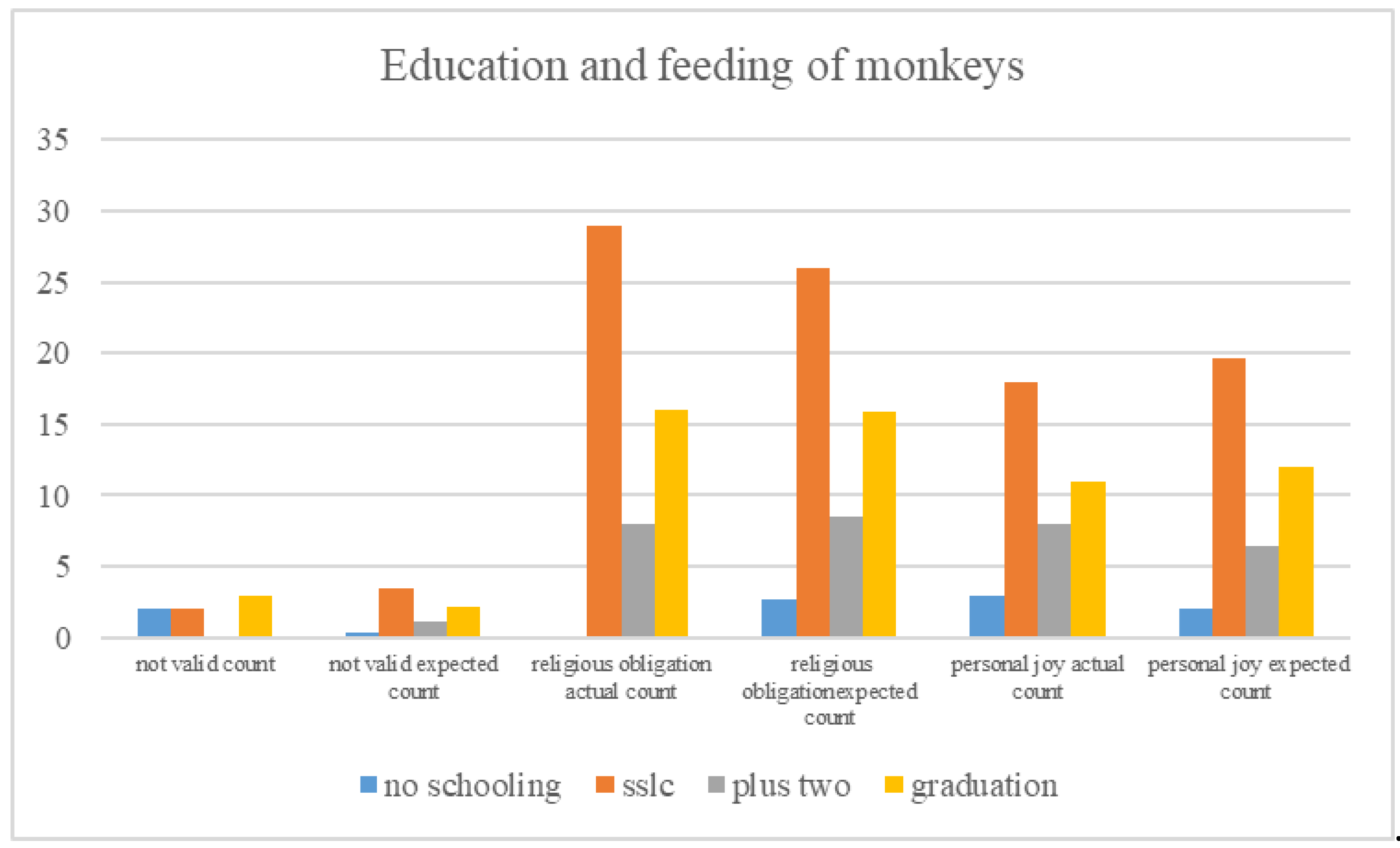

The overall chi-square analysis indicated a statistically significant association between education level and attitude toward Bonnet Macaques and their feeding practices (χ²= 14.026, df= 6, p= 0.029), suggesting that education plays a notable role in shaping individuals' attitudes in this context. Certainly, the hypothesis regarding education's role in raising awareness about wildlife feeding was corroborated by the statistically significant finding which emphasizes the importance of educational initiatives in fostering responsible wildlife interactions and conservation awareness.

Figure 6.

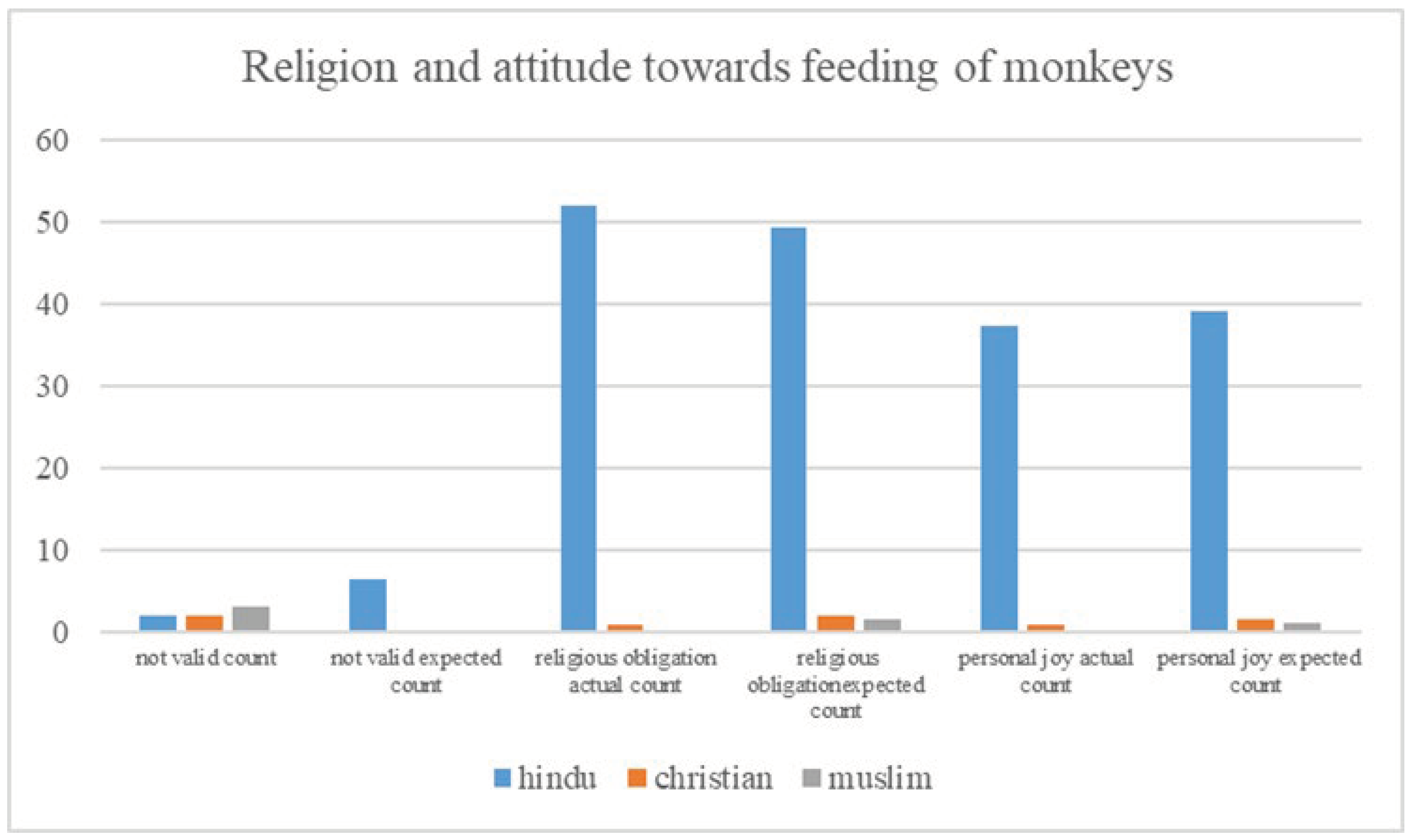

The significant chi-square result (χ²= 54.600, df= 4, p=0.000) highlights the influence of religious beliefs on attitudes toward feeding Bonnet Macaques, supporting the hypothesis about the impact of religious obligations. Additionally, it was evident thatreligious obligations were a significant driver for individuals who fed these primates.

Figure 6.

The significant chi-square result (χ²= 54.600, df= 4, p=0.000) highlights the influence of religious beliefs on attitudes toward feeding Bonnet Macaques, supporting the hypothesis about the impact of religious obligations. Additionally, it was evident thatreligious obligations were a significant driver for individuals who fed these primates.

Discussion

Cultural values serve as the cornerstone for a multitude of norms that intricately guide individuals in their behaviours across diverse social landscapes. They also play a pivotal role in shaping human attitudes towards the natural world and environment (Knight, 2000). These attitudes, in turn, exert a profound influence on the complex phenomenon of HWC and its management strategies. It is important to recognize that cultural disparities between societies or social groups can give rise to distinct manifestations of HWC in various regions. Therefore, a cross-cultural examination of HWC assumes paramount importance, as it can provide essential insights for the effective mitigation of HWC (Manfredo and Dayer, 2004).

Key Factors Shaping Attitudes on Monkey Presence: Occupation and Religion

Occupation appears to significantly influence how respondents perceive the presence of monkeys as a problem in dimensions such as damage to property, aggressive behaviour and crop destruction. This suggests that the daily roles and responsibilities associated with different occupations can shape perspectives of individuals on the impact of monkeys. Similarly, religious affiliation also exhibited a statistically significance, this outcome suggests that cultural and religious beliefs or practices may influence how individuals interpret and respond to the presence of these animals. These findings resonate with the study conducted to examine the role of religion and human attitude towards primates, 86 percent of respondents interviewed responded that monkeys were not killed or harmed because of its association with shrine and cultural beliefs (Baker et al., 2014).

Age, gender, education and annual income was not statistically significant. This finding has several implications. Firstly, it suggests that the challenges posed by monkeys are perceived consistently across different groups, transcending generational gaps. Secondly, it highlights the potential influence of other factors, beyond demographics, in shaping how individuals perceive human-macaque conflicts. These factors could encompass cultural beliefs, environmental conditions or community experiences, which may be more significant drivers of perception. In the context of this study, findings from a parallel wolf conservation research (Lute et al., 2016) reveal subtle influences of demographics on intrinsic value and conservation support. Age, gender, education, and income showed minor effects, underscoring the complex nature of human-wildlife interactions.

Reassessing the Relationship Between Education and Disease Awareness: Lessons from KFD and RID Studies

Contrary to the hypothesis, education level did not significantly impact respondents' knowledge of KFD. This observation raises the possibility that KFD awareness is not strongly correlated with formal education. This could be because basic awareness of zoonotic diseases like KFD may not be guaranteed solely through formal education, as information about such diseases can also be disseminated through various informal channels. This conclusion aligns with a study in Gansu, China, which aimed to assess the impact of health education on students' knowledge and behavior concerning respiratory infectious disease (RID).

Prior to the implementation of the health education program, notable disparities in accuracy rates existed between the intervention and control groups for certain knowledge and behavior items. However, following the program, the intervention group exhibited significantly improved accuracy rates in both knowledge and behaviors, underscoring the effectiveness of the health education initiative. Notably, the accuracy rates in the intervention group surged from 5.59 per cent to an impressive 81.01 per cent (Wang and Fang, 2020).

Sacred Bonds: Understanding the Religious Significance of Bonnet Macaques

In this study, age emerged as a pivotal factor influencing perceptions of the religious significance of monkeys, suggesting diverse beliefs across age groups. Surprisingly, religious affiliation did not significantly impact these perceptions, challenging conventional assumptions. Regardless of religious backgrounds, a shared belief system prevailed, indicating a strong cultural inclusivity fostering collective views. Our findings align with the study conducted on examined peoples’ attitudes in Buddhist and Muslim communities, suggests that influence of religion on attitudes toward carnivores is complex and relatively weak. Less than 10 per cent of the interviewees provided moral or religious arguments to protect the carnivores, and the overall effect of religion on attitudes was statistically non-significant. However, religiosity was positively correlated with pro-carnivore attitudes among Buddhist communities but not among Muslim communities, emphasizing the role of cultural context in shaping these attitudes (Bhatia et al., 2017).

Faith and Awareness: Influences on Feeding of Monkeys

Education, displayed statistical significance, mostly because it may have raised awareness about responsible wildlife interactions and conservation, leading to more informed decisions regarding the feeding of wildlife. Religion exhibited a strong statistical significance, highlighting its influence on the practice of feeding monkeys. Religious obligations appeared to be a significant driver, indicating that cultural and religious beliefs strongly influence human-wildlife interactions. In cultures where religious obligations are associated with feeding monkeys, people may be more inclined to engage in this practice due to the belief that it carries spiritual significance or fulfils religious duties. Our findings align with similar studies conducted in different locations, such as the monkeys inhabiting the tourist spot and those living in the hilly temple. These studies also observed that monkeys in temple areas tend to consume more human food, likely due to the provisioned food they receive in those areas, compared to monkeys in other tourist attractions. This consistency in findings across different locations suggests that the presence of temples and the practice of providing food to monkeys is related to religious practice, and may contribute to higher levels of human food consumption among these primates (Wolfe, 1992).

Conclusion

The study underscores the complex interplay of cultural, religious, and educational factors in shaping human attitudes and behaviors regarding human-wildlife interactions, specifically concerning monkeys. The study highlights the significant impact of cultural values and religious beliefs on human-wildlife interactions, particularly regarding the presence of monkeys. Occupation and religious affiliation emerged as crucial determinants, indicating the diverse ways individuals perceive and respond to monkeys' presence. The research revealed cultural inclusivity and shared belief systems, emphasizing the intricate and varied influences of religion on attitudes toward wildlife.

Contrary to expectations, formal education alone did not guarantee awareness of zoonotic diseases like KFD. The study suggested that awareness of such diseases may not be strongly correlated with formal education, as information is disseminated through diverse informal channels. Awareness programs and health education initiatives tailored to specific cultural contexts were effective in enhancing knowledge and behavior related to wildlife and disease management. The study sheds light on the complex dynamics surrounding the religious significance of Bonnet Macaques. Age was identified as a key factor, influencing how individuals perceive the religious importance of monkeys. This finding implies a diverse range of beliefs across different age groups, underlining the nuanced nature of cultural attitudes towards these animals. Moreover, the study challenged conventional assumptions by revealing that religious affiliation did not significantly affect these perceptions. Regardless of their religious backgrounds, participants shared a common belief system, highlighting a strong sense of cultural inclusivity that fostered collective views on the religious significance of Bonnet Macaques.

These results underscore the intricate interplay of age, cultural beliefs, and religious affiliations in shaping human attitudes towards wildlife, particularly in the context of the Bonnet Macaques. The findings emphasize the need for a nuanced understanding of cultural and generational perspectives when addressing matters related to religious beliefs and wildlife interactions. This insight is invaluable for developing targeted and culturally sensitive conservation strategies, promoting harmony between religious practices and wildlife conservation efforts. The study underscored the strong influence of religion on the feeding of monkeys. Religious obligations significantly impacted this practice, revealing the deep-rooted connection between spiritual beliefs and human-wildlife interactions. Areas with temples and religious significance exhibited distinct patterns of wildlife feeding, emphasizing the role of religious practices in shaping these behaviors. Contrarily, individuals with higher levels of education exhibited awareness and made informed decisions, highlighting the importance of education in curbing the practice of wildlife feeding.

Moving forward, further research should aim to incorporate molecular techniques for parasite detection can enhance the understanding of specific parasite species and their zoonotic risks (Jones-Engel et al., 2006). Furthermore, it is imperative to recognize that these interactions between humans and monkeys transcend mere biological encounters; they are intricately interwoven with cultural and social values. Furthermore, it is imperative to recognize that these interactions between humans and monkeys transcend mere biological encounters; they are intricately interwoven with cultural and social values. In light of this, the development and implementation of effective mitigation strategies must extend beyond ecological considerations and encompass a deep understanding of the beliefs and values held by the local population. Therefore, acknowledging and respecting these cultural and social perspectives is paramount, as it not only enriches the ecological discourse but also ensures the success and sustainability of conservation initiatives. It is essential to integrate ecology, parasitology and public health seamlessly to address these complex interactions.

Acknowledgments

Centre for Wildlife Studies, Kerala Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Wayanad, Kerala

References

- Anand, S., & Radhakrishna, S. (2017) Investigating trends in human-wildlife conflict: Is conflict escalation real or imagined? Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity, 10:154–161.

- Baker, L. R., Olubode, O. S., Tanimola, A. A., & Garshelis, D. L. (2014) Role of local culture, religion, and human attitudes in the conservation of sacred populations of a threatened ‘pest’ species. Biodiversity and Conservation, 23:1895–1909.

- Bhatia, S., Redpath, S. M., Suryawanshi, K., & Mishra, C. (2017) The Relationship Between Religion and Attitudes Toward Large Carnivores in Northern India? Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 22: 30–42.

- Bhatia, S., Redpath, S. M., Suryawanshi, K., & Mishra, C. (2020) Beyond conflict: Exploring the spectrum of human–wildlife interactions and their underlying mechanisms. Oryx, 54: 621–628. [CrossRef]

- Dickman, A. J. (2010) Complexities of conflict: The importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human–wildlife conflict. Animal Conservation, 13: 458–466. [CrossRef]

- Jones-Engel, L., Engel, G. A., Heidrich, J., Chalise, M., Poudel, N., Viscidi, R., Barry, P. A., Allan, J. S., Grant, R., & Kyes, R. (2006) Temple Monkeys and Health Implications of Commensalism, Kathmandu, Nepal. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12: 900–906.

- Knight, J. (2000). Natural Enemies: People-wildlife Conflicts in Anthropological Perspective. Psychology Press.

- Kumara, H. N., Kumar, S., & Singh, M. (2010) Of how much concern are the ‘least concern’ species? Distribution and conservation status of bonnet macaques, rhesus macaques and hanuman langurs in Karnataka, India. Primates, 51: 37–42.

- Lute, M. L., Navarrete, C. D., Nelson, M. P., & Gore, M. L. (2016) Moral dimensions of human-wildlife conflict: Human-Wildlife Conflict. Conservation Biology, 30: 1200–1211.

- Manfredo, M. J., & Dayer, A. A. (2004) Concepts for Exploring the Social Aspects of Human–Wildlife Conflict in a Global Context. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 9: 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Nyhus, P. J. (2016) Human–Wildlife Conflict and Coexistence. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 41:143–171.

- Prokop, P., Fančovičová, J., & Kubiatko, M. (2009) Vampires Are Still Alive: Slovakian Students’ Attitudes toward Bats. Anthrozoös, 22: 19–30. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishna, S. (2013) Songs of Monkeys: Representation of Macaques in Classical Tamil Poetry. In S. Radhakrishna, M. A. Huffman, & A. Sinha (Eds.), The Macaque Connection: Cooperation and Conflict between Humans and Macaques (pp. 53–68). Springer.

- Singh, M., Erinjery, J. J., Kavana, T. S., Roy, K., & Singh, M. (2011) Drastic population decline and conservation prospects of roadside dark-bellied bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata radiata) of southern India. Primates, 52:149–154. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M., & Rao, N. R. (2004) Population Dynamics and Conservation of Commensal Bonnet Macaques. International Journal of Primatology, 25: 847–859. [CrossRef]

- Soulsbury, C. D., & White, P. C. L. (2015) Human–wildlife interactions in urban areas: A review of conflicts, benefits and opportunities. Wildlife Research, 42: 541–553.

- Southwick, C. H., & Siddiqi, M. F. (1994) Population status of nonhuman primates in Asia, with emphasis on rhesus macaques in India. American Journal of Primatology, 34: 51–59.

- Sugiyama, Y. (1971) Characteristics of the social life of bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata). Primates, 12:247–266. [CrossRef]

- Treves, A., & Karanth, K. U. (2003) Human-Carnivore Conflict and Perspectives on Carnivore Management Worldwide. Conservation Biology, 17: 1491–1499. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., & Fang, H. (2020) The effect of health education on knowledge and behavior toward respiratory infectious diseases among students in Gansu, China: A quasi-natural experiment. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 681.

- Wolfe, L. D. (1992) Feeding habits of the rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) of Jaipur and Galta, India. Human Evolution, 7: 43–54. [CrossRef]

- Woodroffe, R., Thirgood, S., & Rabinowitz, A. (2005) People and Wildlife, Conflict or Co-existence? Cambridge University Press.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).